A Priori vs A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the two principal methodologies in dietary pattern analysis for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Priori vs A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the two principal methodologies in dietary pattern analysis for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational concepts of a priori (hypothesis-driven) and a posteriori (exploratory, data-driven) approaches, detailing their statistical methods, applications, and limitations. The content explores how these patterns are validated against health outcomes like Parkinson's disease, gastric cancer, and hypertension, and offers guidance for method selection and troubleshooting common analytical challenges. By synthesizing current evidence, this guide aims to inform robust study design in nutritional epidemiology and the development of targeted dietary interventions.

Understanding the Core Concepts: A Priori and A Posteriori Dietary Patterns

In scientific research, particularly within nutritional epidemiology and systems biology, two fundamental paradigms guide inquiry: hypothesis-driven and data-driven approaches. These methodologies represent distinct philosophical frameworks for generating knowledge. The hypothesis-driven approach, aligned with a priori reasoning, begins with a specific, pre-defined prediction derived from existing theory. In contrast, the data-driven approach, operating through a posteriori analysis, seeks to identify patterns and generate hypotheses directly from comprehensive datasets without initial presuppositions about outcomes [1]. This dichotomy frames a critical methodological tension in contemporary science, especially evident in studies investigating complex relationships between dietary patterns and health outcomes.

The distinction between these paradigms extends beyond mere procedural differences to encompass fundamental questions about how scientific knowledge should be constructed and validated. While some position these approaches as opposing ideologies [2], they are more productively viewed as complementary components of the scientific enterprise, each with distinctive strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications within the research lifecycle.

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Hypothesis-Driven Research (A Priori Approach)

Hypothesis-driven research follows a deductive logic structure, beginning with a specific, testable prediction derived from theoretical frameworks or previous observations. This a priori methodology employs a top-down approach where researchers formulate hypotheses before data collection and design experiments specifically to test these predetermined questions [1]. The process follows a structured sequence: existing knowledge → hypothesis formulation → targeted experiment design → data collection → hypothesis testing → conclusion.

In nutritional science, a classic example of this approach would involve investigating whether a specific micronutrient (e.g., vitamin D) affects bone density in elderly populations. Researchers would design a controlled trial with precise measurements of vitamin D intake and bone density outcomes, collecting only the data necessary to test their specific hypothesis about this relationship.

Data-Driven Research (A Posteriori Approach)

Data-driven research operates through inductive reasoning, beginning with comprehensive data collection without specific pre-formed hypotheses. This a posteriori methodology utilizes a bottom-up approach where researchers gather extensive datasets first, then apply analytical techniques to identify patterns, relationships, and potential hypotheses that emerge from the data itself [1] [2]. The sequence reverses: comprehensive data collection → pattern recognition → hypothesis generation → further testing.

A prominent example in modern nutritional epidemiology involves using metabolomics to analyze thousands of compounds in blood samples from large population cohorts. Without presupposing which metabolites might be important, researchers apply computational methods to discover which compounds correlate with disease states, thereby generating new hypotheses about metabolic pathways involved in disease pathogenesis [3].

The False Dichotomy

The purported tension between these approaches represents what some scholars term a "false dichotomy" [2]. In practice, robust research programs often integrate both methodologies at different stages of investigation. Data-driven exploration frequently identifies novel relationships that subsequently form the basis for precise hypothesis testing, while hypothesis-driven findings may open new avenues for broad exploratory analysis. The most impactful science typically occurs through iterative cycles between these modes rather than exclusive adherence to one paradigm.

Methodological Frameworks in Dietary Pattern Research

The distinction between a priori and a posteriori approaches finds particular relevance in nutritional epidemiology, specifically in the study of dietary patterns and disease relationships. These methodologies offer complementary approaches to understanding how overall eating patterns influence health outcomes.

A Priori Dietary Pattern Analysis

A priori dietary patterns are defined based on existing scientific knowledge, dietary guidelines, or theoretical frameworks about what constitutes a healthy or harmful diet. Researchers pre-specify scoring systems based on current understanding of nutritional science, then apply these predetermined patterns to study participants' dietary data.

Key Methodological Characteristics:

- Pre-defined scoring systems based on existing knowledge

- Hypothesis-testing orientation examining specific dietary theories

- Reduction of multidimensional data into single scores or indices

- Theoretical foundation in nutritional science and epidemiological evidence

Common A Priori Indices:

- Mediterranean Diet Score: Assesses adherence to traditional Mediterranean eating patterns characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains, and olive oil; moderate consumption of poultry, fish, and alcohol; and low consumption of red and processed meats [4].

- Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2010): Measures alignment with national dietary recommendations, evaluating adequacy of beneficial food groups and moderation of potentially harmful components [3].

- Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH): Scores adherence to a dietary pattern specifically designed to reduce blood pressure.

A recent meta-analysis of observational studies demonstrated the utility of this approach, finding that adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with a statistically significant 13% reduction in Parkinson's disease risk (RR = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.78–0.97), while healthy dietary patterns showed even stronger protective associations (RR = 0.76; 95%CI: 0.65–0.91) [4].

A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Analysis

A posteriori dietary patterns emerge empirically from the dietary data of the study population itself, using statistical techniques to identify common combinations of foods actually consumed by participants. These data-driven patterns are derived without pre-specified theoretical frameworks about what constitutes a healthy diet.

Key Methodological Characteristics:

- Patterns emerge from data rather than pre-defined theory

- Hypothesis-generating orientation discovering naturally occurring dietary combinations

- Multivariate statistical techniques to reduce dimensionality

- Population-specific patterns that reflect actual consumption habits

Common Statistical Techniques:

- Factor Analysis (Exploratory): Identifies underlying constructs (factors) that explain correlations between food groups.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Creates linear combinations of original food variables that capture maximum variance.

- Cluster Analysis: Groups individuals into distinct dietary patterns based on similarity of food intake profiles.

A study of the American Gut Project demonstrated the power of this approach, identifying five distinct a posteriori dietary patterns that were more strongly associated with gut microbiome variations than individual dietary features [3]. These included two Prudent-like diets (Plant-Based and Flexitarian), two Western-like diets with different health consciousness gradients, and an Exclusion diet pattern, with the Flexitarian pattern showing significantly higher gut microbiome alpha diversity compared to the most Western pattern.

Table 1: Comparison of A Priori and A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Methodologies

| Characteristic | A Priori Approach | A Posteriori Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical basis | Based on pre-existing knowledge or theory | Derived empirically from data |

| Hypothesis relationship | Tests specific hypotheses | Generates new hypotheses |

| Pattern definition | Pre-defined scoring systems | Statistically derived patterns |

| Primary techniques | Index scores based on guidelines | Factor analysis, PCA, cluster analysis |

| Key advantage | Grounded in established science | Reflects actual population eating patterns |

| Main limitation | Constrained by current knowledge | Population-specific, difficult to compare |

| Interpretation | Straightforward based on predefined criteria | Requires statistical and subject matter expertise |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for A Priori Dietary Pattern Analysis

Study Design and Participant Selection:

- Cohort Definition: Establish clear inclusion/exclusion criteria for observational studies (cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional designs) [4].

- Sample Size Calculation: Conduct power analysis based on expected effect sizes and outcome incidence.

- Ethical Compliance: Obtain institutional review board approval and participant informed consent.

Dietary Assessment Methods:

- Data Collection: Administer validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour dietary recalls, or food diaries.

- Nutrient Calculation: Use standardized food composition databases to estimate nutrient intakes.

- Quality Control: Implement procedures to ensure data completeness and accuracy, including range checks and cross-verification.

Dietary Pattern Construction:

- Index Selection: Choose appropriate a priori indices (e.g., Mediterranean Diet Score, HEI) based on research question.

- Component Definition: Define food group components and scoring criteria according to established protocols.

- Score Calculation: Compute individual adherence scores for each participant based on their dietary data.

Statistical Analysis:

- Model Specification: Employ multivariable regression models (Cox proportional hazards for cohort studies, logistic regression for case-control) adjusting for relevant confounders (age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking, education).

- Dose-Response Assessment: Test for linear trends across quartiles or quintiles of dietary pattern adherence.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct stratified analyses to examine effect modification and assess robustness of findings.

Protocol for A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Analysis

Dietary Data Preparation:

- Food Grouping: Aggregate individual food items into meaningful food groups based on nutritional similarity and usage.

- Energy Adjustment: Apply appropriate energy adjustment methods (residual or density methods) to account for differences in total energy intake.

- Data Transformation: Normalize or standardize intake variables as needed for multivariate analysis.

Pattern Derivation:

- Factorability Assessment: Evaluate data suitability for factor analysis using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure and Bartlett's test of sphericity.

- Factor Extraction: Apply principal component analysis or factor analysis to identify patterns based on correlation matrices.

- Factor Rotation: Use orthogonal (varimax) or oblique rotation to achieve simpler structure and enhance interpretability.

- Factor Retention: Determine number of patterns to retain using eigenvalues (>1.0), scree plot examination, and interpretability criteria.

- Factor Interpretation: Label derived patterns based on food groups with highest factor loadings (typically >|0.2| or >|0.3|).

Validation and Outcome Analysis:

- Internal Validation: Assess pattern stability through split-sample validation or bootstrapping techniques.

- Pattern Scores: Calculate factor scores for each participant representing their adherence to each derived pattern.

- Outcome Modeling: Examine associations between pattern scores and health outcomes using appropriate regression models with comprehensive confounding adjustment.

- Biological Plausibility: Interpret findings in context of existing biological knowledge and potential mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Findings from Dietary Pattern and Disease Research

| Dietary Pattern | Study Design | Participants/Cases | Risk Estimate (RR/OR/HR) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | Meta-analysis (11 studies) | 326,751 / 2,524 | RR = 0.87 | 0.78–0.97 [4] |

| Healthy Dietary Index | Meta-analysis (11 studies) | 326,751 / 2,524 | RR = 0.76 | 0.65–0.91 [4] |

| Healthy Dietary Pattern | Meta-analysis (11 studies) | 326,751 / 2,524 | RR = 0.76 | 0.62–0.93 [4] |

| Western Dietary Pattern | Meta-analysis (11 studies) | 326,751 / 2,524 | RR = 1.54 | 1.10–2.15 [4] |

| Plant-Based Pattern | American Gut Project | 744 participants | Microbiome association | P ≤ 0.0002 [3] |

| Flexitarian Pattern | American Gut Project | 744 participants | Higher alpha diversity | P ≤ 0.009 [3] |

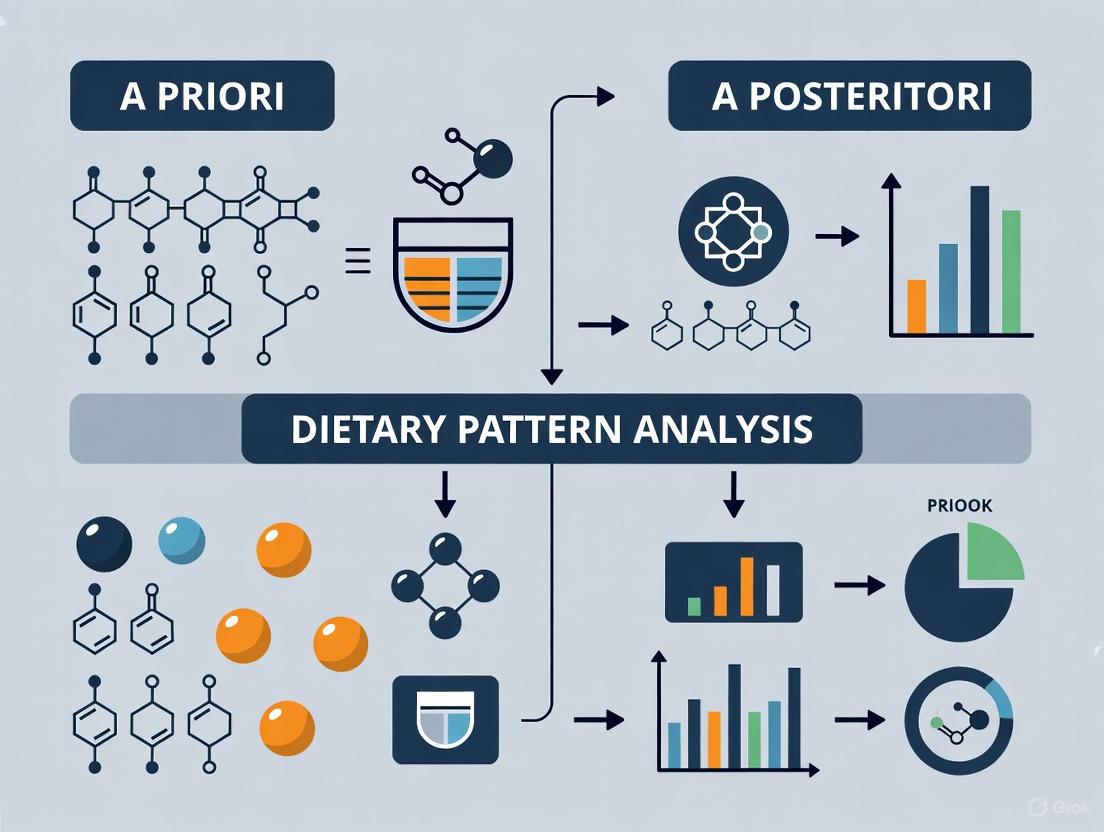

Visualization of Research Workflows

Hypothesis-Driven Research Workflow

Data-Driven Research Workflow

Integrated Research Approach

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Dietary Pattern Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment | Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ), 24-hour recalls, Food diaries | Capture comprehensive dietary intake data | Both a priori and a posteriori approaches |

| Statistical Analysis | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Factor Analysis, Cluster Analysis | Derive empirical dietary patterns from consumption data | Primarily a posteriori approach |

| Index Construction | Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index (HEI), DASH Score | Quantify adherence to pre-defined dietary patterns | Primarily a priori approach |

| Microbiome Analysis | 16S rRNA sequencing, Metagenomics | Characterize gut microbial community composition | Outcome measurement in nutritional studies |

| Data Management | REDCap, Nutrition Data Systems | Standardized data collection and management | Both approaches |

| Statistical Software | R, Python, SAS, SPSS, STATA | Implement statistical analyses and modeling | Both approaches |

The dichotomy between hypothesis-driven and data-driven approaches represents a false binary that fails to capture the dynamic, iterative nature of scientific progress [2]. Rather than opposing methodologies, these approaches function most effectively as complementary phases within integrated research programs. The distinction between a priori and a posteriori reasoning provides a valuable philosophical framework for understanding how different methodological approaches contribute to knowledge construction in nutritional epidemiology and systems biology.

Future research should leverage the synergistic potential of both paradigms, using data-driven approaches to identify novel patterns and generate hypotheses in our increasingly data-rich research environment, while employing hypothesis-driven methods to rigorously test these insights through targeted experimentation. This integrative approach promises to accelerate scientific discovery while maintaining the methodological rigor necessary for reliable knowledge generation. As the technological capacity for data collection and analysis continues to expand, the most successful research programs will be those that strategically employ both paradigms throughout the knowledge generation cycle.

The Rationale for Dietary Pattern Analysis Over Single-Nutrient Studies

Traditional research in nutritional epidemiology has predominantly focused on the relationship between single nutrients or individual foods and health outcomes. However, a significant paradigm shift toward dietary pattern analysis has occurred, recognizing that humans consume foods and nutrients in combination, not in isolation [5] [6]. This shift responds to several critical limitations of the single-nutrient approach, including the phenomenon of multicollinearity (high intercorrelations between dietary components), the synergistic and antagonistic effects between nutrients, and the statistical challenges of detecting small effect sizes from individual dietary components amid multiple testing [6] [7]. Dietary pattern analysis offers a holistic alternative that captures the complexity of whole diets as actually consumed, providing a more comprehensive framework for understanding diet-disease relationships and developing effective public health recommendations [5] [8].

The following visual conceptualizes the fundamental limitations of the single-nutrient approach that necessitated this paradigm shift toward dietary pattern analysis.

Fundamental Rationale for Dietary Pattern Analysis

Capturing Dietary Synergy and Complexity

The fundamental premise of dietary pattern analysis is that cumulative and interactive effects among dietary components reflect the biological reality of human consumption patterns [6]. Nutrients and foods are not metabolized in isolation but interact in complex ways that can produce synergistic or antagonistic effects on health outcomes. For instance, the effect of salt on hypertension may be moderated by the potassium and sugar content of the diet, and the absorption of certain micronutrients can be enhanced or inhibited by other dietary components [9]. These intricate interactions are largely invisible to single-nutrient analyses but are central to understanding how diet truly influences health. Dietary pattern analysis preserves these multidimensional relationships, providing a more biologically plausible model for nutritional research [5].

Addressing Methodological Limitations

From a methodological perspective, dietary pattern analysis addresses several critical limitations of the single-nutrient approach. The problem of multicollinearity, where highly correlated dietary variables violate statistical assumptions in traditional regression models, is naturally accommodated within pattern analysis [6] [7]. Furthermore, by analyzing the overall diet, this approach reduces the problem of multiple comparisons and the associated risk of false-positive findings that occur when examining numerous individual nutrients [6]. Perhaps most importantly, dietary pattern analysis can account for the substitution effects inherent in human eating behavior, where consuming more of one food typically means consuming less of another [7]. This holistic perspective enables researchers to identify the net effect of overall dietary habits rather than isolated components.

Enhancing Public Health Translation

Dietary patterns are more easily translated into meaningful public health messages and dietary guidelines than recommendations about individual nutrients [6] [8]. While few people conceptualize their diet in terms of specific nutrients, most can understand recommendations about overall eating patterns such as "consume more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains" or "follow a Mediterranean-style diet" [6]. This translational advantage is significant for implementing effective nutrition interventions and policies. As evidence of this utility, food-based dietary guidelines worldwide have increasingly adopted pattern-based recommendations, emphasizing the quantities, proportions, and variety of foods and drinks typically consumed rather than focusing on isolated nutrients [8].

Methodological Approaches: A Priori vs. A Posteriori Analysis

Dietary pattern methodologies are broadly categorized into three distinct approaches, each with unique rationales, applications, and methodological considerations. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Dietary Pattern Analysis Methodologies

| Characteristic | A Priori (Hypothesis-Driven) | A Posteriori (Exploratory) | Hybrid Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Predefined scores based on existing nutritional knowledge or dietary guidelines [5] [6] | Patterns derived empirically from dietary intake data using statistical methods [5] [6] | Combines prior knowledge with data-driven techniques [5] [7] |

| Rationale | Assess adherence to "ideal" dietary patterns linked to health [6] | Describe actual dietary behaviors within a specific population [6] | Explain diet-health relationships via intermediate factors [5] |

| Common Examples | Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), Healthy Eating Index (HEI), DASH score [5] [7] | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Factor Analysis, Cluster Analysis [5] [7] | Reduced Rank Regression (RRR), Partial Least Squares [5] [7] |

| Key Strengths | Easily reproducible and comparable across studies [6]; Strong theoretical foundation [6] | Not limited by existing scientific knowledge [6]; Reveals actual population eating patterns [10] | Incorporates biological pathways; Stronger predictive power for specific diseases [5] [11] |

| Major Limitations | Subjectivity in component selection [6]; Limited by current nutritional knowledge [6] | Patterns may not represent healthy eating [6]; Subjective analytical decisions [6] | Limited by knowledge of intermediate biomarkers [5]; Complex interpretation [5] |

| Primary Applications | Monitoring diet quality; Evaluating dietary interventions [6] | Understanding population dietary habits; Identifying target groups for interventions [6] | Investigating biological mechanisms linking diet to disease [5] |

A Priori (Hypothesis-Driven) Methods

A priori methods operationalize predefined hypotheses about what constitutes a healthy or harmful dietary pattern. Researchers develop scoring systems, often called dietary indices or scores, that reflect adherence to specific dietary guidelines or culturally-defined eating patterns associated with health outcomes [5] [6]. The Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), for instance, assesses conformity to traditional Mediterranean eating patterns characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil, with moderate fish and poultry intake and low red meat consumption [5]. Similarly, the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) measures alignment with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, while the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) score evaluates adherence to a dietary pattern specifically designed to reduce hypertension risk [5] [7].

The major advantage of a priori methods lies in their foundation in existing scientific evidence, making results interpretable within established theoretical frameworks and easily comparable across studies [6]. However, these methods are constrained by current nutritional knowledge and involve subjective decisions about which dietary components to include and how to score them [6]. Additionally, a priori scores developed in one population may not transfer effectively to others with different dietary cultures and food availability [11].

A Posteriori (Exploratory) Methods

In contrast to a priori approaches, a posteriori methods are data-driven and derive dietary patterns empirically from the dietary intake data of the study population without predefined hypotheses [5] [6]. These methods use multivariate statistical techniques to aggregate and reduce complex dietary data into a smaller set of patterns that explain the variation in eating behaviors within the population.

The most commonly used a posteriori methods include:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Factor Analysis: These techniques identify patterns based on correlations between food items or food groups, creating composite variables (components or factors) that explain the maximum variation in dietary intake [7] [11]. Typically, these methods identify patterns such as "Western" (characterized by red meat, processed meat, refined grains, and high-fat dairy) and "Prudent" or "Healthy" (characterized by fruits, vegetables, whole grains, poultry, and fish) in Western populations [5].

Cluster Analysis: This method groups individuals into distinct clusters based on similarities in their overall dietary intake, resulting in categories such as "healthy eaters," "traditional consumers," or "convenience food consumers" [8].

The primary strength of a posteriori methods is their ability to reveal actual dietary behaviors within a population without being constrained by existing nutritional hypotheses [6] [10]. However, these methods involve numerous subjective decisions during analysis (e.g., how to group foods, how many patterns to retain) and resulting patterns may not necessarily represent healthy or unhealthy eating [6].

Hybrid and Emerging Methodologies

Hybrid approaches combine elements of both a priori and a posteriori methods. Reduced Rank Regression (RRR), the most prominent hybrid method, uses prior knowledge to select intermediate response variables (often biomarkers) related to a specific disease and then identifies dietary patterns that explain the maximum variation in these response variables [5] [11]. For example, RRR might use biomarkers like HbA1c, HOMA-IR, and fasting glucose as responses to derive a dietary pattern most predictive of diabetes risk [11].

Emerging methodologies continue to expand the analytical toolbox for dietary pattern analysis:

Treelet Transform (TT): Combines PCA and cluster analysis to produce patterns that involve smaller, naturally grouped variables, potentially enhancing interpretability [5] [11].

Data Mining and Machine Learning: Techniques such as decision trees and neural networks can identify complex, non-linear relationships in dietary data and reveal specific patterns associated with health outcomes [12] [13].

Compositional Data Analysis (CODA): Accounts for the relative nature of dietary data (where intake of one component affects others because total intake is constrained) by transforming data into log-ratios [7].

Network Analysis: Methods like Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) map complex webs of interactions and conditional dependencies between individual foods, capturing both linear and non-linear relationships [9].

The workflow below illustrates how these different methodological approaches are applied in dietary pattern research, from data collection to pattern interpretation.

Experimental Protocols and Analytical Frameworks

Standardized Protocols for Dietary Pattern Derivation

Regardless of the specific methodological approach, deriving dietary patterns follows a general sequence of analytical decisions. The process begins with dietary data collection, typically using Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour recalls, or food records [5]. Next, researchers engage in food grouping, aggregating individual food items into meaningful categories (e.g., "whole grains," "red meat," "low-fat dairy") based on nutritional similarity and culinary use [10]. Evidence suggests that using food groups rather than individual food items explains more variation in dietary intake and produces more stable patterns [10].

For a posteriori methods like PCA, key analytical decisions include selecting the number of patterns to retain (based on eigenvalues >1, scree plots, or interpretability), rotating factors to enhance interpretability (using orthogonal or oblique rotation), and labeling patterns based on foods with high factor loadings [7]. For a priori methods, protocols involve defining dietary components for inclusion, establishing cut-points for scoring each component, and determining weighting and summation methods [6].

Validation and Reprodubility Assessment

Establishing the validity and reproducibility of derived dietary patterns is essential for robust research. Short-term stability can be assessed through test-retest studies, with evidence demonstrating that both a priori scores like the MedDietScore and a posteriori patterns derived from PCA show good stability over 15-day intervals [10]. Reproducibility over longer periods examines whether similar patterns emerge from different dietary assessments within the same population [10]. Validity is typically established by demonstrating expected associations with biomarkers (e.g., blood nutrient levels, inflammatory markers) or health outcomes [5] [11]. For instance, the Dietary Inflammatory Index was specifically developed based on associations with inflammatory biomarkers like C-reactive protein [11].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Elucidating Diet-Disease Relationships

Dietary pattern analysis has proven particularly valuable in understanding complex relationships between overall diet and chronic disease risk. Strong evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicates that dietary patterns characterized by higher consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish, low-fat dairy, and legumes, and lower consumption of red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages, and refined grains are associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, certain cancers, and premature mortality [8]. For example, the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee concluded that strong and consistent evidence links such dietary patterns with decreased CVD risk [8].

Different methodological approaches may yield complementary insights. In a study comparing PCA and RRR for diabetes prediction in China, PCA identified a "modern high-wheat" pattern positively associated with diabetes and a "traditional southern" pattern inversely associated, though associations attenuated after adjustment. In contrast, the RRR-derived pattern (combining elements of both PCA patterns) remained significantly associated with diabetes after adjustment, potentially demonstrating superior predictive power for specific outcomes [11].

Informing Clinical Trials and Therapeutic Development

For drug development professionals and clinical researchers, dietary pattern analysis offers several important applications. First, understanding population dietary patterns can help stratify research participants based on background diet, which may interact with pharmacological interventions. Second, dietary patterns can serve as important confounding variables that need adjustment in clinical trials evaluating drug efficacy. Third, dietary interventions themselves represent therapeutic approaches for chronic disease prevention and management, with patterns like the Mediterranean diet and DASH diet demonstrating efficacy comparable to pharmaceutical interventions for certain conditions [5] [11].

Table 2: Key Dietary Patterns and Their Documented Health Associations

| Dietary Pattern | Characteristics | Health Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | High fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil; moderate fish/poultry; low red meat [5] | Reduced cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cognitive decline, all-cause mortality [5] [8] |

| DASH Diet | Emphasis on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy; limited saturated fat, sugar, sodium [5] | Reduced hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke [5] [8] |

| Prudent/Healthy Pattern (a posteriori) | High vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish, poultry [5] | Reduced chronic disease risk, all-cause mortality [8] |

| Western Pattern (a posteriori) | High red/processed meat, refined grains, potatoes, high-fat dairy, sweets [5] | Increased obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, certain cancers [8] |

| Healthy Nordic Diet | Similar to Mediterranean but with rapeseed oil instead of olive oil; emphasis on Nordic foods [8] | Reduced cardiovascular risk, improved metabolic health [8] |

| MIND Diet | Hybrid of Mediterranean and DASH with emphasis on neuroprotective foods [5] | Reduced cognitive decline, neurodegenerative disease [5] |

Implementing robust dietary pattern analysis requires specific methodological tools and approaches. The following table outlines key resources for researchers designing studies in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Pattern Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Instruments | Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour recalls, food records [5] | Standardized collection of dietary intake data; FFQs most common for pattern analysis [5] |

| Food Grouping Systems | Standardized food grouping schemes, culture-specific groupings [10] | Aggregate individual foods into meaningful categories for pattern analysis [10] |

| Statistical Software Packages | SAS, R, STATA, SPSS, MATLAB [7] | Implement PCA, factor analysis, cluster analysis, RRR, and emerging methods [7] |

| A Priori Scoring Algorithms | Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Eating Index, DASH score calculators [5] [7] | Standardized calculation of predefined diet quality scores [5] |

| Emerging Method Packages | Treelet Transform, Gaussian Graphical Models, Data Mining algorithms [12] [7] [9] | Implement novel pattern analysis techniques beyond traditional methods [12] [9] |

| Validation Tools | Biomarker assays (nutrients, inflammatory markers), reproducibility statistics [5] [10] | Establish validity and reliability of derived dietary patterns [5] [10] |

Future Directions and Conceptual Challenges

Despite significant advances, dietary pattern analysis faces several conceptual and methodological challenges. A persistent limitation is the difficulty in identifying specific bioactive components responsible for observed health effects when analyzing entire dietary patterns [6]. Future research should integrate multi-omics approaches (metabolomics, microbiomics, genomics) to elucidate biological pathways through which dietary patterns influence health [5]. Additionally, most current methods assume dietary patterns are relatively static, whereas dynamic models capturing dietary changes over time are needed [9].

Methodologically, there is growing recognition that different analytical approaches should be viewed as complementary rather than competitive [14] [11]. The choice between a priori and a posteriori methods should be guided by the specific research question: a priori methods are ideal for testing hypotheses about adherence to recommended dietary patterns, while a posteriori methods better suit exploratory analyses of actual eating behaviors in populations [14] [6]. Future methodological development should focus on improving standardization of food grouping, pattern labeling, and validation procedures to enhance comparability across studies [10] [11].

For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the rationale and methodologies of dietary pattern analysis provides crucial context for interpreting the growing literature on diet-health relationships and designing studies that account for the complex, synergistic nature of human dietary intake. As the field continues to evolve, dietary pattern analysis will remain an essential approach for unraveling the complex relationships between nutrition and human health.

Key Characteristics of A Priori Methods (Diet Quality Scores and Indices)

In nutritional epidemiology, a priori dietary pattern analysis refers to an approach that evaluates the healthfulness of a diet based on pre-defined criteria grounded in current nutritional knowledge and evidence-based diet-health relationships [15]. Unlike exploratory, data-driven methods, a priori methods use scoring systems to assess an individual's adherence to conceptually defined dietary patterns considered important for health promotion and disease prevention [15] [10]. These dietary quality indices translate complex dietary intake data into quantifiable measures that reflect alignment with dietary guidelines or ideal dietary patterns, serving as powerful tools for researchers investigating relationships between overall diet and health outcomes [15] [16].

The fundamental premise of a priori methods is their basis in prior nutritional knowledge rather than dietary patterns specific to the study population. This approach allows for comparisons across different populations and studies, as the scoring criteria remain consistent regardless of the population's actual dietary habits [15] [11]. A priori methods are particularly valuable when researchers aim to test specific hypotheses about how adherence to recommended dietary patterns influences health outcomes, making them well-suited for prospective cohort studies and clinical trials where a predefined concept of "diet quality" is central to the research question [16] [17].

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Framework

Conceptual Basis of A Priori Methods

A priori dietary indices are founded on the principle that overall dietary patterns, rather than individual nutrients or foods, exert synergistic effects on health outcomes [11]. These indices are constructed based on current scientific evidence linking dietary components to chronic disease risk, with the objective of quantifying risk gradients for major diet-related diseases [15]. The theoretical framework typically derives from one of three approaches: dietary guidelines from national or international authorities (e.g., Healthy Eating Index based on U.S. Dietary Guidelines); culturally-specific healthy dietary patterns (e.g., Mediterranean Diet Scores); or evidence-based patterns targeting specific health outcomes (e.g., Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension - DASH) [16] [18].

The methodological framework for developing a priori indices follows established guidelines for constructing composite indicators, as outlined in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) handbook [15]. This systematic approach includes: (1) defining the theoretical framework considering index purpose and structure; (2) selecting appropriate indicators; (3) establishing normalization methods including scaling procedures and cutoff points; and (4) determining methods for weighting and aggregating index components [15]. This rigorous framework ensures that the resulting diet quality scores are scientifically sound, transparent, and fit for their intended purpose.

Comparison with A Posteriori Approaches

A priori methods differ fundamentally from a posteriori approaches in their underlying philosophy and application. A posteriori methods, such as principal component analysis or factor analysis, are exploratory techniques that derive dietary patterns empirically from available dietary intake data without pre-conceived hypotheses about what constitutes a "healthy" diet [11] [10]. These data-driven approaches identify common underlying consumption patterns within a specific study population, reflecting actual eating behaviors in that population [15] [11].

The table below summarizes the key distinctions between these two methodological approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of A Priori and A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Methods

| Characteristic | A Priori Methods | A Posteriori Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Pre-defined based on current nutritional knowledge | Derived empirically from study population data |

| Theoretical Framework | Based on established diet-health relationships | Exploratory, without pre-existing theoretical framework |

| Purpose | Assess adherence to "ideal" dietary patterns | Describe existing dietary patterns in a population |

| Transferability | Consistent across populations (if appropriate) | Population-specific, may not be reproducible |

| Validation | Against health outcomes and mortality | Internal consistency within the study population |

| Examples | Healthy Eating Index (HEI), Mediterranean Diet Score | Principal Component Analysis, Factor Analysis, Cluster Analysis |

A critical distinction lies in the interpretation of patterns: a priori methods explicitly define healthy versus unhealthy patterns based on current science, while a posteriori methods identify patterns that may or may not align with health promotion [15] [11]. For instance, a posteriori approaches might identify a "Western dietary pattern" characterized by high intakes of red meat, processed foods, and refined grains, but this pattern emerges from the data rather than being predefined as unhealthy [11]. This fundamental difference dictates their appropriate application in research settings, with a priori methods being preferable for testing hypotheses about adherence to recommended diets, and a posteriori methods being more suitable for exploring dietary behaviors in specific populations [10].

Core Components of A Priori Diet Quality Indices

Index Structure and Component Selection

The construction of a priori diet quality indices involves several methodological decisions that significantly influence their application and interpretation. The selection of components is a critical first step, with most indices including foods or nutrients with established relationships to health outcomes [15] [16]. Common components across multiple indices include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, and limits on red/processed meats, sodium, and sugary beverages [16] [17]. However, the specific components vary depending on the index's theoretical foundation—for example, Mediterranean diet scores typically include olive oil and moderate alcohol, while other indices may emphasize different components [15] [17].

The theoretical framework dictates not only which components are included but also how they are structured. Some indices balance "positive" components (foods to encourage) with "negative" components (foods to limit), while others focus exclusively on either approach [15]. The number of components ranges considerably across indices, from as few as 5-6 to more than 20, with implications for the index's sensitivity and practicality [15] [19]. The choice of components also reflects practical considerations about data availability, as more complex indices require detailed dietary assessment methods that may not be feasible in all research settings [15] [18].

Scoring Systems and Valuation Functions

The scoring methodology represents another critical element in a priori index construction. Valuation functions transform intake levels of each component into a score, typically using categorical (e.g., 0-1 binary scoring) or continuous approaches [15]. For component intake recommendations, three main types of valuation functions are employed: (1) step functions with dichotomous scoring based on meeting a threshold; (2) linear functions where scores increase proportionally with intake; and (3) non-linear functions that may incorporate optimal intake ranges with penalties for both insufficient and excessive consumption [15].

Normalization methods standardize scores across components with different measurement units, while cutoff points define thresholds for minimum and maximum scores [15]. These cutoff points may be based on absolute dietary recommendations (e.g., servings per day according to national guidelines) or on population-specific values (e.g., median or quintile distributions within the study sample) [15] [11]. The choice between absolute and relative cutoff points has significant implications for the index's applicability across different populations with varying dietary habits [11].

Weighting and Aggregation Methods

The aggregation of component scores into an overall diet quality index involves decisions about weighting—whether all components contribute equally or some receive greater weight based on their perceived importance for health [15]. Most commonly, indices use equal weighting for simplicity and transparency, though some employ evidence-based weighting schemes that reflect the strength of association between specific dietary components and health outcomes [15] [16].

The aggregation method itself can take various forms, including simple sums, means, or ratio-based approaches [15]. The choice of aggregation method affects the index's statistical properties and interpretation, with different approaches having distinct advantages and limitations. Regardless of the specific method chosen, transparency in the weighting and aggregation process is essential for appropriate interpretation and comparison across studies [15].

Methodological Implementation and Validation

Construction Workflow

The development of a robust a priori diet quality index follows a systematic workflow that incorporates both theoretical and methodological considerations. The diagram below illustrates the key stages in this process:

Research Toolkit for Implementation

Implementing a priori diet quality assessment in research requires specific methodological tools and considerations. The table below outlines key elements in the researcher's toolkit:

Table 2: Research Toolkit for A Priori Diet Quality Assessment

| Toolkit Component | Description | Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Methods | Instruments for collecting dietary intake data | Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs), 24-hour recalls, food records [10] [20] |

| Food Composition Databases | Resources for converting foods to nutrients | USDA Food Composition Database, country-specific nutrient databases [20] [18] |

| Index Scoring Algorithms | Computational procedures for calculating scores | Pre-defined formulas for HEI, DASH, Mediterranean diet scores [15] [17] |

| Validation Measures | Methods for assessing index performance | Correlation with biomarkers, prediction of health outcomes, reliability testing [16] [19] |

| Cultural Adaptation Frameworks | Approaches for tailoring indices to specific populations | Modification of food components, adjustment of portion sizes, inclusion of traditional foods [11] [21] |

Validation Approaches and Performance Assessment

Validating a priori diet quality indices involves assessing both their reliability (consistency of measurement) and validity (accuracy in measuring what they intend to measure) [10] [19]. Reliability testing often includes assessment of short-term stability through test-retest methods, with studies demonstrating good stability for indices like the MedDietScore over a 15-day interval [10]. The use of food groups rather than individual food items appears to enhance stability, explaining more variation in dietary intake (43-46% versus 23-25%) [10].

Validity assessment typically involves evaluating the index's ability to predict health outcomes, with successful indices demonstrating significant associations with reduced risk of chronic diseases, mortality, and more favorable health indicators [16] [17] [19]. For example, in a recent large-scale study of healthy aging, higher adherence to various a priori dietary patterns was associated with 45-86% greater odds of healthy aging, with the Alternative Healthy Eating Index showing the strongest association [17]. Validation also includes comparing index scores with objective biomarkers where possible, and assessing construct validity by examining relationships with socioeconomic, behavioral, and anthropometric variables [16] [19].

Current Applications and Research Evidence

Evidence from Recent Studies

Contemporary research continues to demonstrate the utility of a priori diet quality indices in predicting diverse health outcomes across population groups. A 2025 large-scale study examining eight dietary patterns in relation to healthy aging found that all patterns showed significant associations, with odds ratios for the highest versus lowest quintiles ranging from 1.45 for a healthful plant-based diet to 1.86 for the Alternative Healthy Eating Index [17]. This study defined healthy aging multidimensionally, encompassing freedom from major chronic diseases, intact cognitive and physical function, and good mental health at age 70 years or older [17].

Research in specific population subgroups includes studies in children and adolescents, where diet quality indices have shown associations with improved IQ, quality of life, blood pressure, body composition, and metabolic syndrome prevalence [19]. However, a systematic review noted that only a minority of pediatric indices have been adequately evaluated for validity and reliability, highlighting an important methodological consideration [19]. The application of these indices across diverse cultural contexts also requires careful consideration of local dietary patterns and food availability [11] [21].

Specific Index Performance

Different a priori indices demonstrate varying strengths in predicting specific health outcomes, reflecting their distinctive theoretical foundations and component emphasis:

Table 3: Performance of Selected A Priori Indices in Recent Research

| Diet Quality Index | Key Components | Associated Health Outcomes | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) | Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, long-chain fats, red/processed meat limitation | Strongest association with healthy aging (OR: 1.86); physical and mental health [17] | Multiple large prospective cohorts |

| Mediterranean Diet Scores | Fruits, vegetables, legumes, cereals, fish, olive oil, moderate alcohol | Reduced cardiovascular risk, diabetes incidence, association with healthy aging [11] [17] | Extensive observational and trial evidence |

| DASH Diet Score | Fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, whole grains, sodium limitation | Blood pressure reduction, cardiovascular risk reduction, hypertension prevention [16] [20] | Clinical trials and prospective studies |

| Healthful Plant-Based Diet Index (hPDI) | Plant foods with positive scoring for whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts | Modest association with healthy aging (OR: 1.45), weaker than other indices [17] | Emerging evidence from cohort studies |

| Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) | Multiple pro- and anti-inflammatory food components | Inflammatory biomarkers, chronic disease risk [11] [16] | Mixed evidence across populations |

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Challenges in Application Across Populations

A significant challenge in applying a priori diet quality indices across different populations relates to cultural and dietary heterogeneity [11] [21]. Indices developed for specific populations may not perform optimally in different settings due to varying dietary patterns and food availability [11]. For example, the Alternative Healthy Eating Index component for trans-fatty acid intake showed limited variability in an Australian population where trans-fat intakes are generally low, reducing its discriminative power [11]. Similarly, attempts to apply the Mediterranean Diet Score in non-Mediterranean populations may be constrained by the fact that even the highest-scoring individuals may not achieve intake levels comparable to traditional Mediterranean diets [11].

The cultural appropriateness of dietary indices is increasingly recognized as essential for their validity and applicability. Research with African American adults has highlighted the importance of adapting dietary guidance to ensure cultural relevance, including consideration of traditional foods and preparation methods [21]. This suggests that rigid application of standardized indices without cultural modification may limit their utility in diverse populations, pointing to the need for careful adaptation while maintaining the core health principles underlying the indices [21] [18].

Technical and Methodological Limitations

Several technical limitations affect the implementation and interpretation of a priori diet quality indices. Component selection involves inherent subjectivity, as researchers must decide which dietary aspects to include and how to define optimal intake levels amid sometimes inconsistent evidence [15] [16]. The weighting of components presents another challenge, with most indices using equal weighting for simplicity despite potential differences in the strength of association between various dietary components and health outcomes [15] [16].

Additional limitations include the lack of standardized cutoff values across indices, varying approaches to handling energy adjustment, and differences in whether indices emphasize increasing healthy foods, limiting unhealthy foods, or both [16]. The validation of scores with biomarkers or other objective assessment methods remains inconsistent, complicating decisions about the most appropriate indices for specific research contexts [16] [19]. Furthermore, many indices do not adequately address issues of dietary substitution—the conceptualization of what replaces what when certain foods are reduced—which may limit their utility for providing specific dietary guidance [16].

Future Directions and Innovations

The evolution of a priori diet quality indices continues with several emerging trends shaping their development. Integration of sustainability concerns represents a frontier in dietary pattern assessment, with newer indices such as the Planetary Health Diet Index incorporating environmental impact alongside health considerations [17] [18]. This reflects growing recognition that dietary guidance must address both human health and planetary boundaries [18].

Methodological innovations include the development of biomarker-based validation of indices to strengthen their objective basis, and efforts to create standardized scoring systems that maintain consistency while allowing for cultural adaptation [11] [16]. The 2014 proposal by Sofi et al. for a literature-based tool standardizing Mediterranean diet adherence scoring across populations exemplifies this direction [11]. Additionally, there is increasing attention to life-course approaches with age-specific indices, particularly for pediatric and older adult populations [19] [18].

As nutritional science evolves, future a priori indices will likely incorporate more nuanced understanding of diet-disease relationships, potentially including interactions with genetics, gut microbiota, and other individual factors [16]. The ongoing refinement of these indices will continue to enhance their utility for researchers, clinicians, and policymakers seeking to understand and promote dietary patterns that support optimal health throughout the lifespan.

Key Characteristics of A Posteriori Methods (Statistical Derivation)

Conceptual Foundation and Definition

A posteriori methods, often termed data-driven or exploratory methods, are a class of statistical techniques used to identify underlying structures or patterns directly from observed data without pre-specified theoretical frameworks. In the context of nutritional epidemiology, these methods derive dietary patterns based on the actual dietary intake data reported by a study population. The primary goal is to summarize a set of food consumption variables into a fewer number of patterns by leveraging the inter-correlations and co-variation among the foods consumed [11] [10] [20]. Unlike a priori approaches, which assess adherence to a pre-defined "ideal" diet, a posteriori methods aim to discover a population's "true" or habitual dietary habits, which may not be easily identifiable as simply "healthy" or "unhealthy" [11] [10]. These methods are considered completely exploratory, as they allow the data itself to reveal the predominant combinations of foods that characterize a population's diet [20].

The core principle behind a posteriori methods is the use of multivariate statistics to reduce data dimensionality. Given that individuals consume a wide variety of foods and nutrients that exhibit complex interactions and synergies, analysing single food items or nutrients in isolation can be limiting and prone to confounding [11] [20]. A posteriori methods address this complexity by identifying latent variables—the dietary patterns—that explain as much of the variation in food intake as possible. The patterns identified reflect the collective dietary behaviors within the study sample, capturing the reality that people eat meals consisting of multiple food items in combination, rather than consuming nutrients in isolation [11]. The resulting patterns are often given descriptive names based on the food items that load highly on them, such as "Western," "Traditional," "Prudent," or "Balanced" [11] [22].

Methodological Workflow

The application of a posteriori methods follows a structured, iterative process from data preparation through to pattern interpretation and validation. The workflow can be visualized as a sequence of key stages, each with distinct objectives and outputs.

Data Preparation and Aggregation

The initial and often most critical phase involves processing raw dietary data into a format suitable for pattern extraction. Dietary data is typically collected using instruments such as Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) or 24-hour dietary recalls, which record the consumption of numerous individual food items [10] [20]. A key decision at this stage is whether to use food items or aggregated food groups as the input variables. Using finely detailed food items can capture subtle dietary habits but may introduce noise and make pattern interpretation challenging. Conversely, aggregating individual foods into logically defined food groups (e.g., "whole grains," "red meat," "dairy") reduces the number of variables, minimizes within-person variation, and often leads to more stable and interpretable patterns that explain a greater proportion of the variance in dietary intake [10]. For instance, one study found that using 12 food groups explained 43-46% of the variance in intake, whereas using 50 individual food items explained only 23-25% of the variance [10].

Statistical Derivation and Interpretation

The core analytical phase employs multivariate techniques to identify patterns. The most common method is Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which uses an orthogonal transformation to convert a set of possibly correlated food variables into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components [11] [20]. These components are derived in order of their ability to explain the variance in the data. Another technique is Factor Analysis, which is similar to PCA but aims to describe the covariance structure by identifying underlying latent factors that cause the observed variables to co-vary [11]. Cluster Analysis is a related a posteriori method that groups individuals, rather than variables, into distinct clusters based on the similarity of their overall diets [11]. The choice of the number of patterns to retain is guided by statistical criteria (e.g., eigenvalues >1, scree plot) and interpretability [11].

The interpretation of the derived patterns is based on examining the factor loadings, which are correlation coefficients between the original food variables and the derived pattern. Food items or groups with high absolute loadings (positive or negative) contribute most to that pattern and are used to label and define it [11]. For example, a pattern with high positive loadings for fast food, processed meat, and refined grains might be labeled a "Western" pattern, whereas a pattern with high loadings for fruits, vegetables, and whole grains might be labeled "Healthy" or "Prudent" [11] [22]. It is crucial to note that the same pattern name (e.g., "Traditional") can represent vastly different food combinations in different cultural contexts, necessitating careful examination of the actual foods consumed [11].

Comparative Analysis of Statistical Techniques

A posteriori dietary pattern analysis employs several distinct statistical approaches, each with unique objectives, algorithms, and outputs. The selection of a specific technique directly influences how patterns are defined and how individuals are classified.

Table 1: Key Statistical Techniques for A Posteriori Dietary Pattern Derivation

| Technique | Primary Objective | Methodological Approach | Nature of Output | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [11] [20] | To reduce data dimensionality by creating new, uncorrelated variables that explain maximum variance. | Orthogonal transformation of original variables into principal components. | Continuous pattern scores for each individual for each derived component. | Maximizes explained variance; provides a quantitative score for association studies. | Patterns can be difficult to interpret as all variables have some loading on every component. |

| Factor Analysis [11] | To describe the underlying covariance structure by identifying latent factors. | Models covariance based on shared underlying latent constructs. | Continuous factor scores for each individual. | Can model measurement error; theoretically models causal latent traits. | More complex model assumptions; results can be similar to PCA. |

| Cluster Analysis [11] | To group individuals into distinct categories based on dietary similarity. | Partitions individuals into clusters to minimize within-cluster and maximize between-cluster distance. | Categorical variable assigning each individual to a single cluster. | Creates intuitive, mutually exclusive dietary typologies. | Loss of information by categorizing; sensitivity to choice of algorithm and distance metric. |

| Reduced Rank Regression (RRR) [11] | To derive patterns that maximally explain the variation in specific response variables (e.g., biomarkers). | Supervised method that finds linear combinations of predictors that explain response variation. | Continuous pattern scores. | Potentially stronger predictive power for specific health outcomes by incorporating biological pathways. | Patterns may not represent common eating habits in the population. |

| Treelet Transform (TT) [11] | To combine features of PCA and cluster analysis for dimension reduction with localized variable grouping. | Produces a cluster tree that allows visual examination of how variables group, yielding sparse factors. | Continuous factor scores involving a smaller number of naturally grouped variables. | Easier interpretation of factors as they involve fewer variables; visual output. | Requires subjective selection of the cut-level on the cluster tree. |

Advanced and Hybrid Techniques

Beyond the classical methods, advanced techniques like Reduced Rank Regression (RRR) and Treelet Transform (TT) offer unique advantages. RRR is a supervised method because it derives dietary patterns not only based on food consumption data but also by maximizing their predictive power for pre-specified intermediate biomarkers or disease outcomes (e.g., glycated hemoglobin, inflammatory markers) [11]. This can result in patterns that are more strongly associated with the disease under investigation, as they are constrained by biological pathways. For example, one study found that an RRR-derived pattern was significantly associated with diabetes even after adjustment for confounders, whereas PCA-derived patterns were not [11]. In contrast, Treelet Transform is an unsupervised method that merges the benefits of PCA and cluster analysis. It produces a cluster tree, providing a visual representation of how food variables group together, and yields factors that are easier to interpret than PCA factors because each factor involves a smaller, naturally grouped set of variables [11].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Standard Protocol for Principal Component Analysis

The most widely used method for deriving a posteriori dietary patterns is Principal Component Analysis. The following provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol based on established research practices [11] [10] [20].

- Dietary Data Collection and Preprocessing: Collect dietary intake data using a validated dietary assessment tool, such as a semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). The frequency of consumption for each food item is converted to daily intake in grams. Energy adjustment is typically performed using the residual method or by calculating the density of food intake (servings per 1000 kcal).

- Food Grouping: Collapse individual food items from the FFQ into logically defined, mutually exclusive food groups based on similarity of nutrient profile and culinary use (e.g., "whole grains," "refined grains," "red meat," "leafy green vegetables"). This step reduces the number of variables and minimizes random variation.

- Factorability Assessment: Check the suitability of the data for PCA. This is often done using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (values >0.6 are acceptable) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (a significant p-value indicates that correlations between variables are sufficiently large for PCA).

- Component Extraction: Perform PCA on the correlation matrix of the food groups. The number of components to retain is determined by a combination of:

- The Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues >1).

- The scree plot, a graphical representation of eigenvalues where the point of inflection is identified.

- The interpretability of the components, ensuring they explain a meaningful cumulative proportion of variance (often >20%).

- Rotation: Apply an orthogonal rotation (most commonly Varimax) to the retained components. Rotation simplifies the factor structure, maximizing high loadings and minimizing low ones for each component, which aids in interpretation.

- Interpretation and Labeling: Interpret the rotated components by examining the factor loadings. Food groups with high absolute loadings (e.g., > |0.2| or > |0.3|) are considered to contribute significantly to a pattern. Each pattern is labeled based on the foods that load highly on it (e.g., a pattern with high loadings for fast food, processed meat, and fries is labeled "Western").

- Calculation of Pattern Scores: For each participant and each retained pattern, calculate a dietary pattern score. This is typically done by summing the intake of each food group weighted by its factor loading. These scores are standardized and used in subsequent analyses to test associations with health outcomes.

Protocol for Assessing Pattern Stability

A critical step in validating a posteriori patterns is testing their stability and reliability over time. The following protocol, adapted from Bountziouka et al., assesses short-term reliability [10].

- Study Design: A sample of participants (e.g., n=500) completes the same dietary assessment tool (e.g., a 76-item FFQ) twice within a short, predefined interval (e.g., 15 days) to minimize true changes in diet.

- Pattern Derivation per Administration: Apply the same PCA protocol (as described in Section 4.1) independently to the dietary data from the first and second administrations.

- Comparative Analysis:

- Compare the patterns derived from the two time points based on the similarity of the factor loadings for the key food groups.

- Compare the variance explained by the patterns from each administration.

- Assess the stability of individual classification by calculating the correlation (e.g., Kendall's tau-b) between the pattern scores from the two administrations.

- Sensitivity Analysis with Food Groups: Repeat the PCA and stability analysis using aggregated food groups instead of individual food items. Research indicates that using food groups typically results in patterns that explain a higher percentage of variance and demonstrate stronger stability metrics [10].

Successfully implementing a posteriori dietary pattern analysis requires a combination of specific data resources, statistical tools, and methodological components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for A Posteriori Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) [10] [20] | A validated, semi-quantitative questionnaire assessing habitual intake of a comprehensive list of foods and beverages over a specified period. | The primary instrument for collecting dietary intake data, which serves as the raw material for pattern derivation. |

| Food Composition Table (FCT) [20] | A database detailing the nutrient content of foods. Used to calculate nutrient intakes and aid in food grouping. | Essential for energy adjustment and for creating meaningful, nutritionally coherent food groups for analysis. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, SAS, SPSS, Stata) | Software platforms with robust multivariate statistical procedures. | Used to perform the core analyses: Principal Component Analysis, Factor Analysis, Cluster Analysis, and Reduced Rank Regression. |

| Varimax Rotation [11] | An orthogonal rotation method used in factor analysis to simplify the structure of the factor loadings matrix. | Applied after factor extraction to achieve a simpler, more interpretable structure where each variable loads highly on as few factors as possible. |

| Food Grouping Schema [10] | A pre-defined system for aggregating individual food items from an FFQ into broader, meaningful categories. | Reduces data dimensionality and noise, leading to more stable and interpretable dietary patterns. |

| Stability Metrics (e.g., Kendall's tau-b) [10] | Statistical measures of rank correlation used to assess the test-retest reliability of derived pattern scores. | Quantifies the short-term stability of the dietary patterns and the consistency of individual classification. |

Analytical Pathways and Research Outcomes

The ultimate goal of deriving a posteriori dietary patterns is to link them to health outcomes, a process that involves multiple analytical steps and decision points. The following diagram maps the logical pathway from raw data to public health insight.

This analytical pathway yields critical insights. For instance, a recent meta-analysis found that a posteriori-derived "Western dietary pattern" was associated with a 54% increased risk of Parkinson's Disease (RR=1.54), while a "Healthy dietary pattern" was associated with a 24% reduced risk (RR=0.76) [22]. However, not all analyses find significant associations, as seen in a prospective study where neither a healthy nor an unhealthy a posteriori pattern was associated with the risk of hypertension, highlighting the context-dependent nature of these findings [20]. The robustness of these conclusions hinges on the careful execution of each step in the methodological workflow, from data collection through to statistical derivation and validation.

Comparative Strengths and Limitations of Each Foundational Approach

Dietary pattern analysis has emerged as a fundamental methodology in nutritional epidemiology, shifting the focus from individual nutrients to the complex combinations of foods that constitute whole diets [7]. This shift recognizes that humans consume foods with multiple interacting components rather than isolated nutrients, and these interactions create synergistic or antagonistic effects on health outcomes [12]. The two foundational approaches for analyzing dietary patterns are classified as a priori (investigator-driven) and a posteriori (data-driven) methods, each with distinct philosophical underpinnings, methodological frameworks, and applications in research settings [7] [12].

A priori methods are defined by investigator-driven hypotheses based on existing nutritional knowledge, dietary guidelines, or scientific evidence about diet-disease relationships [7] [23]. These approaches operationalize predefined dietary concepts into quantitative scores that measure adherence to recommended eating patterns. In contrast, a posteriori methods are empirically derived from population dietary data without predetermined nutritional hypotheses [12] [23]. These data-driven approaches use statistical techniques to identify existing eating patterns within study populations, allowing unique dietary cultures and habits to emerge from the data itself [24].

The comparative analysis of these foundational approaches provides researchers with critical insights for selecting appropriate methodological frameworks based on specific research questions, study populations, and analytical resources. This technical guide examines the strengths, limitations, and applications of each approach within the broader context of nutritional epidemiology and dietary pattern research.

Methodological Foundations

A Priori (Investigator-Driven) Approaches

Core Principles and Development

A priori methods are grounded in nutritional science evidence and dietary recommendations, translating existing knowledge into structured scoring systems [7]. The fundamental principle underlying these approaches is that dietary guidelines based on extensive research can be operationalized to evaluate how closely individuals' diets align with patterns associated with health outcomes [7]. Researchers develop these scoring systems by selecting food components, defining intake thresholds, and assigning points based on adherence to recommendations, creating a composite score that represents overall diet quality [7].

The development process involves several systematic stages: First, researchers identify relevant dietary components based on current scientific evidence and dietary guidelines. Second, they establish scoring criteria for each component, typically defining optimal intake ranges. Third, they determine weighting schemes that may assign equal or differential importance to various components. Finally, they validate the scores against health outcomes to ensure they predict relevant disease endpoints [7]. This rigorous development process ensures that a priori scores reflect current scientific understanding of diet-disease relationships while maintaining practical applicability in research settings.

Common A Priori Indices and Their Components

Several well-established a priori indices are widely used in nutritional epidemiology, each with distinct compositional frameworks:

Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI): Developed as an enhancement to the original Healthy Eating Index, the AHEI showed the strongest association with healthy aging in a recent large prospective study, with an odds ratio of 1.86 (95% CI: 1.71-2.01) comparing the highest to lowest quintiles [17]. The index emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, long-chain fats, and polyunsaturated fatty acids while discouraging red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages, trans fats, and sodium [17].

Alternative Mediterranean Diet Score (aMED): This index operationalizes the traditional Mediterranean diet pattern, characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains, and extra-virgin olive oil; moderate consumption of poultry, fish, and alcohol; and low consumption of red and processed meats [4] [17]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with an 13% decreased risk of Parkinson's disease (RR = 0.87; 95% CI: 0.78-0.97) [4].

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH): This pattern emphasizes nutrients associated with blood pressure regulation, including high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and limited red meat, saturated fats, and sweets [7] [17].

Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII): This index quantifies the inflammatory potential of diet based on scientific evidence linking dietary components to inflammatory biomarkers [23]. In a prospective cohort study of 189,561 participants, higher DII scores were associated with a 17% increased risk of lung cancer (HR T3 vs. T1: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.36) [23].

Healthful Plant-Based Diet Index (hPDI): This index assesses adherence to a plant-based diet that emphasizes healthy plant foods while still accounting for the quality of plant-based components [17]. In healthy aging research, hPDI demonstrated the weakest association among the dietary patterns examined (OR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.35-1.57) [17].

Table 1: Major A Priori Dietary Indices and Their Components

| Index Name | Key Components | Scoring Range | Primary Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) | Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, unsaturated fats | 0-110 | Healthy aging (OR=1.86), chronic disease prevention [17] |

| Alternative Mediterranean Diet (aMED) | Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, fish | 0-9 | Neurodegenerative disease risk reduction (RR=0.87) [4] [17] |

| DASH Diet | Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, limited red meat | 0-10 | Blood pressure control, cardiovascular health [7] |

| Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) | Pro- and anti-inflammatory food components | Varies | Lung cancer risk (HR=1.17), inflammatory diseases [23] |

| Healthful Plant-Based Diet Index (hPDI) | Whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, teas & coffee | 0-90 | Healthy aging (OR=1.45), metabolic health [17] |

A Posteriori (Data-Driven) Approaches

Statistical Foundations and Techniques

A posteriori methods utilize statistical dimensionality reduction techniques to identify eating patterns that naturally exist within population dietary data [7] [12]. These approaches are founded on the principle that dietary behaviors exhibit covariance structures that can be captured through multivariate statistical methods, allowing researchers to identify common combinations of foods that people actually consume without predefined nutritional hypotheses [7].

The most commonly applied a posteriori techniques include: