Decoding Dietary Complexity: From Molecular Interactions to Clinical Outcomes in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review addresses the intricate correlations between dietary components and their profound implications for drug development and clinical outcomes.

Decoding Dietary Complexity: From Molecular Interactions to Clinical Outcomes in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the intricate correlations between dietary components and their profound implications for drug development and clinical outcomes. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore foundational mechanisms of food-drug and food-component interactions, methodological approaches for assessment and prediction, troubleshooting strategies for analytical challenges, and validation frameworks for translating findings into clinical practice. The article synthesizes current scientific evidence to provide a robust framework for understanding how dietary complexity influences drug efficacy, safety, and nutritional status, while highlighting emerging technologies and standardized methodologies that are advancing this critical field of study.

Unraveling Core Mechanisms: How Dietary Components Interact with Drugs and Each Other

FAQ: Core Mechanisms and Clinical Significance

Q1: What are the fundamental pharmacokinetic mechanisms behind food-drug interactions?

Food-drug interactions primarily alter a drug's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) [1] [2].

- Absorption: Food can influence gastric acidity, stomach emptying rate, and gastrointestinal motility. It can also form complexes with drugs or modulate the activity of transport proteins like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in the intestinal wall, thereby inhibiting or enhancing drug absorption [2] [3].

- Metabolism: This is a primary site of interaction. Food components can inhibit or induce key drug-metabolizing enzymes, most notably the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme family [2] [4]. For example, grapefruit juice is a potent inhibitor of the intestinal CYP3A4 enzyme, leading to dangerously increased absorption and systemic concentrations of certain drugs [3].

- Excretion: Interactions can affect the renal excretion of drugs or lead to drug-induced nutrient deficiencies by altering their distribution and excretion in the body [5] [3].

Q2: Which food components are most clinically significant in drug metabolism interactions?

The table below summarizes high-risk food components and their mechanisms [4] [3].

| Food Component | Key Mechanistic Action | Example Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Grapefruit Juice | Inhibits CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein in the intestine [3]. | Increased bioavailability of Calcium Channel Blockers, Statins, and some antivirals, raising the risk of toxicity [3]. |

| Tyramine-rich Foods | Metabolized by Monoamine Oxidase (MAO); concurrent use with MAO Inhibitors (MAOIs) prevents its breakdown [3]. | Prevents tyramine metabolism, causing a "cheese reaction"—a sudden, dangerous rise in blood pressure [3]. |

| High-Vitamin K Foods | Acts as a cofactor for clotting factors, antagonizing the drug's mechanism [3]. | Reduced anticoagulant effect of Warfarin, increasing risk of thrombosis [3]. |

| St. John's Wort | A potent inducer of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein [4]. | Increased metabolism and reduced plasma levels of drugs like oral contraceptives, cyclosporine, and some antidepressants, leading to therapeutic failure [4]. |

| Dietary Fiber | Can bind to drug molecules in the GI tract [3]. | Reduced absorption and efficacy of drugs like digoxin and certain antidepressants [3]. |

Q3: How do genetic polymorphisms in enzymes like CYP450 complicate food-drug interactions?

Genetic variations in enzymes such as CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 result in populations of "poor metabolizers" or "ultrarapid metabolizers" [1]. The prevalence of these phenotypes varies significantly among different biogeographical groups. When a food component inhibits or induces one of these enzymes, the clinical impact will be dramatically different depending on an individual's innate metabolic phenotype, making personalized dosing strategies essential [1].

Table: Phenotype Frequencies of Key CYP Enzymes across Populations [1]

| Enzyme / Population | Ultrarapid Metabolizer | Normal Metabolizer | Intermediate Metabolizer | Poor Metabolizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6 (European) | 2% | 49% | 38% | 7% |

| CYP2D6 (East Asian) | 1% | 53% | 38% | 1% |

| CYP2C9 (European) | - | 63% | 35% | 3% |

| CYP2C9 (East Asian) | - | 84% | 15% | 1% |

| CYP2C19 (European) | 5% | 40% | 26% | 2% |

| CYP2C19 (East Asian) | 0% | 38% | 46% | 13% |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Q4: We are observing unexpected variability in our in vitro CYP inhibition screening results. What are potential sources of contamination?

Unexpected results, such as a loss of signal or strange peaks, can often be traced to contaminated solvents or reagents, even those from reputable suppliers [6].

- Problem: A sudden, unexplained drop in detection sensitivity (e.g., in LC-MS).

- Solution:

- Benchmark Reagents: Always retain a small portion of "old" reagents known to perform well. If issues arise with a new batch, switch back to the old one to confirm if the reagent is the source [6].

- System Flushing: Flush the entire LC system extensively with a new lot of solvent from a different batch or vendor [6].

- Quality Control: Establish baseline performance data for critical reagents, characterizing them for contaminants and their effect on detection sensitivity for your specific analytes [6].

- Problem: Strange chromatographic peaks or a shifting baseline in UV detection.

- Solution: Consider that different manufacturing lots of solvent may have significant variability in the levels of UV-absorbing contaminants. Testing multiple lots during method validation can help identify and avoid this issue [6].

Q5: In our HILIC separations, we are seeing a complete loss of analyte retention. Is the stationary phase faulty?

Before assuming column failure, investigate the sample solvent composition and injection volume [6].

- Problem: Analytes co-elute with the solvent front, showing no retention.

- Solution:

- Adjust Sample Solvent: In HILIC, the water content of the sample solvent is critical. A sample solvent with too high a water content can destroy retention. Prepare your sample in a solvent with a high percentage of organic phase (e.g., acetonitrile) to match the HILIC initial conditions [6].

- Reduce Injection Volume: A large injection volume of a strong solvent (high water content) can overwhelm the column, creating a localized zone where the stationary phase is ineffective. Significantly reducing the injection volume can often restore proper retention and separation [6].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Green HPLC Analysis of Multiple CYP Substrates using Temperature-Responsive Chromatography

This protocol enables the simultaneous analysis of cytochrome P450 (CYP) probe substrates and their metabolites using an aqueous, isocratic mobile phase, eliminating the need for organic solvents [7].

1. Principle: A silica column is grafted with a temperature-responsive polymer, Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm). The polymer's hydrophobicity changes reversibly with temperature, allowing for control over separation selectivity without altering the mobile phase composition [7].

2. Materials:

- HPLC System: Standard HPLC system with a column oven capable of precise temperature control and a UV or DAD detector [7].

- Column: P(NIPAAm-co-BMA)-grafied silica column [7].

- Mobile Phase: 0.1 M Ammonium acetate buffer, pH 4.8. No organic solvent is used [7].

- Standards: CYP probe substrates (e.g., Phenacetin for CYP1A2, Coumarin for CYP2A6, Tolbutamide for CYP2C9, S-Mephenytoin for CYP2C19, Chlorzoxazone for CYP2E1, Testosterone for CYP3A4) [7].

3. Procedure: 1. Equilibrate the column with the ammonium acetate mobile phase at a constant flow rate (e.g., 1.0 mL/min). 2. Set the column oven temperature to 40°C for optimal separation of the six CYP substrates [7]. 3. Perform an isocratic elution. The entire separation is achieved without a solvent gradient. 4. For analyzing substrates and their metabolites (e.g., Testosterone and 6β-Hydroxytestosterone), investigate different temperatures (e.g., 10°C and 40°C) to achieve resolution, as the elution order follows analyte hydrophobicity at higher temperatures [7]. 5. For column cleaning, flush with cold water instead of organic solvents [7].

Experimental Workflow for Green HPLC Analysis

Protocol 2: Simultaneous Analysis of Food Additives and Caffeine in Powdered Drinks using HPLC-DAD

This method is useful for researchers studying excipients or formulating drug-food products, ensuring surveillance of common additives [8].

1. Principle: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (HPLC-DAD) separates and quantifies multiple analytes based on their interaction with a reversed-phase C18 column and a gradient mobile phase [8].

2. Materials:

- HPLC-DAD System: Binary pump, auto-sampler, DAD detector [8].

- Column: Reverse-phase C18 column (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm) [8].

- Mobile Phase: Phase A: Phosphate Buffer (pH 6.7), Phase B: Methanol [8].

- Gradient Program:

- Initial: 8.5% B

- End: 90% B (linear gradient over 16 minutes) [8].

- Standards: Acesulfame potassium, benzoic acid, sorbic acid, sodium saccharin, tartrazine, caffeine, sunset yellow, aspartame [8].

3. Procedure: 1. Prepare standard stock and working solutions in a water-methanol (50:50 v/v) mixture [8]. 2. Weigh 0.5 g of powdered drink sample and dilute to 100 mL with water. Filter through a 0.45 µm nylon filter [8]. 3. Set the DAD detector to 210 nm for method optimization and monitoring all peaks. For quantification, use specific wavelengths: 200 nm (saccharin, tartrazine, caffeine, aspartame) and 225 nm (acesulfame, benzoate, sorbate) [8]. 4. Inject 20 µL of the sample. The method achieves complete separation of all eight compounds in under 16 minutes [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CYP Probe Substrates (e.g., Phenacetin, Testosterone) | Selective substrates used in "cocktail" experiments to evaluate the inhibitory or inductive potential of a food component on specific CYP enzymes [7]. | Choose probes recommended by regulatory bodies (e.g., FDA) [7]. |

| Temperature-Responsive HPLC Column (P(NIPAAm-co-BMA)) | Allows for green chromatographic separation of compounds with diverse properties using only aqueous mobile phases by modulating column temperature [7]. | The Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST) of the polymer dictates the operational temperature range [7]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software | (Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic) software platforms simulate ADME processes. They can incorporate genetic, life-stage, and disease-state variables to predict food-drug interaction outcomes in specific populations [1]. | Useful for in vitro to in vivo extrapolation and clinical trial optimization [1]. |

| Box-Behnken Design (BBD) | A response surface methodology for efficiently optimizing complex analytical methods (e.g., HPLC) with multiple variables (e.g., mobile phase composition, pH) with fewer experimental runs [8]. | Ideal for multi-response optimization using a desirability function [8]. |

| Lsd1-IN-26 | LSD1-IN-26|Potent LSD1 Inhibitor for Cancer Research | LSD1-IN-26 is a high-potency LSD1/KDM1A inhibitor for epigenetic and oncology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Encephalitic alphavirus-IN-1 | Encephalitic alphavirus-IN-1, MF:C27H25FN6O2, MW:484.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Mechanisms and Clinical Significance

How do GLP-1 receptor agonists modulate taste perception and what is the clinical evidence?

GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide, tirzepatide) influence taste perception through peripheral and central mechanisms. A 2025 cross-sectional study of 411 adults with obesity found that over 20% of participants reported increased perception of sweet and salty tastes during treatment. These subjective changes were statistically associated with beneficial appetite outcomes: increased sweet perception was linked with increased satiety (AOR=2.02), decreased appetite (AOR=1.67), and decreased food cravings (AOR=1.85) [9] [10]. The proposed mechanism involves GLP-1 receptor expression on taste bud cells and in brain regions processing taste and reward, subtly changing how strong flavours are perceived [10] [11].

What are the primary pathways through which medications cause nutrient depletion?

Medications can reduce nutrient bioavailability through several mechanisms: reduced dietary intake (e.g., via appetite suppression), impaired nutrient absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, altered metabolism, and increased excretion. For instance, GLP-1 agonists promote satiety, leading to reduced caloric and nutrient intake, which raises deficiency risks unless diet quality is improved [12]. Other medications may directly antagonize nutrient absorption or transform nutrients into biologically unavailable forms [13].

Which populations are most vulnerable to medication-induced nutritional deficiencies?

Populations at elevated risk include: (1) individuals on long-term GLP-1 therapy due to reduced food intake, (2) elderly patients with inherently reduced nutrient absorption capabilities, (3) those with pre-existing malnutrition or gastrointestinal disorders, and (4) people taking multiple medications that interact synergistically to deplete nutrients [13] [12]. Chronic drug users also represent a high-risk population, often presenting with multiple micronutrient deficiencies due to chaotic lifestyles and poor dietary choices [14].

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Challenge: Disentangling direct taste modulation from central appetite regulation in study outcomes.

Solution: Implement a tiered experimental approach:

- Psychophysical Taste Testing: Use validated tools like the WETT test battery to obtain objective measures of taste threshold, intensity, and identification [10].

- Neuroimaging: Employ fMRI to measure neural activation in response to taste stimuli in brain regions like the angular gyrus, insula, and orbitofrontal cortex [10].

- Subjective Appetite Metrics: Collect self-reported data on satiety, appetite, and cravings using visual analog scales (VAS) or validated questionnaires to correlate with objective measures [9] [10].

Challenge: Controlling for confounding factors in nutrient bioavailability studies.

Solution: The following protocol outlines key control measures for nutrient bioavailability experiments.

Experimental Protocol: Controlling for Confounders in Bioavailability Studies

| Factor | Control Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Intake | Standardized diet (e.g., homogenized meals, nutrient-defined formulas) for 3-5 days prior to and during sample collection. | Eliminates variability from dietary antagonists (e.g., phytate) or enhancers (e.g., vitamin C for iron) [13]. |

| Host Physiology | Stratify participants by age, sex, and health status. Record medication use and health history. | Accounts for host factors known to alter absorption (e.g., age-related decline, gut dysbiosis) [13]. |

| Biomarker Selection | Use the most direct biomarker possible (e.g., 24h urinary excretion for water-soluble vitamins, stable isotopes for mineral absorption). | Avoids artifacts from post-absorptive metabolism; provides a more accurate measure of absorption [13]. |

| Sample Timing | Conduct serial blood/urine sampling to establish AUC (Area Under the Curve) for the nutrient or its biomarkers. | Captures the full kinetic profile of absorption and clearance, superior to single time-point measurements [13]. |

Challenge: Differentiating between malnutrition types in high-risk populations.

Solution: Combine anthropometric and biochemical assessments. Move beyond BMI by using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) to identify "hidden obesity" (normal BMI with high body fat percentage) and low protein mass [15]. Simultaneously, measure plasma levels of key micronutrients (e.g., vitamins A, C, D, E, iron, zinc) to identify "hidden" deficiencies that are not apparent from dietary intake data alone [14].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Appetite and Taste Perception Changes in Patients Using GLP-1 RAs (N=411) [9] [10]

| Parameter | Wegovy (n=217) | Ozempic (n=148) | Mounjaro (n=46) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median BMI Reduction | 17.6% | 17.4% | 15.5% | - |

| Reported Reduced Appetite | 54.4% | 62.1% | 56.5% | 58.4% |

| Reported Increased Satiety | 66.8% | 58.8% | 63.1% | 63.5% |

| Increased Sweet Perception | 19.4% | 21.6% | 21.7% | 21.3% |

| Increased Salty Perception | 26.7% | 16.2% | 15.2% | 22.6% |

| Reported Reduced Craving | 34.1% | 29.7% | 41.3% | - |

Table 2: Common Medication-Induced Nutrient Depletions and Research Assessment Methods

| Medication / Substance Category | At-Risk Nutrients | Recommended Biomarkers for Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | Protein, Fiber, Omega-3, Iron, Calcium, Vitamin D [12] | Serum ferritin, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, BIA for lean mass, dietary intake logs. |

| Chronic Illicit Drug Use | Vitamins A, C, D, E; Iron, Selenium, Potassium [14] | Plasma vitamin levels, serum ferritin, complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes. |

| Opioid Substitution Therapy | Multiple vitamins and minerals; diet high in sugary foods [14] | Fasting glucose (for metabolic risk), plasma micronutrient panel, FFQ. |

Experimental Pathways and Workflows

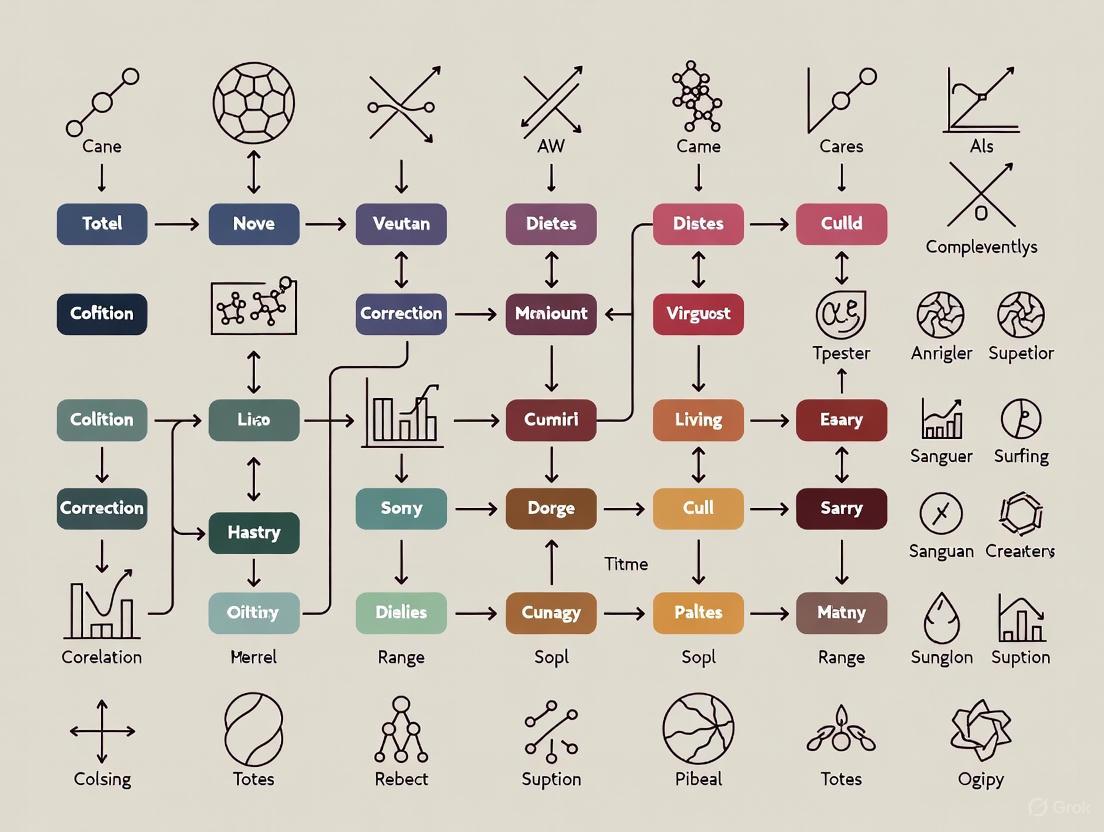

Diagram 1: GLP-1 RA Taste & Appetite Modulation Pathway.

Diagram 2: Research Workflow for Medication-Nutrition Studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Investigating Medication-Nutrition Interactions

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bioelectrical Impedance Analyzer (BIA) | Measures body composition (fat mass, protein mass, water). | Identifying hidden obesity and low protein mass in patients on appetite-suppressing drugs [15]. |

| Validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assesses habitual dietary intake and patterns. | Evaluating shifts in food group consumption and nutrient density in GLP-1 RA users [15]. |

| WETT Test Battery | Objectively quantifies taste function (threshold, intensity, identification). | Differentiating true taste modulation from subjective reports in clinical trials [10]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Tracks absorption and metabolism of specific nutrients. | Precisely measuring mineral (e.g., iron, zinc) bioavailability in the presence of a drug [13]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Quantifies specific nutrient biomarkers in plasma/serum (e.g., 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ferritin). | Monitoring micronutrient status to detect deficiencies in study populations [14] [13]. |

| Ret-IN-12 | Ret-IN-12, MF:C30H30F3N5O4, MW:581.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Protriptyline-d3 | Protriptyline-d3, MF:C19H21N, MW:266.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my protein-polyphenol complex precipitating, and how can I improve its solubility?

- Problem: Precipitation often occurs due to overly strong non-covalent interactions or improper complexation conditions, leading to large, insoluble aggregates.

- Solution:

- Adjust pH: Operate away from the protein's isoelectric point (pI) where solubility is lowest. Alkaline conditions (e.g., pH 9.0) can promote covalent binding between polyphenol quinones and proteins, often yielding more soluble complexes than non-covalent complexes formed near the pI [16].

- Optimize Ratios: Use a lower molar ratio of polyphenol to protein. An excess of polyphenols can lead to over-saturation and "bridging" between multiple protein molecules, causing precipitation [17] [18].

- Apply Ultrasonication: Ultrasound treatment can unfold protein structures, increase solubility, and accelerate covalent complexation through cavitation-generated radicals, improving the stability of the final complex [16].

FAQ 2: The bioactivity (e.g., antioxidant capacity) of my polyphenol is lower after complexation. What went wrong?

- Problem: A decrease in measured antioxidant activity can result from the polyphenol's phenolic hydroxyl groups being involved in binding, making them less available for antioxidant assays.

- Solution:

- Confirm Complex Formation: This may not be a failure but an expected outcome. Use characterization techniques like fluorescence quenching or isothermal titration calorimetry to verify successful binding [17] [18].

- Re-evaluate the Application: The complex may offer controlled release, protecting the polyphenol during storage and gastrointestinal transit, with bioactivity manifesting later during colonic fermentation [18] [19]. Assess bioavailability and long-term stability instead of just initial antioxidant capacity.

- Check for Pro-oxidant Conditions: Under specific conditions (e.g., certain pH, presence of metal ions), some polyphenols can act as pro-oxidants and oxidize proteins, degrading the system. Control oxygen levels and avoid metal contaminants [18].

FAQ 3: My results are inconsistent between experimental replicates. What key factors should I control more strictly?

- Problem: Inconsistency is frequently caused by variations in the complexation process or the source/purity of materials.

- Solution:

- Standardize Polyphenol Source: The chemical structure (number of phenolic rings and OH groups) drastically affects binding affinity. Use high-purity, well-characterized polyphenols from a reliable supplier [17] [19].

- Control Temperature Precisely: Heat treatment can induce both polyphenol autoxidation and protein unfolding, strongly influencing covalent complex yield. Maintain a stable, documented temperature during mixing and reaction [17] [16].

- Account for Enzymatic Activity: If using plant extracts, the presence of endogenous Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) can catalyze oxidation and covalent bonding during sample preparation, leading to variability. Inactivate PPO with heat or inhibitors if consistent non-covalent binding is desired [19].

FAQ 4: How can I distinguish between covalent and non-covalent complexes in my sample?

- Problem: It is methodologically challenging to separate and conclusively identify the type of interaction.

- Solution: Employ a multi-method verification approach:

- SDS-PAGE: Covalent complexes typically show a higher molecular weight band, which is resistant to SDS denaturation, while non-covalent complexes often dissociate [18] [16].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Look for the appearance of new characteristic peaks (e.g., C-N stretch at ~1100 cmâ»Â¹ for an amine-quinone adduct) that indicate covalent bond formation [16].

- Dialyze the Sample: Non-covalent complexes may partially or fully dissociate during extensive dialysis against a dissociating agent (e.g., urea), while covalent complexes will remain stable [17].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Complex Formation and Stability

| Factor | Effect on Complexation | Recommended Range for Stability | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Affects protein charge, polyphenol oxidation, and interaction mechanism. Alkaline pH favors covalent bonding. | Varies by protein (pI); Often pH 7.0-9.0 for covalent complexes. | [17] [16] |

| Temperature | Increases reaction kinetics; induces protein denaturation and polyphenol oxidation. | Controlled heating (e.g., 60-90°C) can enhance covalent complex yield. | [17] [16] |

| Polyphenol:Protein Ratio | Determines complex size and solubility. High ratios cause precipitation. | Typically 1:1 to 1:20 (w/w); requires empirical optimization. | [17] [18] |

| Ionic Strength | High salt concentration can screen electrostatic interactions, weakening non-covalent complexes. | Low to moderate (< 0.2 M NaCl) for electrostatic-driven complexes. | [17] [20] |

Table 2: Common Characterization Techniques for Molecular Complexes

| Technique | Information Provided | Utility for Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Quenching of protein intrinsic fluorescence indicates binding and can estimate binding constants. | Confirm interaction is occurring; compare affinity under different conditions. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Provides full thermodynamic profile: binding constant (K), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS). | Distinguish between binding modes (e.g., electrostatic vs. hydrophobic). |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Measures hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity of particles in solution. | Identify aggregation or precipitation; check complex size stability. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | Visualizes spatial distribution and microstructure of components in a solid or gel matrix. | Directly observe phase separation, network formation, and component localization [21]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparing a Covalent Protein-Polyphenol Complex via Alkaline pH Method

This method leverages polyphenol autoxidation at high pH to form quinones that react covalently with nucleophilic amino acid residues (e.g., lysine, cysteine) in proteins [16].

- Preparation: Dissolve the protein (e.g., bovine serum albumin, β-lactoglobulin) in a phosphate or borate buffer (e.g., 0.01 M, pH 7.0) to a concentration of 1-5 mg/mL. Separately, dissolve the polyphenol (e.g., catechin, EGCG) in the same buffer or a compatible solvent.

- pH Adjustment: Adjust the protein solution to the desired alkaline pH (e.g., pH 9.0) using 1 M NaOH under constant stirring.

- Mixing: Add the polyphenol solution dropwise to the protein solution while stirring vigorously. Maintain a defined molar ratio (e.g., 1:1 to 1:10 protein:polyphenol).

- Reaction: Allow the reaction mixture to stir continuously in the dark for a set period (e.g., 1-24 hours) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C).

- Purification: Dialyze the final reaction mixture extensively against a suitable buffer (e.g., pH 7.4 phosphate buffer) using a membrane with an appropriate molecular weight cutoff to remove unreacted polyphenols and salts. Alternatively, use size-exclusion chromatography.

- Characterization: Lyophilize the purified complex and characterize using SDS-PAGE, FTIR, and UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Protocol 2: Forming a Non-Covalent Polysaccharide-Polyphenol Complex

This protocol relies on spontaneous self-assembly through hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, and electrostatic interactions [17] [19].

- Preparation: Dissolve the polysaccharide (e.g., pectin, chitosan) in a suitable buffer or water to a concentration of 1 mg/mL. This may require mild heating and stirring for several hours. Separately, prepare a polyphenol solution in water or a water-miscible solvent.

- Mixing: Add the polyphenol solution dropwise to the polysaccharide solution under constant magnetic stirring.

- Equilibration: Continue stirring the mixture for a defined period (e.g., 1-4 hours) at room temperature to allow complexation to reach equilibrium.

- Purification (Optional): If necessary, remove unbound polyphenols via dialysis or ultrafiltration.

- Characterization: Analyze the complex using DLS for particle size, UV-Vis spectroscopy for binding assessment via spectral shift, and ITC for thermodynamic parameters.

Experimental Workflow and Interaction Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Experimental pathway for complex formation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Complexation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Items |

|---|---|---|

| Model Proteins | Well-characterized biopolymers for mechanistic studies. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), β-Lactoglobulin (β-LG), Lysozyme, Soy Protein Isolate (SPI), Zein [17] [18]. |

| Model Polysaccharides | Represent different structural features (charge, branching). | Pectin, Chitosan, Cellulose derivatives, Starch, Arabinoxylan [17] [20] [19]. |

| Model Polyphenols | Represent different classes and binding affinities. | Catechin, Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG), Tannic Acid, Quercetin, Anthocyanins [17] [16] [19]. |

| Buffers & Chemicals | Control pH and ionic strength; induce specific reactions. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Borate Buffer, Urea, Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO), Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) [16]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core difference between the BCS and BDDCS?

While both the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) and the Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System (BDDCS) classify drugs into four categories using the same solubility criteria, they differ in their purpose and the second classification parameter [22].

- BCS is used to determine if a drug product is eligible for a biowaiver of in vivo bioequivalence studies. Its second criterion is the extent of intestinal absorption (permeability) [22].

- BDDCS is used to predict a drug's disposition, including potential for drug-drug interactions in the intestine and liver. Its second criterion is the extent of drug metabolism, which was found to correlate with the rate of intestinal permeability [22].

FAQ 2: How can BCS/BDDCS classification predict food effects?

Food can change gastrointestinal conditions (e.g., pH, bile salt concentration, stomach emptying), which primarily affect drug solubility and dissolution. The BCS/BDDCS framework provides a initial, qualitative prediction of how these changes might impact drug absorption [23]:

- BCS/BDDCS Class 1 (High Solubility, High Permeability/Extensive Metabolism): These drugs typically show no significant food effects on the extent of absorption, though the rate of absorption may be delayed [23].

- BCS/BDDCS Class 2 (Low Solubility, High Permeability/Extensive Metabolism): These drugs are most likely to exhibit a positive food effect (increased absorption) because food-induced increases in solubility and dissolution can significantly enhance bioavailability [23].

- BCS/BDDCS Class 3 (High Solubility, Low Permeability/Low Metabolism): The absorption of these drugs is largely unaffected by solubility changes from food. Effects are less predictable and may be influenced by other factors like transporter interactions [22] [23].

- BCS/BDDCS Class 4 (Low Solubility, Low Permeability/Low Metabolism): These drugs generally have poor oral bioavailability. Predicting food effects is complex due to the interplay of multiple limiting factors [23].

FAQ 3: My compound is highly soluble but has low cellular permeability in Caco-2 assays. Yet, human data shows it is completely absorbed. Why does this happen, and how should I classify it?

This discordance occurs because high permeability in cellular systems like Caco-2 correlates with a high rate of jejunal permeability, whereas the BCS guidance for biowaivers is based on the extent of intestinal absorption [22]. For some non-metabolized drugs, low cellular permeability rates can still result in complete absorption if the drug has sufficient time in the gastrointestinal tract. To resolve this:

- For BCS classification, the FDA recommends using human data (mass balance, absolute bioavailability) to demonstrate high absorption [22].

- For BDDCS classification, you would use the extent of metabolism. A drug with low permeability but complete absorption is likely to be eliminated largely unchanged, suggesting BDDCS Class 3 or 4 [22].

FAQ 4: When is a drug eligible for a biowaiver?

According to the FDA, BCS Class 1 drugs (high solubility, high permeability) with rapid dissolution are eligible for a biowaiver of in vivo bioequivalence studies for immediate-release solid oral dosage forms [22]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) may also grant biowaivers for some BCS Class 3 drugs [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Food Effect Prediction Based on Solubility

Problem: A BCS/BDDCS Class 2 drug was predicted to have a positive food effect due to its low solubility. However, clinical data showed no significant change in exposure (AUC) under fed conditions.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Formulation Optimization | The drug product (e.g., a solid dispersion or nanocrystal) may have already optimized the dissolution rate, effectively converting it to Class 1 behavior in the fasted state and minimizing the relative impact of food [23]. | Review the formulation's properties. Use biorelevant dissolution testing to compare fasted and fed state performance. |

| Solubility-Permeability Interplay | Food increases the concentration of bile micelles, which can solubilize the drug. However, for drugs whose absorption is limited by epithelial membrane permeation (SL-E cases), the increase in total solubility is counterbalanced by a decrease in the free fraction of the drug available for permeation, resulting in a negligible net effect on absorption [24]. | Determine the rate-limiting step for absorption. Use tools like the μFLUX system to measure the dissolution-permeation flux in FaSSIF and FeSSIF media [24]. |

| Incorrect Initial Classification | The drug's solubility may have been misclassified. The FDA solubility criteria require complete dissolution of the highest dose strength in 250 mL aqueous media across pH 1.0–7.5 [22]. | Re-evaluate solubility using biorelevant media (FaSSIF/FeSSIF) that simulate fasted and fed state intestinal conditions [25] [23]. |

Issue: Discrepancy Between Preclinical and Clinical Food Effect Data

Problem: A significant food effect was observed in a dog study, but the effect was much smaller or absent in human trials.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Species Differences | Dogs and humans have physiological differences in GI anatomy, bile composition, and transit times. The extent of food effect observed in dogs does not always translate directly to humans [23]. | Do not rely solely on animal data. Use preclinical data to inform and parameterize a physiologically based absorption model (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) for quantitative human prediction [23]. |

| Dose Number Discrepancy | The dose number (ratio of dose to solubility capacity) may be different between animal and human studies due to different doses or gut volumes, leading to different solubility-limited absorption profiles [23]. | Calculate the dose number for both preclinical species and humans to ensure the same biopharmaceutical challenges are being studied. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining BCS/BDDCS Class and Predicting Food Effects

Purpose: To experimentally determine a compound's BCS/BDDCS class and qualitatively assess its potential for food effects in humans.

Methodology Summary: This protocol integrates in silico, in vitro, and in vivo preclinical data to establish a classification and predict food effects [23].

Materials:

- Test compound

- Biorelevant media: Fasted State Simulated Gastric Fluid (FaSSGF), Fasted State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FaSSIF), Fed State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FeSSIF) [25] [24]

- pH adjustment tools

- Shaking water bath (37°C)

- HPLC or UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Caco-2 cell line or similar for permeability assessment

- Preclinical species (e.g., rat) for in vivo PK and metabolism studies

Procedure:

Preliminary In Silico/In Vitro Classification (pBCS/pBDDCS):

- Solubility: Determine the equilibrium solubility in aqueous buffers across pH 1.0–7.5. A drug is highly soluble if the highest dose strength dissolves in 250 mL of buffer [22].

- Permeability: Measure apparent permeability (

Papp) using a Caco-2 assay or similar. Use reference compounds for comparison [22]. - Metabolism (for BDDCS): Use in silico tools to predict

LogPand the probability of extensive metabolism. HighLogPoften correlates with extensive metabolism [23]. - Assign a preliminary class based on the table below.

Preclinical In Vivo Confirmation (rBCS/rBDDCS):

- Conduct radiolabeled mass balance and excretion studies in rats.

- Determine the fraction absorbed (Fa) and the route of elimination (percent excreted unchanged in urine and bile vs. metabolized) [23].

- A drug with high Fa and extensively metabolized aligns with Class 1 or 2. A drug with low Fa and primarily excreted unchanged aligns with Class 3 or 4.

Qualitative Food Effect Prediction:

- Consolidate the pBCS/pBDDCS and rBCS/rBDDCS to estimate the human class (hBCS/hBDDCS).

- Refer to the table in Section 4.1 to predict the likely direction of the food effect.

Protocol: Using Biorelevant Media and μFLUX for Mechanistic Food Effect Studies

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the mechanism of food effects, particularly for solubility-permeation limited (SL-E) drugs, by measuring dissolution-permeation flux under simulated fasted and fed conditions [24].

Materials:

- μFLUX system or similar dissolution-permeation apparatus

- Caco-2 cell monolayers or artificial membranes

- Biorelevant media: FaSSIF and FeSSIF

- Test compounds (e.g., Bosentan, Pranlukast for SL-E; Danazol for SL-U)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare FaSSIF and FeSSIF donor solutions according to established recipes [24]. Set up the acceptor compartment with a suitable buffer.

- Experiment: Place the drug in the donor compartment (FaSSIF or FeSSIF) and initiate the experiment. The drug dissolves and permeates across the membrane into the acceptor compartment.

- Measurement: Sample from the acceptor compartment over time to determine the flux (JμFLUX), which represents the combined dissolution and permeation process.

- Analysis:

- For SL-E drugs, you may observe that while the total drug concentration (

CD) in FeSSIF is much higher than in FaSSIF, the resultingJμFLUXis only marginally increased. This is because the increased solubilization by bile micelles reduces the free fraction of drug available for permeation [24]. - For SL-U drugs, the increase in

CDin FeSSIF should directly translate to a proportional increase inJμFLUX.

- For SL-E drugs, you may observe that while the total drug concentration (

Data Presentation

BCS/BDDCS Classification and Food Effect Predictions

Table 1: Characteristics and typical food effects for each BCS/BDDCS class.

| Class | Solubility | Permeability/Metabolism | Key Characteristics | Typical Food Effect on Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | High | High / Extensive | Permeability is rate-limiting; transporter effects on absorption are minimal [26]. | Minimal effect on extent (AUC); possible delayed Cmax [23]. |

| Class 2 | Low | High / Extensive | Solubility/Dissolution is rate-limiting; efflux transporters can significantly impact absorption [26]. | Positive food effect likely (increased AUC and Cmax) due to enhanced solubility and dissolution [23]. |

| Class 3 | High | Low / Low | Permeability is rate-limiting; uptake transporters are critical for absorption [26]. | Unpredictable; minimal effect from solubility changes, but may be influenced by food-transporter interactions [22] [23]. |

| Class 4 | Low | Low / Low | Both solubility and permeability are poor; both uptake and efflux transporters are important [26]. | Unpredictable and often low bioavailability; positive food effect is possible but not guaranteed [23]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for BCS/BDDCS classification and food effect studies.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FaSSIF/FeSSIF | Biorelevant media simulating the fasted and fed state intestinal environment, containing bile salts and phospholipids [25] [24]. | Measuring solubility and dissolution to predict food effects more accurately than in simple aqueous buffers [23] [24]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates to form a monolayer with enterocyte-like properties. | Assessing apparent permeability (Papp) as a surrogate for human intestinal permeability [22]. |

| Physiologically Based Absorption Software | Software platforms (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) that implement ACAT or ADAM models. | Integrating in vitro data to build mechanistic models and quantitatively simulate human PK profiles and food effects [23]. |

| μFLUX System | An in vitro apparatus that simultaneously measures drug dissolution and permeation flux. | Investigating the mechanism of food effects, especially for distinguishing between SL-E and SL-U cases [24]. |

System Workflows and Diagrams

BDDCS-Based Food Effect Prediction Workflow

Bile Micelle Impact on Drug Absorption

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating Therapeutic Failure in Clinical Studies

Problem: A drug candidate shows promising efficacy in preclinical models but fails to elicit the expected therapeutic response in a clinical trial population.

| Potential Cause | Investigation Methodology | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Unaccounted Patient Subgroups | Conduct subgroup analysis of clinical data; genotype patients for polymorphisms in drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP450 family) or transport proteins [27]. | Implement personalized medicine strategies; develop companion diagnostic tests to identify likely responders [27]. |

| Drug-Diet Interactions | Use Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) or 24-hour recalls to analyze patient dietary patterns. Assess for specific nutrient deficiencies (e.g., Iron, Vitamins) that may alter drug metabolism [28] [29]. | Include nutritional status as a covariate in trial analysis; provide standardized dietary guidance to participants. |

| Polypharmacy | Perform detailed medication reconciliation for trial participants. Review concomitant medications for known drug-drug interactions [30]. | Refine trial exclusion criteria; design studies to specifically investigate common pharmacological associations. |

| Inadequate Dosing Regimen | Perform therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) to measure plasma drug concentrations in non-responders [30]. | Initiate pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling to optimize dosing schedules and formulations. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing the Impact of Nutritional Status on Drug Efficacy

- Objective: To determine if specific nutritional deficiencies correlate with reduced drug plasma levels or therapeutic failure.

- Materials: Patient serum/plasma samples, drug assay kits, nutritional biomarker assay kits (e.g., for ferritin, vitamin B12, vitamin D, zinc).

- Procedure:

- Collect blood samples from trial participants at baseline and at designated intervals post-drug administration.

- Use validated methods (e.g., HPLC, ELISA) to quantify plasma levels of the investigational drug.

- Assay the same samples for established nutritional biomarkers [28].

- Correlate nutritional biomarker levels with drug plasma concentrations and clinical outcome measures using statistical models (e.g., multivariate regression).

- Interpretation: A significant positive correlation between a nutrient level and drug concentration suggests that deficiency may impair drug absorption or metabolism.

Guide 2: Managing Toxicity Risks in Drug Development

Problem: A compound shows unexpected organ toxicity during animal studies or early-phase clinical trials.

| Potential Cause | Investigation Methodology | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Off-Target Activity | Conduct in vitro binding/functional assays against a panel of unrelated receptors and enzymes (e.g., hERG channel for cardiac risk) [31]. | Employ medicinal chemistry strategies to improve compound specificity; use structure-based drug design. |

| Reactive Metabolites | Perform in vitro metabolite identification studies using liver microsomes or hepatocytes. Screen for glutathione adducts or other markers of bioactivation [32]. | Redesign lead compound to block or divert metabolic pathways leading to reactive species. |

| Non-Linear Pharmacokinetics | Conduct detailed dose-ranging toxicology studies in two species. Analyze exposure (AUC, Cmax) versus dose to identify non-proportional increases [31] [33]. | Establish a safe therapeutic window (TI); adjust clinical dosing regimen to stay within linear PK range. |

| Dose-Dependent Effects | Re-evaluate all study data through the lens of dose-response. Determine the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) [31] [33]. | Apply a safety factor to the NOAEL to establish a safe starting dose for human trials. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL)

- Objective: To identify the highest dose of a test compound that does not produce a significant increase in adverse effects compared to a control group.

- Materials: Test compound, vehicle control, animal model (e.g., rodent), equipment for clinical pathology (clinical chemistry analyzer, hematology analyzer), histopathology.

- Procedure:

- Administer the test compound at three or more graded doses (low, mid, high) and a vehicle control to groups of animals for a specified duration (e.g., 28 days).

- Monitor animals daily for clinical signs of toxicity (mortality, morbidity, behavior).

- Collect blood samples at study termination for hematology and clinical chemistry analysis.

- Perform necropsy and histopathological examination on all major organs.

- Statistically compare all findings from dosed groups to the control group.

- Interpretation: The NOAEL is the highest dose level at which no statistically or biologically significant adverse effects are observed. This is a cornerstone for calculating safe human doses [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we better account for patient variability in drug response to reduce therapeutic failure? A1: Moving beyond a "one-size-fits-all" approach is key. Strategies include:

- Pharmacogenomics: Identify genetic markers that predict drug metabolism (e.g., CYP polymorphisms) or target sensitivity [27].

- Precision Dosing: Use therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and PK/PD modeling to tailor doses to individual patients, especially for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index [30].

- Holistic Patient Profiling: Incorporate data on comorbidities, concomitant medications (polypharmacy), and nutritional status into clinical trial analysis and treatment plans [29] [30].

Q2: What are the key principles for assessing the risk of a toxic substance in a new chemical entity? A2: Risk is a function of both hazard and exposure [31] [32].

- Hazard Identification: What type of toxic effect does the substance cause? (e.g., liver damage, neurotoxicity).

- Dose-Response Assessment: What is the relationship between the dose and the incidence/severity of the effect? Establish a threshold like the NOAEL [31].

- Exposure Assessment: What is the dose, duration, and route of exposure (ingestion, inhalation, dermal) for the intended use? [32] [33].

- Risk Characterization: Integrate the above to describe the nature and likelihood of adverse effects under conditions of exposure.

Q3: How can nutritional deficiencies be accurately assessed in a research or clinical population? A3: Assessment requires a combination of methods, as no single tool is perfect [28] [29].

- Dietary Surveys: Use 24-hour recalls or Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) to estimate habitual intake of nutrients.

- Biochemical Biomarkers: Measure serum/plasma levels of nutrients (e.g., vitamin D, ferritin for iron) or functional markers (e.g., erythrocyte transketolase for thiamine). Be aware that levels can be influenced by inflammation [28].

- Clinical Signs: Look for classic deficiency syndromes (e.g., glossitis, dermatitis, neuropathy) [34].

- Combined Approach: Using biomarkers in conjunction with dietary surveys provides the most robust estimate of nutritional status [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | A subjective dietary assessment tool to estimate the frequency and quantity of food consumption over a specific period, used to derive dietary patterns [29]. |

| Nutritional Biomarker Assay Kits | Kits (e.g., for folate, vitamin B12, zinc) used for the objective measurement of nutrient levels in biological samples like serum or plasma to assess nutritional status [28]. |

| Liver Microsomes | Subcellular fractions used in vitro to simulate Phase I drug metabolism (via cytochrome P450 enzymes), helping to identify potential toxic metabolites [31]. |

| Graphical LASSO | A regularisation technique used with Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) to create clear, interpretable networks of food co-consumption from complex dietary data [35]. |

| Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) Assay | A predictive test used in oncology to identify patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who are likely to respond to targeted therapy like trastuzumab, reducing therapeutic failure [27]. |

Visualizing Complex Relationships

Dietary Impact on Drug Response

Toxicology Risk Assessment

Nutritional Status Assessment

Advanced Assessment Techniques: From Computational Modeling to Analytical Frameworks

Quantitative Performance Data of PBPK in Food Effect Prediction

The predictive performance of PBPK modeling for food effects has been extensively evaluated across multiple studies. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from large-scale analyses.

Table 1: Predictive Performance of PBPK Modeling for Food Effects

| Study Scope | Number of Compounds/Cases | Performance within 1.25-fold | Performance within 2-fold | Low Confidence (>2-fold) | Primary Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature & FDA Review | 48 food effect predictions | ~50% | 75% | Not specified | [36] |

| Industry Consortium (de novo models) | 30 compounds | 15 compounds (High confidence) | 23 compounds (High + Moderate) | 7 compounds | [37] [38] |

The performance of PBPK models is closely tied to the underlying mechanism of the food effect. Predictions are most reliable when the food effect is primarily driven by changes in gastrointestinal physiology and luminal fluids, such as:

- Altered solubility due to changes in bile salt and phospholipid concentrations [37] [38]

- Micellar entrapment [38]

- Changes in gastrointestinal pH [36] [39]

- Variations in gastric emptying time and intestinal fluid volumes [36] [39]

Conversely, models face greater challenges when food effects involve complex processes like enterohepatic recirculation or are significantly influenced by transporter-mediated absorption [40] [38].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Established PBPK Workflow for Food Effect Prediction

A generalized, robust workflow for developing and qualifying PBPK models for food effect prediction is outlined below. This "middle-out" approach leverages existing clinical data to build confidence before prospective application [39].

Step 1: Gather Drug-Specific Input Parameters

The foundation of a reliable PBPK model is accurate, high-quality input data [38].

- Physicochemical Properties: Determine pKa, logP, and molecular weight using standardized assays [41] [38].

- Permeability: Measure effective human permeability (Peff,man). A common method uses Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK-WT) cell monolayers in a Transwell system, with 10 µM cyclosporin A added to inhibit P-gp. Apparent permeability (Papp) is scaled to Peff,man using the software's built-in calibration curve [38].

- Solubility: Measure equilibrium solubility in:

- Aqueous buffers across a physiologically relevant pH range (e.g., pH 2, 4, 7).

- Biorelevant media: Fasted State Simulated Gastric Fluid (FaSSGF), Fasted State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FaSSIF-V2), and Fed State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FeSSIF-V2). Prepare these media according to established instructions (e.g., from Biorelevant.com Ltd.). Equilibrate excess drug substance at 37°C with stirring (200 rpm) and measure concentration after a plateau is reached (up to 24 hours) [38].

- Dissolution: Obtain in vitro dissolution profiles for the formulation in both fasted and fed state biorelevant media [39].

- Disposition Parameters: Incorporate clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (Vd) derived from clinical intravenous data or population PK analysis where possible to isolate absorption-related mechanisms [38].

Step 2: Define System-Specific Inputs

Leverage the physiological database within your PBPK platform (e.g., Simcyp, GastroPlus). For food effect studies, ensure the model accounts for fed-state physiological changes, including increased gastric emptying time, higher intestinal fluid volumes, altered GI pH, and elevated bile salt concentrations [36] [39].

Step 3: Verify the Base PBPK Model

Before predicting food effect, the model must be verified against observed clinical pharmacokinetic data, typically from the fasted state [36] [39]. A model is considered verified when predicted AUC and Cmax for an oral dose fall within 1.25–2.0 fold of observed values, and the shape of the concentration-time profile is captured adequately [36] [38].

Step 4: Apply Fed-State Physiology

Switch the system parameters in the verified model to the fed-state condition. Input fed-state specific drug parameters, particularly solubility and dissolution data measured in FeSSIF-V2 [39] [38].

Step 5: Simulate and Predict Food Effect

Run the simulation under fed-state conditions. Calculate the predicted food effect as the ratio of population geometric means (fed/fasted) for AUC and Cmax [36] [39].

Step 6: Quality Control and Potential Optimization

Compare the predicted AUC and Cmax ratios (AUCR, CmaxR) against observed clinical food effect data, if available.

- High Confidence: Prediction within 0.8- to 1.25-fold of observed [38].

- Moderate Confidence: Prediction within 0.5- to 2-fold of observed [38].

- Low Confidence: Prediction outside 2-fold of observed [38].

If the prediction has low confidence, investigate and optimize key parameters. Commonly optimized parameters to capture the food effect include dissolution rate and precipitation time [36]. A structured decision tree should guide this process to maintain consistency and rigor [38].

Decision Tree for Model Verification and Optimization

The following diagram details the decision-making process for model verification and optimization, a critical component of the workflow above.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My PBPK model accurately predicts fasted-state PK but fails to capture the fed-state profile. What are the most common parameters to investigate?

A: The most frequently optimized parameters when a model fails to predict food effect are dissolution rate and precipitation time [36]. First, ensure that the solubility data input for the fed state accurately reflects the supersaturation and precipitation behavior of your compound in fed intestinal conditions. The use of kinetically-measured solubility and precipitation data from biorelevant media (FeSSIF) often improves predictions [39].

Q2: For which types of compounds and mechanisms is PBPK food effect prediction most reliable?

A: Predictive performance is highest when the food effect is primarily driven by changes in GI luminal fluids and physiology [37] [38]. This includes mechanisms like:

- Enhanced solubility of lipophilic, low-solubility (BCS II) compounds due to bile micelles [39] [38].

- Changes in absorption due to altered GI pH, fluid volume, or motility [36] [37]. PBPK models face greater challenges with compounds whose absorption is limited by intestinal uptake transporters or those involving complex enterohepatic recirculation [40] [38].

Q3: Can a qualified PBPK model replace a clinical food effect study for regulatory submission?

A: While regulatory acceptance is evolving, a robustly qualified PBPK model can potentially support or replace a clinical study in certain contexts. The model must be developed and verified according to a rigorous workflow, often using a "middle-out" approach with existing clinical data [39]. The FDA and EMA have begun to consider PBPK analyses in submissions, but this requires demonstrated predictive performance and transparency. It is crucial to follow emerging regulatory guidelines on model credibility [42] [43].

Q4: We are in early development and have no clinical data. Can we use a purely "bottom-up" PBPK model to predict food effect risk?

A: Yes. A bottom-up model built entirely on in vitro and in silico parameters can be used for early risk assessment to prioritize compounds or formulations [44]. However, the absolute predictive accuracy will be lower than for a model verified against clinical PK data. The predictions should be used internally to guide development strategy rather than for definitive regulatory decisions at this stage [45].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for PBPK Food Effect Modeling

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Under-prediction of positive food effect | Model underestimates solubility increase in fed state; Does not capture supersaturation; Incorrect precipitation kinetics. | Re-measure solubility and kinetic precipitation in FeSSIF-V2; Optimize precipitation time parameter in the model [36] [39]. |

| Failure to capture multiple peaks in PK profile | Model does not account for enterohepatic recirculation (EHR). | Incorporate a mechanistic EHR process into the model, for example by triggering a gallbladder emptying event at meal time [40]. |

| Poor prediction of Cmax but accurate AUC | Inaccurate representation of gastric emptying or dissolution rate in the fed state. | Perform sensitivity analysis on gastric emptying time and dissolution rate; Ensure fed-state dissolution profile is correctly input [39]. |

| Model fails verification in fasted state | Incorrect CL or Vd estimates; Poor in vitro-in vivo correlation for permeability or solubility. | Fit/optimize disposition parameters using IV data if available; Re-check experimental methods for permeability/solubility [38]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Software for PBPK Food Effect Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Details & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Media | Simulates fasted (FaSSGF, FaSSIF-V2) and fed (FeSSIF-V2) intestinal conditions for in vitro solubility and dissolution testing. | Critical for measuring physiologically relevant solubility. Prepared according to standardized instructions (e.g., from Biorelevant.com Ltd.) [38]. |

| MDCK Cell Line | Used in vitro to determine apparent permeability (Papp) of a compound, which is scaled to effective human permeability (Peff,man). | Often modified to knockdown endogenous canine P-gp. Experiments include a P-gp inhibitor like cyclosporin A for relevant baseline permeability [38]. |

| PBPK Software Platforms | Provides the technical infrastructure, physiological databases, and algorithms to build, simulate, and qualify PBPK models. | Industry standards include GastroPlus (Simulation Plus), Simcyp Simulator (Certara), and PK-Sim (Open Systems Pharmacology) [41] [42]. |

| Clinical IV PK Data | Used to accurately parameterize the disposition (CL, Vd) of the PBPK model, isolating uncertainty to the absorption process. | Sourced from literature or clinical studies. Not always mandatory, but highly recommended to simplify model development and increase confidence for food effect prediction [38]. |

| KRAS G12C inhibitor 43 | KRAS G12C Inhibitor 43|Potent Research Compound | Explore KRAS G12C inhibitor 43, a potent small molecule for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Trk-IN-8 | Trk-IN-8|Potent TRK Inhibitor|For Research Use | Trk-IN-8 is a potent TRK inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only and not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

A fundamental challenge in nutritional epidemiology is analyzing the effect of overall diet, rather than single nutrients, on health outcomes. Dietary components are highly correlated and interact in complex ways, making it difficult to isolate their individual effects [46]. Dietary pattern analysis addresses this by examining combinations of foods and beverages people consume [29]. This technical guide explores the two predominant methodological approaches for dietary pattern analysis—index-based (a priori) and data-driven (a posteriori) methods—within the context of research handling complex dietary correlations. You will find troubleshooting guidance, methodological protocols, and FAQs to support your research implementation.

Section 1: Core Methodological Approaches & Comparison

Understanding the Two Main Paradigms

Researchers generally classify dietary pattern assessment methods into two categories [47] [29] [48]:

- Index-Based Methods (A Priori): These investigator-driven approaches measure adherence to predefined dietary patterns based on existing nutritional knowledge and dietary guidelines. Examples include the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), Alternate Mediterranean Diet Score (aMED), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) score [47] [48].

- Data-Driven Methods (A Posteriori): These approaches use multivariate statistical techniques to derive dietary patterns directly from population dietary intake data. Principal component analysis (PCA), factor analysis, cluster analysis, and reduced rank regression (RRR) are prominent examples [47] [49] [50].

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Index-Based and Data-Driven Dietary Pattern Analysis Methods

| Feature | Index-Based (A Priori) Methods | Data-Driven (A Posteriori) Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Measures adherence to predefined patterns based on dietary guidelines [29] [48] | Derives patterns empirically from dietary intake data [47] [48] |

| Basis for Pattern | Prior knowledge/hypothesis about diet-health relationships [47] | Correlations and variances in consumed food groups [47] [49] |

| Output | A score representing overall diet quality [48] | Patterns (factors/clusters) specific to the study population [47] |

| Comparability | High; allows direct comparison across different studies [47] [48] | Limited; patterns are population-specific [47] |

| Key Advantage | Objective, based on established evidence; easy to interpret [48] | Identifies real-world dietary combinations without preconceptions [48] |

| Key Limitation | Subjective choices in component selection and scoring [48] | Solutions depend on researcher's analytical choices [47] [50] |

| Common Techniques | HEI, AHEI, aMED, DASH score [47] [48] | PCA/Factor Analysis, Cluster Analysis (K-means), RRR [47] [50] [51] |

Section 2: Technical Guide & Troubleshooting FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How do I choose the optimal number of factors in Principal Component Analysis (PCA)?

The number of factors to retain is typically determined by a combination of three criteria [49] [48]:

- Eigenvalue greater than one (Kaiser's rule)

- Scree plot visual inspection: Looking for the "elbow" point where the slope of the line levels off

- Interpretability: The retained factors should be meaningful and explain a reasonable proportion of the variance (often >5-10% per factor)

Troubleshooting Tip: If the derived patterns are not interpretable, even with a statistically justified number of factors, re-examine your initial food group aggregation. Overly broad or narrow food groups can obscure meaningful patterns.

FAQ 2: My cluster analysis solution is unstable. How can I validate it?

Cluster stability is a common challenge. To objectively select the most appropriate clustering method and number of clusters, use stability-based validation [50].

- Method: Randomly split your dataset into training and test sets multiple times (e.g., 20 iterations).

- Validation: Apply the clustering algorithm to both sets and compare the solutions using stability indices like the adjusted Rand index or misclassification rate.

- Output: The solution with the highest average stability (lowest misclassification rate) across iterations is considered the most robust and representative of the underlying population structure [50].

FAQ 3: Why is the diagnostic accuracy of my diet quality index lower than expected?

The predictive ability of a composite index is influenced by its components [46]:

- Number of Components: Diagnostic accuracy generally increases with the number of components, but only when the components have low or no intercorrelation.

- Intracorrelation: Ensure that the components included in your index are strongly associated with the health outcome of interest.

- Recommendation: For optimal accuracy, construct your index using multiple, low-intercorrelated components that are each independently associated with the target outcome [46].

FAQ 4: How should I handle highly correlated food items in my dataset before analysis?

This is a classic problem arising from the complex correlations in dietary data.

- Standard Practice: The initial step is to pre-aggregate individual food items into logically similar food groups [49] [50]. For example, combine various types of leafy greens, or different kinds of red meat.

- Rationale: This reduces multicollinearity, simplifies the model, and facilitates the interpretation of derived patterns by focusing on broader dietary behaviors.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Protocol 1: Implementing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for Dietary Patterns

This protocol is based on a cross-sectional analysis of Iranian adults [49].

- Data Preparation: Collect dietary intake data via a validated FFQ, 24-hour recall, or food diary. Pre-aggregate all consumed food items into 40-50 meaningful food groups (e.g., "citrus fruits," "hydrogenated fats," "non-leafy vegetables") based on nutritional similarity and culinary use [49].

- Input Variable Preparation: Use grams consumed per day per food group as input variables. Adjust for total energy intake using the residual method [50].

- Execution: Perform PCA with varimax rotation on the food group variables to derive principal components.

- Factor Retention & Naming: Retain factors with an eigenvalue >1.5 (or using scree plot interpretation). Name the resulting dietary patterns based on the food groups that load most strongly (e.g., absolute factor loading >0.20) on each component [49].

- Output: Generate standardized dietary pattern scores for each participant for use in subsequent analyses with health outcomes.

Protocol 2: Conducting K-Means Cluster Analysis for Dietary Patterns

This protocol is derived from a study on NAFLD in Hispanic patients [51] and a stability-based validation study [50].

- Data Preparation & Standardization: Prepare food group intake data as in the PCA protocol. Crucially, standardize the intake of each food group to a common scale (e.g., mean=0, standard deviation=1) to prevent variables with larger scales from dominating the cluster solution [50].

- Preliminary Analysis: Run the FASTCLUS (K-means) procedure for a range of pre-specified cluster numbers (e.g., 2 to 4) to assess interpretability [51].

- Stability Validation (Recommended): Use a stability-based validation procedure with multiple random splits of your dataset to objectively select the optimal number of clusters and clustering method [50].

- Final Clustering: Execute the K-means algorithm with the validated number of clusters. The algorithm will assign each participant to a single, mutually exclusive cluster based on the Euclidean distance between their diet and the cluster center [51].

- Output & Description: Characterize each cluster by comparing the mean intake of food groups between clusters. Name the clusters based on their predominant dietary features (e.g., "Plant-food/Prudent" vs. "Fast-food/Meats" pattern) [51].

Section 3: Visual Workflows & Research Toolkit

Decision Pathway for Method Selection

The following diagram outlines the logical process for selecting an appropriate dietary pattern analysis method based on your research objective.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Pattern Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Primary tool for collecting habitual dietary intake data; assesses frequency and quantity of food consumption over a specified period [29]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | A detailed, interviewer-led method to capture all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24 hours; often used for population-level estimates [49] [29]. |

| Food Composition Database | Converts reported food consumption into nutrient intake data; essential for calculating index scores and profiling the nutrient content of derived patterns [49]. |

| Statistical Software (SAS, R, Stata) | Platforms for implementing all data-driven methods (PCA, Cluster Analysis, RRR) and calculating most index-based scores [48]. |

| Stability Validation Script (R/Python) | Custom or packaged code to perform stability-based validation for cluster analysis, ensuring robust and reproducible results [50]. |

| Diet Quality Index (DQI) Framework | A predefined scoring structure (e.g., HEI, AHEI) used to calculate an individual's adherence to a specific dietary pattern [29] [48]. |

| Grb2 SH2 domain inhibitor 1 | Grb2 SH2 domain inhibitor 1, MF:C68H95N20O15P, MW:1463.6 g/mol |

| Cox-2-IN-30 | Cox-2-IN-30, MF:C17H16N6O3S, MW:384.4 g/mol |

Biorelevant solubility and precipitation testing uses laboratory test solutions that simulate the chemical and physical conditions of the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract to predict how drugs will behave in the body. Unlike conventional dissolution media, these media contain physiological components like bile salts and lipids to replicate actual GI fluids in both fasted and fed states. This approach provides more accurate prediction of in vivo drug performance before clinical trials, helping researchers screen formulations more effectively [52] [53].

The transition of a drug from the stomach to the intestine represents a critical phase where precipitation often occurs, particularly for poorly soluble compounds. Two-stage biorelevant dissolution testing, also known as a "biorelevant transfer test," is specifically designed to simulate this physiological process, where drug products initially in contact with simulated gastric fluid (FaSSGF) are subsequently converted to simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) [54]. This method is particularly valuable for drug development of water-insoluble bases where drug solubility is higher in gastric fluid than intestinal fluid [54].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: When should I use two-stage biorelevant dissolution testing instead of single-stage methods?

Two-stage dissolution is particularly crucial for immediate-release formulations of basic drugs with low water solubility, especially when the drug exhibits higher solubility in gastric fluid than intestinal fluid [54] [55]. This method provides critical insights into precipitation or supersaturation behavior as pH shifts from stomach to intestinal pH.

Key indicators for choosing two-stage testing:

- Poorly soluble basic drugs that may precipitate at intestinal pH

- Formulations where supersaturation maintenance is critical for absorption

- Compounds with significant food effects

- Amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) where precipitation kinetics affect performance [55]

FAQ 2: Why does my drug show good solubility in gastric conditions but poor oral bioavailability?

This common issue often results from drug precipitation during the transition from stomach to small intestine. The solubility of many drugs is highly pH-dependent, particularly for weak bases that are highly soluble in acidic gastric environments but may precipitate rapidly at neutral intestinal pH [55]. Two-stage testing can identify this "precipitation risk" that single-stage methods in consistent pH media would miss.

The cinnarizine case study demonstrates how a drug can maintain supersaturation without precipitation during this transition, highlighting the importance of testing the entire GI journey [56].

FAQ 3: What are the critical differences between fasted and fed state simulated media?

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biorelevant Media Types

| Medium | Prandial State | Fluid Simulated | pH | Key Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FaSSGF | Fasted | Gastric | 1.6 | Pepsin, low bile salts [52] |

| FaSSIF | Fasted | Small Intestinal | 6.5 | Bile salts, phospholipids [52] |

| FeSSIF | Fed | Small Intestinal | 5.0 | Higher bile salt/phospholipid concentration [52] |

| FaSSIF-V2 | Fasted | Small Intestinal | 6.5 | Updated formula [52] |

| FeSSIF-V2 | Fed | Small Intestinal | 5.8 | Updated formula [52] |

FAQ 4: How do I properly execute a two-stage dissolution experiment?

Standardized Two-Stage Protocol:

- Apparatus: USP Apparatus 2 (paddle) [54]

- Stage 1 (Gastric):

- Volume: 450 mL FaSSGF

- Duration: 1-2 hours

- Parameters: 37°C, 75 rpm [56]

- Stage 2 (Intestinal):

- Add 450 mL FaSSIF Converter to existing medium

- Duration: 2+ hours

- Parameters: 37°C, 75 rpm [56]

- Sampling: Use appropriate filtration (e.g., 13mm Glass Microfibre Syringe Filters) at predetermined timepoints [56]

Critical Consideration: Before conducting two-stage testing, researchers are strongly recommended to first test dissolution in FaSSIF alone to establish how the drug product releases prior to gastric exposure [54].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Precipitation During pH Transition

Symptoms: Rapid decrease in dissolved drug concentration after FaSSIF converter addition.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Table 2: Precipitation Troubleshooting Guide

| Cause | Identification | Resolution Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Poor supersaturation maintenance | Concentration drops >20% within 30 minutes of pH shift | Formulate with precipitation inhibitors (polymers like HPMC, HPMCAS) [55] |

| Inadequate bile salt concentration | Precipitation occurs faster than in vivo data suggests | Adjust bile salt/phospholipid ratios; consider fed state media for lipophilic drugs [53] |

| Too rapid pH transition | Sharp precipitation curve | Modify addition rate of FaSSIF converter; consider gradual pH shift methods |

| Drug-specific crystallization tendency | Variable results across similar compounds | Pre-classify drugs by crystallization tendency (slow/moderate/fast) [55] |

Problem: Poor Discrimination Between Formulations

Symptoms: Inability to distinguish performance differences between formulation prototypes.

Solutions:

- Ensure non-sink conditions to properly evaluate supersaturation maintenance [55]

- Extend sampling frequency during critical transition periods

- Consider incorporating additional analytical techniques (e.g., particle size analysis)

- Verify media composition freshness and preparation accuracy

Problem: Lack of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC)

Symptoms: Dissolution data doesn't correlate with observed pharmacokinetic profiles.

Solutions:

- Review media selection appropriateness for your drug's properties

- Consider using more sophisticated systems like the Gastrointestinal Simulator (GIS) for complex formulations [55]

- Evaluate whether absorption limitations (rather than dissolution) may be controlling bioavailability

- Verify biorelevant media composition matches current physiological understanding

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Biorelevant Testing

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3F Powder | Base powder for preparing various biorelevant media | Enables preparation of FaSSGF, FaSSIF, FeSSIF [52] |

| FaSSIF Converter Buffer Concentrate | Converts FaSSGF to FaSSIF during two-stage testing | Critical for simulating gastric-to-intestinal transition [54] |

| FaSSGF Buffer Concentrate | Preparation of fasted state gastric fluid | Maintains physiological surface tension [52] |

| FaSSIF/FeSSIF-V2 Powders | Updated intestinal fluid simulations | Improved predictability for contemporary formulations [52] |

| AChE-IN-9 | AChE-IN-9, MF:C30H35N5O9, MW:609.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mat2A-IN-4 | Mat2A-IN-4|Potent MAT2A Inhibitor for Cancer Research | Mat2A-IN-4 is a potent MAT2A inhibitor for oncology research. It disrupts SAM production, targeting MTAP-deleted cancers. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Method Selection Algorithm

Standard Operating Procedure: Two-Stage Dissolution Testing

Materials and Equipment

- USP Apparatus 2 (paddle)