Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Prevention: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical and Public Health Translation

This article synthesizes the latest epidemiological and clinical evidence on the role of dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Prevention: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical and Public Health Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest epidemiological and clinical evidence on the role of dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational associations between diets like the Mediterranean, DASH, and plant-based patterns with outcomes spanning cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and healthy aging. The content delves into methodological approaches for dietary assessment and pattern analysis, examines challenges in implementation and optimization for diverse populations, and provides a comparative validation of various diets through network meta-analyses and biomarker studies. The review aims to bridge nutritional science with biomedical research, highlighting implications for future therapeutic strategies and public health guidelines.

Epidemiological Evidence: Linking Dietary Patterns to Chronic Disease Risk and Healthy Aging

Dietary patterns represent the combination of foods and beverages consumed over time, providing a holistic view of dietary habits that accounts for complex interactions between nutrients. Within nutritional epidemiology, the analysis of dietary patterns has emerged as a superior approach to studying the relationship between diet and chronic diseases, moving beyond the limitations of single-food or single-nutrient studies. This technical guide examines five predominant dietary patterns—AHEI, Mediterranean, DASH, MIND, and Plant-Based Diets—within the context of chronic disease research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of their defining components, associated health outcomes, biological mechanisms, and research methodologies.

The global burden of diet-related chronic diseases continues to escalate, with poor nutrition responsible for 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life-years globally [1]. Chronic diseases account for more than half of all premature deaths and over 90% of yearly healthcare spending in the United States alone [1]. Understanding how dietary patterns influence disease pathways provides critical insights for preventive strategies and therapeutic development.

Dietary Pattern Definitions and Component Analysis

The five dietary patterns examined in this guide share common elements but differ in their specific emphasis and scoring approaches. The Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) was developed by Harvard nutritionists as a scoring system to predict chronic disease risk, with higher scores indicating lower risk [2]. The Mediterranean diet is inspired by traditional eating patterns in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, emphasizing plant-based foods, healthy fats, and moderate fish and poultry consumption [3]. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) was specifically designed to prevent and treat hypertension through sodium reduction and increased consumption of potassium-rich foods [3]. The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet hybridizes the Mediterranean and DASH diets with specific emphasis on neuroprotective foods [4]. Plant-Based Diets encompass a spectrum from vegetarian to vegan patterns, with the healthful plant-based diet index (hPDI) distinguishing between healthful and unhealthful plant foods [5].

Comparative Component Analysis

Table 1: Core Food Components of Major Dietary Patterns

| Food Component | AHEI | Mediterranean | DASH | MIND | Healthful Plant-Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | 5+ servings/day | High variety | 4-5 servings/day | 6+ servings leafy greens/week | Unlimited |

| Fruits | 4+ servings/day | Moderate | 4-5 servings/day | Berries emphasized (2+ servings/week) | Unlimited |

| Whole Grains | 5-6 servings/day | Moderate | 6-8 servings/day | 3+ servings/day | Emphasized |

| Nuts & Legumes | Daily | Daily | 4-5 servings/week | Nuts: 5+ servings/week; Legumes: 4+ servings/week | Emphasized |

| Fish/Poultry | Fish limited | Fish: 2+ servings/week; Poultry: moderate | Lean proteins emphasized | Fish: 1+ serving/week; Poultry: 2+ servings/week | Excluded or limited |

| Dairy | Limited | Moderate cheese/yogurt | Low-fat emphasized | Limited | Excluded (vegan) or limited |

| Fats | Unsaturated oils | Olive oil primary | Moderate total fat | Olive oil primary | Plant oils |

| Sodium | Limited | Not restricted | <1,500 mg/day | Not explicitly restricted | Not restricted |

| Red/Processed Meats | Limited | Limited | Limited | <4 servings/week | Excluded |

| Sweets | Limited | Limited | Limited | <5 servings/week | Limited |

Table 2: Scoring Systems and Health Outcomes for Dietary Patterns

| Dietary Pattern | Scoring Method | Primary Chronic Disease Association | Key Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHEI | 0-110 scale based on adherence to food targets | Multifactorial chronic disease reduction | 86% higher odds of healthy aging [6]; 1.86 OR for healthy aging (highest vs. lowest quintile) [7] |

| Mediterranean | 0-9 scale based on median consumption of beneficial foods | Cardiovascular disease, diabetes | Improved lipid profiles, reduced CVD mortality [3] |

| DASH | 1-5 scale based on quintiles of food group intake | Hypertension, metabolic syndrome | Blood pressure reduction, diabetes risk reduction [3] |

| MIND | 0-15 score based on 10 brain-healthy and 5 unhealthy food groups | Neurodegenerative conditions, dementia | 53% lower Alzheimer's risk [4]; Reduced dementia (HR=0.87), depression (HR=0.77) [8] |

| Healthful Plant-Based | hPDI index scoring plant foods positively, with distinction between healthful/unhealthful | Cognitive impairment, cardiovascular disease | 45% higher odds of healthy aging [7]; 0.68 OR for cognitive impairment (highest vs. lowest hPDI) [5] |

Methodological Approaches in Dietary Pattern Research

Cohort Studies and Longitudinal Designs

Large-scale prospective cohort studies form the foundation of dietary pattern research. The Nurses' Health Study (NHS), Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), and UK Biobank represent gold standard methodologies with extended follow-up periods. The NHS and HPFS collectively followed 205,852 healthcare professionals for up to 32 years, with dietary assessments every 2-4 years using validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) [1]. The UK Biobank study analyzed 166,916 participants over a median follow-up of 10.5 years, examining associations between ten dietary patterns and five major brain disorders [8].

Dietary assessment typically employs semi-quantitative FFQs that capture usual intake of 100-150 food items. The data processing workflow includes: (1) nutrient calculation using composition databases; (2) derivation of dietary pattern scores based on predefined algorithms; (3) energy adjustment using residual or density methods; (4) categorization into quintiles or quartiles of adherence; and (5) statistical modeling with multivariate adjustment for confounding factors including age, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, and total energy intake.

Statistical Analysis Protocols

Cox proportional hazards models serve as the primary analytical framework for time-to-event data, calculating hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for disease incidence across adherence levels to dietary patterns. For cross-sectional analyses of healthy aging outcomes, logistic regression models compute odds ratios (ORs) comparing extreme quintiles of dietary pattern adherence [7]. Meta-analyses employ fixed-effects or random-effects models to pool estimates across multiple studies, with statistical heterogeneity quantified using I² statistics [5].

Recent methodological advances incorporate mediation analyses to elucidate biological pathways. For example, the UK Biobank study used four-way decomposition models with multi-omics data (metabolomics, genomics, proteomics) to quantify proportion mediated through specific biological pathways [8]. This approach identified that a favorable metabolic signature mediated 60.63% of the MIND diet's protective effect against stroke, 38.97% for depression, and 26.06% for anxiety [8].

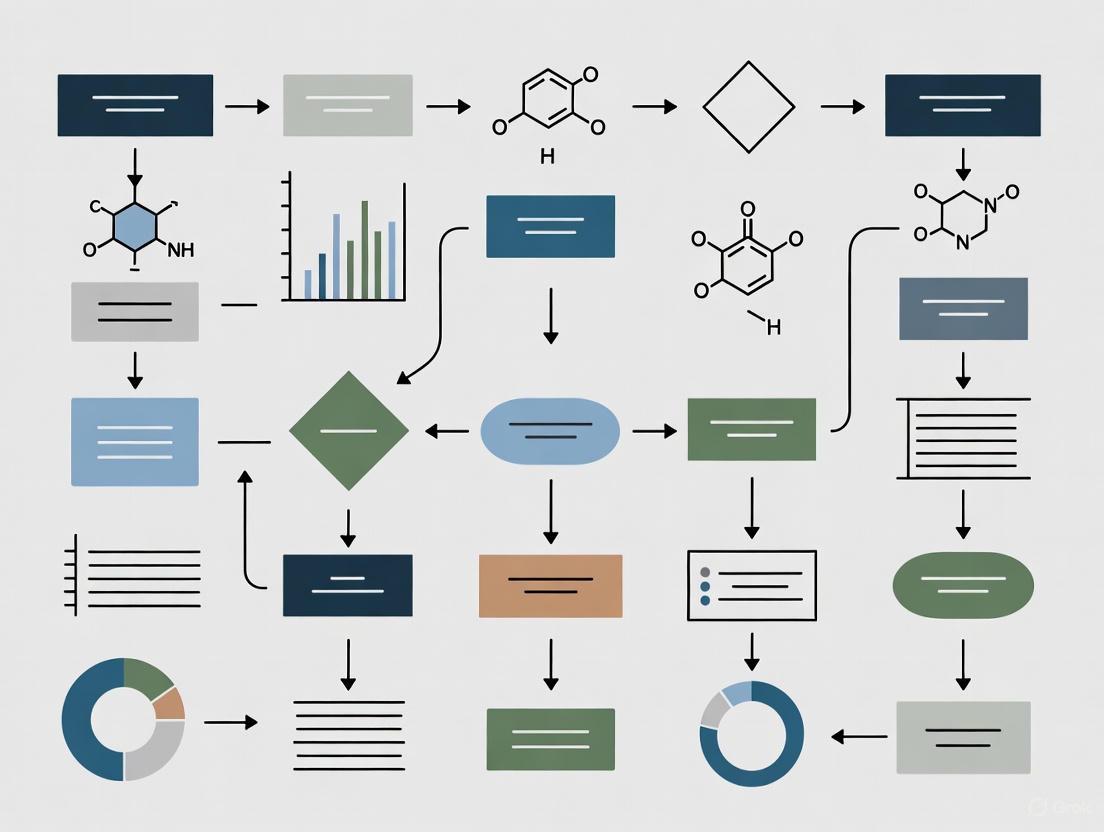

Diagram 1: Research workflow for dietary pattern studies

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Dietary Pattern Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assess habitual dietary intake over extended periods | Harvard FFQ (131 food items, semiquantitative) used in NHS/HPFS cohorts [1] [7] |

| Dietary Pattern Scoring Algorithms | Quantify adherence to specific dietary patterns | AHEI (0-110), Mediterranean (0-9), MIND (0-15) scores based on food group intake [7] [4] |

| Multi-omics Platforms | Identify biological mediators between diet and health outcomes | Metabolomic profiling to quantify proportion mediated for depression (38.97%), anxiety (26.06%) [8] |

| Cox Proportional Hazards Models | Analyze time-to-event data for disease incidence | HRs for dementia, stroke, depression across dietary pattern adherence levels [8] |

| Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort Models | Project future disease burden attributable to dietary factors | Projected ASMR for diet-related chronic diseases through 2030 using GBD data [9] |

Health Outcomes and Mechanistic Pathways

Chronic Disease Risk Reduction

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate consistent associations between dietary patterns and chronic disease risk. For cognitive outcomes, higher adherence to healthful plant-based diets is associated with significantly lower odds of cognitive impairment (OR=0.68 for hPDI, highest vs. lowest quartile) and reduced dementia risk (HR=0.85 for hPDI) [5]. The MIND diet shows particularly broad neuroprotective effects, with risk reduction for dementia (HR=0.87), stroke (HR=0.89), depression (HR=0.77), and anxiety (HR=0.82) [8].

For cardiometabolic diseases, comparative effectiveness research demonstrates that dietary patterns emphasizing insulinemic and inflammatory mechanisms show superior risk reduction. The reversed empirical dietary index for hyperinsulinemia (rEDIH) and reversed empirical dietary inflammatory pattern (rEDIP) show the strongest associations with major chronic disease risk reduction (HR=0.58 and HR=0.61, respectively, comparing 90th to 10th percentile) [1]. These patterns outperform even established dietary recommendations for CVD, diabetes, and cancer risk reduction in composite outcomes.

Biological Mechanisms Linking Diet to Chronic Diseases

The protective effects of healthful dietary patterns operate through multiple interconnected biological pathways. Oxidative stress reduction occurs through antioxidant compounds (flavonoids, carotenoids, vitamins C and E) that neutralize reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [10]. Anti-inflammatory effects manifest through reduced inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, IL-6) and modulation of the empirical dietary inflammatory pattern (EDIP) [1] [7].

Metabolic regulation pathways include improved insulin sensitivity, reduced hyperinsulinemia, and favorable lipid profiles [1]. Gut microbiome modulation occurs through prebiotic effects of dietary fiber and polyphenols, which influence microbial community structure and metabolite production [10]. Slower biological aging mediates a significant proportion of dementia risk reduction (19.40%) associated with the MIND diet [8].

Diagram 2: Biological mechanisms linking dietary patterns to health outcomes

Healthy Aging Outcomes

Beyond disease-specific outcomes, dietary patterns significantly influence multidimensional healthy aging. In a 30-year study of 105,015 participants, higher adherence to all dietary patterns was associated with greater odds of healthy aging—defined as reaching age 70 free of major chronic diseases while maintaining intact cognitive, physical, and mental health [7]. The AHEI demonstrated the strongest association (OR=1.86, highest vs. lowest quintile), followed by rEDIH, while hPDI showed the most modest association (OR=1.45) [7].

When examining specific aging domains, dietary patterns showed varying protective effects. For intact cognitive function, the Planetary Health Diet Index showed the strongest association (OR=1.65), while for intact physical function, AHEI demonstrated the strongest association (OR=2.30) [7]. These findings suggest that while all healthful dietary patterns promote healthy aging, specific patterns may offer domain-specific advantages.

The evidence reviewed in this technical guide demonstrates that dietary patterns emphasizing plant-based foods, healthy fats, whole grains, and lean proteins while limiting red and processed meats, sodium, and ultra-processed foods consistently associate with reduced chronic disease risk and promoted healthy aging. The AHEI, Mediterranean, DASH, MIND, and healthful plant-based diets share common elements but offer distinct advantages for specific health outcomes.

From a research perspective, the field requires more randomized controlled trials to establish causality, greater diversity in study populations to enhance generalizability, and deeper investigation into the molecular mechanisms mediating dietary effects. For drug development professionals, understanding these dietary patterns provides insights into modifiable risk factors that could complement pharmacological interventions. Future research should prioritize personalized nutrition approaches that identify which dietary patterns provide optimal benefit for specific genetic, metabolic, or microbiome profiles.

For nearly five decades, the Nurses' Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) have generated critical evidence illuminating the relationship between dietary patterns and chronic disease risk. Established as large-scale prospective investigations, these cohorts were designed to evaluate long-term hypotheses about how nutritional factors impact serious illnesses including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes [11] [12]. The NHS, initiated in 1976 under Dr. Frank Speizer, originally sought to investigate the long-term consequences of oral contraceptives, while the HPFS was established in 1986 by Dr. Walter Willett and colleagues to complement the NHS with an all-male cohort [11] [12]. Together, these studies have followed hundreds of thousands of healthcare professionals, leveraging their expertise to collect precise health information over decades through detailed biennial and dietary-specific questionnaires.

This whitepaper synthesizes key methodological approaches and foundational findings from these cohorts, with particular focus on their contributions to understanding how dietary patterns influence chronic disease pathogenesis. The unparalleled longitudinal data from these studies provides an evidence base that continues to inform both public health guidelines and targeted therapeutic development.

Cohort Methodologies: Design and Data Collection Protocols

Population Recruitment and Characteristics

The NHS and HPFS employed distinct but methodologically complementary recruitment strategies to establish their cohorts:

- NHS Original Cohort: In 1976, the study enrolled 121,700 married female registered nurses aged 30-55 from 11 populous U.S. states. Nurses were selected for their ability to provide accurate health information and maintain long-term participation [12].

- NHS II: Established in 1989 with 116,430 female nurses aged 25-42 to study diet, lifestyle, and oral contraceptive use in a younger population [12].

- HPFS: Launched in 1986 with 51,529 male health professionals aged 40-75 from various disciplines including dentistry, pharmacy, optometry, and veterinary medicine [11].

Longitudinal Data Collection Framework

Both studies implement rigorous, standardized protocols for ongoing data collection:

- Core Follow-up Questionnaires: Biennial surveys tracking disease incidence, weight, smoking status, physical activity, medication use, and menopausal status [11] [12].

- Dietary Assessments: Comprehensive food-frequency questionnaires (FFQs) administered every four years to quantify nutritional intake, including detailed questions on over 130 food items, portion sizes, and preparation methods [12].

- Biological Specimens: Systematic collection of blood, urine, toenail, and DNA samples from subsets of participants to analyze biomarkers, genetic factors, and their interactions with dietary exposures [12].

Table: Cohort Characteristics and Design Elements

| Characteristic | NHS (Original) | NHS II | HPFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Launch Year | 1976 | 1989 | 1986 |

| Initial Cohort Size | 121,700 | 116,430 | 51,529 |

| Baseline Age Range | 30-55 | 25-42 | 40-75 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Male |

| Diet Assessment Interval | Every 4 years | Every 4 years | Every 4 years |

| Health Update Interval | Every 2 years | Every 2 years | Every 2 years |

| Biospecimen Collection | Blood, urine, toenails, DNA | Blood, urine, DNA | Blood, urine, DNA |

Dietary Pattern Operationalization

Researchers have developed and validated numerous dietary indices to quantify adherence to various eating patterns:

- Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI): Scores intake of foods and nutrients predictive of chronic disease risk [13].

- Alternative Mediterranean Diet Score (aMED): Measures adherence to traditional Mediterranean dietary patterns [7].

- Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH): Assesses concordance with the DASH diet, emphasizing fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy [1].

- Healthful Plant-Based Diet Index (hPDI): Scores emphasizing healthy plant foods while distinguishing from less healthy plant foods [7].

- Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP): Derived from inflammatory biomarkers to assess diet's inflammatory potential [1].

Key Findings: Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Risk

Healthy Aging and Multidimensional Health Outcomes

A 2025 analysis published in Nature Medicine followed 105,015 participants from NHS and HPFS for up to 30 years to examine associations between dietary patterns and healthy aging, defined as surviving to age 70 years free of major chronic diseases and maintaining intact cognitive, physical, and mental health [7]. The findings demonstrated that:

- Higher adherence to all eight dietary patterns studied was associated with significantly greater odds of healthy aging, with multivariable-adjusted odds ratios comparing highest to lowest quintiles ranging from 1.45 for hPDI to 1.86 for AHEI [7].

- When the healthy aging threshold was raised to age 75 years, the AHEI showed the strongest association with an odds ratio of 2.24 [7].

- Higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, unsaturated fats, nuts, legumes, and low-fat dairy were consistently associated with greater odds of healthy aging across all domains [7].

Table: Dietary Patterns and Healthy Aging Outcomes in NHS and HPFS

| Dietary Pattern | Odds Ratio (Highest vs. Lowest Quintile) | Strongest Health Domain Association |

|---|---|---|

| AHEI | 1.86 (95% CI: 1.71-2.01) | Mental Health (OR: 2.03) |

| aMED | 1.72 (95% CI: 1.58-1.87) | Physical Function (OR: 1.95) |

| DASH | 1.73 (95% CI: 1.59-1.88) | Physical Function (OR: 1.92) |

| MIND | 1.65 (95% CI: 1.52-1.79) | Mental Health (OR: 1.81) |

| hPDI | 1.45 (95% CI: 1.35-1.57) | Survival to Age 70 (OR: 1.33) |

| PHDI | 1.68 (95% CI: 1.55-1.82) | Cognitive Health (OR: 1.65) |

Major Chronic Disease Prevention

Research across these cohorts has consistently demonstrated that healthy dietary patterns significantly reduce the risk of major chronic diseases in composite:

- A study following 205,852 participants from NHS, NHS II, and HPFS for up to 32 years found that adherence to healthy dietary patterns was associated with hazard ratios of 0.58-0.80 for major chronic disease (composite of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer) when comparing the 90th to 10th percentile of dietary pattern scores [1].

- Diets characterized by low insulinemic potential (HR: 0.58), low inflammatory potential (HR: 0.61), or diabetes risk-reducing patterns (HR: 0.70) showed the strongest inverse associations [1].

- The AHEI demonstrated particularly strong protective effects against cardiovascular disease, with multivariate relative risks of 0.61 in men and 0.72 in women when comparing highest to lowest quintiles [13].

Disease-Specific Risk Reductions

Recent analyses have quantified associations between dietary patterns and individual chronic diseases:

- The Alternative Mediterranean Diet score demonstrated the broadest protection, associated with significantly lower risk of 32 individual chronic diseases across cardiometabolic, cancer, psychological/neurological, digestive, and other disease categories [14].

- Higher AMED scores were specifically associated with reduced risk of lung cancer (HR: 0.93), dementia (HR: 0.92), Parkinson's disease (HR: 0.92), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR: 0.88) per quintile increment in scores [14].

- All dietary patterns studied showed significant inverse associations with digestive disorders including dyspepsia, diverticular disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic liver disease [14].

Mechanistic Insights: Biomarkers and Biological Pathways

Inflammation and Immune Function

Dietary patterns significantly influence inflammatory biomarkers that mediate chronic disease risk:

- The Mediterranean diet demonstrated the most potent anti-inflammatory effects among dietary patterns, with meta-analyses showing significant reductions in IL-6 (mean difference: -1.07 pg/mL), IL-1β (mean difference: -0.46 pg/mL), and C-reactive protein [15].

- The Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP), developed and validated in these cohorts, provides a food-based index for estimating the inflammatory potential of diet, with higher scores associated with elevated inflammatory biomarkers and increased chronic disease risk [1].

Metabolic Pathways

Dietary patterns influence chronic disease risk through multiple metabolic mechanisms:

- The Empirical Dietary Index for Hyperinsulinemia (EDIH) identifies diets associated with plasma C-peptide concentrations, providing a biomarker-based approach to assessing diets that modulate insulin response [1].

- Diets high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes improve glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, thereby reducing diabetes risk and related complications [1].

- Specific dietary components including trans fats, sodium, and red/processed meats demonstrate adverse effects on metabolic health, while unsaturated fats, nuts, and low-fat dairy show beneficial effects [7].

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Assets

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Dietary Assessment Tools | Semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), Diet History Questionnaires | Standardized quantification of nutritional intake and dietary patterns |

| Biological Specimen Repositories | Plasma/serum, urine, DNA, toenail samples (63,000 in NHS) | Biomarker analysis, genetic studies, nutrient biomarker calibration |

| Dietary Pattern Indices | AHEI, aMED, DASH, hPDI, EDIP, EDIH | Standardized quantification of adherence to specific dietary patterns |

| Disease Validation Instruments | Medical record review protocols, supplemental disease-specific questionnaires | Endpoint adjudication and validation for specific disease outcomes |

| Genetic Data | Genome-wide association data, candidate gene polymorphisms | Gene-diet interaction studies, Mendelian randomization analyses |

Visualizing Cohort Research Workflows

Cohort Study Design and Analytical Approach

Cohort Research Workflow

Dietary Pattern Influence on Chronic Disease Pathways

Diet-Chronic Disease Pathways

Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

The longitudinal evidence from NHS and HPFS provides critical insights for researchers and drug development professionals:

- Biomarker Validation: These cohorts have identified and validated numerous biomarkers (inflammatory, metabolic, nutritional) that can serve as intermediate endpoints in clinical trials, potentially reducing study duration and costs [15].

- Precision Nutrition Applications: Findings that dietary effects may be modified by factors such as sex, BMI, and smoking status highlight opportunities for targeted nutritional interventions [7].

- Combination Therapy Development: Understanding dietary mechanisms can inform development of pharmaceuticals that complement or enhance dietary interventions, particularly for metabolic and inflammatory conditions.

- Preventive Medicine Strategies: The robust association between dietary patterns and multimorbidity reduction supports integrative approaches that combine nutritional interventions with conventional therapeutics.

The continued follow-up of these cohorts, alongside emerging molecular data and advanced analytical methods, promises to further elucidate the complex relationships between diet, biological mechanisms, and chronic disease risk, offering valuable insights for the development of targeted interventions and therapeutic strategies.

Within the broader thesis investigating the link between dietary patterns and chronic disease, the role of nutrition in modulating multidimensional healthy aging represents a critical frontier. As the global population ages, the imperative to extend healthspan—the years lived in good physical, cognitive, and mental health—has intensified, shifting focus from merely delaying mortality to preserving functional capacity [16]. Diet stands as a first-line behavioral risk factor for non-communicable diseases and mortality burden, second only to tobacco use in older U.S. adults [7]. This whitepaper synthesizes evidence from large-scale prospective cohorts, randomized controlled trials, and emerging molecular studies to delineate the association between long-term dietary patterns and multidimensional health outcomes in aging populations. The findings herein are intended to guide future research, inform public health policy, and identify potential targets for therapeutic and drug development aimed at chronic disease prevention and healthspan extension.

Key Dietary Patterns and Their Associations with Multidimensional Health

Research has consistently identified several dietary patterns associated with healthy aging. A landmark 30-year prospective study published in Nature Medicine (2025), utilizing data from the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (n=105,015), provides the most comprehensive evidence to date [7] [17]. The study defined healthy aging as surviving to age 70 years or older with intact cognitive, physical, and mental health, and freedom from major chronic diseases. Only 9.3% of the cohort achieved this multidomain outcome, underscoring its stringency [7] [17].

The study evaluated eight dietary patterns, all of which emphasized high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, unsaturated fats, nuts, and legumes, with variations in the inclusion of animal-based foods. The association between higher adherence to these patterns and the likelihood of healthy aging was robust and statistically significant (p<0.0001) [7]. The table below summarizes the key associations for the highest versus lowest quintiles of adherence.

Table 1: Association of Dietary Pattern Adherence with Odds of Healthy Aging and Its Domains

| Dietary Pattern | Full Name | Odds Ratio for Healthy Aging (Highest vs. Lowest Quintile) | Key Associations with Aging Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHEI | Alternative Healthy Eating Index | 1.86 (95% CI: 1.71–2.01) [7] | Strongest association with intact physical and mental health [7]. |

| rEDIH | reverse Empirical Dietary Index for Hyperinsulinemia | 1.83 (95% CI: Not specified in source) [7] | Strongest association with freedom from chronic diseases [7]. |

| DASH | Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension | 1.84 (95% CI: Not specified in source) [7] | Consistently associated with all healthy aging domains [7]. |

| aMED | Alternative Mediterranean Index | 1.81 (95% CI: Not specified in source) [7] | Associated with reduced inflammation and improved cognitive function [7] [16]. |

| PHDI | Planetary Health Diet Index | 1.71 (95% CI: Not specified in source) [7] | Strongest association with surviving to age 70 and intact cognitive health [7]. |

| MIND | Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay | 1.59 (95% CI: Not specified in source) [7] | Specifically designed for brain health; associated with slower cognitive decline [18] [19]. |

| rEDIP | reverse Empirical Inflammatory Dietary Pattern | 1.52 (95% CI: Not specified in source) [7] | Weaker association with intact physical function [7]. |

| hPDI | healthful Plant-Based Diet Index | 1.45 (95% CI: 1.35–1.57) [7] | Weakest association with all healthy aging domains, including cognitive health [7]. |

The AHEI diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, and healthy fats while low in red/processed meats, sugary beverages, sodium, and refined grains, demonstrated the most potent association, nearly doubling the odds of healthy aging [7] [17]. When the healthy age threshold was raised to 75 years, this association strengthened further (OR=2.24, 95% CI: 2.01–2.50) [7]. The MIND diet, a hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH diets, has shown significant promise for cognitive health, with numerous observational studies linking it to slower global cognitive decline and reduced risk of dementia [18] [19].

Table 2: Association of Specific Food Groups with Odds of Healthy Aging

| Food/Nutrient | Direction of Association with Healthy Aging | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits, Vegetables, Whole Grains | Positive [7] | Foundation of all beneficial dietary patterns. |

| Nuts, Legumes | Positive [7] | Key components of plant-based patterns. |

| Unsaturated Fats | Positive [7] | Particularly associated with surviving to age 70 and intact physical/cognitive function [7]. |

| Low-Fat Dairy | Positive [7] | Provides high-quality protein and bone-supporting nutrients [20]. |

| Red and Processed Meats | Negative [7] | Associated with lower odds of healthy aging. |

| Sugary Beverages | Negative [7] | Associated with lower odds of healthy aging. |

| Sodium | Negative [7] | Associated with lower odds of healthy aging. |

| Trans Fats | Negative [7] | Associated with lower odds of healthy aging. |

| Ultra-Processed Foods | Negative [17] | Especially processed meats and sugary beverages. |

| Artificial Sweeteners | Negative (Cognitive) [21] | Associated with faster global cognitive decline (equivalent to 1.6 years of brain aging) [21]. |

Experimental Protocols and Key Methodologies

Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Studies

The primary evidence linking diet to multidimensional health originates from large, long-term prospective cohorts.

- Study Population: The 2025 Nature Medicine analysis pooled data from 70,091 women in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and 34,924 men in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) [7]. Participants were aged 39-69 at baseline and free of major chronic diseases.

- Dietary Assessment: Dietary intake was assessed every 2 to 4 years using validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQs). Adherence to the eight dietary patterns was calculated using cumulative average scores from all available FFQs to represent long-term dietary intake [7] [17].

- Outcome Assessment: Healthy aging was assessed at the end of the 30-year follow-up (2016) and defined multidimensionally. Specific criteria included:

- Freedom from 11 major chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, diabetes, myocardial infarction).

- Intact cognitive function,

- Intact physical function,

- Intact mental health [7].

- Statistical Analysis: Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for healthy aging were calculated comparing quintiles of dietary pattern scores using logistic regression models. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors (smoking, physical activity), body mass index, and multivitamin use [7].

Randomized Controlled Trials: The POINTER Study

The POINTER study (U.S. Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk) is a key RCT providing Level I evidence for lifestyle intervention [22].

- Population: 2,100 sedentary individuals aged 60-79 who had normal cognition but elevated risk for cognitive decline (due to suboptimal diet and sedentary lifestyle) [22].

- Intervention Protocol: A two-year, intensive, highly structured program:

- Aerobic Exercise: At least four times per week.

- Diet: Adherence to a heart-healthy Mediterranean-style diet.

- Cognitive Training: Online brain exercises.

- Social Activities: Mandatory participation.

- Health Monitoring: Regular tracking of blood pressure and blood sugar [22].

- Control Group: Participants were asked to develop their own plan for improving diet and exercise.

- Outcomes: The intensive intervention group showed significantly greater improvement in memory and thinking tests compared to the control group, effectively reducing their "brain age" by 1-2 years [22].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Dietary patterns influence aging trajectories through complex molecular mechanisms. The following diagram synthesizes key pathways described in the research.

Figure 1: Dietary Modulation of Aging Pathways

Key Mechanistic Insights

- Gut-Brain Axis and Microbiome: The gut microbiome evolves with age and diet. A diverse microbiome, supported by a variety of plant-based and fermented foods, enhances immune resilience, reduces inflammation, and is linked to better cognitive function. Conversely, ultra-processed foods disrupt microbial balance [16] [20]. Yogurt consumption has been associated with a reduced risk of dementia in observational studies [20].

- Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Pro-inflammatory diets (high in red meat, refined carbs, saturated fats) elevate systemic inflammation, accelerating cellular aging. Anti-inflammatory patterns (rich in polyphenols, omega-3s) counteract this. For instance, increased consumption of dairy may boost brain glutathione, an antioxidant that reduces oxidative stress [16] [20].

- Nutrient-Sensing Pathways: Bioactive compounds from food modulate key aging pathways. For example, plant-based compounds can inhibit the mTOR pathway, while nutrients like polyphenols can activate sirtuins, both of which are involved in cellular repair and longevity [16].

- Epigenetic Regulation: Diet can influence biological aging as measured by epigenetic clocks. Nutrients like vitamin D3 act as immunomodulators and can impact DNA methylation patterns, potentially slowing the epigenetic aging process [16].

This section details key reagents, datasets, and tools for investigating diet and healthy aging.

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Diet-Aging Studies

| Resource/Tool | Function/Application | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assesses long-term dietary intake and adherence to dietary patterns. | Used in NHS/HPFS to calculate scores for AHEI, MIND, etc. [7] [17]. |

| Validated Cognitive Batteries | Quantifies cognitive domains (memory, executive function, verbal fluency). | Montreal Cognitive Assessment, CERAD tests used in MIND diet studies [19] [21]. |

| Epigenetic Clocks | Measures biological age from DNA methylation patterns. | GrimAge (predicts mortality), PhenoAge (assesses disease risk) [16]. |

| Biobanks with Dietary Data | Links biological samples (blood, DNA) with dietary and health data for multi-omics research. | All of Us Research Program, Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health [23] [21]. |

| Precision Nutrition Algorithms | Predicts individual responses to food using AI and microbiome data. | Developed in the All of Us program to personalize dietary recommendations [23]. |

Discussion and Future Research Directions

The evidence demonstrates that dietary patterns, particularly the AHEI, DASH, and MIND diets, are robustly associated with multidomain healthy aging. These associations are biologically plausible, supported by mechanistic studies on inflammation, gut microbiome, and epigenetic regulation.

Future research must address critical gaps. First, findings from cohorts of health professionals need replication in more diverse socioeconomic and ancestral populations [7] [17]. Disparities exist, as evidenced by a study on SNAP benefits, where the protective effect on cognitive decline was stronger for non-Hispanic White participants compared to Black and Hispanic participants [24]. Second, while observational data is compelling, more large-scale, long-term RCTs like POINTER are needed to establish causality [22]. Third, the field of precision nutrition is nascent. Initiatives like the All of Us Research Program are building datasets to develop algorithms that predict individual responses to food, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach [23]. Finally, exploring Nutrition Dark Matter—the vast array of food-derived small molecules with unknown biological functions—represents a frontier for discovering novel bioactive compounds that modulate aging [16].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this body of evidence highlights that dietary interventions are a powerful, multi-mechanistic tool for preventing chronic disease and preserving functional capacity. Nutritional biochemistry provides a rich source of molecular targets for promoting healthspan, underscoring the need to integrate nutritional science into the broader framework of chronic disease research.

The escalating global burden of chronic diseases—including cardiovascular diseases (CVD), type 2 diabetes (T2DM), cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders—is inextricably linked to evolutionary shifts in dietary patterns. Modern diets have diverged significantly from ancestral patterns, characterized by increased consumption of saturated fats, ultra-processed foods (UPFs), and refined carbohydrates, alongside decreased intake of whole plant foods and unsaturated fats. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence from clinical, epidemiological, and mechanistic studies to elucidate the specific roles of protective dietary components—namely, plant-derived bioactive compounds and unsaturated fatty acids—and the distinct dangers posed by ultra-processing. The analysis is framed within the context of dietary pattern research for chronic disease prevention, providing a scientific foundation for therapeutic development and public health guidance.

Protective Effects of Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds

Classification and Molecular Diversity

Phytochemicals are bioactive compounds synthesized by plants, which play crucial roles in their defense systems and impart significant health benefits when consumed by humans. These compounds are broadly categorized based on their chemical structures and biological functions [25]. The major classes, their common representatives, and dietary sources are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Major Classes of Dietary Phytochemicals, Sources, and Primary Bioactivities

| Phytochemical Category | Common Phytochemicals | Primary Dietary Sources | Documented Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | Beta-carotene, Lycopene, Lutein | Carrots, tomatoes, watermelon, kale, spinach, corn [25] | Antioxidant, vision health, immune support, prostate & cardiovascular health [25] |

| Flavonoids | Quercetin, Catechins, Anthocyanins | Apples, onions, green tea, cocoa, blueberries, blackberries [25] | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, cardiovascular health, weight management [25] [26] |

| Phenolic Acids | Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid | Coffee, berries, whole grains, oats, rice, citrus fruits [25] | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular health, skin health [25] |

| Glucosinolates | Sulforaphane, Indole-3-carbinol | Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, kale [25] | Detoxification, anti-carcinogenic, hormone regulation, antioxidant [25] |

Mechanisms of Action: Molecular Pathways and Signaling Networks

The protective effects of phytochemicals are mediated through the modulation of key cellular signaling pathways involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and carcinogenesis [25] [26].

- Modulation of Inflammatory Pathways: Chronic inflammation, driven by the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and sustained activation of inflammatory signaling pathways, is a cornerstone of many chronic diseases [26]. Phytochemicals such as curcumin, resveratrol, and quercetin exert anti-inflammatory effects primarily by inhibiting the Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NF-κB) and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways [26]. This inhibition suppresses the expression of cytokines, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).

- Alleviation of Oxidative Stress: Phytochemicals combat oxidative stress through direct free radical scavenging and by upregulating endogenous antioxidant defense systems. Key mechanisms include the activation of the Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) pathway, which promotes the transcription of antioxidant enzymes like catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase [26]. For instance, resveratrol and quercetin have been shown to enhance catalase activity via Nrf2 activation [26].

- Anti-Carcinogenic Actions: Beyond antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, phytochemicals like sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables can modulate phase I and II detoxification enzymes, promote apoptosis in cancerous cells, and arrest cell cycle progression [25].

- Interaction with Gut Microbiota: Many phytochemicals are metabolized by the gut microbiota into more bioactive forms. This interaction can modulate the microbial composition, leading to increased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which exert systemic anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [26].

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular mechanisms through which plant-derived compounds like curcumin and resveratrol exert their protective effects.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Bioactivity

Protocol 1: Evaluating Anti-Inflammatory Activity In Vitro

- Objective: To quantify the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release in a macrophage cell model (e.g., RAW 264.7 cells) [26].

- Methodology:

- Cell Treatment: Pre-treat cells with varying concentrations of the phytochemical extract (e.g., quercetin) or vehicle control for 2 hours.

- Inflammation Induction: Stimulate inflammation by adding lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (e.g., 100 ng/mL) to the culture medium for 18-24 hours.

- Sample Collection: Collect cell culture supernatant by centrifugation.

- Cytokine Measurement: Quantify levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the supernatant using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to manufacturer protocols.

- Viability Assay: Perform a parallel MTT assay to ensure observed effects are not due to cytotoxicity.

- Data Analysis: Express cytokine levels as mean ± SEM. Use one-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests to compare treatment groups against the LPS-only control.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Antioxidant Pathway Activation

- Objective: To measure the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and subsequent upregulation of target genes [26].

- Methodology:

- Cell Treatment and Fractionation: Treat HepG2 or similar cells with the test compound. Harvest cells and separate nuclear and cytosolic fractions using a commercial kit.

- Western Blotting: Resolve proteins from each fraction by SDS-PAGE. Transfer to a membrane and probe with primary antibodies against Nrf2 and a loading control (e.g., Lamin B1 for nuclear, β-actin for cytosolic fractions).

- qRT-PCR: Extract total RNA from treated cells. Synthesize cDNA and perform quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using primers for Nrf2 target genes (e.g., HMOX1, NQO1, Catalase).

- Data Analysis: Quantify band density from Western blots to calculate nuclear-to-cytosolic Nrf2 ratio. Analyze qRT-PCR data using the 2^–ΔΔCt method to determine fold changes in gene expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Phytochemical Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A potent inflammatory agent used to induce a robust inflammatory response in cell models (e.g., macrophages) for screening anti-inflammatory compounds [26]. |

| ELISA Kits (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) | Used for the specific, sensitive, and quantitative measurement of cytokine levels in cell culture supernatants, serum, or other biological fluids [26]. |

| Nrf2 Antibodies | Essential for detecting Nrf2 protein levels and tracking its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus via Western blotting or immunofluorescence [26]. |

| qRT-PCR Primers (HMOX1, NQO1) | Used to measure the mRNA expression levels of key antioxidant genes that are downstream targets of the Nrf2 pathway, confirming pathway activation [26]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green, efficient, and tunable solvents used in modern extraction techniques to isolate phytochemicals from plant matrices with high yield and minimal degradation [25]. |

| Harpagide | Harpagide, CAS:6926-08-5, MF:C15H24O10, MW:364.34 g/mol |

| 5-Hydroxyflavone | 5-Hydroxyflavone (CAS 491-78-1) For Research |

Unsaturated Fats and Seed Oils: Evidence-Based Analysis

Composition and Nutritional Profile

Seed oils, also termed vegetable oils, are extracted from plant seeds and are characterized by a high content of unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) and relatively low levels of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) [27] [28]. They are primary dietary sources of the essential polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) linoleic acid (LA), an omega-6 fatty acid, and some, like canola oil, also provide significant omega-3 alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) [29] [27]. The fatty acid composition of common oils is detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: Fatty Acid Composition of Common Plant Oils (g/100g) [27]

| Oil | Total Polyunsaturated | Linoleic Acid (LA) | Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA) | Monounsaturated | Saturated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grapeseed | 69.9 | 69.6 | 0.1 | 16.1 | 9.6 |

| Soybean | 57.7 | 51.0 | 6.8 | 22.8 | 15.6 |

| Corn | 54.7 | 53.5 | 1.2 | 27.6 | 12.9 |

| Sunflower (Mid-oleic) | 29.0 | 28.9 | <0.1 | 57.3 | 9.0 |

| Canola | 28.1 | 19.0 | 9.1 | 63.3 | 7.4 |

| Olive | 10.5 | 9.8 | 0.9 | 73.0 | 13.8 |

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits: Clinical Evidence

Decades of epidemiological and clinical research consistently demonstrate the cardioprotective effects of replacing SFAs with PUFAs.

- Lipid Profile Improvement: A robust body of evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) shows that replacing saturated fats (e.g., butter, lard) with unsaturated fats from seed oils significantly lowers low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), a primary atherogenic risk factor [29] [27] [30]. This is one of the most well-established relationships in nutritional science.

- Reduction in Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Large-scale meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies show that higher LA intake and higher circulating levels of LA are associated with a lower risk of CVD, heart attack, and stroke [29] [27]. A 2019 study measuring LA in blood and adipose tissue of over 68,000 participants found that those with the highest levels had the lowest risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality [29].

- Type 2 Diabetes Risk Reduction: Research indicates that LA can improve glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. In the same large cohort study, participants with the highest levels of LA had a 35% lower risk of developing T2DM compared to those with the lowest levels [29].

Addressing Controversies: Inflammation and Oxidation

Despite the evidence, misconceptions persist regarding the role of seed oils and omega-6 fats in promoting inflammation and oxidative stress.

- The Inflammation Misconception: A common claim is that omega-6 LA is pro-inflammatory. However, systematic reviews of RCTs have consistently demonstrated that higher intake of LA does not increase biomarkers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP) [27] [28] [30]. While omega-3s may have stronger anti-inflammatory effects, omega-6s do not promote inflammation in typical dietary amounts [29] [30].

- The Omega-6 to Omega-3 Ratio: The focus on achieving a specific dietary ratio (e.g., 1:1) is misguided [29]. Evidence indicates that the beneficial association between LA and cardiovascular risk is independent of omega-3 levels. Recommendations should focus on increasing omega-3 intake (e.g., from fatty fish, walnuts, canola oil) rather than reducing beneficial omega-6 intake [29].

- Oxidative Stability: Concerns that PUFAs are prone to oxidation and promote oxidative stress in vivo are not supported by clinical evidence. RCTs show that high-PUFA diets do not adversely affect markers of oxidative stress [27].

The following diagram summarizes the evidence-based health impacts of replacing saturated fats with unsaturated seed oils.

Experimental Protocol: Randomized Controlled Trial on Lipid Outcomes

Protocol: RCT on Replacing SFA with UFA and Lipid Profile Changes

- Objective: To determine the effects of replacing dietary saturated fats with unsaturated seed oils on the lipid profiles of adults with elevated LDL-C.

- Study Design: Parallel-group, randomized, controlled feeding trial.

- Participants: ~100 adults, 30-65 years, with LDL-C > 130 mg/dL.

- Intervention:

- Run-in Period: 2-week standardized diet (typical American fat composition).

- Randomization: Participants randomly assigned to one of two isoenergetic diets for 8 weeks:

- SFA Diet: ~14% of total calories from SFA (using butter, cream, palm oil).

- UFA Diet: ~14% of total calories from UFA, primarily LA (using soybean and corn oil).

- Data Collection:

- Blood Sampling: Fasting blood draws at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks.

- Primary Outcome: Change in LDL-C concentration.

- Secondary Outcomes: Changes in HDL-C, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and oxidized LDL.

- Compliance Monitoring: Provided meals, diet diaries, and biomarker tracking (e.g., plasma fatty acid composition).

- Statistical Analysis: Intention-to-treat analysis using linear mixed-models to compare changes in outcomes between groups over time, adjusting for baseline values.

The Dangers of Ultra-Processed Foods

Defining Ultra-Processed Foods and Consumption Trends

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are formulations of industrial ingredients, often containing little or no whole food. They are typically created through a series of industrial processes and frequently include additives like emulsifiers, sweeteners, artificial colors, and flavors not found in home kitchens [31] [32]. According to the NOVA classification system, this category includes soft drinks, packaged snacks, sweetened cereals, mass-produced breads, and reconstituted meat products [31]. UPFs are rapidly displacing fresh foods in diets globally; in the UK and US, they comprise over half of the average calorie intake, and this proportion is even higher among younger, poorer, or disadvantaged populations [31].

Epidemiological Evidence Linking UPFs to Harm

The world's largest scientific review, encompassing 104 long-term studies, has found that UPFs are linked to harm in every major organ system of the human body and are associated with an increased risk of a dozen health conditions [31]. Key findings from recent studies are consolidated in Table 4.

Table 4: Documented Health Risks Associated with High Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods

| Health Outcome | Key Findings from Epidemiological Studies |

|---|---|

| All-Cause Mortality | Diets high in UPFs are associated with a higher risk of early death from all causes [31]. |

| Cardiometabolic Health | High UPF consumption is linked to significantly higher BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, insulin levels, and blood triglyceride levels [33]. It is associated with increased risk of CVD and T2DM [31]. |

| Mental & Brain Health | A positive association has been found between UPF intake and depression [31]. |

| Systemic Inflammation | A strong link exists between UPF consumption and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), a key marker of systemic inflammation [33]. |

Proposed Mechanisms of Harm

The detrimental health effects of UPFs are attributed to a combination of factors:

- Poor Nutritional Profile: UPFs are often high in added sugars, sodium, and unhealthy fats while being low in fiber, vitamins, and minerals [33] [31].

- Hyperpalatability and Overconsumption: Their engineered texture and flavor profile make it difficult to practice dietary moderation, leading to passive overconsumption of calories [32].

- Structural and Formulation Issues: The physical structure (e.g., lack of matrix) and specific industrial ingredients may affect satiety signaling, gut microbiota composition, and metabolic health in ways not fully explained by nutrient content alone [31].

- Displacement of Whole Foods: A primary danger is that UPFs displace fresh, minimally processed foods and traditional meals, reducing the intake of protective phytochemicals and nutrients [29] [31].

The Critical Distinction: Seed Oils vs. Ultra-Processed Foods

A critical point of confusion in public discourse is the conflation of seed oils themselves with the UPFs they are often contained within. The evidence indicates that the harm stems from the ultra-processed food matrix, not the seed oil per se [29] [30].

- Seed Oils as an Ingredient: Seed oils are used in UPFs because they are affordable, shelf-stable, and have a neutral flavor. Their presence is correlated with, but not the cause of, the poor health outcomes linked to UPFs [29].

- Attributing Harm Correctly: As stated by researchers, the harms of ultra-processed foods "have more to do with their calories and their high amounts of added sugar, sodium, and saturated fat than with seed oil" [30]. The public health recommendation is to "consider eating less ultraprocessed food and more whole foods, fruit, and vegetables—and then use seed oils together with those" [29].

The evidence is clear: dietary patterns rich in whole plant foods (with their diverse portfolio of bioactive phytochemicals) and unsaturated fats (from seed oils and other plant sources) are protective against chronic diseases. Conversely, diets high in ultra-processed foods pose a significant threat to global health. The mechanisms—ranging from molecular pathway modulation by phytochemicals to lipid profile improvement by unsaturated fats and the multifactorial harm from UPFs—provide a robust scientific basis for drug discovery and public health policy.

Future research should focus on:

- Elucidating UPF Mechanisms: Conducting controlled trials to disentangle the specific mechanisms by which UPFs cause harm, beyond their nutrient composition [31] [32].

- Personalized Nutrition: Exploring how genetic variation and individual gut microbiota profiles influence responses to specific phytochemicals and dietary fats [25].

- Technological Innovation: Developing advanced delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles, liposomes) to overcome the bioavailability challenges of many beneficial phytochemicals [25] [34].

- Policy-Relevant Studies: Generating more data on the impact of UPFs on children and US populations specifically, to inform targeted dietary guidelines and regulatory actions, such as front-of-pack labeling and marketing restrictions [32].

Bridging the gap between this compelling scientific evidence and the development of effective clinical interventions and public health policies remains a paramount challenge and opportunity for researchers, clinicians, and drug development professionals.

Dietary Patterns as a Systems Approach to Understanding Chronic Disease Etiology

The escalating global burden of chronic diseases necessitates a paradigm shift from a reductionist focus on single nutrients to a holistic systems approach centered on dietary patterns. This whitepaper elucidates how dietary pattern analysis provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex, multifactorial etiology of chronic diseases. We detail the methodological underpinnings for deriving and evaluating dietary patterns, present robust epidemiological evidence linking these patterns to diverse health outcomes, and provide standardized experimental protocols for implementation in research settings. By synthesizing current evidence and methodologies, this guide aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the tools necessary to advance the field of nutritional systems biology and develop effective, evidence-based dietary interventions for chronic disease prevention and management.

Over the past century, chronic diseases have superseded infectious diseases as the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in the United States and globally [35]. The etiology of chronic diseases is profoundly complex and multifactorial, involving interactions between age, genetic predisposition, lifestyle factors, and diet [35]. While traditional nutritional epidemiology often focused on individual nutrients or foods, a growing consensus recognizes that this reductionist approach is insufficient for capturing the intricate synergies, antagonisms, and cumulative effects of the diet as a whole [36]. Isolating single components is difficult because typical diets consist of complex mixtures of foods where increased consumption of some items leads to decreased consumption of others, creating substitution effects and multicollinearity that complicate statistical inference [36].

Dietary pattern analysis has emerged as a powerful complementary methodology that addresses these limitations by examining the entire dietary landscape. Dietary patterns are defined as "the quantities, proportions, variety or combination of different foods, drinks, and nutrients in diets and the frequency with which they are consumed" [35]. This systems approach offers several distinct advantages: it reflects actual dietary habits, accounts for complex interactions among food components, provides more stable exposure measures over time than individual nutrients, and offers more practical guidance for public health interventions [36]. The transition toward dietary patterns represents an evolution in nutritional science, aligning with the understanding that health outcomes result from the integrated effects of countless dietary constituents consumed in combination over a lifetime.

Methodological Framework for Dietary Pattern Analysis

Dietary Assessment Methods

Accurate assessment of dietary intake is foundational to dietary pattern research. The choice of assessment tool depends on the research question, study design, sample characteristics, and required precision [37]. The most common methods are compared in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Comparison of Dietary Assessment Methods

| Method | Scope of Interest | Time Frame | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Total diet | Short-term (previous 24 hours) | Does not require literacy; reduces reactivity; captures wide variety of foods | Relies on memory; expensive; requires multiple administrations to estimate usual intake |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire | Total diet or specific components | Long-term (months to years) | Cost-effective for large samples; assesses habitual intake | Limited food list; imprecise portion size estimation; requires literacy |

| Food Record | Total diet | Short-term (typically 3-4 days) | Does not rely on memory; detailed quantitative data | High participant burden; reactivity; requires literate, motivated participants |

| Screening Tools | Specific components (e.g., fruits/vegetables) | Variable (often prior month/year) | Rapid; low participant burden; cost-effective | Limited scope; must be validated for specific populations |

All self-reported dietary assessment methods are subject to both random and systematic measurement error [37]. Recovery biomarkers (e.g., doubly labeled water for energy intake, urinary nitrogen for protein) provide objective validation, though they exist for only a limited number of dietary components [37]. Emerging technologies including digital and mobile assessment tools are helping to reduce some limitations of traditional methods.

Analytical Approaches for Deriving Dietary Patterns

Statistical methods for deriving dietary patterns fall into three primary categories: investigator-driven (a priori), data-driven (a posteriori), and hybrid methods [36]. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the research question, with each approach offering distinct advantages and limitations.

Diagram 1: Dietary Pattern Analysis Workflow

Investigator-Driven (A Priori) Methods

Investigator-driven methods evaluate adherence to pre-defined dietary patterns based on existing nutritional knowledge or dietary guidelines [36]. These methods use scoring systems where points are awarded for consumption of recommended foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, whole grains) and deducted for less healthful options (e.g., foods high in saturated fat, sodium, or added sugars) [35]. Commonly used indices include:

- Healthy Eating Index (HEI): Measures alignment with the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans [35]

- Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH): Based on the diet used in the DASH clinical trials [35]

- Alternate Mediterranean Diet (AMED) Score: Assesses adherence to the traditional Mediterranean dietary pattern [14]

- Plant-based Diet Indices: Include the Healthful Plant-based Diet Index (hPDI) and Unhealthful Plant-based Diet Index (uPDI), which distinguish between quality of plant foods [36]

The primary advantage of a priori methods is their foundation in scientific evidence and dietary recommendations, facilitating comparisons across studies and direct links to policy [35]. Limitations include potential subjectivity in score construction and their focus on selected dietary aspects rather than the overall diet [36].

Data-Driven (A Posteriori) Methods

Data-driven methods derive dietary patterns empirically from consumption data without pre-defined hypotheses [36]. Principal techniques include:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Factor Analysis (FA): These correlated data reduction techniques identify common underlying factors (dietary patterns) based on the correlations between food groups [36]. PCA transforms correlated variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components that explain maximum variance, while FA decomposes food groups into common and unique factors [36].

- Cluster Analysis: Classifies individuals into mutually exclusive groups with similar dietary habits [36]. Traditional cluster analysis uses algorithms like k-means clustering, while finite mixture models provide a model-based probabilistic approach [36].

These methods capture actual eating habits in a population but may yield patterns that are population-specific and not easily comparable across studies [35].

Hybrid Methods

Hybrid methods incorporate elements of both a priori and a posteriori approaches by using health outcome data to inform pattern derivation [36]. Key methods include:

- Reduced Rank Regression (RRR): Identifies dietary patterns that explain the maximum variation in predetermined response variables (often nutritional biomarkers or disease intermediates) [36]

- Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO): A penalized regression approach that performs variable selection to identify foods most predictive of a health outcome [36]

These methods offer a direct pathway to understanding diet-disease relationships but may overlook patterns relevant to other health outcomes [36].

Evidence Linking Dietary Patterns to Chronic Disease Risk

Prospective cohort studies provide the strongest evidence for associations between dietary patterns and chronic disease incidence, as they assess diet at baseline in healthy participants and follow them over time for disease development, establishing temporality [35]. Table 2 summarizes key findings from large-scale epidemiological studies.

Table 2: Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Risk: Evidence from Prospective Studies

| Dietary Pattern | Cardiometabolic Disorders | Cancers | Psychological/ Neurological Disorders | Digestive Disorders | Other Chronic Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternate Mediterranean Diet | Reduced risk of all 8 CMDs studied [14] | Reduced risk of lung, esophageal, and other cancers [14] | Reduced risk of dementia, Parkinson's, depression, anxiety, epilepsy [14] | Reduced risk of dyspepsia, constipation, diverticular disease, IBS, chronic liver disease [14] | Reduced risk of COPD, CKD, asthma, bronchiectasis, cataract [14] |

| AHEI-2010 | Reduced risk of CVD, hypertension; association with diabetes attenuated by BMI adjustment [14] | Reduced risk of non-melanoma skin, lung, breast, and other cancers [14] | Reduced risk of dementia, depression, epilepsy; strongest protective effect for substance abuse [14] | Reduced risk of all digestive disorders studied [14] | Reduced risk of COPD, CKD, prostate disorders [14] |

| Healthful Plant-based Diet Index | Reduced risk of 5 CMDs [14] | Reduced risk of colon, ovarian, and other cancers [14] | Reduced risk of depression and epilepsy [14] | Reduced risk of all digestive disorders studied [14] | Reduced risk of COPD, CKD, prostate disorders [14] |

| DASH Diet | Lower risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes [35] | Evidence for some cancer risk reduction [35] | Emerging evidence for neurological benefits | Limited evidence | Limited evidence |

The preponderance of evidence indicates that healthy dietary patterns—generally characterized by higher intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low and non-fat dairy, and lean protein, and lower in saturated fat, trans fat, sodium, and added sugars—reduce the risk of major chronic diseases [35]. A comprehensive study of 121,513 UK Biobank participants found the Alternate Mediterranean Diet score was inversely associated with 32 of 48 individual chronic diseases studied, spanning cardiometabolic, cancer, neurological, digestive, and other conditions [14].

The mechanisms underlying these protective effects are multifactorial and likely involve synergistic interactions between dietary components that reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysregulation while promoting healthy gut microbiota and cellular function [14]. This systems-level impact explains why dietary patterns demonstrate broader health benefits than individual dietary components.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Standardized Protocol for Dietary Pattern Analysis in Cohort Studies

Objective: To investigate associations between dietary patterns and chronic disease incidence in a prospective cohort design.

Study Design: Prospective cohort study with baseline dietary assessment and follow-up for disease endpoints.

Participants: Community-dwelling adults free of the chronic disease outcomes of interest at baseline.

Duration: Minimum 5-year follow-up (varies by outcome incidence).

Procedure:

- Dietary Assessment: Administer validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) at baseline. The FFQ should assess usual frequency and portion size of 100-150 food items over the previous year.

- Covariate Assessment: Collect comprehensive data on potential confounders including age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, education level, socioeconomic status, and medical history.

- Follow-up and Endpoint Ascertainment: Follow participants for disease outcomes via linkage to health records, registries, or repeated assessments. Use standardized diagnostic criteria for endpoint verification.

- Data Analysis:

- Derive dietary patterns using pre-defined scoring systems (e.g., AMED, AHEI-2010) or data-driven methods (e.g., PCA)

- Use Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for associations between dietary patterns (analyzed as quintiles or per-quintile increment) and disease outcomes

- Adjust models for potential confounders identified in step 2

- Conduct sensitivity analyses to test robustness of findings

Quality Control:

- Validate FFQ against multiple 24-hour recalls or recovery biomarkers in a subset

- Implement blinding of outcome assessors where possible

- Account for multiple testing using false discovery rate methods [14]

Diagram 2: Cohort Study Design for Dietary Pattern Research

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Dietary Pattern Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Platforms | Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Recall (ASA-24); Food Frequency Questionnaires | Standardized collection of dietary intake data with nutrient calculation capabilities |

| Biomarker Assays | Doubly labeled water (energy expenditure); Urinary nitrogen (protein intake); Plasma carotenoids (fruit/vegetable intake); Serum fatty acids (dietary fat quality) | Objective validation of dietary intake and pattern adherence; measures not reliant on self-report |

| Statistical Software Packages | SAS (PROC FACTOR, PROC PHREG); R (psych, FactoMineR, survival, glmnet); STATA (factor, scoreplot) | Implementation of dietary pattern derivation and association analyses with appropriate statistical methods |

| Dietary Pattern Scoring Algorithms | HEI-2020 Scoring Algorithm; AHEI Scoring System; MEDAS (Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener) | Standardized calculation of a priori dietary pattern scores for consistent application across studies |

| Data Linkage Systems | Cancer registries; Hospitalization databases; Mortality registries; Pharmacy claims | Objective endpoint ascertainment for prospective studies with long follow-up periods |

| Icariside Ii | Icariside Ii, CAS:113558-15-9, MF:C27H30O10, MW:514.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside |

Dietary pattern analysis represents a fundamental systems approach that aligns with the complex, multifactorial nature of chronic disease etiology. By examining the cumulative and interactive effects of overall diet, this methodology provides insights that cannot be captured by studying isolated nutrients or foods. The consistent inverse associations between healthy dietary patterns—particularly the Mediterranean-style, healthy plant-based, and DASH-style patterns—and a wide spectrum of chronic diseases underscore the translational potential of this approach for public health and clinical practice.

Future research should prioritize the standardization of dietary assessment and pattern derivation methods, investigation of molecular mechanisms underlying observed associations, and development of personalized dietary recommendations based on individual characteristics and genetic predispositions. As the field evolves, dietary pattern analysis will continue to be an indispensable tool for unraveling the complex relationships between diet and health, ultimately informing more effective strategies for chronic disease prevention and management.

From Data to Diets: Analytical Frameworks, Biomarker Discovery, and Guideline Translation

Accurately assessing dietary adherence is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology, providing the critical link between dietary patterns and chronic disease risk in research. The shift from analyzing single nutrients to evaluating whole diets reflects the understanding that foods and nutrients are consumed in complex combinations, exerting synergistic effects on health [36] [38]. Dietary patterns are more consistent over time and often have a greater impact on health outcomes than individual nutrients [36]. This technical guide details the core methodologies—dietary indices, Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), and scoring systems—used to quantify adherence to defined dietary patterns, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the protocols and tools necessary for rigorous investigation.

Methodological Approaches to Dietary Pattern Analysis

Dietary pattern analysis methodologies are broadly categorized into three approaches, each with distinct rationales and applications in chronic disease research [36] [38].

- Hypothesis-Driven (A Priori) Methods: These approaches test adherence to pre-defined dietary patterns based on existing scientific knowledge and dietary guidelines. They utilize dietary indices and scores, such as the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) or the Mediterranean Diet Score (MED), to assess diet quality [36] [38].

- Exploratory (A Posteriori) Methods: These data-driven approaches, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Cluster Analysis, derive dietary patterns solely from the ingested dietary data without relying on prior hypotheses. They are useful for identifying prevailing eating habits within study populations [36] [38].

- Hybrid Methods: Techniques like Reduced Rank Regression (RRR) combine aspects of both a priori and a posteriori methods. They use prior knowledge about the diet-disease pathway (e.g., through biomarkers) to guide the derivation of dietary patterns from consumption data [36] [38].

The following workflow outlines the strategic selection and application of these core methodologies for assessing dietary adherence in research.

Hypothesis-Driven Methods: Dietary Indices and Scores

Hypothesis-driven methods use dietary indices to score individuals based on their adherence to a predefined dietary pattern aligned with nutritional knowledge or guidelines linked to health outcomes [36] [38]. These scores measure the extent to which an individual's diet aligns with dietary recommendations.

Common Dietary Indices and Their Composition

The table below summarizes the rationale, components, and scoring systems of major dietary indices used in chronic disease research.

Table 1: Key Dietary Indices for Assessing Adherence to Health-Promoting Dietary Patterns

| Index Name | Rationale & Hypothesis | Core Dietary Components & Scoring System | Scoring Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Eating Index (HEI) [36] [38] | Adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. | Scores adequacy of total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens & beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein, seafood & plant proteins, and fatty acids ratio. Scores moderation for refined grains, sodium, added sugars, and saturated fats. | 0 - 100 |

| Mediterranean (MED) Diet Score [36] [38] | Adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet, associated with reduced chronic disease risk. | Awards points for high consumption of non-refined grains, vegetables, potatoes, fruits, legumes, nuts, fish, and olive oil. Awards points for moderate consumption of alcohol and low consumption of red meat, poultry, and full-fat dairy. | 0 - 55 |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) [36] [38] | Diet to prevent and treat high blood pressure. | Awards points for meeting recommended servings of total grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy, nuts/seeds/legumes. Awards points for limiting meat/poultry/fish, total fat, saturated fat, sweets, and sodium. | 0 - 10 |

| EAT-Lancet Consumption Frequency Index (ELFI) [39] | Adherence to the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet, promoting health and environmental sustainability. | Uses a brief food propensity questionnaire (FPQ) of 14 food groups. Yields two factors: "foods to encourage" and "foods to balance and to limit." | N/A (Relative Adherence) |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Dietary Index

Aim: To assess participant adherence to the Mediterranean diet and analyze its association with cardiovascular event incidence in a prospective cohort.

Materials & Methods:

- Study Population: Recruit from a well-characterized cohort (e.g., n > 5,000) with baseline health data and biobank samples.

- Dietary Assessment: Administer a validated, quantitative FFQ. The FFQ should include food items relevant to the Mediterranean diet (e.g., olive oil, fish, legumes, red meat) and capture portion sizes [40] [37].

- Scoring Calculation:

- For each dietary component in the MED Score (e.g., fruits, vegetables, red meat), calculate the participant's median daily intake from the FFQ data.

- Assign points for each component based on predefined sex-specific population cut-offs or recommended servings. For example, assign 0-5 points for beneficial components, where a higher intake yields a higher score, and reverse-score for harmful components (e.g., red meat) [36] [38].

- Sum all component scores to create a total MED diet score for each participant.