Designing Robust Nutritional RCT Protocols: A Comprehensive Guide from SPIRIT 2025 to Implementation

This comprehensive guide addresses the unique challenges in designing randomized controlled trial (RCT) protocols for nutritional interventions, providing researchers and clinical trial professionals with evidence-based methodologies to enhance study validity...

Designing Robust Nutritional RCT Protocols: A Comprehensive Guide from SPIRIT 2025 to Implementation

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the unique challenges in designing randomized controlled trial (RCT) protocols for nutritional interventions, providing researchers and clinical trial professionals with evidence-based methodologies to enhance study validity and impact. Covering foundational principles from the updated SPIRIT 2025 guidelines to complex intervention design, the article explores practical implementation strategies for dietary clinical trials (DCTs), addresses common methodological challenges including blinding difficulties and adherence issues, and examines validation frameworks through systematic reviews and regulatory considerations. With special emphasis on digital health tools and behavioral interventions, this resource aims to improve the quality of nutritional evidence supporting clinical guidelines and public health policies.

Understanding the Landscape: Core Principles and Updated Guidelines for Nutritional RCTs

A high-quality clinical trial protocol serves as the fundamental blueprint for ensuring the scientific integrity, ethical compliance, and methodological rigor of an investigation. The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement, first published in 2013, has become the internationally recognized benchmark for developing clinical trial protocols [1]. To address the evolving landscape of clinical research, including developing trends in open science and patient-centered principles, the SPIRIT working group undertook a comprehensive update, resulting in the SPIRIT 2025 statement [1] [2].

This update reflects a significant advancement in trial protocol methodology, incorporating a decade of accumulated empirical evidence and methodological refinements. The SPIRIT 2025 guideline emerges from a rigorous consensus process involving hundreds of international experts, including statisticians, trial investigators, clinicians, journal editors, and patient representatives [2] [3]. For researchers specializing in nutritional interventions, these updated guidelines provide a critical framework for enhancing the quality, transparency, and reproducibility of clinical trials in our field, where methodological challenges such as blinding difficulties, adherence monitoring, and intervention complexity have historically complicated trial design and interpretation [4] [5].

Core Updates in SPIRIT 2025 Statement

The SPIRIT 2025 statement introduces substantive changes from its 2013 predecessor, refining the checklist to address gaps in previous guidance and incorporating emerging best practices. The systematic update process, which included a scoping review of literature from 2013-2022 and an international three-round Delphi survey with 317 participants, led to several fundamental modifications [2] [3].

Structural and Content Changes

The updated guideline features significant structural reorganization and content refinement. The executive group added two new protocol items, revised five existing items, and deleted or merged several others to reduce redundancy and improve clarity [2]. A notable structural improvement is the creation of a dedicated open science section that consolidates items critical to promoting transparency and accessibility of trial methods and results [3]. This section encompasses trial registration, sharing of full protocols and statistical analysis plans, data sharing policies, and disclosure of funding sources and conflicts of interest [2].

Table 1: Key Structural Changes in SPIRIT 2025

| Change Type | Number of Items | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| New Items | 2 | Patient and public involvement (Item 11); Expanded open science section |

| Revised Items | 5 | Intervention description; Outcomes; Harms; Sample size; Consent materials |

| Deleted/Merged Items | 5 | Merger of related administrative items |

| Total Checklist Items | 34 | (Reduced from 33 items in SPIRIT 2013 with restructuring) |

Enhanced Focus on Patient-Centered Research

A groundbreaking addition to SPIRIT 2025 is Item 11, which requires researchers to describe how patients and the public will be involved in trial design, conduct, and reporting [2] [3]. This formalizes the expectation for meaningful patient engagement throughout the research process, moving beyond tokenistic representation to genuine partnership. For nutritional intervention research, this might involve collaborating with patients to design culturally appropriate dietary interventions, developing patient-friendly outcome measures, or creating accessible result summaries for participant communities [5].

Strengthened Reporting of Methodological Elements

The updated statement places additional emphasis on several methodological aspects critical to trial validity. There is enhanced guidance on the assessment of harms (integrating recommendations from CONSORT Harms 2022), more detailed description of interventions and comparators (informed by TIDieR), and clearer specification of outcome measures (incorporating SPIRIT-Outcomes 2022) [2] [3]. These refinements address common weaknesses identified in nutritional intervention trials, where inadequate description of comparator diets, insufficient documentation of adverse events, and ambiguous outcome measurement have hampered evidence synthesis and clinical application [4].

Application to Nutritional Intervention Research

Nutritional intervention trials present unique methodological challenges that distinguish them from conventional pharmaceutical trials. These include the complexity of dietary interventions, difficulties with blinding participants and personnel, challenges in standardizing control group conditions, and the multifaceted nature of adherence monitoring in free-living populations [4] [5]. The SPIRIT 2025 framework provides specific guidance to address these challenges while maintaining the flexibility needed for diverse nutritional study designs.

Implementing the Open Science Framework

The new open science module in SPIRIT 2025 has particular significance for nutritional research, where heterogeneous methodologies and variable reporting have historically limited evidence synthesis. Item 6 specifically addresses data sharing, requiring protocols to specify where and how de-identified participant data, data dictionaries, and statistical code will be accessible [2]. For nutritional researchers, this might include sharing detailed dietary assessment data, recipe formulations, nutrient composition databases, or behavioral intervention materials that enable replication and secondary analysis.

The following workflow illustrates the implementation of SPIRIT 2025's open science requirements within the context of a nutritional intervention trial:

Methodological Considerations for Nutritional Trials

SPIRIT 2025 provides a framework for addressing persistent methodological challenges in nutritional research. The updated intervention description item (Item 15) requires sufficient detail to enable replication, which for nutritional trials might include documenting food sourcing, meal preparation methods, nutrient composition analysis, and quality control procedures [2] [4]. Similarly, the enhanced guidance on adherence monitoring (Item 15) encourages researchers to move beyond simplistic measures like pill counts or session attendance toward more robust methodologies such as biomarker verification, digital monitoring technologies, or dietary assessment tools with demonstrated validity [4] [6].

Table 2: Essential Methodological Components for Nutritional Intervention Protocols

| SPIRIT 2025 Item | Nutritional Research Application | Recommended Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Item 11: Patient Involvement | Engage participants in designing culturally appropriate interventions and acceptable outcome measures | Patient advisory boards; Co-design workshops; Preference assessment surveys |

| Item 15: Intervention Description | Detailed nutritional intervention specification with sufficient detail for replication | Standardized recipes; Nutrient composition analysis; Food procurement protocols; Preparation methods |

| Item 18: Outcomes | Selection of clinically meaningful endpoints with appropriate measurement methods | Primary outcome justification; Validated dietary assessment tools; Biomarker measurement protocols |

| Item 29: Trial Monitoring | Processes to ensure intervention fidelity and adherence assessment | Kitchen center audits; Digital photography of meals; Biomarker verification; Smart packaging for supplements |

Implementation Protocols for Nutritional Research

Translating SPIRIT 2025 recommendations into practical protocols requires careful consideration of the unique aspects of nutritional science. The following section provides detailed methodologies for implementing key updates within nutritional intervention trials.

Protocol for Patient and Public Involvement (Item 11)

Objective: To meaningfully involve patients and the public in the design, conduct, and reporting of a nutritional intervention trial.

Background: Patient involvement enhances trial relevance, acceptability, and impact, particularly for nutritional interventions where dietary behaviors are deeply embedded in cultural and personal preferences [2].

Procedures:

- Establish a Patient Advisory Group: Recruit 6-8 individuals representing the target population, ensuring diversity in age, gender, socioeconomic status, and dietary patterns.

- Design Consultation Phase: Conduct structured workshops to review and refine:

- Intervention components (dietary prescriptions, supplement formulations)

- Outcome measurement tools and schedules

- Participant-facing materials (consent forms, dietary instructions)

- Retention strategies and burden minimization

- Ongoing Involvement: Include patient representatives on trial steering committees with appropriate compensation and support.

- Reporting Integration: Document the influence of patient input on protocol development and disseminate results in formats accessible to lay audiences.

Deliverables: Modified protocol reflecting patient input; Plain language summary; Documentation of involvement impact.

Protocol for Nutritional Intervention Description (Item 15)

Objective: To provide comprehensive details of the nutritional intervention and comparator enabling replication and critical appraisal.

Background: Inadequate description of nutritional interventions remains a major limitation in evidence synthesis and clinical application [4] [5].

Procedures:

- Intervention Specification:

- Document specific foods, nutrients, or dietary patterns with quantitative targets

- Describe food sources, procurement methods, and quality control procedures

- Provide nutritional composition analysis using standardized methods

- Detail supplement formulations, manufacturing, and quality assurance

- Delivery Protocol:

- Define intervention setting (clinic, free-living, controlled environment)

- Specify staff qualifications, training procedures, and monitoring

- Describe intervention intensity, duration, and follow-up schedule

- Document behavior change strategies and educational materials

- Comparator Description: Apply the same detailed specification to control conditions, including attention control elements.

- Adherence Monitoring: Implement multi-modal assessment including:

- Biomarker verification (e.g., plasma nutrients, metabolites)

- Dietary intake assessment (validated tools appropriate to population)

- Digital monitoring (photographic food records, smart packaging)

- Process measures (session attendance, interventionist fidelity)

Deliverables: Comprehensive intervention manual; Standard operating procedures; Quality assurance protocols.

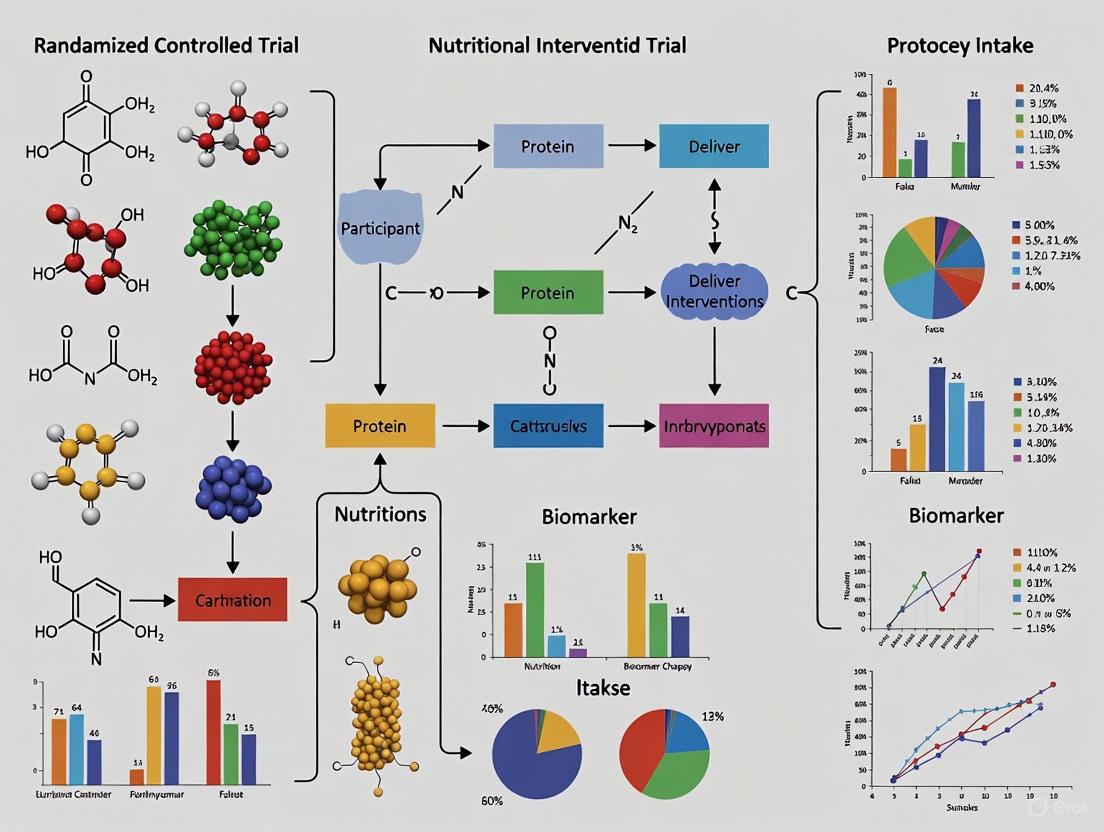

The following diagram illustrates the key methodological workflow for designing a nutritional intervention trial according to SPIRIT 2025 guidelines:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nutritional Intervention Trials

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Tools | 24-hour recall protocols; Food frequency questionnaires; Diet history interviews; Digital food photography apps | Quantify dietary intake and compliance with intervention targets |

| Biological Sample Collection | EDTA tubes for plasma; Serum separator tubes; Urine collection containers; DNA/RNA stabilization kits | Biomarker analysis for compliance verification and mechanism exploration |

| Nutritional Biomarkers | Plasma carotenoids; Omega-3 indices; Vitamin D [25(OH)D]; Magnesium (RBC); Fatty acid profiles | Objective verification of intervention adherence and nutrient status |

| Body Composition Tools | Bioelectrical impedance analyzers; DEXA scanners; Anthropometric kits (stadiometers, scales) | Assessment of body composition changes in response to intervention |

| Intervention Materials | Standardized food products; Nutrient supplements; Meal replacement formulations; Recipe manuals | Consistent delivery of nutritional intervention components |

| Data Management Systems | Electronic data capture platforms; Dietary analysis software; Randomization modules | Protocol implementation, data integrity, and allocation concealment |

| rac Darifenacin-d4 | rac Darifenacin-d4, CAS:1189701-43-6, MF:C28H30N2O2, MW:430.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Protein Kinase C (530-558) | Protein Kinase C (530-558), CAS:122613-29-0, MF:C148H221N35O50S2, MW:3354.711 | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Analysis and Future Directions

While SPIRIT 2025 represents a significant advancement in trial protocol guidance, its implementation in nutritional research requires careful consideration of several methodological challenges. The updated statement has been critiqued for potentially insufficient emphasis on robust adherence monitoring methodologies, particularly concerning the removal of specific reference to laboratory tests for verifying medication exposure in favor of more general guidance [6]. For nutritional interventions, this underscores the importance of going beyond minimum standards to incorporate objective biomarkers of adherence, such as circulating nutrient levels or metabolic profiles, which provide verification beyond self-reported dietary intake or supplement container returns [4] [6].

Nutritional researchers should view SPIRIT 2025 as a foundational framework rather than a comprehensive solution. The field would benefit from developing a SPIRIT extension specifically tailored to the unique methodological considerations of nutritional science, addressing aspects such as dietary compliance biomarkers, control group design for complex dietary interventions, and standardized reporting of food composition and dietary assessment methodologies. Such specialized guidance would build upon the robust foundation of SPIRIT 2025 while addressing the particular evidence needs of nutrition science and policy.

Widespread adoption of SPIRIT 2025 within the nutritional research community has the potential to significantly enhance the quality, transparency, and clinical utility of trial evidence, ultimately strengthening the foundation of evidence-based nutritional recommendations and public health policy [1] [2] [3]. By embracing both the letter and spirit of these updated guidelines, nutritional researchers can address historical methodological limitations and produce more reliable, replicable, and impactful science.

Nutritional intervention research is fundamental to establishing causal links between diet and health, informing public health guidelines, and shaping dietary recommendations for populations [7]. Unlike pharmaceutical trials, nutritional research encompasses a broad spectrum of interventions, from isolated single nutrients to comprehensive dietary patterns, each presenting unique methodological challenges and considerations [7]. These interventions play a pivotal role in determining dietary requirements and understanding the role of supplementation for specific health outcomes.

The complexity of these interventions is amplified by factors such as the baseline nutritional status of participants, the difficulty of creating appropriate control groups, and the practical challenges of blinding participants to dietary changes [7]. This document outlines the core frameworks and protocols for designing rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) across the spectrum of nutritional interventions, providing researchers with a structured approach to this critical area of clinical investigation.

Classifying Nutritional Interventions

Nutritional interventions in clinical research can be categorized along a continuum of complexity. The table below summarizes the primary categories, their key characteristics, and associated research challenges.

Table 1: Classification of Nutritional Interventions in Clinical Research

| Intervention Category | Description | Common Study Designs | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Nutrient/Compound | Investigation of an isolated micronutrient (e.g., Vitamin D, Selenium) or bioactive compound (e.g., coenzyme Q10) [7] [8]. | Double-blind RCTs, Depletion-repletion studies [7]. | Bioavailability influenced by form and matrix; baseline nutrient status of participants confounds outcomes [7]. |

| Dietary Supplement | Use of nutritional supplements, often combining multiple vitamins, minerals, or amino acids [9]. | RCTs, often as adjunct therapy to standard treatment [9]. | Standardizing "standard of care" for control groups; ensuring blinding; accounting for polypharmacy [7] [9]. |

| Whole Food/Food Group | Addition or subtraction of specific whole foods (e.g., walnuts, almonds) or food groups [8]. | RCTs, Controlled feeding studies, Parallel-group trials [10] [8]. | Difficult to isolate active compound; ensuring dietary compliance without full control of diet. |

| Macronutrient Modification | Alteration of the proportion of protein, fat, or carbohydrate in the diet [7]. | RCTs, Metabolic balance studies, Cross-over trials. | Inevitable displacement of other macronutrients; confounding by simultaneous caloric intake changes [7]. |

| Complex Dietary Pattern | Implementation of a holistic dietary regimen (e.g., Mediterranean Diet, DASH Diet) [7] [8]. | RCTs, Cluster-randomized trials, Community-based participatory research. | Extreme difficulty with participant blinding; high logistical burden; ensuring cultural appropriateness and compliance [7] [10]. |

The choice of intervention type directly influences the study design, logistical planning, and interpretation of results. For instance, while single-nutrient studies more easily facilitate blinding and mechanistic insights, complex dietary pattern studies often have greater direct applicability to public health messaging [7].

Methodological Framework and Experimental Protocols

Core Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow for developing and implementing a nutritional intervention trial, from conceptualization through to analysis.

Figure 1. High-level workflow for nutritional intervention trials.

Detailed Protocol for a Complex Dietary Pattern Intervention

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in studies like the Dietary Approaches for Stopping Hypertension (DASH) trial [7].

1. Background & Objectives: Complex dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean or DASH diet, are associated with improved health outcomes. This protocol aims to evaluate the effect of a specific dietary pattern on a primary health endpoint (e.g., blood pressure, telomere length) compared to a control diet [7] [8].

2. Study Design:

- Design: Randomized Controlled Trial, parallel-group design.

- Duration: Typically a minimum of 12 weeks to observe meaningful changes in many physiological endpoints, though longer durations (6 months or more) are often necessary for outcomes like telomere length [9] [8].

- Setting: The study can be conducted as a controlled feeding study or as a behavioral intervention with intensive dietary counseling, depending on resources and the need for dietary control [7].

3. Participants:

- Inclusion Criteria: Defined based on the study population of interest (e.g., adults with pre-hypertension, healthy elderly for aging studies). Age, gender, and health status criteria should be explicitly stated [10] [8].

- Exclusion Criteria: Often include conditions that significantly alter nutrient metabolism (e.g., renal disease, malabsorption disorders), use of medications interfering with the primary outcome, or pre-existing dietary practices that align too closely with the intervention diet [9].

- Sample Size: Calculated based on the primary outcome, expected effect size, power (typically 80-90%), and significance level (α = 0.05). A power calculation is mandatory for publication in leading journals [11] [12].

4. Intervention & Control:

- Intervention Group: Receives the defined complex dietary pattern (e.g., high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy; reduced saturated fat). In a feeding study, all meals are provided. In a behavioral intervention, participants receive detailed meal plans, recipes, and intensive counseling [7] [10].

- Control Group: Receives a control diet, typically representative of a typical local diet or a alternative dietary pattern for comparison. The control diet must be designed to be distinct from the intervention diet in the key components of interest [7].

- Blinding: While true blinding of participants is nearly impossible in whole-diet studies, outcome assessors and data analysts should be blinded to group assignment [7].

5. Outcome Measures:

- Primary Outcomes: Align directly with the main research objective (e.g., change in systolic blood pressure, change in telomere length measured using standardized assays like qPCR) [9] [8].

- Secondary Outcomes: Can include biomarkers of compliance (e.g., urinary sodium for a low-sodium diet, plasma carotenoids for fruit/vegetable intake), quality of life measures, and other relevant health parameters [10] [9].

6. Data Collection & Management:

- Baseline & Follow-up: Collect demographic, anthropometric, clinical, and biochemical data at baseline and specified intervals during the study.

- Dietary Compliance: In feeding studies, compliance is monitored by requiring participants to consume all provided food. In behavioral interventions, use 24-hour dietary recalls, food frequency questionnaires, or food diaries, combined with biomarker analysis [7].

- Statistical Analysis: Specify methods a priori. Report p-values to two decimal places (e.g., P = .04), with values close to .05 reported to three places (e.g., P = .053). P values less than .001 should be reported as P < .001 [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and tools required for conducting high-quality nutritional intervention research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nutritional Interventions

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Assay Kits | ELISA kits for vitamins (e.g., 25-hydroxy Vitamin D), hormones, inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α). | Quantifying nutrient status and measuring secondary biochemical endpoints related to inflammation and oxidative stress [9] [8]. |

| Telomere Length Assay Kits | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) kits for relative telomere length measurement. | Assessing a biomarker of biological aging as a primary or secondary outcome in long-term nutritional studies [8]. |

| Validated Questionnaires | Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ), Sports Nutrition Knowledge (SNK) questionnaires, Quality of Life surveys (e.g., SF-36). | Assessing baseline dietary intake, monitoring compliance, and evaluating knowledge or patient-reported outcomes [10] [9]. |

| Dietary Supplement Formulations | Pharmaceutical-grade nutrient supplements (e.g., folic acid, vitamin D3, coenzyme Q10). | Serving as the active intervention in single-nutrient or dietary supplement trials; requires careful characterization of form and dosage [7] [9]. |

| Placebo Formulations | Microcrystalline cellulose pills, matched liquid placebos. | Creating a blinded control for supplement trials; must be identical in appearance, taste, and packaging to the active supplement [7]. |

| Sodium new houttuyfonate | Sodium New Houttuyfonate for Research | Research-grade Sodium New Houttuyfonate for studying antifungal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human use. |

| 4-Aminohippuric-d4 Acid | 4-Aminohippuric-d4 Acid, MF:C9H10N2O3, MW:198.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Special Considerations and Reporting Standards

Ethical and Logistical Challenges

Nutritional research faces several unique hurdles. A central ethical consideration is the definition of an appropriate control, especially when a nutrient is essential or a dietary pattern is believed to be beneficial. Withholding a potentially beneficial intervention from a control group known to be deficient poses an ethical dilemma for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) [7]. Furthermore, baseline nutritional status can greatly influence the response to an intervention, as nutrients often have threshold effects beyond which no further benefit is observed. This necessitates careful screening and assessment of participants at baseline [7].

Logistically, providing entire diets or specific whole foods requires significant infrastructure for food procurement, preparation, and storage. Participant compliance is a higher bar than in drug trials, as the intervention must be appealing and culturally acceptable to be sustained [7] [10].

Pathway of Intervention Effect and Outcome Measurement

The mechanistic path from a nutritional intervention to a measured health outcome involves multiple biological systems, especially in complex interventions.

Figure 2. Pathway from nutritional intervention to health outcome.

Mandatory Reporting Guidelines

To ensure transparency, reproducibility, and quality, nutritional intervention research must adhere to international reporting standards. The following table outlines the critical guidelines.

Table 3: Essential Reporting Guidelines for Nutritional Intervention Research

| Study Type | Reporting Guideline | Primary Purpose | Key Reporting Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trial (Completed) | CONSORT | To provide a checklist for transparent reporting of trial methods, results, and conclusions. | Flow diagram, randomization method, blinding, participant flow, baseline data, outcome estimates. |

| Randomized Controlled Trial (Protocol) | SPIRIT | To define standard protocol items for clinical trials to ensure completeness. | Background, rationale, objectives, trial design, methods, ethics, dissemination plans [11]. |

| Systematic Review | PRISMA | To ensure the transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. | Search strategy, study selection process, risk of bias assessment, synthesis methods [9]. |

Furthermore, clinical trials must be registered in a publicly accessible registry such as ClinicalTrials.gov or a WHO-approved primary registry before participant enrollment begins [11] [12]. Authors should also follow the SAGER guidelines to promote appropriate sex and gender equity in their research [12].

Designing rigorous nutritional interventions requires careful consideration of the intervention type, from single nutrients to complex diets, and a thorough understanding of the associated methodological challenges. By adhering to established experimental protocols, utilizing appropriate tools and reagents, and complying with international reporting standards, researchers can generate high-quality, reliable evidence. This evidence is crucial for advancing the field of clinical nutrition and translating research findings into effective public health guidance and clinical practice. Future research will benefit from larger-scale, longer-term trials that address the current limitations of high heterogeneity and risk of bias, particularly in emerging areas like nutritional psychiatry and nutrigerontology [9] [8].

Nutrition research, particularly in the design and implementation of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), faces a distinct set of complexities not typically encountered in pharmaceutical research. These challenges stem from the inherent nature of dietary interventions, which involve complex matrices of interacting components, are influenced by the pre-existing dietary status of participants, and are deeply embedded within socio-cultural contexts that shape food behaviors [13]. The physiological effects of a food are not solely determined by its gross chemical composition but are significantly modified by its physical structure, the combination of foods consumed, and an individual's cultural background and nutritional starting point [14] [13]. This Application Note details these unique challenges and provides structured protocols to enhance the rigor, reproducibility, and translatability of nutritional RCTs.

The Food Matrix Effect

Concept and Significance

The food matrix is defined as the intricate micro- and macro-structural organization of food components within a whole food. This structure can significantly alter the bioavailability, absorption, and metabolic fate of nutrients compared to when the same nutrients are consumed in an isolated, purified form [14]. For example, the same load of fats, sugars, or proteins can elicit different metabolic responses depending on the food's physical form (solid vs. liquid), texture (hard vs. soft), and cellular integrity [14]. A key illustration is the difference between consuming whole almonds (with an intact cell wall structure) and almond oil; the matrix of the whole nut reduces the bioaccessibility of lipids, thereby lowering the effective energy absorbed [14]. Ignoring the matrix effect can lead to misinterpretations of a food's health impact and flawed public health recommendations.

Experimental Protocol for Investigating the Matrix Effect

Objective: To compare the metabolic response (e.g., postprandial glycemia, insulinemia, or satiety hormones) to a nutrient delivered in two different physical forms: a whole food and an isolated/matched formulation.

Methodology:

- Selection of Test Foods: Choose a whole food of interest (e.g., an apple) and create a matched liquid formulation (e.g., apple juice) with an equivalent macronutrient and fiber profile based on chemical analysis.

- Study Population: Recruit healthy participants (e.g., n=20-25) to achieve adequate power. Participants should be randomized and act as their own controls in a crossover design.

- Intervention: After an overnight fast, participants consume the test meals on two separate visits:

- Visit 1: Whole food meal.

- Visit 2: Matched formulation meal.

- A washout period of at least 3 days should separate the visits.

- Data Collection:

- Blood Samples: Collect at baseline (fasting), 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes postprandially. Analyze for relevant metabolites (glucose, insulin, GLP-1, etc.).

- Satiety Assessment: Use Visual Analog Scales (VAS) to measure hunger, fullness, and prospective food consumption at the same time points.

- Oral Processing: Record eating rate (g/min) and number of chews for the solid meal.

Data Analysis: Compare the area under the curve (AUC) for blood metabolites and satiety scores between the two test conditions using paired t-tests. Correlate oral processing parameters with metabolic outcomes.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for a crossover study designed to isolate and measure the food matrix effect on metabolic responses.

Research Reagent Solutions for Matrix Studies

Table 1: Key Materials and Reagents for Food Matrix Research

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Diets | Meals with precisely defined composition and form (liquid, solid, semi-solid). | Isolating the effect of food form on satiety and energy intake [14]. |

| In Vitro Digestion Models | (e.g., INFOGEST) Simulated gastrointestinal environments. | Predicting nutrient bioaccessibility from different food structures [14]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | (e.g., from NIST) Certified food materials with known composition. | Validating analytical methods for nutrient analysis in complex foods. |

| Textural Profile Analyzer | Instrument to quantitatively measure hardness, cohesiveness, springiness. | Objectively characterizing food texture to correlate with oral processing [14]. |

Baseline Nutritional Status

Concept and Significance

The baseline nutritional status of a study participant refers to their body's existing reserves and circulating levels of the nutrient under investigation prior to the intervention. This status is a critical moderator of the intervention's effect [13]. A supplementation trial may show a significant effect in a deficient population but no effect—or even a negative effect—in a replete population. This is a fundamental difference from most drug trials, where the drug is a novel exogenous compound. Factors such as subclinical deficiencies, genetic polymorphisms affecting nutrient metabolism, and habitual dietary intake can create high inter-individual variability in response, obscuring the true efficacy of an intervention [13].

Protocol for Assessing and Stratifying by Baseline Status

Objective: To determine if the efficacy of a nutritional intervention depends on the participants' baseline status of the nutrient of interest.

Methodology:

- Screening and Recruitment: Screen potential participants using a biomarker of status for the nutrient of interest (e.g., plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D for vitamin D, serum ferritin for iron).

- Pre-Defined Stratification: Pre-define cutoff points for "low," "normal," and "high" status based on established clinical guidelines.

- Randomization: Within each stratification group, randomly assign participants to the intervention or control group. This ensures balanced groups for analysis.

- Intervention: Administer the nutrient supplement or placebo for the predefined study period.

- Outcome Measurement: Assess the primary outcome (e.g., change in a functional endpoint like insulin sensitivity or a disease biomarker) at the end of the study.

Data Analysis: Use an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with the final outcome as the dependent variable, treatment group as a fixed factor, and baseline nutrient status as a covariate. Test for a significant interaction term between treatment group and baseline status.

Table 2: Impact of Baseline Status on Intervention Outcomes: A Hypothetical Example

| Nutrient | Population with Deficient Baseline | Population with Adequate Baseline | Implication for Trial Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | Significant improvement in insulin sensitivity after supplementation. | No significant change or minimal improvement. | Failure to stratify may lead to conclusion of "no overall effect" [13]. |

| Iron | Marked increase in hemoglobin and reduction in fatigue. | No change in hemoglobin; risk of iron overload. | Safety and efficacy are contingent on baseline status. |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Greater reduction in inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP). | Muted anti-inflammatory response. | Baseline dietary intake (e.g., fish consumption) must be assessed. |

Figure 2: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial incorporating pre-stratification of participants based on baseline nutritional status to account for its modulating effect.

Socio-Cultural Influences on Dietary Behavior

Concept and Significance

Dietary practices are not merely biological but are deeply rooted in socio-cultural norms, traditions, and gender roles. These factors profoundly influence food choices, meal patterns, and the acceptability of dietary interventions [15] [16]. A one-size-fits-all approach in nutrition research is likely to fail if it does not account for these influences. For instance, a study in rural Bangladesh found that gendered norms limited adolescent girls' participation in physical activity and shaped their access to certain foods, while taste preferences and the popularity of street foods heavily influenced adolescent diets [15]. Overlooking these factors can lead to poor adherence in trials and render effective interventions unimplementable in real-world settings.

Protocol for Integrating Socio-Cultural Context into RCTs

Objective: To design a dietary intervention that is culturally appropriate and acceptable, thereby maximizing adherence and real-world applicability.

Methodology (Mixed-Methods Approach):

- Formative Qualitative Research (Pre-Trial):

- Conduct Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and semi-structured interviews with members of the target community (including different genders, ages, and socio-economic groups) [15].

- Themes to Explore: Common foods and meals, perceptions of "healthy" food, barriers and facilitators to dietary change, typical eating patterns, and gender roles in food procurement and preparation.

- Intervention Co-Development: Use the qualitative findings to adapt the intervention. This may involve:

- Modifying recommended foods to align with local availability and preferences.

- Tailoring educational materials to align with local health beliefs and language.

- Scheduling intervention activities around culturally important events or daily routines.

- Quantitative RCT with Embedded Process Evaluation:

- Implement the co-developed RCT.

- Monitor Adherence: Use culturally appropriate tools (e.g., locally validated food frequency questionnaires, photographic food records).

- Process Evaluation: Conduct follow-up interviews or surveys to understand participants' experiences, perceived barriers, and facilitators.

Data Analysis: Integrate qualitative and quantitative data. Thematic analysis for qualitative data; standard statistical methods for quantitative outcomes. Compare adherence and outcomes with historical controls or less tailored interventions.

Research Toolkit for Socio-Cultural Investigations

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Socio-Cultural Research in Nutrition

| Methodology | Function | Application in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Focus Group Discussions | To explore group norms, shared beliefs, and common practices. | Understanding collective perceptions of healthy body image or barriers to buying fruits and vegetables [15]. |

| Semi-Structured Interviews | To gain in-depth, individual-level insights and personal experiences. | Exploring an individual's journey with weight management or specific dietary restrictions. |

| Dietary Acculturation Scales | To measure the adoption of dietary patterns from a new culture. | Studying how immigration affects diet-related disease risk. |

| Participatory Mapping | To visually document food sources and food environments within a community. | Identifying "food deserts" and barriers to accessing healthy foods. |

| Cetrimonium bromide-d42 | Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Bromide-d42 | Research-grade Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Bromide-d42 for advanced studies. Applications include NMR, mechanism analysis, and nanoparticle synthesis. For Research Use Only. |

| Swietemahalactone | Swietemahalactone, MF:C27H30O10, MW:514.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For researchers designing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for nutritional interventions, navigating the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory landscape is crucial. The foundational principle governing this space is the distinction between a dietary supplement and a drug, which is determined primarily by intended use as established in the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [17]. A substance is regulated as a drug if it is intended for use in the "diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease" [17]. Conversely, dietary supplements are intended to supplement the diet and must not be represented for disease treatment or prevention.

This distinction becomes critically important when designing clinical trials. Any clinical investigation designed to evaluate a product's effect on the structure or function of the body for disease treatment transforms the product into an investigational drug in the eyes of the FDA, requiring an Investigational New Drug (IND) application [17]. This regulatory framework ensures patient safety and scientific validity while presenting researchers with specific compliance requirements.

IND Requirements for Dietary Intervention Studies

When an IND is Required

The necessity for an IND application hinges entirely on the study's intent and endpoints. Research involving dietary ingredients or supplements may require an IND if it investigates disease outcomes, even if the product is lawfully marketed as a supplement outside the research context.

Case Study: Relaxium Sleep: A recent FDA warning letter illustrates this critical distinction. A sponsor conducted "Protocol ABRI-002 on Relaxium Sleep in insomnia subjects without an IND" [17]. The sponsor argued that the product was "marketed as a supplement, not a drug," and that "studying effects on sleep doesn't make it a drug" [17]. The FDA explicitly disagreed, stating that "measuring treatment endpoints constitutes intended use as drug" [17]. The outcome was a warning letter demanding "immediate corrective actions, including IND submission" [17]. This case underscores that investigating a dietary supplement for effects on a disease condition (insomnia) without an IND constitutes a violation of FDA regulations.

Table: Determining IND Requirement for Dietary Intervention Studies

| Study Characteristic | IND Likely Required? | Regulatory Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Endpoint: Diagnosis, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of a disease | Yes | Meets statutory definition of "drug" [17] |

| Endpoint: Effect on structure/function without disease reference | No | Consistent with dietary supplement claims |

| Intent: To establish therapeutic effect | Yes | Creates a new drug indication |

| Intent: To characterize nutritional effects | No | Consistent with supplement labeling |

| Population: Patients with specific disease | Yes | Implies disease treatment intent |

| Population: Healthy volunteers | No (but context-dependent) | More consistent with supplement research |

Consequences of Non-Compliance

Failure to submit a required IND application can result in serious regulatory consequences:

- FDA Warning Letters: Official agency communication demanding immediate corrective action [17]

- Clinical Hold: Order to delay or suspend the proposed clinical investigation [17]

- Data Invalidation: Collected study data may be deemed unusable for regulatory submissions [17]

- Resource Depletion: Wasted financial and temporal investments in non-compliant research [17]

FDA Guidance Agenda for Human Foods and Dietary Supplements

2025 Human Foods Program Guidance

The FDA's Human Foods Program has published its proposed 2025 guidance agenda, highlighting priority topics for the agency. While this list represents planned guidance and does not carry legally enforceable requirements, it signals critical areas for researcher awareness [18].

Key topics relevant to dietary intervention researchers include:

- Action Level for Opiate Alkaloids on Poppy Seeds: Draft Guidance for Industry

- Food Colors Derived from Natural Sources: Fruit Juice and Vegetable Juice as Color Additives in Food; Draft Guidance for Industry

- New Dietary Ingredient Notifications and Related Issues: Identity and Safety Information About the NDI: Guidance for Industry [18]

The FDA acknowledges this list is not exhaustive and may issue additional guidance not currently identified. The agency welcomes public comments on these topics through Regulations.gov using Docket FDA-2022-D-2088 [18].

New Dietary Ingredient (NDI) Notification Framework

The FDA is continuing its "piecemeal approach" to finalizing the NDI guidance, with significant developments expected in 2025 [19]. The NDI notification process requires manufacturers to submit safety data to the FDA for any dietary ingredient not marketed in the U.S. before October 15, 1994 [19].

Recent developments include:

- March 2024: FDA released final guidance "Dietary Supplements: New Dietary Ingredient Notification Procedures and Timeframes: Guidance for Industry" [19]

- April 2024: FDA issued draft guidance "New Dietary Ingredient Notification Master Files for Dietary Supplements" [19]

- June 2025: FDA released educational videos and a supplemental fact sheet to boost awareness of the NDIN review process [19]

Outstanding issues that may be addressed in upcoming guidance include "synthetic botanicals, toxicology testing and so on and so forth" [19]. For researchers studying new dietary ingredients, compliance with NDI notification requirements is essential, particularly when the research involves ingredients not previously marketed in the U.S.

Specific Ingredient Considerations

N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC)

The FDA is working toward "rulemaking to provide by regulation that an ingredient is not excluded from the dietary supplement definition," which is widely expected to address NAC [19]. Despite being used in supplements since the early 1990s, the FDA previously declared NAC not a legal dietary ingredient due to prior approval as a drug in 1963 [19]. The agency currently exercises enforcement discretion, allowing NAC supplement sales provided they do not make "non-compliant disease claims" [19]. Formal rulemaking is anticipated to provide more stable regulatory footing.

Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN)

For NMN, the FDA has stated it "does not intend to prioritize enforcement action" related to NMN-containing dietary supplements, pending resolution of a Citizen Petition filed by the Natural Products Association and the Alliance for Natural Health [19]. This enforcement discretion is contingent upon the absence of new safety concerns [19].

Application Notes for RCT Protocol Development

Regulatory Assessment Protocol

Researchers should implement a systematic approach to determining IND requirements during trial design. The following workflow outlines key decision points:

RCT Design Considerations for Dietary Interventions

Randomized controlled trials represent the "gold standard for effectiveness research" because "randomization reduces bias and provides a rigorous tool to examine cause-effect relationships between an intervention and outcome" [20]. For nutritional interventions, several design considerations are particularly important:

- Blinding: "RCTs are often blinded so that participants and doctors, nurses or researchers do not know what treatment each participant is receiving, further minimizing bias" [20]. Effective blinding can be challenging with dietary interventions but is crucial for validity.

- Population Selection: "Participants who enroll in RCTs differ from one another in known and unknown ways that can influence study outcomes" [21]. Careful inclusion/exclusion criteria are essential.

- Control Group Design: Selection of appropriate control (placebo, active comparator, or standard care) must be scientifically and ethically justified [21].

Table: RCT Design Configurations for Dietary Interventions

| Design Type | Description | Applications in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Parallel-group | Each participant randomly assigned to one group; all group members receive same intervention [21] | Most common design; suitable for most supplement efficacy studies |

| Crossover | Participants receive multiple interventions in random sequence [21] | Useful for studying short-term metabolic effects; requires washout periods |

| Cluster | Pre-existing groups (communities, schools) randomly selected [21] | Ideal for population-level dietary interventions or educational programs |

| Factorial | Participants assigned to groups receiving different intervention combinations [21] | Efficient for studying multiple nutrient interactions |

| Stepped-wedge | Sequential crossover of clusters from control to intervention [21] | Appropriate for phased implementation of dietary programs |

Compliance Documentation Framework

Researchers should maintain comprehensive documentation to demonstrate regulatory compliance:

- Protocol Intent Documentation: Clear statements of research objectives consistent with supplement research parameters

- Endpoint Justification: Scientific rationale for selected endpoints avoiding disease claims

- Labeling and Informed Consent Review: Ensure all participant-facing materials avoid therapeutic claims

- Substantiation Records: For any "healthy" content claims, manufacturers "must make and keep written records substantiating the 'healthy' claims" under new FDA requirements [22]

Experimental Protocols for Complimentary Dietary Intervention Research

Dietary Supplement Safety and Bioavailability Study Protocol

This protocol outlines a compliant approach for studying dietary supplements without triggering IND requirements.

Objective: To evaluate the safety, tolerability, and bioavailability of [DIETARY INGREDIENT] in healthy adult volunteers.

Primary Endpoints:

- Plasma/serum concentrations of [ACTIVE COMPONENTS] over 24 hours

- Incidence and severity of adverse events

- Vital sign measurements (blood pressure, heart rate)

Secondary Endpoints:

- Participant-reported quality of life measures

- Compliance with supplementation regimen

Methodology:

- Design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group

- Participants: 50 healthy adults, aged 18-65 years

- Intervention: [DIETARY INGREDIENT] or matching placebo for 30 days

- Assessments: Blood sampling at baseline, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours post-dose on day 1 and day 30; daily symptom diaries; vital signs at each study visit

Regulatory Status: This study does not require an IND as it investigates safety and bioavailability in healthy volunteers, not disease treatment or prevention.

Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Intervention Studies

Table: Essential Materials for Dietary Intervention RCTs

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Investigational Product | Consistent formulation and dosage across study period | Ensures product quality and reliability of results |

| Placebo Matching Investigational Product | Participant and investigator blinding | Minimizes bias in outcome assessment |

| Dietary Assessment Tools (e.g., 24-hour recall, FFQ) | Measures background dietary intake | Controls for confounding from habitual diet |

| Biological Sample Collection Kits | Standardized specimen processing | Ensures sample integrity for biomarker analysis |

| Compliance Measures (e.g., pill counts, biomarkers) | Verifies participant adherence to protocol | Critical for validity of intention-to-treat analysis |

| Adverse Event Documentation Forms | Systematic safety monitoring | Meets ethical and regulatory requirements for participant protection |

CONSORT Guidelines Implementation

Proper reporting of RCTs is essential for research validity and translation. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines provide an evidence-based framework for transparent reporting [23]. Key elements for dietary intervention studies include:

- Participant Flow Diagram: "Documentation of the flow of the trial participants using a diagram" is recommended by Item 13 of CONSORT guidelines [23]. This should include:

- Number of participants assessed for eligibility

- Randomly allocated to each group

- Receiving intended intervention

- Completing study protocol

- Included in primary analysis

- Loss to Follow-up Documentation: "Reasons for loss to follow-up and exclusions from the RCT analysis were poorly reported" in many trials [23]. Comprehensive reporting of attrition reasons is methodologically crucial.

- Trial Registration: All RCTs "should be registered with a clinical trials database" [20] such as ClinicalTrials.gov prior to participant enrollment.

Navigating the FDA regulatory framework for dietary intervention research requires careful attention to the distinction between dietary supplement and drug research. The fundamental determinant is intended use, with studies designed to investigate disease diagnosis, treatment, or prevention requiring IND applications [17]. Researchers should implement systematic regulatory assessments during trial design, maintain comprehensive documentation, and adhere to methodological standards including CONSORT guidelines for reporting [23]. With the FDA's 2025 guidance agenda highlighting continued focus on human foods and dietary supplements [18], researchers must remain current with evolving regulatory expectations to ensure compliant and scientifically valid research protocols.

Ethical Considerations and Documentation Standards in Nutrition Research

Core Ethical Principles in Human Nutrition Research

Respect for participant autonomy, transparency, and accountability form the foundational ethical pillars for conducting rigorous and trustworthy nutrition research [24].

Participant Rights and Autonomy

- Informed Consent: Researchers must provide clear, concise information about the study's purpose, methods, potential risks, benefits, and participant responsibilities. Participants must understand their right to refuse or withdraw from the study without penalty [24].

- Protection of Confidential Information: Researchers have a duty to protect participant data through secure storage, transmission methods, limited access to authorized personnel, and anonymization where possible, complying with regulations like GDPR [24].

- Withdrawal Mechanisms: Clear, accessible processes must allow participants to withdraw from the study at any time, without affecting their care or treatment. Withdrawn data should be anonymized per protocol [24].

Transparency and Accountability

- Clear Disclosure: Research methods, outcomes, and limitations must be presented clearly, avoiding technical jargon to ensure findings are accessible [24].

- Accurate Representation: Researchers must avoid selective reporting or data manipulation, acknowledge potential biases or errors, and discuss findings' implications and limitations honestly [24].

- Complaint Mechanisms: Establish clear, timely processes for participants to report concerns or complaints, with transparent resolution and corrective actions [24].

Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technologies

The application of AI in nutrition and behavior change introduces unique ethical challenges, requiring domain-specific frameworks to ensure trustworthy systems [25]. Key issues include:

- Algorithmic Bias: AI systems trained on unrepresentative datasets (e.g., non-Western dietary patterns, historical under-representation of women in trials) risk perpetuating biases and widening health inequalities [25].

- Black Box Problem: Lack of transparency and explainability in AI systems can erode trust. Expert scrutiny and validation are essential [25].

Table 1.1: Key Ethical Challenges and Mitigation Strategies in Nutrition Research

| Ethical Challenge | Potential Consequences | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Coercion & Undue Influence | Compromised autonomy, invalid consent | Clear consent processes emphasizing voluntary participation; no penalty for refusal/withdrawal [24]. |

| Data Privacy Breaches | Loss of confidentiality, participant harm | Data anonymization; secure storage; compliance with data protection regulations (e.g., GDPR) [24]. |

| Unrepresentative Datasets | Biased algorithms, skewed results, widening health inequalities | Ensure diverse participant recruitment; include varied dietary patterns and nutritional needs [25]. |

| Lack of AI Transparency | Unexplainable recommendations, eroded trust | Implement explainable AI (XAI) principles; external validation of AI systems [25]. |

Figure 1.1: Comprehensive Ethics Framework for Nutrition Research

Documentation and Reporting Standards for Nutritional RCTs

Adherence to standardized documentation and reporting protocols is critical for ensuring scientific rigor, reproducibility, and transparency in nutritional intervention research.

Protocol Development and Registration

Ahead of trial commencement, researchers should develop and register a detailed protocol, as demonstrated by a systematic review on nutritional supplementation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) [9] [26]. Key protocol elements include:

- Background and Rationale: Justify the research question and its significance within current evidence gaps. For example, the OCD review notes standard treatments often provide incomplete symptom relief, warranting investigation into nutritional adjuncts [9].

- Pre-defined Methodology:

- Eligibility Criteria: Define study designs, participant characteristics (e.g., adults ≥18 years with DSM-5 diagnosed OCD), interventions, comparators, and outcomes using frameworks like PICO [9].

- Primary and Secondary Outcomes: Specify primary outcomes (e.g., cognition, quality of life, psychiatric symptoms) and secondary outcomes (e.g., comorbidities) with identified measurement tools (e.g., Stroop Test, SF-36) [9].

- Search Strategy: Detail electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL), search terms, and timelines without date or language restrictions [9].

- Registration: Publicly register the protocol in repositories like Open Science Framework (OSF) to enhance transparency and reduce reporting bias [9] [26].

Systematic Review Methodology

The Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) methodology, used by the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, provides a gold-standard framework [27]:

- Protocol-driven Approach: Develop a pre-specified protocol for all review stages [27].

- Comprehensive Search and Screening: Systematic searches across multiple databases, with duplicate independent screening of citations and full-text articles [9] [27].

- Data Extraction and Risk of Bias: Standardized data extraction from included studies, with independent assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias using validated tools [9] [27].

- Evidence Synthesis and Grading: Synthesize evidence, develop conclusion statements, and grade the strength of evidence [27].

- Peer Review: The 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee's systematic reviews underwent external peer review coordinated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [27].

Table 2.1: Essential Documentation Elements for Nutritional RCT Protocols

| Protocol Section | Key Components | Reporting Standards & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Study Objectives | Primary & secondary research questions | PICO framework; clearly defined hypotheses [9]. |

| Intervention | Supplement details (type, dose, frequency); administration method; quality control (e.g., DSID) [28] | Use Dietary Supplement Ingredient Database (DSID) for predicted ingredient levels [28]. |

| Comparator | Placebo or active control; co-interventions allowed in both groups | Ensure comparators are clearly defined and justified [9]. |

| Outcomes | Primary & secondary outcomes; specific measurement tools & timepoints | Validated instruments (e.g., Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale) [9]. |

| Sample Size | Justification via power calculation; enrollment targets | Detail statistical power, alpha, effect size, and expected attrition [9]. |

| Randomization & Blinding | Randomization procedure; allocation concealment; blinding methods | Specify who is blinded (participants, intervenors, outcome assessors) [9]. |

| Data Management | Data collection methods; confidentiality measures; statistical analysis plan | Secure storage; pre-specified analysis plan for primary outcomes [24]. |

| Ethical Compliance | Ethics approval; informed consent process; data safety monitoring board | IRB approval number; consent documentation process [24]. |

Figure 2.1: Systematic Review Workflow per NESR Methodology

Quantitative Data Presentation in Nutrition Research

Effective presentation of quantitative data is essential for clear communication of research findings. The choice of graphical representation depends on the type of data and the research question [29] [30].

Data Tabulation and Frequency Distributions

Tabulation is the foundational step before data analysis, requiring design principles for clarity [31]:

- Frequency Tables: For quantitative data, create class intervals of equal size to group data. The number of classes should typically be 5-16 for optimal presentation. Calculate the range (highest-lowest value) and divide into subranges [29] [31].

- Table Design Principles:

Graphical Data Representation

- Histograms: Used for displaying frequency distributions of continuous quantitative data. The horizontal axis is a numerical scale with contiguous, touching bars where area represents frequency [29] [31].

- Frequency Polygons: Created by joining the midpoints of the tops of the bars in a histogram, useful for comparing multiple distributions on the same diagram [29] [31].

- Line Diagrams: Illustrate time trends of an event (e.g., birth rates, disease incidence) with time on the horizontal axis [31].

- Scatter Diagrams: Display correlation between two quantitative variables, with points indicating values for each subject [31] [30].

- Bar Charts: Suitable for categorical data (nominal or ordinal) where bars do not touch. For continuous data, use histograms with touching bars [29] [30].

Table 3.1: Selection Guide for Quantitative Data Visualizations

| Data Type | Research Question | Recommended Visualization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous (e.g., weight, blood levels) | Distribution of values | Histogram | Bars must be touching; area represents frequency [29]. |

| Continuous (multiple groups) | Compare distributions | Frequency Polygon | Plot multiple lines on same axes for comparison [29] [31]. |

| Continuous over Time | Trend analysis | Line Diagram | Time on X-axis; connect data points with straight lines [31]. |

| Two Continuous Variables | Relationship/Correlation | Scatter Diagram | X and Y axes for the two variables; pattern shows correlation [31] [30]. |

| Categorical (e.g., supplement type) | Compare values between categories | Bar Chart | Bars should not touch; space between categories [29] [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Nutritional Intervention Research

Defining Study Parameters

The OCD systematic review protocol exemplifies rigorous methodology for nutritional intervention research [9]:

- Participant Eligibility: Apply strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. For example: adults ≥18 years with DSM-5 diagnosed OCD; exclude organic OCD causes, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or significant comorbid conditions [9].

- Intervention and Comparator Specification:

- Outcome Measurement:

- Primary: Changes in cognitive performance (validated instruments: Stroop Test, Trail-Making Test), quality of life (SF-36, Functional Assessment Short Test), and psychiatric symptoms (depression, anxiety, obsession/compulsion scales) [9].

- Secondary: Presence of comorbidities (e.g., metabolic syndrome) measured using standardized indices (Charlson Comorbidity Index) [9].

- Trial Duration and Follow-up: Minimum 12-week intervention with at least 6-month follow-up to assess sustained effects [9].

Data Collection and Analysis Protocols

- Search Methodology: Comprehensive searches across multiple databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, ClinicalTrials.gov) from inception, without language or date restrictions. Include keywords for nutritional supplements, cognition, quality of life, psychiatric symptoms, and randomized studies [9].

- Study Selection Process: Dual independent screening of titles/abstracts, followed by full-text review. Document reasons for exclusion at full-text stage [9].

- Data Extraction and Synthesis: Independent extraction of study characteristics, methods, outcomes, and results. Calculate association measures with 95% confidence intervals. Analyze potential heterogeneity sources [9].

- Risk of Bias Assessment: Use validated tools (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Bias tool) to evaluate study quality. This is a critical component of NESR's gold-standard methodology [9] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5.1: Essential Resources for Nutritional Intervention Research

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Registries | Open Science Framework (OSF) | Publicly register study protocols to enhance transparency, reduce reporting bias, and establish precedence [9] [26]. |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols) | Standardized framework for reporting systematic review protocols, ensuring comprehensive methodology documentation [9]. |

| Data Sources | Dietary Supplement Ingredient Database (DSID) | Provides statistically predicted estimates of ingredient levels in dietary supplements, which may differ from labeled amounts; essential for quality control and intervention standardization [28]. |

| Statistical Tools | Dietary Index Analysis (R package) | Streamlines compilation of dietary intake data into index-based patterns, enabling assessment of adherence to dietary patterns in epidemiologic and clinical studies for precision nutrition [28]. |

| Large-Scale Studies | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | Provides comprehensive health and nutritional status data for US population; useful for baseline comparisons, power calculations, and epidemiological context [28]. |

| Ethical Framework | 7-Pillar Framework for AI in Nutrition | Domain-specific ethical guidelines for developing AI solutions in nutrition and behavior change, addressing transparency, bias prevention, and explainability [25]. |

| Apremilast-d5 | Apremilast-d5, MF:C22H24N2O7S, MW:465.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Linoleoyl Glycerol | 3-Linoleoyl-sn-glycerol|High-Purity Reference Standard |

Implementation Strategies: Designing and Executing Robust Nutritional Trials

Selecting Appropriate Control Groups and Comparators for Dietary Interventions

Within the framework of randomized controlled trial (RCT) protocols for nutritional interventions research, the selection of an appropriate control group is a fundamental methodological decision that directly impacts the validity, interpretability, and ethical integrity of a study. RCTs are considered the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy or safety of an intervention because their design—which involves the random allocation of participants to one or more comparison groups—minimizes selection bias and the influence of known and unknown confounding factors [21]. The control group provides the essential baseline against which the effects of the dietary intervention are measured [32]. Without a well-chosen control, it is impossible to determine whether observed changes are truly due to the intervention itself or to other external variables such as the passage of time, participant expectations, or concurrent changes in lifestyle or environment.

The choice of control group is particularly complex in dietary intervention studies. Unlike pharmaceutical trials, where a placebo pill can often be visually identical to the active drug, creating a truly blinded design for a dietary pattern, whole food, or nutrient-based intervention is frequently challenging, and sometimes impossible. This protocol document provides a detailed framework for selecting, designing, and implementing control groups and comparators for dietary interventions, ensuring that researchers can make informed decisions that strengthen the scientific rigor and practical applicability of their findings.

Theoretical Foundations: Types of Control Groups

The primary function of a control group is to answer the question: "Compared to what?" The optimal control condition depends on the specific research question, the stage of investigation (e.g., efficacy vs. effectiveness), and ethical considerations. The following table summarizes the common types of control groups used in dietary intervention trials, their applications, and key considerations.

Table 1: Types of Control Groups for Dietary Intervention Trials

| Control Type | Description | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Disadvantages & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo Control | Participants receive an inert intervention designed to be indistinguishable from the active intervention. | Testing a specific supplement, fortified food, or dietary component where a believable placebo can be manufactured. | Maximizes blinding; provides a strong measure of the specific physiological effect vs. the placebo effect. | Difficult or unethical to create for whole-diet or food-based interventions; requires validation that blinding was successful. |

| Usual Diet / No Intervention | Participants are asked to continue their habitual dietary intake without any changes. | Pragmatic trials aiming to measure the real-world effect of adding an intervention to typical behavior. | High external validity and practicality; avoids co-intervention. | Lack of blinding leads to high risk of performance and detection bias; cannot isolate placebo effects. |

| Attention Control | Participants receive a similar level of researcher interaction, education, or monitoring on a topic unrelated to the primary intervention. | Trials where the "dose" of attention or the behavioral support package is a key confounding variable. | Controls for the non-specific effects of participant engagement and regular monitoring. | Requires careful design of a credible alternative protocol; can be resource-intensive. |

| Active Comparator / Alternative Diet | Participants are assigned to a different, active dietary pattern for comparison (e.g., Standard American Diet vs. Mediterranean Diet). | Comparing the efficacy of two distinct dietary patterns or to test for non-inferiority. | Provides direct, clinically relevant comparative effectiveness data; can be more ethical if both diets are potentially beneficial. | Does not provide information on efficacy vs. no intervention; may require a larger sample size to detect differences between two active groups. |

| Wait-List Control | Participants in the control group are offered the intervention after a designated delay period, serving as their own control during the initial phase. | Studies where it is ethically permissible to delay a potentially beneficial intervention. | All participants eventually receive the intervention, which can aid recruitment and is often perceived as fair. | Contamination can occur if control participants seek out the intervention early; not suitable for long-term outcomes. |

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making pathway for selecting the most appropriate type of control group based on the research context.

Experimental Protocols for Control Group Implementation

Protocol: Designing and Validating a Placebo for a Nutritional Supplement

Objective: To create an inert substance that is sensorially identical to the active nutritional supplement to ensure participant and personnel blinding.

Materials:

- Active supplement (e.g., omega-3 capsule, probiotic sachet, protein powder).

- Placebo base materials (e.g., microcrystalline cellulose for capsules, maltodextrin for powders, olive oil for oil-based supplements).

- Food-grade colorants and flavorings.

- Encapsulation machine or powder packaging equipment.

- Standardized sensory evaluation forms.

Methodology:

- Formulation: Develop the placebo using the base material. Match the color, size, and shape of capsules/tablets. For powders, match the texture, color, solubility, and taste using inert ingredients and minimal, matched flavorings.

- Pilot Testing: Conduct a blinding validation study with a small panel of healthy volunteers (n=20-30). Present them with both active and placebo products in a randomized order and ask them to identify which is the active product.

- Success Criterion: Blinding is considered successful if the correct identification rate is not statistically different from 50% (chance) using a binomial test (p > 0.05).

- Packaging and Labeling: Package active and placebo products in identical, coded containers. A third party not involved in participant interaction or outcome assessment should hold the randomization code.

Protocol: Implementing an Attention Control Group

Objective: To control for the non-specific effects of participant contact time, education, and monitoring received by the intervention group.

Materials:

- Standardized educational materials on a neutral health topic (e.g., sleep hygiene, foot care, general health screenings).

- Identical session logs and monitoring tools as used in the intervention group.

- Trained personnel to deliver the control protocol.

Methodology:

- Session Structure: Match the number, duration, and format of counseling sessions between the intervention and attention control groups. For example, if the intervention group has eight sessions on Mediterranean diet cooking, the attention control group should have eight sessions on a matched, but neutrally-themed, topic.

- Participant Interaction: Maintain the same frequency of phone calls, text messages, or other forms of follow-up for both groups. The content should differ, but the level of attention and support should be perceived as equivalent by participants.

- Outcome Assessment: Use the same primary and secondary outcome measures for both groups, assessed at identical time points by personnel blinded to group assignment.

Protocol: Ensuring Compliance and Minimizing Contamination

Objective: To monitor and enhance adherence to the assigned diet in both the intervention and control groups, while minimizing cross-over (contamination) between groups.

Materials:

- Food diaries and digital food photography apps.

- Biomarker assay kits (e.g., for specific fatty acids, vitamins, or urinary metabolites).

- Standardized questionnaires to assess self-reported compliance and intake of non-study foods.

- Participant incentive structure.

Methodology:

- Compliance Monitoring:

- Self-Report: Collect detailed 3-day or 7-day food records at baseline, mid-intervention, and end-of-study.

- Biomarkers: Collect and analyze biological samples (blood, urine, adipose tissue) for nutrients or metabolites specific to the intervention (e.g., plasma alpha-linolenic acid for a flaxseed intervention, urinary nitrogen for protein).

- Pill Counts: For supplement studies, weigh returned bottles or count returned pills.

- Minimizing Contamination:

- Education: Clearly explain to participants the importance of adhering only to their assigned group.

- Separate Sessions: Hold group sessions for intervention and control participants at different times to prevent informal sharing of information or strategies.

- Statistical Analysis: Plan to conduct both Intention-To-Treat (ITT) and Per-Protocol (PP) analyses. The ITT analysis includes all randomized participants and preserves the value of randomization, providing an estimate of the "real-world" effectiveness. The PP analysis includes only participants who adhered to the protocol, providing an estimate of the efficacy under ideal conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and tools required for the rigorous implementation of control groups and compliance monitoring in dietary intervention trials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dietary RCTs

| Item | Function / Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo Base Materials | Creation of inert comparators for supplements and fortified foods. | Microcrystalline cellulose (capsules), maltodextrin (powders), olive/sunflower oil (liquid supplements). Must be devoid of the active compound and generally recognized as safe (GRAS). |

| Blinded Supplement Kits | Packaging for active and placebo supplements to maintain allocation concealment. | Identical in weight, appearance, and packaging. Should use a randomized, unique alphanumeric code generated by a third-party statistician. |

| Biomarker Assay Kits | Objective verification of dietary compliance and biological effect. | Examples: ELISA kits for specific nutrients, HPLC kits for fatty acid profiles, mass spectrometry for metabolomic profiling. Must be validated for the specific matrix (serum, plasma, urine). |