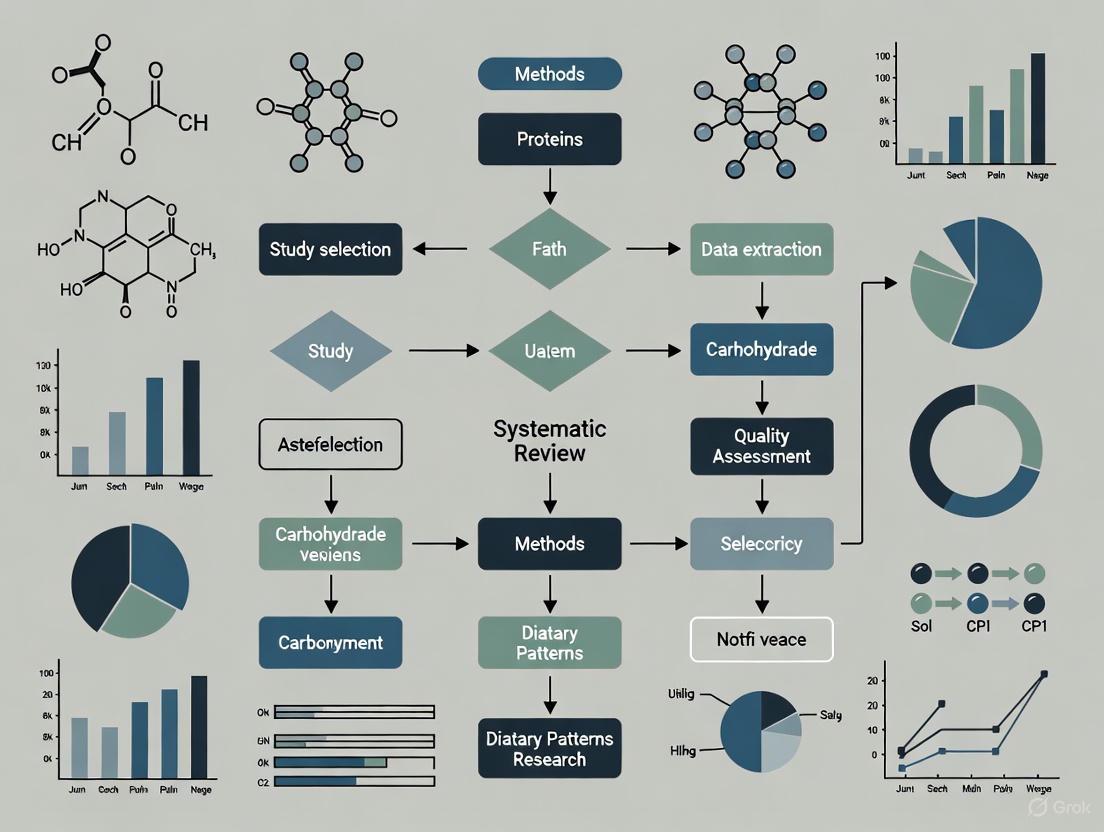

A Comprehensive Guide to Systematic Review Methods for Dietary Patterns Research

This article provides a detailed examination of systematic review methodologies specifically tailored for dietary patterns research, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Systematic Review Methods for Dietary Patterns Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed examination of systematic review methodologies specifically tailored for dietary patterns research, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, practical application of rigorous protocols like those from the USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR), strategies for overcoming common methodological challenges in evidence synthesis, and frameworks for validating and comparing findings across studies. By presenting current standards, best practices, and illustrative case studies—including the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee's approach—this guide aims to enhance the quality, consistency, and translational impact of systematic reviews in nutritional science and related biomedical fields.

Understanding the Role and Importance of Systematic Reviews in Dietary Patterns Research

Systematic reviews represent a rigorous and transparent approach to synthesizing scientific evidence, designed specifically to minimize bias and provide a comprehensive, objective assessment of available information on precise research questions [1]. Within the field of nutrition, this methodology has been adopted more recently to support the development of clinical guidelines, public health policies, and dietary recommendations [1] [2]. Unlike traditional narrative reviews, systematic reviews in nutrition employ protocol-driven methods to search for, evaluate, synthesize, and grade the strength of evidence, making them particularly valuable for identifying the state of science, recognizing knowledge gaps, and establishing research needs [1] [3]. The unique challenges of nutritional research—including considerations of baseline nutrient exposure, nutrient status, bioequivalence of bioactive compounds, bioavailability, and complexities in intake assessment—require specific methodological adaptations that distinguish nutrition systematic reviews from those in other biomedical fields [1].

Key Objectives of Systematic Reviews in Nutrition

The primary objective of systematic reviews in nutrition is to provide independent, science-based assessments that inform decision-making processes for researchers, policymakers, and guideline developers [1] [4]. These reviews aim to address precise research questions related to nutritional exposures and health outcomes through a structured process that minimizes subjectivity and bias. Specifically, they seek to support the development of science-based recommendations and guidelines, such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, by providing a comprehensive synthesis of the available evidence [1] [3] [5]. Another fundamental objective is to identify knowledge gaps and associated research needs, thereby setting agendas for future scientific inquiry [1]. Furthermore, these reviews establish a foundational evidence base that can be systematically updated as new data emerge, ensuring that dietary guidance remains current with the evolving scientific landscape [1].

Current Landscape and Quality Challenges

Despite their importance, systematic reviews of nutritional epidemiology studies often exhibit serious methodological limitations that can affect their reliability and usefulness. A 2021 cross-sectional study evaluating 150 systematic reviews and meta-analyses of nutritional epidemiology studies revealed several widespread quality concerns [6] [7]. The table below summarizes the key limitations identified in recent systematic reviews of nutritional epidemiology:

Table 1: Methodological Limitations in Systematic Reviews of Nutritional Epidemiology (n=150)

| Limitation Category | Specific Issue | Prevalence | Impact on Review Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Development | No preregistration of protocol | 80% (120/150) | Increases risk of selective reporting and post-hoc decisions |

| Search Methods | No replicable search strategy reported | 28% (42/150) | Compromises reproducibility and completeness |

| Evidence Synthesis | Did not consider dose-response when appropriate | 43.5% (50/115) | Misses important exposure-response relationships |

| Statistical Methods | Meta-analytic model selected based on heterogeneity | 26.1% (30/115) | Inappropriate model selection can distort findings |

| Evidence Grading | No established system for certainty of evidence | 89.3% (134/150) | Fails to communicate strength of conclusions |

The findings indicate that less than one-quarter of published systematic reviews in nutrition reported preregistration of a protocol, and almost one-third did not provide a replicable search strategy [6] [7]. Perhaps most concerning, only 10.7% used an established system to evaluate the certainty of evidence, which is crucial for appropriate interpretation of findings by end users [6] [7]. These limitations highlight the need for improved methodological rigor in nutrition systematic reviews, including greater involvement of statisticians, methodologists, and subject matter experts throughout the review process [6].

Methodological Framework and Protocol

Core Methodology

The USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) team has developed a gold-standard methodology specifically designed for food- and nutrition-related systematic reviews that informs Federal nutrition policies and programs [3] [5] [4]. This rigorous, transparent, and protocol-driven approach involves distinct phases that ensure comprehensive evidence assessment:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

For researchers conducting systematic reviews on dietary patterns, the following detailed protocols should be implemented:

Protocol Development and Registration

- Develop analytic framework: Create a visual representation linking populations, interventions/exposures, comparators, and outcomes to clarify research scope [1]

- Form multidisciplinary team: Include subject matter experts, methodologists, statisticians, and librarians to address all aspects of the review [6]

- Define eligibility criteria: Specify population characteristics, interventions/exposures (e.g., dietary patterns, specific foods, nutrients), comparators, outcomes, study designs, and timeframe [1] [8]

- Preregister protocol: Register the systematic review protocol in publicly available repositories such as Open Science Framework to enhance transparency and reduce reporting bias [6]

Search Strategy and Study Identification

- Comprehensive literature search: Search multiple electronic databases (e.g., PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane) using standardized search strategies developed by expert librarians [8]

- Supplemental searching: Examine reference lists of included studies, consult content experts, and search grey literature sources to identify additional relevant studies [6]

- Document search methodology: Report full search strategies for at least one database, including all search terms, Boolean operators, and filters to ensure reproducibility [6]

- Dual screening process: Implement independent screening of titles/abstracts and full-text articles by at least two reviewers using predetermined eligibility criteria, with procedures for resolving disagreements [8]

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

- Duplicate data extraction: Use standardized, pilot-tested data extraction forms with verification by a second reviewer to ensure accuracy [8]

- Extract key study characteristics: Document information on study design, participant characteristics, exposure/intervention details, comparator groups, outcome measures, results, and funding sources [8]

- Assess risk of bias: Employ validated tools appropriate to study design (e.g., ROBIS for systematic reviews, NHLBI tools for observational studies) to evaluate potential biases in individual studies [6] [8]

- Evaluate confounding consideration: Specifically assess how primary studies addressed potential confounding factors relevant to nutrition research [6]

Evidence Synthesis and Grading

Data Synthesis Methods

The synthesis of evidence in nutrition systematic reviews requires careful consideration of the unique aspects of nutritional data:

- Narrative synthesis: Develop structured summaries of findings, organized by key themes, participant populations, intervention/exposure characteristics, and outcome measures [8]

- Meta-analysis: When appropriate, conduct statistical pooling of results using random-effects models, accounting for expected heterogeneity across studies [1] [6]

- Investigate heterogeneity: Explore clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity through subgroup analyses and meta-regression [6]

- Dose-response analysis: When appropriate, evaluate dose-response relationships using established statistical methods rather than relying solely on categorical comparisons [6]

- Sensitivity analyses: Conduct analyses to test the robustness of findings to methodological decisions and potential biases [6]

Evidence Grading Systems

The NESR methodology includes a rigorous process for grading the strength of evidence, which is critical for ensuring that end users understand the level of certainty in conclusions when making decisions [5]. The process involves assessing evidence against five key elements and assigning one of four grades:

Table 2: NESR Evidence Grading Elements and Description

| Grading Element | Description | Assessment Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of Bias | Evaluation of systematic errors or limitations in design/conduct | Study design appropriateness, confounding control, exposure/outcome measurement, missing data, selective reporting |

| Consistency | Degree of similarity in effect sizes across studies | Direction, magnitude, and statistical significance of associations; explanation of inconsistencies |

| Directness | Linkage between body of evidence and review question | Population, intervention/exposure, comparator, and outcome applicability to research question |

| Precision | Degree of certainty around effect estimate | Sample size, number of events, confidence interval width |

| Generalizability | Applicability to population of interest | Demographic, geographical, and temporal representativeness; biological and behavioral plausibility |

Based on the comprehensive assessment against these five elements, the body of evidence receives one of four grades: Strong (high confidence that evidence reflects true effect), Moderate (moderate confidence), Limited (low confidence), or Grade Not Assignable (insufficient evidence) [5]. This grade is then clearly communicated through specific language in conclusion statements, such as "strong evidence demonstrates" or "limited evidence suggests" [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Methodological Reagents for Nutrition Systematic Reviews

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Analytic Framework | Visual mapping of key review elements | Links populations, exposures, comparators, outcomes, timing, and settings |

| Systematic Review Protocol | Blueprint for review conduct | Registered in repositories (e.g., Open Science Framework, PROSPERO) |

| Standardized Data Extraction Forms | Structured collection of study data | Electronic forms capturing design, methods, results, limitations |

| Risk of Bias Assessment Tools | Evaluate methodological quality of studies | ROBIS for systematic reviews, NHLBI tools for observational studies |

| Evidence Grading System | Assess certainty of body of evidence | NESR, GRADE, or other established systems with defined domains |

| Statistical Software Packages | Conduct meta-analyses and other syntheses | R (metafor, meta), Stata (metan), Comprehensive Meta-Analysis |

Application in Dietary Patterns Research: A Case Study

A recent systematic review conducted by the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on dietary patterns with ultra-processed foods and growth, body composition, and risk of obesity exemplifies the application of these methodological principles [8]. The review followed NESR's rigorous methodology, beginning with protocol development that specified the research question: "What is the relationship between consumption of dietary patterns with varying amounts of ultra-processed foods and growth, body composition, and risk of obesity?" [8]. The team established explicit eligibility criteria, including specific study designs (randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohort studies), population characteristics, intervention/exposure definitions, comparator groups, and outcome measures [8].

After comprehensive literature searches across multiple databases and dual screening of records, the reviewers extracted data and assessed risk of bias for each included study [8]. The evidence synthesis revealed different patterns across life stages: for children and adolescents, dietary patterns with higher amounts of ultra-processed foods were associated with greater adiposity and risk of overweight, with evidence graded as "limited" [8]. Similarly, for adults and older adults, limited evidence supported an association between higher ultra-processed food consumption and greater adiposity and obesity risk [8]. For infants and toddlers, however, the committee could not draw a conclusion due to substantial concerns with consistency and directness in the body of evidence [8]. This case study illustrates how systematic review methodology, when rigorously applied, can provide nuanced, life-stage-specific conclusions to inform dietary guidance while transparently acknowledging limitations in the evidence base.

The Critical Role of Systematic Reviews in Informing Dietary Guidelines and Public Health Policy

Systematic reviews represent the pinnacle of the evidence hierarchy in medical and public health research, serving as the fundamental scientific foundation for evidence-based dietary guidance worldwide [9]. These rigorous evidence syntheses utilize systematic, transparent, and protocol-driven methods to search for, evaluate, and synthesize all available literature on specific nutrition and health questions [3]. The process to develop the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), a cornerstone of federal nutrition policy and programs, relies heavily on systematic reviews conducted by appointed expert committees [10]. For the upcoming 2025-2030 edition, the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) has employed systematic reviews to examine high-priority scientific questions related to nutrition and health across the entire life course, from birth to older adulthood [3] [11]. This evidence-based approach ensures that public health recommendations reflect the preponderance of scientific evidence, thereby maximizing potential health impacts while minimizing bias in guidance development.

Methodological Framework: Protocol-Driven Evidence Synthesis

The Systematic Review Protocol as a Research Roadmap

A systematic review protocol serves as the critical planning document and roadmap for the entire evidence synthesis process, ensuring methodological rigor, transparency, and reproducibility [12] [13]. According to PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) standards, a comprehensive protocol must include defined criteria for screening literature, detailed search strategies for multiple databases, quality assessment tools, data extraction methods, and synthesis approaches [13]. The Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) team within the USDA supports the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee by employing a gold-standard methodology that includes developing a systematic review protocol before commencing any evidence examination [3] [10]. This protocol-driven approach mandates that reviewers establish their entire methodological framework—including inclusion/exclusion criteria, search strategies, and synthesis plans—before analyzing any evidence, thus preventing biased post-hoc decisions [10].

Table: Essential Components of a Systematic Review Protocol for Dietary Research

| Protocol Element | Description | Application in Dietary Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Rationale & Objectives | Background and specific research questions | Forms the basis for DGAC scientific questions |

| PICO Framework | Structured format (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) | Defines nutrition exposure and health outcomes [9] |

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Predefined study characteristics for selection | Ensures relevant life stages and health outcomes are examined |

| Search Strategy | Systematic literature search across multiple databases | NESR librarians search PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane [8] |

| Risk of Bias Assessment | Tools to evaluate methodological quality of individual studies | Uses design-specific tools for RCTs, cohort studies [9] |

| Data Synthesis Plan | Methods for combining evidence qualitatively or quantitatively | Grading evidence strength based on consistency, precision, risk of bias [8] |

Protocol Registration and Public Accessibility

Registering systematic review protocols in publicly accessible registries represents a critical step in promoting research transparency and reducing duplication of efforts. Multiple registration platforms exist, including PROSPERO (international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews), Open Science Framework (OSF), and specialized journals that publish protocols [12] [13] [14]. The 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee makes all systematic review protocols publicly accessible through NESR's website, documenting the planned methodology for each scientific question examined [3]. This commitment to transparency allows the broader scientific community to scrutinize methodological approaches, thereby enhancing the credibility of the resulting dietary recommendations.

Case Study: Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity Risk Across Life Stages

Systematic Review Methodology and Implementation

The 2025 DGAC's systematic review investigating the relationship between dietary patterns with varying amounts of ultra-processed foods and growth, body composition, and obesity risk exemplifies the rigorous application of systematic review methodology to a pressing public health question [8] [15]. The committee followed NESR's rigorous methodology, beginning with protocol development that specified the intervention/exposure as consumption of dietary patterns with ultra-processed foods compared to patterns without UPF, with outcomes focused on measures of growth, body composition, and obesity risk across all life stages [15]. NESR librarians executed comprehensive searches across four major databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane) for articles published between January 2000 and January 2024, with two analysts independently screening search results, extracting data, and conducting risk of bias assessments using standardized tools [8] [15]. The committee subsequently synthesized the evidence, developed conclusion statements, and graded the strength of evidence based on its consistency, precision, risk of bias, directness, and generalizability [8].

Diagram: Systematic Review Workflow for Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity Risk

Quantitative Findings and Evidence Grading

The systematic review on ultra-processed foods revealed distinct patterns of evidence across life stages, demonstrating how systematic reviews can identify both evidence-based relationships and critical knowledge gaps. For children and adolescents, the review included 25 articles (all prospective cohort studies) and concluded that dietary patterns with higher amounts of ultra-processed foods are associated with greater adiposity and risk of overweight, though this conclusion was graded as "Limited" due to methodological concerns across studies [8] [15]. Similarly, for adults and older adults, the review included 16 articles (15 prospective cohort studies, 1 RCT) and reached the same conclusion with a "Limited" grade, noting consistent direction of effects but variability in effect sizes and concerns with study design and conduct [15]. Importantly, the review identified critical evidence gaps for infants and young children (5 studies, conclusion not assignable), pregnancy (1 study, conclusion not assignable), and postpartum (2 studies, conclusion not assignable) [8].

Table: Evidence Synthesis on Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity Risk Across Life Stages

| Life Stage | Studies Included | Conclusion Statement | Evidence Grade | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants & Toddlers | 5 prospective cohort studies | No conclusion possible | Not Assignable | Substantial concerns with consistency and directness |

| Children & Adolescents | 25 prospective cohort studies | Higher UPF associated with greater adiposity and overweight risk | Limited | Small study groups, wide variance in effect estimates |

| Adults & Older Adults | 15 prospective cohort, 1 RCT | Higher UPF associated with greater adiposity and obesity risk | Limited | Few well-designed studies, dietary patterns examined not ideal |

| Pregnancy | 1 prospective cohort study | No conclusion possible | Not Assignable | Insufficient evidence available |

| Postpartum | 2 prospective cohort studies | No conclusion possible | Not Assignable | Insufficient evidence available |

Successful systematic reviews in nutrition research require specific methodological tools and resources to ensure comprehensive evidence identification, rigorous quality assessment, and appropriate synthesis. The research toolkit includes both conceptual frameworks and practical resources that guide the entire systematic review process.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nutrition-Focused Systematic Reviews

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in Systematic Review Process |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Development | PRISMA-P Checklist, NESR Methodology Manual | Provides standardized reporting framework and methodology [3] [13] |

| Literature Search | PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, CINAHL | Ensures comprehensive identification of relevant studies [8] [9] |

| Study Management | Covidence, Rayyan, EndNote | Streamlines screening, data extraction, and reference management [9] |

| Quality Assessment | Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Evaluates methodological rigor of included studies [9] |

| Evidence Grading | NESR Evidence Gradation System | Assesses body of evidence based on consistency, precision, risk of bias [8] |

| Protocol Registration | PROSPERO, Open Science Framework (OSF) | Publicly registers protocols to prevent duplication and reduce bias [12] [14] |

From Evidence to Policy: Translating Systematic Reviews into Dietary Guidance

The translation of systematic review findings into actionable public health policy represents the culmination of the evidence synthesis process. The Scientific Report of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee synthesizes conclusion statements from all systematic reviews to provide independent, science-based advice to the U.S. Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (HHS) [11]. These conclusion statements directly inform the development of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030, with the 2025 DGAC's report organized by critical topic areas including current dietary intakes, dietary patterns across life stages, beverage consumption, and strategies related to diet quality and weight management [11]. This translation from systematic review evidence to public health guidance ensures that nutrition recommendations reflect the most current scientific understanding while acknowledging limitations in the evidence base through graded conclusion statements.

Diagram: Evidence to Policy Pipeline for Dietary Guidelines

Recent research continues to demonstrate the importance of systematic reviews in informing dietary patterns for specific health outcomes. A 2025 study in Nature Medicine examining optimal dietary patterns for healthy aging utilized longitudinal data from the Nurses' Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, finding that higher adherence to healthy dietary patterns was associated with significantly greater odds of healthy aging [16]. Such findings reinforce how systematic reviews of multiple studies can identify consistent patterns across diverse populations and study designs, thereby providing robust evidence for public health recommendations that extend beyond disease prevention to encompass positive health outcomes like healthy aging.

Systematic reviews provide an indispensable methodological foundation for developing evidence-based dietary guidelines and public health policies. The rigorous, protocol-driven approach employed by the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee exemplifies how systematic methodology can synthesize complex scientific evidence across multiple life stages and health outcomes. As the field of nutrition science evolves, systematic reviews will continue to identify both evidence-based relationships and critical knowledge gaps, directing future research priorities while ensuring current public health recommendations reflect the most robust available evidence. The integration of systematic review findings into federal nutrition policy through the Dietary Guidelines for Americans demonstrates the practical application of this rigorous scientific process to improve public health outcomes across diverse populations.

In nutritional epidemiology, the analysis of dietary patterns has emerged as a superior approach to understanding the complex relationship between diet and health, moving beyond the limitations of studying single nutrients or foods in isolation. This holistic method accounts for the synergistic and cumulative effects of foods and nutrients as they are consumed in combination [17] [18]. Dietary pattern assessment methods are broadly categorized into a priori (hypothesis-driven) and a posteriori (exploratory, data-driven) approaches, each with distinct methodologies, applications, and interpretations [19] [20].

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in their underlying principles. A priori methods evaluate adherence to pre-defined dietary patterns based on existing scientific knowledge and dietary guidelines, such as the Mediterranean diet or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) [20]. In contrast, a posteriori methods use multivariate statistical techniques to derive dietary patterns directly from the consumption data of a specific study population, without pre-conceived hypotheses about what constitutes a healthy or unhealthy pattern [19] [20]. Within the context of systematic reviews, understanding these methodological distinctions is crucial for appropriately synthesizing evidence and drawing valid conclusions about diet-disease relationships.

Methodological Foundations and Comparative Analysis

A Priori (Index-Based) Methods

A priori approaches operate on predefined nutritional hypotheses, where researchers establish scoring criteria based on current scientific evidence about optimal dietary intake. These methods involve creating dietary indices or scores that reflect adherence to specific dietary patterns or guidelines [19] [20]. The Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI), Mediterranean Diet Score (MedDietScore), and Planetary Health Diet Index (PHDI) represent prominent examples of this approach [16]. These indices typically assign points based on consumption levels of beneficial foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, whole grains) and detrimental foods (e.g., red meat, sugary beverages), with higher scores indicating better dietary quality [17] [16].

The primary strength of a priori methods lies in their direct relevance to public health policy and dietary guidance, as they are designed to assess adherence to recommended eating patterns [21]. For instance, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet (assessed via a priori scoring) was associated with an 18% reduction in Parkinson's disease risk (RR = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.78–0.97), while healthy dietary indices showed an even stronger protective association (RR = 0.76; 95%CI: 0.65–0.91) [17]. Similarly, a 2025 large-scale cohort study found that the AHEI showed the strongest association with healthy aging, with participants in the highest quintile having 86% greater odds of healthy aging compared to those in the lowest quintile (OR = 1.86; 95% CI = 1.71–2.01) [16].

A Posteriori (Data-Driven) Methods

A posteriori approaches utilize statistical techniques to identify prevailing eating patterns within a specific dataset without pre-existing hypotheses about what these patterns might be. The most common techniques include principal component analysis (PCA), factor analysis, cluster analysis, and reduced rank regression (RRR) [19] [20]. These methods analyze intercorrelations between food items based on reported consumption data to identify combinations of foods that are frequently consumed together [19]. The derived patterns are often labeled descriptively based on their dominant food components, such as "Western pattern" (characterized by high consumption of red and processed meats, refined grains, and high-fat dairy) or "prudent pattern" (characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and poultry) [17].

The key advantage of a posteriori methods is their ability to identify population-specific dietary patterns that may reflect real-world eating behaviors without being constrained by nutritional hypotheses [19]. For example, the same meta-analysis that found protective effects of a priori patterns also identified through a posteriori methods that a "healthy dietary pattern" was associated with a 24% reduction in Parkinson's disease risk (RR = 0.76; 95%CI: 0.62–0.93), while a "Western dietary pattern" was associated with a 54% increased risk (RR = 1.54; 95%CI: 1.10–2.15) [17].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of A Priori and A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Assessment Methods

| Characteristic | A Priori Methods | A Posteriori Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Basis | Hypothesis-driven based on existing nutritional knowledge | Exploratory, data-driven from population dietary data |

| Methodology | Pre-defined scoring systems/indexes | Multivariate statistical techniques (PCA, factor analysis, cluster analysis) |

| Common Examples | Mediterranean Diet Score, AHEI, DASH, MIND, PHDI | "Western Pattern", "Prudent Pattern", "Traditional Pattern" |

| Output | Numerical score indicating adherence to predefined pattern | Pattern loadings identifying food combinations |

| Key Advantage | Direct relevance to dietary guidelines and policy | Identifies real-world eating patterns in specific populations |

| Primary Limitation | Dependent on current nutritional knowledge | Pattern labeling can be subjective; population-specific |

Table 2: Predictive Performance of A Priori vs. A Posteriori Patterns for Health Outcomes

| Health Outcome | Assessment Method | Performance Metric (C-statistic range) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Coronary Syndrome | A Priori | 0.587-0.807 | Multiple logistic regression showed best performance for both approaches [20] |

| A Posteriori | 0.583-0.827 | Equivalent classification accuracy between approaches [20] | |

| Ischemic Stroke | A Priori | 0.637-0.767 | Both methods showed similar predictive capability [20] |

| A Posteriori | 0.617-0.780 | Machine learning algorithms demonstrated high classification accuracy [20] | |

| Parkinson's Disease | A Priori (Mediterranean) | RR = 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | Significant risk reduction with higher adherence [17] |

| A Posteriori (Healthy Pattern) | RR = 0.76 (0.62-0.93) | Similar protective effect to a priori methods [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Dietary Pattern Assessment

Protocol 1: Implementing an A Priori Dietary Index

This protocol outlines the methodology for applying a predefined dietary index, such as the Mediterranean Diet Score (MedDietScore), within a research study. The protocol assumes dietary intake data has been collected using appropriate assessment tools (e.g., food frequency questionnaires, 24-hour recalls).

Step 1: Dietary Index Selection and Definition

- Select an appropriate a priori index based on research question and population

- Define all index components, including food groups, nutrients, or other dietary constituents

- Establish scoring criteria for each component, including cut-off points for consumption categories and direction of scoring (positive/negative)

- For Mediterranean diet assessment, define scoring for: high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains; moderate consumption of poultry, fish, alcohol; low consumption of red and processed meats [17]

Step 2: Data Transformation and Component Scoring

- Convert raw dietary intake data to standardized units (e.g., servings per day, grams per day)

- Classify each participant's consumption for each index component into predefined categories

- Assign component scores based on established criteria (typically 0-5 points per component)

- For the MedDietScore, assign higher points for greater adherence to Mediterranean diet principles [17]

Step 3: Total Score Calculation and Categorization

- Sum all component scores to create a total dietary index score

- Decide on appropriate categorization: continuous score, quartiles/quintiles, or predefined adherence categories (low/medium/high)

- Validate score distribution and address any skewness through appropriate transformations if needed

Step 4: Statistical Analysis

- Conduct reliability and validity assessments of the dietary index within the study population

- Employ multivariate regression models to examine associations between dietary index scores and health outcomes

- Adjust for potential confounders (age, sex, energy intake, physical activity, socioeconomic status)

This protocol was applied in a 2025 meta-analysis where adherence to the Mediterranean diet was quantified using predefined scores, revealing a significant inverse association with Parkinson's disease risk [17].

Protocol 2: Deriving A Posteriori Dietary Patterns Using Principal Component Analysis

This protocol details the application of principal component analysis (PCA) to derive dietary patterns from food consumption data, identifying common combinations of foods consumed in the study population.

Step 1: Data Preparation and Food Grouping

- Compile individual food items from dietary assessment into meaningful food groups (e.g., combine different types of red meat)

- Standardize intake of each food group (typically as grams/day adjusted for energy intake)

- Assess correlation matrix between food groups to confirm suitability for factor analysis

Step 2: Factor Extraction and Determination

- Perform principal component analysis with varimax rotation to eliminate correlation between factors

- Use multiple criteria to determine number of factors to retain: eigenvalues >1.5-2.0, scree plot examination, interpretability of factors

- Ensure retained factors explain a reasonable proportion of variance in food intake (typically 20-30% in dietary studies)

Step 3: Pattern Interpretation and Labeling

- Examine factor loadings (correlation coefficients between food groups and dietary patterns)

- Identify food groups with high loadings (typically >|0.2|-|0.3|) for each pattern

- Assign descriptive labels to patterns based on dominant food groups with high positive loadings

- Common patterns include "Western" (high positive loadings for red meat, processed foods, refined grains) and "Prudent/Healthy" (high positive loadings for fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish) [17]

Step 4: Pattern Score Calculation

- Compute factor scores for each participant for each identified pattern

- Use regression methods to calculate scores that represent each individual's adherence to each pattern

- Categorize participants by pattern score percentiles (quartiles/quintiles) for analysis

In the comparative analysis by Panagiotakos et al., this approach identified five principal components that explained 47.33% of the total variation in food intake, demonstrating the ability of a posteriori methods to capture key dietary dimensions in the population [20].

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Dietary Pattern Assessment

| Resource/Instrument | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvard FFQ [22] | Food Frequency Questionnaire | Large cohort studies | Semi-quantitative, >40 years of development, validated nutrient database |

| ASA-24 [23] | 24-hour Recall | Detailed intake assessment | Automated self-administered, reduces interviewer burden, multiple recalls possible |

| NCI Dietary Screener [24] | Short Instrument/Screener | Population surveillance | Rapid assessment of key dietary components (fruits, vegetables, fat, fiber) |

| MedDietScore [20] | A Priori Index | Mediterranean diet adherence | Validated tool assessing key Mediterranean diet components |

| AHEI Scoring System [16] | A Priori Index | Diet quality assessment | Based on Dietary Guidelines, strong predictive validity for chronic disease |

| FoodAPS [25] | National Survey Dataset | Food acquisition research | Comprehensive household food purchase and acquisition data |

Integration in Systematic Review Methodology

When conducting systematic reviews of dietary patterns research, specific methodological considerations must be addressed for proper evidence synthesis. The USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) branch has developed specialized approaches for analyzing and synthesizing dietary patterns research across life stages [21]. Key considerations include:

Operationalization of Definitions: Systematic reviews must establish clear, consistent definitions for different dietary patterns across included studies. This requires careful examination of how each primary study defined and measured "Mediterranean diet," "healthy dietary pattern," or other patterns of interest [19] [21]. Variations in the application of Mediterranean diet indices, including differences in dietary components (foods only vs. foods and nutrients) and cut-off point rationales (absolute vs. data-driven) present significant challenges for evidence synthesis [19].

Structured Synthesis Approaches: NESR employs standardized approaches for synthesizing evidence on dietary patterns, including:

- Separate synthesis for a priori and a posteriori methods

- Consideration of study design, population characteristics, and exposure assessment methods

- Transparent reporting of pattern definitions and methodological details from primary studies [21]

Quality Assessment in Dietary Patterns Research: Quality appraisal tools for dietary patterns research must evaluate:

- Dietary assessment method validity

- Appropriate control for energy intake and other confounders

- Transparency in pattern derivation and labeling (for a posteriori methods)

- Justification of index components and scoring (for a priori methods)

A critical finding from methodological research indicates that both a priori and a posteriori approaches achieve equivalent classification accuracy for predicting health outcomes across most statistical methods, supporting their complementary use in evidence synthesis [20].

Visualizing Dietary Pattern Assessment Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and methodological pathways in dietary pattern assessment for systematic reviews:

Dietary Pattern Assessment Decision Pathway

Both a priori and a posteriori dietary pattern assessment methods provide valuable, complementary approaches for understanding relationships between diet and health outcomes. The methodological frameworks and protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with standardized approaches for implementing these methods in primary research and systematically synthesizing evidence across studies. Future advances in dietary pattern assessment will benefit from improved standardization in reporting, integration of novel technologies for dietary assessment, and continued refinement of statistical approaches for pattern derivation and analysis [19] [21].

Current Gaps and Emerging Trends in the Dietary Patterns Evidence Base

Dietary patterns research has shifted from a focus on single nutrients to the complex combinations of foods and beverages that individuals habitually consume. This holistic approach can capture the synergistic and antagonistic effects of dietary components, providing a more complete picture of the relationship between diet and health [18] [26]. The evidence generated from this research forms the foundation for public health policies, including national dietary guidelines [27]. However, the methodological landscape for assessing and analyzing dietary patterns is rapidly evolving, presenting both significant challenges in evidence synthesis and promising new avenues for discovery. This article examines the current gaps in the dietary patterns evidence base and explores emerging trends and methodologies that are poised to address them, with a specific focus on implications for systematic review methodologies.

Current Gaps in the Evidence Base

A critical analysis of the current literature reveals several persistent gaps that hinder the synthesis of evidence and the development of robust, universally applicable dietary guidelines.

Methodological Heterogeneity and Reporting Inconsistencies

A primary challenge for systematic reviews in this domain is the considerable variation in how dietary pattern studies are conducted and reported.

Table 1: Key Methodological Gaps in Dietary Patterns Research

| Gap Area | Specific Challenge | Impact on Evidence Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Application of Methods | Inconsistent application of even established methods (e.g., Mediterranean diet indices use different components/cut-offs) [19]. | Difficulties in comparing and pooling results across studies. |

| Reporting of Methods | Omission of crucial methodological details in published research [19]. | Inability to assess study quality/reproducibility and model meta-biases. |

| Description of Patterns | Food and nutrient profiles of identified dietary patterns are often not fully reported [19]. | Limits understanding of what the pattern entails and its practical application. |

| Cultural Relevance | Lack of cultural tailoring of U.S. Dietary Guidelines (USDG) patterns for diverse ethnic groups, including African Americans [28]. | Reduces intervention acceptability, adherence, and effectiveness in real-world settings. |

| Equity Considerations | Insufficient focus on social determinants of health, like access to affordable, healthy foods [29]. | Guidelines and research may not address barriers faced by low-income and minority communities. |

A systematic review found that the application and reporting of dietary pattern assessment methods vary considerably, with important details often omitted [19]. This lack of standardization and transparency creates a fundamental barrier for evidence synthesis. For instance, the same dietary pattern label (e.g., "Mediterranean-style") may be defined differently across studies, leading to misclassification and confounding in meta-analyses. Furthermore, the failure to adequately describe the actual food and nutrient composition of identified patterns limits the translation of findings into actionable public health advice or clinical guidance.

The Cultural and Equity Chasm

Beyond methodological issues, a significant evidence gap exists regarding the cultural acceptability and equity of recommended dietary patterns. A qualitative study embedded within a randomized intervention (the DG3D study) found that African American adults identified a need for cultural adaptations to the standard U.S. Dietary Guidelines patterns to enhance relevance and adoption [28]. This suggests that the current evidence base, which often informs universal guidelines, may not adequately reflect the diverse cultural, culinary, and socioeconomic contexts of the population.

This is compounded by issues of access. Research synthesized by Healthy People 2030 highlights that a person's ability to maintain a healthy dietary pattern is heavily influenced by their neighborhood and built environment, including proximity to grocery stores, availability of transportation, and the affordability of nutrient-dense foods [29]. Disparities in access disproportionately affect low-income and racial/ethnic minority communities. Systematic reviews that fail to account for these contextual factors risk endorsing dietary patterns that are theoretically sound but practically inaccessible to large segments of the population.

Emerging Trends and Innovations

The field of dietary patterns research is dynamically responding to these challenges with technological and methodological innovations.

Novel Analytical Approaches

Researchers are increasingly moving beyond traditional a priori (index-based) and a posteriori (data-driven, e.g., factor analysis) methods to leverage more complex computational techniques.

Table 2: Emerging Trends in Dietary Patterns Research

| Trend Category | Specific Innovation | Potential Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Methods | Machine Learning (ML) algorithms, Latent Class Analysis (LCA), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) [26]. | Identifying complex, non-linear interactions within diets; uncovering novel sub-population patterns. |

| Focus on Healthspan | Multidimensional healthy aging as an outcome (cognitive, physical, and mental health) [16]. | Shifting focus from disease prevention to promotion of overall well-being and function in later life. |

| Personalized Nutrition | Tailoring dietary advice based on genetics, gut microbiome, and lifestyle [30]. | Moving beyond "one-size-fits-all" guidelines to improve individual-level adherence and efficacy. |

| Sustainable Nutrition | Integrating environmental impact (e.g., Planetary Health Diet Index) with health outcomes [31] [16]. | Developing dietary recommendations that support both human and planetary health. |

| Addressing Food Tech | Research on the health impacts of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and alternative proteins [30] [16]. | Informing guidelines on modern food categories and new protein sources. |

A scoping review notes a growing use of these "novel methods," including machine learning algorithms and latent class analysis, to characterize dietary patterns with greater depth and account for their multidimensional and dynamic nature [26]. These approaches can handle high-dimensional dietary data and uncover complex, non-linear relationships that traditional methods might miss, potentially leading to more precise and personalized dietary insights.

Expanding Outcome Domains: Healthspan and Sustainability

There is a paradigm shift in the health outcomes being studied. A landmark 2025 study in Nature Medicine examined the association between dietary patterns and "healthy aging," defined multidimensionally as surviving to age 70 free of major chronic diseases and with intact cognitive, physical, and mental health [16]. The study found that diets like the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) and a healthful plant-based diet were strongly associated with greater odds of healthy aging. This represents a move beyond siloed disease outcomes towards a holistic view of health and function.

Concurrently, the concept of sustainable nutrition is becoming a central focus. This involves designing dietary patterns that are not only healthy but also have a low environmental impact, are accessible, affordable, and culturally acceptable [31]. Indices like the Planetary Health Diet Index (PHDI) are being developed and validated, and research is increasingly linking them to positive health outcomes, as seen in the healthy aging study [16].

Diagram 1: Evolving workflow for dietary pattern analysis, showing the integration of emerging methods alongside traditional approaches. ML: Machine Learning.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for addressing the identified gaps and incorporating emerging trends into research practice.

Protocol for Culturally Tailoring Dietary Pattern Interventions

Based on the DG3D study [28], the following protocol can be used to enhance the cultural relevance of dietary guidelines for specific populations.

Objective: To adapt the composition, messaging, and delivery of a standardized dietary pattern intervention to improve acceptability and adherence within a target cultural group.

Procedure:

- Intervention Delivery: Conduct a controlled intervention where participants from the target population (e.g., African American adults) are randomized to follow one of several evidence-based dietary patterns (e.g., Healthy US, Mediterranean, Vegetarian) using unmodified, standard guidelines-based materials for a set period (e.g., 12 weeks).

- Qualitative Data Collection: Upon intervention completion, conduct focus group discussions (FGDs) with participants. The FGD guide should be grounded in theoretical frameworks (e.g., Social Cognitive Theory) and cover:

- Experiences with and acceptability of the assigned diet.

- Perceived barriers and facilitators to adoption.

- Cultural relevance of recommended foods, recipes, and portion sizes.

- Suggested modifications to improve cultural fit and implementation.

- Data Analysis: Thematically analyze verbatim transcripts from FGDs using a constant comparative method in qualitative data analysis software (e.g., NVivo). Identify emergent themes related to cultural acceptance.

- Intervention Adaptation: Use the qualitative findings to inform revisions to the intervention. This may include:

- Recipe Modification: Incorporating traditional foods and culturally preferred cooking methods.

- Messaging Adjustment: Using culturally resonant language, imagery, and communication channels.

- Support Structure: Tailoring the intervention delivery (e.g., group sessions, chef demonstrations) to align with community norms.

Protocol for Integrating Novel Methods in Dietary Pattern Analysis

This protocol outlines the application of machine learning and latent variable models to characterize complex dietary patterns, addressing methodological gaps [26].

Objective: To identify complex dietary patterns and their associations with health outcomes using novel, data-driven methods that capture multidimensionality and interactions.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile a high-dimensional dietary dataset, typically from Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) or 24-hour recalls. Preprocess data by standardizing servings, energy-adjusting, and aggregating into meaningful food groups.

- Method Selection: Choose an appropriate novel analytical method based on the research question.

- Latent Class Analysis (LCA): A model-based approach to identify unobserved subgroups (classes) of individuals with similar dietary habits. Ideal for discovering distinct dietary typologies within a population.

- Machine Learning (ML) Algorithms: Such as Random Forests or Neural Networks, to model complex, non-linear relationships between a wide array of dietary inputs and a specific health outcome.

- Model Training & Validation: Split the dataset into training and testing sets. Train the selected model on the training set and evaluate its performance (e.g., predictive accuracy, class stability) on the withheld testing set to ensure robustness and avoid overfitting.

- Interpretation & Validation: Interpret the resulting patterns or models. For LCA, describe each class by its characteristic food intake profile. For ML, use feature importance metrics to identify which dietary components are most strongly associated with the outcome. Validate the derived patterns against demographic, socioeconomic, or biological data to ensure they are meaningful and actionable.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Advanced Dietary Patterns Research

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NVivo | Facilitates the organization and thematic analysis of qualitative data from focus groups or interviews, crucial for cultural adaptation studies [28]. | Used to code transcripts and identify emergent themes systematically. |

| Dietary Assessment Software | Automates the collection and initial processing of dietary intake data (e.g., ASA24, NDS-R). | Reduces manual entry error and provides a structured data export for analysis. |

| Statistical Software with ML Capabilities | Provides the computational environment for applying novel methods (e.g., LCA, Random Forests). | R (with packages like poLCA, randomForest), Python (with scikit-learn). |

| Healthy Aging Assessment Tools | Operationalizes the multidimensional outcome of healthspan, as used in recent cohort studies [16]. | Includes validated tools for cognitive function (e.g., MMSE), physical function (e.g., gait speed), and mental health (e.g., CES-D) assessments. |

| Food Environment Data | Geospatial data on food access (e.g., location of supermarkets, fast-food outlets) to quantify a key social determinant of health [29]. | USDA's Food Access Research Atlas; commercially available location data. |

Diagram 2: Proposed pathways linking dietary patterns to multidimensional health outcomes, highlighting key mechanistic areas for research. GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide-1.

The evidence base for dietary patterns is at a pivotal juncture. While significant gaps in methodological standardization, reporting, and cultural relevance continue to challenge systematic reviewers and guideline developers, emerging trends offer powerful solutions. The integration of novel analytical techniques like machine learning, a renewed focus on holistic outcomes like healthspan, and a commitment to sustainable and equitable nutrition are reshaping the field. For systematic review methodologies to remain relevant, they must evolve to appraise and synthesize studies employing these diverse and complex approaches. Future work must prioritize the development of reporting standards that encompass both traditional and novel methods, actively incorporate qualitative insights on cultural acceptability, and systematically account for the social determinants of health. By doing so, the research community can generate dietary evidence that is not only scientifically robust but also equitable, actionable, and effective in promoting health for all populations.

Implementing Rigorous Protocols: A Step-by-Step Guide to Systematic Review Methodology

In the field of dietary patterns research, the adoption of gold-standard methodologies for evidence synthesis is paramount for generating reliable, transparent, and actionable public health guidance. A rigorously developed and publicly registered protocol forms the bedrock of a high-quality systematic review, serving as a safeguard against bias and ensuring the reproducibility of the scientific process. This document delineates the core components of such a protocol, framed within the context of systematic review methods for dietary patterns research. The procedures outlined herein are aligned with the methodology employed by the Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) team, which supports the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) in developing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans [32] [3]. This protocol provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for conducting systematic reviews that meet the highest standards of scientific rigor.

Methodological Framework

Phase 1: Scientific Question Formulation

The initial phase involves the precise formulation of the scientific question to be examined. This is a critical step that determines the scope and direction of the entire systematic review.

- Criteria for Question Prioritization: Proposed scientific questions must satisfy several key criteria to be considered for a systematic review [33].

- Relevance: The question must fall within the scope of food-based recommendations, not clinical guidelines for medical treatment.

- Importance: The question should address an area of substantial public health concern, uncertainty, and/or knowledge gap.

- Potential Impact: There should be a high probability that the answer will inform federal food and nutrition policies and programs.

- Avoiding Duplication: The question should not be addressed by existing or planned evidence-based federal guidance.

- Public Engagement and Transparency: To ensure broad relevance and minimize bias, the proposed scientific questions are made available for public comment. For the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines, a 30-day public comment period was provided, allowing for input from the broader scientific community and the public [33]. This transparent process helps refine the questions and ensures they address pressing public health needs.

Table 1: Characteristics of High-Priority Scientific Questions in Dietary Patterns Research

| Characteristic | Description | Example from 2025 DGAC |

|---|---|---|

| Public Health Importance | Addresses a health condition of substantial public health burden or a key knowledge gap. | Relationship between dietary patterns and risk of cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease [32]. |

| Relevance to Guidance | Likely to provide the scientific foundation for food-based dietary guidance. | Relationship between food sources of saturated fat and risk of cardiovascular disease [32]. |

| Life Stage Applicability | Considers the applicability of the question across the life course, from infancy to older adulthood. | Current intakes of food groups and nutrients, and prevalence of nutrition-related chronic conditions [32] [33]. |

| Health Equity Consideration | Reviewed with a health equity lens to ensure guidance is inclusive of diverse populations [33]. | Examination of relationships across diverse racial/ethnic groups and socioeconomic positions [34]. |

Phase 2: Protocol Development and Public Registration

Once a question is finalized, the next critical step is the development and public registration of a detailed systematic review protocol. This pre-established plan is essential for maintaining transparency and minimizing arbitrary decision-making during the review process.

- Protocol Components: A gold-standard protocol explicitly defines [32] [3]:

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Specific details on the study designs (e.g., randomized controlled trials, prospective cohort studies), population characteristics, interventions/exposures (e.g., consumption of specific dietary patterns), comparators, and health outcomes that will be considered.

- Search Strategy: The electronic databases to be searched (e.g., PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane) and the precise search terms and filters.

- Data Extraction and Synthesis Plan: A predefined plan for the data to be extracted from each study and the methods for synthesizing the evidence (e.g., qualitative synthesis).

- Risk of Bias Assessment: The specific tools and methods that will be used to evaluate the methodological quality of each included study.

- Public Accessibility: The finalized protocol is made publicly available online before the review commences [32] [3]. This allows for scrutiny by other experts and the public, and it ensures the review team adheres to the pre-specified plan, preventing post-hoc changes that could introduce bias.

Phase 3: Evidence Synthesis and Review

This phase involves the execution of the published protocol. It is a collaborative and iterative process designed to be comprehensive and minimize individual reviewer bias.

- Literature Search and Screening: NESR librarians perform the literature search across multiple databases using the predefined strategy. Two NESR analysts then independently screen the search results against the inclusion and exclusion criteria [34].

- Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment: Data from each included article is extracted by one analyst and verified for accuracy by a second. Two analysts independently assess the risk of bias for each study using standardized tools, with any differences reconciled through discussion [3] [34].

- Evidence Synthesis and Conclusion Statement Development: The evidence is synthesized according to the pre-specified plan. The committee then develops conclusion statements that directly answer the systematic review question. These statements are graded based on the strength of the underlying body of evidence, considering factors like consistency, precision, risk of bias, directness, and generalizability [3] [34].

Diagram 1: Workflow of a gold-standard systematic review protocol.

Phase 4: Quality Assurance and Peer Review

A defining feature of a gold-standard process is an robust, multi-layered system of quality assurance and peer review.

- Internal Reconciliation: All key steps, including screening and risk of bias assessments, are performed independently by at least two analysts, with differences reconciled to ensure consensus [34].

- External Peer Review: The completed systematic reviews undergo a formal external peer review process. This is often coordinated by independent bodies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and involves federal scientists and external experts who scrutinize the work [3].

- Public Deliberation: The DGAC conducts its discussions and presents its findings in a series of public meetings. This "pulls back the curtain" on the process, allowing for real-time transparency and building public trust in the final recommendations [32].

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology for a Systematic Review on Dietary Patterns

The following detailed methodology is adapted from the 2025 DGAC's systematic review on "Dietary Patterns and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease" [34].

Objective: To answer the question: "What is the relationship between dietary patterns consumed and risk of cardiovascular disease?"

Protocol Registration: The systematic review protocol was developed and published in advance on the NESR website [3].

Eligibility Criteria:

- Study Designs: Randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and nested case-control studies.

- Publication Status: Published in English in peer-reviewed journals.

- Population: Studies in countries with high or very high Human Development Index; participants with a range of health statuses. Studies exclusively enrolling participants undergoing treatment for a disease were excluded.

- Intervention/Exposure: Consumption of a dietary pattern compared to a different dietary pattern or different levels of adherence.

- Outcomes: Incidence of cardiovascular disease events, cardiovascular mortality, and cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., blood pressure, blood lipids).

Literature Search:

- Databases: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane.

- Date Range: Searches were conducted for articles published between October 2019 and May 2023 for children/adolescents, and between January 2014 and May 2023 for adults/older adults. Results were combined with eligible articles from existing reviews.

Data Extraction and Management:

- Two analysts independently extracted data on study design, population characteristics, dietary pattern details, outcomes, and results.

- A standardized data extraction form was used to ensure consistency.

Risk of Bias Assessment:

- Two analysts independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study using validated tools specific to the study design (e.g., Cochrane Risk of Tool for randomized trials, NHLBI tools for observational studies).

- Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Data Synthesis:

- A qualitative synthesis was performed due to heterogeneity in dietary patterns and outcomes.

- The synthesis focused on overarching themes, key concepts, and the direction and consistency of findings.

Conclusion Grading:

- The strength of evidence was graded as Strong, Moderate, Limited, or Grade Not Assignable based on the consistency, precision, and risk of bias of the included studies.

Table 2: Data and Outcomes from a Systematic Review on Dietary Patterns and CVD [34]

| Population | Conclusion Statement | Evidence Grade | Number of Included Articles | Key Dietary Pattern Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children & Adolescents | Associated with lower systolic & diastolic blood pressure and triglycerides later in life. | Moderate | 19 (1 RCT, 18 cohorts) | Higher in vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, fish; lower in red/processed meats, SSBs. |

| Adults & Older Adults | Associated with lower risk of CVD, including improved blood lipids and blood pressure. | Strong | 110 (9 RCTs, 101 cohorts) | Higher in vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, unsaturated fats; lower in sodium, red/processed meat, refined grains, SSBs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Conducting a systematic review in nutritional epidemiology requires a suite of methodological "reagents" and resources. The following table details essential tools and platforms used in gold-standard processes like the NESR methodology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Systematic Reviews

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| NESR Methodology Manual [3] | Methodological Guide | A comprehensive manual detailing gold-standard protocols for conducting and updating systematic reviews and evidence scans in nutrition. |

| Bibliographic Databases (e.g., PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane) [34] | Electronic Resource | Platforms used to perform comprehensive, protocol-driven literature searches to identify all relevant peer-reviewed studies. |

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [32] | Data Source | A program of studies that combines interviews and physical examinations to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population; used for intake and prevalence analyses. |

| Risk of Bias Assessment Tools (e.g., Cochrane RoB 2, NHLBI Tools) [34] | Analytical Tool | Standardized checklists used to critically appraise the methodological quality and potential for bias in individual included studies. |

| USDA's Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) Team [32] [3] | Expert Resource | A team of public health and nutrition scientists with advanced training in systematic review methodology who provide scientific and technical support. |

| Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) [32] | Expert Committee | An independent, federally appointed committee of 10-20 nutrition and health experts responsible for reviewing evidence and writing the Scientific Report. |

Systematic reviews represent the gold standard for evidence synthesis in nutritional epidemiology, forming the foundational science behind food-based dietary guidelines and health policies [3]. The field of dietary patterns research has evolved significantly, moving from a focus on single nutrients to the complex analysis of whole diets, capturing the synergistic relationships between multiple foods and beverages [35] [36]. This shift necessitates increasingly sophisticated methodological approaches for evidence synthesis. A comprehensive search strategy—encompassing deliberate database selection, meticulously constructed search strings, and thorough grey literature searching—is paramount to ensuring the systematic review is both reproducible and minimally biased. This protocol details evidence-based methodologies for developing such search strategies, framed within the context of systematic reviews investigating dietary patterns and their associations with health outcomes.

Core Principles of a Systematic Search

A systematic review search aims for high sensitivity (retrieving all potentially relevant records) over specificity, accepting that this will yield a larger volume of irrelevant records for later screening [37] [38]. This approach minimizes the risk of missing key studies and introducing selection bias. The process is iterative and should be documented with enough detail to be fully replicable [38]. The PRISMA-S extension provides specific guidance for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews [38].

Database Selection for Dietary Patterns Research

Searching multiple bibliographic databases and other sources is critical due to variations in their coverage. The following table summarizes core and specialized resources for dietary patterns research.

Table 1: Database Selection for Dietary Patterns Systematic Reviews

| Database Category | Recommended Resources | Justification and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Core Bibliographic Databases | MEDLINE (via PubMed or Ovid), Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, Web of Science [37] [38] [39] | MEDLINE and Embase are essential for biomedical topics; CENTRAL is key for interventions; Scopus and WoS are multidisciplinary and provide strong citation tracking. |

| Specialized & Regional Databases | CINAHL, Global Health, IndMED, CNKI, Wanfang, VIP [40] [39] | Selected based on review topic to cover specific disciplines (e.g., CINAHL for nursing) or geographical regions (e.g., Chinese databases for studies in China). |

| Grey Literature Sources | ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, organizational websites (e.g., FAO, WHO, World Bank) [40] [41] [38] | Essential for locating unpublished, ongoing, or non-commercially published studies to mitigate publication bias. |

Developing High-Sensitivity Search Strings

Identifying Search Concepts and Terms

Search strings are built by combining synonyms and related terms for each core concept in the research question, typically structured using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework [37].

- Keywords: Identify natural language terms from seminal papers, reviews, and preliminary searches. Consider spelling variants (e.g., behavior/behaviour) and plurals [37] [38].

- Index Terms: Use controlled vocabularies like Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in MEDLINE and Emtree in Embase. Index terms are assigned by subject experts and can retrieve articles that use different wording in their titles/abstracts [38].

Table 2: Search Term Development for Dietary Patterns Concepts

| Concept | Keyword Examples | Index Term Examples (MeSH) |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Patterns | "dietary pattern", "eating pattern", "diet habit", "food pattern" | "Feeding Behavior"[Mesh], "Diet"[Mesh] |

| Specific Diets | "Mediterranean diet", "DASH diet", "vegan diet", "ketogenic diet", "plant-based" [16] [39] | "Diet, Mediterranean"[Mesh], "Diet, Vegetarian"[Mesh] |

| Analysis Methods | "principal component analysis", "PCA", "factor analysis", "cluster analysis", "latent class analysis", "reduced rank regression", "machine learning" [35] [40] [36] | "Statistical Factor Analysis"[Mesh] |

Search String Syntax and Techniques

Effective use of syntax tools is required to structure the search accurately. The specific operators vary by database and must be checked in the database's "help" or "search tips" section [42].

- Boolean Operators: Combine search concepts.

ORcombines synonyms within a concept to broaden the search (e.g., "Diet, Mediterranean" OR "Mediterranean diet").ANDcombines different concepts to narrow the search (e.g., Dietary Patterns AND Health Outcomes).NOTexcludes terms (use with extreme caution as it may inadvertently exclude relevant records) [42] [38].

- Truncation (*): Searches for multiple word endings. (e.g.,

pattern*retrieves pattern, patterns). - Wildcards (?, #): Account for spelling variations within a word (e.g.,

wom?nretrieves woman and women). - Phrase Searching ("): Ensures words are searched as an exact phrase (e.g., "systematic review") [42].

- Proximity Operators (N/n, W/n): Search for terms within a specified number of words of each other, regardless of order (N) or in order (W). (e.g.,

dietary N3 pattern*) [42].

Building the Search Strategy

A robust search strategy combines all concepts using the identified syntax.

- Line-by-Line Construction: Build each conceptual block separately using

OR, then combine the blocks withAND.- Line 1: [All Index Terms for Dietary Patterns]

- Line 2: [All Keywords for Dietary Patterns]

- Line 3: #1 OR #2

- Line 4: [All Terms for Health Outcome]

- Line 5: #3 AND #4

- Validation: Test the search strategy by verifying it retrieves a set of "sentinel articles" (key papers known to be relevant) [37]. Refine the strategy if these articles are not found.

- Adaptation: Translate the finalized strategy for each database, accounting for differences in syntax and controlled vocabularies [38].

Diagram 1: Search String Development Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential and iterative process of building a systematic review search strategy.

Grey Literature Search Protocol

Grey literature is crucial for combating publication bias, as studies with null or negative results are less likely to be published in traditional journals [38].

- Clinical Trial Registries: Search platforms like ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for ongoing or completed but unpublished studies.

- Theses and Dissertations: Search ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global and other national thesis databases.

- Government and Organizational Reports: Manually search websites of relevant bodies (e.g., USDA, FAO, WHO, World Bank, International Food Policy Research Institute) [40] [41].

- Conference Abstracts: Search databases that index conferences or directly search websites of major professional societies' past meetings.

Search Strategy Workflow and Documentation

A structured workflow ensures a thorough and transparent search process.

Table 3: Search Execution and Documentation Protocol

| Step | Action | Documentation Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Finalize search strategy for one database (e.g., MEDLINE). | Record full strategy with date. |

| 2. Translation | Adapt the strategy for all other selected databases. | Save a copy of each final strategy per database. |

| 3. Execution | Run searches and export records. | Record the date of search and number of records retrieved from each source. |

| 4. Deduplication | Combine results and remove duplicate records using reference management software (e.g., EndNote) or systematic review tools (e.g., Covidence) [38]. | Record the software used and the number of records before and after deduplication. |

| 5. Reporting | Write up the methodology. | Include the full search strategy for at least one database as an appendix; report according to PRISMA-S guidelines [38]. |

Diagram 2: Search Results Management Workflow. This diagram visualizes the process of collating and managing records from multiple sources prior to the screening stage.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Systematic Searching

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Boolean Operators (AND, OR, NOT) | Search Syntax | Logically combine and exclude search terms to broaden or narrow results [42] [38]. |

| Truncation (*) | Search Syntax | Expands a search to include all word endings (e.g., pattern* finds pattern, patterns) [42]. |

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | Vocabulary Tool | The NIH NLM's controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles in PubMed/MEDLINE [38]. |

| Covidence | Review Management | A web-based tool that streamlines title/abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction among a team [38]. |

| PRISMA Statement & Flow Diagram | Reporting Guideline | An evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The flow diagram tracks the study selection process [38]. |

| EndNote | Reference Management | Software to store, manage, and deduplicate bibliographic references, and format citations for manuscripts. |

| Validated Search Filters | Search Aid | Pre-tested search strings designed to find specific study types (e.g., RCTs), available from resources like the ISSG Search Filter Resource [37]. |

In the evolving landscape of scientific research, standardized protocols have emerged as a fundamental requirement for ensuring the reproducibility and credibility of systematic reviews, particularly in nutrition and dietary patterns research. The increasing volume of scientific literature—with over 2.295 million scientific and engineering articles published worldwide in 2016 alone—has created a complex research environment where transparent methodology is essential for synthesizing reliable evidence [43]. Within dietary patterns research, this standardization is especially crucial due to the subjective decisions researchers must make regarding dietary pattern assessment methods, including decisions about dietary components, cut-off points for scoring, and the number of dietary patterns to retain for analysis [44].