Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside (SDG): Multifaceted Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential in Chronic Disease Prevention

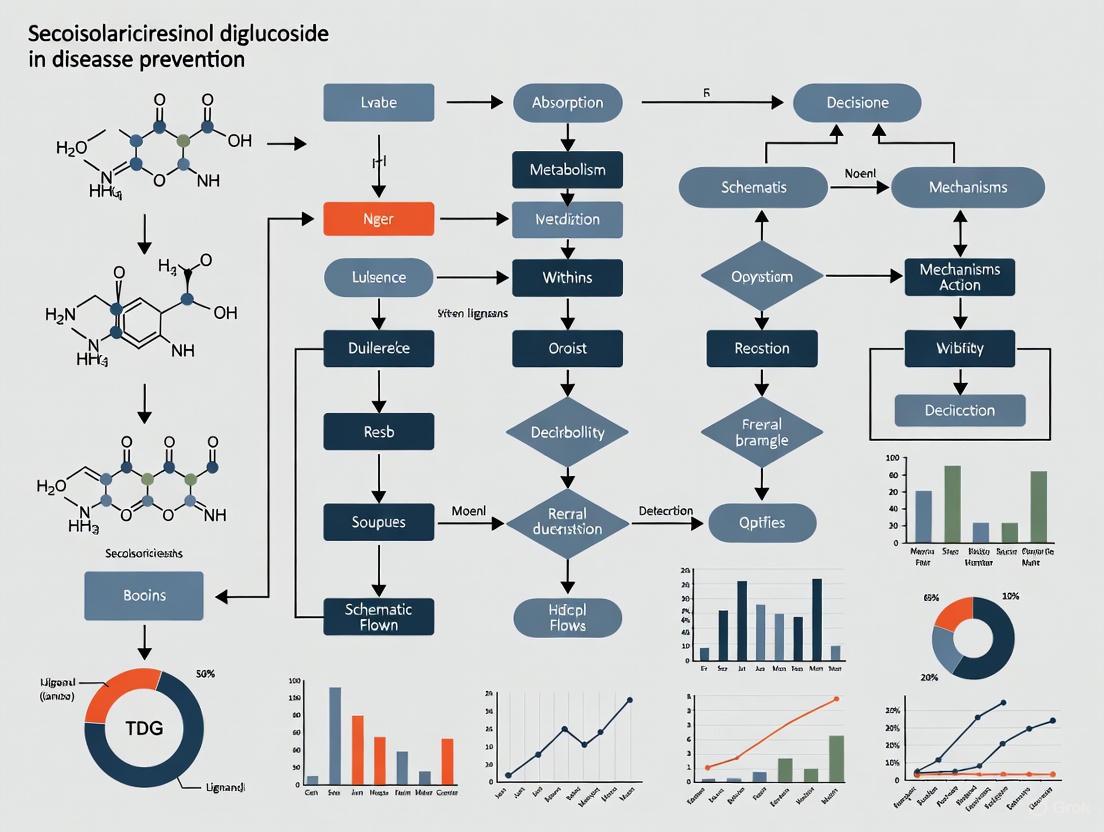

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on the flaxseed lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) and its role in disease prevention.

Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside (SDG): Multifaceted Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential in Chronic Disease Prevention

Abstract

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on the flaxseed lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) and its role in disease prevention. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores SDG's foundational biology, conversion to active mammalian lignans (enterodiol and enterolactone), and its pleiotropic mechanisms of action, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hormone-modulating activities. The scope encompasses methodological approaches for studying SDG, challenges in bioavailability and clinical translation, and a critical evaluation of preclinical and clinical evidence across various disease models, including cancer, metabolic syndrome, neuroinflammation, and premature ovarian insufficiency. The review aims to identify both promising therapeutic applications and key gaps for future research and drug development.

SDG Unveiled: From Botanical Source to Bioactive Metabolite

Chemical Identity and Natural Abundance in Flaxseed

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) is the principal lignan precursor found in flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.), representing a key phytochemical of significant interest in disease prevention research. This comprehensive technical guide examines SDG's chemical identity, natural abundance, and distribution within flaxseed tissues, providing researchers with essential data and methodologies for further investigation. As the richest known source of SDG, flaxseed provides a critical resource for studying the role of lignans in preventing various chronic diseases, with recent research illuminating its potential mechanisms in addressing conditions such as hyperuricemia, neurodegenerative disorders, and hormone-related pathologies [1] [2] [3]. The structural complexity and distribution patterns of SDG within flaxseed tissues present both challenges and opportunities for extraction and analysis, necessitating sophisticated methodological approaches for accurate quantification and characterization.

Chemical Identity of SDG

SDG is a complex polyphenolic compound with the systematic IUPAC name (2R,2'R,3R,3'R,4S,4'S,5S,5'S,6R,6'R)-2,2'-[((2R,3R)-2,3-Bis[(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]butane-1,4-diyl)bis(oxy)]bis[6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol] [4]. Its well-defined molecular structure serves as the foundation for its biological activities and research applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Chemical Characteristics of SDG

| Property | Specification |

|---|---|

| CAS Number | 148244-82-0 [5] |

| Molecular Formula | C₃₂H₄₆Oâ‚₆ [4] [5] |

| Molecular Weight | 686.71 g/mol [5] |

| Chemical Classification | Lignan glucoside [2] |

| Purity Available for Research | ≥97-98% [6] [5] |

SDG's chemical structure consists of two coniferyl alcohol residues linked by a bond between the 8 and 8' positions, forming the fundamental lignan skeleton [1]. In its natural state within flaxseed, SDG does not typically exist as a free compound but rather as a component of an ester-linked complex, often associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid and glucosylated derivatives of hydroxycinnamic acids [7]. This complex molecular arrangement significantly influences its extraction efficiency and bioavailability.

The compound exhibits stereochemical complexity with multiple chiral centers, contributing to its specific biological interactions. As a phytoestrogen, SDG demonstrates structural similarity to endogenous estrogens, enabling it to modulate hormonal pathways—a property of particular interest in cancer prevention research [7] [8]. Its diphenolic structure with multiple hydroxyl groups also provides potent antioxidant capabilities, functioning as a free radical scavenger and reducing oxidative stress in biological systems [4] [7] [9].

Natural Abundance and Distribution in Flaxseed

Flaxseed is recognized as the richest known dietary source of SDG, containing lignan concentrations 75-800 times greater than other oil seeds, cereals, legumes, fruits, and vegetables [2] [9]. The distribution of SDG within flaxseed is not uniform, with significant variation between different tissue components, influencing extraction strategies and nutritional utilization.

Table 2: SDG Abundance in Flaxseed and Comparative Sources

| Source | SDG Content | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Flaxseed (whole) | 1.0 - 4.0% (w/w) [3] | Varies by cultivar and processing |

| Flaxseed | 9.0 - 30.0 mg/g [2] [9] | Approximately 301 mg/100 g |

| Flaxseed Hulls | Primary location [6] | Highest concentration |

| Flaxseed Kernels | Low content [6] | Minimal distribution |

| Sesame Seeds | ~29 mg/100 g total lignans [9] | Primarily pinoresinol and lariciresinol |

| Other Dietary Sources | Typically <2 mg/100 g [9] | Grains, legumes, vegetables |

The spatial distribution of SDG within flaxseed reveals a distinctive pattern, with the compound primarily concentrated in the seed coat rather than the kernel [6]. This heterogeneous distribution significantly impacts processing strategies, as hull-kernel separation methods can yield enriched fractions for more efficient extraction. Research indicates that the tight combination between hull and kernel in flaxseed makes separation challenging, with current approaches including both dry methods (milling and sieving) and wet methods (hydraulic vortex separation after degumming), the latter demonstrating higher recovery rates [6].

Variation in SDG content is influenced by multiple factors including flaxseed cultivar, growing conditions, and post-harvest processing methods. Recent research has demonstrated that targeted processing techniques can significantly alter SDG levels and distribution, with germination and microwave treatments showing particular promise for enhancing lignan content in specific flaxseed fractions [6].

Extraction and Isolation Methodologies

The complex nature of SDG as part of an ester-linked polymer in flaxseed necessitates specific extraction approaches that typically involve multiple steps including solvent extraction, hydrolysis, and purification. The following section details established and emerging methodologies for SDG extraction and isolation.

Conventional Extraction Protocols

Traditional SDG extraction begins with defatting flaxseed using hexane, followed by extraction of the lignan polymer precursor with polar solvent systems. Bakke and Klosterman established a fundamental laboratory process using equal parts of 95% ethanol and 1,4-dioxane for extraction from defatted flaxseed meal [2]. Subsequent alkaline hydrolysis (using sodium, calcium, ammonium, or potassium hydroxides) is required to liberate SDG from the lignan polymer complex [2] [4]. A representative detailed protocol involves:

- Defatting: Treat finely ground flaxseed with hexane (1:10 w/v) for 24 hours with continuous agitation, then filter and air-dry the residue [2] [6].

- Extraction: Extract defatted meal with 70% aqueous ethanol or methanol (1:10 w/v) using ultrasonic assistance at 300 W for 30 minutes, followed by vortex mixing for 30 minutes and centrifugation at 3500× g for 20 minutes [6].

- Hydrolysis: Combine supernatants and adjust to 20 mmol/L NaOH concentration, then hydrolyze in a water bath at 50°C for 12 hours [6].

- Purification: Pass the alkali solution through 0.22 μm membrane filters prior to analysis or further processing [6].

Advanced Extraction Technologies

Recent methodological advances focus on improving extraction efficiency while reducing solvent consumption and processing time. Novel technologies include microwave-assisted extraction, enzymatic treatments, and optimized germination protocols:

- Microwave-Assisted Germination: Treatment at 130 W for 10-14 seconds after germination for 72-96 hours significantly increases lignan content and antioxidant activity in specific flaxseed fractions [6].

- Ultrasonic Extraction: Application of ultrasound at 300 W for 30 minutes enhances extraction efficiency from hull and kernel components [6].

- Germination-Induced Enrichment: Germination for 24-96 hours upregulates genes encoding enzymes involved in lignan biosynthesis, significantly increasing SDG content and in vitro antioxidant activity [6].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SDG Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SDG Reference Standard | Chromatographic calibration | ≥97% purity [6] |

| Methanol/Ethanol | Extraction solvent | Chromatographic grade, 80% concentration [6] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline hydrolysis | 20 mmol/L concentration [6] |

| Macroporous Adsorption Resin AB-8 | Purification | For compound separation [1] |

| Silica Gel (200-300 mesh) | Chromatographic separation | Fraction purification [1] |

| Enzymatic Preparations | Polymer hydrolysis | Specific glycosidases [2] |

Analytical Characterization Techniques

Accurate quantification and characterization of SDG require sophisticated analytical methodologies. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with various detection systems represents the gold standard for SDG analysis:

UPLC-DAD Methodology:

- Column: BEH Shield RP18 (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) [6]

- Mobile Phase: Gradient of methanol (A) and 0.1% acetic acid in water (B) [6]

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min [6]

- Detection: Diode array detector at 280 nm [6]

- Calibration: SDG standards in concentration range of 0.16-1.6 mg SDG/g flaxseed [6]

Additional analytical approaches include gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for structural confirmation and ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) for enhanced sensitivity and specificity, particularly useful for detecting SDG metabolites in biological samples [2]. Quantitative analysis of microbial metabolites END and ENL in serum employs HPLC-MS with specific mass transitions for precise quantification in pharmacological studies [3].

Stability and Processing Considerations

SDG demonstrates notable stability under various processing conditions, enabling its incorporation into functional food products. Research indicates that SDG withstands baking temperatures up to 250°C, with approximately 80-95% retention in baked goods and pasta products [2]. Storage stability studies demonstrate minimal degradation when products are stored at room temperature for one week or frozen at -25°C for two months [2].

Thermal processing can even slightly increase SDG extractability, potentially due to increased porosity of heated seeds. Studies report that flaxseed samples heated at 250°C for 3.5 minutes showed increased SDG content (1200 mg/100 g) compared to unheated samples (1099 mg/100 g) [2]. However, optimal conservation of lignans during commercial food production requires careful consideration of initial raw material composition, water content, and applied temperatures.

Research Applications and Future Perspectives

SDG's chemical properties and natural abundance in flaxseed position it as a promising candidate for disease prevention research. Recent investigations have elucidated its potential mechanisms in various pathological conditions:

- Hyperuricemia: SDG alleviates hyperuricemia in mice by regulating uric acid metabolism and intestinal homeostasis, modulating key transport proteins including URAT1, GLUT9, and ABCG2 [1].

- Neurodegenerative Disorders: SDG attenuates neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease models by promoting gut microbial metabolites END and ENL, which activate GPER and enhance CREB/BDNF signaling pathways [3].

- Hormone-Related Conditions: SDG ameliorates premature ovarian insufficiency via PI3K/Akt pathway modulation, demonstrating its potential in addressing estrogen-related disorders [8].

Future research directions should focus on optimizing extraction methodologies for enhanced bioavailability, particularly through targeted bioconversion approaches. The critical role of gut microbiota in metabolizing SDG to bioactive enterolignans END and ENL underscores the importance of considering interindividual microbial variations in therapeutic applications [7] [3]. Advanced delivery systems to improve SDG stability and bioavailability represent another promising research avenue for maximizing its disease prevention potential.

Understanding SDG's chemical identity and natural abundance in flaxseed provides a fundamental foundation for developing targeted disease prevention strategies and optimizing this valuable phytochemical for therapeutic applications.

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) is the principal lignan found in flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) and has garnered significant scientific interest due to its potential role in disease prevention, including against cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes [10] [11]. As a phytoestrogen, it exhibits antioxidant properties and, following metabolism by gut microbiota to enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL), can modulate hormonal balance, offering protective effects against hormone-dependent cancers [10] [12]. Understanding its precise biosynthetic pathway is crucial for leveraging its nutraceutical potential. This technical guide details the enzymatic journey from core phenylpropanoid metabolites to the complex SDG lignan oligomers in flaxseed, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational resource for their investigative and therapeutic endeavors.

The Phenylpropanoid Foundation

The biosynthesis of SDG is embedded within the broader phenylpropanoid pathway, which generates a vast array of secondary metabolites based on intermediates from the shikimate pathway [13]. This pathway begins in the plastid, where erythrose-4-phosphate from the pentose phosphate pathway and phosphoenolpyruvate from glycolysis condense to form chorismate [14]. A series of enzymatic steps eventually produce the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine (Phe), the primary precursor for most plant phenolic compounds, including lignans [14].

Phe is subsequently deaminated by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) to form cinnamic acid, marking the entry into the general phenylpropanoid pathway [14]. This pathway involves several key modifications, as Artifical Intelligence 1 illustrates.

Artifical Intelligence 1: From primary metabolism to coniferyl alcohol.

The final core monomer for lignan biosynthesis is coniferyl alcohol. Its synthesis from ferulic acid involves activation to feruloyl-CoA by 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), reduction to coniferaldehyde by cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), and finally reduction to coniferyl alcohol by cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) and/or sinapyl alcohol dehydrogenase [14]. The regulation of this foundational pathway is complex and involves transcriptional control by MYB and bHLH protein families, which can act as both activators and repressors to fine-tune the metabolic output for different phenylpropanoids [15].

The Lignan-Specific Pathway to SDG

The dedicated lignan pathway begins with the stereospecific coupling of two coniferyl alcohol molecules. This reaction is directed by dirigent proteins (DIR), which guide the formation of (+)-pinoresinol without themselves catalyzing the reaction [14]. Pinoresinol is the first committed intermediate in the pathway to SDG.

From (+)-pinoresinol, a series of reduction and glycosylation steps occur, as Artifical Intelligence 2 shows.

Artifical Intelligence 2: The core pathway from coniferyl alcohol to the SDG-HMG oligomer.

The journey from pinoresinol to secoisolariciresinol is catalyzed by pinoresinol-lariciresinol reductase (PLR). This NADPH-dependent enzyme successively reduces pinoresinol first to lariciresinol and then to secoisolariciresinol (SECO) [14]. Finally, SECO is glycosylated by the enzyme UDP-glycosyltransferase 74S1 (UGT74S1) to form secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) [11] [14]. This glycosylation enhances the stability and water solubility of the lignan.

In flaxseed, SDG does not exist as a free molecule but is incorporated into an oligomeric structure. This "polymer" consists of five SDG residues interconnected by four 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric (HMG) units derived from HMG-CoA, forming a straight-chain ester-linked oligomer [16] [10]. The final step in the biosynthesis thus involves the mono- and di-substitution of SDG with HMG-CoA, creating precursors that oligomerize into the final SDG-HMG complex [16].

Key Enzymes and Rate-Limiting Steps

Research has identified three critical, rate-limiting steps in the conversion of pinoresinol to SDG [14]:

- Stereoselective coupling by dirigent (DIR) proteins.

- Reduction by pinoresinol-lariciresinol reductase (PLR).

- Glycosylation by UGT74S1.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the SDG Biosynthetic Pathway

| Enzyme | Gene/Abbreviation | Function in Pathway | Effect of Modulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase | PAL | Deaminates phenylalanine to cinnamic acid; gateway to general phenylpropanoid pathway [14]. | Affects flux into all downstream phenylpropanoids. |

| Cinnamyl-Alcohol Dehydrogenase | CAD | Reduces coniferaldehyde to coniferyl alcohol, the monolignol precursor [14]. | Impacts the pool of coniferyl alcohol available for coupling. |

| Dirigent Protein | DIR | Guides the stereospecific coupling of two coniferyl alcohol molecules to form (+)-pinoresinol [14]. | A key rate-limiting step determining stereochemistry. |

| Pinoresinol-Lariciresinol Reductase | PLR | Catalyzes the sequential reduction of (+)-pinoresinol to (+)-lariciresinol and then to (+)-secoisolariciresinol (SECO) [14]. | A key rate-limiting step; essential for SECO production. |

| UDP-Glucosyltransferase 74S1 | UGT74S1 | Transfers glucose molecules to SECO, forming the final SDG molecule [11]. | A key rate-limiting step; determines SDG stability and accumulation. |

Experimental Analysis of the Pathway

Elucidating the SDG biosynthetic pathway has relied on a combination of molecular, biochemical, and analytical techniques.

Key Methodologies

Stable and radioisotope precursor/tracer experiments have been instrumental in identifying intermediates. In one foundational study, researchers administered these isotopes to flaxseed capsules at different developmental stages and tracked the incorporation into various phenylpropanoid and lignan metabolites [16]. This approach allowed for the identification of 6a-HMG SDG and 6a,6a'-di-HMG SDG as major components of the ester-linked oligomers [16].

Metabolic profiling across five early stages of seed development provided a temporal map of intermediate accumulation, leading to the proposal of a comprehensive biochemical pathway [16]. For the identification and quantification of intermediates, techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) are used for SDG and its aglycone SECO, respectively [10]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) are critical for determining the precise chemical structure of novel intermediates and the final oligomeric complex [16].

Table 2: Core Experimental Methods for Pathway Analysis

| Methodology | Specific Application | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Stable/Radioisotope Tracer Analysis | Feeding labeled precursors (e.g., phenylalanine) to developing flax seeds and tracking incorporation [16]. | Identification of biosynthetic intermediates and establishment of precursor-product relationships. |

| Metabolic Profiling | Analysis of metabolite levels in size-segregated flax seed capsules across multiple developmental stages [16]. | Revealed the temporal sequence of intermediate accumulation leading to the SDG-HMG oligomer. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Quantification of SDG content in plant extracts [10]. | Accurate measurement of SDG levels, often with UV detection at 280 nm. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Analysis of the deglycosylated form, secoisolariciresinol (SECO) [10]. | Sensitive detection and identification of the lignan aglycone. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) & High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) | Structural elucidation of isolated compounds, such as 6a-HMG SDG and 6a,6a'-di-HMG SDG [16]. | Unambiguous determination of molecular structure and composition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SDG Pathway Investigation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Phenylalanine (e.g., ¹³C, ²H) | Used as a metabolic tracer to track the incorporation of the core precursor into the phenylpropanoid pathway and downstream lignans [16]. |

| Developing Flax Seed Capsules | The primary biological system for studying the in planta biosynthesis of SDG, especially across defined early developmental stages [16]. |

| HPLC & GC-MS Systems | Core analytical platforms for the separation, detection, and quantification of SDG, SECO, and related pathway intermediates [10]. |

| Heterologous Expression Systems (e.g., E. coli) | Used to express and purify recombinant flaxseed enzymes (e.g., PLR, UGT74S1) for in vitro functional characterization [11]. |

| Specific Antibodies against pathway enzymes (e.g., PLR, UGT74S1) | Enable protein-level detection, localization, and quantification of key biosynthetic enzymes within flaxseed tissues. |

| Glyasperin C | Glyasperin C |

| Procyanidin A2 | Procyanidin A2 (PCA2) |

The biosynthetic pathway of SDG from phenylpropanoids is a meticulously coordinated process involving the general phenylpropanoid pathway, stereospecific coupling, sequential reduction, glycosylation, and final oligomerization. A deep understanding of this pathway, including its key enzymes and regulatory mechanisms, provides a solid foundation for future research. This knowledge is pivotal for metabolic engineering strategies aimed at enhancing SDG yield in flaxseed or producing it in heterologous systems. Furthermore, a precise grasp of its biogenesis supports the development of SDG as a nutraceutical for disease prevention, enabling more targeted investigations into its bioavailability, metabolism, and mechanism of action in humans.

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) represents the principal lignan precursor found in flaxseed, constituting approximately 1-4% of its dry weight [17]. As a phytoestrogen, SDG has garnered significant research interest for its potential role in preventing chronic diseases, including cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and hormone-related cancers [18] [17]. However, SDG itself possesses limited bioactivity until it undergoes extensive biotransformation by gut microbiota into the mammalian lignans enterodiol (ED) and enterolactone (EL) [19] [20]. These enterolignans exhibit a spectrum of biological activities, including tissue-specific estrogen receptor activation, anti-inflammatory effects, and antioxidant properties [21] [20]. This whitepaper delineates the intricate microbial metabolic pathways involved in SDG conversion, details critical experimental methodologies for studying these processes, and explores the implications for therapeutic development within disease prevention research.

The Metabolic Pathway of SDG to Enterolignans

The bioconversion of dietary SDG into the bioactive enterolignans ED and EL is a sequential process catalyzed by specific bacterial consortia in the colon. This transformation is critical for unlocking the health-promoting properties associated with flaxseed lignans [20]. The pathway involves four primary enzymatic activities: deglycosylation, demethylation, dehydroxylation, and dehydrogenation [19].

Table 1: Key Enzymatic Steps in SDG Conversion to Enterolignans

| Step | Reaction | Primary Bacterial Catalysts |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Deglycosylation | SDG → Secoisolariciresinol (SECO) | Bacteroides distasonis, Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides ovatus, Clostridium cocleatum [19] |

| 2. Demethylation | SECO → Demethylated intermediates | Butyribacterium methylotrophicum, Eubacterium callanderi, Eubacterium limosum, Peptostreptococcus productus [19] |

| 3. Dehydroxylation | Demethylated SECO → Enterodiol (ED) | Clostridium scindens, Eggerthella lenta [19] |

| 4. Dehydrogenation | ED → Enterolactone (EL) | Newly isolated strain Clostridium sp. ED-Mt61/PYG-s6 [19] |

The entire process is a collaborative effort among phylogenetically diverse gut bacteria, with no single species capable of completing the full pathway independently [19]. The resulting enterolignans, which contain meta-positioned phenolic hydroxyl groups, are structurally distinct from their plant precursors and can be absorbed into the circulation, where they exert systemic effects [22].

The following diagram illustrates the complete metabolic pathway from dietary SDG to the final enterolignans, highlighting the bacterial groups responsible for each transformation step.

Figure 1: Microbial Metabolic Pathway from SDG to Enterolignans. Bacterial groups responsible for each catalytic step are shown in red boxes with white text, connected to their respective reaction steps.

Quantitative Profiling of Lignans and Metabolites

Understanding the concentration ranges of lignans from dietary intake to systemic circulation is fundamental for evaluating their bioactivity and therapeutic potential. The following table summarizes key quantitative data for SDG, its intermediates, and the final enterolignans across different biological matrices.

Table 2: Quantitative Profile of Lignans and Enterolignans in Research

| Analyte | Context / Matrix | Concentration | Significance / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG | Flaxseed Content | 1 - 4% (w/w) [17] | 9 - 30 mg/g, making flaxseed the richest known source [17]. |

| SDG | Human Colonic Lumen | ~666 μM [22] | Estimated from a consumption of 50 g of flaxseed; relevant for local antioxidant effects [22]. |

| ED & EL | Human Plasma | 17 - 519 nM [22] | Range observed in adults after consumption of 25 g of flaxseed [22]. |

| ED & EL | Human Plasma | ~385 nM (Enterolactone) [22] | Level in postmenopausal women after a 500 mg/day SDG supplement [22]. |

| ED & EL | Rat Plasma | ~1 μM [22] | Estimated level in rats dosed with 1.5 mg SDG/day [22]. |

| SDG, SECO, ED, EL | In Vitro Antioxidant Assays | 10 - 1000 μM [22] | Concentrations used to establish efficacy in protecting against DNA nicking and liposome oxidation [22]. |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

1In VitroFermentation Models

In vitro fermentation using human or animal fecal microbiota is a cornerstone technique for studying the kinetics and intermediates of lignan metabolism [20]. The standard protocol involves incubating the lignan source (e.g., purified SDG or flaxseed extract) with fecal slurry in an anaerobic environment to mimic colonic conditions. Samples are collected at timed intervals and analyzed using techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or HPLC coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to quantify the appearance of SECO, ED, EL, and other transient metabolites [20]. This method was pivotal in identifying the 17 different metabolites associated with the colonic metabolism of SECO and in isolating and characterizing the specific bacterial strains involved in each step of the pathway [19] [20].

Animal Models for Efficacy and Mechanistic Studies

Animal studies are indispensable for validating the health effects of SDG and enterolignans and for elucidating their mechanisms of action.

- APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice: A 2024 study utilized 10-month-old female APP/PS1 mice, a model for Alzheimer's disease, to investigate the neuroprotective effects of SDG [3]. Mice were orally administered SDG (70 mg/kg) once daily for 8 weeks. This model was instrumental in demonstrating that SDG's cognitive benefits are mediated through gut microbiota-derived enterolignans, which reduce cerebral β-amyloid deposition and suppress neuroinflammation via the GPER receptor [3].

- Diet-Induced Obese (DIO) Mice: To study metabolic effects, male C57BL/6J mice are fed a high-fat diet (60% energy from fat) for 12 weeks to induce obesity and insulin resistance [23]. Subsequent intervention with SDG (e.g., 10-1000 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks) allows researchers to assess improvements in glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity (via HOMA-IR), and related molecular mechanisms such as the upregulation of GLUT4 expression in adipose tissue and muscle [23].

Analytical Techniques for Quantification

Accurate measurement of lignans and their metabolites is crucial. The most common analytical methods are based on separation techniques:

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Photodiode Array Detection (HPLC-PDA): A standard workhorse for quantifying SDG, SECO, ED, and EL in extracts, foods, and biological fluids after appropriate sample preparation and hydrolysis [17].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): This method, particularly using HPLC-MS, offers higher sensitivity and specificity. It is the preferred technique for quantifying serum levels of END and ENL in complex biological matrices, as demonstrated in the 2024 Alzheimer's disease mouse study [3]. It allows for precise identification and quantification even at low nanomolar concentrations found in plasma.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Studying SDG Metabolism and Bioactivity

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Details & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Purified SDG | Standard for in vitro assays, animal dosing, and analytical calibration. | Isolated from defatted flaxseed meal using solvent extraction (e.g., methanol, dioxane/ethanol) often followed by alkaline hydrolysis [17] [22]. |

| Synthetic ED & EL | Critical positive controls for binding assays, cell culture studies, and analytical reference standards. | Chemically synthesized; used to establish direct effects of enterolignans independent of microbial metabolism [21] [22]. |

| Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Cocktail (ABx) | Tool for gut microbiota depletion to establish its essential role in SDG bioactivation. | Typically contains Penicillin G, metronidazole, neomycin, streptomycin, and gentamicin [3]. |

| GPER Antagonist (G15) | Pharmacological tool to investigate the role of the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor in mediating enterolignan effects. | Used in in vivo models (e.g., via i.c.v. injection) to block GPER signaling and assess its contribution to neuroprotection [3]. |

| Specific Bacterial Strains | For mechanistic studies on specific metabolic steps or probiotic potential. | Includes type strains like Bacteroides fragilis (deglycosylation), Eggerthella lenta (dehydroxylation) [19]. |

| Reporter Gene Assays | To study estrogenic/anti-estrogenic activity and receptor-specific transactivation. | Plasmids expressing ERα, ERβ, or GPER, coupled with luciferase reporters in cell lines like MCF-7 [21]. |

| Prim-O-Glucosylcimifugin | Prim-O-Glucosylcimifugin HPLC|For Research | Prim-O-glucosylcimifugin is a chromone from Saposhnikovia root with anti-inflammatory and anti-aging research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Pseudolaric Acid C | Pseudolaric Acid C, CAS:82601-41-0, MF:C21H26O7, MW:390.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Research Workflow for Establishing Mechanism of Action

A comprehensive research strategy to deconvolute the mechanism of action of SDG and its metabolites, from ingestion to physiological effect, involves a multi-faceted approach. The following diagram outlines the key experimental phases and logical flow, integrating the tools and models previously described.

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Deconvoluting SDG's Mechanism of Action. The workflow progresses through three critical phases: establishing microbial conversion and systemic exposure (Yellow), confirming the necessity of the gut microbiota (Green), and elucidating the molecular targets and pathways (Blue), leading to a validated mechanism (Red).

Implications for Disease Prevention and Therapeutic Development

The generation of ED and EL by gut microbiota is a critical factor underlying the proposed disease-preventive properties of flaxseed. Their structural similarity to estrogens enables them to act as selective estrogen receptor modulators. Research shows that ED and EL have different impacts on ERα transcriptional activation in breast cancer cells, with ED acting as a more potent agonist than EL, which can influence cell proliferation and migration [21]. Beyond hormonal activities, enterolignans exhibit antioxidant properties, protecting against peroxyl radical-induced DNA damage and liposome oxidation at physiologically relevant concentrations (10-100 µM) [22]. Furthermore, SDG supplementation has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice by upregulating GLUT4 expression, an effect likely mediated by its metabolites [23]. Most recently, a 2024 study provided a compelling mechanistic link: in a female Alzheimer's disease mouse model, SDG's cognitive benefits were dependent on gut microbiota-derived ED and ENL, which activated the GPER receptor, leading to enhanced CREB/BDNF signaling and suppressed neuroinflammation [3]. This underscores the gut-brain axis as a novel pathway for lignan action.

In conclusion, the conversion of SDG to ED and EL by a consortium of gut bacteria is a prerequisite for realizing the full health-promoting potential of flaxseed lignans. Future research focusing on optimizing microbial metabolism and understanding individual variations in gut microbiota composition will be vital for developing targeted nutritional strategies and therapeutic interventions for chronic diseases.

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), the principal lignan in flaxseed, exhibits multifaceted biological activities that underpin its potential in disease prevention. As a phytoestrogen, SDG and its mammalian metabolites, enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL), interact with estrogen receptors, modulating hormonal balance. Concurrently, SDG demonstrates potent antioxidant activity through direct free radical scavenging and induction of the endogenous antioxidant response, alongside significant anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing key pro-inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK. This whitepaper synthesizes current mechanistic insights into these core activities, details experimental approaches for their investigation, and contextualizes their integrated role in SDG's potential therapeutic applications against chronic diseases including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and cardiometabolic conditions.

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) is the predominant lignan in flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum), which represents the richest known dietary source, containing levels 40 to 800 times higher than other lignan-containing plants [12] [14]. In the plant, SDG biosynthesis proceeds through the phenylpropanoid pathway, beginning with phenylalanine. Key steps include the stereospecific coupling of two coniferyl alcohol molecules by dirigent proteins to form pinoresinol, its subsequent reduction to secoisolariciresinol (SECO) by pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase (PLR), and final glycosylation by UDP-dependent glucosyltransferases (UGTs) to produce SDG [14] [24].

Upon human ingestion, SDG is not absorbed directly but undergoes extensive microbial metabolism in the colon. Gut microbiota sequentially deglycosylate SDG to SECO and then convert it to the mammalian lignans enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL) [12] [25]. These metabolites bear structural similarity to endogenous estradiol, allowing them to bind estrogen receptors and function as phytoestrogens [12]. The production and eventual systemic absorption of END and ENL are crucial for the biological activities of dietary SDG.

Phytoestrogenic Activity and Hormonal Modulation

Molecular Mechanisms of Estrogen Receptor Interaction

The phytoestrogenic activity of SDG is primarily mediated by its enterolignan metabolites, END and ENL. Their diphenolic structure closely mimics that of 17β-estradiol, enabling binding and activation of estrogen receptors (ERs) [12] [25]. A key mechanistic aspect is their selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)-like activity. ENL exhibits a higher binding affinity for ERβ compared to ERα [25]. Since ERβ activation is often associated with anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in certain tissues, this selectivity may explain the observed protective effects against hormone-dependent cancers without the proliferative risks associated with ERα activation.

Recent research has highlighted the role of the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) in mediating SDG's effects. A 2024 study demonstrated that SDG's cognitive benefits in a female Alzheimer's disease mouse model were abolished upon inhibition of GPER, indicating this receptor's critical role in transmitting neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory signals [3].

Gene Regulation and Therapeutic Applications

The activation of estrogen receptors by enterolignans modulates the transcription of genes controlled by Estrogen Response Elements (EREs). This includes genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism [12]. SDG has shown significant potential in ameliorating conditions related to estrogen deficiency.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for SDG's Phytoestrogenic Activity

| Experimental Model | Intervention | Key Findings | Mechanistic Insights | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POI Mouse Model | SDG (50, 100, 200 mg/kg) for 4 weeks | Improved ovarian index, increased follicle count, reduced ovarian damage | Activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway; molecular docking confirmed high affinity for Akt1 and PI3Kγ | [8] |

| Female APP/PS1 AD Mouse Model | SDG (70 mg/kg) for 8 weeks | Ameliorated cognitive deficits, enhanced CREB/BDNF signaling | Effects required gut microbiota conversion to END/ENL and were mediated by GPER | [3] |

| Ovariectomized Mice (Postmenopausal Model) | SDG supplementation | Alleviated depressive-like behavior, inhibited neuroinflammation | Phytoestrogenic and anti-inflammatory properties; promoted BDNF expression | [3] |

Antioxidant Activity: Direct and Indirect Mechanisms

Direct Free Radical Scavenging

SDG and its metabolites function as potent direct reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavengers. Their chemical structure, characterized by multiple phenolic hydroxyl groups, allows them to donate electrons and neutralize free radicals such as superoxide anion (O₂•â») and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) [25]. In vitro evidence suggests that SDG's free radical scavenging efficiency can surpass that of classic antioxidants like ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and α-tocopherol (vitamin E) [26].

Induction of the Endogenous Antioxidant Response

Beyond direct scavenging, SDG activates the Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) pathway, a master regulator of cellular defense against oxidative stress. Upon activation, Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), promoting the transcription of a battery of cytoprotective genes [25]. Key enzymes upregulated by SDG via this pathway include:

- Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1): An enzyme with potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [25].

- Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and Catalase (CAT): Fundamental enzymes that catalyze the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, and the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water, respectively [25].

This dual mechanism—direct scavenging and Nrf2-mediated gene induction—underpins SDG's efficacy in reducing markers of oxidative damage like malondialdehyde (MDA) while boosting levels of endogenous antioxidants like glutathione in tissues such as liver and kidney [25].

Table 2: Quantified Antioxidant Effects of SDG and Related Lignans

| Assay/Model | Lignan Tested | Quantitative Outcome | Significance/Implication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro free radical scavenging | SDG | Higher efficiency than ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol | Potent direct antioxidant capability | [26] |

| Mouse liver/kidney damage models | SDG | ↑ SOD, CAT activity; ↑ Glutathione; ↓ MDA | Activates endogenous defense systems and reduces lipid peroxidation | [25] |

| RAW264.7 macrophage cells | (+)-Lariciresinol | ↑ Nrf2-induced HO-1 expression | Specific enantiomers can activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway | [25] |

| Flaxseed processing study | SDG from processed flaxseed | Increased antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP assays) | Processing (microwave, germination) can enhance lignan content and activity | [6] |

Anti-inflammatory Activity: Targeting Core Signaling Pathways

Suppression of NF-κB and MAPK Signaling

Chronic inflammation is driven by the sustained activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors, and SDG directly targets their upstream pathways. SDG and its metabolites inhibit the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which is responsible for phosphorylating and targeting the inhibitory protein IκB for degradation. This prevents the release and nuclear translocation of the NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 [25]. Consequently, the transcription of NF-κB target genes, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, COX-2, and iNOS, is significantly downregulated [25] [26].

Parallel to NF-κB inhibition, SDG suppresses the MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase) pathway. It reduces the phosphorylation of key MAPKs—p38, JNK, and ERK—which in turn diminishes the activation of the transcription factor AP-1, a key regulator of inflammation and cellular proliferation [25].

Modulation of Cellular Adhesion and Migration

The anti-inflammatory effects of SDG extend to the cellular level, particularly in the context of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and neuroinflammation. SDG treatment of primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) downregulates the surface expression of VCAM-1 (Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1), a critical protein for leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium [26]. Simultaneously, SDG reduces the active conformation of the VLA-4 integrin on the surface of human monocytes, the cognate ligand for VCAM-1 [26]. This dual action disrupts the firm adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium, a key step in inflammation, thereby reducing their migration into tissues, as demonstrated in models of aseptic encephalitis [26].

Diagram 1: SDG modulation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. SDG inhibits key activation steps triggered by inflammatory stimuli, ultimately reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Core Activities

This section provides standardized methodologies for evaluating the core biological activities of SDG in a research setting.

Protocol: Evaluating Anti-inflammatory Activity via Monocyte-BMVEC Adhesion

This assay quantifies SDG's effect on a key step in neuroinflammation [26].

Key Research Reagents:

- Primary Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (BMVEC): Isolated from normal brain resection tissue.

- Primary Human Monocytes: Isolated from healthy donors via counter-current centrifugal elutriation.

- SDG: Chemically synthesized, reconstituted in sterile water or saline.

- Recombinant Human TNF-α: For inflammatory stimulation.

- Calcein-AM: Fluorescent dye for monocyte labeling.

- Flow Cytometry Equipment & Antibodies: For analyzing VCAM-1 expression and VLA-4 activation.

Methodology:

- Cell Pretreatment: Pre-treat BMVEC monolayers and/or monocytes with SDG (e.g., 1-50 μM) for 1 hour.

- Inflammatory Stimulation: Stimulate BMVEC with TNF-α (20 ng/mL) for 16 hours to upregulate adhesion molecules.

- Monocyte Labeling: Label pretreated monocytes with Calcein-AM.

- Adhesion Assay: Add labeled monocytes to BMVEC monolayers, incubate to allow adhesion, and wash off non-adherent cells.

- Quantification: Measure fluorescence of adherent monocytes using a plate reader. Express data as fold change compared to unstimulated controls.

- Mechanistic Analysis: Analyze VCAM-1 surface expression on BMVEC and active VLA-4 integrin on monocytes using flow cytometry.

Protocol: Assessing Phytoestrogenic Activity via POI Mouse Model

This in vivo protocol evaluates SDG's potential in treating Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI), linking hormonal regulation to a specific molecular pathway [8].

Key Research Reagents:

- C57BL/6 Mice: Typically 6-week-old females.

- Cyclophosphamide (CTX) & Busulfan (BU): For chemotherapy-induced POI model.

- SDG: Administered via oral gavage at 50, 100, 200 mg/kg doses.

- Antibodies for Western Blot: Phospho-Akt (T40067) and total Akt (T55561).

- Molecular Docking Software: AutoDock Vina, PyMOL for target interaction analysis.

Methodology:

- POI Model Induction: Administer a single intraperitoneal injection of CTX (120 mg/kg) and BU (30 mg/kg) to mice.

- SDG Treatment: Commence SDG treatment via daily gavage for 4 weeks post-model induction.

- Tissue Collection: Sacrifice mice, record body and ovarian weights. Calculate relative ovarian weight.

- Ovarian Morphology: Fix ovaries, section, and perform H&E staining for follicle counting and classification.

- Mechanistic Validation:

- Network Pharmacology & Transcriptomics: Identify potential targets (e.g., PI3K/Akt pathway) from GEO datasets (e.g., GSE128240).

- Western Blot: Analyze PI3K/Akt pathway protein phosphorylation in ovarian tissue or KGN cells.

- Molecular Docking & Dynamics: Validate high-affinity binding of SDG to identified targets like Akt1 and PI3Kγ.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for evaluating SDG's phytoestrogenic activity in a POI model. The approach integrates phenotypic assessment with multi-level mechanistic validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SDG Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specific Function/Example | Application in SDG Research |

|---|---|---|

| KGN Human Granulosa Cell Line | Model for ovarian granulosa cell function; expresses functional FSHR. | Used to study SDG's protective effects against CTX-induced cytotoxicity and its impact on PI3K/Akt signaling [8]. |

| Primary Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (BMVEC) | Constitute the blood-brain barrier (BBB). | Essential for in vitro models studying SDG's barrier-protective and anti-inflammatory effects in neuroinflammation (e.g., adhesion/migration assays) [26]. |

| Primary Human Monocytes | Key immune effector cells in inflammatory responses. | Used to study SDG's direct effect on leukocyte activation, integrin conformation (VLA-4), and cytoskeletal rearrangements [26]. |

| APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice | Common model of Alzheimer's disease pathology (Aβ deposition). | Used to investigate SDG's neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and cognitive-enhancing effects in a female AD context [3]. |

| Recombinant Human TNF-α & IL-1β | Pro-inflammatory cytokines. | Used to stimulate inflammatory responses in in vitro (BMVEC, monocytes) and in vivo (aseptic encephalitis) models [26]. |

| Antibody: Anti-phospho-Akt | Detects activated (phosphorylated) Akt. | Critical for validating SDG's activation of the PI3K/Akt survival pathway in POI and other disease models [8]. |

| Antibody: HUTS-21 (Anti-active VLA-4) | Specifically recognizes the active conformation of VLA-4 integrin. | Used in flow cytometry to demonstrate SDG's ability to suppress monocyte adhesiveness [26]. |

| GPER Antagonist (G15) | Selective inhibitor of the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor. | Used to confirm the role of GPER in mediating the neuroprotective effects of SDG and its metabolites [3]. |

| Psoralen | Psoralen | |

| Isoquercetin | Isoquercetin |

The core biological activities of SDG—its phytoestrogenic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms—are deeply interconnected. The antioxidant activity mitigates oxidative stress, a key driver of inflammation; the anti-inflammatory activity suppresses NF-κB and MAPK pathways, which are implicated in chronic disease and cancer progression; and the phytoestrogenic activity, mediated by gut-derived metabolites, provides a nuanced regulatory layer over hormonal and inflammatory processes. The convergence of these activities on shared molecular targets, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway, underscores SDG's potential as a multi-target therapeutic agent.

Future research should prioritize the clinical translation of these mechanistic findings. This includes:

- Conducting human trials with well-defined SDG formulations to validate efficacy on biochemical and clinical endpoints.

- Further elucidating the role of the gut microbiome in modulating SDG's efficacy through personalized metabolite production.

- Exploring the synergistic effects of SDG with other bioactive compounds or existing therapeutics.

- Developing advanced delivery systems to enhance the bioavailability of SDG and its active metabolites to target tissues.

The robust foundational knowledge of SDG's core mechanisms, as detailed in this whitepaper, provides a strong rationale for its continued investigation as a promising candidate in the strategy for preventing and managing chronic diseases.

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), the primary lignan in flaxseed, is a phytoestrogen whose biological activity is largely dependent on its conversion by gut microbiota into the mammalian lignans enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL). A growing body of preclinical evidence demonstrates that SDG and its metabolites exert protective effects against a spectrum of diseases, including neurodegenerative, metabolic, and hormonal disorders, as well as cancer. These benefits are mediated through interactions with specific cellular receptors and the modulation of key signaling pathways. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical synthesis of SDG's molecular targets, focusing on its agonistic activity on the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) and its potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects via the NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways, respectively. The document is structured to serve researchers and drug development professionals by summarizing quantitative data, detailing experimental protocols, and visualizing the core signaling mechanisms.

G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor (GPER) Agonism

SDG's structural similarity to estradiol enables its classification as a phytoestrogen. Its neuroprotective effects, particularly in the context of Alzheimer's Disease (AD), are significantly mediated through the activation of GPER, a transmembrane estrogen receptor highly expressed in the brain [27].

Experimental Evidence and Workflow

A seminal study investigating SDG's effects in a female AD mouse model (APP/PS1) provides a clear experimental workflow and mechanistic insight [27].

- In Vivo Model: 10-month-old female APP/PS1 transgenic mice were treated with SDG (70 mg/kg, oral gavage) daily for 8 weeks.

- Cognitive Assessment: Behavioral tests (e.g., Morris water maze, Y-maze) demonstrated that SDG significantly improved spatial, recognition, and working memory.

- Metabolite Analysis: Serum levels of the gut microbiota-derived metabolites END and ENL were quantified using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS). SDG administration increased these levels.

- Microbiome Dependency: Broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail (ABx) treatment to deplete gut microbiota inhibited the production of END and ENL and abolished the cognitive benefits of SDG, establishing a causal link.

- Receptor Antagonism: In a separate acute neuroinflammation model induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of the GPER-specific antagonist G15 eliminated the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of SDG.

This workflow confirms that the gut metabolites END and ENL are the primary agonists that activate GPER in the brain, leading to downstream neuroprotective signaling.

Downstream Signaling and Pathological Outcomes

Activation of GPER by SDG's metabolites initiates a signaling cascade that addresses core pathologies of AD [27]:

- Enhanced CREB/BDNF Pathway: GPER activation leads to the upregulation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which are critical for neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity.

- Increased Synaptic Density: Expression of postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95) was enhanced, indicating improved synaptic integrity.

- Reduced Amyloid Burden: Hippocampal β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition was significantly decreased.

- Suppressed Neuroinflammation: Levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) in the cortex were reduced.

The following diagram illustrates this central signaling pathway and its physiological consequences.

Modulation of Key Signaling Pathways: NF-κB and Nrf2

Beyond receptor agonism, SDG and its metabolites directly modulate intracellular signaling pathways central to inflammation and oxidative stress, which are hallmarks of numerous chronic diseases.

Nuclear Factor Kappa-B (NF-κB) Pathway Inhibition

SDG exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects primarily through the suppression of the NF-κB pathway. This has been demonstrated in models of breast cancer and neuroinflammation.

- In Vivo Evidence (Breast Cancer): In C57BL/6 mice bearing E0771 triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tumors, dietary supplementation with SDG (100 mg/kg diet) significantly reduced tumor volume and was associated with decreased phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB and reduced expression of NF-κB target genes [28].

- In Vitro Confirmation: Treatment of human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7) with the bioactive SDG metabolite ENL inhibited cell viability, survival, and NF-κB activity. Critically, overexpression of Rela (which encodes p65) attenuated ENL's anti-proliferative effects, confirming NF-κB inhibition as a core mechanism [28].

- Upstream Trigger: The anti-inflammatory effect can also be initiated by mitigating gut dysbiosis. SDG helps maintain intestinal barrier integrity, reducing the translocation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS). LPS is a known ligand for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a key activator of the NF-κB pathway [1] [27].

Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) Pathway Activation

The activation of the Nrf2 pathway is a fundamental mechanism by which SDG and other lignans counteract oxidative stress. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to its cytoplasmic repressor, Keap1, and targeted for degradation. SDG facilitates the dissociation and stabilization of Nrf2 [29].

- Mechanism: SDG and its metabolites promote the dissociation of Nrf2 from Keap1. Nrf2 then translocates to the nucleus, binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), and drives the transcription of a battery of cytoprotective genes.

- Key Enzymes: Target genes include heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and enzymes involved in glutathione (GSH) synthesis [30] [29].

- Functional Output: The concerted action of these enzymes enhances the cell's ability to detoxify reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduce oxidative damage. This Nrf2-mediated antioxidant activity has been documented in experimental models of asbestos-induced toxicity and various other diseases [30] [29].

The interplay between SDG's inhibition of NF-κB and activation of Nrf2 creates a powerful cellular defense network, as visualized below.

The PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway

Network pharmacology and transcriptome analysis have uncovered the PI3K/Akt pathway as another critical target for SDG, particularly in the context of ovarian health [8].

- Experimental Context: A study on a mouse model of cyclophosphamide (CTX)-induced premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) found that SDG treatment (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) significantly improved ovarian indices and follicle counts.

- Mechanistic Validation: Combined network pharmacology prediction and experimental validation in human granulosa cell line (KGN) showed that SDG protected against CTX-induced damage by modulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Molecular docking studies confirmed a high binding affinity of SDG for both Akt1 and PI3Kγ, pinpointing specific interaction sites [8].

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Findings on SDG's Molecular Interactions

| Model System | SDG Treatment | Molecular Target / Pathway | Key Measured Outcomes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female APP/PS1 AD Mice | 70 mg/kg, oral, 8 weeks | GPER / CREB / BDNF | ↑ BDNF, ↑ PSD-95; ↓ Aβ deposition, ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 | [27] |

| E0771 TNBC Mouse Model | 100 mg/kg diet, 3 weeks | NF-κB | ↓ Tumor volume; ↓ p-p65, ↓ NF-κB target genes | [28] |

| CTX-induced POI Mouse Model | 50-200 mg/kg, oral, 4 weeks | PI3K/Akt | ↑ Ovarian index, ↑ follicle count; Activation of PI3K/Akt in KGN cells | [8] |

| Asbestos-exposed Macrophages (Wild-type vs Nrf2-/-) | 50-100 µM LGM2605 (synthetic SDG) | Nrf2 / HO-1 | Attenuated cytotoxicity & ROS; ↑ HO-1, NQO1 (in WT only) | [30] |

| HUA Mouse Model | 40-160 mg/kg, oral, 7 days | Gut Microbiota → Inflammation | ↓ Serum uric acid; ↓ LPS, TNF-α, IL-6; Modulated UA transporters | [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Models for Investigating SDG Mechanisms

| Reagent / Model | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Disease Models | APP/PS1 transgenic mice; CTX-induced POI mice; E0771 TNBC orthotopic model; PO/hypoxanthine-induced HUA mice | Modeling human diseases (AD, ovarian failure, cancer, hyperuricemia) for efficacy and mechanism testing. |

| Cell Lines | KGN (human granulosa cells); MDA-MB-231 (TNBC); MCF-7 (Luminal A BC); E0771 (murine TNBC); primary murine macrophages | In vitro validation of signaling pathways, cell proliferation, and survival. |

| Key Inhibitors / Modulators | G15 (GPER antagonist); ABx (broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail); LPS (TLR4/NF-κB activator) | Establishing causal links by blocking specific receptors, depleting gut microbiota, or inducing inflammation. |

| Analytical Techniques | HPLC-MS/MS; Western Blot; qRT-PCR; Immunohistochemistry; Molecular Docking & Dynamics | Quantifying metabolites (END/ENL), measuring protein/gene expression, and predicting ligand-target interactions. |

| Synthetic SDG | LGM2605 | A well-characterized, synthetic version of SDG used for standardized interventional studies. |

| Hyperoside | Hyperoside, CAS:482-36-0, MF:C21H20O12, MW:464.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rhamnetin | Rhamnetin |

The multifaceted disease-preventive potential of secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) is rooted in its pleiotropic interactions with specific molecular targets. The core mechanisms elucidated in this whitepaper include its action as a phytoestrogen via GPER agonism to confer neuroprotection, its potent anti-inflammatory activity through NF-κB pathway suppression, and its activation of the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defense system. Emerging evidence further implicates the PI3K/Akt pathway in its protective effects on ovarian function. A critical and non-negotiable factor for the efficacy of orally administered SDG is its bioconversion by the gut microbiome into the active mammalian lignans enterodiol and enterolactone. Future research, leveraging the reagents and methodologies outlined in the "Scientist's Toolkit," should focus on translating these robust preclinical findings into targeted therapeutic and nutraceutical strategies for human health.

From Bench to Bedside: Analytical Methods and Therapeutic Application Models

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) is the principal lignan found in flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) and has attracted significant scientific interest due to its proven role in disease prevention. SDG exhibits a range of pharmacological activities, including anticancer, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and cholesterol-lowering effects, positioning it as a promising candidate for nutraceutical and pharmaceutical development [31] [32]. The compound exists in the flaxseed hull bound in complex oligomeric structures ester-linked to hydroxymethyl glutaric acid [31]. This technical guide provides an in-depth review of contemporary techniques for the efficient extraction, isolation, and quantification of SDG, framed within the context of its application in disease prevention research for a scientific audience.

SDG Biosynthesis and Chemical Structure

In flaxseed, SDG is not present in its free form but is part of a complex macromolecule. The biosynthesis involves the polymerization of coniferyl alcohol, leading to structures like pinoresinol, which are subsequently reduced and glucosylated [7]. The final FLM consists of SDG units connected through 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid (HMGA) residues and may also include ester-linked glucosylated derivatives of hydroxycinnamic acids, such as ferulic acid glycoside (FerAG) and p-coumaric acid glycoside (CouAG) [33] [7]. The presence of these phenolic acids contributes to the overall antioxidant capacity of the macromolecule [33]. Alkaline hydrolysis is required to cleave these ester bonds and release the free SDG lignan [31].

Diagram 1: Biosynthetic pathway of flaxseed lignan macromolecules (FLM).

Extraction and Isolation Techniques

The extraction of SDG from flaxseed involves two critical steps: liberation from the complex polymer and isolation from the crude extract.

One-Pot Hydrolysis and Extraction

Traditional methods involve sequential solvent extraction and alkaline hydrolysis. However, a more efficient one-pot reaction using alcoholic ammonium hydroxide has been developed, which simultaneously hydrolyzes the ester bonds and extracts SDG [31]. Ammonium hydroxide is preferred over stronger alkalis like sodium hydroxide due to its weak alkalinity, which is less damaging to the glycosidic bonds and is more environmentally friendly, as the waste stream can be repurposed as fertilizer [31].

Optimized conditions for this method, as determined by response surface methodology, are summarized in Table 1 [31].

Table 1: Optimized conditions for one-pot SDG extraction using alcoholic ammonium hydroxide.

| Extraction Parameter | Optimized Condition |

|---|---|

| Flaxseed hull particle size | Crushed (20 mesh) |

| Material-liquid ratio | 1:20 |

| Ammonium hydroxide concentration | 33.7% (v/v, of reagent NHâ‚„OH in ethanol) |

| Extraction temperature | 75.3 °C |

| Extraction time | 4.9 hours |

| Reported SDG yield | 23.3 mg/g of flaxseed hull |

Purification and Isolation

Following extraction, the crude SDG requires purification. This is typically achieved through a sequence of chromatographic steps:

- Macroporous Resin Chromatography: Effectively enriches SDG from the crude extract. A single run on a resin such as AB-8 can yield a fraction with an SDG content exceeding 76% [31] [1].

- Sephadex LH-20 Chromatography: Further purifies the enriched fraction, yielding SDG with a purity of 98% [31].

Alternative and Pre-Treatment Methods

Other approaches include:

- Solvent Extraction: Using aqueous alcohols (e.g., 80% methanol) followed by alkaline hydrolysis (e.g., with 20 mM NaOH at 50°C for 12 hours) to release SDG from the polymer [6].

- Physical and Biological Pre-Treatments: Microwave irradiation and germination have been shown to increase the lignan content and alter its spatial distribution in flaxseed, potentially enhancing extractability [6]. Microwave treatment at 130 W for 10-14 seconds, applied before or after germination, can significantly boost SDG levels and antioxidant activity [6].

Analysis and Quantification of SDG

Accurate quantification of SDG is essential for standardization and research. The established method involves Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC or HPLC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS).

UHPLC-MS Methodology

A detailed protocol for SDG quantification is as follows [31] [6]:

- Equipment: UHPLC system coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

- Chromatographic Column: Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 (2.1 mm × 50 mm; particle size, 1.8 μm) or equivalent (e.g., BEH Shield RP18).

- Mobile Phase: A) 0.1% formic acid in water; B) Methanol.

- Gradient Elution:

- 0 min: 10% B

- 4 min: 100% B

- 6 min: 100% B

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 30 °C

- Injection Volume: 1 μL

- MS Detection: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) in negative ion mode.

- Ion Transitions: Multiple-Reaction Monitoring (MRM) of the transition from precursor ion

m/z 685to product ionm/z 361. - Calibration: A linear calibration curve (

Y = 65.98x + 6.44, R² = 0.9997) is constructed using SDG standards in the range of 0.0015 - 50 μg/mL [31].

Table 2: Key parameters for the UHPLC-MS/MS quantification of SDG.

| Analysis Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Chromatography Technique | Reversed-Phase UHPLC |

| Detection Method | Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) |

| Ionization Mode | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Negative |

| Quantification Mode | Multiple-Reaction Monitoring (MRM) |

| Precursor Ion (m/z) | 685 [M-H]â» |

| Product Ion (m/z) | 361 |

| Linear Range | 0.0015 - 50 μg/mL |

Diagram 2: Workflow for the extraction and quantification of SDG from flaxseed.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for SDG extraction and analysis.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Flaxseed Hull | Primary source material for SDG extraction. | Defatted, crushed to 20 mesh [31]. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide | Alkaline reagent for one-pot hydrolysis and extraction. | 25-28% NH₃ in water [31]. |

| Ethanol / Methanol | Solvent for extraction. | Aqueous solutions (e.g., 80% methanol) [6]. |

| Macroporous Resin | Primary purification step to enrich SDG content. | AB-8, D101, or equivalent [31] [1]. |

| Sephadex LH-20 | Size-exclusion chromatography for high-purity isolation. | For final purification to >98% purity [31]. |

| SDG Reference Standard | Essential for method validation and calibration. | Chromatographic grade, purity ≥97% [6]. |

| C18 UHPLC Column | Core component for chromatographic separation. | 2.1 x 50 mm, 1.8 μm particle size [31]. |

| Salidroside | Salidroside | |

| Salvianolic acid C | Salvianolic acid C, CAS:115841-09-3, MF:C26H20O10, MW:492.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The interest in SDG extraction and analysis is driven by its significant role in preventing chronic diseases. SDG itself, and its mammalian metabolites enterodiol (ED) and enterolactone (EL), are central to its mechanism of action.

Diagram 3: Metabolic activation and disease prevention mechanisms of SDG.

- Metabolic Activation: Upon ingestion, SDG is metabolized by the gut microbiota into the mammalian lignans enterodiol (ED) and enterolactone (EL), which are structurally similar to estradiol and act as phytoestrogens [7]. These enterolignans are absorbed and distributed throughout the body.

- Key Biological Activities:

- Anticancer: SDG and its metabolites exhibit chemopreventive effects against hormone-related cancers (e.g., breast, prostate) by binding to estrogen receptors and exerting both estrogenic and anti-estrogenic effects depending on the physiological context [31] [32]. They also influence apoptosis and cell proliferation.

- Antioxidant: SDG is a potent scavenger of free radicals, preventing lipid peroxidation and protecting cellular components from oxidative damage, a key pathway in chronic disease development [7].

- Anti-inflammatory: SDG modulates inflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 [1] [7].

- Metabolic Syndrome Management: Recent research demonstrates that SDG can alleviate hyperuricemia in mice by regulating key uric acid transporters (URAT1, GLUT9, ABCG2) in the kidneys and intestine, and by restoring a healthy gut microbiota composition [1]. Its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties also contribute to protecting against diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [31] [32] [7].

The extraction of high-purity SDG is achievable through optimized techniques like one-pot alcoholic ammonium hydroxide hydrolysis, followed by chromatographic purification. Its accurate quantification relies on robust UHPLC-MS/MS methodologies. These technical protocols are fundamental for producing standardized SDG for research, ultimately enabling a deeper understanding of its multifaceted role in preventing a spectrum of chronic diseases, from cancer and cardiovascular ailments to metabolic disorders like hyperuricemia. Future research should focus on scaling these extraction methods and further elucidating the molecular pathways through which SDG and its metabolites exert their health-promoting effects.

Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), the principal lignan in flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum), has emerged as a promising nutraceutical compound with documented efficacy in disease prevention models. This technical review provides a comprehensive analysis of SDG incorporation into functional food matrices, addressing critical considerations regarding chemical stability, bioavailability, and analytical quantification. Within the context of preventive health research, we detail SDG's multifaceted bioactivities—including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and metabolic regulatory properties—and provide standardized methodologies for evaluating its stability and bioactivity in food systems. The integration of SDG into mainstream food products represents a strategic approach for developing evidence-based functional foods targeting chronic disease mitigation.

SDG is a dibenzylbutane-type lignan found predominantly in flaxseed, where it exists in an oligomeric structure linked via hydroxy-methyl glutaric acid [34]. As the richest source of SDG, flaxseed contains approximately 77-209 mg per tablespoon of whole seed [35]. Upon ingestion, SDG undergoes microbial metabolism in the colon to form the mammalian lignans enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL), which exhibit structural similarity to endogenous estrogens and demonstrate multiple bioactivities relevant to disease prevention [12] [36].

The disease-preventive potential of SDG spans multiple physiological systems. Experimental models have demonstrated protective effects against cardiovascular disease through reduction of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis [4], anti-cancer activity particularly in hormone-sensitive cancers [34] [12], and anti-diabetic effects through improvement of metabolic parameters [34]. More recent investigations have revealed novel therapeutic applications, including neuroprotective effects through blood-brain barrier protection [26] and anti-hyperuricemic activity via modulation of uric acid metabolism and intestinal homeostasis [1].

Chemical Properties and Stability Profile of SDG

Fundamental Chemical Characteristics

SDG (C₃₂H₄₆Oâ‚₆, molecular weight 686.7 g/mol) is a glycosylated lignan comprising secoisolariciresinol aglycone with two glucose moieties [4]. This molecular configuration significantly influences its solubility, stability, and bioavailability. The compound exists as enantiomers, with the (+) enantiomer predominating in Linum usitatissimum [34].

Key stability considerations:

- Thermal stability: SDG demonstrates moderate heat tolerance but degrades at temperatures exceeding 120°C during processing

- pH sensitivity: Glycosidic bonds are susceptible to acidic hydrolysis, necessitating protective strategies in low-pH food systems

- Oxidative vulnerability: Phenolic structures are prone to oxidation, particularly in powdered formulations with high surface area

Analytical Quantification Methods

Accurate quantification of SDG in food matrices requires specialized analytical approaches:

Extraction Protocol [4]:

- Defatting: Initial hexane extraction of oil-rich matrices

- Solvent extraction: Water/acetone mixture (typically 70:30 v/v)

- Alkaline hydrolysis: NaOH (0.1-1M) to liberate SDG from oligomeric complexes

- Purification: Solid-phase extraction or preparative chromatography

Chromatographic Analysis:

- HPLC conditions: Reverse-phase C18 column, mobile phase water-acetonitrile gradient, detection at 280 nm

- LC-MS confirmation: MRM transitions 687→463 [M+H]⺠for quantification

Table 1: SDG Content in Selected Food Sources

| Source | SDG Content (mg/100g) | Additional Lignans |

|---|---|---|

| Flaxseed | 323.6 | Matairesinol, pinoresinol, lariciresinol |

| Sesame seeds | 0.014 | Sesamin, sesamolin |

| Rye | 0.038 | Hydroxymatairesinol |

| Barley | 0.030 | Lariciresinol |

| Pumpkin seeds | 0.971 | Pinoresinol |

SDG Biosynthesis and Metabolic Pathways

The biosynthetic pathway of SDG in flaxseed involves multiple enzymatic steps, beginning with the phenylpropanoid pathway and proceeding through stereospecific coupling and glycosylation reactions [34]. Understanding this pathway is crucial for biotechnological production approaches.

Figure 1: SDG Biosynthetic Pathway in Flaxseed. Key enzymes: PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase), C4H (cinnamate 4-hydroxylase), Dirigent (dirigent protein), PLR (pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase), UGT (UDP-glucosyltransferase, specifically UGT74S1).

Post-ingestion metabolism transforms SDG into bioactive mammalian lignans through microbial action in the colon [36]:

Figure 2: SDG Metabolic Pathway in Mammalian Systems. SDG is sequentially transformed by gut microbiota into the bioactive mammalian lignans enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL), which are absorbed and conjugated in the liver before systemic distribution.

Disease Prevention Mechanisms: Evidence from Experimental Models

Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities

SDG demonstrates potent free radical scavenging capacity, exceeding the efficiency of ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol in comparative assays [26]. The compound attenuates respiratory bursts in activated macrophages and induces the endogenous antioxidant response (EAR) pathway [26].

Neuroinflammatory Protection: SDG (4 mg/mouse, oral administration) significantly diminished leukocyte adhesion and migration across the blood-brain barrier in murine models of aseptic encephalitis induced by intracerebral TNFα injection [26]. The mechanism involves downregulation of VCAM-1 expression in brain microvascular endothelial cells and reduction of VLA-4 integrin activation in monocytes.

Experimental Protocol - In Vitro BBB Model [26]:

- Cell culture: Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC)

- Treatment: SDG (1-50 μM) 1h prior to TNFα (20 ng/mL) or IL-1β (100 ng/mL) stimulation

- Adhesion assay: Calcein-AM labeled monocytes, fluorescence quantification

- Analysis: Flow cytometry for VCAM-1 expression, cytoskeletal rearrangements

Metabolic Regulation and Hyperuricemia Management

Recent evidence demonstrates SDG's efficacy in alleviating hyperuricemia (HUA) via dual mechanisms [1]:

Hepatic enzyme modulation: SDG treatment (25-100 mg/kg) significantly reduced hepatic xanthine oxidase (XOD) and adenosine deaminase (ADA) activities in potassium oxonate-induced HUA mice, decreasing uric acid production.

Transport protein regulation: SDG upregulated intestinal ABCG2 and GLUT9 expression, enhancing renal and intestinal uric acid excretion.

Table 2: SDG Efficacy in Hyperuricemic Mouse Model

| Parameter | Model Group | SDG 100 mg/kg | Allopurinol 5 mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Uric Acid (μmol/L) | 358.7 ± 42.3 | 198.4 ± 35.2* | 172.6 ± 28.9* |

| Hepatic XOD (U/mg prot) | 4.21 ± 0.52 | 2.38 ± 0.41* | 2.05 ± 0.37* |

| Hepatic ADA (U/mg prot) | 3.87 ± 0.48 | 2.16 ± 0.39* | 1.94 ± 0.32* |

| Renal URAT1 protein | 2.45 ± 0.31 | 1.52 ± 0.28* | 1.61 ± 0.29* |

| Intestinal ABCG2 protein | 0.58 ± 0.12 | 1.27 ± 0.21* | 1.09 ± 0.18* |

Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to model group

Hormone-Modulating and Chemopreventive Activities

SDG's structural similarity to endogenous estrogens enables modulation of hormonal pathways, particularly in hormone-sensitive cancers [12]. The mammalian metabolites END and ENL compete with estradiol for binding to estrogen receptors, exerting both agonist and antagonist effects dependent on hormonal context [12] [36].

Experimental Evidence: SDG administration (500 ppm in diet) significantly reduced human breast cancer (MCF-7) tumor growth in athymic mice by approximately 40-50% compared to controls [4]. The proposed mechanisms include induction of apoptosis, inhibition of angiogenesis, and modulation of estrogen receptor signaling.

Formulation Strategies for Functional Food Applications

Matrix Selection and Compatibility

Successful SDG incorporation requires careful matrix matching based on chemical compatibility:

Ideal food vehicles:

- Baked goods: Whole grain breads, muffins, crackers (thermal processing optimization required)

- Cereal systems: Ready-to-eat cereals, granola, muesli bars

- Meat analogs: Plant-based meat extenders (compatibility with high-protein matrices)