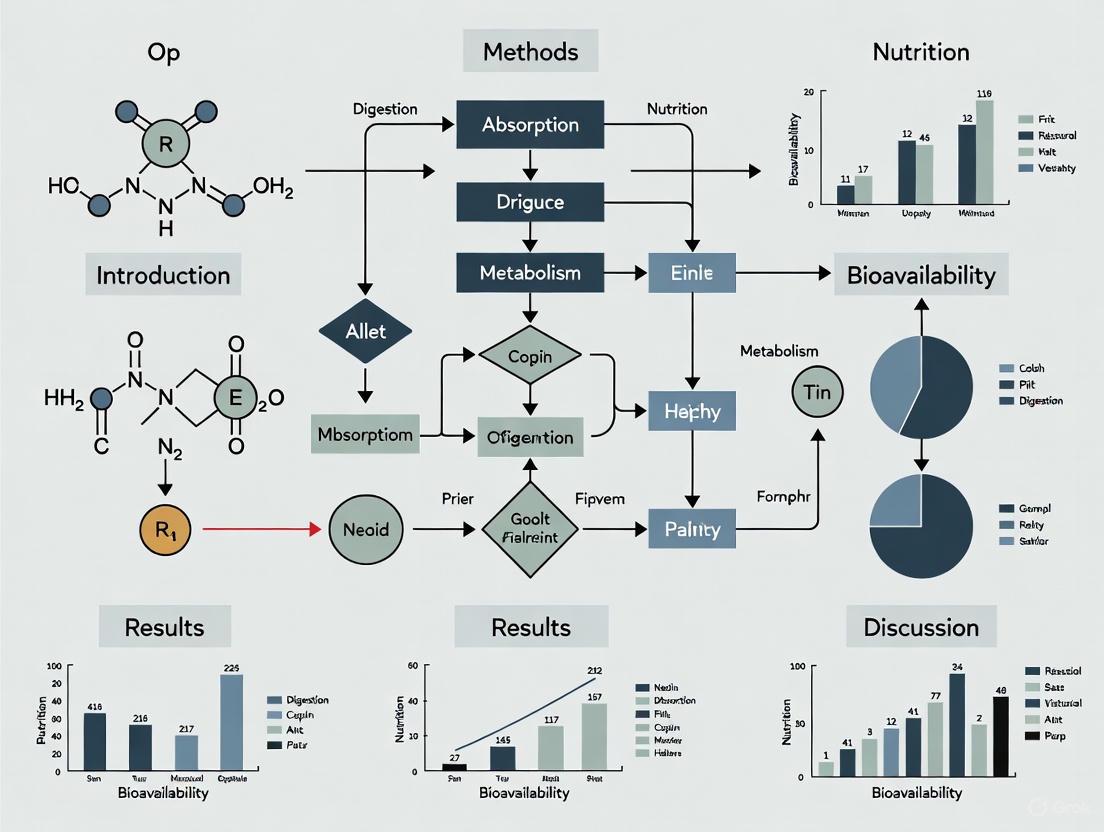

Advanced Strategies for Enhancing the Bioavailability of Functional Food Components: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the scientific and technological advancements aimed at optimizing the bioavailability of functional food components.

Advanced Strategies for Enhancing the Bioavailability of Functional Food Components: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the scientific and technological advancements aimed at optimizing the bioavailability of functional food components. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental barriers limiting the efficacy of bioactive compounds—such as poor solubility, metabolic instability, and inefficient absorption. The scope encompasses a critical evaluation of innovative delivery systems, including nanoencapsulation, lipid-based carriers, and biotransformation approaches. Furthermore, it addresses troubleshooting for common formulation challenges, comparative analysis of validation methodologies, and the emerging role of AI and precision nutrition in designing next-generation functional foods with enhanced therapeutic potential for combating chronic diseases.

Understanding Bioavailability Barriers: The Science Behind Bioactive Compound Absorption

Core Concepts of Bioavailability and ADME

Bioavailability is a critical pharmacokinetic (PK) parameter defined as the fraction of an administered drug or active compound that reaches the systemic circulation unaltered [1] [2]. It is quantitatively expressed as a percentage, ranging from 0% (no active compound reaches circulation) to 100% [2]. For an intravenous (IV) dose, bioavailability is by definition 100% because the drug is injected directly into the bloodstream [1] [2].

The journey of a compound within the body is described by the ADME framework, which encompasses Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion [3] [4]. Bioavailability is an integral part of this paradigm, representing the combined result of absorption and first-pass metabolism [3] [1]. The extent and rate of these processes determine the concentration of the active compound at its target site, thereby influencing its therapeutic efficacy [3].

- Absolute vs. Relative Bioavailability: Absolute bioavailability compares the systemic availability of a drug from a non-IV formulation to that of an IV dose. Relative bioavailability compares the bioavailability of two different non-IV formulations (e.g., an oral solution versus a tablet) [2].

- First-Pass Effect: For orally administered compounds, a significant barrier to bioavailability is the first-pass effect. After ingestion, the compound must survive the gastrointestinal (GI) environment, cross the gut wall, and then travel via the portal vein to the liver, where it may be extensively metabolized before ever reaching the systemic circulation [3] [2]. This sequential reduction in the active compound's amount is a key reason why oral bioavailability is often less than 100% [2].

Table 1: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters and Their Definitions

| Parameter | Definition | Formula/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bioavailability (F) | The fraction of an administered dose that reaches systemic circulation [1] [2]. | ( F = \frac{AUC{PO}}{AUC{IV}} \times \frac{Dose{IV}}{Dose{PO}} ) (For absolute bioavailability) [1] |

| Volume of Distribution (Vd) | The apparent theoretical volume required to distribute the total amount of drug in the body to achieve the measured plasma concentration [3]. | ( Vd = \frac{Total\ Amount\ of\ Drug\ in\ Body}{Plasma\ Drug\ Concentration} ) [3] [1] |

| Clearance (CL) | The volume of plasma from which a drug is completely removed per unit of time [3]. | ( CL = \frac{Elimination\ Rate}{Plasma\ Drug\ Concentration} ) [3] [1] |

| Half-Life (t½) | The time required for the plasma drug concentration to reduce by 50% [3]. | ( t_{1/2} = \frac{0.693 \times Vd}{CL} ) [3] |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | A measure of the total drug exposure over time in the plasma, used to calculate bioavailability [3] [1]. | Integral of the plasma concentration-time curve [3] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Bioavailability Challenges and Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific, measurable problems when evaluating bioavailability. This section addresses these issues with targeted troubleshooting advice.

FAQ 1: How do I troubleshoot low oral bioavailability in a new chemical entity?

Low oral bioavailability can stem from poor absorption, high first-pass metabolism, or both. A systematic approach is required to isolate the root cause [5].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Oral Bioavailability

| Observed Issue | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Solubility & Dissolution Rate | The compound does not dissolve adequately in the GI fluids, limiting absorption [6]. | Diagnose: Determine solubility across physiological pH range (1.2-7.5). Perform dissolution testing [6].Solve: Implement salt formation, cocrystallization, particle size reduction (nanonization), or amorphous solid dispersions [6]. |

| Poor Permeability | The compound cannot efficiently cross the intestinal epithelial membrane [6]. | Diagnose: Use in vitro models like Caco-2 cell monolayers or PAMPA to assess permeability [6].Solve: Explore structural modifications to optimize lipophilicity (LogP/D), or formulate with permeability enhancers [6]. |

| High First-Pass Metabolism | The compound is extensively metabolized in the gut wall or liver before reaching systemic circulation [3] [2]. | Diagnose: Compare AUC after oral vs. intra-arterial administration. Use liver microsomes or hepatocytes to assess metabolic stability [4].Solve: Consider a prodrug strategy or alternative route of administration (e.g., sublingual) to bypass first-pass effects [6]. |

| Efflux by Transporters | The compound is a substrate for efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which pumps it back into the gut lumen [1]. | Diagnose: Conduct transport assays in cell lines overexpressing specific efflux transporters (e.g., MDCK-MDR1) [1].Solve: Investigate structural analogs that are not P-gp substrates, or use pharmaceutical excipients that inhibit P-gp [1]. |

FAQ 2: Our in vitro data does not correlate with in vivo bioavailability results. What could be wrong?

This common problem often arises from oversimplified in vitro models that fail to capture the complexity of the in vivo environment.

- Solution: Adopt more physiologically relevant models and ensure experimental rigor.

- Change one variable at a time: When troubleshooting, only change one experimental parameter at a time to clearly identify its effect [5].

- Use higher-fidelity systems: Move from simple microsomal stability assays to plated hepatocytes or hepatocytes in suspension, which contain a fuller complement of Phase I and Phase II enzymes and can provide a better prediction of in vivo metabolism [4].

- Account for protein binding: In vitro systems often lack plasma proteins. The free, unbound drug concentration, not the total, more closely correlates with pharmacological effect and metabolism. Measure plasma protein binding and consider its impact [3].

- Plan experiments carefully: A failed experiment due to poor planning may not be repeated, causing the loss of a potentially good idea. Meticulous experimental design is crucial for generating reliable and reproducible data [5].

FAQ 3: How can we improve the predictive power of our early ADME studies?

Modern tools and strategies can significantly enhance the translation from early discovery to clinical outcomes.

- Solution: Integrate advanced in silico and analytical technologies.

- Leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI): Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models can predict complex structure-bioavailability relationships, forecast dissolution dynamics, and identify bioactive peptides, reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming in vivo trials in the early stages [7].

- Utilize Cassette Dosing: For compounds within a specific chemical template, "cassette" or "n-in-1" dosing (administering several compounds together to a single animal) can be a powerful high-throughput screening tool. This approach relies on highly selective analytical methods like LC-MS/MS for quantitative analysis [4].

- Apply Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI): Techniques like MALDI or DESI MSI allow for the direct visualization of drug and metabolite distribution within tissue slices, providing unparalleled insight into a compound's in vivo distribution profile [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Bioavailability Studies

This section provides detailed methodologies for foundational experiments in bioavailability research.

Protocol: Determining Absolute Oral Bioavailability in a Rodent Model

Objective: To calculate the absolute bioavailability (F) of a test compound by comparing its systemic exposure after oral (PO) and intravenous (IV) administration.

Materials:

- Test compound (for PO and IV formulation)

- Vehicle/solvent for formulation (e.g., saline, PEG, DMSO)

- Laboratory rodents (e.g., rats or mice)

- IV catheterization supplies

- Oral gavage needles

- Microcentrifuge tubes (containing anticoagulant, e.g., Kâ‚‚EDTA)

- LC-MS/MS system with validated bioanalytical method

Methodology:

- Formulation: Prepare two formulations.

- IV Formulation: Ensure the compound is in a sterile, soluble form suitable for bolus injection (e.g., in saline).

- PO Formulation: Prepare a solution or suspension for oral gavage. The dose may be higher than the IV dose to account for expected lower bioavailability.

- Dosing and Sampling:

- Divide animals into two groups (IV and PO). A crossover design can be used but requires a sufficient washout period.

- Administer the IV dose via a tail or jugular vein catheter. Administer the PO dose via oral gavage.

- Collect serial blood samples (e.g., at 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours post-dose) from each animal. The specific timepoints should be pilot-tested.

- Centrifuge blood samples immediately to obtain plasma and store at -80°C until analysis.

- Bioanalysis:

- Use a selective and sensitive LC-MS/MS method to determine the plasma concentration of the test compound in all samples.

- Generate standard curves and quality control (QC) samples in the same biological matrix to ensure accuracy and precision.

- Data Analysis:

- For each animal and each route, plot the plasma concentration versus time curve.

- Use a PK software package to calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) from zero to the last time point (AUC₀–t) and extrapolated to infinity (AUC₀–∞) for both routes.

- Calculate absolute bioavailability using the formula: ( F = \frac{AUC{PO} \times Dose{IV}}{AUC{IV} \times Dose{PO}} \times 100\% ) where ( AUC{PO} ) and ( AUC{IV} ) are the dose-normalized AUC values [1] [2].

Protocol: Assessing Metabolic Stability Using Liver Microsomes

Objective: To determine the in vitro half-life (t½) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) of a test compound using liver microsomes, predicting its metabolic stability.

Materials:

- Test compound

- Liver microsomes (from human or relevant animal species)

- NADPH-regenerating system (e.g., NADP+, glucose-6-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase)

- 100 mM Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4

- Methanol or Acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

- Heating block or water bath at 37°C

- LC-MS/MS system

Methodology:

- Incubation Preparation:

- Prepare an incubation mixture in microcentrifuge tubes containing:

- 0.1 mg/mL microsomal protein

- 1 µM test compound

- 100 mM Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4

- Pre-incubate the mixture for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Prepare an incubation mixture in microcentrifuge tubes containing:

- Initiation and Quenching:

- Start the reaction by adding the NADPH-regenerating system.

- At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 minutes), remove an aliquot of the incubation mixture and quench it with a cold volume of methanol or acetonitrile (containing an internal standard) that is at least twice the volume of the aliquot.

- Vortex and centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 14,000 rpm) for 10 minutes to precipitate proteins.

- Bioanalysis:

- Inject the supernatant into the LC-MS/MS system to quantify the remaining parent compound at each time point.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the natural logarithm (ln) of the parent compound's remaining percentage against time.

- The slope of the linear regression of this plot is the elimination rate constant (k).

- Calculate the in vitro half-life: ( t_{1/2} = \frac{0.693}{k} )

- Calculate the intrinsic clearance: ( CL{int} = \frac{0.693}{t{1/2}} \times \frac{Incubation\ Volume}{Microsomal\ Protein} ) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Bioavailability Research |

|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, forms a monolayer with tight junctions and expresses transporters, mimicking the intestinal barrier. Used for in vitro permeability assessment [6]. |

| Liver Microsomes | Subcellular fractions containing membrane-bound cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes. Used for high-throughput screening of metabolic stability and reaction phenotyping [4]. |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Intact liver cells containing a full suite of metabolizing enzymes (Phase I and Phase II). Provide a more physiologically relevant model for metabolism and toxicity studies than microsomes [4]. |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Supplies a constant source of NADPH, a crucial cofactor for CYP450-mediated oxidative metabolism. Essential for activity in microsomal and hepatocyte incubations [4]. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol) with minimal alkali metal ion contamination. Critical for preventing adduct formation and maintaining sensitivity in LC-MS analysis, especially for oligonucleotides and polar molecules [5]. |

| Artificial Gastrointestinal Fluids | Simulated gastric and intestinal fluids (e.g., FaSSGF, FaSSIF) with defined pH, buffer capacity, and bile salt/phospholipid content. Used in dissolution testing to predict in vivo dissolution behavior [6]. |

| Glycidyl Palmitate-d5 | Glycidyl Palmitate-d5 Stable Isotope|CAS 1794941-80-2 |

| Mesalazine-D3 | Mesalazine-D3 Stable Isotope |

For researchers in functional food development, the therapeutic promise of a bioactive compound is often limited by its bioavailability—the proportion that reaches systemic circulation to exert its desired physiological effect [8]. This journey is governed by three major, interconnected factors: solubility, stability, and mucosal permeability [9] [6].

A compound must first dissolve in the gastrointestinal fluids (solubility), survive the harsh biochemical environment of the gut and during processing (stability), and then efficiently cross the mucosal barrier to be absorbed (permeability) [9]. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) provides a framework for predicting a compound's absorption based on these properties, with BCS Class II (low solubility, high permeability) and Class IV (low solubility, low permeability) posing the most significant development challenges [9] [10]. Overcoming these hurdles is paramount for enhancing the efficacy of functional food components, from lipophilic vitamins and omega-3 fatty acids to various polyphenols and carotenoids [8] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Solubility

Q: My bioactive compound shows poor aqueous solubility. What are my primary strategies to enhance it for a functional food formulation?

Poor aqueous solubility is a major hurdle, as a compound must be dissolved to be absorbed [10]. The following strategies are commonly employed, each with distinct advantages.

Table: Strategies for Enhancing Bioactive Compound Solubility

| Strategy | Brief Principle | Common Techniques/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Modification [9] [10] | Alters the physical state of the drug to increase surface area or energy. | Micronization, Nanosuspensions, Solid Dispersions (in carriers like polymers), Cryogenic Techniques, Supercritical Fluid Technology |

| Chemical Modification [9] [10] | Modifies the chemical form of the drug to improve dissolution. | Salt Formation, Prodrug Formation |

| Formulation-Based Approaches [9] [11] | Uses excipients or carrier systems to solubilize the compound. | Cosolvency (e.g., using ethanol, PEG), Hydrotropy, Surfactants, Lipid-Based Delivery Systems (e.g., SNEDDS, NLCs, Nanoemulsions) |

Q: How can I rapidly and accurately determine the kinetic solubility of new candidate compounds during early-stage screening?

A: Nephelometry is a high-throughput, non-destructive technique ideal for kinetic solubility screening [12] [13]. It measures the light scattered by insoluble particles in a solution, allowing you to identify the concentration at which a compound begins to precipitate.

Experimental Protocol: Kinetic Solubility Assay via Nephelometry

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of your compound in DMSO. Perform serial dilutions in your target aqueous buffer (e.g., PBS) across a 96- or 384-well microplate, ensuring a final DMSO concentration that does not artificially enhance solubility (typically ≤1-5%) [12] [13].

- Incubation: Allow the plate to incubate for a standardized period (e.g., 15-60 minutes) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) to reach equilibrium.

- Nephelometry Measurement: Use a microplate nephelometer (e.g., NEPHELOstar Plus). The instrument directs a laser beam (e.g., 635 nm) through each well and a detector measures the intensity of light scattered at a 90-degree angle [12]. A higher signal indicates more insoluble particles.

- Data Analysis: Plot the nephelometric signal (scattered light intensity) against the compound concentration. The kinetic solubility is identified as the point where the scatter signal increases dramatically, indicating the onset of precipitation. This is often determined by the intersection of two linear regression lines fitted to the soluble and precipitate-dominated data points [13].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for determining kinetic solubility using nephelometry.

Stability

Q: The lipophilic bioactive (e.g., carotenoid, omega-3) in my functional food product degrades during processing (heat, pH) and storage. How can I protect it?

A: Encapsulation within delivery systems is the primary strategy to shield sensitive compounds from environmental stresses like heat, oxygen, light, and pH fluctuations [11]. These systems create a physical barrier around the bioactive.

Table: Delivery Systems for Enhancing Bioactive Stability

| Delivery System Type | Key Components | Protective Mechanism & Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid-Based Nanocarriers [9] [11] | Lipids, Surfactants, Water | Encapsulates bioactives in oil droplets or lipid matrices, protecting from the aqueous environment and enabling high retention during processing. |

| Polymer-Based Nanocarriers [9] [11] | Proteins (e.g., whey, zein), Polysaccharides (e.g., alginate, chitosan) | Forms a dense polymer matrix or wall around the bioactive. Can be engineered for controlled release and offers protection against ionic strength and pH changes. |

Q: How do I experimentally evaluate the stability of an emulsion-based delivery system for my bioactive compound?

A: Stability is a multi-faceted parameter. You should assess it using a combination of the following techniques, which monitor different instability mechanisms like creaming, flocculation, and coalescence [14].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Emulsion System Stability

- Visual Observation & Creaming Index: Fill a sealed, transparent vial or cylinder with a known volume of the emulsion. Store it under controlled conditions (e.g., 25°C or 40°C) and observe for phase separation over time. The Creaming Index can be calculated as:

(Height of Cream or Sediment Layer / Total Height of Emulsion) × 100%[14]. - Particle Size Analysis: Use dynamic light scattering (DLS) to measure the droplet size and particle size distribution (PSD) of the emulsion initially and at regular time points. An increase in mean droplet size or the appearance of a larger population indicates droplet aggregation (flocculation) or fusion (coalescence) [14].

- Zeta Potential Measurement: Using electrophoretic light scattering, determine the zeta potential—a key indicator of the electrostatic repulsion between droplets. A high absolute zeta potential (typically > ±30 mV) suggests good stability against aggregation [14].

- Microscopy: Use optical or confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) to visually observe the microstructure of the emulsion, confirming droplet distribution, aggregation, or the presence of crystals that might destabilize the system [14].

Figure 2: Multi-technique approach for comprehensive emulsion stability assessment.

Mucosal Permeability

Q: What are the key anatomical and physiological factors limiting the permeability of my compound through the oral mucosa?

A: Permeability across the oral mucosa is primarily determined by the epithelium, which acts as the main barrier [15]. The key factors are:

- Epithelial Type: The oral cavity has regions with keratinized (e.g., hard palate) and non-keratinized epithelium (e.g., buccal, sublingual). Non-keratinized epithelium is generally thinner and more permeable, making the buccal and sublingual routes preferred for systemic delivery [15].

- Mucus Layer: A semipermeable barrier that can trap macromolecules and slow diffusion. Nanoparticles smaller than ~200 nm can diffuse through it more effectively [9].

- Enzymes and Efflux Transporters: Enterocytes contain metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP450) and efflux pumps like P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which can actively pump compounds back into the lumen, significantly reducing the absorbed fraction [9].

Q: Which ex vivo models are most suitable for studying drug permeability across the oral mucosa, and how do I ensure data reproducibility?

A: Ex vivo models using animal tissue are common, but reproducibility is a challenge due to variability in tissue thickness and viability [15] [16].

Experimental Protocol: Ex Vivo Permeability Study Using Franz Diffusion Cell

- Tissue Preparation: Obtain fresh porcine or rodent buccal mucosa. Carefully separate the epithelium from the underlying connective tissue. The thickness of the mucosa should be measured and recorded, as it is a critical variable [15] [16].

- Mounting: Mount the mucosal tissue between the donor and receptor compartments of a Franz diffusion cell, with the epithelial side facing the donor compartment. The receptor compartment should be filled with a suitable buffer (e.g., Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate solution) maintained at 37°C and continuously stirred [15].

- Sample Application: Apply the formulation containing your bioactive compound (e.g., solution, gel, patch) to the donor compartment.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw samples from the receptor compartment and replace with fresh buffer to maintain sink conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify the amount of permeated compound in the samples using a sensitive analytical method (e.g., HPLC, LC-MS).

- Data Normalization & Viability: To ensure reproducibility, normalize permeation data to a standard mucosal thickness using mathematical models, especially if tissue thickness varies significantly [16]. Assess tissue viability before and after the experiment using an assay like MTT to confirm barrier integrity was maintained [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability Enhancement Studies

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid-Based Carrier Components [9] [11] | Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), Lectihin, Polysorbates (Tweens) | Form the core and stabilize nanoemulsions, SNEDDS, and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). |

| Polymer-Based Carrier Components [9] [11] | Chitosan, Alginate, Zein, Whey Protein Isolate, Cellulose derivatives (e.g., HPMC) | Form polymeric nanoparticles, hydrogels, and micelles; provide mucoadhesion and controlled release. |

| Solubility & Stability Assay Tools [12] [13] | DMSO, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), NEPHELOstar Plus, Zetasizer | For preparing samples and conducting high-throughput solubility (nephelometry) and stability (zeta potential, DLS) screens. |

| Ex Vivo Permeability Model [15] | Porcine buccal mucosa, Franz diffusion cell, Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate buffer | Provides a biologically relevant model for studying and quantifying compound permeability. |

| Permeability Enhancers & Inhibitors [9] | P-gp inhibitors (e.g., Verapamil), Permeation enhancers (e.g., Chitosan) | Used in mechanistic studies to overcome efflux transport or temporarily increase mucosal permeability. |

| Diacetolol D7 | Diacetolol D7, MF:C16H24N2O4, MW:315.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Monoisobutyl Phthalate-d4 | Monoisobutyl Phthalate-d4, CAS:1219802-26-2, MF:C12H14O4, MW:226.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Impact of Food Matrix and Gastrointestinal Transformations on Bioaccessibility

For researchers and scientists focused on optimizing the bioavailability of functional food components, understanding the impact of the food matrix and gastrointestinal transformations on bioaccessibility is fundamental. Bioaccessibility, defined as the fraction of a compound released from the food matrix into the gastrointestinal tract and thus available for intestinal absorption, is the critical first step toward achieving biological efficacy [17] [18]. The complex interactions between bioactive compounds and other food components—such as proteins, dietary fibers, and lipids—can either enhance or inhibit this release, directly influencing the outcome of your experiments and the potential health benefits of the final product [19] [20]. This guide addresses specific experimental challenges and provides actionable methodologies to advance your research in functional food development.

Core Concepts: Food Matrix Effects

The food matrix is the complex assembly of nutrients and non-nutrients in a food structure that can physically entrap or chemically interact with bioactive compounds. Understanding these interactions is paramount for predicting and improving the bioaccessibility of your target compounds.

Key Mechanisms of Food Matrix Effects

| Mechanism | Impact on Bioaccessibility | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Complexation with Nutrients [19] | Significantly affected, either enhanced or reduced. Effects are polyphenol- and nutrient-specific. | Requires individual investigational approaches for each food/nutrient and phenolic compound pair. |

| Interaction with Dietary Fiber [19] | May reduce bioaccessibility by trapping compounds; some fibers may promote stability. | Necessary to characterize the specific type of fiber (e.g., cellulose, pectin, inulin) used in the model. |

| Interaction with Proteins [19] | Casein shown to significantly affect hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol permeability. | Consider the role of the protein corona when studying inorganic ENMs [20]. |

| Changes in GI Tract Physiology [19] | Alters luminal pH, enzyme capacity, bile salt content, and GI motility. | Fed vs. fasted state models will yield different results; state must be standardized. |

| Binding to Soil/Sediment Matrices [21] | Reduces metal bioaccessibility via sorption to clays, organic matter, and oxides. | Critical for assessing risk from contaminated foods; pore water concentration is a key indicator. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Employing standardized and harmonized methods is crucial for generating reproducible and comparable data on bioaccessibility. The following protocol is widely recognized in the field.

The INFOGEST Static In Vitro Digestion Model

This harmonized method simulates the human gastrointestinal process and is particularly suited for initial screening of bioaccessibility in functional food ingredients [18].

1. Preparation of Simulated Digestive Fluids Prepare Simulated Salivary Fluid (SSF), Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF), and Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF) as per the INFOGEST standardized recipe [19] [18]. For fed-state studies, use Fed State Simulated Gastric Fluid (FeSSGF) and Fed State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FeSSIF) [19].

2. Digestion Phases

- Gastric Phase: Mix the food sample with SGF and pepsin (e.g., 268 units/mL). Adjust pH to 3.0 and incubate for 60 minutes with constant agitation [18]. Sample at t=0 (G0) and t=60 (G60) minutes.

- Intestinal Phase: Transfer the gastric chyme to a vessel containing SIF, pancreatin (e.g., 16 units/mL trypsin activity), and bile salts (e.g., 1.38 mM bovine bile). Adjust pH to 6.0-7.0 and incubate for up to 120 minutes [18]. Sample at t=30 (I30), t=60 (I60), and t=120 (I120) minutes.

3. Sampling and Analysis Stop the enzymatic reaction at each time point (e.g., by snap-freezing at -80°C or using enzyme inhibitors). Centrifuge samples (e.g., ~10,000 g) to separate the bioaccessible fraction (supernatant) from the non-bioaccessible residue. Analyze the supernatant for your target bioactive compounds using appropriate techniques (HPLC, LC-MS) [17] [18].

Calculation:

Bioaccessibility (%) = (Amount of compound in supernatant / Total amount in original sample) × 100

Experimental Workflow for In Vitro Bioaccessibility

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my measured bioaccessibility lower than expected based on the total compound content in the food?

Potential Cause & Solution: The most common cause is strong binding or entrapment of the bioactive compound within the food matrix.

- Confirm Nutrient Interactions: Systematically test the effect of individual macronutrients. For instance, research shows casein and specific dietary fibers can significantly reduce the bioaccessibility of hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol from olive pomace extract [19].

- Analyze the Solid Residue: After centrifugation, analyze the non-bioaccessible pellet to determine the fraction of the compound that was not released. This can confirm physical entrapment.

- Optimize the Matrix: Consider food processing techniques (e.g., heating, fermentation, high-pressure processing) that can break down the matrix structure and enhance compound release.

FAQ 2: How do I account for the effect of other meal components during digestion assays?

Potential Cause & Solution: The presence of a full meal drastically alters gastrointestinal conditions.

- Use Fed-State Simulated Fluids: Replace standard SGF and SIF with Fed State Simulated Fluids (FeSSGF and FeSSIF). These fluids have different pH, buffer capacity, and composition (e.g., containing lecithin and taurocholate) that more accurately mimic the fed state [19].

- Incorporate a Standardized Food Model: Use a well-defined food model like the Standardized Food Model (SFM) in your experiments. This model often includes components like sodium caseinate dissolved in a phosphate buffer to simulate a protein-rich food background [19].

FAQ 3: My bioactive compound is unstable under gastrointestinal conditions. How can I accurately assess its bioaccessibility?

Potential Cause & Solution: Many phenolic compounds and vitamins can degrade at low pH or in the presence of enzymes and oxygen.

- Track Compound Degradation: Monitor not only the parent compound but also its degradation products or metabolites throughout the digestion process. An apparent stability might be due to the degradation of secoiridoids into hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol [19].

- Use Advanced In Vitro Models: Consider moving from static to semi-dynamic or dynamic in vitro models that can continuously remove digestion products, providing a more accurate picture of stability and absorption [17].

- Employ Encapsulation Strategies: Test the efficacy of delivery systems like cyclodextrins or lipid-based nanoparticles. Studies have shown that cyclodextrins can partially neutralize the negative effects of the OPE matrix on hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol permeability [19].

Visualizing the Bioaccessibility & Bioavailability Pathway

To systematically approach bioavailability optimization, it is essential to understand the entire pathway from ingestion to physiological effect.

Pathway from Food to Physiological Effect

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function in Bioaccessibility Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pepsin (porcine gastric mucosa) [19] [18] | Proteolytic enzyme for gastric digestion phase. | Simulates protein hydrolysis in the stomach in INFOGEST protocol. |

| Pancreatin (porcine pancreas) [19] [18] | Enzyme mixture containing trypsin, amylase, and lipase for intestinal digestion. | Simulates complex macronutrient digestion in the small intestine. |

| Bile Salts [19] [18] | Emulsify lipids, facilitating the solubilization of hydrophobic compounds. | Critical for the bioaccessibility of lipophilic bioactive compounds. |

| Caco-2 & HT29-MTX-E12 Cell Lines [19] [18] | Model the human intestinal epithelium for absorption studies. | Co-cultures mimic enterocytes and goblet cells for permeability assays. |

| Simulated Digestive Fluids (SSF, SGF, SIF) [19] [18] | Provide inorganic ions and electrolytes to mimic GI tract environment. | Essential for maintaining physiologically relevant pH and ionic strength. |

| Standardized Food Model (SFM) [19] | Provides a consistent background food matrix for fed-state studies. | Used to investigate nutrient interactions under standardized conditions. |

| Hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) [19] | Molecular encapsulation agent to improve solubility and stability. | Shown to enhance the permeability of hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol [19]. |

| Pipecolic acid-d9 | Pipecolic acid-d9, CAS:790612-94-1, MF:C6H11NO2, MW:138.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| trans-Isoferulic acid-d3 | trans-Isoferulic acid-d3, CAS:1028203-97-5, MF:C10H10O4, MW:197.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Octacosanol is a long-chain fatty alcohol (C₂₈H₅₈O) found naturally in sugarcane wax, wheat germ oil, rice bran oil, and beeswax [22]. It exhibits a broad spectrum of documented biological activities, including anti-fatigue, anti-inflammatory, hypolipidemic, antioxidant, and antitumor properties [22]. Despite this significant therapeutic potential, its practical application in functional foods and pharmaceuticals is severely limited by one critical factor: extremely low oral bioavailability [22].

The high hydrophobicity of octacosanol results in poor water solubility, which subsequently leads to low bioaccessibility in the gastrointestinal tract, limited intestinal absorption, and inefficient systemic distribution [22]. Recent pharmacokinetic studies reveal that after gavage administration of octacosanol to Sprague-Dawley rats at a dose of 80 mg/kg body weight, the serum concentration reached only 417 ng/mL and liver levels were merely 445 ng/g [22]. This fundamental challenge of delivering sufficient concentrations to target sites necessitates advanced formulation strategies to unlock octacosanol's full clinical potential.

Quantitative Bioavailability Assessment

Table 1: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Unformulated Octacosanol

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Concentration | 417 ng/mL | 80 mg/kg dose in Sprague-Dawley rats, measured at 1 hour [22] |

| Liver Concentration | 445 ng/g | 80 mg/kg dose in Sprague-Dawley rats, measured at 1 hour [22] |

| Plasma Concentration | ~30 ng/mL | 60 mg/kg dose in rats [23] |

| Fecal Excretion | 31-33% | Indicator of poor absorption [23] |

Table 2: Bioavailability Enhancement Using Delivery Systems

| Formulation Strategy | Key Performance Metrics | Bioavailability Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| O/W Nanoemulsion [23] | Particle size: 71.54 nm; PDI: 0.195; Zeta potential: -3.98 mV | Significant enhancement in solubility and intestinal absorption efficiency |

| Microencapsulation (GA-Malt-PPI) [24] | Encapsulation Efficiency: >90%; Sustained release profile in simulated GI tract | Improved efficacy in alleviating HFD-induced obesity symptoms in mice compared to octacosanol monomer |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: How can I improve the water dispersibility of octacosanol for in vitro assays?

Challenge: Octacosanol's high hydrophobicity causes precipitation in aqueous experimental systems, leading to inconsistent results and inaccurate bioactivity measurements.

Solutions:

- Microencapsulation: Use a composite shell system with gum Arabic (GA), maltose (Malt), and pea protein isolate (PPI) in a ratio of 2:1:2 with a core-to-shell ratio of 1:7.5 [24]. Emulsify at 70°C and pH 9.0 for optimal results.

- Nanoemulsion Formulation: Prepare oil-in-water (O/W) nanoemulsions using PEG-40 hydrogenated castor oil (PHCO) as surfactant and ethyl acetate as co-surfactant [23]. This green, low-energy method significantly enhances dispersibility.

- Protein Complexation: Form nanocomplexes with soy protein isolate (SPI), which has demonstrated improved stability of octacosanol in neutral conditions [22].

FAQ 2: What methods effectively enhance octacosanol absorption in pharmacokinetic studies?

Challenge: Despite promising in vitro activity, octacosanol shows poor in vivo performance due to limited intestinal absorption and extensive pre-systemic metabolism.

Solutions:

- Nanoemulsion Delivery: The O/W nanoemulsion system significantly improves intestinal absorption efficiency as demonstrated by both in vitro digestion models and in vivo distribution studies [23].

- Sustained-Release Microcapsules: The GA-Malt-PPI microcapsule system provides sustained release of octacosanol throughout the gastrointestinal tract, reducing premature metabolism and enhancing systemic exposure [24].

- Nanocrystal Technology: Previous research has developed modified octacosanol nanocrystals that improve dissolution rate and oral bioavailability through increased surface area [22].

FAQ 3: How can I stabilize octacosanol during storage and processing?

Challenge: Octacosanol formulations may face physical instability, degradation, or loss of activity during storage and processing.

Solutions:

- Optimized Nanoemulsion Parameters: Formulate nanoemulsions that maintain stability across varying temperatures (4-60°C), pH levels (4-9), NaCl concentrations (0-200 mM), and sucrose content (0-10%) [23].

- Composite Shell Systems: The GA-Malt-PPI microcapsule significantly improves storage stability compared to unencapsulated octacosanol, maintaining activity over extended periods [24].

- Antioxidant Protection: Incorporate appropriate antioxidants into formulations, as octacosanol's stability can be compromised by oxidative degradation under certain conditions [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Green Synthesis of O/W Nanoemulsion for Octacosanol

Objective: To prepare a stable oil-in-water nanoemulsion to enhance octacosanol solubility and bioavailability using a simple, low-energy method [23].

Materials:

- Octacosanol (purity ≥90%)

- PEG-40 hydrogenated castor oil (PHCO) as surfactant

- Ethyl acetate as co-surfactant

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve octacosanol in ethyl acetate to form the oil phase.

- Surfactant Addition: Add PHCO to the oil phase at an optimized ratio (octacosanol:ethyl acetate:PHCO = 1:9:10).

- Emulsification: Slowly add the organic phase to deionized water with continuous stirring at room temperature.

- Homogenization: Process the mixture using a homogenizer at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes to form a coarse emulsion.

- Particle Reduction: Sonicate the emulsion using a probe sonicator at 400W for 10 minutes (pulse mode: 5s on, 2s off) while maintaining temperature in an ice bath.

- Characterization: Determine particle size (target: ~70 nm), PDI (target: <0.2), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering.

Validation:

- Confirm stability under various environmental conditions (temperature, pH, ionic strength)

- Evaluate in vitro digestibility using simulated gastrointestinal fluids

- Assess cellular uptake using Caco-2 cell models

Protocol 2: Microencapsulation of Octacosanol Using GA-Malt-PPI Complex

Objective: To develop sustained-release microcapsules that protect octacosanol from gastrointestinal metabolism and improve its efficacy [24].

Materials:

- Octacosanol (purity ≥90%)

- Gum Arabic (GA)

- Maltose (Malt)

- Pea protein isolate (PPI)

- pH adjustment solutions (HCl and NaOH)

Procedure:

- Shell Solution Preparation: Dissolve GA, Malt, and PPI in deionized water at 60°C with mass ratio GA:Malt:PPI = 2:1:2.

- Core Addition: Add octacosanol (core material) to the GA-Malt-PPI solution with continuous stirring to achieve core-to-shell ratio of 1:7.5.

- Emulsification: Homogenize the mixture twice using a high-speed homogenizer.

- pH Optimization: Adjust pH to 9.0 and maintain for 30 seconds to expose hydrophobic groups on PPI.

- Temperature Conditioning: Heat the emulsion to 70°C for 30 seconds with continuous mixing.

- Neutralization: Adjust pH back to neutral (7.0).

- Characterization: Determine encapsulation efficiency (>90% target), loading capacity, particle size, and zeta potential.

Quality Control:

- Monitor sustained release profile using in vitro simulated gastrointestinal tract model

- Evaluate storage stability at different temperatures and humidity conditions

- Confirm in vivo efficacy using HFD-induced obesity mouse model

Visualization of Key Concepts

Diagram 1: Octacosanol Absorption Pathway

Diagram 2: Nanoemulsion Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Octacosanol Bioavailability Research

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| PEG-40 Hydrogenated Castor Oil (PHCO) | Pharmaceutical grade, high purity [23] | Non-ionic surfactant for nanoemulsion formation; provides high biosafety and stabilization |

| Gum Arabic-Maltose-Pea Protein Isolate (GA-Malt-PPI) | Food grade, optimized ratio 2:1:2 [24] | Composite shell material for microencapsulation; enables sustained release in GI tract |

| Ethyl Acetate | High purity, low toxicity solvent (LDâ‚…â‚€ > 5600 mg/kg in rats) [23] | Co-surfactant in nanoemulsion preparation; offers moderate polarity and biodegradability |

| In Vitro Digestion Model Components | Pepsin, pancreatin, bile salts, electrolytes [24] | Simulated gastrointestinal fluids for predicting release profiles and absorption potential |

| Analytical Standards | Octacosanol reference standard (≥90% purity) [24] | Quantification of octacosanol in biological samples and formulation quality control |

| Piperaquine D6 | Piperaquine D6 | Piperaquine D6 CAS 1261394-71-1 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for antimalarial pharmacokinetics research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| L-5-Hydroxytryptophan-d4 | L-5-Hydroxytryptophan-d4, CAS:1246818-91-6, MF:C11H12N2O3, MW:224.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

The field of octacosanol bioavailability enhancement is rapidly evolving with several promising technological approaches emerging beyond the formulation strategies discussed above. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are now being applied to predict optimal formulation parameters, absorption pathways, and even individual metabolic responses to octacosanol supplementation [7]. These computational approaches can significantly accelerate the development of next-generation delivery systems by modeling complex structure-activity relationships and predicting in vivo performance based on in vitro data.

Additionally, innovative encapsulation technologies including solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, and hybrid drug nanocrystals represent promising avenues for further improving octacosanol bioavailability [22]. The integration of precision nutrition concepts, which account for inter-individual variability in genetics, microbiome composition, and metabolic phenotypes, may enable the development of personalized octacosanol formulations optimized for specific population subgroups [7]. As these advanced technologies mature, they will undoubtedly contribute to overcoming the longstanding bioavailability challenges that have limited the clinical translation of octacosanol's promising biological activities.

Gut Microbiota's Role in the Biotransformation of Phenolics and Polysaccharides

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Low Metabolite Yield in Biotransformation Assays

Problem: After incubating phenolic compounds or polysaccharides with gut microbiota, expected metabolite concentrations are low or undetectable.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal microbial community | Use standardized, metabolically active fecal samples; verify donor health and avoid long-term antibiotic use [25]. |

| Incorrect substrate preparation | For polyphenols: use glycosylated forms; for polysaccharides: ensure proper solubility and molecular weight [25] [26]. |

| Oxygen contamination in anaerobic system | Strictly maintain anaerobic conditions (e.g., anaerobic chamber, nitrogen gas flushing) [25]. |

| Insufficient fermentation time | Extend incubation; polysaccharide fermentation to SCFAs may require 24-72 hours [27]. |

Issue 2: High Variability in Metabolite Profiles Between Replicates

Problem: Significant inconsistency in biotransformation products across technical or biological replicates.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent microbiota source | Pool samples from multiple donors or use standardized, commercially available bacterial consortia [28]. |

| Uncontrolled pH during fermentation | Use pH-controlled bioreactors or include sufficient buffering capacity in media [27]. |

| Degradation of parent compounds | Verify substrate stability under experimental conditions; add protease inhibitors if necessary [29]. |

Issue 3: Poor Bacterial Survival or Activity

Problem: Microbiota viability decreases significantly during the biotransformation assay.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Toxic compound accumulation | Monitor and remove inhibitory metabolites (e.g., lactate) via medium exchange in continuous systems [29]. |

| Inadequate nutrient media | Use rich, complex media supporting diverse bacteria; consider adding mucin or other gut-specific factors [28]. |

| Incorrect temperature | Maintain 37°C, the optimal temperature for human gut microbiota [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Biotransformation of Phenolic Compounds

Objective: To assess the conversion of dietary polyphenols into bioavailable metabolites by human gut microbiota.

Materials:

- Fecal inoculum: Fresh or frozen fecal samples from healthy donors, diluted in anaerobic phosphate-buffered saline [25]

- Substrate: Polyphenol compound (e.g., grape seed extract, chlorogenic acid) [25]

- Anaerobic medium: Such as YCFA or M2GSC, pre-reduced for 24 hours [25]

- Equipment: Anaerobic workstation, shaking incubator, centrifuge, UPLC-MS for analysis [25]

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Homogenize 10% (w/v) feces in anaerobic PBS, centrifuge to remove large particles [25].

- Reaction Setup: In anaerobic tubes, combine 10% inoculum, 80% anaerobic medium, and 10% polyphenol substrate (1-2 mg/mL). Include no-substrate controls [25].

- Incubation: Ferment at 37°C with constant shaking (150 rpm) for 24-48 hours under anaerobic conditions [25].

- Sampling: Collect samples at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours for metabolite and bacterial analysis [25].

- Analysis:

Protocol 2: Polysaccharide Fermentation and SCFA Analysis

Objective: To evaluate the prebiotic potential of polysaccharides and quantify short-chain fatty acid production.

Materials:

- Polysaccharide substrate: Purified polysaccharides (e.g., from mushrooms, marine organisms) [26]

- SCFA standards: Acetate, propionate, butyrate for calibration curves [27]

- Equipment: GC-FID system, anaerobic fermentation system, pH meter [26]

Methodology:

- Polysaccharide Purification: Extract using hot water or UPE, deproteinize, purify via column chromatography [26].

- Fermentation: Incolate 1% (w/v) polysaccharide with fecal inoculum in anaerobic medium for 48 hours [26].

- SCFA Quantification:

- Microbiota Analysis: Monitor enrichment of specific taxa (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Roseburia) via 16S rRNA sequencing [26].

Mechanisms and Pathways

The gut microbiota enhances the bioavailability of dietary compounds through four primary pathways. Pathway 1 involves direct biotransformation of parent compounds into beneficial metabolites. Pathway 2 occurs when non-parent components trigger microbial metabolism to produce additional beneficial molecules. In Pathway 3, gut microbiota modulation decreases the production of detrimental metabolites. Pathway 4 involves inhibiting specific bacteria that would otherwise transform parent drugs into inactive compounds [27].

Fig. 1: Four pathways of gut microbiota-mediated bioavailability. Pathway 1: Direct biotransformation; Pathway 2: Non-parent enhanced metabolism; Pathway 3: Reduced detrimental metabolites; Pathway 4: Prevented inactivation [27].

Polyphenol and polysaccharide metabolism follows distinct but complementary pathways. Polyphenols undergo extensive microbial modification including deglycosylation, ring fission, and conversion to aromatic acids, while polysaccharides are fermented to SCFAs which provide systemic health benefits [25] [27].

Fig. 2: Microbial biotransformation of phenolics and polysaccharides. Gut bacterial enzymes convert dietary compounds into bioactive metabolites with systemic health effects [25] [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does interindividual variability in gut microbiota affect biotransformation studies? Significant interpersonal differences in microbial composition dramatically impact metabolic outcomes. Studies show individuals with higher abundances of Enterobacteriaceae and Fusobacteria metabolize quercetin more efficiently, while Surreellaceae and Oscillospiraceae are negatively correlated with its metabolism. For robust experiments, use pooled samples from multiple donors or characterize donor microbiota to account for this variability [25].

Q2: What are the key bacterial species involved in polyphenol and polysaccharide metabolism? Critical taxa include:

- Polyphenol metabolism: Eubacterium ramulus (ring fission), Enterobacteria spp. (quercetin conversion), Lactobacillus plantarum (increases 3-HPPA production) [25]

- Polysaccharide metabolism: Bifidobacterium spp. (fiber degradation), Ruminococcus spp., Eubacterium spp. (butyrate production) [25] [26]

- SCFA production: Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. (butyrate), Bacteroides spp. (acetate, propionate) [27]

Q3: How can I improve the detection of microbial metabolites in complex samples?

- Sample preparation: Use solid-phase extraction or protein precipitation before analysis [25]

- Analytical methods: Employ UPLC-MS/MS with multiple reaction monitoring for sensitive quantification [25]

- Derivatization: For SCFAs, consider derivatization for improved GC separation and detection [27]

- Internal standards: Use stable isotope-labeled analogs of target metabolites for accurate quantification [25]

Q4: What controls are essential for interpreting biotransformation experiments?

- No-substrate controls: Account for metabolites from endogenous sources [25]

- No-inoculum controls: Assess non-enzymatic degradation of substrates [25]

- Heat-killed inoculum: Confirm microbial activity is required for biotransformation [25]

- Reference compounds: Use known metabolites to verify identification and quantify recovery [27]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Gut Microbiota | Provides consistent metabolic capacity for screening; from companies like ATCC | Verify metabolic competence for specific substrates; check viability after thawing [25] |

| Anaerobic Culture Systems | Maintains obligate anaerobes; essential for representative fermentation | Use anaerobic chambers or sealed systems with oxygen indicators; pre-reduce media [25] |

| Reference Metabolites | Quantification standards for microbial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, phenolic acids) | Source certified standards; prepare fresh stock solutions; include internal standards [25] [27] |

| Polysaccharide Purification Kits | Isolate high-purity polysaccharides from natural sources | Confirm structural integrity after purification; check for protein contamination [26] |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Kits | Monitor microbial community changes during biotransformation | Select appropriate variable region; include positive controls; plan bioinformatics pipeline [25] |

| UPLC-MS/MS Systems | Sensitive detection and quantification of diverse microbial metabolites | Optimize MRM transitions for target analytes; use HILIC and reverse-phase methods [25] |

| Amlodipine-d4 | Amlodipine-d4 Deuterated Standard|1 | Amlodipine-d4 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for precise MS quantification in ADME studies. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Crystal Violet-d6 | Crystal Violet-d6, CAS:1266676-01-0, MF:C25H30ClN3, MW:414.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites from Phenolic and Polysaccharide Biotransformation

| Parent Compound | Key Microbial Metabolites | Concentration Range | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grape Seed Polyphenols | 3-HBA, 3-HPP | Detected in brain tissue | Promotes resilience against cognitive decline [25] |

| Green Tea Catechins | Polyhydroxyphenyl-γ-valerolactones | 10x higher than other conjugates in urine | Potential protection against oxidative damage in adipocytes [25] |

| Mulberry Anthocyanins | Protocatechuic, vanillic, p-coumeric acids | Varies with microbiota composition | Dependent on specific gut bacteria for conversion [25] |

| Dietary Polysaccharides | Acetate, propionate, butyrate (SCFAs) | mM range in gut lumen | Immune modulation, energy metabolism, gut barrier function [27] |

Table 2: Optimized Experimental Conditions for Biotransformation Assays

| Parameter | Polyphenol Studies | Polysaccharide Studies | Critical Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation Time | 24-48 hours | 48-72 hours | SCFA production increases with longer fermentation [25] [27] |

| Substrate Concentration | 1-2 mg/mL | 1% (w/v) | Higher concentrations may inhibit microbial growth [25] [26] |

| Inoculum Density | 10% (v/v) | 10% (v/v) | Standardized across experiments for reproducibility [25] |

| Key Analytical Methods | UPLC-MS/MS for phenolic acids | GC-FID for SCFAs | Method validation essential for accurate quantification [25] [27] |

Innovative Formulation Technologies: Engineering Enhanced Delivery Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using nanoencapsulation for functional food ingredients? Nanoencapsulation enhances the stability, solubility, and bioavailability of functional food ingredients, many of which are hydrophobic and unstable in harsh processing or digestive conditions [30]. It protects bioactive compounds from environmental degradation (e.g., light, oxygen, pH fluctuations) and enables controlled or targeted release at the desired site in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby improving their therapeutic efficacy [31].

Q2: How do I select the most suitable nanocarrier for my bioactive compound? The selection depends on the physicochemical properties of your bioactive compound (hydrophilic vs. hydrophobic) and your application goals [32] [31]:

- Liposomes are ideal for encapsulating both hydrophilic (in the aqueous core) and hydrophobic (in the lipid bilayer) compounds [32] [33].

- Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) offer high biocompatibility and are particularly suitable for lipophilic compounds, with NLCs providing improved drug loading capacity over SLNs by using a blend of solid and liquid lipids [32].

- Polymeric Nanoparticles (e.g., those made from PLGA, chitosan) offer high structural precision, tunable release profiles, and protection against enzymatic degradation [34].

Q3: What are the most critical parameters to characterize for nanocarrier formulations? Key parameters include [35]:

- Size and Size Distribution: Affects stability, cellular uptake, and biodistribution.

- Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): Indicates colloidal stability and influences interaction with biological membranes.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Measures the fraction of successfully encapsulated bioactive.

- Physical Stability: Assesses aggregation or degradation under storage conditions.

- Sterility and Endotoxin Levels: Critical for in vivo applications to avoid immunogenic reactions [35].

Q4: A common problem is the instability of nanoemulsions. How can this be addressed? Nanoemulsion instability can be mitigated by optimizing the emulsifier type and concentration, controlling processing conditions (e.g., homogenization pressure, energy input), and formulating with stabilizers like weighting or ripening inhibitors [32]. High-pressure homogenization and ultrasonication are common methods to produce stable nanoemulsions with small droplet sizes (≤100 nm) [32].

Q5: What are the major challenges in scaling up nanoencapsulation processes for industrial production? Challenges include ensuring batch-to-batch consistency, achieving cost-effective production at large scale, maintaining the physicochemical properties (size, PDI, encapsulation efficiency) during scale-up, and meeting stringent regulatory and safety requirements for food or pharmaceutical applications [35] [34]. Techniques like high-pressure homogenization are easier to scale than methods like ionic gelation [32] [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Synthesis and Purification Issues

The table below summarizes frequent issues encountered during the preparation of nanocarriers, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Nanocarrier Synthesis and Purification

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Large Particle Size & High Polydispersity [35] | Inefficient emulsification or homogenization; Aggregation during synthesis; Incorrect lipid:polymer ratio. | Increase homogenization pressure/cycles; Use a more efficient surfactant; Optimize solvent displacement parameters; Filter through a sterile membrane (e.g., 0.45 or 0.22 µm). |

| Low Encapsulation Efficiency [32] | Rapid precipitation of bioactive; Leakage during synthesis; Mismatch between bioactive lipophilicity and core material. | Modify the core composition (e.g., use NLCs over SLNs); Add the bioactive at a specific stage in the process; Increase the concentration of the wall material. |

| Endotoxin Contamination [35] | Use of non-sterile reagents/equipment; Contaminated water (not LAL-grade/pyrogen-free); Synthesis in a non-aseptic environment. | Work under a biological safety cabinet; Use depyrogenated glassware and sterile filters; Test all reagents, especially water and commercial starting materials, for endotoxin. |

| Physical Instability (Aggregation/Ostwald Ripening) [32] | Low zeta potential (inadequate surface charge); Inadequate stabilizer; Storage at high temperatures. | Optimize pH and ionic strength of the dispersion medium; Incorporate steric stabilizers (e.g., PEG); Store formulations at 4°C. |

Characterization and Analytical Challenges

Accurate characterization under biologically relevant conditions is essential for meaningful data.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Nanocarrier Characterization

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Sizing Results [35] | Technique-specific artifacts (e.g., DLS overweighs large aggregates); Nanoparticle interference in assays; Analysis in non-physiological buffers. | Use multiple techniques (e.g., DLS, TEM, AFM) for cross-verification; Characterize in physiologically relevant media (e.g., plasma, PBS); Perform appropriate controls for assay interference. |

| Interference in LAL Endotoxin Assay [35] | Colored formulations interfere with chromogenic assays; Turbid samples interfere with turbidity assays; Cellulose-based filters introduce beta-glucans. | Switch LAL assay format (e.g., from chromogenic to gel-clot); Use Glucashield buffer to negate beta-glucan interference; Employ a recombinant Factor C assay. |

| Poor In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation | In vitro assays not mimicking in vivo conditions (e.g., protein corona formation); Premature release in simulated GI fluids. | Include biomolecule-containing media (e.g., serum) in stability studies; Use more complex in vitro digestion models (e.g., TIM-1) to better predict bioavailability [30]. |

Experimental Protocols

This is a standard method for producing multi-lamellar vesicles (MLVs) that can be downsized to small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs).

Objective: To prepare nanoliposomes for the encapsulation of hydrophilic or hydrophobic bioactive compounds.

Materials:

- Phospholipid (e.g., Soy phosphatidylcholine)

- Cholesterol (to enhance membrane stability)

- Chloroform or other organic solvent

- Rotary Evaporator with a round-bottom flask

- Water Bath Sonicator or High-Pressure Homogenizer

- Buffer Solution (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, PBS, for hydration)

Method:

- Dissolution: Dissolve the phospholipid and cholesterol (e.g., in a 7:3 molar ratio) in chloroform in a round-bottom flask.

- Thin Film Formation: Attach the flask to a rotary evaporator. Evaporate the solvent under reduced pressure at a temperature above the lipid transition temperature (e.g., 40-45°C for soy PC) to form a thin, uniform lipid film on the inner wall of the flask.

- Hydration: Continue rotation under vacuum for at least 30 minutes to remove any trace of solvent. Hydrate the dry lipid film with an aqueous buffer (pre-heated to above the lipid transition temperature) containing the hydrophilic bioactive to be encapsulated. Rotate gently for 1 hour to hydrate and form multilamellar vesicles (MLVs).

- Size Reduction: Sonicate the MLV dispersion using a probe sonicator in an ice bath (to prevent overheating) for 10-30 minutes until the solution becomes translucent. Alternatively, extrude the suspension through polycarbonate membranes (e.g., 100 nm pore size) using a high-pressure extruder to obtain a uniform population of SUVs.

- Purification: Separate the non-encapsulated material using dialysis, size exclusion chromatography, or centrifugation.

Visualization: Liposome Preparation Workflow

This is a robust and scalable method for producing SLNs.

Objective: To produce solid lipid nanoparticles for the encapsulation of lipophilic bioactives.

Materials:

- Solid Lipid (e.g., Glyceryl monostearate, Compritol)

- Surfactant (e.g., Poloxamer 188, Tween 80)

- High-Pressure Homogenizer

- Heating Mantles

Method:

- Melt Dispersion: Melt the solid lipid at approximately 5-10°C above its melting point.

- Aqueous Phase: Heat the aqueous surfactant solution to the same temperature as the lipid melt.

- Pre-Emulsification: Add the hot aqueous phase to the molten lipid under high-speed stirring to form a coarse pre-emulsion.

- High-Pressure Homogenization: Pass the hot pre-emulsion through a high-pressure homogenizer for 3-5 cycles at a pressure of 500-1500 bar while maintaining the temperature.

- Cooling and Crystallization: Allow the resulting nanoemulsion to cool down to room temperature (or 4°C) under mild stirring. The lipid droplets solidify, forming SLNs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanoencapsulation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phospholipids (e.g., Phosphatidylcholine) | Primary building block for liposomes and nanoliposomes [33]. | Source (soy, egg) and purity affect consistency and stability. Use hydrogenated phospholipids for higher oxidative stability. |

| Solid Lipids (e.g., Compritol, Precirol) | Form the solid matrix of SLNs and NLCs [32]. | The crystalline structure of the lipid impacts drug loading and release kinetics. |

| Biodegradable Polymers (e.g., PLGA, Chitosan) | Form the core of polymeric nanoparticles [34]. | Molecular weight, copolymer ratio (for PLGA), and degree of deacetylation (for chitosan) determine degradation and release profiles. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Poloxamer 188, Tween 80) | Stabilize nanoemulsions and prevent aggregation of nanoparticles during and after formation [32]. | Must be non-toxic and approved for the intended application (food/pharma). HLB value determines suitability for O/W or W/O systems. |

| Cholesterol | Incorporated into lipid bilayers (liposomes) to modify membrane fluidity and enhance physical stability [33]. | Typically used at a molar ratio of 0.1:1 to 0.5:1 (Cholesterol:Phospholipid). |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., Tripolyphosphate - TPP) | Used in ionic gelation to cross-link polymers like chitosan, forming stable nanoparticles [36]. | Concentration and addition rate control particle size and uniformity. |

| Salicyluric acid-13C2,15N | 2-Hydroxy Hippuric Acid-13C2,15N Isotope | 2-Hydroxy Hippuric Acid-13C2,15N, a stable isotope-labeled tracer for metabolic and proteomic research. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or human use. |

| Trimethylammonium chloride-d9 | Trimethylammonium chloride-d9, CAS:18856-86-5, MF:C3H10ClN, MW:104.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Decision Pathway for Nanocarrier Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate nanocarrier system based on the properties of the bioactive compound and the desired release profile, all within the context of optimizing bioavailability.

Visualization: Nanocarrier Selection Pathway

Micellar Solubilization and Emulsion-Based Delivery for Lipophilic Compounds

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my micellar formulation precipitating, and how can I improve its stability?

A: Precipitation often occurs due to drug loading exceeding the solubilization capacity of the micelles or instability upon dilution. To address this:

- Check Drug Loading: Ensure the drug concentration does not surpass the capacity of the micellar core. The solubilized amount should be determined experimentally in the specific surfactant system [37].

- Optimize Surfactant Combination: Use mixed surfactant systems. Combining ionic and non-ionic surfactants can improve micellar stability and drug loading capacity [38].

- Consider Hydrophilic Corona: Incorporate polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) in the shell. A PEG corona provides steric stabilization, reducing micelle aggregation and disassembly upon dilution, which is a common cause of precipitation [39].

Q2: My emulsion-based delivery system has a low drug encapsulation efficiency. What factors should I investigate?

A: Low encapsulation efficiency for lipophilic compounds typically stems from suboptimal formulation or process parameters.

- Match Drug and Oil Phase: Select an oil in which the drug has high solubility. Pre-formulation solubility studies in various oils are crucial [40] [41].

- Optimize Emulsifier Type and Concentration: The emulsifier must sufficiently reduce interfacial tension. Non-ionic surfactants like Tweens (polysorbates) are often used. Ensure the concentration is well above the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) for effective nanoemulsion formation [37] [42].

- Control Processing Conditions: Use high-energy methods like high-pressure homogenization to achieve smaller droplet sizes (r < 100 nm), which can enhance encapsulation and prevent drug crystallization [40].

Q3: How can I experimentally determine the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) of a surfactant, and why is it important?

A: The CMC is a critical parameter as it indicates the minimum surfactant concentration required for spontaneous micelle formation, which directly impacts drug solubilization.

- Standard Techniques: Two common methods are:

- Surface Tension Measurement: Plot surface tension against surfactant concentration. The CMC is identified at the point where the surface tension stops decreasing and forms a plateau [38].

- Conductivity Measurement: For ionic surfactants, plot specific conductivity against concentration. A distinct change in the slope of the plot indicates the CMC [38].

- Importance: Formulations should operate at concentrations above the CMC to ensure micelles are present to solubilize the drug. A low CMC is generally preferred for in vivo stability, as it prevents micellar disassembly upon dilution in the biological system [39].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

The table below summarizes specific problems, their potential causes, and evidence-based solutions.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Drug Solubilization | Poor compatibility between drug and micelle core; Surfactant below CMC; Incorrect surfactant type. | Conduct drug solubility screening in different oils/surfactants [41]; Increase surfactant concentration above CMC [37]; Use surfactants with longer hydrophobic chains for larger micellar cores [37]. |

| Micelle / Nanoemulsion Instability (Aggregation) | Inadequate steric or electrostatic stabilization; High polydispersity; Dilution in physiological fluids. | Incorporate a PEG corona for steric hindrance [39]; Use charged surfactants (e.g., SDS) for electrostatic repulsion [38]; Employ precise homogenization techniques for uniform droplet size [40]. |

| Poor Bioavailability Despite High Drug Loading | Rapid drug precipitation in GI tract; Instability in pH gradients; Poor permeability. | Integrate polymers to increase kinetic stability; Use lipid-based systems (e.g., SNEDDS) that maintain drug in a solubilized state [9] [41]; Add permeability enhancers (e.g., bio-surfactants) [42]. |

| Drug Crystallization in Emulsion | Drug concentration exceeds solubility in carrier oil at storage/body temperature; Insufficient emulsifier. | Select an oil with higher drug solubility capacity [40]; Add co-solvents (e.g., ethanol, PEG) to the oil phase to enhance drug loading [40] [41]. |

Experimental Protocols for Formulation and Characterization

Protocol: Determination of Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC)

Objective: To determine the CMC of a surfactant using the surface tension method [38].

Materials:

- Surfactant solution of varying concentrations

- Surface tensiometer (e.g., Du Noüy ring or Wilhelmy plate)

- Thermostatted water bath

- Glassware

Methodology:

- Prepare a series of surfactant solutions with concentrations spanning a wide range (e.g., 0.1 mM to 10 mM).

- Equilibrate all solutions at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C) using a water bath.

- Measure the surface tension of each solution, starting from the most dilute to the most concentrated.

- Plot the surface tension (y-axis) against the logarithm of surfactant concentration (x-axis).

- Identify the CMC as the concentration at the intersection of the two linear segments of the plot—the point where the surface tension ceases its sharp decline.

Diagram: CMC Determination Workflow

Protocol: Preparation and Characterization of a Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System (SNEDDS)

Objective: To formulate a SNEDDS to enhance the solubility and dissolution of a poorly water-soluble drug like Felodipine [41].

Materials:

- Lipophilic drug (e.g., Felodipine)

- Oils (e.g., cinnamon oil, oleic acid, isopropyl myristate)

- Surfactants (e.g., Tween 80, Tween 20)

- Co-surfactants/Co-solvents (e.g., PEG 400, ethanol, propylene glycol)

Methodology:

- Solubility Screening: Use the shake-flask method to determine the drug's equilibrium solubility in various oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants. Select the components that yield the highest drug solubility.

- Construction of Pseudo-Ternary Phase Diagram:

- Prepare mixtures of oil, surfactant, and co-surfactant (S~mix~) at different weight ratios (e.g., 1:1, 2:1, 3:1).

- Titrate these mixtures with aqueous phase (water) under gentle vortexing.

- After each addition, note the visual appearance (clear, transparent, or turbid) to identify the self-nanoemulsifying region.

- Plot the diagram using software to visualize the stable nanoemulsion zone.

- Formulation of SNEDDS: From the nanoemulsion region on the phase diagram, select a specific composition. Dissolve the drug in the isotropic mixture of oil, surfactant, and co-surfactant.

- Characterization of SNEDDS:

- Droplet Size Analysis: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to confirm the formation of nano-sized droplets (typically < 100 nm).

- In Vitro Dissolution Study: Compare the drug release profile of the SNEDDS formulation against the pure drug using a dissolution apparatus. A successful SNEDDS should release over 95% of the drug within a short time (e.g., 20 minutes) [41].

Diagram: SNEDDS Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for developing micellar and emulsion-based delivery systems.

| Category | Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Surfactants | Polysorbates (Tween 20, Tween 80) | Non-ionic surfactants; commonly used for forming micelles and stabilizing nanoemulsions. They provide a good safety profile and effective reduction of interfacial tension [37] [41]. |

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | Anionic surfactant; useful for imparting a negative charge to droplets, preventing aggregation via electrostatic repulsion. Also used in solubility studies [37] [42]. | |

| Block Co-polymers (e.g., PEG-PLA, PEG-PCL) | Form polymeric micelles with a hydrophobic core (e.g., PLA, PCL) and a hydrophilic PEG corona. They offer low CMC, high stability, and prolonged circulation time [39]. | |

| Oils / Lipid Phases | Medium-Chain Triglycerides (MCT) | Commonly used as the oil phase in SNEDDS and nanoemulsions due to their good solubilizing capacity and ability to form fine dispersions [40] [41]. |

| Oleic Acid | A long-chain fatty acid; acts as an oil phase and can also serve as a permeability enhancer [41]. | |

| Co-Solvents / Co-Surfactants | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG 400) | A water-soluble co-solvent that enhances drug solubility in the pre-concentrate and can modify the viscosity of the system, aiding emulsification [41]. |

| Ethanol / Propylene Glycol | Short-chain co-solvents that increase the solvent capacity of the formulation and facilitate the formation of a microemulsion by penetrating the surfactant film [42] [41]. | |

| Characterization Tools | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Instrumental technique for determining the particle size, size distribution (PDI), and zeta potential of micelles and nanoemulsions [39] [42]. |

| Surface Tensiometer | Key instrument for determining the CMC of surfactants and assessing the effectiveness of emulsifiers [38]. | |

| Valorphin | Valorphin, CAS:144313-54-2, MF:C44H60N8O12, MW:893.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Intedanib-d3 | Intedanib-d3 | Intedanib-d3 is a deuterated internal standard for LC-MS quantification of nintedanib in pharmacokinetic studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Cyclodextrin Complexation and Hydrophilic Carrier Systems

Within research aimed at optimizing the bioavailability of functional food components, cyclodextrin (CD) complexation stands as a pivotal technology. These cyclic oligosaccharides possess a unique structure—a hydrophilic exterior and a hydrophobic interior cavity—that enables them to form inclusion complexes with a wide range of hydrophobic bioactive compounds [43] [44]. This interaction is fundamental to overcoming the primary challenge of poor water solubility, which severely limits the absorption and efficacy of many nutraceuticals [43] [45]. By enhancing solubility, stability, and bioavailability, cyclodextrin-based carrier systems directly contribute to developing more effective and reliable functional food ingredients [43] [44].

This technical support guide provides researchers with practical methodologies, troubleshooting advice, and essential data to facilitate the successful implementation of cyclodextrin complexation in experimental protocols.

Core Experimental Protocols

Phase Solubility Studies