Machine Learning for Glycemic Response Prediction: From Algorithms to Clinical Applications in Diabetes Management

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of machine learning (ML) for predicting glycemic responses, a critical capability for personalized diabetes care.

Machine Learning for Glycemic Response Prediction: From Algorithms to Clinical Applications in Diabetes Management

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of machine learning (ML) for predicting glycemic responses, a critical capability for personalized diabetes care. We examine foundational concepts including key glycemic metrics like Time in Range (TIR), postprandial glycemic response (PPGR), and hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia prediction. The article details diverse methodological approaches, from ensemble methods like XGBoost to advanced deep learning architectures and multi-task learning frameworks, highlighting their applications in clinical scenarios such as hemodialysis management and automated insulin delivery. We address crucial optimization challenges including data limitations, model interpretability through SHAP and XAI, and generalization strategies like Sim2Real transfer. Finally, we evaluate validation frameworks, performance metrics, and comparative algorithm analyses, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous assessment of current capabilities and future directions for integrating ML into diabetes therapeutics and management systems.

Foundations of Glycemic Response Prediction: Key Metrics and Clinical Significance

In the era of data-driven medicine, the management of diabetes has been transformed by continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which provides a dynamic, high-resolution view of glucose fluctuations that traditional metrics like HbA1c cannot capture [1]. These advanced measurements form the critical foundation for developing machine learning (ML) algorithms aimed at predicting glycemic response and personalizing therapy. Where HbA1c offers a static, long-term average, CGM-derived metrics reveal the complex glycemic patterns throughout the day and night, exposing variability, hypoglycemic risk, and postprandial excursions [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core parameters—Time in Range (TIR), Time Above Range (TAR), Time Below Range (TBR), Coefficient of Variation (CV), and Postprandial Glucose Response (PPGR)—is essential for designing clinical trials, evaluating therapeutic interventions, and building robust predictive models [1] [3].

The international consensus on CGM metrics has standardized these parameters, enabling consistent application across clinical practice and research [1]. This standardization is particularly crucial for ML applications, as it ensures the generation of reliable, labeled datasets for model training. This document provides a detailed exploration of these metrics, their quantitative relationships, and their central role in modern glycemic research, with a specific focus on their application in machine learning algorithms for predicting glycemic responses.

Defining the Key Metrics and Their Interrelationships

Metric Definitions and Clinical Targets

The following table summarizes the definitions, targets, and clinical significance of the five core glycemic metrics, providing a concise reference for researchers.

Table 1: Core Glycemic Metrics: Definitions, Targets, and Clinical Relevance

| Metric | Definition | Primary Target | Clinical Relevance & Association with Complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Range (TIR) | Percentage of time glucose is between 70–180 mg/dL [1]. | ≥ 70% for most adults [1]. | Strongly associated with reduced risk of microvascular complications [1] [2]. |

| Time Above Range (TAR) | Percentage of time glucose is >180 mg/dL, with a subset >250 mg/dL [1]. | < 25% (>180 mg/dL), < 5% (>250 mg/dL) [1]. | Reflects hyperglycemia burden and long-term complication risk [1]. |

| Time Below Range (TBR) | Percentage of time glucose is <70 mg/dL, with a subset <54 mg/dL [1]. | < 4% (<70 mg/dL), < 1% (<54 mg/dL) [1]. | Key safety metric; measures hypoglycemia risk [1]. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Measure of glycemic variability: (Standard Deviation / Mean Glucose) × 100 [1]. | ≤ 36% [1]. | Predictor of hypoglycemia risk; higher CV indicates greater glucose instability [1] [4]. |

| Postprandial Glucose Response (PPGR) | Increase in blood glucose after meal consumption, often calculated as the incremental Area Under the Curve (AUC) in the 2-hour period after eating [3]. | N/A (Highly individualized) | Major driver of overall glycemic control and TAR; marked interindividual variability exists [3] [5]. |

Statistical and Mechanistic Relationships Between Metrics

The core glycemic metrics are not independent; they exist in a tightly coupled, and often inverse, relationship. Understanding these interrelationships is critical for both clinical interpretation and feature engineering in ML models.

- TIR, TAR, and TBR as a Closed System: By definition, TIR + TAR + TBR = 100% of a 24-hour period [1]. Consequently, an intervention that increases TIR will necessarily decrease TAR, TBR, or both. This inverse relationship is a fundamental constraint in any predictive system.

- The Critical Role of Glycemic Variability (CV): The CV is a powerful predictor of hypoglycemia. Research demonstrates a strong positive correlation between CV and TBR (r=0.708, p<0.0001), and specifically with time below 54 mg/dL (r=0.664, p<0.0001) [4]. A higher CV indicates greater glucose instability, which exponentially increases the risk of hypoglycemic events, even when mean glucose or HbA1c appears acceptable [6]. Conversely, CV shows a weak negative correlation with TIR (r=-0.398, p=0.003) and no significant correlation with TAR [4].

- PPGR as a Determinant of TAR: Elevated PPGR is a primary contributor to TAR. The postprandial state is a period of significant metabolic challenge, and the magnitude of the glucose excursion directly influences the number of hours spent above the 180 mg/dL threshold. Managing PPGR is therefore a key strategy for reducing TAR and increasing TIR [3].

Application in Machine Learning for Glycemic Response Prediction

The Role of Metrics in Model Development

In ML research for diabetes, glycemic metrics serve two primary functions: as model outputs/targets for prediction and as input features for personalized recommendations.

- TIR, TAR, and TBR as Prediction Targets: A key application of ML is forecasting future glycemic events. Studies have developed dual-prediction frameworks that simultaneously forecast postprandial hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia within a 4-hour window, using these metrics to define the prediction target [7]. The model's performance is then evaluated based on its ability to correctly classify these future events, with high AUC scores reported (0.84 for hypoglycemia and 0.93 for hyperglycemia) [7].

- CV and PPGR as Features for Personalization: The CV is a critical input feature for models assessing hypoglycemia risk due to its strong correlation with TBR [4] [6]. PPGR, given its significant interindividual variability, is a central outcome for personalized nutrition models. Research shows that predicting an individual's PPGR is feasible using machine learning that incorporates meal data, demographics, and other factors, achieving accuracy comparable to methods that rely on invasive data like microbiome analysis [5] [8].

A Protocol for Generating Machine Learning-Ready PPGR Data

The following protocol outlines a methodology for collecting high-quality, multi-modal data suitable for training ML models to predict PPGR, based on a contemporary research study [3].

Aim: To characterize interindividual variability in PPGR and identify factors associated with these differences for the creation of machine learning models. Population: Adults with Type 2 Diabetes (HbA1c ≥7%), treated with oral hypoglycemic agents. Duration: 14-day observational period. Primary Outcome: PPGR, calculated as the incremental AUC (iAUC) for the 2-hour period following each logged meal.

Table 2: Data Collection Protocol for PPGR Machine Learning Studies

| Data Domain | Specific Measures & Equipment | Collection Frequency & Protocol | Function in ML Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Metrics | CGM (e.g., Abbott Freestyle Libre) [3]. | Worn continuously for 14 days; minimum 70% data capture required [1] [3]. | Target Variable (PPGR); features for TIR, TAR, TBR, CV. |

| Dietary Intake | Detailed food diary (via study app or logbook); standardized test meals [3]. | All meals, snacks, beverages logged in real-time. Standardized meals consumed on specific days. | Primary Input Features (food categories, macronutrients). |

| Physical Activity | Heart rate monitor (e.g., Xiaomi Mi Band) [3]. | Worn continuously, including during sleep. | Input Feature (for energy expenditure estimation). |

| Medication | Oral hypoglycemic agent use [3]. | Logged with timing and dosage for each dose. | Input Feature (confounding variable adjustment). |

| Biometrics & Labs | Blood pressure, weight, height, HbA1c, blood lipids, etc. [3]. | Collected at in-person baseline visit. | Static Input Features (for personalization). |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes | WHO-5 Well-Being Index, Diabetes Distress Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [3]. | Completed at baseline. | Input Features (for psychological and sleep context). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Glycemic Response Studies

| Item | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Abbott Freestyle Libre [3]. | Provides continuous interstitial glucose measurements, the primary data source for calculating TIR, TAR, TBR, CV, and PPGR. |

| Activity & Physiological Monitor | Xiaomi Mi Band (or equivalent smart wristband) [3]. | Captures heart rate and physical activity data, used as features for ML models to account for exercise-induced glycemic changes. |

| Data Integration & Logging Platform | Custom study app on participant smartphone [3]. | Synchronizes CGM, activity data, and meal/medication logs into a unified dataset; critical for ensuring data completeness and temporal alignment. |

| Standardized Test Meals | Protocol-defined vegetarian meals [3]. | Used to elicit a controlled PPGR, reducing dietary noise and enabling direct comparison of metabolic responses across participants. |

| Glucose Simulator | Customized simulator based on the Dalla Man model [7]. | Enables in silico testing and validation of ML models and insulin adjustment algorithms in a controlled, risk-free virtual environment. |

| BIBU1361 | BIBU1361, CAS:793726-84-8, MF:C22H29Cl3FN7, MW:516.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kisspeptin-10, rat | Kisspeptin-10, rat, MF:C63H83N17O15, MW:1318.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The standardized glycemic metrics of TIR, TAR, TBR, CV, and PPGR provide an indispensable framework for moving beyond the limitations of HbA1c. For the research community, and particularly for scientists developing machine learning algorithms, these metrics offer quantifiable, physiologically meaningful targets for prediction and optimization. The strong statistical relationships between them, especially the role of CV in predicting hypoglycemia risk, must be baked into the structure of predictive models. The ongoing integration of explainable ML with high-resolution CGM data, detailed dietary information, and other contextual factors promises to unlock a new era of personalized diabetes management, enabling dynamic interventions that maximize TIR while minimizing the risks of hypo- and hyperglycemia.

Clinical Importance of Predicting Hypoglycemia and Hyperglycemia Events

The predictive capacity of machine learning (ML) for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia events represents a transformative advancement in diabetes management. For the millions of individuals living with diabetes worldwide, the threat of glycemic decompensation—blood glucose levels that fall too low (hypoglycemia) or rise too high (hyperglycemia)—presents a constant challenge with potentially severe health consequences [9] [10]. Both conditions have been associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare expenditures in hospital settings [10]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies enables a paradigm shift from reactive to proactive diabetes care, allowing for interventions before glucose levels reach dangerous thresholds [9] [11]. This application note details the clinical significance of glycemic event prediction and provides structured protocols for implementing ML approaches within glycemic response research.

Clinical Rationale and Impact

The Clinical Burden of Dysglycemia

Glycemic decompensations constitute a frequent and significant risk for inpatients and outpatients with diabetes, adversely affecting patient outcomes and safety [9]. Hypoglycemia can induce symptoms ranging from shakiness and confusion to seizures, loss of consciousness, and even death if untreated [12]. Hyperglycemia can cause fatigue, excessive urination, and thirst, progressing to more severe complications including diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state [9] [12]. In hospitalized patients, both conditions have been linked to increased length of stay, higher risk of infection, admission to intensive care units, and increased mortality [9] [10].

The management of dysglycemia poses substantial demands on healthcare systems. The increasing need for blood glucose management in inpatients places high demands on clinical staff and healthcare resources [9]. Furthermore, fear of exercise-induced hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia presents a significant barrier to regular physical activity in adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D), potentially compromising their overall cardiovascular health and quality of life [13].

The Predictive Approach: From Reaction to Prevention

Traditional diabetes management often involves reacting to glucose measurements after they have occurred. Predictive models shift this paradigm toward prevention by identifying at-risk periods before glucose levels become derailed. Research demonstrates that electronic health records and continuous glucose monitor (CGM) data can reliably predict blood glucose decompensation events with clinically relevant prediction horizons—7 hours for hypoglycemia and 4 hours for hyperglycemia in one inpatient study [9]. This advance warning system enables proactive interventions, such as carbohydrate consumption to prevent hypoglycemia or insulin adjustment to mitigate hyperglycemia, potentially reducing the detrimental health effects of both conditions [9].

Table 1: Clinical Consequences of Glycemic Dysregulation

| Condition | Definition | Short-term Consequences | Long-term Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia | Blood glucose <70 mg/dL (<3.9 mmol/L) [9] | Shakiness, confusion, tachycardia, seizures, unconsciousness [12] | Increased mortality, reduced awareness of symptoms [10] |

| Hyperglycemia | Blood glucose >180 mg/dL (>10 mmol/L) [9] | Fatigue, excessive thirst, frequent urination [12] | Diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar state, increased infection risk [9] [10] |

Machine Learning Approaches and Performance

Algorithm Diversity and Performance Metrics

Multiple machine learning architectures have been successfully applied to glycemic event prediction, ranging from traditional regression techniques to sophisticated deep learning frameworks. The selection of an appropriate model depends on the specific clinical context, available data types, and prediction horizon requirements.

For glucose forecasting and hypoglycemia detection, a domain-agnostic continual multi-task learning (DA-CMTL) framework has demonstrated robust performance, achieving a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 14.01 mg/dL, mean absolute error (MAE) of 10.03 mg/dL, and sensitivity/specificity of 92.13%/94.28% for 30-minute predictions [11]. This unified approach simultaneously performs glucose level forecasting and hypoglycemia event classification within a single architecture, enhancing coordination for real-time insulin delivery systems.

In exercise-specific contexts, models incorporating continuous glucose monitoring data alone have shown excellent predictive performance for glycemic events, with cross-validated area under the receiver operating curves (AUROCs) ranging from 0.880 to 0.992 for different glycemic thresholds [13]. This remarkable performance using a single data modality highlights the richness of information embedded in CGM temporal patterns.

For inpatient settings, a multiclass prediction model for blood glucose decompensation events achieved specificities of 93.7-98.9% and sensitivities of 59-67.1% for nondecompensated cases, hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia categories [9]. The high specificity is particularly valuable for minimizing false alarms that could lead to alert fatigue among clinical staff.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Selected Machine Learning Models for Glycemic Event Prediction

| Model Type | Population | Prediction Horizon | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain-Agnostic Continual Multi-Task Learning | Mixed T1D | 30 minutes | RMSE: 14.01 mg/dL; MAE: 10.03 mg/dL; Sensitivity/Specificity: 92.13%/94.28% | [11] |

| CGM-Based Exercise Event Prediction | T1D (during & post-exercise) | During and 1-hour post-exercise | AUROC: 0.880-0.992 (depending on glycemic threshold) | [13] |

| Gradient-Boosted Multiclass Prediction | Inpatients with diabetes | Median 7h (hypo), 4h (hyper) | Hypoglycemia: 67.1% sensitivity, 93.7% specificity; Hyperglycemia: 63.6% sensitivity, 93.9% specificity | [9] |

| Binary Decision Tree | General diabetes | Short-term prediction | 92.58% classification accuracy for glucose level categories | [12] |

Data Modalities and Feature Engineering

The predictive capacity of machine learning models for glycemic events depends heavily on the data modalities incorporated during training. Research indicates varying levels of contribution from different data types:

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring: CGM data provides the most powerful predictive signals for glycemic events, particularly for near-term predictions [13]. In exercise settings, models based solely on CGM data demonstrated statistically indistinguishable performance compared to models incorporating additional demographic, clinical, and exercise characteristics [13].

- Electronic Health Records: For inpatient populations, EHR data including laboratory results, medication administration, and diagnosis codes enables effective prediction of decompensation events [9] [10]. Derived variables from EHRs (mean, standard deviation, trends, and extreme values of laboratory analytes) effectively capture patient status for prediction.

- Food and Nutrition Data: Emerging evidence suggests that food category information may surpass macronutrient composition alone for predicting postprandial glycemic responses [5] [8]. Food categories potentially serve as proxies for micronutrients, processing levels, or physical properties that influence digestion and absorption.

- Contextual Factors: Menstrual cycle phases and time of day introduce significant variability in individual glycemic responses [5] [8]. Incorporating these temporal factors improves prediction accuracy by accounting for systematic patterns in insulin sensitivity fluctuations.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Predicting Postprandial Glycemic Responses in Type 2 Diabetes

Study Design: Prospective cohort study evaluating interindividual variability in postprandial glucose response (PPGR) among adults with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and suboptimal control (HbA1c ≥7%) [3].

Setting: 14 outpatient clinics across India with specialized diabetes care expertise [3].

Participant Criteria:

- Inclusion: Adults (18-75 years) with physician-diagnosed T2D treated with ≥1 oral hypoglycemic agents; HbA1c ≥7.0% within past 30 days; mobile phone capability with functional English literacy [3].

- Exclusion: Current prandial insulin use; pregnancy; estimated life expectancy ≤12 months; active cancer; myocardial infarction or stroke in previous 6 months; contraindications to CGM use [3].

Methodology:

- Baseline Assessment: Collect sociodemographic and medical information; administer standardized surveys (WHO STEPS, WHO-5 Well-Being Index, Diabetes Distress Scale, Wilson Adherence Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index); perform biometric measurements; obtain blood and urine samples for laboratory analysis [3].

- Monitoring Phase: Participants wear Abbott Freestyle Libre CGM sensor and Xiaomi Mi Band smart wristband for 14 days [3].

- Data Logging: Participants record all dietary intake (using study app or paper logbook), exercise activities, and medication use throughout the 14-day period [3].

- Standardized Meal Protocol: Participants consume protocol-specified vegetarian breakfast meals with variations in carbohydrate, fiber, protein, and fat composition on designated days [3].

- Primary Outcome: PPGR calculated as incremental area under the curve 2 hours after each logged meal [3].

Analytical Approach: Machine learning models will be created to predict individual PPGR responses and facilitate personalized diet prescriptions [3].

Protocol for Exercise-Induced Glycemic Event Prediction in Type 1 Diabetes

Study Design: Analysis of free-living data from the Type 1 Diabetes Exercise Initiative (T1DEXI) study, incorporating at-home exercise with detailed concurrent phenotyping [13].

Participant Profile: 329 adults with T1D; median age 34 years (IQR 26-48); 74.8% female; 94.5% White; 55.3% using closed-loop insulin delivery systems [13].

Intervention: Participants completed 6 structured exercise sessions (aerobic, interval, or resistance) over 4 weeks, each approximately 30 minutes with warm-up and cool-down periods, while maintaining typical daily physical activities [13].

Data Collection:

- CGM Data: Dexcom G6 sensors collecting glucose measurements every 5 minutes [13].

- Carbohydrate Intake: Collected through T1DEXI mobile application [13].

- Insulin Dosing: Extracted from insulin pumps [13].

- Exercise Characteristics: Type, duration, intensity, and time of day recorded [13].

- Demographic and Clinical Data: Self-reported via portal including diabetes history and most recent HbA1c [13].

Analysis Framework:

- Decision Points: Two critical prediction timepoints—(1) pre-exercise to assess risk during exercise; (2) post-exercise to assess risk 1-hour post-exercise [13].

- Prediction Targets: Four glycemic events—severe hypoglycemia (≤54 mg/dL), hypoglycemia (≤70 mg/dL), hyperglycemia (≥200 mg/dL), severe hyperglycemia (≥250 mg/dL)—assessed separately during and post-exercise [13].

- Model Evaluation: Repeated stratified nested cross-validation for model selection and performance estimation; assessment of input modality contributions; evaluation of model calibration and noise resilience [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Technologies for Glycemic Prediction Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Protocol Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitors | Abbott Freestyle Libre [3], Dexcom G6 [13] | Continuous measurement of interstitial glucose levels; primary data source for temporal glucose patterns | Used in both T1D and T2D protocols for real-world glucose monitoring [3] [13] |

| Activity Monitors | Xiaomi Mi Band Smart Wristband [3] | Heart rate monitoring and activity tracking; correlates physical exertion with glycemic variability | Protocol for assessing impact of exercise on glycemic responses [3] |

| Data Logging Platforms | Study-specific smartphone applications, Paper logbooks [3], T1DEXI app [13] | Capture participant-reported data on diet, medication, exercise; enables temporal alignment with CGM data | Dietary intake logging in free-living conditions [3] [13] |

| Standardized Meal Kits | Protocol-specified vegetarian breakfast meals with varying macronutrient composition [3] | Controls for nutritional input to assess interindividual variability in postprandial responses | Testing PPGR to standardized nutritional challenges [3] |

| Laboratory Analysis | HbA1c, complete blood count, blood electrolytes, creatinine, cholesterol, urinalysis [3] | Provides baseline metabolic status and inclusion criterion verification | Characterizing study population and ensuring eligibility [3] |

| Simulated Datasets | Physiologically validated diabetes simulators [11] | Generates synthetic patient data for initial model training; reduces reliance on real-world data collection | Sim2Real transfer learning in multi-task frameworks [11] |

| Epiequisetin | Epiequisetin, MF:C22H31NO4, MW:373.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Ivermectin monosaccharide | Ivermectin monosaccharide, MF:C41H62O11, MW:730.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Regulatory and Implementation Considerations

The development of ML-based technologies for glycemic prediction must align with established regulatory frameworks to ensure safety and efficacy. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada, and the United Kingdom's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency have identified ten guiding principles for Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) in medical device development [14]. These principles emphasize multi-disciplinary expertise throughout the product life cycle, representative training datasets, model design tailored to available data and intended use, and performance monitoring during clinically relevant conditions [14].

For clinical trial design incorporating AI and digital health technologies, the FDA emphasizes the importance of ensuring that decentralized clinical trials and digital health technologies are "fit for purpose" while considering the total context of the clinical trial, the intervention type, and the patient population involved [15]. Digital health technologies, including continuous glucose monitors and activity trackers, enable continuous or frequent measurements of clinical features that might not be captured during traditional study visits, thus providing more comprehensive data collection [15].

Ethical implementation of glycemic prediction algorithms requires attention to potential biases in training data, transparency in model performance limitations, and careful consideration of the clinical workflow integration to prevent alert fatigue. As these technologies evolve toward automated insulin delivery systems, robust safety frameworks and fail-safes become increasingly critical to prevent harm from prediction errors [11].

CONTINUOUS GLUCOSE MONITORING (CGM) AS A PRIMARY DATA SOURCE

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) provides a rich, high-frequency temporal data stream of subcutaneous interstitial glucose measurements, typically every 5 minutes, offering an unprecedented view into glycemic physiology [16]. For researchers developing machine learning (ML) algorithms to predict glycemic response, CGM data moves beyond the snapshot provided by HbA1c or self-monitored blood glucose to capture dynamic patterns, including glycemic variability, postprandial excursions, and nocturnal trends [17]. This data density and temporal resolution make CGM a foundational primary data source for training sophisticated models aimed at forecasting glucose levels, classifying hypoglycemic risk, and ultimately enabling personalized, proactive diabetes interventions [18] [16].

Data Sourcing and Selection Protocols

The selection of appropriate CGM datasets is a critical first step in building generalizable and robust predictive models. Research-grade and real-world CGM data each offer distinct advantages.

2.1 Research-Grade CGM Data Collection Protocol A standardized protocol for collecting research-grade CGM data ensures consistency and reliability for model training [18].

- Device and Placement: Use FDA-approved CGM systems (e.g., Medtronic Enlite Sensor with iPro2 recorder). Sensors are placed subcutaneously, typically in the abdominal region.

- Calibration: Per manufacturer guidelines, calibrate sensors against fingerstick blood glucose (BG) measurements using a Contour Next meter. Require a minimum of four calibrations per day. Exclude the first 24 hours of data from analysis due to initial sensor instability [18].

- Participant Cohort: Recruit a population that reflects the model's intended use case. For generalizable models, include individuals with normal glucose metabolism (NGM), prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes (T2D). A sample protocol from The Maastricht Study specifies >48 hours of CGM data per participant, with a target sample size of ~850 individuals [18].

- Data Inclusion/Exclusion: Include data from the full sensor wear period (e.g., 6 days) after the initial 24-hour warm-up. Apply quality checks to remove periods of sensor signal drop-out or artifact.

2.2 Utilizing Real-World and Public Datasets Leveraging existing datasets can accelerate research and provide benchmarks.

- Public Datasets: The OhioT1DM Dataset is a key resource for validating models on type 1 diabetes (T1D) data, containing CGM, insulin, and meal data for 6 individuals [18].

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): Data from commercial CGM use (e.g., Dexcom G6) collected over 90 days from 112 patients, encompassing over 1.6 million CGM values, provides insights into glycemic patterns under free-living conditions [19]. This data is essential for testing model robustness.

Table 1: Key CGM Datasets for ML Research

| Dataset Name | Population | Sample Size (n) | Key Variables | Primary Research Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Maastricht Study [18] | NGM, Prediabetes, T2D | 851 | CGM, Accelerometry | Generalizable glucose prediction model development |

| OhioT1DM Dataset [18] | Type 1 Diabetes | 6 | CGM, Insulin, Meals | Proof-of-concept translation to T1D |

| Dexcom G6 Real-World [19] | Type 1 Diabetes (Youth) | 112 | CGM, Insulin Pump Data | Hypoglycemia prediction and feature engineering |

Data Preprocessing & Feature Engineering Workflow

Raw CGM signals require extensive preprocessing and thoughtful feature engineering to be optimally useful for machine learning algorithms.

3.1 Data Preprocessing Protocol A standardized preprocessing workflow is essential for data quality [20].

- Handling Missing Data: For short gaps (<15-20 minutes), use linear interpolation to impute missing CGM values. For longer gaps, consider more advanced imputation methods (e.g., K-Nearest Neighbors) or exclude the data segment [20].

- Normalization: Scale CGM values to a standard range (e.g., 0 to 1) to ensure features contribute equally to model training and prevent dominance by features with larger native ranges [20].

- Synchronization: When integrating multimodal data (e.g., CGM and 15-second accelerometry), synchronize timestamps and interpolate CGM data to match the higher-frequency signal [18].

3.2 Feature Engineering for Glycemic Prediction Feature engineering transforms raw CGM time series into predictive variables. The following protocol, derived from hypoglycemia prediction research, categorizes features by their temporal relevance [19].

Table 2: Feature Engineering Protocol for Hypoglycemia Prediction

| Feature Category | Time Horizon | Example Features | Physiological Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | < 1 hour | glucose, diff_10, diff_20, diff_30, slope_1hr |

Captures immediate rate of change and current state [19] |

| Medium-Term | 1 - 4 hours | sd_2hr, sd_4hr, slope_2hr |

Reflects recent glycemic variability and trends [19] |

| Long-Term | > 4 hours | time_below70, time_above200, rebound_high, rebound_low |

Encodes patient-specific control patterns and historical events [19] |

| Snowball Effect | 2 hours | pos (sum of increments), neg (sum of decrements), max_neg |

Quantifies the accumulating effect of consecutive glucose changes [19] |

| Interaction/Non-Linear | N/A | glucose * diff_10, glucose_sq |

Models the non-linear risk of hypoglycemia (a fall is more critical at low baseline glucose) [19] |

Figure 1: CGM Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering Workflow

Machine Learning Model Development & Experimental Protocols

With curated features, researchers can design and train ML models for specific predictive tasks.

4.1 Experimental Design for Glucose Prediction A standard experiment involves training models to predict glucose levels at a future time horizon (PH) [18].

- Input: A sliding window of prior CGM data (e.g., 30 minutes, equivalent to 6 data points).

- Output: Predicted glucose value at a specified prediction horizon (e.g., 15 or 60 minutes).

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset by participant (not by time) to prevent data leakage. A standard split is 70% for training, 10% for hyperparameter tuning, and 20% for held-out evaluation [18].

- Model Architectures: Compare a range of models, including:

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks to capture temporal dependencies [18].

- Gradient-Boosting Machines: For feature-based approaches, models like XGBoost can effectively leverage engineered features [19].

- Foundation Models: For large-scale data, transformer-based models like GluFormer can be pre-trained on millions of CGM measurements and fine-tuned for specific tasks [21].

4.2 Model Evaluation Protocol Rigorous evaluation requires multiple metrics to assess both accuracy and clinical safety [18] [17].

- Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE): Measures the absolute accuracy of predictions (in mmol/L or mg/dL).

- Spearman's Correlation Coefficient (rho): Assesses the monotonic relationship between predicted and actual glucose values.

- Surveillance Error Grid (SEG) Analysis: A critical clinical safety metric that categorizes prediction errors based on their perceived clinical risk (e.g., "no effect," "self-treatment," "dangerous"). Report the percentage of predictions in "clinically safe" zones (>99% for 15-minute, >98% for 60-minute horizons is achievable) [18].

- Sensitivity and Specificity: For hypoglycemia classification tasks (e.g., predicting <70 mg/dL), report sensitivity (>91% achievable) and specificity (>90% achievable) [19].

Table 3: Performance Benchmarks for Glucose Prediction Models

| Model / Study | Prediction Horizon | RMSE | Sensitivity/Specificity | Clinical Safety (SEG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGM-Based Model (Maastricht) [18] | 15 minutes | 0.19 mmol/L | N/A | >99% |

| CGM-Based Model (Maastricht) [18] | 60 minutes | 0.59 mmol/L | N/A | >98% |

| Feature-Based Hypoglycemia Prediction [19] | 60 minutes | N/A | >91% / >90% | N/A |

| Translated to T1D (OhioT1DM) [18] | 60 minutes | 1.73 mmol/L | N/A | >91% |

Figure 2: RNN-based Glucose Prediction Model Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential tools, datasets, and software for building ML models with CGM data.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for CGM-based ML

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGM Devices | Hardware | Generate primary glucose time-series data. | Medtronic iPro2, Dexcom G6, Abbott FreeStyle Libre [18] [19] |

| Public CGM Datasets | Data | Provide benchmark data for model training and validation. | OhioT1DM Dataset, The Maastricht Study (upon request) [18] |

| Glycemic Variability Analysis Tool | Software | Calculate standard CGM metrics (Mean, SD, CV). | Glycemic Variability Research Tool (GlyVaRT) [18] |

| Python ML Stack | Software | Core programming environment for data preprocessing, model building, and evaluation. | Libraries: Pandas, NumPy, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch [20] |

| Consensus Error Grid | Analytical Tool | Evaluate the clinical safety of glucose predictions. | Available as a standardized Python script or library [17] |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate-d5 | Tauroursodeoxycholate-d5, MF:C26H45NO6S, MW:504.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Duloxetine-d7 | Duloxetine-d7, MF:C18H19NOS, MW:304.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

CGM data, when processed through the rigorous protocols outlined, provides a powerful foundation for predictive glycemic models. Current research demonstrates that ML models can achieve high accuracy and clinical safety for near-term prediction horizons [18] [19]. The future of this field lies in several key areas: the development of large, generalizable foundation models like GluFormer [21]; the effective integration of contextual data (e.g., insulin, meals, accelerometry) to improve longer-horizon predictions [18] [19]; and the translation of these algorithms into commercially viable, regulatory-approved closed-loop systems and decision-support tools that can improve the lives of people with diabetes. Adherence to emerging consensus standards for CGM evaluation will be crucial for validating these models for clinical use [17].

Patients with diabetes undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (HD) represent a distinct and challenging special population within glycemic management research. These individuals experience markedly reduced survival rates of approximately 3.7 years—nearly half that of HD patients without diabetes—underscoring the critical need for optimized treatment strategies [22]. The hemodialysis procedure itself induces significant glycemic variability, creating a paradoxical environment where patients face heightened risks of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia within a 24-hour cycle [22]. These challenges are compounded by the limitations of conventional glycemic markers like HbA1c, which can be biased by anemia, iron therapy, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and the uremic environment [23].

The integration of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and machine learning (ML) technologies offers promising avenues to address these complex challenges. By enabling detailed analysis of glycemic patterns and predicting adverse events, these approaches facilitate proactive interventions tailored to the unique physiological dynamics of HD patients [22]. This application note examines the specific challenges in this population and details advanced protocols for researching and implementing ML-driven glycemic management systems within the broader context of predicting glycemic response.

Key Challenges in Diabetes Management for Hemodialysis Patients

Physiological and Clinical Challenges

Managing diabetes in HD patients involves navigating a complex interplay of physiological alterations and clinical constraints, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Glycemic Management for Hemodialysis Patients with Diabetes

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Impact on Glycemic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Glycemic Variability | HD-induced fluctuations; increased glucose excursions | Significant differences between dialysis vs. non-dialysis days; highest hypoglycemia risk 24h post-dialysis start [22] |

| Hypoglycemia Risk | Reduced renal gluconeogenesis; insulin/glucose removal during HD | Increased morbidity/mortality; heightened risk of asymptomatic hypoglycemia during/after dialysis [22] [23] |

| Assessment Limitations | HbA1c inaccuracy due to anemia, ESA use, uremia | Unreliable glycemic assessment; necessitates alternative metrics like CGM-derived TIR, TBR, TAR [23] |

| Therapeutic Limitations | "Burnt-out diabetes" phenomenon; altered drug pharmacokinetics | Requires medication review/dose adjustment; increased hypoglycemia risk with certain agents [23] |

| Comorbidity Burden | Diabetic foot; cardiovascular disease; high mortality | Requires intensive multidisciplinary care approach [24] |

Limitations of Conventional Glycemic Metrics

In HD populations, traditional glycemic biomarkers present significant limitations that affect treatment decisions. HbA1c can be biased by factors affecting erythrocyte turnover, including iron deficiency, erythropoietin-stimulating agents, and frequent blood transfusions [23]. Alternative markers like glycated albumin (GA) and fructosamine are influenced by abnormal protein metabolism, hypoproteinemia, and the uremic environment, potentially leading to misleading values [23]. These limitations have accelerated the adoption of CGM-derived metrics—particularly Time in Range (TIR)—as more reliable indicators of glycemic control in this population [23].

Machine Learning for Glycemic Prediction in Hemodialysis

Research Foundation and Rationale

Machine learning offers a powerful approach to address glycemic variability in HD patients by identifying complex, non-linear patterns in CGM data that may not be apparent through conventional analysis. Recent research demonstrates that predicting substantial hypo- and hyperglycemia in HD patients with diabetes is feasible using ML models, enabling proactive interventions to prevent adverse events [22].

The international consensus from the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD) Congress recommends specific glycemic targets for high-risk populations, including those with renal disease: ≤1% Time Below Range (TBR <70 mg/dL), ≤10% Time Above Range (TAR >250 mg/dL), and ≥50% Time in Range (TIR 70–180 mg/dL) [22]. These metrics provide standardized endpoints for ML model development and validation.

Exemplary ML Implementation Protocol

Table 2: Machine Learning Protocol for Predicting Glycemic Events on Hemodialysis Days

| Protocol Component | Implementation Details |

|---|---|

| Study Objective | Develop ML models to predict substantial hypo- (TBR≥1%) and hyperglycemia (TAR≥10%) during the 24 hours following HD initiation [22] |

| Patient Population | 21 adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes receiving chronic HD/hemodiafiltration and insulin therapy [22] |

| Data Collection | CGM data (Dexcom G6), HbA1c levels, pre-dialysis insulin dosages; 555 dialysis days analyzed [22] |

| Model Development | Three classification models trained/tested: Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and TabPFN [22] |

| Feature Engineering | CGM-derived metrics; feature selection via Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) [22] |

| Performance Results | - Hyperglycemia prediction: Logistic Regression (F1: 0.85; ROC-AUC: 0.87)- Hypoglycemia prediction: TabPFN (F1: 0.48; ROC-AUC: 0.88) [22] |

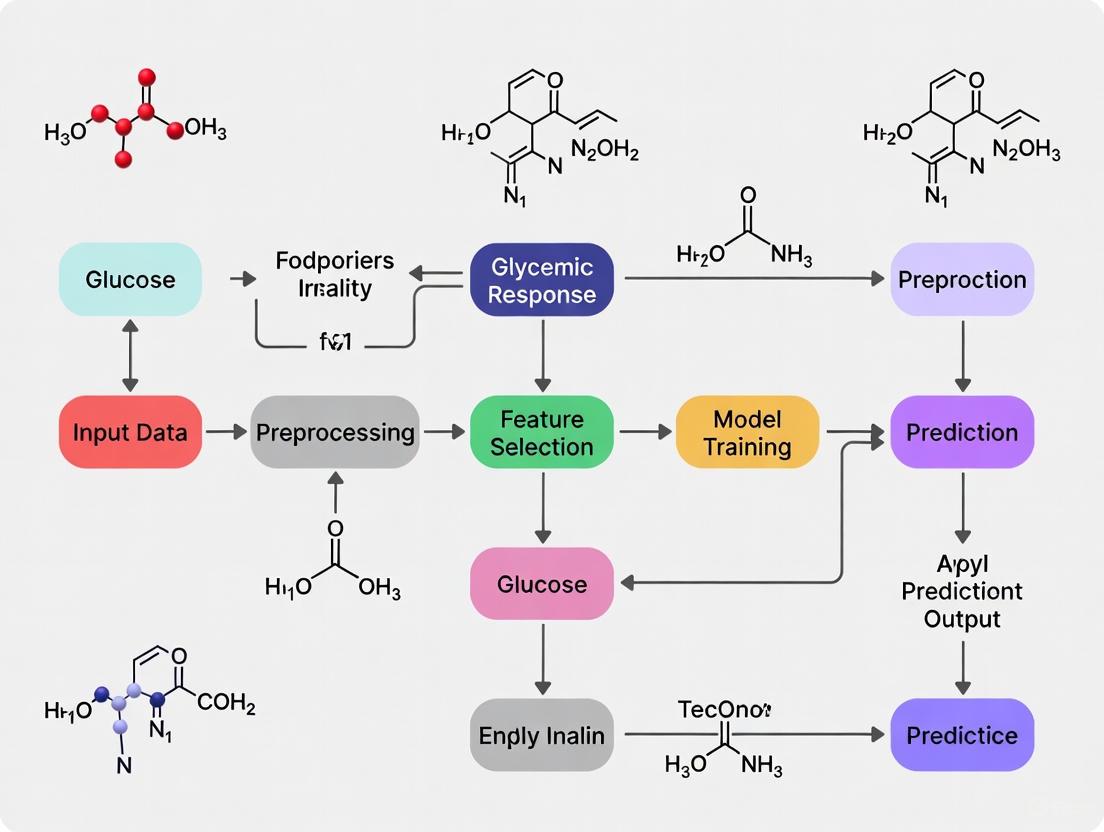

Figure 1: Machine learning workflow for predicting glycemic events in hemodialysis patients. The process begins with data collection from diabetic patients on HD, progresses through feature engineering and model training, and culminates in predictive outputs for clinical intervention.

Advanced CGM Application Protocol in Hemodialysis Research

CGM Deployment and Data Processing

The following protocol details the methodology for employing CGM in HD populations, based on validated research approaches:

Sensor Deployment: Apply CGM sensors (e.g., FreeStyle Libre Pro, Dexcom G6) to the upper arm contralateral to vascular access. Ensure continuous wear for 10-14 consecutive days, maintaining at least 70% sensor activity for data validity [25]. For HD sessions, document precise dialysis timing, dialysate glucose concentration, and any procedural interruptions.

Data Collection Parameters: Capture comprehensive glucose metrics including mean sensor glucose level, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (%CV), and international consensus parameters: Time in Range (TIR: 70-180 mg/dL), Time Below Range (TBR: <70 mg/dL and <54 mg/dL), and Time Above Range (TAR: >180 mg/dL) [25].

Glycemic Event Definition: Define hypoglycemia as sensor glucose <70 mg/dL for >30 minutes. Categorize by timing: daytime (06:00-24:00) vs. nocturnal (00:00-06:00). Specifically identify HD-induced hypoglycemia as episodes occurring during or after dialysis until the next meal [25].

Data Processing: Calculate the incremental area under the curve (iAUC) over a 2-hour postprandial window for meal response analysis. Align CGM data with HD sessions, differentiating between dialysis and non-dialysis days. For ML applications, segment data into 24-hour pre-dialysis (feature segment) and 24-hour post-dialysis initiation (prediction segment) [22].

CGM-Derived Glycemic Metrics

Table 3: CGM-Derived Glycemic Metrics Following Semaglutide Intervention in HD Patients

| Glycemic Parameter | Baseline | 6-Month Follow-up | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | 7.8 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 0.0318 |

| Glycated Albumin (%) | 23.6 ± 5.2 | 19.6 ± 4.3 | 0.0062 |

| Mean Sensor Glucose (mg/dL) | 172.0 ± 36.2 | 138.1 ± 25.4 | 0.0177 |

| Glucose Variability (SD) | 56.8 ± 24.4 | 42.1 ± 12.8 | 0.0264 |

| Time in Range (%) | 57.0 (34.0-86.0) | 78.0 (51.4-97.0) | 0.0420 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (range). Source: Adapted from semaglutide study in HD patients [25].

Therapeutic Management Protocol

Pharmacologic Intervention Protocol

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: For patients with T2D and obesity on HD, semaglutide demonstrates significant efficacy. Initiate at 0.25 mg subcutaneously once weekly. If tolerated, increase to 0.5 mg after 4 weeks, with potential escalation to 1.0 mg weekly after an additional 4 weeks [25]. For patients experiencing gastrointestinal intolerance, maintain the current dose without escalation if glycemic markers are adequately controlled.

Insulin Regimen De-intensification: The IDEAL trial protocol provides a framework for simplifying complex insulin regimens. For patients on multiple daily injection (MDI) insulin therapy, transition to fixed-ratio combinations like iGlarLixi (containing insulin glargine and lixisenatide), administered once daily [26]. This approach maintains glycemic control while reducing hypoglycemia risk and treatment burden.

Insulin Dose Adjustment: For HD patients initiating GLP-1RA therapy, closely monitor for hypoglycemia. Implement proactive insulin reduction when clinical hypoglycemia or CGM-detected glucose <70 mg/dL occurs. In the referenced semaglutide study, total daily insulin doses significantly decreased from 48.5 to 43.5 units/day while maintaining glycemic control [25].

Figure 2: Clinical decision pathway for glycemic management in hemodialysis patients. The flowchart outlines therapeutic choices based on patient presentation, including GLP-1RA initiation, insulin de-intensification, and dose adjustment guided by CGM monitoring.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Technologies for HD Glycemia Studies

| Research Tool | Specification/Model | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | FreeStyle Libre Pro (Abbott); Dexcom G6 | Retrospective/prospective glucose monitoring; captures glycemic variability during/inter-dialysis [25] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Logistic Regression, XGBoost, TabPFN | Prediction of hypo-/hyper-glycemia events; pattern recognition in CGM data [22] |

| Glycemic Analysis Software | Custom Python/R pipelines with iAUC calculation | Processing CGM data; calculating TIR, TBR, TAR; feature extraction for ML models [22] |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonist | Semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) | Investigational intervention for glycemic/weight control in HD patients [25] |

| Fixed-Ratio Combination | iGlarLixi (Suliqua) | Insulin de-intensification strategy; reduces regimen complexity while maintaining control [26] |

| rac Felodipine-d3 | rac Felodipine-d3 Calcium Channel Blocker | rac Felodipine-d3is a deuterated calcium channel blocker for hypertension research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Lopinavir-d8 | Lopinavir-d8, MF:C37H48N4O5, MW:636.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of continuous glucose monitoring and machine learning prediction models represents a transformative approach to diabetes management in hemodialysis patients. These technologies address fundamental challenges in this population by enabling precise glycemic assessment and proactive intervention for the marked glycemic fluctuations induced by dialysis therapy. Current evidence supports the feasibility of predicting substantial hypo- and hyperglycemia on dialysis days using ML models, while novel therapeutic protocols using GLP-1RAs and insulin de-intensification strategies offer promising avenues for improved patient outcomes.

Future research should prioritize multicenter validation of ML algorithms in larger HD populations, development of real-time clinical decision support systems integrating CGM data with electronic health records, and randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these advanced technologies on hard clinical endpoints including mortality, hospitalization rates, and dialysis-related complications.

Interindividual and Intraindividual Variability in Glycemic Responses

Glycemic variability—differences in blood glucose responses to food—is a critical factor in diabetes management and metabolic health research. Interindividual variability (differences between people) and intraindividual variability (differences within the same person over time) complicate glycemic predictions. Machine learning (ML) algorithms can address this complexity by integrating multi-omics data, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), and clinical variables to personalize forecasts. This document outlines experimental protocols, data sources, and reagent solutions for studying glycemic variability within ML-driven research.

Quantitative Data on Glycemic Variability

Table 1: Interindividual Variability in Postprandial Glycemic Responses (PPGRs) to Carbohydrate Meals

| Carbohydrate Source | Mean Delta Glucose Peak (mg/dL) | Correlation with Metabolic Phenotypes | Key Demographic Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Highest among starchy meals | Insulin resistance, beta cell dysfunction | More common in Asian individuals |

| Potatoes | High | Insulin resistance, lower disposition index | None reported |

| Grapes | High (early peak) | Insulin sensitivity | None reported |

| Beans | Lowest | None reported | None reported |

| Pasta | Low | None reported | None reported |

| Mixed Berries | Low | None reported | None reported |

Source: Adapted from [27]. Meals contained 50 g carbohydrates. PPGRs measured via CGM.

Table 2: Intraindividual Variability and Reproducibility of Glycemic Responses

| Variability Type | Cause/Source | Impact on PPGR | Statistical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meal Replication | Same meal consumed on different days | Moderate reproducibility (ICC: 0.26–0.73) | ICC highest for pasta (0.73) |

| Time of Day | Lunch vs. dinner | Significant PPGR differences | P < 0.05 (lunch), P < 0.001 (dinner) [28] |

| Menstrual Cycle | Perimenstrual phase | Elevated Glumax | P < 0.05 [28] |

| Meal Composition | Fiber, protein, fat preloads | Reduced PPGR in insulin-sensitive individuals | Mitigators less effective in insulin-resistant individuals [27] |

ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; Glumax: Peak postprandial glucose rise.

Table 3: Machine Learning Performance in Glycemic Prediction

| Prediction Task | ML Model | Performance Metrics | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| BG Level Prediction (15 min) | Neural Network Model (NNM) | RMSE: 0.19 mmol/L; Correlation: 0.96 [29] | CGM |

| BG Level Prediction (60 min) | Neural Network Model (NNM) | RMSE: 0.59 mmol/L; Correlation: 0.72 [29] | CGM + Accelerometry |

| Hypoglycemia Prediction | Gradient Boosting | Sensitivity: 0.76; Specificity: 0.91 [29] | EHR, CGM, Medication data |

| PPGR Prediction | XGBoost | R = 0.61 (T1D), R = 0.72 (T2D) [28] | Demographics, Meal timing, Food categories |

RMSE: Root Mean Square Error; EHR: Electronic Health Records.

Experimental Protocols for Glycemic Variability Research

Protocol 1: Assessing PPGRs to Standardized Carbohydrate Meals

Objective: Quantify interindividual and intraindividual variability in PPGRs to carbohydrate-rich meals. Materials:

- CGM devices (e.g., Dexcom G6, FreeStyle Libre) [28] [30].

- Standardized meals (50 g available carbohydrates): rice, bread, potatoes, pasta, beans, grapes, mixed berries [27].

- Nutrient composition database (e.g., Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies).

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation:

- Meal Administration:

- Administer each meal in duplicate on separate days in a randomized order.

- Ensure ≥8-hour fasting before meals.

- CGM Data Collection:

- Record glucose every 5–15 minutes for 2–3 hours postprandially [30].

- Extract PPGR features: AUC(>baseline), delta glucose peak, time to peak.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for replicate meals.

- Cluster participants into "spikers" and "non-spikers" based on delta glucose peak [27].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Mitigators of PPGRs

Objective: Test the effect of fiber, protein, and fat preloads on PPGRs. Materials:

- Preloads: pea fiber (fiber), egg white (protein), cream (fat) [27].

- Standardized rice meal (50 g carbohydrates).

Procedure:

- Preload participants with one mitigator 10 minutes before the rice meal.

- Measure PPGRs using CGM as in Protocol 1.

- Compare AUC(>baseline) and delta glucose peak with/without preloads.

- Stratify analysis by insulin sensitivity (e.g., SSPG < 120 mg/dL vs. ≥120 mg/dL) [27].

Protocol 3: ML Model Development for Glycemic Prediction

Objective: Train ML models to predict PPGRs or hypoglycemia. Materials:

- Dataset: CGM data, accelerometry, EHR (e.g., insulin doses, meal timings) [31] [10].

- Software: Python (scikit-learn, TensorFlow).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Feature Engineering:

- Model Training:

- Validation:

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Metabolic Pathways Influencing Glycemic Variability

Title: Metabolic Factors in Glycemic Responses

Diagram 2: Workflow for ML-Based Glycemic Prediction

Title: ML Pipeline for Glucose Forecasting

The Scientist’s Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Glycemic Variability Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Tracks interstitial glucose levels in real-time (e.g., every 5 minutes) | PPGR measurement post-meal [27] [30] |

| Standardized Meals | Provides consistent carbohydrate loads (50 g) for PPGR comparisons | Testing rice, bread, or potato responses [27] |

| Accelerometers | Measures physical activity’s impact on glucose metabolism | Improving 60-minute glucose predictions [31] |

| Electronic Health Records (EHR) | Source of clinical variables (insulin doses, medications) for ML models | Predicting hypoglycemia in ICU patients [10] |

| Multi-omics Datasets | Includes microbiome, metabolomics, and genomic data for personalized insights | Identifying PPGR-associated microbial pathways [27] |

| Gradient Boosting Algorithms (XGBoost) | Predicts PPGRs or hypoglycemia risks from complex datasets | Achieving R = 0.72 for T2D PPGR prediction [28] |

| Ferulic Acid-d3 | Ferulic Acid-d3, CAS:860605-59-0, MF:C10H10O4, MW:197.204 | Chemical Reagent |

| Voriconazole-d3 | Voriconazole-d3, MF:C16H14F3N5O, MW:352.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Interindividual and intraindividual glycemic variability is influenced by food composition, metabolic phenotypes, and temporal factors. ML models—especially neural networks and gradient boosting—can mitigate this variability by integrating CGM, EHR, and meal data. Standardized protocols for meal tests and mitigator interventions enable reproducible research. Future work should focus on real-time ML integration into clinical decision support systems.

Methodological Approaches and Clinical Applications of ML Algorithms

Within research aimed at predicting glycemic response, the selection of an appropriate machine learning model is paramount. Such predictions are critical for developing personalized treatment strategies, optimizing drug efficacy, and preventing adverse events like hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three foundational machine learning models—Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost—tailored for researchers and scientists in the field of drug development and metabolic disease.

The following table summarizes the typical performance characteristics of these three models as applied to tasks like hypoglycemia prediction, based on recent research.

Table 1: Model Performance Comparison for Hypoglycemia Prediction [32]

| Model | Predictive Accuracy | Kappa Coefficient | Macro-average AUC | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | 93.3% | 0.873 | 0.960 | High accuracy, robust to overfitting, good interpretability via feature importance |

| XGBoost | 92.6% | 0.860 | 0.955 | Superior handling of imbalanced data, high precision on structured/tabular data |

| Logistic Regression | 83.8% | 0.685 | 0.788 | High model interpretability, establishes baseline performance, efficient to train |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Multinomial Logistic Regression Model

Application Note: Use this model for multi-class classification of hypoglycemia severity (e.g., normal, mild, moderate-to-severe) when interpretability of risk factors is a primary research objective [32] [33].

Workflow:

Data Preparation and Variable Coding

- Outcome Variable: Define hypoglycemia severity groups based on venous plasma glucose levels. Example categories:

- Normal glycemia: >3.9 mmol/L

- Mild hypoglycemia: 3.0 – 3.9 mmol/L

- Moderate-to-severe hypoglycemia: <3.0 mmol/L [32]

- Covariates: Include clinically relevant features such as age, HbA1c, mean blood glucose, serum creatinine, C-peptide, and medication usage [32].

- Reference Category: Designate one outcome category as the reference (e.g., "Normal glycemia"). The model will compute log odds for all other categories against this baseline [33].

- Outcome Variable: Define hypoglycemia severity groups based on venous plasma glucose levels. Example categories:

Model Estimation

- Use maximum likelihood estimation to fit the model.

- The logit functions for a 3-class outcome (with

0as reference) are:- ( g1(\mathbf{x}) = \ln\frac{P(Y=1|\mathbf{x})}{P(Y=0|\mathbf{x})} = \alpha1 + \beta{11}x1 + \cdots + \beta{1p}xp ) (Mild vs. Normal)

- ( g2(\mathbf{x}) = \ln\frac{P(Y=2|\mathbf{x})}{P(Y=0|\mathbf{x})} = \alpha2 + \beta{21}x1 + \cdots + \beta{2p}xp ) (Moderate-to-severe vs. Normal) [33]

Output Interpretation

- Interpret the results in terms of relative risk ratios by exponentiating the coefficients (( e^\beta )).

- A relative risk ratio greater than 1 for a given variable indicates an increased likelihood of being in the comparison group versus the reference group as the variable increases [33].

Diagram: Multinomial Logistic Regression Workflow

Protocol 2: Tuning a Random Forest Classifier

Application Note: Apply Random Forest for robust, high-accuracy prediction of hypoglycemic events. Its ensemble nature reduces overfitting and provides insights into feature importance [32] [34].

Workflow:

Data Preprocessing

- Handle missing values (RF can handle them, but imputation is often recommended).

- No need for feature scaling. RF is robust to the scale of features [34].

Hyperparameter Optimization

- Use RandomizedSearchCV or GridSearchCV for hyperparameter tuning [35].

- Key hyperparameters to optimize [35] [36]:

n_estimators: Number of trees in the forest (more trees increase stability but slow training).max_depth: Maximum depth of the trees (controls overfitting).min_samples_split: Minimum samples required to split an internal node.min_samples_leaf: Minimum samples required at a leaf node.max_features: Number of features to consider for the best split ("sqrt" is a common default).

Model Training & Validation

Feature Importance Analysis

- Extract feature importance scores from the trained model, which indicate the contribution of each variable to the model's predictions [32].

Diagram: Random Forest Hyperparameter Tuning Logic

Protocol 3: Optimizing XGBoost with Genetic Algorithms

Application Note: For maximum predictive performance on structured glycemic data, especially with class imbalances, XGBoost is often superior. Its performance can be further enhanced using advanced optimization techniques like Genetic Algorithms (GA) [37] [34].

Workflow:

Data Balancing

- Address class imbalance (e.g., few hypoglycemic events) using techniques like SMOTEENN (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique edited with Nearest Neighbors), which has shown efficiency in diabetes prediction tasks [37].

Hyperparameter Optimization with Genetic Algorithm

- Implement a GA to find the global optimum of XGBoost's complex parameter space [37].

- Key XGBoost parameters for GA to optimize:

learning_rate(eta): Shrinks feature weights to make boosting more robust.max_depth: Maximum depth of a tree.subsample: Fraction of samples used for training each tree.colsample_bytree: Fraction of features used for training each tree.reg_alpha(L1) andreg_lambda(L2): Regularization terms to prevent overfitting [34].

Model Training and Interpretation

- Train the final model with the GA-optimized parameters. XGBoost builds trees sequentially, with each new tree correcting the errors of the previous ones [34].

- Use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values for model interpretation. SHAP provides consistent and theoretically robust feature importance values, showing both the magnitude and direction (increase or decrease) of a feature's impact on the prediction [37] [38].

Diagram: GA-XGBoost Optimization Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Glycemic Prediction Research [32] [31] [38]

| Item / Solution | Function / Application Note |

|---|---|

| Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Data | Source for retrospective clinical variables (e.g., HbA1c, creatinine, medication history). Crucial for training models on clinical outcomes like hypoglycemia severity [32]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides high-frequency interstitial glucose measurements. The primary data stream for building time-series prediction models of future glucose levels [31] [38]. |

| Triaxial Accelerometer | Quantifies physical activity and energy expenditure. Used as an exogenous input variable to improve the accuracy of glucose prediction models by accounting for metabolic fluctuations [31]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A unified framework for interpreting model output. Critical for explaining "black-box" models like XGBoost and ensuring learned relationships (e.g., between insulin and glucose) are physiologically sound [38]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) Library | An optimization technique for hyperparameter tuning. Used to efficiently navigate the complex parameter space of models like XGBoost to maximize predictive performance [37]. |

| Solifenacin-d5 Hydrochloride | Solifenacin-d5 Hydrochloride, MF:C23H27ClN2O2, MW:398.9 g/mol |

| rac Ramelteon-d3 | rac Ramelteon-d3, MF:C16H21NO2, MW:262.36 g/mol |

The management of diabetes, a chronic condition affecting hundreds of millions globally, hinges on effective glycemic control. Traditional approaches to predicting blood glucose levels and glycemic responses often rely on generic models that fail to account for significant interindividual variability. Recent advances in deep learning offer transformative potential for creating highly accurate, personalized predictive models. This article explores the application of three advanced deep learning architectures—Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), and Transformer networks—within glycemic response research. We provide a detailed comparative analysis, structured protocols for implementation, and practical toolkits to empower researchers and drug development professionals in harnessing these technologies.

Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Architectures

Selecting an appropriate neural network architecture is foundational to building effective predictive models for glycemic response. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of LSTM, GRU, and Transformer models.

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of LSTM, GRU, and Transformer Networks

| Parameter | LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) | GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) | Transformers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Memory cells with input, forget, and output gates [39] [40] | Combines input and forget gates into an update gate; fewer parameters [39] [40] | Attention-based mechanism without recurrence; uses self-attention [39] [40] |

| Handling Long-Term Dependencies | Excels in capturing long-term dependencies [39] | Better than RNNs but slightly less effective than LSTMs [39] | Excellent; uses self-attention to weigh importance of all elements in a sequence [39] [40] |

| Training Time & Parallelization | Slower due to complex gates; limited parallelism due to sequential processing [39] | Faster than LSTMs but slower than RNNs; same sequential processing limitations [39] | Requires heavy computation but allows full parallelization during training [39] |

| Key Advantages | Mitigates vanishing gradient problem; effective memory retention [39] [40] | Simplified structure; faster training; computationally efficient [39] [40] | Captures long-range dependencies effectively; highly scalable [39] [40] |

| Primary Limitations | Computationally intensive; high memory consumption [39] | Might not capture long-term dependencies as effectively as LSTM in some tasks [40] | High memory and data requirements; computationally expensive [39] [40] |

Performance in Glycemic Prediction

Empirical evidence from recent studies demonstrates the relative performance of these architectures in glucose forecasting. A 2024 comprehensive analysis evaluating deep learning models across diverse datasets found that LSTM demonstrated superior performance with the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and the highest generalization capability, closely followed by the Self-Attention Network (SAN), a type of Transformer [41]. The study attributed this to the ability of LSTM and SAN to capture long-term dependencies in blood glucose data and their correlations with various influencing factors [41].

Conversely, research into novel methods like Neural Architecture Search combined with Deep Reinforcement Learning has shown that GRU-based models can be optimized to achieve performance comparable to LSTMs, with one study reporting a 12.6% improvement in RMSE for a specific patient after optimization, highlighting their efficiency [42]. In a direct comparison for stock price prediction (a similar time-series task), an LSTM model achieved 94% accuracy, outperforming GRU and Transformer models [43]. This suggests that for many glycemic prediction tasks, LSTMs may offer a favorable balance of performance and complexity, while GRUs present a compelling option when computational resources are a primary constraint.

Experimental Protocols for Glycemic Response Prediction

This section outlines a detailed protocol for a study designed to characterize interindividual variability in postprandial glycemic response (PPGR) and develop personalized prediction models, adapting methodologies from recent research [44].

Study Design and Participant Recruitment

Objective: To characterize PPGR variability among individuals with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and identify factors associated with these differences using machine learning. Design: Prospective cohort study. Duration: 14-day active monitoring period per participant. Participants:

- Cohort Size: 800+ participants (adaptable based on resources) [44] [45].

- Inclusion Criteria: Adults (age 18-75) with physician-diagnosed T2D, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥7%, treated with ≥1 oral hypoglycemic agent, and mobile phone capable of running study applications [44].

- Exclusion Criteria: Use of prandial insulin, pregnancy, life expectancy ≤12 months, active cancer, contraindication to continuous glucose monitors (CGM) [44]. Setting: Multi-site recruitment from specialized diabetes clinics to ensure a diverse cohort [44].

Data Collection and Preprocessing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for data collection and preprocessing in a glycemic response study.

Title: Glycemic Response Study Workflow

Protocol Steps:

Baseline Assessment:

- Collect sociodemographic information, medical history, and current medications.

- Perform biometric measurements: weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure.

- Administer baseline surveys (e.g., WHO-5 Well-Being Index, Diabetes Distress Scale) [44].

- Collect blood samples for HbA1c, complete blood count, lipids, and other relevant biomarkers [44].

Device Fitting and Training:

- Fit participants with a CGM sensor (e.g., Abbott Freestyle Libre) on the upper arm.

- Provide and synchronize a smart wristband (e.g., Xiaomi Mi Band) for heart rate and activity monitoring.

- Install and train participants on a study-specific smartphone application for dietary and activity logging. Provide a paper logbook as a backup [44].

14-Day Active Monitoring:

- CGM Data: Collect interstitial glucose readings at 5-15 minute intervals continuously.

- Dietary Logging: Participants log all meal intake. The protocol includes consumption of standardized test meals (e.g., varying carbohydrate, fiber, protein, and fat content) and free-living foods. Meals are logged with details including nutritional composition and timing [44].

- Physical Activity: Data is collected via the smart wristband (METs, step counts) and participant logs [44].

- Medication & Sleep: Participants log medication intake and sleep patterns.

Data Preprocessing:

- Synchronization: Align all temporal data streams (CGM, meals, activity) to a common timeline.

- Handling Missing Data: Apply techniques such as interpolation or masking for short gaps in CGM data. Exclude periods with significant data loss.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate key features from raw data, such as incremental Area Under the Curve (AUC) for PPGR 2 hours after each meal [44], glycemic variability metrics, and rolling averages.

Model Development and Training Protocol

Primary Outcome: Postprandial Glycemic Response (PPGR), calculated as the incremental AUC 2 hours after each logged meal [44].

- Input Features: Historical glucose sequences, meal nutrient profiles (carbs, fat, protein, fiber, sugar), timing, physical activity metrics, and baseline patient characteristics (e.g., HbA1c, BMI) [44] [46].

- Data Splitting: Partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, ensuring data from a single participant is contained within one set to prevent data leakage.

- Model Architectures:

- LSTM/GRU Models: Implement using a many-to-one architecture. Tune hyperparameters like number of layers, hidden units, and learning rate.

- Transformer Models: Adapt for time-series by using positional encoding. Tune hyperparameters like number of attention heads, layers, and feed-forward dimension.

- Training with Imbalanced Data: Employ techniques to handle the rarity of hypo-/hyperglycemic events:

- Evaluation Metrics:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials, datasets, and software required for conducting research in deep learning-based glycemic prediction.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Measures interstitial glucose levels at high frequency (e.g., every 5-15 mins) for model training and validation [44] [46]. | Abbott Freestyle Libre, Dexcom G7; typically worn on the upper arm [44] [46]. |

| Smart Wristband / Activity Tracker | Captures physiological data related to energy expenditure and metabolic state [44]. | Xiaomi Mi Band; records heart rate, step counts, and calculates METs [44]. |

| Standardized Test Meals | Used to elicit and measure controlled postprandial glycemic responses, reducing dietary noise [44]. | Vegetarian meals with varying macronutrient proportions (carbohydrate, fiber, protein, fat) [44]. |

| Data Logging Application | Digital platform for participants to log dietary intake, activity, and medication in real-time. | A custom or commercially available app capable of timestamped logging and synchronization with other devices [44]. |

| Public Datasets (for Benchmarking) | Provide standardized data for model development, comparison, and reproducibility. | OhioT1DM [41] [47] (Type 1 Diabetes), other proprietary or public T2D datasets. |

| Clofibric-d4 Acid | Clofibric-d4 Acid, CAS:1184991-14-7, MF:C10H11ClO3, MW:218.67 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benzocaine-d4 | Benzocaine-d4 Deuterated Local Anesthetic | Benzocaine-d4 is a deuterated local anesthetic for research use only. It is used as an internal standard in bioanalytical studies and for investigating sodium channel block. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The integration of advanced deep learning architectures like LSTM, GRU, and Transformers into glycemic research marks a significant shift toward personalized diabetes management. LSTM networks currently offer a robust and well-validated approach for glucose prediction, consistently demonstrating strong performance. GRUs provide a compelling, computationally efficient alternative, especially in resource-constrained settings. While Transformers show immense promise due to their superior ability to capture long-range dependencies, their deployment may be gated by data and computational requirements. The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of these models through techniques like transfer learning and data augmentation, their application to diverse populations, and their ultimate integration into closed-loop systems and digital therapeutics that can deliver personalized dietary and therapeutic recommendations in real time.

Multi-Task Learning Frameworks for Simultaneous Glucose Forecasting and Hypoglycemia Detection

The management of diabetes mellitus requires continuous monitoring of glycemic states to prevent acute complications, such as hypoglycemia, and long-term sequelae. Traditional machine learning models have often approached glucose forecasting and hypoglycemia detection as separate tasks, potentially overlooking shared physiological patterns and leading to operational inefficiencies in clinical decision support systems [48]. Multi-task learning (MTL) frameworks address this limitation by learning these related tasks in parallel using a shared representation, which can improve generalization and performance, especially when data for individual tasks is scarce [49]. This document details the application of advanced MTL frameworks, namely GlucoNet-MM and a Domain-Agnostic Continual MTL (DA-CMTL) model, for the integrated and personalized prediction of blood glucose levels and hypoglycemic events. These protocols are situated within a broader research thrust aimed at developing machine learning algorithms that can predict individualized glycemic responses to improve diabetes care [44] [8].

Featured Multi-Task Learning Frameworks

GlucoNet-MM: A Multimodal Attention-Based Framework

GlucoNet-MM is a novel deep learning framework that combines an attention-based multi-task learning backbone with a Decision Transformer (DT) to generate personalized and explainable blood glucose forecasts [50].

- Architecture Overview: The model integrates heterogeneous, multimodal data streams, including continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), insulin dosage, carbohydrate intake, and physical activity. Its MTL backbone learns shared representations across multiple prediction horizons. The integrated DT module frames policy learning as a sequence modeling problem, conditioning future glucose predictions on desired glycemic outcomes [50].

- Interpretability and Uncertainty: The framework incorporates temporal attention visualizations and integrated gradient-based attribution methods to provide explainability for its predictions. Furthermore, it employs Monte Carlo dropout for uncertainty quantification, a critical feature for clinical trust and application [50].

DA-CMTL: A Domain-Agnostic Continual Learning Framework

The Domain-Agnostic Continual Multi-Task Learning (DA-CMTL) model is designed to perform generalized glucose level prediction and hypoglycemia event detection within a unified framework that adapts over time and across different patient populations [48].

- Architecture Overview: This model is trained on large-scale simulated datasets (Sim2Real transfer) and uses elastic weight consolidation to maintain performance on previously learned tasks when new data or tasks are introduced. This approach enhances the model's robustness and scalability for deployment in automated insulin delivery (AID) systems [48].

- Generalization Capability: Its domain-agnostic design supports generalization across different domains and patient cohorts, making it suitable for widespread clinical application [48].