Dietary Modulation of the Gut-Brain Axis: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Applications, and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive review for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of diet in gut-brain-axis communication.

Dietary Modulation of the Gut-Brain Axis: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Applications, and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of diet in gut-brain-axis communication. It explores the foundational science of the microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA), detailing the neural, endocrine, and immune pathways through which dietary components influence brain function and mental health. The content covers methodological approaches for investigating these interactions, including dietary interventions like probiotics, prebiotics, and specific diets (e.g., Mediterranean, high-fiber). It further addresses current challenges in the field, such as individual microbiome variability and barriers to effective signaling, and evaluates the validation of therapeutic strategies through preclinical models and clinical trials. The synthesis aims to inform the development of novel, microbiota-targeted therapeutics and nutritional psychiatry approaches.

The Gut-Brain Dialogue: Unraveling the Core Pathways and Dietary Influences

Core Concepts and Components of the MGBA

The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis (MGBA) represents a complex, bidirectional communication network that integrates gastrointestinal tract activity with central nervous system (CNS) functions through neural, immune, endocrine, and metabolic pathways [1] [2]. This integrated system facilitates continuous crosstalk between the gut's resident microbiota and the brain, influencing everything from neurodevelopment to neurodegenerative processes [2] [3]. The conceptual framework of the MGBA has evolved beyond simple gut-brain communication to encompass a broader gut-immune-brain paradigm, recognizing the immune system as a critical intermediary [4].

Central to this axis is the gut microbiota—a diverse ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, archaea, and fungi that reside primarily in the colon [2]. The collective genome of these intestinal microorganisms contains over three million genes, far surpassing the approximately 23,000 protein-coding genes in the human genome, enabling production of metabolites vital for host functions including immune regulation and gut-brain signaling [1]. The gut microbiome can therefore be considered a functional "second genome" that significantly influences host physiology and brain health [5].

The major components of the MGBA include: (1) the gut microbiota; (2) the intestinal barrier and mucosal immune system; (3) circulating immune cells and cytokines; (4) the enteric nervous system (ENS) and vagus nerve; (5) central autonomic circuits and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress pathways; and (6) CNS interfaces including the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and microglia [2]. Disruption of any single component can reverberate throughout this interconnected system, potentially contributing to neurological and psychiatric disorders [2] [4].

Table 1: Major Components of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

| Component | Description | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Gut Microbiota | Diverse community of microorganisms in gastrointestinal tract | Produces metabolites (SCFAs, neurotransmitters), regulates immunity, maintains barrier integrity |

| Enteric Nervous System (ENS) | Extensive network of ~500 million neurons in gut wall | Regulates gut motility, secretion, blood flow; communicates with CNS via vagus nerve |

| Vagus Nerve | Primary neural pathway connecting gut and brain | Bidirectional communication; transmits sensory signals from gut to brainstem and efferent commands back to gut |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis | Neuroendocrine stress response system | Releases cortisol in response to stress; modulates gut permeability and immune function |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) | Semi-permeable interface between blood and CNS | Regulates passage of substances; affected by gut-derived metabolites and inflammatory mediators |

| Immune System | Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and systemic immunity | Produces cytokines and inflammatory mediators; shaped by microbial signals |

Key Communication Pathways

The MGBA utilizes multiple interdependent signaling routes to maintain bidirectional communication between gut and brain. These pathways can be categorized into four primary mechanisms: neural, immune, endocrine, and metabolic.

Neural Pathways

The vagus nerve serves as a direct neural highway between the gut and brainstem, with afferent fibers transmitting sensory information from intestinal receptors to the brain and efferent fibers carrying commands back to influence gut activity [2]. This pathway enables rapid communication, allowing gut microbes to influence brain function in real-time through production of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators including GABA, serotonin, and histamine that can activate vagal afferent endings [2]. The critical role of vagal signaling is highlighted by observations that individuals who underwent vagotomy have a lower subsequent risk of developing Parkinson's disease, supporting the hypothesis that α-synuclein pathology may originate in the gut and spread to the brain via this neural route [2].

Immune and Inflammatory Pathways

The gut microbiota profoundly shapes host immunity from development through adulthood [4]. Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria, can breach a compromised intestinal barrier and enter circulation, where they activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in peripheral tissues and the brain [2]. Even low-grade endotoxin leakage can trigger chronic neuroinflammation through microglial activation via TLR4/NF-κB signaling [2]. Additionally, gut-resident T cells conditioned by microbiota can traffic to the CNS, with specific bacteria driving expansion of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells or anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs) that significantly impact neuroinflammation [2].

Endocrine Pathways

The HPA axis represents a key neuroendocrine component of the MGBA, translating stress signals into systemic hormone release that alters gut barrier integrity and immune function [2]. Stress-induced activation of this axis leads to cortisol release that can suppress immune function and shift microbial composition toward a more pro-inflammatory state [1]. Additionally, gut microbes influence the production of various gut hormones including peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) that integrate metabolic and cognitive functions [6].

Metabolic Pathways

Gut microbes produce numerous metabolites through fermentation of dietary components that significantly impact brain function [1]. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including butyrate, propionate, and acetate are produced from dietary fiber fermentation and function as epigenetic regulators through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition [6]. These metabolites can cross the BBB, influence microglial function, and promote neurotrophic factor expression [1]. Additionally, microbial transformation of primary bile acids into secondary bile acids activates nuclear receptors that modulate metabolic and inflammatory pathways systemically [6].

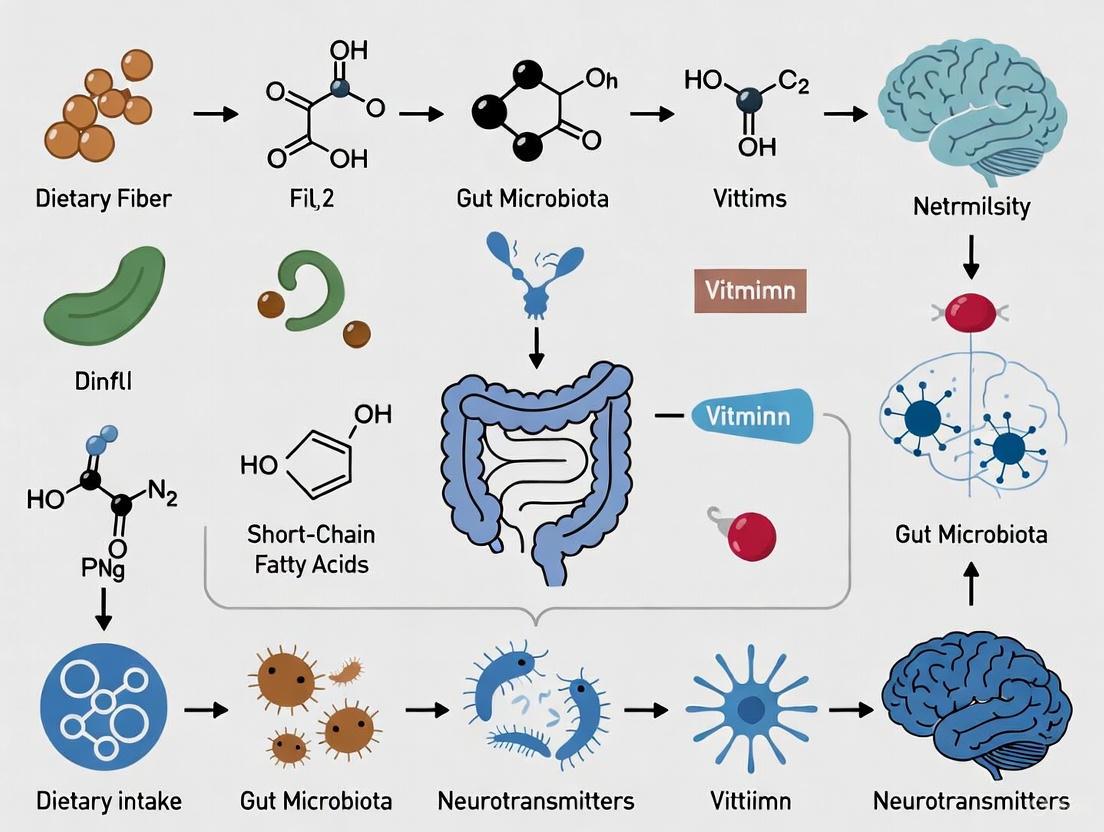

MGBA Communication Pathways Diagram

Microbial Metabolites and Signaling Molecules

The gut microbiota produces a diverse array of metabolites that serve as key signaling molecules along the MGBA. These microbial byproducts represent crucial mechanisms through which gut microbes influence brain function and behavior.

Table 2: Key Microbial Metabolites in MGBA Signaling

| Metabolite Class | Major Representatives | Production Process | Effects on Brain Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Butyrate, Acetate, Propionate | Fermentation of dietary fiber by gut bacteria | Cross BBB, restore microglial density and morphology, promote GDNF expression in astrocytes, support cognitive function [1] |

| Neurotransmitters | GABA, Serotonin, Dopamine, Glutamate | Synthesis by specific gut bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) | Modulate neuronal activity; gut-derived serotonin (90% of body's total) influences mood, sleep, behavior; GABA affects vagus nerve and ENS activity [1] [7] |

| Bile Acids | Primary: cholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid; Secondary: deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid | Liver produces primary bile acids; gut bacteria transform to secondary bile acids | Activate nuclear receptors (FXR, TGR5) to modulate metabolic and inflammatory pathways systemically [1] [6] |

| Tryptophan Derivatives | Kynurenine, Indole derivatives | Microbial metabolism of dietary tryptophan | Regulate neuroinflammation; influence microglia immune cells and astrocyte activity in the brain [2] |

| Branch-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs) | Leucine, Isoleucine, Valine | Microbial metabolism | Serve as precursors for neurotransmitters; influence CNS function [1] |

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are particularly crucial metabolites produced when undigested dietary fibers reach the colon and are fermented by specific gut bacteria [1]. These compounds include propionic acid (C3), butyric acid (C4), valeric acid (C5), acetic acid (C2), and formic acid (C1) [1]. Under stable conditions, monocarboxylate transporters facilitate the passage of SCFAs across the BBB, where they are detected in human cerebrospinal fluid [1]. Butyrate, specifically, promotes glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) expression in astrocytes, which are essential for regulating neuronal growth, survival, and synaptic differentiation [1].

The production of neurotransmitters by gut microbiota represents another significant pathway. Notably, approximately 90% of serotonin is generated in the gut under microbial influence, interfering with mood, sleep, and other brain functions [1] [7]. GABA, the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, is produced by human microbiota communities including Lactobacillus brevis and Bifidobacterium dentium [1]. While GABA produced in the gut cannot cross the BBB directly, it can indirectly affect brain activity by influencing vagus nerve or enteric nervous system activity [1].

Experimental Methodologies in MGBA Research

Research investigating the microbiota-gut-brain axis employs diverse methodologies ranging from preclinical animal models to human clinical trials and advanced omics technologies. Understanding these experimental approaches is essential for evaluating evidence in this rapidly evolving field.

Animal Models

Germ-free (GF) mouse models have been fundamental in establishing the importance of gut microbiota for normal brain development and function [4]. These studies revealed that the absence of gut microbiota leads to alterations in stress responses, neurotransmitter levels, and neurodevelopment [4]. Colonization of GF mice with specific microbiota restores normal levels of stress hormones and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), highlighting microbial influence on neuronal function [4]. Importantly, recolonization later in life fails to fully restore typical brain function, indicating critical windows for microbiota-brain interactions during early development [3].

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) studies in animals provide evidence for causal relationships between gut microbiota and behavior. For instance, transplantation of intestinal flora from patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) into germ-free mice induced ASD-like behaviors in recipient animals [5]. Similarly, transplants of feces from anxiety-like mice promoted anxiety-like behavior in sterile mice and vice versa [5].

Human Studies

Human research encompasses observational studies that compare gut microbiota composition between healthy individuals and those with neurological or psychiatric conditions, intervention studies investigating probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary modifications, and correlational studies examining relationships between microbial metabolites, imaging findings, and behavioral measures [8].

Large-scale epidemiological analyses, such as those leveraging the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, have established associations between dietary patterns, gut microbiota profiles, and disease risk [6]. Additionally, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrate that specific probiotic formulations can mitigate stress and inflammation in humans via gut microbiota modulation [6].

Analytical Techniques

Advanced omics technologies have revolutionized MGBA research. 16S ribosomal RNA and whole genome sequencing techniques enable characterization of gut microbiota diversity [5]. Metagenomics, metabolomics, and other omics analysis techniques combined with microbiome-wide association studies facilitate identification of intestinal flora types associated with disease and elucidate molecular mechanisms of specific interactions [5].

Integration of multi-omics data including metagenomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics is increasingly essential to elucidate mechanistic links between diet, microbial metabolites, and host physiological outcomes [6]. These approaches are being enhanced by artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze complex datasets and predict individual responses to dietary interventions [6].

MGBA Research Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

MGBA research requires specialized reagents and tools to investigate the complex interactions between diet, gut microbiota, and brain function. The following table details essential research materials and their applications in experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MGBA Investigations

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic Strains | Lactobacillus brevis, Bifidobacterium dentium, Bifidobacterium adolescentis CCFM1447, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis CCFM1426 | Intervention studies; mechanistic investigations | Produce neurotransmitters (GABA); modulate immune responses; enrich beneficial bacteria; mitigate osteoporosis; enhance anti-colitic effects [1] [6] |

| Prebiotics & Dietary Fibers | Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), granola with multiple prebiotics, high-fiber diets | Dietary intervention studies; microbial metabolism research | Serve as substrates for SCFA production; increase Bifidobacterium abundance; improve stress/sleepiness; shape microbial community structure [1] [6] |

| Germ-Free Animal Models | Germ-free (axenic) mice, Gnotobiotic animals | Causal mechanism studies; microbiota transfer experiments | Enable study of microbiota absence on neurodevelopment; permit colonization with specific microbial communities; establish causal relationships [5] [4] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | 16S rRNA sequencing kits, Metagenomic sequencing reagents, Metabolomics platforms | Microbiome composition analysis; functional characterization | Enable taxonomic profiling; facilitate whole genome sequencing; identify microbial metabolic pathways; quantify microbial metabolites [5] [8] |

| Immunoassay Kits | Cytokine panels (TNF-α, IL-10), LPS detection assays, Cortisol/ Corticosterone ELISA | Inflammatory pathway analysis; HPA axis assessment | Quantify inflammatory mediators; measure endotoxin translocation; assess stress hormone levels; evaluate gut barrier integrity [1] [2] |

| Vegfr-2-IN-13 | Vegfr-2-IN-13, MF:C24H18N6O2S, MW:454.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Rifasutenizol | Rifasutenizol, CAS:1001314-13-1, MF:C48H61N7O13, MW:944.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Dietary Modulation of the MGBA

Diet represents the most significant modifiable factor influencing the gut microbiota and consequently the MGBA. Nutritional neuroscience has emerged as a promising approach for managing gut-brain axis communication and mental health disorders through various pathways [9].

Dietary Patterns and Microbial Composition

Different dietary patterns exert distinct effects on gut microbial communities. High-fiber, plant-based diets including the Mediterranean diet enhance microbial diversity, decrease inflammation, and improve gut-brain communication [7]. These diets act as prebiotics that nourish beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which produce SCFAs essential for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and regulating immune responses [7].

Conversely, Western dietary patterns high in refined sugars, animal fats, and low in fiber are associated with dysbiosis—a microbial imbalance marked by decreased diversity and increased populations of pathogenic bacteria like Bacteroides and Alistipes that promote systemic inflammation and increase gut permeability [7]. Such diets reduce beneficial bacterial populations, diminishing SCFA production and potentially exacerbating symptoms of mood disorders [7].

Specific Dietary Components

Polyphenols, found in plant-based foods like berries, tea, and olive oil, possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that benefit the gut microbiota by supporting growth of beneficial bacteria while inhibiting harmful species [7]. Similarly, plant-based proteins in legumes and nuts encourage growth of health-promoting microbes, whereas high intake of animal protein is associated with bile-tolerant bacteria such as Bilophila that are linked to inflammation and increased gut permeability [7].

Soluble fibers, abundant in foods like oats, apples, and citrus fruits, serve as food sources for gut bacteria while also reducing harmful bacterial adhesion to the gut lining, thus supporting the gut barrier and enhancing immune function [7]. In contrast, diets high in processed foods can lead to production of harmful metabolites like trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), which is associated with cardiovascular disease risks [7].

Timing of Dietary Interventions

Emerging evidence suggests the existence of sensitive periods when microbiome-targeted interventions may exert maximal and long-lasting effects on neurodevelopment [3]. The prenatal period is particularly critical, with maternal microbial metabolites such as SCFAs crossing the placenta and influencing fetal immune and brain development [3]. During infancy (0-3 years), a highly dynamic microbiota coincides with rapid synaptogenesis, myelination, and immune system maturation [3]. Studies in germ-free animals indicate that outside this early-life window, successful restoration of normal brain function cannot be fully achieved [3].

Implications for Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Dysregulation of the MGBA has been implicated in a wide spectrum of neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions, offering new perspectives on disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic approaches.

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Pediatric neurodevelopmental disorders including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Rett syndrome (RTT), and Tourette syndrome (TS) are associated with alterations in the MGBA [3]. Children with ASD often exhibit distinct gut microbiota profiles characterized by increased abundances of genera such as Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Sutterella, and Lactobacillus, alongside decreased levels of Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Blautia, and Prevotella [1]. Fecal microbiota transplantation from ASD patients to germ-free mice is sufficient to induce ASD-like behaviors in recipient animals, suggesting a causal role for gut microbes in these neurodevelopmental conditions [5].

Neurodegenerative Diseases

The MGBA plays significant roles in the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS) [2]. Associations between specific gut microbiota and neurodegenerative processes focus on the role of certain bacteria in amyloid aggregation and neuroinflammation [1]. In PD, misfolded α-synuclein protein aggregates may originate in the gut and spread to the brain via vagal nerve fibers [2]. Additionally, distinct gut microbiota profiles are observed in AD patients compared to healthy peers, with chronic constipation often preceding PD motor symptoms by up to 20 years [2].

Psychiatric Conditions

The gut microbiota significantly influences depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric conditions through multiple pathways [1] [8]. Probiotic supplementation has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression in both animal models and clinical trials [5]. The mechanisms underlying these effects involve microbial production of neurotransmitters, regulation of the HPA axis, modulation of systemic inflammation, and influence on neuroplasticity [8]. Psychobiotics—specific probiotics and prebiotics with mental health benefits—demonstrate potential in easing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress-related disorders by balancing gut microbiota, decreasing neuroinflammation, and modulating neurotransmitter activity [7].

The microbiota-gut-brain axis represents a transformative paradigm in neuroscience, microbiology, and nutrition research. This bidirectional communication network integrates signals from the gut microbiota, immune system, and brain through neural, endocrine, immune, and metabolic pathways, significantly influencing neurodevelopment, neurodegenerative processes, and psychiatric conditions [1] [2] [4].

Future research will likely focus on precision nutrition strategies that account for individual variability in microbiome composition, host genetics, and environmental factors [6]. Development of targeted interventions using specific dietary components—such as prebiotics, polyphenols, and fermented foods—aims to selectively modulate microbial taxa and metabolic pathways that influence extra-intestinal organs including the brain [6]. Advanced multi-omics integration will be essential to elucidate mechanistic links between diet, microbial metabolites, and host physiological outcomes [6].

Significant challenges remain in establishing causal relationships, accounting for inter-individual variability, and ensuring reproducibility in therapeutic outcomes [2]. Longitudinal human cohorts, mechanistic models, and large-scale clinical trials are needed to clarify the role of the MGBA in health and disease [2] [3]. Additionally, ethical and safety considerations must be addressed in implementing early-life microbiome-based interventions, particularly within pediatric populations [3].

Despite these challenges, understanding the MGBA provides unprecedented opportunities for developing innovative, personalized therapies tailored to individual microbiomes and immune profiles. As research continues to unravel the complexities of this intricate communication network, targeting the MGBA may ultimately redefine clinical approaches to neurological, neurodevelopmental, and psychiatric disorders.

The gut-brain axis represents one of the most dynamic frontiers in physiological research, constituting a complex, multidirectional communication network that integrates gastrointestinal function with cognitive and emotional centers in the brain. While historically conceptualized as primarily neural in nature, contemporary research has revealed that this axis operates through three principal signaling pathways: neural (vagus nerve), endocrine (HPA axis), and immune signaling. These pathways do not operate in isolation but rather form an integrated communication network that enables the gut to influence brain function and vice versa. Within the context of diet-gut-brain research, understanding these pathways is paramount, as nutritional interventions represent the most accessible modality for modulating this axis for therapeutic benefit. This whitepaper delineates the core mechanisms governing these communication pathways, provides experimental methodologies for their investigation, and contextualizes their function within the framework of dietary influence on gut-brain communication.

Core Communication Pathways of the Gut-Brain Axis

Neural Signaling: The Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X) serves as the primary neural conduit for rapid communication between the gut and the brain. Accounting for approximately 80-90% of all afferent fibers in the autonomic nervous system, it functions as a critical information superhighway [10] [11].

Anatomical and Functional Basis: Vagal afferent fibers possess endings in the intestinal lamina propria that are in close proximity to the gut epithelium, enabling them to sample a wide array of signals from the gut lumen, including mechanical stretch, nutrients, and microbial metabolites [11]. This sensory information is relayed to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem, which then projects to higher brain centers such as the hypothalamus and amygdala, influencing autonomic regulation, mood, and behavior [12].

The Inflammatory Reflex: A critical function of the vagus nerve is its role in the inflammatory reflex, a hardwired circuit that detects peripheral inflammation and relays this information to the brain, which in turn activates vagal efferent pathways to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the periphery [13] [11]. This cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway primarily acts through the release of acetylcholine, which binds to α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7 nAChR) on macrophages and other immune cells, inhibiting the release of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [13].

Dietary Interactions: Dietary components directly influence vagal tone. For instance, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, produced by microbial fermentation of dietary fiber, can directly activate vagal afferents [4] [14]. Furthermore, gut microbes stimulated by a healthy diet can produce neurotransmitters (e.g., GABA) that are sensed by the vagus nerve [15].

Endocrine Signaling: The HPA Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the body's central stress response system and a major endocrine pathway in gut-brain communication. Its activation culminates in the production of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans), which exert widespread effects on metabolism, immunity, and brain function [16] [11].

Pathway Mechanism: In response to physical or psychological stressors, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn prompts the adrenal cortex to release glucocorticoids into the systemic circulation [16].

Gut Microbiota and HPA Development: The gut microbiota is essential for the normal developmental programming of the HPA axis. Studies in germ-free (GF) mice demonstrate an exaggerated HPA stress response, which can be normalized by reconstitution with specific microbiota early in life [4]. This highlights a critical window in early life where microbial colonization shapes long-term neuroendocrine resilience.

Dietary and Microbial Modulation: The gut microbiota can modulate HPA axis activity through multiple mechanisms. Microbial metabolites like SCFAs can regulate the activity of enteroendocrine cells, which release gut hormones (e.g., GLP-1, PYY) that indirectly influence the HPA axis [11]. Additionally, gut bacteria can metabolize dietary tryptophan into various indole derivatives and neuroactive substances that can influence systemic levels of serotonin, a key regulator of mood and stress [15] [11]. Dysbiosis, often driven by a Western-style diet, can lead to HPA axis dysregulation and increased susceptibility to stress-related disorders [14].

Immune Signaling

The immune system acts as a fundamental interface translating signals from the gut lumen, including those derived from the microbiota and diet, into systemic and neural messages that can impact brain function [4] [11].

Gut Mucosa as an Immune Interface: The gastrointestinal tract houses the largest collection of immune cells in the body, collectively known as the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the development and regulation of both innate and adaptive immunity [4]. For instance, segmented filamentous bacteria drive the differentiation of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells, while other commensals like Clostridium species promote the expansion of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs) [4].

Key Signaling Molecules:

- Microbial Metabolites: SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) are potent immunomodulators. They inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs) and activate G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) such as GPR43 and GPR109a on immune cells, leading to the suppression of NF-κB and the promotion of Treg differentiation, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects [4] [15].

- Microbial-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs): Bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), peptidoglycan, and flagellin are recognized by pattern-recognition receptors (e.g., Toll-like receptors, TLRs) on host immune cells. This interaction is crucial for maintaining immune homeostasis but can trigger neuroinflammation if the intestinal barrier is compromised ("leaky gut"), allowing excessive MAMP translocation into circulation [4] [12].

Communication to the Brain: Peripheral immune activation leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α). These cytokines can signal the brain directly by crossing the blood-brain barrier via active transport, indirectly via vagal afferents, or by interacting with the brain's vasculature to induce local neuroinflammation, influencing synaptic plasticity and contributing to the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases [4] [15].

Table 1: Key Immune-Modulating Microbial Metabolites and Their Mechanisms

| Metabolite | Primary Microbial Producers | Immunological Mechanism | Impact on Brain Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp., Lachnospiraceae family [14] [12] | HDAC inhibition; activation of GPCRs (GPR41, GPR43) [4] | Promote microglial homeostasis; strengthen BBB; reduce neuroinflammation [15] |

| Tryptophan Derivatives | Various species metabolizing dietary tryptophan [11] | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) activation; regulation of T cell differentiation [4] | Influences production of serotonin and kynurenine pathways; regulates mood and behavior [11] |

| Secondary Bile Acids | Bacteria with bile salt hydrolase activity [15] | Modulation of Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) and TGR5 signaling [15] | Can compromise gut barrier; systemic influx may trigger neuroinflammatory responses [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Gut-Brain Communication

To elucidate the mechanisms of the gut-brain axis, researchers employ a combination of animal models, biochemical assays, and neural manipulation techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments.

Assessing Vagus Nerve Dependency

Objective: To determine if a specific dietary or microbial intervention (e.g., a probiotic or SCFA) exerts its effects on the brain via the vagus nerve.

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Utilize adult C57BL/6 mice or Sprague-Dawley rats.

- Surgical Intervention:

- Experimental Group: Perform subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, surgically severing the vagal trunks below the diaphragm.

- Control Group: Undergo a sham surgery, involving identical procedures except for the nerve transection.

- Treatment: Administer the intervention (e.g., oral gavage of a bacterial strain or intraperitoneal injection of a metabolite) post-recovery.

- Outcome Measures:

- Behavioral Tests: Assess anxiety-like behavior (elevated plus maze, open field test) and memory (fear conditioning, Morris water maze).

- Molecular Analysis: Quantify neuroinflammatory markers (IL-1β, TNF-α) and activation of microglia (Iba1 staining) in brain regions such as the hippocampus and hypothalamus.

- Interpretation: If the behavioral or neuroinflammatory benefits of the intervention are abolished in the vagotomy group but preserved in the sham group, the effect is considered vagus nerve-dependent [10] [11].

Evaluating HPA Axis Function

Objective: To measure the impact of gut microbiota manipulation on the neuroendocrine stress response.

Methodology:

- Models of Manipulation:

- Germ-Free (GF) Models: Compare HPA function in GF mice versus conventionally colonized controls.

- Probiotic/FMT Models: Administer a probiotic consortium or perform fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from donor mice and test HPA response.

- Dietary Models: Feed animals a defined diet (e.g., high-fat, high-fiber) and monitor subsequent HPA activity.

- Stress Challenge: Subject animals to an acute stressor, such as restraint stress for 15-30 minutes or a forced swim test.

- Sample Collection: Collect blood plasma via tail nick or cardiac puncture at baseline and at multiple time points post-stress (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 90 minutes).

- Biochemical Analysis: Measure circulating corticosterone (in rodents) or cortisol (in humans) levels using a standardized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit.

- Interpretation: An exaggerated or prolonged corticosterone response in GF or dysbiotic animals indicates impaired HPA axis regulation, which can be corrected by microbial or dietary intervention [4] [16].

Profiling the Peripheral Immune Response

Objective: To characterize how dietary interventions alter systemic and mucosal immunity in relation to brain health.

Methodology:

- Intervention: Feed mice a control diet vs. an experimental diet (e.g., Mediterranean-style diet vs. Western-style diet) for 8-12 weeks.

- Sample Collection: At endpoint, collect blood (serum/plasma), mesenteric lymph nodes, and intestinal lamina propria.

- Immune Cell Isolation: Isolate immune cells from lamina propria and spleen using collagenase digestion and density gradient centrifugation.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Stain cells with fluorescently labeled antibodies against key surface markers.

- Key Cell Populations: Analyze frequencies of T helper (Th)1, Th17, and Regulatory T (Treg) cells (e.g., CD4+FoxP3+ for Tregs).

- Activation Status: Measure expression of activation markers like CD44 and CD69.

- Cytokine Measurement: Quantify levels of pro-inflammatory (IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines in serum and cell culture supernatants using a multiplex cytokine array.

- Correlation with Neural Outcomes: Statistically correlate immune parameters with behavioral data and brain immunohistochemistry to establish functional links [4] [11].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core communication pathways and an integrated experimental workflow.

Neural and Immune Signaling Pathway

Diagram 1: Gut-Brain Neural and Immune Signaling

Integrated Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Integrated Gut-Brain Axis Research Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Models for Gut-Brain Axis Research

| Category | Reagent / Model | Specific Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Germ-Free (GF) Mice | C57BL/6 GF mice [4] | Establish causal role of microbiota by comparing physiology and behavior in absence vs. presence of microbes. |

| Gnotobiotic Models | Mice mono-colonized with specific bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium) [4] | Determine the specific function of a single microbial species in the host. | |

| Molecular Tools | ELISA Kits | Corticosterone/Cortisol ELISA, Multiplex Cytokine Panels [16] | Precisely quantify hormone and cytokine levels in plasma, serum, and tissue homogenates. |

| Antibodies for Flow Cytometry | Anti-CD4, Anti-FoxP3 (for Tregs), Anti-CD11b, Anti-Iba1 (for microglia) [4] [11] | Identify, characterize, and sort specific immune cell populations from tissues. | |

| Dietary Components | Defined Diets | High-Fiber Diet, High-Fat Diet (Western Diet) [14] | Systematically investigate the impact of specific macronutrients on the gut-brain axis. |

| Prebiotics | Fructooligosaccharides (FOS), Galactooligosaccharides (GOS) [14] | Selectively stimulate the growth of beneficial gut bacteria to study their downstream effects. | |

| Surgical & Neural Tools | Subdiaphragmatic Vagotomy | Surgical transection of vagal trunks [10] [11] | Critically test the necessity of the vagus nerve in mediating a gut-to-brain signal. |

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) | Implantable or non-invasive VNS devices [13] [10] | Therapeutically modulate vagal activity to study impact on inflammation and behavior. | |

| Moclobemide-d4 | Moclobemide-d4, MF:C13H17ClN2O2, MW:272.76 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cox-2-IN-23 | Cox-2-IN-23, MF:C24H25N5O3S2, MW:495.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The intricate communication along the gut-brain axis through neural, endocrine, and immune pathways represents a fundamental biological system with profound implications for human health and disease. The vagus nerve provides a rapid, hardwired communication line, the HPA axis integrates stress and metabolic signals, and the immune system acts as a pervasive translator of microbial and dietary cues. These pathways are not merely parallel but are deeply intertwined, creating a robust and adaptive communication network. For researchers and drug development professionals, targeting these pathways—particularly through dietary interventions that modify the gut microbiota—offers a promising, multi-pronged strategy for addressing conditions ranging from neuropsychiatric disorders to neurodegenerative diseases. The future of this field lies in further dissecting the molecular mechanisms of these interactions and leveraging this knowledge to develop precise, microbiota-targeted therapeutics that can effectively modulate this critical axis for improved brain health.

The microbiota-gut-brain axis represents one of the most dynamic frontiers in neurobiology, serving as a critical communication network between gastrointestinal tract microbiota and the central nervous system. This review systematically examines the fundamental roles of microbial-derived metabolites as essential messengers within this axis, focusing on three principal classes: short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), neurotransmitters, and tryptophan derivatives. We synthesize current understanding of their production, transport mechanisms, and molecular pathways through which they influence neuroimmunoendocrine regulation. Within the context of diet-gut-brain research, we highlight how nutritional interventions shape microbial metabolite production and subsequently impact brain health and disease pathogenesis. The comprehensive analysis presented herein provides a foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting microbial metabolite pathways for neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts an extraordinarily complex ecosystem of microorganisms collectively known as the gut microbiota, comprising trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea [17] [15]. This microbial community possesses a genetic potential approximately 150 times greater than the human genome, enabling extensive metabolic capabilities that significantly influence host physiology [15]. The concept of the microbiota-gut-brain axis has emerged as a fundamental framework for understanding the bidirectional communication between these gut microorganisms and the central nervous system (CNS) [17] [15] [18]. This multidirectional signaling network incorporates neuronal, endocrine, metabolic, and immune pathways that continuously mediate cross-talk between the gut and brain [15].

The gut microbiota influences CNS processes through multiple interconnected mechanisms: direct neural signaling via the vagus nerve [17]; modulation of the immune system and neuroinflammation [15] [18]; regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [17]; and through the production of myriad neuroactive metabolites [17] [19]. These microbial-derived metabolites, including SCFAs, neurotransmitters, and tryptophan derivatives, have emerged as crucial mediators of gut-brain communication, potentially influencing the development and progression of various neurodegenerative, neuropsychiatric, and neurodevelopmental disorders [17] [19] [15].

Diet represents a primary modulator of the gut-brain axis, serving as both a source of precursors for microbial metabolism and a determinant of microbiota composition [20]. Nutritional components shape the functional capacity of the gut microbiome, influencing the production of key metabolites that subsequently affect brain physiology [20] [21]. This review will explore the specific roles of SCFAs, neurotransmitters, and tryptophan derivatives within this complex network, emphasizing their mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic applications.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Microbial Fermentation Products with Systemic Effects

Production, Absorption, and Distribution

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), are the main metabolites produced in the colon through bacterial fermentation of indigestible dietary fibers and resistant starch [17] [18]. The human gut produces approximately 500-600 mmol of SCFAs daily, with a typical molar ratio of 60:20:20 for acetate, propionate, and butyrate, respectively, though this ratio can vary significantly based on dietary composition [17] [18]. Following their production, SCFAs are absorbed by colonocytes via H+-dependent monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) and sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporters (SMCTs) [17]. While a substantial portion is metabolized locally by gut epithelial cells and hepatocytes, the remainder enters systemic circulation, with concentrations reflecting their production and metabolism rates [18].

Table 1: Primary SCFA-Producing Bacteria and Their Metabolic Pathways

| SCFA | Key Producing Bacteria | Major Metabolic Pathways | Relative Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides spp. | Glycolysis, Wood-Ljungdahl pathway | ~60% (Highest in circulation) |

| Propionate | Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides spp. | Succinate, acrylate, propanediol pathways | ~20% |

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Eubacterium rectale, Eubacterium hallii | Butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase, phosphate butyryltransferase, butyrate kinase | ~20% (Lowest in circulation) |

SCFAs readily cross the blood-brain barrier, with measured concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid ranging from 0-171 mM for acetate, 0-6 mM for propionate, and 0-2.8 mM for butyrate [18]. Their presence in the central nervous system enables direct effects on brain cells, particularly microglia, the resident immune cells of the CNS [18].

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

SCFAs exert their physiological effects through two primary molecular mechanisms: activation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) [18]. The most extensively studied SCFA receptors are free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2/GPR43) and free fatty acid receptor 3 (FFAR3/GPR41), which are expressed in various tissues including colonic epithelium, immune cells, and the peripheral nervous system [18]. Butyrate's potent inhibition of HDACs leads to epigenetic modifications that alter gene expression patterns in both peripheral tissues and CNS cells [17] [18].

The "SCFAs-microglia pathway" has recently been identified as a crucial communication link within the gut-brain network [18]. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, are essential for maintaining microglial homeostasis and function, influencing their maturation, immune activity, and phagocytic capacity [18]. During dysbiosis or SCFA deficiency, microglia develop dysfunctional characteristics, impairing their ability to perform essential CNS maintenance functions [18].

Experimental Approaches for SCFA Research

Table 2: Key Methodologies for SCFA Analysis in Gut-Brain Axis Research

| Methodology | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Quantification of SCFA concentrations in feces, blood, CSF, and brain tissue | Requires derivatization for volatility; high sensitivity and specificity [18] |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | SCFA quantification in biological samples | No derivatization needed; can detect multiple SCFAs simultaneously [18] |

| Germ-free (GF) animal models | Studying SCFA deficiency effects on microglia and brain function | Complete absence of microbiota; requires strict sterile conditions [18] |

| Gnotobiotic models | Investigating specific bacterial functions | Animals colonized with defined microbial communities [15] |

| SCFA supplementation studies | Therapeutic potential assessment | Direct administration of SCFAs or precursors; dose-dependent effects [17] |

| Receptor knockout models | Elucidating FFAR2/FFAR3 mechanisms | Tissue-specific knockouts reveal localized functions [18] |

Microbial Modulation of Neurotransmitters

Direct and Indirect Regulation of Neurotransmitter Pathways

The gut microbiota significantly influences neurotransmitter systems through both direct production of neuroactive molecules and indirect regulation of host synthesis pathways [19]. Numerous bacterial species can independently synthesize or modulate the synthesis of key neurotransmitters, including γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, and noradrenaline [17] [19]. Additionally, gut bacteria can signal enteroendocrine cells to regulate the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters, acting locally on the enteric nervous system or transmitting rapid signals to the brain via the vagus nerve [19].

Table 3: Microbial Regulation of Neurotransmitter Systems

| Neuro-transmitter | Key Microbial Genera | Synthesis Mechanism | Primary Functions in Gut-Brain Axis |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABA | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides fragilis, Parabacteroides, Eubacterium | Direct synthesis from glutamate via gad gene | Modulates synaptic transmission in ENS; regulates feelings of fear and anxiety [19] [21] |

| Serotonin | Clostridial species, Staphylococcus | Induction of synthesis by enterochromaffin cells; precursor availability | Promotes intestinal motility; >90% of body's serotonin located in GI tract [19] [22] |

| Dopamine | Staphylococcus | Direct synthesis; precursor conversion | Affects gastric secretion, motility, and mucosal blood flow [19] |

| Acetylcholine | Lactobacillus plantarum, Bacillus subtilis | Direct synthesis via choline metabolism | Regulates intestinal motility, secretion, and enteric neurotransmission [19] |

| Glutamate | Lactobacillus plantarum, Bacteroides vulgatus | Direct synthesis; stimulation of enteroendocrine cells | Transfer intestinal sensory signals to brain via vagus nerve [19] |

Serotonin: A Prime Example of Gut-Brain Communication

The serotonergic system exemplifies the complex interplay between gut microbiota and neurotransmitter pathways. Over 90% of the body's serotonin is synthesized in the gastrointestinal tract, primarily by enterochromaffin cells (ECs) [22]. The gut microbiota regulates peripheral serotonin production through multiple mechanisms: direct modulation of ECs activity; provision of serotonin precursors; and metabolism of serotonin itself [19] [22]. Importantly, peripheral serotonin cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, highlighting the existence of distinct central and peripheral pools that are differentially regulated yet communicate through neural pathways [22].

Tryptophan serves as the exclusive precursor for serotonin synthesis, with its metabolism representing a critical juncture at which the gut microbiota exerts profound influence [22]. The availability of tryptophan for serotonin synthesis depends on competing metabolic pathways, particularly the kynurenine pathway, which is similarly subject to microbial regulation [22]. This metabolic competition establishes a delicate balance that significantly impacts both gastrointestinal and central nervous system function.

Tryptophan Metabolism: A Microbial-Driven Pathway

Host and Microbial Metabolic Pathways

Tryptophan, an essential amino acid obtained exclusively from dietary sources, serves as a crucial substrate for multiple metabolic pathways that collectively influence gut-brain communication [22] [23]. The host metabolizes tryptophan through three major pathways: the serotonin pathway (1-2% of tryptophan), the kynurenine pathway (>90%), and direct microbial metabolism (remaining tryptophan that reaches the large intestine) [22]. The complex interplay between these pathways determines the physiological consequences of tryptophan metabolism on brain function and behavior.

The kynurenine pathway represents the major route of tryptophan catabolism in the host, producing metabolites with diverse neurological effects [22]. This pathway is initiated by the rate-limiting enzymes indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), which are expressed in various tissues including the brain, gastrointestinal tract, and liver [22]. Kynurenine is subsequently metabolized through two distinct branches: the kynurenic acid (KYNA) pathway, which produces neuroprotective NMDA receptor antagonists, and the quinolinic acid (QUIN) pathway, which generates neurotoxic NMDA receptor agonists [22]. The balance between these neuroprotective and neurotoxic metabolites is crucial for maintaining CNS homeostasis.

Microbial Metabolites of Tryptophan

Gut microorganisms metabolize tryptophan into various bioactive compounds including indole, tryptamine, and indole derivatives such as indole-3-aldehyde (IAld), indole-3-acetic-acid (IAA), and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) [22]. These microbial metabolites serve as important signaling molecules that influence host physiology through multiple mechanisms: activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathways; modulation of intestinal barrier function; and regulation of immune responses [22] [23].

Specific bacterial taxa demonstrate specialized capacity for tryptophan metabolism. For instance, Clostridium sporogenes and Ruminococcus gnavus convert tryptophan to tryptamine via tryptophan decarboxylases (TrpDs) [22]. Escherichia coli, Clostridium, and Bacteroides species produce indole through tryptophanase (TnaA) activity [22]. Additionally, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species transform tryptophan into indole-3-lactic acid (ILA), which can be further converted to IPA by bacteria including Clostridium and Peptostreptococcus [22]. These microbial metabolites collectively influence gut-brain communication and potentially impact the development of neuropsychiatric conditions.

Methodological Approaches for Tryptophan Research

Investigation of tryptophan metabolism within the gut-brain axis requires integrated methodological approaches that capture the complexity of host-microbe interactions. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with fluorescence or mass spectrometry detection enables simultaneous quantification of tryptophan and its metabolites in biological samples [22]. Targeted metabolomic approaches provide sensitive measurement of pathway-specific metabolites, while untargeted metabolomics offers discovery-based characterization of novel microbial derivatives [22].

Germ-free animal models demonstrate the essential role of gut microbiota in tryptophan metabolism, showing significantly reduced tryptamine levels and altered kynurenine pathway activity compared to conventionally colonized counterparts [22]. Microbial transplantation studies using defined bacterial communities further elucidate the specific contributions of individual bacterial species to tryptophan metabolic pathways [23]. Additionally, isotopic tracer techniques using stable isotope-labeled tryptophan enable precise tracking of metabolic flux through competing pathways in response to dietary interventions or microbial modulation [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Gut-Brain Axis Investigation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Platforms | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCFA Analysis | GC-MS, LC-MS platforms; commercial SCFA standards; monocarboxylate transporter inhibitors | Quantifying SCFA production, transport, and tissue distribution | Butyrate has lowest systemic concentration due to colonocyte metabolism [18] |

| Neuro-transmitter Detection | HPLC with electrochemical detection; ELISA kits for serotonin/dopamine; receptor agonists/antagonists | Measuring neurotransmitter levels and receptor interactions | Peripheral vs. central neurotransmitter pools must be distinguished [19] |

| Tryptophan Pathway Tools | IDO/TDO inhibitors; kynurenine pathway metabolites; AhR agonists/antagonists | Manipulating tryptophan metabolic flux | Balance between neuroprotective KYNA and neurotoxic QUIN is critical [22] |

| Microbial Manipulation | Antibiotics cocktails; probiotic formulations; prebiotic fibers; gnotobiotic animal facilities | Establishing causal relationships between specific microbes and host physiology | Germ-free models show complete absence of microbial influence [22] [18] |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary microglial cultures; enteroendocrine cell lines; gut organoid systems | Mechanistic studies of host-microbe interactions | Co-culture systems required for cell-cell communication studies [19] |

| Zikv-IN-3 | Zikv-IN-3|Zika Virus Inhibitor|For Research | Zikv-IN-3 is a potent Zika virus inhibitor for research use only (RUO). It is not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Phaeosphaone D | Phaeosphaone D, MF:C20H27N3O3S2, MW:421.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The intricate communication network comprising the microbiota-gut-brain axis represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of how peripheral microbial communities influence central nervous system function and behavior. Microbial-derived metabolites, including SCFAs, neurotransmitters, and tryptophan derivatives, serve as essential messengers within this axis, mediating bidirectional communication through neural, endocrine, metabolic, and immune pathways. The evidence synthesized in this review underscores the fundamental role of diet as a primary modulator of this system, shaping microbial community structure and function with consequent effects on metabolite production.

Future research directions should prioritize elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms through which specific microbial metabolites influence brain physiology, particularly their effects on microglial function, neuroinflammation, and blood-brain barrier integrity. Advanced gnotobiotic models, multi-omics integration, and sophisticated imaging techniques will enable deeper exploration of the dynamic interplay between dietary factors, microbial metabolism, and neuronal signaling. From a therapeutic perspective, targeted interventions modulating microbial metabolite production—including precision probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics—hold significant promise for treating neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. As our understanding of these complex relationships matures, dietary and microbial-based interventions may emerge as viable strategies for optimizing brain health across the lifespan.

The human gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, plays a critical role in host physiology, influencing everything from digestion and metabolism to immune function and brain health [24] [25] [26]. Diet is one of the most potent modulators of this microbial community's composition and functional output. The intricate communication network between the gut and the brain, known as the gut-brain axis, involves neural, hormonal, immune, and microbial signaling pathways [24] [25]. Understanding how specific dietary components—fiber, polyphenols, fats, and proteins—influence the gut microbiome provides a scientific foundation for developing targeted nutritional strategies to support human health, a key pursuit in modern microbiota research.

Dietary Fiber and the Microbiome

Mechanisms of Microbial Fermentation

Dietary fibers (DFs) are complex, non-digestible carbohydrates that escape digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and reach the colon, where they serve as primary substrates for microbial fermentation [27]. This process is crucial for maintaining gut homeostasis. Fermentable fibers include a wide array of plant-derived polysaccharides such as pectin, arabinoxylan, beta-glucans, fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), inulin, and resistant starches [27]. The fermentation of these fibers by gut bacteria primarily results in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which include acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4) in an approximate ratio of 3:1:1 [27]. The ability to generate SCFAs is functionally redundant across different bacterial taxa, with acetate being produced by the majority of gut bacteria, while propionate and butyrate are synthesized by specific, functionally distinct groups [27].

Key SCFAs, Their Producers, and Host Functions

Table 1: Key Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), Their Microbial Producers, and Host Functions

| SCFA | Producing Genera | Host-Relevant Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Produced by a majority of gut bacteria; involved in cross-feeding. | Energy source; substrate for butyrate production; stimulates mucin 2 expression, mucus production and secretion [27]. |

| Propionate | Akkermansia, Bacteroides, Dialister, Phascolarctobacterium, Phocaeicola (succinate pathway); Anaerobutyricum, Blautia, Mediterraneibacter (propanediol pathway). | Substrate for gluconeogenesis; anti-inflammatory; reduces CD4+ T cell responses by inhibiting NF-κB and HDAC activity [27]. |

| Butyrate | Agathobacter, Anaerobutyricum, Anaerostipes, Butyricicoccus, Coprococcus, Faecalibacterium, Gemminger, Lachnospira, Oscillibacter, Roseburia, Ruminococcus. | Main energy source for colonocytes; enhances tight junction assembly and wound healing; increases mucin production; inhibits NF-κB; has anti-inflammatory immunoregulatory effects [27]. |

SCFAs exert their effects through multiple mechanisms. They serve as signaling molecules by binding to G-protein-coupled receptors (e.g., GPR41, GPR43) on epithelial, fat, and immune cells [27]. They also inhibit histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity, which can regulate T-cell differentiation and promote anti-inflammatory responses [27]. Butyrate is particularly vital for colonocyte health, providing up to 70% of their energy requirements and strengthening the gut barrier [27].

Experimental Insights

Protocol: Investigating SCFA Production from Fiber Fermentation

- In Vitro Fermentation Models: Systems like the in vitro Mucosal ARtificial COLon (M-ARCOL) simulate the human colon environment to study fiber fermentation and pathogen interactions [24].

- Intervention Design: Human trials often employ controlled diets supplemented with specific fibers (e.g., inulin, FOS, GOS, resistant starch). The Green-Mediterranean diet, rich in polyphenols and fiber, is an example of a whole-diet intervention [27].

- Sample Collection and Analysis: Fecal samples are collected pre-, during, and post-intervention. Microbiome profiling is performed via 16S rRNA gene sequencing or shotgun metagenomics. SCFA concentrations are quantified in fecal samples using techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [27].

- Key Findings: Supplementation with fiber- and polyphenol-rich foods consistently enriches SCFA-producing bacteria such as Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, Roseburia, and Blautia [27]. For instance, combining nuts with caloric restriction was shown to increase levels of propionic acid [27].

Bioactive Polyphenols and Microbial Modulation

Metabolism and Microbial Interactions

(Poly)phenols are a diverse group of bioactive compounds found in plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, tea, coffee, and cereals [25] [28]. Their bioavailability is limited in the upper GI tract, and a significant portion reaches the colon, where they are metabolized by the gut microbiota [28]. This microbial metabolism transforms complex polyphenols into more bioavailable and often more active metabolites, such as phenolic acids and urolithins [27] [25]. Polyphenols selectively modulate the gut microbiome, typically promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium) and inhibiting potential pathogens (e.g., Proteobacteria) [25] [28]. These shifts are associated with improved gut barrier function and anti-inflammatory effects.

Synergy with Dietary Fiber

Polyphenols and dietary fibers often coexist in plant cell walls, and their interaction creates a synergistic effect on gut health [28]. They can interact through covalent bonds (forming DF-polyphenol complexes) or non-covalent bonds (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions) [28]. This synergy enhances the production of health-promoting metabolites and supports microbial diversity more effectively than either component alone.

- Mechanisms of Synergy: DF acts as a delivery system, protecting polyphenols from early digestion and ensuring their arrival in the colon. The combined fermentation leads to increased SCFA production and greater enrichment of beneficial taxa compared to individual components [28].

- Health Implications: Diets rich in both DF and polyphenols, such as the Mediterranean diet, are linked to reduced risks of metabolic disorders, supported by enhanced SCFA production and gut barrier integrity [27] [28].

Diagram 1: Synergistic interaction between dietary polyphenols and fiber in shaping the gut microbiome and host health.

Dietary Proteins and Lipids: Complex Roles in Microbial Metabolism

Protein Fermentation: Dual Outcomes

Unlike carbohydrate fermentation, which primarily yields SCFAs, microbial fermentation of undigested dietary protein in the colon is a more complex process that generates a diverse range of metabolites with both beneficial and detrimental potential [29] [30].

Protocol: Assessing Protein Fermentation Products

- Model Systems: In vitro models (e.g., M-ARCOL) or animal models (e.g., gnotobiotic mice) are used to control protein sources and intake.

- Dietary Intervention: Participants consume defined diets varying in protein quantity and source (animal vs. plant). High-protein diets, especially from animal sources, are often tested [29] [30].

- Metabolite Profiling: Metabolites like branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs), ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, p-Cresol, and indoles are measured in fecal samples using GC-MS and LC-MS. BCFAs are reliable markers of proteolytic fermentation [29].

- Microbiome Analysis: 16S rRNA sequencing tracks shifts in microbial composition. Bacteria from phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria are often implicated in proteolysis [29].

Protein fermentation products have been linked to increased inflammatory response, tissue permeability, and colitis severity in the gut, and are implicated in obesity, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [29]. Conversely, some tryptophan metabolites (e.g., indole derivatives) can activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, improving gut barrier function and providing anti-inflammatory benefits [29].

Lipid Metabolism and Microbial Influence

The gut microbiota can both transform and synthesize lipids, as well as break down dietary lipids to generate secondary metabolites with host modulatory properties [26] [31]. Bioactive lipids derived from microbial metabolism impact host physiology, particularly immunity and metabolism [31].

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): As previously detailed, these fiber fermentation products also influence lipid metabolism by serving as signaling molecules and energy sources, affecting insulin sensitivity and fat storage [27] [26].

- Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO): Gut microbes metabolize dietary choline and L-carnitine (abundant in red meat) into trimethylamine (TMA), which is then oxidized in the liver to TMAO. Elevated TMAO levels are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [25] [26].

- Bile Acid Metabolism: The gut microbiota modifies primary bile acids into secondary bile acids through enzymatic activities like bile salt hydrolase (BSH). This process regulates host lipid metabolism, cholesterol homeostasis, and immune signaling [26].

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS): LPS, a component of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, can translocate into systemic circulation, particularly under high-fat diet conditions, triggering low-grade chronic inflammation ("metabolic endotoxemia") that is linked to insulin resistance and obesity [26].

Table 2: Impact of Dietary Components on Gut Microbiota and Host Physiology

| Dietary Component | Key Microbial Shifts | Major Microbial Metabolites | Potential Health Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber | ↑ Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Blautia, Bifidobacterium | SCFAs (Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate) | Enhanced gut barrier integrity, anti-inflammation, improved metabolic health [27] [28]. |

| Polyphenols | ↑ Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus; ↓ Proteobacteria | Phenolic acids (e.g., Urolithins) | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective effects [27] [25] [28]. |

| Dietary Protein (High) | ↑ Bacteroides, Alistipes, Firmicutes; ↓ Bifidobacterium | BCFAs, Ammonia, H₂S, p-Cresol | Increased gut permeability, inflammation; potential risk for metabolic disease & CRC [29] [30]. |

| Dietary Lipids (High/Saturated) | ↑ LPS-producing bacteria; altered bile acid metabolism | TMAO, Secondary Bile Acids, LPS | Systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, increased CVD risk [26] [31]. |

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Translational Perspective

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system where the gut microbiota plays a central role, influencing emotional regulation, brain function, and even dietary behaviors [24] [25]. Microbial metabolites, including SCFAs, neurotransmitter precursors (e.g., serotonin, GABA), and immune modulators, are critical mediators of this communication [24] [25] [32].

- Neuroinflammation and Ageing: Low-grade chronic inflammation, or "inflammageing," is promoted by gut microbiota and is a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases [25]. Dietary (poly)phenols can modulate the gut microbiota to reduce intestinal permeability and lower pro-inflammatory gut bacteria-derived mediators, thereby potentially attenuating neuroinflammation [25] [32].

- Experimental Evidence: Exploratory analyses have linked gut microbiota composition to conditions like ADHD and reactive aggression, with high-energy intake associated with higher aggression scores [24]. Furthermore, specific microbial-derived metabolites have been linked to depression and quality of life, leading to the identification of "gut-brain modules" for neuroactive compound production [32].

Diagram 2: Key pathways of the microbiota-gut-brain axis, highlighting the role of diet and microbial metabolites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Models for Gut Microbiome Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Colon Models | Simulates human colon environment for studying fermentation, pathogen interactions, and metabolite production. | M-ARCOL (Mucosal ARtificial COLon); allows testing of life-threatening pathogens like EHEC [24]. |

| Gnotobiotic Mice | Germ-free animals colonized with specific microbes; essential for establishing causal relationships between microbes and host phenotype. | Used to demonstrate that gut microbiome from obese donors can increase fat mass in recipients [26]. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Profiling microbial community composition and diversity based on the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. | Standard method; often performed on Illumina MiSeq or similar platforms [24] [33]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Unbiased sequencing of all genetic material in a sample; allows for functional gene analysis and strain-level resolution. | Hi-seq-PacBio hybrid method for characterizing low-abundance species [26]. |

| GC-MS / LC-MS | Gas or Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry for identifying and quantifying metabolites (SCFAs, BCFAs, TMAO, etc.). | Crucial for measuring the metabolic output of the microbiome [27] [29]. |

| Prebiotics & Probiotics | Defined supplements to modulate the gut microbiome in intervention studies. | Prebiotics: Inulin, FOS, GOS. Probiotics: Bifidobacterium longum APC1472 (shown to have anti-obesity effects) [27] [32]. |

| D-Lyxose-13C-3 | D-Lyxose-13C-3, MF:C5H10O5, MW:151.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anti-ToCV agent 1 | Anti-ToCV agent 1, MF:C22H19FN2O5S, MW:442.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence is unequivocal: diet profoundly shapes the gut microbiome, with specific components like fiber, polyphenols, proteins, and fats dictating microbial composition and metabolic output. These microbial changes, in turn, have far-reaching consequences for host health, including metabolic, immune, and neurological outcomes via the gut-brain axis. The synergistic effects of dietary components, particularly fiber and polyphenols, highlight the superiority of whole-diet approaches over isolated nutrients. Future research must focus on mechanistic, longitudinal human studies and account for individual microbiota variability to realize the full potential of personalized, microbiome-targeted dietary interventions for improving human health.

The microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) represents a critical bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract with the central nervous system (CNS). Growing evidence indicates that gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbial community, and compromised intestinal barrier integrity are intimately involved in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Dysbiosis can trigger a cascade of events including increased intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, impaired blood-brain barrier function, and ultimately neuroinflammation through multiple pathways. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the mechanisms by which gut barrier dysfunction contributes to neuroinflammation, details experimental methodologies for investigating these relationships, and explores potential therapeutic interventions targeting the gut-brain axis. The content is framed within the context of how dietary patterns significantly influence MGBA communication, thereby modulating neurodegenerative disease risk and progression.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex ecosystem of microorganisms collectively known as the gut microbiota, which plays a fundamental role in host physiology, immune function, and nervous system homeostasis [34]. The concept of the microbiota-gut-brain axis (MGBA) has emerged as a pivotal framework for understanding how gut microbes communicate with the brain through neural, endocrine, immune, and metabolic pathways [15]. Recent research has illuminated how disruption of this delicate ecosystem—termed gut dysbiosis—can compromise intestinal barrier integrity, leading to systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation that potentially drives neurodegenerative pathologies including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and others [34] [15].

The intestinal barrier, comprised of a single layer of epithelial cells joined by tight junction proteins, serves as a critical interface regulating the passage of nutrients while restricting the translocation of harmful substances and microorganisms [35]. When this barrier becomes compromised, a condition often referred to as "leaky gut," bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can enter systemic circulation, triggering immune responses that may ultimately affect brain function [36]. This review comprehensively examines the links between gut dysbiosis, barrier integrity, and neuroinflammation, with particular emphasis on mechanistic insights, experimental approaches, and the modulatory role of diet within this context.

Gut Dysbiosis and Pathological Mechanisms

Definition and Features of Gut Dysbiosis

Gut dysbiosis refers to an alteration in the composition and function of the gut microbiota, typically characterized by:

- Reduced microbial diversity

- Loss of beneficial microorganisms

- Overgrowth of potentially pathogenic species

- Shifts in metabolic capacity and functional output

In healthy adults, the gut microbiota is dominated by the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, with specific beneficial genera including Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium [34] [37]. Dysbiotic states associated with neurodegenerative diseases often show:

- Increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [37]

- Reduced abundance of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria

- Increased abundance of pro-inflammatory microbes such as Escherichia and Clostridium species [34]

Table 1: Microbial Taxa Associated with Dysbiosis in Neurodegenerative Conditions

| Taxonomic Level | Associated Taxa | Change in Dysbiosis | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Firmicutes | Increased | Potential pro-inflammatory effects |

| Phylum | Bacteroidetes | Decreased | Reduced SCFA production |

| Genus | Escherichia | Increased | LPS production, inflammation |

| Genus | Clostridium | Increased | Toxin production |

| Genus | Bacteroides | Decreased | Reduced immune regulation |

| Genus | Lactobacillus | Decreased | Reduced GABA production |

| Genus | Bifidobacterium | Decreased | Reduced anti-inflammatory mediators |

Mechanisms Linking Gut Dysbiosis to Neuroinflammation

Several interconnected mechanisms explain how gut dysbiosis contributes to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration:

Bacterial Amyloids and LPS Production: Certain gut bacteria produce bacterial amyloids and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that can trigger macrophage dysfunction, increase gut permeability, and promote systemic inflammation [34]. These bacterial products can cross the compromised intestinal barrier and travel to the brain, where they may activate microglia and promote the aggregation of pathological proteins like Aβ and α-synuclein [34] [15].

Immune System Activation: Dysbiosis can lead to hyperimmune activation and increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, as well as activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [34]. These inflammatory mediators can breach the blood-brain barrier, activating microglia and astrocytes, which subsequently produce additional neuroinflammatory molecules [34] [15].

Vagus Nerve Signaling: The vagus nerve serves as a direct communication pathway between the gut and brain. Gut microbes and their metabolites can stimulate vagal afferents, influencing brain function and behavior. Interestingly, the vagus nerve may also serve as a physical conduit for the transmission of protein aggregates in a prion-like manner [34].

Microbial Metabolite Production: Gut microbiota produce numerous neuroactive metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA, dopamine), and bile acid metabolites that can directly or indirectly influence brain function [34] [7]. Dysbiosis alters the production of these metabolites, potentially disrupting neuro-immune homeostasis.

Intestinal Barrier Structure and Regulation

Anatomy of the Intestinal Barrier

The intestinal barrier consists of multiple components working in concert:

- Mucosal Layer: A glycoprotein layer secreted by goblet cells that forms the first physical and chemical barrier

- Epithelial Cell Layer: A single layer of specialized intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) including enterocytes, goblet cells, Paneth cells, and enteroendocrine cells

- Junctional Complexes: Multi-protein structures that seal the paracellular space between epithelial cells

- Immune Cells: Located in the lamina propria, including dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, and macrophages

Tight Junction Proteins and Regulation

Tight junctions are the most apical component of the junctional complexes and represent the primary determinant of paracellular permeability [35]. Key tight junction proteins include:

Table 2: Major Tight Junction Proteins and Their Functions

| Protein | Function | Role in Barrier Integrity |

|---|---|---|

| Occludin | First identified tight junction protein; provides structural integrity | Crucial for tight junction stability rather than assembly |

| Claudins | Large family of proteins with different isoforms; regulate paracellular transport | Different isoforms have opposing effects on permeability |

| Zonula Occludens (ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3) | Cytosolic scaffold proteins; link transmembrane proteins to actin cytoskeleton | Essential for tight junction formation and maintenance |

| Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs) | Immunoglobulin-like transmembrane proteins | Contribute to barrier maintenance; JAM-A deficiency increases permeability |

The expression and function of tight junction proteins are regulated by multiple signaling pathways, including those involving small GTP-binding proteins, tyrosine kinases (c-Src, c-Yes), and protein kinase C (PKC) [35]. Inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ can disrupt tight junction integrity, increasing paracellular permeability.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Assessing Intestinal Permeability In Vivo