Beyond the Questionnaire: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Food Frequency Questionnaire Limitations in Clinical Research

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) are indispensable yet imperfect tools for assessing dietary intake in large-scale epidemiological studies and clinical trials.

Beyond the Questionnaire: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Food Frequency Questionnaire Limitations in Clinical Research

Abstract

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) are indispensable yet imperfect tools for assessing dietary intake in large-scale epidemiological studies and clinical trials. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to navigate and mitigate the inherent limitations of FFQs. We explore the foundational sources of measurement error, detail advanced methodological adaptations for enhanced accuracy, present cutting-edge computational and machine learning techniques for optimization, and establish rigorous protocols for validation. By synthesizing current research and emerging methodologies, this guide aims to empower scientists to generate more reliable nutritional data, thereby strengthening the investigation of diet-disease relationships and the development of targeted nutritional interventions.

Understanding the Core Challenges: Why FFQs Fall Short and What It Means for Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of measurement error in self-reported dietary data? The main sources are recall bias, portion size estimation errors, and day-to-day variation in diet. Recall bias occurs when participants inaccurately remember their past food consumption, a particular issue with Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) that ask about intake over long periods [1]. Portion size estimation is a major cause of error, as individuals struggle to judge the quantities of food they consumed, with single-unit foods (e.g., a slice of bread) being reported more accurately than amorphous foods (e.g., pasta) or liquids [2]. Day-to-day variation is the natural fluctuation in a person's diet from one day to the next, which can introduce substantial random error if only a small number of days are assessed [3].

Q2: How does the error structure differ between a 24-Hour Recall (24HR) and an FFQ? Data from 24HRs typically contain larger within-person random error (due to day-to-day variation) but smaller systematic error [3]. In contrast, FFQs exhibit more systematic error, which is often driven by the cognitive challenge of recalling long-term intake and the instrument's design, such as its finite food list [3]. One study found that systematic error accounted for over 22% of measurement error variance for 24-hour recalls, but over 50% for the FFQ [4].

Q3: Can biomarkers help validate self-reported dietary intake? Yes, biomarkers are crucial for validation, but their utility depends on the type. Recovery biomarkers, like doubly labeled water for energy intake and urinary nitrogen for protein intake, are considered the strongest objective validators because they are not substantially affected by inter-individual differences in metabolism [3]. Concentration biomarkers, such as blood carotenoid levels for fruit and vegetable intake, are correlated with diet but are influenced by an individual's metabolism and other characteristics like smoking status or body size, making them less suitable as direct proxies for absolute intake [4] [1].

Q4: Which dietary assessment instrument provides less biased estimates of intake? Evidence from large biomarker-based validation studies suggests that 24-hour recalls provide less biased estimates of intake compared to FFQs and are thus the preferred tool for most purposes [3]. For example, one study reported the validity (correlation with true intake) of the instruments was 0.44 for 24-hour recalls and 0.39 for the FFQ [4].

Q5: How can portion size estimation errors be mitigated? Using Portion Size Estimation Aids (PSEAs) can help, though they do not eliminate error. Research compares text-based aids (using household measures and standard sizes) to image-based aids. One study found that although both methods introduced error, text-based descriptions (TB-PSE) showed better performance, with 50% of estimates falling within 25% of true intake, compared to 35% for image-based aids (IB-PSE) [2]. For 24-hour recalls, the use of pictorial recall aids has been shown to help participants remember omitted food items, significantly modifying dietary outcomes [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Recall Bias in FFQ Data

Background: Participants frequently misreport the frequency of food consumption when recalling intake over extended periods (e.g., the past year) [1]. This can be due to genuine memory limitations or social desirability bias, where individuals report what they believe the researcher wants to hear [6].

Solution: Implement a Machine Learning-Based Error Adjustment A novel method uses a supervised machine learning model to identify and correct for likely misreporting.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Gather data that includes FFQ responses and objective measures such as blood lipids (LDL, total cholesterol), blood glucose, body fat percentage, BMI, age, and sex [6].

- Define a "Healthy" Reference Group: Split your dataset. Use participants classified as "healthy" based on objective cut-offs for body fat, age, and sex to create a training set. This group is assumed to report their dietary intake more accurately [6].

- Train a Predictive Model: Use the healthy group's data to train a Random Forest (RF) classifier. The model learns to predict food frequency categories based on the objective variables (e.g., blood lipids, BMI) [6].

- Apply the Model and Adjust Data: Use the trained RF model to predict the expected food frequency categories for the remaining ("unhealthy") participants.

- For foods with a high likelihood of underreporting (e.g., high-fat foods like bacon), if the originally reported frequency is lower than the model's prediction, replace it with the predicted value [6].

- This method has demonstrated high model accuracies, ranging from 78% to 92%, in correcting underreported entries [6].

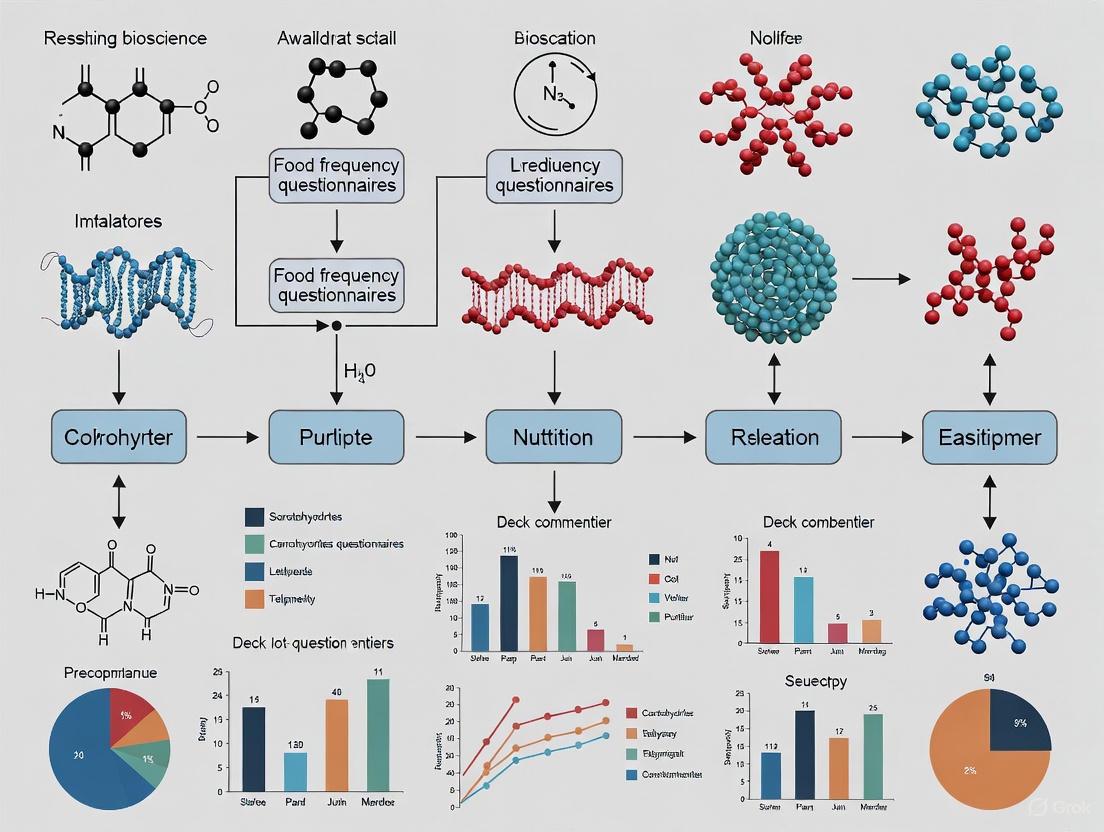

Workflow for Mitigating Recall Bias with Machine Learning:

Problem 2: Inaccurate Portion Size Estimation

Background: Individuals consistently struggle to estimate portion sizes, with a tendency to overestimate small portions and underestimate large ones (the "flat-slope phenomenon") [2]. The accuracy varies greatly by food type.

Solution: Optimize Portion Size Estimation Aids (PSEAs) Carefully select and design the aids used to help participants report quantities.

- Experimental Protocol for Comparing PSEAs:

- Control True Intake: In a study setting, provide participants with pre-weighed, ad libitum amounts of various food types (amorphous, liquids, single-units, spreads) [2].

- Measure Plate Waste: Weigh the leftovers to calculate the exact amount each participant consumed [2].

- Administer PSEAs: At set intervals (e.g., 2 and 24 hours after eating), have participants report their intake using different PSEAs in a randomized order. Key comparisons are:

- Analyze Accuracy: Compare reported portion sizes to true intake. Metrics include the median relative error, and the proportion of estimates within 10% and 25% of the true value [2].

Results to Inform Your Protocol: A study using this protocol found that text-based aids (TB-PSE) outperformed image-based aids (IB-PSE) [2].

Table 1. Accuracy of Portion Size Estimation Aids (PSEAs)

| Food Type | PSEA Method | Median Relative Error | Within 25% of True Intake |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Foods Combined | Text-Based (TB-PSE) | 0% | 50% |

| All Foods Combined | Image-Based (IB-PSE) | 6% | 35% |

| Single-unit foods | Both Methods | More Accurate | More Accurate |

| Amorphous foods & Liquids | Both Methods | Less Accurate | Less Accurate |

Recommendation: For web-based or paper tools, prioritize clear textual descriptions of portion sizes using standard household measures and predefined sizes. While image aids can be helpful, they should not be relied upon as the sole method [2].

Problem 3: Excessive Day-to-Day Variation Obscuring Usual Intake

Background: A single day of intake, as captured by one 24-hour recall, is a poor indicator of a person's habitual diet due to large daily fluctuations. Treating this as usual intake introduces significant random error (within-person variation) [3].

Solution: Administer Multiple Non-Consecutive 24-Hour Recalls The key is to spread assessments over time to capture this variation and statistically model the usual intake.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Plan Multiple Administrations: Do not collect recalls on consecutive days. Intakes on adjacent days are often correlated. Space them out over different seasons to account for seasonal variation [7].

- Include All Days of the Week: Ensure your recalls cover both weekdays and weekend days, as eating patterns often differ [7].

- Use Automated Tools: Leverage low-cost, automated self-administered 24HR tools (e.g., ASA24) to make multiple administrations feasible in large studies [3].

- Apply Statistical Modeling: Use specialized software (e.g., the National Cancer Institute's method) to estimate the distribution of usual intake in your population by separating within-person variation from between-person variation [3].

Evidence for Protocol Efficacy: Research comparing 3-day food records to 9-day records (as a reference) found that the 3-day records showed higher correlation and better agreement in quartile classification than an FFQ, demonstrating that multiple short-term records better capture habitual intake [7].

Workflow for Addressing Day-to-Day Variation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Dietary Validation and Error Mitigation Studies

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | A recovery biomarker used to measure total energy expenditure, providing an unbiased estimate of energy intake for validation studies [3]. |

| 24-Hour Urine Collection | Used to measure urinary nitrogen (a recovery biomarker for protein intake), potassium, and sodium, allowing for objective validation of self-reported intake of these nutrients [3]. |

| Blood Samples (Serum/Plasma) | Analyzed for concentration biomarkers, such as carotenoids (e.g., α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein), which serve as objective indicators of fruit and vegetable intake [4]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | The laboratory method used to separate and quantify specific carotenoids and other nutrient biomarkers in blood plasma with high precision [4]. |

| Automated Self-Administered 24-HR (ASA24) | A web-based tool that automates the 24-hour recall process, eliminating the need for an interviewer and reducing coding errors, making multiple administrations feasible [3]. |

| Portion Size Image Sets (e.g., from ASA24) | Standardized photographic aids used in image-based portion size estimation (IB-PSE) to help participants visualize and select the amount of food they consumed [2]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | A machine learning algorithm that can be trained to identify and correct for misreporting in FFQ data based on relationships with objective health measures [6]. |

| JW 618 | JW 618, CAS:1416133-88-4, MF:C17H14F6N2O2, MW:392.29 g/mol |

| 1,7-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)hept-6-en-3-one | 1,7-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)hept-6-en-3-one |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) Research

This support center provides targeted guidance for researchers encountering common methodological challenges in dietary assessment, with a specific focus on the localization and adaptation of Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I correct for underreporting of specific food items in my FFQ data? A machine learning-based error adjustment method can be applied. This involves using a Random Forest classifier trained on objectively measured health biomarkers (e.g., blood lipids, body fat percentage) from a "healthy" participant subgroup to predict likely consumption of underreported foods (e.g., high-fat items) in the rest of the cohort. If the model's prediction for an unhealthy food is higher than the participant's reported intake, the value is corrected [6].

What is the most effective way to adapt portion sizes in an FFQ for a new region? Conduct a local utensil survey. Systematically measure the volume of commonly used serving utensils (e.g., bowls, glasses) from a representative sample of households. Classify these into small, medium, and large portion sizes based on the derived volumes. Using these local sizes, instead of national reference portions, can prevent underestimation of food consumption by over 50% and significantly improves correlation with 24-hour recall data [8].

Our FFQ significantly misestimates macronutrient intake. How can we validate and improve it? Validate your FFQ against multiple 24-hour dietary recalls or, ideally, controlled feeding studies. One study feeding subjects diets of known composition found that an FFQ significantly underestimated absolute fat and protein intake and overestimated carbohydrate intake on a high-fat diet. If such miscalibration is found, the relationship between FFQ-reported values and actual intake can be quantified and used to create calibration factors [9].

What is the step-by-step process for translating and adapting an international FFQ? Follow a structured adaptation and validation protocol:

- Forward Translation: Translate the original FFQ into the local language.

- Local Food Inclusion: Add culturally relevant food items identified via market surveys and literature reviews.

- Back Translation: Have a different translator convert the local version back to the original language to check for conceptual consistency.

- Portion Size Standardization: Define portion sizes using local household measures and/or photographs.

- Pilot Testing: Test the draft FFQ in a small sample to identify difficulties in comprehension.

- Validation: Assess the final FFQ's validity against multiple 24-hour recalls or food records [10].

Experimental Protocols for FFQ Localization and Validation

Protocol 1: Local Portion Size Derivation

Objective: To define context-specific portion sizes for a semi-quantitative FFQ to mitigate measurement error.

Materials:

- Measuring scale and standard measuring cup (e.g., 240 mL)

- Digital weighing scale (accuracy 0.1 g) for solid foods

- Standardized spoons for liquid ingredients

Methodology:

- Utensil Survey: Randomly select households in the target region. Inventory and measure the dimensions and volumes of all commonly used serving utensils (SUs).

- Data Pooling: Pool the volume data from all collected SUs. Classify them into categories (e.g., small, medium, large) based on statistical frequency.

- Recipe Standardization: In a food lab, prepare common local dishes using recipes and ingredients reported in the survey.

- Weight Conversion: Weigh the total cooked dish. Determine the weight of the cooked dish that fits into the classified portion sizes (e.g., a "small" local bowl). This converts local portion sizes into gram weights for nutrient calculation [8].

Protocol 2: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of an FFQ

Objective: To adapt an existing FFQ to a new cultural setting and test its reproducibility and validity.

Materials:

- Original FFQ to be adapted

- Local food composition tables and databases (e.g., FAO, USDA, or national tables)

- 24-hour dietary recall forms

Methodology:

- Adaptation: Add traditional and commonly consumed local food items to the original FFQ list. Retain non-relevant items from the original FFQ for international comparability.

- Translation: Perform forward and backward translation following WHO Standard Operational Procedures.

- Study Design: Administer the following to participants:

- The adapted FFQ at time zero (FFQ1).

- Three 24-hour dietary recalls (including a weekend day) spread over one month.

- The same adapted FFQ one month later (FFQ2).

- Data Analysis:

- Validity: Calculate Pearson correlation coefficients between nutrient intakes from FFQ1 and the average of the three 24-hour recalls. Apply de-attenuation to correct for within-person variation [10].

- Reproducibility: Calculate the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) between nutrient intakes from FFQ1 and FFQ2 [10].

Summarized Quantitative Data from FFQ Validation Studies

Table 1: Correlation Coefficients from an FFQ Adaptation Study in Moroccan Adults [10]

| Nutrient | Validity (De-attenuated Correlation with 24-hr Recall) | Reproducibility (Intra-class Correlation) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | 0.51 | 0.76 |

| Fat | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| Protein | 0.58 | 0.78 |

| Carbohydrates | 0.46 | 0.75 |

| Total MUFA | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| Fiber | 0.24 | 0.76 |

| Vitamin A | 0.67 | 0.84 |

Table 2: Impact of Local vs. Reference Portion Sizes on Food Estimation [8]

| Metric | Result from Indian Rural Study |

|---|---|

| Potential Underestimation using Reference Portions | 55-60% of actual food consumed |

| Correlation with 24-hr Recall | Better with locally derived portion sizes |

Workflow Diagrams for FFQ Adaptation

Diagram Title: FFQ Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process

Diagram Title: Machine Learning Workflow for Underreporting Correction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for FFQ Studies

| Item | Function / Application in FFQ Research |

|---|---|

| Standardized Measuring Utensils | Critical for conducting local utensil surveys to derive accurate portion sizes for converting food frequencies into gram weights [8]. |

| Digital Food Scales | Required for weighing raw ingredients and cooked dishes in a lab setting to determine the weight of food corresponding to local portion sizes [8]. |

| Local & International Food Composition Tables | Databases (e.g., USDA, FAO, CIQUAL, national tables) used to assign nutrient values to the food items and portion sizes listed in the adapted FFQ [10]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall Forms | The standard tool used as a reference method to validate the nutrient intake estimates generated by the new FFQ [10]. |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Kits for analyzing objective measures like blood lipids (LDL, total cholesterol) and glucose. Used to identify reporting biases and train error-correction models [6]. |

| Block 2005 FFQ / GA2LEN FFQ | Examples of established, pre-defined FFQs that can serve as a starting framework for cultural adaptation and localization [6] [10]. |

| Exendin 3 | Exendin 3, CAS:130391-54-7, MF:C184H282N50O61S, MW:4203 g/mol |

| Desethyl Terbuthylazine-d9 | Desethyl Terbuthylazine-d9, CAS:1219798-52-3, MF:C7H12ClN5, MW:210.71 g/mol |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Methodological Challenges

Q1: Why is the traditional focus on single nutrients insufficient for modern nutritional research?

Traditional methods that analyze foods and nutrients in isolation overlook crucial food synergies, which can lead to an incomplete understanding of dietary patterns and their health implications. For example, a study found that garlic may counteract some of the detrimental effects associated with red meat consumption, a synergy that would be missed by examining nutrients alone [11]. Furthermore, studies focusing on individual nutrients like magnesium, potassium, calcium, and fiber have produced inconsistent results, potentially because nutrients from supplements may not benefit health as effectively as those obtained from whole foods due to synergistic interactions [11].

Q2: What are the primary limitations of traditional dietary pattern analysis methods like PCA or cluster analysis?

Methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis share a significant limitation: they are often unable to fully capture the complex interactions and synergies between different dietary components [11]. By reducing dietary intake to composite scores or broad patterns, they disregard the multidimensional nature of diet and can hide crucial food synergies [11]. These methods often assume that dietary patterns are relatively static, ignoring potential changes in diet over time due to ageing, economic changes, or health conditions, which can result in obscured or false associations [11].

Q3: How can measurement error in Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) be mitigated?

FFQs are susceptible to errors like underreporting, particularly for unhealthy foods. A novel approach uses a supervised machine learning method involving a Random Forest (RF) classifier to identify and correct for these errors [6]. The protocol involves:

- Splitting the dataset into groups (e.g., based on health status using objective measures like body fat percentage).

- Training the RF model on data from the "healthy" group to learn the relationship between objective biomarkers (e.g., LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol) and food consumption.

- Predicting and correcting values in the "unhealthy" group. If the originally reported value for an unhealthy food is lower than the model's prediction, it is considered underreported and replaced with the predicted value [6].

Q4: What is the evidence that overall dietary patterns are linked to long-term health outcomes?

Large prospective cohort studies provide strong evidence. Research from the Nurses' Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (following 105,015 participants for up to 30 years) found that greater adherence to healthy dietary patterns was consistently associated with higher odds of "healthy aging" [12]. Healthy aging was defined as surviving to 70 years free of major chronic diseases and maintaining intact cognitive, physical, and mental health. The study showed that for each dietary pattern, the highest adherence was associated with 1.45 to 1.86 times greater odds of healthy aging compared to the lowest adherence [12].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Research Problems

Problem: Inability to Model Complex, Non-Linear Food Interactions

- Challenge: Traditional statistical models assume simple, linear relationships and fail to capture the complex, non-linear web of how foods interact and are consumed together.

- Solution: Employ Network Analysis, such as Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs).

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Collect high-dimensional dietary intake data (e.g., from multiple 24-hour recalls or a validated FFQ).

- Model Selection: Apply a Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM). GGMs use partial correlations to identify conditional dependencies between foods, revealing how foods are directly connected after accounting for all other foods in the network [11].

- Regularization: Use regularization techniques like the graphical LASSO to handle high-dimensional data and produce a sparse, interpretable network [11].

- Validation & Interpretation: Visualize the network. Nodes represent foods, and edges represent conditional dependencies. Centrality metrics can identify key foods, but these must be interpreted with caution due to known limitations [11].

Problem: Balancing Multiple, Sometimes Conflicting, Research Objectives

- Challenge: Designing a diet that simultaneously optimizes for nutrient adequacy, environmental sustainability (e.g., low greenhouse gas emissions), and other dimensions like food biodiversity.

- Solution: Implement Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO).

- Experimental Protocol:

- Define Objectives: Clearly state the goals (e.g., maximize nutrient adequacy score, minimize dietary greenhouse gas emissions).

- Set Constraints: Define nutritional and practical constraints (e.g., meet recommended dietary allowances for all essential nutrients).

- Model Application: Use MOO algorithms to generate a spectrum of optimal diets that represent the best trade-offs between the chosen objectives. This approach was successfully applied in the EPIC cohort to show that diets adhering to the EAT-Lancet recommendations, with higher biodiversity and lower ultra-processed foods, can synergistically improve nutrient adequacy while reducing environmental impact [13] [14].

Problem: Validating FFQ Data Against Objective Measures

- Challenge: Self-reported FFQ data may not accurately reflect true biological intake, especially in specific disease populations.

- Solution: Biochemical validation using serum or urine biomarkers.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Cohort and Sample Collection: Recruit participants from your target population. Collect dietary data via FFQ and concurrently collect fasting blood or 24-hour urine samples [15] [16].

- Biomarker Analysis: Measure biomarkers relevant to the nutrients of interest (e.g., serum vitamins A, C, D, E, zinc, iron) [16].

- Statistical Comparison: Assess agreement between FFQ-derived intake and biomarker levels using correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson or Spearman) and cross-classification into quartiles [15] [16]. Note that poor agreement may indicate issues with the FFQ or reflect altered nutrient metabolism in the study population [16].

Key Experimental Protocols in Detail

Protocol 1: Validating a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)

This protocol is based on the methodology used by the large PERSIAN Cohort validation study [15].

- Aim: To assess the validity and reproducibility of an FFQ for ranking individuals based on their nutrient intakes.

- Materials:

- Designed FFQ (e.g., 113-item, semi-quantitative)

- Standard portion size tools (food models, utensils, picture album)

- Biological sample collection kits (for serum and 24-hour urine)

- Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment (Day 0):

- Administer the first FFQ (FFQ1) via a trained interviewer.

- Collect baseline fasting blood and 24-hour urine samples.

- Longitudinal Data Collection (Months 1-12):

- Conduct two non-consecutive 24-hour dietary recalls (24HR) each month (total of 24 recalls) as a reference method.

- Collect fasting blood and 24-hour urine samples each season (total of 4 collections).

- Follow-up Assessment (Month 12):

- Administer the FFQ a second time (FFQ2) to assess reproducibility.

- Baseline Assessment (Day 0):

- Data Analysis:

- Validity: Calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson) between nutrient intakes from FFQ1 and the average of the 24HRs.

- Reproducibility: Calculate correlation coefficients between nutrient intakes from FFQ1 and FFQ2.

- Biomarker Comparison: Use the triad method to compare correlations between the FFQ, 24HR, and biomarker levels [15].

Protocol 2: Applying Network Analysis to Dietary Data

This protocol outlines the use of Gaussian Graphical Models to uncover dietary patterns [11].

- Aim: To map and analyze the complex web of conditional dependencies between different dietary components in a population.

- Materials:

- High-dimensional dietary intake dataset (e.g., food items or food groups).

- Statistical software capable of network estimation (e.g., R with

qgraphorhugepackages).

- Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Address non-normal data distribution through transformations (e.g., log-transformation) or by using non-parametric extensions of GGMs [11].

- Model Estimation: Apply the graphical LASSO to estimate the GGM. This technique uses an L1-penalty to shrink small partial correlations to zero, resulting in a sparse and interpretable network [11].

- Network Visualization: Create a network graph where nodes are foods and edges represent significant partial correlations. Visually inspect the network for clusters of strongly connected foods.

- Robustness Analysis: Check the stability of the network structure using methods like bootstrapping.

- Interpretation: Identify central food items that may play a key role in the dietary pattern. However, the review notes that 72% of studies employing centrality metrics did not acknowledge their limitations, so conclusions should be drawn cautiously [11].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Dietary Pattern Research

The following table details key tools and databases essential for conducting high-quality research in this field.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) [17] | Provides the energy and nutrient values for foods and beverages reported in dietary surveys. | Contains data for energy and 64 nutrients for ~7,000 foods; essential for nutrient analysis in studies like What We Eat in America (WWEIA), NHANES [17]. |

| Food Pattern Equivalents Database (FPED) [17] | Converts foods and beverages into USDA Food Patterns components (e.g., cup equivalents of fruits, ounce equivalents of whole grains). | Used to examine food group intakes and assess adherence to Dietary Guidelines recommendations; crucial for dietary pattern analysis [17]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24HR) [15] [17] | A reference method for dietary assessment that captures detailed intake over the previous 24 hours. | Uses multiple-pass method to enhance accuracy; less prone to systematic error than FFQs; used for validation and in NHANES [15] [17]. |

| Biomarkers (Serum/Urine) [15] [16] | Objective biological measures used to validate self-reported dietary intake. | Examples: serum folate, fatty acids, urinary nitrogen and sodium. Provide an objective measure to triangulate with FFQ and 24HR data [15] [16]. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) Algorithms [13] | Computational tools to simultaneously optimize multiple, competing objectives (e.g., nutrient adequacy and environmental sustainability). | Generates a spectrum of optimal trade-offs; identifies synergies between dietary dimensions without requiring a priori decisions on their relative importance [13]. |

Conceptual Diagrams

From Data to Dietary Patterns: An Analytical Workflow

This diagram visualizes the pathway from raw dietary data to the identification and interpretation of complex dietary patterns, integrating key methodologies discussed in the FAQs and protocols.

The Synergistic Relationship of Key Dietary Dimensions

This diagram illustrates the interconnected relationship between three critical dimensions of a sustainable and healthy diet, as identified by multi-objective optimization research.

FAQ: Understanding FFQ Limitations and Their Impact on Research

Q1: What are the primary types of measurement error introduced by FFQs?

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) are susceptible to several measurement errors that can distort diet-disease relationships. The main types of error include:

- Recall Bias: Participants inaccurately remember the type or frequency of foods consumed over a long period (e.g., the past year) [18] [19].

- Systematic Bias: This includes under-reporting of foods perceived as "unhealthy" (e.g., high-fat foods like bacon and fried chicken) and over-reporting of foods perceived as "healthy" [20] [6] [19]. This is also known as social desirability bias.

- Misclassification: The structure of FFQs, which often group foods and use fixed portion sizes, can lead to incorrect categorization of individuals' true usual intake. This is particularly problematic for ranking subjects in epidemiological studies [18] [19].

Q2: How do these errors ultimately affect the analysis of diet-disease relationships?

These errors do not just add noise; they introduce bias that can obscure or distort true relationships. The primary consequences are:

- Attenuation of Risk Estimates: Correlation coefficients and relative risks (e.g., Hazard Ratios) are biased towards the null value, making real associations between diet and disease appear weaker than they truly are [21] [22].

- Loss of Statistical Power: The increased variability from measurement error makes it more difficult to detect statistically significant associations, potentially causing important findings to be missed [19].

- Erroneous Conclusions: In severe cases, the combined effect of attenuation and misclassification can lead to completely false conclusions about the presence or absence of a relationship [18].

Q3: Aren't biomarkers the ultimate solution for validating FFQ data?

Biomarkers are a powerful tool but are not a perfect gold standard. Their utility varies greatly:

- High-Valued Correlations: Some biomarkers show strong correlations with intake. For example, adipose tissue levels of linoleic acid (18:2 ω-6) correlated at 0.72 with dietary intake, and urinary 1-methyl-histidine for meat consumption correlated at 0.69 [21].

- Moderate to Low-Valued Correlations: Many other biomarkers, such as those for certain vitamins and carotenoids, show only moderate (0.30-0.49) or poor correlations with FFQ-reported intake [21] [16].

- Inherent Limitations: Biomarkers are influenced by individual differences in absorption, metabolism, and homeostatic regulation, meaning their levels cannot always be directly translated into absolute dietary intake [18] [21]. A study on patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) found poor agreement between FFQ-reported intake and serum levels of vitamins A, C, D, E, zinc, and iron, suggesting disease-specific physiology can further decouple intake from biomarker levels [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating Specific FFQ Issues

Table 1: Common FFQ Issues and Direct Mitigation Strategies

| Problem | Impact on Data | Recommended Mitigation Strategy | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-Reporting of Unhealthy Foods | Attenuates positive associations with disease risk (e.g., saturated fat and heart disease). | Machine Learning Reclassification: Use objective measures (LDL, BMI, body fat %) to train a model (e.g., Random Forest) to identify and correct implausible responses [20] [6]. | Requires a subset of participants with objective biomarker and anthropometric data. Model accuracy demonstrated from 78% to 92% [6]. |

| Inability to Capture Usual Intake | High day-to-day variation obscures long-term exposure. | Combine Instruments: Use the FFQ to rank individuals, but calibrate using multiple 24-Hour Recalls (24HR) in a subset [18] [22]. | 24HRs are considered less biased but require multiple (non-consecutive) administrations to estimate usual intake [19] [22]. |

| Systematic Bias (Social Desirability) | Overall energy and nutrient intake is under-reported. | Biomarker-Guided Regression Calibration: Use recovery biomarkers (energy, protein) to correct for systematic bias in reported intake [21] [22]. | Recovery biomarkers exist only for energy, protein, potassium, and sodium. They are expensive to measure [19] [22]. |

| Use of Generic Food Composition Databases | Inaccurate nutrient assignment, especially across different cultures and food varieties. | Leverage Specialized Databases: Use targeted databases (e.g., FAO/INFOODS for regional, biodiversity, or pulses data) to improve nutrient estimation [23] [24]. | Nutrient content can vary up to 1000-fold among varieties of the same food, making database specificity critical [24]. |

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Correcting Under-Reporting

This protocol is based on a published method that uses a Random Forest (RF) classifier to mitigate under-reporting of specific food items [20] [6].

1. Objective: To correct for under-reported entries of specific foods (e.g., high-fat items) in an FFQ dataset. 2. Materials and Input Data:

- FFQ Data: The complete dataset, including the specific food items to be corrected.

- Objective Covariates: Data with low measurement error, such as:

- Blood biomarkers (LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, blood glucose)

- Anthropometric measures (Body Mass Index, body fat percentage from DXA)

- Demographics (age, sex) 3. Procedure:

- Step 1 - Data Segmentation: Split the dataset into a "Healthy" group and an "Unhealthy" group based on objective health risk cut-offs (e.g., body fat percentage, age, and sex) [6]. The underlying assumption is that the "Healthy" group is more likely to report their intake accurately.

- Step 2 - Model Training: Train a Random Forest classification model using the "Healthy" group data. The model learns the relationship between the objective covariates (e.g., LDL, BMI) and the FFQ responses for the target foods.

- Step 3 - Prediction and Adjustment: Apply the trained model to the "Unhealthy" group to predict their expected (and likely more accurate) food intake category.

- Adjustment Rule: For an unhealthy food item, if the originally reported FFQ value is lower than the model's predicted value, replace the original value with the predicted value. The reported value is kept unchanged if it is higher than the prediction [6].

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Protocol 2: Biomarker-Guided Regression Calibration

This statistical protocol uses biomarkers to correct measurement error in diet-disease risk models [21].

1. Objective: To correct the regression coefficient (β) for a dietary variable in a disease risk model, reducing attenuation caused by FFQ measurement error. 2. Materials:

- Primary Study Data: FFQ (Q) and disease outcome data for the entire cohort.

- Calibration Substudy Data: A representative sample from the cohort with data from:

- Two different dietary biomarkers (M1, M2) of the nutrient of interest.

- The FFQ (Q). 3. Key Assumptions: Errors in the two biomarkers are independent of each other and independent of errors in the FFQ. Using long half-life biomarkers (e.g., adipose tissue for fatty acids) helps meet these assumptions [21]. 4. Procedure:

- Step 1: In the calibration subsample, perform a regression of the first biomarker (M1) on the FFQ (Q) and the second biomarker (M2). The second biomarker acts as a surrogate for true intake to account for the error in M1.

- Step 2: Use the regression parameters from Step 1 to predict the expected value of the biomarker M1 (which is a proxy for true intake) for everyone in the main cohort.

- Step 3: In the disease risk model for the full cohort, replace the error-prone FFQ values (Q) with the predicted values from Step 2. The resulting regression coefficient for the dietary variable is the error-corrected estimate.

The logical relationship for selecting a calibration method is shown below:

| Category | Resource / Reagent | Function in Research | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Dietary Instruments | 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | Serves as a less-biased reference method to validate or calibrate FFQ data. Can be interviewer-administered or automated (e.g., ASA-24) [18] [22]. | The Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) used in NHANES is a standardized approach [18]. |

| Objective Biomarkers | Recovery Biomarkers | Provide an unbiased estimate of true intake for a few specific nutrients. Used to quantify and correct for systematic bias in self-reports [19] [22]. | Only available for energy (doubly labeled water), protein (urinary nitrogen), potassium, and sodium (urinary excretion) [19]. |

| Concentration Biomarkers | Act as objective indicators of intake or exposure for a wider range of nutrients, though influenced by metabolism [21]. | Adipose tissue fatty acids, serum carotenoids, urinary isoflavones [21]. Correlations with intake can vary from poor to high. | |

| Food Composition Data | FAO/INFOODS Databases | Provide region-specific and food-specific nutrient data crucial for accurately converting food intake to nutrient values [23] [24]. | Examples include the Global Food Composition Database for Fish and Shellfish (uFiSh1.0) and the database for Biodiversity (BioFoodComp4.0) [23]. |

| Statistical & Computational Tools | Regression Calibration | A standard statistical method to correct attenuation bias in relative risks using data from a calibration study [21] [6]. | Can be implemented using standard statistical software (e.g., R, SAS). |

| Machine Learning Classifiers (Random Forest) | A modern computational approach to identify and correct for misreporting (under/over) in categorical FFQ data [20] [6]. | Demonstrated to operate independently of specific diet-disease models, reducing noise in the FFQ data itself [6]. |

Building Better Tools: Methodological Innovations for Robust FFQ Design

Technical Support Center: Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How do we create a food list that is representative of our specific study population?

Creating a representative food list is the most critical step in developing a culturally valid FFQ. The process must be systematic and evidence-based.

Recommended Protocol:

- Conduct a Preliminary Dietary Survey: Use open-ended methods like 24-hour dietary recalls or food records within your target population to identify commonly consumed foods [18].

- Review Existing Cultural Resources: Consult local cookbooks, market surveys, and previously published dietary studies in your region to compile a comprehensive list of traditional and popular dishes [25].

- Engage Local Experts: Form a panel of local nutrition professionals to review the draft food list for cultural relevance, religious dietary laws (e.g., Halal), and commonality of food items [25].

- Perform Market Research: Visit local supermarkets and community food stores to verify the availability of processed and branded food items, ensuring the list reflects what is actually consumed [25].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your population is multi-ethnic, ensure the food list captures the unique dietary habits of all major ethnic groups to avoid measurement error and misclassification.

FAQ 2: What is the best way to validate our newly developed or adapted FFQ?

Validation is essential to confirm that your FFQ accurately measures what it is intended to measure. The choice of a reference method is key.

Recommended Protocol: The standard approach involves comparing nutrient or food group intake estimates from your FFQ against a more precise reference method. The table below summarizes validation metrics from recent case studies.

Troubleshooting Tip: Always assess both validity (comparison against a reference method) and reliability (test-retest reproducibility) to ensure your FFQ is both accurate and consistent.

Table 1: Validation Metrics from Recent FFQ Adaptation Studies

| Country / Region | Reference Method Used | Key Statistical Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oman | Test-Retest Reliability | Weighted Kappa (frequency): 0.38 - 0.60; Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs): 0.57 - 0.80 | [25] |

| Italy (Adolescents) | 3-Day Food Diary | Adjusted Spearman Correlations: Legumes/Vegetables (>0.5), Meat/Fruits (>0.4), Fish/Bread (variable, improved with age stratification) | [26] |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 4x Food Records + Digital Images | Correlation Coefficients for Nutrients: Carbohydrates (r=0.83), Vitamin C (r=0.59); Cross-classification agreement for fiber/Vitamin A: 89% | [27] |

FAQ 3: Our FFQ data seems to have a high degree of under-reporting, particularly for unhealthy foods. How can we mitigate this?

Under-reporting of energy-dense or "unhealthy" foods is a common form of measurement error in self-reported dietary data [6].

- Recommended Protocol: A Machine Learning Adjustment Workflow A novel method to correct for this bias uses a supervised machine learning model, such as a Random Forest (RF) classifier, to identify and adjust likely under-reported entries [6]. The workflow is as follows:

- Troubleshooting Tip: This method requires a dataset that includes both FFQ responses and objective health biomarkers (e.g., blood lipids, body fat percentage) to function effectively [6].

FAQ 4: How can we effectively incorporate portion size estimation without over-burdening respondents?

The ability of respondents to accurately assess portion sizes is often limited. The choice between a qualitative and semi-quantitative FFQ must be deliberate.

Recommended Protocol:

- Use Visual Aids: Provide photographs of different portion sizes (small, medium, large) for common foods and dishes to help respondents estimate quantities [26] [28].

- Standardized Frequency Factors: For a semi-quantitative FFQ, use pre-defined standard portion sizes. For example, one serving of fruit could be defined as "one medium apple or a half-cup of chopped fruit" [29].

- Pilot Testing: Conduct a pilot study to test the clarity and usability of your portion size questions and visual aids with a small sample from your target population [30].

Troubleshooting Tip: For large epidemiological studies where ranking individuals by intake is the primary goal, a qualitative FFQ (without portion sizes) can be sufficient and significantly reduces participant burden [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for FFQ Adaptation and Validation

| Item Name / Concept | Function / Application in FFQ Research |

|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | An open-ended interview used as a reference method for validation studies. It collects detailed intake data over the previous 24 hours and is used to check the accuracy of the FFQ [18] [28]. |

| Food Composition Table/Database | A software or data table that links each food item on the FFQ to its nutrient content. It is essential for converting frequency data into estimates of nutrient intake [26] [31]. |

| Statistical Validation Metrics | A suite of statistical tests (Correlation Coefficients, Kappa statistics, Intraclass Correlation Coefficients - ICCs) used to quantitatively assess the agreement between the FFQ and the reference method [25] [26] [27]. |

| Digital Data Collection Platform | Tools like REDCap, Google Forms, or other web-based platforms used to administer the FFQ electronically. This reduces data entry errors, facilitates data collection from diverse locations, and can improve data quality [27] [31]. |

| Block 2005 / DHQ II / EPIC COS FFQ | Examples of well-established, pre-validated FFQs that are often used as a starting point or template for cultural adaptation, saving development time and resources [25] [26] [6]. |

| Octadeca-9,17-diene-12,14-diyne-1,11,16-triol | Octadeca-9,17-diene-12,14-diyne-1,11,16-triol, CAS:211238-60-7, MF:C18H26O3, MW:290.4 g/mol |

| Ribociclib D6 | Ribociclib D6, MF:C23H30N8O, MW:440.6 g/mol |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive FFQ Validation Study Design

This protocol outlines the steps for a robust validation study, as implemented in the Italian and Caribbean case studies [26] [27].

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit a convenience sample of at least 100-200 participants from the target population. The sample should reflect the age, sex, and ethnic diversity of the larger study cohort [26] [30].

- FFQ Administration: Administer the new FFQ to all participants. The FFQ should be designed to assess habitual dietary intake over the previous year [26] [28].

- Reference Method Administration:

- Test-Retest Reliability: Re-administer the FFQ to the same participants after a suitable interval (e.g., 3-10 months) to assess its reproducibility over time [27] [30].

- Data Analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients, cross-classification tables, and measures of agreement (e.g., ICCs) to compare the intake of nutrients and food groups derived from the FFQ with those from the reference method.

Protocol 2: Cultural Adaptation of an Existing FFQ

This protocol is based on the successful development of the Omani FFQ (OFFQ) [25].

- Selection of a Base FFQ: Choose a well-validated, comprehensive FFQ from the literature (e.g., the Diet History Questionnaire II from the US National Cancer Institute) [25].

- Initial Item Review: Have nutrition experts independently review each food item on the base FFQ for cultural and religious relevance to the new population. Remove, modify, or add items as needed.

- Translation: Translate the modified FFQ into the target language. Perform a back-translation into the original language to ensure conceptual and linguistic accuracy [25] [32].

- Pilot Testing and Refinement: Administer the translated FFQ to a small sample from the target population. Use qualitative feedback to identify confusing items, portion size estimations, or missing foods. Refine the questionnaire accordingly.

- Formal Validation: Subject the final adapted FFQ to a formal validation study, as detailed in Protocol 1.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common methodological challenges researchers face when developing and validating targeted Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs).

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I overcome the low accuracy of FFQs for sporadically consumed foods, such as many fermented products?

A: This is a recognized limitation when using generic FFQs. The solution is to develop a targeted FFQ that uses specific, culturally relevant examples and visual aids.

- Recommended Protocol: Develop a food-specific FFQ, like the Fermented Food Frequency Questionnaire (3FQ). The 3FQ stratifies foods into 16 major groups and uses validated food pictures (a "food atlas") to help participants identify and quantify their usual portions. For fermented foods, it further breaks down categories into specific, common examples (e.g., under "hard cheese," listing Parmigiano for Italy and Graviera for Greece) to trigger more accurate recall [33] [34].

Q2: What is the best way to classify ultra-processed foods (UPFs) when the NOVA system has known limitations?

A: A critical reassessment and modification of the NOVA system is recommended. One effective approach is to combine the level of processing with nutritional profile data.

- Recommended Protocol: Develop a modified NOVA (mNOVA) classification. In this system, processed foods (Group 3) and UPFs (Group 4) are subdivided based on thresholds for salt, sugar, and fat as recommended by the Food Standard Agency (FSA). This creates subgroups (e.g., 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b) and adds a nutritional dimension to the purely processing-based classification, leading to a more precise categorization of foods [30].

Q3: How can I correct for measurement errors, such as underreporting of unhealthy foods, in my FFQ data?

A: Supervised machine learning methods can be employed to identify and adjust for systematic reporting errors.

- Recommended Protocol: Use a Random Forest (RF) classifier. This method uses objectively measured variables (e.g., blood lipids, BMI, age, sex) from a subset of "healthy" participants to train a model that predicts food intake. This model is then applied to the wider dataset. If a participant's reported intake of an unhealthy food is lower than the model's prediction, the value is adjusted upward to correct for probable underreporting [6].

Q4: How do I validate a new targeted FFQ to ensure its reliability for population studies?

A: A robust validation study must assess both reproducibility (repeatability) and criterion validity (accuracy).

- Recommended Protocol:

- Reproducibility: Administer the FFQ twice to the same participants at a predefined interval (e.g., 6 weeks to 10 months). Calculate Intra-Class Correlation (ICC) coefficients to measure test-retest reliability [30] [33].

- Criterion Validity: Compare intake data from the FFQ against a reference method, such as multiple 24-hour dietary recalls or a weighed dietary record, collected from the same participants. Use Spearman's correlation coefficients and Bland-Altman plots to assess the level of agreement between the two methods [30] [7] [33].

Q5: What are the key considerations for designing an FFQ for multi-country or multi-ethnic cohorts?

A: Cross-cultural adaptability is paramount. The tool must capture region-specific foods and consumption habits without sacrificing data comparability.

- Recommended Protocol:

- Develop a Universal Core: Create a base FFQ in a common language (e.g., English) with broad food groups.

- Localize with Examples: Populate these groups with country-specific food examples (e.g., different types of fermented vegetables or cheeses).

- Standardize Translation: Use a back-translation method to ensure conceptual equivalence across different language versions.

- Use Visual Aids: Employ picture atlases with standardized portion sizes to overcome language and educational barriers [34] [35].

Summarized Quantitative Data from Validation Studies

The table below summarizes key metrics from recent validation studies for targeted FFQs, providing benchmarks for researchers.

Table 1: Validation Metrics for Targeted Food Frequency Questionnaires

| FFQ Focus & Study | Validation Measure | Results / Correlation Coefficients | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Food Groups [35] | Validity (FFQ vs. 24-hr Recall) | Weakest: Fresh Juice, Other Meats (0.23-0.32)Moderate: Red Meat, Chicken, Eggs (0.42-0.59)Strongest: Tea, Sugars, Grains, Fats/Oils (0.60-0.79) | The FFQ is appropriate for ranking individuals by intake of most food groups. |

| PERSIAN Cohort FFQ [35] | Reproducibility (FFQ1 vs. FFQ2) | Range: 0.42 (Legumes) to 0.72 (Sugar & Sweetened Drinks) | Showed moderate to strong reproducibility for all food groups over a 12-month interval. |

| Fermented Foods (3FQ) [33] | Repeatability (ICC) | Most Groups: 0.4 to 1.0Infrequent Items: Lower (e.g., Fermented Fish) | High repeatability for most fermented food groups, with challenges for rarely consumed items. |

| Fermented Foods (3FQ) [33] | Validity (vs. 24-hr Recall) | Agreement within Intervals: >90% for most groupsStrongest Agreement: >95% for Dairy, Coffee, Bread | Excellent agreement with 24-hour recalls for frequently consumed fermented foods. |

| 3-day Food Records [7] | Validity (vs. 9-day Records) | Pearson's Correlation Range: 0.14 to 0.56 | 3-day records showed higher correlations with reference method than the FFQ did. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Validating a Targeted FFQ for Ultra-Processed Foods

This protocol is adapted from a study designed to develop and validate a UPF-focused FFQ for the Italian population [30].

1. Study Design:

- A two-phase, multicenter study.

- Phase 1 (Pilot): Investigate current food consumption via 24-hour dietary recalls and test the face validity of the draft FFQ (n=20-50).

- Phase 2 (Validation): Assess criterion validity and reproducibility in a larger sample (n≥436).

2. Population:

- Recruit healthy adults (≥18 years) from workplaces/universities.

- Exclude individuals with chronic diseases, restrictive diets, or who are pregnant/lactating.

3. Dietary Assessment:

- FFQ Administration: A self-administered, semi-quantitative FFQ designed to distinguish between industrial, artisanal, and home-made products.

- Reference Method: Participants complete a 7-day weighed dietary record (WDR) after each FFQ administration.

- Reproducibility: Administer the FFQ twice, with an interval of 3-10 months (test-retest).

4. Data Analysis:

- Criterion Validity: Compare nutrient and UPF intake data from the first FFQ against the two WDRs.

- Reproducibility: Compare UPF intake data from the first and second FFQ administrations.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Adjustment for FFQ Underreporting

This protocol outlines the method for using a Random Forest classifier to correct measurement error [6].

1. Data Preparation:

- Obtain a dataset containing FFQ responses, demographic data (age, sex), and objective clinical biomarkers (LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, blood glucose, body fat percentage, BMI).

2. Classifier Training:

- Split the dataset into "Healthy" and "Unhealthy" groups based on clinical cut-offs for biomarkers.

- Use the data from the "Healthy" group to train a Random Forest model. The model learns the relationship between the objective biomarkers (input features) and the FFQ responses (output labels).

3. Error Adjustment Algorithm:

- Apply the trained model to the "Unhealthy" group to predict their expected FFQ responses based on their biomarkers.

- Compare the model's prediction to the participant's actual self-reported intake.

- For unhealthy foods (e.g., bacon, fried chicken): If the self-reported value is lower than the predicted value, replace it with the predicted value to correct for underreporting.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

FFQ Development and Validation Workflow

Machine Learning Error Correction Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item / Resource | Function & Application in FFQ Research |

|---|---|

| Validated Food Atlas / Portion Size Pictures | Visual aids to improve the accuracy of portion size estimation by participants. Crucial for cross-cultural studies and for quantifying fermented foods and ready-to-eat UPFs [33] [35]. |

| Modified NOVA (mNOVA) Classification | A food classification system that combines processing level with nutritional thresholds (e.g., for fat, sugar, salt). Provides a more precise tool for categorizing and analyzing UPF intake than NOVA alone [30]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24-hr) | A short-term dietary assessment method used as a "gold standard" reference to validate the criterion validity of a new FFQ. Multiple recalls are needed to account for day-to-day variation [30] [7] [33]. |

| Weighed Dietary Record (WDR) | Another reference method where participants weigh and record all consumed foods and beverages. Provides highly detailed intake data for validation studies but is burdensome for participants [30]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | A supervised machine learning algorithm used to identify and correct for systematic reporting errors (e.g., underreporting of unhealthy foods) in existing FFQ datasets [6]. |

| Harvard FFQ & Nutrient Database | A well-established, extensively validated semi-quantitative FFQ and database. Serves as a strong methodological foundation and can be adapted for developing new targeted questionnaires [31]. |

| Clinical Biomarkers | Objective measures (e.g., blood lipids, blood glucose, BMI) used to train machine learning models for error correction or to provide ancillary validation of FFQ-derived dietary patterns [6]. |

| NOS1-IN-1 | NOS1-IN-1, CAS:357965-99-2, MF:C14H24F9N7O8, MW:589.37 g/mol |

| rac-2-Aminobutyric Acid-d3 | rac-2-Aminobutyric Acid-d3, CAS:1219373-19-9, MF:C4H9NO2, MW:106.14 g/mol |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical and methodological challenges researchers face when implementing web-based and electronic Food Frequency Questionnaires (e-FFQs).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our study population has diverse dietary cultures. How can we ensure the e-FFQ accurately captures all relevant foods?

A: Implement a data-driven, culturally-specific development process. This involves:

- Preliminary Dietary Data Collection: Use 24-hour dietary recalls from your target population to identify commonly consumed foods [36] [37].

- Statistical Selection: Employ stepwise regression analysis on the recall data to identify the foods that contribute most significantly (>90%) to the variance in intake of key energy and nutrients [36].

- Include Local and Street Foods: Actively add culturally specific dishes and street foods to the food list, as demonstrated in the Trinidad and Tobago e-FFQ, which included 14 such items [37].

Q2: Participant compliance is low for our current dietary assessment tool. What features can improve user engagement?

A: Leverage the inherent advantages of e-FFQs and add user-centric features.

- Self-Administration & Automation: Web-based FFQs allow participants to complete surveys at their convenience, reducing the burden on research staff and minimizing data entry errors [36] [38].

- Visual Aids: Integrate graphical elements, such as multiple portion size pictures, to improve estimation accuracy and user-friendliness [38].

- Adaptive Design: Use complex skip patterns to show only relevant questions, shortening completion time and reducing fatigue [38].

Q3: We are concerned about measurement error, particularly underreporting of unhealthy foods. Can technology help mitigate this?

A: Yes, advanced computational methods can be applied to adjust for reporting biases.

- Machine Learning Correction: One proposed method uses a Random Forest classifier to identify potentially misreported entries. The model is trained on data from participants assumed to be accurate reporters (e.g., those classified as "healthy" based on objective biomarkers) and then predicts expected intake values for others. An error adjustment algorithm can then correct underreported entries for unhealthy foods [6].

Q4: How can we validate a newly developed or adapted e-FFQ for our specific study population?

A: Validation is critical and follows a standard protocol comparing the e-FFQ against a reference method.

- Reference Methods: Common reference methods include multiple 24-hour dietary recalls (24HDR) or food records (FR) [39] [37] [35].

- Assessment Metrics: Evaluate both validity (how well the e-FFQ measures what it should) and reproducibility (its consistency over time).

- Validity: Compare the e-FFQ against the reference method using correlation coefficients (e.g., Spearman) and cross-classification analysis (percentage of participants classified into the same or adjacent tertile/quintile) [39] [37] [35].

- Reproducibility (Reliability): Administer the same e-FFQ twice to participants with a time interval (e.g., 1 month). Assess agreement using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and weighted Kappa statistics [39].

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low completion rates | Long, tedious questionnaire; complex interface. | Shorten the food list using data-driven methods [36] [35]; use adaptive questioning and a mobile-friendly design. |

| Implausible energy intake values | Portion size misestimation; misunderstanding of questions. | Use validated portion size pictures and household measures [39] [35]; include clear instructions and tooltips. |

| Poor agreement with reference method for specific food groups | Food list is not representative; recall bias for certain foods. | Re-evaluate and refine the food list based on local consumption [37] [35]; consider using short, repeated recalls for better accuracy [40]. |

| Technical errors in data export | Software bugs; improper database linking. | Perform pilot testing of the entire data pipeline; ensure the e-FFQ platform is securely integrated with the food composition database. |

Experimental Protocols for e-FFQ Validation

The following table summarizes the core methodologies used in recent studies to validate e-FFQs, providing a template for researchers.

| Study (Population) | e-FFQ Items | Reference Method | Validation & Reliability Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss eFFQ [36] | 83 items | Two non-consecutive 24h dietary recalls | Validity: Food list created via stepwise regression to explain >90% variance in key nutrient intake. |

| Trinidad & Tobago [37] | 139 items | Four 1-day food records (using smartphone photos) | Validity: Energy-adjusted deattenuated correlations; cross-classification.Reliability: Test-retest correlation (3-month interval). |

| PERSIAN Cohort [35] | 113 core + local items | Two 24h recalls/month for 12 months | Validity: Correlation between FFQ and 24h recalls.Reliability: Correlation between two FFQs (12-month interval). |

| Fujian, China [39] | 78 items | Three-day 24h dietary recall | Validity: Spearman correlation, Bland-Altman plots, cross-classification into tertiles.Reliability: ICC and weighted Kappa for two FFQs (1-month interval). |

| Charité-14 Item FFQ [41] | 14 items | Weighted food records | Validity: Method agreement analysis (Bland-Altman) and correlation for specific food groups and habits. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in e-FFQ Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recalls (24HDR) | Serves as a reference method for validating the e-FFQ and for data-driven development of the food list. | Use multiple, non-consecutive recalls (e.g., two 24HDRs) [36]. Software like GloboDiet or Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) can standardize collection [18] [36]. |

| Food Composition Database | Converts food consumption data from the e-FFQ into estimated nutrient intakes. | Must be tailored to the study population's specific foods and recipes. Databases are often national (e.g., USDA, Swiss Food Composition Database). |

| Portion Size Estimation Aids | Improves the accuracy of self-reported food quantities in a semi-quantitative FFQ. | Picture albums with standardized portions [35], digital images, household measure descriptions (cups, spoons), or 3D food models [18]. |

| Biomarker Data | Provides an objective measure to help correct for reporting bias (e.g., under-reporting). | Biomarkers like LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and blood glucose can be used in machine learning models to identify misreporting of related foods [6]. |

| Professional Dietary Analysis Software | Used to code and analyze data from reference methods like food records. | Software such as PRODI is used to input and calculate nutrient intake from detailed food records [41]. |

| Alisol B 23-acetate | Alisol B 23-acetate, CAS:19865-76-0, MF:C32H50O5, MW:514.74 | Chemical Reagent |

| (-)-Catechol | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)chroman-3,5,7-triol|(±)-Catechin |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The diagram below visualizes the end-to-end process for developing and validating a culture-specific e-FFQ.

Diagram Title: e-FFQ Development and Validation Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I just use an FFQ by itself in my research? While Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) are excellent for ranking individuals based on their long-term dietary habits, they are known for containing measurement errors, including systematic underreporting. It has been demonstrated that all self-report tools involve some misreporting, with FFQs underestimating energy intake by 29–34% on average, a greater degree than other methods [42]. Integrating FFQs with more precise short-term methods, like 24-hour recalls, allows researchers to calibrate the FFQ data and improve the accuracy of habitual intake estimates [15] [6].

Q2: How many 24-hour recalls are needed to properly validate an FFQ? There is no one-size-fits-all number, but best practices suggest multiple recalls collected over different seasons to account for day-to-day and seasonal variations. One major validation study conducted twenty-four 24-hour recalls per participant over twelve months to serve as a robust reference method [15]. Another study used multiple 24-hour recalls and found they provided better estimates of absolute dietary intakes than FFQs alone [42]. The key is to collect enough recalls to reliably estimate a person's "usual intake."

Q3: What is the main type of error I should look for in FFQ data? Underreporting is the most common and significant error, particularly for energy-dense foods and certain nutrients. This is frequently observed in studies that compare self-reported data with recovery biomarkers [42] [6]. For instance, one study focusing on high-fat foods like bacon and fried chicken used a machine learning model to successfully identify and correct for this underreporting [6].

Q4: Can new technologies like AI help with the limitations of FFQs? Yes, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) present promising avenues for mitigating errors in dietary data. These methods can be used to create error adjustment algorithms. For example, a random forest classifier has been used to identify underreported entries in an FFQ with high accuracy (78% to 92%), demonstrating the potential to correct data without solely relying on additional resource-intensive calibration methods [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Systematic underreporting of energy and nutrient intakes in FFQ data. Solution:

- Calibrate with Reference Methods: Use the data from multiple 24-hour recalls or food records to calibrate your FFQ data. This can involve statistical techniques like regression calibration, which uses the relationship between the FFQ and the more accurate reference method to correct the FFQ values [6].

- Leverage Biomarkers: Where possible, incorporate objective biomarkers. For example, use doubly labeled water for energy intake and 24-hour urinary nitrogen and potassium for their respective nutrient intakes. The "triad method" compares FFQs, reference dietary methods, and biomarkers to assess validity [15] [42].

- Implement Machine Learning: For large datasets, consider a supervised machine learning approach. The workflow involves training a model (e.g., a random forest classifier) on data from participants assumed to be accurate reporters. This model can then predict likely intake values for other participants based on objective health metrics (like cholesterol levels or BMI), and an algorithm can adjust underreported entries [6].

Problem: My FFQ and 24-hour recall data show poor correlation for specific nutrients. Solution:

- Investigate the Nutrient: Some nutrients are more challenging to measure than others. For example, one study found that vitamins B6 and B12 were poorly correlated between FFQs and 24-hour recalls, while correlations for many other micronutrients were moderate to high [15]. Consult existing validation literature for your specific FFQ to set realistic expectations.

- Check Your Food Composition Table: Inconsistencies can arise from using different nutrient databases for the FFQ and the reference method. A meta-analysis found that when mobile diet records and their reference method used the same food-composition table, heterogeneity in energy intake estimation dropped to 0%, and the mean difference was negligible [43]. Always strive for database consistency.

- Increase Number of Recalls: Poor correlation may simply be due to high within-person variation for that nutrient, which isn't fully captured by your number of recall days. Increasing the number of 24-hour recalls can improve the reliability of your reference method for that nutrient.

Problem: High participant burden leads to dropouts or incomplete food records. Solution:

- Use Technology: Employ user-friendly, automated self-administered 24-hour recall systems (ASA24s). Research shows that multiple ASA24s are a feasible means to collect high-quality dietary data and can provide better estimates of absolute intake than FFQs [42].

- Optimize Protocol: While ideal, completing 24 recalls over a year may not be feasible. A well-designed protocol with non-consecutive, seasonal 3-day food records (including one weekend day) can capture variation while being less burdensome [7]. Clear communication and training for participants are vital for compliance.

Quantitative Data from Validation Studies

Table 1: Correlation Coefficients between FFQs and Multiple 24-Hour Recalls [15]

| Nutrient | Correlation with FFQ1 | Correlation with FFQ2 |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | 0.57 | 0.63 |

| Protein | 0.56 | 0.62 |

| Lipids (Fats) | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| Carbohydrates | 0.42 | 0.51 |

This data shows that the PERSIAN Cohort FFQ has acceptable reproducibility (FFQ1 vs. FFQ2) and moderate correlation with the reference method for most macronutrients. [15]

Table 2: Average Underreporting of Energy Intake Compared to Biomarkers [42]

| Dietary Assessment Method | Average Underestimation of Energy |

|---|---|

| Automated 24-hour Recalls (ASA24) | 15–17% |

| 4-Day Food Records (4DFR) | 18–21% |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | 29–34% |

This study highlights the systematic underreporting inherent in all self-report methods, with FFQs showing the greatest degree of underestimation when checked against the doubly labeled water method. [42]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Tools for Integrating Dietary Assessment Methods

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Validated FFQ | The core tool for assessing long-term, habitual dietary intake in large epidemiological studies. It must be validated for the specific population being studied [15] [42]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall Protocol | A structured interview or automated system (e.g., ASA24) used as a reference method to collect detailed intake from the previous day, reducing long-term recall bias [15] [42]. |

| Food Record/Diary | A tool where participants prospectively record all foods and beverages consumed over a specific period (e.g., 3-4 days), providing detailed data without relying on memory [7]. |

| Recovery Biomarkers | Objective biological measurements used to validate reported intakes of specific nutrients. Examples include Doubly Labeled Water for energy, 24-Hour Urinary Nitrogen for protein, and 24-Hour Urinary Sodium & Potassium [15] [42]. |

| Food Composition Database | A standardized nutrient lookup table. Consistency in the database used for both the FFQ and the reference method is critical for accurate comparison and to reduce heterogeneity in results [43]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, SAS) | Essential for performing complex analyses, including regression calibration, correlation analysis, de-attenuation for within-person variation, and machine learning algorithms for error adjustment [7] [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating an FFQ Against 24-Hour Recalls

The following is a detailed methodology based on established validation studies [15] [7]:

Study Population & Sampling: Recruit a sub-sample (typically n=100-200) from your main cohort that is representative in terms of age, sex, and BMI. Ensure ethical approval and informed consent.

Baseline Data Collection:

- Administer the FFQ (FFQ1) at the start of the study, asking about dietary habits over the past year.

- Collect baseline biological samples (if biomarkers are part of the protocol).

Reference Method Data Collection:

- Schedule multiple 24-hour dietary recalls over a period of at least 6-12 months to account for seasonal variation.

- A typical protocol involves conducting two non-consecutive recalls per month for twelve months, totaling 24 recalls per participant.

- Recalls should be conducted by trained dietitians using a multiple-pass method (e.g., USDA protocol) to enhance completeness and accuracy. Interviews can be in-person or by phone.

Follow-up Data Collection:

- At the end of the study period (e.g., month 12), administer the FFQ again (FFQ2) to assess reproducibility.

Data Processing & Analysis:

- Nutrient Calculation: Process all dietary data (FFQs and 24HRs) using the same food composition database.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Validity: Calculate correlation coefficients (Pearson or Spearman) between the nutrient intakes from FFQ1 and the average intake from all 24-hour recalls.

- Reproducibility: Calculate correlation coefficients between nutrient intakes from FFQ1 and FFQ2.

- Classification Analysis: Perform cross-classification to determine the proportion of participants categorized into the same or adjacent quartile by both methods.

- Adjust for Within-Person Variation: Apply de-attenuation correction to the correlation coefficients to account for day-to-day variation in the 24-hour recalls [7].

Optimizing for Efficiency and Accuracy: Data-Driven and Computational Approaches

Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) are essential tools in nutritional epidemiology for assessing habitual dietary intake and investigating diet-disease relationships. A fundamental challenge in FFQ design lies in creating a food list that is comprehensive enough to accurately capture all nutrients of interest, yet short enough to minimize respondent burden and maintain high completion rates. Traditional, expert-led methods for compiling these food lists can be time-consuming, non-standardized, and may yield unnecessarily long questionnaires.

This technical support guide explores how Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP), an operations research technique, provides a rigorous, mathematical framework to overcome this limitation. By optimizing the selection of food items, researchers can develop shorter, more efficient FFQs without compromising their nutritional coverage or ability to detect inter-individual variation in intake [44] [45] [46].

Core Concepts: How MILP Optimizes Food Lists

The Optimization Goal and Constraints

The primary goal of the MILP model in FFQ design is to minimize the number of food items on the list. This objective is subject to crucial nutritional constraints [44] [47] [46]:

- Nutrient Coverage Constraint: Ensures the selected food items account for a large proportion (e.g., ≥ a threshold

b) of the total population intake for each nutrient of interest. - Variance Coverage Constraint: Ensures the selected food items account for a large proportion of the interindividual variance in intake for each nutrient. This is critical for the FFQ's ability to rank individuals within a population [44] [46].