Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA) Metabolism: Biochemical Pathways, Health Benefits, and Therapeutic Implications for Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an essential omega-3 fatty acid that must be obtained through dietary sources.

Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA) Metabolism: Biochemical Pathways, Health Benefits, and Therapeutic Implications for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an essential omega-3 fatty acid that must be obtained through dietary sources. We explore the complex metabolic pathway of ALA conversion to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids like EPA and DHA, a process occurring primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum and peroxisomes that is influenced by significant factors including gender, dose, and health status. The article systematically examines ALA's diverse pharmacological effects, including its anti-metabolic syndrome, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-obesity, and neuroprotective properties, alongside its emerging role in modulating intestinal flora. For researchers and drug development professionals, we critically evaluate methodological approaches for studying ALA metabolism, address key challenges in optimizing its bioavailability and efficacy, and provide comparative analysis of its therapeutic potential relative to other omega-3 fatty acids. The review concludes with future directions for translating ALA research into targeted clinical applications and novel therapeutic strategies.

The Essential Nature and Metabolic Fate of Alpha-Linolenic Acid

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) is a potent, endogenous organosulfur compound that serves as an essential cofactor in mitochondrial energy metabolism and represents a critical component of the cellular antioxidant network [1] [2]. Its unique amphiphilic character, which allows for solubility in both aqueous and lipid environments, coupled with its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, distinguishes it from many other antioxidants and underpins its broad therapeutic potential [1] [3]. This whitepaper details the fundamental structural characteristics of ALA and its natural dietary origins, providing a scientific foundation for understanding its role in human physiology and its application in drug development and clinical research, particularly within the context of oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions [1] [2].

Chemical Structure and Properties

The biological activity of alpha-lipoic acid is intrinsically linked to its distinctive chemical architecture.

Core Structure: ALA is systematically named as 1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid or 5-(1,2-dithiolan-3-yl)pentanoic acid, reflecting its core structure—a cyclic disulfide (dithiolane ring) appended with a five-carbon carboxylic acid chain [1] [3] [4]. This structure classifies it as a derivative of octanoic acid [1].

Isomeric Forms: ALA possesses a chiral center, leading to two enantiomeric forms. The R-(+)-enantiomer (R-ALA) is the form naturally occurring in biological systems and found covalently bound to conserved lysine residues in enzyme complexes, serving as an essential cofactor [1] [2]. The S-(-)-enantiomer (S-ALA) is not naturally produced in the body. Most synthetic supplements contain a racemic mixture (R-ALA and S-ALA) [3].

The ALA/DHLA Redox Couple: A key functional feature is its reversible redox chemistry. The oxidized form, ALA, can be reduced in vivo to dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA), where the disulfide bond is broken to form two thiol (-SH) groups [1] [2]. The ALA/DHLA pair creates a potent redox couple with a standard reduction potential of -0.32 V, which is central to its antioxidant function [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties of Alpha-Lipoic Acid

| Property | Description | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC Name | 5-(1,2-dithiolan-3-yl)pentanoic acid [1] | Standardized chemical nomenclature |

| Molecular Formula | C₈Hâ‚â‚„Oâ‚‚Sâ‚‚ [5] | Defines elemental composition |

| Solubility | Amphiphilic (soluble in both lipids and water) [1] [2] | Enables systemic distribution and access to both membrane and cytoplasmic compartments |

| Chirality | One chiral center; exists as R-(+) and S-(-) enantiomers [1] [3] | The R-form is biologically active as a cofactor; S-form is synthetic |

| Redox Pair | ALA (oxidized, disulfide) and DHLA (reduced, dithiol) [1] | Forms a potent, regenerative antioxidant system |

While the body endogenously produces ALA, dietary intake can contribute to systemic levels, though the bioavailability is influenced by several factors.

Primary Food Sources: The highest concentrations of ALA are found in animal tissues with high metabolic activity. Rich sources include heart, liver, and kidney [1] [3]. Among plant-based sources, spinach, broccoli, tomatoes, peas, and Brussels sprouts contain appreciable amounts, with spinach being the richest vegetable source [1] [3].

Bioavailability Considerations: In foods, the natural R-ALA enantiomer is often covalently bound to lysine residues in proteins (as lipoyl-lysine), which can limit its systemic bioavailability upon consumption [3]. Dietary absorption from food sources is generally considered insufficient to significantly elevate bloodstream concentrations, which is why ALA is commonly used in supplemental form for therapeutic purposes [1].

Table 2: Alpha-Lipoic Acid Content in Selected Dietary Sources

| Food Source | Estimated ALA Content | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spinach | Highest among vegetables [1] | Leading plant-based source; precise concentration data varies. |

| Broccoli | Good source [1] [3] | A valuable dietary component for ALA intake. |

| Tomatoes | Good source [1] [3] | Commonly consumed vegetable source. |

| Beef Heart/Kidney | High [1] | Animal organs are among the most concentrated natural sources. |

| Red Meat | Present [4] | Muscle tissue contains lower levels than organs. |

Table 3: Key Differences Between Alpha-Lipoic Acid and Alpha-Linolenic Acid

| Feature | Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) | Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA/ALA) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Class | Organosulfur compound with a dithiolane ring [1] | Polyunsaturated fatty acid (Omega-3) [6] |

| Primary Role | Antioxidant, enzyme cofactor in energy metabolism [1] | Structural membrane component, precursor to EPA and DHA [6] |

| Key Dietary Sources | Spinach, broccoli, organ meats (heart, liver, kidney) [1] [3] | Flaxseeds, chia seeds, walnuts, canola oil [7] |

| Solubility | Amphiphilic [1] | Lipophilic [6] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The ALA/DHLA system exerts its effects through multiple, interconnected biochemical mechanisms, which can be visualized as a coordinated network of direct and indirect actions.

Diagram 1: Multimodal Molecular Mechanisms of ALA/DHLA. The diagram illustrates the interconnected direct antioxidant, indirect antioxidant, and cell signaling actions of the ALA/DHLA redox couple, highlighting its role in neutralizing oxidants, regenerating other antioxidants, and modulating key metabolic and inflammatory pathways.

Detailed Mechanism of Action

Direct Radical Scavenging: The ALA/DHLA system is highly effective at quenching a wide spectrum of reactive oxygen species (ROS). DHLA, in particular, is a powerful scavenger of hydroxyl radicals, peroxyl radicals, and hypochlorous acid [1] [2]. It is noteworthy that neither ALA nor DHLA is highly active against hydrogen peroxide [1].

Metal Chelation: Both forms can chelate redox-active transition metals, preventing them from catalyzing the formation of highly damaging free radicals via Fenton reactions. DHLA chelates Fe³âº, Cd²âº, and Hg²âº, while ALA preferentially binds Cu²âº, Zn²âº, and Pb²⺠[1] [2]. This activity is crucial in contexts like Alzheimer's disease, where metal chelation in the brain can reduce free radical damage [1].

Indirect Antioxidant Effects: ALA/DHLA plays a pivotal role in regenerating the oxidized forms of other critical antioxidants, such as vitamin C (from dehydroascorbate) and vitamin E (from the tocopheroxyl radical), effectively recycling them back to their active states [1] [2] [4]. Furthermore, ALA enhances cellular levels of glutathione (GSH) by acting as a transcriptional inducer of genes involved in its synthesis and by increasing the availability of cysteine, a key precursor [1] [5].

Modulation of Key Signaling Pathways: ALA inhibits the activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, thereby reducing the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules [1] [2]. In glucose metabolism, ALA exhibits insulin-mimetic properties by enhancing insulin receptor (IR) and insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation, activating the PI3K/Akt pathway, and modulating AMPK activity, culminating in the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane and increased glucose uptake [3].

Experimental Analysis Protocols

To investigate the bioavailability and metabolic effects of ALA in a research setting, well-established in vivo and in vitro protocols are employed.

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic and Efficacy Study (Rodent Model)

This protocol is designed to assess the absorption, distribution, and biochemical efficacy of ALA administration in an animal model.

- Objective: To determine the plasma concentration time profile and target tissue uptake of orally administered ALA, and to evaluate its subsequent effect on tissue antioxidant status and glucose metabolism.

Materials:

- Test Compound: R-(+)-Alpha-lipoic acid (purity ≥98%) or racemic ALA [3].

- Animals: Male Wistar or Sprague-Dawley rats (8-10 weeks old).

- Vehicle: Saline or a minimal volume of DMSO followed by dilution in saline for intravenous administration; for oral gavage, ALA can be suspended in a weak alkaline solution to enhance solubility [2].

- Equipment: HPLC system with UV/electrochemical detector, microcentrifuges, spectrophotometer, surgical tools for tissue collection.

Procedure:

- Administration & Sampling: Rats are fasted for 12 hours with free access to water. ALA is administered via oral gavage at a dose of 50-100 mg/kg. Blood samples (~200 µL) are collected from the tail vein or retro-orbital plexus into heparinized tubes at pre-dose, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 hours post-administration [2].

- Plasma Processing: Blood samples are immediately centrifuged at 4°C (3000 × g for 10 min). Plasma is separated and stabilized with an antioxidant preservative (e.g., metaphosphoric acid) and stored at -80°C until analysis.

- Tissue Collection: At terminal time points (e.g., 1 hour and 4 hours), animals are euthanized. Tissues of interest (liver, brain, kidney, skeletal muscle) are rapidly excised, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C.

- Bioanalysis: ALA and DHLA concentrations in plasma and tissue homogenates are quantified using a validated HPLC method with UV (333 nm) or electrochemical detection.

- Efficacy Biomarkers: Homogenates of liver and muscle are analyzed for:

- Glutathione Status: Ratio of reduced (GSH) to oxidized (GSSG) glutathione using an enzymatic recycling assay.

- Lipid Peroxidation: Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) levels via thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay.

- Glucose Uptake (in muscle): Assessment of GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane via subcellular fractionation and western blotting.

In Vitro Glucose Uptake Assay (Cell Culture)

This protocol measures the direct effect of ALA on stimulating glucose uptake in cultured adipocytes or skeletal muscle cells.

- Objective: To quantify ALA-induced glucose uptake and elucidate the involved signaling pathways in a controlled cell culture system.

Materials:

- Cell Line: 3T3-L1 adipocytes (differentiated) or L6 myotubes.

- Test Compounds: ALA, DHLA, specific inhibitors (e.g., LY294002 for PI3K, SB203580 for p38 MAPK, Compound C for AMPK).

- Radiotracer: 2-Deoxy-D-[1,²H]glucose.

- Buffers: Krebs-Ringer Phosphate HEPES (KRPH) buffer (pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Cell culture incubator, scintillation counter, western blot apparatus.

Procedure:

- Cell Treatment: Differentiated adipocytes or myotubes are serum-starved for 3-6 hours. Cells are pre-treated with or without pathway-specific inhibitors for 1 hour, followed by stimulation with ALA (0.1-1.0 mM) or insulin (positive control) for 30-60 minutes [3].

- Glucose Uptake Measurement: Cells are washed with warm KRPH buffer and incubated with 2-Deoxy-D-[1,²H]glucose (e.g., 0.1 µCi/well) in KRPH for a defined period (e.g., 10 minutes). The reaction is stopped by washing cells three times with ice-cold PBS.

- Lysis and Quantification: Cells are lysed with 0.1% SDS. An aliquot of the lysate is used for scintillation counting to measure radiolabeled glucose incorporation. Another aliquot is used for protein quantification (e.g., BCA assay) to normalize uptake data.

- Pathway Analysis: Parallel wells are used for protein extraction. Signaling pathway activation is analyzed by western blotting for phosphorylated and total levels of proteins such as Akt, p38 MAPK, AMPK, and IR/IRS-1.

Diagram 2: In Vitro Glucose Uptake Assay Workflow. The flowchart outlines the key steps for evaluating ALA-induced glucose uptake in cultured adipocytes or myotubes, including treatment, radiotracer-based measurement, and subsequent signaling pathway analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Investigating Alpha-Lipoic Acid Biology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| R-(+)-Alpha-Lipoic Acid (≥98%) | Gold standard for studies; represents the natural, biologically active enantiomer. | Investigating specific cofactor roles and high-potency effects in enzyme assays and cell culture [1] [3]. |

| Racemic (R/S) Alpha-Lipoic Acid | Represents the commonly available supplemental form. | Comparative studies to evaluate the efficacy and metabolism of the synthetic vs. natural form [3]. |

| Dihydrolipoic Acid (DHLA) | The reduced, active form of the antioxidant couple. | Directly studying the potent reducing and radical-scavenging capacity of the reduced form [1] [2]. |

| Pathway Inhibitors (e.g., LY294002, SB203580, Compound C) | Pharmacological tools to dissect signaling mechanisms. | Elucidating the contribution of PI3K, p38 MAPK, and AMPK pathways to ALA-induced glucose uptake [3]. |

| 2-Deoxy-D-[1,³H]glucose | Non-metabolizable radiolabeled glucose analog. | Quantifying the rate of glucose transporter activity and glucose uptake in cell cultures [3]. |

| Antibodies (anti-p-Akt, anti-p-p38, anti-GLUT4) | Detection of protein expression and activation states. | Western blot analysis to confirm activation of insulin signaling and downstream pathways [3]. |

| 4-Methoxychalcone | 4-Methoxychalcone|CAS 959-33-1|Research Chemical | |

| Quercetin 3-gentiobioside | Quercetin|CAS 117-39-5|For Research | High-purity Quercetin flavonol for research use only (RUO). Explore its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer research applications. Not for human consumption. |

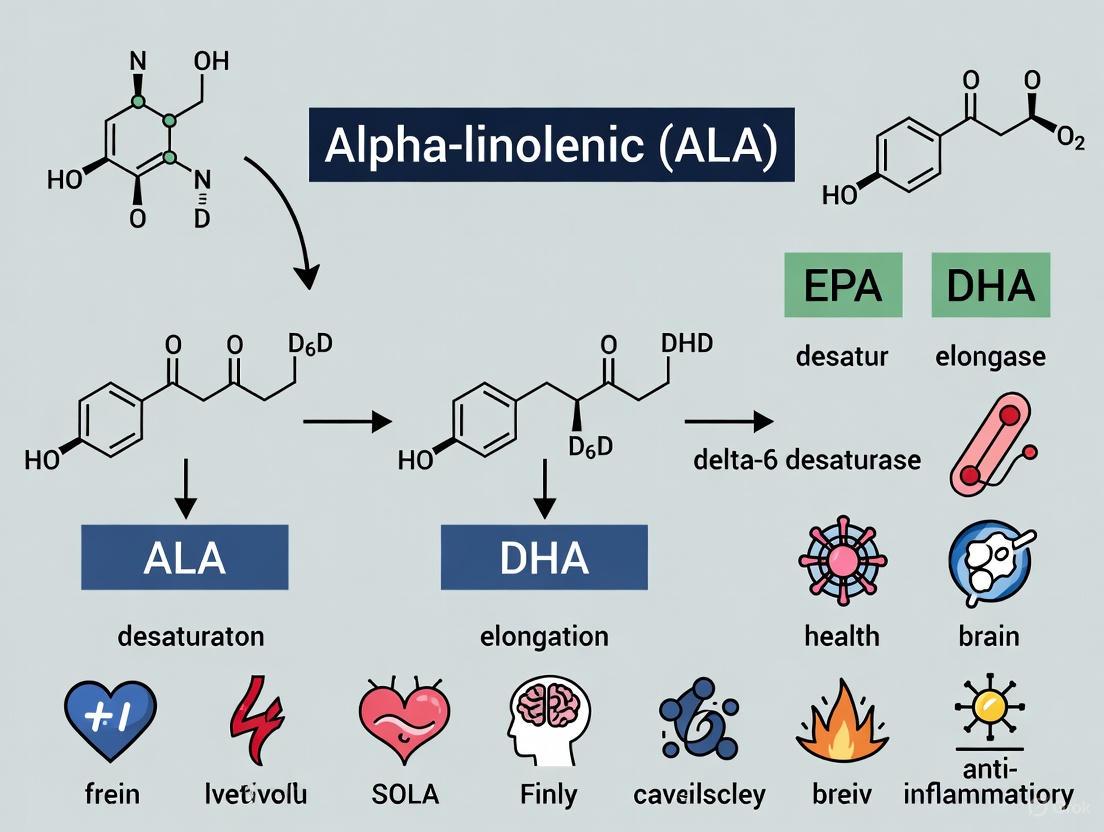

ALA as a Precursor for EPA and DHA Synthesis

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) serves as the essential dietary precursor for the synthesis of longer-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), primarily eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). This whitepaper comprehensively examines the metabolic pathways, conversion efficiencies, influencing factors, and methodological approaches for studying ALA metabolism. The conversion process occurs through a series of desaturation and elongation reactions, though this transformation is notably limited in humans, with estimated rates below 8% for EPA and less than 4% for DHA [8]. Recent evidence indicates that sex differences, genetic polymorphisms, dietary composition, and health status significantly impact endogenous synthesis efficiency [9] [8]. Understanding these complex metabolic pathways is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize omega-3 status through both dietary interventions and targeted therapeutic approaches.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) constitute a family of essential lipids with profound implications for human health. The biochemical classification of PUFAs depends on the position of the terminal double bond relative to the methyl end of the fatty acid chain. Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an 18-carbon chain with three double bonds (18:3n-3), represents the essential precursor from which longer-chain omega-3 PUFAs are derived [10]. As an essential fatty acid, ALA cannot be synthesized de novo by humans and must be obtained from dietary sources such as flaxseed, chia, walnuts, and canola oil [11] [10].

The metabolic pathway proceeds through a series of enzymatic reactions involving desaturases and elongases that convert ALA to stearidonic acid (SDA, 18:4n-3), eicosatetraenoic acid (ETA, 20:4n-3), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, 22:5n-3), and ultimately to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) [12]. The same enzyme systems metabolize both omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, creating competitive inhibition between these pathways [13] [8]. The typical Western diet, characterized by a high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio (ranging from 15:1 to 40:1), further limits the already constrained conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA [11]. This metabolic landscape forms the foundation for understanding how dietary ALA contributes to the body's omega-3 status and subsequent health outcomes.

Metabolic Pathways and Conversion Efficiency

The Enzymatic Conversion Pathway

The conversion of ALA to long-chain omega-3 PUFAs involves a coordinated series of enzymatic reactions occurring primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum, with the final step for DHA synthesis taking place in peroxisomes [12]. The pathway begins with rate-limiting delta-6 desaturase (D6D) catalyzing the conversion of ALA to stearidonic acid (SDA). SDA then undergoes elongation to eicosatetraenoic acid (20:4n-3), which is desaturated by delta-5 desaturase (D5D) to form EPA [12] [14].

EPA is elongated to docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, 22:5n-3), which can be further elongated to tetracosapentaenoic acid (24:5n-3). This intermediate then undergoes a second D6 desaturation to tetracosahexaenoic acid (24:6n-3), which is translocated to peroxisomes for beta-oxidation to produce DHA (22:6n-3) [12]. This complex pathway shares the same enzymatic machinery with the omega-6 PUFA metabolism, creating inherent competition between the two pathways based on substrate availability [13].

Figure 1: Metabolic pathway of ALA to EPA and DHA synthesis showing enzymatic steps and cellular compartments.

Quantitative Conversion Efficiency

The conversion efficiency of ALA to long-chain omega-3 PUFAs is fundamentally limited in humans. Recent studies utilizing stable isotope tracers and dietary intervention trials have quantified these conversion rates, revealing significant constraints in the metabolic pathway, particularly for DHA synthesis.

Table 1: Conversion Efficiency of ALA to Long-Chain Omega-3 PUFAs in Humans

| Metabolic Product | Average Conversion Rate | Key Influencing Factors | Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA | <8% [8] | Sex, dietary LA intake, ALA dose | ALA supplementation increases EPA levels in blood and tissues [9] |

| DHA | <4% [8] | Sex, age, genetic polymorphisms | ALA supplementation typically shows no significant effect on DHA levels or omega-3 index [9] |

| Overall Omega-3 Index | Minimal impact from ALA | Baseline omega-3 status, health conditions | EPA and DHA intake considered primary strategy for improving omega-3 index [9] |

The conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA is significantly influenced by dietary factors, particularly the competitive inhibition from high linoleic acid (LA, omega-6) intake [8]. Studies have demonstrated that restricting LA while increasing ALA intake can modestly enhance EPA levels, though the effect on DHA remains limited [8]. Additionally, dose-response relationships have been observed, with one clinical trial finding that 30 grams daily of ground flaxseed successfully raised EPA levels in blood, while 10 grams daily was insufficient [8].

Factors Influencing ALA Conversion Efficiency

Biological and Dietary Determinants

Multiple factors significantly impact the efficiency of ALA conversion to EPA and DHA, creating substantial interindividual variability in endogenous synthesis capacity.

Table 2: Key Factors Influencing ALA Conversion Efficiency

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Impact on Conversion | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Sex | Premenopausal women show significantly higher conversion, especially to DHA [8] | Estrogen upregulates desaturase enzymes (FADS1, FADS2) [8] |

| Biological | Genetic polymorphisms | FADS gene variants alter desaturase activity and efficiency | Genetic variations affect enzyme expression and function [8] |

| Biological | Health status | Obesity and metabolic diseases reduce conversion efficiency [9] | Altered enzyme activities and inflammatory states impair metabolism [9] |

| Dietary | Omega-6 intake | High LA intake substantially reduces ALA conversion [8] | Competition for shared desaturase and elongase enzymes [13] |

| Dietary | ALA dose | Dose-dependent response observed for EPA synthesis | Threshold effect; sufficient substrate required for measurable conversion [8] |

| Dietary | Pre-formed EPA/DHA intake | Feedback inhibition of conversion pathway | Regulatory mechanisms suppress endogenous synthesis when pre-formed LC-PUFAs are adequate |

Notably, stearidonic acid (SDA), an intermediate in the conversion pathway, demonstrates enhanced conversion to EPA compared to ALA. SDA bypasses the initial rate-limiting delta-6 desaturase step, potentially offering better conversion efficiency for increasing EPA status [14]. However, similar to ALA, SDA conversion to DHA remains substantially limited in most humans [14].

Impact of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders

Recent evidence indicates that obesity and related metabolic diseases significantly alter the conversion efficiency of ALA to long-chain omega-3 PUFAs. The obesity-associated changes in desaturase and elongase activities can impair the metabolic conversion of ALA, potentially creating a vicious cycle of increased metabolic risk [9]. Studies confirm that EPA and DHA intake should be considered as a primary dietary treatment strategy for improving the omega-3 index in obesity and related diseases, as ALA supplementation alone is insufficient to significantly impact DHA status or the omega-3 index in these populations [9].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Approaches

Dietary Assessment and Biomarker Analysis

Research on ALA metabolism employs sophisticated methodological approaches to quantify conversion efficiency and track metabolic fate. Dietary assessment represents the foundational approach, with validated food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) specifically designed to capture habitual intake of ALA and other PUFAs [15]. These instruments have demonstrated strong correlation with blood levels of EPA and DHA (r = 0.62-0.67, p < 0.001) and are particularly effective in identifying individuals with high omega-3 indices (sensitivity 89%, specificity 84%, agreement 86%) [15].

Biomarker analysis provides a more direct assessment of omega-3 status. The omega-3 index, measuring EPA and DHA in erythrocytes, has emerged as a robust biomarker associated with cardiovascular risk [15]. An index of 8% or higher correlates with reduced cardiovascular disease risk, while 4% or lower indicates increased risk [15]. Stable isotope tracer methodologies represent the gold standard for quantifying conversion kinetics, allowing researchers to track the metabolic fate of labeled ALA through the elongation and desaturation pathway to EPA and DHA [12].

Experimental Supplementation Protocols

Clinical trials investigating ALA metabolism typically employ standardized supplementation protocols with precise dosing and duration parameters:

ALA Supplementation Protocol:

- Source: Flaxseed oil, ground flaxseed, or purified ALA

- Dose Range: 1-30 grams ALA daily [8]

- Duration: Typically 8-12 weeks for stabilization of blood levels

- Controls: Placebo or supplemented with other oils (olive, safflower)

- Compliance Measures: Capsule counts, dietary records, biomarker tracking

Blood Collection and Analysis:

- Timing: Fasting blood samples at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks

- Sample Processing: Plasma, erythrocyte, and platelet isolation

- Fatty Acid Analysis: Gas chromatography with flame ionization detection

- Quality Control: Standardized reference materials, duplicate analysis

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ALA Metabolism Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid Standards | Deuterated ALA (d5-ALA), Carbon-13 labeled EPA | Stable isotope tracer studies | Metabolic pathway tracing and kinetic analysis [12] |

| Enzyme Assays | Delta-6 desaturase activity, FADS2 gene expression | Genetic and enzymatic studies | Quantification of rate-limiting conversion steps [12] |

| Chromatography | Gas chromatography (GC), High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) | Fatty acid separation and quantification | Precise measurement of fatty acid profiles [15] |

| Cell Culture Models | Hepatocyte cell lines (HepG2), Primary human hepatocytes | In vitro metabolism studies | Controlled environment for pathway analysis [12] |

| Dietary Sources | Flaxseed oil, Echium oil (SDA source), Purified ALA | Supplementation studies | Controlled intervention materials [9] [14] |

| Analytical Kits | Lipid extraction kits, Phospholipid separation kits | Sample preparation and fractionation | Standardized processing of biological samples [15] |

The metabolic conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA represents a complex, multi-step process with significant limitations in humans. While ALA serves as the essential dietary precursor for long-chain omega-3 PUFAs, its conversion efficiency is constrained by enzymatic limitations, competitive inhibition from omega-6 fatty acids, and individual biological factors. The research community has made substantial progress in quantifying conversion rates, identifying influencing factors, and developing sophisticated methodological approaches to study ALA metabolism.

For drug development professionals and researchers, these findings highlight the importance of considering direct EPA and DHA supplementation rather than relying solely on ALA precursors for achieving therapeutic omega-3 status, particularly in specific populations such as those with obesity or metabolic disorders. Future research should focus on optimizing conversion efficiency through dietary modulation, identifying genetic factors influencing desaturase activity, and developing novel delivery systems for enhanced bioavailability of omega-3 fatty acids.

Peroxisomes are single-membrane-bound organelles essential for eukaryotic cellular homeostasis, performing crucial metabolic functions including the β-oxidation of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and the biosynthesis of ether phospholipids [16]. Their role in lipid metabolism is particularly relevant to alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) research, as the final synthesis step of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), a critical omega-3 derivative of ALA, occurs within peroxisomes [17]. Unlike most organelles of the endomembrane system, peroxisomes possess a unique capacity to import both membrane and matrix proteins directly from the cytosol [18]. However, a subset of their membrane proteins traffics through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), initiating a multi-step conversion pathway that is fundamental to peroxisome biogenesis and function [18] [19].

Understanding this ER-to-peroxisome pathway is paramount for researchers investigating ALA metabolism and its health benefits. Peroxisomal function directly impacts the conversion efficiency of ALA to its longer-chain, more bioactive metabolites, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and DHA [17]. Defects in peroxisome biogenesis disrupt this metabolic pathway and are linked to severe neurological disorders, underscoring the organelle's critical role in brain health and lipid homeostasis [20] [16]. This technical guide details the molecular mechanisms of the ER-dependent peroxisomal protein import pathway, providing methodologies and resources to support advanced research in this field.

Core Mechanisms of the ER-to-Peroxisome Pathway

The biogenesis of peroxisomes involves two coordinated mechanisms: de novo generation from the ER and fission from pre-existing organelles [19]. The ER-dependent, or de novo, pathway is responsible for the initial formation of pre-peroxisomal vesicles.

Key Stages ofDe NovoBiogenesis

Vesicle Budding from the ER: The process initiates in the ER membrane with the insertion of key peroxisomal membrane proteins (PMPs). PEX16 is integrated into the ER membrane, where it functions as a docking site for PEX3 [16]. This PEX3-PEX16 complex then recruits other PMPs to form a pre-peroxisomal vesicle that buds from the ER [16] [19].

Formation of Immature Pre-Peroxisomal Vesicles: These ER-derived vesicles are considered "immature" as they contain a basic set of membrane proteins but lack the full complement of matrix enzymes required for metabolic activity [16]. They serve as primordial structures that can mature into functional peroxisomes.

Vesicle Maturation and Fusion: The immature vesicles acquire additional PMPs and matrix proteins through protein import from the cytosol. They may also undergo homotypic fusion (fusion with each other) to form mature, metabolically active peroxisomes [19]. The import of matrix proteins relies on a dedicated translocation machinery composed of peroxins (PEX proteins) that recognize specific targeting signals [18] [16].

Table 1: Key Peroxins in ER-Dependent Peroxisome Biogenesis and Matrix Protein Import

| Peroxin | Primary Function | Process | Human Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEX3 | PMP receptor; recruits PEX19; initiates ER-derived vesicle formation [16] | Membrane Biogenesis | Zellweger syndrome spectrum [19] |

| PEX16 | Docking receptor for PEX3 in the ER membrane [16] | Membrane Biogenesis | Zellweger syndrome spectrum [19] |

| PEX19 | Cytosolic chaperone and import receptor for PMPs [16] | Membrane Biogenesis | Zellweger syndrome spectrum [19] |

| PEX5 | Shuttling receptor for PTS1-containing matrix proteins [18] [16] | Matrix Protein Import | Zellweger syndrome spectrum [19] |

| PEX7 | Receptor for PTS2-containing matrix proteins; requires PEX5L in mammals [18] [16] | Matrix Protein Import | Rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata [19] |

| PEX11β | Promotes membrane elongation and division; stimulates DRP1 GTPase activity [20] [16] | Proliferation & Fission | Neurodegeneration [20] |

Matrix Protein Import and Pore Formation

Matrix proteins are synthesized on free polyribosomes in the cytosol and contain specific peroxisomal targeting signals (PTS), either PTS1 (C-terminal) or PTS2 (N-terminal) [18] [16]. The PTS1 receptor, PEX5, and the PTS2 receptor, PEX7, deliver their cargo to a common docking complex on the peroxisomal membrane comprising PEX13 and PEX14 [18] [16] [19].

A critical feature of peroxisomal import is its capacity to translocate folded, cofactor-bound, and even oligomeric proteins [18] [19]. The mechanism underlying this capability involves a transient pore. Current models suggest that the cargo-loaded PEX5 receptor integrates into the membrane, oligomerizing with PEX14 to form a transient, gated translocation channel [19]. After cargo release into the matrix, the PEX1-PEX6-PEX26 AAA-ATPase complex, in concert with RING ubiquitin ligases (PEX2, PEX10, PEX12), facilitates the mono-ubiquitination and extraction of PEX5 back to the cytosol for another round of import [16].

Diagram 1: ER to peroxisome biogenesis pathway.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating the Pathway

Protocol 1: Tracking PMP Trafficking from the ER

This protocol utilizes pulse-chase assays and subcellular fractionation to visualize the movement of PMPs from the ER to peroxisomes.

- Primary Objective: To determine the kinetics and pathway of a specific PMP (e.g., PEX3 or PEX16) from its synthesis in the ER to its integration into mature peroxisomes.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: Wild-type and PEX-deficient (e.g., ΔPEX3 or ΔPEX19) mammalian fibroblasts [16].

- Radiolabeling Agent: 35S-methionine/cysteine for metabolic pulse-chase labeling.

- Lysis Buffer: Hypotonic buffer for cell disruption.

- Antibodies: Specific antibodies against the target PMP (e.g., anti-PEX3), organelle markers (Calnexin for ER, PMP70 for peroxisomes).

- Density Gradient Medium: Sucrose or iodixanol for equilibrium density centrifugation.

- Methodology:

- Pulse Phase: Incubate cells with 35S-methionine/cysteine for a short period (e.g., 15-30 minutes) to label newly synthesized proteins.

- Chase Phase: Replace radiolabeled medium with complete cold medium and harvest cells at various time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Cell Lysis and Fractionation: Lyse cells using a hypotonic buffer. Perform differential centrifugation to obtain a heavy membrane fraction (containing ER, mitochondria, peroxisomes).

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: Resuspend the heavy membrane fraction and load onto a pre-formed sucrose density gradient (e.g., 20-50%). Centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 3 hours to separate organelles based on buoyant density.

- Analysis: Collect gradient fractions. Perform immunoprecipitation with anti-PEX3 antibody. Analyze the radiolabeled PEX3 across fractions by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Co-localization with ER and peroxisomal markers confirms the trafficking route.

- Key Controls: Use PEX-deficient cells, which should arrest the process, causing accumulation of the PMP in the ER [16].

Protocol 2:In VitroPeroxisomal Protein Import Assay

This assay reconstitutes the import of matrix proteins into purified peroxisomes, allowing for mechanistic studies.

- Primary Objective: To quantify the import efficiency of PTS1 or PTS2-containing matrix proteins and identify required cytosolic and membrane components.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Purified Peroxisomes: Isolated from rat liver or a model cell line (e.g., HepG2) using density gradient centrifugation.

- Radiolabeled Cargo Protein: 35S-labeled catalase (PTS1) or thiolase (PTS2) synthesized using a rabbit reticulocyte lysate transcription/translation system.

- Energy-Regenerating System: ATP, GTP, creatine phosphate, creatine kinase.

- Protease: Proteinase K to degrade non-imported proteins.

- Protease Inhibitor: PMSF to terminate protease activity.

- Methodology:

- Import Reaction: Combine purified peroxisomes, radiolabeled cargo, cytosolic extract (as a source of soluble peroxins like PEX5), and the energy-regenerating system in import buffer. Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Protease Protection: Treat the reaction with Proteinase K on ice to digest all proteins outside the peroxisomes. The imported, protease-protected proteins indicate successful translocation across the membrane.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop protease digestion with PMSF. Re-isolate peroxisomes by centrifugation, solubilize, and analyze by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The amount of radiolabeled, protease-protected cargo quantifies import.

- Inhibition Studies: Repeat the assay with ATP-depleting systems (apyrase) or antibodies against specific peroxins (e.g., anti-PEX5) to confirm the specificity and requirements of the import process [18].

- Key Parameters: The import of oligomeric proteins can be tested by pre-assembling cargo complexes in the reticulocyte lysate [18].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying ER-to-Peroxisome Pathways

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEX-Knockout Cell Lines | ΔPEX3, ΔPEX19 human fibroblasts [16] | Establishing genetic requirements for protein trafficking. | Models for peroxisome biogenesis disorders; blocks early biogenesis steps. |

| Organelle-Specific Markers | Anti-Calnexin (ER), Anti-PMP70 (Peroxisomes) [16] | Immunofluorescence and fractionation analysis. | Validates organelle identity and purity in localization studies. |

| PMP Expression Plasmids | Plasmids encoding GFP-PEX3, GFP-PEX16 [16] | Live-cell imaging of de novo biogenesis. | Visualizes the initial stages of pre-peroxisomal vesicle formation from the ER. |

| Recombinant Matrix Proteins | 35S-labeled Catalase (PTS1), Thiolase (PTS2) [18] | In vitro import assays. | Measures import competence and kinetics into isolated peroxisomes. |

| Specific Antibodies vs. Peroxins | Anti-PEX5, Anti-PEX14, Anti-PEX1 [16] [19] | Co-IP, Western Blot, functional inhibition. | Identifies protein complexes and tests functional necessity. |

Integration with ALA Metabolism and Research Implications

The ER-to-peroxisome pathway is not an isolated process; it is functionally coupled with the metabolism of alpha-linolenic acid. The final and critical step in the synthesis of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) from ALA occurs within peroxisomes via partial β-oxidation [17]. The product of this pathway, DHA, is not only a crucial component of neuronal membranes but also a regulator of peroxisome dynamics itself. DHA has been shown to induce peroxisomal division by augmenting the hyper-oligomerization of PEX11β, thereby promoting the fission of elongated peroxisomes [16]. This creates a feed-forward loop where functional peroxisomes are necessary to produce DHA, which in turn stimulates the proliferation of more peroxisomes.

This interconnection has profound implications for health and disease. Peroxisomal disorders consistently present with severe neurological phenotypes, partly due to impaired synthesis of ether-phospholipids and DHA, both essential for brain structure and function [20] [16]. Furthermore, altered peroxisome dynamics are observed in common neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, suggesting a broader role in neuronal health [20] [19]. Recent clinical research also highlights the potential of ALA supplementation, demonstrating that concurrent administration of ALA and L-carnitine significantly reduced migraine frequency and severity and improved mental health outcomes in women [21]. This underscores the translational potential of targeting these metabolic pathways for therapeutic intervention.

Diagram 2: ALA metabolism and peroxisome feedback.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Advanced Research Tools for Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent Category | Product Examples | Specific Research Use | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell Organelle Dyes | MitoTracker (mitochondria), ER-Tracker (ER) | Simultaneous staining of multiple organelles for imaging inter-organelle contacts. | Confirm dye compatibility and absence of spectral bleed-through. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Knock-in Kits | GFP-PTS1 knock-in cell line | Generation of stable cell lines for real-time monitoring of peroxisome abundance and matrix import. | Ideal for high-content screening of compounds affecting peroxisome function. |

| Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) Kits | Duolink PLA | Detecting and visualizing very close (<40 nm) protein-protein interactions, e.g., between ER and peroxisomal proteins. | Provides superior resolution over standard co-localization microscopy. |

| Recombinant AAA-ATPase Complex | Purified PEX1-PEX6-PEX26 complex [16] | In vitro studies of the receptor recycling step in matrix protein import. | Essential for reconstituting the complete ATP-dependent import cycle. |

| Lipid Standards for Analytics | Deuterated DHA, VLCFA standards | Quantitative mass spectrometry of peroxisomal lipid metabolites (e.g., after ALA supplementation). | Enables precise tracking of metabolic flux through the ALA/DHA pathway. |

| 3,4',7-Trihydroxyflavone | 3,4',7-Trihydroxyflavone, CAS:2034-65-3, MF:C15H10O5, MW:270.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Quercetin 7-O-rhamnoside | Vincetoxicoside B | Vincetoxicoside B is a natural flavonoid with research applications in antifungal and antidiabetic studies. It shows synergistic antifungal activity. For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

The metabolism of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) to long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is a critical biochemical process with profound implications for human health and disease. This transformation is mediated by a series of tightly regulated enzymatic reactions, with fatty acid desaturases (FADS1 and FADS2) and very-long-chain fatty acid elongases (ELOVL) serving as the cornerstone enzymes governing metabolic flux. This technical review comprehensively examines the structural characteristics, functional properties, substrate specificities, and regulatory mechanisms of these key enzymes. We synthesize current evidence on how genetic polymorphisms, epigenetic modifications, and dietary factors modulate enzyme activity and ultimately influence PUFA profiles. The clinical and therapeutic implications of these regulatory mechanisms are discussed, with particular emphasis on the potential for personalized nutrition strategies based on individual genetic makeup. This analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of the molecular machinery driving ALA metabolism and its translational applications.

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) serves as the essential omega-3 fatty acid precursor for the biosynthesis of longer-chain, more unsaturated PUFAs, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). These downstream metabolites play vital roles in neuronal development, visual acuity, inflammatory resolution, and cardiovascular protection [22]. The conversion from dietary ALA to these highly bioactive derivatives occurs through a series of alternating desaturation and elongation reactions, with FADS1, FADS2, and ELOVL enzymes constituting the core catalytic machinery [23] [24].

The efficiency of this conversion pathway exhibits significant interindividual variability, influenced substantially by genetic variation in the encoding enzymes [25]. Additionally, emerging evidence indicates that epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, further modulate gene expression and activity of these enzymes [25]. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms governing these enzymes is paramount for developing targeted nutritional and therapeutic interventions for metabolic disorders, inflammatory conditions, and other chronic diseases linked to PUFA imbalance.

Enzyme Systems in ALA Metabolism

The metabolic pathway from ALA to DHA involves a coordinated sequence of reactions catalyzed by distinct enzyme families. The desaturation steps are primarily mediated by the FADS enzymes, while the carbon chain elongation is facilitated by the ELOVL family.

Fatty Acid Desaturases (FADS1 and FADS2)

FADS2 (Δ-6 desaturase) initiates the ALA metabolic pathway by catalyzing the conversion of ALA to stearidonic acid (SDA; 18:4n-3). This enzyme also performs the final desaturation step in the "Sprecher pathway" for DHA synthesis, converting 24:5n-3 to 24:6n-3 [24]. FADS1 (Δ-5 desaturase) acts downstream in the pathway, converting eicosatetraenoic acid (20:4n-3) to EPA (20:5n-3) [23].

These enzymes exhibit competitive substrate interactions that significantly impact metabolic outcomes. Notably, ALA dose-dependently inhibits FADS2 conversion of 24:5n-3 to 24:6n-3, creating a critical regulatory node that may explain the observed decrease in DHA levels when dietary ALA intake exceeds certain thresholds [24].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Fatty Acid Desaturase Enzymes

| Enzyme | Gene | Reaction Catalyzed | Primary Substrates | Key Regulatory Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FADS2 (Δ-6 Desaturase) | FADS2 | Δ-6 desaturation | ALA (18:3n-3) → SDA (18:4n-3); 24:5n-3 → 24:6n-3 | Genetic polymorphisms (rs174570), DNA methylation, dietary PUFA |

| FADS1 (Δ-5 Desaturase) | FADS1 | Δ-5 desaturation | 20:4n-3 → EPA (20:5n-3) | Genetic polymorphisms, DNA methylation, competitive inhibition |

Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acid Elongases (ELOVL)

The ELOVL family comprises seven enzymes (ELOVL1-7) that catalyze the condensation reaction, the initial and rate-limiting step in fatty acid elongation. These enzymes exhibit distinct substrate specificities that determine their roles in PUFA metabolism [26].

ELOVL2 demonstrates particular importance in the synthesis of DHA, showing preference for C20 and C22 PUFA substrates. This single enzyme catalyzes the sequential elongation of EPA → DPA → 24:5n-3 [24] [27]. The second reaction (DPA → 24:5n-3) appears to saturate at substrate concentrations not saturating for the first reaction (EPA → DPA), potentially creating a metabolic bottleneck that contributes to DPA accumulation [24].

ELOVL5 has broader substrate selectivity, elongating C18-C22 PUFAs. In some species, including chickens, ELOVL5 demonstrates unique capability to efficiently synthesize 24:5n-3, unlike ELOVL5 enzymes from other species [27].

Table 2: Characteristics of ELOVL Enzymes in PUFA Metabolism

| Enzyme | Substrate Chain Length Preference | Specific Role in ALA Metabolism | Tissue Expression Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELOVL2 | C20 and C22 PUFA | EPA → DPA → 24:5n-3; Critical for DHA synthesis | Widespread: brain, liver, adipose tissue [26] |

| ELOVL5 | C18-C22 PUFA | Elongation of intermediate metabolites; Species-specific roles | Highest in testis and epididymis [26] |

| ELOVL1 | C12-C16 fatty acids | Primarily in saturated/monounsaturated VLCFA synthesis | Highly expressed in skin [26] |

Diagram 1: ALA metabolic pathway and regulatory mechanisms. The pathway illustrates the sequential desaturation and elongation steps from ALA to DHA, highlighting key enzymes and regulatory influences including genetic, epigenetic, and dietary factors.

Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation

Genetic Polymorphisms

Genetic variants in the FADS gene cluster represent crucial modifiers of fatty acid metabolism. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this region have been strongly associated with altered levels of multiple PUFAs [23] [25]. The rs174570 SNP, located in the FADS1 gene, demonstrates particularly significant effects, with the minor allele associated with decreased FADS1 and FADS2 expression levels [25].

These genetic variations modify the activity of PUFA desaturation and consequently influence lipid composition in human blood and tissues. Importantly, FADS variants have been associated with plasma lipid concentrations, cardiovascular disease risk, overweight, eczema, pregnancy outcomes, and cognitive function [23]. The genotype distribution differs markedly among ethnicities, potentially reflecting evolutionary adaptation to diets with varying PUFA compositions [23].

Epigenetic Mechanisms

Epigenetic regulation, particularly DNA methylation, provides another layer of control over FADS gene expression. Methylation quantitative trait locus (mQTL) analysis of rs174570 has revealed that methylation levels at multiple CpG sites in both FADS1 and FADS2 are strongly associated with this genetic variant [25].

The relationship between methylation and gene expression is complex and site-specific. Methylation levels at three CpG sites in FADS1 were negatively associated with FADS1 and FADS2 expression, while two CpG sites in FADS2 showed positive associations with gene expression [25]. Mediation analysis indicates that the observed effect of rs174570 on gene expression is tightly correlated with the effect predicted through association with methylation, suggesting DNA methylation as a potential mechanistic link between genetic variation and gene expression [25].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Key Experimental Protocols

Enzyme Activity Characterization: The substrate selectivities, competitive substrate interactions, and dose-response curves of elongase enzymes can be determined after expression in yeast systems. This approach was used to characterize rat Elovl2 and Elovl5, revealing that Elovl2 is active with C20 and C22 PUFAs and catalyzes sequential elongation reactions [24].

Genetic Association Studies: Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) employ rigorous quality control measures for genotyping data, including exclusion of individuals with high missingness, excess autosomal heterozygosity, high relatedness, ambiguous gender, and ancestry outliers. SNP-level quality control typically excludes markers with call rate <98%, significant departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P < 1×10^(-6)), and minor allele frequency (MAF) <1% [25].

Fatty Acid Quantification: Comprehensive fatty acid profiling utilizes ultra-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOFMS). A panel of 42 free fatty acids (including SFAs, MUFAs, and PUFAs) can be analyzed with quality control measures including reference standard mixtures run after every ten samples. Data processing employs specialized software such as TargetLynx, with manual examination to ensure data quality [25].

DNA Methylation Analysis: Methylation studies require genomic DNA extraction (typically 500 ng) from tissues of interest, followed by bisulfite conversion. Analysis of specific CpG sites in gene regions of interest (e.g., FADS1 and FADS2) provides quantitative methylation data that can be correlated with genetic variants and gene expression [25].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for studying genetic and epigenetic regulation of ALA metabolism. The diagram outlines key methodological steps from sample collection through integrated data analysis for comprehensive investigation of fatty acid metabolism regulation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ALA Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Application | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Infinium Exome-24 BeadChip | Genome-wide genotyping | Interrogates 247,870 SNPs; identifies genetic variants in FADS region [25] |

| UPLC-QTOFMS System | Fatty acid quantification | Precise measurement of 42 individual fatty acids; high sensitivity and resolution [25] |

| RNeasy Plus Universal Kit | RNA isolation from tissues | Maintains RNA integrity for accurate gene expression analysis [25] |

| PrimeScript RT reagent kit | cDNA synthesis | Converts RNA to cDNA with gDNA removal for clean qPCR templates [25] |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Quantitative PCR | Specific detection of FADS1 (Hs00203685m1) and FADS2 (Hs00927433m1) [25] |

| EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit | DNA methylation studies | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines [25] |

| Yeast Expression System | Enzyme characterization | Functional analysis of elongase substrate specificity and kinetics [24] |

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

The regulation of ALA metabolism enzymes has significant implications for human health and disease. Discovering differential effects of PUFA supply that depend on variation of FADS genotypes opens opportunities for developing precision nutrition strategies based either on an individual's genotype or on genotype distributions in specific populations [23].

Dysregulated ELOVL expression has been associated with various disease states, including metabolic disorders, skin diseases, neurodegenerative conditions, and cancer [26]. The intricate involvement of ELOVLs in cancer biology, from tumor initiation to metastasis, highlights their potential as targets for anticancer therapies [26].

The interaction between genetic variants and dietary intake represents a crucial consideration for therapeutic interventions. Studies on variations in the FADS gene cluster provided some of the first examples for marked gene-diet interactions in modulating complex phenotypes, such as eczema, asthma, and cognition [23]. This understanding enables more targeted nutritional recommendations based on individual genetic makeup.

FADS1, FADS2, and ELOVL elongases constitute the fundamental enzymatic machinery governing the metabolism of ALA to long-chain PUFAs. Their activity is modulated through complex genetic, epigenetic, and dietary factors that collectively determine an individual's capacity for EPA and DHA synthesis. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms regulating these enzymes, including the structural characteristics, functional properties, and regulatory networks, provides critical insights for developing targeted interventions for various chronic diseases. Future research directions should focus on further elucidating the tissue-specific regulation of these enzymes, developing isoform-specific modulators, and translating this knowledge into personalized nutrition and therapeutic strategies that optimize PUFA status based on individual genetic and metabolic profiles.

Tissue Distribution and Cellular Incorporation of ALA

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3n-3) is an essential fatty acid that must be obtained from the diet, as the human body lacks the delta-15 desaturase necessary for its synthesis [28]. This carboxylic acid, composed of 18 carbon atoms and three cis double bonds, serves as a crucial metabolic precursor for the synthesis of longer-chain, more unsaturated n-3 fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) [29] [30]. Understanding the tissue distribution and cellular incorporation of ALA is fundamental to elucidating its health benefits, which include anti-metabolic syndrome effects, anticancer properties, anti-inflammatory actions, antioxidant activity, neuroprotection, and regulation of intestinal flora [29]. This technical review synthesizes current research on ALA metabolism, focusing on the factors influencing its distribution, incorporation, and conversion in biological systems, with particular relevance to drug development and therapeutic applications.

Metabolic Pathways of ALA

Biosynthetic Pathway to Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids

After ingestion, ALA undergoes a series of metabolic transformations to yield longer-chain, more unsaturated fatty acids through the actions of desaturase and elongase enzymes [28]. The conversion process begins with delta-6 desaturation of ALA to form stearidonic acid (18:4n-3), followed by elongation to eicosatetraenoic acid (20:4n-3), and then delta-5 desaturation to produce EPA (20:5n-3) [31]. Further elongation and desaturation steps eventually yield DHA (22:6n-3) through a process that involves peroxisomal beta-oxidation [28].

This metabolic pathway competes directly with the parallel pathway for the n-6 fatty acid linoleic acid (LA, 18:2n-6), as both families utilize the same set of enzymes (desaturases and elongases) [31] [28]. The high consumption of LA in typical Western diets (with an n-6/n-3 ratio of approximately 10:1) negatively influences EPA and DHA synthesis from ALA [28]. The modern Western-type dietary pattern has been associated with elevated saturated fatty acid and n-6 PUFA intake, coupled with decreased n-3 PUFA intake, creating an imbalance that affects the metabolic fate of ingested ALA [28].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in ALA Metabolic Pathway

| Enzyme | Gene Symbol | Reaction Catalyzed | Cofactors/Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta-6 desaturase | FADS2 | Conversion of ALA to Stearidonic Acid (SDA) | NADH, Molecular Oxygen |

| Elongase 2/5 | ELOVL2/ELOVL5 | Elongation of SDA to Eicosatetraenoic Acid | Malonyl-CoA, NADPH |

| Delta-5 desaturase | FADS1 | Conversion of Eicosatetraenoic Acid to EPA | NADH, Molecular Oxygen |

| Beta-oxidation enzymes | Various | Peroxisomal chain shortening to DHA | ATP, Carnitine |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Transcriptional Control

The metabolism of ALA is regulated at multiple levels, including transcriptional control of the enzymes involved in its elongation and desaturation. Key transcription factors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) regulate expression of delta-5-desaturase (D5D) and delta-6-desaturase (D6D) [31]. These transcription factors are themselves regulated by various kinases, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) [31]. Research using human hepatoma cells has demonstrated that the ratio of n6 to n3 fatty acids differentially regulates the transcript levels of genes encoding these enzymes [31].

LCPUFA and their derivatives function as ligands for nuclear transcription factors, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), and suppressors of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBP) [31]. PPARα plays a central role in fatty acid homeostasis by regulating the degradation of fatty acids through mitochondrial, peroxisomal, and microsomal fatty acid oxidation pathways [31]. In contrast, SREBP-1 isoforms are more active in regulating hepatic synthesis of fatty acids [31].

Tissue-Specific Distribution Patterns

Hepatic Processing and Distribution

The liver serves as the primary site for ALA metabolism and distribution to peripheral tissues. In human hepatoma cells (HepG2), the conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA has been shown to be highly dependent on the ratio of linoleic acid (LA) to ALA in the incubation medium [31]. Maximum conversion was observed at an LA/ALA ratio of 1:1, where 17% of recovered [13C]ALA was converted to EPA and 0.7% to DHA [31]. This highlights the significant competitive inhibition between n-6 and n-3 fatty acid families for the enzyme systems responsible for their conversion to longer-chain homologs.

The distribution of ALA and its metabolites to peripheral tissues occurs via complex transport mechanisms involving lipoproteins and fatty acid-binding proteins. Following hepatic processing, these fatty acids are incorporated into various lipid classes, particularly triglycerides and phospholipids, and exported to other tissues [28]. The incorporation into phospholipid membranes is especially significant, as it influences membrane fluidity, receptor function, and signal transduction pathways [28].

Tissue Selectivity and Preferential Incorporation

Different tissues exhibit varying capacities for incorporating ALA and its metabolites, with selective retention mechanisms favoring certain long-chain PUFAs. Tissues with high metabolic activity and specialized functions, such as brain, retina, testes, heart, and kidneys, demonstrate particularly high incorporation of LCPUFAs into membrane phospholipids [31]. The constitutive properties of PUFA in biological membranes contribute to fluidity and integrity of membrane bilayer structures [31].

The brain and nervous tissue show exceptional selectivity for DHA, with limited direct uptake of ALA but efficient incorporation of pre-formed DHA [29] [30]. This selective incorporation is mediated by specific fatty acid transport proteins at the blood-brain barrier that preferentially recognize and transport long-chain omega-3 PUFAs. Cardiac tissue also demonstrates preferential incorporation of ALA metabolites, particularly EPA and DHA, which influence cardiac rhythm and contractility.

Table 2: Tissue Distribution of ALA and Metabolites

| Tissue | Primary ALA Metabolites | Incorporation Efficiency | Major Lipid Classes | Special Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | EPA, DPA, DHA | High conversion, lower DHA | Phospholipids, Triglycerides | Primary metabolic site |

| Brain | DHA | Limited ALA, high DHA uptake | Phospholipids | Selective barrier transport |

| Retina | DHA | Very high DHA retention | Phospholipids | Photoreceptor membrane component |

| Adipose | ALA, EPA | High ALA storage | Triglycerides | Long-term storage depot |

| Cardiac | EPA, DHA | Moderate conversion, high uptake | Phospholipids | Electrical stability |

| Plasma | ALA, EPA, DHA | Variable based on intake | Phospholipids, Esters | Short-term pool, transport |

Cellular Incorporation Mechanisms

Membrane Integration and Lipid Raft Organization

At the cellular level, ALA and its metabolites are incorporated into membrane systems through specific enzymatic processes that determine their final localization and functional roles. Once inside cells, fatty acids are activated to acyl-CoAs by acyl-CoA synthetases and then directed to various metabolic fates, including incorporation into complex lipids by acyltransferases [28]. The composition of fatty acids in membrane phospholipids influences membrane physical properties, including fluidity, phase behavior, and formation of specialized microdomains known as lipid rafts.

The incorporation of ALA and its metabolites into specific phospholipid classes is regulated by the substrate specificity of lysophospholipid acyltransferases, which show preferences for certain acyl-CoAs. Phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidyl ethanolamine are major reservoirs for polyunsaturated fatty acids in cellular membranes, with different subcellular membranes exhibiting distinct fatty acid compositions that reflect their specialized functions.

Intracellular Trafficking and Metabolic Channeling

Cellular incorporation of ALA involves complex intracellular trafficking mechanisms that direct the fatty acid to specific metabolic fates and subcellular locations. After cellular uptake, ALA can be directed toward mitochondrial or peroxisomal beta-oxidation for energy production, incorporated into storage triglycerides, integrated into membrane phospholipids, or channeled into the elongation/desaturation pathway for conversion to EPA and DHA [30] [28].

The metabolic channeling of ALA toward specific fates is influenced by numerous factors, including nutritional status, hormonal signals, and genetic factors. Insulin, glucagon, thyroid hormones, and other endocrine factors regulate the partitioning of ALA between oxidative and synthetic pathways [32]. The competition between ALA and LA for the same enzymatic machinery creates a metabolic bottleneck at the level of delta-6 desaturase, which has a higher affinity for ALA but is often overwhelmed by the higher concentrations of LA in typical diets [31] [28].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Cell Culture Models

HepG2 human hepatoma cells have been extensively utilized as an in vitro model system to study ALA metabolism and incorporation. The standard experimental protocol involves growing cells in T-75 cell culture flasks in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2% glutamine, and 2% penicillin/streptomycin solution at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO₂ [31]. For experimentation, cells are transferred to T-25 cell culture flasks at a density of 5 × 10ⶠcells and, after 24 hours, the medium is replaced with serum-free DMEM [31].

After another 24 hours, mixtures of [13C] labeled LA and ALA methyl esters are added to give a final fatty acid concentration of 100 μM, typically suspended by sonication in sterile bovine serum albumin (Fraction V) [31]. Researchers commonly test various ratios of LA/ALA, such as 9:1, 4:1, 1:1, 1:0, and 0:1, with incubation periods of 24 hours at 37°C [31]. Quadruplicate determinations are recommended for statistical reliability. Following exposure, cells are harvested using accutase, washed with FCS-free DMEM, centrifuged at 500 × g, and the cell pellet is suspended in sodium chloride solution (0.9%) for storage at -75°C until analysis [31].

Lipid Extraction and Analytical Methods

Lipid extraction from cells or tissues typically employs a modified Folch extraction method [31]. This procedure involves adding 100 μl of internal standard (1 mg/ml of tetracosanoic acid and 3 mg/ml heptadecanoic acid, dissolved in dichloromethane:methanol, 2:1, v:v) to each sample prior to extraction [31]. The resulting lipid extracts can then be analyzed using various chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques to quantify ALA and its metabolites.

Gas chromatography with flame ionization detection or mass spectrometry is commonly employed for fatty acid profiling, often following transesterification to fatty acid methyl esters. The use of stable isotopically labeled precursors, such as [13C]ALA, allows for precise tracking of metabolic fluxes through various pathways and distinguishes newly synthesized metabolites from pre-existing pools [31]. Advanced lipidomic approaches using liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry enable comprehensive profiling of multiple lipid species and their molecular compositions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ALA Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HepG2 (human hepatoma) | In vitro metabolism studies | Maintain in DMEM + 20% FCS [31] |

| Isotopic Tracers | [13C]ALA-methylesters | Metabolic flux analysis | Suspend in BSA via sonication [31] |

| Chromatography Standards | Tetracosanoic acid, Heptadecanoic acid | Internal standards for quantification | Add prior to Folch extraction [31] |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Dichloromethane:methanol (2:1) | Total lipid extraction | Modified Folch method [31] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | N-MMP, 2,2'-dipyridyl (DPD) | Hme synthesis inhibition | Concentration optimization required [33] |

| Heme Scavengers | Hemopexin (Hx) | Heme sequestration | 0.4 μg/L effective in cucumber [33] |

Factors Influencing Distribution and Incorporation

Dietary and Nutritional Factors

The efficiency of ALA incorporation into tissues and its conversion to longer-chain metabolites is significantly influenced by dietary composition, particularly the balance between n-6 and n-3 fatty acids. Studies have demonstrated that the ratio of linoleic acid (LA) to ALA powerfully impacts the conversion efficiency, with maximum conversion observed at a 1:1 ratio in hepatoma cells [31]. In human studies, lowering dietary LA intake while maintaining constant ALA intake increased EPA concentrations in plasma phospholipids, indicating enhanced conversion efficiency [31].

The absolute amounts of dietary ALA and LA also influence metabolic outcomes, with some research suggesting that these absolute amounts may be more significant than their ratio alone [31]. Other dietary components, including antioxidants, minerals, and macronutrients, further modulate ALA metabolism and incorporation. Natural antioxidants help protect PUFAs from oxidative degradation, which is particularly important for ALA due to its high susceptibility to oxidation resulting from its three double bonds [28].

Physiological and Genetic Modifiers

Multiple physiological and genetic factors significantly impact ALA distribution and cellular incorporation. Gender differences are particularly notable, with women demonstrating higher conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA compared to men, potentially due to regulatory effects of estrogen [30]. This gender difference may be an important consideration in making dietary recommendations for n-3 PUFA intake and in drug development targeting fatty acid metabolism [30].

Genetic polymorphisms in the fatty acid desaturase (FADS) gene cluster significantly influence ALA metabolism, with certain variants associated with more efficient conversion to long-chain metabolites. Other genetic factors, including polymorphisms in elongase enzymes and transcription factors involved in lipid metabolism, further contribute to individual variations in ALA handling. Age, hormonal status, health conditions, and gut microbiota composition represent additional modifiers that influence the ultimate distribution and metabolic fate of dietary ALA.

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutics

Pharmaceutical Targeting of ALA Metabolism

The understanding of ALA tissue distribution and cellular incorporation provides valuable insights for pharmaceutical development, particularly for drugs targeting metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and inflammatory conditions. The regulatory nodes in ALA metabolism, including transcription factors PPARα and SREBP-1c, represent promising therapeutic targets for modulating fatty acid composition and downstream signaling pathways [31]. Drugs that enhance the conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA or that mimic their effects could provide alternatives to marine-derived omega-3 supplements.

The competition between n-6 and n-3 pathways suggests therapeutic potential in modulating the LA/ALA ratio through either dietary interventions or pharmacological approaches that selectively inhibit n-6 metabolism while promoting n-3 incorporation. The development of formulations that enhance ALA stability and bioavailability, such as micro- and nano-encapsulation, represents another promising avenue for therapeutic applications [28].

Biomarker Development and Personalized Nutrition

Quantitative understanding of ALA distribution and incorporation enables the development of biomarkers for assessing omega-3 status and predicting individual responses to interventions. The fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids, erythrocyte membranes, and adipose tissue provides insights into long-term omega-3 status and metabolic efficiency [28]. These biomarkers can stratify patients according to their metabolic phenotypes for personalized nutritional and pharmaceutical interventions.

The tissue-specific differences in ALA incorporation highlight the importance of considering target tissues when evaluating therapeutic efficacy. Interventions aimed at neuroprotection may require different formulations and dosing strategies compared to those targeting cardiovascular benefits, reflecting the distinct distribution patterns and metabolic handling of ALA and its derivatives in different tissues. This nuanced understanding facilitates the development of more targeted and effective therapeutic approaches based on the fundamental principles of ALA distribution and metabolism.

The tissue distribution and cellular incorporation of ALA involve complex, highly regulated processes that determine its ultimate biological effects and health benefits. The liver serves as the primary site for ALA metabolism, converting it to longer-chain, more unsaturated fatty acids that are then distributed to peripheral tissues via specific transport mechanisms. Cellular incorporation involves targeted trafficking to various metabolic fates, including beta-oxidation for energy production, storage in lipid droplets, and integration into membrane phospholipids where it influences membrane properties and signaling functions.

Multiple factors modulate these processes, including dietary composition (particularly the n-6/n-3 ratio), genetic polymorphisms, gender, hormonal status, and health conditions. Understanding these modulators provides opportunities for therapeutic interventions aimed at optimizing ALA distribution and metabolism for specific health outcomes. Continued research in this area, particularly utilizing advanced tracer methodologies and omics technologies, will further elucidate the nuances of ALA handling in biological systems and support the development of targeted nutritional and pharmaceutical approaches for chronic disease prevention and management.

Factors Influencing ALA Bioavailability and Absorption

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA), an endogenous disulfide derivative of octanoic acid, demonstrates significant therapeutic potential for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, oxidative stress management, and metabolic disorders. However, its clinical efficacy is substantially influenced by complex factors affecting its bioavailability and absorption. This technical review comprehensively examines the chemical, biological, and formulation variables that modulate ALA pharmacokinetics, with particular focus on enantiomeric specificity, administration protocols, and advanced delivery systems. The analysis integrates current research findings to provide evidence-based guidance for optimizing ALA bioavailability in research and therapeutic applications, addressing a critical need in the context of ALA metabolism and health benefits research.

Alpha-lipoic acid (1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid) possesses unique physicochemical properties that directly influence its absorption and metabolic fate [34]. As a sulfur-containing compound that functions as an essential cofactor for mitochondrial enzyme complexes, ALA's bioavailability is challenged by several inherent factors: limited gastrointestinal stability, susceptibility to hepatic degradation, and differential handling of its enantiomeric forms [35] [34]. Understanding these fundamental constraints provides the foundation for developing strategies to enhance its therapeutic application.

The molecular structure of ALA, featuring a dithiolane ring with a chiral center at the C6 position, dictates its biochemical behavior [1]. Endogenously, only the R-(+)-enantiomer (R-ALA) is synthesized and functions as a protein-bound cofactor, whereas most supplemental ALA is produced as a racemic mixture (50/50 ratio of R-ALA and S-ALA) [35]. This distinction is critically important because the enantiomers demonstrate different absorption profiles, with human studies showing maximum plasma concentrations of R-ALA are approximately double those of S-ALA following oral administration of the racemic mixture [34].

Key Determinants of ALA Bioavailability

Enantiomeric Form

The stereospecificity of ALA metabolism significantly impacts its bioavailability. The R-enantiomer represents the biologically active form synthesized endogenously and exhibits superior pharmacokinetic properties compared to the S-form [35]. Clinical pharmacokinetic studies demonstrate that R-ALA achieves higher plasma levels and more effectively elevates tissue antioxidant status due to its specific interaction with cellular transport mechanisms and metabolic enzymes [36].

Table 1: Comparative Pharmacokinetics of ALA Enantiomers

| Parameter | R-ALA | S-ALA | Racemic Mixture | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Bioavailability | High (Endogenous form) | Low (Synthetic form) | Intermediate | [35] [34] |

| Plasma Concentration (Cmax) | High (~2× S-ALA) | Low | Moderate | [34] |

| Cellular Uptake | Efficient via specific transporters | Reduced efficiency | Variable | [35] |

| Mitochondrial Targeting | High affinity | Limited affinity | Moderate | [1] [35] |

| Industrial Production Method | Chemical/ enzymatic resolution | Chemical synthesis | Racemization process | [35] |

Administration Factors

Timing Relative to Meals

Administration protocol significantly influences ALA absorption kinetics. Clinical evidence indicates that ALA absorbs best when taken on an empty stomach – specifically at least 2 hours after eating or 30 minutes before a meal [37]. Concurrent food intake, particularly with high-fat meals, can substantially reduce the absorption rate and maximum plasma concentration, potentially through competition with dietary lipids for transport mechanisms or delayed gastric emptying [37].

Dosage and Dosing Regimen

Oral dosage of alpha-lipoic acid in clinical studies ranges from 200 to 1,800 mg daily, with 600 mg established as the standard dose showing optimal balance of efficacy and tolerability [36] [34]. Higher doses do not proportionally increase bioavailability due to saturation of absorption mechanisms and potentially increased first-pass metabolism. Divided dosing regimens (e.g., 300 mg twice daily) may help maintain more stable plasma concentrations while reducing peak-related gastrointestinal side effects [36].

Formulation Advances

Conventional Formulations

Standard ALA supplements are typically available in capsule or tablet forms containing either racemic ALA or R-ALA [36]. These conventional formulations face challenges including susceptibility to oxidation, variable inter-individual absorption, and significant pre-systemic metabolism [38]. Stability maintenance during storage and transport requires protective packaging and potentially stabilizers to prevent degradation that compromises efficacy [38].

Enhanced Bioavailability Formulations

Recent advances in delivery systems aim to overcome ALA's bioavailability limitations:

- Nanoencapsulation: Emerging technologies for 2025 include nanoencapsulation and sustained-release systems designed to improve bioavailability and patient compliance [38]. These systems protect ALA from degradation and enhance cellular uptake.

- Stabilized R-ALA: Specialized formulations using only the R-enantiomer with stabilization technologies to preserve potency [36]. While showing promise, these formulations currently lack the volume of long-term clinical research supporting racemic ALA [36].

- Liposomal Delivery: Phospholipid-based encapsulation that enhances both solubility and absorption while providing protection from gastric degradation [39].

Table 2: ALA Formulation Technologies and Bioavailability Impact

| Formulation Type | Technology Principle | Bioavailability Relative to Standard | Development Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racemic ALA Capsules | Standard 50/50 R/S mixture | Baseline | Clinically established | [36] [34] |

| Stabilized R-ALA | Selective R-enantiomer with stabilizers | Increased (estimated 30-40%) | Commercial availability | [36] |

| Nanoencapsulated ALA | Polymer nanoparticles | Under investigation | Research phase | [38] |

| Liposomal ALA | Phospholipid bilayer encapsulation | Increased (preliminary data) | Early commercial stage | [39] |