Addressing Nutrient Depletion in High-Yielding Crops: Strategies for Enhancing Nutritional Density in Modern Agriculture

This article examines the critical challenge of nutrient depletion in high-yielding crop varieties, a growing concern for global food security and human health.

Addressing Nutrient Depletion in High-Yielding Crops: Strategies for Enhancing Nutritional Density in Modern Agriculture

Abstract

This article examines the critical challenge of nutrient depletion in high-yielding crop varieties, a growing concern for global food security and human health. It explores the scientific foundation of this issue, linking intensive agricultural practices to reduced micronutrient density in staple crops. The content provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative methodologies, from speed breeding to precision nutrient management, aimed at enhancing nutritional quality without compromising yield. Further, it troubleshoots implementation barriers and evaluates the efficacy of various approaches through comparative analysis of research findings. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and agricultural specialists, this review synthesizes current evidence and identifies future directions for developing nutritionally optimized crop varieties within sustainable production systems.

The Hidden Hunger Crisis: Understanding Nutrient Decline in Modern Crop Varieties

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the "Genetic Erosion Paradox" in the context of modern crops? The "Genetic Erosion Paradox" refers to the seemingly contradictory situation where the development of high-yielding crop varieties has successfully boosted global food production, yet has often resulted in a significant decline in the nutrient density of these foods. This creates a scenario where we have more food but less nutrition per calorie consumed [1] [2].

2. What are the primary drivers behind the decline in nutrient density? Research points to two interconnected categories of drivers:

- Genetic Dilution Effect: The selective breeding of high-yielding varieties has often prioritized traits like rapid growth and enlarged endosperm (the starchy part of the grain). This can lead to a "dilution" of vitamins and minerals, as the accumulation of carbohydrates outpaces that of micronutrients [2].

- Agronomic & Soil Health Factors: Intensive farming practices can deplete soil organic matter and disrupt the complex web of soil microbes and mycorrhizal fungi. These soil organisms are crucial for breaking down nutrients into forms that plants can readily absorb. Their decline can impair a plant's ability to uptake nutrients, regardless of the genetic potential of the variety [3] [2].

3. How significant is the measured decline in nutrient content? Multiple studies across decades have documented substantial declines. The table below summarizes key findings from analyses of fruits and vegetables, showing losses in essential minerals and vitamins over the latter half of the 20th century [3].

Table 1: Documented Decline in Nutrient Content of Fruits and Vegetables

| Nutrient | Reported Decline (%) | Time Period | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca) | 16% - 46% | Over 50-70 years | [3] |

| Iron (Fe) | 15% - 36% | Over 50-70 years | [3] [2] |

| Potassium (K) | 6% - 19% | Over 50-70 years | [3] |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 16% - 35% | Over 50-70 years | [3] |

| Copper (Cu) | 20% - 81% | Over 50-70 years | [3] |

| Vitamin A | 18% - 38% | Over 50 years | [3] |

| Vitamin C | 15% - 30% | Over 50 years | [3] |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 38% | Since 1950 | [2] |

4. Why is genetic diversity crucial for addressing this paradox? Genetic diversity is the raw material for adaptation and resilience. A narrow genetic base in modern cultivars makes the entire agricultural system more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate change. Furthermore, it limits the genetic "toolkit" available to breeders to develop new varieties that are both high-yielding and nutrient-dense. Traditional landraces and crop wild relatives often contain valuable genes for stress tolerance and nutrient accumulation that have been lost in modern varieties [1] [4].

5. What is the "extinction vortex" and how does it relate to genetic erosion? The "extinction vortex" is a theoretical model describing a dangerous feedback loop. In conservation biology, it explains how small population size leads to increased inbreeding and genetic drift, which erodes genetic diversity and reduces individual fitness. This, in turn, causes the population to decline further, leading to even more genetic erosion and hindering the population's ability to adapt to environmental change. This concept is highly relevant to cultivated systems where reliance on a few uniform varieties can create a similar genetic vulnerability [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Inconsistent Nutrient Density Results in a Controlled Pot Experiment

- Potential Cause: The soil or growth medium used may not have a active and healthy microbial biome, which is critical for nutrient solubilization and plant uptake.

- Solution:

- Inoculate with Mycorrhizal Fungi: Introduce commercial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculants (e.g., products based on Glomus species). These fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, dramatically extending their absorptive surface area and enhancing the uptake of immobile nutrients like phosphorus and zinc [2].

- Test Soil Health Metrics: Move beyond standard NPK soil tests. Incorporate measurements of Soil Organic Matter (SOM), microbial biomass carbon, and potentially conduct a root stain-and-microscope assay to verify mycorrhizal colonization rates.

Problem 2: Failure to Find Correlations Between Yield and Target Nutrient Traits

- Potential Cause: The genetic background of your plant material may be too narrow, lacking sufficient variation for the nutrient trait of interest.

- Solution:

- Incorporate Diverse Germplasm: Expand your experimental lines to include heirloom varieties, traditional landraces, and where possible, carefully crossed lines with crop wild relatives. This widens the genetic pool and increases the likelihood of finding positive trait associations [4].

- Utilize Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS): If resources allow, employ GWAS on a diverse panel of accessions. This can help identify specific genetic markers linked to high nutrient density, which can then be used in marker-assisted selection.

Problem 3: Confounding Environmental Effects in Field Trials Masking Genetic Potential

- Potential Cause: Underlying spatial variability in soil properties (e.g., texture, organic matter, micronutrients) across your experimental plots can be greater than the treatment effects you are trying to measure.

- Solution:

- Implement Precision Agriculture Techniques:

- Soil Electroconductivity (EC) Mapping: Before planting, conduct an EC survey to map soil variability.

- Zone-based Soil Sampling: Collect soil samples based on these zones rather than on a simple grid to better characterize variation.

- End-of-Season Remote Sensing: Use drone or satellite-derived vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) to map spatial variation in crop performance and correlate it with soil and yield data [6].

- Use Spatial Statistics in Analysis: Employ statistical models like spatial regression (e.g., including AR1 x AR1 covariance structures) to account for and remove the influence of field gradients and patches from your treatment effects.

- Implement Precision Agriculture Techniques:

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Integrated Soil and Plant Tissue Analysis for Nutrient Audits

- Objective: To comprehensively assess the relationship between soil nutrient availability and actual plant nutrient uptake.

- Materials: Soil probe, sample bags, labeling tags, plant sampling shears, paper bags, forced-air oven, mortar and pestle, ICP-OES/MS analyzer.

- Methodology:

- Soil Sampling: At key growth stages (e.g., planting, flowering), collect composite soil samples from the root zone (0-15 cm and 15-30 cm depths) from multiple locations per experimental plot. Air-dry, gently crush, and sieve through a 2-mm mesh [6].

- Tissue Sampling: Simultaneously, collect the most recently matured leaves (a standard diagnostic tissue for most crops) from multiple plants per plot. Avoid diseased or damaged leaves.

- Sample Preparation:

- Soil: Analyze for pH, EC, available P (Olsen or Bray), exchangeable K, Ca, Mg, and DTPA-extractable micronutrients (Zn, Cu, Fe, Mn).

- Plant Tissue: Rinse with deionized water, dry in an oven at 70°C to constant weight, and grind to a fine powder.

- Nutrient Analysis: Digest the plant tissue powder (e.g., using nitric-perchloric acid digestion) and analyze the digestate using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) for a full suite of mineral nutrients [6].

- Data Interpretation: Correlate soil test values with tissue concentrations to identify nutrient deficiencies, antagonisms, or luxury consumption. This helps determine if a yield-nutrient density trade-off is due to genetics or a soil-level bottleneck.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Genetic Erosion on Population Stability

- Objective: To model how a reduction in genetic diversity can affect the temporal stability of a key population-level trait (e.g., biomass) in response to environmental fluctuations. This ecological concept is directly relevant to the resilience of a crop variety.

- Materials: Seeds from populations with known and varying levels of genetic diversity (e.g., a modern F1 hybrid vs. a diverse landrace population), controlled environment growth chambers or replicated field plots, environmental data loggers, precision scales.

- Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: Establish a randomized complete block design with multiple replicates of each population type.

- Apply Environmental Fluctuation: Subject the plants to a controlled, fluctuating stressor (e.g., alternating cycles of sufficient and moderate water deficit) throughout the growing season. Maintain a control group under stable conditions.

- Data Collection: At regular intervals, non-destructively measure plant biomass (or a proxy like canopy cover). At harvest, destructively sample and record final biomass.

- Calculate Stability: For each population, calculate the temporal stability of biomass as the ratio of the mean biomass to its standard deviation over the measurement periods

(Mean / SD). A higher value indicates greater stability [7].

- Data Interpretation: Compare the temporal stability metrics between the high-diversity and low-diversity populations. Research on wild fish populations has demonstrated that genetically eroded populations exhibit significantly lower biomass stability over time, making them more vulnerable to extinction [7]. A similar result in plants would powerfully illustrate the hidden risk of narrow genetic bases.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Investigating Nutrient Density

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Mycorrhizal Inoculant | Enhances nutrient (especially P, Zn) and water uptake by extending the root system. | Commercial powders containing Rhizophagus irregularis; use as a seed coating or in planting holes [2]. |

| ICP-OES/MS | Precisely quantifies the concentration of a wide array of mineral elements in plant and soil samples. | Essential for generating high-throughput nutrient density data. |

| DTPA Extractant | A chelating solution used to estimate the bioavailable fraction of micronutrients (Zn, Fe, Cu, Mn) in soil. | Standard reagent for soil testing labs; critical for correlating soil and plant nutrient status [6]. |

| SNP Genotyping Panel | Used for genotyping diverse germplasm to assess genetic diversity and perform GWAS for nutrient traits. | Can be customized for specific crops to identify genetic markers for nutrient accumulation. |

| Controlled Environment Chambers | Allows for the precise application of environmental stresses (drought, heat) to study GxE interactions on nutrient partitioning. | Necessary for disentangling genetic and environmental effects. |

| Multispectral Sensor (Drone-mounted) | Measures crop reflectance to derive vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) correlated with biomass, chlorophyll, and nitrogen status. | Enables non-destructive, high-resolution spatial monitoring of field trials [6]. |

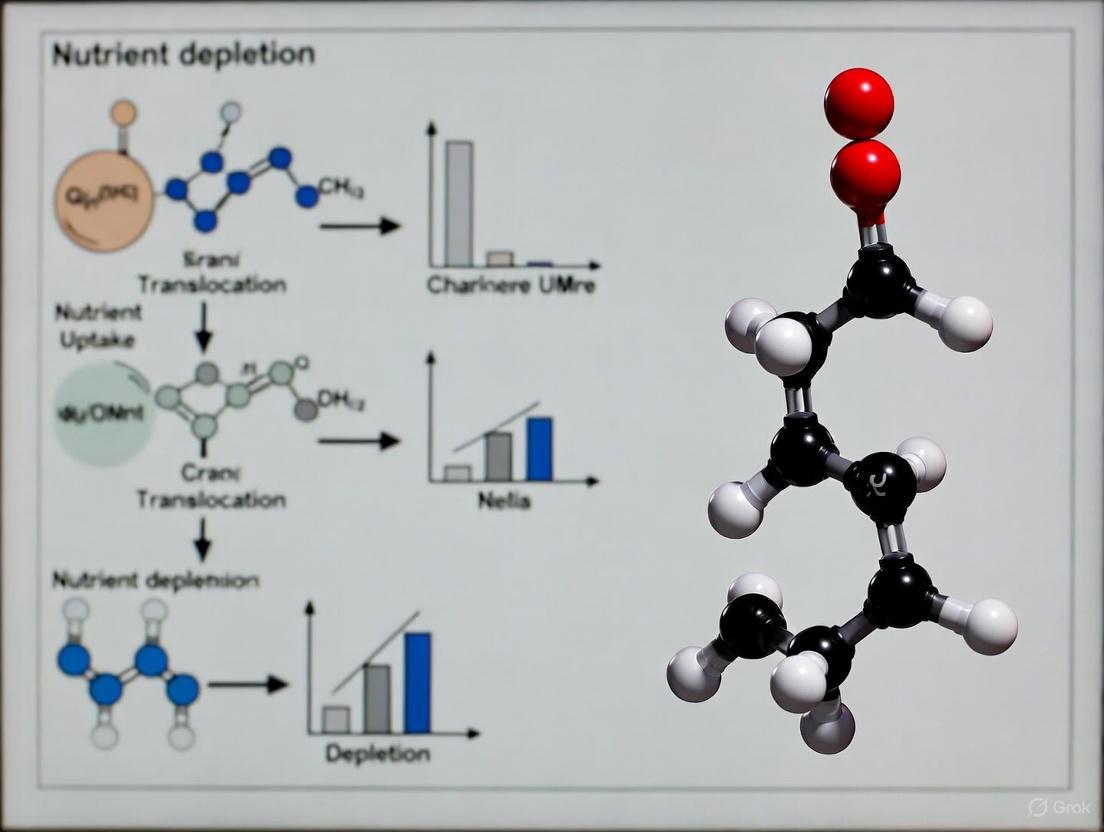

Conceptual Diagrams

The Genetic Erosion Paradox: Causal Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Nutrient Density Research

Agricultural Intensification and Soil Health Degradation

Core Concepts and Indicators

Frequently Asked Questions

What defines a "healthy" agricultural soil? Soil health is defined as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans. Healthy soils perform five essential functions: regulating water, sustaining plant and animal life, filtering and buffering potential pollutants, cycling nutrients, and providing physical stability and support [8]. From a research perspective, health is assessed through integrated physical, chemical, and biological indicators [9].

Why does agricultural intensification specifically threaten soil resilience? Agricultural intensification simplifies agroecosystem structure and function, reducing internal balancing feedback loops. Conventional practices like intensive tillage and imbalanced fertilization create reinforcing feedback loops that lead to long-term degradation. For example, tillage initially mineralizes organic matter for short-term yield gains but long-term repeated use declines soil organic matter, aggregate stability, and beneficial biota, creating dependence on further tillage or increased inputs [10].

How does soil health degradation directly impact high-yielding crop variety research? Degraded soils create a significant mismatch between the genetic potential of improved varieties and the soil's ability to support that potential. Soil degradation can reduce crop yields by up to 40% when pH falls outside the optimal 6.0-7.5 range [9]. Furthermore, an increase in temperature of 1°C is estimated to increase pest incidence by 10-25% and reduce major crop yields by up to 7.4% [11], compromising field trial results.

Quantitative Soil Health Indicators

Table 1: Essential Soil Health Indicators for Research Monitoring

| Indicator | Importance for Sustainable Farming | Ideal Value/Range | Estimated Yield/Resilience Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Organic Matter | Boosts fertility, water retention, and microbial activity | 3–6% | High—1% increase can lift water retention by up to 25% and enhance yield stability [9] |

| pH Level | Affects nutrient availability and microbial function | 6.0–7.5 | High—Outside ideal range, yields may drop by up to 40% [9] |

| Nutrient Content (N, P, K) | Supports robust plant growth and food production | N: 20–40 mg/kg; P: 10–30 mg/kg; K: 80–180 mg/kg | Moderate–High—Direct impact on yield and crop quality [9] |

| Microbial Activity | Drives nutrient cycling and disease suppression | 20–40 mg CO₂/kg soil/day (soil respiration) | High—Resilient, fertile, and adaptable soils [9] |

| Bulk Density (Compaction) | Impacts root growth, infiltration, and microbial habitat | 1.1–1.4 g/cm³ (for most loams) | Moderate—Improved rooting and water use efficiency [9] |

Diagnostic and Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Yield Stagnation Despite Optimal Genetics

Observable Symptoms:

- Declining yield trends in controlled experiments despite genetic improvements

- Increased variability in replicate plot performance

- Inconsistent response to fertilizer applications across trial sites

Underlying Mechanisms: The system dynamics of soil degradation under conventional agricultural management involve several reinforcing feedback loops that lead to yield stagnation [10]:

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Comprehensive Soil Analysis: Test physical (bulk density, aggregate stability), chemical (pH, NPK, CEC), and biological (microbial biomass, soil respiration) parameters [9]

- Soil Organic Carbon Monitoring: Track SOC changes over time - levels below 1.5% indicate severe degradation [12]

- Nutrient Use Efficiency Assessment: Calculate NUE using the formula: NUE = (YieldN - Yield0) / N_applied, where values below 40% indicate inefficiency [13]

Problem: Nutrient Use Efficiency Decline

Troubleshooting Guide: Table 2: Nutrient Management Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Root Cause | Diagnostic Measurements | Corrective Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Nitrogen Use Efficiency | Excessive application, poor timing, imbalanced ratios | NUE calculation, soil nitrate testing, leaf chlorophyll monitoring | Implement 4R nutrient stewardship: Right source, rate, time, and place [13] |

| Phosphorus Fixation | Acidic soils, improper placement | Soil pH, P-sorption tests, root architecture analysis | Band application with sulfuric acid amendment; pH adjustment to 6.0-6.5 [13] |

| Micronutrient Deficiencies | High pH, compaction, organic matter decline | DTPA extractable micronutrients, plant tissue analysis | Foliar applications, organic amendments, pH management [9] |

Experimental Remediation Protocols

Integrated Nutrient Management Protocol

Objective: Restore nutrient cycling efficiency in degraded experimental plots while maintaining research integrity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Controlled-release fertilizer formulations (NPK customized to crop need)

- Quality-composted farmyard manure (FYM) or vermicompost

- Bioinoculants (PGPR, mycorrhizal fungi, N-fixers)

- Soil amendments (lime for acidic soils, sulfur for alkaline soils)

- Cover crop seeds (legumes, brassicas, grasses)

Methodology:

- Soil Preparation and Characterization

- Collect baseline soil samples (0-15 cm, 15-30 cm depth)

- Analyze physical, chemical, and biological parameters as in Table 1

- Calculate amendment requirements based on soil test results

Treatment Application

- Apply integrated treatment: 75% NPK + 10 t ha⁻¹ FYM + bioinoculants [13]

- Incorporate controlled-release fertilizers for consistent nutrient supply

- Inoculate seeds with selected microbial consortia

Cover Crop Integration

- Establish multi-species cover crops between cash crop cycles

- Monitor root development and biomass production

- Terminate cover crops at flowering stage for optimal nutrient release

Performance Assessment

- Measure yield parameters and nutrient content in harvested material

- Track soil health indicators at 30, 60, and 90-day intervals

- Calculate nutrient budgets and use efficiency indices

Expected Outcomes: This protocol has demonstrated yield increases of 8-150% compared to conventional practices while improving soil organic matter and microbial activity [13].

Conservation Agriculture Implementation

Objective: Mitigate physical degradation and build resilient soil structure.

Experimental Workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Soil Health Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Moisture Sensors | Continuous monitoring of soil water dynamics | Install at multiple depths (15, 30, 60 cm); calibrate to soil type; integrate with data logging systems [14] |

| Portable Soil Test Kits | Rapid in-field assessment of pH, nitrate, EC | Fresh soil sampling; proper extraction ratios; calibration before each use [9] |

| Microbial Biomass Assay Kits | Quantification of active soil microbial populations | Chloroform fumigation extraction; follow standardized incubation protocols [9] |

| Soil Respiration Chambers | Measurement of microbial activity via CO₂ evolution | Field deployment with temperature control; minimum 24-hour measurement cycles [10] |

| Remote Sensing/Satellite Data | Landscape-scale monitoring of vegetation and soil indices | Access via APIs (e.g., Farmonaut); validate with ground-truthing; multi-spectral analysis [14] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Tracking nutrient pathways and carbon sequestration | Precise application rates; careful sampling timing; mass spectrometry analysis [13] |

| Soil Aggregate Stability Kits | Assessment of soil physical structure | Wet-sieving methodology; controlled water flow rates; replicate sampling [9] |

Advanced Research Considerations

Climate Resilience Integration

Research Priority: Developing climate-resilient nutrient management strategies that account for elevated CO₂, temperature increases, and erratic precipitation patterns.

Experimental Design Elements:

- Temperature manipulation studies to simulate warming scenarios

- Drought stress protocols with controlled irrigation withholding

- CO₂ enrichment experiments to study nutrient dynamics under elevated carbon dioxide

- Extreme precipitation simulation to assess nutrient leaching risks [11]

Emerging Solutions for Degraded Systems

Biochar Applications:

- Improves water retention in degraded soils

- Enhances nutrient retention and reduces leaching

- Provides habitat for microbial communities

- Application rates: 5-20 t ha⁻¹ depending on soil texture and degradation severity [13]

Neglected and Underutilized Crops (NUCs):

- Incorporate climate-resilient traditional crops into rotation systems

- Enhance system biodiversity and nutritional diversity

- Provide genetic resources for breeding programs

- Examples: millets, sorghum, traditional legumes [15]

Micronutrient deficiencies, often termed "hidden hunger," represent a critical global health challenge where individuals consume adequate calories but lack essential vitamins and minerals. This condition affects billions worldwide, compromising immune function, cognitive development, and economic productivity.

Global Scope: Recent research indicates that more than half of the global population consumes inadequate levels of several micronutrients essential to health, including calcium, iron, and vitamins C and E [16]. This widespread deficiency carries severe health consequences, from adverse pregnancy outcomes to increased susceptibility to infectious diseases.

Economic Impact: The economic costs of undernutrition are significant, estimated at least $1 trillion annually due to productivity losses from undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. An additional $2 trillion per year is lost due to overweight and obesity, creating a complex double burden of malnutrition [17].

Quantitative Analysis of Global Micronutrient Deficiencies

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Inadequate Micronutrient Intake [16]

| Micronutrient | Global Population with Inadequate Intake |

|---|---|

| Iodine | 68% |

| Vitamin E | 67% |

| Calcium | 66% |

| Iron | 65% |

| Riboflavin | >50% |

| Folate | >50% |

| Vitamin C | >50% |

| Vitamin B6 | >50% |

| Niacin | 22% |

| Thiamin | 30% |

| Selenium | 37% |

Table 2: Health Consequences of Key Micronutrient Deficiencies [18]

| Micronutrient | Health Consequences |

|---|---|

| Iron | Anaemia, fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, dizziness; affects 40% of pregnant women globally |

| Iodine | Brain damage, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, congenital anomalies, mental impairment |

| Vitamin A | Leading cause of preventable childhood blindness, increased risk of severe infections |

| Multiple | Compromised immune function, cognitive impairments, reduced work capacity |

Table 3: Regional Disparities in Nutritional Deficiencies [19] [17]

| Region/Country | Key Nutritional Issues |

|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | High stunting rates, increasing number of stunted children |

| South Asia | High stunting rates, significant micronutrient deficiencies |

| Low SDI Countries | Greater burden of diseases from nutritional deficiencies |

| Botswana | 32.5% iron deficiency in women, 8.7% vitamin A deficiency in children (1994 survey) [20] |

The Research Challenge: Nutrient Depletion in High-Yielding Crops

Historical Decline in Crop Nutritional Value

Research has revealed an alarming decline in food quality over the past sixty years, with decreases in essential minerals and nutraceutical compounds in fruits, vegetables, and food crops [3]. Key findings include:

- Significant Reductions: Studies show calcium content declined 16%, iron by 15%, and phosphorus by 9% on average across 43 vegetables analyzed since 1950 [3] [2].

- Specific Examples: Between 1940-1991, vegetables showed dramatic losses of copper (76%) and zinc (59%) [3].

- Dilution Effect: High-yielding varieties developed during the Green Revolution often prioritize carbohydrate production over nutrient density, resulting in a higher ratio of carbohydrates to nutrients [2].

Root Causes in Agricultural Systems

- Soil Health Degradation: Intensive farming practices have disrupted the fine balance of soil life, decreasing nutritional density of food crops [3].

- Genetic Selection: Modern crop varieties have been selected for yield, pest resistance, and growth rate rather than nutritional content [3] [2].

- Fertilizer Imbalances: Chaotic mineral nutrient application and a shift from natural to chemical farming have contributed to nutrient imbalances [3].

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I accurately assess nutrient deficiency impacts in crop research?

Answer: Implement controlled nutrient deficiency experiments with proper experimental design:

Experimental Workflow for Nutrient Deficiency Studies [21]

Methodology Details:

- Use randomized complete block design with 3-5 replications [21]

- Establish clear treatment groups: NP (K deficiency), NK (P deficiency), PK (N deficiency), NPK (adequate), CK (no fertilizer) [21]

- Measure yield, dry matter accumulation, plant nutrient concentration, and soil nutrient changes [21]

- Calculate nutrient use efficiency indices including Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) and Nitrogen Harvest Index (NHI) [21]

FAQ 2: What are effective strategies to enhance micronutrient density in crops?

Answer: Multiple biofortification approaches have shown success:

Biofortification Strategy Pathways [22] [2]

Experimental Protocols:

Soil Microbe Inoculation Protocol:

- Source: Isolate mycorrhizal fungi from resilient environments (e.g., desert soils) [2]

- Application: Coat seeds or roots with inoculant powder before planting [2]

- Measurements: Track nutrient uptake efficiency, plant growth metrics, and yield comparisons [2]

Genetic Biofortification Workflow:

- Identify target nutrient pathways and genes [22]

- Use CRISPR-Cas9 for precise genome editing [22]

- Develop biofortified lines of staple crops (rice, wheat, maize, beans) [22]

- Conduct nutritional analysis and feeding trials to validate health impacts [22]

FAQ 3: How do I address soil health to improve nutrient density in crops?

Answer: Focus on rebuilding soil biodiversity and fertility:

Regenerative Soil Management Protocol:

- Implement comparative trials: conventional vs. regenerative organic practices [2]

- Monitor soil microbial diversity, particularly mycorrhizal fungi populations [2]

- Analyze correlation between soil health metrics and crop nutrient density [2]

- Utilize cover crops and diverse rotations to enhance soil organic matter [3]

Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- Poor Nutrient Availability: Despite adequate soil nutrients, add soil inoculants to enhance bioavailability [2]

- Yield-Nutrient Tradeoffs: Select cultivars that balance yield with nutrient density rather than maximizing yield alone [3]

- Nutrient Imbalances: Conduct soil testing and implement balanced fertilization based on crop requirements [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Nutrient Deficiency Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Inoculants (Mycorrhizal) | Enhance nutrient uptake via extended root system | Isolate from resilient environments; coat seeds or roots [2] |

| H2SO4-H2O2 Digestion Mixture | Plant tissue digestion for nutrient analysis | Use in automatic Kjeldahl nitrogen analyzer [21] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genome editing for biofortification | Target nutrient pathway genes in staple crops [22] |

| NPK Fertilizers | Controlled nutrient deficiency studies | Formulate specific deficiency treatments (NP, NK, PK) [21] |

| Brachiaria Grass | High-nutrient forage research | Massive root system sequesters carbon, draws deep nutrients [2] |

| Isotopic Tracers | Track nutrient uptake and mobilization | Quantify nutrient use efficiency parameters [21] |

Addressing micronutrient deficiencies requires multidisciplinary approaches that bridge agriculture, nutrition, and public health. Research priorities should include:

- Developing integrated strategies that combine biofortification with soil health management

- Establishing improved monitoring systems for tracking nutrient density in food systems

- Creating economic incentives for producing nutrient-dense crops rather than focusing solely on yield

- Validating the health impacts of biofortified crops through controlled feeding studies

The devastating health impacts and economic consequences of micronutrient deficiencies underscore the urgent need for research that addresses nutrient depletion in modern crop varieties. Through targeted experimental approaches and innovative solutions, researchers can contribute to reversing this trend and improving global health outcomes.

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists investigating the decline in the nutritional density of modern crops, a phenomenon increasingly linked to the erosion of agricultural biodiversity. The replacement of diverse, nutrient-rich indigenous crops with a limited number of high-yielding varieties (HYVs) has raised significant concerns for global nutrition and food security [23] [3]. The content here provides troubleshooting guidance and methodological support for experiments aimed at diagnosing and addressing nutrient depletion in contemporary agricultural systems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Low Nutritional Density in Crop Varieties

Problem: Analysis shows significantly lower concentrations of target micronutrients (e.g., iron, zinc, vitamins) in a high-yielding crop variety compared to historical data or indigenous landrace controls.

Steps:

Verify the Result

- Repeat the experiment: Ensure the finding is reproducible and not due to a one-off error in protocol execution [24].

- Check your controls: Confirm that the positive control (e.g., a known nutrient-dense variety) shows the expected high nutrient levels. A negative control helps rule out contamination [24].

Inspect Materials and Equipment

- Reagent integrity: Verify that all chemicals and standards for nutrient analysis have been stored correctly and have not degraded [24].

- Equipment calibration: Ensure that analytical instruments (e.g., spectrometers, chromatographs) are properly calibrated and functioning within specified parameters [25].

Investigate Agronomic and Genetic Variables

- Soil analysis: Test the soil for its native nutrient content and pH, as soil depletion is a primary cause of nutrient dilution in food [3] [6].

- Cultivar verification: Confirm the genetic identity of the seeds used. High-yielding varieties are often bred for size and growth rate, not nutrient uptake, which can lead to a "dilution effect" [26] [3].

- Review growing conditions: Variables like water stress, light levels, and synthetic fertilizer use can impact nutrient expression [3].

Systematically Change Variables

- Modify one variable at a time to isolate the cause [24]. Key variables to test include:

- Soil fertility: Compare nutrient levels in crops grown in depleted soil versus soil amended with organic matter or a balanced mix of minerals [3].

- Cultivar selection: Grow indigenous and high-yielding varieties side-by-side in the same soil and conditions to directly compare their nutrient profiles [23].

- Modify one variable at a time to isolate the cause [24]. Key variables to test include:

Document Everything

- Meticulously record all changes, results, and observations in a lab notebook for future reference and reproducibility [24].

Guide 2: Reviving Nutrient Profiles in Modern Cropping Systems

Problem: A research plot aimed at enhancing nutrient density is failing to show improvement, despite interventions.

Steps:

Assess the Experimental Setup

- Confirm the hypothesis: Revisit the scientific literature. Is the lack of improvement due to a flawed protocol, or could it be explained by other biological or environmental factors? [24]

- Evaluate biodiversity interventions: If the intervention involves reintroducing indigenous crops, check for germination rates, seed viability, and appropriate agronomic practices for that specific variety [23].

Check Soil Biodiversity and Health

- Test for microbial life: Introduce soil analysis for beneficial microbes. Inoculating soil with mycorrhizal fungi or other biofertilizers can enhance nutrient uptake [3] [6].

- Move away from chaotic mineral application: Ensure a balanced and adequate nutrient application plan is in place, as over-reliance on synthetic NPK fertilizers can disrupt soil life and reduce the nutritional quality of food [3].

Implement and Monitor Corrective Strategies

- Utilize tissue testing: This complements soil testing by showing the actual nutrient status of the crop plants at different growth stages, allowing for precise adjustments [6].

- Incorporate organic amendments: Shift from chemical farming to integrating compost, manure, and other organic fertilizers to improve soil biodiversity and fertility [3] [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core link between biodiversity and the nutrient density of our food? A1: The systematic replacement of thousands of locally adapted, nutrient-rich indigenous crops with a handful of high-yielding varieties has led to less diverse and often less nutritious diets [23] [3]. For example, just nine crops now account for two-thirds of global production, and many of these HYVs are optimized for yield and pest resistance rather than nutritional content, leading to a documented decline in vitamins and minerals [26] [23].

Q2: What quantitative evidence exists for the decline of nutrients in fruits and vegetables? A2: Multiple studies across different countries have shown reliable declines in essential nutrients over the past 50-80 years. The table below summarizes key findings:

Table 1: Documented Declines in Nutrient Content of Fruits and Vegetables

| Time Period | Calcium | Iron | Vitamin A | Vitamin C | Other Nutrients | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 - 1999 (43 crops, USA) | -16% | -15% | -18% | -15% | Protein (-6%), Phosphorus (-9%), Riboflavin (-38%) | [26] |

| 1936 - 1991 (20 veggies, UK) | -19% | -22% | Not Studied | Not Studied | Magnesium (-35%), Copper (-81%) | [26] [3] |

| 1975 - 1997 (12 veggies, USA) | -27% | -37% | -21% | -30% | [26] | |

| 1975 - 1997 (Fruits, USA) | e.g., Lemons: -57% | e.g., Bananas: -56% | e.g., Apples: -41% | e.g., Oranges: -30% | [3] |

Q3: How did the Green Revolution contribute to this problem? A3: The Green Revolution introduced high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of wheat and rice that dramatically increased caloric output. However, this success came with trade-offs:

- Genetic Erosion: Widespread adoption of HYVs led to the abandonment of countless local, nutrient-dense landraces and cultivars [23] [27].

- Soil Depletion: The intensive use of irrigation and synthetic fertilizers, while boosting yield, often degraded soil health and biodiversity, reducing the soil's ability to support nutrient-dense crops [3] [27].

- The Dilution Effect: HYVs are often selected for fast growth and high yield, which can dilute the concentration of minerals and vitamins in the harvested food [26].

Q4: What are the best management strategies to enhance nutritional quality in food crops? A4: Research points to several key strategies:

- Improve Soil Biodiversity: Shift from chemical-intensive farming to practices that build soil organic matter and support microbial life, such as using compost, manure, and biofertilizers [3].

- Revive Traditional Crops: Actively cultivate and integrate indigenous crops like millets, sorghum, and heirloom vegetables, which are often more nutrient-dense and climate-resilient [23] [3].

- Implement Balanced Nutrition: Move away from chaotic mineral application to a balanced and adequate nutrient management plan based on regular soil and tissue testing [3] [6].

Q5: My research involves analyzing nutrient levels in plant tissues. What are the standard protocols for this? A5: Two complementary techniques are essential:

- Soil Testing: Involves collecting samples from various depths and locations across a field. Analysis includes pH, electrical conductivity, organic matter content, and available nutrients (N, P, K, etc.) to inform fertilization strategies [6].

- Tissue Testing: Plant tissues are sampled at critical growth stages and analyzed for the concentration of essential nutrients. This detects deficiencies or toxicities directly in the plant, allowing for precise adjustments to nutrient management plans [6].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Comparative Analysis of Nutrient Density in Crop Varieties

Objective: To quantitatively compare the micronutrient content of an indigenous crop landrace against a modern high-yielding variety.

Materials:

- Seeds of indigenous landrace and modern HYV.

- Standardized potting soil or access to controlled field plots.

- Equipment for nutrient analysis (e.g., ICP-MS for minerals, HPLC for vitamins).

- Lab equipment for sample preparation (oven, grinder, analytical balance).

Methodology:

- Growth Conditions: Grow both crop varieties in the same controlled environment (greenhouse) or randomized field plots to eliminate environmental variation.

- Sample Collection: Harvest edible portions (e.g., grains, fruits) at identical maturity stages. Prepare triplicate samples for each variety.

- Sample Preparation: Dry samples to constant weight in an oven and grind to a fine, homogeneous powder.

- Nutrient Extraction: Perform standardized chemical extractions for target minerals (e.g., using acid digestion for Fe, Zn) or vitamins (e.g., solvent extraction for Vitamins A, C).

- Analysis: Run samples through appropriate analytical equipment alongside known calibration standards.

- Data Analysis: Statistically compare the mean nutrient concentrations between the two varieties.

The following workflow diagrams the logical sequence of this comparative experiment.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Soil Amendments on Nutrient Density

Objective: To determine if reintroducing organic amendments and biofertilizers can improve the nutrient profile of a crop grown in depleted soil.

Materials:

- Seeds of a test crop.

- Depleted soil sample.

- Organic compost or manure.

- Commercial mycorrhizal inoculant (biofertilizer).

- Pots or designated field plots.

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Set up three treatments:

- Control: Depleted soil only.

- Treatment A: Depleted soil + organic compost.

- Treatment B: Depleted soil + organic compost + biofertilizer.

- Plant Growth: Sow seeds and grow plants to maturity under standardized conditions.

- Soil & Tissue Sampling: Collect soil samples at the beginning and end of the experiment. Harvest plant tissue at maturity.

- Analysis: Perform soil tests (pH, organic matter, available nutrients) and tissue tests (mineral content) for all samples.

- Data Analysis: Correlate changes in soil health with changes in plant tissue nutrient density across the three treatments.

The logical relationship and decision points in this soil intervention experiment are shown below.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Investigating Crop Nutrient Density

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Seed Varieties | Serve as genetic benchmarks for optimal nutrient density. | Comparing mineral content of traditional desi bhutta corn against modern sweet corn [23]. |

| Soil Testing Kit | Assesses baseline soil fertility, pH, and organic matter. | Diagnosing if soil depletion is the primary cause of low nutrient levels in a test crop [6]. |

| Tissue Testing Kits | Measures the actual concentration of nutrients absorbed by the plant. | Verifying if a soil intervention has successfully increased the iron levels in lettuce leaves [6]. |

| Organic Amendments (Compost/Manure) | Rebuilds soil organic matter and supports a diverse soil microbiome. | Amending degraded soils to restore natural nutrient cycling and improve plant health [3]. |

| Biofertilizers / Mycorrhizal Inoculants | Forms symbiotic relationships with plant roots, enhancing water and nutrient uptake (e.g., phosphorus). | Inoculating seeds or soil to improve the efficiency of nutrient absorption from the soil [3] [6]. |

| Reference Standards (e.g., Fe, Zn) | Calibrates analytical equipment for accurate quantification of minerals. | Ensuring the precision and accuracy of ICP-MS or AAS readings when analyzing plant tissue samples. |

Analyzing Historical Nutrient Composition Shifts in Staple Crops

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Unexpected Nutrient Profile Results in Plant Tissue Analysis

Problem: Laboratory analysis of modern crop varieties shows significantly lower mineral concentrations than historical data indicates, despite adequate soil fertilization.

Explanation: This is a documented phenomenon, not necessarily an experimental error. Research confirms that over the past 50-70 years, many fruits, vegetables, and staple crops have experienced a significant decline in nutrient density [28] [3]. The dilution of soil nutrients and a shift toward high-yielding varieties are primary causes.

Solution:

- Recalibrate Your Baseline: Use the most recent nutrient sufficiency ranges, as they have been updated for modern high-yield varieties. For example, research for maximum-yield corn shows sufficiency ranges for Nitrogen (N) and Potassium (K) during vegetative stages are now substantially higher than previously published ranges [29].

- Cross-Reference with Soil Health: Perform a comprehensive soil test to assess soil organic matter and microbial biodiversity. Nutrient decline is closely linked to soil degradation [28] [30].

- Account for the "Genetic Dilution Effect": High-yielding varieties often allocate more energy to rapid growth and carbohydrate production, which can dilute the concentration of minerals and proteins, even when total nutrient uptake per acre may be higher [3].

Guide 2: Addressing Inconsistencies in Replicating Historical Nutritional Studies

Problem: Your attempts to replicate the nutritional findings of studies from the 1970s-1990s fail, yielding inconsistent data on vitamin and mineral content.

Explanation: The baseline nutritional content of the crop cultivars themselves has changed. Using modern seeds to replicate studies conducted with older cultivars will inherently produce different results.

Solution:

- Source Heirloom Varieties: For controlled comparison, procure seeds for traditional or heirloom crop varieties (e.g., ancient grains like millet or sorghum, traditional rice strains) from gene banks or specialty suppliers. Studies show these often have superior nutritional profiles [28] [23].

- Control for Atmospheric CO₂: If your experimental setup allows, control for CO₂ levels. Elevated CO₂ can significantly reduce the concentrations of essential nutrients like zinc, iron, and protein in crops [3].

- Verify Analytical Methods: Ensure your laboratory's analytical techniques (e.g., ICP-MS for minerals, HPLC for vitamins) are calibrated against certified reference materials that are contemporaneous with your research goals to rule out methodological discrepancies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the strongest scientific evidence for the decline of nutrients in staple crops? A1: Multiple peer-reviewed studies and meta-analyses have quantified this decline. For instance, data shows that between 1975 and 1997, broccoli experienced a 53.4% decrease in calcium, a 20% decrease in iron, and a 38.3% decrease in Vitamin A [28]. A comprehensive review in Heliyon further confirms that popular fruits and vegetables have lost 25-50% of their nutrient density over the past 50-70 years [28] [3].

Q2: Beyond soil health, what are the primary drivers of this nutrient decline? A2: The causes are multi-factorial and include:

- Genetic Dilution: Breeding for higher yield and faster growth often prioritizes carbohydrate accumulation over nutrient density [3].

- Soil Degradation: Intensive farming depletes soil organic matter and microbial ecosystems crucial for nutrient cycling [28] [30].

- Atmospheric Changes: Elevated CO₂ levels can reduce the concentration of essential minerals in plant tissues [3].

- Loss of Biodiversity: The global shift toward a few high-yield crops has replaced diverse, nutrient-rich traditional varieties [23].

Q3: How can I accurately monitor nutrient levels in my experimental crops? A3: Standardized plant analysis is the correct tool.

- Procedure: The process involves four key steps: 1) Sampling a specific plant part (e.g., ear leaf of corn at silking) at a defined growth stage; 2) Sample preparation (cleaning, drying, grinding); 3) Laboratory analysis for quantitative determination of elements; and 4) Interpretation against established sufficiency ranges [31] [32].

- Critical Consideration: Always sample from both "problem" and "normal" areas for comparison, and follow strict protocols to avoid sample contamination or deterioration [32].

Q4: What are the most promising research solutions to reverse nutrient depletion in crops? A4: Current research focuses on several strategies:

- Biofortification: Using conventional breeding or genetic engineering (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) to develop staple crops with elevated levels of vital micronutrients like iron, zinc, and vitamin A. Examples include Golden Rice and high-iron beans [22].

- Reviving Traditional Crops: Re-introducing nutrient-dense ancient grains like millet, sorghum, and teff, which are often richer in protein, minerals, and phytochemicals than modern wheat and rice [28] [23].

- Regenerative Agricultural Practices: Focusing on farming methods that rebuild soil organic matter and restore soil biodiversity, which in turn enhances the nutrient density of food [30].

Quantitative Data on Nutrient Decline

Table 1: Documented Nutrient Decline in Selected Crops (1975-1997)

| Crop | Nutrient | Percentage Decline | Time Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broccoli | Calcium | 53.4% | 1975 - 1997 | [28] |

| Iron | 20.0% | 1975 - 1997 | [28] | |

| Vitamin A | 38.3% | 1975 - 1997 | [28] | |

| Fruits (Aggregate) | Calcium | 57.4% - 65.0% | 1975 - 2001 | Lemons, pineapples, tangerines [3] |

| Iron | 55.7% - 85.0% | 1975 - 2001 | Bananas, grapefruit, oranges [3] | |

| Vitamin A | 38.0% - 87.5% | 1975 - 2001 | Bananas, grapefruit, apples [3] |

Table 2: Updated Nutrient Sufficiency Ranges for Maximum Yield Corn

| Nutrient | Growth Stage V5 | Growth Stage V12 | Growth Stage R1 (Silking) | Note vs. Historical Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N) | 4.50 - 5.50% | 4.25 - 5.25% | 3.50 - 4.25% | Substantially higher [29] |

| Potassium (K) | 4.25 - 5.50% | 3.75 - 5.00% | 2.50 - 3.50% | Substantially higher [29] |

| Phosphorus (P) | 0.40 - 0.70% | 0.35 - 0.60% | 0.28 - 0.50% | Range narrows at low end [29] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standardized Plant Tissue Analysis for Nutrient Profiling

Application: Diagnosis of nutrient status, prediction of nutrient response, and monitoring of nutrient levels in experimental crops [31].

Materials:

- Clean paper bags or envelopes

- Forced-air drying oven

- Stainless steel grinding mill

- Plant analysis submission forms

Methodology:

- Sampling:

- Identify the correct plant part and growth stage for your crop (e.g., for corn, the ear leaf at silking is standard) [32].

- Collect tissue from 15-20 representative plants in the experimental area.

- If diagnosing a problem, collect paired samples from both "good" and "bad" areas for comparison.

- Sample Preparation:

- Gently brush off any soil or dust. Avoid washing, as it can leach nutrients.

- Place samples in a paper bag and dry immediately in an oven at 60°C (140°F) to halt enzymatic activity.

- Grind the dried tissue in a stainless steel mill to a uniform particle size for homogeneous sub-sampling.

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Submit the prepared sample to an accredited laboratory for quantitative analysis, typically using methods like Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) for minerals.

- Data Interpretation:

Plant Tissue Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of Modern vs. Traditional Varieties

Application: Directly quantifying the genetic contribution to nutrient decline by controlling for environmental factors.

Materials:

- Seeds of modern high-yield variety

- Seeds of traditional/heirloom variety

- Controlled environment growth chambers or uniform field plots

Methodology:

- Experimental Design:

- Grow modern and traditional crop varieties side-by-side under identical soil, water, and climatic conditions in a randomized complete block design.

- Sampling and Analysis:

- At a defined physiological maturity stage, collect plant tissue samples from both varieties following Protocol 1.

- Analyze for target micronutrients (e.g., Fe, Zn, Ca), macronutrients, and phytochemicals.

- Data Analysis:

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., t-test) to determine significant differences in nutrient concentration between the two varieties, indicating a genetic component to nutrient density.

Genetic vs. Environmental Impact Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nutrient Composition Research

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibrate laboratory equipment and validate the accuracy of nutrient concentration measurements for reliable, reproducible data. |

| Heirloom/Traditional Seeds | Serve as a genetic baseline for comparative studies against modern high-yielding varieties to quantify nutrient decline [28] [23]. |

| ICP-OES/MS Standards | Essential for the quantitative determination of mineral and trace element concentrations in digested plant tissue samples. |

| Soil Test Kits | For concurrent analysis of soil nutrient availability and pH, allowing researchers to correlate plant tissue nutrient levels with soil conditions [32]. |

| RNA/DNA Extraction Kits | Used in molecular studies to analyze gene expression related to nutrient uptake and assimilation, particularly in biofortification research [22]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Enable precise genome editing for biofortification projects, aiming to enhance the nutrient profile of staple crops [22]. |

Innovative Approaches for Enhancing Crop Nutritional Profiles

Speed Breeding Protocols for Rapid Development of Nutrient-Dense Varieties

Modern high-yielding crop varieties have successfully addressed global calorie needs but often at the cost of nutritional density. Research indicates that the mineral content of fruits and vegetables has declined significantly since the 1950s, with studies showing reductions of up to 38% in essential nutrients like calcium, iron, and phosphorus [3] [2]. This nutritional dilution effect stems from multiple factors, including soil depletion and breeding priorities that favored yield and appearance over nutritional quality [33] [2].

Speed breeding emerges as a powerful solution to this challenge by dramatically accelerating the development of more nutritious varieties. This technique uses controlled environmental conditions to reduce generation times, allowing breeders to incorporate enhanced nutritional traits into elite genetic backgrounds much faster than conventional methods permit [34] [35] [36]. While speed breeding itself doesn't create new traits, it significantly expedites the process of stacking beneficial nutritional alleles through marker-assisted selection and other modern breeding tools [37] [35].

Table 1: Comparison of Breeding Approaches for Nutrient-Dense Varieties

| Breeding Aspect | Conventional Breeding | Speed Breeding |

|---|---|---|

| Generations per year | 1-2 generations [35] | 4-6 generations for wheat/barley; 4-5 for rice [34] [35] [36] |

| Time for new variety | 8-12 years [35] | Significantly reduced (up to 60% time savings) [37] |

| Nutritional quality focus | Limited by long cycles | Enables rapid stacking of nutritional traits |

| Trait integration | Slow combination of traits | Rapid pyramiding through marker-assisted selection [36] |

Theoretical Foundations: How Speed Breeding Addresses Nutrient Density

Speed breeding accelerates plant development by manipulating key environmental factors that regulate growth cycles, primarily through extended photoperiods, optimized temperatures, and precise nutrient management [34] [37] [36]. The approach is grounded in plant physiology principles, particularly photoperiodism—the physiological reaction of plants to day length—which directly influences flowering time and generation turnover [34].

For nutrient-density breeding, speed breeding protocols create conditions that allow researchers to more rapidly identify and select lines with superior nutritional profiles. The accelerated growth cycles enable faster incorporation of nutritional traits from wild relatives or landraces into high-yielding commercial varieties [35]. Research indicates that different crop varieties vary significantly in their nutrient accumulation, with some varieties having twice the nutrient content of others within the same species [33]. Speed breeding makes the process of identifying and fixing these superior nutritional traits in breeding lines significantly more efficient.

Speed Breeding Methodology: Protocols for Nutrient-Dense Variety Development

Core Environmental Parameters

Successful speed breeding protocols require precise control of environmental conditions. The following parameters have been optimized across multiple crop species:

- Photoperiod: 22 hours light/2 hours dark for long-day plants; adjustable for short-day species [34] [38]

- Light Intensity: 400-600 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation) [34]

- Light Spectrum: Full-spectrum LED with enhanced blue and red wavelengths [34]

- Temperature: 22°C ± 3°C day/17°C night [34] [38]

- Relative Humidity: 60-70% [34] [38]

- CO₂ Concentration: 400-450 ppm [34]

Growth Media and Nutrition Management

Proper nutrition management is particularly critical when breeding for nutrient-dense varieties, as mineral uptake and partitioning are key traits under selection:

- Soil Mixture: 70% peat moss, 20% vermiculite, 10% perlite, pH 6.0-6.5 [34]

- Nutrient Solution: Modified Hoagland's solution with EC 1.5-2.0 mS/cm [34]

- Fertilizer Application: Research on durum wheat found optimal productivity with 20-20-0 composite fertilizer in 100% peat soil [38]

- Foliar Feeding: Application during tillering and stem elongation-heading stages showed benefits [38]

Table 2: Speed Breeding Generation Advances for Major Crops

| Crop Type | Species | Generations/Year with Speed Breeding | Key Nutritional Traits Targeted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | 4-6 [36] | Iron, zinc, protein content [35] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | 4-5 [35] [36] | Iron, zinc, vitamin A [35] | |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | ~6 [36] | Beta-glucans, protein quality | |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Not specified | Vitamin A, quality protein [35] | |

| Legumes | Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) | ~6 [36] | Iron, zinc, protein |

| Soybean (Glycine max) | ~5 [36] | Protein, oil quality | |

| Lentil (Lens culinaris) | ~8 [36] | Iron, folate | |

| Oilseeds | Rapeseed (Brassica napus) | ~5 [36] | Oil composition, antioxidants |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing successful speed breeding programs for nutrient-dense varieties requires specific reagents and equipment. The following table details essential materials and their functions:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Speed Breeding

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Full-Spectrum LED Lights | Provides optimal light spectrum for photosynthesis and flowering | Include enhanced blue and red wavelengths; 400-600 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ intensity [34] |

| Controlled Environment Chambers | Maintains precise temperature, humidity, and light cycles | Requires 22°C day/17°C night temperature, 60-70% humidity [34] [38] |

| Peat-Based Growth Medium | Provides optimal root growth and nutrient retention | 70% peat moss, 20% vermiculite, 10% perlite recommended [34] |

| Modified Hoagland's Solution | Balanced nutrient supply for accelerated growth | EC 1.5-2.0 mS/cm; daily fertigation [34] |

| Molecular Markers | Selection of nutritional quality traits | Enables marker-assisted selection for nutrient-density genes [35] [36] |

| Beneficial Microorganisms | Enhance nutrient uptake and plant health | Mycorrhizal fungi and PGPR improve nutrient acquisition [39] |

| Refractometers/Spectrophotometers | Rapid assessment of nutrient-related compounds | Measure soluble solids (Brix) as proxy for some nutrients [40] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Speed Breeding Challenges

FAQ: Technical and Methodological Issues

Q: What is the optimal pot size for speed breeding systems to ensure normal seed set? A: Research on durum wheat indicates that larger pot volumes (270 cm³) yield the highest productivity under speed breeding conditions. Smaller cell trays (32-130 cm³) result in reduced growth and seed production due to root restriction [38].

Q: How can I prevent nutrient deficiencies in speed breeding systems with accelerated growth? A: The rapid growth in speed breeding depletes nutrients quickly. Recommended solutions include: (1) Applying nutrients every 1-2 weeks based on pot size and soil type; (2) Using foliar fertilizers to address deficiencies quickly; (3) Ensuring complete nutrient solutions with all essential micronutrients [38].

Q: What are the solutions for poor seed set under speed breeding conditions? A: Poor seed set can be addressed by: (1) Increasing air circulation to promote pollen dispersal; (2) Adjusting temperature during flowering (species-specific optimization); (3) Implementing manual pollination for critical crosses; (4) Ensuring adequate plant spacing to reduce competition stress [34].

Q: How can I manage high electricity costs associated with speed breeding? A: Energy consumption is a significant challenge. Solutions include: (1) Exploring solar power integration; (2) Using energy-efficient LED lighting; (3) Implementing automated climate control to optimize energy use; (4) Considering cost-effective SB III systems for smaller-scale operations [35].

Q: Are speed-bred plants genetically modified, and are there regulatory concerns? A: No, speed breeding does not involve genetic modification. It simply accelerates plant development through environmental control. No external genetic material is introduced, so speed-bred plants are not considered GMOs and face no additional regulatory barriers in most countries, including India [37] [35].

Advanced Integration: Microbial Enhancement and Stress Management

Emerging research suggests that incorporating beneficial microorganisms can enhance speed breeding efficiency. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria and mycorrhizal fungi can improve nutrient uptake—a critical factor when selecting for nutrient-dense varieties [39]. These microorganisms potentially enhance plant resilience to the stresses induced by accelerated growth conditions, including oxidative stress from prolonged light exposure [39].

Speed breeding represents a paradigm shift in developing nutrient-dense crop varieties with the potential to significantly reduce the time between nutritional trait discovery and variety release. As this technology evolves, integration with emerging approaches like CRISPR gene editing, genomic selection, and AI-driven phenotyping will further accelerate the development of crops that address both calorie needs and micronutrient malnutrition [35] [36].

The successful application of speed breeding to diverse crops—from staples like wheat and rice to nutrient-dense legumes and vegetables—heralds a new era in nutritional breeding. By implementing the protocols, troubleshooting guides, and reagent solutions outlined in this technical support center, researchers can contribute to reversing the trend of nutrient decline in our food system while responding rapidly to evolving climate challenges [34] [35] [36].

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind the 4R Nutrient Stewardship framework? The 4R framework is a cornerstone of SMART Nutrient Management, advocating for the application of nutrients from the Right Source, at the Right Rate, at the Right Time, and in the Right Placement [41]. This approach is designed to optimize nutrient uptake by crops, thereby maximizing yield while minimizing environmental losses that can impact air and water quality [41].

Q2: Our research aims to counter the widespread decline in food nutrient density. How can precision agriculture technologies help? Historical studies show alarming declines in the mineral and vitamin content of fruits and vegetables over the past several decades [3]. Precision agriculture technologies (PATs), such as Variable Rate Technology (VRT) and in-ground sensors, are key to addressing this. They enable the precise application of fertilizers based on real-time, site-specific data on soil nutrient levels and crop needs [42]. This ensures crops receive optimal nutrition, which is fundamental to improving their nutritional quality and density.

Q3: What are common challenges when establishing nutrient sufficiency ranges for high-yielding varieties, and how can we troubleshoot them? Recent research on high-yield corn and soybeans has revealed that traditional nutrient sufficiency ranges can be suboptimal, sometimes even deleterious to yield [29]. Troubleshooting this requires:

- Luxury Feeding Identification: Monitor for nutrient levels that exceed the optimal range for yield, indicating luxury consumption that does not increase production [29].

- Nutrient Antagonism: Investigate potential competitive uptake between nutrients, such as copper (Cu) and manganese (Mn). High tissue levels of one may require management changes, like proper placement, to ensure availability of the other [29].

- Tissue Testing at Critical Stages: Establish and use growth-stage-specific sufficiency ranges derived from high-yield environments rather than relying on generalized historical data [29].

Q4: We are experiencing inconsistent data from soil and plant tissue sensors. What could be the cause? Inconsistent data can stem from several issues:

- Lack of Calibration: Ensure sensors are regularly calibrated according to manufacturer specifications.

- Data Interoperability: The absence of uniform data standards can hamper interoperability between different devices and platforms, leading to inconsistent readings [43].

- Spatial Variability: A single sensor reading may not represent field-scale variability. Employ a dense network of sensors or use remote sensing from drones to provide broader context and validate point measurements [42] [43].

Q5: How can we manage the high volume of data generated by precision nutrient management systems? The vast amount of data from yield monitors, soil sensors, and drones is a common challenge.

- Use Data Analytics: Support the development of software that utilizes artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to analyze data and translate it into actionable decisions [43].

- Data Sharing Frameworks: Utilize easy-to-understand data license agreements and codes of conduct to enable better flow and management of data while addressing ownership concerns [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Yield monitor shows lower-than-expected yields despite adequate nutrient application.

- Potential Cause 1: Nutrient Antagonism. High levels of one nutrient may be inhibiting the uptake of another [29].

- Solution: Conduct detailed plant tissue analysis to identify imbalances. Adjust nutrient management to address specific deficiencies or antagonisms, potentially by altering the source or placement of fertilizers.

- Potential Cause 2: Inaccurate Nutrient Sufficiency Ranges. Using generalized nutrient ranges that are not calibrated for your specific high-yielding variety [29].

- Solution: Consult the latest research to establish tissue sufficiency ranges specific to your crop and yield goals. Refer to updated tables for high-yield corn and soybeans as a starting point [29].

Problem: Variable Rate Technology (VRT) system is not producing the expected economic or environmental benefits.

- Potential Cause 1: Inaccurate Application Maps. The underlying data for the VRT map does not accurately reflect field variability.

- Solution: Improve data collection by integrating multiple sources. Use high-resolution satellite or drone imagery to refine soil nutrient maps and validate with ground-truthed soil sampling [42].

- Potential Cause 2: Equipment Inefficiency. Overlaps or gaps during application due to improper equipment calibration or guidance [44].

- Solution: Implement a tractor-guidance system (autosteer) with GPS to achieve accuracy within one centimeter, drastically reducing overlaps and gaps during planting, spraying, and fertilizing [44].

Quantitative Data on Nutrient Depletion in Crops

The following tables summarize key findings from research on the historical decline of essential nutrients in food crops, which provides critical context for research into high-yielding varieties.

Table 1: Decline in Mineral Content in Fruits and Vegetables (1930s - 1990s)

| Mineral | Average Decline Reported | Time Period | Key Studies & Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper (Cu) | 34% - 81% | 1940 - 1991 | [3] |

| Iron (Fe) | 24% - 50% | 1940 - 1991 | [3] |

| Calcium (Ca) | 16% - 46% | 1936 - 1987 | [3] |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 16% - 35% | 1936 - 1991 | [3] |

| Sodium (Na) | 29% - 52% | 1940 - 2019 | [3] |

| Potassium (K) | 6% - 20% | 1963 - 1992 | [3] |

Table 2: Decline in Vitamin and Protein Content in Fruits and Vegetables (Over ~50 years)

| Nutrient | Average Decline | Time Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | 18% - 21.4% | 1975 - 1997 | Losses up to 68.3% in specific vegetables like cauliflower [3] |

| Vitamin C | 15% - 29.9% | 1975 - 1997 | [3] |

| Riboflavin | 38% | Previous half-century | Analysis of 43 different fruits and vegetables [3] |

| Protein | 6% | Previous half-century | Analysis of 43 different fruits and vegetables [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Precision Nutrient Management

Protocol 1: Developing a Site-Specific Nutrient Management Plan using the 4R Framework

This protocol aligns with the USDA's SMART Nutrient Management approach [41].

Site Assessment (The "Assessment" in SMART)

- Soil Analysis: Collect soil samples based on zones determined by historical yield data, remote sensing imagery, or grid sampling. Analyze for soil type, pH, organic matter, and baseline levels of N, P, K, and other micronutrients [41].

- Risk Assessment: Conduct risk assessments for potential nitrogen and phosphorus losses specific to your operation, considering soil drainage and flooding frequency [41].

Crop Nutrient Budgeting

- Establish a crop nutrient budget for your rotation using recent average yields to estimate nutrient removal [41].

4R Implementation

- Right Source: Select fertilizer sources (synthetic, manure, compost) based on soil chemistry and crop availability. Consider enhanced efficiency fertilizers to reduce losses [41].

- Right Rate: Use the soil test results and crop nutrient budget to determine the application rate. Variable Rate Technology (VRT) maps should be created to apply different rates across the field based on spatial variability [42] [41].

- Right Time: Split applications of nutrients, especially nitrogen, to align with key crop growth stages and minimize leaching or denitrification losses [41].

- Right Placement: Place nutrients in the root zone where plants can access them, considering methods like banding versus broadcasting to improve efficiency [41].

Monitoring and Validation

- In-Season Tissue Testing: Perform plant tissue analysis at critical growth stages to monitor nutrient status and adjust management if necessary [41].

- Yield Monitoring: Use GPS-enabled yield monitors on harvesters to record spatial yield data, which is crucial for validating the nutrient plan and refining it for the next season [44].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) using Precision Ag Technologies

- Establish Trial Plots: Designate areas within a field with different nutrient management strategies (e.g., uniform rate vs. VRT-based rate).

- Apply Inputs with Precision Equipment: Use a GPS-guided tractor with VRT to ensure precise application of inputs according to the experimental design [44].

- Monitor Crop Health with Remote Sensing: Deploy drones with multispectral cameras at key growth stages to collect high-resolution data on crop health (e.g., NDVI) and identify nutrient stresses [42].

- Measure Soil Moisture and Nutrients: Install in-ground sensors to continuously monitor soil moisture and nutrient levels (e.g., nitrate) in the different plots [43].

- Harvest and Analyze Yield Data: Use a yield monitor on the combine to record yield and moisture data for each plot [44].

- Calculate NUE: Calculate Nutrient Use Efficiency using the formula: NUE = (Yield in fertilized plot - Yield in unfertilized control) / Quantity of nutrient applied.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if differences in yield and NUE between the management strategies are statistically significant.

Workflow Visualization

Precision Nutrient Management Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Tools for Precision Nutrient Management Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| In-Ground Sensors | Provide near-real-time information on soil properties (temperature, moisture, nutrient levels) for continuous monitoring and data collection [43]. |

| Enhanced Efficiency Fertilizers | Slow-release or stabilized fertilizers used as the Right Source to control nutrient availability and reduce environmental losses [41]. |

| GPS/GNSS Guidance Systems | Enable precise positioning for soil sampling, guided equipment operation (autosteer), and creation of spatial data maps, crucial for the Right Placement [44]. |

| Variable Rate Technology (VRT) | A system that allows for the application of inputs (water, fertilizer) at varying rates across a field based on real-time data and predefined maps, addressing the Right Rate [44] [42]. |

| Drone with Multispectral Camera | A remote sensing platform that captures high-resolution imagery to monitor crop health, assess biomass, and detect nutrient deficiencies or water stress over large areas [42]. |

| Yield Monitoring System | A sensor installed on a combine harvester that records geo-referenced yield and moisture data, which is essential for validating the effectiveness of nutrient management strategies [44]. |

In the context of research addressing nutrient depletion in high-yielding crop varieties, biofortification has emerged as a critical strategy to combat micronutrient malnutrition, also known as "hidden hunger," which affects over two billion people globally [45] [46]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers and scientists developing biofortified crops through two primary approaches: conventional breeding and genetic engineering. While conventional breeding relies on existing genetic variation within crop species, genetic engineering enables precise introduction of novel traits beyond natural genetic constraints [47] [48]. Both strategies aim to increase essential vitamin and mineral densities in staple crops consumed by vulnerable populations who rely heavily on cereal-based diets deficient in vital phytochemicals [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Nutrient Accumulation in Conventionally Bred Varieties

Problem: Developed varieties show insufficient micronutrient concentration in edible parts despite selective breeding.

- Check genetic diversity of parent lines: Conventional breeding relies on natural genetic variation; if the available germplasm lacks sufficient diversity for the target nutrient, breeding progress will be limited [47]. Source additional germplasm from international seed banks if needed.

- Verify soil nutrient availability: Even with favorable genetics, plants cannot accumulate target minerals if they are absent from the growth medium [45]. Conduct soil tests and consider agronomic biofortification (e.g., zinc fertilizer application) as a complementary strategy [45].

- Assess environmental interactions: Nutrient expression can be influenced by environmental factors [45]. Repeat trials across multiple locations and seasons to identify genotype × environment (G×E) interactions.

- Evaluate anti-nutrient compounds: High levels of phytates or other anti-nutrients may reduce bioavailability [47]. Screen for low phytate variants and consider this trait in your breeding program.

Guide 2: Managing Regulatory and Public Acceptance Hurdles for Genetically Engineered Biofortified Crops

Problem: Genetically engineered biofortified crops face regulatory delays and public skepticism.

- Document precise genetic changes: New genetic engineering techniques like CRISPR/Cas9 are considered "recombinant enzymatic mutagens" with specific modes of action that differ from conventional breeding [48]. Maintain comprehensive records of all genetic modifications for regulatory submissions.

- Conduct rigorous bioavailability studies: Demonstrate that the added nutrients are bioavailable in humans. For example, iron-biofortified beans have been shown to improve iron stores in Rwandan women [49].

- Engage stakeholders early: Consumer acceptance is crucial, particularly for traits like color change in vitamin A-rich crops [49]. Initiate consumer education programs highlighting health benefits before product launch.

- Pursue combinatorial approaches: Stack multiple micronutrient traits to maximize health impact and resource efficiency [46]. This may improve cost-benefit calculations for regulators.

Guide 3: Resolving Agronomic Performance Issues in Biofortified Lines

Problem: Biofortified varieties show reduced yield or poor agronomic traits compared to conventional varieties.

- Backcross with elite varieties: Introduce the high-nutrient trait into well-adapted, high-yielding genetic backgrounds through repeated backcrossing [46].

- Evaluate yield stability: Test varieties across diverse environments to ensure robust performance. Farmers prioritize agronomic traits like disease resistance and yield stability [49].

- Monitor nutrient retention: Assess nutrient stability during storage, processing, and cooking [49]. Some nutrients may degrade post-harvest, reducing nutritional impact.

- Implement marker-assisted selection: Use molecular markers linked to both nutritional and agronomic traits to accelerate development of superior lines [47].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key technical advantages of genetic engineering over conventional breeding for biofortification?

Genetic engineering enables introduction of novel traits not available in the natural gene pool, precise manipulation of metabolic pathways, faster development times, and multi-nutrient stacking capabilities. Specifically, it allows biofortification of crops like rice and bananas that lack natural genetic variation for target nutrients [47]. Transgenic approaches can also manipulate nutrient storage and reduce anti-nutrients to enhance bioavailability [47] [46].

FAQ 2: How long does it typically take to develop a biofortified crop variety using conventional versus transgenic approaches?