Applying the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to Advance Dietary Behavior Change in Clinical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on applying the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) to dietary behavior change interventions. It covers the foundational theory and history of the TDF, offers a step-by-step methodological guide for implementation, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies in real-world application, and reviews the framework's validation and comparative effectiveness against other models. By synthesizing current evidence and practical guidance, this article aims to bridge the gap between behavioral science and clinical practice, enhancing the design and evaluation of interventions from early-phase trials to clinical implementation.

Applying the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to Advance Dietary Behavior Change in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on applying the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) to dietary behavior change interventions. It covers the foundational theory and history of the TDF, offers a step-by-step methodological guide for implementation, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies in real-world application, and reviews the framework's validation and comparative effectiveness against other models. By synthesizing current evidence and practical guidance, this article aims to bridge the gap between behavioral science and clinical practice, enhancing the design and evaluation of interventions from early-phase trials to clinical implementation.

Understanding the TDF and COM-B Model: A Theoretical Foundation for Dietary Change

The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) is a comprehensive, evidence-based framework for characterizing and designing behavior change interventions. Developed through a synthesis of 19 existing frameworks of behavior change, it was created to overcome limitations of prior models by being comprehensive, coherent, and clearly linked to an overarching model of behavior [1] [2]. At the heart of the BCW lies the COM-B model, a behavioral system that posits three essential conditions for any behavior to occur: Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (forming the COM acronym) that interact to produce Behavior (the B in the model) [1] [3] [2]. This integrated system provides researchers and intervention designers with a systematic method for diagnosing behavioral barriers and developing targeted interventions.

The COM-B model represents a significant advancement in the field because it provides a "behavior system" at the hub of the BCW, encircled by intervention functions and policy categories [1]. This structure offers a coherent framework that links an understanding of the target behavior to specific intervention types and policy-level implementations. The model has been reliably applied across diverse domains including tobacco control, obesity prevention, chronic disease management, and dietary behavior change [1] [4] [5]. For researchers focusing on dietary behavior change, the BCW and COM-B provide a robust methodological approach for designing, implementing, and evaluating interventions with precision and theoretical grounding.

Theoretical Foundations and Model Architecture

The COM-B Behavioral System

The COM-B model provides a foundational framework for understanding the components necessary for behavior to occur. The model conceptualizes behavior as an interactive system within which capability, opportunity, and motivation influence each other in dynamic feedback loops [6]. The components are defined as follows:

Capability (C): An individual's psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned. Psychological capability includes having the necessary knowledge, mental skills, attention, memory, and decision-making processes. Physical capability encompasses bodily functions, strength, stamina, and dexterity required to perform the behavior [7] [3] [6].

Opportunity (O): All factors that lie outside the individual that make the behavior possible or prompt it. Physical opportunity includes environmental factors, resources, time, and triggers. Social opportunity encompasses the cultural milieu, social norms, and influences from others that define how others behave around the subject [7] [3] [6].

Motivation (M): All brain processes that energize and direct behavior, including both reflective and automatic mechanisms. Reflective motivation involves conscious decision-making, plans, evaluations, and beliefs. Automatic motivation includes emotional reactions, desires, impulses, and habituated responses that occur without conscious awareness [7] [3] [6].

These components interact within a dynamic system where changes in one component can directly affect behavior and indirectly influence other components through feedback loops [6]. For example, enhancing capability may increase motivation, while expanding opportunities may make individuals feel more capable.

The Behavior Change Wheel Structure

The Behavior Change Wheel builds upon the COM-B foundation with two additional layers:

Intervention Functions: The middle layer of the wheel consists of nine categories of interventions aimed at addressing deficits in one or more of the COM components [1] [8] [3]. These include education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modeling, and enablement.

Policy Categories: The outer layer identifies seven types of policies that can support the delivery of these interventions: communication/marketing, guidelines, fiscal measures, regulation, legislation, environmental/social planning, and service provision [1] [8].

The relationship between these layers forms a coherent structure where policies enable interventions that target specific COM-B components to bring about behavior change. This comprehensive architecture allows researchers and policymakers to systematically develop and evaluate behavior change initiatives.

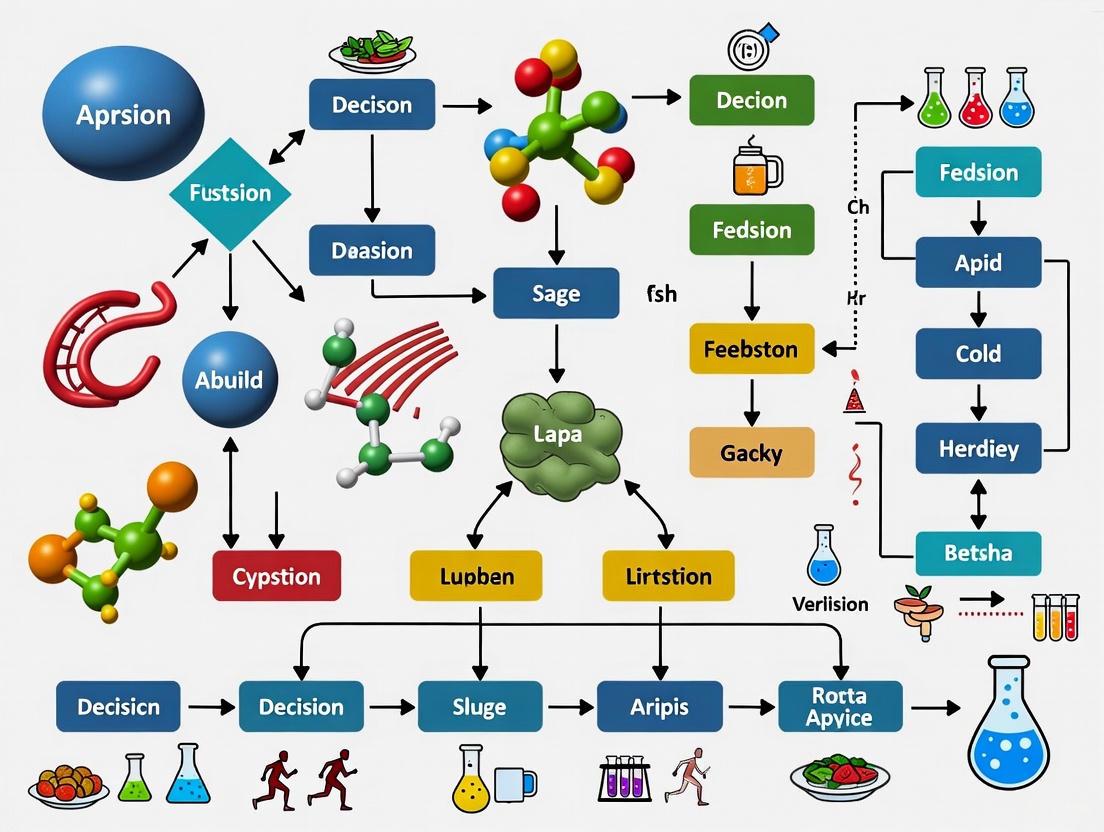

Figure 1: The Behavior Change Wheel Architecture showing the relationship between COM-B core components, intervention functions, and policy categories.

Methodological Framework for Intervention Design

The BCW Development Process

The development of the Behavior Change Wheel followed a rigorous methodological approach. Michie et al. conducted a systematic search of electronic databases and consulted with behavior change experts to identify existing frameworks of behavior change interventions [1] [2]. These frameworks were evaluated according to three criteria:

- Comprehensiveness: The framework should apply to every intervention that has been or could be developed

- Coherence: The categories should be all exemplars of the same type of entity and have similar specificity

- Linkage to a model of behavior: The framework should be linked to an overarching model of behavior [1]

The resulting BCW incorporated all identified intervention functions and policy categories from the 19 frameworks reviewed, organized around the COM-B behavior system [1] [2]. The reliability of this new framework was tested by applying it to characterize interventions within the English Department of Health's 2010 tobacco control strategy and the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence's guidance on reducing obesity, demonstrating its practical utility [1].

Step-by-Step Application Protocol

Implementing the BCW framework involves a structured process for designing behavior change interventions:

Table 1: BCW Intervention Design Protocol

| Step | Description | Key Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Define Outcome Behavior | Identify the target behavior in precise terms | - Define the problem in behavioral terms- Establish clear, measurable behavioral outcomes |

| 2. Select Target Behavior | Choose specific behaviors to change | - Apply criteria: likely impact, ease of implementation, spillover effects, measurement feasibility |

| 3. Specify Target Behavior | Detail behavioral parameters | - Specify what, where, when, how, with whom, and in what context the behavior occurs |

| 4. Diagnose Barriers | Identify what needs to change using COM-B | - Assess Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation barriers- Use COM-B model or Theoretical Domains Framework for granular analysis |

| 5. Identify Intervention Functions | Select appropriate intervention types | - Match interventions to COM-B barriers using BCW mapping- Apply APEASE criteria (Affordability, Practicality, Effectiveness, Acceptability, Safety, Equity) |

| 6. Identify Policy Categories | Determine enabling policies | - Select policy categories that support chosen intervention functions |

| 7. Identify Behavior Change Techniques | Specify intervention content | - Select specific Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) from taxonomy |

This protocol provides researchers with a systematic approach to intervention design, ensuring that all relevant factors are considered and that interventions are theoretically grounded and practically feasible [8] [9]. The process emphasizes beginning with a thorough understanding of the behavior in context before selecting intervention strategies, moving from behavioral diagnosis to implementation planning.

COM-B Component Analysis and Assessment Framework

Detailed COM-B Component Specification

For effective diagnosis of behavioral barriers, each COM-B component can be further analyzed through subcomponents and linked to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), which provides 14 detailed domains essential for behavior change [6] [9]:

Table 2: COM-B Component Specification with Associated Assessment Questions

| COM-B Component | Sub-components | Associated TDF Domains | Diagnostic Assessment Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Physical: skills, strength, stamina | Physical skills | Do individuals have the physical capacity, strength, or stamina to perform the behavior? |

| Psychological: knowledge, cognitive skills | Knowledge; Cognitive & interpersonal skills; Memory & decision processes; Behavioral regulation | Do individuals have the necessary knowledge, understanding, cognitive skills, and attention to perform the behavior? | |

| Opportunity | Physical: environment, resources, time | Environmental context & resources | Do individuals have the necessary resources, time, environmental triggers, and physical space to perform the behavior? |

| Social: norms, cultural expectations | Social influences | Is the behavior socially acceptable? Do social norms, peers, or authority figures influence the behavior? | |

| Motivation | Reflective: plans, evaluations, beliefs | Professional/social identity; Beliefs about capabilities; Optimism; Beliefs about consequences; Intentions; Goals | Do individuals have the conscious motivation, intentions, plans, and positive outcome expectations to perform the behavior? |

| Automatic: emotions, impulses, habits | Reinforcement; Emotion | Do individuals have automatic emotional responses, desires, impulses, or established habits related to the behavior? |

This detailed specification enables researchers to conduct granular analyses of behavioral determinants and identify precise targets for intervention. The linkage to TDF domains is particularly valuable for comprehensive behavioral diagnosis in complex research contexts [6].

Intervention Function Mapping

The BCW provides explicit mapping between COM-B components and intervention functions, guiding researchers in selecting appropriate strategies based on identified barriers:

Table 3: Intervention Functions Mapped to COM-B Components

| Intervention Function | Definition | Primary COM-B Targets | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Increasing knowledge or understanding | Psychological Capability, Reflective Motivation | Providing information on health consequences of dietary choices [10] |

| Persuasion | Using communication to induce feelings or stimulate action | Reflective & Automatic Motivation | Using imagery to motivate healthy eating [10] |

| Incentivization | Creating expectation of reward | Reflective & Automatic Motivation | Offering rewards for achieving dietary goals |

| Coercion | Creating expectation of punishment or cost | Reflective & Automatic Motivation | Implementing consequences for non-adherence |

| Training | Imparting skills | Physical & Psychological Capability, Automatic Motivation | Teaching food preparation skills [10] |

| Restriction | Using rules to reduce opportunity to engage in target behavior | Physical & Social Opportunity | Limiting access to unhealthy foods |

| Environmental Restructuring | Changing physical or social context | Physical & Social Opportunity, Automatic Motivation | Providing healthy foods in workplace [10] |

| Modelling | Providing an example for imitation | Social Opportunity, Reflective & Automatic Motivation | Demonstrating healthy eating by peers |

| Enablement | Increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity | All COM-B components | Providing resources to overcome barriers [10] |

This mapping enables precision in intervention design by directly linking identified behavioral barriers to evidence-based intervention strategies. Researchers can use this table to select intervention functions that specifically target the COM-B components identified as problematic in their behavioral analysis.

Experimental Applications in Dietary Behavior Change Research

Dietary Intervention for Gestational Diabetes Prevention

A 2024 study exemplifies the application of the BCW and COM-B in dietary behavior change research for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) [10]. The "Healthy Gut Diet" study was a complex behavior change intervention co-designed with women who had lived experience of GDM. The research followed the BCW process for designing interventions:

Methodology: The study involved six researchers and twelve women with lived experience of GDM participating in online workshops to co-design the intervention [10]. Content analysis of workshop transcripts and activities was undertaken, underpinned by the COM-B model and TDF. The target behaviors were: (1) eating more plant foods and (2) eating less ultra-processed/saturated fat containing foods.

Barriers Identification: Through COM-B analysis, researchers identified barriers and enablers across all six COM-B components and ten TDF domains [10]. This comprehensive diagnostic process revealed the multifaceted nature of dietary behavior in the context of pregnancy.

Intervention Design: Based on this analysis, the intervention functions selected were education, enablement, environmental restructuring, persuasion, and incentivization [10]. The researchers integrated forty behavior change techniques into five modes of delivery for the intervention.

Implementation: The feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the Healthy Gut Diet is being tested within a randomized controlled trial, demonstrating the rigorous experimental validation of BCW-informed interventions [10].

Nutritional Intervention for Female Recreational Footballers

Another recent study applied the COM-B model to enhance nutritional knowledge and intake in female recreational football players, demonstrating the framework's application in sports nutrition [4]:

Study Design: The study assessed players pre-intervention (n=54) and post-intervention (n=20) to evaluate changes in knowledge, dietary intakes, and risk of low energy availability following a COM-B behavior change intervention [4].

Intervention Development: The researchers followed a systematic process using COM-B guidelines to develop and implement the intervention with clear goals and implementation strategies [4]. The step-by-step intervention components were identified using COM-B principles and the BCW.

Target Behaviors: The study focused on increasing energy intake and carbohydrate intake in line with calculated targets and recommendations [4]. Specific target behaviors included increasing knowledge of players about health and performance benefits of adequate nutrition, providing regular email support over six months, and offering game-day nutritional support.

Results: While the results did not reach statistical significance, moderate effect sizes were observed for sports nutrition knowledge (d=.469), energy availability (d=.432), and carbohydrate intake (d=.419), suggesting practical relevance of the COM-B intervention [4]. This highlights the importance of considering both statistical and practical significance in behavior change research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools for BCW Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application in Dietary Behavior Research |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) | Extends COM-B with 14 detailed domains for granular barrier analysis | Provides detailed assessment of behavioral determinants in complex dietary interventions [10] |

| Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (BCT Taxonomy v1) | Standardized taxonomy of 93 hierarchically clustered BCTs | Enables precise specification of active intervention components for replication [10] [4] |

| Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) | 12-item checklist for comprehensive intervention description | Ensures complete reporting of dietary interventions for research replication [4] |

| APEASE Criteria | Evaluation framework: Affordability, Practicality, Effectiveness, Acceptability, Safety, Equity | Assesses intervention feasibility in real-world settings [4] |

| COM-B Self-Evaluation Questions | Structured diagnostic questions for barrier assessment | Systematically identifies capability, opportunity, and motivation barriers [6] |

These methodological tools provide researchers with standardized approaches for designing, implementing, and reporting behavior change interventions, enhancing scientific rigor and reproducibility.

Digital Implementation and Technological Integration

Recent advances have integrated the BCW and COM-B model into digital health platforms for scalable behavior change interventions. A 2025 study developed a multidomain behavioral change digital coaching system for chronic disease management in patients with type 2 diabetes using the BCW and COM-B as theoretical foundations [5].

Framework Development: The system employed a multiagent reasoning system that selected optimal digital coaching techniques based on individual assessments [5]. The BCW was used to design the program based on unique behavioral, population, and setting characteristics, linking evidence-based intervention functions to the COM-B behavioral model.

Implementation: The COM-B model served as the basis for user assessment, translating raw data into behavioral constructs [5]. In the experimental phase, the COM-B model was used to measure real-time changes in behavioral determinants, while the BCW guided the selection and prioritization of behavior change techniques.

Results: In a study of 9 patients with type 2 diabetes, the approach demonstrated notable results including reduced fasting glucose (-17.3 mg/dL), weight (-2.89 kg), and BMI (-1.05 kg/m²), with large effect sizes (Cohen d ≈ 1.05) and statistical significance (P=.01) [5]. This demonstrates the efficacy of BCW-informed digital implementations.

The technological implementation workflow can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Digital Implementation Workflow showing the integration of BCW/COM-B into digital health platforms for adaptive behavior change interventions.

The Behavior Change Wheel and COM-B model provide a robust, evidence-based framework for diagnosing behavioral barriers and designing targeted interventions in dietary behavior change research. Its systematic approach - moving from behavioral diagnosis through intervention selection to implementation and policy development - offers researchers a comprehensive methodology for developing theoretically grounded and practically feasible interventions.

The framework's strength lies in its integration of multiple behavioral theories into a coherent structure, its flexibility across diverse populations and settings, and its utility for both individual-level and population-level interventions. For researchers in dietary behavior change, the BCW and COM-B provide essential tools for addressing the complex interplay of biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors that influence eating behaviors.

As the field advances, integration of the BCW with digital health technologies and adaptive intervention platforms presents promising avenues for scalable, personalized behavior change interventions. The continued refinement and application of this framework will contribute significantly to developing more effective, sustainable dietary interventions that improve health outcomes across diverse populations.

The field of clinical nutrition faces a profound paradox: despite robust evidence demonstrating the critical role of nutrition in preventing and managing disease, the implementation of this evidence into routine practice remains inconsistent and fragmented. Research indicates that only approximately 20% of nutritional research findings ever translate into clinical practice, leaving patients without access to proven, effective nutritional care [11]. This evidence-practice gap represents a significant challenge to healthcare systems worldwide, potentially compromising patient outcomes, increasing healthcare costs, and diminishing the return on investment in nutrition research. The translation of evidence into practice is particularly complex in nutrition support, which requires agreement and coordination across entire multidisciplinary healthcare teams [11]. The challenge is further compounded by the individualized nature of nutritional requirements, which are deeply influenced by factors such as life stage, health status, and the presence of disease, all of which can affect the processes of consuming, digesting, absorbing, metabolizing, or excreting nutrients [12].

The conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients represents the core of evidence-based practice [12]. In nutrition, this has been formalized as evidence-based nutrition practice, which integrates the best available nutrition evidence with clinical experience to help patients prevent, resolve, or cope with problems related to their physical, mental, and social health [12]. However, the journey from research evidence to positive patient outcomes is neither straightforward nor automatic. It requires a systematic approach to implementation that acknowledges and addresses the complex interplay of biological, behavioral, environmental, and organizational factors that influence how evidence is adopted, implemented, and sustained in real-world settings. This whitepaper explores how theoretical frameworks, particularly the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and Behavior Change Wheel (BCW), provide essential methodological tools for addressing the evidence-practice gap in nutrition support and dietary interventions.

Theoretical Foundations: A Framework for Change

The science of implementing evidence into practice has evolved substantially since its early beginnings in the 1940s, culminating in the development of sophisticated theoretical frameworks specifically designed to promote evidence-based clinical change [11]. Among these, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) provide a comprehensive, systematic approach to mapping effective implementation strategies to address barriers and enablers to behavior change [11]. The TDF was developed through a process that merged multiple behavior theories, consensus processes, piloting, and validation to produce a final framework containing 14 key domains and 84 theoretical constructs that help researchers and clinicians identify potential barriers and enablers to behavior change [11].

The TDF is intrinsically linked to the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model, which forms the hub of the BCW [11]. This model posits that for any behavior to occur, an individual must have the capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (physical and social), and motivation (reflective and automatic) to perform the behavior. The TDF domains can be systematically mapped to the COM-B components to guide the selection of intervention types and strategies that are most likely to prompt behavior modification [11]. The relationship between these frameworks creates a powerful methodology for addressing implementation challenges in nutrition support.

Table 1: Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and COM-B Mapping

| TDF Domain | COM-B Component | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Psychological Capability | Understanding of nutrition guidelines and evidence base |

| Skills | Physical Capability | Proficiency in performing nutritional assessment and support |

| Social/Professional Role | Reflective Motivation | Perceived responsibility for nutritional care within professional identity |

| Beliefs about Capabilities | Reflective Motivation | Confidence in ability to provide effective nutrition support |

| Optimism | Reflective Motivation | Belief that nutritional interventions will achieve desired outcomes |

| Beliefs about Consequences | Reflective Motivation | Anticipation of outcomes of providing or not providing nutrition support |

| Reinforcement | Automatic Motivation | Previous positive or negative experiences with nutrition support |

| Intentions | Reflective Motivation | Conscious decision to engage in evidence-based nutrition practice |

| Goals | Reflective Motivation | Mental representations of aims or desired outcomes |

| Memory, Attention, Decision Processes | Psychological Capability | Ability to remember and prioritize nutrition support during care |

| Environmental Context/Resources | Physical Opportunity | Availability of resources, equipment, protocols, and time |

| Social Influences | Social Opportunity | Perceived social pressures from colleagues, patients, or organization |

| Emotion | Automatic Motivation | Emotional responses to providing nutrition support |

| Behavioral Regulation | Psychological Capability | Ability to plan, monitor, and adjust nutrition support behaviors |

The Implementation Process Using TDF and BCW

The process of using the TDF and BCW to address evidence-practice gaps involves three systematic steps [11]:

- Identify barriers and enablers using the TDF: The first step involves conducting qualitative interviews with key stakeholders to explore potential barriers and enablers across all 14 domains of the TDF. This ensures a comprehensive investigation without researcher bias or preconceived assumptions.

- Map domains to the COM-B: Once key domains are identified, they are mapped to the relevant components of the COM-B system to determine whether the intervention needs to address capability, opportunity, motivation, or a combination of these.

- Identify intervention categories and specific strategies: Based on the COM-B analysis, appropriate intervention types are selected from the BCW, followed by specific implementation strategies within each intervention type.

This systematic approach represents a significant advancement over traditional implementation efforts, which often employed generic, one-size-fits-all strategies without adequately addressing the specific barriers and enablers in a given context.

Quantifying the Evidence-Practice Gap in Nutrition

The evidence-practice gap in nutrition support is not merely a theoretical concern but a measurable phenomenon with significant implications for patient care and resource utilization. Research has demonstrated alarming discrepancies between evidence-based recommendations and actual clinical practice. For instance, one study found that only 37% of dietitian recommendations were actioned within the hospital setting, often due to non-evidence-based beliefs of physicians [11]. This implementation failure means many patients are denied optimal nutrition care, potentially leading to worse clinical outcomes, prolonged recovery times, and increased healthcare costs.

Case Example: Malnutrition Screening

Malnutrition screening within the inpatient setting provides a compelling example of an evidence-practice gap. International agreement supports the implementation of nutrition screening to identify those at risk of malnutrition to provide early interventions to prevent further decline and commence early nutrition support where needed [11]. However, numerous cross-sectional studies have shown that the practice of nutrition screening is not universal across healthcare settings in multiple countries [11]. Documented barriers include lack of resourcing, knowledge deficits, unclear ownership, and competing clinical priorities [11].

Case Example: Preoperative Prehabilitation

An emerging evidence-practice gap exists in the implementation of preoperative prehabilitation, which represents a multidisciplinary approach to physical, nutritional, and psychological optimization before surgery [11]. Evidence supports significant benefits including improved functional capacity, enhanced surgical recovery, reduced complication rates, and improved healthcare costs [11]. Nutrition is a fundamental component of prehabilitation, with strong positive clinical, patient-reported, and economic evidence supporting its implementation as standard care, particularly for high-risk groups such as malnourished and frail populations [11]. Despite this evidence base, the majority of hospitals across developed countries have not implemented prehabilitation programs [11]. Studies exploring impediments to implementation have identified multiple barriers, including limited resources, complex clinical pathways, declining medical condition of patients, and individual motivation challenges [11].

Table 2: Evidence-Practice Gaps in Nutrition Support

| Area of Practice | Evidence Base | Current Implementation Status | Key Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malnutrition Screening | Strong international consensus supporting routine screening [11] | Not universal across healthcare settings [11] | Lack of resourcing, knowledge, ownership, competing priorities [11] |

| Preoperative Prehabilitation | Strong evidence for clinical, patient-reported, and economic benefits [11] | Majority of hospitals not implemented [11] | Resource limitations, complex pathways, patient motivation [11] |

| Community-Based Stunting Interventions | Effective components identified: screening, education, supplementation, follow-up [13] | Limited implementation in resource-poor settings [13] | Socioeconomic factors, healthcare access, resource constraints [13] |

| Dietitian Recommendations | Evidence-based nutrition care plans [11] | Only 37% actioned [11] | Non-evidence-based beliefs of physicians [11] |

Experimental Methodology and Analytical Approaches

Qualitative Investigation of Implementation Barriers

The initial phase of addressing evidence-practice gaps involves rigorous qualitative investigation to identify barriers and enablers. This process should include [11]:

- Stakeholder Identification: Engage all key decision-makers involved in clinical, administrative, and financial aspects of the targeted nutrition practice. This typically includes a range of clinicians from junior to senior levels across medical, surgical, nursing, and allied health professions.

- Interview Protocol Development: Create semi-structured interview questions designed to explore all 14 domains of the TDF to ensure comprehensive coverage without researcher bias.

- Qualitative Rigor: Ensure methodological rigor through established criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability/consistency, and confirmability to minimize research bias.

- Thematic Analysis: Analyze interview transcripts to identify prominent themes related to specific TDF domains that function as either barriers or enablers.

This qualitative approach provides rich, contextual understanding of the specific challenges in implementing evidence-based nutrition practices within particular healthcare settings.

Quantitative Evaluation of Intervention Effectiveness

Quantitative methods are essential for evaluating both the implementation process and the effectiveness of nutrition interventions. Key quantitative data analysis methods include [14]:

- Descriptive Statistics: Summarize and describe the characteristics of datasets using measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode) and dispersion (range, variance, standard deviation) to provide a clear snapshot of implementation outcomes.

- Inferential Statistics: Use sample data to make generalizations about larger populations through techniques such as hypothesis testing, t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis, and correlation analysis.

- Cross-Tabulation: Analyze relationships between categorical variables, such as comparing implementation success across different clinical departments or professional groups.

- Gap Analysis: Compare actual performance against established benchmarks or goals to identify specific areas for improvement in the implementation process.

These quantitative approaches provide objective measures of implementation success and can help identify factors associated with better or worse adoption of evidence-based practices.

Diagram 1: TDF/BCW Implementation Framework for Nutrition Support

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Implementation Science in Nutrition

| Research Tool | Function | Application in Nutrition Implementation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) | Identifies barriers and enablers across 14 behavioral domains [11] | Systematic diagnosis of implementation challenges in nutrition support |

| Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) | Links identified barriers to evidence-based intervention strategies [11] | Selection of targeted implementation strategies for nutrition programs |

| COM-B System | Analyzes capability, opportunity, and motivation components of behavior [11] | Understanding fundamental drivers of healthcare professional behavior |

| Qualitative Interview Guides | Structured protocols for exploring stakeholder perspectives [11] | Eliciting rich, contextual data on nutrition implementation barriers |

| Cross-Tabulation Analysis | Examines relationships between categorical variables [14] | Analyzing associations between provider characteristics and implementation success |

| Gap Analysis Methodology | Compares actual performance against desired benchmarks [14] | Quantifying evidence-practice gaps in nutrition care |

| Implementation Outcome Measures | Assesses adoption, fidelity, penetration, sustainability [11] | Evaluating success of nutrition implementation strategies |

Case Study: Multi-faceted Interventions for Childhood Stunting

The application of theoretical frameworks to address evidence-practice gaps is particularly relevant in global nutrition challenges, such as childhood stunting in low- and middle-income countries. A comprehensive review of multi-faceted nutritional interventions for stunting reduction identified critical components of effective programs, yet also highlighted significant implementation challenges [13]. The review screened 1,636 studies and ultimately included 9 research studies from China, Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Mexico, Peru, and Vietnam for final analysis [13]. These studies evaluated clinical outcomes such as anthropometrics and dietary intake, with most including caregiver nutrition education (7 of 9 studies), but none implementing routine and frequent nutrition screening [13].

Based on this comprehensive review, effective stunting interventions should include four key components: (i) routine screening of every child for nutritional risk based on WHO and UNICEF guidance; (ii) caregiver-targeted nutrition education; (iii) supplementation with macro- and micronutrients as needed; and (iv) regular follow-up to monitor growth and nutritional status [13]. The limited number of studies meeting inclusion criteria highlights the need for expanded implementation research, particularly in under-resourced regions [13]. This case demonstrates how theoretical frameworks could help address the implementation challenges in delivering these comprehensive, multi-level strategies essential to addressing the long-term health risks of pediatric undernutrition.

Table 4: Effectiveness of Stunting Intervention Components in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

| Intervention Component | Frequency in Reviewed Studies (n=9) | Effectiveness Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Nutrition Education | 7 studies [13] | Foundational component for sustainable behavior change |

| Macronutrient and Micronutrient Supplementation | 4 studies [13] | Essential for addressing nutrient deficiencies |

| Frequent Follow-up (at least monthly) | 4 studies [13] | Critical for monitoring progress and adherence |

| Breastfeeding Assessment | 3 studies [13] | Important for infant and young child feeding |

| Routine Nutrition Screening | 0 studies [13] | Identified as missing but essential component |

The evidence-practice gap in nutrition support represents a significant challenge to optimizing patient outcomes and healthcare system efficiency. Theoretical frameworks, particularly the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behavior Change Wheel, provide essential methodological tools for systematically addressing this gap by identifying context-specific barriers and enablers, mapping these to behavioral determinants, and selecting evidence-based implementation strategies. The application of these frameworks moves the field beyond generic implementation approaches to targeted, theory-informed strategies that address the specific capability, opportunity, and motivation challenges in a given healthcare setting. As the case examples in malnutrition screening, preoperative prehabilitation, and childhood stunting demonstrate, the complexity of implementing evidence-based nutrition practice requires multifaceted approaches that acknowledge the individual, organizational, and system-level factors influencing healthcare professional behavior. Future research should prioritize the application of these theoretical frameworks across diverse nutrition support contexts, with rigorous evaluation of their impact on both implementation success and patient outcomes. Only through such systematic, theory-informed approaches can the field of nutrition support fully bridge the evidence-practice gap and realize the potential of nutritional interventions to improve health outcomes.

In dietary behavior change research, precisely defining the problem represents the critical foundation upon which all subsequent intervention success depends. The identification of key dietary behaviors for change constitutes a complex process that extends beyond merely recognizing poor nutritional habits. Within the context of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), this process requires a systematic investigation of the multifaceted determinants influencing dietary behaviors across cognitive, affective, social, and environmental domains [15]. The TDF provides a comprehensive, theory-informed approach to identify determinants of behavior, synthesizing 128 theoretical constructs from 33 theories of behaviour and behaviour change into an accessible framework [15]. This guide presents a rigorous methodology for researchers seeking to define dietary behavior problems with the precision necessary to develop effective, theory-driven interventions, thereby bridging the gap between nutritional epidemiology and implementation science.

Theoretical Foundation: The Theoretical Domains Framework in Dietary Research

The Theoretical Domains Framework offers a systematic structure for investigating barriers and enablers to implementing evidence-based practices, including dietary behaviors. The TDF was developed through a consensus process involving behavioural scientists and implementation researchers who identified, evaluated, and synthesized theoretical constructs most relevant to implementation questions [15]. The framework's evolution has resulted in a validated version comprising 14 domains encompassing 84 theoretical constructs, providing comprehensive coverage of potential influences on behavior [15].

In dietary research, the TDF enables investigators to move beyond simplistic explanations for dietary non-adherence and instead conduct a multidimensional analysis of the problem space. When applied to dietary behaviors, the framework facilitates exploration of capabilities (physical and psychological), opportunities (social and physical), and motivations (reflective and automatic) that constitute the COM-B system—a central component of the Behavior Change Wheel [11] [16]. This theoretical grounding ensures that problem identification is not based on assumptions but rather on a structured investigation of the theoretical constructs that may influence the target dietary behavior.

Table 1: Theoretical Domains Framework (v2) Domains and Applications to Dietary Behavior

| Domain Number | Domain Name | Application to Dietary Behavior Research |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowledge | Understanding nutritional principles, dietary guidelines, food composition |

| 2 | Physical skills | Food preparation techniques, portion control measurement |

| 3 | Social/professional role and identity | Perception of personal responsibility for health, family food provider roles |

| 4 | Beliefs about capabilities | Confidence in ability to change dietary habits (self-efficacy) |

| 5 | Optimism | Belief that dietary changes will lead to desired health outcomes |

| 6 | Beliefs about consequences | Beliefs about benefits and costs of dietary change |

| 7 | Reinforcement | Internal and external rewards for maintaining dietary changes |

| 8 | Intentions | Conscious decision to engage in specific dietary behaviors |

| 9 | Goals | Setting specific, measurable dietary targets |

| 10 | Memory, attention and decision processes | Cognitive processes in food choice and consumption |

| 11 | Environmental context and resources | Food availability, accessibility, affordability |

| 12 | Social influences | Family, peer, cultural influences on eating behaviors |

| 13 | Emotion | Stress eating, emotional connections to certain foods |

| 14 | Behavioral regulation | Self-monitoring, planning, habit formation |

Methodological Approach: A Systematic Process for Problem Identification

Defining the Target Behavior with Precision

The initial step in identifying key dietary behaviors requires precise specification of the target behavior. Vague characterizations such as "eat healthier" or "improve diet" lack the specificity necessary for effective intervention design. Instead, researchers should define behaviors using explicit criteria that specify the action, context, target, time, and actors involved [15]. For example, rather than targeting "increased fruit and vegetable consumption," a precisely defined behavior would be "parents serving two different vegetables with weekday evening meals for family members." This precision enables accurate measurement and facilitates identification of specific barriers and enablers.

The process of specifying target behaviors should incorporate multiple stakeholder perspectives, including patients, food service providers, healthcare professionals, and policy makers where relevant. This collaborative approach ensures the identified behaviors have clinical relevance, practical significance, and align with the lived experiences of the target population [16]. In transdisciplinary research, such as the SWITCH project focusing on adolescent dietary behaviors, expert panels from both academia and practice provide critical insights into which determinants are most relevant, urgent, and changeable [17].

Dietary Assessment Methodologies for Behavior Identification

Accurate identification of problematic dietary behaviors requires robust assessment methodologies that capture both the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of dietary intake. The selection of assessment tools must align with the research question, study design, sample characteristics, and available resources [18].

Table 2: Dietary Assessment Methods for Identifying Target Behaviors

| Method | Primary Use | Strengths | Limitations | Alignment with TDF Domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Captures recent detailed intake | High specificity for recent foods consumed; does not require literacy | Relies on memory; subject to day-to-day variation; trained interviewers often needed | Memory, attention and decision processes |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire | Assesses habitual intake over time | Cost-effective for large samples; captures patterns rather than daily variation | Limited food list; reliance on generic memory; less precise for absolute intakes | Knowledge, Goals, Behavioral regulation |

| Food Records | Detailed recording of current intake | Does not rely on memory; provides detailed quantitative data | Reactivity (participants may change behavior); high participant burden; requires literacy | Behavioral regulation, Environmental context and resources |

| Screening Tools | Rapid assessment of specific dietary components | Low participant burden; targeted to specific behaviors | Limited scope; must be validated for specific populations | Knowledge, Beliefs about consequences, Intentions |

Emerging technologies including digital photography of meals, mobile applications for real-time tracking, and automated dietary assessment tools are expanding methodological options for capturing dietary behaviors with reduced participant burden and enhanced objectivity [18]. Regardless of the methodology selected, researchers must acknowledge and account for measurement error inherent in all self-reported dietary assessment methods [18].

Applying the TDF to Identify Behavioral Determinants

Once target behaviors are specified, the TDF provides a structured approach to identify determinants through qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods. Semi-structured interviews based on the TDF domains represent the most comprehensive approach for exploring the full range of potential influences on dietary behaviors [15].

Interview guides should include open-ended questions designed to elicit information about each of the 14 TDF domains without introducing researcher bias. For example, to explore the "Environmental Context and Resources" domain regarding vegetable consumption, researchers might ask: "Tell me about the situations or environments that make it easier or more difficult for you to eat vegetables?" [15]. Similarly, to investigate "Social Influences," appropriate questions might include: "How do people who are important to you affect your food choices?" [17].

Focus groups can provide valuable insights into shared experiences and social norms, particularly for dietary behaviors that have strong cultural or familial components [17]. Questionnaire-based approaches using validated instruments for specific TDF domains, such as self-efficacy scales or knowledge assessments, can complement qualitative methods and enable larger sample sizes [19].

The research team should include members with expertise in behavioral theory and qualitative methods to ensure appropriate application of the TDF throughout data collection and analysis. Transcription and coding of qualitative data using the TDF as a framework allows for systematic identification of salient domains influencing the target dietary behavior [16] [15].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analytical Framework for TDF-Based Qualitative Data

Analysis of TDF-based qualitative data involves a multi-stage process designed to identify key domains influencing the target dietary behavior. The process typically begins with familiarization with the entire dataset, followed by coding of specific belief statements to relevant TDF domains [15]. Researchers should establish coding protocols that specify how to handle data that fits multiple domains or does not clearly align with any domain.

Thematic analysis within each domain identifies specific beliefs that may operate as barriers or enablers. For example, when examining barriers to healthy eating among adolescents, analysis might reveal that within the "Social Influences" domain, peer pressure emerges as a significant barrier, while within "Environmental Context and Resources," limited access to affordable healthy options near schools is identified as a structural barrier [17]. Similarly, research in hospital foodservices identified "Environmental Context and Resources" as a dominant domain, with subthemes including lack of labor, time constraints, and inadequate equipment [16].

Determining the importance of each domain requires consideration of both the frequency of beliefs expressed and their perceived influence on the target behavior. Some beliefs may be mentioned infrequently yet represent critical barriers for specific subgroups, highlighting the importance of contextual factors in dietary behaviors [15].

Identifying Key Dietary Behaviors for Intervention

Synthesis of analytical findings leads to the identification of key dietary behaviors meriting intervention focus. Prioritization should consider the modifiability of the behavior, its likely impact on health outcomes, and the practical feasibility of addressing it within resource constraints [17]. The TDF-based analysis enables researchers to move beyond superficial characterizations of dietary problems to understand the underlying mechanisms maintaining suboptimal behaviors.

Research demonstrates that dietary interventions based on thorough behavioral analysis yield more significant improvements in clinical outcomes. For instance, in type 2 diabetes management, specific behavior change techniques including 'instruction on how to perform a behavior,' 'behavioral practice/rehearsal,' 'demonstration of the behavior,' and 'action planning' were associated with clinically significant reductions in HbA1c (>0.3%) [20]. These techniques directly address identified barriers in domains such as Knowledge, Skills, and Beliefs about capabilities.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Behavior Assessment

| Tool Category | Specific Instrument | Primary Application | Key Features | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Platforms | Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Recall (ASA24) | 24-hour dietary recall data collection | Self-administered; reduces interviewer burden; free for researchers | Developed by National Cancer Institute [18] |

| Behavioral Assessment Frameworks | Theoretical Domains Framework Interview Guide | Identifying barriers and enablers to dietary change | Semi-structured format covering 14 theoretical domains | Validated in multiple implementation studies [15] |

| Stage of Change Algorithm | Stages of Change for Healthy Eating | Assessing readiness to change dietary behaviors | Classifies participants into pre-contemplation, contemplation, decision, action, maintenance | Validated with adolescent and young adult populations [19] |

| Self-Efficacy Scales | Self-Efficacy for Healthy Eating Scale | Measuring confidence in adopting healthy eating practices | 19-item Likert scale assessing intention to adopt healthy behaviors | Validated for Brazilian adolescents [19] |

| Food Environment Assessment | Nutrition Environment Measures Survey (NEMS) | Assessing food availability, quality, and price in various settings | Adaptable for schools, workplaces, healthcare facilities | Widely used in food environment research [17] |

The systematic identification of key dietary behaviors for change represents a foundational step in developing effective nutritional interventions. By applying the Theoretical Domains Framework through rigorous methodological approaches, researchers can move beyond superficial characterizations of dietary problems to understand the complex interplay of cognitive, affective, social, and environmental factors influencing food-related behaviors. This process enables precisely targeted interventions that address the most salient and modifiable determinants, ultimately enhancing the efficacy and impact of efforts to improve dietary behaviors and health outcomes across diverse populations. The integration of robust dietary assessment methods with theoretically grounded behavioral analysis provides a powerful approach for advancing nutritional science and translating evidence into practice.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying the TDF and BCW in Dietary Intervention Design

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) is an integrative framework developed to simplify and synthesize theories of behavior change, making them more accessible for implementation research [21]. It consolidates 33 theories and 128 theoretical constructs into a coherent structure for analyzing behavioral determinants [21]. Within dietary behavior change research, the TDF provides a systematic methodology for identifying barriers and enablers that influence the adoption of evidence-based nutrition practices, from clinical settings to public health interventions [11] [22].

The TDF is particularly valuable for addressing the evidence-practice gaps commonly found in nutrition support. For instance, studies demonstrate that only about 37% of dietitian recommendations are actioned in hospital settings, often due to non-evidence-based beliefs of physicians [11]. The framework offers a structured approach to diagnose implementation problems and design theoretically-grounded interventions [21].

The TDF Domain Structure and Definitions

The validated TDF comprises 14 domains, each representing a grouping of related theoretical constructs that influence behavior [21]. These domains provide comprehensive coverage of individual, social, and environmental factors affecting behavior change implementation.

Table 1: The 14 Domains of the Theoretical Domains Framework with Definitions

| Domain Number | Domain Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowledge | An awareness of the existence of something, including procedural knowledge of how to perform behaviors [23] |

| 2 | Skills | Proficiency or dexterity acquired through practice and experience [23] |

| 3 | Social/Professional Role and Identity | A coherent set of behaviors and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting [23] |

| 4 | Beliefs about Capabilities | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about an ability, talent, or facility that a person can put to constructive use [23] |

| 5 | Optimism | The confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained [23] |

| 6 | Beliefs about Consequences | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about outcomes of a behavior in a given situation [23] |

| 7 | Reinforcement | Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus [23] |

| 8 | Intentions | A conscious decision to perform a behavior or a resolve to act in a certain way [23] |

| 9 | Goals | Mental representations of outcomes or end states that an individual wants to achieve [23] |

| 10 | Memory, Attention and Decision Processes | The ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment, and choose between two or more alternatives [23] |

| 11 | Environmental Context and Resources | Any circumstance of a person's situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence, and adaptive behavior [23] |

| 12 | Social Influences | Those interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviors [23] |

| 13 | Emotion | A complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements, by which an individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event [23] |

| 14 | Behavioral Regulation | Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions [23] |

Methodological Protocol for TDF-Based Qualitative Research

Study Design and Stakeholder Identification

The first step involves identifying all key stakeholders relevant to the dietary behavior being studied. In clinical nutrition research, this typically includes:

- Clinical stakeholders: Junior to senior-level medical and surgical staff, nursing professionals, dietitians, and allied health professionals [11]

- Administrative and financial decision-makers: Individuals responsible for resource allocation and system-level implementation [11]

- End-users: Patients, families, or community members whose behaviors are targeted for change [22]

Qualitative interviews with these stakeholders represent the primary methodology for exploring barriers and enablers [11]. Interviews should continue until theoretical saturation is reached, typically with 25-30 participants, as demonstrated in a recent study on family vegetable feeding practices that conducted 25 semi-structured interviews [22].

Interview Guide Development

Creating qualitative questions designed to explore all 14 domains of the TDF ensures comprehensive coverage without researcher bias or preconceived assumptions [11]. The interview guide should include:

- Grand tour questions: Broad opening questions about participants' experiences with the target behavior

- Domain-specific probes: Questions tailored to each TDF domain to elicit relevant barriers and enablers

- Scenario-based questions: Concrete situations to help participants articulate influences on their behavior

Example questions for dietary behavior change research might include:

- Knowledge: "What training have you received about nutrition screening protocols?"

- Environmental Context and Resources: "What resources are available to you for providing nutrition support?"

- Beliefs about Consequences: "What do you believe would happen if you consistently implemented these nutrition practices?"

Ensuring Methodological Rigor

Qualitative interviews must ensure rigor through four key criteria [11]:

Table 2: Criteria for Ensuring Qualitative Research Rigor in TDF Studies

| Criterion | Definition | Application in TDF Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility | Confidence in the truth of the data and interpretations | Use of multiple coders, member checking, and triangulation of data sources |

| Transferability | Extent to which findings can be applied to other contexts | Thick description of context, participants, and implementation setting |

| Dependability/Consistency | Whether findings would be consistent if replicated with similar participants | Audit trails, detailed documentation of analytical decisions |

| Neutrality | Freedom from bias in the research process and findings | Reflexivity, bracketing of preconceptions, transparent reporting |

Analytical Framework for TDF Data

Data Coding and Analysis Process

Analysis of qualitative interviews follows a structured framework approach [23]:

- Familiarization: Reading and re-reading transcripts to become immersed in the data

- Coding against TDF domains: Identifying segments of text relevant to each TDF domain

- Content analysis within domains: Further analyzing content within each domain to identify specific barriers and enablers

- Synthesis: Generating themes that represent the key influences on behavior

This process was successfully applied in a study on self-care for minor ailments, where framework synthesis using the TDF enabled systematic analysis of both interview and survey data across multiple reviews [23].

Mapping to the COM-B Model

Once key domains are identified using the TDF, they can be mapped to the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model, which forms the hub of the Behavior Change Wheel [11] [23]. This mapping helps determine which component of the behavior system requires intervention:

- Capability: The individual's psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned

- Opportunity: All the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behavior possible or prompt it

- Motivation: All the brain processes that energize and direct behavior

TDF to COM-B Mapping Framework

Research Toolkit for TDF-Based Dietary Behavior Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for TDF Qualitative Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function in TDF Research |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Framework | 14-domain TDF [21] | Provides comprehensive coding framework for identifying behavioral determinants |

| Behavior Model | COM-B System [23] | Serves as hub for mapping TDF findings to intervention design |

| Qualitative Methodology | Semi-structured interviews [11] | Primary data collection method for exploring barriers and enablers |

| Analysis Method | Framework synthesis [23] | Systematic approach for coding data against TDF domains |

| Quality Assessment | Rigor criteria (credibility, transferability, dependability, neutrality) [11] | Ensures trustworthiness of qualitative findings |

| Triangulation Method | Multiple stakeholder perspectives [11] [23] | Enhances comprehensiveness of identified barriers and enablers |

| Mirodenafil dihydrochloride | Mirodenafil dihydrochloride, CAS:862189-96-6, MF:C26H39Cl2N5O5S, MW:604.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ML327 | ML327, MF:C19H18N4O4, MW:366.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application in Dietary Behavior Change Research

The TDF has been successfully applied in various nutrition-related behavior change contexts. For example, in a study on family vegetable feeding practices, researchers used the TDF and COM-B model to explore barriers and enablers to repeatedly reoffering vegetables, role-modeling consumption, and offering non-food rewards [22]. The analysis identified eleven core themes mapped to 11 of the 14 TDF domains, including 'Child factors,' 'Eating beliefs,' 'Effectiveness beliefs,' and 'Practical issues' [22].

Another application addressed the evidence-practice gap in malnutrition screening within inpatient settings, where TDF-based interviews identified barriers such as lack of resourcing, knowledge gaps, competing priorities, and ownership issues [11]. Similarly, in implementing preoperative prehabilitation programs, TDF analysis revealed barriers including resource limitations, complex clinical pathways, declining patient medical conditions, and individual motivation challenges [11].

The systematic identification of barriers and enablers using TDF-based qualitative methods represents a critical first step in developing effective, theory-informed interventions for dietary behavior change. This approach ensures that implementation strategies address the actual determinants of behavior rather than presumed barriers, increasing the likelihood of successful adoption and maintenance of evidence-based nutrition practices.

The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) provide a systematic approach for understanding and implementing behaviour change in healthcare and research settings. The COM-B model posits that for any behaviour (B) to occur, an individual must have the physical and psychological capability (C), the physical and social opportunity (O), and the reflective and automatic motivation (M) to perform the behaviour [7]. These components interact within a system where behaviour also influences these components, creating a feedback loop [24].

The TDF offers a more detailed theoretical lens through which to view behavioural determinants. Originally developed through a synthesis of 33 theories of behaviour and behaviour change, it comprises 14 domains that capture the spectrum of cognitive, affective, social, and environmental influences on behaviour [15]. The TDF was specifically designed to help identify barriers and enablers to implementing evidence-based practices [11] [15].

When used together, these frameworks provide a comprehensive methodology: the TDF allows researchers to conduct a detailed diagnostic assessment of implementation problems, and the COM-B model provides a structure for categorizing these determinants to inform intervention design [25] [11]. This mapping is a crucial step within the broader Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework for developing theory-informed interventions [11] [26].

Theoretical Foundations of Domain Mapping

The Structural Relationship Between TDF and COM-B

The TDF and COM-B model share a foundational relationship, with the 14 domains of the TDF being systematically mappable to the six components of the COM-B model. This mapping is not arbitrary but reflects the theoretical coherence between the constructs [15]. The COM-B model serves as the central hub of the Behaviour Change Wheel, with the TDF providing the granular theoretical constructs that elaborate each component [27] [28].

This integrated approach allows researchers to progress from a broad understanding of behavioural determinants to specific intervention design. The mapping process creates a theoretically-grounded pathway from identifying barriers and enablers (via TDF) to categorizing them according to the COM-B system, which then directly links to intervention types through the BCW [11]. The relationship is structured such that TDF domains aligned with Capability address the individual's capacity to engage in the behaviour, those aligned with Opportunity address factors external to the individual that make the behaviour possible, and those aligned with Motivation address brain processes that energize and direct behaviour [15] [24].

The Mapping Methodology

The mapping between TDF domains and COM-B components follows a systematic process established through consensus methods and validation exercises [15]. Each of the 14 TDF domains corresponds to one of the six COM-B components based on theoretical alignment and empirical evidence [15] [24]. For instance, TDF domains related to knowledge and cognitive processes map to Psychological Capability, while domains related to environmental factors map to Physical Opportunity.

This mapping has been validated across multiple healthcare contexts and behaviours, including implementation of evidence-based nutrition practices [11] [26], dietary behaviour change [27] [29], and healthcare professional behaviour [15] [28]. The methodology ensures comprehensive coverage of potential behavioural determinants while maintaining theoretical integrity.

Table 1: Comprehensive Mapping of TDF Domains to COM-B Components

| COM-B Component | COM-B Subcomponent | TDF Domain | Domain Description and Constructs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | Psychological Capability | Knowledge | Awareness of existence, knowledge about condition, scientific rationale, procedural knowledge |

| Cognitive and Interpersonal Skills | Memory, attention, decision processes, cognitive overload, behavioural regulation | ||

| Behavioural Regulation | Self-monitoring, breaking habit, action planning | ||

| Physical Capability | Skills | Physical skills, competence, ability, practical knowledge, assessment of complexity | |

| Opportunity | Physical Opportunity | Environmental Context and Resources | Barriers and facilitators, environmental stressors, resources, time, triggers |

| Social Opportunity | Social Influences | Social norms, group conformity, social support, power, conflict | |

| Motivation | Reflective Motivation | Social/Professional Role and Identity | Professional identity, professional boundaries, group identity |

| Beliefs about Capabilities | Self-confidence, self-efficacy, perceived competence, empowerment | ||

| Optimism | Optimism, pessimism, unrealistic optimism, identity | ||

| Beliefs about Consequences | Outcome expectancies, characteristics of outcome expectancies, anticipated regret | ||

| Intentions | Stability of intentions, certainty, readiness to change | ||

| Goals | Goal targeting, goal priority, goal conflict | ||

| Automatic Motivation | Emotion | Fear, anxiety, affect, stress, positive/negative consequences | |

| Reinforcement | Rewards, incentives, punishment, contingencies |

Experimental Protocols for Mapping TDF to COM-B

Qualitative Assessment Methodology

The most common approach for mapping TDF domains to COM-B components involves qualitative methods, particularly semi-structured interviews and focus groups [15]. The protocol begins with developing an interview schedule based on the 14 TDF domains, with questions designed to elicit barriers and enablers for each domain [15] [27]. For example, in a study on implementing the MIND diet, researchers developed questions targeting each TDF domain to understand barriers and facilitators to dietary adoption [27].

The recommended sample size for such qualitative investigations typically ranges from 25-50 participants, depending on the complexity of the behaviour and diversity of the population [15] [27]. Data collection continues until thematic saturation is achieved. Transcripts are then coded using a two-stage process: first, data are categorized into the 14 TDF domains; second, these domains are mapped to the relevant COM-B components based on the established theoretical relationships [15] [28]. This process requires multiple independent coders and consensus meetings to ensure reliability.

Quantitative Assessment Methodology

Quantitative approaches to mapping TDF to COM-B employ cross-sectional survey designs with validated measures for each construct [24] [29]. For instance, a study examining young adults' eating and physical activity behaviours sourced pre-validated measures appropriate for capturing the latency of COM-B constructs, with surveys administered to 455-582 participants [24].

The analytical approach typically uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypothesized relationships between COM-B components and their influence on behaviour [24]. Model fit indices (CFI, TLI, RMSEA) are used to assess how well the mapping aligns with observed data. This method allows for testing both direct and mediated pathways, such as how capability and opportunity influence behaviour through motivation as a mediator [24].

Mixed-Methods Approaches

Mixed-methods designs combine qualitative and quantitative approaches to provide a more comprehensive mapping [27] [28]. For example, in a study with midwifery leaders, researchers conducted focus groups and interviews (qualitative) alongside survey measures (quantitative) to map barriers and facilitators to COM-B components [28]. The qualitative data provided rich contextual understanding, while the quantitative data enabled assessment of the relative importance of different domains.

This approach is particularly valuable for complex implementation challenges where both the depth of understanding (qualitative) and generalizability (quantitative) are important. The integration of findings typically occurs during the interpretation phase, where qualitative themes and quantitative relationships are synthesized into a coherent mapping [27] [28].

Application in Dietary Behaviour Change Research

Case Study: MIND Diet Adoption

Research on adoption of the MIND diet provides a compelling case study for TDF to COM-B mapping in dietary behaviour change. A qualitative study with 40-55-year-olds in Northern Ireland used TDF-based interviews to identify barriers and facilitators, which were then mapped to COM-B components [27]. The mapping revealed that time constraints, work environment, taste preferences, and convenience were primary barriers mapping to Physical Opportunity, while improved health, memory benefits, planning skills, and food access were key facilitators mapping to both Physical Opportunity and Reflective Motivation [27].

A cross-sectional survey with female caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease further demonstrated this application, showing how budget constraints (Physical Opportunity), cooking skills (Physical Capability), and social support (Social Opportunity) influenced MIND diet adoption through motivational pathways [30]. These findings highlight how TDF to COM-B mapping can identify specific, targetable factors for interventions.

Streamlined Approaches for Dietary Research

Recent research has explored streamlined versions of the COM-B model for dietary behaviour contexts to reduce measurement burden while maintaining predictive validity [29]. One study with Australian young adults tested a simplified model focusing on seven core constructs rather than the full complement of TDF domains, finding that automatic motivation, physical environment, and physical capability were particularly critical for healthy eating behaviours [29].

This streamlined approach maintains the theoretical integrity of the TDF to COM-B mapping while increasing practical utility for researchers and practitioners. The simplification involves selecting key TDF domains most relevant to dietary behaviours based on prior evidence, then mapping these to the corresponding COM-B components [29].

Table 2: Dietary Behaviour Change Studies Using TDF to COM-B Mapping

| Study Population | Research Design | Key TDF Domains Identified | Mapped COM-B Components | Primary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle-aged adults (40-55 years) adopting MIND diet [27] | Qualitative (focus groups & interviews) | Environmental Context & Resources; Goals; Beliefs about Consequences | Physical Opportunity; Reflective Motivation | Barriers: time, work environment, taste preference. Facilitators: improved health, planning/organization |

| Female caregivers of people with ADRD [30] | Cross-sectional survey (n=299) | Environmental Context & Resources; Skills; Social Influences | Physical Opportunity; Physical Capability; Social Opportunity | Main barriers: budget, time, transportation. Main facilitators: budget planning, cooking skills, family support |

| Young adults' eating behaviours [24] | Cross-sectional survey (n=455) | Goals; Reinforcement; Environmental Context & Resources | Reflective Motivation; Automatic Motivation; Physical Opportunity | COM-B model explained 23% of variance in eating behaviour |

| Young adults' physical activity [24] | Cross-sectional survey (n=582) | Goals; Reinforcement; Environmental Context & Resources | Reflective Motivation; Automatic Motivation; Physical Opportunity | COM-B model explained 31% of variance in physical activity |

| Australian young adults' healthy eating [29] | Cross-sectional survey (n=347) | Environmental Context & Resources; Reinforcement; Skills | Physical Opportunity; Automatic Motivation; Physical Capability | Streamlined COM-B highlighted automatic motivation, physical environment, physical capability |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TDF to COM-B Mapping Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| TDF-Based Interview Schedule | Elicit barriers and enablers across all 14 theoretical domains | Semi-structured guide with questions for each TDF domain [15] |

| COM-B Coding Framework | Systematically map TDF-derived data to COM-B components | Codebook with decision rules for assigning TDF domains to COM-B [28] |

| Thematic Analysis Guide | Analyze qualitative data using a theory-informed approach | Iterative coding process from transcripts to TDF domains to COM-B [27] |

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Test hypothesized relationships in COM-B model quantitatively | Analysis of direct and mediated pathways between COM-B components [24] |

| Behaviour Change Wheel Framework | Design interventions based on COM-B diagnosis | Linking identified COM-B components to intervention functions [11] |

| ML349 | ML349, MF:C23H22N2O4S2, MW:454.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ML390 | ML390 DHODH Inhibitor|Research Use Only | ML390 is a potent human DHODH inhibitor for leukemia and antiviral research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

Figure 1: Theoretical Mapping of TDF Domains to COM-B System

Selecting appropriate intervention functions and policy categories constitutes a critical step in the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) framework, serving as the crucial bridge between behavioral analysis and actionable intervention strategies. This step transforms the theoretical understanding of barriers and enablers, identified through the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and categorized via the COM-B model, into practical methods for changing behavior [11]. For researchers in dietary behavior change, this systematic selection process ensures that interventions target the specific mechanisms influencing dietary practices, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful implementation and lasting effect [31]. The BCW offers a comprehensive synthesis of 19 behavior change frameworks, providing a coherent structure for designing interventions that are theoretically grounded, evidence-based, and contextually appropriate [32].