Validating Dietary Biomarkers: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the validation of dietary biomarkers, a critical frontier in nutrition science and clinical research.

Validating Dietary Biomarkers: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the validation of dietary biomarkers, a critical frontier in nutrition science and clinical research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, cutting-edge methodologies, and real-world applications. We explore the pressing need to overcome the limitations of self-reported dietary data and detail the multi-phase validation frameworks employed by major initiatives like the Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC). The content covers the discovery of novel biomarkers through metabolomics, addresses key challenges in deployment and optimization, and establishes rigorous criteria for analytical and biological validation. By integrating insights from recent controlled feeding trials, large-scale observational studies, and regulatory perspectives, this resource serves as a guide for the development and application of objective dietary exposure tools to advance precision nutrition and elucidate diet-disease relationships.

The Critical Need and Current Landscape of Dietary Biomarkers

Accurate dietary assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology, essential for investigating the links between diet and chronic diseases. However, the field has long been plagued by a fundamental limitation: systematic errors inherent in self-reported dietary data. Unlike random errors that can be mitigated through repeated measurements, systematic errors introduce non-random bias that distorts the true diet-disease relationship and compromises the validity of research findings [1]. These errors stem from the reliance on self-report instruments such as Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour recalls, and diet diaries, which are susceptible to misreporting influenced by factors including body mass index, social desirability, and memory limitations [2] [1].

The first law of thermodynamics provides a scientific basis for identifying these systematic errors. This principle states that energy intake equals energy expenditure plus or minus changes in body energy stores. Among weight-stable individuals, energy intake should approximately equal total energy expenditure (TEE). The development of the doubly labeled water (DLW) method, which accurately measures TEE, has enabled researchers to objectively quantify the extent of misreporting by comparing self-reported energy intake against measured energy expenditure [1]. Studies utilizing this approach have consistently revealed significant underreporting of energy intake, particularly among individuals with higher body mass indices [1].

This Application Note examines the nature and impact of systematic errors in self-reported dietary data, with a specific focus on their implications for biomarker validation research. We present quantitative evidence of these errors, detail experimental protocols for their quantification, and introduce biomarker-based approaches to correct for these biases, thereby enhancing the accuracy of nutritional epidemiology and clinical research.

Quantitative Evidence of Systematic Errors

Documented Underreporting of Energy and Nutrients

Empirical evidence from validation studies employing objective biomarkers consistently reveals substantial underreporting in self-reported dietary data. The extent of this underreporting varies by population subgroup and assessment method but demonstrates systematic patterns that undermine the reliability of nutritional epidemiology.

Table 1: Documented Underreporting of Energy Intake Using Doubly Labeled Water

| Population | Assessment Method | Underreporting Magnitude | Key Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obese Women (BMI 32.9 ± 4.6 kg/m²) | 7-day food diary | 34% less than TEE | Body mass index, weight concerns | [1] |

| Lean Women | 7-day food diary | No significant difference | Weight stability | [1] |

| Women undergoing weight loss treatment | Self-reported protein intake | 47% underestimation vs. urinary nitrogen | Dietary restriction mindset | [1] |

| Adults with obesity/weight concerns | Multiple methods | Increased with BMI | Weight concern rather than actual status | [1] |

The evidence demonstrates that systematic underreporting is not uniform across populations or nutrients. Protein intake tends to be less underreported compared to other macronutrients, suggesting selective reporting of foods perceived as socially desirable [1]. This differential misreporting alters the apparent composition of the diet, potentially creating spurious associations between specific nutrients and health outcomes.

Impact of Food Composition Variability

An additional layer of systematic error arises from the use of food composition data, which assumes consistent nutrient content in foods despite known variability. This variability introduces significant uncertainty in estimating nutrient intake, as demonstrated by research on bioactive compounds.

Table 2: Impact of Food Composition Variability on Bioactive Intake Assessment

| Bioactive Compound | Intake Uncertainty Range | Consequence for Participant Ranking | Biomarker Validation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavan-3-ols | Wide variability based on min-max food content | Same diet could place participant in bottom or top quintile | Urinary biomarker provided accurate ranking | [3] |

| (–)-Epicatechin | Significant overlap between low and high consumers | Difficulty identifying true high/low consumers | Biomarker method disagreed with FFQ-based ranking | [3] |

| Nitrate | Large uncertainty in estimated intake | Unreliable relative intake estimates | Biomarker corrected misclassification | [3] |

Research from the EPIC-Norfolk study demonstrates that the same individual could be classified in either the bottom or top quintile of intake depending on the actual nutrient content of the specific foods consumed, highlighting the profound limitations of relying on food composition tables for precise intake assessment [3]. This variability introduces greater uncertainty than the self-reporting errors that have received more attention in nutritional literature.

Biomarker-Based Validation Protocols

Protocol 1: Urinary Biomarker Assay for Food Intake Biomarkers

The development of comprehensive urinary biomarker panels represents a significant advancement for objectively assessing intake of specific foods and nutrients.

Principle: This method utilizes high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) to simultaneously quantify multiple urinary biomarkers of food intake (BFIs), providing an objective measure of dietary exposure that complements self-reported data [4].

Experimental Workflow:

Diagram Title: HPLC-MS/MS Workflow for Urinary Biomarkers

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect 24-hour urine samples or first-void morning urine from participants. Record exact collection times and volumes. Aliquot and store at -80°C until analysis [4] [5].

- Sample Preparation: Thaw samples slowly on ice. Vortex and centrifugate at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes. Dilute supernatant with internal standard solution. Pass through solid-phase extraction cartridges if necessary for purification [4].

- HPLC Separation: Inject prepared samples onto two complementary HPLC systems:

- Reversed-phase C18 column for medium to non-polar compounds

- Hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) column for polar compounds Use individual runs of 6 minutes with gradient elution optimized for each column type [4].

- MS/MS Analysis: Interface HPLC with triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Use electrospray ionization in both positive and negative mode with rapid polarity switching. Monitor multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions specific to each biomarker [4].

- Quantification: Generate calibration curves using authentic standards for each biomarker. Use internal standard method for quantification. Apply quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations throughout analytical batches [4].

- Method Validation: Validate according to FDA bioanalytical method validation guidelines:

- Selectivity: Confirm absence of interference from matrix components

- Linearity: Assess over physiological concentration range

- Accuracy and precision: Evaluate intra-day and inter-day variability

- Matrix effects: Determine ionization suppression/enhancement

- Recovery: Establish extraction efficiency for each analyte [4]

Applications: This protocol successfully quantified 44 BFIs absolutely and 36 semi-quantitatively, representing 27 foods frequently consumed in European diets (24 plant-derived and 3 animal-derived items) [4]. The method enables objective assessment of dietary patterns and validation of self-reported intake for nutritional studies.

Protocol 2: Biomarker Calibration of Self-Reported Data

The biomarker calibration approach uses objective biomarker measurements to correct systematic errors in self-reported dietary data, enhancing the reliability of nutritional epidemiology studies.

Principle: This statistical procedure uses recovery biomarkers that adhere to a classical measurement model (unbiased and independent of true intake) to calibrate self-reported intake, generating calibrated consumption estimates that more accurately reflect true dietary exposure [2].

Experimental Workflow:

Diagram Title: Biomarker Calibration Procedure

Procedure:

- Substudy Design: Embed a biomarker substudy within a larger cohort. Select a representative subset of participants (typically 450-550 participants) for intensive biomarker assessment. Include a reliability subsample (∼20%) to repeat the entire protocol after several months to account for temporal variation [2].

- Biomarker and Self-Report Collection: Collect both biomarker measurements and self-reported dietary data concurrently:

- Objective biomarkers: DLW for total energy, urinary nitrogen for protein, urinary potassium for potassium, urinary sodium for sodium

- Self-report instruments: FFQs, 24-hour recalls, food records

- Anthropometric and demographic data: BMI, age, sex, education, other relevant covariates [2]

- Regression Model Fitting: For each nutrient of interest, fit a linear regression model with the biomarker measurement as the dependent variable and the self-reported value plus relevant covariates as independent variables:

- Model: W = bâ‚€ + bâ‚Q + bâ‚‚Váµ€ + ε

- Where W is the log-transformed biomarker value, Q is the log-transformed self-reported value, and V is a vector of covariates related to measurement error [2]

- Calibration Equation Application: Apply the derived calibration equation throughout the larger cohort to generate calibrated consumption estimates:

- Calibrated intake: Ạ= bÌ‚â‚€ + bÌ‚â‚Q + bÌ‚â‚‚Váµ€

- These calibrated estimates correct systematic biases related to covariates V in the self-report Q [2]

- Validation: Assess calibration performance by:

- Variation explained: Determine the proportion of variation in biomarkers explained by self-reports and covariates

- Predictive power: Evaluate whether calibrated estimates recover a substantial fraction of the variation in true intake Z

- Disease association: Compare hazard ratios for diet-disease relationships using calibrated versus uncalibrated estimates [2]

Applications: This approach has been successfully implemented in large-scale studies including the Women's Health Initiative, where it enhanced the reliability of disease association analyses for cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and cancer in relation to energy and protein consumption [2].

Advanced Methodologies for Error Correction

Microbiome-Based Error Correction (METRIC)

Emerging methodologies leverage the relationship between diet and gut microbiota to correct random errors in nutrient profiles derived from self-reported assessments.

Principle: The Microbiome-based Nutrient Profile Corrector (METRIC) utilizes a deep learning framework that incorporates gut microbial composition to correct random errors in self-reported dietary assessments, functioning as a "denoiser" for nutrient profiles without requiring clean training data [6].

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Collect paired data on:

- Self-reported dietary intake: Using 24-hour recalls or diet records

- Gut microbiome composition: Via 16S rRNA or shotgun metagenomic sequencing of fecal samples

- Model Architecture: Implement a neural network with:

- Three hidden layers (256 nodes each)

- Skip connections that add input directly to output

- Xavier initialization for weight optimization

- Training Protocol:

- Generate corrupted nutrient profiles by adding random noise to assessed profiles

- Train model to remove added noise using corrupted profiles and microbiome data as input

- Use mean squared error as training loss function

- Application: Apply trained model to remove random measurement errors from self-reported nutrient profiles [6]

Performance: METRIC demonstrated excellent performance in minimizing simulated random errors, particularly for nutrients metabolized by gut bacteria. The method effectively corrected random errors even without microbiome data, though performance enhanced with microbial input [6].

Urinary Metabolite Biomarkers for Food Groups

Systematic identification of urinary metabolite biomarkers provides objective measures for assessing intake of specific food groups, overcoming limitations of self-report instruments.

Table 3: Urinary Metabolite Biomarkers for Food Group Assessment

| Food Group | Key Urinary Biomarkers | Utility | Limitations | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits & Vegetables | Polyphenol metabolites, sulfurous compounds (cruciferous) | Distinguishes broad food groups | Limited ability for individual foods | [5] |

| Citrus Fruits | Specific flavonoid metabolites | Good for citrus consumption | May not differentiate among citrus types | [5] |

| Whole Grains | Alkylresorcinol metabolites | Reasonable for whole grains | May not distinguish specific grains | [5] |

| Soy Foods | Isoflavone metabolites (daidzein, genistein) | Accurate for soy intake | Dependent on gut microbiome metabolism | [5] |

| Coffee/Cocoa/Tea | Methylxanthines, polyphenol metabolites | Good for consumption assessment | May not differentiate preparation methods | [5] |

| Alcohol | Ethyl glucuronide, ethyl sulfate | Direct assessment of alcohol intake | Short detection window | [5] |

The systematic review identified urinary biomarkers with utility for describing intake of broad food groups but limited ability to distinguish individual foods, highlighting both the promise and limitations of this approach [5]. Plant-based foods are often represented by polyphenol metabolites, while other food groups are distinguishable by innate food components such as sulfurous compounds in cruciferous vegetables or galactose derivatives in dairy [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Dietary Biomarker Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application & Function | Technical Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery Biomarkers | Doubly labeled water (²H₂¹â¸O), Urinary nitrogen | Objective measures of energy & protein intake | DLW requires mass spectrometry; urinary nitrogen from 24h collections | [2] [1] |

| Urinary Biomarkers | Polyphenol metabolites, Sulfurous compounds, Isoflavones | Specific food intake biomarkers | HPLC-MS/MS analysis; require metabolite identification | [4] [5] |

| Chromatography Columns | C18 reversed-phase, HILIC | Separation of dietary biomarkers | Use complementary columns for comprehensive coverage | [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Triple quadrupole MS/MS | Quantification of biomarkers | Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for sensitivity | [4] |

| Microbiome Tools | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shotgun metagenomics | Gut microbiota characterization | Used in METRIC error correction | [6] |

| Statistical Packages | Calibration algorithms, METRIC deep learning | Error correction & data calibration | R, Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch | [2] [6] |

Systematic errors in self-reported dietary data represent a fundamental limitation in nutritional research that can only be adequately addressed through the integration of objective biomarkers. The protocols and methodologies presented here provide researchers with robust tools to quantify, correct, and mitigate these errors, enhancing the validity of diet-disease association studies.

The implementation of urinary biomarker assays, biomarker calibration approaches, and advanced error-correction methodologies strengthens the scientific foundation of nutritional epidemiology. As the field moves toward precision nutrition, the adoption of these biomarker-based validation strategies will be essential for generating reliable evidence to inform dietary recommendations and public health policy.

Researchers are encouraged to incorporate these biomarker approaches into study designs, whether through embedded substudies, validation samples, or the application of error-correction algorithms. Only through such rigorous methodological approaches can we overcome the fundamental limitations of self-reported dietary data and advance our understanding of the relationship between diet and health.

The accurate assessment of dietary intake is fundamental to understanding its role in health and disease, yet traditional reliance on self-reported data is plagued by systematic and random measurement errors [7] [8]. Objective biomarkers of intake, measurable in biological specimens like blood and urine, are therefore critical for advancing nutritional epidemiology. An ideal dietary biomarker must fulfill three core methodological criteria: high specificity for a single food or nutrient, a predictable dose-response relationship with intake levels, and well-characterized temporal dynamics reflecting intake patterns over time [7]. Recent initiatives, such as the Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC), are leading systematic efforts to discover and validate such biomarkers using controlled feeding trials and advanced metabolomic profiling, aiming to move beyond the limited number of currently available biomarkers and significantly expand the tools for objective dietary assessment [9] [7]. This document outlines the defining characteristics of an ideal biomarker and provides detailed application notes and protocols for their validation within dietary assessment research.

Table 1: Core Criteria for an Ideal Dietary Intake Biomarker

| Criterion | Definition | Importance in Dietary Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | The biomarker is uniquely or predominantly associated with the intake of a specific food, nutrient, or defined food group. | Minimizes confounding by other dietary components and strengthens causal inference in association studies [7]. |

| Dose-Response | A consistent, and ideally linear, relationship exists between the amount of the food consumed and the concentration of the biomarker in biological matrices. | Enables the quantification of intake and calibration of self-reported dietary data to correct for measurement error [7] [8]. |

| Temporal Dynamics | The kinetic profile of the biomarker, including its rise time, peak concentration, and clearance rate after ingestion, is well-characterized. | Informs the timing of sample collection and determines whether the biomarker reflects recent or habitual intake [7]. |

Core Characteristics of an Ideal Dietary Biomarker

Specificity

Specificity ensures that a biomarker serves as a unambiguous indicator of its target dietary exposure. High specificity means the biomarker is not influenced by other foods, nutrients, endogenous metabolic processes, or environmental exposures. A lack of specificity can lead to misclassification of exposure in research settings. For example, a biomarker for red meat consumption should not also be elevated after consuming fish or plant-based proteins. Specificity is typically established through highly controlled feeding studies where participants consume a diet devoid of the target food, followed by its introduction in measured amounts, with subsequent metabolomic profiling to identify unique metabolite signatures [7].

Dose-Response Relationship

The dose-response relationship is quantitative core of a biomarker, linking the magnitude of intake to the level of the biomarker in a biological fluid. This relationship must be characterized through pharmacokinetic (PK) and dose-response (DR) studies [7]. A robust dose-response curve allows researchers to move from simple detection of consumption to actual quantification of intake amount. This is essential for developing calibration equations that correct the measurement error inherent in self-reported tools like Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) or 24-hour recalls [8]. The failure to account for this error, particularly the systematic under-reporting of energy intake common in individuals with higher body mass index, has been a major limitation in nutritional epidemiology [8].

Temporal Dynamics

Temporal dynamics refer to the time-course profile of a biomarker after ingestion. This includes parameters such as the time to first appearance in blood or urine, time to peak concentration, and half-life for clearance. Understanding these kinetics is crucial for determining a biomarker's applicable context of use. Biomarkers with a short half-life (hours) are suitable for assessing recent intake or for use in controlled feeding studies, while those with a longer half-life (days or weeks) or that accumulate in tissues, such as erythrocyte membrane fatty acids, are better suited for reflecting habitual or longer-term dietary patterns [10] [7]. Properly characterizing temporal dynamics ensures that biospecimens are collected at the appropriate time to capture the exposure of interest.

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

The validation of a novel dietary biomarker is a multi-stage process that progresses from discovery in highly controlled settings to evaluation in free-living populations. The following protocols detail the key experiments required at each stage.

Protocol 1: Phase 1 - Discovery and Pharmacokinetic Profiling

Objective: To identify candidate biomarker compounds and characterize their fundamental pharmacokinetic parameters (specificity, dose-response, temporal dynamics) in a controlled environment [7].

Study Design: A controlled feeding trial is the gold standard. A common design involves administering a single test food or a simplified diet in prespecified amounts to healthy participants.

Materials:

- Participants: Healthy adult volunteers (typically n=20-50 per study).

- Test Food: Standardized, compositionally well-defined food item.

- Biospecimen Collection: Blood (e.g., plasma, serum) and urine samples.

- Key Equipment: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) systems for metabolomic profiling.

Methodology:

- Baseline Period (e.g., 3-7 days): Participants consume a standardized diet strictly devoid of the target test food. Collect fasting baseline blood and urine samples.

- Intervention Period: Participants consume a single, defined dose of the test food. The dose should be physiologically relevant.

- Intensive Biospecimen Sampling: Collect serial blood and urine samples at predetermined time points post-consumption (e.g., 30min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 6h, 8h, 24h).

- Metabolomic Analysis: Profile all biospecimens using targeted and untargeted LC-MS platforms to identify metabolites that appear or significantly increase in concentration following test food ingestion compared to baseline.

- Data Analysis:

- Specificity: Identify metabolites unique to the test food intervention.

- Temporal Dynamics: Plot concentration vs. time curves for each candidate metabolite to determine time to peak (T~max~) and elimination half-life (t~1/2~).

- Dose-Response: In a separate or integrated study arm, administer different doses of the test food to establish the relationship between intake amount and biomarker concentration (AUC or C~max~).

Deliverable: A list of candidate biomarkers with associated PK parameters.

Protocol 2: Phase 2 - Evaluation in Complex Dietary Patterns

Objective: To assess the performance of candidate biomarkers to correctly identify consumption of the target food when participants are consuming complex, mixed diets of various patterns [7].

Study Design: Controlled feeding study with a crossover or parallel-arm design involving different dietary patterns (e.g., Western, Mediterranean, Vegetarian).

Methodology:

- Dietary Intervention: Participants are randomized to follow different controlled dietary patterns for a set period (e.g., 2-4 weeks). One pattern includes the target food, while others may or may not.

- Biospecimen Collection: Collect fasting blood or urine samples at the end of each dietary period.

- Blinded Analysis: Analyze biospecimens for the candidate biomarkers in a blinded fashion.

- Statistical Evaluation: Calculate the sensitivity (ability to correctly identify consumers) and specificity (ability to correctly identify non-consumers) of each candidate biomarker against the known intake records.

Deliverable: Performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity) for candidate biomarkers, leading to the selection of the most robust one(s) for final validation.

Protocol 3: Phase 3 - Validation in Free-Living Populations

Objective: To evaluate the validity of the candidate biomarker to predict consumption of the test food in an independent, observational cohort setting [7].

Study Design: Prospective observational study in a free-living population.

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit a target sample of participants from the general population (e.g., n=100+).

- Reference Method Comparison: Collect dietary data using repeated 24-hour dietary recalls (24-HDR) or food records as a reference method [10].

- Objective Biomarker Measurement: Collect biospecimens (blood, urine) for analysis of the candidate biomarker. Consider incorporating established objective reference measures such as:

- Data Analysis:

- Assess correlation (e.g., Spearman's) between biomarker levels and intake estimated from 24-HDRs.

- Use the Method of Triads to calculate validity coefficients, which quantify the correlation between each measurement method (Biomarker, 24-HDR, and True Intake) and the unobservable "true" intake [10].

- Use Bland-Altman plots to assess agreement between methods.

Deliverable: A validity coefficient for the biomarker, confirming its utility for assessing dietary intake in epidemiological studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Platforms for Dietary Biomarker Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function in Biomarker Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR | Metabolomic profiling for discovery and quantification of candidate biomarkers in blood and urine [9] [8]. |

| Immunoassays | ELISA, Meso Scale Discovery (MSD), Luminex | High-throughput, quantitative analysis of specific protein biomarkers or adducts [11]. |

| Molecular Biology | qPCR, RNA-Seq | Analysis of genetic biomarkers or transcriptomic responses to dietary intake [11]. |

| Stable Isotopes | Doubly Labeled Water (²H₂¹â¸O) | Objective measurement of total energy expenditure as a reference for calibrating energy intake data [10] [8]. |

| Biospecimen Collection | Urine collection kits, Blood collection tubes (e.g., EDTA), Portable freezers | Standardized collection, temporary storage, and preservation of biological samples for subsequent biomarker analysis [10]. |

| Reference Materials | Certified calibrators, Stable isotope-labeled internal standards | Ensuring accuracy and precision in the quantification of analyte concentrations during mass spectrometry analysis. |

| Seneciphyllinine | Seneciphyllinine, CAS:90341-45-0, MF:C20H25NO6, MW:375.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sinococuline | Sinococuline is a potent pan-DENV inhibitor and tumor cell growth suppressor. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or diagnostic use. |

Workflow and Regulatory Visualization

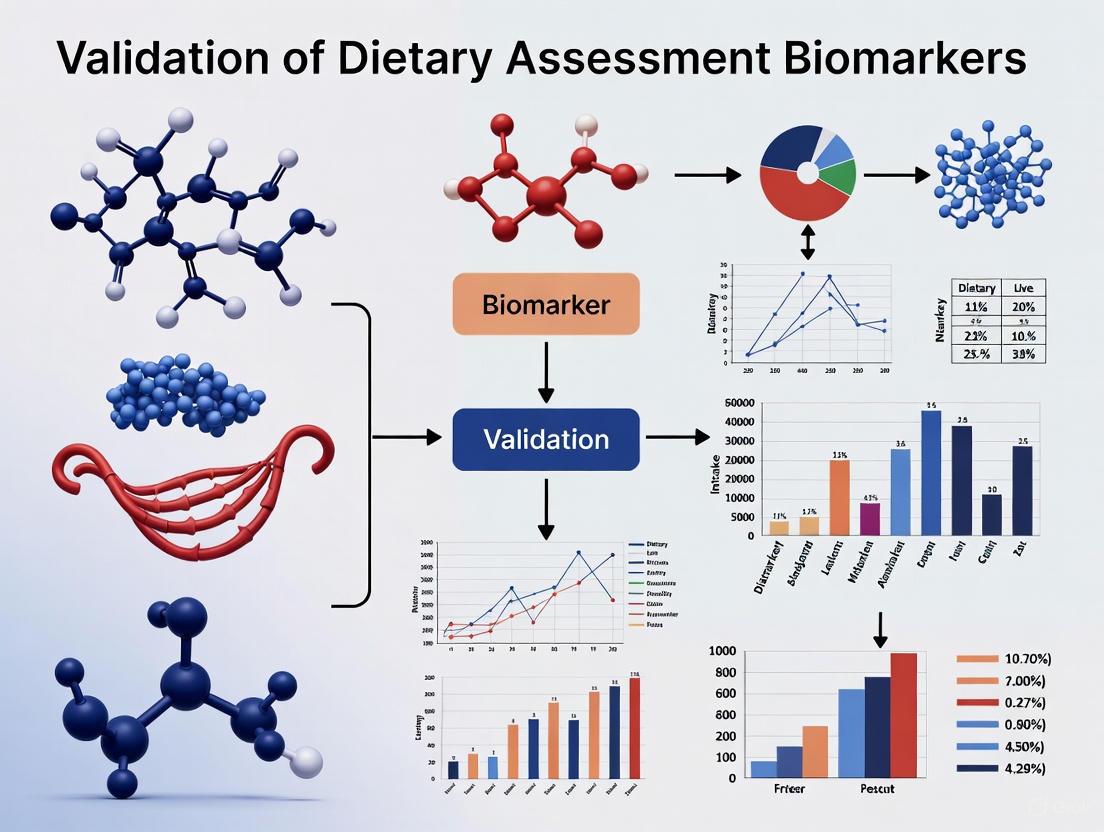

Dietary Biomarker Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive multi-phase pathway for the discovery and validation of a novel dietary biomarker, from initial controlled discovery to application in free-living populations.

Experimental Design for Specificity and Dose-Response

This diagram details the specific experimental design and measurements required to establish the specificity and dose-response relationship of a candidate biomarker during the Phase 1 discovery stage.

Regulatory and Methodological Considerations

The validation of biomarker assays for regulatory purposes requires a distinct framework from traditional pharmacokinetic drug assays. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) 2025 guidance on Bioanalytical Method Validation for Biomarkers emphasizes a "fit-for-purpose" approach, where the extent of validation is driven by the biomarker's Context of Use (COU) [12] [13]. This is critical because, unlike drugs, biomarkers are often endogenous molecules for which a perfectly identical reference standard may not exist, and their biological variability must be considered [12]. Key differentiators include:

- Context of Use is Paramount: The required stringency of the assay validation—including accuracy, precision, and stability assessments—depends on whether the data will support internal decision-making, mechanism of action studies, or a regulatory claim [12] [13].

- Focus on Endogenous Analyte Performance: Validation must demonstrate reliable measurement of the endogenous biomarker, not just a spiked reference standard. Parameters like parallelism are essential to confirm that the calibrator behaves similarly to the endogenous analyte in the assay matrix [12].

- Adherence to Guidelines: Sponsors must include justifications for their validation approach in regulatory submissions, aligning with the FDA's recommendation to use ICH M10 as a starting point while adapting it appropriately for the unique challenges of biomarker bioanalysis [12] [13].

Accurate dietary assessment represents a fundamental challenge in nutritional science and epidemiology. Poor diet quality ranks among the most significant modifiable risk factors for chronic diseases, yet the accurate assessment of diet in free-living populations remains methodologically complex [7]. Traditional dietary assessment approaches rely heavily on self-reported methodologies including food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), multiple-day food diaries, and 24-hour recalls, all of which are susceptible to systematic and random measurement errors, recall bias, and misreporting [7]. The limitations of these subjective methods have constrained the scientific community's ability to confidently establish causal relationships between diet and health outcomes.

Objective biomarkers that reliably reflect intake of nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns present a transformative opportunity to advance nutritional science [9]. The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) was established in 2021 as the first major coordinated effort to address this methodological gap through the systematic discovery and validation of biomarkers for foods commonly consumed in the United States diet [9] [7]. This large-scale initiative connects experts in nutrition, data science, and statistics to discover objective measures that can inform individual dietary patterns and advance nutritional epidemiology [14].

DBDC Organizational Structure and Governance

The DBDC operates through a coordinated infrastructure comprising multiple academic institutions and governing bodies. The consortium includes three primary study centers based at leading academic medical centers: Harvard University (in collaboration with the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard), the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (in collaboration with the University of Washington), and the University of California Davis (in collaboration with the USDA Agricultural Research Service) [7]. Each center maintains an independent infrastructure with specialized cores focusing on dietary intervention trials, metabolomic profiling, statistical analyses, and administration [7].

A Data Coordinating Center (DCC) at Duke University spearheads administrative activities, including data quality control, analysis for progress reports, and streamlined operations using a central document repository [7]. The DCC is responsible for making all trial data available to internal and external researchers through both the NIDDK Central Repository and Metabolomics Workbench at the trial's conclusion [7]. The consortium's organizational structure ensures scientific rigor while maintaining focus on participant safety and data integrity.

Table: DBDC Organizational Structure and Responsibilities

| Component | Institution | Primary Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Study Centers | Harvard University, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, UC Davis | Conduct controlled feeding trials, collect biospecimens, perform metabolomic analyses |

| Data Coordinating Center | Duke University | Data quality control, repository management, administrative coordination, trial monitoring |

| Steering Committee | Principal investigators from all sites | Governing body for strategic decisions on scientific and administrative objectives |

| Metabolomics Working Group | Cross-institutional experts | Harmonize analytical methods for identifying food-associated markers |

| Data Analysis Working Group | Cross-institutional experts | Develop data dictionaries and analysis plans across all study phases |

The consortium's governance includes a Steering Committee comprising principal investigators from all study centers and program officers from funding agencies including the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) [7]. This committee participates in strategic decisions regarding scientific and administrative objectives. Specialized working groups focus on dietary intervention, metabolomics, and data analysis/harmonization to ensure coordinated approaches across all research phases [7].

Experimental Framework: The Three-Phase Biomarker Validation Pipeline

The DBDC has implemented a systematic, three-phase approach to biomarker discovery and validation designed to ensure rigorous evaluation of candidate biomarkers across controlled and free-living conditions.

Phase 1: Biomarker Discovery and Pharmacokinetic Characterization

Phase 1 employs controlled feeding trial designs where test foods are administered in prespecified amounts to healthy participants [9]. Researchers collect blood and urine specimens at multiple timepoints following test meal consumption, followed by comprehensive metabolomic profiling to identify candidate compounds [9]. These studies characterize the pharmacokinetic parameters of candidate biomarkers, including dose-response relationships and temporal patterns of appearance and clearance [9]. The UC Davis center, for example, employs randomized controlled dietary interventions where participants consume different servings of fruit and vegetable mixtures within a standard mixed meal setting in an inverse dosing gradient [15]. Specimen collection includes fasting blood samples followed by postprandial collections at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours after meal consumption, with urine pooled between 0-2, 2-4, 4-6, and 6-8 hours, plus a final 8-24 hour collection [15].

Phase 2: Biomarker Evaluation in Varied Dietary Patterns

Phase 2 evaluates the ability of candidate biomarkers to identify individuals consuming biomarker-associated foods using controlled feeding studies of various dietary patterns [9]. This phase tests whether biomarkers identified in Phase 1 remain specific and sensitive when incorporated into diverse dietary backgrounds. At UC Davis, this involves randomizing 40 volunteers to consume either a typical American diet (TAD) or a high-quality Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) diet in a parallel design [15]. Compliance is monitored through daily food checklists, menu deviation records, and objective measures including urinary potassium, urinary nitrogen, red blood cell fatty acid profiles, and serum carotenoids [15].

Phase 3: Validation in Observational Settings

Phase 3 assesses the validity of candidate biomarkers to predict recent and habitual consumption of specific test foods in independent observational settings [9]. This critical phase evaluates biomarker performance in free-living populations consuming self-selected diets, providing essential data on real-world applicability. The UC Davis team conducts cross-sectional studies in diverse cohorts, comparing biomarker levels to traditional diet recall assessment tools [15]. This phase determines whether biomarkers remain robust outside controlled feeding environments and across populations with varying characteristics.

Diagram of the DBDC three-phase validation pipeline. The pipeline progresses from initial discovery under controlled conditions to real-world validation, ensuring biomarkers are specific, sensitive, and applicable to free-living populations.

Methodological Approaches and Analytical Technologies

Metabolomic Profiling and Bioinformatics

The DBDC employs state-of-the-art metabolomic technologies to identify and characterize food intake biomarkers. Each study center utilizes liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and hydrophilic-interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) protocols to analyze blood and urine specimens [7]. The Metabolomics Working Group coordinates strategies to enhance harmonization of metabolite identifications across platforms, based on MS/MS ion patterns and retention times [7]. For unknown metabolite identification, centers employ exhaustive high-resolution MS/MS data collections with ramped collision energies using LC-QTOF MS and SWATH-based LC-TripleTOF MS systems [15]. This ensures comprehensive characterization of metabolite profiles with associated high-quality retention time and accurate mass records.

Statistical and Bioinformatics Approaches

The consortium employs sophisticated statistical models to handle the complexity of metabolomic data. Researchers construct generalized linear models (GLM) adjusting for subject metadata using Gaussian, log-link Gaussian, log-normal, log-link inverse Gaussian, and log-link Gamma methods, with subjects as random effects [15]. Models with the lowest Bayesian information criterion are selected for final analysis [15]. Additionally, effect sizes are estimated using Bayesian regression credible intervals of >95% [15]. These approaches account for the expected diversity in participant genetics, lifestyle, environmental exposures, gut microbiome, and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) profiles that influence metabolite levels.

Table: Key Analytical Methods and Technologies in DBDC Research

| Method Category | Specific Technologies/Approaches | Application in DBDC |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolomic Profiling | LC-MS, HILIC, LC-QTOF MS, SWATH-based LC-TripleTOF MS | Comprehensive identification of metabolites in blood and urine specimens |

| Statistical Modeling | Generalized Linear Models (GLM), Bayesian regression, Bayesian information criterion | Analyze metabolite data accounting for inter-individual variability |

| Food Composition Analysis | Food composition databases, ingredient analysis | Ensure proposed biomarkers are specific to target food groups |

| Quality Control | Analytical precision and stability protocols, standardized collection procedures | Ensure data quality and reproducibility across multiple sites |

| Data Harmonization | Common data elements, standardized protocols, central repositories | Enable cross-site comparisons and meta-analyses |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application in DBDC |

|---|---|---|

| Biospecimen Collection | Blood collection tubes (various additives), urine collection containers, fecal sample kits | Standardized collection of biological specimens for metabolomic analysis |

| Chromatography Systems | Liquid chromatography systems, HILIC columns, C18 columns | Separation of complex biological mixtures prior to mass spectrometry |

| Mass Spectrometry | QTOF MS, TripleTOF MS systems, electrospray ionization sources | High-resolution detection and identification of metabolite compounds |

| Food Composition Databases | USDA Food Composition Database, customized food ingredient databases | Linking metabolite patterns to specific food sources and components |

| Metabolite Standards | Commercially available reference standards, synthesized compounds for unknown metabolites | Quantification and verification of metabolite identities |

| Data Processing Software | High-dimensional bioinformatics platforms, metabolite identification algorithms | Processing raw mass spectrometry data into identifiable metabolite patterns |

Case Study: Biomarker Development for Ultra-Processed Foods

A notable parallel initiative at the National Institutes of Health demonstrates the potential output of the DBDC approach. Researchers recently developed and validated poly-metabolite scores for diets high in ultra-processed foods (UPF) [16] [17]. This research combined observational data from 718 free-living adults with experimental data from a randomized, controlled, crossover-feeding trial of 20 adults consuming diets containing either 80% or 0% energy from UPF [17] [18].

The study identified hundreds of serum and urine metabolites correlated with percentage energy from UPF intake, including lipids, amino acids, carbohydrates, xenobiotics, cofactors, vitamins, peptides, and nucleotides [17]. Using LASSO regression, researchers selected 28 serum and 33 urine metabolites as predictors of UPF intake, creating biospecimen-specific poly-metabolite scores [17]. These scores successfully differentiated, within individuals, between the ultra-processed and unprocessed diet phases in the controlled feeding trial [17] [18]. This research demonstrates how integrated observational and experimental approaches can yield objective measures of complex dietary exposures.

Data Sharing and Research Dissemination

The DBDC has established comprehensive data sharing policies to maximize the research community's benefit from consortium activities. All data generated throughout the three study phases will be archived in a publicly accessible database as a resource for the broader research community [9] [7]. The DCC will submit data to both the NIDDK Central Repository and Metabolomics Workbench at the trial's conclusion [7]. The consortium maintains a dedicated website (https://dietarybiomarkerconsortium.org/) that includes a cloud analysis platform and central filing system for consortium-wide documents [7]. This commitment to open science ensures that DBDC resources will continue to advance nutritional biomarker research beyond the consortium's initial funding period.

The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium represents a transformative initiative in nutritional science, addressing fundamental methodological limitations that have historically constrained the field. Through its systematic, three-phase approach to biomarker discovery and validation, coordinated multi-institutional structure, and application of advanced metabolomic technologies, the DBDC is positioned to significantly expand the list of validated biomarkers for foods consumed in the United States diet. The consortium's work promises to advance understanding of diet-health relationships, improve dietary assessment in research and clinical practice, and ultimately support more effective evidence-based nutritional recommendations. As the DBDC progresses through its research phases, its outputs will provide valuable resources for researchers, clinicians, and public health professionals seeking to incorporate objective dietary biomarkers into their work.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to understanding the relationship between diet and health. Self-reported methods, such as food frequency questionnaires and dietary recalls, are hampered by significant limitations including recall bias and misreporting [5]. Biomarkers of Food Intake (BFIs) offer a powerful, objective alternative to these subjective measures [19] [20]. These biomarkers are typically food-derived compounds or their metabolites that can be measured in biological samples like blood or urine [19].

A critical characteristic of any BFI is its time-response, which refers to the period over which it can reliably reflect intake [21]. Categorizing biomarkers based on their kinetic profiles—as short-term, medium-term, or long-term indicators—is essential for selecting the right tool for a given research purpose, whether it's assessing a single meal, habitual intake over days, or long-term dietary patterns. This document outlines the classification, validation, and application of dietary biomarkers based on their temporal responsiveness, providing a framework for their use in nutritional research and drug development.

Defining Biomarker Categories by Time-Response

The time-response of a biomarker describes its kinetic behavior, including its rise after consumption, peak concentration, and elimination half-life. This parameter determines the timeframe a biomarker represents and informs the optimal sampling protocol [21]. The following table summarizes the defining characteristics of each biomarker category.

Table 1: Categorization of Dietary Biomarkers by Time-Response

| Category | Representative Timeframe | Key Characteristics | Primary Biofluids | Main Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | Up to 24 hours [19] | Rapid absorption and excretion; high specificity for recent intake; often parent compounds or phase I/II metabolites. | Urine, Plasma | Verifying recent intake (e.g., a single meal or food); acute intervention studies. |

| Medium-Term | Several days | Intermediate kinetics; may reflect cumulative intake over a few days. | Urine, Serum | Assessing dietary patterns over a short period (e.g., a few days to a week). |

| Long-Term | Several days to weeks [19] | Slow turnover rates; often incorporated into tissues or subject to enterohepatic recirculation; good for habitual intake. | Erythrocytes, Adipose Tissue, Hair | Measuring habitual or long-term dietary exposure in epidemiological studies; assessing compliance in long-term interventions. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for validating a biomarker's time-response and assigning it to the appropriate category.

Biomarker Validation and Representative Examples

The Validation Framework

For a biomarker to be reliably used, it must undergo a rigorous validation process beyond establishing its time-response. A consensus-based procedure proposes eight key criteria for systematic BFI validation [21]:

- Plausibility: The biomarker should be specific to the food, with a clear biochemical explanation for its presence post-consumption [21].

- Dose-Response: A quantitative relationship should exist between the amount of food consumed and the biomarker concentration [21].

- Time-Response: The kinetic profile, including half-life, must be characterized to define the intake period it reflects [21].

- Robustness: The biomarker should perform reliably in different free-living populations and with varying dietary patterns [21].

- Reliability: Measurements should agree with those from a reference method or other biomarkers for the same food [21].

- Stability: The biomarker must remain chemically stable under standard sample collection, processing, and storage conditions [21].

- Analytical Performance: The assay must demonstrate precision, accuracy, and acceptable detection limits [21].

- Reproducibility: Results should be consistent across different laboratories [21].

Representative Biomarkers by Food Group and Timeframe

The following table provides concrete examples of potential and validated biomarkers across different food groups, categorized by their typical timeframes.

Table 2: Examples of Food Intake Biomarkers Categorized by Time-Response

| Food / Food Group | Candidate Biomarker | Primary Category | Key Characteristics & Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus Fruits | Proline Betaine | Short-Term | A well-validated biomarker; rapidly excreted in urine, specific to citrus; distinguishes between low, medium, and high consumers [20]. |

| Apples | Phloretin and its glucuronide | Short-Term | Phloretin is released after apple intake; its glucuronide metabolite is a dominant urinary biomarker [19] [5]. |

| Tomatoes | N-caprylhistamine (HmC8) and glucuronides | Short-Term | Imidazolalkaloids detectable in higher amounts in urine after tomato juice consumption [19]. |

| Bell Peppers | Glucuronosido-uronic acid apo-geranyllinalools (B2, B5) | Short-Term | Specific compounds identified as reliable biomarkers for smaller consumed amounts [19]. |

| Whole Grains | Alkylresorcinols (AR) & metabolites (DHBA, DHPPA) | Short- to Medium-Term | ARs are constituents of wheat, rye; their metabolites 3,5-DHBA and 3,5-DHPPA are known biomarkers for whole grain intake [19] [5]. |

| Meat & Fish | Carnosine, Anserine, 1-MH, 3-MH, TMAO | Short-Term | Carnosine (red meat), Anserine/3-MH (poultry), TMAO/3-MH (fish) are described as potential biomarkers [19] [5]. |

| Fruit & Vegetable Intake (General) | Serum Carotenoids | Medium- to Long-Term | Used as a reference for fruit and vegetable consumption; incorporates into blood lipids [22] [23]. |

| Dietary Fatty Acids | Erythrocyte Membrane Fatty Acids | Long-Term | Reflects habitual intake of fatty acids (e.g., omega-3, omega-6 PUFAs) due to slow turnover of red blood cell membranes [22] [23]. |

| Energy & Protein Intake | Doubly Labeled Water (Energy), Urinary Nitrogen (Protein) | Long-Term (Habitual) | Considered objective reference methods for validating self-reported energy and protein intake over periods of days to weeks [22] [23]. |

The kinetic behavior of these biomarkers post-consumption can be visualized as follows, informing the optimal time window for sample collection.

Experimental Protocols for Time-Response Validation

Protocol: Determining Biomarker Kinetics in an Acute Intervention Study

This protocol is designed to characterize the time-response of a candidate short-term biomarker.

1. Objective: To define the pharmacokinetic profile (time-to-peak, half-life, return to baseline) of a candidate biomarker following a controlled dose of a specific food.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Test Food: Standardized portion of the food of interest (e.g., 200g of tomato puree, 250mL of orange juice).

- Participants: Healthy adult volunteers (typically n=10-20), after an overnight fast.

- Biospecimen Collection: Kits for venous blood collection (serum/plasma) and urine containers (for spot or total 24-hour urine).

- Analytical Instrumentation: Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system is the gold standard for specificity and sensitivity [19].

- Chemical Standards: Authentic analytical standards of the candidate biomarker for method calibration and quantification [19].

3. Procedure: 1. Baseline Sample Collection: Obtain fasting blood and urine samples from participants (T=0). 2. Administer Test Food: Provide a single, controlled portion of the test food for consumption. 3. Serial Sampling: Collect blood and urine samples at predetermined time points post-consumption (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours). 4. Sample Processing: Centrifuge blood samples to obtain plasma/serum and aliquot all samples. Store immediately at -80°C. 5. Biomarker Quantification: Analyze all samples using a validated LC-MS/MS method to determine biomarker concentration at each time point [19].

4. Data Analysis:

- Plot biomarker concentration against time for each subject.

- Use pharmacokinetic software to calculate key parameters: time to maximum concentration (T~max~), maximum concentration (C~max~), and elimination half-life (t~1/2~).

- The time taken for the biomarker concentration to return to baseline levels informs its classification as short-term.

Protocol: Assessing a Biomarker for Habitual Intake in a Free-Living Population

This protocol evaluates the utility of a biomarker for reflecting medium- to long-term intake.

1. Objective: To correlate biomarker levels in easily collected biospecimens (e.g., spot urine, blood) with habitual dietary intake assessed over a preceding period.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Dietary Assessment Tools: Repeated 24-hour dietary recalls or food diaries over the study period (e.g., 2 weeks) [23].

- Biospecimen Collection: Equipment for single blood draws (e.g., for erythrocyte fatty acids) or spot urine collection.

- Analytical Instrumentation: LC-MS/MS or GC-MS for biomarker quantification.

3. Procedure: 1. Study Design: Conduct an observational study over 2-4 weeks. 2. Dietary Data Collection: Administer multiple 24-hour dietary recalls (e.g., 3 non-consecutive recalls) to estimate habitual intake of the target food [23]. 3. Biomarker Sampling: Collect single biospecimen samples (e.g., spot urine, fasting blood) from participants at the end of the dietary assessment period. For long-term biomarkers like erythrocyte fatty acids, a single sample is sufficient [23]. 4. Analysis: Quantify biomarker levels in the biospecimens.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the correlation (e.g., Spearman's rank) between the self-reported habitual intake of the food and the measured biomarker level.

- Use the method of triads to quantify the measurement error between the biomarker, the self-report tool, and the unknown "true intake" [23].

- A strong correlation suggests the biomarker is robust and reliable for measuring habitual intake, supporting its classification as a medium- or long-term indicator.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dietary Biomarker Research

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | The core analytical platform for identifying and quantifying a wide range of dietary biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity [19]. | Requires method development and optimization for each biomarker or panel. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Pure compounds used to develop and validate analytical methods, create calibration curves, and confirm biomarker identity [19]. | Essential for quantitative accuracy; purity must be certified. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Isotopically labeled versions of the biomarker added to samples to correct for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation. | Critical for achieving high precision and accuracy in complex biological matrices. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Used to clean up and pre-concentrate biomarkers from urine or plasma samples before LC-MS/MS analysis, reducing ion suppression. | Select the sorbent chemistry (e.g., C18, mixed-mode) based on the biomarker's physicochemical properties. |

| MyPlate Food Guidance | A framework (used by the Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium) for selecting test foods that are commonly consumed in the population, ensuring relevance [7]. | Ensures research addresses key components of the diet. |

| Controlled Feeding Diets | Precisely formulated diets used in intervention studies (Phases 1 & 2 of biomarker validation) to establish dose-response and kinetics without dietary confounding [9] [7]. | Requires a metabolic kitchen and high compliance. |

| (+)-Marmesin | (+)-Marmesin, CAS:13849-08-6, MF:C14H14O4, MW:246.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pneumocandin C0 | Pneumocandin C0, CAS:144074-96-4, MF:C50H80N8O17, MW:1065.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Metabolomics in Expanding the Biomarker Discovery Pipeline

Metabolomics, defined as the global assessment of endogenous metabolites within a biological system, has emerged as a powerful tool in the biomarker discovery pipeline [24] [25]. This scientific discipline provides a "snapshot" of gene function, enzyme activity, and the physiological landscape by measuring the end-products of cellular regulatory processes [25]. As the downstream endpoint of the omics cascade, the metabolome reflects the ultimate response of biological systems to genetic, environmental, and lifestyle influences, including dietary intake [24] [26]. Unlike other omics approaches, metabolomics offers a direct readout of physiological activity and metabolic state, capturing the dynamic interactions between an organism's genome and its environment [27] [26].

The proximity of metabolites to the functional phenotype makes them particularly valuable for validating dietary assessment biomarkers [26]. Metabolic profiling can reveal subtle biochemical changes in response to nutrient intake, providing objective indicators that complement traditional dietary assessment methods like food frequency questionnaires and food records [26]. As such, metabolomics holds exceptional promise for identifying robust biomarkers that accurately reflect dietary exposure, nutrient metabolism, and biochemical status in nutritional research [26].

Analytical Platforms for Metabolomic Analysis

The two primary analytical platforms used in metabolomic studies are mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [24] [28] [25]. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations for biomarker discovery, particularly in the context of dietary assessment validation.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Analytical Platforms in Metabolomics

| Platform | Sensitivity | Throughput | Sample Preparation | Quantitative Strength | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) | High (pM-nM) | Moderate | Moderate | Excellent with standards | Targeted analysis of specific nutrient metabolites |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Low (μM-mM) | High | Minimal | Excellent | Untargeted profiling, structural elucidation |

| Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS) | High | Low | Extensive | Good | Volatile compounds, metabolic fingerprinting |

| Fourier Transform-MS (FT-MS) | Very High | Low | Moderate | Good | Comprehensive untargeted analysis |

LC-MS has become particularly prominent in clinical and nutritional research due to its high sensitivity and specificity when coupled with separation techniques [27] [26]. The combination of different chromatographic methods with mass spectrometry enhances coverage of the diverse chemical space occupied by metabolites [28]. Recent advances in ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) and high-resolution mass spectrometry have significantly improved both the efficiency and reliability of metabolic profiling [24] [26].

NMR spectroscopy, while less sensitive than MS-based techniques, provides unparalleled structural information and quantitative accuracy without requiring extensive sample preparation [25]. This non-destructive method is particularly valuable for validating novel metabolite identities and conducting dynamic flux analyses [25].

Figure 1: Workflow for Metabolomic Biomarker Discovery in Dietary Assessment Research

Experimental Design and Protocol for Dietary Biomarker Discovery

Sample Collection and Preparation Protocol

Proper sample collection and handling are critical for generating reliable metabolomic data, particularly in nutritional studies where pre-analytical factors can significantly impact results [27].

Materials Required:

- EDTA or heparin tubes for blood collection

- Cryovials for long-term storage

- Methanol:water:chloroform (40:20:20) extraction solvent

- Protein precipitation plates or tubes

- Internal standards (e.g., stable isotope-labeled compounds)

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Patient Preparation and Selection

- Standardize fasting conditions (typically 8-12 hours overnight fast)

- Control for timing of sample collection to account for circadian rhythms

- Record recent dietary intake, medication use, and lifestyle factors

- Define inclusion/exclusion criteria accounting for age, sex, and comorbidities [27]

Blood Collection and Processing

- Collect venous blood following standardized phlebotomy procedures

- Process samples within 30 minutes of collection

- Centrifuge at 2,500 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma/serum

- Aliquot into cryovials and flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen

- Store at -80°C until analysis

Metabolite Extraction

- Thaw samples on ice

- Add 300 μL of sample to 900 μL of ice-cold extraction solvent

- Vortex vigorously for 30 seconds

- Incubate at -20°C for 1 hour

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Transfer supernatant to MS vials for analysis

LC-MS Analysis Protocol for Nutrient Metabolites

This targeted protocol focuses on quantifying metabolites related to dietary intake and nutrient metabolism.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C18 reversed-phase (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% formic acid in water

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 2% B to 95% B over 12 minutes

- Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection volume: 5 μL

- Column temperature: 40°C

Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive and negative modes

- Source temperature: 150°C

- Desolvation temperature: 500°C

- Cone gas flow: 50 L/hour

- Desolvation gas flow: 800 L/hour

- Capillary voltage: 3.0 kV (positive), 2.5 kV (negative)

- Data acquisition: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Metabolomics data analysis requires specialized statistical approaches to handle the high-dimensional, complex nature of metabolic profiles [28]. The process involves multiple steps from raw data preprocessing to biomarker validation.

Data Preprocessing Pipeline

Raw Data Conversion

- Convert vendor-specific files to open formats (mzXML, mzML)

- Perform peak detection, alignment, and integration

Metabolite Identification

- Match accurate mass and retention time to authentic standards

- Compare MS/MS fragmentation patterns with spectral libraries

- Calculate confidence levels following Metabolomics Standards Initiative guidelines

Data Normalization and Imputation

- Correct for technical variation using quality control-based normalization

- Apply log-transformation to address heteroscedasticity

- Impute missing values using methods appropriate for MNAR (Missing Not At Random) data

Table 2: Statistical Methods for Metabolomic Biomarker Discovery

| Analysis Type | Method | Application in Dietary Biomarkers | Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsupervised Multivariate | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Quality control, outlier detection | SIMCA-P, MetaboAnalyst |

| Supervised Multivariate | Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) | Classifying dietary patterns | R (ropls package) |

| Differential Analysis | Linear models with empirical Bayes moderation | Identifying significantly altered metabolites | Limma, MetaboDiff |

| Pathway Analysis | Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) | Mapping nutrients to metabolic pathways | MetaboAnalyst, MBRole |

| Correlation Networks | Weighted Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) | Identifying co-regulated metabolite modules | WGCNA, Cytoscape |

Biomarker Validation Framework

Robust biomarker validation requires both analytical and clinical validation phases [27]. For dietary assessment biomarkers, this includes:

Analytical Validation

- Determine precision, accuracy, and recovery for target metabolites

- Establish limit of detection and quantification

- Assess matrix effects and carryover

- Verify stability under various storage conditions

Clinical/Biological Validation

- Confirm association with dietary intake in controlled feeding studies

- Demonstrate dose-response relationships

- Assess specificity to particular foods or nutrients

- Validate in independent cohorts

Figure 2: Data Analysis Workflow for Metabolomic Biomarker Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of metabolomic workflows requires specific reagents and materials optimized for various stages of the analytical process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolomic Biomarker Studies

| Category | Item | Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | EDTA blood collection tubes | K2EDTA, 10.8 mg | Prevents coagulation while preserving metabolite stability |

| Cryogenic vials | 2.0 mL, external thread | Secure storage at -80°C; compatible with automation | |

| Metabolite Extraction | LC-MS grade methanol | ≥99.9% purity, low volatility | Primary extraction solvent for polar metabolites |

| LC-MS grade water | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistance | Prevents ion suppression in MS analysis | |

| Stable isotope internal standards | 13C, 15N labeled compounds | Quantification normalization; recovery calculation | |

| Chromatography | C18 reversed-phase columns | 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm | Optimal separation of complex metabolite mixtures |

| HILIC columns | 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm | Retention of polar metabolites poorly captured by C18 | |

| Ammonium acetate | LC-MS grade, 5 mM | Mobile phase additive for improved ionization | |

| Mass Spectrometry | Calibration solution | Sodium formate clusters | Daily mass accuracy calibration |

| Quality control pool | Representative sample mix | Monitoring instrumental performance over time | |

| Phenylephrine | Phenylephrine Hydrochloride | High-purity Phenylephrine for research. Study vasoconstriction, hypotension, and mydriasis. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-Methyl-2-butenoic acid | 3-Methyl-2-butenoic acid, CAS:541-47-9, MF:C5H8O2, MW:100.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications to Dietary Assessment Biomarker Validation

Metabolomics has demonstrated significant utility in validating and discovering dietary assessment biomarkers across multiple nutritional contexts:

Food-Specific Biomarker Discovery

Controlled feeding studies coupled with metabolomic profiling have identified specific metabolites associated with intake of particular foods:

- Polyphenol-rich foods: Hippuric acid and other phenylacetylglutamine derivatives as biomarkers of fruit and vegetable intake

- Meat consumption: Carnosine and anserine as biomarkers of poultry and beef intake

- Fish consumption: Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA, DHA) and their metabolites

- Whole grains: Alkylresorcinols and their metabolites as biomarkers of whole grain wheat and rye intake

Dietary Pattern Validation

Metabolomic profiles can validate adherence to specific dietary patterns:

- Mediterranean diet: Combinations of lipids, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds

- Plant-based diets: Specific phytochemicals and their metabolic derivatives

- High-protein diets: Altered urea cycle metabolites and amino acid profiles

Nutrient Status Assessment

Metabolomics provides objective assessment of functional nutrient status:

- B vitamin status: Direct measurement of vitamins and their metabolic intermediates

- Antioxidant status: Redox balance markers and oxidative stress metabolites

- Energy metabolism: TCA cycle intermediates reflecting mitochondrial function

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, several challenges remain in implementing metabolomics for routine dietary biomarker validation [27]:

Pre-analytical Variability Standardization of sample collection, processing, and storage protocols is essential to minimize technical variability that could obscure biological signals [27]. This is particularly important in multi-center studies where protocol harmonization is challenging.

Analytical Validation Robust quantification methods must be established for candidate biomarkers before they can be deployed in clinical or public health settings [27]. This includes demonstrating analytical specificity, sensitivity, reproducibility, and stability across relevant biological matrices.

Biological Interpretation Complex interactions between diet, gut microbiota, and host metabolism complicate the interpretation of dietary biomarkers [26]. Advanced computational methods and integration with other omics data are needed to establish causal relationships.

Translation to Clinical Practice Most metabolomic biomarkers discovered in research settings fail to progress to clinical implementation due to barriers in validation, regulatory approval, and cost-effectiveness [27]. Future work should focus on bridging this translation gap through rigorous validation studies and demonstration of clinical utility.

The continued advancement of metabolomic technologies, combined with sophisticated data analysis approaches, promises to significantly expand the biomarker discovery pipeline for dietary assessment [24] [26]. As these tools become more accessible and standardized, metabolomics is poised to transform how we objectively measure dietary intake and assess nutritional status in both research and clinical practice.

Biomarker Discovery Pipelines and Analytical Techniques in Practice

Controlled Feeding Trials as the Gold Standard for Discovery

Diet is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for chronic diseases, yet accurate assessment of dietary intake remains a significant challenge in nutritional research [7]. Self-reported dietary assessment methods, such as food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour recalls, are plagued by systematic and random measurement errors that limit their reliability [7] [29]. In response to these challenges, controlled feeding trials have emerged as the gold standard methodology for discovering and validating objective dietary biomarkers [7] [30].

Recent advances in metabolomics technologies have created unprecedented opportunities for identifying food-specific compounds in biospecimens [7] [31]. The Dietary Biomarkers Development Consortium (DBDC) represents the first major systematic effort to leverage controlled feeding studies for biomarker discovery for foods commonly consumed in the United States diet [7] [9]. This article details the application of controlled feeding trials within the broader context of validating dietary assessment biomarkers.

The Role of Controlled Feeding Trials in Biomarker Discovery

Scientific Rationale and Advantages

Controlled feeding studies provide the methodological foundation for rigorous dietary biomarker validation by enabling researchers to:

- Establish causal relationships between specific food intake and metabolite appearance in biospecimens [7]

- Characterize pharmacokinetic parameters of candidate biomarkers, including onset, peak concentration, and clearance rates [7] [32]

- Determine dose-response relationships between food consumption levels and biomarker concentrations [32]

- Control for confounding factors from background diet, food preparation, and timing [29]

Unlike observational studies that rely on self-reported intake, controlled feeding trials provide precise quantification of exposure, which is essential for validating biomarkers against known intake amounts [29] [30]. This controlled environment allows researchers to distinguish metabolites that serve as specific markers of target foods from those influenced by other factors [7].

Key Consortium Initiatives and Study Designs

Major initiatives have established systematic frameworks for biomarker discovery through controlled feeding trials. The DBDC implements a structured 3-phase approach [7] [9]:

Additional study designs further expand on this framework:

- The mini-MED Trial: A 16-week randomized, multi-intervention, semi-controlled feeding study comparing a Mediterranean-amplified dietary pattern to a habitual Western pattern, specifically designed to evaluate food-specific compounds and cardiometabolic health [31]

- NPAAS Feeding Study: Employed individualized menu plans that approximated each participant's habitual diet to preserve normal variation in nutrient consumption while maintaining controlled conditions [29]

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Discovery

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Study Protocol

The DBDC Intervention Core implements rigorous PK studies to characterize the temporal profiles of food-derived metabolites [32]:

Study Design: Randomized, crossover trial where each participant completes feeding cycles for up to 8 test foods.

Test Foods: Chicken, beef, salmon, soybeans, yogurt, cheese, whole wheat bread, potatoes, corn, and oats [32].

Protocol Details:

- Participants consume a control diet for a 2-day run-in period

- Administer prespecified amount of test food

- Collect blood samples at time zero, every hour for 10 hours, and at 24 hours

- Collect urine samples at time zero, every 2 hours for 10 hours, and at 24 hours

- Analyze samples using untargeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) metabolomics [32]

Dose-Response (DR) Study Protocol

The DR protocol establishes quantitative relationships between food intake and biomarker levels [32]:

Study Design: Isocaloric, controlled feeding study with randomized crossover design examining three dose levels for 10 foods.

Population: 100 healthy adults (20 per food group pairing).

Food Pairings:

- Beef and potatoes

- Chicken and whole wheat bread

- Salmon and corn

- Cheese and soybeans

- Yogurt and oats

Experimental Sequence:

- Participants assigned to one of five food pairings

- Administer three dose levels (zero, medium, high) for each test food

- Each dose level maintained for six days

- Collect biospecimens throughout feeding periods for metabolomic analysis [32]

Biomarker Analytical Workflow

The metabolomic analysis follows a standardized workflow from sample collection to biomarker identification:

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of controlled feeding trials requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to nutritional biomarker research.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Dietary Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Test Foods | USDA MyPlate guidelines; specified varieties (e.g., salmon, oats, whole wheat bread) | Standardized dietary exposures for biomarker discovery [7] [32] |

| LC-MS Solvents | High-purity chromatographic grade solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, water) | Metabolite extraction and separation in untargeted metabolomics [7] |

| HILIC Columns | Hydrophilic-interaction liquid chromatography columns | Separation of polar metabolites complementary to reversed-phase LC-MS [7] |

| Stable Isotope Standards | (^{13})C, (^{15})N-labeled internal standards | Quantification and quality control in metabolomic analyses |

| Biospecimen Collection Systems | Standardized blood collection tubes (EDTA, heparin) and urine containers | Preservation of metabolite integrity during sample processing [7] |

Data Analysis and Statistical Approaches

Biomarker Performance Metrics

Controlled feeding studies generate quantitative data on biomarker performance characteristics. Analysis of serum concentration biomarkers in the NPAAS Feeding Study demonstrated varying capabilities to explain intake variation [29]:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Candidate Biomarkers from Controlled Feeding Studies

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarker | Variance Explained (R²) | Performance Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins | Serum Folate | 0.49 | Strong intake representation [29] |

| Serum Vitamin B-12 | 0.51 | Strong intake representation [29] | |

| Carotenoids | α-Carotene | 0.53 | Strong intake representation [29] |

| β-Carotene | 0.39 | Moderate intake representation [29] | |

| Lutein + Zeaxanthin | 0.46 | Strong intake representation [29] | |

| Lycopene | 0.32 | Moderate intake representation [29] | |

| Tocopherols | α-Tocopherol | 0.47 | Strong intake representation [29] |

| γ-Tocopherol | <0.25 | Weak intake association [29] | |

| Reference Biomarkers | Urinary Nitrogen (Protein) | 0.43 | Established recovery biomarker [29] |

| Doubly Labeled Water (Energy) | 0.53 | Established recovery biomarker [29] |

Statistical Methods for Biomarker Development

Advanced statistical approaches are required to account for measurement error and develop robust calibration equations: