Biomarker Validation Against Controlled Feeding Studies: A Roadmap from Discovery to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating biomarkers using controlled feeding studies.

Biomarker Validation Against Controlled Feeding Studies: A Roadmap from Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating biomarkers using controlled feeding studies. It covers the foundational role of these studies in establishing causal intake-biomarker relationships, details the multi-phase methodological frameworks for biomarker development, addresses common analytical and translational challenges, and outlines the rigorous validation and qualification criteria required for clinical and regulatory acceptance. By synthesizing current methodologies and future trends, this resource aims to bridge the gap between preclinical discovery and the application of robust, validated dietary biomarkers in clinical research and precision medicine.

The Foundational Role of Controlled Feeding Studies in Biomarker Discovery

In the complex field of nutrition science, establishing definitive cause-and-effect relationships between diet and health outcomes represents a significant methodological challenge. While observational studies can identify associations, they often struggle to disentangle true causal effects from confounding factors such as lifestyle, genetics, and environmental influences [1] [2]. Causal inference—the process of determining whether one variable actually causes changes in another—provides the philosophical and statistical framework to move beyond mere correlation to establish true cause-and-effect relationships [1] [3].

Within this framework, controlled feeding studies emerge as the undisputed gold standard for establishing causality in diet-health relationships. These studies, where researchers provide all or most foods consumed by participants under strictly monitored conditions, offer the experimental precision necessary to isolate the specific effects of dietary interventions [2] [4]. For researchers and drug development professionals focused on biomarker validation, controlled feeding studies provide the essential foundational evidence that links potential biomarkers directly to dietary intake, creating a critical bridge between dietary exposure and physiological response [5] [6].

This guide objectively compares controlled feeding studies against alternative methodological approaches, examining their respective roles in establishing causal inference and validating biomarkers for precision nutrition and drug development.

Causal Inference Frameworks: From Observation to Experimentation

The Foundations of Causal Inference

The statistical foundation for modern causal inference rests heavily on the Potential Outcomes Framework (also known as the Rubin Causal Model). This framework conceptualizes each individual as having two potential outcomes: one under treatment (Yâ‚) and one under control (Yâ‚€) [1] [3]. The fundamental challenge in causal inference—the "missing data problem"—arises because we can only observe one of these outcomes for each individual [3]. The Average Treatment Effect is defined as E[Yâ‚ - Yâ‚€], representing the expected difference in outcomes between the treatment and control conditions [1] [3].

Directed Acyclic Graphs provide visual tools to represent causal assumptions and identify confounding variables that might create misleading associations [1]. These conceptual diagrams help researchers structure their causal reasoning and select appropriate statistical methods to account for potential confounders.

Methodological Spectrum in Nutrition Research

Nutritional research employs a spectrum of methodological approaches with varying strengths for causal inference, as compared in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Research Methods for Causal Inference in Nutrition

| Method Type | Key Characteristics | Causal Inference Strength | Primary Limitations | Role in Biomarker Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational Studies | Analyzes existing data without intervention; uses statistical adjustments | Limited for causal claims; identifies associations | Confounding; recall bias; reverse causality | Initial discovery of candidate biomarkers [5] |

| Randomized Behavioral Interventions | Participants randomly assigned to dietary advice or counseling | Moderate; random assignment reduces confounding | Variable intervention fidelity; self-reported intake | Limited utility for biomarker validation |

| Controlled Feeding Studies | Researchers provide all food under controlled conditions | High; maximum control over independent variable | Resource-intensive; limited generalizability | Gold standard for biomarker validation [5] [2] |

Controlled Feeding Studies: The Experimental Gold Standard

Fundamental Principles and Design

Controlled feeding studies are specifically designed to determine cause-and-effect relationships between dietary intake and physiological or health outcomes by eliminating the confounding effects of differences in dietary intake [2]. These studies provide the most rigorous approach for controlling the independent variable (diet) in nutrition research, creating experimental conditions that mirror the precision achieved in pharmaceutical trials [2] [4].

The basic elements of controlled feeding studies include:

- Menu Development: Research dietitians use specialized software to develop menus meeting specific nutrient targets, typically using 3- to 7-day repeating cycles to minimize food variety requirements while maintaining participant compliance [2].

- Food Provision: All foods are prepared and provided to participants, with precise documentation of gram weights and nutrient composition [2].

- Energy Adjustment: Individual energy needs are determined through prediction equations, indirect calorimetry, or doubly labeled water, with adjustments made to maintain weight stability [2].

Experimental Protocols and Compliance Monitoring

Compliance monitoring represents a critical component of high-quality controlled feeding studies. Both in-patient and out-patient approaches employ multiple strategies to verify adherence to study protocols:

- Objective Biomarkers: Urinary sodium, nitrogen, or para-aminobenzoic acid excretion provide quantitative measures of compliance with study diets [2].

- Direct Observation: Some protocols require participants to consume at least one daily meal under staff supervision [2].

- Returned Food Weights: Uneaten foods are returned, weighed, and documented to calculate actual intake [2].

- Rapport Building: Establishing strong researcher-participant relationships encourages honest self-reporting of dietary deviations [2].

Table 2: Key Methodological Considerations in Controlled Feeding Trials

| Design Element | Options | Considerations | Impact on Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Parallel vs. Crossover | Crossover designs increase statistical power but require washout periods | Stronger internal validity with participant-as-own-control [5] |

| Participant Selection | Various populations based on research question | Homogeneous groups reduce variability; diverse groups enhance generalizability | Balance between statistical power and external validity |

| Dietary Control Level | Complete provision vs. partial provision | Degree of control over confounding foods | Greater control strengthens causal claims |

| Intervention Duration | Acute vs. chronic effects | Must align with expected biological response time | Must be sufficient to detect hypothesized effects |

| Blinding | Single, double, or open-label | Maximized when using matched control diets | Reduces performance and detection bias |

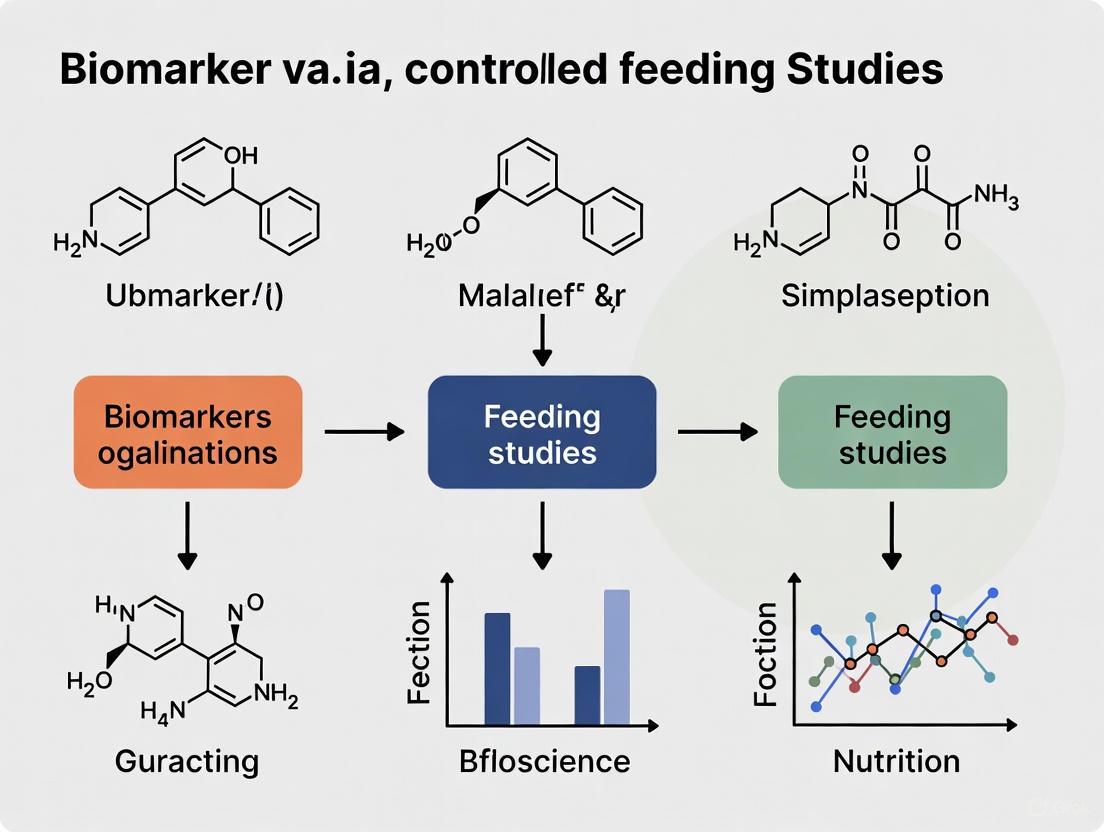

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow and causal logic of a controlled feeding study:

Case Study: Validating Ultra-Processed Food Biomarkers

Experimental Evidence from Complementary Study Designs

A compelling example of controlled feeding's critical role in causal inference comes from recent research on ultra-processed food biomarkers [5]. This research program employed a sophisticated multi-stage approach that combined observational and experimental methodologies:

- Observational Discovery Phase: The IDATA study analyzed 718 free-living adults with diverse dietary intakes, using metabolomic profiling to identify hundreds of serum and urine metabolites correlated with UPF intake [5].

- Controlled Validation Phase: A randomized, controlled, crossover-feeding trial of 20 subjects admitted to the NIH Clinical Center compared diets containing 80% versus 0% energy from UPF [5].

Quantitative Results and Causal Interpretation

The experimental data from this research provides compelling evidence for the causal relationship between UPF intake and specific metabolic signatures:

Table 3: Experimental Data from UPF Biomarker Validation Study

| Metabolite | Specimen | Correlation with UPF (rs) | Controlled Feeding Result | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-Methylcysteine sulfoxide | Serum & Urine | -0.23 (serum), -0.19 (urine) | Significant difference between diets | Potential marker of vegetable intake |

| N2,N5-diacetylornithine | Serum & Urine | -0.27 (serum), -0.26 (urine) | Significant difference between diets | Microbial-host co-metabolite |

| Pentoic acid | Serum & Urine | -0.30 (serum), -0.32 (urine) | Significant difference between diets | Carbohydrate metabolism intermediate |

| N6-carboxymethyllysine | Serum & Urine | +0.15 (serum), +0.20 (urine) | Significant difference between diets | Advanced glycation end product |

The poly-metabolite scores developed from the observational study successfully differentiated, within individuals, between the 80% and 0% UPF diet phases in the controlled feeding trial (P-value for paired t-test < 0.001) [5]. This cross-validation across study designs provides particularly strong evidence for a causal relationship between UPF consumption and specific metabolic profiles.

The following diagram illustrates the complementary strengths of this hybrid study design approach:

Research Reagent Solutions for Controlled Feeding Studies

Table 4: Essential Materials and Methods for Controlled Feeding Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application in Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet Design Software | NDS-R, ProNutra [2] | Menu development and nutrient analysis | Precisely defines and controls the independent variable |

| Metabolomic Platforms | UPLC-MS/MS [5] | High-throughput metabolite profiling | Objective measurement of biochemical responses to diet |

| Compliance Biomarkers | Urinary nitrogen, PABA, sodium [2] | Verification of dietary adherence | Ensures intervention fidelity and reduces misclassification |

| Energy Assessment Tools | Indirect calorimetry, doubly labeled water [2] | Determination of individual energy requirements | Maintains energy balance and weight stability |

| Biospecimen Collection | Serial blood, 24-hour urine [5] | Biological sampling for biomarker analysis | Enables temporal analysis of diet-metabolite relationships |

Methodological Considerations for Implementation

Successful implementation of controlled feeding studies requires attention to several methodological complexities:

- Resource Intensity: Controlled feeding studies typically cost $25-30 per participant daily for food and supplies alone, requiring significant staffing and infrastructure [2].

- Weight Stability Management: Participants are weighed daily, with energy adjustments made to maintain stable body weight—a critical consideration since weight changes themselves can confound physiological outcomes [2].

- Palatability and Compliance: Foods must be palatable and familiar to the target population to maximize long-term compliance, particularly in studies of extended duration [2].

Controlled feeding studies represent an indispensable methodology for establishing causal inference in nutrition science and validating dietary biomarkers. While observational studies and behavioral interventions play important roles in the broader research ecosystem, neither can match the experimental control afforded by providing all study foods under monitored conditions.

For drug development professionals and researchers pursuing biomarker qualification, controlled feeding studies provide the causal evidence necessary to advance biomarkers from exploratory status to probable or known valid biomarkers [6]. The integration of controlled feeding data with observational evidence creates a powerful evidence base for regulatory submissions and clinical implementation.

As precision nutrition advances, the continued development and refinement of controlled feeding methodologies will be essential for translating population-level associations into individualized dietary recommendations and targeted therapies. Their role as the gold standard for causal inference in nutrition science remains unchallenged, providing the foundational evidence upon which effective nutritional interventions and validated biomarkers are built.

In the field of precision nutrition, the discovery and validation of robust dietary biomarkers represents a critical scientific frontier. Unlike pharmaceutical research where controlled dosing is straightforward, nutrition science faces the unique challenge of quantifying intake of complex food matrices and their biological effects. The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) is leading a major effort to address this challenge through systematic discovery and validation of biomarkers for commonly consumed foods [7] [8]. Establishing precise dose-response relationships and comprehensive pharmacokinetic parameters for dietary biomarkers requires specialized experimental approaches that account for the complexity of food as an "exposure." These parameters form the foundation for understanding how specific foods and nutrients are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted by the human body, ultimately enabling the development of objective measures that can complement or replace traditional self-reported dietary assessment methods [7].

The validation of dietary biomarkers against controlled feeding studies represents a paradigm shift in nutritional science. Whereas drug assay validation can utilize spiked reference standards against target nominal levels, biomarker measurement presents a fundamentally different challenge because researchers must demonstrate accuracy and precision by measuring endogenous molecules with varying native analyte levels [9]. This complexity necessitates sophisticated experimental designs that can isolate the effects of specific dietary components amid background noise from habitual diets and individual metabolic variations.

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Pharmacokinetic Parameters

Controlled Feeding Trial Designs

The gold standard for establishing pharmacokinetic parameters for dietary biomarkers involves controlled feeding trials with precise dietary manipulation. The DBDC implements a structured 3-phase approach for biomarker discovery and validation [7] [8]. In Phase 1, researchers administer test foods in prespecified amounts to healthy participants under highly controlled conditions. This is followed by comprehensive metabolomic profiling of blood and urine specimens collected at strategic time points to identify candidate biomarker compounds and characterize their kinetic profiles. These initial feeding studies are specifically designed to characterize the pharmacokinetic parameters of candidate biomarkers, including absorption rates, distribution patterns, metabolic conversion, and elimination half-lives [7].

The execution of controlled feeding studies requires meticulous attention to methodological details. Research dietitians utilize specialized software such as Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) and ProNutra to design menus that meet specific nutrient targets while accommodating individual energy requirements [10] [2]. Foods are carefully selected based on consistent availability through reliable vendors, with some studies incorporating a combination of fresh, frozen, ready-to-eat, canned, dried, cured, and manufactured foods to represent realistic market supply [11]. Menu cycles typically span 3-7 days to minimize the variety of study foods needed while maintaining participant acceptability [2].

Protocol Implementation and Compliance Monitoring

Successful implementation of controlled feeding studies requires rigorous protocols for diet preparation and compliance monitoring. In the Women's Health Initiative Feeding Study (NPAAS-FS), researchers designed individual menu plans for each of 153 postmenopausal women that approximated their habitual food intake as estimated from 4-day food records, adjusted for energy requirements [10]. This innovative approach preserved normal variation in nutrient and food consumption while maintaining controlled conditions—a critical consideration for subsequent biomarker validation.

Compliance monitoring employs both objective and subjective measures. Objective indicators include urinary nitrogen excretion compared to dietary nitrogen intake, doubly labeled water for energy intake validation, and in some cases, incorporation of para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) into study foods with subsequent assessment of urinary excretion [2]. Daily weight checks ensure energy balance is maintained throughout the study, with adjustments made to calorie levels if unintended weight changes occur [2]. Additional compliance measures include daily food checklists, weigh-backs of uneaten food containers, and supervised meal consumption when feasible [11] [2].

Table 1: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters Measured in Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Parameter | Description | Significance in Dietary Biomarkers | Common Measurement Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under Curve) | Total exposure to biomarker over time | Reflects overall bioavailability of food components | Serial blood/urine measurements over 24-72 hours |

| C~max~ | Maximum concentration observed | Indicates peak absorption potential | Peak value from serial measurements |

| T~max~ | Time to reach maximum concentration | Reveals absorption kinetics | Time of C~max~ occurrence |

| Elimination Half-life | Time for concentration to reduce by half | Informs on suitable sampling windows & biomarker persistence | Calculation from elimination phase slope |

| Urinary Recovery | Percentage of ingested compound excreted in urine | Provides quantitative recovery assessment | 24-hour urine collection analysis |

Methodologies for Determining Dose-Response Relationships

Dose-Fractionation and Exposure-Response Studies

The establishment of dose-response relationships for dietary biomarkers requires specialized study designs that systematically vary the amount of test food or nutrient administered. Drawing from methodologies established in tuberculosis drug development, nutritional research adapts dose-fractionation approaches where the same total exposure is divided into different dosing regimens to identify the optimal pattern of intake [12]. These studies are complemented by exposure-effect investigations that correlate varying doses of food components with corresponding biomarker concentrations in biological fluids [12].

In practice, these studies involve administering predetermined amounts of test foods to participants according to carefully designed protocols. For example, the DBDC implements three distinct controlled feeding trial designs in its initial discovery phase, administering test foods in prespecified amounts to healthy participants to identify candidate compounds that exhibit dose-dependent responses [7]. The resulting data enable researchers to establish quantitative relationships between dietary intake levels and subsequent biomarker concentrations, creating mathematical models that can predict intake based on biomarker measurements.

Statistical Considerations and Biomarker Performance Metrics

The evaluation of dose-response relationships requires appropriate statistical approaches and performance metrics. As highlighted in biomarker validation literature, the analytical plan should be predefined before data collection to avoid bias from data-driven analyses [13]. When assessing biomarker performance, key metrics include sensitivity (the proportion of cases with high intake that test positive), specificity (the proportion of cases with low intake that test negative), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves that plot sensitivity versus 1-specificity across all possible biomarker thresholds [13].

Statistical modeling of dose-response data often employs linear regression of log-transformed consumed nutrients on log-transformed biomarker concentrations. In the Women's Health Initiative feeding study, this approach yielded R² values ranging from 0.32 for lycopene to 0.53 for α-carotene, indicating the proportion of variance in intake explained by the biomarker [10]. For biomarkers with potential clinical applications, positive predictive value (proportion of test-positive participants who actually have high intake) and negative predictive value (proportion of test-negative participants who truly have low intake) provide additional important performance characteristics, though these metrics are influenced by the prevalence of consumption patterns in the study population [13].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Dietary Biomarkers from Controlled Feeding Studies

| Biomarker Category | Example Biomarkers | R² Values from WHI Study | Performance Classification | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins | Serum folate, Vitamin B-12 | 0.49–0.51 | Strong | Supplement use, metabolic status |

| Carotenoids | α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein + zeaxanthin | 0.39–0.53 | Moderate to Strong | Fat intake, genetic variation |

| Tocopherols | α-tocopherol | 0.47 | Moderate | Supplement use, fat intake |

| Fatty Acids | Phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids | 0.27 | Weak to Moderate | Background diet, metabolism |

| Reference Biomarkers | Urinary nitrogen, Doubly labeled water | 0.43–0.53 | Established benchmark | Protein turnover, metabolic efficiency |

Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Validation Approaches

Nutritional vs. Pharmaceutical Biomarker Validation

The validation of dietary biomarkers differs significantly from pharmaceutical biomarker validation in several key aspects. While drug assays can measure recovery of spiked reference standards against target nominal levels, dietary biomarker validation must demonstrate accuracy and precision for endogenous molecules with varying native analyte levels [9]. This fundamental distinction necessitates different scientific approaches for accuracy assessment, though precision evaluation still relies on repeated measurements of the same samples to evaluate measurement variability.

Another critical difference lies in the complexity of the exposure. Pharmaceutical studies typically involve administration of a single chemical entity, whereas nutritional research must account for complex food matrices that contain numerous interacting compounds that may influence bioavailability and metabolism [7] [11]. Additionally, dietary biomarkers must function against the background of habitual diet, requiring them to be sufficiently specific to detect the signal of interest amid considerable metabolic noise.

Assessment of Biomarker Accuracy and Precision

For dietary biomarkers, accuracy assessment presents particular challenges because reference materials with known endogenous analyte concentrations are generally unavailable [9]. Scientifically sound approaches include method comparison with established reference methods when available, and spike-and-recovery experiments at varying concentration levels across the assay range. Parallelism testing using serially diluted patient samples helps demonstrate that the assay maintains linearity across the measuring range for actual patient samples rather than just spiked standards [9].

Precision evaluation follows more conventional approaches, involving repeated measurements of the same samples to evaluate measurement variability [9]. This includes within-run precision (repeatability), between-run precision, and total precision assessed across multiple days, operators, and instrument calibrations. However, the key distinction from drug assays lies in the sample type—dietary biomarker precision must be demonstrated using actual biological samples with inherent analyte variability rather than controls spiked with reference material [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Studies

The successful execution of controlled feeding studies for establishing dose-response and pharmacokinetic parameters requires specialized research reagents and resources. The following table summarizes essential materials and their applications in dietary biomarker research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in Biomarker Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Software | NDS-R, ProNutra | Menu development, nutrient analysis, production sheets | Database completeness critical for accurate nutrient targeting |

| Biospecimen Collection Systems | EDTA tubes, serum separator tubes, urine collection containers | Biological sample preservation for metabolomic analysis | Strict protocols for handling, processing, and storage stability |

| Analytical Instrumentation | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR spectrometers | Metabolomic profiling and biomarker quantification | Sensitivity requirements dependent on expected biomarker concentrations |

| Reference Biomarkers | Doubly labeled water, para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) | Objective compliance monitoring and energy expenditure measurement | Cost considerations for stable isotopes |

| Food Composition Resources | USDA FoodData Central, branded food databases | Recipe development and nutrient calculation | Regular updates needed to reflect changing food supply |

| Quality Control Materials | Pooled plasma, in-house quality control samples, NIST reference materials | Assay performance monitoring and inter-laboratory standardization | Stability monitoring essential for long-term studies |

The establishment of dose-response relationships and pharmacokinetic parameters for dietary biomarkers represents a methodological cornerstone in the advancement of precision nutrition. Controlled feeding studies provide the experimental foundation for characterizing how food components are processed by the human body and identifying objective biomarkers that can reliably reflect dietary intake. The systematic approach implemented by initiatives such as the Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium—progressing from initial discovery under highly controlled conditions to validation in free-living populations—offers a robust framework for expanding the limited repertoire of validated dietary biomarkers [7].

As this field advances, the integration of sophisticated metabolomic technologies with rigorous controlled feeding designs will enable researchers to develop increasingly sensitive and specific biomarkers for a wider range of foods and dietary patterns. These tools hold tremendous promise for strengthening diet-disease association studies, improving dietary assessment in clinical practice, and ultimately advancing our understanding of how diet influences human health across the lifespan. The methodological considerations outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers seeking to contribute to this rapidly evolving field at the intersection of nutrition, metabolomics, and precision health.

Controlled feeding studies are the gold standard in nutritional research for discovering and validating dietary biomarkers, which are objective biological measurements that accurately reflect dietary intake. These biomarkers are crucial for moving beyond error-prone self-reported diet data in understanding diet-disease relationships. The fundamental challenge in nutritional science lies in designing studies that balance rigorous experimental control with real-world applicability. Research designs span a spectrum from highly standardized meals, where all participants consume identical foods, to mimicked habitual diets, where study meals are personalized to approximate each participant's usual intake [10]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations in biomarker development, influencing the types of biomarkers that can be discovered, the feasibility of study execution, and the eventual applicability of findings to free-living populations. This guide compares these key study designs, detailing their experimental protocols, applications, and roles in building robust evidence for dietary biomarkers.

Comparison of Key Study Design Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the major controlled feeding study designs used in dietary biomarker research.

Table 1: Comparison of Controlled Feeding Study Designs for Dietary Biomarker Research

| Study Design Approach | Core Characteristics | Primary Applications in Biomarker Research | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Meals(e.g., DBDC Phase 1 [7] [8]) | All participants receive the same fixed menus, often with specific test foods administered in prespecified amounts. | - Discovery of candidate biomarkers [7] [8].- Characterization of pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., appearance, peak, clearance in blood/urine) [7] [8].- Testing biomarker specificity. | - Controls for dietary variance.- Simplifies food preparation and logistics.- Ideal for establishing causal links between a specific food and a metabolite. | - Low ecological validity; does not reflect habitual diets.- Limited ability to test biomarker performance with different food matrices or background diets. |

| Mimicked Habitual Diets(e.g., WHI Feeding Study [10]) | Individualized menu plans are created for each participant based on their self-reported habitual intake (e.g., from food records). | - Validation of candidate biomarkers in a context that preserves usual dietary variation [10].- Evaluating how well biomarkers reflect intake variation in a cohort. | - Preserves normal inter-individual variation in food consumption [10].- Higher participant compliance due to food familiarity.- More realistic for evaluating biomarker performance for epidemiological use. | - Extremely resource-intensive (diet formulation, food procurement, preparation).- Relies on accuracy of self-reported habitual diet for personalization. |

| Semi-Controlled / Hybrid(e.g., mini-MED Trial [14]) | Study provides specific, set intervention foods or diet patterns, but participants prepare and consume meals in their own homes. | - Evaluating biomarker response to incremental dietary changes.- Testing biomarker robustness in real-world settings. | - Good balance between control and real-world applicability.- Allows assessment of compliance in free-living conditions.- Can test biomarker generalizability across food preparations. | - Less control over exact food preparation and timing.- Requires careful monitoring to ensure protocol adherence. |

| Free-Living with Provided Food(e.g., MAIN Study [15]) | All foods and drinks are provided to participants, who prepare and consume them in their own homes while following specific menu plans. | - Discovery and validation of biomarkers in a real-world context [15].- Testing urine sampling strategies for optimal biomarker detection [15]. | - High ecological validity while maintaining known dietary exposure.- Assesses impact of home cooking methods on biomarkers [15].- Well-suited for large-scale epidemiological study protocols. | - Logistically complex to package and distribute all food.- Dependent on participant compliance without direct supervision. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standardized Meal Design: The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) Protocol

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) employs a highly structured, multi-phase protocol for biomarker discovery and validation [7] [8]. In Phase 1, the focus is on discovery through controlled feeding trials.

- Participant Recruitment: Healthy participants are recruited, often with specific exclusion criteria (e.g., high-level athletes, individuals with certain medical conditions or medications) to minimize metabolic confounding [15].

- Dietary Intervention: Test foods are administered in prespecified amounts. For example, a study might involve a run-in period followed by a day where a single test food or a simple diet with the test food is consumed [7].

- Biospecimen Collection: Blood and urine specimens are collected at multiple timed intervals (e.g., fasted, and then at 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours post-prandially) to characterize the pharmacokinetic profile of candidate biomarkers [7] [8].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Collected specimens are analyzed using high-throughput metabolomics platforms, typically mass spectrometry coupled with liquid or gas chromatography, to generate comprehensive metabolic profiles [7] [15].

- Data Analysis: Bioinformatic analyses compare pre- and post-consumption metabolomic profiles to identify compounds that significantly increase after ingestion of the test food. These are considered candidate biomarkers [7].

Mimicked Habitual Diet Design: The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Protocol

The WHI Feeding Study protocol is designed to validate biomarkers under conditions that mirror a cohort's natural eating patterns [10].

- Baseline Dietary Assessment: Participants first complete a 4-day food record (4DFR) and an in-depth interview with a study dietitian to assess usual food choices, brands, recipes, and meal patterns [10].

- Individualized Diet Formulation: Each participant's study menu is designed to approximate her habitual food intake. Food record data is entered into nutritional analysis software (e.g., Nutrition Data System for Research, NDS-R), and menus are created using specialized diet formulation software (e.g., ProNutra) [10].

- Energy Intake Calibration: To prevent under-reporting bias and ensure energy needs are met, the prescribed energy intake is often calibrated using equations that incorporate BMI, age, and previously developed calibration factors from the larger cohort [10].

- Controlled Feeding Period: Participants consume their personalized diets for a set period (e.g., 2 weeks). All meals are prepared in a metabolic kitchen [10].

- Biomarker Assessment: Biospecimens (serum, urine) are collected at the beginning and end of the feeding period. The relationship between the consumed nutrients and the concentration of potential biomarkers is analyzed using linear regression, with the explained variation (R²) used to evaluate biomarker performance [10].

Real-World Validation Design: The MAIN Study Protocol

The MAIN (Metabolomics at Aberystwyth, Imperial and Newcastle) Study protocol validates biomarker methodology in a free-living context [15].

- Menu Plan Design: Six daily menu plans are designed to emulate real-world UK eating patterns, delivering a wide range of foods within conventional meals [15].

- Food Provision and Home Consumption: Free-living participants are provided with all foods and drinks but prepare and consume them in their own homes, following protocols for meal timing [15].

- Urine Sampling Strategy: Participants collect spot urine samples at home at multiple specified time points post-meals. This tests a minimally invasive sampling protocol and identifies the optimal time for biomarker detection in free-living individuals [15].

- Compliance Monitoring: Adherence to menu plans and urine collection protocols is monitored, for example, through self-report and returned food packaging [15].

- Metabolome Analysis: Urine samples are analyzed using mass spectrometry, and data mining techniques are used to confirm known biomarkers and discover novel putative biomarkers for an extended range of foods [15].

Logical Workflow for Biomarker Validation

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage, iterative pathway from initial biomarker discovery to final validation for use in epidemiological studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of controlled feeding studies for biomarker development relies on a suite of specialized reagents, software, and laboratory materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Diet Formulation Software | ProNutra [10], Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) [10] | Creates menus, recipes, and production sheets; tracks planned vs. consumed nutrient intake to ensure dietary control. |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS) [15] [14] | Provides high-throughput, sensitive detection and quantification of thousands of metabolites in biospecimens for biomarker discovery. |

| Biospecimen Collection Kits | Urine collection containers (e.g., 30mL cups), blood collection tubes (e.g., EDTA, serum separator) [15] [10] | Ensures standardized, stable, and contamination-free sample collection from participants at multiple time points. |

| Reference Databases | FoodB (University of Alberta), Phenol-Explorer (INRA) [15], MassBank [16] | Aids in identifying detected metabolites by providing reference mass spectra and compound concentrations in foods. |

| Calibration Biomarkers | Doubly Labeled Water (DLW), 24-hour Urinary Nitrogen [10] | Provides objective, recovery biomarkers for total energy and protein intake to validate dietary intake data and self-report. |

| Procyanidin | Procyanidin | |

| Atorvastatin-d5 Lactone | Atorvastatin-d5 Lactone, MF:C33H33FN2O4, MW:545.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey from standardized meals to mimicked habitual diets represents a critical pathway for strengthening dietary biomarker research. Standardized designs are unparalleled for initial discovery and establishing causal intake-biomarker relationships under highly controlled conditions. In contrast, mimicked habitual diet designs are essential for subsequent validation, demonstrating that candidate biomarkers perform reliably amidst the complex variation of real-world diets. The emerging paradigm, exemplified by the DBDC framework and hybrid trials like mini-MED, is a sequential, multi-phase strategy that leverages the strengths of both approaches [7] [14]. This integrated methodology ensures that the biomarkers of the future are not only chemically identifiable but also robust, specific, and meaningful tools for accurately assessing dietary exposure in large-scale epidemiological studies and clinical trials, thereby advancing the field of precision nutrition.

The accurate measurement of dietary intake and early disease states represents a fundamental challenge in medical research and public health. Traditional reliance on self-reported data, such as food frequency questionnaires, introduces substantial measurement error that can obscure true diet-disease associations [17]. Similarly, in clinical diagnostics, traditional metabolic screening approaches often provide limited diagnostic yield, potentially missing treatable conditions [18]. Metabolomic profiling has emerged as a powerful solution to these challenges, offering a comprehensive analysis of small molecules in biological systems that reflects both genetic predisposition and environmental exposures, including diet.

This objective data is particularly crucial for validating findings from nutritional epidemiology and improving diagnostic precision. Controlled feeding studies, where participants consume precisely measured diets, serve as the gold standard for discovering and validating dietary biomarkers because they provide known intake against which metabolomic changes can be calibrated [19] [17]. The transition from traditional targeted biochemical analyses to untargeted metabolomic profiling represents a paradigm shift in biomarker science, enabling the simultaneous assessment of hundreds to thousands of metabolites from minimal biological samples [18] [20].

This guide compares the performance of traditional metabolic assessment methods against modern metabolomic approaches, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform study design and biomarker selection. We objectively evaluate these technologies within the critical context of biomarker validation, with a special emphasis on insights gained from controlled feeding studies.

Performance Comparison: Traditional Screening vs. Modern Metabolomic Profiling

Diagnostic Yield and Applications

Different metabolic profiling approaches offer varying capabilities depending on the research or clinical context. The table below compares the performance characteristics of traditional metabolic screening versus contemporary metabolomic profiling.

Table 1: Performance comparison of traditional metabolic screening versus untargeted metabolomic profiling

| Feature | Traditional Metabolic Screening | Untargeted Metabolomic Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Analytes | Plasma amino acids, acylcarnitines, urine organic acids [18] | Hundreds to thousands of small molecule metabolites simultaneously [18] [20] |

| Diagnostic Rate | 1.3% (19/1483 families) [18] | 7.1% (128/1807 families) [18] |

| Conditions Identified | 14 IEMs, including 3 not on RUSP [18] | 70 different metabolic conditions, including 49 not on RUSP [18] |

| Dietary Prediction (CV-R²) | Not applicable for direct dietary assessment | 36.3% for protein intake; 37.1% for carbohydrate intake [19] |

| Key Strengths | Standardized protocols, established clinical interpretation | ~6-fold higher diagnostic yield, broader condition detection, objective dietary assessment [18] |

Biomarker Prediction Accuracy for Dietary Intake

Metabolomic biomarkers show varying predictive performance for different macronutrients. The following table summarizes the prediction accuracy of metabolomic-based biomarkers for macronutrient intake, with and without incorporation of established recovery biomarkers.

Table 2: Prediction accuracy (cross-validated R²) of metabolomic biomarkers for macronutrient intake

| Dietary Component | Metabolites Only | With Established Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal/day) | Information not available | 55.5% [19] |

| Protein (g/day) | Information not available | 52.0% [19] |

| Protein (% energy) | 36.3% [19] | 45.0% [19] |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | Information not available | 55.9% [19] |

| Carbohydrate (% energy) | 37.1% [19] | 37.0% [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Controlled Feeding Study Design for Biomarker Discovery

The most robust metabolomic biomarkers originate from controlled feeding studies, which minimize the measurement error inherent to self-reported dietary data [17]. The Women's Health Initiative Nutrition and Physical Activity Assessment Study Feeding Study (NPAAS-FS) provides a exemplary protocol:

- Participant Profile: 153 postmenopausal women from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) [19] [17]

- Study Duration: 2-week controlled feeding period [19]

- Dietary Design: Individualized menus created to mimic each participant's habitual diet based on pre-study 4-day food records, preserving natural intake variation while controlling for exact composition [17]

- Sample Collection: Fasting blood samples, 24-hour urine collections, and spot urine samples [19]

- Control Measures: All foods prepared under controlled conditions at a dedicated nutrition laboratory [17]

This design creates the necessary conditions for discovering reliable biomarkers by establishing known intake levels against which metabolomic changes can be correlated.

Metabolomic Analysis Workflows

Sample Processing and Data Acquisition

Comprehensive metabolomic profiling employs multiple analytical platforms to capture diverse biochemical classes:

- Serum Metabolomics: Fasting serum samples are typically analyzed using targeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for aqueous metabolites combined with direct-injection quantitative lipidomics platforms [19]

- Urinary Metabolomics: 24-hour urine and spot urine samples can be analyzed using ¹H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy at 800 MHz and untargeted gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [19]

- Data Preprocessing: Raw data undergoes noise filtering, peak detection and deconvolution, metabolite identification, peak alignment, and creation of a final data matrix for statistical analysis [21]

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Statistical Analysis: Variable selection methods build prediction models for each dietary variable, with performance evaluated through cross-validated multiple correlation coefficients (CV-R²) [19]

- Pathway Analysis: Metabolites identified as significant are mapped to biochemical pathways to interpret biological relevance [20]

- Validation: Biomarker panels discovered in feeding studies are moved forward to create calibration equations for dietary self-reports in observational studies [17]

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for metabolomic biomarker discovery and validation, spanning from controlled study design to clinical application.

Biomarker Validation Through Regression Calibration

Once candidate biomarkers are identified through controlled feeding studies, they can be applied to correct measurement error in self-reported dietary data from observational studies:

- Calibration Equations: Biomarker panels meeting prespecified criteria (e.g., cross-validated R² ≥ 36%) are used to create calibration equations for dietary self-reports [17]

- Disease Association Estimation: The calibrated intake values are then used in diet-disease association analyses, substantially reducing bias from measurement error [22]

- Application Example: This method has been successfully applied to examine associations between sodium/potassium intake ratio and cardiovascular disease incidence in the Women's Health Initiative cohort [22]

Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease

Pathway Dysregulation in Disease States

Metabolomic profiling reveals consistent alterations in key biochemical pathways across various disease states:

- Cancer Metabolism: Breast cancer subtypes show distinct metabolic signatures, with HER2-enriched and basal-like subtypes demonstrating increased glycolytic activity, glutamine metabolism, and lipid biosynthesis [20]

- Energy Metabolism: Luminal A breast tumors typically rely more on oxidative phosphorylation, while Luminal B tumors show higher glycolytic activity, contributing to differences in aggressiveness [20]

- Amino Acid Metabolism: Proline catabolism via proline dehydrogenase (PRODH) supports growth and spread of metastatic breast cancer cells, with elevated activity observed in metastatic versus primary tumors [20]

- Redox Homeostasis: Cancer cells upregulate antioxidant pathways to maintain redox balance amidst increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [20]

Dynamic Visualization of Metabolic Networks

Advanced visualization techniques now enable researchers to observe metabolic changes over time:

- GEM-Vis Method: This approach creates animated visualizations of time-course metabolomic data within metabolic network maps, allowing observation of metabolic state changes throughout experiments or disease processes [23]

- Visual Representation: Nodes (metabolites) are represented with fill levels corresponding to their concentrations, enabling intuitive interpretation of quantitative changes across pathways [23]

- Application Examples: This method has been applied to human platelet and erythrocyte metabolism under cold storage conditions, revealing nicotinamide accumulation patterns that mirror hypoxanthine changes [23]

Figure 2: Key metabolic pathways in health and disease, showing how nutrient processing through core biochemical modules supports cellular functions and contributes to disease signatures detectable by metabolomics.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful metabolomic biomarker studies require specific research reagents and platforms. The following table details essential solutions for conducting comprehensive metabolomic analyses.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for metabolomic biomarker studies

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Targeted analysis of aqueous metabolites with high sensitivity and specificity | Quantification of amino acids, carbohydrates, organic acids in serum [19] |

| Quantitative Lipidomics Platforms | Direct-injection mass spectrometry for comprehensive lipid profiling | Analysis of phospholipids, sphingolipids, and other lipid classes [17] [20] |

| ¹H NMR Spectroscopy | Structural analysis of metabolites without extensive sample preparation | Profiling of urinary metabolites at 800 MHz frequency [19] |

| GC-MS Systems | Untargeted analysis of volatile and derivatized metabolites | Discovery of novel metabolic patterns in urine samples [19] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Tracking metabolic flux through pathways | Dynamic assessment of nutrient utilization [20] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring analytical performance across batches | Pooled quality control samples for data normalization [21] |

| Metabolomic Databases | Metabolite identification and pathway mapping | HMDB, KEGG, BioModels for data interpretation [21] [23] |

Metabolomic profiling represents a transformative approach for identifying candidate biomarkers that outperform traditional metabolic screening methods in both nutritional assessment and clinical diagnostics. The ~6-fold higher diagnostic yield for inborn errors of metabolism and the ability to objectively quantify dietary intake through calibrated biomarker panels demonstrate the superior performance of comprehensive metabolomic approaches.

The power of metabolomic profiling is maximally realized when biomarkers are discovered through well-controlled feeding studies that provide known intake data for validation. These rigorously validated biomarkers can then correct measurement error in self-reported data from large observational studies, leading to more accurate diet-disease association estimates.

As metabolomic technologies continue to advance, with improved sensitivity, computational visualization tools, and dynamic pathway mapping, researchers and drug development professionals can leverage these approaches to develop more precise biomarkers for early disease detection, prognosis assessment, and therapeutic monitoring across a broad spectrum of metabolic conditions.

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) as a Case Study

Accurately measuring what people eat is a fundamental challenge in nutritional science and epidemiology. Traditional methods, such as food frequency questionnaires and dietary recalls, are hampered by significant limitations, including recall bias and an individual's inability to accurately report their own intake [7]. These subjective methods have impeded progress in understanding the precise links between diet and health outcomes. Objective biomarkers of dietary intake, which are measurable biological indicators of food consumption, are widely recognized as a critical tool for advancing the field of precision nutrition [7] [13]. The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) represents a coordinated, large-scale scientific initiative designed to address this challenge by systematically discovering and validating robust biomarkers for foods commonly consumed in the United States diet [7] [24]. This article uses the DBDC as a case study to explore the rigorous experimental protocols and validation frameworks required to translate biomarker discovery from controlled research settings into clinically and epidemiologically useful tools.

The DBDC's Systematic Three-Phase Validation Framework

The DBDC employs a structured, three-phase approach to biomarker development, moving from initial discovery to real-world evaluation. This framework ensures that candidate biomarkers are rigorously tested for their sensitivity, specificity, and reliability. The overarching workflow of the consortium's strategy is illustrated below.

DBDC Validation Workflow

Phase 1: Biomarker Discovery and Pharmacokinetic Profiling

The initial discovery phase focuses on identifying candidate compounds and understanding their behavior in the body. This phase employs controlled feeding trials where specific test foods are administered to healthy participants in predetermined amounts [7]. For instance, the "Fruit and Vegetable Biomarker Study" (Aim 2) investigates biomarkers for bananas, peaches, strawberries, tomatoes, green beans, and carrots [25]. Key methodological steps include:

- Controlled Diets: Participants are provided with all foods and beverages and are required to consume only what is provided, ensuring exact knowledge of intake [25].

- Specimen Collection: Serial blood and urine specimens are collected at precise time points following test food consumption [7] [25].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Advanced metabolomic techniques are used to analyze the specimens, generating comprehensive profiles of small molecules to identify compounds that change in response to food intake [7].

- Pharmacokinetics: The data are used to characterize the pharmacokinetic parameters—such as the rise time, peak concentration, and clearance rate—of candidate biomarkers [7].

Phase 2: Biomarker Evaluation in Diverse Dietary Patterns

In Phase 2, the ability of the candidate biomarkers to accurately classify individuals who have consumed the target food is evaluated. This phase also uses controlled feeding studies, but the test foods are incorporated into various complex dietary patterns to assess the biomarker's specificity and performance in a more realistic, mixed-diet context [7]. This step is crucial for determining whether a biomarker remains valid when the background diet changes.

Phase 3: Validation in Observational Settings

The final validation phase tests the performance of the most promising biomarkers in independent, free-living populations. This assesses the biomarker's utility for predicting both recent and habitual consumption of specific foods without the constraints of a controlled feeding study [7]. Success in this phase demonstrates that a biomarker is ready for deployment in large-scale epidemiological research.

Comparative Analysis: DBDC Versus General Biomarker Validation

The DBDC's methodology aligns with established best practices for biomarker validation but is specially tailored to the unique challenges of dietary exposure. The table below contrasts the DBDC's approach with general biomarker validation principles.

Table 1: Comparison of Validation Frameworks

| Validation Component | General Biomarker Best Practices [13] [26] | DBDC Application & Protocol [7] [25] |

|---|---|---|

| Intended Use Definition | Define the biomarker's purpose (e.g., diagnostic, prognostic) early. | Purpose: Objective measurement of specific food intake for nutritional epidemiology. |

| Study Population | Patients and specimens must reflect the target population. | Healthy adults (BMI 18.5-39.9); controlled diet to define true exposure. |

| Specimen Collection | Proper handling and storage protocols are essential. | Strict protocols for serial blood, urine, and optional stool collection. |

| Analytical Techniques | Use of high-throughput technologies (e.g., mass spectrometry, NGS). | Primary use of metabolomics for high-throughput profiling of small molecules. |

| Blinding & Randomization | Critical to avoid bias during data generation and patient evaluation. | Random assignment to dietary intervention groups (e.g., high vs. low fruit/vegetable arms). |

| Statistical & Analytical Methods | Pre-planned analysis; control for multiple comparisons; use of ROC curves, sensitivity/specificity. | High-dimensional bioinformatics; public database archiving for broad research access. |

| Context of Use | Validation should be fit-for-purpose [26]. | Tailored for precision nutrition and association studies in public health. |

Core Experimental Protocols in Controlled Feeding Studies

The DBDC's work relies on meticulously designed controlled feeding studies, which serve as the gold standard for establishing a causal link between dietary intake and biomarker presence.

Study Design and Participant Selection

The protocol for the Fruit and Vegetable Biomarker Study exemplifies a robust design:

- Design: Randomized, controlled dietary intervention with three distinct arms: a diet high in test fruits and vegetables, a diet low in them, and a diet devoid of them [25].

- Duration: Approximately 10 days of controlled feeding [25].

- Participants: Relatively healthy adults screened for specific criteria to minimize confounding variables. Exclusion criteria include allergies to test foods, pregnancy, gastrointestinal disorders, unstable cardiovascular disease, and recent cancer treatment [25].

Dietary Intervention and Sample Collection

- Dietary Control: Participants are provided with all food and beverages for the entire study period and are instructed to consume only these items [25]. This eliminates dietary misreporting and ensures precise knowledge of exposure.

- Biospecimen Collection: Multiple biological samples are collected to capture a comprehensive metabolic picture. This typically includes:

- 2-3 blood samples

- 2-3 overnight urine samples

- 2 optional stool collections [25]

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of dietary biomarker studies requires a suite of specialized reagents and analytical platforms. The following table details key components of the research toolkit as employed in the DBDC and related biomarker discovery efforts.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Biomarker Discovery

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Identification and quantification of metabolites in biospecimens; central to metabolomic profiling. | Used for proteomic [27] and metabolomic analysis in DBDC [7]. |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Software | Processing and interpreting high-dimensional data from omics platforms; statistical analysis. | Used for high-dimensional bioinformatics in DBDC [7]; machine learning for pattern recognition [28] [29]. |

| Stable Isotope Standards | Internal standards for mass spectrometry to enable precise quantification of analyte concentrations. | Implied in precise metabolomic quantification; standard in mass spectrometry-based assays [27]. |

| Protein & Gene Expression Arrays | High-throughput screening of protein or gene expression patterns for candidate biomarker discovery. | Protein arrays for detecting proteins in complex samples [27]; DNA microarrays for gene expression [27]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Genomic analysis to understand host-genome interactions with diet and for microbial profiling. | Used to identify genetic mutations in cancer biomarker research [27]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Separation of complex biological mixtures prior to mass spectrometry analysis. | Essential for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), a core metabolomics technology. |

| 4-Bromobenzoic-d4 Acid | 4-Bromobenzoic-d4 Acid, MF:C7H5BrO2, MW:205.04 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Phenoxybenzoic acid-13C6 | 3-Phenoxybenzoic acid-13C6, CAS:1793055-05-6, MF:C13H10O3, MW:219.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrating Multi-Omics and AI in Biomarker Discovery

The DBDC and the broader field are increasingly leveraging integrated technologies to manage the complexity of diet as a biological exposure. The relationship between these technologies is shown below.

Multi-Omics & AI Integration

- Multi-Omics Approaches: The DBDC primarily utilizes metabolomics, but the wider field is moving toward integrating genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to achieve a holistic view of biological responses to diet [28] [27]. This systems biology approach is crucial for identifying comprehensive biomarker signatures that reflect the complexity of food as an exposure.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI and ML are revolutionizing biomarker discovery by enabling the analysis of these vast, complex datasets. Key applications include:

- Predictive Analytics: Building models to forecast individual metabolic responses to specific foods [28].

- Automated Data Interpretation: ML algorithms significantly reduce the time required for biomarker discovery and validation by automating the analysis of complex datasets [28].

- Pattern Recognition: These tools are essential for uncovering subtle patterns in omics data that distinguish between dietary exposures [29].

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium serves as a paradigm for rigorous biomarker validation within a fit-for-purpose framework. Its structured three-phase approach, reliance on controlled feeding studies as a foundational benchmark, and adoption of advanced metabolomic and bioinformatic technologies create a robust model for translating complex dietary exposures into reliable, objective measures. The biomarkers emerging from this and similar consortia are poised to dramatically improve the precision of nutritional epidemiology, enabling stronger evidence-based linkages between diet and health. This progress, in turn, will empower the development of more effective, personalized dietary recommendations and public health strategies.

Methodological Frameworks and Analytical Applications

In nutritional science and drug development, the journey from biomarker discovery to clinical application presents a significant challenge. Biomarkers—objective biological indicators of exposure, response, or susceptibility—require rigorous validation to transition from promising discoveries to trusted tools for research and clinical decision-making. This process is particularly complex for dietary biomarkers, where the multifaceted nature of food intake, metabolic variability, and confounding factors necessitate a structured, multi-phase approach. Controlled feeding studies serve as the cornerstone of this validation pathway, providing the scientific community with high-quality evidence for biomarker utility.

The validation pathway for dietary biomarkers has evolved substantially with advances in metabolomics and analytical technologies. This guide examines the current methodologies, benchmarks performance across alternative approaches, and provides the experimental protocols essential for implementing a robust biomarker validation strategy.

A Three-Phase Framework for Biomarker Validation

The biomarker validation pathway is systematically structured into consecutive phases, each with distinct objectives and evaluation criteria. The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) has pioneered a comprehensive 3-phase approach specifically for dietary biomarkers that represents the current gold standard in the field [7] [8].

Table 1: Core Phases in the Biomarker Validation Pathway

| Phase | Primary Objective | Study Designs | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Discovery & Identification | Identify candidate compounds associated with specific dietary exposures | Controlled feeding trials with predefined test foods; metabolomic profiling of blood/urine [7] | Candidate biomarkers with characterized pharmacokinetic parameters [7] |

| Phase 2: Evaluation & Qualification | Assess ability of candidates to identify consumers of target foods | Controlled feeding studies of various dietary patterns; dose-response and time-response analyses [30] | Biomarkers with demonstrated specificity, sensitivity, and performance across patterns [7] |

| Phase 3: Real-World Prediction | Validate predictive value in independent observational settings [7] | Large-scale cohort studies; free-living populations [30] | Biomarkers validated for predicting habitual consumption in diverse, real-world settings [7] |

This phased approach ensures rigorous evaluation before biomarkers are deployed in research or clinical settings. The transition between phases depends on achieving predefined performance benchmarks, creating a gated pathway that prioritizes biomarker quality.

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Controlled Feeding Study Design

Controlled feeding studies represent the foundation of Phase 1 biomarker validation. The Women's Health Initiative feeding study implemented a robust protocol where 153 postmenopausal women were provided with a 2-week controlled diet specifically designed to approximate each participant's habitual food intake based on 4-day food records [10]. This innovative approach preserved normal variation in nutrient consumption while maintaining controlled conditions—a critical balance for meaningful biomarker validation.

Key methodological considerations:

- Diet Formulation: Individualized menus created using professional nutrition software (e.g., ProNutra) with selective sourcing of foods with complete nutrient database values [10]

- Energy Adjustment: Food prescriptions adjusted based on calibrated energy estimates using standard energy equations and previous calibration data [10]

- Sample Collection: Blood and urine specimens collected at baseline and post-intervention under standardized conditions [10]

- Biomarker Analysis: Serum biomarkers including carotenoids, tocopherols, folate, vitamin B-12, and phospholipid fatty acids analyzed with established analytical methods [10]

Metabolomic Profiling Techniques

Metabolomic profiling serves as the primary technological platform for biomarker discovery in Phase 1. The choice of analytical platform depends on the specific research questions and required sensitivity [30].

Table 2: Metabolomic Platforms for Biomarker Discovery

| Platform | Principle | Sensitivity | Sample Requirements | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Measures nuclear spin transitions in magnetic fields | Lower sensitivity, high abundance metabolites | Larger sample volumes (non-destructive) | Broad-based metabolic profiling, quantitative analysis [30] |

| LC/GC-MS | Separates compounds by chromatography with mass detection | High sensitivity | Small sample volumes (non-recoverable) | Targeted and untargeted analysis of diverse metabolites [30] |

| Tandem MS (MS/MS) | Fragments ions for structural identification | Very high sensitivity | Minimal sample volume | Structural elucidation, confirmation of biomarker identity [31] |

Liquid-chromatography-mass-spectrometry (LC-MS) has emerged as particularly valuable for protein and metabolite biomarker discovery due to its sensitivity and specificity. Best practices include rigorous sample randomization, blinding, and quality control throughout the analytical process [31].

Performance Comparison: Validation Criteria and Biomarker Classes

The validation of food intake biomarkers requires demonstration of performance across multiple criteria. Different classes of biomarkers exhibit distinct performance characteristics across these validation criteria.

Table 3: Biomarker Performance Against Validation Criteria

| Validation Criterion | Definition | Exemplary Biomarkers | Performance Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plausibility | Biological plausibility and food specificity | Proline betaine (citrus), Tartaric acid (grape) [30] | Compound confirmed in food source and biological samples [30] |

| Dose-Response | Relationship between intake amount and biomarker level | Urinary sucrose/fructose (dietary sugars) [30] | Linear regression of consumed nutrients on potential biomarkers (R²: 0.32-0.53 for various vitamins) [10] |

| Time-Response | Kinetic profile including half-life and excretion timeline | Guanidoacetate (chicken intake) [30] | Characterization of pharmacokinetic parameters in controlled studies [7] |

| Robustness | Performance across diverse populations and conditions | Urinary nitrogen (protein intake) [30] | Validation in multiple free-living populations with different habitual diets [30] |

| Reliability | Consistency of measurement across repeated exposures | Serum carotenoids, tocopherols [10] | Demonstration of consistent performance in repeated feeding studies [10] |

The regression analysis approach used in the WHI feeding study provides a quantitative framework for biomarker evaluation, where linear regression of consumed nutrients on potential biomarkers yielded R² values ranging from 0.32 for lycopene to 0.53 for α-carotene, performing similarly to established energy and protein urinary recovery biomarkers [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of biomarker validation studies requires specific reagents, platforms, and methodologies. The following toolkit summarizes essential components for establishing a biomarker validation pipeline.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Biomarker Validation

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Validation Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Platforms | NMR spectrometers, LC-MS/MS systems, GC-MS systems | Metabolite profiling and quantification in biological samples [30] |

| Nutrition Software | ProNutra, Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) | Diet formulation, menu creation, and nutrient analysis [10] |

| Reference Standards | Certified metabolite standards, stable isotope-labeled internal standards | Compound identification and quantification accuracy [31] |

| Sample Collection | Standardized blood collection tubes, urine containers, temperature-controlled storage | Biological specimen integrity and pre-analytical consistency [31] |

| Data Analysis | Cross-validation algorithms, feature selection methods, statistical packages | Robust classification and performance evaluation [32] |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, Reactome, HMDB | Biological context and pathway analysis for candidate biomarkers [33] |

| Dihydrocapsaicin-d3 | Dihydro Capsaicin-d3 | Dihydro Capsaicin-d3, a deuterated capsaicinoid. For research applications only. Not for human consumption. For Research Use Only. |

| Mefenamic Acid D4 | Mefenamic Acid D4, MF:C15H15NO2, MW:245.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methodologies: Multi-Omics Integration and Pathway Analysis

The integration of multi-omics data represents a cutting-edge approach to enhance biomarker validation. Methods such as integrative Directed Random Walk (iDRW) incorporate pathway information to improve the biological relevance and predictive performance of biomarker panels [33]. This approach constructs directed gene-gene interaction graphs that reflect the impact of genomic variants on gene expression, creating more robust models for survival prediction in cancer studies [33].

The MultiP (Multi-Platform Precision Pathway) framework further extends this concept by developing clinical precision pathways that mimic real-world diagnostic processes. This framework introduces an "uncertain" class in classification models, allowing for multi-stage decision processes where individuals receive additional testing only when initial biomarkers provide inconclusive results [32]. This approach mirrors clinical reality and optimizes resource allocation in diagnostic pathways.

The multi-phase validation pathway from identification to real-world prediction represents a rigorous framework for establishing credible dietary biomarkers. Through controlled feeding studies, metabolomic profiling, and progressive validation in increasingly complex environments, researchers can develop biomarker panels with demonstrated utility for both research and clinical applications.

The future of biomarker validation lies in the intelligent integration of multi-omics data, the application of sophisticated computational methods, and the development of phase-appropriate validation strategies that balance scientific rigor with practical feasibility. As the field advances, this structured approach will continue to yield biomarkers that transform our understanding of diet-health relationships and enable more precise nutritional interventions.

Measurement error, though ubiquitous in biomedical research, is often unacknowledged in epidemiologic studies, leading to biased parameter estimates, loss of statistical power, and distorted relationships between variables [34]. In the specific context of biomarker development and validation, these errors present particular challenges for establishing accurate diet-disease associations and treatment effect estimates [35] [13]. Controlled feeding studies represent a crucial methodological approach for addressing these challenges by providing robust biomarker development and validation frameworks [35] [36]. This guide compares advanced statistical models designed to correct for measurement error and bias, evaluating their performance characteristics, implementation requirements, and applicability within biomarker research.

Comparative Analysis of Statistical Correction Methods

The table below summarizes five prominent statistical approaches for correcting measurement error and bias, highlighting their key applications and methodological requirements.

| Method | Primary Application | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Calibration [35] [34] | Correcting systematic error in self-reported dietary data | Gold-standard biomarker for a subset of dietary components | Simple implementation; useful for continuous covariates | Biomarkers only available for limited dietary components |

| Corrected LASSO [37] | Variable selection with high-dimensional biomarker data | Validation subset re-measured with precise method | Reduces false positives; handles high-dimensional data | Requires validation data; computationally intensive |

| Bootstrap Bias Correction [38] [39] | Correcting bias after data-driven biomarker cutoff selection | Internal bootstrap samples from original data | Reduces over-optimism from selection; general applicability | Computationally intensive; may not eliminate all bias |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) [38] [39] | Bias correction in treatment effect estimates | Dataset from a randomized clinical trial | Does not rely on asymptotic theory; provides full posterior | Requires careful selection of summary statistics and tolerance |

| Two-Stage Error Correction [40] [41] | Multilevel modeling; data streams with improved instruments | Initial error-prone data followed by precise measurements | Practical for complex models; handles sequentially improving data | Requires precise measurements at a known point in the data stream |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Regression Calibration in Controlled Feeding Studies

Controlled feeding studies provide a robust foundation for biomarker development and calibration. The typical protocol involves:

- Study Design: Participants are provided with a controlled diet that approximates their habitual food intake, as estimated from preliminary dietary assessments like food records or recalls [36]. For example, the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) feeding study provided 153 postmenopausal women with a 2-week controlled diet tailored to their usual intake [36].

- Biomarker Measurement: Throughout the feeding period, biological samples (e.g., blood, urine) are collected to measure potential nutritional biomarkers. Established recovery biomarkers, such as urinary nitrogen for protein intake and doubly labeled water for energy intake, serve as benchmarks for evaluation [35] [36].

- Calibration Model Development: Statistical models are developed to associate the objectively measured biomarker levels with the actual dietary intake from the controlled diet. This establishes a calibration equation that corrects for the systematic measurement error present in self-reported dietary data [35].

- Application in Association Studies: In the main cohort study (e.g., WHI), this calibration equation is applied to the self-reported data to obtain biomarker-calibrated intake estimates. These calibrated estimates are then used in disease association models, such as Cox proportional hazards models for cardiovascular disease risk, leading to more accurate hazard ratio estimations [35].

Corrected LASSO with Internal Validation Data

For high-dimensional biomarker data from multiplex assays, which are prone to high variability, a corrected LASSO procedure can be implemented using an internal validation subset:

- Data Structure Setup: The full study sample (n) has biomarkers measured by an error-prone multiplex assay ((Wi)). A randomly selected internal validation subset ((ξi = 1)) has biomarkers re-measured using a more precise "gold standard" method ((X_i)) [37].

- Bias Correction Term Estimation: Using the internal validation set, estimate the covariance matrix of the measurement error ((Σ{uu})) by comparing the error-prone measurements (Wi) to the precise measurements (X_i) [37].