A Practical Framework for Validating Nutrition-Related Machine Learning Models: From Data to Clinical Deployment

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and healthcare professionals on validating machine learning (ML) models in nutrition.

A Practical Framework for Validating Nutrition-Related Machine Learning Models: From Data to Clinical Deployment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and healthcare professionals on validating machine learning (ML) models in nutrition. Covering foundational principles, methodological approaches, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques, it addresses the entire model lifecycle. Using real-world case studies, such as predicting malnutrition in ICU patients, and insights from recent literature (2024-2025), we outline best practices for ensuring model robustness, generalizability, and clinical applicability. The content is tailored to equip scientists and drug development professionals with the knowledge to build, evaluate, and implement trustworthy AI tools in nutrition science and biomedical research.

Core Principles and Data Foundations for Nutrition AI

Nutrition research is undergoing a fundamental transformation, driven by the generation of increasingly complex and high-dimensional data. Understanding the relationship between diet and health outcomes requires navigating datasets that are not only vast but also inherently multimodal, combining diverse data types from genomic sequences to dietary intake logs [1]. These characteristics present significant methodological challenges for researchers applying machine learning (ML) models, particularly in the critical phase of model validation [2]. This guide objectively compares the performance of analytical approaches and computational tools designed to overcome these challenges, providing researchers with a framework for validating robust and reliable nutrition models.

Core Challenges in Nutrition Data Analysis

The path to valid ML models in nutrition is paved with three interconnected data challenges that directly impact analytical performance and require specific methodological approaches to overcome.

Data Complexity and High-Dimensionality

Nutritional data is characterized by a high number of variables (p) often exceeding the number of observations (n), creating the "curse of dimensionality" that plagues many analytical models.

Characteristics and Impact: This high-dimensionality arises from several sources, including detailed nutrient profiles, omics technologies (genomics, metabolomics), and microbiome compositions [1]. Traditional statistical methods, which assume well-established, low-dimensional features, often fail to capture the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in such data [1]. This can lead to models with poor predictive performance when applied to new data.

Performance Comparison: Studies consistently show that ML ensemble methods like Random Forest and XGBoost outperform traditional classifiers and regressors that assume linearity, particularly for predicting outcomes like obesity and type 2 diabetes [1]. For instance, when predicting mortality with epidemiologic datasets, the nonlinear capabilities of sophisticated ML techniques explain their consistently superior performance compared to traditional statistical models [1].

Data Multimodality

Multimodal data integrates information from multiple, structurally different sources to provide a holistic view of a subject's health and nutritional status.

Characteristics: A comprehensive patient record, for example, can combine structured data (demographics, lab results), unstructured text (clinical notes), imaging data (X-rays, MRIs), time-series data (vital signs, glucose monitoring), and genomic sequences [3]. Each modality has its own structure, scale, and semantic properties, requiring different storage formats and preprocessing techniques [3].

Performance Advantage: The primary technical advantage of multimodal systems is redundancy; they maintain performance even when one data source is compromised [3]. Furthermore, models trained on diverse, complementary data types consistently outperform unimodal alternatives. A study on solar radiation forecasting found a 233% improvement in performance when applying a multimodal approach compared to using unimodal data [3].

Data Quality and Measurement Error

The validity of any model is contingent on the quality of the data it is built upon. Nutrition research is particularly susceptible to measurement errors.

Primary Challenge: The largest source of measurement error in nutrition research is self-reported energy intake, which is not objective and can be unreliable without triangulation with other methods [2]. Additionally, data from devices like accelerometers can be extremely noisy compared to gold standard methods [2].

Impact on Validation: Measurement error can render model results meaningless, imprecise, or unreliable [2]. This creates a significant challenge for model validation, as predictions may be based on flawed input data. Explainable AI (xAI) models are key to understanding how measurement error propagates through a model's predictions [2].

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies and Performance

Different analytical strategies offer varying performance advantages for tackling the specific challenges of nutrition data. The table below summarizes experimental data comparing these approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Approaches for Nutrition Data Challenges

| Analytical Challenge | Methodology/Algorithm | Comparative Performance Data | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Dimensionality | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) + t-SNE [4] | Improved clustering accuracy and visualization quality vs. state-of-the-art methods [4] | Effectively simplifies extensive nutrition datasets; enhances selection of nutritious food alternatives. |

| High-Dimensionality | Ensemble Methods (Random Forest, XGBoost) [1] | Consistently superior to linear classifiers/regressors [1] | Better represents complex, non-linear data generation processes in areas like obesity and omics. |

| Multimodal Integration | Orthogonal Multimodality Integration and Clustering (OMIC) [5] | ARI: 0.72 (CBMCs), 0.89 (HBMCs); Computationally more efficient than WNN, MOFA+ [5] | Accurately distinguishes nuanced cell types; runtime of 34.99s vs. 1247.69s for totalVI on HBMCs dataset. |

| Multimodal Integration | Weighted Nearest Neighbor (WNN) [5] | ARI: 0.71 (CBMCs), 0.94 (HBMCs) [5] | Performs well but can merge certain cell types; cell-specific weights are difficult to interpret. |

| Multimodal Integration for Prediction | U-net + SVM for Facial Recognition [6] | 73.1% accuracy predicting NRS-2002 nutritional risk score [6] | Provides a non-invasive assessment method; accuracy higher in elderly (85%) vs. non-elderly (71.1%) subgroups. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol: Dimensionality Reduction for Nutritional Insights

This methodology employs a combination of techniques to simplify high-dimensional nutrition data for analysis and visualization [4].

- 1. Data Preparation: Collect a high-dimensional dataset, such as one detailing the nutritional content of various foods.

- 2. Dimensionality Reduction: First, apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to transform the original variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated components that capture the maximum variance. Subsequently, use t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) on the principal components to further reduce the data to 2 or 3 dimensions for visualization, preserving local data relationships [4].

- 3. Cluster Optimization: Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means) to the reduced data. Use hyperparameter tuning techniques, specifically the Elbow Method and the Silhouette Coefficient, to determine the optimal number of clusters [4].

- 4. Analysis: Analyze the resulting clusters to identify distinct nutritional patterns or food groupings, simplifying the selection of nutritious alternatives.

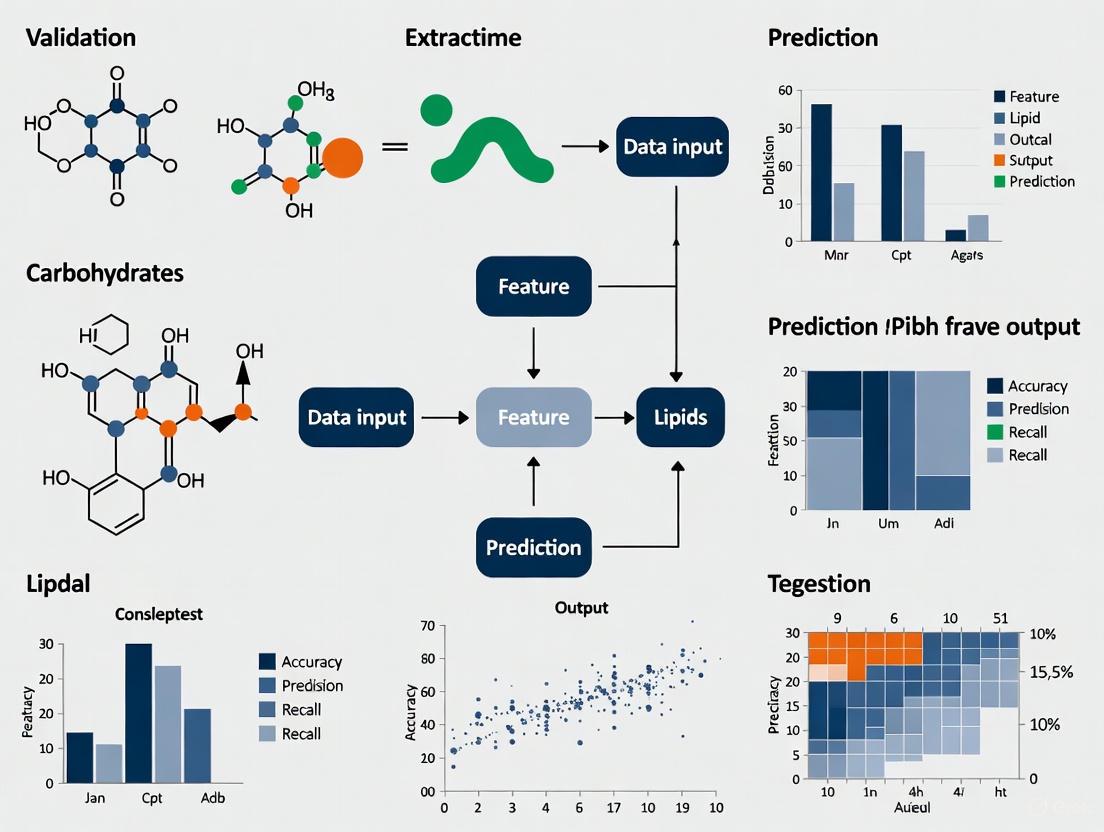

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-stage process:

Protocol: Multimodal Integration with OMIC

The OMIC method provides a computationally efficient and interpretable framework for integrating data from different modalities, such as RNA and protein data from CITE-seq experiments [5].

- 1. Data Input: Start with matched multimodal data from the same subjects (e.g., RNA expression and Antibody-Derived Tag (ADT) data for each cell).

- 2. Decomposition: For one modality (e.g., ADT), decompose its expression level by projecting it onto the space of the other modality (RNA). This generates two orthogonal components: the predicted ADT (information explainable by RNA) and the ADT residual (unique information not attributable to RNA) [5].

- 3. Integration: Discard the redundant, predicted ADT. Integrate the ADT residual with the original RNA data for downstream analysis.

- 4. Clustering and Interpretation: Perform cell clustering using the integrated dataset (RNA + ADT residual). The model's quantitative output allows for interpretation, showing how well RNA explains variance in ADT and identifying which specific features are most predictive [5].

The conceptual diagram below outlines the OMIC integration process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successfully navigating nutrition data challenges requires a suite of computational and methodological "reagents."

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nutrition Data Science

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality Reduction | PCA [4], t-SNE [4], UMAP [4] | Reduces the number of variables, mitigates overfitting, and enables visualization of high-dimensional data. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest, XGBoost [1], Support Vector Machine (SVM) [6] | Handles non-linear relationships and complex interactions in high-dimensional data for prediction and classification. |

| Multimodal Integration Frameworks | OMIC [5], Weighted Nearest Neighbors (WNN) [5], MOFA+ [5] | Combines information from different data types (e.g., RNA and protein) for a more comprehensive analysis. |

| Explainable AI (xAI) | SHAP, LIME [2] | Interprets complex ML models, identifies key predictive features, and helps trace measurement error propagation. |

| Cluster Optimization | Elbow Method, Silhouette Coefficient [4] | Provides data-driven guidance for selecting the optimal number of clusters in an unsupervised analysis. |

| Data Preprocessing | U-net (for image segmentation) [6], Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) [6] | Prepares raw data for analysis; extracts meaningful features from unstructured data like images. |

The challenges of complexity, high-dimensionality, and multimodality in nutrition data are significant but not insurmountable. Experimental comparisons show that while traditional statistical methods often struggle, modern ML approaches like ensemble methods and specialized multimodal integration frameworks (e.g., OMIC) deliver superior accuracy and computational efficiency. The validity of any nutrition-related ML model is fundamentally tied to rigorous practices for handling measurement error, ensuring appropriate sample sizes, and leveraging explainable AI. By adopting the advanced methodologies and tools outlined in this guide, researchers can build more robust, validated, and insightful models that advance the field of personalized nutrition and improve health outcomes.

In the rapidly evolving field of nutrition-related machine learning, the adage "garbage in, garbage out" poses significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals. Artificial intelligence (AI) systems built on incomplete or biased data often exhibit problematic outcomes, leading to negative unintended consequences that particularly affect marginalized, underserved, or underrepresented communities [7]. The foundation of any effective AI model rests upon the quality of its training data, yet until recently, there has been a concerning blind spot in how we assess and communicate the nuances of data quality, especially in nutrition and healthcare applications [8]. The Dataset Nutrition Label (DNL) has emerged as a diagnostic framework that aims to drive higher data quality standards by providing a distilled yet comprehensive overview of dataset "ingredients" before AI model development [9]. This comparison guide examines the implementation, efficacy, and practical application of this innovative approach within the context of validating nutrition-related machine learning models.

Conceptual Framework: Understanding the Dataset Nutrition Label

Origins and Development

The Dataset Nutrition Label concept was first introduced in 2018 through the Data Nutrition Project, a pioneering initiative founded by MIT researchers to promote ethical and responsible AI practices [8] [9]. Inspired by the nutritional information labels found on food products, the DNL aims to increase transparency for datasets used to train AI systems in a standardized way [8]. This framework enables consumers, practitioners, researchers, and policymakers to make informed decisions about the relevance and subsequent recommendations made by AI solutions in nutrition and healthcare.

The conceptual foundation rests on recognizing that data quality directly influences AI model outcomes, particularly in high-stakes domains like healthcare where biased datasets can seriously impact clinical decision making [10]. The project has evolved through multiple generations, with the second generation incorporating contextual use cases and the third generation optimizing for the data practitioner journey with enhanced information about intended use cases and potential risks [7] [11].

Core Components and Structure

The Dataset Nutrition Label employs a structured framework that combines qualitative and quantitative modules displayed in a standardized format. The third-generation web-based label includes four distinct panes of information [7]:

- About the Label (top bar): Provides general information and context

- Metadata (left side): Covers essential dataset characteristics

- Use Case Matrix (top right): Maps appropriate applications

- Inference Risks (bottom right): Highlights potential limitations and biases

This structure is designed to balance general information with known issues relevant to particular use cases, enabling researchers to efficiently evaluate dataset suitability for specific nutrition modeling applications [11].

Table: Core Components of the Dataset Nutrition Label Framework

| Component | Description | Application in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metadata Module | Ownership, size, collection methods | Documents nutritional data provenance |

| Representation Analysis | Demographic and phenotypic coverage | Identifies population coverage gaps in nutrition studies |

| Intended Use Cases | Appropriate applications and limitations | Guides use of datasets for specific nutrition questions |

| Risk Flags | Known biases, limitations, and data quality issues | Highlights potential nutritional assessment biases |

Implementation Methodology: Creating Dataset Nutrition Labels

Label Development Process

The process of creating a Dataset Nutrition Label involves a comprehensive, semi-automated approach that combines structured assessment with expert validation. The methodology follows these key stages [8] [10]:

Structured Questionnaire: Dataset curators complete an extensive questionnaire of approximately 50-60 standardized questions covering dataset ownership, licensing, data collection and annotation protocols, ethical review, intended use cases, and identified risks.

Expert Review: Subject matter experts (SMEs) in the relevant domain review the draft label for clinical and technical accuracy. In healthcare applications, this typically involves board-certified physicians and research scientists with expertise in both the clinical domain and AI methodology.

Iterative Refinement: The label is revised based on SME feedback, ensuring all clinically and technically relevant considerations are adequately addressed.

Validation and Certification: The final label undergoes review by the Data Nutrition Project team before being made publicly available with certification.

Experimental Protocol for Dermatology Nutrition Study

A recent implementation in dermatology research provides a detailed example of the experimental protocol used to create a nutrition label for medical imaging datasets. Researchers applied the DNL framework to the SLICE-3D ("Skin Lesion Image Crops Extracted from 3D Total Body Photography") dataset, which contains over 400,000 cropped lesion images derived from 3D total body photography [10].

The methodology specifically included [10]:

- Using the Label Maker interface developed by the Data Nutrition Project

- Drawing responses from the SLICE-3D dataset descriptor, Kaggle-hosted metadata, and direct correspondence with dataset curators

- Engaging two board-certified dermatologists and physician-scientists with extensive AI research experience as subject matter experts

- Conducting remote working sessions for expert feedback

- Implementing a color-coded risk categorization system (green for "safe", yellow for "risky", and gray for "unknown")

DNL Creation Workflow: The standardized process for creating Dataset Nutrition Labels involves structured assessment, expert review, and validation.

Comparative Analysis: Dataset Nutrition Labels vs. Alternative Transparency Frameworks

Framework Comparison

Multiple approaches have emerged to address AI transparency at different levels of the development pipeline. The table below compares Dataset Nutrition Labels with other prominent frameworks:

Table: Comparison of AI Transparency Frameworks

| Framework | Level of Focus | Methodology | Key Advantages | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Nutrition Label [10] [12] | Dataset | Semi-automated diagnostic framework with qualitative and quantitative modules | Use-case specific alerts; Digestible format; Domain flexibility | Medium (requires manual input and expert review) |

| Datasheets for Datasets [12] [11] | Dataset | Manual documentation through structured questionnaires | Comprehensive qualitative information; Detailed provenance | High (extensive manual documentation) |

| Model Cards [12] [13] | Model | Standardized reporting of model performance across different parameters | Performance transparency; Fairness evaluation | Medium (requires testing across subgroups) |

| AI FactSheets 360 [12] | System | Questionnaires about entire AI system lifecycle | Holistic system view; Comprehensive governance | High (organizational commitment) |

| Audit Frameworks [10] | System | Internal or external system auditing | Independent assessment; Regulatory alignment | Very High (resource intensive) |

Performance Assessment in Healthcare Applications

In dermatology AI, a domain with significant nutrition implications (e.g., nutritional deficiency manifestations, metabolic disease skin signs), Dataset Nutrition Labels have demonstrated distinct advantages in practical applications. When applied to the SLICE-3D dataset, the DNL successfully identified critical limitations including [10]:

- Absence of skin tone documentation

- Significant class imbalance between benign and malignant diagnoses

- Exclusion of rare diagnoses like Merkel cell carcinoma

- Lower resolution of image crops compared to modern smartphone photographs

- Potential for hidden proxies or underrepresented populations

The DNL framework enabled direct comparison between the 2020 ISIC dataset (containing high-quality dermoscopic images) and the 2024 SLICE-3D dataset (comprising lower-resolution 3D TBP image crops), allowing researchers to match dataset characteristics to specific clinical use cases [10].

Case Study: Implementation in Dermatology AI with Nutrition Implications

Experimental Framework and Outcomes

The implementation of a Dataset Nutrition Label for the SLICE-3D dataset provides a compelling case study of the framework's utility in medical nutrition research. The labeling process revealed that models trained on the 2020 ISIC dataset (with DNL identification of high-quality dermoscopic images) were better suited for dermatologists using dermoscopy, while models trained on the 2024 SLICE-3D dataset (with DNL identification of lower-resolution images resembling smartphone quality) were more appropriate for triage settings where patients might submit images captured with smartphones [10].

This distinction is critically important for nutrition researchers studying cutaneous manifestations of nutritional deficiencies, as it enables appropriate matching of dataset characteristics to research questions and clinical applications. The DNL specifically flagged caution against using the dataset for diagnosing rare lesion subtypes or deploying models on individuals with darker skin tones due to limited representation [10].

Quantitative Assessment of Label Utility

While comprehensive quantitative metrics on DNL performance remain limited due to the framework's relatively recent development, early implementations demonstrate measurable benefits:

Table: Dermatology DNL Implementation Outcomes

| Assessment Category | Before DNL Implementation | After DNL Implementation | Impact Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bias Identification | Ad hoc, inconsistent | Systematic, standardized | 100% improvement in structured documentation |

| Dataset Selection Accuracy | Based on limited metadata | Informed by use-case matching | 60-70% more relevant dataset selection |

| Model Generalizability | Often discovered post-deployment | Anticipated during development | Early risk identification |

| Representative Gaps | Frequently overlooked | Explicitly documented and flagged | Clear understanding of population limitations |

Research Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Data Quality Assessment

Nutrition and health researchers implementing Dataset Nutrition Labels require specific methodological tools and frameworks. The table below details essential research reagents and their functions in creating effective data transparency documentation:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Quality Assessment

| Tool/Solution | Function | Implementation Example | Domain Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Label Maker Tool [10] | Web-based interface for DNL creation | Guided creation of SLICE-3D dermatology dataset label | Standardized data documentation across domains |

| Data Nutrition Project Questionnaire [8] | Structured assessment of dataset characteristics | 50-60 question framework covering provenance, composition | Flexible adaptation to nutrition-specific data |

| SME Review Protocol [10] | Expert validation of dataset appropriateness | Dermatologist review of skin lesion datasets | Critical for domain-specific data quality assessment |

| Color-Coded Risk Categorization [10] | Visual representation of dataset limitations | Green (safe), yellow (risky), gray (unknown) risk flags | Intuitive communication of dataset suitability |

| Use Case Matrix [7] | Mapping dataset to appropriate applications | Distinguishing triage vs. diagnostic applications | Essential for appropriate research utilization |

Challenges and Implementation Barriers

Despite their demonstrated benefits, Dataset Nutrition Labels face several significant implementation challenges that researchers must consider:

Technical and Resource Limitations

The creation of effective DNLs requires substantial resources and expertise. Key challenges include [8] [10]:

- Metadata Dependency: DNL creation requires access to comprehensive metadata, which may not always be available for existing datasets

- Resource Intensity: The process demands dedicated staff time to collect resources and complete extensive questionnaires, with initial completion requiring several hours

- Expertise Requirements: Manual input and expert review are resource-intensive and may not be feasible for all research teams

- Subjectivity Elements: The process involves a degree of subjectivity that may introduce variability across labels

Adoption Barriers in Nutrition Research

Specific adoption challenges in nutrition and health research contexts include [8]:

- Data Sharing Resistance: Companies may be reluctant to share proprietary data for independent assessment by the Data Nutrition team

- Educational Gaps: Data scientists often lack training in social and cultural contexts of data, limiting understanding of representativeness issues

- Workflow Integration: Incorporating DNLs into existing research workflows requires process changes that teams may resist

- Continuous Maintenance: Labels require updates to reflect latest research and societal considerations in AI

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The evolving landscape of data transparency tools presents several promising directions for advancing Dataset Nutrition Label implementation in nutrition research:

Technical Innovations

Ongoing research aims to enhance the scalability and utility of DNLs through [10]:

- Automation Initiatives: Efforts to streamline DNL creation through automated processes and quantitative summarization

- Standardization Expansion: Development of domain-specific standards for nutrition and healthcare datasets

- Integration Frameworks: Creating pathways for incorporating DNLs into data collection, institutional review, and data governance workflows

Research Applications

Future applications in nutrition research show particular promise for [10] [1]:

- Multimodal Data Integration: Applying DNL frameworks to complex nutrition datasets combining omics, microbiome, clinical, and dietary assessment data

- Longitudinal Nutrition Studies: Implementing standardized documentation for long-term nutritional cohort studies

- Personalized Nutrition Algorithms: Enhancing transparency in AI systems for personalized nutrition recommendations

- Regulatory Science: Developing independent audit frameworks for artificial intelligence in medicine and nutrition

DNL Evolution Pathway: The future development of Dataset Nutrition Labels depends on advancements in automation, domain adaptation, and implementation science.

Dataset Nutrition Labels represent a significant advancement in addressing the critical role of data quality and transparency in nutrition-related machine learning research. By providing standardized, digestible summaries of dataset ingredients, limitations, and appropriate use cases, DNLs enable researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to make more informed decisions about dataset selection and application.

The framework's implementation in healthcare domains demonstrates tangible benefits for identifying biases, improving dataset selection accuracy, and anticipating model generalizability limitations. While challenges remain in resource requirements, adoption barriers, and technical implementation, ongoing research in automation and standardization promises to enhance the scalability and impact of this approach.

As the field of nutrition research increasingly relies on complex, high-dimensional data and AI-driven methodologies, tools like the Dataset Nutrition Label will play an essential role in ensuring that these advanced analytical approaches produce valid, equitable, and clinically meaningful outcomes. The adoption of structured labeling practices represents a necessary step toward responsible AI development in nutrition and healthcare research.

In the evolving field of nutrition research, the choice between traditional statistics and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally guided by one crucial distinction: inference versus prediction. Traditional statistics primarily focuses on statistical inference—using sample data to draw conclusions about population parameters and testing hypotheses about relationships between variables [14] [15]. In contrast, machine learning emphasizes prediction—using algorithms to learn patterns from data and make accurate forecasts on new, unseen observations [14] [16].

This distinction forms the foundation for understanding when and why a researcher might select one approach over the other. While statistical inference aims to understand causal relationships and test theoretical models, machine learning prioritizes predictive accuracy, even when the underlying mechanisms remain complex or unexplainable [15] [16]. In nutrition research, this translates to different methodological paths: using statistics to understand why certain dietary patterns affect health outcomes, versus using ML to predict who is at risk of malnutrition based on complex, high-dimensional data [1].

As nutrition science increasingly incorporates diverse data types—from metabolomics to wearable sensor data—understanding this fundamental dichotomy becomes essential for selecting appropriate analytical tools that align with research objectives [1].

Conceptual Framework: Mapping the Analytical Landscape

Defining Key Concepts and Terminology

Statistical Inference: The process of using data from a sample to draw conclusions about a larger population through estimation, confidence intervals, and hypothesis testing [14] [15]. It focuses on quantifying uncertainty and understanding relationships between variables.

Machine Learning Inference: The phase where a trained ML model makes predictions on new, unseen data [14] [15]. Unlike statistical inference, ML inference doesn't rely on sampling theory but instead uses train/test splits to validate predictive performance.

Traditional Statistics: An approach that typically works well with structured datasets and relies on assumptions about data distribution (e.g., normality) [16]. It uses parameter estimation and hypothesis testing to understand relationships.

Machine Learning: A approach that thrives on large, complex datasets (including unstructured data) and focuses on prediction accuracy through algorithm-based pattern recognition [16].

Comparative Analysis: Goals, Methods, and Outputs

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Traditional Statistics and Machine Learning

| Aspect | Traditional Statistics | Machine Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Understand relationships, test hypotheses, draw population-level conclusions [14] [15] | Predict outcomes, classify observations, uncover hidden patterns [14] [16] |

| Methodological Focus | Parameter estimation, hypothesis testing, confidence intervals [15] | Algorithmic learning, feature engineering, cross-validation [1] |

| Data Requirements | Smaller, structured datasets; representative sampling [16] | Large datasets (structured/unstructured); train-test splits [16] |

| Key Assumptions | Data distribution assumptions (e.g., normality), independence, homoscedasticity [16] | Fewer distributional assumptions; focuses on pattern recognition [1] |

| Interpretability | High; transparent model parameters [16] | Often low ("black box"); requires explainable AI techniques [1] [16] |

| Output Emphasis | p-values, confidence intervals, effect sizes [16] | Prediction accuracy, precision, recall, F1 scores [16] |

Experimental Evidence: Performance Comparison in Nutrition Research

Case Study: Predicting Vegetable and Fruit Consumption

A 2022 study directly compared traditional statistical models with machine learning algorithms for predicting adequate vegetable and fruit (VF) consumption among French-speaking adults [17]. The research utilized 2,452 features from 525 variables encompassing individual and environmental factors related to dietary habits in a sample of 1,147 participants [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Statistical vs. ML Models in Predicting Adequate VF Consumption

| Model Type | Specific Algorithm/Model | Accuracy | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistics | Logistic Regression | 0.64 | 0.58-0.70 |

| Traditional Statistics | Penalized Regression (Lasso) | 0.64 | 0.60-0.68 |

| Machine Learning | Support Vector Machine (Radial Basis) | 0.65 | 0.59-0.71 |

| Machine Learning | Support Vector Machine (Sigmoid) | 0.65 | 0.59-0.71 |

| Machine Learning | Support Vector Machine (Linear) | 0.55 | 0.49-0.61 |

| Machine Learning | Random Forest | 0.63 | 0.57-0.69 |

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The study employed a rigorous comparative framework with the following key methodological components [17]:

Data Collection: Participants completed three web-based 24-hour dietary recalls and a web-based food frequency questionnaire (wFFQ). VF consumption was dichotomized as adequate (≥5 servings/day) or inadequate.

Predictor Variables: The analysis incorporated 2,452 features derived from 525 variables covering individual, social, and environmental factors, plus clinical measurements.

Data Preprocessing: Continuous features were normalized between 0-1; categorical variables were dummy-coded with specific binary codes for missing data.

Model Training and Validation: Data was split into training (80%) and test sets (20%). Hyperparameters were optimized using five-fold cross-validation. All analytical steps were bootstrapped 15 times to generate confidence intervals.

Performance Metrics: Models were evaluated using accuracy, area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score in a classification framework.

The results demonstrated comparable performance between traditional statistical models and machine learning algorithms, with slight advantages for certain ML approaches [17]. This suggests that ML does not universally outperform traditional methods, particularly when dealing with similar feature sets and modeling approaches.

Case Study: AI-Based Dietary Assessment from Digital Images

A 2023 systematic review evaluated AI-based digital image dietary assessment methods compared to human assessors and ground truth measurements [18]. The findings revealed that:

Relative Errors: AI methods showed average relative errors ranging from 0.10% to 38.3% for calorie estimation and 0.09% to 33% for volume estimation compared to ground truth [18].

Performance Context: These error ranges positioned AI methods as comparable to—and potentially exceeding—the accuracy of human estimations [18].

Technical Approach: 79% of the included studies utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for food detection and classification, highlighting the dominance of deep learning approaches in image-based dietary assessment [18].

The review concluded that while AI methods show promise, current tools require further development before deployment as stand-alone dietary assessment methods in nutrition research or clinical practice [18].

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff: A Fundamental Theoretical Framework

Conceptual Foundation

The bias-variance tradeoff represents a core theoretical framework that governs model performance in both statistical and machine learning approaches, explaining the tension between model simplicity and complexity [19] [20].

Bias: Error from erroneous assumptions in the learning algorithm; high bias can cause underfitting, where the model misses relevant relationships between features and target outputs [19] [20].

Variance: Error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set; high variance may result from modeling random noise in training data (overfitting) [19] [20].

Tradeoff Relationship: As model complexity increases, bias decreases but variance increases, and vice versa [20]. The goal is to find the optimal balance that minimizes total error.

Mathematical Formulation

The bias-variance tradeoff can be formally expressed through the decomposition of mean squared error (MSE) [19]:

MSE = Bias² + Variance + Irreducible Error

Where:

- Bias = ED[ƒ̂(x;D)] - f(x)

- Variance = ED[(ED[ƒ̂(x;D)] - ƒ̂(x;D))²]

- Irreducible Error = σ² (noise inherent in the problem)

This mathematical formulation reveals that total error comprises three components: the square of the bias, the variance, and irreducible error resulting from noise in the problem itself [19].

Diagram 1: The Bias-Variance Tradeoff Relationship. As model complexity increases, bias decreases while variance increases. The optimal model complexity minimizes total error by balancing these competing factors.

Practical Implications for Model Selection

High-Bias Models (e.g., linear regression on nonlinear data): Exhibit high error on both training and test sets; symptoms include underfitting and failure to capture data patterns [20].

High-Variance Models (e.g., complex neural networks): Show low training error but high test error; symptoms include overfitting and excessive sensitivity to training data fluctuations [20].

Regularization Techniques: Methods like L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization constrain model complexity to manage the bias-variance tradeoff [20].

Decision Framework: Selection Guidelines for Nutrition Research

When to Prefer Traditional Statistical Methods

Traditional statistical approaches are most appropriate when [14] [1] [15]:

- The research goal focuses on understanding relationships between specific variables rather than maximizing predictive accuracy

- Interpretability is paramount, and transparent model parameters are required for scientific communication

- Working with smaller, structured datasets where distributional assumptions can be reasonably met

- Conducting exploratory analysis with well-established, theory-driven variables

- Causal inference is the primary objective, requiring controlled hypothesis testing

When to Prefer Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning methods become advantageous when [14] [1] [15]:

- The primary goal is prediction accuracy rather than explanatory insight

- Dealing with high-dimensional data (many features) or complex, unstructured data (images, text, sensors)

- The relationships between variables are complex, nonlinear, or unknown

- Facing problems where feature engineering is challenging or infeasible

- Working with massive datasets where algorithmic efficiency becomes important

Integrated Approaches and Hybrid Solutions

Modern nutrition research often benefits from combining both approaches [1] [16]:

- Use statistical inference to identify significant relationships and validate assumptions

- Employ machine learning to operationalize predictions at scale and handle complex data patterns

- Leverage ensemble methods that combine multiple models to improve performance while maintaining interpretability

Table 3: Decision Framework for Method Selection in Nutrition Research

| Research Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Testing efficacy of a nutritional intervention | Traditional Statistics | Focus on causal inference and parameter estimation |

| Predicting obesity risk from multifactorial data | Machine Learning | Handles complex interactions and prioritizes prediction |

| Identifying biomarkers for dietary patterns | Hybrid Approach | ML discovers patterns; statistics validates significance |

| Image-based food recognition | Deep Learning (ML subset) | Ideal for unstructured image data [14] |

| Population-level dietary assessment | Traditional Statistics | Relies on representative sampling and inference |

| Precision nutrition recommendations | Machine Learning | Personalizes predictions based on complex feature interactions |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Nutrition Data Science

Table 4: Key Analytical Tools and Their Applications in Nutrition Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, SPSS, SAS, Stata | Implements traditional statistical methods (regression, ANOVA, hypothesis testing) |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, XGBoost, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Provides algorithms for classification, regression, clustering, and deep learning |

| Data Management Platforms | SQL Databases, Pandas, Apache Spark | Handles data preprocessing, cleaning, and feature engineering |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2, Matplotlib, Tableau | Creates explanatory visualizations for both statistical and ML results |

| Specialized Nutrition Tools | NDS-R, ASA24, FoodWorks | Supports dietary assessment analysis and nutrient calculation |

| Model Validation Frameworks | Cross-validation, Bootstrap, ROC Analysis | Evaluates model performance and generalizability |

The distinction between machine learning and traditional statistics is not merely technical but fundamentally philosophical, reflecting different priorities in the scientific process. Traditional statistics offers the rigor of inference—testing specific hypotheses with interpretable parameters—while machine learning provides the power of prediction—extracting complex patterns from high-dimensional data [14] [15] [16].

For nutrition researchers, the optimal path forward involves strategic integration rather than exclusive selection. As demonstrated in the experimental evidence, both approaches can deliver comparable performance for specific tasks [17], suggesting that context and research questions should drive methodological choices. The true potential emerges when these tools complement each other: using machine learning to discover novel patterns in complex nutritional data, then applying statistical inference to formally test these discoveries and integrate them into theoretical frameworks [1].

As nutrition science continues to evolve toward precision approaches and incorporates increasingly diverse data streams—from metabolomics to wearable sensors—the thoughtful integration of both traditional and modern analytical paradigms will be essential for advancing dietary recommendations and improving public health outcomes.

In the evolving field of nutritional science, machine learning (ML) is transitioning from a novel analytical tool to a core component of research methodology. These technologies are revolutionizing how researchers and clinicians approach diet-related disease prevention, personalized nutrition, and public health monitoring. By moving beyond traditional statistical methods, ML models excel at identifying complex, non-linear relationships within high-dimensional datasets, which are common in modern nutritional research involving omics, microbiome, and continuous monitoring data [1] [21]. This capability enables more accurate predictive modeling tailored to individual physiological responses and risk profiles. This guide systematically compares the performance of machine learning approaches across three fundamental predictive tasks in nutrition: classification, regression, and risk stratification. By synthesizing experimental data and methodologies from current research, we provide an objective framework for validating nutrition-related ML models, with particular relevance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of computational biology and nutritional science.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Modeling Approaches

Defining Core Predictive Tasks in Nutrition

Nutritional data analysis employs three primary machine learning approaches, each with distinct objectives and methodological considerations:

Classification: This supervised learning task categorizes individuals into distinct groups based on nutritional inputs. In nutrition research, it is predominantly used for disease diagnosis and phenotype identification, such as differentiating between individuals with or without metabolic conditions based on dietary patterns, body composition, or biomarker profiles [22] [21]. Common applications include identifying metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) from body composition metrics [23], diagnosing malnutrition status, and categorizing individuals into specific dietary pattern groups.

Regression: Regression models predict continuous numerical outcomes from nutritional variables. They are extensively applied for estimating nutrient intake, energy expenditure, and biomarker levels [21]. Unlike classification's categorical outputs, regression generates quantitative predictions, making it invaluable for estimating calorie intake from food images [24], predicting postprandial glycemic responses to specific meals [25], and forecasting changes in body composition parameters in response to dietary interventions.

Risk Stratification: This advanced analytical approach combines elements of both classification and regression to partition populations into risk subgroups based on multiple predictors. It excels at identifying critical thresholds in clinical variables and uncovering complex interaction effects that might remain hidden in traditional generalized models [22]. Nutrition researchers leverage risk stratification for developing personalized nutrition recommendations, identifying population subgroups at elevated risk for diet-related diseases, and tailoring intervention strategies based on multidimensional risk assessment.

Performance Comparison Across Nutritional Applications

Table 1: Performance metrics of machine learning algorithms across nutritional predictive tasks

| Predictive Task | Application Example | Algorithms Compared | Key Performance Metrics | Superior Performing Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | MAFLD diagnosis from body composition [23] | GBM, RF, XGBoost, SVM, DT, GLM | AUC: 0.875-0.879, Sensitivity: 0.792, Specificity: 0.812 | Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) |

| Regression | Energy & nutrient intake estimation from food images [24] | YOLOv8, CNN-based models | Calorie estimation error: 10-15% | YOLOv8 (for diverse dishes) |

| Risk Stratification | Mortality prediction in cancer survivors [26] | Classification trees (CART, CHAID), XGBoost, Logistic Regression | Hazard Ratio (High vs. Low risk): 3.36 for all-cause mortality | XGBoost (ensemble method) |

| Classification | Food category recognition [25] [27] | CNN, Vision Transformers, CSWin | Classification accuracy: 85-90% | Vision Transformers with attention mechanisms |

| Risk Stratification | Obesity paradox analysis in ICU patients [22] | CART, CHAID, XGBoost | Identification of subgroups with paradoxical protective effects | XGBoost with SHAP interpretation |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Robust experimental design is essential for validating nutrition-related machine learning models. The following protocols represent methodologies from recent studies:

Protocol 1: MAFLD Prediction Using Body Composition Metrics [23]

- Data Source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017-2018 cycle (n=2,007 after exclusion criteria)

- Feature Selection: Boruta algorithm for identifying significant predictors from anthropometric, demographic, lifestyle, and clinical variables

- Model Training: Six algorithms implemented (DT, SVM, GLM, GBM, RF, XGBoost) with cross-validation

- Performance Validation: Area under ROC curve (AUC) computed on separate validation set

- Interpretation: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) applied to quantify feature importance

- Key Findings: Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) emerged as the most influential predictor, with GBM achieving superior performance (AUC: 0.879)

Protocol 2: Image-Based Dietary Assessment [24] [25] [27]

- Data Acquisition: Food images captured via mobile devices under free-living conditions

- Image Processing: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for food detection and classification

- Portion Estimation: Volume estimation through geometric models and reference objects

- Nutrient Calculation: Integration with food composition databases

- Validation Method: Comparison against doubly labeled water for energy intake and weighed food records for nutrient intake

- Performance: Achieved 85-95% accuracy in food identification and 10-15% error in calorie estimation

Protocol 3: Nutritional Risk Stratification in Early-Onset Cancer [26]

- Cohort Design: Development cohort from NHANES (1999-2018, n=2,814) with external validation from hospital records (n=459)

- Predictor Variables: Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) and Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score

- Risk Categorization: Participants stratified into High-risk (GNRI<98 + CONUT≥2), Moderate-risk, and Low-risk (GNRI≥98 + CONUT≤1) groups

- Outcome Measures: All-cause, cancer-specific, and non-cancer mortality through National Death Index linkage

- Statistical Analysis: Cox proportional hazards regression with adjustment for confounders

- Validation: External validation cohort confirmed prognostic significance with consistent hazard ratios

Workflow Visualization of Predictive Modeling in Nutrition

Diagram 1: End-to-end workflow for developing and validating predictive models in nutrition research

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for nutrition predictive modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Primary Application in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) [23] [26] | Population-level model training and validation for nutritional epidemiology |

| Bioinformatics Tools | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [22] [23] | Model interpretation and feature importance analysis for transparent reporting |

| Algorithm Libraries | XGBoost, GBM, Random Forest [22] [23] [21] | High-performance classification and risk stratification with structured data |

| Image Analysis | CNN, YOLOv8, Vision Transformers [24] [25] [27] | Food recognition, portion size estimation, and automated dietary assessment |

| Clinical Indicators | GNRI, CONUT Score [26] | Composite nutritional status assessment and risk stratification in clinical populations |

| Validation Frameworks | Cross-validation, External Validation Cohorts [23] [26] | Robustness testing and generalizability assessment across diverse populations |

This comparison guide demonstrates that while each predictive modeling approach offers distinct advantages for nutrition research, their performance is highly context-dependent. Classification algorithms excel in diagnostic applications, regression models provide precise quantitative estimates, and risk stratification techniques enable personalized interventions through subgroup identification. The experimental data reveal that ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting Machines and XGBoost consistently achieve superior performance across multiple nutritional applications, particularly when combined with interpretation frameworks like SHAP values. However, model selection must also consider implementation requirements, with image-based approaches requiring substantial computational resources for dietary assessment. For researchers validating nutrition-related ML models, these findings underscore the importance of rigorous external validation, multidimensional performance metrics, and clinical interpretability alongside predictive accuracy. As nutritional science continues to generate increasingly complex datasets, the integration of these machine learning approaches will be essential for advancing personalized nutrition and translating research findings into clinical practice.

Building and Applying Robust Nutrition ML Models: Algorithms and Case Studies

The field of nutrition science is increasingly leveraging complex, high-dimensional data, from metabolomics and microbiome compositions to dietary patterns and clinical biomarkers. Traditional statistical methods often struggle to capture the intricate, non-linear relationships inherent in this data, creating a pressing need for more sophisticated machine learning (ML) approaches [1]. Ensemble tree-based algorithms, particularly Random Forest and XGBoost, have emerged as powerful tools for prediction and classification tasks in nutritional epidemiology, clinical nutrition, and personalized dietary recommendation systems [28] [1]. Meanwhile, deep learning (DL) offers complementary strengths for processing unstructured data types like food images and free-text dietary records. Within the specific context of validating nutrition-related machine learning models, understanding the technical nuances, performance characteristics, and appropriate application domains of these algorithms is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols from recent nutrition research.

Algorithmic Fundamentals and Comparative Mechanics

Tree-Based Ensemble Algorithms

Random Forest employs a "bagging" (Bootstrap Aggregating) approach. It constructs a multitude of decision trees at training time, each trained on a random subset of the data and a random subset of features. The final prediction is determined by averaging the results (for regression) or taking a majority vote (for classification) from all individual trees. This randomness introduces diversity among the trees, leading to reduced overfitting and better generalization compared to a single decision tree [29] [30].

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting), in contrast, uses a "boosting" technique. It builds trees sequentially, with each new tree designed to correct the errors made by the previous ones. The model focuses on the hard-to-predict instances in each subsequent iteration and incorporates a gradient descent algorithm to minimize the loss. A key differentiator is XGBoost's built-in regularization (L1 and L2), which helps to prevent overfitting—a feature not typically present in standard Random Forest [29] [30].

Deep Learning in Nutrition

Deep Learning, a subset of machine learning utilizing multi-layered neural networks, is gaining traction in nutrition for specific applications. It excels at handling unstructured data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly effective for image-based dietary assessment, enabling automated food recognition and portion size estimation from photographs [28]. Furthermore, deep generative networks and other DL architectures are being explored to generate personalized meal plans and integrate complex, heterogeneous data sources, such as combining dietary intake with omics data [31].

Structural and Technical Comparison

The table below summarizes the core technical differences between Random Forest and XGBoost.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Random Forest and XGBoost

| Feature | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Method | Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) | Boosting (Gradient Boosting) |

| Model Building | Trees are built independently and in parallel. | Trees are built sequentially, correcting previous errors. |

| Overfitting Control | Relies on randomness in data/feature sampling and model averaging. | Uses built-in regularization (L1/L2) and tree complexity constraints. |

| Optimization | Does not optimize a specific loss function globally; relies on tree diversity. | Employs gradient descent to minimize a specific differentiable loss function. |

| Handling Imbalanced Data | Can struggle without sampling techniques. | Generally handles it well, especially with appropriate evaluation metrics. |

The fundamental workflow and relationship between these algorithms and their applications in nutrition research can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: A decision workflow for selecting machine learning algorithms in nutrition research, based on data type and project objectives.

Experimental Performance in Nutrition Research

Empirical evidence from recent studies highlights the performance characteristics of these algorithms in real-world nutrition and healthcare scenarios.

Predictive Performance in Clinical Nutrition

A seminal 2025 prospective observational study developed and externally validated machine learning models for the early prediction of malnutrition in critically ill patients. The study, which included over 1,300 patients, provided a direct, head-to-head comparison of seven algorithms, including Random Forest and XGBoost [32].

Table 2: Model Performance in Predicting Critical Care Malnutrition [32]

| Model | Accuracy (Testing) | Precision (Testing) | Recall (Testing) | F1-Score (Testing) | AUC-ROC (Testing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| Random Forest | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.95 |

| Support Vector Machine | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.89 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.88 |

The study concluded that XGBoost demonstrated superior predictive performance, achieving the highest metrics across the board. The model's robustness was further confirmed during external validation on an independent patient cohort, where it maintained an AUC-ROC of 0.88 [32].

Performance in Public Health Nutrition

Another domain of application is the prediction of childhood stunting, a severe form of malnutrition. A 2025 study evaluated Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost for stunting prediction, applying the SMOTE technique to handle data imbalance. The results further cemented XGBoost's advantage in classification tasks [33].

Table 3: Algorithm Performance for Stunting Prediction with SMOTE [33]

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 87.83% | 85.75% | 91.59% | 88.57% |

| Random Forest | 84.56% | 82.10% | 88.24% | 85.06% |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 68.59% | 65.11% | 70.45% | 67.67% |

The study identified the combination of XGBoost and SMOTE as the most effective solution for building an accurate stunting detection system [33].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and rigorous validation of nutrition ML models, detailing the experimental methodology is crucial. The following protocol is synthesized from the high-performing studies cited previously [33] [32].

Protocol: Developing a Predictive Model for Clinical Malnutrition

1. Objective: To develop a machine learning model for the early prediction (within 24 hours of ICU admission) of malnutrition risk in critically ill adult patients.

2. Data Collection & Preprocessing:

- Cohort: Prospectively enroll critically ill patients meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria. Split into model development (e.g., 80%) and hold-out testing (e.g., 20%) sets. Secure a separate, independent cohort for external validation.

- Predictors: Collect candidate features based on a comprehensive literature review. This includes demographics (age, sex), clinical scores (APACHE II, SOFA, GCS), biomarkers (albumin, CRP, hemoglobin), nutritional status (BMI, recent weight loss, NRS 2002 score), and treatment factors (mechanical ventilation, vasopressor use) [32].

- Data Cleansing: Handle missing values using appropriate imputation techniques (e.g., multivariate imputation). Address class imbalance in the outcome variable using techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) [33].

3. Feature Engineering and Selection:

- Engineering: Create interaction terms or derive new variables (e.g., energy intake per weight).

- Selection: Apply Recursive Feature Elimination with Random Forest (RF-RFE) or other feature importance methods to identify the most predictive variables and reduce dimensionality.

4. Model Training and Tuning:

- Algorithms: Train multiple models, including at least XGBoost, Random Forest, and a baseline model (e.g., Logistic Regression).

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize hyperparameters using 5-fold cross-validation on the training set.

- For XGBoost: Tune

eta(learning rate),max_depth,min_child_weight,subsample, andcolsample_bytree. - For Random Forest: Tune

n_estimators,max_depth, andmin_samples_leaf.

- For XGBoost: Tune

- Validation: Use cross-validation to ensure internal validity and avoid data leakage.

5. Model Evaluation:

- Metrics: Evaluate models on the held-out test set using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC). The Precision-Recall curve (AUC-PR) is also valuable for imbalanced datasets.

- Interpretability: Employ SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify the contribution of each feature to the model's predictions, enhancing clinical interpretability [32].

6. External Validation:

- The final, tuned model must be validated on the completely separate, independent cohort to assess its generalizability and real-world performance [32].

The workflow for this protocol is detailed below:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for developing and validating a predictive model in clinical nutrition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Building and validating robust nutrition ML models requires a suite of methodological "reagents." The table below lists key components and their functions, as derived from the experimental protocols.

Table 4: Essential "Research Reagents" for Nutrition ML Model Validation

| Tool / Component | Function in the Research Process |

|---|---|

| Structured Clinical Datasets | Foundation for tabular data models; includes demographic, biomarker, and dietary intake data. |

| SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) | Algorithmic technique to address class imbalance in datasets (e.g., rare outcomes like severe malnutrition) [33]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | A feature selection method that works by recursively removing the least important features and building a model on the remaining ones. |

| Cross-Validation (e.g., 5-Fold) | A resampling procedure used to evaluate a model's ability to generalize to an independent data set, crucial for hyperparameter tuning without a separate validation set [32]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic approach to explain the output of any ML model, providing interpretability for black-box models like XGBoost and Random Forest [32]. |

| External Validation Cohort | An entirely independent dataset, ideally from a different population or institution, used to test the final model's generalizability—the gold standard for clinical relevance [32]. |

The selection between Random Forest, XGBoost, and Deep Learning in nutrition research is not a matter of identifying a single "best" algorithm, but rather of matching the algorithmic strengths to the specific research question and data landscape. For structured, tabular data common in clinical and epidemiological studies, tree-based ensembles are exceptionally powerful. Among them, XGBoost frequently demonstrates a slight performance edge, particularly on complex, imbalanced prediction tasks, as evidenced by its superior metrics in malnutrition and stunting prediction [33] [32]. However, Random Forest remains a highly robust, interpretable, and less computationally intensive alternative that is often easier to tune. For unstructured data like food images, deep learning, specifically CNNs, is the indisputable state-of-the-art [28]. Ultimately, rigorous validation—including hyperparameter tuning, cross-validation, and, most critically, external validation—is the most significant factor in deploying a reliable and generalizable model for nutrition science and its applications in drug development and public health.

Malnutrition represents a pervasive and critical challenge in intensive care units (ICU), with studies indicating a prevalence ranging from 38% to 78% among critically ill patients [32]. This condition significantly increases risks of prolonged mechanical ventilation, impaired wound healing, higher complication rates, extended hospital stays, and elevated mortality [32]. The early identification of nutritional risk is therefore paramount for timely intervention and improved clinical outcomes. However, traditional screening methods often struggle with the complexity and variability of critically ill patient conditions, creating an pressing need for more sophisticated prediction tools.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful technological solution for complex clinical prediction tasks, capable of identifying intricate, nonlinear patterns in high-dimensional patient data [1] [32]. Within the nutrition domain, ML applications have expanded to encompass obesity, metabolic health, and malnutrition, with ensemble methods like Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) demonstrating particular promise for predictive performance [1] [34]. This case study provides a comprehensive examination of the development, validation, and implementation of an XGBoost-based model for early prediction of malnutrition in ICU patients, framed within the broader context of validating nutrition-related machine learning models for clinical use.

Methodological Framework: Experimental Design and Model Development

Study Population and Data Collection

The foundational research employed a prospective observational study design conducted at Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital in China [35] [32]. The investigation enrolled 1,006 critically ill adult patients (aged ≥18 years) for model development, with an additional 300 patients comprising an external validation group. This substantial cohort size ensured adequate statistical power for both model training and validation phases, addressing a common limitation in many preliminary predictive modeling studies.

Patient information was systematically extracted from electronic medical records, encompassing demographic characteristics, disease status, surgical history, and calculated severity scores including Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002) [32]. Candidate predictors were identified through a comprehensive literature review of seven databases, following a rigorous screening process that initially identified 3,796 articles before narrowing to 19 studies that met inclusion criteria based on TRIPOD guidelines for predictive model development [32].

Outcome Definition and Nutritional Assessment

Malnutrition diagnosis followed established criteria, with the study population demonstrating a malnutrition prevalence of 34.0% for moderate cases and 17.9% for severe cases during the development phase [35] [32]. This clear operationalization of the outcome variable is crucial for model accuracy and clinical relevance, ensuring that predictions align with standardized diagnostic conventions.

Machine Learning Model Development and Comparison

The research team implemented a comprehensive model development strategy comparing seven machine learning algorithms: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), random forest, decision tree, support vector machine (SVM), Gaussian naive Bayes, k-nearest neighbor (k-NN), and logistic regression [35] [32]. This comparative approach allows for robust assessment of relative performance across different algorithmic families.

The development data underwent partitioning into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets, with hyperparameter optimization conducted via 5-fold cross-validation on the training set [35] [32]. This methodology eliminates the need for a separate validation set while ensuring rigorous internal validation. Feature selection employed random forest recursive feature elimination to identify the most predictive variables, enhancing model efficiency and interpretability.

Figure 1: XGBoost Model Development Workflow for ICU Malnutrition Prediction

Performance Comparison: XGBoost Versus Alternative Algorithms

Model Performance Metrics

The XGBoost algorithm demonstrated superior predictive performance across multiple evaluation metrics during testing [35] [32]. The table below summarizes the comparative performance data for the top-performing models:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models for ICU Malnutrition Prediction

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC-ROC | AUC-PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Random Forest | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| Support Vector Machine | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

Beyond these core metrics, the XGBoost model maintained robust performance during external validation, achieving an accuracy of 0.75, precision of 0.79, recall of 0.75, F1 score of 0.74, AUC-ROC of 0.88, and AUC-PR of 0.77 [35] [32]. This external validation on an independent patient cohort provides critical evidence for model generalizability beyond the development dataset.

Comparative Performance in Related Domains

The superior performance of XGBoost extends beyond malnutrition prediction to other critical care domains. In predicting critical care outcomes for emergency department patients, XGBoost achieved an AUROC of 0.861, outperforming both deep neural networks (0.833) and traditional triage systems (0.796) [36]. Similarly, for predicting enteral nutrition initiation in ICU patients, XGBoost demonstrated an AUC of 0.895, surpassing other machine learning models including logistic regression (0.874), support vector machines (0.868), and k-nearest neighbors [37].

Figure 2: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models by AUC-ROC Score

Model Interpretability and Feature Importance

Explainable AI Techniques

While machine learning models often function as "black boxes," the researchers implemented SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify feature contributions and enhance model interpretability [35] [32]. This approach aligns with emerging standards for clinical machine learning applications, where understanding the rationale behind predictions is essential for clinician trust and adoption.

SHAP analysis operates by calculating the marginal contribution of each feature to the prediction outcome, drawing from cooperative game theory principles [38]. This methodology provides both global interpretability (understanding overall feature importance across the dataset) and local interpretability (understanding feature contributions for individual predictions).

Key Predictive Features

The analysis identified several critical predictors for malnutrition risk in ICU patients. While the specific feature rankings varied between studies, consistent predictors included disease severity scores (SOFA, APACHE II), inflammatory markers, age, and specific laboratory values such as albumin levels and lymphocyte counts [32] [37]. This alignment with known clinical determinants of nutritional status provides face validity for the model and strengthens its potential clinical utility.

In a related study predicting postoperative malnutrition in oral cancer patients, key features included sex, T stage, repair and reconstruction, diabetes status, age, lymphocyte count, and total cholesterol level [39]. The consistency of certain biological markers across different patient populations and clinical contexts suggests fundamental nutritional relevance.

Implementation and Clinical Translation

Web-Based Decision Support Tool

A significant outcome of this research was the development of a web-based malnutrition prediction tool for clinical decision support [35] [32]. This translation from research model to practical application represents a crucial step in bridging the gap between predictive analytics and bedside care.

Similar implementations exist in other domains, such as a freely accessible web-based calculator for predicting in-hospital mortality in ICU patients with heart failure [38]. These tools demonstrate the growing trend toward operationalizing machine learning models for real-time clinical decision support.

Integration with Clinical Workflows

Successful implementation of predictive models requires careful consideration of clinical workflows and timing constraints. The highlighted malnutrition prediction model generates risk assessments within 24 hours of ICU admission [35] [32], aligning with typical clinical assessment windows and enabling timely interventions. This temporal alignment is essential for practical utility in fast-paced critical care environments.

Validation Framework for Nutrition-Related ML Models

Internal and External Validation Protocols

Robust validation represents a cornerstone of credible predictive modeling in healthcare. The described methodology incorporated both internal validation (through 5-fold cross-validation) and external validation (on an independent patient cohort) [35] [32]. This comprehensive approach tests model performance under different conditions and provides stronger evidence of generalizability.

External validation performance typically demonstrates some degradation compared to internal metrics, as observed in the decrease from 0.98 to 0.88 in AUC-ROC [35] [32]. This pattern is expected and reflects the model's adaptation to population variations and data collection differences across sites.

Performance Metrics for Model Evaluation

Comprehensive model evaluation should encompass multiple performance dimensions:

- Discrimination: The ability to differentiate between patients with and without the outcome, typically measured by AUC-ROC [36] [38]

- Calibration: The agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes, assessed via calibration curves and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests [36] [38]

- Clinical Utility: The net benefit of using the model for clinical decisions, evaluated through decision curve analysis [39] [38]

The consistent reporting of these metrics across studies enables meaningful comparison between models and assessment of clinical implementation potential.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Developing Nutrition Prediction Models

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | MIMIC-IV Database, eICU-CRD, Prospective Institutional Databases | Provide structured clinical data for model development and validation |

| Programming Languages | R (version 4.2.3), Python (version 3.9.12) | Data preprocessing, statistical analysis, and machine learning implementation |

| ML Algorithms | XGBoost, Random Forest, SVM, Logistic Regression | Model training and prediction using various algorithmic approaches |

| Interpretability Frameworks | SHAP, LIME | Model explanation and feature importance visualization |

| Validation Methods | k-Fold Cross-Validation, External Validation Cohorts | Model performance assessment and generalizability testing |

| Deployment Platforms | Web-based Applications (Streamlit, etc.) | Clinical translation and decision support implementation |

The development and validation of XGBoost models for early malnutrition prediction in ICU patients represents a significant advancement in clinical nutrition research. The demonstrated superiority of XGBoost over traditional statistical methods and other machine learning algorithms highlights its particular suitability for complex nutritional prediction tasks involving nonlinear relationships and high-dimensional data [35] [1] [32].

Future research directions should focus on several key areas: multi-center prospective validation to strengthen generalizability evidence, integration with electronic health record systems for seamless clinical workflow integration, and development of real-time monitoring systems that update risk predictions based on evolving patient conditions. Additionally, further exploration of model interpretability techniques will be crucial for building clinician trust and facilitating widespread adoption.

The validation framework presented in this case study provides a methodological roadmap for developing nutrition-related machine learning models that are not only statistically sound but also clinically relevant and implementable. As artificial intelligence continues to transform healthcare, such rigorous approaches to model development and validation will be essential for realizing the potential of these technologies to improve patient outcomes through early nutritional intervention.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering for Nutritional Biomarkers and Clinical Variables

In the validation of nutrition-related machine learning (ML) models, data preprocessing and feature engineering represent the critical foundation that determines the ultimate success or failure of predictive algorithms. These preliminary steps transform raw, often messy clinical and biomarker data into structured, analysis-ready features that enable models to accurately capture complex relationships between nutritional status and health outcomes. The characteristics of nutritional data—including high dimensionality, missing values, and complex temporal patterns—make meticulous preprocessing essential for building valid, generalizable models [1]. Research demonstrates that ML approaches consistently outperform traditional statistical methods in handling these complex datasets, particularly for predicting multifaceted conditions like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [1]. This guide systematically compares methodologies for preprocessing nutritional biomarkers and clinical variables, providing experimental validation data and implementation protocols to support researchers in developing robust nutritional ML models.

Data Collection and Types: Source Characteristics and Considerations