Beyond Self-Report: A Comprehensive Comparison of Traditional vs. Objective Dietary Assessment Methods for Clinical Research

Accurate dietary assessment is critical for understanding diet-disease relationships, informing public health policy, and monitoring intervention efficacy in clinical trials.

Beyond Self-Report: A Comprehensive Comparison of Traditional vs. Objective Dietary Assessment Methods for Clinical Research

Abstract

Accurate dietary assessment is critical for understanding diet-disease relationships, informing public health policy, and monitoring intervention efficacy in clinical trials. However, traditional self-report methods like food frequency questionnaires, 24-hour recalls, and food diaries are notoriously prone to systematic errors, including recall bias, social desirability bias, and significant underreporting, particularly for energy intake. This article provides a systematic review of both established and emerging dietary assessment methodologies, contrasting the limitations of traditional tools with the promise of novel objective technologies. We explore foundational principles, methodological applications, strategies for troubleshooting systematic errors, and validation techniques using recovery biomarkers. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence to guide the selection and optimization of dietary assessment methods, enhancing data quality and reliability in biomedical research.

The Dietary Assessment Landscape: Core Principles and the Critical Shift from Subjective to Objective Measures

Dietary assessment provides the fundamental data necessary to understand the complex relationships between diet and health. In both research and clinical settings, accurately capturing what individuals consume is crucial for investigating diet-disease associations, developing nutritional guidelines, and creating personalized intervention strategies [1] [2]. The field is currently undergoing a significant transformation, moving from traditional subjective recall methods toward more objective, technology-enhanced approaches that minimize inherent biases and participant burden [3] [4]. This evolution is particularly relevant for researchers and drug development professionals who require precise dietary metrics to evaluate nutritional interventions, understand nutrient-biomarker relationships, and assess lifestyle factors in clinical trials. This article compares the performance of traditional versus emerging dietary assessment methodologies, examining their experimental validation, relative accuracy, and appropriate applications in scientific research.

Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods: Foundations and Limitations

Traditional dietary assessment tools have formed the backbone of nutritional epidemiology for decades, though they come with well-documented methodological challenges.

- Methodologies and Applications: The most established methods include 24-hour dietary recalls (multiple-pass interviewer-administered or automated self-administered versions), food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), and food records (both estimated and weighed) [5] [2]. These tools are particularly valuable for capturing habitual intake (FFQs) or detailed recent consumption (24-hour recalls and food records) in large population studies.

- Inherent Limitations and Biases: These methods share significant limitations, including recall bias, portion size estimation errors, social desirability bias, and substantial participant burden [3] [4] [2]. Validation studies using doubly labeled water have revealed energy intake reporting errors ranging from 20% to 50%, with considerable inter-individual variability [4]. These measurement errors can substantially obscure true diet-disease relationships in research settings.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Dietary Assessment Approaches

| Method Category | Specific Tools | Primary Use Cases | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Self-Report | 24-hour Recalls (ASA24) [2] | Population surveillance, intake quantification | Detailed nutrient data, multiple days capture memory dependence | Memory dependence, participant burden [3] |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) [2] | Habitual intake ranking, epidemiology | Captures long-term patterns, low participant burden | Portion size inaccuracy, memory bias [2] | |

| Food Records [2] | Clinical metabolic studies, validation | Prospective collection reduces memory bias | High participant burden, reactivity alters intake [4] | |

| Digital & Image-Based | Diet ID (DQPN) [6] [2] | Clinical screening, rapid diet quality assessment | <1 minute completion, high scalability, visual approach | Less granular nutrient data vs. recalls [2] |

| VISIDA Image-Voice System [7] | Low-literacy populations, field studies | Combines image/audio, low literacy requirement | Lower absolute intake estimates vs. recalls [7] | |

| Traqq (Repeated Short Recalls) [3] | Real-time monitoring, adolescent studies | Reduces memory bias via short intervals | Requires multiple daily engagements | |

| AI-Driven Analysis | Multimodal LLMs (ChatGPT-4o, Claude) [4] | Automated analysis, food image estimation | No user burden post-image capture, automated | Systematic underestimation (up to 37% error), portion size challenges [4] |

Emerging Methodologies: Technological Innovations and Objective Measures

Innovative approaches are addressing the limitations of traditional methods through pattern recognition, digital technology, and artificial intelligence.

Pattern Recognition and Digital Platforms

Diet Quality Photo Navigation (DQPN), implemented in the Diet ID platform, represents a paradigm shift from recall-based to pattern-recognition-based assessment. This method allows users to identify their dietary pattern from a series of images representing various cuisines and quality levels, generating almost instantaneous diet quality scores aligned with the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) [6] [2]. The platform completes comprehensive dietary assessments in approximately one minute while achieving 90% accuracy compared to traditional methods [6].

Another significant innovation is the Fixed-Quality Variable-Type (FQVT) dietary intervention approach. This methodology standardizes diet quality using validated tools like the HEI-2020 while accommodating diverse cultural preferences and dietary patterns [6] [8]. This approach is particularly valuable for multicultural nutrition research and personalized clinical interventions, as it enhances adherence and satisfaction while maintaining scientific rigor [8].

Artificial Intelligence and Image Analysis

Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly multimodal large language models (LLMs), offer promising solutions for automated dietary assessment. A 2025 validation study evaluated three leading LLMs—ChatGPT-4o, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and Gemini 1.5 Pro—for estimating nutritional content from standardized food photographs [4].

- Performance Metrics: ChatGPT and Claude demonstrated similar accuracy with Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) values of 36.3% and 37.3% for weight estimation, and 35.8% for energy estimation—accuracy levels comparable with traditional self-reported methods but without associated user burden. Gemini showed substantially higher errors across all nutrients (MAPE 64.2%-109.9%) [4].

- Systematic Biases: All models exhibited systematic underestimation that increased with portion size, with bias slopes ranging from -0.23 to -0.50, indicating significant challenges in accurately assessing larger portions [4].

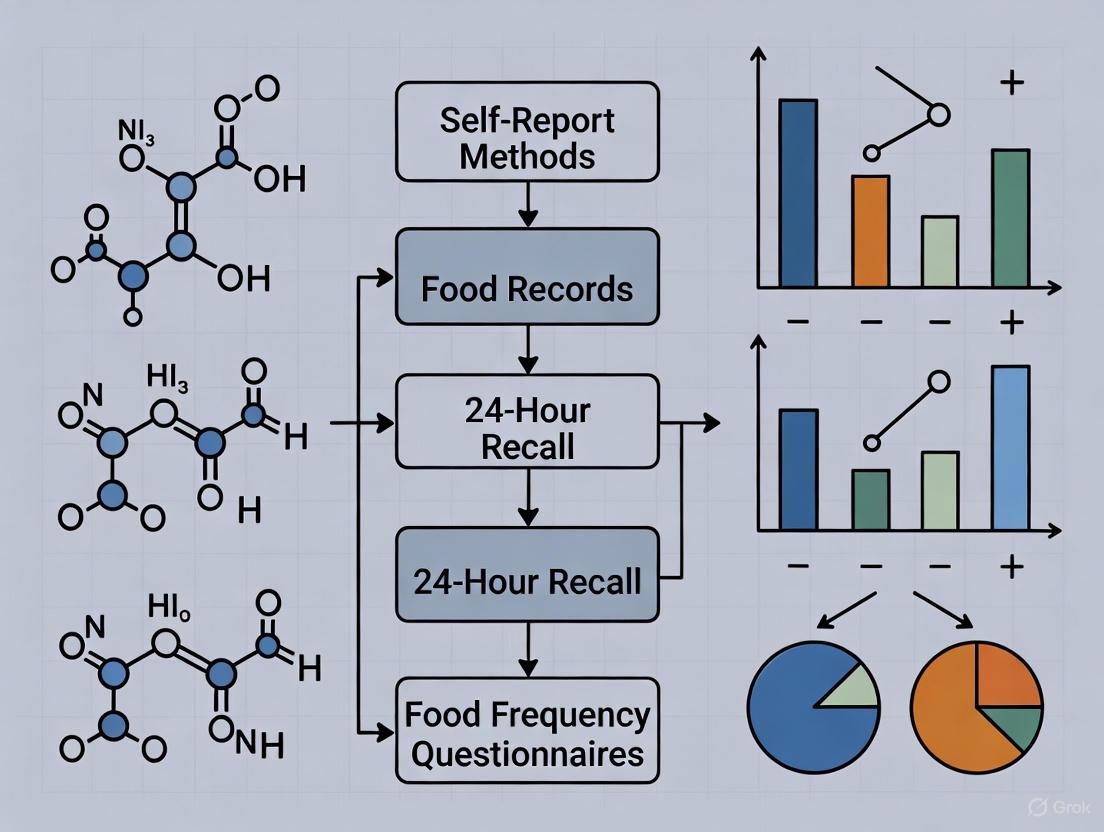

Figure 1: AI Dietary Analysis Workflow - This diagram illustrates the standardized process for AI-based dietary assessment from image capture to nutrient estimation, highlighting the systematic underestimation identified as a key limitation in current models [4].

Comparative Performance: Experimental Data and Validation Studies

Rigorous validation studies provide critical data for evaluating the relative performance of different dietary assessment methodologies.

Diet ID (DQPN) Validation Protocol

A 2023 study directly compared DQPN against traditional methods in a sample of 90 participants, with 58 completing all assessments [2].

- Experimental Protocol: Participants completed three assessment methods: DQPN, a 3-day food record via ASA24, and a Food Frequency Questionnaire (DHQ III). The study evaluated correlations for diet quality (HEI-2015), food groups, and nutrient intake [2].

- Key Findings: DQPN demonstrated strong correlation with traditional methods for overall diet quality measurement (r=0.58 vs. FFQ, r=0.56 vs. FR), with test-retest reliability of r=0.70 [2]. While DQPN performed excellently for diet quality assessment, traditional methods provided more granular nutrient-level data.

VISIDA Image-Voice System Evaluation

A 2025 study evaluated the Voice-Image Solution for Individual Dietary Assessment (VISIDA) in Cambodian women and children [7].

- Methodology: The study collected dietary data using VISIDA for two 3-day periods separated by interviewer-administered 24-hour recalls, comparing estimated nutrient intakes across methods [7].

- Results: VISIDA produced lower nutrient intake estimates compared to 24-hour recalls, with statistically significant differences for 80% of nutrients in mothers and 32% in children. However, the two VISIDA recordings showed no statistically significant differences, demonstrating high test-retest reliability [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Dietary Assessment Methods

| Validation Metric | Diet ID (DQPN) [2] | Traditional FFQ [2] | Traditional Food Record [2] | AI (ChatGPT-4o) [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completion Time | ~1 minute [6] | 30-60 minutes [2] | 15-30 minutes/day [2] | Near-instant after image capture |

| Diet Quality Correlation (HEI) | 0.56-0.58 [2] | Reference | 0.56 vs. DQPN [2] | Not tested |

| Test-Retest Reliability | 0.70 [2] | 0.40-0.70 (literature) [2] | Varies | Not established |

| Energy Intake MAPE | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 35.8% [4] |

| Weight Estimation MAPE | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 36.3% [4] |

| Key Advantage | Speed, scalability | Habitual intake capture | Detailed nutrient data | No participant burden |

Researchers conducting dietary assessment studies require specific tools and resources to ensure methodological rigor. The following table details key solutions used in the validation studies discussed in this article.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Assessment Studies

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Research Application | Example Use in Validation Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASA24 (Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Recall) [2] | Self-administered 24-hour dietary recall | Food record collection in validation studies | Used as reference method in DQPN validation [2] |

| Healthy Eating Index (HEI) [6] [8] | Diet quality scoring metric | Standardized assessment of overall diet quality | Primary outcome in FQVT and DQPN studies [6] [2] |

| DHQ III (Dietary History Questionnaire) [2] | Food frequency questionnaire | Assessment of habitual dietary intake | Comparison method in DQPN validation [2] |

| USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) [5] [2] | Nutrient composition database | Conversion of foods to nutrient values | Underlying database for ASA24 and DHQ III [2] |

| Dietist NET [4] | Nutrient calculation software | Reference method nutrient analysis | Used for reference values in AI validation study [4] |

The evolving landscape of dietary assessment presents researchers and clinicians with multiple methodological options, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Traditional methods (24-hour recalls, FFQs, food records) continue to provide valuable, granular nutrient data but suffer from significant participant burden and measurement error [4] [2]. Emerging digital tools like Diet ID offer rapid, scalable diet quality assessment with minimal participant burden, making them particularly suitable for clinical screening and large-scale public health monitoring [6] [2]. AI-based approaches demonstrate promising automation capabilities but currently lack the precision required for clinical applications where accurate quantification is critical [4].

The choice of assessment method should be guided by the specific research question, population characteristics, and precision requirements. For drug development professionals and researchers, hybrid approaches that combine the scalability of digital tools with the precision of traditional methods for validation may offer the most robust strategy. The ongoing development of standardized quality assessment frameworks, such as the FNS-Cloud data quality assessment tool, will further support researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies and ensuring the scientific integrity of nutrition research [9].

Accurate dietary assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology, essential for understanding the links between diet and health outcomes such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [10] [11]. However, diet represents a complex, dynamic exposure prone to variation across days, seasons, and the lifecycle, making its precise measurement notoriously challenging [12] [13]. Among the most established tools for capturing dietary intake in research are three traditional self-report instruments: Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), 24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24HRs), and Food Records (FRs). Each method possesses distinct strengths, limitations, and applications, and all introduce measurement error that must be considered in data analysis and interpretation [12] [14] [11]. This guide provides a comparative overview of these instruments, framing them within the broader context of dietary assessment research that increasingly seeks to validate self-reported data against objective biomarkers.

Instrument Profiles and Comparative Analysis

The following section details the design, application, and relative performance of each dietary assessment method.

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs)

FFQs are designed to retrospectively measure habitual long-term dietary intake, typically over the past month or year [12] [11]. Participants report their consumption frequency for a predefined list of food items, often with semi-quantitative portion size estimates. The FFQ is a cost-effective and practical tool for large-scale epidemiological studies, enabling the ranking of individuals by their intake levels [12] [15]. However, because it limits the scope of foods that can be queried and relies on generic memory, it is less precise for measuring absolute intakes of specific nutrients [11].

- Relative Validity: A validation study of a web-based FFQ (WebFFQ) against repeated 24-hour recalls found Spearman's correlation coefficients ranging from 0.19 for iodine to 0.71 for juice, demonstrating reasonable ranking abilities for most nutrients and foods [12] [13].

- Measurement Error: FFQs are subject to systematic bias. Studies comparing FFQ-derived energy and protein intake against recovery biomarkers (doubly labeled water and urinary nitrogen) have found that FFQs explain only a small percentage of the variation in true intake (e.g., 3.8% for energy, 8.4% for protein) without calibration [10].

24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24HRs)

The 24HR involves a detailed account of all foods and beverages consumed by an individual over the previous 24 hours [11]. Traditionally administered by a trained interviewer using structured probes, automated self-administered versions are now available [11]. Multiple non-consecutive 24HRs are required to account for day-to-day variation and estimate usual intake.

- Relative Validity: While also prone to error, data from 24HRs are generally considered less biased than FFQs and are often used as a reference method in validation studies [12] [13].

- Measurement Error: Compared to FFQs, 24HRs have been shown to be a less biased estimator of energy intake. Biomarker studies indicate that 24HRs perform better than FFQs for estimating energy and protein, but still incorporate significant error, explaining 2.8% and 16.2% of biomarker variation for energy and protein, respectively, before calibration [10].

Food Records (FRs)

In this method, participants record all foods, beverages, and supplements consumed as they are consumed, typically for 3-4 days [11]. Foods are often weighed or measured, requiring a highly literate and motivated participant population. A key limitation is reactivity—the tendency for participants to alter their usual diet because they are recording it [11].

- Relative Performance: When compared against recovery biomarkers, food records provide a stronger estimate of energy and protein intake than FFQs, with 24HRs being intermediate. One study showed food records could explain 7.8% and 22.6% of biomarker variation for energy and protein, respectively, outperforming FFQs [10].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and comparative performance of these three instruments.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Traditional Dietary Assessment Instruments

| Feature | Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | Food Record (FR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Assess habitual, long-term intake | Capture recent or short-term intake | Capture current, detailed intake |

| Time Frame | Months to a year | Previous 24 hours | Real-time recording over multiple days |

| Data Collection | Self-administered; retrospective | Interviewer-administered or automated; retrospective | Self-administered; prospective |

| Key Strengths | Cost-effective for large studies; ranks individuals by intake | Does not require literacy; less reactivity than FRs | High detail for specific days; does not rely on memory |

| Key Limitations | Systematic bias; limited food list; less precise for absolute intake | Relies on memory; high day-to-day variability; multiple recalls needed | High participant burden; reactivity can alter intake |

| Correlation with Biomarkers | Lower for energy (r² = 3.8%) [10] | Intermediate for energy (r² = 2.8%) [10] | Higher for energy (r² = 7.8%) [10] |

| Participant Burden | Moderate | Low per recall, but higher for multiple | High |

| Ideal Use Case | Large epidemiological studies to rank exposure | Estimating population mean intake or usual intake with multiple recalls | Small studies requiring precise, short-term intake data |

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from Validation Studies

| Study Context | Comparison | Key Metric | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hordaland Health Study [12] [13] | WebFFQ vs. three 24HRs | Spearman's Correlation (rs) | Range: 0.19 (Iodine) to 0.71 (Juice); >72% of participants classified in same/adjacent quartile. |

| Women's Health Initiative (NPAAS) [10] | FFQ, 24HR, FR vs. Biomarkers (Energy) | % of Biomarker Variation Explained (before calibration) | FFQ: 3.8%; 24HR: 2.8%; FR: 7.8% |

| Women's Health Initiative (NPAAS) [10] | FFQ, 24HR, FR vs. Biomarkers (Protein) | % of Biomarker Variation Explained (before calibration) | FFQ: 8.4%; 24HR: 16.2%; FR: 22.6% |

| Nutrition Journal Study [15] | FFQ vs. two 24HRs (Environmental Impact) | Attenuation Coefficient (λ) | FFQ attenuation coefficient for diet-related environmental impact was 0.56. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

A critical component of dietary assessment research involves validating self-report instruments against more objective measures. The following workflows are central to this process.

Relative Validation: FFQ versus 24-Hour Recalls

This protocol evaluates the relative validity of an FFQ by using repeated 24-hour recalls as a reference method [12] [13].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Dietary Validation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Web-based FFQ | The test instrument; assesses habitual diet over a reference period (e.g., 279 food items with portion size images) [12]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24HRs) | The reference instrument; multiple non-consecutive recalls capture day-to-day variation to estimate usual intake [12] [11]. |

| Food Composition Database | Converts reported food consumption into nutrient intakes (e.g., KostBeregningsSystemet, Dutch food composition table) [12] [15]. |

| Statistical Packages | Perform correlation analyses (Spearman's), cross-classification, and compute attenuation coefficients to quantify measurement error [12] [15]. |

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: A subsample representative of the main study population is recruited (e.g., n=67 in HUSK3) [12].

- Data Collection: Participants complete the FFQ and multiple (e.g., three) non-consecutive 24HRs, which can be conducted in-person or via telephone [12].

- Data Processing: Nutrient and food intakes from both methods are calculated by linking consumed items to a food composition database [12] [15].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Rank Correlation: Spearman's correlation coefficients are calculated between intake estimates from the two instruments.

- Cross-Classification: The proportion of participants classified into the same or adjacent quartile by both methods is determined.

- Bland-Altman Plots: Visualize the agreement between the two methods and identify any systematic bias.

- Calibration Coefficients: Linear regression models are used to compute coefficients (ranging from 0 to 1) that indicate how well the FFQ predicts intake measured by the 24HRs [12] [13].

Diagram 1: Workflow for FFQ vs. 24HR Validation Study

Biomarker Validation: Doubly Labeled Water and Urinary Nitrogen

The most rigorous assessment of dietary self-report accuracy involves recovery biomarkers, which objectively measure intake of specific nutrients [10] [14].

Methodology:

- Objective Intake Measurement:

- Energy: Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) is measured over a 1-2 week period using the Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) method. In weight-stable individuals, TEE equals habitual Energy Intake [10] [14].

- Protein: Protein intake is measured from 24-hour urinary nitrogen excretion, using the formula: Protein (g) = 6.25 × Urinary Nitrogen ÷ 0.81, where 0.81 represents the average recovery rate [10].

- Self-Report Data Collection: Participants concurrently complete the self-report instruments (FFQ, 24HR, FR).

- Comparison and Calibration: Reported intakes are compared to biomarker values. Regression calibration is used to develop equations that adjust self-reported data for systematic error related to factors like body mass index (BMI), age, and ethnicity [10].

Diagram 2: Biomarker Validation Study Design

The Challenge of Measurement Error

A consistent finding across nutritional research is that all self-report instruments are prone to measurement errors, which can be random or systematic [14] [11].

- Systematic Under-Reporting: A major issue is the systematic under-reporting of energy intake, which increases with BMI. This is thought to be related to concerns about body weight and social desirability bias [14].

- Differential Misreporting: Not all foods are under-reported equally. Protein intake tends to be less under-reported compared to other macronutrients, and the specific foods commonly under-reported may vary [14].

- Impact on Research: This systematic measurement error attenuates (weakens) observed diet-disease relationships, potentially obscuring real associations [10] [14]. For instance, in the Women's Health Initiative, associations between calibrated energy intake and cancer incidence became apparent only after correcting for measurement error in the FFQ [10].

FFQs, 24HRs, and Food Records each occupy a critical niche in dietary assessment. FFQs are unparalleled for ranking individuals by habitual intake in large-scale studies, while 24HRs provide valuable estimates of group-level mean intake and food records offer high detail for short-term studies. The fundamental challenge common to all is measurement error, predominantly systematic under-reporting. Consequently, the choice of instrument must be guided by the research question, study design, and target population. Modern research increasingly relies on multi-faceted approaches, using 24HRs as a reference standard and recovery biomarkers for objective validation, to better understand and correct for these errors, thereby strengthening the evidence base for diet and health relationships.

In nutritional epidemiology and clinical research, self-report instruments such as food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour recalls, and food records serve as fundamental tools for capturing dietary intake data. While these methods are widely used due to their practicality and low cost, they are susceptible to significant measurement errors that can compromise data validity and subsequent research conclusions. These errors stem from the complex interaction between respondents and assessment methodologies, leading to three primary limitations: recall bias, social desirability bias, and reactivity. Understanding the mechanisms, magnitude, and impact of these biases is crucial for interpreting dietary data accurately and advancing nutritional science. This analysis examines the inherent limitations of self-reported dietary assessment methods within the broader context of moving toward more objective measurement approaches.

Defining the Biases: Mechanisms and Impacts

Recall Bias

Recall bias occurs when participants inaccurately remember or report past dietary consumption. This bias is particularly problematic for methods that rely on specific memory (like 24-hour recalls) or generic memory (like FFQs that ask about usual intake over months or years) [16] [17]. The cognitive process of reporting dietary intake is complex, involving multiple stages where memory lapses can occur [17].

Common manifestations of recall bias include:

- Omissions: Forgetting to report entire eating occasions, specific foods, or additions like condiments and salad dressings [17]. Research comparing 24-hour recalls to directly observed intake found that foods like tomatoes, mustard, and cheese were frequently omitted [17].

- Intrusions: Incorrectly reporting foods that were not actually consumed during the reference period [17].

- Inaccurate Details: Misremembering portion sizes, food preparation methods, or additions to foods [17].

The retention interval (time between consumption and recall) significantly impacts accuracy, with shorter intervals generally producing more reliable data [17]. Automated multiple-pass methods like the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool (ASA24) and the Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) incorporate probing questions and memory aids to mitigate recall bias by systematically prompting respondents to remember forgotten items [17].

Social Desirability Bias

Social desirability bias arises when respondents alter their reported intake to align with perceived social norms or research expectations. This bias disproportionately affects foods considered "healthy" or "unhealthy," leading to systematic misreporting rather than random error [18] [16].

Key findings on social desirability bias:

- Directional Under-reporting: A seminal study found social desirability scores were negatively correlated with reported energy intake, producing a downward bias of approximately 450 kcal over the interquartile range of social desirability scores [18]. This under-reporting was approximately twice as large for women as for men [18].

- Susceptibility Across Methods: Both FFQs and 24-hour recalls demonstrate susceptibility. A randomized controlled trial testing social approval bias found that participants who received materials emphasizing fruit and vegetable consumption reported significantly higher intakes than controls (5.2 vs. 3.7 servings per day on FFQ) [16].

- Differential Effects by Food Type: Social desirability bias more strongly affects reporting of foods with clear health perceptions (like fruits, vegetables, and high-fat foods) compared to neutral foods [16].

This bias poses particular challenges in nutritional intervention studies where participants may be aware of the study goals and modify their reports to demonstrate compliance [16].

Reactivity

Reactivity occurs when the process of measurement itself alters participants' normal dietary behavior. Also termed "reactivity bias," this phenomenon is especially prominent with food records, as participants may simplify their diets, choose different foods, or reduce intake to make recording easier [11] [19].

Characteristics of reactivity:

- Method-Specific Vulnerability: Food records have high potential for reactivity as participants know their intake is being recorded in real-time, whereas 24-hour recalls and FFQs have lower reactivity as intake is reported after consumption [11].

- Behavioral Change Mechanism: The awareness of being monitored can lead to conscious or unconscious modifications in eating patterns, potentially reducing consumption of foods perceived as undesirable or complex to record [11].

- Digital Method Considerations: Emerging image-based dietary assessment methods may also be susceptible to reactivity, as knowing one must photograph foods may influence food choices [19].

Comparative Quantitative Analysis of Bias Magnitude

Table 1: Comparative Magnitude of Self-Report Biases Across Assessment Methods

| Bias Type | Assessment Method | Reported Effect Size | Population Characteristics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Desirability | 7-day diet recall (similar to FFQ) | ~50 kcal/point on social desirability scale [18] | Adults (n=163) | Large downward bias, twice as large in women |

| Social Desirability | 7-day diet recall vs. 24-hour recall | ~450 kcal over interquartile range [18] | Free-living adults | Individuals with highest fat/energy intake showed largest downward bias |

| Social Approval | Food Frequency Questionnaire | 5.2 vs. 3.7 fruit/vegetable servings (intervention vs. control) [16] | Women aged 35-65 (n=163) | 41% higher reporting in prompted group |

| Social Approval | Limited 24-hour recall | 61% vs. 32% reported ≥3 eating occasions (intervention vs. control) [16] | Women aged 35-65 (n=163) | Near doubling of positive responses in intervention group |

| Recall Bias | 24-hour recall (omissions) | 42% tomatoes, 17% mustard, 16% peppers not reported [17] | Adults vs. observed intake | Condiments and vegetable additions most frequently omitted |

Table 2: Methodological Vulnerabilities to Different Bias Types

| Assessment Method | Recall Bias | Social Desirability Bias | Reactivity | Primary Error Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Records | Low (real-time recording) | Moderate | High [11] | Systematic (reactivity) |

| 24-Hour Recalls | High [17] | Moderate [16] | Low [11] | Random (memory) |

| Food Frequency Questionnaires | High (generic memory) [16] | High [18] [16] | Low [11] | Systematic (social desirability) |

| Screening Tools | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Both random and systematic |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Quantification

Protocol 1: Social Desirability Bias Assessment

Hebert et al. developed a rigorous protocol to quantify social desirability bias in dietary self-report [18]:

Design: Comparative validation study with randomized administration of different dietary assessment methods.

Participants: Free-living adults representative of the general population.

Methodology:

- Administered social desirability scale to all participants to establish baseline tendency

- Collected dietary data using multiple 24-hour recalls on seven randomly assigned days as reference method

- Administered two 7-day diet recalls (cognitively similar to FFQs) - one at beginning (pre) and one at end (post) of test period

- Compared nutrient scores between methods using correlation and multiple linear regression analysis

Key Metrics: Difference in energy and nutrient estimates between 7-day diet recalls and 24-hour recalls, correlated with social desirability scores.

Statistical Analysis: Multiple linear regression to isolate effect of social desirability score on nutrient estimation while controlling for other variables.

Protocol 2: Social Approval Bias Randomized Trial

A randomized controlled trial specifically tested social approval bias using a blinded design [16]:

Design: Single-blind randomized controlled trial.

Participants: 163 women aged 35-65 years, randomly selected from commercial database.

Intervention:

- Intervention group received letter describing study as focused on fruit/vegetable intake, including health benefits statement, 5-A-Day sticker, and refrigerator magnet

- Control group received neutral letter describing study as general nutrition survey without specific fruit/vegetable messaging

Assessment:

- 8-item FFQ from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)

- Limited 24-hour recall specific to fruits and vegetables

- All interviewers blinded to treatment assignment

- Interviews conducted within 10 days of sending letters

Outcomes: Reported fruit/vegetable servings by FFQ; proportion reporting fruits/vegetables on ≥3 occasions via 24-hour recall.

Visualizing Cognitive Processes and Bias Pathways

Cognitive Processes and Bias Pathways in Dietary Self-Report

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Dietary Assessment Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Reference method for measuring total energy expenditure [19] | Validation of energy intake reporting | Objective, non-invasive; considered gold standard for energy validation |

| Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool (ASA24) | Self-administered 24-hour recall system [11] [1] | Large-scale dietary data collection | Automated multiple-pass method; reduces interviewer burden and cost |

| Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) | Interviewer-administered 24-hour recall [17] | National surveys (NHANES) | Standardized probing questions to enhance recall completeness |

| Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) | Provides nutrient values for foods [5] | Nutrient analysis of reported foods | Contains energy and 64 nutrients for ~7,000 foods |

| Social Desirability Scales | Quantifies tendency toward socially desirable responding [18] | Measurement of social desirability bias | Allows statistical control for this bias in analyses |

| Recovery Biomarkers | Objective measures of specific nutrient intake (protein, potassium, sodium) [11] | Validation of specific nutrient reporting | Limited to specific nutrients but highly accurate |

Implications for Research and Clinical Practice

The pervasive nature of self-report biases has significant implications across research contexts. In epidemiological studies, measurement error distorts observed associations between diet and disease, reducing statistical power to detect true relationships [17]. For public health monitoring, these biases can lead to erroneous estimates of population nutrient adequacy and inaccurate assessments of compliance with dietary guidelines [5] [17]. In intervention research, measurement error can mask true intervention effects, particularly if error differs between intervention and control groups [16] [17].

Mitigation strategies include:

- Using multiple assessment methods to triangulate findings

- Incorporating recovery biomarkers where possible for validation [11] [19]

- Applying statistical adjustment techniques to correct for measured biases [18]

- Developing technology-based methods that reduce cognitive burden [11] [19]

- Implementing standardized protocols with trained interviewers to minimize systematic error [20]

Recall bias, social desirability bias, and reactivity represent fundamental limitations of self-reported dietary assessment methods that significantly impact data validity across research and clinical contexts. The magnitude of these biases can be substantial, with social desirability alone capable of introducing under-reporting of approximately 450 kcal in vulnerable individuals. While methodological improvements like automated multiple-pass recalls and statistical adjustments can mitigate some error, these biases remain inherent to self-report methodologies. This understanding underscores the importance of continued development and validation of objective assessment methods, including recovery biomarkers and technology-enhanced tools, to advance nutritional epidemiology and inform evidence-based dietary recommendations. Researchers must carefully consider these limitations when designing studies, interpreting findings, and translating results into clinical practice and public health policy.

For decades, nutritional science has relied predominantly on self-reported dietary assessment methods including Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour recalls, and food diaries [11] [21]. While these tools have contributed valuable epidemiological data, they are notoriously subject to both random and systematic measurement error that fundamentally limits their reliability and accuracy [19] [22]. The emerging recognition of these limitations has catalyzed a paradigm shift toward objective biochemical measures that can complement or potentially replace traditional approaches.

Key limitations of self-reported methods include significant under-reporting of energy intake, particularly among females and overweight or obese individuals [19] [22]. Additional challenges include portion size estimation errors, memory reliance, social desirability bias, and reactivity where participants change their eating habits during assessment periods [21] [22]. A systematic review comparing self-reported energy intake to the gold standard doubly labeled water method found significant under-reporting across most studies, with particularly pronounced effects within recall-based methods [19].

The Emergence of Objective Biomarkers

Objective biomarkers of dietary intake provide independent measures that bypass the cognitive limitations and biases of self-report. These biomarkers are typically biological specimens that indicate intake of specific foods or nutrients through direct measurement of their metabolic products or related physiological compounds [22].

Classification of Dietary Biomarkers

Table 1: Classification of Dietary Biomarkers with Examples

| Biomarker Category | Definition | Research Applications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery Biomarkers | Measures where intake is quantitatively recovered in biological samples | Validation of self-reported data; considered reference standards | Urinary nitrogen for protein intake; Doubly Labeled Water for energy expenditure [11] [19] |

| Concentration Biomarkers | Reflect circulating or tissue levels of dietary compounds | Assessing status and relative intake of specific nutrients | Serum carotenoids for fruit/vegetable intake; Omega-3 fatty acids for fish consumption [22] |

| Predictive Metabolite Patterns | Multiple metabolites combined using machine learning | Objective classification of dietary patterns and food intake | Poly-metabolite scores for ultra-processed food consumption [23] [24] |

Novel Biomarker Approaches

Recent technological advances have enabled the development of multi-metabolite panels that collectively provide a more comprehensive objective assessment of dietary intake. In a landmark study published in May 2025, NIH researchers identified hundreds of metabolites in blood and urine that correlated with ultra-processed food consumption [23] [24]. Using machine learning, they developed poly-metabolite scores that could accurately differentiate between highly processed and unprocessed diet phases in a controlled feeding trial [23]. This approach represents a significant advancement beyond single nutrient biomarkers toward comprehensive dietary pattern assessment.

Simultaneously, research initiatives like the Dietary Biomarkers Study are systematically investigating the body's absorption, digestion, and uptake responses to common foods to identify novel intake biomarkers [25]. These studies aim to establish objective measures for specific foods including chicken, beef, salmon, whole wheat bread, oats, potatoes, corn, cheese, soybeans, and yogurt [25].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Objective Methods

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Dietary Assessment Approaches

| Characteristic | Traditional Self-Report Methods | Objective Biomarker Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | Participant memory and recording | Biological samples (blood, urine, etc.) |

| Measurement Basis | Estimated consumption | Metabolic products or physiological responses |

| Susceptibility to Bias | High (memory, social desirability, reactivity) | Low (analytical variability only) |

| Time Frame Assessed | Variable (single day to years) | Typically recent intake (hours to weeks) |

| Nutrient/Food Specificity | Can assess entire diet | Often limited to specific nutrients/foods |

| Analytical Requirements | Low to moderate | High (specialized laboratory equipment) |

| Participant Burden | High (time and cognitive effort) | Low (sample collection only) |

| Cost Considerations | Lower per participant | Higher per participant |

The integration of traditional and objective methods represents a promising approach. As noted by Dr. Miriam Sonntag of the PAN Academy, "New methods are unlikely to replace traditional methods such as food diaries. But we can combine them to get a better picture of what and how much people consume" [22]. This integrated approach leverages the comprehensive dietary pattern data from self-report with the objective validation provided by biomarkers.

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Development

Protocol 1: Poly-Metabolite Score Development for Ultra-Processed Foods

A recent NIH study exemplifies the rigorous methodology required for biomarker development [23] [24]:

Study Design: Combined observational and experimental data. Observational data came from 718 older adults in the Interactive Diet and Activity Tracking in AARP (IDATA) Study who provided biospecimens and detailed dietary information over 12 months. Experimental data came from a domiciled feeding study with 20 subjects admitted to the NIH Clinical Center [23].

Intervention Protocol: Participants were randomized to either a diet high in ultra-processed foods (80% of calories) or a diet with zero ultra-processed foods (0% energy) for two weeks, immediately followed by the alternate diet for two weeks in a crossover design [23] [24].

Biospecimen Collection: Blood and urine samples were collected throughout both study phases for comprehensive metabolomic analysis [24].

Analytical Approach: Machine learning algorithms identified patterns of metabolites predictive of high ultra-processed food intake, and poly-metabolite scores were calculated based on these signatures [23].

Validation: The biomarker scores were tested for their ability to accurately differentiate between the highly processed and unprocessed diet phases within the same individuals [24].

Protocol 2: Doubly Labeled Water Validation for Energy Intake

The doubly labeled water (DLW) method remains the gold standard for validating energy intake assessment:

Principle: Measures carbon dioxide production by assessing the difference in elimination rates of deuterium (²H) and oxygen-18 (¹â¸O) from labeled water [19].

Administration: Participants consume a dose of water containing both isotopes, with the initial dose determined by standardized equations according to body weight [19].

Sample Collection: Urine samples are collected over 7-14 days to account for short-term day-to-day variation in physical activity [19].

Analysis: Isotope elimination rates are used to calculate total energy expenditure, which in weight-stable individuals should equal energy intake [19].

This method has been used extensively to demonstrate the systematic under-reporting inherent in self-reported dietary assessment methods [19].

Visualizing Biomarker Development Workflows

Biomarker Development Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process from initial study design through validation required for developing robust dietary biomarkers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotopes | Doubly Labeled Water (²H₂¹â¸O) | Gold standard validation of energy intake assessment [19] |

| Metabolomics Kits | LC-MS/MS metabolite panels | Comprehensive profiling of hundreds to thousands of metabolites in biospecimens [23] |

| Biospecimen Collection | Urine collection kits, Blood collection tubes | Standardized sample acquisition for biomarker analysis [23] [25] |

| Reference Standards | Certified nutrient biomarkers | Analytical validation and quality control (e.g., urinary nitrogen, serum carotenoids) [11] [22] |

| Dietary Assessment Platforms | ASA24, Automated Multi-Pass Method | Collection of self-reported dietary data for correlation with biomarkers [11] [21] |

| Algorithm Development Tools | Machine learning libraries | Development of poly-metabolite scores and predictive models [23] [24] |

| Ononitol, (+)- | D-Pinitol | High-purity D-Pinitol for research. Explore its insulin-like, anti-diabetic, and anti-osteoporotic applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| PTP1B-IN-4 | PTP1B Inhibitor | Explore our potent PTP1B inhibitor for diabetes, obesity, and cancer signaling research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Future Directions and Research Applications

The field of objective dietary assessment is rapidly evolving with several promising directions:

Fixed-Quality Variable-Type (FQVT) Dietary Interventions

A novel approach called Fixed-Quality Variable-Type dietary intervention standardizes diet quality using objective measures while allowing for a range of diet types that cater to individual preferences, ethnicities, and cultures [8] [26]. This method uses validated tools like the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 2020 to fix diet quality within a prespecified range while accommodating diverse dietary patterns [26]. Biomarkers play a crucial role in objectively verifying that different diet types meet the same nutritional quality standards.

Integrated Assessment Approaches

Future dietary assessment will likely combine traditional methods, technological innovations, and biomarkers in complementary approaches:

- Image-assisted methods using smartphones to improve portion size estimation [21] [22]

- Wearable sensors that automatically capture dietary intake data [21] [22]

- Multi-metabolite panels for objective verification of specific dietary patterns [23] [22]

Integrated Assessment Approach: Combining multiple methodologies provides more robust dietary assessment than any single approach.

The paradigm shift from subjective to objective dietary assessment represents a fundamental transformation in nutritional science. While traditional self-reported methods will continue to have utility for capturing comprehensive dietary patterns, objective biomarkers provide essential validation and complementary data that bypass cognitive limitations and reporting biases. The integration of metabolomic profiles, recovery biomarkers, and technology-assisted methods with traditional approaches offers the most promising path forward for obtaining accurate, reliable dietary data.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances enable more precise quantification of dietary exposures in clinical trials, enhanced understanding of diet-disease relationships, and ultimately, more effective nutritional interventions and therapeutics. As the field continues to evolve, objective biomarkers will play an increasingly central role in advancing nutritional science from estimation to precise measurement.

Dietary assessment is a fundamental component of nutrition research, enabling the understanding of diet's role in human health and disease, and informing nutrition policy and dietary recommendations [11]. However, accurately measuring dietary exposures through self-report is notoriously challenging, subject to both random and systematic measurement error that can compromise data quality and subsequent conclusions [11] [14]. The selection of an appropriate dietary assessment method is therefore critical, as it must align with specific research questions, study designs, and population characteristics to yield meaningful results.

Traditional dietary assessment methods include food records, food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), and 24-hour recalls, each with distinct strengths and limitations [11]. In recent years, digital and mobile technologies have transformed these traditional methods, offering new opportunities to enhance accuracy, reduce burden, and improve efficiency in data collection and processing [21] [27]. Despite these advancements, methodological challenges persist, particularly concerning systematic misreporting that varies across population subgroups [14].

This comparison guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an evidence-based framework for selecting dietary assessment methods aligned with specific research objectives and population characteristics. By synthesizing current scientific evidence on method performance, validation protocols, and practical implementation considerations, we aim to support methodological decisions that optimize validity, reliability, and feasibility in nutrition research.

Comprehensive Comparison of Dietary Assessment Methods

Dietary assessment methods can be broadly categorized based on their temporal framework (short-term vs. long-term), scope (total diet vs. specific components), and administration approach (investigator-driven vs. participant-driven) [11]. Table 1 summarizes the primary methods, their applications, and key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Dietary Assessment Methods

| Method | Primary Use | Time Frame | Data Collection Approach | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | Individual intake assessment | Short-term (previous 24 hours) | Interviewer-administered or self-administered; multiple non-consecutive days | Quantitative nutrient intake; food group consumption |

| Food Record/Food Diary | Detailed intake documentation | Short-term (typically 3-7 days) | Prospective recording by participant | Comprehensive food, beverage, and supplement consumption with timing |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Habitual dietary patterns | Long-term (months to year) | Self-administered or interviewer-administered | Frequency of food category consumption; nutrient pattern rankings |

| Dietary Screeners | Specific nutrients/food groups | Variable (typically past month/year) | Brief self-administered questionnaires | Targeted data on specific dietary components |

| Technology-Assisted Methods | Various assessment purposes | Adaptable to different time frames | Mobile apps, sensors, web-based platforms | Multiple output formats with potential real-time feedback |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The accuracy and precision of dietary assessment methods vary considerably, influenced by factors including population characteristics, study duration, and implementation quality. Table 2 presents comparative data on method performance based on validation studies against recovery biomarkers.

Table 2: Method Performance Characteristics Based on Biomarker Validation

| Method | Energy Underreporting Range | Most Accurately Measured Nutrients | Population Factors Affecting Accuracy | Biomarker Correlation Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Recall | 10-25% (varies by BMI) [14] | Macronutrients, protein [11] | BMI (increased underreporting with higher BMI) [14] | Moderate to strong for protein, potassium [11] |

| Food Records | 15-34% (higher in obese populations) [14] | Macronutrients, sodium [11] | Literacy, motivation, BMI [11] [21] | Moderate for protein, variable for other nutrients [14] |

| FFQ | 20-30% (systematic bias) [14] | Pattern ranking, select micronutrients [11] | Cognitive ability, memory, cultural appropriateness [11] | Weaker for energy, moderate for protein [14] |

| Technology-Assisted | Emerging evidence (potentially reduced) [21] | Dependent on implementation | Technological access, digital literacy [21] | Limited biomarker validation data available [27] |

Key Selection Criteria

Alignment with Research Objectives

The research question fundamentally dictates the most appropriate dietary assessment method. Studies investigating acute nutrient exposures or day-to-day variability in intake typically require short-term methods like 24-hour recalls or food records, which provide detailed snapshots of recent consumption [11]. For research examining long-term dietary patterns or habitual intake in relation to chronic disease outcomes, FFQs or repeated short-term measures are more appropriate, as they aim to capture usual consumption over extended periods [11] [28].

The scale of dietary assessment represents another critical consideration. Studies focusing on specific nutrients or food groups may utilize targeted screeners or modified FFQs, while comprehensive dietary assessment requires more extensive methods like multiple 24-hour recalls or detailed food records [11]. The level of detail needed also varies – while some research questions require precise quantification of absolute nutrient intakes, others may only need relative ranking of individuals within a population [11] [29].

Studies incorporating dietary supplements require additional assessment components, as traditional methods often fail to capture these exposures adequately. Approximately half of U.S. adults and one-third of children use dietary supplements, necessitating specific assessment strategies to comprehensively evaluate total nutrient exposure [30].

Population Considerations

Population characteristics significantly influence the suitability and performance of dietary assessment methods. Literacy and educational level affect the feasibility of self-administered methods like FFQs and food records, with low literacy populations often requiring interviewer-administered approaches [11] [21]. Age and cognitive ability impact memory recall and attention span, making shorter assessments or methods with external memory aids more appropriate for children, older adults, or cognitively impaired individuals [21] [31].

Body mass index (BMI) consistently correlates with underreporting, particularly for energy-dense foods, with higher BMI associated with greater underreporting across all self-report methods [14]. This systematic bias has profound implications for obesity research, suggesting caution when using self-reported energy intake in studies of energy balance [14].

Cultural and linguistic factors necessitate method adaptation, including food list modification for FFQs, use of culturally appropriate portion size estimation aids, and availability of bilingual materials or interpreters [11] [28]. Technological access and digital literacy increasingly influence method selection as technology-based tools become more prevalent, potentially excluding populations with limited resources or technology experience [21] [27].

Practical Implementation Factors

Participant burden varies substantially across methods, from brief screeners requiring <15 minutes to complete, to detailed food records or multiple 24-hour recalls demanding >20 minutes per assessment [11]. Higher burden methods typically experience reduced compliance and data quality over time, necessitating careful consideration of assessment duration and frequency [11] [29].

Resource requirements encompass personnel time, training needs, equipment, and data processing costs. Interviewer-administered 24-hour recalls require substantial trained personnel investment, while self-administered FFQs offer cost-efficiency for large samples [11]. Technology-based methods may reduce long-term costs but require significant initial development investment and technical support [21] [27].

Data processing and analysis considerations include the availability of appropriate nutrient databases, coding requirements, and analytical expertise. Methods producing quantitative output (24-hour recalls, food records) enable more detailed nutrient analysis, while FFQs primarily support pattern analysis and ranking [11] [28].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Biomarker Validation Approaches

The gold standard for validating self-reported dietary intake involves comparison with recovery biomarkers, which provide objective measures of nutrient consumption. The doubly labeled water (DLW) method measures total energy expenditure through the differential elimination kinetics of two stable isotopes (deuterium and 18O), providing a biomarker of habitual energy intake under weight-stable conditions [14]. Validation protocols typically involve administering the dietary assessment method concurrently with DLW measurement over 1-2 weeks, enabling direct comparison of reported energy intake against measured energy expenditure [14].

Urinary nitrogen measurement serves as a recovery biomarker for protein intake, based on the relatively constant proportion of dietary nitrogen excreted in urine [14]. Validation studies collect 24-hour urine samples alongside dietary reporting, with comparisons adjusted for known routes of nitrogen loss. Similarly, 24-hour urinary sodium and potassium provide recovery biomarkers for assessing sodium and potassium intake [11] [14].

These biomarker comparisons have consistently revealed significant underreporting of energy intake across self-assessment methods, with systematic biases related to BMI and macronutrient composition [14]. Protein is typically the least underreported nutrient, while energy and carbohydrates show greater reporting errors [14].

Method Comparison Protocols

When recovery biomarkers are unavailable or impractical, researchers often employ method comparison approaches, where the assessment method of interest is compared against a more detailed reference method. Common protocols include:

- Comparing FFQ results against multiple 24-hour recalls or food records collected over a representative period [11] [28]

- Evaluating short screeners against comprehensive FFQs or multiple recalls for specific nutrients or food groups [11]

- Testing technology-assisted methods against traditional pen-and-paper versions or interviewer-administered assessments [21] [27]

These comparisons typically evaluate correlation coefficients, agreement in classification into intake quartiles or quintiles, and mean differences between methods [11] [28]. While less definitive than biomarker validation, these approaches provide practical information about relative method performance and suitability for specific research contexts.

Visual Decision Framework

Diagram 1: Decision Framework for Dietary Assessment Method Selection. This flowchart illustrates key decision points when selecting dietary assessment methods based on population size, time frame of interest, and required level of detail.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Dietary Assessment Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Gold standard measurement of total energy expenditure | Validation of energy intake reporting; requires mass spectrometry analysis | High cost limits sample size; excellent accuracy for habitual intake |

| 24-Hour Urinary Nitrogen | Objective biomarker of protein intake | Validation of protein reporting; requires complete urine collection | Affected by non-dietary factors; requires participant compliance |

| Digital Photography Systems | Objective food documentation and quantification | Technology-assisted food records; portion size estimation | Standardization needed for lighting, angles; requires image analysis |

| Standardized Food Models | Visual aids for portion size estimation | Interviewer-administered 24HR; portion size training | Must be culturally appropriate; regular updates for new products |

| Brand-Specific Food Databases | Enhanced food identification and nutrient matching | Technology-based assessment tools; processed food documentation | Requires continuous updating; potential for participant overload |

| Integrated Nutrient Analysis Software | Automated nutrient calculation from food intake data | All assessment methods requiring nutrient output | Database quality determines accuracy; regular updates essential |

Selecting appropriate dietary assessment methods requires careful consideration of research objectives, population characteristics, and practical constraints. The 24-hour recall currently represents the most accurate method for assessing absolute food and nutrient intakes, while FFQs offer cost-efficient approaches for ranking individuals by habitual intake in large studies [11] [30]. Food records provide detailed intake documentation but are susceptible to reactivity and participant burden [11] [21].

Technology-based methods present promising opportunities to enhance dietary assessment through reduced burden, improved efficiency, and potentially enhanced accuracy [21] [27]. However, these approaches require validation against traditional methods and biomarkers, and may introduce new challenges related to technology access and digital literacy [21] [31].

Regardless of the method selected, researchers should acknowledge and address the systematic measurement errors inherent in all self-reported dietary assessment tools [14]. Methodological transparency, including detailed reporting of assessment protocols, validation studies, and potential limitations, remains essential for interpreting results and advancing the field of nutritional epidemiology [28]. By aligning method selection with specific research needs and implementing rigorous validation protocols, researchers can optimize the quality and utility of dietary assessment in nutrition research.

A Deep Dive into Methodologies: From Established Protocols to AI-Driven Innovations

Within nutritional epidemiology and clinical research, the accurate assessment of dietary intake is fundamental to understanding the links between diet and health. For decades, two methodologies have served as traditional workhorses in the field: the Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM), a detailed 24-hour recall system, and the Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ), a type of Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) designed to capture habitual intake. Framed within the broader thesis of traditional versus objective dietary assessment research, this guide provides an objective comparison of these tools' performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

The AMPM and DHQ are built on fundamentally different approaches to capturing dietary data.

- The Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) is a computerized, interviewer-administered 24-hour dietary recall method. Its core strength lies in its structured, five-pass approach designed to enhance memory and reduce omission of foods [21] [32]. This method provides a detailed snapshot of all foods, beverages, and supplements consumed in the previous 24 hours and is the method used for the dietary interview component of the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [32].

- Diet History Questionnaires (DHQs) are typically self-administered forms that ask respondents to report their usual frequency of consumption and, in some cases, portion sizes, from a finite list of foods and beverages over a specified period, such as the past month or year [21]. The DHQ developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) is a prominent example intended to estimate an individual's habitual diet.

Table 1: Core Methodological Characteristics of AMPM and Diet History (DHQ)

| Feature | AMPM (24-Hour Recall) | Diet History (Food Frequency Questionnaire) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Capture detailed intake for a specific day (absolute intake) | Capture habitual intake over a long period (rank individuals) |

| Time Frame | Previous 24 hours | Usually past month or year |

| Administration | Interviewer-administered (computer-assisted) | Primarily self-administered |

| Data Output | Detailed list of foods, portions, timing, and context | Frequency of consumption for a pre-defined food list |

| Cognitive Demand | Relies on short-term memory | Relies on long-term memory and generalization |

| Key Strength | Detailed, quantitative day-specific data | Efficient for assessing usual diet in large cohorts |

| Key Weakness | High day-to-day variation (requires multiple recalls) | Limited detail; prone to systematic bias and measurement error |

Performance Evaluation Against Objective Biomarkers

The most rigorous evaluations of dietary assessment tools involve comparison against objective recovery biomarkers, which are not subject to the same self-reporting biases. Data from such studies reveal critical differences in the performance of AMPM and FFQs like the DHQ.

Validation Against Doubly Labeled Water and Urinary Biomarkers

A key study compared the performance of the USDA AMPM and two FFQs—the Block FFQ and the NCI's DHQ—using doubly labeled water (DLW) total energy expenditure as the criterion measure for energy intake [33]. The study involved 20 highly motivated, premenopausal women.

Table 2: Comparison of Mean Reported Energy Intake vs. Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) Criterion

| Assessment Method | Mean Reported Energy Intake (kJ) | % Difference from DLW TEE | Pearson Correlation (r) with DLW TEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLW TEE (Criterion) | 8905 ± 1881 | - | - |

| AMPM Recall | 8982 ± 2625 | +0.9% | 0.53 (P=0.02) |

| Food Record (FR) | 8416 ± 2217 | -5.5% | 0.41 (P=0.07) |

| Block FFQ | 6365 ± 2193 | -28.5% | 0.25 (P=0.29) |

| NCI DHQ | 6215 ± 1976 | -30.2% | 0.15 (P=0.53) |

The findings were clear: the AMPM and food record estimates of total energy intake did not differ significantly from the DLW measurement, while both the Block and DHQ questionnaires underestimated energy intake by approximately 28% [33]. Furthermore, the AMPM showed a stronger linear relationship with the objective biomarker (r=0.53) than either FFQ.

A larger study of men and women aged 50-74 confirmed this pattern, finding that compared to energy expenditure biomarkers, energy intake was underestimated by 15-17% on multiple ASA24 recalls (a self-administered tool based on the AMPM), 18-21% on 4-day food records, and 29-34% on FFQs [34].

Experimental Protocol for Biomarker Validation

The methodology for the study cited in Table 2 is as follows [33]:

- Participants: 20 free-living, normal-weight, premenopausal women.

- Criterion Measure: Total energy expenditure (TEE) measured by the doubly labeled water (DLW) technique over a 14-day period.

- Dietary Assessment Methods:

- AMPM: Two unannounced, interviewer-administered 24-hour recalls were collected using the USDA AMPM.

- FFQs: Participants completed both the Block FFQ and the National Cancer Institute's Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ).

- Food Record (FR): Participants completed a 14-day estimated food record to serve as an additional comparison.

- Data Analysis: Mean reported energy intakes from each dietary tool were compared statistically to the DLW TEE. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the strength of the linear relationship between each method and the biomarker.

Workflow and Research Reagents

The AMPM 5-Pass Workflow

The accuracy of the AMPM is attributed to its structured, multi-stage interview process, which is designed to systematically prompt memory and minimize omissions. The following diagram illustrates this workflow.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Conducting validated dietary assessment research requires a suite of reliable tools and databases. The following table details key resources used in studies featuring the AMPM and DHQ.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Dietary Assessment Validation

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Dietary Assessment | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Objective biomarker for total energy expenditure; serves as a criterion to validate reported energy intake [33]. | Isotopes: ^2H (Deuterium) and ^18O (Oxygen-18) |

| 24-Hour Urinary Nitrogen | Objective biomarker for protein intake; used to validate reported protein consumption [34]. | Collection of all urine over a 24-hour period. |

| 24-Hour Urinary Potassium/Sodium | Objective biomarkers for potassium and sodium intake [34]. | Collection of all urine over a 24-hour period. |

| Standardized Nutrient Database | Provides the nutrient composition for foods and supplements reported by participants; essential for converting intake data into nutrient values. | USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) [35], NHANES Dietary Supplement Database (DSD) [36] [37] |

| Standardized Assessment Tool | The software or questionnaire platform used to collect dietary data in a consistent manner. | USDA AMPM [32], NCI's ASA24 [38], NCI's Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) |

The experimental data lead to a clear conclusion regarding the performance of these traditional workhorses. When the research objective requires accurate estimation of absolute energy and nutrient intake for a group or population, the AMPM is demonstrably superior, providing intake measures that are not significantly different from those obtained by objective biomarkers [33] [34]. Its detailed, multi-pass structure effectively mitigates memory-related underreporting. In contrast, Diet History Questionnaires like the DHQ show substantial underestimation of absolute energy intake (around 28-34%) and weaker correlations with biomarker data [33] [34]. This makes them less suitable for measuring absolute intake but, due to their lower cost and burden, they remain a practical tool for ranking individuals by their habitual intake in large epidemiological studies. The choice between them must be driven by the specific research question and an understanding of their inherent measurement characteristics.

The shift from traditional, memory-dependent dietary assessment methods toward technology-assisted, objective tools represents a significant advancement in nutritional science. Traditional tools like interviewer-administered 24-hour recalls and paper food diaries have long been plagued by limitations including recall bias, measurement error, and high participant burden [39] [40]. In response, researchers have developed innovative technological solutions that enhance accuracy, reduce administrative costs, and improve user compliance. Two major categories of these solutions have emerged: comprehensive, structured recall systems like the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recall (ASA24), and a diverse ecosystem of mobile applications employing various methodologies from text entry to artificial intelligence (AI)-powered image recognition [41] [42]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technology-assisted tools, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate dietary assessment methods for their work.

Technology-assisted dietary assessment tools can be broadly classified by their primary methodology and operational paradigm. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major tools discussed in the scientific literature.

Table 1: Overview of Technology-Assisted Dietary Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | Developer/Context | Key Features | Nutrient Database & Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA24 | Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recall | National Cancer Institute (NCI) [38] | Web-based, adapts USDA's Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM), self-administered [38] [43] | Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS); provides nutrient and food group data [38] [5] |

| DietAI24 | Multimodal LLM + Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Research Framework (Yan et al.) [39] | Food image analysis, zero-shot nutrient estimation, combines MLLMs with FNDDS database [39] | FNDDS; estimates 65 distinct nutrients and food components [39] |

| NutriDiary | Smartphone-based Weighed Dietary Record | Research App (Germany) [44] | Text search, barcode scanning, free text entry; recipe editor; designed for epidemiological studies [44] | Custom database (LEBTAB) with 82 nutrients; includes branded products [44] |

| Traqq | Repeated Short Recalls (Ecological Momentary Assessment) | Research App (Netherlands) [3] | 2-hour and 4-hour recall windows to reduce memory bias; initially designed for adults [3] | Not specified in protocol; assesses energy, nutrient, and food group intake [3] |

| Bitesnap | Text + Image Entry | Commercial App [41] | Flexible food timing functionality; suitable for research and clinical settings [41] | Not specified; provides caloric and macronutrient estimates [41] |

| Voice-based Recall (DataBoard) | Voice Input/Speech Recognition | Research Tool (Pilot Study) [40] | Speech input for dietary recall; targets older adults and those with digital literacy challenges [40] | Not specified; focuses on meal composition and timing [40] |

Comparative Performance and Experimental Data

Accuracy Metrics in Controlled and Real-World Settings

Controlled studies and validation trials provide crucial data on the relative accuracy of different dietary assessment tools. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics reported in recent scientific literature.

Table 2: Comparative Accuracy and Performance Metrics of Dietary Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Study Design | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Strengths | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA24 | Extensive use in national surveillance (NHANES component via WWEIA) [38] [5] | Comparable error to interviewer-administered recalls when validated with recovery biomarkers [43] | High scalability, automated coding, free for researchers, extensive database [38] [43] | Usability issues for some populations, time-consuming, requires computer literacy [40] |

| DietAI24 | Evaluation on ASA24 and Nutrition5k datasets [39] | 63% reduction in MAE for food weight vs. existing methods; accurate estimation of 65 nutrients [39] | Handles real-world mixed dishes, no food-specific training required, high nutrient coverage [39] | Research framework, not yet a commercial product |

| Image-Based Tools (mFR, FoodView) | Controlled feeding studies & validation trials [43] [42] | More accurate than methods without images; better portion size estimation [43] | Reduces memory bias, provides visual documentation, user-friendly [43] [42] | Image quality dependency, limited adoption in research, potential user reactivity |

| Voice-based Recall (DataBoard) | Pilot study with older adults (n=20) [40] | Feasibility: 7.95/10; Acceptability: 7.6/10; Easier to use than ASA24 (6.7/10) [40] | Reduces digital literacy barriers, preferred by older adults [40] | Early development stage, limited validation, may struggle with complex food names |

Usability and Participant Burden

Usability is a critical factor influencing participant compliance and data quality, particularly in long-term studies.

Table 3: Usability and Practical Implementation Factors

| Tool | Target Population | Usability Metrics | Completion Time | Participant Preferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA24 | Ages 12+ with 5th-grade reading level [38] | Challenging for some older adults [40] | Not explicitly reported, but considered time-consuming [40] | Less preferred compared to voice-based methods in older adults [40] |

| NutriDiary | German adults (evaluation study) [44] | SUS Score: 75 (IQR 63-88) - indicates "good" usability [44] | Median 35 min (IQR 19-52) for one-day record [44] | Preferred over paper-based method by most participants [44] |

| Voice-based Recall | Older adults (65+) [40] | Rated easier than ASA24 (6.7/10) [40] | Not explicitly reported | Preferred for frequent use over ASA24 (7.2/10) [40] |

| Mobile Apps (General) | Adolescents [3] | Varied; influenced by design features like autofill and gamification [3] | Shorter recalls (2-4 hours) reduce burden [3] | Preference for apps over web-based tools [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Understanding the methodological details of key validation studies is essential for researchers to evaluate evidence quality and design their own trials.

Protocol 1: DietAI24 Validation Study

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of the DietAI24 framework in food recognition, portion size estimation, and nutrient content estimation from food images [39].

Methodology:

- Dataset: Used ASA24 and Nutrition5k datasets for evaluation [39].

- Indexing Phase: FNDDS database was segmented into concise, MLLM-readable food descriptions [39].

- Retrieval Phase: Implemented Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to ground MLLM responses in FNDDS database [39].

- Estimation Phase: Employed GPT Vision model for image-to-text reasoning and nutrient estimation [39].