Controlled Feeding Trials for Dietary Biomarker Discovery: Methodology, Validation, and Clinical Applications

This article explores the critical role of controlled feeding trials in discovering and validating objective dietary biomarkers.

Controlled Feeding Trials for Dietary Biomarker Discovery: Methodology, Validation, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of controlled feeding trials in discovering and validating objective dietary biomarkers. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational need for biomarkers beyond self-reported data, detailed methodological approaches for trial design and execution, strategies for troubleshooting common challenges, and rigorous multi-phase validation processes. The content synthesizes current consortium-led efforts and technological advances in metabolomics, providing a comprehensive guide for implementing these trials to enhance precision in nutritional science and clinical research.

The Critical Need for Objective Dietary Biomarkers in Nutrition Science

Limitations of Self-Reported Dietary Assessment Methods

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to nutritional epidemiology, enabling the investigation of links between diet and health outcomes. However, the field relies heavily on self-reported dietary instruments that introduce substantial measurement error, potentially compromising research validity and dietary recommendations. This document examines the limitations of these methods within the context of controlled feeding trials for dietary biomarker discovery, providing researchers with critical insights and methodological frameworks to advance nutritional science.

The subjective nature of self-reported intake data presents numerous challenges to obtaining accurate dietary exposure assessment. This limitation is increasingly being addressed through the development and validation of objective dietary biomarkers that can assess dietary consumption without the bias inherent in self-reported methods [1]. Controlled feeding studies represent a critical methodological bridge for identifying and validating these biomarkers, thereby strengthening the foundation of nutrition research.

Quantitative Limitations of Self-Reported Methods

Systematic Underreporting of Energy and Nutrients

Table 1: Documented Underreporting in Self-Reported Dietary Assessment

| Nutrient/Food Group | Degree of Underreporting | Factors Influencing Underreporting | Source Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Intake | 30-50% among overweight/obese individuals | Increases with BMI; weight concern | [2] |

| Protein Intake | 47% underestimation vs. urinary nitrogen biomarker | Weight loss context; less underreported than other macronutrients | [2] |

| Fruits & Vegetables | Moderate reliability (ICC*: 0.68) | Fair validity vs. objective measures (ICC: 0.53) | [3] |

| Grain Products | Fair reliability (ICC: 0.56) | Fair validity vs. objective measures (ICC: 0.41) | [3] |

| Meat & Alternatives | Fair reliability (ICC: 0.41) | Slight validity vs. objective measures (ICC: 0.34) | [3] |

*ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

Evidence consistently demonstrates systematic underreporting across various self-reported dietary instruments. The discrepancy between self-reported energy intake and energy expenditure measured by doubly labeled water is particularly well-documented, with underreporting increasing substantially with body mass index [2]. This systematic error is not uniform across nutrients; protein is typically less underreported compared to other macronutrients, suggesting selective reporting of perceived "healthy" foods [2].

Food Composition Variability Compounds Measurement Error

Table 2: Impact of Food Composition Variability on Intake Estimates

| Bioactive Compound | Variability in Food Content | Impact on Intake Estimation | Validation Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavan-3-ols | >2-fold variability in same foods | Large uncertainty in ranking high/low consumers | Biomarker calibration in EPIC-Norfolk study (n=18,684) | [4] |

| (-)-Epicatechin | >2-fold variability in same foods | Significant overlap in intake ranges between participants | Biomarker calibration in EPIC-Norfolk study | [4] |

| Nitrate | >2-fold variability in same foods | Difficulty identifying true consumption extremes | Biomarker calibration in EPIC-Norfolk study | [4] |

Food composition databases rely on single-point estimates (mean values) that mask the substantial natural variation in nutrient content between individual food items, even of the same type. This variability introduces considerable uncertainty when estimating actual nutrient intake, as demonstrated by research showing more than twofold differences in flavan-3-ols, (-)-epicatechin, and nitrate content between apparently identical foods [4]. When combined with self-reporting errors, this variability fundamentally challenges our ability to accurately assess dietary exposure.

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Discovery

Controlled Feeding Study Design for Biomarker Development

Controlled Feeding Study Workflow

Participant Recruitment and Baseline Assessment

- Target Population: Recruit 150+ participants representing the study population of interest, with oversampling for demographic diversity when needed [5]. For the Women's Health Initiative Nutrition and Physical Activity Assessment Study Feeding Study (NPAAS-FS), participants were postmenopausal women aged 50-80 [6].

- Eligibility Criteria: Exclude conditions affecting metabolism or specimen collection (e.g., diabetes, kidney disease, routine oxygen use) [5].

- Baseline Dietary Assessment: Administer a 4-day food record to capture habitual dietary patterns, food preferences, and eating behaviors [5]. Conduct standardized interviews to clarify portion sizes, brand preferences, preparation methods, and meal timing.

Individualized Diet Formulation

- Menu Development: Create individualized menus using diet analysis software (e.g., Nutrition Data System for Research, ProNutra) to approximate each participant's habitual diet [5].

- Energy Adjustment: Adjust calories based on estimated energy requirements using standard equations and previous calibration data. In NPAAS-FS, 73% of participants required upward calorie adjustments (average +335±220 kcal/day) to meet energy needs [5].

- Food Sourcing: Select foods with well-characterized nutrient composition using standardized sourcing and preparation protocols in a metabolic kitchen [5].

Controlled Feeding and Biospecimen Collection

- Feeding Period: Implement a 2-week controlled feeding period with all meals prepared in a metabolic kitchen [5].

- Specimen Collection: Collect fasting blood samples and 24-hour urine collections at beginning and end of feeding period [6] [5].

- Objective Measures: Implement doubly labeled water protocol for total energy expenditure and 24-hour urinary nitrogen for protein intake validation [5].

Biomarker Analytical Methods

Metabolomic Profiling

- Platform Selection: Employ liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for comprehensive metabolomic coverage [7].

- Targeted Analysis: Quantify specific nutrient biomarkers including:

- Carotenoids (α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, lycopene)

- Tocopherols (α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol)

- B vitamins (folate, B-12)

- Phospholipid fatty acids [5]

- Quality Control: Implement pooled quality control samples, standard reference materials, and batch correction algorithms.

Biomarker Validation Protocol

- Statistical Analysis: Perform linear regression of (ln-transformed) consumed nutrients on (ln-transformed) biomarker concentrations [5].

- Validation Criteria: Evaluate biomarkers using coefficient of determination (R²) values, with R² ≥0.36 considered acceptable for explaining intake variation [6].

- Performance Benchmarks: Compare novel biomarkers against established recovery biomarkers (doubly labeled water for energy: R²=0.53; urinary nitrogen for protein: R²=0.43) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Dietary Biomarker Discovery

| Category | Specific Reagents/Assays | Research Application | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Expenditure Biomarkers | Doubly labeled water (²H₂¹â¸O) | Objective measure of total energy expenditure | Accuracy: 1-2%; Precision: 7% for individuals [2] |

| Protein Intake Biomarkers | Urinary nitrogen analysis | Validation of protein intake assessment | Correlation with intake: R²=0.43 [5] |

| Vitamin Status Assays | Serum folate, vitamin B-12 | Biomarkers of vitamin intake | Explained variation: Folate R²=0.49; B-12 R²=0.51 [5] |

| Carotenoid Analysis | HPLC-based carotenoid profiling | Fruit and vegetable intake biomarkers | Explained variation: α-carotene R²=0.53; β-carotene R²=0.39 [5] |

| Fatty Acid Profiling | Phospholipid fatty acid analysis | Biomarkers of fatty acid intake | PUFA% energy: R²=0.27; weaker for SFA/MUFA [5] |

| Tetrahydrocurcumin | Tetrahydrocurcumin (CAS 36062-04-1) - For Research Use | High-purity Tetrahydrocurcumin, a key curcumin metabolite. Explore its research applications in oncology, metabolism, and more. For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

| Gingerdione | High-purity Gingerdione for research into ferroptosis, cancer mechanisms, and anti-inflammatory pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Biomarker Application in Nutritional Epidemiology

Regression Calibration for Measurement Error Correction

Regression Calibration for Error Correction

Advanced statistical methods enable the use of biomarkers to correct systematic measurement error in self-reported data. Regression calibration employs biomarker measurements to develop calibration equations that adjust self-reported intake for systematic bias [8]. This approach has been successfully applied in major cohort studies like the Women's Health Initiative to correct measurements of energy, protein, and sodium/potassium ratio [8].

The calibration process involves:

- Model Development: Regressing biomarker measurements on self-reported intake in feeding studies or biomarker substudies

- Equation Application: Using derived coefficients to calibrate self-reported data in the full cohort

- Association Analysis: Employing calibrated values in diet-disease association models

This method has demonstrated particular value in examining associations between sodium/potassium ratio and cardiovascular disease risk, revealing positive relationships with coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke that were obscured by measurement error in self-reported data [8].

Dietary Pattern Biomarkers

Beyond single nutrients, researchers have successfully developed biomarker signatures for overall dietary patterns. The NPAAS feeding study identified biomarker panels for Healthy Eating Index-2010 (HEI-2010) and alternative Mediterranean Diet (aMED) patterns that met prespecified criteria (cross-validated R² ≥36%) [6]. These pattern biomarkers provide objective measures of overall diet quality, overcoming limitations of pattern analysis based on error-prone self-reports.

Self-reported dietary assessment methods contain fundamental limitations that impede nutritional epidemiology and the development of evidence-based dietary guidance. Controlled feeding studies provide an essential platform for developing objective dietary biomarkers that overcome these limitations. The integration of metabolomic profiling, recovery biomarkers, and statistical calibration methods represents a paradigm shift toward more precise nutritional exposure assessment. Future research should focus on expanding the repertoire of validated biomarkers, particularly for whole dietary patterns, and implementing these tools in large-scale cohort studies to strengthen our understanding of diet-disease relationships.

Defining Dietary Biomarkers and Their Role in Precision Nutrition

Within nutritional science and the development of targeted therapies, the accurate assessment of dietary intake remains a formidable challenge. Current methodologies, including food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour recalls, are plagued by systematic and random measurement errors inherent to self-reported data [9]. Dietary biomarkers—objectively measurable indicators of food intake—present a transformative solution. These biomarkers, measured in biological specimens like blood and urine, reflect the true "bioavailable" dose of a dietary exposure, moving beyond mere consumption to biological impact [9]. Their discovery and validation are paramount for advancing Precision Nutrition, a framework that tailors dietary advice to individual characteristics such as genetics, metabolism, and microbiome composition [10]. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols for discovering dietary biomarkers within the context of controlled feeding trials, providing a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in this cutting-edge field.

Dietary Biomarker Discovery Workflow

The discovery and validation of robust dietary biomarkers require a systematic, multi-phase approach. The following workflow, formalized by initiatives such as the Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC), outlines this rigorous process from initial discovery to real-world application [7] [9].

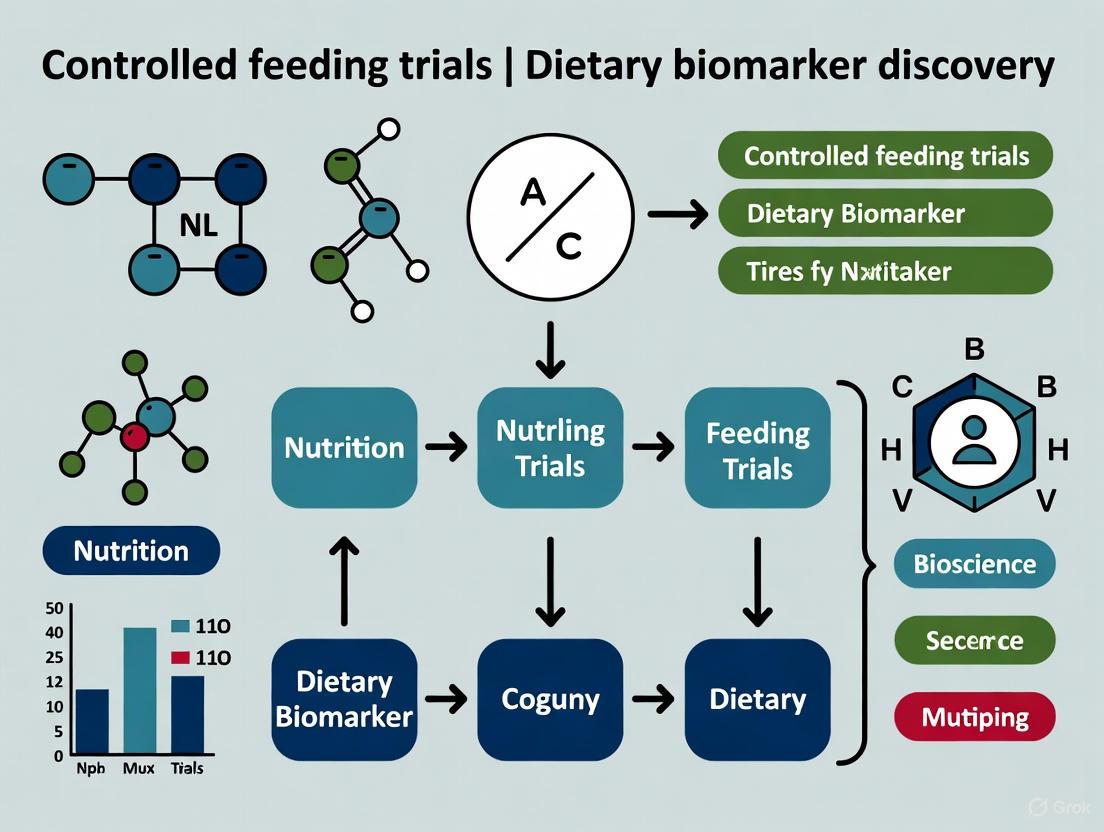

Diagram 1: Dietary biomarker discovery and validation workflow.

Core Principles for Validated Biomarkers

For a metabolite to be considered a valid dietary biomarker, it should fulfill several criteria beyond mere detectability. As proposed by Dragsted et al. and adopted by the DBDC, these principles include [9]:

- Plausibility: A biologically plausible connection must exist between the food component and the candidate biomarker.

- Dose-Response (DR) & Time-Response (Pharmacokinetics): A predictable relationship must be demonstrated between the amount of food consumed (dose) and the biomarker level, as well as its kinetics over time.

- Robustness, Reliability, and Analytical Performance: The biomarker must be stable, reliably measurable with high sensitivity and specificity using standard platforms like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and perform consistently across diverse populations and complex dietary backgrounds [9].

Experimental Protocols for Controlled Feeding Trials

Protocol 1: Phase 1 Discovery and Pharmacokinetic Studies

Objective: To identify candidate biomarker compounds and characterize their pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters following the consumption of a specific test food.

Materials:

- Participants: Healthy adult volunteers, recruited based on predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria [9].

- Test Foods: Pre-specified, commonly consumed foods (e.g., selected based on USDA MyPlate Guidelines), prepared in standardized portions [9].

- Biospecimen Collection: Blood collection tubes (e.g., EDTA for plasma), urine collection containers, equipment for processing and aliquoting (e.g., centrifuges, pipettes, cryovials).

- Analytical Platform: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) systems, preferably using Hydrophilic-Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) for broad metabolite capture [9].

Methodology:

- Pre-Intervention Baseline: Following an overnight fast, collect baseline fasting blood and urine samples from participants.

- Controlled Administration: Administer a single, known dose of the test food to participants.

- Intensive Pharmacokinetic Sampling: Collect serial blood and urine specimens at predetermined time points post-consumption (e.g., 30min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 6h, 8h, 24h) to capture the absorption, peak, and elimination phases of potential biomarkers [9].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Perform untargeted metabolomic analysis on all biospecimens using LC-MS.

- Data Analysis: Use high-dimensional bioinformatics to compare pre- and post-consumption metabolomic profiles. Identify significantly elevated compounds as candidate biomarkers. Model the PK parameters (e.g., C~max~, T~max~, AUC) for each candidate [7] [9].

Protocol 2: Phase 2 Evaluation in Varied Dietary Patterns

Objective: To evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of candidate biomarkers for identifying consumption of the target food against the background of different complex dietary patterns.

Materials: As in Protocol 1, with the addition of full menus representing different dietary patterns (e.g., Western, Mediterranean, Vegetarian).

Methodology:

- Dietary Intervention Design: Implement controlled feeding studies where participants are randomized to follow different dietary patterns for a set period (e.g., 2-4 weeks). One group receives the target food, while control groups do not.

- Biospecimen Collection: Collect fasting or timed biospecimens at regular intervals throughout the intervention.

- Biomarker Measurement: Analyze samples using targeted or untargeted metabolomics to quantify the levels of the candidate biomarkers.

- Statistical Evaluation: Assess the biomarker's ability to correctly classify consumers vs. non-consumers of the test food. Calculate performance metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) [7].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data from Biomarker Discovery Phases

| Study Phase | Primary Objective | Key Measured Parameters | Typical Sample Size (per group) | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Discovery & PK | Identify candidate biomarkers and their kinetics | C~max~ (peak concentration), T~max~ (time to peak), AUC (Area Under Curve), half-life | 10-20 healthy participants | List of candidate compounds with PK profiles |

| Phase 2: Evaluation | Test specificity in complex diets | Sensitivity, Specificity, AUC-ROC | 30-50 participants per dietary arm | Performance metrics for classifying food intake |

| Phase 3: Validation | Assess predictive power in free-living populations | Correlation coefficients with habitual intake, predictive accuracy | Hundreds of participants in observational cohorts | Validated biomarker for use in epidemiological studies [7] [9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful dietary biomarker research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, technologies, and methodologies. The following table catalogs essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Specifications & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | High-throughput, untargeted and targeted analysis of metabolites in biospecimens. The primary platform for biomarker discovery. | Hydrophilic-interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) for polar metabolites; reverse-phase LC for lipids [9]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for absolute quantification of metabolites; used to track specific nutrient metabolism. | Carbon-13 (^13^C) or Nitrogen-15 (^15^N) labeled compounds added to samples for calibration and recovery calculations. |

| Controlled Diets & Test Foods | Provide a precise and reproducible dietary exposure to eliminate confounding from self-reported intake. | Foods prepared in metabolic kitchens, with compositions verified by chemical analysis [7] [9]. |

| Biospecimen Collection Kits | Standardized collection, processing, and archiving of biological samples to preserve biomarker integrity. | EDTA tubes for plasma; cryovials for long-term storage in -80°C freezers; protocols for urine dilution and refractive index targeting [9]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Process raw metabolomic data, perform statistical analyses, and identify significant metabolite patterns. | Packages for peak alignment, compound identification using MS/MS libraries, and multivariate statistics (e.g., PCA, OPLS-DA). |

| Multi-Omics Data Integration Platforms | Combine metabolomic data with genomic, proteomic, and microbiomic data for a systems-level view. | AI and machine learning algorithms to predict individual glycemic responses and integrate food-polygenic variant interactions [10]. |

| (Rac)-Atropine-d3 | (Rac)-Atropine-d3, CAS:51-55-8, MF:C17H23NO3, MW:289.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isorhoifolin | Isorhoifolin (CAS 552-57-8) - High-Purity RUO Flavonoid | Isorhoifolin, a high-purity flavonoid for Research Use Only. Explore its antioxidant and cardiac research applications. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Application in Precision Nutrition and Therapeutic Development

The ultimate application of validated dietary biomarkers is in realizing the vision of precision nutrition, as illustrated by the following framework which integrates multi-omics data to deliver personalized dietary advice.

Diagram 2: Precision nutrition implementation framework.

Validated dietary biomarkers serve critical functions across research and clinical practice:

- Calibrating Self-Reported Data: Biomarkers provide an objective measure to correct for errors in dietary questionnaires, significantly improving the accuracy of nutritional epidemiology [9].

- Quantifying Compliance: In clinical trials for drug development, especially those where diet is a confounding factor (e.g., for metabolic diseases), biomarkers offer an unbiased method for monitoring participant adherence to dietary interventions [11].

- Understanding Interindividual Variability: Biomarkers are integral to multi-omics profiling that helps explain why individuals respond differently to the same foods. This is key for developing personalized dietary interventions for conditions like obesity and diabetes [10] [11].

- Identifying Novel Therapeutic Targets: Research into the neurobiological impact of diet, such as brain activity associated with "food preoccupation" under incretin-based therapies, can reveal new biomarker-driven targets for drug development [12].

The systematic discovery and validation of dietary biomarkers, as detailed in these application notes and protocols, are foundational to building a future where nutrition is a precise, personalized, and powerful component of health maintenance and disease therapy.

Diet is a complex exposure that significantly affects human health across the lifespan. The accurate assessment of dietary intake remains a fundamental challenge in nutritional epidemiology, largely due to the substantial measurement errors inherent in self-reported dietary data such as food frequency questionnaires and dietary recalls [6]. To address this limitation, the field has increasingly turned toward the discovery and validation of objective biomarkers that can reliably reflect intake of specific nutrients, foods, and overall dietary patterns [13] [7].

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) represents the first major coordinated effort to systematically improve dietary assessment through the discovery and validation of biomarkers for foods commonly consumed in the United States diet [13]. This multi-center initiative connects experts in nutrition, data science, and statistics with the shared goal of identifying objective measures that can inform individual dietary patterns and advance nutritional science [14]. The consortium's work is particularly framed within the context of controlled feeding trials, which provide the rigorous experimental conditions necessary for biomarker discovery and validation.

The DBDC Organizational Infrastructure and Mission

The DBDC operates through a collaborative network of research centers employing standardized protocols and shared data resources. The consortium's central mission is to significantly expand the list of validated biomarkers of intake for foods consumed in the United States diet, thereby enabling more precise investigations of how diet influences human health and chronic disease risk [13] [7]. This expansion is crucial for advancing the field of precision nutrition, which aims to provide individualized dietary recommendations based on objective measures rather than self-reported data alone.

The organizational structure of the DBDC facilitates the integration of diverse expertise across multiple disciplines, including nutrition, metabolomics, bioinformatics, and statistics [14]. This cross-disciplinary approach is essential for addressing the complex challenges inherent in dietary biomarker development, from the initial discovery phase to eventual application in large-scale epidemiological studies.

The Three-Phase Biomarker Development Framework

The DBDC has implemented a systematic, three-phase approach to biomarker discovery and validation that leverages controlled feeding studies as its foundational element. This rigorous framework ensures that candidate biomarkers undergo comprehensive evaluation before being recommended for use in research settings.

Phase 1: Discovery and Pharmacokinetic Characterization

In Phase 1, controlled feeding trial designs are implemented by administering test foods in prespecified amounts to healthy participants [13] [7]. This initial discovery phase employs metabolomic profiling of blood and urine specimens collected during the feeding trials to identify candidate compounds that may serve as biomarkers [15]. The controlled feeding environment allows researchers to characterize the pharmacokinetic parameters of candidate biomarkers associated with specific foods, including their appearance, peak concentration, and clearance rates in biological fluids [13].

The DBDC's feeding studies are designed to investigate specific food groups. For example, the Fruit and Vegetable Biomarker Discovery study focuses on identifying biomarkers for bananas, peaches, strawberries, tomatoes, green beans, and carrots [16]. These studies typically involve multiple test days where participants consume prescribed combinations of target foods while providing repeated biological samples, enabling researchers to track the temporal patterns of potential biomarker compounds [16].

Phase 2: Evaluation in Varied Dietary Patterns

Phase 2 assesses the performance of candidate biomarkers identified in Phase 1 using controlled feeding studies of various dietary patterns [13] [7]. This critical evaluation phase tests whether candidate biomarkers retain their specificity and sensitivity when the target food is consumed as part of different dietary backgrounds, rather than in isolation. The ability of a biomarker to accurately identify consumption of its associated food across diverse dietary contexts is essential for its utility in free-living populations where people consume complex mixtures of foods.

Phase 3: Validation in Observational Settings

Phase 3 represents the final validation step, where the performance of candidate biomarkers is evaluated in independent observational settings [13] [7]. This phase tests whether biomarkers can predict recent and habitual consumption of specific test foods under free-living conditions [15]. Successful validation in observational cohorts provides the final evidence needed to recommend a biomarker for use in nutritional epidemiology studies.

Throughout all three phases, data generated by the DBDC are archived in a publicly accessible database, serving as a valuable resource for the broader research community [13] [7]. This commitment to data sharing accelerates the pace of biomarker discovery and validation beyond the consortium itself.

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Discovery

Protocol 1: Fruit and Vegetable Biomarker Discovery

Objective: To identify biomarkers in blood and urine that provide specific information about intake of bananas, peaches, strawberries, tomatoes, green beans, and carrots [16].

Study Population: Healthy adults with BMI between 18.5-39.9, excluding those with gastrointestinal disorders, recent significant weight change, or use of certain medications that might interfere with metabolic responses [16].

Experimental Design:

- Screening: Initial telephone interview (15-20 minutes) followed by in-person screening visit (40-60 minutes) including body measurements, vital signs, and blood draw for eligibility assessment [16].

- Study Duration: Approximately 15 days conducted over 3 weeks, with 9 study visits including three extended test days lasting ~8 hours each [16].

- Test Meals: Participants consume three different combinations of fruits (strawberries, peaches, bananas) and three different combinations of vegetables (green beans, tomatoes, carrots) across three test days [16].

- Lead-in Diet: Participants receive two days' worth of food and beverages leading into each test day, with instructions to consume only the provided items during each test period [16].

- Sample Collection: On test days, participants provide 9 blood draws and multiple urine samples, with an additional blood draw and urine collection 24 hours post-test [16].

Compensation: Participants receive $250 upon completion of all study visits [16].

Protocol 2: Metabolomic Response to Ultra-Processed Dietary Patterns

Objective: To identify metabolomic markers that differentiate between dietary patterns high in versus void of ultra-processed foods according to NOVA classification [17] [18].

Study Design: Randomized, crossover, controlled feeding trial involving 20 healthy participants (mean age 31±7 years, BMI 22±11.6, 50% female) [17].

Dietary Interventions:

- UPF-DP: Dietary pattern containing 80% ultra-processed foods

- UN-DP: Unprocessed dietary pattern containing 0% ultra-processed foods

- Matching: Both diets matched for energy, macronutrients, total fiber, total sugar, and sodium

- Feeding Protocol: Diets presented at 200% of energy requirements and consumed ad libitum for two weeks per condition with no washout period [17]

Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Metabolite Profiling: Untargeted liquid chromatography with high resolution/tandem mass spectrometry

- Sample Types: EDTA plasma collected at end of each dietary period (week 2); 24-hour and spot urine collected at weeks 1 and 2

- Data Processing: Metabolites with <80% missing data and coefficients of variation <30% were assigned minimum detected values, scaled to median of 1, and log2-transformed [17]

- Statistical Analysis: Linear mixed models identified metabolites differing between UPF-DP and UN-DP, adjusted for trial, sequence, timepoint, and body weight changes, with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple comparison correction [17]

Quantitative Results from Metabolomic Studies

Table 1: Metabolomic Differences Between Ultra-Processed and Unprocessed Dietary Patterns

| Sample Type | Total Metabolites Measured | Differentially Abundant Metabolites | Consistently Different Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | 1,000 | 183 at week 2 | 20 across all sample types and timepoints |

| 24-hour Urine | 1,272 | 461 at weeks 1 and 2 | 20 across all sample types and timepoints |

| Spot Urine | 1,281 | 68 at weeks 1 and 2 | 20 across all sample types and timepoints |

Table 2: Metabolic Pathways Represented by Consistent Metabolomic Biomarkers

| Metabolic Pathway | Number of Metabolites | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamate metabolism | 1 | Not specified |

| Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 1 | Not specified |

| Benzoate metabolism | 2 | Not specified |

| Methionine, cysteine, SAM and taurine metabolism | 2 | Not specified |

| Secondary bile acid metabolism | 2 | Not specified |

| Fatty acid dicarboxylate | 1 | Not specified |

| Plant-food components | 2 | Not specified |

| Unannotated | 9 | Not specified |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

DBDC Three-Phase Biomarker Development Pipeline

Fruit and Vegetable Biomarker Study Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography with High Resolution/Tandem Mass Spectrometry | Untargeted metabolomics platform | Comprehensive profiling of metabolites in biological samples; enables detection of thousands of compounds simultaneously [17] |

| EDTA Plasma Collection Tubes | Standard blood collection tubes with EDTA anticoagulant | Preservation of blood samples for metabolomic analysis; prevents coagulation and maintains sample integrity [17] |

| 24-hour Urine Collection Containers | Sterile, large-volume containers | Quantitative collection of all urine produced over 24-hour period for comprehensive metabolomic profiling [6] |

| Metabolon Reference Library | Commercial metabolite database | Annotation and identification of detected metabolites using authentic standards [17] |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Stable isotope-labeled water (²H₂¹â¸O) | Objective assessment of total energy expenditure as biomarker of energy intake in validation studies [6] |

| Controlled Feeding Study Materials | Standardized food preparation facility | Provision of precisely controlled test meals and diets; essential for biomarker discovery phase [16] |

| Liquid Handling Systems | Automated pipetting systems | Precise and reproducible processing of biological samples for high-throughput metabolomic analyses |

| Ibandronate | Ibandronate, CAS:114084-78-5, MF:C9H23NO7P2, MW:319.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| alpha-Estradiol | 17alpha-Estradiol Research Grade|RUO |

Analytical Framework and Statistical Approaches

The DBDC employs sophisticated statistical methods to handle the high-dimensional data generated by metabolomic platforms and to address the challenge of dietary measurement error in association studies.

Regression Calibration for Measurement Error Correction

A key application of dietary biomarkers is in regression calibration methods to correct for systematic measurement error in self-reported dietary data [19]. This approach is particularly important in association studies examining relationships between dietary intake and chronic disease risk, where measurement error can substantially attenuate or distort true associations.

The statistical framework involves using biomarkers developed through controlled feeding studies to calibrate self-reported intake measures, thereby providing more accurate estimates of diet-disease associations [19]. This method has been successfully applied to examine associations between sodium/potassium ratio and cardiovascular disease risk, revealing significant positive associations with coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary death, ischemic stroke, and total cardiovascular disease incidence [19].

Biomarker Signature Development for Dietary Patterns

Beyond biomarkers for individual foods, the DBDC approach also supports the development of biomarker signatures for overall dietary patterns. Research has demonstrated that panels of nutritional biomarkers can identify signatures associated with established dietary patterns such as the Healthy Eating Index-2010 (HEI-2010) and alternative Mediterranean diet (aMED) [6].

This methodology typically involves two stages:

- Discovery: Biomarker identification using biospecimens from controlled feeding studies where dietary intake is known

- Calibration: Application of discovered biomarkers in regression models to correct measurement error in dietary self-reports from observational studies [6]

The successful application of this approach has been demonstrated in studies of postmenopausal women, where biomarker-calibrated measurements showed improved predictive validity for diet-disease associations compared to self-report data alone [6].

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium represents a transformative initiative in nutritional science, addressing fundamental limitations in dietary assessment through rigorous biomarker discovery and validation. The consortium's systematic three-phase approach, grounded in controlled feeding trials and advanced metabolomic technologies, provides a robust framework for expanding the repertoire of validated dietary biomarkers.

As the DBDC continues to identify and validate biomarkers for an increasing number of foods and dietary patterns, its contributions will significantly advance precision nutrition and enhance our understanding of diet-health relationships. The consortium's commitment to data sharing through publicly accessible databases ensures that its findings will benefit the broader research community and ultimately support the development of more effective, evidence-based dietary recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention.

The Three-Phased Approach to Biomarker Discovery and Validation

The discovery and validation of robust biomarkers are fundamental to advancing nutritional science, particularly in the context of controlled feeding trials. Biomarkers serve as objective indicators of biological processes, pathogenic states, or pharmacological responses to therapeutic intervention, and in nutrition research, they provide crucial insights into dietary exposure, nutritional status, and physiological responses to dietary interventions [20] [21]. The development of these biomarkers follows a structured pathway designed to ensure that the final biomarkers are clinically relevant, reproducible, and actionable.

This pathway is typically described as being divided into three consecutive phases: the discovery phase, the verification phase, and the validation phase [20] [21]. The process is characterized by a funnel approach, where a large number of candidate biomarkers identified in the discovery phase are progressively narrowed down through rigorous, iterative testing to a few analytically validated biomarkers. Within nutrition research, this framework is especially valuable for linking specific dietary patterns, such as those high in ultra-processed foods, to measurable molecular changes, thereby moving beyond traditional self-reported dietary assessment methods [17]. This article details the experimental protocols and considerations for each phase within the specific context of controlled feeding trials for dietary biomarker discovery.

The Three Phases of Biomarker Development

Phase 1: Discovery

The discovery phase is the initial, hypothesis-generating stage focused on the untargeted identification of a large number of candidate biomarkers [20]. In controlled feeding trials, this involves in-depth molecular profiling to pinpoint metabolites or proteins that differ significantly between intervention groups, such as a diet high in ultra-processed foods (UPF-DP) versus an unprocessed diet (UN-DP) [17].

Experimental Protocol for Metabolomic Discovery

- Sample Collection: Biological samples (e.g., EDTA plasma, 24-hour urine, spot urine) are collected from participants at the end of each dietary intervention period in a randomized, crossover, controlled feeding trial [17].

- Sample Preparation: Proteins are precipitated, and samples are diluted appropriately with solvent for analysis.

- Data Acquisition: Profiling is performed using untargeted liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS/MS). This platform provides accurate mass measurements for putative identification.

- Data Processing: Raw data are processed using software (e.g., Progenesis QI, XCMS) for peak picking, alignment, and normalization. Metabolites are annotated against reference libraries (e.g., Metabolon's library) and authentic standards.

- Statistical Analysis: Data are log2-transformed. Linear mixed models are used to identify metabolites that differ significantly between dietary groups, adjusting for covariates like trial sequence, timepoint, and body weight change. A false discovery rate (FDR) correction is applied.

Table 1: Representative Data from a Discovery Phase Feeding Study [17]

| Sample Type | Total Metabolites Measured | Metabolites Differing Between Diets | Key Differentiating Sub-pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ~1,000 | 183 | Glutamate metabolism, ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, benzoate metabolism |

| 24-hour Urine | ~1,270 | 461 | Methionine, cysteine, SAM and taurine metabolism, secondary bile acid metabolism, plant-food components |

| Spot Urine | ~1,280 | 68 | Fatty acid dicarboxylate, benzoate metabolism |

Phase 2: Verification

The verification phase focuses on confirming that the abundances of the target candidate biomarkers are consistently and significantly different between the dietary groups using quantitative measurements [20]. This phase acts as a confirmatory step to eliminate false positives from the discovery phase.

Experimental Protocol for Targeted Verification

- Assay Development: Develop a targeted mass spectrometry-based assay, typically using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. This method offers high sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy for a predefined set of metabolites [20].

- Synthetic Standards: Source or synthesize stable-isotope-labeled internal standards for each candidate biomarker. These are spiked into every sample at a known concentration to correct for sample preparation losses and instrument variability.

- Sample Analysis: Re-analyze a subset of the original samples (or a similar, independent set from the same trial) using the targeted MRM assay. The confident detection is determined by the co-elution and similarity of the MS/MS fragment pattern compared to the synthetic standards [20].

- Data Analysis: Perform power analysis to determine the sample size sufficient to confirm the differential abundance of the candidates. The number of samples in this phase is larger than in discovery and is often in the dozens to hundreds [20].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Biomarker Phases in Feeding Trials

| Parameter | Discovery Phase | Verification/Validation Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Hypothesis generation; identify candidates | Confirm and quantify candidates |

| Approach | Untargeted profiling | Targeted analysis |

| Typical Platform | LC-HRMS/MS | LC-MRM/MS |

| Number of Analytes | Thousands | Tens to a few hundred |

| Sample Number | Limited (e.g., 20-30 participants) | Dozens to hundreds |

| Statistical Emphasis | Fold-change, multivariate analysis | Power analysis, confidence intervals |

| Use of Internal Standards | Limited | Essential (stable isotope-labeled) |

Phase 3: Validation

The validation phase is the final stage, which confirms the utility and robustness of the biomarker assay by analyzing samples from an expanded or fully independent cohort [20] [21]. The goal is to demonstrate that the biomarker performs reliably in a broader population.

Experimental Protocol for Analytical Validation

- Cohort Selection: Secure a large, independent set of samples from a new controlled feeding trial or an observational study with detailed dietary records. This cohort should represent the target population and include relevant control groups [20].

- High-Throughput Analysis: Perform targeted MS analysis on the large sample set. The analytical method must be optimized for high throughput and robustness.

- Assay Validation: Determine key analytical performance parameters for the biomarker assay, including:

- Precision: Repeatability (within-day variability) and reproducibility (day-to-day variability).

- Accuracy: Recovery of spiked analytes.

- Sensitivity: Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ).

- Specificity: Ability to measure the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components.

- Clinical/Biological Validation: Statistically evaluate the biomarker's performance in classifying the dietary exposure or nutritional status in the new, larger cohort.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the three-phase approach relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for a metabolomics-based dietary biomarker study.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolomic Biomarker Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., 13C, 15N) | Spiked into samples to correct for matrix effects and analytical variability; essential for accurate quantification in targeted MS (verification/validation) [20]. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Pure compounds used to confirm the identity of metabolites by matching retention time and fragmentation spectrum; crucial for annotation in discovery and verification [17]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pools | A pooled sample created by combining a small aliquot of every sample in the study; analyzed repeatedly throughout the analytical batch to monitor instrument stability and data quality [20]. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Predefined, step-by-step protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis; ensures uniformity, quality, and reproducibility across the study [20]. |

| Reference Spectral Libraries (e.g., Metabolon, NIST, HMDB) | Databases of known mass spectra and retention indices used to putatively identify metabolites from untargeted MS data in the discovery phase [17]. |

| Dobutamine | Dobutamine |

| N,N-Dimethylarginine | N,N-Dimethylarginine|ADMA|NOS Inhibitor |

Critical Experimental Design Considerations

Cohort Selection and Statistical Power

Critical to making appropriate inference is the selection of samples representative of both the intervention group and the control population from which the cases are drawn [20]. In controlled feeding trials, proper randomization, crossover designs, and sample matching (e.g., for age, BMI, baseline health status) improve comparative analysis and reduce the number of samples required to achieve proper statistical power [20] [17]. Underpowered studies are a primary cause of failure in biomarker development [20]. A power analysis should be performed before the verification and validation phases to determine the minimum number of samples needed to detect a biologically meaningful fold-change, given the expected technical and biological variability [20].

Blinding, Randomization, and Quality Control

To reduce or eliminate biases due to expectations, both researchers and participants should be blinded to the dietary assignment where possible [20]. The order of sample analysis by MS should be randomized to avoid batch effects. Implementing rigorous quality control (QC) is non-negotiable. This includes using QC pools to monitor instrument performance and applying pre-defined criteria for data cleaning, such as removing metabolites with high rates of missing data or poor measurement precision (e.g., >30% coefficient of variation) [20] [17].

The three-phased approach to biomarker discovery and validation provides a rigorous, structured framework that is directly applicable to controlled feeding trials in nutritional science. By moving from untargeted discovery to targeted verification and final analytical validation, researchers can systematically identify and confirm molecular indicators of dietary intake. Adherence to best practices in experimental design—including careful cohort selection, blinding, randomization, and stringent quality control—is paramount to ensuring that the resulting biomarkers are robust, reproducible, and capable of providing meaningful insights into the relationships between diet and health.

Metabolomics and Bioinformatics as Foundational Technologies

Metabolomics has emerged as a powerful analytical technology for comprehensively characterizing small molecule metabolites in biological systems, providing a direct readout of cellular activity and physiological status. When coupled with bioinformatics, these foundational technologies enable unprecedented insights into metabolic pathways and biological mechanisms. Within nutritional science, metabolomics is particularly valuable for discovering dietary biomarkers that objectively reflect food intake, overcoming limitations of traditional self-reported dietary assessment methods. The integration of controlled feeding studies with advanced computational approaches creates a robust framework for identifying, validating, and implementing biomarkers that accurately track specific dietary patterns and nutritional interventions. This application note details experimental protocols and analytical workflows for applying metabolomics and bioinformatics technologies within controlled feeding trials for dietary biomarker discovery.

Experimental Design for Dietary Biomarker Discovery

Controlled Feeding Trial Framework

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) has established a systematic 3-phase approach for dietary biomarker discovery and validation within controlled feeding studies [15]. This framework ensures rigorous evaluation of candidate biomarkers across varying conditions:

Phase 1: Biomarker Identification

- Administration of test foods in prespecified amounts to healthy participants under controlled conditions

- Metabolomic profiling of blood and urine specimens collected during feeding trials

- Characterization of pharmacokinetic parameters of candidate biomarkers

- Identification of compounds with appropriate sensitivity and specificity

Phase 2: Biomarker Evaluation

- Assessment of candidate biomarkers' ability to identify individuals consuming biomarker-associated foods

- Utilization of controlled feeding studies with various dietary patterns

- Determination of detection thresholds and inter-individual variability

Phase 3: Biomarker Validation

- Evaluation of candidate biomarkers' predictive validity for recent and habitual consumption

- Testing in independent observational settings

- Verification of performance in free-living populations

Sample Size Considerations

Table 1: Recommended Sample Sizes for Controlled Feeding Trials

| Study Phase | Participants | Duration | Control Group | Biological Replicates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 15-30 | 1-3 days | Required | 3-5 collections per subject |

| Phase 2 | 30-50 | 1-2 weeks | Multiple arms | Weekly collections |

| Phase 3 | 100+ | 1-6 months | Required | Pre/post intervention |

Metabolomics Workflow: From Sample to Data

Sample Preparation Protocol

Based on established protocols for global metabolomics by LC-MS, the following procedures ensure high-quality samples for biomarker discovery [22]:

Plasma/Serum Processing:

- Collect blood samples in EDTA-containing tubes

- Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C within 30 minutes of collection

- Aliquot plasma/serum into cryovials and store at -80°C

- Deproteinize using ice-cold acetonitrile (2:1 ratio) in 96-well plates

- Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 15 minutes

- Transfer supernatant for LC-MS analysis

Urine Processing:

- Collect mid-stream urine in sterile containers

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove debris

- Aliquot supernatant and store at -80°C

- Dilute 1:5 with ultrapure water prior to analysis

Quality Control Measures:

- Include pooled quality control (QC) samples from all study samples

- Process QC samples throughout analytical batch to monitor instrument performance

- Implement internal standards prior to extraction to account for procedural variability

LC-MS Analysis for Metabolite Profiling

The untargeted metabolomics protocol utilizes liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry for comprehensive metabolite coverage [23]:

Chromatographic Conditions: Table 2: LC-MS Parameters for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Parameter | Reverse Phase (C18) | HILIC |

|---|---|---|

| Column | Waters HSS T3 (100×2.1mm, 1.7µm) | BEH Amide (100×2.1mm, 1.7µm) |

| Mobile Phase A | 0.1% formic acid in water | 5mM NHâ‚„OAc, 0.05% FA in water |

| Mobile Phase B | 100% acetonitrile | 100% acetonitrile |

| Gradient | 1-99% B over 15 min | 99-1% B over 15 min |

| Flow Rate | 0.3 mL/min | 0.3 mL/min |

| Column Temperature | 40°C | 40°C |

| Injection Volume | 2-5 μL | 2-5 μL |

Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- Instrument: High-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., TripleTOF 5600+, Orbitrap)

- Polarity: Positive and negative ion modes

- Mass Range: 50-1200 m/z

- Source Temperature: 500°C

- Ion Spray Voltage: ±5500 V

- Collision Energy: 10-40 eV

- Data Acquisition: Full scan with information-dependent acquisition (IDA) of MS/MS spectra

Bioinformatics Data Processing Pipeline

Raw Data Processing Workflow

Metabolomics data processing converts raw instrumental data into meaningful biological information through a multi-step computational workflow [24]:

Data Preprocessing Steps:

- Format Conversion: Convert vendor-specific files to open formats (mzML, mzXML) using MSConvert [25]

- Peak Detection: Identify chromatographic peaks using algorithms such as XCMS or MZmine [24]

- Retention Time Correction: Align peaks across samples to correct for retention time shifts

- Peak Alignment: Group corresponding peaks across all samples

- Peak Integration: Quantify peak areas for each metabolite feature

- Compound Identification: Annotate metabolites using accurate mass, MS/MS fragmentation, and database matching

Metabolite Identification and Annotation

Metabolite identification follows the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) guidelines with four confidence levels [24]:

- Level 1: Identified metabolites (matched to authentic standard using retention time and MS/MS)

- Level 2: Putatively annotated compounds (characteristic fragmentation spectra without RT match)

- Level 3: Putatively characterized compound classes (based on physicochemical properties)

- Level 4: Unknown compounds (distinct m/z signal without annotation)

Key Databases for Metabolite Annotation:

- Human Metabolome Database (HMDB)

- METLIN

- MassBank

- LipidMaps (for lipidomics)

- KEGG (for pathway analysis)

Statistical Analysis and Biomarker Validation

Multivariate Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis identifies differentially abundant metabolites between dietary intervention groups:

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalization using probabilistic quotient normalization or internal standards

- Pareto or unit variance scaling

- Log transformation to approximate normal distribution

Multivariate Analysis:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for unsupervised pattern recognition

- Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) for supervised classification

- Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores to identify significant metabolites

Validation Methods:

- Cross-validation (7-fold) to assess model robustness

- Permutation testing (n=200-1000) to prevent overfitting

- Random Forest analysis for feature selection

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis for diagnostic performance

Biomarker Validation Framework

The statistical framework for biomarker validation in time-course metabolomic data includes [26]:

- Smoothing Splines Mixed Effects (SME) Model: Treats longitudinal measurements as smooth functions of time

- Functional Test Statistic: Detects between-group differences across time points

- Non-parametric Bootstrap: Assesses statistical significance while controlling false discovery rate

Table 3: Statistical Criteria for Biomarker Validation

| Parameter | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Fold Change | >1.5 or <0.67 | Biological relevance |

| VIP Score (OPLS-DA) | >1.0 | Contribution to group separation |

| p-value (Mann-Whitney) | <0.05 | Statistical significance |

| FDR | <0.05 | Multiple testing correction |

| AUC (ROC) | >0.8 | Diagnostic performance |

Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Pathway Mapping and Interpretation

Bioinformatics tools enable the interpretation of metabolite changes in the context of metabolic pathways:

Key Metabolic Pathways in Nutritional Studies:

- Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle: Central energy metabolism, responsive to carbohydrate intake

- Amino Acid Metabolism: Reflects protein intake and nitrogen balance

- Fatty Acid Metabolism: Indicators of lipid consumption and processing

- Linoleic and α-Linolenic Acid Metabolism: Essential fatty acid status [25]

- Glycerophospholipid Metabolism: Membrane lipid composition

- Bile Acid Metabolism: Gut microbiome-host co-metabolism

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Metabolomics in Dietary Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Prevents coagulation and preserves metabolite stability | BD Vacutainer K2EDTA |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | Low contamination mobile phases for LC-MS | Fisher Optima LC/MS, Honeywell LC-MS Grade |

| Stable Isotope Internal Standards | Quantification and quality control | Cambridge Isotopes, Sigma-Isotrace |

| 96-well Protein Precipitation Plates | High-throughput sample preparation | Waters 96-well Protein Precipitation Plates |

| C18 and HILIC Columns | Complementary chromatographic separations | Waters HSS T3, BEH Amide |

| Quality Control Materials | Instrument performance monitoring | NIST SRM 1950 (Metabolites in Plasma) |

| Database Subscriptions | Metabolite identification and pathway analysis | HMDB, METLIN, KEGG |

| Carnitine Chloride | Carnitine Chloride, CAS:461-05-2, MF:C7H16NO3.Cl, MW:197.66 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Paracetamol-d4 | Paracetamol-d4, CAS:64315-36-2, MF:C8H9NO2, MW:155.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bioinformatics Software Tools

MetaboAnalystR 4.0 provides a comprehensive pipeline for LC-MS/MS raw spectral processing to functional interpretation [27]. Key features include:

- Auto-optimized peak picking parameters based on regions of interest

- MS/MS spectral deconvolution for DDA and DIA data

- Compound annotation against ~1.5 million MS2 reference spectra

- Functional interpretation via mummichog algorithm for pathway analysis

- Integration with statistical analysis and visualization

Additional Bioinformatics Resources:

- XCMS Online (cloud-based metabolomics data processing)

- MZmine 3 (modular data processing platform)

- CyVerse (cyberinfrastructure for omics data analysis)

- GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking)

Application in Nutritional Research: Case Example

A recent study investigating Generalized Ligamentous Laxity (GLL) demonstrates the application of metabolomics for biomarker discovery [25]. The researchers employed:

- Sample Collection: 65 GLL patients and 35 healthy controls

- Analysis Platform: UPLC-HRMS with positive and negative ionization modes

- Data Processing: XCMS for peak detection and alignment

- Statistical Analysis: OPLS-DA, random forest, and binary logistic regression

- Biomarker Identification: Hexadecanamide (AUC=0.907) as a diagnostic biomarker

- Pathway Analysis: Altered α-linolenic acid and linoleic acid metabolism in GLL

This case study exemplifies the complete workflow from sample collection to biological interpretation, highlighting the power of integrated metabolomics and bioinformatics approaches.

Metabolomics and bioinformatics technologies provide an indispensable foundation for advancing nutritional science through dietary biomarker discovery. The controlled feeding trial framework establishes rigorous conditions for identifying and validating intake biomarkers, while advanced LC-MS platforms enable comprehensive metabolite profiling. Bioinformatics tools transform complex raw data into biologically meaningful information through sophisticated processing algorithms, statistical analysis, and pathway mapping. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will enhance our understanding of diet-health relationships and enable more precise nutritional recommendations and interventions. The integration of standardized protocols, quality control measures, and computational approaches outlined in this application note provides a roadmap for researchers pursuing dietary biomarker discovery.

Designing and Implementing Controlled Feeding Trials: A Methodological Deep Dive

In the field of dietary biomarker discovery, controlled feeding trials are essential for establishing a causal link between dietary intake and measurable biological compounds. The integrity of this research hinges on selecting an appropriate trial design, primarily choosing between parallel and crossover structures. This article details the application, statistical considerations, and practical protocols for these two fundamental designs within the context of nutritional biomarker studies.

Core Design Principles and Comparison

Definition and Rationale

- Parallel Group Design: Participants are randomly allocated to one of two or more treatment groups. Each group receives a different intervention (e.g., a specific diet), and outcomes are measured and compared between these distinct groups at the end of the study period [28] [29].

- Crossover Design: Each participant receives multiple interventions in a sequentially random order, separated by a "washout" period. This design allows for within-participant comparisons, as each individual acts as their own control [30].

The intuitive appeal of the crossover design lies in its increased efficiency, as treatment comparisons are made within patients rather than between different patients [30].

Quantitative Comparison of Design Characteristics

Table 1: Key characteristics of parallel versus crossover designs

| Characteristic | Parallel Design | Crossover Design |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Allocation | Each participant receives only one intervention. | Each participant receives all interventions in sequence. |

| Comparison Type | Between-group comparison. | Within-participant comparison. |

| Sample Size Requirement | Larger for equivalent statistical power. | Smaller; can require approximately half the participants of a parallel trial for the same power [30]. |

| Ethical & Economic Impact | More participants receive a potentially less efficacious treatment; higher cost [30]. | Fewer participants exposed to inferior treatments; lower cost per participant [30]. |

| Primary Concern | Inter-individual variability can obscure treatment effects. | Carryover effects between periods; requires an adequate washout [29]. |

| Risk of Attrition | Lower risk of data loss. | Higher risk; dropouts lead to loss of data for all intervention periods [29]. |

| Suitability for Biomarker Studies | Ideal for long-term interventions or when a washout is impractical (e.g., biomarkers with long half-lives). | Highly efficient for studying short-term metabolic responses to foods [31] [32]. |

Application in Dietary Biomarker Discovery

Empirical Evidence and Concordance

Evidence from meta-analyses shows that crossover designs contribute to evidence in approximately a fifth of systematic reviews. Furthermore, the results from crossover and parallel trials on the same clinical questions tend to agree well (effect sizes correlate at rho = 0.72), although there is a trend for more conservative treatment effect estimates in parallel arm trials [33]. This supports the validity of using the more efficient crossover design in nutritional research.

Design-Specific Considerations for Biomarker Research

- Washout Period Determination: In crossover studies, the washout period must be long enough for the biological effects and biomarkers from the previous dietary intervention to return to baseline. This duration depends on the pharmacokinetics of the target food metabolites [29]. For example, a study investigating urinary metabolite biomarkers may only require a few days between interventions [32], whereas a study examining longer-term adaptations of the gut microbiome may require a much longer washout.

- Minimizing Period Effects: Changes in participant behavior, seasonality, or laboratory procedures over time can introduce period effects. Randomizing the order of interventions helps mitigate this bias.

- Precision and Dietary Collinearity: In whole-diet interventions, changing one dietary component can lead to compensatory changes in others, a problem known as dietary collinearity. Feeding trials, whether parallel or crossover, allow for quantification and control of this collinearity by providing all food to participants [29]. The MAIN Study, which provided all meals to free-living participants, is an excellent example of a design that ensures high adherence and precision for biomarker discovery [32].

Experimental Protocols for Controlled Feeding Trials

Protocol for a Parallel Group Feeding Trial

The following protocol is adapted from the PREVENTOMICS trial, a double-blinded randomized intervention investigating biomarker-based nutrition plans for weight loss [28].

- Participant Recruitment and Screening: Recruit adults meeting specific inclusion criteria (e.g., age 18-65, BMI ≥27 but <40 kg/m²). Exclude individuals with conditions or medications that could interfere with biomarker metabolism, or with disordered eating patterns to ensure safety and compliance [29] [32].

- Baseline Assessment and Randomization:

- Collect baseline data: anthropometrics, blood for clinical chemistry, biospecimens for baseline biomarker levels.

- Assess habitual diet via a 4-day food record or 24-hour recalls.

- Randomize participants in a 1:1 ratio to intervention or control group using a computer-generated sequence.

- Diet Formulation and Delivery:

- Intervention Group: Develop personalized meals based on the participant's metabolic cluster. Meals are prepared and provided for 6 days a week.

- Control Group: Develop standardized meals following general dietary recommendations, matched for energy content.

- Deliver all meals and beverages to participants in a blinded fashion, using similar-looking packaging to maintain blinding.

- Intervention Period:

- The intervention lasts for 10 weeks.

- Provide concomitant behavioral support via electronic push notifications (personalized for the intervention group, generic for the control).

- Outcome Measurement:

- The primary outcome (e.g., change in fat mass) and secondary outcomes (e.g., weight, body composition, fasting blood glucose, lipid profile, inflammatory biomarkers) are measured at the end of the 10-week period.

- Collect biospecimens (blood, urine) for targeted biomarker analysis.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Analyze the effect of the intervention on the primary outcome using linear mixed models, adjusting for baseline values.

Protocol for a Crossover Feeding Trial

This protocol is modeled after the MAIN Study, which was designed to discover and validate urinary metabolite biomarkers of food intake in a real-world context [32].

- Participant Recruitment and Screening: Recruit healthy participants willing to consume provided diets. Exclude based on medical conditions, medications, or high-level athletic activity [32].

- Randomization and Menu Sequence:

- Randomly assign participants to a sequence of menu plans. For example, in a two-period crossover, randomize to sequence A-B or B-A.

- Design menu plans to emulate real-world eating patterns and include target foods for biomarker discovery.

- Intervention Periods and Washout:

- Each experimental period typically lasts 1-3 weeks. The MAIN Study used 3-day menu plans [32].

- Separate periods with an adequate washout (e.g., several days to weeks) to allow biomarker levels to return to baseline.

- Diet Delivery and Consumption:

- Provide participants with all foods and drinks for the duration of each experimental period.

- Participants prepare and consume meals in their own homes as free-living individuals, which increases the real-world applicability of the findings.

- Biospecimen Collection:

- Laboratory and Statistical Analysis:

- Analyze urine samples using mass spectrometry-based metabolomics to identify candidate biomarkers.

- Use linear mixed models for statistical analysis, with participant included as a random effect to account for the within-individual correlation inherent in the crossover design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for controlled feeding trials in biomarker discovery

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Diets | Precisely defined interventions to isolate the effect of specific foods or nutrients on biomarker levels. | The Women's Health Initiative Feeding Study provided individually tailored menus to mimic participants' habitual diets [5]. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | The gold standard biomarker for total energy expenditure, used to validate energy intake and under-reporting. | Used as an objective recovery biomarker for energy in the WHI feeding study [5]. |

| 24-Hour Urine Collection | Allows for the measurement of urinary recovery biomarkers, such as nitrogen (for protein intake) or specific food metabolites. | Urinary nitrogen was used to calibrate self-reported protein intake [5]. The MAIN Study used spot urine for metabolite discovery [32]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | A core analytical platform for metabolomics, enabling the untargeted or targeted discovery and quantification of dietary biomarkers in biospecimens. | Used to profile urine specimens and identify candidate biomarkers in controlled feeding studies [31] [32]. |

| Validated Biomarker Assays | Commercially available or in-house developed kits for measuring specific nutritional biomarkers (e.g., carotenoids, vitamins, fatty acids). | Serum carotenoids, tocopherols, folate, and vitamin B-12 were evaluated as concentration biomarkers in the WHI cohort [5]. |

| Dietary Assessment Software | Tools for analyzing food records, designing nutritionally balanced menus, and ensuring dietary prescriptions are met. | The Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) and ProNutra software were used in the WHI and MAIN studies [32] [5]. |

| Urethane-d5 | Urethane-d5, CAS:73962-07-9, MF:C3H7NO2, MW:94.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Valproic acid-d6 | Valproic acid-d6, CAS:87745-18-4, MF:C8H16O2, MW:150.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between parallel and crossover designs is a fundamental step in planning a controlled feeding trial for dietary biomarker discovery. While the crossover design offers superior statistical power and efficiency for studying short-term metabolic responses, the parallel design remains the pragmatic choice for long-term interventions or when a sufficient washout cannot be guaranteed. By adhering to the detailed protocols and considerations outlined in this article, researchers can optimize their trial design to robustly discover and validate objective biomarkers that advance the field of precision nutrition.

Domiciled, Partial-Domiciled, and Non-Domiciled Feeding Settings

Controlled feeding trials are a cornerstone of rigorous nutrition science, providing the high intervention accuracy necessary for dietary biomarker discovery [34]. These trials are classified by the degree of control over the participant's environment and food provision, primarily falling into three categories: fully domiciled, partial-domiciled, and nondomiciled settings [34]. The selection of an appropriate feeding setting is a critical methodological decision that directly impacts the precision of dietary exposure assessment, the validity of recovered biomarkers, and the practical execution of the study. This document outlines application notes and detailed protocols for implementing these settings within the specific context of controlled feeding trials for dietary biomarker research.

Comparative Analysis of Feeding Settings

The choice between fully domiciled, partial-domiciled, and nondomiciled settings involves balancing control, practicality, and the specific research objectives related to biomarker discovery. Each setting offers distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Feeding Trial Settings for Biomarker Research

| Characteristic | Fully Domiciled | Partial-Domiciled | Non-Domiciled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting & Control | Participants reside at a research facility (e.g., metabolic chamber) [34]. | Participants consume some/all meals on-site but live at home [34]. | All meals are provided to participants for home consumption [34]. |

| Typical Duration | Short-term (days to a few months) [34]. | Short to medium-term (days to weeks) [34]. | Medium-term (weeks to months) [34]. |

| Intervention Precision | Very high: Direct control over diet, environment, and sample collection [34]. | High: Good control over dietary intake during on-site meals. | Moderate: Relies on participant compliance away from the research facility. |

| Adherence Monitoring | Direct observation and measurement [34]. | Combination of direct observation and self-reporting. | Indirect (e.g., food returns, dietary biomarkers) [34]. |

| Participant Burden | Very high [34]. | Moderate. | Low [34]. |

| Cost & Resources | Very high and logistically demanding [34]. | Moderate. | Lower cost compared to domiciled settings [34]. |

| Blinding Potential | Possible to double-blind [34]. | Possible to double-blind. | Possible to double-blind [34]. |

| Ideal Application in Biomarker Discovery | Proof-of-concept studies; characterizing acute metabolic responses; pharmacokinetic profiling of candidate biomarkers [15]. | Evaluating biomarker stability under semi-free-living conditions; time-restricted feeding studies [34]. | Assessing biomarker performance in near real-world conditions; validating biomarker utility in free-living populations [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Discovery

Protocol 1: Fully Domiciled Feeding for Biomarker Pharmacokinetics

Aim: To identify and characterize the pharmacokinetic parameters of novel dietary biomarkers under conditions of maximal dietary control and intensive monitoring.

Methods:

- Participant Domiciling: House participants in a metabolic research unit for the entire study duration. Provide all meals and beverages, ensuring no other food is consumed [34].

- Dietary Intervention: Administer a precisely controlled test food or diet in a prespecified amount. A crossover design, where participants later receive a control diet, is often advantageous for reducing intra-individual variability [34].

- Sample Collection: Collect longitudinal biospecimens (e.g., blood, urine) at fixed and frequent intervals (e.g., pre-dose, and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours postprandially) [15].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Analyze serial blood and urine specimens using high-throughput metabolomics platforms to identify candidate compounds associated with the test food [15].

- Data Analysis: Model the appearance and clearance rates of candidate biomarkers to establish pharmacokinetic curves, including parameters such as T~max~, C~max~, and AUC.

Protocol 2: Partial-Domiciled Feeding for Biomarker Evaluation

Aim: To evaluate the ability of candidate biomarkers to detect consumption of specific foods within complex dietary patterns.

Methods:

- Meal Provision: Provide participants with all meals, requiring them to consume at least one main meal per day (e.g., breakfast and dinner) under supervision at the research facility [34].

- Dietary Patterns: Implement controlled feeding studies of various dietary patterns that either include or exclude the biomarker-associated foods [15].

- Biospecimen Collection: Collect non-fasting spot urine samples or first-morning voids daily at the research facility. Schedule periodic fasting blood draws.

- Adherence Monitoring: Use provided food checklists for off-site meals and verify adherence through returned food containers and objective biomarker levels where available [34].

- Biomarker Validation: Analyze biospecimens for candidate biomarkers to determine their sensitivity and specificity for identifying recent consumption of the target food within a mixed diet [15].

Protocol 3: Non-Domiciled Feeding for Biomarker Validation

Aim: To validate the utility of candidate biomarkers for predicting recent and habitual consumption of specific test foods in an independent, free-living observational setting [15].

Methods:

- Home-Delivered Diet: Prepare and deliver all meals and snacks to participants for consumption at home, following a standardized menu [34].

- Free-Living Observation: Allow participants to maintain their normal daily routines while adhering to the provided diet.

- Biospecimen Collection: Instruct participants to collect first-morning urine voids or 24-hour urine samples at home using provided kits. Schedule clinic visits for blood collection.

- Dietary Assessment: Employ a combination of provided food checklists and 24-hour dietary recalls to cross-verify self-reported adherence against biomarker levels [35].

- Predictive Modeling: Use statistical models to assess the validity of candidate biomarkers to predict the intake of the target foods, correcting for potential confounders such as BMI, age, and gut microbiota composition.