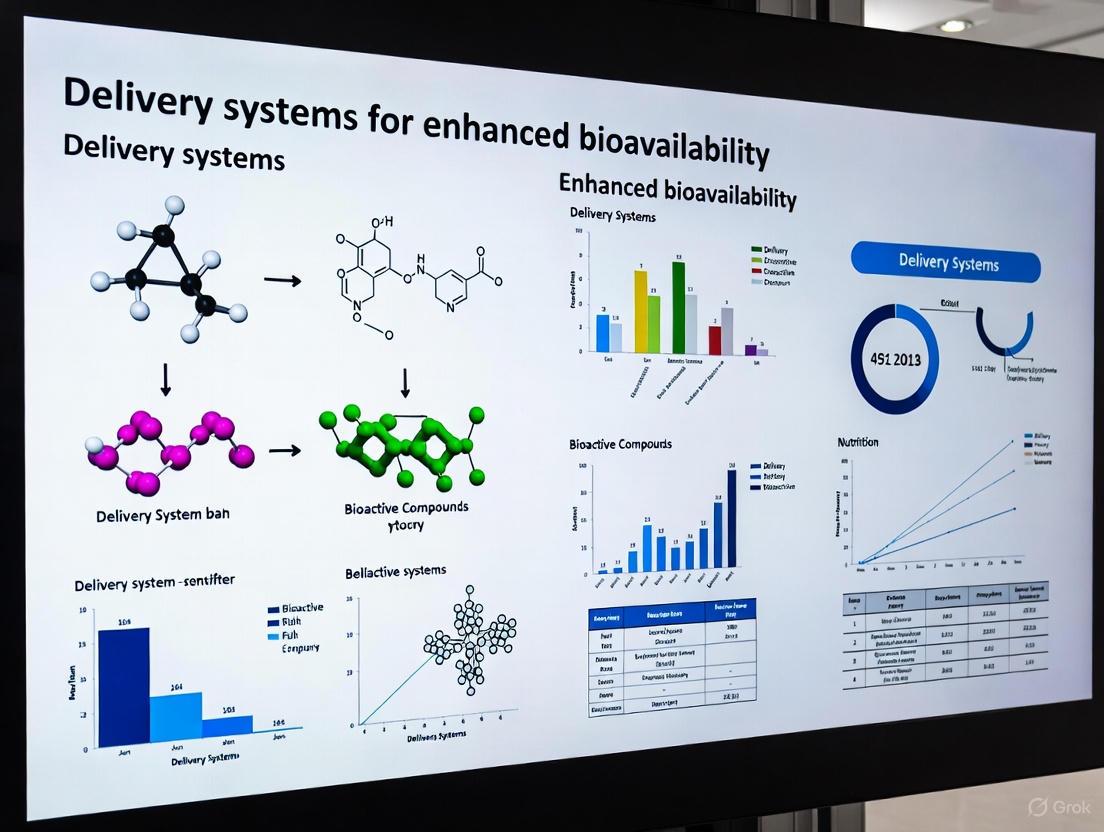

Advanced Delivery Systems for Enhanced Bioavailability: 2025 Strategies for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cutting-edge drug delivery systems designed to overcome bioavailability challenges.

Advanced Delivery Systems for Enhanced Bioavailability: 2025 Strategies for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cutting-edge drug delivery systems designed to overcome bioavailability challenges. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles governing drug absorption, examines innovative methodological approaches from nanocarriers to smart delivery systems, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for high-concentration formulations, and validates technologies through comparative analysis of preclinical and clinical data. The synthesis of current trends and validation frameworks aims to guide the development of more effective, targeted, and patient-friendly therapeutics.

Understanding Bioavailability: Fundamental Barriers and Physicochemical Principles

For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimization of bioavailability remains a pivotal challenge in pharmaceutical sciences. The journey of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from administration to its site of action is governed by a series of complex interactions, the foundation of which rests on its fundamental physicochemical properties. Among these, solubility, lipophilicity, and molecular size are recognized as the primary triumvirate dictating the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of therapeutic agents [1] [2]. These properties are intrinsically linked to the principles of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), which categorizes drugs based on their solubility and intestinal permeability, providing a predictive framework for bioavailability [3].

In the contemporary landscape of drug discovery, the prevalence of poorly soluble compounds has increased significantly, with estimates suggesting that over 70% of new chemical entities (NCEs) face substantial challenges due to low aqueous solubility [3]. Furthermore, the emergence of novel therapeutic modalities, including peptides, oligonucleotides, and other middle-to-large molecules, has brought the challenge of molecular size to the forefront [4]. This application note delineates the critical interplay between these key properties and bioavailability, providing structured quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols to support formulation strategies and research efforts aimed at enhancing the pharmacological potential of drug candidates.

The relationship between physicochemical properties and bioavailability can be quantitatively described through established parameters and their acceptable ranges for oral bioavailability. The following table summarizes these critical properties and their optimal ranges for drug-like molecules.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties and Their Impact on Bioavailability

| Property | Description | Optimal Range for Oral Bioavailability | Primary Impact on Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | The concentration of a drug in a saturated solution in a specific solvent (e.g., water) at a given temperature [3]. | >0.1 mg/mL (High) | Governs dissolution rate and extent, limiting absorption for BCS Class II and IV drugs [3] [5]. |

| Lipophilicity (Log P) | The partition coefficient of a drug between octanol and water, representing its hydrophobicity [2]. | Log P ≈ 1-5 [2] | Influences membrane permeability; values that are too low or too high can hinder absorption [2]. |

| Molecular Size (MW) | The molecular weight of the drug compound. | MW ≤ 500 [4] | Affects diffusion rates and permeability through biological membranes [4]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | The total number of OH and NH groups. | ≤5 [4] | Impacts passive diffusion across lipid membranes. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | The total number of O and N atoms. | ≤10 [4] | Influences solubility and membrane permeability. |

| Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | The surface area over all polar atoms (usually oxygen and nitrogen). | <140 Ų [4] | Correlates strongly with passive molecular transport through membranes. |

Property-Specific Analysis and Experimental Protocols

Solubility

Role in Bioavailability

Solubility is a fundamental determinant of a drug's dissolution rate, which is often the rate-limiting step for absorption following oral administration [3] [5]. A drug must be in solution to permeate the gastrointestinal epithelium. Consequently, drugs with low aqueous solubility (BCS Class II and IV) frequently exhibit poor and highly variable bioavailability, posing a significant challenge in drug development [3] [6]. For instance, the low solubility of pharmacoactive molecules limits their pharmacological potential and conveys a higher risk of failure for drug innovation and development [3].

Experimental Protocol: Shake-Flask Method for Equilibrium Solubility Determination

This is the standard method for determining the equilibrium solubility of a drug substance.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Test Compound: The drug substance of interest.

- Solvent: Purified water or relevant buffer solutions (e.g., phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8 to simulate gastrointestinal conditions).

- Internal Standard (for HPLC): A chemically stable compound with a known retention time that does not interfere with the analyte (e.g., caffeine for reverse-phase HPLC).

- HPLC Mobile Phase: Appropriately prepared mixture of water and acetonitrile or methanol, often with modifiers like trifluoroacetic acid or formic acid.

Procedure:

- Preparation: An excess amount of the solid test compound is added to a glass vial containing a known volume (e.g., 5-10 mL) of the solvent.

- Equilibration: The suspension is sealed and agitated using a mechanical shaker incubator at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a sufficient period (typically 24-72 hours) to reach equilibrium.

- Separation: After equilibration, the suspension is centrifuged at high speed (e.g., 10,000 rpm for 10-15 minutes) or filtered using a syringe filter (e.g., 0.45 µm) to separate the undissolved solid.

- Analysis: The supernatant or filtrate is appropriately diluted and analyzed using a validated analytical method, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection, to quantify the concentration of the dissolved drug.

- Calculation: The solubility is calculated as the concentration of the drug in the saturated solution, typically reported in µg/mL or mg/mL.

Lipophilicity

Role in Bioavailability

Lipophilicity, commonly measured as the logarithm of the octanol-water partition coefficient (Log P), is a critical property that influences a drug's permeability through lipid bilayer membranes [2]. It governs the balance between a drug's affinity for aqueous environments (e.g., blood, cytosol) and lipophilic environments (e.g., cell membranes). An optimal Log P value facilitates passive diffusion across the gastrointestinal barrier. However, excessively high lipophilicity can lead to poor aqueous solubility, increased metabolic clearance, and non-specific binding to proteins and tissues, thereby reducing bioavailability [2]. Lipophilicity also affects a drug's distribution, its interaction with metabolic enzymes like Cytochrome P450, and its susceptibility to efflux by transporters like P-glycoprotein [7] [2].

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Log P via the Shake-Flask Method

This is a classic and direct method for measuring the partition coefficient.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- n-Octanol: HPLC-grade, pre-saturated with the aqueous buffer.

- Aqueous Buffer: Typically a phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.1 M, pH 7.4), pre-saturated with n-octanol.

- Test Compound Solution: A known concentration of the drug dissolved in either the octanol-saturated buffer or the buffer-saturated octanol.

Procedure:

- Pre-saturation: Equal volumes (e.g., 10 mL each) of n-octanol and the aqueous buffer are mixed by shaking for at least 24 hours and allowed to separate. The two phases are then collected separately.

- Partitioning: A known volume of the test compound solution is placed in a separation funnel or glass vial. An equal volume of the other pre-saturated phase is added (e.g., if the drug is in the aqueous phase, add the pre-saturated octanol).

- Equilibration: The mixture is shaken vigorously for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 hour) at a constant temperature and then allowed to stand for complete phase separation.

- Analysis: The concentration of the drug in both the octanol phase (Coctanol) and the aqueous phase (Cwater) is determined using an appropriate analytical method like HPLC-UV.

- Calculation: The partition coefficient, P, is calculated as: P = Coctanol / Cwater. The value is typically reported as its logarithm: Log P = log₁₀(P).

Molecular Size

Role in Bioavailability

Molecular size, often represented by molecular weight (MW), directly impacts a compound's diffusion coefficient and its ability to traverse porous membranes and paracellular pathways [4]. According to Lipinski's Rule of Five, a molecular weight under 500 Da is generally favorable for passive absorption and oral bioavailability [4]. Larger molecules, such as peptides and oligonucleotides (often with MW > 1000 Da), face significant challenges in permeating the gastrointestinal epithelium due to their size and high hydrogen bonding potential, leading to extremely low oral bioavailability (often <1-2%) [4]. This is a primary hurdle for the oral delivery of new modality drugs.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Permeability as a Surrogate for Size and Polarity Effects

While molecular weight is a straightforward calculation, its functional impact on bioavailability is best assessed through permeability studies.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Transport Buffer: Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

- Test Compound: Dissolved in transport buffer at a suitable concentration.

- Lucifer Yellow Solution: A fluorescent marker for monitoring monolayer integrity in cell-based assays.

- Caco-2 Cells: Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line, cultured on semi-permeable transmembrane inserts.

Procedure (Caco-2 Monolayer Assay):

- Cell Culture: Culture Caco-2 cells on collagen-coated polyester membrane inserts in transwell plates until they form a confluent, differentiated monolayer (typically 21 days).

- Integrity Check: Before the experiment, measure the Trans-Epithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) and/or the paracellular flux of Lucifer Yellow to ensure monolayer integrity.

- Bidirectional Transport:

- Apical-to-Basolateral (A-B): Add the test compound solution to the apical (top) chamber and fresh buffer to the basolateral (bottom) chamber.

- Basolateral-to-Apical (B-A): Add the test compound solution to the basolateral chamber and fresh buffer to the apical chamber.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes), sample aliquots from the receiver chamber and replace with fresh pre-warmed buffer.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in the samples using LC-MS/MS or HPLC.

- Calculation: Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) using the formula: Papp (cm/s) = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane surface area, and C₀ is the initial donor concentration.

Visualization of Property Interrelationships and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the complex interplay between the key physicochemical properties and their collective impact on the drug development process for bioavailability enhancement.

Figure 1: Interplay of Physicochemical Properties and Formulation Strategies. This diagram illustrates how solubility, lipophilicity, and molecular size collectively influence dissolution and permeability, the two key determinants of oral bioavailability. Corresponding formulation strategies to overcome deficiencies in each property are shown (red arrows: problems, green arrows: solutions).

Figure 2: Decision Workflow for Bioavailability Enhancement. A logical workflow for selecting an appropriate formulation strategy based on initial physicochemical profiling and Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) categorization of a new chemical entity (NCE).

Advanced Techniques and Research Toolkit

Advanced Formulation Technologies

To overcome limitations posed by poor solubility, high lipophilicity, or large molecular size, advanced formulation strategies are employed.

Table 2: Advanced Technologies for Bioavailability Enhancement

| Technology Platform | Mechanism of Action | Ideal for Property Deficiency | Example Commercial Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASD) | Creates a high-energy amorphous form of the API stabilized by polymers, enhancing solubility and dissolution rate [3] [6]. | Low Solubility (BCS II) | Norvir (ritonavir) [3] |

| Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems (LBDDS) | Enhances solubility and lymphatic absorption of lipophilic drugs via emulsification or micelle formation in the GI tract [7] [6]. | Low Solubility, High Lipophilicity | Neoral (cyclosporine) [4] |

| Nanocrystals | Reduces particle size to the nanoscale, dramatically increasing the surface area and dissolution rate (Noyes-Whitney equation) [3] [8]. | Low Solubility (BCS II) | Rapamune (sirolimus) |

| Prodrugs | Chemically modifies the API into an inactive form with better solubility or permeability, which is then converted to the active form in vivo [3]. | Low Solubility, Low Permeability | Valacyclovir (prodrug of acyclovir) |

| Permeation Enhancers | Transiently and reversibly disrupt the intestinal epithelium to improve paracellular/transcellular transport of APIs [4]. | Low Permeability, Large Size (Peptides) | Rybelsus (semaglutide with SNAC) [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials used in the experimental protocols and formulation technologies described in this note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Simulates gastric and intestinal fluids for in vitro dissolution testing, containing bile salts and phospholipids [7]. | FaSSGF, FaSSIF, FeSSIF |

| Partitioning Solvents | Used for experimental determination of lipophilicity (Log P/D). | n-Octanol, Buffer Solutions (pH 7.4) |

| Polymeric Carriers | Used in Amorphous Solid Dispersions to inhibit recrystallization and maintain the supersaturated state of the API [3]. | HPMC, HPMCAS, PVP, PVP-VA |

| Lipid Excipients | Core components of Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems (LBDDS) like SEDDS [7] [6]. | Medium/Long-Chain Triglycerides, Oleic Acid, Labrafil |

| Surfactants / Solubilizers | Aid in wetting, solubilization, and stabilization of emulsions or micelles [3] [6]. | Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80), D-α-Tocopheryl PEG 1000 Succinate (TPGS) |

| Permeation Enhancers | Improve absorption of poorly permeable drugs, particularly peptides [4]. | Sodium Caprate (C10), Salcaprozate Sodium (SNAC) |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A standard in vitro model for predicting human intestinal permeability and absorption [4]. | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line |

The intricate interplay between solubility, lipophilicity, and molecular size forms the cornerstone of bioavailability prediction and enhancement. A deep understanding of these properties, facilitated by robust experimental protocols and a structured decision-making workflow, is indispensable for modern drug development. As the pipeline of new chemical entities continues to be dominated by poorly soluble compounds and the therapeutic landscape expands to include middle-to-large molecules, the strategic application of advanced formulation technologies—from solid dispersions and lipidic systems to permeation enhancers—becomes increasingly critical. By systematically characterizing these key physicochemical properties and leveraging the appropriate toolkit, researchers and scientists can effectively navigate the challenges of bioavailability, thereby accelerating the development of viable and effective therapeutic agents.

The efficacy of any pharmacologically active substance is fundamentally constrained by the biological barriers it must traverse to reach its site of action. These barriers, which vary significantly across different routes of administration, determine the rate and extent of drug absorption, thereby directly influencing bioavailability and therapeutic outcome [9] [10]. Understanding the distinct physicochemical and physiological challenges posed by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and subcutaneous tissue is a prerequisite for the rational design of advanced delivery systems aimed at enhanced bioavailability [11]. This application note provides a structured overview of these barriers, summarizes key quantitative data, and outlines detailed experimental protocols for researchers and drug development professionals working within the broader context of delivery system development.

Biological Barriers of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The GI tract is a complex and dynamic environment where drug absorption is influenced by a series of sequential and overlapping barriers.

Luminal and Mucosal Barriers

Orally administered drugs first encounter the luminal environment, characterized by varying pH levels, digestive enzymes, and the presence of food and other gut contents [10]. The drug must then cross the mucosal layer, a thick glycoprotein-based barrier that can trap drugs and impede their access to the epithelial surface.

Cellular and Membrane Transport Barriers

The intestinal epithelium itself presents the most significant hurdle, primarily through its semipermeable cell membranes [9] [10]. The most common mechanism of absorption for drugs is passive diffusion, driven by the concentration gradient across the membrane. The rate of diffusion is heavily influenced by the drug's lipid solubility, size, and degree of ionization [10]. The ionized form of a drug has low lipid solubility and high electrical resistance, making membrane penetration difficult. The proportion of the un-ionized form, which is lipid-soluble and can diffuse readily, is determined by the environmental pH and the drug's acid dissociation constant (pKa) [9] [10]. This relationship explains why weakly acidic drugs are more readily absorbed from the stomach, while absorption for most drugs, including weak bases, predominates in the small intestine due to its vast surface area [10].

Other transport mechanisms include:

- Facilitated passive diffusion: Uses carrier molecules for substrates with specific molecular configurations without energy expenditure [10].

- Active transport: Selective, requires energy, and can transport drugs against a concentration gradient; it is typically reserved for drugs structurally similar to endogenous substances like ions or sugars [9] [10].

- Efflux transporters: Proteins like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) actively secrete molecules back into the intestinal lumen, effectively restricting overall absorption [9].

Pre-systemic Metabolism

Before reaching the systemic circulation, drugs absorbed from the GI tract pass through the liver via the portal vein, where they may undergo significant first-pass metabolism, reducing the amount of active drug available [9].

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing GI Drug Absorption

| Parameter | Impact on Absorption | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Solubility (Log P) | High lipid solubility favors passive diffusion through lipoid cell membranes [10]. | Determine partition coefficient in octanol/water systems. |

| pKa & pH Environment | Governs the fraction of un-ionized, absorbable drug. Weak acids absorb better in acidic stomach; weak bases in alkaline intestine [9] [10]. | Use potentiometric titration for pKa; simulate GI pH in dissolution tests. |

| Particle Size & Surface Area | Reduced particle size increases surface area, enhancing dissolution rate (critical for BCS Class II drugs) [9]. | Laser diffraction for particle sizing; use micronized API in formulations. |

| GI Transit Time | Impacts time available for dissolution and absorption; particularly critical for drugs absorbed via active transport or with slow dissolution [10]. | Gamma scintigraphy to track formulated product transit. |

| Solubility & Dissolution Rate | Drugs must be in solution to be absorbed; dissolution can be the rate-limiting step [10]. | USP dissolution apparatus I (baskets) or II (paddles) with biorelevant media. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential barriers a drug encounters during oral administration and the primary transport mechanisms available for absorption.

Biological Barriers of the Subcutaneous Tissue

Subcutaneous (SC) administration bypasses the GI tract, avoiding first-pass metabolism and the harsh luminal environment. However, it presents a unique set of barriers primarily related to the extracellular matrix and the vascular and lymphatic systems.

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Interstitial Fluid

Following SC injection, a drug encounters the interstitial space, a gel-like environment filled with hyaluronic acid, collagen, and other proteins that can sterically hinder the diffusion of larger molecules like therapeutic proteins (TPs) [11]. The composition and viscosity of the interstitial fluid can significantly impact drug mobility.

Vascular and Lymphatic Transport

For small molecules, absorption into the systemic circulation occurs primarily via diffusion across capillary walls, which is highly dependent on local blood perfusion [10]. For larger molecules, such as TPs with a molecular mass > 20,000 g/mol, movement across the continuous endothelium of blood capillaries is severely restricted. For these macromolecules, the lymphatic system becomes the dominant absorption pathway [10] [11]. This process is generally slower than vascular absorption, leading to delayed and often incomplete bioavailability due to potential catabolism by proteolytic enzymes within the lymphatics [10].

The transcapillary transport of TPs is mathematically described by equations accounting for diffusion, convection, and the reflection coefficient (σ), which represents the fraction of a solute unable to cross vascular pores. This is often modeled using two-pore theory, which posits that capillaries contain a population of small pores and a much smaller number of large pores, with the latter being the primary route for macromolecule extravasation [11].

Table 2: Key Parameters Influencing Subcutaneous Drug Absorption

| Parameter | Impact on Absorption | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight/Size | Small molecules (<1 kDa) enter bloodstream via capillaries; large molecules (>20 kDa) rely on slower lymphatic uptake [10] [11]. | Critical for biologics and peptide delivery. |

| Local Blood Flow (Perfusion) | Directly affects absorption rate of small molecules; can be reduced in shock or hypotension [10]. | Explains inter- and intra-subject variability. |

| Lymphatic Flow Rate | Governs the rate of absorption for large proteins and particulates [11]. | Key parameter for PBPK modeling of mAbs. |

| Transcapillary Transport | Described by fluid dynamics (convection/diffusion) and pore theory (reflection coefficient) [11]. | Foundation for mechanistic PK models. |

| Enzymatic Degradation (SC tissue) | Susceptibility to proteolysis in the interstitial space or lymphatics can reduce bioavailability [10]. | Requires stabilization via formulation. |

The diagram below visualizes the primary absorption pathways for small and large molecules following subcutaneous injection.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Absorption Barriers

Protocol: In Situ Closed-Loop Method for GI Fluid Dynamics

This protocol, adapted from Sudo et al., quantitatively analyzes real-time fluid absorption and secretion in specific intestinal regions [12].

1. Objective: To kinetically determine the rate constants of fluid absorption (kabs) and secretion (ksec) in the jejunum, ileum, and colon of rat models.

2. Materials:

- Animal Model: Anesthetized rats.

- Test Solutions: Isotonic solution (e.g., 0 mOsm/kg water) and isosmotic solution (e.g., 300 mOsm/kg mannitol).

- Non-absorbable Volume Marker: Fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran 4000 (FD-4).

- Tracer for Real Water Absorption: Tritiated water ([³H]water).

- Surgical Equipment: For laparotomy and creation of closed intestinal loops.

- Analytical Equipment: Scintillation counter, fluorescence spectrophotometer.

3. Methodology:

- Surgical Preparation: Anesthetize the rat and perform a laparotomy. Gently isolate target intestinal segments (jejunum, ileum, colon) and ligate them to create closed loops, ensuring intact blood supply.

- Dosing: Inject a known volume (e.g., 0.5 mL) of test solution containing FD-4 and [³H]water into each loop.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 min), excise the entire loop. Wash the luminal content and collect the fluid.

- Analysis:

- Measure FD-4 concentration via fluorescence to track the apparent fluid volume.

- Measure [³H]water radioactivity via scintillation counting to track real water absorption.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the apparent absorption rate constant (kabs,app) from the FD-4 time profile.

- Calculate the real fluid absorption rate constant (kabs) from the [³H]water time profile.

- Use a kinetic model to estimate the secretion rate constant (ksec) by fitting the FD-4 data with the fixed kabs value [12].

Protocol: Assessing Subcutaneous Absorption of Therapeutic Proteins

This protocol outlines a method to evaluate the absorption kinetics of proteins via the subcutaneous route, with a focus on lymphatic uptake.

1. Objective: To determine the bioavailability and absorption rate of a model therapeutic protein following SC administration and to characterize the contribution of the lymphatic system.

2. Materials:

- Animal Model: Rodents or larger species (e.g., minipigs).

- Test Article: Radiolabeled protein (e.g., ¹²⁵I-labeled monoclonal antibody).

- Surgical Equipment: For cannulation of the thoracic lymph duct.

- Formulation Buffer: Physiologic buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4).

- Analytical Equipment: Gamma counter, HPLC system for bioanalysis.

3. Methodology:

- Lymph Cannulation Study: Anesthetize the animal and cannulate the thoracic lymph duct to enable continuous collection of lymph.

- Dosing: Administer the radiolabeled protein via SC injection at a standardized site (e.g., interscapular region).

- Sample Collection:

- Collect lymph at serial time intervals post-dose for up to 48-72 hours. Record lymph volume for each interval.

- Collect blood/plasma samples in parallel.

- Analysis:

- Measure radioactivity in lymph and plasma samples using a gamma counter.

- For non-labeled proteins, use ELISA or LC-MS/MS to determine protein concentration.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot concentration-time profiles in lymph and plasma.

- Calculate the cumulative amount of protein recovered in lymph over time. The fraction absorbed via lymph is the total cumulative amount in lymph divided by the administered dose.

- Use non-compartmental analysis to determine pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, Tmax, AUC) in plasma and compare with IV data to calculate absolute bioavailability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Absorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| FD-4 (FITC-Dextran 4,000 Da) | Non-absorbable fluorescent marker for tracking apparent fluid volume changes in the GI lumen [12]. | In situ closed-loop studies to measure GI fluid secretion kinetics. |

| [³H]Water (Tritiated Water) | Radiolabeled tracer for quantifying real water absorption across intestinal membranes, independent of secretion [12]. | Differentiating between absorption and secretion processes in kinetic models. |

| Radiolabeled Proteins (e.g., ¹²⁵I-IgG) | Enables sensitive and quantitative tracking of large molecule disposition, including lymphatic absorption and tissue distribution [11]. | Studying SC absorption and lymphatic uptake of monoclonal antibodies. |

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Inhibitors | Chemical tools to inhibit efflux transporter activity and elucidate its role in limiting oral drug absorption [9]. | Verifying P-gp-mediated drug efflux in Caco-2 cell models or perfused intestine. |

| In Situ Closed-Loop Apparatus | Surgical setup for isolating specific intestinal segments to study regional absorption in a controlled environment [12]. | Investigating region-dependent differences in jejunal, ileal, and colonic absorption. |

| Lymph Cannulation Setup | Surgical preparation for direct collection of lymph from the thoracic duct to quantify lymphatic drug transport [10]. | Determining the fraction of a SC-administered protein absorbed via the lymphatics. |

The biological barriers presented by the GI tract and subcutaneous tissue are complex and multifaceted, demanding a mechanistic understanding for successful drug development. The GI tract challenges drugs with pH gradients, metabolic enzymes, efflux transporters, and a dynamically changing fluid environment [9] [12] [10]. In contrast, subcutaneous absorption is governed by the physiology of the interstitium and the differential accessibility of the vascular versus lymphatic systems, which is highly dependent on molecular size [10] [11]. The experimental protocols and research tools detailed herein provide a foundation for systematically deconstructing these barriers. Integrating data from such studies into physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models, including those accounting for two-pore transcapillary transport, is a powerful strategy to predict in vivo performance and accelerate the design of delivery systems that optimize bioavailability across a wide range of drug candidates [11].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) in Modern Drug Development

The Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) is a fundamental scientific framework that has revolutionized the development of oral drug products since its introduction in 1995. Developed by Amidon and colleagues, the BCS serves as a prognostic tool for classifying drug substances based on their aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability, two key factors governing the rate and extent of oral drug absorption [13] [14]. This system provides a rational approach for predicting in vivo drug performance from in vitro measurements, thereby enabling more efficient drug development processes.

The regulatory adoption of BCS principles by agencies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), World Health Organization (WHO), and European Medicines Agency has transformed biopharmaceutical assessment strategies [13]. By establishing a correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo bioavailability, the BCS allows for a science-based approach to biowaiver grants – regulatory approvals that replace certain bioequivalence studies with accurate in vitro dissolution testing [13] [14]. This application significantly reduces development costs, minimizes unnecessary drug exposure in healthy volunteers, and accelerates the availability of generic medicines, particularly for immediate-release solid oral dosage forms.

BCS Fundamentals and Classification Framework

Core Principles and Classification Criteria

The BCS categorizes drug substances into four distinct classes based on three primary parameters that control drug absorption: solubility, intestinal permeability, and dissolution rate [13]. The system evaluates the interplay between these factors to identify the rate-limiting steps in oral drug absorption.

Solubility criteria are defined by the highest dose strength of an immediate-release product. A drug is classified as highly soluble when this dose dissolves in 250 mL or less of aqueous media across the pH range of 1.0 to 6.8, simulating the physiological variations throughout the gastrointestinal tract [13] [15]. This volume is derived from typical bioequivalence study protocols where drugs are administered to fasting volunteers with a glass of water.

Permeability classification is based on the extent of intestinal absorption in humans. A drug substance is considered highly permeable when the systemic absorption is determined to be 90% or more of the administered dose, based on mass-balance studies or comparison to an intravenous reference dose [13] [15]. Permeability can be assessed through various methods including in vitro cell cultures (e.g., Caco-2), in situ intestinal perfusion, or in vivo human studies.

Dissolution rate is evaluated using standard United States Pharmacopeia (USP) apparatus. A drug product is considered to have rapid dissolution when 85% or more of the labeled amount dissolves within 30 minutes using USP Apparatus 1 at 100 rpm or Apparatus 2 at 50 rpm in 900 mL of buffer solutions at pH 1.0, 4.5, and 6.8 [13].

The Four BCS Classes

The BCS framework divides drugs into four distinct classes, each with characteristic absorption patterns and development challenges:

Class I (High Solubility, High Permeability): These drugs exhibit excellent absorption profiles as they encounter no significant barriers to bioavailability. Their absorption is generally rapid and complete, with the dissolution rate typically being the rate-limiting step [13] [15]. Examples include metoprolol and paracetamol.

Class II (Low Solubility, High Permeability): These compounds face solubility-limited absorption, where the slow dissolution rate in gastrointestinal fluids restricts bioavailability. While highly permeable once in solution, their poor solubility presents formulation challenges [13]. Common examples include ketoconazole, griseofulvin, and ibuprofen.

Class III (High Solubility, Low Permeability): For these drugs, permeability represents the major barrier to absorption. Although they readily dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids, their poor membrane penetration limits systemic exposure [13] [15]. Cimetidine is a representative Class III drug.

Class IV (Low Solubility, Low Permeability): These compounds face significant development challenges due to multiple barriers to absorption. They exhibit both poor dissolution and limited membrane penetration, resulting in low and highly variable bioavailability [15]. Bifonazole exemplifies this problematic class.

Table 1: BCS Classification System with Example Drugs [13] [15]

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Absorption Pattern | Rate-Limiting Step | Example Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Well-absorbed | Gastric emptying | Metoprolol, Paracetamol |

| Class II | Low | High | Solubility-limited | Dissolution rate | Ketoconazole, Griseofulvin, Ibuprofen |

| Class III | High | Low | Permeability-limited | Permeability | Cimetidine |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Poorly absorbed | Multiple factors | Bifonazole |

Advanced BCS-Based Framework: The Developability Classification System

The Developability Classification System (DCS) represents an evolution of the BCS framework with enhanced focus on formulation development strategies [16]. While maintaining the fundamental principles of BCS, the DCS introduces several critical refinements to better predict in vivo performance and guide formulation approaches.

The DCS incorporates intestinal solubility rather than simple aqueous solubility, recognizing the importance of biorelevant media that better simulates intestinal conditions [16]. It acknowledges the compensatory relationship between solubility and permeability, particularly for Class II drugs, and introduces the concept of Solubility Limited Absorbable Dose (SLAD). Most importantly, the DCS provides practical guidance on target particle size needed to overcome dissolution rate-limited absorption, offering direct formulation development input [16].

This advanced framework enables more accurate identification of critical factors limiting oral absorption and provides specific formulation strategies to address these limitations, making it particularly valuable for early-stage development decisions.

Experimental Protocols for BCS Determination

Equilibrium Solubility Measurement Protocol

Objective: To determine the solubility classification of a drug substance according to BCS criteria.

Materials:

- Drug substance (highest dose strength)

- Buffer solutions: pH 1.0 (0.1 N HCl), pH 4.5, pH 6.8

- Water bath shaker maintained at 37°C ± 1°C

- Analytical equipment (HPLC or UV-Vis spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Prepare saturated solutions of the drug substance in each buffer medium by adding excess solid to vessels containing 250 mL of each solution.

- Agitate the solutions in a water bath shaker at 37°C for 24 hours or until equilibrium is established.

- After equilibration, filter portions of each solution through a 0.45 μm membrane filter, discarding the first few mL.

- Analyze the filtrate quantitatively using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC).

- Calculate solubility in each medium and compare to the drug's highest dose strength.

Classification: A drug is considered highly soluble if the highest dose strength is soluble in ≤250 mL of aqueous media across the entire pH range [13] [15].

Permeability Assessment Protocol

Objective: To determine the permeability classification of a drug substance.

In Vitro Cell-Based Method (Caco-2 Model):

Materials:

- Caco-2 cell monolayers (21-28 days post-seeding)

- Transport buffer (HBSS with 25 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4)

- Test compound at appropriate concentration

- LC-MS/MS system for analysis

Procedure:

- Wash cell monolayers with pre-warmed transport buffer.

- Add drug solution to the donor compartment (apical for A→B transport, basolateral for B→A transport).

- Sample from the receiver compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes).

- Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS to determine drug concentration.

- Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt) × (1/(A × C0)), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane surface area, and C0 is the initial donor concentration.

Classification: Compounds with Papp values comparable to or higher than established high-permeability markers (e.g., metoprolol) are classified as highly permeable [13].

Dissolution Testing Protocol

Objective: To determine the dissolution characteristics of immediate-release solid oral dosage forms.

Materials:

- USP Dissolution Apparatus 1 (baskets) or 2 (paddles)

- Dissolution media: 0.1 N HCl, pH 4.5 buffer, pH 6.8 buffer (900 mL each)

- Water bath maintained at 37°C ± 0.5°C

- Automated sampler or manual sampling apparatus

- Analytical instrument for quantification

Procedure:

- Place one dosage unit in each vessel of the dissolution apparatus containing pre-warmed media.

- Operate apparatus at specified conditions (100 rpm for Basket, 50 rpm for Paddle).

- Withdraw samples at appropriate time intervals (e.g., 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60 minutes).

- Filter samples immediately through 0.45 μm membrane filters.

- Analyze samples using validated analytical methods.

- Calculate percentage dissolved at each time point.

Classification: A drug product is considered rapidly dissolving when ≥85% of the labeled amount dissolves within 30 minutes in all three media [13].

Formulation Strategies for BCS Classes

BCS Class II Formulation Approaches

BCS Class II drugs represent a significant formulation challenge due to their solubility-limited absorption. Multiple advanced strategies have been developed to enhance their bioavailability:

Physical Modifications:

- Micronization: Reduction of particle size to 1-10 microns through jet milling or spray drying increases surface area and dissolution rate. Example: Griseofulvin bioavailability is significantly improved through micronization [13].

- Nanonization: Production of drug nanocrystals (200-600 nm) using techniques such as pearl milling or high-pressure homogenization. This approach has successfully enhanced bioavailability of drugs including estradiol, doxorubicin, and cyclosporin [13].

- Sonocrystallization: Application of ultrasound (20 KHz-5 KHz) to induce crystallization and create particles with enhanced solubility properties. This method increased ketoconazole solubility by 5.5-fold [13].

Solid Dispersion Systems: Solid dispersions incorporate hydrophobic drugs into hydrophilic matrices such as polyvinylpyrrolidone, polyethylene glycol, or surfactants. Preparation methods include:

- Hot-melt method (fusion method): Direct heating of drug and carrier followed by rapid cooling and solidification [13].

- Solvent evaporation method: Dissolution of drug and carrier in volatile solvent followed by solvent removal [13].

Polymorph Selection: Utilization of amorphous or metastable crystalline forms that demonstrate higher solubility compared to stable crystalline forms. The solubility order of different solid forms follows: Amorphous > Metastable > Stable > Anhydrates > Hydrates > Solvates [13].

Advanced Delivery Systems for Challenging Compounds

Nanoparticle Formulations: Recent advances in nanoparticle technology have enabled the development of high drug-load formulations for poorly soluble compounds. A notable example includes a 45% drug-loaded amorphous nanoparticle (ANP) formulation for a BCS Class IV compound, manufactured through solvent/antisolvent precipitation. This approach demonstrated comparable bioavailability to conventional amorphous solid dispersion tablets in human clinical studies, offering a solution to the high pill burden typically associated with BCS Class IV drugs [17].

Liposil Nanohybrid Systems: Silica-coated liposomes (liposils) represent an innovative approach for enhancing the stability and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs like ibrutinib (BCS Class II). These systems are synthesized via the liposome templating method, creating spherical particles of approximately 240 nanometers that demonstrate sustained drug release in intestinal fluids and resistance to gastric conditions. Pharmacokinetic studies in rats showed a 4.08-fold increase in half-life and 3.12-fold improvement in bioavailability compared to drug suspensions [18].

Multifunctional Particulate Systems: Various advanced delivery systems have been developed to enhance the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of bioactive compounds:

- Zein-MSC nanoparticles: Microbial transglutaminase-induced cross-linked sodium caseinate stabilized nanoparticles significantly improved photo-stability and bioaccessibility of resveratrol [19].

- Starchy colon-targeting delivery systems: Layer-by-layer assembly of starchy polyelectrolytes protects insulin nanoparticles from degradation in the gastrointestinal tract [19].

- Alginate-based multilayered gel microspheres: These pH-responsive systems with excellent thermal stability protect vitamin B2 and β-carotene from intestinal degradation [19].

Table 2: Formulation Strategies for BCS Class II and IV Drugs [13] [17] [18]

| Formulation Approach | Technology Type | Mechanism of Action | Example Drugs | Bioavailability Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micronization | Particle Engineering | Increased surface area | Griseofulvin, Sulfa drugs | Moderate improvement |

| Nanonization | Nanoparticle | Enhanced dissolution rate | Estradiol, Doxorubicin | Significant improvement (2-5 fold) |

| Solid Dispersions | Molecular Dispersion | Increased solubility and wettability | Various BCS Class II drugs | Variable (2-10 fold) |

| Amorphous Nanoparticles | Nanoparticulate | High drug load with rapid dissolution | BCS Class IV compounds | Comparable to ASD with higher drug load |

| Liposil Systems | Hybrid Nanoparticle | Gastric protection and controlled release | Ibrutinib | 3.12-fold increase |

| Lipid-Based Particles | Emulsion/Microemulsion | Solubilization and lymphatic uptake | Peptides/Proteins | Variable |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BCS Classification and Formulation Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro permeability assessment | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells for transport studies |

| Polymer Carriers | Solid dispersion formulation | PVPVA (copovidone), PVP, PEG, HPMC |

| Surfactants | Solubility enhancement | Tween 80, Sodium lauryl sulfate, Pluronic F-68 |

| Lipid Components | Liposomal and lipid-based formulations | Phosphatidylcholine, Cholesterol, Stearylamine |

| Silica Precursors | Nanoparticle stabilization | Tetraethyl orthosilicate for liposil formation |

| Biorelevant Media | Solubility and dissolution testing | FaSSIF, FeSSIF simulating intestinal fluids |

| Cryoprotectants | Freeze-drying processes | Trehalose, Sucrose for nanoparticle stabilization |

Regulatory Applications and Biowaiver Considerations

The BCS framework has significant regulatory implications, particularly through the biowaiver provision that allows waiver of in vivo bioequivalence studies under specific conditions [13] [14]. BCS-based biowaivers are currently applicable for immediate-release solid oral formulations containing BCS Class I drugs that exhibit rapid dissolution [13].

There is ongoing scientific discussion about extending biowaiver provisions to certain BCS Class III drugs and select BCS Class II compounds, particularly weak acids with pKa values ≤4.5 and intrinsic solubility ≥0.01 mg/mL [13]. These Class II drugs may demonstrate sufficient solubility at intestinal pH levels (approximately 6.5) and, with rapid dissolution characteristics, could be suitable candidates for biowaiver extension [13].

The regulatory application of BCS principles provides substantial benefits to drug development, including reduced development costs, faster approval times, and decreased human testing. However, barriers remain, including lack of international harmonization in regulatory standards and uncertainty in regulatory approval processes [14].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System continues to evolve as a critical tool in modern drug development, bridging fundamental science with practical formulation strategies. The ongoing refinement of BCS-based approaches, including the Developability Classification System and advanced delivery technologies, demonstrates the dynamic nature of this field.

Future directions in BCS applications include the development of more predictive in vitro models that better capture complex in vivo absorption processes, expansion of biowaiver criteria based on scientific advances, and continued innovation in formulation technologies for challenging BCS Class II and IV compounds. The integration of BCS principles with emerging technologies such as 3D printing, artificial intelligence in formulation design, and personalized medicine approaches will further enhance the role of BCS in optimizing drug development efficiency and success.

As pharmaceutical research continues to address increasingly challenging drug molecules with poor solubility and permeability characteristics, the BCS framework provides an essential foundation for rational development strategies aimed at enhancing bioavailability and therapeutic outcomes.

Current Challenges in Small-Molecule and Biologic Bioavailability

Bioavailability, defined as the fraction of an administered drug that reaches systemic circulation in an active form, remains a pivotal challenge in pharmaceutical development [20]. For small-molecule drugs, poor oral bioavailability contributes significantly to high attrition rates in clinical trials, with over 70% of drug candidates in development pipelines demonstrating poor aqueous solubility [21] [20]. Biologics, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), recombinant proteins, and nucleic acid-based therapies, face different but equally formidable challenges, with more than 95% still requiring parenteral administration due to their susceptibility to enzymatic degradation and poor permeability across biological barriers [22] [23]. This article examines the current challenges and innovative strategies in bioavailability enhancement for both small molecules and biologics, providing application notes and detailed experimental protocols to guide research in this critical field.

Quantitative Landscape of Bioavailability Challenges

The market and clinical landscape clearly illustrates the centrality of bioavailability challenges in pharmaceutical development. The following tables summarize key quantitative data driving research in this field.

Table 1: Market Dynamics of Small Molecules and Biologics Highlighting Bioavailability Challenges

| Parameter | Small Molecules | Biologics |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Value (2024) | $194.96 billion (API market) [24] | $348.03 billion (2022) [25] |

| Projected Market Value | $331.56 billion by 2034 [24] | $620.31 billion by 2032 [25] |

| Dominant Administration Route | Oral (~72% as oral solid dose) [24] | Parenteral (>95%) [22] |

| Key Bioavailability Limitation | Poor solubility (>70% of candidates) [20] | Enzymatic degradation & poor permeability [22] |

| Manufacturing Cost | ~$5 per pack [25] | ~$60 per pack [25] |

Table 2: Bioavailability Challenges by Drug Class and Current Enhancement Strategies

| Drug Category | Major Bioavailability Challenges | Promising Enhancement Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| BCS Class II/IV Small Molecules | Low aqueous solubility, dissolution rate-limited absorption [26] | Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS), lipid-based formulations, amorphous solid dispersions [20] [26] |

| Therapeutic Peptides | Rapid enzymatic degradation, poor membrane permeability, high first-pass metabolism [23] | Structural modification, nanocarriers, permeation enhancers, alternative delivery routes [23] |

| Biologics (mAbs, proteins) | Susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, large molecular size (>150 kDa), inability to cross epithelial barriers [22] | Non-parenteral delivery routes (oral, inhaled, transdermal), particle engineering, stabilization technologies [22] |

Advanced Formulation Strategies to Overcome Bioavailability Barriers

Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for Small Molecules

Lipid-based nanocarriers represent a breakthrough technology for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble small molecules classified under BCS Class II and IV [26]. These systems improve bioavailability through multiple mechanisms: enhanced solubilization, protection from degradation, facilitation of cellular uptake, and promotion of lymphatic transport that bypasses first-pass metabolism [21].

Application Note 3.1.1: Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SNEDDS) SNEDDS are isotropic mixtures of oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants that spontaneously form oil-in-water nanoemulsions upon mild agitation in aqueous media, such as the gastrointestinal fluids [26]. The nanoscale droplet size (typically <100 nm) provides a large surface area for drug absorption and enhances permeability through the intestinal mucosa. These systems are particularly valuable for lipophilic drugs whose absorption is dissolution-rate limited [26].

Protocol 3.1.2: Development and Optimization of SNEDDS for Poorly Soluble Drugs

Materials:

- Drug substance (BCS Class II or IV)

- Medium-chain triglycerides (e.g., Captex 355, Labrafac Lipophile)

- Non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween 80, Cremophor EL)

- Co-surfactants (e.g., PEG 400, Transcutol HP)

- Aqueous dissolution media (e.g., 0.1 N HCl, phosphate buffers)

Experimental Workflow:

Diagram: SNEDDS Development Workflow

Procedure:

- Component Screening: Determine the saturation solubility of the drug in various oils (5-10 types), surfactants (8-12 types), and co-surfactants (5-8 types). Select components demonstrating highest solubilization capacity.

- Pseudoternary Phase Diagram: Construct phase diagrams using varying ratios of oil, surfactant/co-surfactant mixture (Smix), and water. Identify the nanoemulsion region boundaries.

- Formulation Optimization: Utilize a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach with 2-3 factors (e.g., oil %, Smix ratio, drug loading) to optimize for droplet size, polydispersity index, and emulsification time.

- Emulsification Properties: Dilute 1 mL of SNEDDS formulation in 500 mL of 0.1 N HCl at 37°C with gentle stirring (50 rpm). Monitor emulsification time and resulting droplet size using dynamic light scattering.

- In Vitro Drug Release: Perform dissolution studies using USP Apparatus II (paddle method) at 50-75 rpm in 500-900 mL of appropriate dissolution media at 37±0.5°C. Analyze drug concentration at predetermined time points.

- Stability Assessment: Store optimized formulations at 40±2°C/75±5% RH for 3-6 months. Monitor physical appearance, drug content, and droplet size at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 6 months.

Polymeric Nanoparticles for Biologic Delivery

Polymeric nanoparticles provide a robust platform for protecting biologic therapeutics from enzymatic degradation and facilitating their transport across biological barriers [27]. These systems are particularly valuable for oral delivery of peptides and proteins, which typically exhibit bioavailability of less than 1% due to gastrointestinal degradation and poor permeability [23].

Application Note 3.2.1: PLGA-Based Nanoparticles for Sustained Release Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles enable controlled release of encapsulated biologics through polymer degradation and erosion mechanisms [27]. The release kinetics can be tuned by modifying the molecular weight, lactic to glycolic acid (LA/GA) ratio, and particle size [28]. PLGA degrades into lactic and glycolic acid, which are metabolized via natural biochemical pathways, ensuring biocompatibility [27].

Protocol 3.2.2: Double Emulsion Solvent Evaporation Method for Peptide Encapsulation

Materials:

- PLGA polymer (varying MW 10-100 kDa, LA/GA ratios 50:50-85:15)

- Peptide/protein drug (lyophilized)

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, 1-3% w/v)

- Dichloromethane (DCM) or ethyl acetate

- Primary emulsifier (e.g., phospholipids)

Experimental Workflow:

Diagram: Double Emulsion Method for Biologic Encapsulation

Procedure:

- Primary Emulsion Formation: Dissolve 50-100 mg PLGA in 2 mL organic solvent (DCM or ethyl acetate). Dissolve peptide in 0.2-0.5 mL aqueous solution (W1). Combine aqueous peptide solution with polymer solution and emulsify using probe sonication (30-60 seconds, 40-80 W) on ice bath to form W1/O emulsion.

- Secondary Emulsion: Add the primary emulsion to 4-10 mL of external aqueous phase (W2) containing 1-3% w/v PVA. Homogenize (5,000-15,000 rpm for 2-5 minutes) to form W1/O/W2 double emulsion.

- Solvent Evaporation: Stir the double emulsion continuously for 3-6 hours at room temperature to allow organic solvent evaporation and nanoparticle hardening.

- Particle Harvesting: Centrifuge nanoparticles at 15,000-25,000 × g for 20-30 minutes. Wash pellets 2-3 times with distilled water to remove excess emulsifier.

- Characterization: Determine particle size and zeta potential by dynamic light scattering. Assess morphology by SEM. Quantify drug loading and encapsulation efficiency via HPLC after nanoparticle dissolution.

- Release Kinetics: Incubate nanoparticles in release buffer (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C with gentle shaking. Collect samples at predetermined intervals and analyze drug content.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioavailability Enhancement Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Bioavailability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | PLGA, PLA, chitosan, gelatin [27] [28] | Form nanoparticle matrices for controlled drug release; degrade into biocompatible byproducts [27] |

| Lipid Matrix Materials | Medium-chain triglycerides, phospholipids, Glyceryl monooleate [26] | Create lipid nanocarriers that enhance solubilization and promote lymphatic transport [21] |

| Surfactants & Emulsifiers | Poloxamers, Tween series, PVA, Cremophor derivatives [26] | Stabilize nanoemulsions and improve membrane permeability [21] [26] |

| Permeation Enhancers | Sodium caprate, chitosan derivatives, fatty acids [23] | Temporarily disrupt epithelial tight junctions to facilitate drug absorption [22] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Aprotinin, pepstatin, trypsin inhibitors [23] | Protect peptide drugs from enzymatic degradation in GI tract [23] |

The future of bioavailability enhancement lies in the development of increasingly sophisticated, patient-centric delivery systems that can precisely control drug release kinetics and target specific tissues [27]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing this field by enabling predictive modeling of bioavailability parameters and accelerating the design of optimal formulation compositions [24] [27]. For small molecules, the convergence of nanocarrier technologies with 3D printing promises personalized dosage forms with tailored release profiles [20]. For biologics, innovations in non-parenteral delivery routes—particularly oral and inhaled formulations—represent the next frontier in making these transformative therapies more accessible and patient-friendly [22]. As these advanced technologies mature, they will progressively overcome the fundamental bioavailability challenges that have long constrained the development of both small molecules and biologics, ultimately expanding treatment options and improving patient care worldwide.

Innovative Delivery Technologies: From Nanocarriers to Smart Systems

Advanced Penetration Enhancement Technologies for Topical and Transdermal Delivery

The efficacy of topical and transdermal drug delivery is fundamentally constrained by the formidable barrier function of the skin, primarily governed by the stratum corneum (SC). This outermost layer, approximately 10–20 µm thick, consists of keratin-rich corneocytes embedded in a lipid-rich matrix, creating a 'brick-and-mortar' structure that significantly limits passive drug diffusion [29] [30]. Overcoming this barrier is a central challenge in dermatotherapy and transdermal delivery, driving the development of advanced penetration enhancement technologies. These technologies are strategically designed to temporarily and reversibly compromise the skin's barrier properties, thereby facilitating the delivery of a wider range of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), including hydrophilic compounds, macromolecules, and high-molecular-weight drugs, which traditionally exhibit poor skin permeability [29] [31]. The integration of these enhancement strategies is pivotal for improving drug bioavailability, achieving targeted delivery, and expanding the therapeutic potential of transdermal and topical routes, aligning with the overarching objective of enhancing bioavailability in drug delivery research [32] [33].

To rationally design penetration enhancement strategies, a thorough understanding of skin structure and penetration routes is essential. The skin's primary barrier, the SC, is a multilayered structure of corneocytes and intercellular lipids, limiting drug penetration primarily to molecules under 500 Da [34] [31]. Drug absorption occurs via two primary pathways: the transepidermal route, which can be transcellular (across corneocytes) or intercellular (through lipid domains), and the transappendageal route (via hair follicles and sweat glands) [29] [30]. The intercellular pathway through the lipid matrix is often the major route for passive diffusion, while the appendageal route can be significant for large or polar molecules [29]. The following diagram illustrates the structure of the skin and the primary pathways for drug penetration.

Classification and Mechanisms of Penetration Enhancement Technologies

Penetration enhancement technologies can be broadly categorized into chemical, physical, and carrier-based systems. Each category employs distinct mechanisms to temporarily overcome the skin barrier, facilitating improved drug delivery.

- Chemical Enhancers: These compounds interact with the SC's structural components to increase permeability. They may disrupt the highly organized lipid bilayers, extract intercellular lipids, alter keratin conformation within corneocytes, or improve drug partitioning into the SC [30]. Examples include sulfoxides (e.g., DMSO), fatty acids, alcohols, and terpenes [32] [30].

- Physical Enhancers: These methods use external energy or mechanical force to create conduits through the SC or actively drive molecules across it. This category includes microneedles, iontophoresis (low-level electrical current), sonophoresis (ultrasound), and electroporation (high-voltage pulses) [29] [35] [31].

- Carrier-Based Systems: Utilizing advanced formulation science, these systems employ nanoscale carriers like liposomes, transferosomes, ethosomes, nanoemulsions, and polymeric nanoparticles. They enhance drug solubility, protect labile APIs, and can facilitate transport through the skin via diffusion or by fusing with skin lipids [34] [31].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Major Penetration Enhancement Technologies

| Technology Category | Typical Size/Parameters | Key Mechanism of Action | Molecular Weight Suitability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Enhancers [30] | N/A | Lipid fluidization, protein denaturation, & partitioning effects | Typically < 500 Da [34] | Formulation simplicity, cost-effective |

| Microneedles [29] | 50-900 µm in height | Physical bypass of stratum corneum by creating microchannels | Up to macromolecules (e.g., vaccines, proteins) [29] [34] | Painless, avoids first-pass metabolism, high bioavailability |

| Iontophoresis [35] [36] | Low current (0.1-0.5 mA/cm²) | Electromigration & electroosmosis to drive charged molecules | Low to moderate | Controlled delivery, suitable for charged molecules |

| Nanocarriers [34] [31] | 10-200 nm | Enhanced drug solubilization, fusion with skin lipids, & targeted delivery | Low to high (depending on carrier) | Improved drug stability, sustained release, reduced irritation |

| Sonophoresis [35] | Ultrasound frequencies | Cavitation disrupting lipid structure of stratum corneum | Low to moderate | Non-invasive, can be combined with other methods |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Skin Permeation Study Using Franz Diffusion Cells

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for evaluating the permeation enhancement efficacy of chemical enhancers or nanocarrier systems using excised human or mammalian skin [32].

Materials:

- Franz Diffusion Cells: Standard vertical cells (e.g., with 9 mm orifice diameter, 5-7 mL receptor volume).

- Skin Membrane: Excised human skin (surgical discard), porcine ear skin, or synthetic membranes like Strat-M.

- Receptor Fluid: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or another physiologically relevant buffer, maintained at 37°C.

- Test Formulation: Drug solution containing the chemical penetration enhancer(s) or nanocarrier system.

- HPLC System: Or other validated analytical instrument for quantifying drug concentration.

Procedure:

- Skin Preparation: Carefully separate the full-thickness skin into epidermis and dermis using heat separation or dermatoming to a thickness of 200-400 µm. Inspect for integrity.

- Cell Assembly: Mount the skin membrane between the donor and receptor compartments of the Franz cell, ensuring the SC faces the donor side. Clamp securely to prevent leakage.

- Receptor Phase Preparation: Fill the receptor chamber with degassed receptor fluid, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped at the skin-receptor fluid interface.

- Equilibration: Allow the system to equilibrate for 30-60 minutes with stirring (e.g., 600 rpm) to achieve a skin surface temperature of 32°C ± 1°C.

- Application of Formulation: Apply a finite dose (e.g., 5-10 µL/cm²) of the test formulation to the center of the donor chamber. Seal the donor chamber to prevent evaporation.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 h), withdraw aliquots (e.g., 300 µL) from the receptor compartment and replace immediately with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed receptor fluid.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze the samples using a validated HPLC-UV method to determine the cumulative amount of drug permeated per unit area.

- Data Analysis: Plot cumulative amount permeated (Q) vs. time. Calculate steady-state flux (Jss) from the slope of the linear portion and the lag time from the x-intercept.

Protocol 2: Fabrication and Evaluation of Dissolving Microneedles for Macromolecule Delivery

This protocol details the fabrication of dissolving microneedles (MNs) using a micromolding technique for the transdermal delivery of macromolecules, such as proteins or nucleic acids [29] [34].

Materials:

- Microneedle Mold: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMSe) or other polymer master mold with desired needle geometry (e.g., 500 µm height, 200 µm base width).

- Polymer Solution: Aqueous solution of a biocompatible polymer such as Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, 15-20% w/v) or Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP).

- Macromolecule API: The therapeutic agent to be loaded (e.g., a protein, peptide, or antigen).

- Centrifuge: For facilitating the filling of mold cavities.

- Analytical Balance, Vacuum Desiccator.

Procedure:

- Master Mold Fabrication (if required): Create a master mold using laser ablation or photolithography. For most research purposes, commercial molds are suitable.

- Drug-Polymer Mixture Preparation: Dissolve the water-soluble polymer (e.g., PVA) in distilled water. Gently mix the macromolecule API into the polymer solution under low shear to prevent denaturation or aggregation.

- Mold Filling: Carefully apply the drug-polymer mixture onto the MN mold surface. Place the assembly in a centrifuge and spin at 3000-5000 rpm for 10-20 minutes to drive the formulation into the needle cavities and remove air bubbles.

- Drying and Curing: Allow the filled mold to dry at room temperature for 24 hours or under mild vacuum (e.g., in a desiccator) to facilitate solvent removal and solidification.

- Backing Layer Formation: Once the needles are dry, pour a more viscous, inert polymer solution (e.g., 30% w/v PVA) over the mold to form a solid backing layer. Dry thoroughly.

- Demolding: Carefully peel the finished MN array from the mold. Visually inspect for completeness and structural integrity using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

- In Vitro Release/Diffusion Study: Apply the MN patch to excised skin (as in Protocol 1). After a short application time (e.g., 15-30 min) to allow needle dissolution, proceed with a standard Franz cell assay to quantify macromolecule permeation.

The following workflow summarizes the key steps in the fabrication and evaluation of dissolving microneedles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Penetration Enhancement Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Penetration Enhancers [32] [30] | Temporarily disrupt stratum corneum structure to increase permeability. | Terpenes (e.g., limonene), Fatty Acids (e.g., oleic acid), Surfactants (e.g., polysorbate 80). High purity (>98%). |

| Biocompatible Polymers [29] [34] | Form the matrix for dissolving microneedles and hydrogel-based formulations. | Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA, Mw 85,000-124,000), Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K30). |

| Lipid Nanocarrier Components [34] [31] | Constituents for formulating advanced vesicular systems like liposomes and transferosomes. | Phosphatidylcholine (soybean or egg lecithin), Cholesterol, Edge-active agents (e.g., sodium cholate). |

| Franz Diffusion Cell System [32] | Gold-standard apparatus for in vitro assessment of drug permeation kinetics. | Glass vertical cells, 9 mm orifice, maintained at 32°C with magnetic stirring. |

| Synthetic Membrane | Reproducible and consistent model for initial screening of formulations. | Strat-M (Merck Millipore) or polysulfone membranes. |

| Excised Skin | Biologically relevant barrier for pre-clinical testing. | Human (ethical approval required), porcine, or murine skin, dermatomed to 200-400 µm. |

Advanced and Emerging Technologies

The field of penetration enhancement is rapidly evolving, with several cutting-edge technologies showing significant promise for enhancing the bioavailability of challenging APIs.

- Stimuli-Responsive Systems: These "smart" systems release drugs in response to specific physiological or external triggers, such as pH, temperature, or enzymes. For instance, thermoresponsive hydrogels can release drugs upon skin contact, while pH-sensitive nanocarriers target inflamed skin or acne-prone areas [35]. This on-demand release profile improves therapeutic efficacy while minimizing potential side effects.

- Synergistic Combination Strategies: Research increasingly focuses on combining different enhancement modalities to achieve a synergistic effect. A prominent example is the combination of microneedles with iontophoresis. The microneedles create initial microchannels, and iontophoresis then actively drives charged macromolecules through these conduits, significantly enhancing penetration depth and efficiency compared to either method alone [36] [31].

- 3D-Printed Microneedles: Additive manufacturing allows for the precise fabrication of microneedles with customized geometries, densities, and compositions. This enables tailored drug dosing, controlled release kinetics, and the incorporation of multiple APIs within a single patch. Recent studies have successfully demonstrated 3D-printed MNs for the delivery of cannabinoids, showcasing their potential for personalized medicine [36].

- Next-Generation Nanocarriers: Beyond conventional liposomes, new vesicular systems are being developed. Ethosomes, enriched with ethanol, exhibit high flexibility and enhanced skin penetration ability [36] [34]. Transferosomes are ultra-deformable vesicles that can squeeze through intercellular lipid pathways, making them highly effective for transdermal delivery [31]. These systems are particularly advantageous for stabilizing labile compounds like isoliquiritigenin and improving their dermal bioavailability [33].

Table 3: Emerging Technologies and Their Applications

| Emerging Technology | Mechanism | Potential Application | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimuli-Responsive Systems [35] | Drug release triggered by pH, enzymes, or temperature. | Acne treatment, infected wound healing, inflammatory skin diseases. | Advanced R&D / Early Clinical |

| Combined Microneedle + Iontophoresis [36] [31] | Microneedles create channels; iontophoresis drives molecules through them. | Delivery of peptides, proteins, and vaccines. | Preclinical / Proof-of-Concept |

| 3D-Printed Microneedles [36] | High-precision fabrication of customized needle architectures. | Personalized dosing, combination therapies, complex release profiles. | Advanced R&D |

| Advanced Nanocarriers (e.g., Ethosomes, Transferosomes) [34] [31] | Highly deformable vesicles that penetrate intact SC. | Delivery of antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, and macromolecules. | Some formulations in market / Clinical |

Advanced penetration enhancement technologies represent a cornerstone in the ongoing pursuit of improved bioavailability for topical and transdermal therapeutics. From well-established chemical enhancers to innovative physical devices and sophisticated nanocarrier systems, the technological landscape offers a diverse toolkit for formulation scientists. The strategic selection and combination of these technologies, guided by a deep understanding of the drug's properties and the target disease, enable the effective delivery of previously undeliverable drugs. Future progress will likely be driven by trends towards personalization, smart stimulus-responsive systems, and the refinement of combination strategies to achieve safer, more effective, and patient-friendly transdermal and topical medicines.

The efficacy of many active pharmaceutical ingredients and phyto-bioactive compounds is often hampered by inherent physicochemical limitations, including low aqueous solubility, poor permeability, and inadequate stability, which collectively result in low bioavailability [37] [38]. Nanocarrier systems have emerged as a transformative solution to these challenges, engineered to enhance the therapeutic index of drugs by improving their solubility, providing targeted delivery, enabling controlled release, and minimizing off-target effects [37] [39]. Among the most extensively investigated nanocarriers are liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs), and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). These systems adeptly navigate biological barriers, alter the biodistribution of encapsulated agents, and facilitate the accumulation of drugs at the desired site of action [37] [39]. Framed within research on delivery systems for enhanced bioavailability, this document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for these three pivotal nanocarrier systems, serving the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Application Notes and Performance Data

The following section summarizes the key characteristics, performance data, and primary applications of liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and solid lipid nanoparticles, providing a comparative overview to guide formulation selection.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Nanocarrier Systems for Enhanced Bioavailability

| Parameter | Liposomes | Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs) | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Size Range | 30 nm - several micrometers [39] | Nanoscale (specific range varies by polymer and method) [40] | 30 - 1000 nm (120-200 nm ideal for prolonged circulation) [38] |

| Core Composition | Aqueous interior and phospholipid bilayers [41] [39] | Biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLGA, Chitosan) [42] [43] | Solid lipid matrix (e.g., triglycerides, fatty acids, waxes) [38] [44] |

| Drug Encapsulation | Hydrophilic drugs (aqueous core); Hydrophobic drugs (lipid bilayer) [41] [39] | Entrapment within polymer matrix or adsorption onto surface [42] | Incorporation into solid lipid core; models: drug-enriched shell, core, or homogeneous matrix [38] |

| Key Bioavailability Advantages | Enhances absorption of poorly soluble drugs; protects from degradation; enables passive/active targeting [41] [45] | Superior stability; controlled and sustained release; tunable properties; stimuli-responsive release [42] [40] [43] | High biocompatibility; improves chemical stability and aqueous solubility of actives; protects from degradation [38] [44] |

| Reported Bioavailability Enhancement (in vivo) | Apigenin: 1.5-fold; Carvedilol: 2.3-fold; Fenofibrate: 5.1-fold in dogs [41] | Varies widely based on drug, polymer, and targeting ligands. Demonstrated enhanced tumor penetration and mucosal delivery [42] [43] | Hydrochlorothiazide (BCS Class IV): 3.6-fold increase in ex vivo permeability; significant improvement in in vivo diuretic activity [44] |

| Dominant Administration Routes | Intravenous, oral, ocular, inhalation [39] | Oral, ocular, intravenous, targeted cancer therapy [42] [43] | Oral, parenteral, ocular, topical [38] |

Liposomes

Liposomes are self-assembling, spherical vesicles consisting of one or more phospholipid bilayers enclosing an aqueous core, structurally analogous to cell membranes [41] [39]. This unique architecture allows for the simultaneous encapsulation of hydrophilic drugs within the aqueous interior and hydrophobic drugs within the lipid membrane [41]. Their primary application in bioavailability enhancement lies in solubilizing water-insoluble drugs, shielding encapsulated compounds from degradation in the gastrointestinal tract, and enhancing permeability across epithelial cell membranes [41]. They have demonstrated significant success in improving the oral bioavailability of BCS Class II drugs, as evidenced by in vivo studies. For instance, liposomal formulations of carvedilol and fenofibrate showed 2.3-fold and 5.1-fold increases in bioavailability, respectively, compared to free drug suspensions [41]. Clinically, several liposomal formulations (e.g., Doxil, AmBisome) have received regulatory approval, validating their utility in enhancing drug delivery [39].

Polymeric Nanoparticles