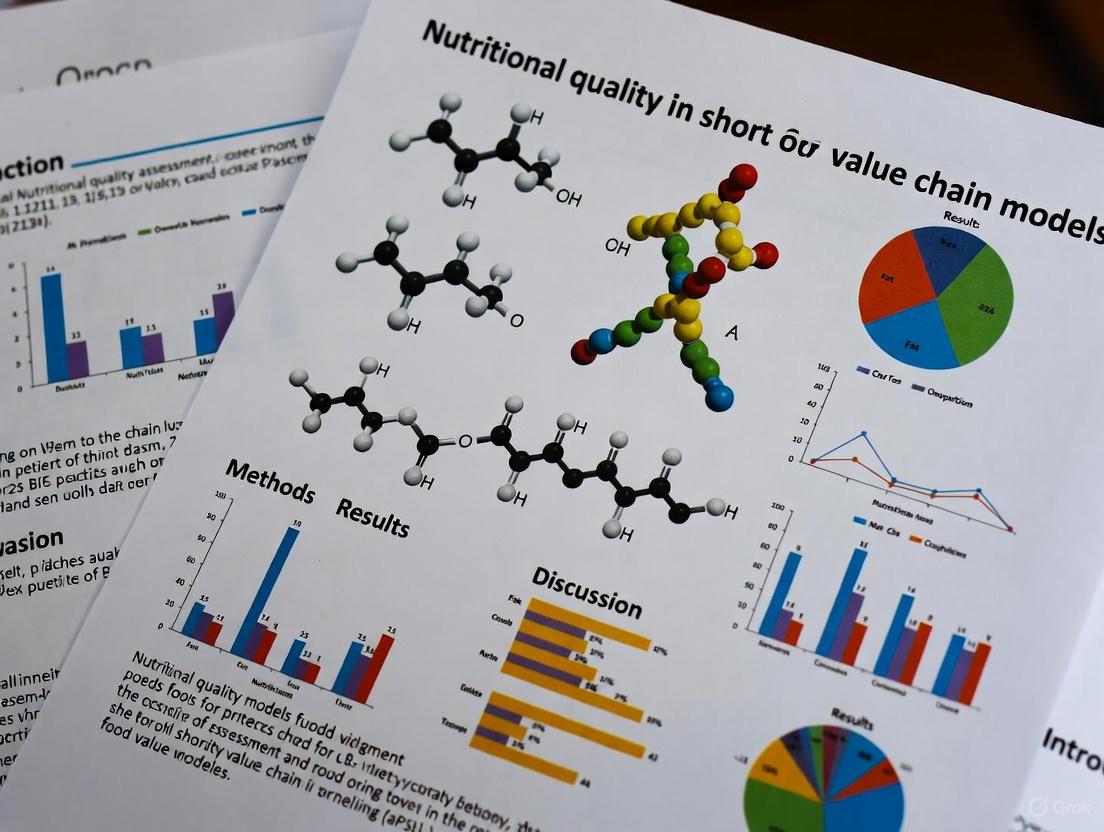

Assessing Nutritional Quality in Short Food Value Chains: Methods, Challenges, and Validation for Sustainable Diets

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nutritional quality assessment within Short Food Value Chain (SFVC) models, a critical nexus for sustainable food systems and public health.

Assessing Nutritional Quality in Short Food Value Chains: Methods, Challenges, and Validation for Sustainable Diets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nutritional quality assessment within Short Food Value Chain (SFVC) models, a critical nexus for sustainable food systems and public health. It explores the foundational role of SFVCs in enhancing diet quality and food security for vulnerable populations. The scope encompasses methodological innovations like Nutritional Life Cycle Assessment (nLCA) and value chain analysis, applied troubleshooting for common barriers such as market access and consumer awareness, and rigorous validation through quality assessment tools and comparative studies. Tailored for researchers and scientists in nutrition and biomedical fields, this synthesis aims to inform the development of evidence-based, effective SFVC interventions that bridge agriculture, nutrition, and health outcomes.

Linking Local Food Systems to Nutrition: The Foundational Role of Short Value Chains

Defining Short Food Value Chains (SFVCs) and Their Relevance to Nutritional Outcomes

This application note provides a structured framework for researching the impact of Short Food Value Chains (SFVCs) on nutritional outcomes. SFVCs, often called local food systems, are business models that emphasize strategic alliances and shared values like healthy food access and farm viability [1]. This document outlines core definitions, presents a quantitative evidence summary, details experimental protocols for assessing nutritional quality, and provides a toolkit for researchers. The content is designed to support the rigorous assessment of SFVCs within a broader thesis on nutritional quality, offering standardized methodologies for data collection and analysis.

Defining Food Value Chains and Sustainability

A Food Value Chain (FVC) comprises all stakeholders involved in the coordinated production and value-adding activities required to make food products [2]. When this system is designed to be profitable at all stages (economic sustainability), delivers broad-based benefits for society (social sustainability), and has a positive or neutral impact on the natural environment (environmental sustainability), it is termed a Sustainable Food Value Chain (SFVC) [2]. This holistic "triple bottom line" approach is central to the SFVC framework [2].

Defining Short Food Value Chains (SFVCs)

Short Food Value Chains (SFVCs) are a specific type of sustainable value chain characterized by a reduced number of intermediaries between producer and consumer. Informally known as local food systems, they are defined by strategic alliances that enhance financial returns through product differentiation aligned with social or environmental values [1]. Core operational values include transparency, strategic collaboration, and a dedication to authenticity [1]. These models are distinct from traditional supply chains due to their embedded emphasis on shared missions such as health equity, farm viability, and environmental stewardship [1].

Quantitative Evidence: Impact of SFVC Models on Nutritional Outcomes

Research on SFVCs has measured their impact on various dietary and health outcomes, particularly among low-income populations. The table below synthesizes key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Short Food Value Chain (SFVC) Models on Nutritional and Health Outcomes

| SFVC Model | Measured Outcome | Key Quantitative Findings | Context & Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers Markets (FMs) [1] | Food Security Status | Increased food security among SNAP participants. | Low-income households in the United States. |

| Fruit and Vegetable (FV) Intake | Increased FV consumption among SNAP participants. | ||

| Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) [1] | Fruit and Vegetable (FV) Intake | Increased vegetable intake among participants. | Diverse participant groups in the United States. |

| Healthcare Utilization | Decreased frequency of doctor's visits and reduced pharmacy expenditures. | ||

| Healthy Eating Behaviors | Improvement in behaviors like eating salads and preparing dinner at home. | ||

| Various SFVC Models [1] | Diet Quality & Health Markers | Less explored or not measured in many studies. Fruit and vegetable intake is the most frequently measured outcome. | Comprehensive review of U.S.-based studies (2000-2020). |

Conceptual Framework and Visual Model

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships within a Short Food Value Chain, from core activities to ultimate impacts on nutrition and health. This systems-based perspective is crucial for research design.

Experimental Protocols for Nutritional Quality Assessment

This section provides detailed methodologies for assessing the nutritional outcomes of SFVC participation, suitable for controlled studies or program evaluation.

Protocol: Measuring Dietary Intake and Food Security

This protocol outlines methods for collecting robust data on primary dietary outcomes.

- Objective: To quantitatively assess the impact of SFVC intervention (e.g., produce prescription, CSA share) on participants' fruit and vegetable intake, overall diet quality, and food security status.

- Study Design: Longitudinal pre-test/post-test design, preferably with a control group.

- Materials:

- Food Security Survey Module: A validated, standardized tool such as the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) [1].

- Dietary Assessment Tools:

- Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ): A self-administered FV-specific FFQ or a comprehensive FFQ to assess overall diet quality.

- 24-Hour Dietary Recall: A more precise, interviewer-administered tool for a detailed snapshot of dietary intake.

- Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment (T0): Prior to SFVC intervention, enroll participants and collect:

- Informed Consent.

- Demographic and socioeconomic data.

- Food security status via the HFSSM.

- Dietary intake data using the chosen FFQ and/or 24-hour recall.

- Intervention Period: Provide the SFVC intervention (e.g., weekly CSA box, financial incentives for FMs) for a defined period (e.g., 6 months). Track participation fidelity.

- Post-Intervention Assessment (T1): Immediately after the intervention ends, re-administer the HFSSM and dietary assessment tools.

- Follow-Up Assessment (T2 - Optional): Conduct a final assessment 3-6 months post-intervention to evaluate sustainability of effects.

- Baseline Assessment (T0): Prior to SFVC intervention, enroll participants and collect:

- Data Analysis:

- Use paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to compare within-group changes from T0 to T1 in FV servings and diet quality scores.

- Use analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare post-intervention outcomes between intervention and control groups, controlling for baseline scores.

- Analyze food security scores as categorical or continuous variables using McNemar's test or related non-parametric tests.

Protocol: Mixed-Methods Analysis of Barriers and Facilitators

This protocol uses qualitative and quantitative data to understand implementation factors.

- Objective: To identify key barriers to and facilitators of participant engagement with SFVC models among low-income households.

- Study Design: Concurrent or sequential mixed-methods design.

- Materials:

- Semi-structured interview or focus group guides.

- Program administrative data (e.g., redemption rates, attendance logs).

- Brief quantitative surveys on usability and satisfaction.

- Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Purposively sample participants from the SFVC program to ensure diversity in engagement levels (e.g., high, medium, low utilizers).

- Data Collection:

- Quantitative: Collect administrative data on program use. Administer surveys measuring barriers (e.g., transportation, cost) and facilitators (e.g., quality, incentives) using Likert scales.

- Qualitative: Conduct in-depth interviews or focus group discussions to explore lived experiences, perceptions, and detailed contextual barriers/facilitators.

- Data Integration: Merge quantitative and qualitative datasets during analysis to triangulate findings.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantitative: Use descriptive statistics (frequencies, means) to summarize survey and administrative data.

- Qualitative: Employ thematic analysis, using a blended inductive-deductive approach to code transcripts and identify major themes (e.g., "Financial Incentives," "Cultural Incongruence," "Community Cohesion") [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key "research reagents" – essential materials and tools – required for conducting rigorous SFVC research.

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Tools for SFVC Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application in SFVC Research |

|---|---|

| Validated Food Security Survey Module (e.g., HFSSM) | A standardized instrument to quantitatively measure household food insecurity, allowing for comparison across studies and populations [1]. |

| Dietary Assessment Tools (FFQ, 24-Hour Recall) | Tools to capture the primary outcome of dietary intake. FFQs are efficient for larger studies, while 24-hour recalls provide more precise dietary data [1]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | A flexible protocol for qualitative data collection, enabling researchers to explore participant experiences, barriers, and facilitators in depth while ensuring key topics are covered [1]. |

| Program Fidelity Checklists | A standardized form to track the consistent implementation of the SFVC intervention (e.g., quality and quantity of produce delivered, accuracy of incentive application) across the study period. |

| Demographic and Socioeconomic Questionnaire | A tool to characterize the study population, control for confounding variables, and conduct subgroup analyses to assess equity impacts. |

SFVCs as a Strategy for Addressing Food and Nutrition Insecurity in Low-Income Populations

Sustainable Food Value Chains (SFVCs) represent a market-oriented, systems-based approach to improving the performance of food systems, with explicit goals of ensuring economic, social, and environmental sustainability while addressing food and nutrition insecurity [3] [4]. Food insecurity, defined as limited or uncertain access to adequate food, disproportionately affects lower socioeconomic and racial/ethnic minority populations and is strongly associated with poor dietary quality and increased diet-related disease risk [5]. The SFVC framework provides a structured methodology to analyze and intervene across the entire food system—from production to consumption—making it particularly relevant for improving nutritional outcomes in low-income populations. This protocol outlines specific assessment methods and intervention strategies to integrate nutritional quality objectives into SFVC development, directly supporting research on short value chain models and their impact on diet-related health disparities.

The Challenge of Food and Nutrition Insecurity

Food insecurity remains a significant public health concern, affecting 10.2% (13.5 million) of U.S. households in 2021, with rates substantially higher among households with children (12.5%), single-parent households, and households headed by Black (19.8%) and Hispanic (16.2%) individuals [5]. While food security focuses on access to sufficient food quantities, nutrition security expands this concept to include "consistent and equitable access to healthy, safe, affordable foods essential to optimal health and well-being" [5]. This distinction is critical, as research consistently demonstrates that food-insecure populations experience higher rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers, partly driven by reduced access to nutritious foods and reliance on energy-dense, nutrient-poor alternatives [5].

Sustainable Food Value Chains as a Solution Framework

The SFVC approach, as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), analyzes the entire food system through three interlinked layers [4]:

- Core Value Chain: Encompasses all actors directly involved from production to consumption.

- Extended Value Chain: Includes providers of supporting goods and services (e.g., seeds, credit, research).

- Enabling Environment: Comprises the policy, regulatory, and natural environments shaping chain operations.

This holistic framework enables researchers and practitioners to identify leverage points for nutritional interventions while considering economic viability, social equity, and environmental sustainability [3] [4]. Evidence from Kenyan value chain actors reveals diverse perspectives on SFVC priorities, ranging from "economic productivity" to "food security and availability" and "environment first" perspectives, highlighting the need for context-specific approaches [6].

Conceptual Framework and Logical Model

The following diagram illustrates the theoretical pathway through which SFVC interventions target improved nutritional outcomes in low-income populations, integrating core SFVC principles with nutritional quality assessment points.

Core Assessment Protocols for Nutritional Quality in SFVCs

Key Indicator Framework for SFVC Nutritional Impact

Comprehensive assessment of SFVC interventions requires multidimensional indicators spanning the value chain. The following table summarizes core metrics for evaluating nutritional outcomes across SFVC components.

Table 1: Nutritional Quality Assessment Framework for SFVC Research

| Assessment Domain | Key Indicators | Data Collection Methods | Target Values/Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Consumption | Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS/WDDS); Fruit & vegetable consumption (servings/day); Nutrient intake adequacy (24-hr recall) | 24-hour dietary recall; Food frequency questionnaire; Household consumption surveys | Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women: ≥5 of 10 food groups; FAO/WHO nutrient intake recommendations |

| Food Environment | Physical access to markets (proximity); Availability of nutrient-dense foods; Affordability of nutritious foods (cost per calorie/nutrient) | GIS mapping; Market inventories; Food price surveys | FAO diet affordability threshold (<52% of household income on food); WHO fruit/vegetable affordability |

| Value Chain Performance | Post-harvest losses (%) of nutritious foods; Time to market for perishables; Nutrient retention at point of consumption | Supply chain tracking; Product testing; Time-motion studies | Post-harvest loss reduction targets (e.g., <5% for fruits/vegetables); <24-48hr for highly perishables |

| Economic Sustainability | Price premiums for nutritious products; Smallholder income from nutrient-dense crops; Consumer food expenditure patterns | Farm-gate price monitoring; Household income/expenditure surveys | Income stability (>30% from diverse sources); Reduced income variability (<15% year-to-year) |

| Social Equity | Women's control over income from nutritious food sales; Participation of marginalized groups; Benefit distribution analysis | Household decision-making surveys; Focus group discussions; Social network analysis | >30% female participation in leadership; Equitable benefit distribution (Gini coefficient <0.4) |

Household-Level Food Security and Nutritional Status Assessment

The USDA Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) provides the gold standard for measuring food insecurity levels, distinguishing between food insecurity (limited access to adequate food) and the more comprehensive nutrition security (access to foods essential for optimal health) [5]. Implementation protocols include:

Standardized Survey Administration

- Apply the 18-item HFSSM adapted to local context through cognitive testing

- Administer at baseline and regular intervals (6-12 months) to track changes

- Supplement with specific nutrition security questions regarding fruit, vegetable, and nutrient-dense food access

- Collect parallel data on household socioeconomic characteristics, including income, education, and demographic composition

Biomarker and Anthropometric Protocols

- For children <5 years: Height-for-age (stunting), weight-for-height (wasting), weight-for-age (underweight) using WHO growth standards

- For adolescents and adults: Body Mass Index (BMI), mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC)

- Micronutrient status assessment: Hemoglobin (Hb) for anemia, with further specific micronutrient testing as resources allow (e.g., ferritin, zinc, vitamin A)

- Standardize measurement techniques across all research sites with regular quality control

Experimental Protocol: Nutritional Impact of SFVC Interventions

Study Design and Implementation Workflow

The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for evaluating the nutritional impact of SFVC interventions, from site selection through to data analysis.

SFVC Intervention Components for Nutritional Improvement

Production-Side Interventions

- Nutritious Crop Promotion: Identify and promote context-specific, nutrient-dense crops (e.g., orange-fleshed sweet potato, iron-rich beans, dark leafy greens) through demonstration plots and input support

- Agroecological Practices: Train farmers in sustainable intensification methods that enhance nutrient density (e.g., soil health management, organic amendments)

- Diversification Incentives: Provide technical and financial support for production diversity, particularly for micronutrient-rich fruits, vegetables, and legumes

Post-Harvest and Processing Interventions

- Nutrient Retention Technologies: Introduce improved storage, handling, and processing methods to minimize nutrient losses (e.g., solar drying, improved storage containers)

- Food Safety Protocols: Implement appropriate technologies to reduce microbial contamination while maintaining nutritional quality

- Fortification Opportunities: Identify potential for small to medium-scale fortification of staple foods at local level where feasible

Market and Distribution Interventions

- Market Linkages for Nutritious Foods: Connect producers of nutrient-dense foods to stable markets through contracts, farmers' markets, or institutional procurement

- Supply Chain Coordination: Improve coordination between actors to reduce time to market for perishable nutritious foods

- Consumer Awareness Campaigns: Implement point-of-purchase information and social marketing to increase demand for nutritious foods

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SFVC Nutritional Assessment

| Item/Category | Specification/Example | Primary Function in SFVC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Tools | USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method; FAO Nutrition Module; HDDS Questionnaire | Standardized measurement of food consumption and dietary diversity at household and individual level |

| Food Composition Tables | FAO/INFOODS Food Composition Table for Biodiversity; USDA FoodData Central; Local FCTs | Nutrient conversion of food consumption data for assessment of nutrient intake adequacy |

| Anthropometric Kits | SECA 213 portable stadiometer; SECA 874 digital scale; WHO color-coded MUAC tapes | Objective assessment of nutritional status across different age groups |

| Biomarker Collection Supplies | HemoCue Hb 201+ system with microcuvettes; DBS cards for micronutrient analysis | Assessment of micronutrient status (e.g., anemia via hemoglobin) |

| GIS and Spatial Analysis Tools | GPS devices; ArcGIS or QGIS software; AccessMod proximity analysis | Mapping food environments, measuring market proximity, and analyzing spatial access to nutritious foods |

| Value Chain Analysis Software | STATA, R, or Python with specialized packages for network analysis | Modeling value chain relationships, performance metrics, and benefit distribution |

| Data Collection Platforms | ODK, SurveyCTO, or KoBoToolbox mobile data collection | Digital data capture in field settings with integration to analytical software |

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Statistical Analysis Plan

Primary Impact Analysis

- Apply difference-in-differences models to estimate intervention effect on primary outcomes (dietary diversity, food security, nutrient intake)

- Use multivariate regression models controlling for relevant covariates (socioeconomic status, education, household composition)

- Implement intention-to-treat analysis with cluster adjustment for community-level interventions

Pathway and Mediation Analysis

- Test hypothesized pathways using structural equation modeling or causal mediation analysis

- Examine mediation through theorized mechanisms (availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability)

- Conduct moderation analysis to identify differential effects across population subgroups

Economic and Sustainability Analysis

- Calculate cost-effectiveness of SFVC interventions for improving nutritional outcomes

- Assess trade-offs and synergies between economic, social, and environmental sustainability dimensions

- Model long-term sustainability through scenario analysis and projection modeling

Interpretation and Knowledge Translation

Contextualizing Findings

- Interpret results within the broader food systems context, considering the interacting systems (energy, trade, health) that influence SFVC performance [4]

- Compare findings across the different perspectives on sustainability identified in SFVC research (economic productivity, food security, environmental protection, transformative knowledge) [6]

- Consider structural determinants (policies, systems, deep-rooted norms) that may facilitate or constrain SFVC impacts on nutrition

Stakeholder Engagement and Research Translation

- Develop tailored communication products for different stakeholders (policymakers, practitioners, communities)

- Engage value chain actors in interpreting findings and developing recommendations

- Co-create practice and policy recommendations with stakeholders to enhance relevance and uptake

This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for researching the impact of Sustainable Food Value Chains on food and nutrition insecurity in low-income populations. By integrating rigorous nutritional assessment methods with a holistic value chain perspective, researchers can generate robust evidence on how to redesign food systems for better nutritional outcomes. The experimental approaches outlined here allow for testing specific mechanisms through which SFVC interventions influence dietary patterns, while also assessing their economic viability and environmental sustainability. As research in this field advances, particular attention should be paid to understanding how different SFVC configurations benefit the most vulnerable populations, and how contextual factors influence implementation and effectiveness across different settings.

The Nutritional Potential of Indigenous and Local Crops in Value Chains

Indigenous and traditional food crops (ITFCs) represent a critical resource for enhancing dietary diversity and nutrition security within sustainable food systems [7]. These crops, which include a variety of vegetables, grains, and legumes native to specific regions, possess remarkable nutritional profiles and environmental resilience [8]. Despite their potential, research indicates that ITFCs remain severely underutilized due to decades of agricultural policy favoring conventional cereal and horticultural crops [7]. This application note provides a structured framework for assessing the nutritional quality of indigenous crops within short value chain models, offering specific protocols and analytical approaches for researchers and food scientists. By integrating rigorous nutritional assessment with value chain analysis, this document aims to support the revitalization of indigenous crops as a strategic response to contemporary challenges of malnutrition, climate change, and food system sustainability [9] [7].

Nutritional Superiority of Indigenous Crops: Quantitative Analysis

Indigenous crops often demonstrate superior nutritional density compared to conventional alternatives, particularly regarding essential micronutrients, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant properties [7] [10]. The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from recent studies analyzing the nutritional composition of selected indigenous crops.

Table 1: Micronutrient and Phytochemical Composition of Selected Indigenous Vegetables

| Crop Name | Scientific Name | Vitamin C (mg/100g) | β-Carotene (mg/100g) | Total Phenolics (mg GAE/100g) | Flavonoids (mg QE/100g) | Antioxidant Activity (IC50 μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghagra | Xanthium strumarium | 22.0 | 0.24 | 136.0 | 50.1 | 12.4 |

| Bathua Red | Chenopodium album | 16.8 | 0.24 | 128.5 | 45.3 | 12.4 |

| Shojne Green | Moringa oleifera | 18.5 | 1.85 | 136.0 | 48.2 | 14.7 |

| Telakucha | Coccinia grandis | 15.2 | 2.05 | 120.3 | 42.7 | 16.2 |

| BARI Lalshak-1 (Control) | Amaranthus tricolor | 14.1 | 1.65 | 115.8 | 38.9 | 18.5 |

Source: Adapted from [10]

Table 2: Mineral Content of Indigenous Crops in Southern Africa and Bangladesh (mg/g)

| Crop Name | Potassium (K) | Calcium (Ca) | Magnesium (Mg) | Iron (Fe) | Zinc (Zn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bambara Groundnut | 45.2 | 12.8 | 8.5 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| Cowpea | 42.7 | 9.3 | 7.8 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Taro | 38.9 | 15.2 | 6.9 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Amaranth | 52.1 | 18.4 | 9.7 | 0.21 | 0.09 |

| Ghagra | 79.4 | 24.6 | 12.3 | 0.28 | 0.11 |

| Bathua | 65.8 | 20.1 | 10.5 | 0.24 | 0.10 |

Sources: Adapted from [8] [10]

The data reveal that indigenous crops constitute significant sources of essential nutrients. For instance, Ghagra (Xanthium strumarium) demonstrates exceptional vitamin C (22.0 mg/100g) and flavonoid content (50.1 mg QE/100g), while Telakucha (Coccinia grandis) shows high β-carotene levels (2.05 mg/100g) [10]. Indigenous crops like amaranth and Bambara groundnut contain substantial amounts of iron and zinc—micronutrients critically important for addressing hidden hunger in vulnerable populations [9]. The high antioxidant activity observed in these crops (IC50 values ranging from 12.4-16.2 μg/mL) further underscores their potential in preventing oxidative stress-related diseases [10].

Comprehensive Nutritional Assessment Protocol

A robust nutritional assessment framework is essential for accurately quantifying the value of indigenous crops within food systems. The following protocol integrates clinical, dietary, and laboratory assessment methods to provide a comprehensive evaluation of nutritional status and food composition.

Clinical and Anthropometric Assessment Components

Patient History and Physical Examination

- Medical History: Document current and past medical conditions, medications, surgical history, and gastrointestinal symptoms that may affect nutritional status [11].

- Dietary History: Record habitual intake, food preferences, restrictive diets, allergies, and factors affecting food intake (e.g., dysphagia, poor dentition) [11].

- Physical Examination: Conduct a systematic physical examination focusing on signs of nutrient deficiencies, including hair loss, skin lesions, gingival bleeding, edema, and neurological changes [11].

- Anthropometric Measurements: Measure height, weight, and calculate Body Mass Index (BMI). For more detailed assessment, include mid-upper arm circumference, waist circumference, and skinfold thickness measurements [11].

Dietary Intake Assessment Methods

24-Hour Dietary Recall

- Procedure: Train researchers to conduct structured interviews using a standardized protocol. Participants recall all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24-hour period, with specific details on preparation methods, portion sizes, and brand names where applicable [11].

- Analysis: Convert reported food consumption to nutrient intake using appropriate food composition databases, preferably those containing indigenous food composition data [12].

- Quality Control: Conduct multiple recalls (including both weekdays and weekends) to account for day-to-day variation in intake. Use food models and household measures to improve portion size estimation accuracy [11].

Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) for Indigenous Foods

- Development: Create a culturally-sensitive FFQ that includes region-specific indigenous crops, traditional preparation methods, and seasonal availability patterns [11].

- Validation: Validate the FFQ against multiple 24-hour recalls or food records in a representative subsample [12].

- Implementation: Administer the FFQ to assess habitual intake patterns over extended periods (typically 3-12 months), with particular attention to seasonal variations in indigenous food consumption [11].

Laboratory Analysis of Indigenous Crop Composition

Sample Preparation Protocol

- Collection: Harvest edible portions of indigenous crops at standard maturity stages from multiple locations to account for environmental variability.

- Processing: Wash with distilled water, pat dry, and separate into components (leaves, stems, roots, seeds) as appropriate.

- Preservation: For fresh analysis, process immediately. For preserved samples, dry at 70°C for 72 hours in a forced-air oven, then grind to a fine powder using a laboratory mill, and store in airtight containers at -20°C until analysis [10].

Phytochemical Analysis Methods

- β-Carotene Extraction and Quantification: Homogenize 1g of sample with 10mL acetone:hexane (4:6 v/v) solution. Filter the supernatant and measure absorbance at 453nm, 505nm, 645nm, and 663nm using a spectrophotometer. Calculate β-carotene content using the established formula: 0.216(OD663) + 0.304(OD505) - 0.452(OD453) [10].

- Total Phenolic Content: Extract phenolics with methanol and quantify using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. Express results as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 100g fresh weight [10].

- Antioxidant Capacity: Assess using DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay. Report results as IC50 values (concentration required to scavenge 50% of DPPH radicals) [10].

- Mineral Analysis: Employ atomic absorption spectroscopy or inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) following microwave-assisted acid digestion of samples [10].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated nutritional assessment workflow for indigenous crops in value chain research:

Value Chain Integration Framework

Integrating nutritional considerations into value chain analysis requires a systematic approach that connects agricultural production with nutrition outcomes. The post-farm-gate value chain framework provides a structured method for assessing how indigenous crops can effectively deliver nutrition to vulnerable populations [13].

Key Requirements for Nutrition-Sensitive Value Chains:

- Food Safety: Ensure indigenous crops remain safe for consumption throughout the value chain, addressing potential contamination points during processing, storage, and distribution [13].

- Nutrient Retention: Implement processing and preservation techniques that maintain nutrient density at the point of consumption, with particular attention to heat-labile vitamins and bioactive compounds [9].

- Adequate Consumption: Ensure sustained adequate consumption of indigenous crops through improved availability, affordability, and acceptability [13].

- Cultural Appropriateness: Respect and incorporate traditional knowledge and preparation methods to enhance acceptability and preserve cultural heritage [7].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnections between value chain components and nutrition outcomes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Indigenous Crop Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Application in Indigenous Crop Research |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Acetone, Hexane, Methanol, Ethanol | Extraction of lipophilic and hydrophilic compounds including carotenoids, phenolics, and flavonoids [10] |

| Spectrophotometry | DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, ABTS | Quantification of antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content [10] |

| Chromatography | HPLC systems with UV/Vis, fluorescence, and MS detectors | Separation and quantification of specific vitamins, phenolic compounds, and metabolites [12] |

| Elemental Analysis | Nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide, certified reference materials | Sample digestion for subsequent mineral analysis via AAS or ICP-OES [10] |

| Food Composition Databases | FAO/INFOODS, USDA FoodData Central, regional databases | Converting food consumption data to nutrient intake, requiring expansion with indigenous crop data [12] |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | Automated 24-hour recall systems, image-assisted dietary assessment | Accurate quantification of dietary intake with reduced respondent burden [12] |

| Biomarker Assays | ELISA kits for nutritional status markers (ferritin, retinol-binding protein) | Objective validation of dietary intake data and nutritional status assessment [12] |

The systematic assessment of indigenous crops' nutritional potential within value chains offers transformative opportunities for addressing multiple dimensions of food and nutrition insecurity. The protocols and frameworks presented in this application note provide researchers with standardized methodologies for generating comparable data on the nutritional composition of indigenous crops and their impact pathways through food systems. Future research should prioritize filling critical knowledge gaps, including comprehensive phytochemical profiling of neglected indigenous crops, monitoring nutrient retention across value chain stages, and evaluating the health impacts of increased indigenous crop consumption through intervention studies. By applying these assessment protocols within nutrition-sensitive value chain frameworks, researchers can generate the evidence base needed to inform policies and investments that leverage indigenous crops for healthier, more sustainable, and resilient food systems.

Short Food Value Chains (SFVCs) are market-based interventions that can enhance food security and nutritional outcomes by strengthening the linkages between producers and consumers [14]. The core premise of SFVCs is the reorganization of food distribution to encompass shorter, more transparent, and often localized pathways. This document provides detailed Application Notes and Protocols for researchers assessing the nutritional quality within SFVC models, with a specific focus on methodological frameworks and experimental procedures for evaluating impact pathways on vulnerable populations. Nutrient-dense foods—those rich in vitamins, minerals, and other health-promoting components with little added sugars, saturated fat, or sodium—are critical for combating the global burden of malnutrition, particularly among biologically vulnerable groups such as infants, young children, and women of reproductive age [15] [16]. The following protocols are designed to generate robust, quantitative data on how SFVCs contribute to the consistent availability, accessibility, and consumption of these foods.

Application Notes: Conceptual Framework and Key Metrics

The SFVC-Nutrition Impact Pathway

The pathway from SFVC operation to improved nutritional intake is conceptualized as a multi-stage process. The framework posits that SFVC activities generate primary value (economic, managerial, relational, organizational) and secondary values (social, environmental, ethical, cultural) [14]. These values, in turn, influence key mediators—Food Availability, Affordability, Acceptability, and Safety—that must be optimized to deliver substantive and sustained consumption of nutrient-dense foods to target populations [17]. Success requires that food is safe to eat on a sustained basis, nutrient-dense at the point of consumption, and consumed in adequate amounts [17]. The diagram below illustrates this logical pathway and its components.

Defining Assessment Domains and Metrics

Robust assessment requires quantitative and qualitative metrics across key domains. The following table synthesizes critical assessment domains, corresponding metrics, and data sources for evaluating SFVC performance and nutritional impact. These metrics are aligned with the conceptual impact pathway and are essential for measuring progress toward improved nutrition.

Table 1: Key Assessment Domains and Metrics for SFVC Nutritional Impact

| Assessment Domain | Specific Metric | Data Collection Method | Target Value or Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value Chain Performance | Ratio of producer price to consumer price | Structured interviews with producers and consumers [2] | >40% return to producer |

| Number of direct transactions per month | Sales ledger analysis [14] | Context-dependent baseline | |

| Food Environment | Availability of ≥5 food groups from priority list | Structured retailer audit [16] | 100% of outlets |

| Price index of a nutrient-dense food basket | Price survey compared to conventional retail [16] | ≤110% of conventional basket price | |

| Consumer Engagement | Self-reported trust in producer | Likert-scale survey (1-5) [14] | ≥4.0 average score |

| Awareness of product origin and practices | Structured survey with open-ended questions [14] | ≥80% of consumers can accurately describe | |

| Nutritional Intake | Dietary Diversity Score (e.g., WDDS) | 24-hour dietary recall [15] | ≥5 food groups for women of reproductive age |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Consumer Nutrition Environment in SFVCs

1. Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the in-store availability, price, quality, and promotion of nutrient-dense foods in SFVC retail points (e.g., farm stands, farmers' markets) compared to conventional retail outlets.

2. Experimental Workflow: The following workflow outlines the key steps for executing this audit protocol, from preparation and sampling through to data analysis.

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Tablet/Clipboard & Pens: For digital or paper-based data collection.

- Standardized Audit Tool: A modified tool based on existing nutrient-dense food and sustainability measurements [16]. The tool should be a checklist or questionnaire.

- Calibrated Digital Scale: For measuring product weight to calculate price per 100g.

- Camera (optional): For documenting product placement and promotional materials.

4. Procedure:

- Tool Selection & Training: Select or adapt a validated consumer nutrition environment audit tool [16]. Train data collectors to a high inter-rater reliability (≥90% agreement).

- Sampling: Identify a representative sample of SFVC outlets (e.g., 10 farmers' markets) and a matched sample of conventional stores (e.g., 10 supermarkets) from the same geographic area.

- Data Collection - Availability:

- Data Collection - Price & Quality:

- For each available item, record the price and unit. Standardize all prices to a common unit (e.g., price per 100g).

- Assess the quality of a subset of perishable items (e.g., fruits, vegetables) using a standardized scale (e.g., 1=poor, 5=excellent).

- Data Analysis:

- Compare mean availability scores and standardized prices between SFVC and conventional outlets using independent samples t-tests.

- Calculate a "healthy food basket" cost for each outlet type and compare.

1. Objective: To assess the contribution of foods purchased through SFVCs to the dietary diversity and nutrient intake of vulnerable individuals in target households.

2. Experimental Workflow: This protocol outlines the steps for conducting household-level surveys to measure dietary intake and trace its sources.

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Dietary Data Collection Software: e.g., FAO's Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) calculator, or ODK-based forms.

- Food Models and Measuring Aids: To assist in portion size estimation.

- Structured Questionnaire: Includes modules for 24-hour recall and food source attribution.

4. Procedure:

- Subject Recruitment: Recruit a cohort of households from the target vulnerable group (e.g., with pregnant women or young children) [15]. Obtain informed consent.

- 24-Hour Dietary Recall:

- Conduct a quantitative 24-hour dietary recall with the primary caregiver or vulnerable individual.

- For each food and beverage consumed, record the type, amount, and time of consumption.

- Food Source Attribution:

- For each food item reported, ask the respondent to identify its primary procurement source. Use predefined categories: "SFVC (direct purchase)", "Conventional Market", "Own Production", "Other".

- Data Processing:

- Calculate the Women's Dietary Diversity Score (WDDS) or other appropriate diversity score for each respondent.

- Categorize food items by source.

- Calculate the proportion of total food consumption (by count or food group) attributable to SFVC sources.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use multivariate regression analysis to test for an association between the proportion of food from SFVCs and dietary diversity scores, controlling for confounders like household income and education.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and tools required for the experimental protocols described in this document.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SFVC Nutritional Assessment

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification/Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Audit Tool | Quantifies availability, price, and quality of nutrient-dense foods in retail environments. | Must be a validated checklist assessing core food groups; should demonstrate high inter-rater reliability [16]. |

| Dietary Assessment Software | Facilitates accurate and efficient collection and analysis of 24-hour dietary recall data. | Software capable of calculating dietary diversity scores (e.g., WDDS) and nutrient intake; mobile data entry is preferred for field use. |

| Food Source Attribution Module | A standardized survey module to trace the origin of consumed foods. | Integrated into the dietary assessment tool; must have clear, locally relevant source categories (e.g., "Farmers' Market", "Community Supported Agriculture"). |

| Geospatial Mapping Tool | Documents and analyzes the geographic proximity of target populations to SFVC outlets. | Software (e.g., QGIS) capable of plotting participant households and SFVC locations to calculate access metrics. |

| Data Collection Toolkit | Physical materials for field data collectors. | Includes tablets (preferred) or clipboards, calibrated weighing scales, and visual aids for portion size estimation. |

Tools and Techniques: Methodological Approaches for Nutritional Assessment in Value Chains

The ecological transition of the food supply chain requires measurement tools that integrate environmental and nutritional dimensions effectively [18]. Nutritional Life Cycle Assessment (nLCA) has emerged as a significant evolution of the traditional Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), moving beyond the limitation of impact analysis based purely on mass units (e.g., kilograms of product) [18]. This approach addresses the primary function of food—nutrition—by assessing the environmental impact required to provide a specific nutritional function [18]. For researchers investigating short food supply chains (SFSCs) and their sustainability claims, nLCA offers a scientifically robust methodology to evaluate whether shortened chains genuinely deliver enhanced nutritional outcomes relative to their environmental footprints [19] [20].

This protocol outlines detailed methodologies for implementing nLCA within the context of SFSC research, providing practical tools for assessing the complex interplay between food production, nutritional quality, and environmental sustainability.

Background: The Evolution from LCA to nLCA

Limitations of Traditional LCA

Traditional Life Cycle Assessment follows ISO 14040 and 14044 standards but presents a critical discretionary degree in choosing the reference measurement unit for impacts (the Functional Unit, FU) [18]. In food system analyses, the chosen FU is typically 1 kg of product or a standard package. While practical for comparing similar products, this approach becomes misleading when comparing foods with vastly different nutritional values, as the quantities required to provide equivalent nutrient intakes vary considerably [18].

Conceptual Foundation of nLCA

Nutritional LCA represents a paradigm shift by integrating nutritional parameters into traditional environmental impact indicators [18]. The functional unit no longer considers only the physical quantity of food but also its nutritional function—the contribution of energy, proteins, or micronutrients to human health [18]. This approach is crucial for addressing the 'triple challenge' of obesity, malnutrition, and climate change, guiding the transition toward truly healthy and sustainable diets [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional LCA and Nutritional LCA Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional LCA | Nutritional LCA |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Unit | Mass-based (kg, liter) | Nutrition-based (nutrient content, nutrient density score) |

| Primary Focus | Environmental impact per physical unit | Environmental impact per unit of nutritional value |

| Nutritional Consideration | Limited or absent | Central to assessment methodology |

| Comparison Basis | Fair for similar products | Enables cross-category food comparisons |

| Health Implications | Indirect or separate assessment | Directly integrated into environmental metrics |

Methodological Approaches for nLCA

Defining Nutritional Functional Units (nFU)

The core innovation in nLCA involves replacing mass-based functional units with nutritional functional units (nFUs). Several approaches have emerged, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Single-nutrient nFU: Focuses on environmental impact per unit of specific nutrients (e.g., per 100g of protein, per 100mg of calcium) [21]. This approach was applied in a study of Breton pâté production, which compared carbon footprints under mass-based (100g product), energy-based (kcal), and nutrition-based (protein) functional units [21].

- Composite indicator nFU: Utilizes nutrient density scores incorporating multiple nutrients [21]. The Qualifying Index (QI) represents one such approach, expressing the relation between nutrient density and energy density as a dimensionless value [22].

- Dietary-context nFU: Analyzes the marginal contribution of a commodity to the overall nutritional value of a specific diet [21].

The Qualifying Index (QI) Methodology

A novel approach proposed by researchers involves maintaining the mass-based FU while adjusting it for nutritional value using a dimensionless Qualifying Index (QI) [22]. The QI is calculated as follows:

[ QI=\frac{{E}{d}}{{E}{p}} \times \frac{\sum{j=1 }^{{N}{q}}\frac{{a}{q,j}}{{r}{q,j}}}{{N}_{q}} ]

Where:

- (E_d) = average daily energy needs of the population group (kcal)

- (E_p) = energy in the amount of food analyzed (kcal)

- (a_{q,j}) = amount of qualifying nutrient j in the amount of food analyzed

- (r_{q,j}) = recommended daily intake (RDI) of qualifying nutrient j

- (N_q) = number of qualifying nutrients considered

Table 2: Selected Qualifying Nutrients for QI Calculation by Food Group

| Food Group | Selected Qualifying Nutrients |

|---|---|

| Protein Foods (dairy, meat, fish, eggs, legumes, nuts) | Protein, vitamin B12, calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin D |

| Grain Foods (bread, pasta, rice, potatoes) | Fiber, iron, magnesium, selenium, B vitamins |

| Fruits & Vegetables | Vitamin C, vitamin A, folate, potassium, fiber |

| Fats & Oils | Vitamin E, essential fatty acids |

This approach enables a more comprehensible link to the original mass-based FU while accounting for nutritional density, with foods scoring QI > 1 considered nutrient-dense and QI < 1 considered energy-dense [22].

System Expansion for Multifunctionality

Food items possess multifunctionality—they provide multiple nutrients simultaneously. System expansion, preferred by LCA standards for handling multifunctionality, has been applied to nLCA to compare different protein sources [23]. This approach defines the primary function (e.g., provision of balanced amino acids) while treating additional functions (e.g., energy provision) as "by-products" that can substitute for other food items in the diet [23].

Experimental Protocols for nLCA Implementation

Protocol 1: Comprehensive nLCA for SFSC Products

Objective: To assess the environmental impacts of short food supply chain products per unit of nutritional value delivered.

Materials and Reagents:

- Food samples from SFSC and conventional supply chains

- Nutritional analysis kits or access to food composition databases

- LCA software (e.g., OpenLCA, SimaPro) with agri-food databases

- Environmental impact data (primary or secondary)

Procedure:

- Define System Boundaries: Cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-consumer, including production, processing, packaging, and distribution.

- Compile Life Cycle Inventory: Collect data on resource inputs and environmental emissions for all processes within system boundaries.

- Conduct Nutritional Analysis:

- Analyze proximal composition (protein, fats, carbohydrates)

- Quantify micronutrients relevant to the food category

- Calculate nutrient density scores using appropriate methods

- Select nFU: Choose appropriate nutritional functional units based on research objectives:

- Single nutrient (e.g., protein, iron)

- Composite index (e.g., Qualifying Index, Nutrient Rich Food index)

- Food-group-specific indicators

- Calculate Environmental Impacts: Apply LCIA methods (e.g., IPCC for climate change, Water scarcity index) using both mass-based and nutrition-based FUs.

- Interpret Results: Compare environmental impacts per nutritional unit across products and supply chain models.

Protocol 2: Assessing Protein Quality in nLCA

Objective: To evaluate environmental impacts of protein sources accounting for protein quality differences.

Materials:

- Protein sources (animal and plant-based)

- Amino acid analysis capabilities

- Digestibility assessment methods (in vitro or in vivo)

- DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score) calculation tools

Procedure:

- Determine Protein Quantity: Measure crude protein content using standard methods (e.g., Kjeldahl, Dumas).

- Analyze Amino Acid Profile: Quantify essential amino acids using HPLC or GC-MS.

- Assess Digestibility: Apply in vitro digestibility assays or consult published DIAAS values.

- Calculate Protein Quality-Adjusted nFU: Adjust protein quantity by quality metrics (e.g., DIAAS score).

- Conduct LCA: Calculate environmental impacts per unit of quality-adjusted protein.

- Compare Sources: Evaluate different protein sources using the quality-adjusted nFU.

Visualization of nLCA Workflows

Comprehensive nLCA Methodology

Application in Short Food Supply Chain Research

Contextualizing nLCA in SFSCs

Short food supply chains have emerged as sustainable alternatives to traditional food systems, though their sustainability lacks scientific consensus [19]. The integration of nLCA within SFSC research enables evidence-based evaluation of whether shortened supply chains enhance the nutritional-environmental efficiency of food systems.

Case studies like the Km0 Newsstand project in Italy demonstrate innovative SFSC models that commercialize local agri-food products through traditional retail structures [20]. Applying nLCA to such initiatives can quantify whether the valorization of local biocultural heritage translates into tangible nutritional advantages relative to environmental impacts.

Practical Implementation Framework

For researchers investigating SFSCs, we recommend the following nLCA implementation framework:

Characterize SFSC Model Attributes:

- Number of intermediaries (direct sale vs. one intermediary)

- Geographical proximity between production and consumption

- Distribution logistics and storage conditions

- Information flow and traceability systems

Select Appropriate nFU:

- For commodity comparisons: Use composite indices (e.g., QI)

- For specific nutrient focus: Use single-nutrient nFU

- For protein sources: Include quality adjustments (DIAAS)

Account for SFSC-Specific Factors:

- Potential nutritional quality differences due to minimal processing

- Reduced storage and transportation impacts on nutrient retention

- Seasonal variations in nutritional content

Conduct Comparative Assessment:

- Compare nLCA results between SFSC and conventional products

- Identify trade-offs between different environmental impact categories

- Evaluate nutritional-environmental hotspots within the supply chain

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for nLCA Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software | Modeling environmental impacts across life cycle stages | OpenLCA, SimaPro, GaBi |

| Agri-food LCA Databases | Source of secondary data for agricultural inputs | Agribalyse, Ecoinvest, USDA databases |

| Food Composition Databases | Nutritional composition data for nFU calculation | FAO/INFOODS, USDA FoodData Central, national databases |

| Nutritional Analysis Kits | Quantifying specific nutrients in food samples | Kjeltech for protein, HPLC for amino acids, ICP-MS for minerals |

| Environmental Impact Methodologies | Standardized impact assessment | IPCC GWP100, ReCiPe, AWARE water scarcity |

| Protein Quality Assessment Tools | Evaluating protein digestibility and amino acid profile | DIAAS calculation protocols, in vitro digestibility assays |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Handling variability and uncertainty in results | R, Python, SAS with specialized packages for LCA |

Nutritional LCA represents a methodological advancement that enables more meaningful sustainability assessments of food systems by integrating nutritional dimensions with environmental impacts. For researchers focused on short food supply chains, nLCA offers a robust framework to evaluate whether supply chain shortening correlates with improved nutrition-environment efficiency. The protocols and methodologies outlined provide practical guidance for implementing nLCA in diverse research contexts, particularly for assessing the sustainability claims of alternative food network models.

Future methodological development should address challenges in nutrient bioavailability, processing effects, and dietary context to further enhance nLCA's applicability to SFSC research. As food system transformation accelerates, nLCA will play an increasingly vital role in guiding evidence-based decisions toward truly sustainable and nutritious food systems.

The Nutrient Index-based Sustainable Food Profiling Model (NI-SFPM) for Product-Level Analysis

The global food system stands at the intersection of human health and environmental sustainability, facing the dual challenge of ensuring nutritional security while operating within planetary boundaries. The Nutrient Index-based Sustainable Food Profiling Model (NI-SFPM) emerges as a novel methodological framework designed to facilitate product-level sustainability assessments by integrating nutritional adequacy with environmental impact evaluation [24] [25]. This approach represents a significant advancement in sustainable food system research, enabling precise quantification of how individual food products contribute to nutritionally adequate and environmentally sustainable diets.

The development of NI-SFPM responds to critical limitations in conventional life cycle assessment (LCA) methodologies, which typically utilize functional units based on mass or volume rather than the true function of food – to provide nutrition [21]. Within the context of research on short value chain (SVC) models, this model offers powerful applications for evaluating how localized food production and distribution systems contribute to nutrition security and environmental sustainability. SVC models, including farmers markets, community-supported agriculture, and food hubs, prioritize values of "transparency, strategic collaboration, and dedication to authenticity" while optimizing resources across the supply chain [1]. The NI-SFPM provides the analytical rigor needed to quantify the sustainability performance of products moving through these alternative food networks.

Theoretical Foundation and Model Architecture

Conceptual Framework

The NI-SFPM is methodologically grounded in the integration of two advanced LCA approaches: nutritional Life Cycle Assessment (nLCA) and planetary boundary-based LCA (PB-LCA) [24] [25]. This hybrid model evaluates food products against their assigned share of planetary boundaries while accounting for their nutritional contribution, thereby aligning with the criteria of the planetary health diet concept.

The model architecture operates on the principle that environmentally sustainable and nutritionally adequate food consumption can include a wide selection of foods, but requires detailed information on individual food products to enable truly sustainable choices [24]. This product-level focus is particularly valuable for SVC research, as it allows for direct comparison between locally-sourced products and conventional alternatives, providing evidence for the potential benefits of shortened value chains.

Key Components and Metrics

The NI-SFPM incorporates six critical environmental impact categories corresponding to planetary boundaries:

- Climate change

- Nitrogen cycling

- Phosphorus cycling

- Freshwater use

- Land-system change

- Biodiversity loss [24] [26]

On the nutritional side, the model employs a Nutrient Index that captures the composite nutritional value of food products, moving beyond single-nutrient assessments to provide a more holistic evaluation of nutritional quality [24].

Table 1: Core Environmental Impact Categories in NI-SFPM

| Impact Category | Measured In | Planetary Boundary Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | kg CO₂-equivalent | Global carbon budget |

| Nitrogen Cycling | kg N applied | Planetary nitrogen boundary |

| Phosphorus Cycling | kg P applied | Planetary phosphorus boundary |

| Freshwater Use | m³ water consumed | Freshwater use boundary |

| Land-System Change | m² land use | Land system change boundary |

| Biodiversity Loss | Potential species loss | Biodiversity integrity boundary |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Implementing the NI-SFPM requires specific data resources and analytical tools. The following table outlines key research reagents and computational resources essential for applying this model in research settings, particularly for SVC investigations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for NI-SFPM Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Application in NI-SFPM |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Analysis | Nutritics Software, McCance & Widdowson's Composition of Foods | Nutrient composition analysis and conversion of recipe quantities to standardized units [27] |

| LCA Databases | Agribalyse 3.1, Agri-footprint 6.3, World Food LCA Database (WFLDB), Ecoinvent 3.1 | Environmental impact inventory data for food production processes [27] |

| LCA Calculation Software | Simapro 9 with Environmental Footprint Method | Impact assessment calculations using standardized methods [27] |

| Planetary Boundary References | Steffen et al. 2015 planetary boundaries framework | Normalization of environmental impacts against safe operating spaces [24] |

| Nutrient Profiling Models | Ofcom Nutrient Profiling Model, Nutrient Rich Food Index | Composite nutritional scoring for food products [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Compilation Protocol

Objective: To systematically gather and process the required nutritional and environmental data for food products within SVC models.

Materials: Nutritional composition database access, LCA database subscriptions, appropriate computational resources.

Procedure:

- Product Identification and Categorization:

- Compile a comprehensive list of food products for assessment, ensuring representation across relevant categories (e.g., fruits, vegetables, animal proteins, grains).

- For SVC research, include both locally-sourced and conventional counterparts for comparative analysis.

Nutritional Data Acquisition:

- Obtain nutrient composition data for each product using standardized databases (e.g., McCance & Widdowson's composition of foods).

- Capture data for all relevant nutrients, including macronutrients, vitamins, minerals, and bioactive compounds.

- Convert all quantities to per-portion metrics using standardized conversion factors for cooked and prepared states [27].

Environmental Inventory Data Collection:

- Collect life cycle inventory data for each product using established LCA databases.

- For SVC-specific assessments, modify default data to reflect local production practices, transportation distances, and processing methods.

- Ensure system boundaries are consistently applied (typically farm-to-shelf for meals and cradle-to-grave for individual items) [27].

NI-SFPM Calculation Protocol

Objective: To compute the integrated sustainability score for each food product by combining nutritional and environmental metrics.

Materials: Processed nutritional and environmental data, statistical software, NI-SFPM calculation algorithm.

Procedure:

- Nutritional Index Calculation:

- Calculate nutrient density scores using an appropriate nutrient profiling model (e.g., Ofcom NPM).

- Apply semi-qualitative scaling using established cut-off points (e.g., Nutri-Score cut-offs) [27].

- Normalize scores to a standardized scale (0-100) for comparability.

Environmental Impact Assessment:

- Calculate characterized environmental impacts for each of the six impact categories using LCA methodology.

- Normalize impacts against corresponding planetary boundaries to derive relative environmental performance [24].

- Apply weighting based on the relative importance of each impact category, considering equal weighting (1:1 ratio) as a default [27].

Composite Score Integration:

- Combine nutritional and environmental scores using a composite indicator approach.

- Apply equal weighting (1:1) to nutrition and environmental components unless specific research questions warrant differential weighting.

- Calculate final NI-SFPM scores using arithmetic or geometric mean, with sensitivity analysis to assess methodological uncertainty [27].

Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Perform Monte-Carlo simulations (e.g., 10,000 iterations) to estimate confidence intervals for product rankings.

- Conduct global sensitivity analysis to determine individual contribution of each input's uncertainty [27].

- Test robustness through alternative aggregation procedures (arithmetic vs. geometric mean), normalization methods (min-max vs. z-score), and weighting variations (±25% of initial values).

Application to Short Value Chain Research

SVC-Specific Implementation Framework

The NI-SFPM offers particular utility for investigating the sustainability implications of shortened value chains, which are characterized by fewer intermediaries between producers and consumers and enhanced operational transparency [1]. When applying NI-SFPM in SVC research contexts, several methodological adaptations enhance its relevance:

Data Collection Modifications:

- Gather primary production data directly from SVC participants to capture distinctive practices (e.g., reduced transportation, alternative packaging, diversified cropping systems).

- Incorporate social sustainability indicators where possible, acknowledging that comprehensive sustainability assessments extend beyond environmental and nutritional dimensions.

Comparative Analytical Framework:

- Implement paired comparisons between products from SVCs and conventional supply chains to isolate the effect of value chain structure.

- Conduct subgroup analyses to identify SVC types (farmers markets, CSAs, food hubs) with the strongest sustainability performance.

Table 3: SVC-Specific Parameters for NI-SFPM Adaptation

| SVC Characteristic | NI-SFPM Implementation | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Food Miles | Modified transportation inventory in LCA | Quantification of climate change impact reduction |

| Seasonal Production | Temporal alignment in nutritional assessment | Evaluation of nutrient density variation across seasons |

| Direct Producer-Consumer Relationships | Primary data collection opportunities | Enhanced data accuracy and reduced uncertainty |

| Sustainable Farming Practices | Differentiated agricultural inputs in LCA | Isolation of production method effects on environmental impacts |

| Niche Marketing and Product Differentiation | Customized product categorization | Ability to assess unique or heritage varieties |

Protocol for SVC Intervention Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the impact of SVC interventions on nutritional and environmental outcomes using NI-SFPM.

Materials: Primary data from SVC operations, control groups from conventional chains, statistical analysis software.

Procedure:

- Intervention Mapping:

- Identify specific SVC interventions to evaluate (e.g., farmers market nutrition incentive programs, CSA subscriptions for low-income households, farm-to-school initiatives).

- Document intervention components using standardized frameworks to enable replication.

Participant Recruitment and Sampling:

- Employ stratified sampling to ensure representation across relevant demographic groups and SVC types.

- Establish appropriate control groups matched for key characteristics but not participating in SVC interventions.

Baseline Data Collection:

- Administer dietary intake assessments (e.g., 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires) to establish baseline consumption patterns.

- Collect food source information to determine conventional vs. SVC product proportions.

Longitudinal Assessment:

- Implement repeated measures design with data collection at predetermined intervals (e.g., pre-intervention, 3 months, 12 months).

- Track changes in food procurement patterns, specifically documenting shifts from conventional to SVC sources.

NI-SFPM Application:

- Apply the NI-SFPM to all reported food items, using SVC-specific data where available.

- Calculate overall diet-level sustainability scores by aggregating product-level results.

- Analyze changes in nutritional quality, environmental impact, and composite sustainability scores.

Mixed-Methods Integration:

- Collect qualitative data on barriers and facilitators to SVC participation, including program awareness, accessibility, cultural congruence, and financial incentives [1].

- Integrate quantitative sustainability metrics with qualitative insights to develop comprehensive implementation frameworks.

Validation and Performance Assessment

The NI-SFPM has been validated through application to 559 food products across diverse food categories, demonstrating effectiveness in discriminating between products and categories based on environmental performance and nutrient composition [24] [25]. The resulting sustainability rankings align with current scientific understanding of healthy and sustainable diets, providing evidence of construct validity.

For SVC applications, additional validation steps are recommended:

- Convergent Validity Assessment: Correlate NI-SFPM scores with independent sustainability metrics to verify consistent classification.

- Predictive Validity Testing: Evaluate whether NI-SFPM scores predict relevant health and environmental outcomes in longitudinal studies.

- Stakeholder Face Validity: Engage SVC stakeholders (producers, consumers, policymakers) in assessing the relevance and interpretability of NI-SFPM results.

The model's sensitivity has been rigorously tested through Monte-Carlo simulations, examining uncertainties in aggregation procedures, normalization methods, and weighting schemes [27]. These analyses confirm the robustness of product rankings across methodological variations, supporting the reliability of findings derived from NI-SFPM applications in SVC research.

Value Chain Analysis Frameworks for Tracing Nutritional Quality from Farm to Consumer

The global food system is increasingly challenged by a convergence of environmental, economic, and social disruptions—what is now described as a "polycrisis," where multiple, interconnected crises interact in compounding ways [28]. Within this context, Short Food Supply Chains (SFSCs) have gained renewed attention in agricultural economics and policy as locally embedded, socially inclusive, and environmentally responsive alternatives to traditional industrialized food systems [28]. The analysis of nutritional quality within these SFSCs requires specialized value chain frameworks that can trace nutritional attributes from production to consumption while accounting for sustainability, equity, and economic viability.

The transition of food systems towards more sustainable organizational models has increasingly highlighted the pivotal role of SFSCs in enhancing the unique characteristics of local food products [28]. These alternative supply chains address the growing demand for diversified consumption, driven by both socio-economic and cultural factors, while potentially offering superior nutritional quality through reduced processing and shorter time from farm to table.

Table 1: Current Malnutrition Burdens and Economic Impacts

| Metric | Global Impact | Economic Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Micronutrient deficiencies | 2 billion people lack essential micronutrients | $21 trillion in lost human capital productivity |

| Childhood stunting | 1 in 5 children projected to be stunted by 2030 | Significant healthcare and development costs |

| Overweight/Obesity | Nearly 3 billion adults affected | $20 trillion estimated costs over next decade |

Conceptual Framework for Nutritional Quality Assessment

The consumer-focused food systems for healthy diets framework from IFPRI's 2024 Global Food Policy Report provides a comprehensive structure for analyzing nutritional quality across value chains [29]. This framework positions policy and governance as the foundational element, emphasizing that the rules, institutions, and coordination mechanisms that guide how different sectors work together are crucial for promoting sustainable food systems and healthy diets.

Multi-Dimensional Value Creation in SFSCs

Value creation in short food supply chains extends beyond mere economic transactions to encompass primary and secondary value dimensions [14]. Primary value is absorbed by supply chain actors and includes:

- Managerial dimension: Approaches and techniques for managing the supply chain

- Relational dimension: How relationships are built within the supply chain systems

- Economic dimension: Financial performance metrics

- Organizational dimension: Organizational styles and mindsets

Secondary values extend beyond supply chain boundaries in the form of social, environmental, ethical, and cultural benefits [14]. These include:

- Cultural dimension: The cultural fundamentals guiding the supply chain system

- Social dimension: Social activities and practices governing business conduct

- Ethical dimension: Ethical principles typifying operational philosophy

- Environmental dimension: Ecological codes of practice directing the system

Sustainability Evaluation Framework

A systematic literature review reveals that sustainability evaluation of SFSCs requires specialized indicators tailored to the needs and constraints of stakeholders [19]. The analysis reveals a focus on quantitative evaluations, mainly in occidental countries, with emphasis on farmers and supply chain configurations with maximum one intermediary. The economic and environmental pillars are the most assessed, while some social themes are less studied, indicating a research gap in comprehensive nutritional quality assessment.

Table 2: Key Sustainability Indicators for Nutritional Quality Assessment in SFSCs

| Pillar | Indicator Category | Specific Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | Affordability | Price premium for nutritious foods, Cost of diverse diet |

| Value Distribution | Percentage of final price reaching producer | |

| Environmental | Production Methods | Organic certification, Agroecological practices |

| Biodiversity | Crop diversity index, Varietal diversity | |

| Social | Access | Physical access to markets, Economic accessibility |

| Cultural | Appropriateness of foods to local food culture | |

| Nutritional | Quality | Micronutrient density, Post-harvest nutrient loss |

| Safety | Contamination levels, Food handling practices |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Stakeholder Data Collection Protocol

Objective: To comprehensively assess nutritional quality dynamics across short food supply chains through mixed-methods approaches that capture both quantitative metrics and qualitative insights.

Materials:

- Digital data collection devices (tablets, smartphones)

- Standardized nutritional assessment tools (food composition tables, laboratory access for nutrient analysis)

- Qualitative interview guides

- Survey instruments for consumer acceptance testing

Procedure:

Stakeholder Mapping and Recruitment:

- Identify all actors in the SFSC using snowball sampling technique [28]

- Stratify sample to include producers, intermediaries (if any), and consumers

- Obtain informed consent following institutional ethical guidelines

Multi-Dimensional Data Collection:

- Conduct in-depth interviews with key informants using semi-structured protocols [28]

- Implement direct observation of food handling and storage practices

- Collect physical samples for nutritional composition analysis at critical points in the chain

- Administer consumer surveys to assess perceptions of nutritional quality and purchasing drivers (N=1000 recommended for statistical power) [28]

Nutritional Quality Assessment:

- Laboratory analysis of key micronutrients (iron, zinc, vitamin A, vitamin C)

- Assessment of phytochemical content where relevant

- Measurement of post-harvest nutrient degradation

- Documentation of food safety parameters

Data Integration:

- Employ triangulation methods to combine quantitative and qualitative findings

- Use mixed-methods approaches to connect supply-side and demand-side dynamics [28]

Digital Traceability Implementation Protocol

Objective: To implement technologically-enabled traceability systems that document nutritional quality parameters throughout the short food supply chain.

Materials:

- Blockchain-based tracking systems or alternative digital traceability platforms [30]

- IoT monitoring devices for temperature, humidity, and other relevant parameters

- Batch coding infrastructure

- Cloud-based databases for real-time visibility

Procedure:

System Design:

- Map all critical control points for nutritional quality maintenance

- Identify key data elements to capture (harvest date, storage conditions, processing methods)

- Establish data standards and interoperability protocols

Technology Implementation:

- Deploy unique product identification systems (serialization) [31]

- Implement aggregation systems to maintain parent-child relationships between packaging levels [31]

- Install environmental monitoring sensors at storage and transportation points

- Establish data capture procedures at each supply chain node

Data Management:

- Create centralized or distributed databases for traceability information

- Implement data validation procedures

- Establish access protocols for different stakeholders

- Develop data visualization tools for nutritional quality tracking

System Validation:

- Conduct mock recalls to test traceability effectiveness

- Verify data accuracy through random audits

- Assess system usability for all stakeholders

Analytical Framework Application

EVA Framework for Social Inclusiveness