Assessing Polyphenol Bioavailability: Methodologies, Challenges, and Advanced Applications for Research and Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the methodologies for assessing the bioavailability of polyphenols.

Assessing Polyphenol Bioavailability: Methodologies, Challenges, and Advanced Applications for Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the methodologies for assessing the bioavailability of polyphenols. It covers the foundational principles defining polyphenol bioavailability and the key biological barriers affecting it, from digestion to systemic distribution. The piece details core in vitro and in vivo assessment techniques, including simulated digestion models, UPLC-PDA-MS/MS analysis, and pharmacokinetic studies. It further addresses major troubleshooting areas such as low bioavailability and complex data interpretation, while exploring optimization strategies like nano-encapsulation and synergistic formulations. Finally, it examines validation frameworks, comparative analysis of different polyphenol classes, and the application of computational tools and databases for robust study design and data interpretation.

Defining Polyphenol Bioavailability and Its Foundational Principles

What is Bioavailability? Key Definitions for Xenobiotic Compounds

In pharmacology and toxicology, bioavailability is a fundamental pharmacokinetic parameter defined as the fraction (%) of an administered dose of a xenobiotic compound that reaches the systemic circulation unchanged [1] [2]. It quantifies the extent and rate at which the active moiety becomes available at the site of action [3]. This concept is critical for understanding the efficacy and safety of drugs, environmental contaminants, and bioactive food compounds.

The bioavailability of a substance administered intravenously is, by definition, 100% [1] [4]. However, for compounds administered via other routes (e.g., oral, dermal), bioavailability is typically lower due to physiological barriers that limit complete absorption, such as the intestinal epithelium, and processes like first-pass metabolism that chemically alter the compound before it reaches systemic circulation [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Bioavailability Terminology

| Term | Definition | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Bioavailability (F) | The fraction of a dose that reaches systemic circulation compared to an intravenous dose [1]. | Fundamental pharmacokinetics |

| Relative Bioavailability | The bioavailability of a test formulation compared to a reference standard [1]. | Formulation development, generic drugs |

| Bioequivalence | The absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent of absorption between two products [1] [5]. | Regulatory science |

| Bioaccessibility | The fraction released from the matrix into the gut lumen, making it available for absorption [6]. | Nutritional science, environmental toxicology |

| First-Pass Metabolism | Pre-systemic metabolism of a compound in the liver or gut wall after absorption [2]. | Drug design, dose prediction |

Quantifying Bioavailability

Core Pharmacokinetic Principles

Bioavailability (denoted as f or F) is most accurately determined by comparing the systemic exposure of a xenobiotic after extravascular administration to its exposure after intravenous administration [1]. This is achieved by measuring the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the plasma concentration-versus-time graph [4].

The standard formula for calculating absolute bioavailability after a single oral dose is:

Fabs = 100 · (AUCpo · Div) / (AUCiv · D_po)

Where:

- AUC_po is the AUC after oral administration

- AUC_iv is the AUC after intravenous administration

- Dpo and Div are the oral and intravenous doses, respectively [1]

This calculation assumes constant clearance and volume of distribution between the two administered doses [4].

The LADME Framework

The journey of a xenobiotic through the body, which ultimately determines its bioavailability, can be described by the LADME framework:

- Liberation: The release of the compound from its delivery matrix.

- Absorption: The passage into the systemic circulation.

- Distribution: The dispersion throughout bodily fluids and tissues.

- Metabolism: The chemical alteration of the compound.

- Elimination: The removal from the body [6].

The following diagram illustrates the key processes and barriers a xenobiotic like an oral drug must overcome to achieve systemic bioavailability.

Factors Influencing Bioavailability

A complex interplay of physiological, physicochemical, and environmental factors determines the bioavailability of a xenobiotic compound.

Physiological Factors:

- Gastrointestinal Tract Health: Conditions like achlorhydria or malabsorption syndromes can significantly reduce absorption [3].

- Hepatic and Renal Function: Impairment affects first-pass metabolism and elimination [1] [4].

- Blood Flow: Decreased splanchnic blood flow (e.g., in shock) can reduce the absorption rate [5].

- Gut Microbiota: Microbes can metabolize compounds before absorption, producing more or less active metabolites [6] [7].

- Age, Sex, and Genetic Phenotype: These can cause inter-individual variation in metabolic enzymes and transporters [1] [3].

Physicochemical and Formulation Factors:

- Drug Solubility and Permeability: The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) categorizes drugs based on these properties to predict absorption challenges [5].

- Chemical Instability: Hydrolysis by gastric acid or digestive enzymes can degrade a compound before absorption (e.g., penicillin) [3].

- Dosage Form Design: Immediate-release vs. modified-release (delayed, extended, sustained) formulations control the release rate [1].

- Food and Nutrient Interactions: Food can enhance, delay, or reduce absorption. For example, calcium-rich foods can chelate tetracycline, forming an insoluble complex [1] [3].

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study for Absolute Bioavailability

Objective: To determine the absolute oral bioavailability (F) of a new chemical entity.

Protocol:

- Study Design: A two-period, two-sequence crossover design is standard. Subjects are randomly assigned to receive either the intravenous formulation in period 1 and the oral formulation in period 2, or vice versa. A sufficient washout period (typically >5 half-lives) separates doses to prevent carryover [5].

- Dosing:

- Intravenous Dose: Administer a precisely measured IV dose as a slow bolus or short infusion. This serves as the reference.

- Oral Dose: Administer the test oral formulation with a standard volume of water (e.g., 240 mL). Dosing is typically performed after an overnight fast.

- Blood Sampling: Collect serial blood samples (e.g., pre-dose, 5, 15, 30, 45 min, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24 hours post-dose) into heparinized or EDTA-treated tubes. The schedule should adequately characterize the absorption, distribution, and elimination phases.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge blood samples to obtain plasma. Analyze plasma samples using a validated bioanalytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to determine the concentration of the unchanged xenobiotic.

- Data Analysis:

In Vitro Bioaccessibility Assay for Polyphenols

Objective: To simulate the gastrointestinal release of polyphenols from a food matrix, predicting their potential for absorption.

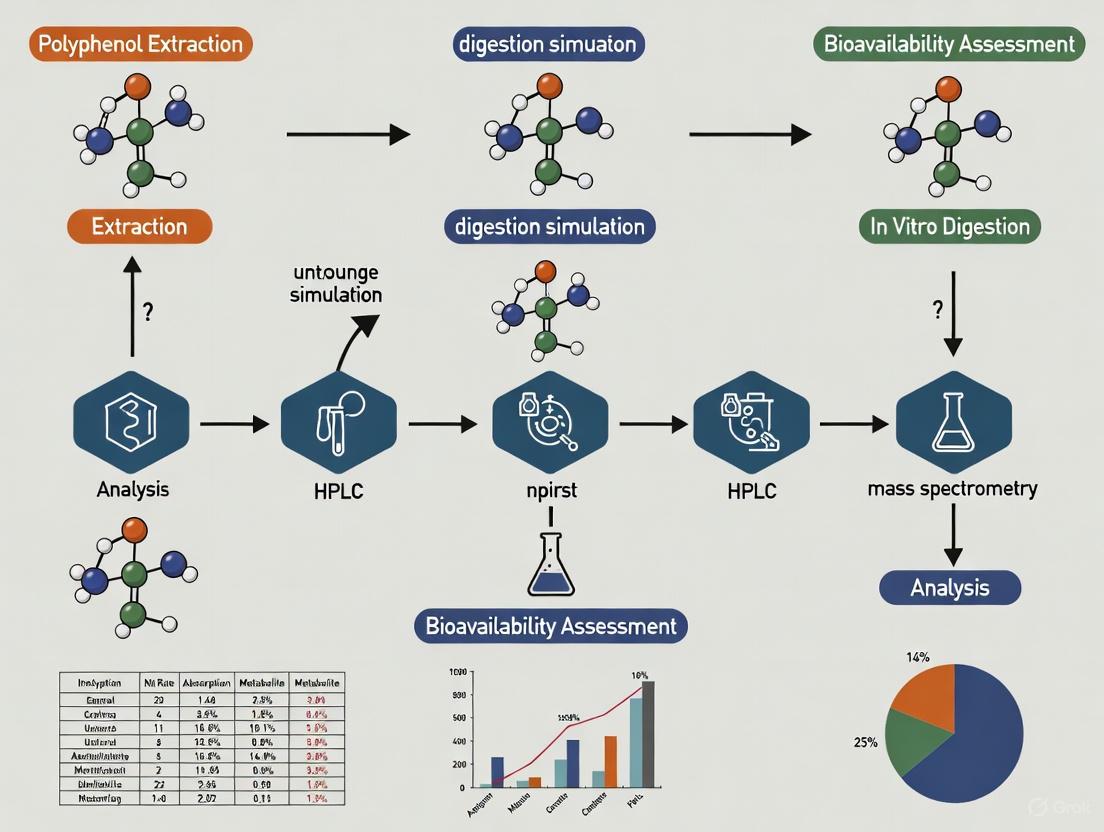

Protocol (Based on Infographic Digestion Models):

- Oral Phase: Mix the test material (e.g., fruit extract) with simulated salivary fluid (pH 6.8-7.0) containing α-amylase. Incubate for a short period (e.g., 2-5 minutes) with constant agitation.

- Gastric Phase: Adjust the pH of the oral bolus to 2.5-3.0 with HCl. Add pepsin solution and incubate for 1-2 hours at 37°C with shaking to simulate stomach motility.

- Intestinal Phase: Raise the pH to 6.5-7.0 using NaHCO₃ solution. Add pancreatin and bile salts to simulate the intestinal environment. Incubate for a further 2 hours at 37°C with shaking.

- Bioaccessible Fraction Separation: Centrifuge the final intestinal digest at high speed (e.g., 10,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). Carefully collect the supernatant, which represents the bioaccessible fraction—the compounds released from the matrix and potentially available for absorption [8] [6].

- Analysis: Quantify the total polyphenol content and specific phenolic compounds in the original test material and the bioaccessible fraction using spectrophotometric (e.g., Folin-Ciocalteu) and chromatographic (e.g., UPLC-MS/MS) methods [8]. Calculate the bioaccessibility percentage.

The workflow for this multi-stage experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Bioavailability Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids (Salivary, Gastric, Intestinal) | Provide a physiologically relevant medium for in vitro digestion models, containing appropriate ions and pH buffers [6]. |

| Digestive Enzymes (α-amylase, Pepsin, Pancreatin) | Catalyze the breakdown of complex food/dosage forms to simulate luminal digestion and compound liberation [6]. |

| Bile Salts (e.g., Sodium taurocholate) | Emulsify hydrophobic compounds, facilitating solubilization and absorption in in vitro intestinal models [6]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, forms a polarized monolayer with tight junctions and expresses relevant transporters. It is the gold standard in vitro model for predicting human intestinal permeability [5]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Drugs (e.g., ¹³C, ²H) | Co-administered with unlabeled drug to allow simultaneous assessment of IV and oral pharmacokinetics in a single subject, reducing variability [1] [5]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | The core analytical platform for the sensitive and specific quantification of drugs and their metabolites in complex biological matrices like plasma and digesta [8]. |

Application in Polyphenol Research

Bioavailability is a central, challenging question in polyphenol research. While these dietary compounds show promising bioactivity in vitro, their health effects in vivo are critically limited by low systemic bioavailability [6] [9].

Key Challenges and Insights:

- Low Absorption and Extensive Metabolism: Most polyphenols are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. Those that are absorbed undergo extensive phase II metabolism (conjugation), and the circulating conjugates often have altered activity [7] [9]. A significant proportion (90-95%) reaches the colon [7].

- Crucial Role of Gut Microbiota: Colonic gut microbiota play a pivotal role by converting non-absorbable parent polyphenols into smaller, more bioavailable phenolic metabolites (e.g., yielding urolithins from ellagitannins). These microbial metabolites are responsible for many systemic health effects [7].

- Matrix Effects: The food matrix can profoundly impact bioavailability. For example, purified polyphenolic extracts (IPE) have been shown to exhibit higher bioaccessibility and bioavailability indices compared to fruit matrix extracts (FME), where polyphenols are bound to fibers and other components [8].

- Inter-individual Variability: Differences in gut microbiota composition ("metabotypes") between individuals lead to significant variation in the metabolism and ultimate bioavailability of polyphenols, explaining inconsistent responses in clinical trials [7].

Bioavailability is a critical concept that bridges the administration of a xenobiotic and its physiological effect. For researchers investigating polyphenols, understanding and accurately assessing bioavailability is not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for explaining bioefficacy and developing effective nutraceuticals. The principles and methods outlined here—from classic pharmacokinetic studies to advanced in vitro simulations of digestion—provide a framework for robust bioavailability assessment. Future research will continue to focus on overcoming the inherent bioavailability challenges of polyphenols through technologies like nano-encapsulation and a deeper exploration of the individual's gut microbiome.

In dietary polyphenol research, a fundamental paradigm shift has moved the focus from the native compounds present in food to the vast array of metabolites and catabolites that appear in biological systems post-consumption. This collective set of derivatives, known as the polyphenol metabolome, ultimately mediates most biological effects observed in vivo [10] [11]. Understanding the complex journey of polyphenols from ingestion to systemic distribution is crucial for accurately interpreting their bioavailability and bioactivity.

The bioavailability of dietary polyphenols is generally low, with their chemical structure significantly limiting absorption and ensuring that circulating forms differ substantially from native food compounds [12]. Upon ingestion, polyphenols undergo extensive biotransformation via endogenous enzymes and gut microbiota, resulting in metabolites that exhibit different biological activities, distribution patterns, and pharmacokinetic profiles compared to their parent compounds [10] [11] [12]. This article explores the critical distinctions between native polyphenols and their metabolites, providing methodological frameworks for assessing the polyphenol metabolome within bioavailability research.

Diversity of Metabolites

The polyphenol metabolome encompasses all metabolites derived from phenolic food components, creating a complex network of chemically distinct compounds. Systematic analysis of human and animal intervention studies has identified 383 polyphenol metabolites in biofluids, which can be categorized as [10]:

- Direct metabolites: Including glucuronide and sulfate esters, glycosides, aglycones, and O-methyl ethers formed through host enzymatic processes

- Microbial catabolites: Particularly ring-cleavage metabolites formed by gut microbiota, mostly derived from hydroxycinnamates, flavanols, and flavonols

- Absorbed native compounds: Approximately one-third of metabolites are also known as food constituents absorbed without further metabolism

Chemical similarity mapping reveals distinct clusters within the metabolome, with glucuronides of all polyphenol classes forming the largest cluster, while anthocyanin mono- and diglycosides represent a chemically distinct group [10].

Metabolic Transformation Pathways

The metabolic fate of polyphenols depends on their chemical structure, food matrix, and individual differences in host metabolism and gut microbiota composition. Figure 1 illustrates the primary metabolic pathways that transform native polyphenols into their bioactive metabolites.

Figure 1. Metabolic pathways transforming dietary polyphenols into bioactive metabolites. The diagram tracks the journey from native compounds through gastrointestinal processing, microbial metabolism, and host enzymatic modification to tissue distribution.

Quantitative Analysis of the Polyphenol Metabolome

Pharmacokinetic Parameters

Systematic analysis of pharmacokinetic data from intervention studies provides insight into the absorption and distribution characteristics of polyphenol metabolites. The data presented in Table 1 summarizes key pharmacokinetic parameters for polyphenol metabolites in humans, highlighting differences between food and supplement sources [10].

Table 1. Pharmacokinetic parameters of polyphenol metabolites in human plasma

| Parameter | Food Sources | Dietary Supplements |

|---|---|---|

| Median Cmax (μM) | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| Median Tmax (h) | 2.18 | 2.18 |

| Identified Metabolites | 383 | 383 |

| Metabolites without hydrolysis | 301 | 301 |

| Microbiota-derived metabolites | Prevalent (hydroxycinnamates, flavanols, flavonols) | Prevalent (hydroxycinnamates, flavanols, flavonols) |

Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability Across Matrices

The food matrix significantly influences the bioaccessibility and ultimate bioavailability of polyphenols. Comparative studies between purified extracts and whole food matrices reveal substantial differences in polyphenol stability and absorption. Table 2 summarizes key findings from comparative assessments of polyphenol bioaccessibility [8] [13].

Table 2. Bioaccessibility comparison between fruit matrix and purified extracts

| Parameter | Fruit Matrix Extract (FME) | Purified Polyphenol Extract (IPE) |

|---|---|---|

| Total polyphenol content | Higher initial content (e.g., 38.9 mg/g in cv. Nero) | 2.3 times fewer polyphenols initially |

| Gastric stage | 49-98% loss throughout digestion | 20-126% increase in content |

| Intestinal stage | Continued degradation | ~60% degradation post-absorption |

| Bioaccessibility index | Lower | 3–11 times higher across polyphenol classes |

| Antioxidant bioavailability | Reduced | Higher indices for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities |

Methodological Approaches for Metabolome Analysis

Analytical Workflows for Metabolite Identification

Comprehensive characterization of the polyphenol metabolome requires sophisticated analytical approaches. Figure 2 outlines a standardized workflow for extracting, identifying, and quantifying polyphenol metabolites from biological samples, incorporating both targeted and untargeted methodologies [10] [14].

Figure 2. Experimental workflow for comprehensive polyphenol metabolome analysis. The protocol encompasses sample preparation, chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric detection, and data analysis pathways.

In Vitro Digestion Models

Understanding polyphenol bioaccessibility requires physiologically relevant digestion models. The INFOGEST protocol, particularly in its semi-dynamic implementation, provides a more physiologically accurate representation of gastric emptying and nutrient absorption kinetics compared to static models [13]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Semi-dynamic vs. static models: The semi-dynamic INFOGEST model more closely aligns the kinetics of nutrient digestion with structural changes in the food matrix during gastric digestion, significantly influencing polyphenol bioaccessibility [13]

- Gastric emptying rates: Calorie-driven gastric emptying (e.g., 2 kcal/min) more accurately reflects physiological conditions compared to fixed-time emptying [13]

- Mechanical processing: Magnetic stirring provides more physiological conditions for oxygenation and intragastric chyme homogenization compared to paddle stirring, which can lead to greater browning and polyphenol degradation [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3. Essential research reagents and materials for polyphenol metabolome analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-MS/MS System | High-resolution separation and detection | Enables untargeted metabolomics; essential for identifying unknown metabolites [14] |

| Authentic Standards | Metabolite identification and quantification | Critical for confirming identities via retention time and fragmentation matching [14] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample clean-up and concentration | Improves detection sensitivity; removes interfering compounds [10] |

| β-Glucosidase/Lactase-Phlorizin Hydrolase | Enzymatic deconjugation | Simulates intestinal hydrolysis of glycosylated polyphenols [12] |

| INFOGEST Digestion Model | Simulated gastrointestinal digestion | Standardized protocol for assessing bioaccessibility; available in static and semi-dynamic formats [13] |

| Hydroxyapatite Beads | Binding studies | Models polyphenol-bone interactions; relevant for tissue distribution studies [14] |

Tissue Distribution and Physiological Sequestration

Emerging evidence indicates that polyphenols and their metabolites can accumulate in specific tissues, where they may exert localized biological effects. Metabolomics approaches have identified multiple diet-derived polyphenolic compounds in physiological bone, suggesting a general sequestration mechanism similar to that previously observed with alizarin and tetracycline [14].

Key findings include:

- Bone sequestration: Multiple polyphenolic compounds from an acorn-based diet were identified in pig bone extracts but not in surrounding tissues [14]

- Hydroxyapatite binding: In vitro studies confirm that a range of polyphenolic compounds bind to hydroxyapatite, suggesting a mechanism for bone incorporation [14]

- Inter-individual variation: The presence of specific metabolites (e.g., urolithins) in bone varies between individuals, potentially reflecting differences in gut microbiota composition [14]

The comprehensive characterization of the polyphenol metabolome represents a critical advancement in nutritional science and drug development. The evidence clearly demonstrates that metabolites and catabolites, rather than native compounds, are the primary mediators of polyphenol bioactivity in vivo. Understanding the complex metabolic transformations, tissue distribution patterns, and factors influencing bioavailability is essential for designing effective polyphenol-based interventions and accurately interpreting their physiological effects.

The methodological approaches outlined here provide researchers with robust frameworks for investigating the polyphenol metabolome, from standardized digestion protocols to advanced analytical techniques. As research in this field progresses, focusing on the bioactivity of specific metabolites rather than parent compounds will accelerate the development of evidence-based recommendations for polyphenol consumption and therapeutic applications.

The health benefits of dietary polyphenols are critically dependent on their ability to overcome significant biological barriers to reach systemic circulation and target tissues. Their efficacy is not solely determined by intake levels but by their bioavailability—the fraction of ingested compound that reaches systemic circulation and specific sites of action [15]. Polyphenols face three major sequential barriers: (1) the gastrointestinal tract, where chemical stability and solubility are challenged; (2) enterocyte metabolism, where extensive biotransformation occurs; and (3) systemic distribution, where further metabolism and rapid excretion limit tissue exposure. Understanding these barriers is fundamental to developing effective polyphenol-based therapeutics and nutraceuticals.

The Gastrointestinal Tract Barrier

Stability and Solubility Challenges

The journey of polyphenols begins in the GI tract, where they face significant stability challenges across varying pH environments and enzymatic activities. Only a small fraction (5-10%) of ingested dietary polyphenols is directly absorbed in the small intestine, while the vast majority (90-95%) proceeds to the colon where they undergo extensive microbial transformation [16] [17]. The food matrix significantly influences this initial bioavailability phase; for instance, purified polyphenol extracts (IPE) demonstrate superior stability compared to fruit matrix extracts (FME), with IPE showing a 20-126% increase in polyphenol content during gastric and intestinal stages, while FME exhibits 49-98% loss throughout digestion [8].

Table 1: Gastrointestinal Stability of Polyphenol Formulations

| Extract Type | Gastric Stage Change | Intestinal Stage Change | Post-Absorption Degradation | Bioavailability Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Polyphenol Extract (IPE) | +20 to +126% | Increased content | ~60% degradation | 3-11 times higher |

| Fruit Matrix Extract (FME) | Significant loss | 49-98% loss | Continuous degradation | Baseline |

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Simulated Digestion Model

Purpose: To evaluate polyphenol stability and bioaccessibility throughout the gastrointestinal passage.

Materials:

- Simulated gastric fluid (SGF): 0.32% pepsin in 0.08M HCl, pH 2.0

- Simulated intestinal fluid (SIF): 1% pancreatin in 0.05M KH₂PO₄, pH 7.4

- Dialysis membranes (MWCO 12-14 kDa) for absorptive phase

- Polyphenol extract samples (IPE and FME compared in parallel)

- UPLC-PDA-MS/MS system for quantification

Procedure:

- Gastric Phase (GD): Incubate 5 mL of polyphenol sample with 5 mL SGF at 37°C for 60 minutes with continuous agitation.

- Intestinal Phase (GID): Adjust pH to 7.4 with 1M NaOH, add 5 mL SIF, incubate at 37°C for 120 minutes.

- Absorptive Phase (AD): Transfer mixture to dialysis membrane suspended in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), incubate at 37°C for 120 minutes.

- Sample Collection: Collect aliquots at each phase termination. Stabilize with antioxidant preservatives (ascorbic acid/EDTA) and flash-freeze at -20°C until analysis.

- Analysis: Quantify polyphenol content via UPLC-PDA-MS/MS, identifying specific metabolites and degradation products [8].

Enterocyte Metabolism and Absorption Barrier

Absorption Mechanisms and First-Pass Metabolism

Upon reaching the small intestine, polyphenols undergo enzymatic hydrolysis by lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH) and cytosolic β-glucosidases, releasing aglycone forms capable of crossing the gut barrier [17]. Molecular size significantly impacts absorption efficiency; proanthocyanidins with a polymerization degree exceeding 4 (DP > 4) cannot be absorbed due to macromolecular size and intestinal barrier limitations [16]. Absorbed polyphenols undergo extensive phase II metabolism in the gut mucosa and liver, resulting in conjugation with glucuronide, sulphate, and methyl groups. These conjugated derivatives facilitate excretion and limit potential toxicity, with non-conjugated polyphenols being virtually absent in plasma [18].

Diagram Title: Enterocyte Metabolism and Absorption Pathways

Experimental Protocol: In Situ Intestinal Perfusion Model

Purpose: To quantify intestinal absorption and metabolism kinetics of polyphenols.

Materials:

- Rat intestinal perfusion apparatus with temperature control

- Polyphenol test solution in Krebs-Ringer buffer (pH 6.5-7.4)

- Peristaltic pump with calibrated flow rates

- HPLC-MS/MS system with electrochemical detection

- Surgical equipment for intestinal loop preparation

Procedure:

- Surgical Preparation: Anesthetize rat and expose small intestine. Cannulate intestinal segment (typically jejunum, 10-15 cm length) while maintaining vascular and nervous supply.

- Perfusion Setup: Flush intestinal segment with warm saline, connect to perfusion system with polyphenol test solution (50-100 μM) at flow rate 0.2-0.3 mL/min.

- Sample Collection: Collect perfusate at timed intervals (10-20 min) over 120 minutes. Simultaneously collect blood from mesenteric vein and portal vein.

- Metabolite Analysis: Stabilize samples with antioxidant cocktail, analyze via HPLC-MS/MS for parent compounds and metabolites.

- Kinetic Calculations: Determine absorption rate (Ka), permeability (Papp), and metabolic conversion rates using established mathematical models [19].

Table 2: Absorption Characteristics of Major Polyphenol Classes

| Polyphenol Class | Primary Absorption Site | Absorption Mechanism | Approximate Absorption Rate | Major Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonols (Quercetin) | Small intestine/Colon | Hydrolysis + Passive diffusion | 5-10% | Quercetin glucuronides, sulphates |

| Flavan-3-ols (Catechin) | Small intestine | Passive diffusion | 20-40% | Methylated/glucuronidated conjugates |

| Anthocyanins | Stomach/Small intestine | Active transport? | <1% | Protocatechuic acid, phenolic acids |

| Phenolic Acids (Caffeic) | Small intestine | Passive diffusion | 30-50% | Glucuronidated/sulphated derivatives |

| Proanthocyanidins (DP>4) | Colon | Microbial catabolism | Minimal as parent compound | Valerolactones, phenolic acids |

Systemic Distribution and Microbial Biotransformation Barrier

Microbial Metabolism and Tissue Distribution

The significant proportion of polyphenols escaping small intestinal absorption reaches the colon, where resident microbiota perform extensive biotransformation, converting complex polyphenols into simpler phenolic metabolites that are often more bioavailable than the parent compounds [20] [17]. These microbial metabolites can enter systemic circulation, leading to distant effects throughout the body. The gut microbiota thus acts as a crucial "secondary organ" for polyphenol metabolism, with individual variations in microbial composition significantly influencing polyphenol bioavailability and efficacy [21] [22]. This microbial metabolism represents both a barrier to parent compound distribution and an opportunity for generating active metabolites.

Diagram Title: Systemic Distribution and Microbial Biotransformation

Experimental Protocol: Pharmacokinetic Assessment in Human Subjects

Purpose: To characterize complete pharmacokinetic profiles of polyphenols and their metabolites in humans.

Materials:

- Standardized polyphenol source (e.g., unfiltered apple juice, purified extract)

- LC-MS/MS system with high sensitivity

- Blood collection tubes with anticoagulant and preservatives

- Urine collection containers with antioxidant preservatives

- Pharmacokinetic analysis software

Procedure:

- Study Design: Conduct randomized, controlled crossover study with washout period. Participants follow polyphenol-free diet 48 hours prior to and during study.

- Dosing and Sampling: Administer standardized dose after overnight fast. Collect blood samples pre-dose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 24 hours post-dose. Collect total urine over 0-4, 4-8, 8-12, and 12-24 hour intervals.

- Sample Processing: Immediately process blood to plasma, add antioxidant preservatives (ascorbic acid/EDTA), flash-freeze at -80°C. Stabilize urine samples with sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.8) containing EDTA and ascorbic acid.

- Analytical Method: Extract polyphenols and metabolites using ethyl acetate. Analyze via UPLC-MS/MS with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for parent compounds and known metabolites.

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Calculate Cmax, Tmax, AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, t1/2, and clearance using non-compartmental analysis. Identify inter-individual variation subgroups (fast/slow metabolizers) [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Polyphenol Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | In vitro digestion models | Standardized composition of enzymes, electrolytes, pH | Bioaccessibility assessment, stability testing |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Intestinal absorption model | Human colon adenocarcinoma, differentiates into enterocyte-like cells | Permeability studies, transport mechanisms |

| UPLC-PDA-MS/MS System | Polyphenol identification and quantification | High resolution, sensitivity, structural elucidation capability | Metabolic profiling, pharmacokinetic studies |

| Lactase-Phlorizin Hydrolase (LPH) | Enzymatic hydrolysis of polyphenol glycosides | Brush border membrane enzyme | Studies of initial absorption step mechanism |

| Phase II Enzyme Cofactors (UDPGA, PAPS, SAM) | In vitro metabolism studies | Co-substrates for glucuronidation, sulfation, methylation | Metabolite formation studies, enzyme kinetics |

| Dialysis Membranes (MWCO 12-14 kDa) | Simulated absorptive phase | Size-selective permeability | Bioavailability prediction from in vitro models |

| Antioxidant Preservative Cocktails | Sample stabilization during processing | Ascorbic acid, EDTA, sodium phosphate | Prevention of polyphenol oxidation ex vivo |

| Gut Microbiota Media | In vitro fermentation models | Anaerobic conditions, nutrient sources | Microbial metabolism studies, metabolite identification |

The multifaceted biological barriers facing dietary polyphenols—from gastrointestinal instability and enterocyte metabolism to extensive systemic distribution challenges—represent critical hurdles that must be overcome to realize their full therapeutic potential. The experimental approaches detailed herein provide robust methodologies for quantifying and characterizing these barriers, enabling researchers to develop strategies to enhance polyphenol bioavailability. Understanding the complex interplay between polyphenol structure, food matrix effects, host metabolism, and gut microbial biotransformation is essential for advancing the application of polyphenols in preventive and therapeutic interventions. Future research should focus on personalized approaches that account for individual variations in gut microbiota and metabolic phenotypes to optimize polyphenol efficacy across diverse populations.

Bioavailability is defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient or compound that is absorbed, metabolized, and reaches systemic circulation for delivery to target tissues and organs to exert a biological effect [24]. For dietary polyphenols—a large class of over 8,000 plant-based bioactive compounds—bioavailability is a critical determinant of their purported health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective effects [25] [26]. The absorption and utilization of polyphenols in the human body are not straightforward; they are influenced by a complex interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors [27]. Understanding these factors is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to design effective polyphenol-based interventions, functional foods, and nutraceuticals. This application note details the three primary categories of factors governing polyphenol bioavailability: the chemical structure of the polyphenol itself, the food matrix in which it is delivered, and the physiology of the host individual. The note further provides standardized experimental protocols for assessing bioavailability and explores advanced modeling and formulation technologies that are shaping future research and development.

Critical Factor 1: Chemical Structure

The chemical structure of a polyphenol is the most fundamental factor controlling its metabolic fate and absorption. Key structural features directly influence solubility, stability in the gastrointestinal tract, and interaction with cellular uptake mechanisms.

Key Structural Determinants of Bioavailability

Table 1: Impact of Polyphenol Chemical Structure on Bioavailability

| Structural Feature | Impact on Bioavailability | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Glycosylation (Sugar Conjugation) | Significantly affects absorption kinetics. The type and number of sugar moieties influence hydrolysis by digestive enzymes and gut microbial β-glucosidases [27]. | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside (rutin) is poorly absorbed compared to its aglycone quercetin [28]. Anthocyanins exist primarily as glycosides, impacting their stability and uptake [24]. |

| Molecular Size & Polymerization | Larger, polymeric structures are generally less absorbable. Monomers are absorbed in the small intestine, while polymers require colonic microbial catabolism [29]. | Monomeric flavan-3-ols (e.g., catechins) are absorbed directly. Oligomeric and polymeric proanthocyanidins are poorly absorbed and rely on microbial metabolism [25]. |

| Hydroxylation & Methoxylation | The number and position of hydroxyl (-OH) groups influence antioxidant capacity and phase II metabolism (e.g., glucuronidation, sulfation). Methoxylation can increase lipophilicity and passive diffusion [30]. | More hydroxyl groups can lead to more extensive conjugation, potentially reducing bioavailability. Methoxylated flavones may have higher absorption [31]. |

| Esterification | Requires hydrolysis by esterases for absorption. This can be a rate-limiting step [28]. | Chlorogenic acid (an ester of caffeic and quinic acids) is largely cleaved by gut microbiota before absorption of its components [28]. |

Structural Classification of Polyphenols

Polyphenols are classified based on their chemical structure into several major classes, each with distinct bioavailability profiles [25] [28]. The fundamental division is between flavonoids and non-flavonoids.

- Flavonoids: Characterized by a C6-C3-C6 skeleton (two aromatic rings linked by a three-carbon bridge). Subclasses include flavonols (e.g., quercetin), flavanols (e.g., catechins, proanthocyanidins), flavones, flavanones (e.g., hesperidin), anthocyanins, and isoflavones [25] [26]. Their specific hydroxylation and glycosylation patterns vary widely, leading to significant differences in absorption.

- Non-Flavonoids: Include phenolic acids (e.g., hydroxycinnamic acids like chlorogenic acid and hydroxybenzoic acids like gallic acid), stilbenes (e.g., resveratrol), and lignans [25] [31]. Phenolic acids are often found in esterified forms, while stilbenes like resveratrol are noted for their very low oral bioavailability due to rapid metabolism [32].

The following diagram illustrates the major polyphenol classes and the key structural features that influence their absorption and metabolism.

Critical Factor 2: Food Matrix

The food matrix—the complex assembly of nutrients and other components in which a polyphenol is embedded—can profoundly enhance or inhibit its bioaccessibility (release from the food) and subsequent bioavailability [26]. The effects can be physical, chemical, or biochemical.

Matrix Component Interactions

Table 2: Food Matrix Effects on Polyphenol Bioavailability

| Matrix Component | Nature of Interaction | Consequence for Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber | Binds polyphenols non-covalently or entraps them physically [31] [26]. | Can reduce bioaccessibility by limiting release during digestion. May delay absorption and deliver more polyphenols to the colon for microbial fermentation [29]. |

| Proteins | Forms reversible (non-covalent) or irreversible (covalent quinone-mediated) complexes [31]. | Can reduce bioaccessibility and inhibit digestive enzymes, potentially lowering bioavailability. Covalent bonds are particularly stable and can significantly reduce absorption [31]. |

| Lipids | Improves solubility and protection of lipophilic polyphenols. Stimulates bile secretion. | Can enhance the bioavailability of lipophilic polyphenols (e.g., some curcuminoids, resveratrol) by facilitating micellization and absorption [26]. |

| Other Polyphenols | May act synergistically or antagonistically during absorption and metabolism. | Complex interactions; some combinations may inhibit specific transporters, while others may enhance stability or reduce the rate of metabolism [30]. |

Impact of Food Processing

Processing techniques alter the food matrix and can significantly modify polyphenol content and bioavailability. The effects are highly variable and depend on the processing parameters (type, intensity, duration) and the specific polyphenol [26].

- Positive Effects: Thermal processing (e.g., blanching, pasteurization) can break down cell walls and disrupt the food matrix, increasing the extractability and bioaccessibility of bound polyphenols. For instance, thermal treatment of tomatoes increases the bioaccessible lycopene content, and similar principles can apply to certain polyphenols [26].

- Negative Effects: Excessive heating, especially under oxygen, can lead to the thermal degradation and oxidative polymerization of sensitive polyphenols. Furthermore, processes like peeling and milling can remove polyphenol-rich parts of the plant (e.g., fruit skins, aleurone layer in cereals) [26].

- Non-Thermal Techniques: Emerging techniques like ultrasound-assisted extraction are considered environmentally sustainable and can efficiently release polyphenols from plant matrices with reduced solvent consumption and energy requirements, potentially creating ingredients with higher bioactivity [25].

Critical Factor 3: Host Physiology

Inter-individual variation in human physiology is a major source of heterogeneity in polyphenol bioavailability and bioefficacy. Key physiological factors include gastrointestinal conditions, gut microbiota composition, and genetic polymorphisms affecting metabolism.

Gastrointestinal Environment & Gut Microbiota

The digestive tract is the primary site for polyphenol metabolism. Gastric pH, intestinal permeability, and transit time can all influence stability and absorption. The most significant and variable physiological factor is the gut microbiota [29]. The colonic microbiota acts as a "metabolic organ" that catabolizes polyphenols not absorbed in the small intestine, converting them into absorbable, low-molecular-weight metabolites (e.g., phenolic acids, urolithins from ellagitannins) [25] [29]. The composition and metabolic activity of an individual's microbiota are highly unique, influenced by diet, genetics, health status, and medication use (especially antibiotics), leading to substantial inter-individual differences in the metabolic fate of complex polyphenols [24] [29].

Genetic Polymorphisms

Genetic variations in genes encoding Phase I and Phase II metabolic enzymes (e.g., UGTs, SULTs, COMT) and membrane transporters (e.g., efflux pumps like P-glycoprotein) can significantly alter an individual's capacity to metabolize and absorb specific polyphenols [27]. These polymorphisms can affect the rate of conjugation (glucuronidation, sulfation, methylation) and the efficiency of cellular uptake and efflux, ultimately influencing systemic exposure to polyphenols and their metabolites [32].

The following workflow summarizes the journey of dietary polyphenols through the human body and highlights the critical points where host physiology dictates their fate.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Bioavailability

Robust assessment of polyphenol bioavailability requires well-designed in vitro and in vivo studies. The following protocols provide standardized methodologies for key experiments.

Protocol 1: In Vitro Bioaccessibility and Permeability Assessment

This protocol simulates human digestion and intestinal absorption to screen polyphenol bioaccessibility rapidly.

1. Objective: To determine the bioaccessibility (release from the food matrix during simulated digestion) and apparent permeability (potential for intestinal absorption) of polyphenols from a test sample.

2. Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 4 for details.

- Equipment: Physiological chamber (e.g., shaking water bath), pH meter, centrifuge, Caco-2 cell line (ATCC HTB-37), Transwell plates, HPLC-MS/MS system.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. Follow the INFOGEST standardized static in vitro digestion model [24].

- Oral Phase: Mix test sample with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) and α-amylase for 2 min at pH 7.0.

- Gastric Phase: Adjust to pH 3.0, add simulated gastric fluid (SGF) and pepsin, incubate for 2 h at 37°C with agitation.

- Intestinal Phase: Adjust to pH 7.0, add simulated intestinal fluid (SIF), pancreatin, and bile salts, incubate for 2 h at 37°C with agitation.

- Step 2: Centrifugation. Centrifuge the final digest (e.g., 10,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The supernatant represents the bioaccessible fraction. Analyze polyphenol content via HPLC-MS/MS.

- Step 3: Caco-2 Cell Permeability Assay.

- Culture Caco-2 cells on Transwell inserts for 21 days to form differentiated monolayers.

- Apply the bioaccessible fraction (from Step 2) to the apical (AP) compartment.

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂. Sample from the basolateral (BL) compartment at scheduled timepoints (e.g., 30, 60, 120 min).

- Analyze samples for transported polyphenols and metabolites via HPLC-MS/MS.

- Calculate the Apparent Permeability (Papp) coefficient.

4. Data Analysis:

- Bioaccessibility (%) = (Polyphenol content in supernatant / Total polyphenol content in original sample) × 100.

- Papp (cm/s) = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane surface area, and C₀ is the initial concentration in the donor compartment.

Protocol 2: Human Pharmacokinetic Study for Bioavailability

This clinical protocol is the gold standard for quantifying polyphenol bioavailability and inter-individual variation in humans.

1. Objective: To determine the pharmacokinetic profile, including maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (Tmax), and area under the curve (AUC), of polyphenols and their metabolites following ingestion.

2. Materials:

- Test Product: Characterized polyphenol-rich food, extract, or supplement with known compound profile.

- Participants: Healthy adults (n determined by power analysis), following informed consent. Exclusion criteria typically include smoking, chronic disease, and use of antibiotics or supplements.

- Equipment: Blood collection tubes (EDTA), urine collection containers, -80°C freezer, HPLC-MS/MS system.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Study Design. A randomized, controlled, crossover design is preferred. Implement a washout period of at least 1 week between interventions. Participants follow a low-polyphenol diet for 48 hours prior to each test day.

- Step 2: Sample Administration and Collection.

- After an overnight fast, collect baseline (t=0) blood and urine samples.

- Administer a single, standardized dose of the test product.

- Collect blood samples at frequent, predetermined intervals (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 h post-consumption). Centrifuge blood immediately to isolate plasma.

- Collect total urine over 0-24h or in specific fractions (e.g., 0-4h, 4-8h, 8-24h).

- Step 3: Sample Analysis. Store all biofluids at -80°C until analysis. Quantify concentrations of parent polyphenols and known metabolites (glucuronides, sulfates, methylated forms, microbial metabolites) in plasma and urine using validated HPLC-MS/MS methods.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, Tmax, AUC0–t, AUC0–∞) from plasma concentration-time data using non-compartmental analysis (e.g., Phoenix WinNonlin) [32].

- Calculate cumulative urinary excretion as a percentage of the ingested dose for specific compounds where possible.

Table 3: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters from Human Studies

| Parameter | Definition | Interpretation in Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Cmax | Maximum observed plasma concentration. | Indicates the peak absorption level and potential for acute bioactivity. |

| Tmax | Time to reach Cmax. | Reflects the rate of absorption and release from the food matrix. |

| AUC | Area Under the plasma Concentration-time curve. | Represents the total systemic exposure to the compound over time; the primary measure of the extent of bioavailability. |

| Urinary Recovery | Cumulative amount excreted in urine over 24h. | Provides a quantitative estimate of absorption for some polyphenols that are excreted unchanged. |

Advanced Research Tools: PBPK Modeling and Encapsulation

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK modeling is a powerful "middle-out" approach that integrates in vitro drug parameters (e.g., logP, pKa, permeability) with organism-specific physiological parameters (e.g., organ volumes, blood flow rates) to mechanistically simulate and predict the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of compounds in the human body [32].

- Application: PBPK models are particularly valuable for polyphenol research due to the complex mixture and variability of these compounds. They can predict human PK from preclinical data, simulate drug-diet interactions, perform cross-species extrapolation, and model complex metabolic processes involving gut microbiota [32].

- Workflow: The model construction involves defining anatomical compartments, integrating system-specific and drug-specific data, and calibrating/validating the model with in vivo PK data. Software platforms like Simcyp, GastroPlus, and PK-Sim are commonly used [32].

Bioavailability Enhancement via Encapsulation

To overcome the inherent low bioavailability of many polyphenols, advanced delivery systems are being developed. Encapsulation involves entrapping polyphenols within a protective wall material (e.g., polysaccharides, proteins, lipids) to shield them from degradation and control their release [25] [30].

- Evidence from Human Studies: Clinical evidence indicates that encapsulation is most effective for specific, single polyphenols rather than complex mixtures. For instance, micellized curcumin and encapsulated hesperidin and fisetin have shown significantly improved bioavailability in human trials. In contrast, encapsulation did not consistently improve the bioavailability of polyphenol blends from sources like bilberry anthocyanins or cocoa [24].

- Materials: Polysaccharides like pectin, which can be sustainably extracted from food industry by-products (e.g., citrus peel, apple pomace), are promising biocompatible and biodegradable wall materials for forming nanoparticles that protect polyphenols through the gastrointestinal tract [30].

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that spontaneously differentiates into enterocyte-like cells. Forms a polarized monolayer for studying intestinal permeability and transport mechanisms. | In vitro model for predicting intestinal absorption of polyphenols (Protocol 1) [27]. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids (SGF, SIF) | Standardized solutions containing electrolytes and enzymes (pepsin, pancreatin) to mimic the chemical and enzymatic conditions of the human GI tract. | Used in in vitro digestion models to assess bioaccessibility (Protocol 1) [24]. |

| Bile Salts (e.g., Sodium Taurocholate) | Surfactants that facilitate the emulsification of lipids and the solubilization of lipophilic compounds into mixed micelles, a prerequisite for absorption. | A critical component of simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) to assess micellarization of lipophilic polyphenols [24]. |

| Standardized Polyphenol Extracts | Well-characterized extracts with known and consistent composition (e.g., green tea extract, grape seed extract). Essential for reproducible dosing in interventional studies. | Used as the test material in both in vitro and in vivo bioavailability studies (Protocol 2) [33]. |

| β-Glucuronidase/Sulfatase Enzymes | Enzymes used to hydrolyze phase II metabolites (glucuronides, sulfates) in biofluid samples prior to analysis. | Allows for the quantification of total (aglycone + conjugated) levels of a polyphenol in plasma and urine [27]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Polyphenols | Polyphenols where atoms are replaced by less common stable isotopes (e.g., ¹³C, ²H). Serve as internal tracers to precisely track pharmacokinetics and metabolite formation. | Used in advanced human studies to distinguish newly absorbed compounds from background metabolites and to elucidate specific metabolic pathways [29]. |

Core Methodologies for In Vitro and In Vivo Bioavailability Assessment

In the study of polyphenol bioavailability, in vitro simulated digestion models are indispensable tools for predicting the release, transformation, and absorption of these bioactive compounds from the food matrix. Bioavailability encompasses the processes of digestion, absorption by intestinal cells, transport into circulation, and delivery to the site of action [34]. In vitro models provide a reproducible, ethical, and cost-effective alternative to in vivo studies, allowing for controlled mechanistic investigations into the digestibility and bioaccessibility of polyphenols [35]. The following sections detail the primary models, experimental protocols, and key reagents used to simulate the gastric, intestinal, and colonic phases of digestion within polyphenol research.

Classification and Comparison of In Vitro Digestion Models

In vitro digestion models range from simple static systems to complex dynamic setups that more closely mimic human physiology. The choice of model significantly influences the observed bioaccessibility of polyphenols [35] [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Static vs. Dynamic In Vitro Digestion Models

| Feature | Static Models | Dynamic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Single-compartment; fixed conditions throughout digestion [35]. | Multi-compartmental; conditions change dynamically to mimic physiology [35]. |

| Key Characteristics | Fixed pH, enzyme concentrations, and digestion times [36]. | Simulates gastric emptying, fluid secretion, and peristaltic movements [13] [37]. |

| Predictability of Digestibility | Controlled assessment of nutrient breakdown [35]. | More realistically mimics real-life dynamic digestion [35]. |

| Advantages | Simple, highly reproducible, cost-effective, suitable for high-throughput screening [35] [34]. | Provides a more physiologically relevant simulation of the GI environment [13]. |

| Disadvantages | Does not account for the dynamic and physical processes of digestion [35]. | Technically complex, expensive, and requires specialized equipment [35]. |

| Impact on Polyphenol Bioaccessibility | The semi-dynamic setup can show greater extraction of some polyphenols (e.g., hydroxybenzoic acids) from a food matrix compared to static models [13]. | Minimal differences are observed between models for matrix-devoid polyphenol extracts, suggesting static models may be sufficient for purified compounds [13]. |

The Harmonized INFOGEST Static Protocol: A Core Methodology

The harmonized INFOGEST static in vitro digestion protocol is a widely adopted standardized method that simulates the oral, gastric, and intestinal phases of digestion [36] [34]. Its standardization of pH, enzyme activities, and digestion times allows for reproducibility and comparability across laboratories, making it a cornerstone in food digestibility research, including polyphenol studies [35] [36].

Table 2: Key Parameters of the Harmonized INFOGEST Static Protocol

| Digestion Phase | Duration | pH | Key Enzymes | Electrolyte Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 2 min | 7.0 | α-Amylase (e.g., 51.0 U/mL [37]) | KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, MgCl₂, (NH₄)₂CO₃, CaCl₂ [37] |

| Gastric | 2 hours | 3.0 (initial), then lowered to 1.3 [37] | Pepsin (e.g., 714 U/mL [37]) | Same as oral, with pH adjustment using HCl |

| Intestinal | 2 hours | 7.0 | Pancreatin (with trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, amylase), Bile salts | Same as gastric, with pH adjustment using NaHCO₃ |

The experimental workflow for a standardized static digestion assay, as applied to a polyphenol-rich sample, is outlined below.

Advanced Dynamic Digestion Models

Dynamic models offer a more physiologically realistic simulation by incorporating physical forces and changing conditions. Examples include the TNO gastro-intestinal model (TIM), the dynamic gastric model (DGM), and the human gastric digestion simulator (GDS) [37]. These systems can simulate gastric peristalsis, which directly influences the physical breakdown of the food matrix and the subsequent release of polyphenols [37] [34]. For instance, the GDS uses quantitative mechanical motion to simulate antral peristalsis, allowing for direct observation of processes like particle fracture, disintegration, and fluid penetration during gastric digestion [37]. One study on apple fractions found that a semi-dynamic model led to greater extraction of certain polyphenols from whole apple and pomace compared to the static model, highlighting the matrix-dependent relevance of dynamic physical processes [13].

Modeling Intestinal Absorption for Bioavailability Assessment

Following digestion, assessing absorption is critical for determining polyphenol bioavailability. Several in vitro models are used to mimic the intestinal epithelium, each with varying complexity and physiological relevance [34].

Table 3: In Vitro Models for Studying Intestinal Absorption

| Model | Description | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cell-based Transport Models | Use artificial membranes to measure passive diffusion. | Simple and low-cost [34]. | Lack biological selectivity and active transport mechanisms of living cells [34]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Monolayers | Human colon adenocarcinoma cells cultured on membrane inserts that differentiate into enterocyte-like cells. | Incorporates brush border enzymes and various active/passive transport mechanisms; most commonly used method [34]. | Lacks the cellular diversity and complexity of the native intestinal epithelium [34]. |

| Organoids & Ex Vivo Models | 3D structures derived from stem cells that contain multiple intestinal cell types, or actual intestinal tissue. | Better recapitulates the cellular complexity and organization of the intestine [34]. | Technically challenging, variable, and less amenable to high-throughput screening [34]. |

| Gut-on-a-Chip (Microfluidic) | Microfluidic devices containing living human intestinal cells under fluid flow and mechanical strain. | Can co-culture microbes and human cells; mimics peristalsis-like motions and shear stress; highest accuracy [34]. | Highly specialized equipment and expertise required; not yet standardized for food studies [34]. |

The relationship between digestion, absorption models, and the final assessment of bioavailability is a sequential process, as illustrated in the following workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of in vitro digestion and absorption experiments relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for In Vitro Digestion and Absorption Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Salivary Fluid (SSF) | Provides the ionic environment of saliva; used in the oral phase with α-amylase to initiate starch digestion [37]. | Composition: KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, MgCl₂, (NH₄)₂CO₃, CaCl₂ [37]. |

| Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF) | Provides the acidic ionic environment of the stomach; used in the gastric phase with pepsin for protein digestion [37]. | pH adjusted to 1.3 with HCl; contains pepsin (e.g., 714 U/mL from porcine gastric mucosa [37]). |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF) | Provides the neutral ionic environment of the small intestine; used with pancreatin and bile salts for further nutrient digestion [36]. | pH adjusted to 7.0 with NaHCO₃; contains pancreatin and bile salts [36]. |

| Pepsin | Gastric protease responsible for the hydrolysis of proteins in the stomach phase [35] [36]. | Critical enzyme; its activity determination was a major source of variability prior to INFOGEST harmonization [36]. |

| Pancreatin & Bile Salts | Pancreatin is a mixture of intestinal enzymes (proteases, lipase, amylase); bile salts emulsify lipids. Both are essential for the intestinal phase [36] [34]. | Used in the intestinal phase to simulate the secretion from the pancreas and gallbladder [36]. |

| Caco-2 Cells | A human cell line that, upon differentiation, forms a polarized monolayer with brush border enzymes, mimicking intestinal enterocytes for absorption studies [34]. | The most often used method to measure absorption and simulate passive/active transport mechanisms [34]. |

| Transwell Inserts | Permeable supports used to culture Caco-2 cells, allowing for the separation of apical (luminal) and basolateral (serosal) compartments to model transport [34]. | Enables the measurement of nutrient transport across the cell monolayer to determine bioavailability [34]. |

The study of polyphenol bioavailability is crucial for understanding their role in promoting human health and preventing disease. Assessing bioavailability requires precise analytical methods to identify and quantify parent polyphenols and their metabolite derivatives in complex biological matrices post-consumption. Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Photodiode Array and Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-PDA-MS/MS) and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) have emerged as cornerstone techniques for these analyses. This protocol details the application of these integrated systems for comprehensive metabolite profiling in bioavailability studies, enabling researchers to decipher the complex biotransformation pathways of dietary polyphenols.

Technical Principles and Instrumentation

Integrated Detection Capabilities

The power of UPLC-PDA-MS/MS lies in the synergistic combination of multiple detection modalities, each providing a different layer of information about the analytes.

Photodiode Array (PDA) Detection: Functions as a universal detector for chromophores, recording UV-Vis spectra (typically 200-600 nm) for each eluting compound. Specific polyphenol classes exhibit characteristic absorption patterns; for instance, flavones and flavonols show Band I (320-385 nm) and Band II (250-285 nm) absorption, while anthocyanins are detected in the 480-550 nm range [38]. The PDA provides preliminary compound classification and can be used for quantification when standards are available.

Mass Spectrometry (MS) Detection: Serves as a highly specific and sensitive detector for structural elucidation and confirmation. Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is the most common interface, efficiently generating ions in both positive (suitable for anthocyanins) and negative (suitable for most other polyphenols) modes [38]. The first mass analyzer (Q1) separates ions by their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), providing molecular weight information.

Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS): Provides fragmentation patterns through collision-induced dissociation (CID), which are essential for determining structural details and differentiating isomers. High-resolution mass analyzers such as Quadrupole-Time of Flight (QTOF) [38] or Orbitrap [39] [40] provide accurate mass measurements for elemental composition determination, significantly enhancing confidence in metabolite identification.

Comparison of Quantitative Detection Methods

The choice between detection methods involves trade-offs between specificity, sensitivity, and practicality, as highlighted by comparative studies in complex plant matrices.

Table 1: Comparison of UHPLC-UV and UHPLC-MS/MS for Polyphenol Quantification

| Parameter | UHPLC-UV/PDA Detection | UHPLC-MS/MS (SRM Mode) |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Moderate; co-elution can cause overestimation [41]. | High; specific precursor→product ion transitions [41]. |

| Sensitivity | Good for major compounds. | Excellent; capable of detecting trace metabolites [41]. |

| Identification Power | Limited; based on retention time and UV spectrum. | High; provides molecular mass and fragmentation data. |

| Matrix Effects | Susceptible to interference from co-eluting compounds [41]. | Can be significant; requires careful method validation [41]. |

| Best Use Case | Quantification of major, well-separated analytes with available standards. | Targeted quantification in complex matrices, identification of unknown metabolites. |

Experimental Protocols for Metabolite Identification

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for reliable results in metabolite profiling, especially from biological fluids.

Biological Sample Collection and Storage: Collect plasma or serum using appropriate anticoagulants (e.g., EDTA-K2). Immediately after collection, centrifuge samples at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Aliquot the supernatant into pre-cooled tubes, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C until analysis [42].

Metabolite Extraction: Thaw stored samples on ice. For a 50 μL plasma sample, add 300 μL of ice-cold extraction solvent (Acetonitrile:Methanol, 1:4, v/v) containing suitable internal standards. Vortex the mixture vigorously for 3 minutes, then centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer 200 μL of the supernatant, incubate at -20°C for 30 minutes, and centrifuge again at 12,000 rpm for 3 minutes (4°C). Collect the final supernatant for LC-MS analysis [42]. This protein precipitation method effectively extracts a wide range of polar and semi-polar metabolites.

UPLC-PDA-MS/MS Analysis Protocol

This protocol provides a generalized method for analyzing polyphenols and their metabolites, adaptable based on specific instrumentation and research needs.

Liquid Chromatography Conditions:

- Column: Reverse-phase C18 (e.g., ACQUITY HSS T3, 1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm) [39].

- Mobile Phase: A) Water with 0.1% Formic Acid; B) Acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic Acid [39] [40].

- Gradient Elution: Initiate at 5% B, increase linearly to 40% B over 10 minutes, then to 99% B over 4-5 minutes. Hold at 99% B for 1-2 minutes for column washing, then re-equilibrate at initial conditions [39] [40].

- Flow Rate, Temperature & Injection Volume: 0.3-0.4 mL/min, 40°C, and 2-4 μL, respectively [39].

PDA Detection: Acquire spectra across the 200-600 nm range. Monitor specific wavelengths for different polyphenol classes: 280 nm (flavan-3-ols, phenolic acids), 320 nm (hydroxycinnamic acids), 360 nm (flavonols), and 520 nm (anthocyanins) [43] [41].

Mass Spectrometry Conditions:

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), alternating between positive and negative modes, or acquiring separately.

- Source Parameters: Sheath Gas: 40-50 psi; Auxiliary Gas: 15-50 psi; Ion Source Temperature: 300°C; Ion Spray Voltage: 3500 V (positive), 3000 V (negative) [42] [39].

- Data Acquisition: Use data-dependent acquisition (DDA). First, perform a full MS scan (e.g., m/z 50-1500) at high resolution (e.g., 70,000). Then, automatically select the most intense ions for fragmentation (MS/MS) at a collision energy of 20-40 eV [39].

Data Processing and Metabolite Identification Protocol

- Metabolite Annotation: Process raw data using software (e.g., MS-Dial, XCMS) for peak picking, alignment, and deconvolution. Annotate metabolites by querying experimental data against spectral libraries (e.g., GNPS, MassBank, HMDB, METLIN) [39] [44]. Key parameters for confident annotation include:

- Accurate mass: Mass error < 5-10 ppm.

- MS/MS spectrum: Cosine similarity score > 0.7-0.8 against reference spectra.

- Isotopic pattern: Matching theoretical distribution.

- Validation with Standards: Where possible, confirm identities by comparing retention times and fragmentation patterns with authentic analytical standards [45] [40].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process from sample to identification:

Applications in Polyphenol Bioavailability Research

Targeted Analysis of Polyphenol Metabolites

In bioavailability studies, targeted LC-MS/MS methods using Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) or Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) provide the highest sensitivity for quantifying specific phase I and phase II metabolites. These methods focus on predefined metabolite transitions but rely on prior knowledge of likely biotransformation products.

Untargeted Metabolite Profiling

Untargeted UPLC-QTOF/MS or UPLC-Orbitrap-MS profiling captures a comprehensive snapshot of the metabolome, ideal for discovering novel polyphenol metabolites [42] [40]. This hypothesis-generating approach requires sophisticated data analysis but is invaluable for elucidating complete biotransformation pathways. Advanced fragmentation techniques like Electron-Activated Dissociation (EAD) can provide complementary fragmentation pathways to CID, aiding in the identification of challenging labile metabolites [46].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful metabolite identification requires carefully selected reagents, standards, and columns. The following toolkit lists critical components for UPLC-PDA-MS/MS analysis in polyphenol bioavailability studies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolite Identification

| Category/Item | Specific Example | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | ACQUITY HSS T3 C18 (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm) [39] | Standard reverse-phase column for separating a wide range of polyphenols. |

| Zwitterionic (ZIC)-HILIC [47] | For retaining highly polar metabolites that poorly retain on C18. | |

| MS Calibration & QC | Caffeine-13C3, L-Leucine-D7, Benzoic acid-D5 [42] | Internal standards added to extraction solvent to monitor instrument stability and performance. |

| Polyphenol Standards | (-)-Epicatechin, (+)-Catechin, Chlorogenic acid, Procyanidin B1/B2, Quercetin glycosides [43] [41] | Authentic standards for method validation, quantification, and confirmation of retention time/fragmentation. |

| Extraction Solvents | Acetonitrile:Methanol (1:4, v/v) [42] | Effective for protein precipitation and extraction of a broad spectrum of polar metabolites from plasma/serum. |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Formic Acid (0.1%) [39] [40] | Acidifies mobile phase to improve protonation and chromatographic peak shape for acidic analytes. |

UPLC-PDA-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS represent the gold standard for metabolite identification in polyphenol bioavailability research. The integrated protocol presented here—encompassing robust sample preparation, optimized chromatographic separation, synergistic PDA and MS detection, and rigorous data processing—provides a comprehensive framework for identifying and quantifying polyphenols and their biotransformation products. As these technologies continue to evolve, particularly with improvements in chromatographic materials, ionization efficiency, and data analysis algorithms, our ability to fully elucidate the complex metabolic fate of dietary polyphenols and its relation to human health will be profoundly enhanced.

Within the framework of research on methods to assess the bioavailability of polyphenols, the pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters Cmax, Tmax, and AUC serve as the fundamental triad for quantifying systemic exposure and absorption profile. These parameters provide critical, quantitative insights into the journey of polyphenols from consumption to their appearance in the systemic circulation, a process complicated by extensive metabolism in the gut and liver [29]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding and accurate determination of these parameters are indispensable for evaluating the efficacy of different polyphenol formulations, guiding dose optimization, and substantiating scientific claims about bioactive availability.

The following sections detail the theoretical foundation, experimental protocols, and data analysis techniques essential for the reliable assessment of Cmax, Tmax, and AUC in both human and animal studies.

Theoretical Foundations of Core PK Parameters

The table below defines the key PK parameters and their toxicological and efficacy implications.

Table 1: Core Pharmacokinetic Parameters and Their Significance

| Parameter | Definition | Pharmacokinetic Insight | Toxicological / Efficacy Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax | The maximum concentration of a drug observed in the plasma after administration [48]. | Indicates the rate and extent of absorption; a higher Cmax often suggests faster or better absorption [49]. | Peak-related toxicity potential; must be high enough for efficacy but below the toxic threshold [48]. |

| Tmax | The time taken to reach the peak drug concentration (Cmax) after administration [48]. | Reflects the rate of absorption; a short Tmax suggests rapid absorption [48]. | Informs the expected onset of biological action and dosing schedule design. |

| AUC (Area Under the Curve) | The definite integral of the drug concentration in blood plasma over time, representing total drug exposure [50]. | A critical measure of overall bioavailability (the fraction of administered dose that reaches systemic circulation) [50] [51]. | The primary metric for assessing extent of exposure, bioequivalence, and relating exposure to therapeutic effect [52] [48]. |

These parameters are most commonly derived from a concentration-time curve, which is generated by measuring plasma concentrations of the compound at several time points after administration.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these parameters on a typical plasma concentration-time curve and their connection to the fundamental processes of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME).

Experimental Protocols for PK Parameter Assessment

Study Design Considerations

The foundation of reliable PK data is a robust study design. Key considerations include:

- Crossover vs. Parallel Designs: For bioequivalence (BE) studies comparing polyphenol formulations, a crossover design is often preferred. In this design, each subject receives both the test and reference formulations in separate periods, with a sufficient washout period in between to eliminate carryover effects. This minimizes inter-subject variability and reduces the required sample size [49]. Parallel designs, where different groups of subjects receive different formulations, are used when a compound has a very long half-life.

- Subject Selection and Control: Recruit healthy volunteers or the target patient population. Screening must exclude individuals with recent use of supplements or medications that could interact, and those with restrictive diets that might alter polyphenol absorption [49]. Standardized meals, particularly regarding fat content, are crucial as the food matrix significantly impacts the bioavailability of lipophilic polyphenols like curcumin [49].

- Dosing and Sample Collection: Administer a defined dose of the polyphenol product. For absolute bioavailability assessment, an intravenous (IV) dose is the gold standard, but this is often not feasible for dietary polyphenols. Blood sampling schedules must be tailored to the expected PK profile, with dense sampling around the predicted Tmax and a sufficient duration to characterize the elimination phase for accurate AUC estimation [48].

Sample Collection, Processing, and Bioanalysis

This protocol outlines the critical steps from blood draw to quantitative data generation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for PK Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | The gold-standard technology for the highly sensitive and specific quantification of drugs, polyphenols, and their metabolites in biological samples [48]. |

| Validated Bioanalytical Method | A method that has been proven to be specific, accurate, precise, and robust for the target analyte in a specific matrix (e.g., plasma), essential for generating reliable concentration data [48]. |

| K2EDTA or Heparin Tubes | Vacutainer tubes containing anticoagulants for collecting whole blood, which is then processed to obtain plasma for analysis. |

| Stable-Labeled Internal Standards | Isotopically labeled versions of the analyte used in mass spectrometry to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency, improving accuracy. |

| Cryogenic Vials | For the secure long-term storage of plasma samples at -80°C to preserve analyte stability. |

Workflow Overview:

- Administer the polyphenol product to the study subject [48].

- Collect blood samples (e.g., via venipuncture) into anticoagulant-containing tubes at pre-defined time points (e.g., pre-dose, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours post-dose) [48].

- Process blood samples by centrifugation to separate plasma from blood cells.

- Store plasma samples at -80°C or below until analysis to ensure compound stability [48].

- Analyze using a validated bioanalytical method, typically LC-MS/MS. The process involves:

- Sample Preparation: Protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, or solid-phase extraction to remove interfering matrix components and concentrate the analytes.

- Chromatographic Separation: Using Liquid Chromatography (LC) to separate the target polyphenol and its metabolites from other compounds in the sample.

- Detection & Quantification: Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) to identify and measure the analytes based on their mass-to-charge ratio, generating the concentration data for each time point [48].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the entire journey from study design to the generation of the concentration-time data.

Data Analysis and Calculation Methods

Non-Compartmental Analysis (NCA) and Parameter Calculation

With the concentration-time data generated, Non-Compartmental Analysis (NCA) is the standard approach for calculating PK parameters [48].

- Cmax and Tmax: These are determined by direct observation of the concentration-time data. Cmax is the highest measured concentration value, and Tmax is the time point at which this highest concentration occurs [48].

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): This is the most critical calculation for exposure. The trapezoidal rule is the conventional method for its estimation [50] [52]. The total AUC from time zero to the last measurable time point (AUC0-t) is calculated by summing the areas of successive trapezoids between each time point.

The formula for the trapezoidal rule is: AUC = Σ [0.5 × (C₁ + C₂) × (t₂ - t₁)] Where C₁ and C₂ are concentrations at consecutive time points t₁ and t₂ [52].