Advanced Strategies for Bioavailability Enhancement of Bioactive Compounds: From Formulation Technologies to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies to overcome the critical challenge of low bioavailability in bioactive compounds and small-molecule drugs.

Advanced Strategies for Bioavailability Enhancement of Bioactive Compounds: From Formulation Technologies to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies to overcome the critical challenge of low bioavailability in bioactive compounds and small-molecule drugs. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current scientific knowledge across four key areas: the fundamental physicochemical and biological barriers governing absorption; innovative formulation technologies like solid dispersions, lipid-based systems, and nanocarriers; practical troubleshooting and optimization approaches for development pipelines; and the essential regulatory frameworks and validation methods for proving bioequivalence and clinical efficacy. The content leverages the latest research and market trends to serve as a strategic guide for enhancing the therapeutic potential of promising molecules.

Understanding Bioavailability: The Foundation for Effective Drug Development

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental definition of bioavailability in a clinical pharmacology context? Bioavailability (denoted as F) is defined as the fraction of an administered dose of a drug that reaches the systemic circulation unaltered, and the rate at which this occurs [1] [2]. It is a core component of the pharmacokinetics paradigm (ABCD: Administration, Bioavailability, Clearance, Distribution) and is crucial for determining the correct dosage to achieve a therapeutic effect [1].

2. How is bioavailability quantitatively measured and calculated? The most reliable measure of a drug's bioavailability is the Area Under the plasma concentration-time Curve (AUC) [1] [2]. Bioavailability is typically calculated by comparing the AUC of a drug administered via a specific route (e.g., oral) to the AUC of the same drug dose administered intravenously (IV), which is assumed to have 100% bioavailability [1].

- Absolute Bioavailability is determined by the formula: F = AUC~oral~ / AUC~IV~ [1] [3].

- Relative Bioavailability compares the bioavailability of two different dosage forms of the same drug (e.g., tablet vs. syrup) [4].

3. What is the key difference between the "rate" and "extent" of bioavailability? These are two distinct but critical parameters:

- Extent: Refers to the total amount of the active drug that reaches systemic circulation. This is measured by the AUC [2] [3].

- Rate: Refers to how quickly the drug enters the systemic circulation. This is measured by the peak time (T~max~), which is the time taken to reach the maximum plasma concentration (C~max~) [4] [2]. A slower absorption results in a later T~max~.

4. Why does an intravenously administered drug have 100% bioavailability? Intravenous (IV) administration delivers the drug directly into the systemic circulation, completely bypassing absorption barriers and first-pass metabolism. Therefore, the entire dose is immediately and completely available to the body [1].

5. What are the most common physiological causes of low oral bioavailability? The primary causes are related to barriers encountered before a drug reaches systemic circulation:

- First-Pass Metabolism: After oral absorption, drugs pass through the liver via the portal system, where they can be extensively metabolized by enzymes (e.g., Cytochrome P450) before reaching the systemic circulation [1] [2].

- Poor Solubility and Permeability: A drug must dissolve in the gastrointestinal (GI) fluids and be able to penetrate the intestinal epithelial membrane. Poorly water-soluble or slowly absorbed drugs often have low bioavailability [5] [2].

- Insufficient Time for Absorption: If a drug does not dissolve readily or cannot penetrate the membrane quickly, it may pass through the GI tract without adequate absorption [2].

6. How can drug formulation strategies overcome poor bioavailability? Strategic formulation decisions can dramatically improve bioavailability, especially for poorly soluble drugs [6] [5]. Key techniques include:

- Particle Size Reduction: Micronization or nanonization to increase surface area and dissolution rate [6] [5].

- Salt Formation: Creating salt forms of ionizable compounds to enhance aqueous solubility [5].

- Amorphous Solid Dispersions: Dispersing the drug in an amorphous state within a polymer matrix to increase apparent solubility [5].

- Lipid-Based Delivery Systems: Using nanoemulsions or liposomes to improve solubility and absorption [6].

- Co-crystals: Combining the drug with non-toxic coformers to alter crystal packing and improve solubility [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Bioavailability Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Irregular or Uninterpretable Melt Curves in Thermal Shift Assays (TSAs)

TSAs, like Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF), are used to study drug-target binding by detecting shifts in a protein's melting temperature [7].

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Compound Interference: The test compound itself may be fluorescent or may interact with the fluorescent dye used in the assay (e.g., SyproOrange). This can cause irregular curve shapes [7].

- Solution: Run a control well with the compound and dye but no protein to identify intrinsic fluorescence or compound-dye interactions [7].

- Buffer Incompatibility: Certain buffer additives (e.g., detergents, viscosity enhancers) can increase background fluorescence or interfere with the dye [7].

- Solution: Optimize the buffer system and ensure compatibility with the fluorescent dye. Refer to dye-specific incompatibility guides [7].

- Protein Purity and Stability: The target protein must be stable, soluble, and not aggregated at ambient temperature in the chosen buffer for reliable melting curves [7].

- Solution: Characterize protein stability in different buffers and include appropriate controls.

- Compound Interference: The test compound itself may be fluorescent or may interact with the fluorescent dye used in the assay (e.g., SyproOrange). This can cause irregular curve shapes [7].

Issue 2: Low Oral Bioavailability in In Vivo Studies

When an orally dosed drug shows lower-than-expected systemic exposure in animal or human studies.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- First-Pass Metabolism: High metabolic extraction in the liver or intestinal wall [1] [2].

- Poor Solubility/Dissolution: The drug fails to dissolve in the GI tract, limiting absorption [5] [2].

- Efflux Transporters: Active transport of the drug back into the gut lumen by transporters like P-glycoprotein [1] [3].

- Solution: Investigate the use of pharmaceutical excipients that can inhibit these transporters or perform structural modification of the drug candidate to avoid recognition by the transporter [1].

Issue 3: No Observed Target Engagement in Cellular Assays (e.g., CETSA)

In a Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA), a test compound does not show a stabilization or destabilization effect on the target protein in whole cells [7].

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Poor Cell Membrane Permeability: The compound cannot efficiently cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target [7].

- Insufficient Compound Incubation Time: The incubation period may be too short for the compound to be taken up by the cells and bind its target [7].

- Solution: Optimize the incubation time to ensure adequate cellular uptake and binding, while avoiding phenotypic effects that could complicate the readout [7].

- Compound Instability in Cell Culture: The compound may be degraded in the culture medium before it can act [7].

- Solution: Assess the stability of the compound in the assay medium.

Quantitative Data for Bioavailability Assessment

Table 1: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Assessing Bioavailability [1] [4] [2]

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation & Impact on Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under the Curve) | Total exposure of the body to the active drug over time. | Directly proportional to the extent of bioavailability. A larger AUC indicates greater total drug absorption. |

| C~max~ (Max Concentration) | The peak plasma concentration achieved after administration. | Impacts the intensity of both therapeutic and toxic effects. A high C~max~ may lead to toxicity. |

| T~max~ (Time to C~max~) | Time taken to reach the maximum plasma concentration. | Indicates the rate of absorption. A short T~max~ suggests rapid onset of action. |

| Absolute Bioavailability (F) | Fraction of drug reaching systemic circulation compared to an IV dose. | Determines the dosing requirements. A drug with low F requires a higher oral dose to match the IV effect. |

Table 2: Strategies to Enhance Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drugs [6] [5]

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size Reduction (Nanonization) | Increases surface area to enhance dissolution rate. | BCS Class II drugs (High Permeability, Low Solubility). |

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions | Creates a high-energy amorphous form with higher apparent solubility than the crystalline form. | Drugs with very low solubility and high crystallinity. |

| Lipid-Based Delivery Systems | Solubilizes the drug in lipid matrices, facilitating absorption via lymphatic transport. | Highly lipophilic drugs. |

| Salt Formation | Improves aqueous solubility for ionizable compounds. | Drugs with acidic or basic functional groups. |

| Cyclodextrin Complexation | Encapsulates the drug molecule to increase solubility and stability. | Molecules suitable for host-guest inclusion complexes. |

Experimental Protocols for Bioavailability Research

Protocol 1: In Vitro Dissolution Testing

Objective: To simulate and assess the release of a drug from its dosage form under standardized conditions, which is a critical indicator of potential in vivo performance [6].

Methodology:

- Apparatus: Use a USP-compliant dissolution apparatus (e.g., paddle or basket type).

- Dissolution Medium: Select a suitable medium (e.g., pH 1.2 HCl buffer for gastric fluid, pH 6.8 phosphate buffer for intestinal fluid) maintained at 37±0.5 °C [6].

- Procedure: Place the dosage form (tablet, capsule) in the vessel containing the medium. Operate the apparatus at a specified rotational speed (e.g., 50-75 rpm).

- Sampling: Withdraw aliquots of the medium at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 minutes).

- Analysis: Filter the samples and analyze the drug concentration using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV). Calculate the percentage of drug dissolved at each time point.

- Data Interpretation: Plot the dissolution profile (% released vs. time). Compare the profile to a reference standard or specifications to evaluate performance.

Protocol 2: Determining Absolute Bioavailability in a Preclinical Model

Objective: To quantify the fraction of an orally administered dose that reaches the systemic circulation by comparing it to an intravenous dose [1] [2].

Methodology:

- Study Design: A crossover design is ideal, where the same animal receives both the oral (PO) and intravenous (IV) formulation after a suitable washout period.

- Dosing: Administer the drug at the same dose level via both PO and IV routes. The IV dose must be administered as a solution or suspension that ensures complete availability.

- Blood Sampling: Collect serial blood samples at multiple time points after both doses (e.g., pre-dose, 5, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours).

- Bioanalysis: Process plasma from blood samples and determine the drug concentration in each sample using a validated bioanalytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: For both routes, calculate the AUC from time zero to infinity (AUC~0-∞~).

- Calculation: Determine Absolute Bioavailability (F) using the formula: F (%) = (AUC~PO~ / AUC~IV~) × (Dose~IV~ / Dose~PO~) × 100 [1] [3].

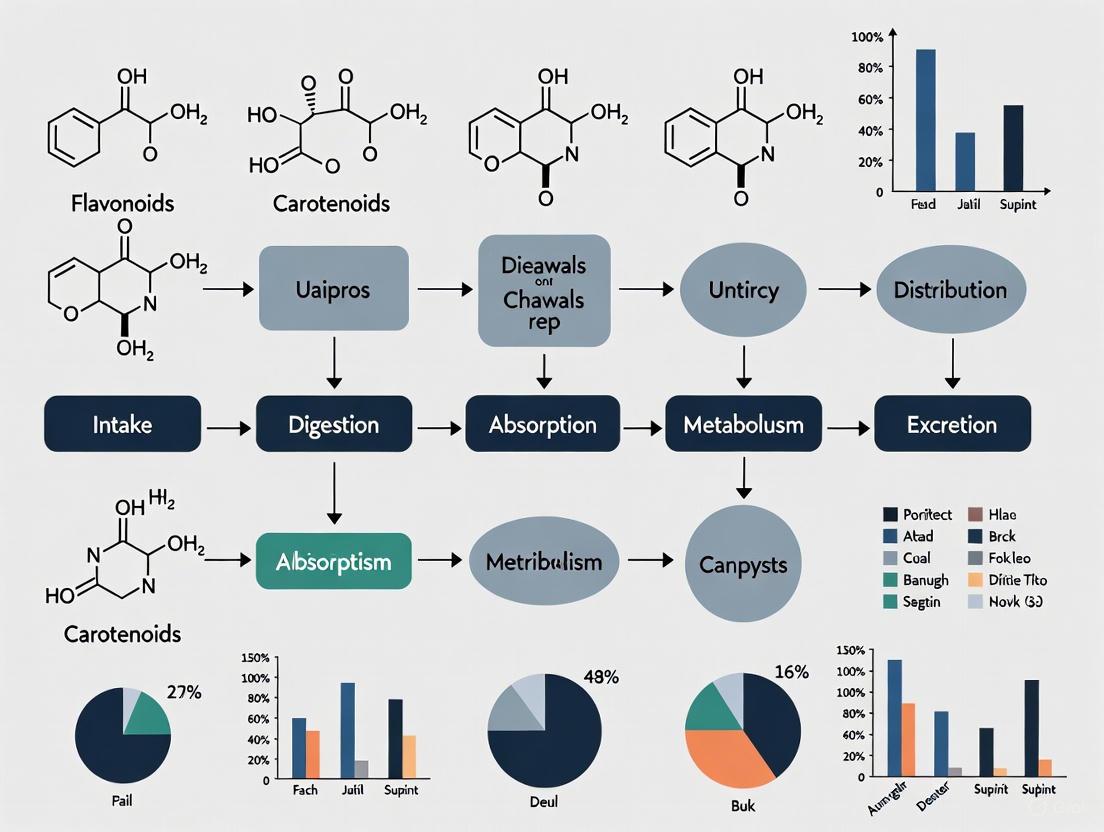

Visualization: The Journey of an Oral Drug and Key Bioavailability Barriers

The following diagram illustrates the pathway and major barriers an orally administered drug faces before reaching systemic circulation, which directly impact its bioavailability.

Diagram 1: Oral Drug Bioavailability Pathway. This workflow highlights key barriers like dissolution, enzymatic degradation, efflux transporters, and first-pass metabolism that reduce the amount of drug reaching systemic circulation. [1] [2] [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Key Bioavailability Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | An in vitro model of the human intestinal epithelium used to predict drug permeability and absorption [5]. | Studying passive diffusion and active transporter effects (e.g., P-gp efflux). |

| Polarity-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., SyproOrange) | Used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to detect protein unfolding by binding to exposed hydrophobic residues [7]. | Identifying drug-target interactions through thermal stability shifts. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Buffers mimicking the pH and composition of gastric and intestinal fluids for in vitro dissolution testing [6]. | Assessing drug release and stability in a physiologically relevant environment. |

| Cytochrome P450 Isoenzyme Assays | Enzyme systems used to study the metabolic stability of a drug and identify specific metabolic pathways [1] [5]. | Evaluating the potential for first-pass metabolism and drug-drug interactions. |

| Polymer Carriers (e.g., HPMC, PVPVA) | Used to create amorphous solid dispersions, maintaining the drug in a high-energy state to enhance solubility [6] [5]. | Formulation strategy for BCS Class II/IV drugs with poor aqueous solubility. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Gold-standard bioanalytical instrumentation for the sensitive and specific quantification of drug concentrations in complex biological matrices (e.g., plasma) [4]. | Generating pharmacokinetic data (AUC, C~max~, T~max~) from in vivo studies. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between logP and logD, and when should each be used?

- Answer:

logPdescribes the partition coefficient of a neutral (unionized) compound between octanol and water, representing its inherent lipophilicity. In contrast,logDis the distribution coefficient at a specific pH, accounting for all forms of the compound (ionized and unionized). You should uselogPfor neutral compounds andlogDfor ionizable compounds, aslogDprovides a more accurate picture of a compound's behavior under physiological pH conditions [8]. For compounds with ionizable sites,logDis essential for predicting solubility and membrane permeability accurately [8].

- Answer:

FAQ 2: During early-stage development, my compound shows poor aqueous solubility. What are the first parameters I should investigate and potentially optimize?

- Answer: The first parameters to investigate are

lipophilicity (logP/logD)andmolecular size/weight. High lipophilicity (logP > 5) often correlates with low aqueous solubility [9]. According to Lipinski's Rule of Five, a molecular weight exceeding 500 Da can also negatively impact solubility and permeability [8]. Your initial optimization efforts should focus on modifying the molecular structure to lower logP/logD, perhaps by introducing polar functional groups, while being mindful of the molecular size [9].

- Answer: The first parameters to investigate are

FAQ 3: How does the ionization state (pKa) of my compound influence its lipophilicity and solubility?

- Answer: The ionization state, determined by the compound's

pKaand the environmental pH, directly controls the balance betweensolubilityandlipophilicity[9] [8]. A charged species (ionized form) will have significantly higheraqueous solubilityand a lowerlogD(more hydrophilic). The unionized form has higherlipophilicity (logP)and bettermembrane permeability. ThelogDcurve, which plots logD against pH, visually represents this relationship and is critical for predicting behavior in different parts of the GI tract [8].

- Answer: The ionization state, determined by the compound's

Troubleshooting Guides

- Problem 1: Inconsistent or inaccurate determination of lipophilicity (logP/logD).

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Highly variable logD values across different pH levels. | Normal behavior for ionizable compounds; logD is pH-dependent [8]. | Characterize the full logD-pH profile instead of a single value. Use automated potentiometric titration for accuracy [9]. |

| Results do not align with in vitro permeability data. | logP was measured instead of physiologically relevant logD. | Switch to measuring logD at pH 6.5 for jejunal permeability prediction [8]. Ensure the assay buffers mimic physiological pH. |

| Low throughput is a bottleneck for screening. | Using traditional, manual shake-flask methods. | Implement automated instrumentation like the SiriusT3, which can perform up to 80 lipophilicity assays per day with sub-milligram quantities [9]. |

- Problem 2: Poor aqueous solubility leading to low bioavailability.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low kinetic and intrinsic solubility. | High molecular lipophilicity (excessively high logP) [9]. | Medify the chemical structure to reduce logP by adding ionizable or polar groups. Consider salt formation for ionizable compounds [9]. |

| Compound precipitates during dissolution. | Formation of unstable supersaturated states. | Use the CheqSol method to experimentally determine the extent and duration of supersaturation, which can guide formulation strategies [9]. |

| Poor solubility across various biological pH. | Unfavorable ionization profile (pKa). | Determine the pKa and model the solubility-pH profile. This can identify the optimal pH for solubility and guide salt or prodrug design [9]. |

- Problem 3: Inefficient isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from natural extracts.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty isolating the specific bioactive compound from a complex mixture. | Standard separation techniques are not target-directed. | Employ TLC bio-autography. This technique combines chromatographic separation with in situ activity determination to directly locate antimicrobial compounds on a TLC plate [10]. |

| Isolated compound loses activity upon purification. | The bioactive component may be a specific polymorphic form with higher solubility. | Perform solid-state characterization using techniques like X-ray Diffraction (XRD) or Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to identify and select the optimal polymorph [9]. |

| Low yield of the target bioactive compound. | Inefficient extraction method. | Utilize modern extraction techniques like Microwave-Assisted Extraction or Pressurized-Liquid Extraction, which can improve extraction efficiency and selectivity while reducing solvent use and degradation [10]. |

| Property | Target Range for Oral Drugs (Rule of 5) | Extended Range (Beyond Rule of 5) | Rationale & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ≤ 500 Da | < 1000 Da | Affects transport across membranes; larger size can hinder diffusion [8]. |

| logP | < 5 | -2 to 10 | Governs membrane permeability and distribution; high values linked to toxicity and poor solubility [8]. |

| logD (at pH 7.4) | Not specified in Ro5 | Critical to assess | Determines actual lipophilicity at physiological pH; crucial for ionizable compounds [8]. |

| H-Bond Donors | ≤ 5 | ≤ 6 | Impacts permeability through H-bonding with water and membrane components [8]. |

| H-Bond Acceptors | ≤ 10 | ≤ 15 | Influences solubility and permeability [8]. |

- Table 2: Common Experimental Techniques for Property Determination

| Property | Common Experimental Techniques | Key Advantages | Throughput & Sample Need |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | CheqSol, Shake-Flask, HPLC | CheqSol provides kinetic and intrinsic solubility and identifies supersaturation [9]. | Automated systems (e.g., SiriusT3) enable high-throughput with sub-milligram samples [9]. |

| Lipophilicity (logP/logD) | Shake-Flask, Potentiometric Titration (SiriusT3) | Potentiometric titration is automated and provides a full logD-pH profile [9]. | Up to 80 assays/day; < 2 hours for a logD profile; sub-milligram sample [9]. |

| pKa | Potentiometric Titration, Spectrophotometric | Determines ionization constant critical for understanding solubility and permeability [9]. | Automated titration takes <6 minutes per analysis [9]. |

| Identification/Isolation | TLC, HPLC, HPLC/MS, FTIR | TLC bioautography links chemical separation to biological activity for targeted isolation [10]. | Varies by method; HPLC/MS is robust and widely used for complex mixtures [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Intrinsic Solubility and Supersaturation Using the CheqSol Method

- Principle: This method rapidly determines intrinsic solubility by inducing a transition between supersaturated and undersaturated states through controlled addition of acid or base, while monitoring pH [9].

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Dissolve a small quantity (sub-milligram) of the compound in a water-miscible solvent like DMSO to create a stock solution.

- Initial Supersaturation: Add a known aliquot of the stock solution to a aqueous buffer, creating a supersaturated solution.

- Titration and Monitoring: Use an automated titrator (e.g., SiriusT3) to titrate with acid or base while continuously monitoring the pH. The software tracks the rate of pH change.

- Equilibrium Point: The titration continues until the solution reaches a state where the pH is stable, indicating equilibrium between the dissolved and solid drug (the intrinsic solubility).

- Data Analysis: The software calculates the intrinsic solubility and provides data on the kinetics of supersaturation, including the maximum supersaturation ratio and its persistence time [9].

Protocol 2: Measuring Lipophilicity (logD-pH Profile) via Automated Potentiometric Titration

- Principle: This technique measures the pKa of a compound in both water and water-octanol mixtures. The difference in pKa values between the two solvents is used to calculate the logP and subsequently the entire logD-pH profile [9].

- Procedure:

- Aqueous Titration: Dissolve the compound in a ionic strength-adjusted water solution. Perform a potentiometric titration from low to high pH (or vice-versa) to determine the aqueous pKa(s).

- Octanol-Water Titration: Add water-saturated octanol to the system and perform the titration again. The compound will partition into the octanol as it becomes neutral, shifting the apparent pKa.

- Data Processing: The instrument's software (e.g., SiriusT3 Refinement) analyzes the two titration curves. It calculates the logP from the pKa shift and then generates the full logD-pH profile [9].

- Output: The key deliverable is a graph of logD versus pH, which shows how the compound's lipophilicity changes across the physiological pH range [8].

Protocol 3: Bioassay-Guided Isolation Using TLC-Bioautography

- Principle: This method separates compounds via Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) and then uses an agar overlay inoculated with a test microorganism to visually locate antimicrobial compounds on the plate through zones of inhibition [10].

- Procedure:

- Separation: Spot the crude plant or natural extract on a TLC plate and develop it using an appropriate mobile phase.

- Drying: Ensure the plate is completely dry to remove all residual solvent, which could inhibit microbial growth.

- Inoculation: Overlay the TLC plate with a thin layer of molten nutrient agar that has been seeded with a log-phase culture of the target microorganism (e.g., S. aureus or E. coli).

- Incubation: Incub the plate in a humid chamber at the optimal temperature for the microorganism for a specified period (e.g., 24 hours).

- Visualization: After incubation, visualize the zones of inhibition (clear zones where microbial growth is prevented) against a background of confluent growth.

- Isolation: Correlate the inhibition zones with the Rf values from a reference TLC plate. The silica from the corresponding areas on a preparative TLC plate can be scraped off and eluted with a solvent like methanol to isolate the active compound for further characterization (e.g., by HPLC or LC-MS) [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

- Table 3: Key Reagents and Instruments for Physicochemical Characterization

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| SiriusT3 Instrument | An automated platform for high-throughput determination of pKa, logP/logD, and solubility, using both potentiometric and spectrophotometric methods [9]. |

| n-Octanol & Aqueous Buffers | The two immiscible phases used in the shake-flask method and as reference systems in automated instruments for measuring partition/distribution coefficients [8]. |

| HPLC/MS Systems | Used for analyzing purity, stability, and for the identification and characterization of isolated bioactive compounds from complex mixtures [10]. |

| TLC Plates & Phytochemical Spray Reagents | Used for quick, low-cost separation of mixture components and for visualizing specific phytochemical classes (e.g., alkaloids, flavonoids) through color reactions [10]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Determines thermal stability and identifies polymorphic forms of a compound, which is critical for understanding solubility and bioavailability [9]. |

Relationships and Workflows

Diagram 1: Property Interplay in Bioavailability

Diagram 2: Bioactive Compound Discovery Workflow

For researchers focused on improving the bioavailability of bioactive compounds, biological barriers represent the most significant challenge to therapeutic efficacy. These barriers—comprising cellular interfaces, enzymatic systems, and efflux transporters—protect the body from xenobiotics but simultaneously limit the absorption and distribution of therapeutic agents [11]. The passage of a compound across biological barriers depends on its physico-chemical properties, formulation, degree of protein binding, and concentration gradient [11]. This technical resource addresses key experimental challenges in predicting and overcoming these barriers, with particular emphasis on practical methodologies for assessing and modulating permeability, metabolic stability, and efflux transporter activity.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Addressing Variable Permeability Results

Q: Our Caco-2 permeability assays show high variability between replicates. What could be causing this inconsistency?

A: Caco-2 variability typically stems from three main sources: monolayer integrity, cell passage number, and assay conditions. First, always validate monolayer integrity by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) before experiments; values should exceed 1000 Ω·cm², with optimal ranges between 2000-4000 Ω·cm² [12]. Second, control for passage number effects by using cells within consistent passages (e.g., P32-P72); extended passage can alter transporter expression and barrier function [12]. Third, ensure consistent culture duration—a standardized 10-day culture period improves differentiation and produces more reproducible results [12].

Q: How can we distinguish between passive diffusion and transporter-mediated flux in our absorption studies?

A: Implement selective inhibition protocols. For passive diffusion assessment, conduct experiments at 4°C to inhibit active transport processes or use specific transporter inhibitors. To identify specific transporter contributions, employ chemical inhibitors (e.g., zosuquidar for P-gp, Ko143 for BCRP, MK571 for MRP2) or genetic approaches using transporter-knockout cell lines [12]. Always include positive control substrates for each transporter (e.g., esitropram sulfate for BCRP, sulfasalazine for MRP2) to validate your inhibition approach [12].

FAQ: Managing Efflux Transporter Interference

Q: Our lead compound shows excellent solubility but poor oral bioavailability. Could efflux transporters be responsible?

A: Absolutely. ATP-dependent efflux transporters (P-gp, BCRP, MRP2) expressed on the apical membrane of intestinal epithelial cells significantly limit oral bioavailability for many compounds [13]. These transporters recognize structurally diverse compounds: P-gp prefers neutral and positively charged hydrophobic compounds; MRP2 transports hydrophilic conjugates; while BCRP recognizes relatively hydrophilic anticancer agents [13]. To assess this, compare bidirectional transport (A-B vs B-A) in Caco-2 or MDCK models. An efflux ratio (B-A/A-B) >2 suggests significant transporter involvement [13].

Q: What experimental approaches can identify efflux transporter inhibition without using probe substrates?

A: Recent advances enable detection of transporter inhibition through intracellular metabolomic signatures. Using targeted LC-MS, researchers have identified specific metabolite patterns associated with P-gp, BCRP, and MRP2 inhibition [12]. For P-gp inhibition, 11 intracellular metabolites show consistent changes; BCRP inhibition alters 4 metabolites; while MRP2 inhibition affects 9 metabolites [12]. This approach provides additional information on transporter inhibition in standard Caco-2 assays without compromising throughput.

FAQ: Overcoming Compound Degradation

Q: Our peptide compound is unstable in gastrointestinal fluids. What formulation strategies can protect it during transit?

A: Several advanced formulation approaches can address this challenge. Nano-delivery systems (niosomes, lipid nanoparticles) physically protect peptides from enzymatic degradation [14]. Chemical modification (e.g., Stapled Peptide technology) enhances stability against proteases [15]. Permeability enhancers (e.g., Intravail technology for transmucosal absorption) can significantly improve stability and absorption [15]. For oral delivery, consider enteric coatings that release compounds in the intestine rather than the stomach, or lipid-based systems that provide a protective environment [16] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Standardized Caco-2 Permeability and Efflux Assay

Purpose: To evaluate intestinal permeability and identify efflux transporter substrates.

Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Seed Caco-2 cells at 2×10⁴ cells/well on 96-well transwell plates (0.4 µM pore size). Culture for 10 days in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, changing media every 2-3 days [12].

- TEER Validation: Measure TEER before experimentation using an epithelial voltohmmer. Accept only monolayers with TEER values >1000 Ω·cm² (optimal 2000-4000 Ω·cm²) [12].

- Bidirectional Transport:

- Prepare test compound in HBSS (pH 7.4) at relevant concentrations (typically 1-10 µM).

- For apical-to-basolateral (A-B) transport: Add compound to apical chamber, sample from basolateral chamber over 120 minutes.

- For basolateral-to-apical (B-A) transport: Add compound to basolateral chamber, sample from apical chamber over 120 minutes.

- Maintain at 37°C with gentle agitation [12] [13].

- Inhibition Studies: Co-incubate with selective inhibitors: 5 µM zosuquidar (P-gp), 10 µM Ko143 (BCRP), or 200 µM MK571 (MRP2) in both compartments [12].

- Sample Analysis: Quantify compound concentration in samples using LC-MS/MS. Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) and efflux ratio (B-A/A-B).

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Include positive controls for each transporter to validate system performance.

- For low-solubility compounds, use concentrations below solubility limits and verify stability throughout assay.

- Ensure pH stability throughout experiment as pH shifts can affect compound ionization and permeability.

Efflux Transporter Inhibition Screening via Metabolomics

Purpose: To identify potential efflux transporter inhibitors using intracellular metabolic signatures.

Protocol:

- Cell Treatment: Culture Caco-2 cells as described above. On day 10, treat with test compound (typically 1-10 µM) or vehicle control (1% DMSO in HBSS) for 60-120 minutes [12].

- Metabolite Extraction: Wash cells twice with cold PBS, then extract intracellular metabolites using 80% methanol containing internal standards. Scrape cells, vortex vigorously, and centrifuge at 14,000×g for 15 minutes at 4°C [12].

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze supernatant using targeted LC-MS/MS with a focused panel of metabolites known to respond to transporter inhibition. Use a C18 column with gradient elution (water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [12].

- Data Analysis: Normalize metabolite levels to protein content and internal standards. Compare patterns to established signatures for P-gp (11 metabolites), BCRP (4 metabolites), and MRP2 (9 metabolites) [12].

- Validation: Confirm findings with traditional probe substrate assays for positive hits.

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Efflux Transporter Inhibitors and Experimental Concentrations

| Transporter | Inhibitor | Working Concentration | Positive Control Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-gp (MDR1) | Zosuquidar | 5 µM | Digoxin, Loperamide |

| Valspodar | 50 nM | ||

| Ritonavir | 10 µM | ||

| BCRP (ABCG2) | Ko143 | 10 µM | Esitropram sulfate, Methotrexate |

| Fumitremorgin C | 5 µM | ||

| Novobiocin | 30 µM | ||

| MRP2 (ABCC2) | MK571 | 200 µM | Sulfasalazine, Glutathione conjugates |

| Benzbromarone | 66.7 µM |

Data compiled from [12] and [13]

Table 2: Commercial Formulation Technologies for Bioavailability Enhancement

| Technology | Mechanism | Representative Products/Trade Names |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Dispersion | Maintains drug in amorphous state | ISOPTIN-SRE (Verapamil), GRIS-PEG (Griseofulvin) |

| Lipid-Based Systems | Enhances solubility & lymphatic transport | Fenoglide (Fenofibrate), Norvir (Ritonavir) |

| Nanoparticle Formulation | Increases surface area for dissolution | Invega Sustenna (Paliperidone), Rapamune (Sirolimus) |

| Cyclodextrin Complexation | Molecular encapsulation for solubility | Sporanox (Itraconazole), Geodon (Ziprasidone) |

| Polymer-Based Matrices | Controls release & enhances stability | INCIVEK (Telaprevir), ONMEL (Itraconazole) |

Data compiled from [16] and [15]

Visual Experimental Workflows

Transporter Inhibition Screening Workflow

Inhibition Screening Process

Intestinal Absorption Pathways

Compound Absorption Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Absorption Studies

| Reagent/System | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Model for intestinal permeability screening | Use passages 32-72; requires 10-day differentiation for optimal transporter expression [12] |

| Transwell Plates (0.4 µM) | Support for cell monolayer growth | Polycarbonate membranes preferred for compound compatibility [12] |

| TEER Measurement System | Monolayer integrity validation | Essential pre-experiment quality control; values >2000 Ω·cm² indicate tight junctions [12] |

| Selective Transporter Inhibitors | Mechanistic studies | Zosuquidar (P-gp), Ko143 (BCRP), MK571 (MRP2) at established concentrations [12] |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Quantitative compound & metabolite analysis | Enables permeability calculations & metabolomic signature detection [12] |

| Transporter-Knockout Cells | Control for specific transporter effects | Available through commercial providers (e.g., SOLVO Biotechnology) [12] |

| HBSS Buffer (pH 7.4) | Physiological transport medium | Maintain pH stability throughout experiments [12] |

Advanced Technical Notes

Emerging Technologies in Bioavailability Enhancement

The field of bioavailability enhancement continues to evolve with several promising technologies. Lipid-based delivery systems enhance solubility and facilitate lymphatic transport, bypassing first-pass metabolism [15]. Amorphous solid dispersions stabilize drugs in high-energy states, significantly improving dissolution rates for BCS Class II compounds [16] [17]. Nanoparticle formulations (including nanocrystals and polymeric nanoparticles) increase surface area and enable targeted delivery [16] [18]. Additionally, advanced penetration enhancers for transdermal delivery—including fatty acid derivatives, terpenes, and physical methods like iontophoresis—are gaining traction for their ability to reversibly modify barrier function [19].

Regulatory Considerations

When developing formulations to overcome biological barriers, regulatory agencies provide specific guidance on bioavailability enhancement approaches. The FDA and EMA have established pathways for novel formulation technologies, particularly when bioequivalence studies demonstrate improved performance [15] [17]. For efflux transporter studies, regulatory guidelines emphasize evaluating potential drug-drug interactions during development, requiring assessment against key transporters (P-gp, BCRP) using established in vitro systems [12] [13].

BCS Framework FAQs: Core Principles and Regulatory Application

FAQ 1: What is the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) and what is its primary purpose in drug development?

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) is an advanced, science-based framework that categorizes drug substances based on key biopharmaceutical properties: solubility, intestinal permeability, and dissolution [20]. Its primary objective is to evaluate the in vivo performance (bioavailability) of drug products based on in vitro data, thereby serving as a regulatory tool that can, under certain conditions, replace costly and time-consuming bioequivalence studies in humans (biowaiver) [20] [21]. For formulation scientists, the BCS provides a rational approach to designing novel dosage forms, moving away from empirical methods towards more predictive, modernistic strategies [20].

FAQ 2: How are drugs classified within the BCS framework?

The BCS classifies drugs into four main categories based on their aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability [20]. The following table summarizes the defining characteristics, key challenges, and examples for each class.

Table 1: The Four Classes of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Rate-Limiting Step for Absorption | Key Challenge | Example Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Gastric emptying | None (Ideal) | Acetaminophen, Verapamil [20] [22] |

| Class II | Low | High | Drug dissolution / Solubility | Low and variable bioavailability | Voriconazole, Griseofulvin, Lemborexant [20] [22] |

| Class III | High | Low | Permeability across the intestinal membrane | Limited absorption | Cimetidine, Metformin [20] |

| Class IV | Low | Low | A combination of solubility and permeability | Poor and variable absorption | Voxelotor, Fedratinib (in certain conditions) [21] [22] |

FAQ 3: What are the specific criteria for a drug to be considered "highly soluble" or "highly permeable"?

The regulatory definitions for the key BCS parameters are as follows [20]:

- High Solubility: A drug substance is considered highly soluble when the highest single therapeutic dose is completely soluble in 250 mL or less of aqueous media across a pH range of 1.0 to 6.8 (or up to 7.5 for some agencies) at 37°C.

- High Permeability: A drug substance is considered highly permeable when the extent of intestinal absorption in humans is determined to be 90% or more of the administered dose, based on mass balance studies or in comparison to an intravenous reference dose.

- Rapid Dissolution: A drug product is considered to have rapid dissolution when 85% or more of the labeled amount of drug substance dissolves within 30 minutes using standard USP apparatus (e.g., basket at 100 rpm or paddle at 50 rpm) in 900 mL of various buffer media.

FAQ 4: What is a BCS-based biowaiver and which drug classes are typically eligible?

A biowaiver is an official exemption from conducting in vivo bioequivalence studies. For immediate-release (IR) solid oral dosage forms, a biowaiver can be granted based on demonstrating that the product meets BCS-based criteria for solubility, permeability, and dissolution [21].

- BCS Class I: These drugs (high solubility, high permeability) with rapid dissolution are the strongest candidates for biowaivers [21].

- BCS Class III: Drugs with high solubility and low permeability are also considered for biowaivers by major regulatory agencies, provided they exhibit very rapid dissolution [21].

- BCS Class II & IV: Traditionally, these classes were not eligible for biowaivers due to absorption challenges. However, the World Health Organization has broadened its scope and now considers biowaivers for all BCS classes on a case-by-case basis, provided sufficient evidence is presented [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming BCS Class II Drug Challenges

Challenge: The bioavailability of our BCS Class II drug candidate is unacceptably low and highly variable due to its poor solubility.

Solution Strategy: The primary goal is to enhance the apparent solubility and/or dissolution rate of the drug. This can be achieved through various physical and chemical modification techniques.

Table 2: Techniques to Enhance Solubility and Bioavailability of BCS Class II Drugs

| Technique Category | Specific Method | Brief Description & Mechanism | Research Reagent / Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size Reduction | Micronization | Reduces particle size to 1-10 microns, increasing surface area for dissolution [20]. | Jet Mill, Fluid Energy Mill |

| Nanoionization | Reduces drug particles to nanocrystals (200-600 nm), dramatically increasing saturation solubility [20]. | High-Pressure Homogenizer | |

| Solid-State Modification | Amorphous Solid Dispersions | Creates a high-energy, amorphous form of the drug dispersed in a polymer matrix, enhancing solubility [20]. | Povidone, Polyethylene Glycol |

| Polymorphs / Solvates | Utilizes metastable crystalline forms or anhydrates which have higher solubility than their stable counterparts [20]. | Solvents for Recrystallization | |

| Complexation | Cyclodextrin Inclusion | The drug molecule is entrapped in the hydrophobic cavity of cyclodextrin, improving aqueous solubility [20]. | Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin |

| Novel Formulation Systems | Microemulsion / Nanoemulsion | Uses oil, surfactant, and co-surfactant to solubilize the drug in fine dispersions for improved absorption [20]. | Surfactants (Tween 80, Pluronic F-68) |

| Lipid-Based Systems | Incorporates the drug into lipids, surfactants, and co-solvents to keep the drug in a solubilized state in the GI tract [20]. | Medium-Chain Triglycerides |

Experimental Protocol: Preparation of a Solid Dispersion via the Hot-Melt Method

Objective: To create a solid dispersion of a BCS Class II drug in a hydrophilic polymer carrier to enhance its dissolution rate.

Materials:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): The BCS Class II drug.

- Carrier: Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 6000 or Povidone (PVP K30).

- Equipment: Heating mantle with magnetic stirrer, aluminum dish, desiccator, mortar and pestle.

Methodology:

- Weighing: Accurately weigh the drug and the carrier in a predetermined ratio (e.g., 1:5).

- Melting: Transfer the physical mixture to an aluminum dish and heat directly on a heating mantle until both components melt, forming a clear, homogenous melt. Maintain constant, gentle stirring.

- Solidification: Rapidly cool the molten mixture by placing the dish on an ice bath while continuing to stir until the mass solidifies completely.

- Size Reduction: Break the solidified mass, crush it in a mortar, and pass it through a sieve to obtain a uniform powder.

- Storage: Store the final solid dispersion in a desiccator at room temperature until further use [20].

Validation: The success of the protocol can be validated by conducting an in vitro dissolution study comparing the solid dispersion against the pure API, expecting a significant increase in the dissolution rate for the solid dispersion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BCS Characterization and Formulation

| Reagent / Material | Function in BCS Research |

|---|---|

| USP Dissolution Apparatus 1 & 2 | Standard equipment for determining drug dissolution profiles in 900 mL of various buffer media (e.g., 0.1 N HCl, pH 4.5, pH 6.8 buffers) [20]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Lines | In vitro model of the human intestinal epithelium used for predicting passive drug permeability [20]. |

| Povidone (PVP) | A common hydrophilic polymer used as a carrier in amorphous solid dispersions to inhibit crystallization and enhance solubility [20]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Sodium Lauryl Sulfate) | Used in dissolution media to simulate sink conditions for poorly soluble drugs or as formulation components to improve wettability and solubility [20]. |

| High-Pressure Homogenizer | Key equipment for producing drug nanocrystals via top-down approaches like nanoionization [20]. |

| Cyclodextrins (e.g., HP-β-CD) | Oligosaccharides that form inclusion complexes with drug molecules, effectively increasing their apparent solubility and stability [20]. |

Decision Framework for Oral Drug Formulation

The following workflow outlines a strategic approach for formulating drug candidates based on their BCS classification, with a focus on overcoming absorption challenges. This process integrates BCS principles with the refined Developability Classification System (rDCS), which provides a more nuanced, animal-free risk assessment to guide formulation design [22].

Workflow Title: BCS-Driven Formulation Strategy

This diagram emphasizes that while BCS provides the initial classification, leveraging the refined Developability Classification System (rDCS) can offer a more detailed risk profile. For instance, some BCS Class II drugs may be reclassified as rDCS Class I, indicating a lower development risk and suitability for conventional formulations, while others may be stratified into higher-risk subclasses (IIa/IIb) requiring specific solubility-enhancement strategies [22].

FAQs: Core Principles and Regulatory Standards

What is the fundamental bioequivalence assumption and how does it link bioavailability to clinical outcomes?

The fundamental bioequivalence (BE) assumption states that if two drug products (e.g., a generic and a reference product) demonstrate comparable rate and extent of absorption (as measured by pharmacokinetic parameters AUC and Cmax), they will produce the same clinical effect (safety and efficacy) in patients [23]. This principle allows regulators to approve generic drugs without repeating extensive clinical trials, relying instead on demonstrated bioavailability equivalence.

What are the standard regulatory acceptance criteria for establishing bioequivalence?

For most drugs, average bioequivalence (ABE) requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (Test/Reference) for both AUC (extent of absorption) and Cmax (rate of absorption) falls entirely within the 80-125% range [23]. This is typically demonstrated through crossover studies in healthy volunteers.

How do bioequivalence requirements differ for highly variable drugs (HVDs)?

For highly variable drugs (within-subject variability >30%), the Reference-scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) approach is employed [23]. This method widens the acceptance limits proportionally to the reference product's variability, making BE demonstration feasible without impractically large sample sizes. Key requirements include:

- Replicated crossover designs where subjects receive the reference product multiple times

- Minimum 24 subjects for FDA studies

- Point estimate of geometric mean ratio must remain within 80-125%

What recent international harmonization efforts affect bioequivalence testing?

The ICH M13 series represents a major global harmonization initiative. ICH M13A (effective January 2025) addresses BE for immediate-release solid oral dosage forms, while the draft M13B guidance describes criteria for waiving BE studies for additional strengths when one strength has demonstrated BE in vivo [24] [25]. These guidelines aim to standardize BE requirements across regulatory jurisdictions.

Troubleshooting Common Bioequivalence Study Issues

Problem: High within-subject variability causing failure to demonstrate bioequivalence

Solution: Implement Reference-scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) approach [23]

- Protocol Modification: Employ replicated crossover designs (3-period: RRT, RTR, TRR or 4-period: RTRT, TRTR)

- Statistical Adjustment: Scale bioequivalence limits based on reference product variability (SWR)

- Regulatory Compliance: Pre-specify RSABE approach in protocol before study initiation

- Sample Size Consideration: Ensure adequate sample size (minimum 24 subjects for FDA)

Problem: Uncertain sample size for achieving sufficient statistical power

Solution: Utilize sample size calculation tools with appropriate parameters [26]

- Key Inputs: Within-subject CV%, expected Geometric Mean Ratio (GMR), BE limits (typically 80-125%)

- Study Design Selection: Choose between 2x2 crossover, replicated crossover, or parallel designs based on drug characteristics

- Power Target: Set statistical power at 80% or higher with alpha typically at 5%

- Online Resources: Use specialized calculators (e.g., powerTOST package) for reliable estimates

Problem: Determining when clinical endpoint BE studies are necessary

Solution: Follow FDA tiered approach for different product types [27]

- Tier 1: Blood level BE studies preferred when feasible

- Tier 2: Pharmacologic endpoint studies for drugs with directly measurable pharmacological effects

- Tier 3: Clinical endpoint studies when neither Tier 1 nor Tier 2 approaches are possible

- Biowaiver Eligibility: Certain products (IV solutions, oral solutions, topical solutions for local effect) may qualify for biowaivers based on Q1/Q2 sameness

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioequivalence Studies

Table: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for Bioequivalence Research

| Item/Category | Function/Purpose | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Bioanalytical Method Validation [27] | Quantify drug concentrations in biological matrices | FDA Guidance #145 compliance; validation for precision, accuracy, selectivity |

| Phoenix WinNonlin [23] | Statistical analysis of BE data using RSABE | FDA/EMA-compliant templates for replicate designs; partial & full replicate support |

| Replicated Crossover Design [23] | Account for high within-subject variability | 3-period (TRR, RTR, RRT) or 4-period (TRTR, RTRT) designs |

| Sample Size Calculators [26] | Determine optimal subject numbers | powerTOST-based; parameters: CV%, GMR, BE limits, target power, alpha |

| Biowaiver Documentation [27] [25] | Justify in vivo BE study waivers | Q1/Q2 qualitative/quantitative sameness evidence; physicochemical comparison |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Two-Period Crossover Bioequivalence Study Protocol

- Study Design: Randomized, two-period, two-treatment, single-dose crossover with adequate washout period

- Subjects: Healthy volunteers (typically n=24-36) meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Dosing: Administration of test and reference products under fasting/fed conditions as specified

- Blood Sampling: Serial blood collection over sufficient time span to characterize complete PK profile

- Bioanalysis: Validated method for drug quantification in plasma/serum

- PK Analysis: Non-compartmental analysis to determine AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, and Cmax

- Statistical Analysis: ANOVA on log-transformed parameters; calculation of 90% CI for T/R ratio

Replicated Crossover Design for Highly Variable Drugs [23]

- Design Selection: Choose 3-period or 4-period replicated design based on expected variability

- Reference Repetition: Ensure each subject receives reference product at least twice

- Within-Subject Variability Calculation: Determine SWR (within-subject standard deviation of reference)

- RSABE Application Criteria: Apply when SWR ≥ 0.294 (CV ≥ 30%)

- Statistical Analysis: Use scaling approach per FDA or EMA guidelines with point estimate constraint

Biowaiver Application Protocol for Additional Strengths [25]

- Reference Product: Identify Reference Listed Drug with demonstrated BE

- Strength proportionality: Demonstrate linear pharmacokinetics across strengths

- Formulation Similarity: Show same qualitative and quantitative composition (Q1/Q2)

- In Vitro Dissolution: Conduct comparative dissolution studies per regulatory requirements

- Documentation: Submit detailed justification with formulation comparison data

Bioequivalence Establishment Workflows

Regulatory Decision Pathways for Highly Variable Drugs

Regulatory Comparison Table: FDA vs. EMA Bioequivalence Approaches

Table: Comparative Bioequivalence Requirements for Highly Variable Drugs

| Parameter | Agency | Low Variability (SWR < 0.294) | High Variability (SWR ≥ 0.294) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | FDA | Standard ABE (CI 80-125%) | RSABE permitted; CI can be widened; Point estimate within 80-125% |

| EMA | Standard ABE (CI 80-125%) | Standard ABE (CI 80-125%) only | |

| Cmax | FDA | Standard ABE (CI 80-125%) | RSABE permitted; CI can be widened; Point estimate within 80-125% |

| EMA | Standard ABE (CI 80-125%) | RSABE permitted; CI can be widened up to 70-143%; Point estimate within 80-125% | |

| Study Design | FDA | Standard 2x2 crossover or replicated | Replicated crossover required |

| EMA | Standard 2x2 crossover or replicated | Replicated crossover required | |

| Minimum Sample Size | FDA | Not specified | 24 subjects |

| EMA | Not specified | Not specified |

Table: RSABE Acceptance Range Widening at Different Variability Levels

| CVWR (%) | SWR | EMA RSABE Limits | FDA RSABE Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | — | ABE method (80-125%) | ABE method (80-125%) |

| 30 | 0.294 | 80.00 – 125.00 | 76.94 – 129.97 |

| 35 | 0.340 | 77.23 – 129.48 | 73.82 – 135.47 |

| 40 | 0.385 | 74.62 – 134.02 | 70.89 – 141.06 |

| 45 | 0.429 | 72.15 – 138.59 | 68.15 – 146.74 |

| 50 | 0.472 | 69.84 – 143.19 | 65.58 – 152.48 |

| 60 | 0.555 | 69.84 – 143.19 (max widening) | 60.95 – 164.08 |

Cutting-Edge Formulation Technologies for Bioavailability Enhancement

In modern pharmaceutical development, a significant challenge is the poor aqueous solubility of new chemical entities (NCEs), which limits their bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. It is estimated that 40% to 90% of drugs in development can be characterized as poorly water-soluble, falling into BCS Class II or IV [28] [29]. To address this, amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) have emerged as a reliable strategy. Among the various production techniques, hot-melt extrusion (HME) and spray drying are two of the most prevalent and effective methods used to produce ASDs [30]. These technologies enhance the dissolution rate and oral bioavailability of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) by stabilizing them in a high-energy, amorphous form within a polymer matrix [31]. This technical support center provides a foundational guide for researchers and scientists, offering troubleshooting advice and detailed methodologies for implementing these critical bioavailability enhancement technologies.

Hot-melt extrusion and spray drying are enabling technologies designed to transform poorly soluble crystalline APIs into amorphous solid dispersions.

Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) is a continuous, solvent-free process that uses thermal and mechanical energy to mix and melt a blend of API and polymer, forming a homogeneous amorphous matrix [32] [28]. It is a mature technology known for its robust and scalable nature [33] [34].

Spray Drying is a continuous solvent evaporation process that transforms a liquid feed solution (containing API and polymer dissolved in a volatile solvent) into a dry, powdered ASD through atomization and rapid drying [35] [29]. It is particularly valued for its flexibility in polymer selection and applicability to heat-sensitive compounds [29].

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of these core technologies:

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Hot-Melt Extrusion and Spray Drying

| Feature | Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) | Spray Drying |

|---|---|---|

| Process Nature | Continuous, solvent-free [32] [34] | Continuous, solvent-based [35] [29] |

| Key Mechanism | Melting and mixing via heat and shear [32] | Rapid solvent evaporation from atomized droplets [29] |

| Typical Polymer Selection | Thermoplastic polymers (e.g., PVP VA64) [36] | Broad range, including cellulose-based polymers [35] [29] |

| Drug Loading | Can be limited by API-polymer miscibility [35] | Can achieve higher drug loading [31] |

| Scalability | Readily scalable; equipment is compact [34] | Scalable, but equipment is larger and complex [34] |

| Relative Bioavailability Improvement | Demonstrated significant enhancement (e.g., Oleanolic acid) [36] | Typically 3 to 15-fold improvement [33] |

| Key Advantage | Superior stability against recrystallization [30] | Higher intrinsic dissolution rates (IDR) [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful formulation of ASDs requires careful selection of excipients and solvents. The following table details key materials and their functions in developing solid dispersions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Solid Dispersions

| Item | Function / Role | Examples & Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Carriers | Stabilize the amorphous API, inhibit recrystallization, and enhance dissolution [35] [31]. | PVP K30: Offers strong drug-polymer interactions, enhancing both dissolution rate and stability [30].HPMC E5: A commonly used cellulose derivative [30].Soluplus: A long-chain polymer with strong solubilizing capabilities [35].PVP/VA 64 (copovidone): Can stabilize formulations via H-bonding, inhibiting recrystallization [35]. |

| Solvents | Dissolve the API and polymer to create a homogeneous feed solution for spray drying [35]. | Acetone, Methanol, Ethanol: Volatile organic solvents with low boiling points, preferred for faster drying and smaller particle size [35] [29]. Selection is based on solvation power and safety. |

| Surfactants | Further improve wettability and bioavailability, can be added to the formulation blend [28]. | Often incorporated as additional components in HME formulations to aid in dispersion and dissolution [28]. |

| Model Compounds | Poorly soluble APIs used for proof-of-concept and method development. | Indomethacin: A widely used model compound for poorly soluble drugs [30].Oleanolic Acid: A BCS Class IV model compound whose bioavailability was enhanced via HME [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol for Preparing ASDs via Hot-Melt Extrusion

This protocol outlines the methodology for enhancing the bioavailability of a poorly soluble compound, such as Oleanolic Acid, using Hot-Melt Extrusion [36].

1. Objective: To prepare an amorphous solid dispersion of a poorly soluble API (e.g., Oleanolic Acid) using HME to enhance its dissolution rate and oral bioavailability.

2. Materials:

- API (e.g., Oleanolic Acid) [36].

- Polymer (e.g., PVP VA64) [36].

- Twin-screw hot-melt extruder (co-rotating preferred for pharmaceuticals) [32].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Pre-blending. The API and the polymer (e.g., PVP VA64) are physically mixed in a predetermined ratio to ensure a homogeneous powder blend before feeding into the extruder [28] [36].

- Step 2: Extrusion. The powder blend is fed into the extruder. Critical process parameters (CPPs) to control include:

- Barrel Temperature Profile: Set above the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the polymer-API blend but below the degradation temperature of the components [32].

- Screw Speed (RPM): Controls the residence time and shear rate, typically ranging from 100 to 500 rpm [32].

- Feed Rate: Must be optimized to ensure consistent output and filling of the screw channels [32].

- Step 3: Cooling & Collection. The molten extrudate is forced through a die and cooled on a conveyor belt to form a solid ribbon or strand [32].

- Step 4: Downstream Processing. The cooled extrudate is milled or ground into granules or powders suitable for subsequent dosage form development, such as compression into tablets or filling into capsules [28].

4. Characterization: The final ASD should be characterized using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) to confirm the conversion to the amorphous state [36]. An in vitro dissolution test and in vivo pharmacokinetic study in animal models (e.g., rats) are conducted to validate the enhancement in dissolution rate and bioavailability [36].

Protocol for Preparing ASDs via Spray Drying

This protocol is adapted from general spray drying processes and tailored for small-scale development using limited API, as described in the literature [35] [29].

1. Objective: To produce an amorphous solid dispersion of a poorly soluble API using spray drying to improve its solubility and bioavailability.

2. Materials:

- API and suitable polymer (see Table 2).

- Volatile organic solvent (e.g., acetone, methanol, or mixture) [35] [29].

- Small-scale spray dryer (e.g., Büchi Nano Spray Dryer B-90 or ProCepT 4M8-TriX for milligram-scale studies) [29].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Feed Solution Preparation. The API and polymer are dissolved in a common volatile solvent to create a homogeneous feed solution. The total solid content is dictated by solubility and solution viscosity [35].

- Step 2: Atomization. The feed solution is pumped into a spray nozzle (e.g., piezoelectric, ultrasonic, or pressure nozzle) and atomized into a fine mist of droplets inside the drying chamber [35] [29].

- Step 3: Drying. The droplets are contacted with hot drying gas (e.g., nitrogen). The inlet air temperature (typically 50°C to 200°C) is controlled to rapidly evaporate the solvent [35] [31].

- Step 4: Collection. The dried solid particles are separated from the gas stream and collected using a cyclone or an electrostatic collector [35] [29]. The outlet temperature is a critical response parameter influenced by the inlet temperature and feed rate.

4. Characterization: The resulting spray-dried dispersion (SDD) powder is characterized for particle size and morphology, amorphization (using PXRD), residual solvent content, and in vitro dissolution performance [35] [31].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Hot-Melt Extrusion Troubleshooting

Q1: During HME, my API is degrading. What could be the cause and how can I prevent this?

- A: Thermal degradation is a primary concern. To mitigate this:

- Lower Processing Temperature: Optimize the barrel temperature profile to the minimum required to form a homogeneous melt. Using a polymer with a lower glass transition temperature (Tg) can facilitate this [28].

- Optimize Screw Speed and Residence Time: Reducing the screw speed can shorten the time the API is exposed to high temperatures [32].

- Formulation Screening: Conduct thorough pre-formulation screening to identify APIs with sufficient thermal stability for HME or consider alternative polymers that process at lower temperatures [28].

Q2: My HME extrudate shows signs of incomplete mixing or phase separation. What should I check?

- A: Inhomogeneity can compromise the stability and performance of the ASD.

- Screw Configuration: Ensure the screw design includes mixing elements (e.g., kneading blocks) to provide adequate distributive and dispersive mixing [32].

- Feed Rate Consistency: A fluctuating feed rate can lead to poor mixing. Verify that the powder feeder is calibrated and operating consistently [32].

- API-Polymer Miscibility: Re-evaluate the compatibility between the API and polymer. The drug should be miscible with the polymer at the processing temperature to form a single-phase system [35].

Spray Drying Troubleshooting

Q1: The yield of my spray-dried product is very low, especially at a small scale. How can I improve it?

- A: Low yield is a common challenge in lab-scale spray drying.

- Optimize Collector Type: For small-scale dryers like the Büchi B-90, the electrostatic collector is highly efficient for sub-5µm particles. Ensure it is functioning correctly [29].

- Adjust Process Parameters: High powder loss can occur due to wall adhesion. Optimizing the inlet/outlet temperature, spray rate, and the use of anti-static agents can reduce electrostatic adherence [35].

- Check Nozzle/Capillary: For small-scale units, ensure the spray mesh or nozzle is not clogged and is appropriate for the solution's viscosity and desired particle size [29].

Q2: My spray-dried powder is sticky, agglomerating, or has high residual solvent. What steps can I take?

- A: These issues are often linked to the drying efficiency and formulation.

- Increase Outlet Temperature: A higher outlet temperature indicates more efficient drying. This can be achieved by increasing the inlet temperature or reducing the feed rate [35]. However, balance is needed to avoid degrading the API.

- Implement Secondary Drying: A dedicated secondary drying step (e.g., using a fluid bed dryer or vacuum oven) is often necessary to reduce residual solvents to levels compliant with ICH guidelines [34] [31].

- Reformulate: Consider adjusting the polymer type or ratio in your formulation. Some polymers act as better moisture barriers or provide better drying characteristics [35].

General ASD Troubleshooting

Q1: My ASD is recrystallizing upon storage or during dissolution. How can I improve its physical stability?

- A: Recrystallization is a critical failure mode for ASDs.

- Polymer Selection: Choose a polymer that has strong molecular interactions with the API (e.g., hydrogen bonding). Studies show that PVP K30 can outperform other polymers like HPMC E5 in stabilizing indomethacin against recrystallization [30].

- Storage Conditions: Store the ASD in airtight containers with desiccants. Exposure to moisture and high temperature can plasticize the polymer and mobilize the API molecules, facilitating crystallization [30].

- Add Stabilizers: Incorporate small amounts of surfactants into the formulation to improve wettability and help maintain supersaturation during dissolution [28].

Q2: When scaling up from lab to pilot/commercial scale, the performance of my ASD changes. What is the key to successful scale-up?

- A:

- For HME: The continuous nature of HME makes it highly scalable. Successful scale-up relies on maintaining consistent key parameters such as specific mechanical energy (SME), melt temperature, and shear rate by adjusting screw configuration and speed [34].

- For Spray Drying: Scale-up is more complex due to changes in chamber geometry and gas flow dynamics. The key is to maintain consistent droplet size and drying kinetics (e.g., by keeping the outlet temperature constant across scales) rather than directly copying all parameters [31]. Using a Quality by Design (QbD) approach and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) is highly recommended for both techniques [32].

Lipid-based drug delivery systems have emerged as a cornerstone technology for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble bioactive compounds and drugs [37]. These systems, which include self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) and liposomes, address fundamental challenges in pharmaceutical development by improving solubility, protecting active ingredients from degradation, and facilitating targeted delivery [38]. For researchers focused on improving bioactive compound bioavailability, understanding the formulation strategies, troubleshooting common issues, and implementing optimized protocols is essential for successful experimental outcomes.

The following technical support content provides practical guidance structured in a question-and-answer format, specifically addressing challenges researchers might encounter during experimentation with SEDDS and liposomal formulations. This resource integrates current methodologies, troubleshooting guides, and essential reagent information to support your research within the broader context of bioavailability enhancement.

Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS): Technical Guide

SEDDS Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My SEDDS formulation shows drug precipitation upon dilution in gastrointestinal fluids. What are the potential causes and solutions?

- Cause: Insufficient surfactant concentration or inappropriate surfactant-to-oil ratio.

- Solution: Increase surfactant concentration or incorporate polymeric precipitation inhibitors such as HPMC or PVP [37].

- Preventive Approach: Conduct in vitro lipolysis studies during formulation development to predict precipitation tendencies and optimize lipid composition [39].

Q2: What causes chemical instability of the drug in SEDDS, and how can it be mitigated?

- Cause: Interaction between drug and excipients, or susceptibility to enzymatic degradation.

- Solution: Use alternative lipid excipients with better compatibility, or incorporate antioxidants like butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) [37].

- Advanced Strategy: Transition from liquid SEDDS (L-SEDDS) to solid SEDDS (S-SEDDS) via spray drying or adsorption to solid carriers to enhance stability [37].

Q3: How can I improve the poor emulsification efficiency of my SEDDS formulation?

- Cause: Suboptimal selection of surfactants or cosurfactants.

- Solution: Systematically screen surfactants (e.g., Tween 80, Labrasol) and cosurfactants (e.g., Transcutol HP) using phase diagram studies [37].

- Diagnostic Tool: Use droplet size analysis after emulsification; optimal SEDDS should form microemulsions with droplet size <300 nm [37].

Q4: My solid SEDDS formulation shows slow drug release. What could be the reason?

- Cause: Improper solidification technique or excessive carrier material.

- Solution: Optimize the spray drying parameters or reduce the adsorbent carrier ratio [37].

- Alternative Approach: Use hot-melt extrusion instead of adsorption for solidification to create more porous structures [37].

SEDDS Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preparation and Characterization of Solid SEDDS

Objective: To formulate solid SEDDS (S-SEDDS) with enhanced stability and dissolution properties.

Materials:

- Drug compound

- Lipids: Medium-chain triglycerides (e.g., Captex 355), long-chain triglycerides (e.g., Soybean oil)

- Surfactants: Tween 80, Labrasol, Cremophor RH 40

- Cosurfactants: PEG 400, Transcutol HP

- Solid carriers: Neusilin US2, Aerosil 200, Syloid 244FP

Procedure:

- Liquid SEDDS Preparation:

- Dissolve drug in mixture of oil, surfactant, and cosurfactant

- Stir continuously at 40°C until clear solution forms

- Conduct preliminary emulsification studies in 0.1N HCl and phosphate buffer pH 6.8

Transition to Solid SEDDS:

- Adsorption Method: Mix liquid SEDDS with solid carriers in 1:1 to 1:2 ratio

- Spray Drying: Dissolve solid carriers in liquid SEDDS and spray dry at inlet temperature 100°C, outlet temperature 60°C

- Melt Extrusion: Incorporate lipids and drug into hot-melt extruder at temperature 10°C above lipid melting point

Characterization:

- Droplet size analysis using dynamic light scattering

- Dissolution studies in biorelevant media

- Solid-state characterization (DSC, PXRD) to confirm amorphous state

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain temperature below drug degradation point during processing

- Optimize carrier ratio to avoid poor flow properties or excessive moisture absorption

- Conduct stability studies at accelerated conditions (40°C/75% RH) for 3 months [37]

Quantitative Composition Data for SEDDS Formulations

Table 1: Typical Composition Ranges for SEDDS Formulations

| Component | Type | Concentration Range (% w/w) | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oils/Lipids | Medium-chain triglycerides | 20-50% | Solubilize lipophilic drugs, promote lymphatic transport | Captex 355, Miglyol 812 |

| Long-chain triglycerides | 20-50% | Enhance drug solubilization, resist precipitation | Soybean oil, Peanut oil | |

| Surfactants | Non-ionic | 30-60% | Lower interfacial tension, facilitate emulsion formation | Tween 80, Cremophor RH 40 |

| Co-surfactants | Short-chain alcohols | 10-30% | Further reduce interfacial tension, increase emulsion stability | PEG 400, Ethanol, Transcutol HP |

| Drug Load | Active compound | 5-20% | Therapeutic agent | Varies by drug properties |

Table 2: Characterization Parameters for SEDDS Quality Control

| Parameter | Method | Acceptance Criteria | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Size | Dynamic light scattering | <300 nm for SNEDDS, <5000 nm for SMEDDS | Determines absorption rate and bioavailability |

| Polydispersity Index | Dynamic light scattering | <0.3 | Indicates uniformity of emulsion droplets |

| Emulsification Time | Visual observation in USP dissolution apparatus | <2 minutes | Ensures rapid self-emulsification |

| Drug Content | HPLC analysis | 95-105% of labeled claim | Ensures dosage accuracy |

| Stability | Accelerated stability testing | No precipitation or phase separation | Predicts shelf life |

SEDDS Workflow Visualization

SEDDS Formulation Development Workflow

Liposomal Formulations: Technical Guide

Liposome Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My liposome formulation shows low encapsulation efficiency for hydrophilic drugs. How can I improve this?

- Cause: Leakage of drug during formation or inappropriate loading method.

- Solution: For hydrophilic drugs, use active loading techniques with gradient methods (e.g., pH gradient, ammonium sulfate) [40].

- Advanced Technique: Implement remote loading using calcium acetate gradient as demonstrated for dexamethasone hemisuccinate [40].

Q2: What causes liposome aggregation during storage, and how can it be prevented?

- Cause: Insufficient surface charge or inappropriate lipid composition.

- Solution: Incorporate charged lipids (e.g., dicetyl phosphate for negative charge) or optimize cholesterol content (typically 30-50 mol%) [41] [42].

- Storage Solution: Lyophilize with cryoprotectants (e.g., trehalose, sucrose) and store at 4°C [42].

Q3: My liposomes show rapid clearance in vivo. How can I extend circulation time?

- Cause: Recognition by mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS).

- Solution: Incorporate PEGylated lipids (5-10 mol%) to create "stealth" liposomes [42].

- Optimization Note: Balance PEG content as excessive PEG can hinder cellular uptake and cause ABC phenomenon with repeated dosing [42].

Q4: How can I achieve consistent liposome size with minimal batch-to-batch variation?

- Cause: Inefficient sizing methods or variable process parameters.

- Solution: Implement microfluidic techniques instead of traditional thin-film hydration [40].

- Validation Data: Microfluidics produces unilamellar vesicles with higher loading capacity and lower batch-to-batch differences compared to multilamellar vesicles from thin-film hydration [40].

Liposome Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Microfluidic Preparation of Liposomes

Objective: To prepare unilamellar liposomes with controlled size and high encapsulation efficiency using microfluidic technology.

Materials:

- Lipids: Phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, PEGylated lipids (e.g., DSPE-PEG2000)

- Aqueous phase: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Organic phase: Ethanol or isopropanol

- Microfluidic device (staggered herringbone mixer or hydrodynamic flow focusing design)

Procedure:

- Lipid Solution Preparation:

- Dissolve lipid mixture in organic phase at 10-20 mg/mL concentration

- Maintain molar ratio based on desired composition (typical: 55:40:5 PC:Chol:PEG-lipid)

Microfluidic Process:

- Set aqueous to organic phase flow rate ratio between 3:1 to 5:1

- Maintain total flow rate at 10-15 mL/min

- Collect liposome suspension in PBS buffer

Purification and Characterization:

- Dialyze against buffer or use tangential flow filtration to remove organic solvent

- Characterize particle size, PDI, and zeta potential

- Determine encapsulation efficiency via mini-column centrifugation or dialysis

Critical Parameters:

- Optimize flow rate ratio to control liposome size