Beyond Antioxidants: Unveiling the Multifaceted Mechanisms of Polyphenols in Functional Foods for Health and Disease Prevention

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex mechanisms of action of dietary polyphenols in functional foods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Beyond Antioxidants: Unveiling the Multifaceted Mechanisms of Polyphenols in Functional Foods for Health and Disease Prevention

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex mechanisms of action of dietary polyphenols in functional foods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Moving beyond the traditional antioxidant paradigm, we explore foundational molecular pathways, including interactions with gut microbiota, modulation of inflammatory signaling (NF-κB, MAPK), and enzyme inhibition (e.g., xanthine oxidase). The review delves into methodological advances in extraction and stabilization, such as encapsulation, to enhance bioaccessibility. It further addresses critical challenges in bioavailability and compound stability, evaluating evidence from preclinical, clinical, and in silico studies. The synthesis of this information aims to bridge the gap between mechanistic understanding and the rational development of effective, evidence-based functional foods and therapeutic candidates.

Deconstructing the Molecular Machinery: Core Mechanisms of Polyphenol Bioactivity

Polyphenols represent one of the most abundant and widely distributed classes of bioactive compounds in the plant kingdom, serving as crucial secondary metabolites with diverse physiological functions. As the most common antioxidants in the human diet, these compounds have garnered significant scientific interest for their potential role in preventing and managing chronic diseases through multiple biological mechanisms [1] [2]. In the context of functional foods research, understanding the classification, dietary sources, and structural characteristics of polyphenols is fundamental to elucidating their mechanisms of action and developing targeted nutritional interventions [3] [4].

These compounds exhibit tremendous structural diversity, with over 8,000 identified polyphenolic structures possessing varying biological activities [5] [6]. The bioavailability, bioaccessibility, and ultimate physiological effects of dietary polyphenols are intrinsically linked to their chemical structures and the food matrices in which they are incorporated [3] [2]. This complex relationship between structure, source, and function presents both challenges and opportunities for their application in functional food development and disease prevention strategies aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Classification and Structural Characteristics of Polyphenols

Polyphenols are systematically classified based on the number and arrangement of their phenolic rings and the structural elements that connect these rings. The major classes include flavonoids, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and lignans, each with distinct chemical characteristics that influence their biological activity and functional properties in food systems [5] [6] [7].

Flavonoids

Flavonoids constitute the largest and most extensively studied class of polyphenols, characterized by a fundamental C6-C3-C6 skeleton consisting of two aromatic rings (A and B) connected by a three-carbon heterocyclic ring (C) [6] [7] [8]. This basic structure undergoes various modifications, including hydroxylation, methylation, glycosylation, and methoxylation, resulting in several important subclasses:

- Flavonols: Feature a 3-hydroxyflavone backbone (e.g., quercetin, kaempferol) and are particularly abundant in onions, kale, and berries [5] [2].

- Flavones: Characterized by a 2,3-unsaturated carbonyl group (e.g., apigenin, luteolin) and found in parsley, celery, and herbs [2].

- Flavanones: Possess a saturated heterocyclic C ring (e.g., naringenin, hesperetin) predominantly present in citrus fruits [2].

- Flavanols: Also known as flavan-3-ols, include monomeric catechins and polymeric proanthocyanidins (e.g., epicatechin, epigallocatechin gallate) abundant in tea, cocoa, and apples [5] [2].

- Anthocyanidins: Provide pigmentation to flowers and fruits (e.g., cyanidin, delphinidin) and are found in berries, grapes, and red cabbage [5].

- Isoflavones: Feature a B-ring connected at the C3 position (e.g., genistein, daidzein) primarily present in legumes, especially soy [2].

Non-Flavonoid Polyphenols

The major non-flavonoid polyphenol classes include:

- Phenolic Acids: Divided into hydroxybenzoic acids (C6-C1 structure) and hydroxycinnamic acids (C6-C3 structure), with caffeic acid and ferulic acid being prominent examples found in coffee, whole grains, and berries [5] [8].

- Stilbenes: Characterized by a C6-C2-C6 structure consisting of two benzene rings connected by an ethylene bridge, with resveratrol from grapes and red wine being the most extensively researched [6] [8].

- Lignans: Composed of two phenylpropane units (C6-C3)2 linked by a β-β′ bond, with secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol as primary examples found in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and whole grains [6] [2].

- Tannins: High-molecular-weight compounds divided into hydrolyzable tannins (gallotannins, ellagitannins) and condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins) [6].

Table 1: Classification and Structural Characteristics of Major Polyphenol Classes

| Polyphenol Class | Basic Structure | Subclasses | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | C6-C3-C6 | Flavonols, Flavones, Flavanones, Flavanols, Anthocyanidins, Isoflavones | Two aromatic rings connected by a heterocyclic ring; variations in hydroxylation, conjugation, and degree of saturation |

| Phenolic Acids | C6-C1 or C6-C3 | Hydroxybenzoic acids, Hydroxycinnamic acids | Single phenolic ring with one carboxylic acid group and one or more hydroxyl groups |

| Stilbenes | C6-C2-C6 | Resveratrol, Pterostilbene | Two aromatic rings connected by an ethylene bridge |

| Lignans | (C6-C3)2 | Secoisolariciresinol, Matairesinol | Two phenylpropane units linked by a β-β′ bond |

Dietary polyphenols are ubiquitously distributed in plant-based foods, with significant variation in concentration and composition across different food groups. The quantitative content of specific polyphenol subclasses varies considerably between dietary sources, influencing their potential contribution to health benefits and their application in functional food development [2].

Berries represent particularly rich sources of diverse polyphenols, with black elderberry containing high concentrations of anthocyanidins (1,316.65 mg/100 g) and black chokeberry providing substantial amounts of anthocyanidins (878.12 mg/100 g) and proanthocyanidins [2]. Citrus fruits are notable for their flavanone content, primarily hesperidin and naringenin, while apples contribute significantly to dietary flavonol intake, particularly quercetin derivatives [5] [2].

Vegetables show considerable diversity in their polyphenol profiles. Onions, particularly red onions, are rich sources of flavonols (128.51 mg/100 g raw), while spinach provides significant amounts of flavonols (119.27 mg/100 g raw) and phenolic acids [2]. Celery seeds contain exceptionally high concentrations of flavones (2,094 mg/100 g), and dried herbs such as Mexican oregano are rich sources of multiple polyphenol classes, including flavones (733.77 mg/100 g) and flavanones (1,049.67 mg/100 g) [2].

Tea, especially green tea, is particularly rich in flavanols (71.17 mg/100 g infusion), primarily catechins such as epigallocatechin gallate [2]. Coffee serves as a major dietary source of phenolic acids, with chlorogenic acid comprising 6-12% of green Robusta coffee beans, potentially contributing over 1 g of chlorogenic acid daily for regular consumers [2]. Red wine provides stilbenes, notably resveratrol, along with anthocyanidins and flavonols [6] [2].

Cocoa powder contains high concentrations of flavanols (511.62 mg/100 g), with dark chocolate also contributing significantly to flavanol intake (212.36 mg/100 g) [2]. Whole grains, particularly cereals, provide phenolic acids, with ferulic acid comprising up to 98% of the total phenolic acids in cereals, primarily located in the aleurone layer and pericarp [5]. Legumes, especially soy-based products, are rich sources of isoflavones, with soy flour containing 466.99 mg/100 g of these phytoestrogenic compounds [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Content of Major Polyphenol Classes in Dietary Sources

| Dietary Source | Predominant Polyphenol Class | Specific Compounds | Representative Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black elderberry | Anthocyanidins | Cyanidin derivatives | 1,316.65 mg/100 g [2] |

| Cocoa powder | Flavanols | Catechins, Procyanidins | 511.62 mg/100 g [2] |

| Soy flour | Isoflavones | Genistein, Daidzein | 466.99 mg/100 g [2] |

| Green tea | Flavanols | Epigallocatechin gallate, Epicatechin | 71.17 mg/100 g infusion [2] |

| Red onion | Flavonols | Quercetin glycosides | 128.51 mg/100 g [2] |

| Coffee beans | Phenolic acids | Chlorogenic acids | 6-12% of dry weight [5] |

| Flaxseeds | Lignans | Secoisolariciresinol | 0.3-3.0 mg/g [6] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Action in Functional Foods

The health-promoting effects of dietary polyphenols are mediated through multiple interconnected biological mechanisms that contribute to their therapeutic potential in chronic disease prevention and management. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for optimizing their application in functional food development.

Antioxidant Activities

Polyphenols exert potent antioxidant effects through two primary mechanisms: direct free radical scavenging and induction of endogenous antioxidant defense systems. The antioxidant capacity is largely determined by the number and arrangement of hydroxyl groups on the phenolic rings, which facilitate hydrogen atom transfer and single electron transfer processes that neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6] [8]. Certain polyphenols can also activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway, leading to increased expression of antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, providing an indirect antioxidant effect [8].

Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms

Polyphenols modulate inflammatory responses primarily through inhibition of key transcription factors and enzymatic pathways. Many flavonoids and phenolic acids suppress NF-κB activation, reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [1] [6]. Additionally, polyphenols inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) enzymes, decreasing the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes that mediate inflammatory processes [5] [8]. These anti-inflammatory activities contribute to the protective effects against chronic inflammatory conditions, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Enzyme Inhibition and Modulation

Polyphenols interact with numerous enzymatic systems, influencing critical physiological processes. They inhibit digestive enzymes including α-amylase and α-glucosidase, modulating postprandial glycemic responses, which is particularly relevant for diabetes management [2]. Certain flavonoids act as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, potentially benefiting cognitive function in neurodegenerative conditions [5]. Polyphenols also modulate phase I and phase II biotransformation enzymes, influencing xenobiotic metabolism and detoxification processes [5].

Gut Microbiota Interactions

The reciprocal interaction between dietary polyphenols and gut microbiota represents a significant mechanism underlying their health benefits. Polyphenols shape gut microbial composition, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria while inhibiting pathogenic species [6]. Gut microbiota extensively metabolize polyphenols into bioavailable metabolites with enhanced biological activity, such as equol from daidzein and urolithins from ellagitannins [6]. These microbial metabolites often exhibit superior bioavailability and bioactivity compared to their parent compounds, contributing to systemic health effects.

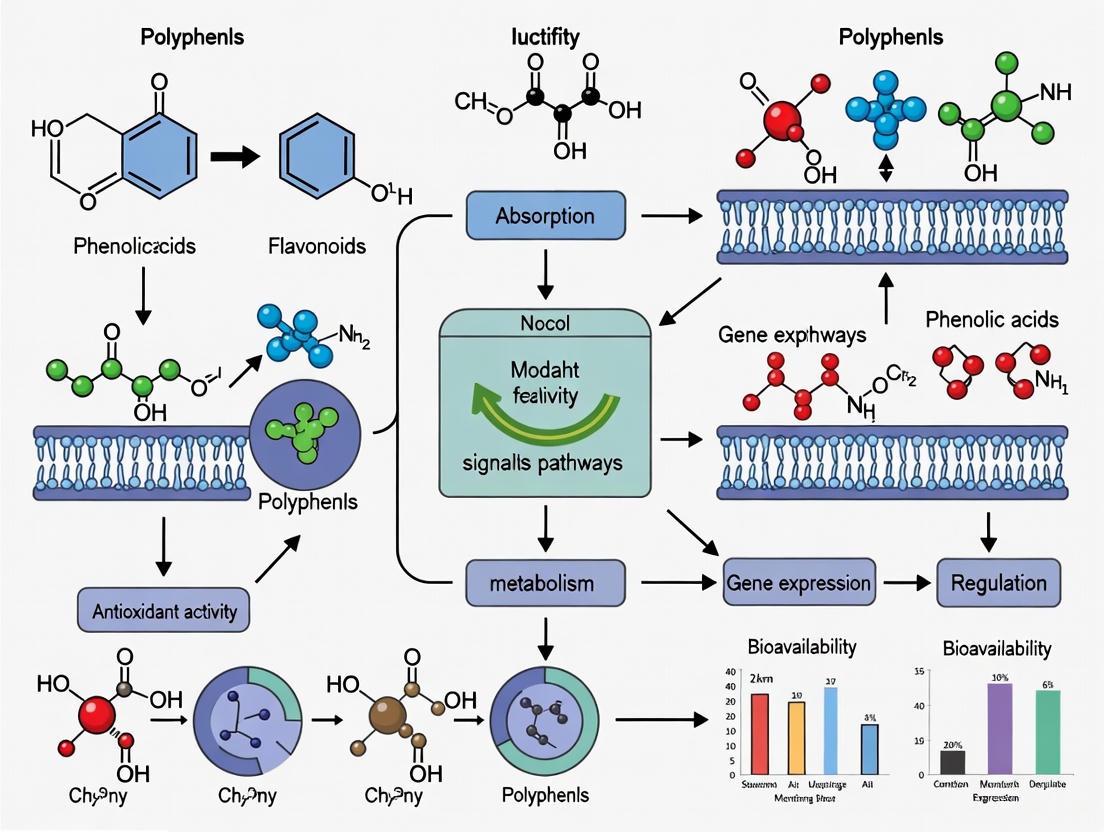

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanisms of Polyphenol Bioactivity. This diagram illustrates the primary molecular mechanisms through which dietary polyphenols exert their biological effects, including antioxidant activities, anti-inflammatory actions, enzyme modulation, gut microbiota interactions, and signaling pathway regulation.

Methodological Approaches in Polyphenol Research

Extraction and Characterization Methods

The complex nature of polyphenols necessitates sophisticated extraction and characterization methodologies to accurately identify and quantify these compounds in food matrices and biological samples.

Extraction Techniques:

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Utilizes acoustic cavitation (frequencies >20 kHz) to disrupt plant cell walls, enhancing solvent penetration and reducing extraction time and solvent consumption [6]. Optimal parameters include controlled temperature (30-60°C), solvent selection (methanol, ethanol, acetone/water mixtures), and extraction duration (10-60 minutes) [6].

- Enzyme-Assisted Extraction: Employ specific enzymes (cellulase, pectinase) to break down plant cell walls and release bound polyphenols, particularly effective for phenolic acids [6].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction: Uses supercritical CO₂, often with modifiers like ethanol, for efficient extraction of non-polar to moderately polar polyphenols with minimal degradation [6].

Characterization Methods:

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Coupled with diode array detection (DAD) or mass spectrometry (MS) for separation, identification, and quantification of individual polyphenols [6].

- Mass Spectrometry: Provides structural information through fragmentation patterns, enabling identification of unknown polyphenols and their metabolites [6].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Offers detailed structural information, particularly for elucidating novel polyphenol structures and stereochemistry [6].

Bioavailability Assessment Protocols

Evaluating the bioavailability of polyphenols is crucial for understanding their potential health benefits and optimizing delivery systems.

In Vitro Digestion Models:

- Simulate gastrointestinal conditions using sequential incubation with simulated gastric fluid (pH 2.0, pepsin, 37°C, 1-2 hours) followed by simulated intestinal fluid (pH 7.5, pancreatin, bile salts, 37°C, 2-4 hours) [5] [6].

- Measure bioaccessibility (percentage of compound released from food matrix) and transformation during digestion.

Cell Culture Models:

- Utilize Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers to assess intestinal absorption and transport mechanisms [5].

- Measure transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and transport efficiency across the intestinal barrier.

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Studies:

- Administer standardized polyphenol extracts to animal models or human subjects and collect serial blood, urine, and tissue samples [5] [6].

- Quantify parent compounds and metabolites using LC-MS/MS to determine pharmacokinetic parameters (Cₘₐₓ, Tₘₐₓ, AUC, half-life).

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Polyphenol Analysis

| Research Reagent | Application | Function | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Total phenolic content assay | Oxidizing agent for phenolic compounds | Measures reducing capacity; results expressed as gallic acid equivalents |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Antioxidant activity assay | Stable free radical for scavenging capacity | Measures hydrogen donation ability; absorbance decrease at 517 nm |

| ABTS⁺ (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Antioxidant activity assay | Pre-formed radical cation | Measures electron transfer ability; absorbance decrease at 734 nm |

| Simulated Gastric/Intestinal Fluids | Bioaccessibility studies | Mimic physiological digestion conditions | Contain pepsin (gastric) or pancreatin/bile salts (intestinal) |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Intestinal absorption studies | Model human intestinal epithelium | Measure transport across intestinal barrier; assess bioavailability |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Identification and quantification | Separation and detection of polyphenols | High sensitivity and specificity; enables metabolite profiling |

Advanced Delivery Systems for Enhanced Bioavailability

The clinical application of polyphenols is often limited by challenges such as poor aqueous solubility, chemical instability, and extensive first-pass metabolism, resulting in low oral bioavailability [6] [9]. Advanced delivery systems have been developed to address these limitations and enhance the efficacy of polyphenols in functional food applications.

Nanoencapsulation Technologies

Nanoencapsulation techniques significantly improve the stability, solubility, and targeted delivery of polyphenols:

- Liposomal Systems: Phospholipid-based vesicles that encapsulate polyphenols within their lipid bilayers, protecting them from degradation and enhancing absorption through biomimetic fusion with cellular membranes [6]. Liposomal formulations have demonstrated improved bioavailability for epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), resveratrol, and curcumin in preclinical models [6].

- Polymeric Nanoparticles: Biodegradable polymers such as PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) and chitosan that provide controlled release profiles and protection from enzymatic degradation [9]. These systems can be engineered for specific targeting through surface modification with ligands that recognize receptors on target cells [9].

- Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs): Composed of physiological lipids that remain solid at room and body temperature, offering improved stability compared to liposomes while maintaining high encapsulation efficiency for lipophilic polyphenols [9].

Protein-Polyphenol Complexation

The strategic complexation of proteins with polyphenols represents a promising approach to modulate functional properties and enhance bioavailability:

- Non-covalent Complexes: Driven by hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces between polyphenols and proteins [10]. These interactions can improve the solubility and stability of hydrophobic polyphenols in aqueous food matrices [10].

- Covalent Conjugates: Formed through enzyme-mediated (e.g., laccase, tyrosinase) or chemical oxidation (alkaline conditions) approaches, resulting in stable protein-polyphenol conjugates with enhanced functional properties [10]. Covalent conjugates of whey protein with catechins have demonstrated superior antioxidant activity and physical stability in emulsion systems [10].

Polysaccharide-Polyphenol Interactions

Polysaccharides interact with polyphenols through both covalent and non-covalent mechanisms, influencing their bioaccessibility and physiological effects:

- Dietary Fiber Interactions: Plant cell wall polysaccharides can bind polyphenols, potentially reducing their immediate bioaccessibility but enabling controlled release during colonic fermentation [7].

- Encapsulation Matrices: Polysaccharides such as pectin, chitosan, and cyclodextrins can form complexes with polyphenols, protecting them from degradation in the gastrointestinal tract and modulating their release profile [7].

Diagram 2: Advanced Delivery Systems for Polyphenol Bioavailability Enhancement. This diagram outlines strategies to overcome the bioavailability challenges of polyphenols, including nanoencapsulation technologies, protein-polyphenol complexation, and polysaccharide-polyphenol interactions, which enhance solubility, stability, absorption, and targeted delivery.

The comprehensive classification and systematic analysis of dietary sources of major polyphenol classes provide a crucial foundation for understanding their potential applications in functional food development and chronic disease prevention. The structural diversity of polyphenols directly influences their biological activities, bioavailability, and ultimate physiological effects, highlighting the importance of considering specific polyphenol classes and their food matrix interactions when designing functional food products.

Future research directions should focus on optimizing delivery systems to enhance polyphenol bioavailability, conducting well-designed human intervention studies to establish dose-response relationships, and exploring the synergistic effects of polyphenol combinations in complex food matrices. The integration of advanced technologies such as nanoencapsulation, combined with a deeper understanding of polyphenol-gut microbiota interactions, will further advance the application of these bioactive compounds in targeted nutritional strategies for health promotion and disease prevention. As the field evolves, the precise characterization of polyphenol sources and mechanisms will continue to inform the development of evidence-based functional foods capable of modulating specific physiological pathways to improve human health.

The traditional view of dietary polyphenols as simple direct antioxidants that scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) represents an oversimplification of their complex bioactivity. While the scavenger theory—which posits that polyphenols neutralize free radicals through hydrogen atom or electron donation—explains some of their protective effects, a more nuanced understanding has emerged from recent research [11] [12]. Polyphenols exhibit a dualistic nature in biological systems, functioning as antioxidants under certain conditions while acting as pro-oxidants in others, ultimately influencing cellular fate through the modulation of redox signaling pathways [8] [12]. This mechanistic duality is particularly relevant in the context of functional foods research, where understanding the precise molecular interplay is crucial for developing evidence-based nutritional interventions. The progression from simple scavenger theory to the recognition of sophisticated redox signaling represents a paradigm shift in nutritional biochemistry, moving the field beyond chemical antioxidant assays toward a more physiological understanding of polyphenol bioactivity [13] [14].

This technical review examines the core mechanisms governing polyphenol bioactivity, focusing on the chemical basis of antioxidant and pro-oxidant effects, their integration into cellular signaling networks, and the experimental methodologies essential for advancing functional foods research.

The Scavenger Theory: Foundations and Mechanisms

The scavenger theory constitutes the foundational framework for understanding polyphenol antioxidant activity. This mechanism is primarily governed by the direct chemical capacity of polyphenols to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons to neutralize reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [11] [15].

Structural Basis for Free Radical Scavenging

The antioxidant potency of polyphenolic compounds is intrinsically linked to their molecular structure, specifically the arrangement of hydroxyl groups on aromatic rings, which dictates their ability to stabilize unpaired electrons after radical quenching [12].

- Electron Delocalization: The resonant electron system of the polyphenolic aromatic ring enables the stabilization of the resulting phenoxyl radical through electron delocalization across the conjugated system [12]. For example, in the flavonoid luteolin, radicals formed at both the C-7 and C-4' positions are resonance-stabilized due to conjugation with ketone groups or double bonds [12].

- Hydroxyl Group Positioning: The number and position of hydroxyl groups significantly influence antioxidant potential. The catechol group (ortho-dihydroxy benzene) in compounds like hydroxytyrosol and the B-ring of luteolin provides superior radical stabilization compared to single hydroxyl groups [12]. In luteolin, hydroxyl groups at the 7 and 4' positions demonstrate greater antioxidant activity due to enhanced electron delocalization capabilities [12].

- Metal Chelation: Beyond direct scavenging, polyphenols can chelate transition metals such as iron and copper, reducing their availability for participation in Fenton reactions that generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals [12].

Table 1: Structural Features Governing Antioxidant Efficacy in Selected Polyphenols

| Polyphenol | Class | Key Structural Features | Resultant Antioxidant Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luteolin | Flavonoid | Catechol group in B-ring; C-7 and C-4' OH groups | Extensive radical delocalization; high number of resonant forms |

| Hydroxytyrosol | Phenolic alcohol | Catechol group in aromatic ring | Electron delocalization across benzene nucleus |

| Resveratrol | Stilbene | Phenolic OH groups in B-ring; resorcinol in A-rings | Delocalization through C=C double bond between rings |

Direct Antioxidant Mechanisms

Polyphenols employ multiple parallel mechanisms to exert their antioxidant effects in biological systems:

- Radical Neutralization: Polyphenols donate a proton (H+) from their hydroxyl groups to free radicals (•X), including hydroxyl, peroxyl, superoxide, or peroxynitrous acid radicals, converting them to less reactive species while forming stabilized phenoxyl radicals [12].

- Enzyme Modulation: Polyphenols inhibit pro-oxidant enzymes such as lipoxygenase (LO), cyclooxygenase (COX), myeloperoxidase (MPO), NADPH oxidase (NOx), and xanthine oxidase (XO), thereby preventing ROS generation at the source [12]. Concurrently, they stimulate antioxidant enzymes including catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [12].

- Synergistic Regeneration: The reducing environment within cells, maintained by ascorbate and glutathione, can regenerate oxidized polyphenols, allowing for continued antioxidant protection [12].

The Pro-Oxidant Paradox and Redox Signaling

The pro-oxidant capacity of polyphenols, once viewed as an undesirable side effect, is now recognized as an essential component of their bioactivity, particularly in the context of redox signaling and chemoprevention [14] [8].

Pro-Oxidant Mechanisms and Conditions

Polyphenols can generate reactive oxygen species under specific conditions, primarily through two mechanisms:

- Autoxidation and Quinone Formation: In the presence of molecular oxygen and transition metals, polyphenols can autoxidize, forming semiquinone radicals and superoxide anions, which subsequently dismutate to hydrogen peroxide [14] [12]. The initial phenoxyl radical can undergo further oxidation to form quinones, which are resonance-stabilized electrophiles [12].

- Metal Reduction: Polyphenols can reduce transition metal ions (e.g., Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺, Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺), which can then participate in Fenton chemistry to generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals [8].

The balance between antioxidant and pro-oxidant behavior depends on concentration, cellular microenvironment, redox state, and the presence of transition metals [8]. At high concentrations, particularly in the presence of copper ions, polyphenols like naringin, gallic acid, and genistein demonstrate pro-oxidant activity that suppresses cancer cell proliferation and triggers apoptosis [16].

Redox Signaling and Cellular Adaptation

The pro-oxidant activity of polyphenols is not merely a toxicological concern but represents a crucial mechanism for activating adaptive cellular responses:

- Nrf2 Pathway Activation: H₂O₂ generated from extracellular polyphenol autoxidation can diffuse into cells through aquaporin (AQP) channels [14]. This H₂O₂ flux can trigger the oxidation of the Keap1-Nrf2 complex, leading to Nrf2 dissociation and translocation to the nucleus, where it activates the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), driving the expression of endogenous antioxidant enzymes [14].

- AQP-Mediated Regulation: Aquaporins (particularly AQP3, AQP8, and AQP9) in intestinal epithelia function as gatekeepers for H₂O₂ transport, regulating intracellular concentrations and ensuring homeostatic signaling rather than oxidative damage [14]. This mechanism links dietary polyphenol intake with intracellular defense systems.

- Hormetic Response: Mild pro-oxidant challenges from polyphenols can induce a hormetic effect, upregulating endogenous antioxidant capacity and enhancing cellular resilience to subsequent oxidative insults [14] [12].

Experimental Approaches for Assessing Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Activities

Evaluating the dual antioxidant/pro-oxidant character of polyphenols requires a multi-faceted experimental approach spanning chemical, cellular, and in vivo models.

Chemical Antioxidant Assays

Chemical assays provide rapid screening methods for determining antioxidant potential but have limitations in biological relevance [13].

- DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) Assay: Measures hydrogen-donating capacity to stable radical in ethanol or methanol solutions [13].

- ABTS (2,2'-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) Assay: Determines radical cation scavenging activity in aqueous or organic phases [13].

- FRAP (Ferric Reducing/Antioxidant Power): Assesses reduction of ferric-tripyridyltriazine complex to colored ferrous form [13].

- ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity): Quantifies peroxyl radical scavenging through fluorescence monitoring [13].

- PSC (Peroxyl Radical Scavenging Capacity): Measures protection against peroxyl radical-induced oxidation [13].

Table 2: Methodologies for Assessing Polyphenol Redox Activities

| Method Category | Specific Assays/Models | Key Measured Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Assays | DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, ORAC, PSC | Radical scavenging, reducing power | Simple, rapid, high-throughput | Poor physiological correlation; static measurements |

| Cell-Based Assays | Caco-2, HT-29 cells; fluorescent probes (DCFH-DA) | Intracellular ROS; gene expression; cell viability | Closer to biological environment; pathway analysis | Doesn't account for bioavailability; culture artifacts |

| In Vivo Models | Caenorhabditis elegans; rodent models | Biomarkers (MDA, 8-oxoG); enzyme activities; gene expression | Whole-organism complexity; absorption and metabolism | Complex, time-consuming, ethical considerations |

| Biosensors | Laccase/tyrosinase-based electrochemical sensors | Real-time H₂O₂, dopamine, catechin | Dynamic monitoring; high sensitivity | Enzyme instability; matrix interference |

Advanced Methodologies for Redox Signaling Research

- Cell-Based Antioxidant Assays: Utilizing cell lines (e.g., Caco-2 intestinal models) with fluorescent probes like DCFH-DA to monitor intracellular ROS formation and scavenging [13]. These systems allow investigation of polyphenol effects on cellular signaling pathways under more physiologically relevant conditions.

- In Vivo Models: Employing Caenorhabditis elegans or rodent models to assess oxidative damage biomarkers including malondialdehyde (MDA) for lipid peroxidation and 8-oxoguanosine (8-oxoG) for DNA oxidation [13]. These models provide critical information on bioavailability, metabolism, and systemic effects.

- Electrochemical Biosensors: Functionalized with polyphenol oxidases (laccase, tyrosinase) and enhanced with nanomaterials (gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes) for real-time monitoring of oxidative stress biomarkers [17]. These systems achieve detection limits as low as 0.08 μM for dopamine with linear ranges of 0.25–76.81 μM [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Polyphenol Redox Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Antioxidant Assays | DPPH, ABTS, TPTZ (for FRAP) | Initial antioxidant capacity screening | Radical source; oxidation-reduction indicators |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2, HT-29 intestinal cells | Intestinal absorption and bioavailability studies | Human-relevant in vitro model for transport and metabolism |

| Fluorescent Probes | DCFH-DA, DHE | Intracellular ROS measurement | ROS-sensitive fluorophores for flow cytometry or microscopy |

| Enzymatic Biosensors | Laccase, tyrosinase | Real-time oxidation monitoring | Biocatalytic element for analyte detection |

| Nanomaterial Enhancers | Gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes | Biosensor signal amplification | Increased surface area and electron transfer capacity |

| Oxidative Biomarkers | Anti-MDA, anti-8-oxoG antibodies | Lipid and DNA oxidation assessment | Target recognition in ELISA or immunohistochemistry |

| Animal Models | C. elegans, rodent models | In vivo bioactivity validation | Whole-organism response and toxicity assessment |

The biological activity of polyphenols extends far beyond simple radical scavenging, encompassing a sophisticated interplay between antioxidant and pro-oxidant activities that modulates cellular redox signaling pathways. The scavenger theory explains the direct free radical neutralizing capacity of these compounds, while the pro-oxidant effects—particularly the generation of H₂O₂ and quinone formation—activate adaptive cellular responses through the Nrf2 pathway and other redox-sensitive transcription factors [14] [12]. This dualistic behavior is highly dependent on concentration, microenvironment, and cellular context, presenting both challenges and opportunities for functional foods research.

Advancing our understanding of these mechanisms requires integrated methodological approaches combining chemical assays with cell-based systems, advanced biosensors, and physiologically relevant animal models [17] [13]. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise relationships between polyphenol structures and their redox signaling activities, optimizing delivery systems to enhance bioavailability, and validating these mechanisms in human clinical trials. Such efforts will ultimately enable the rational design of functional foods with targeted health benefits mediated through defined molecular pathways.

Inflammation, a complex biological response, is primarily mediated by the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. These pathways regulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and enzymes, and their dysregulation is implicated in numerous chronic diseases. Polyphenols, a diverse class of bioactive compounds found in functional foods, have emerged as potent modulators of these pathways. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms by which polyphenols target NF-κB and MAPK signaling, summarizing key quantitative data and detailing essential experimental methodologies. It is designed to serve as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals exploring the mechanistic basis of polyphenols in functional food research.

Inflammation is a fundamental immune response triggered by various danger signals, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [18]. These signals are sensed by pattern recognition receptors (PPRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which subsequently activate key intracellular signaling cascades. Among these, the Nuclear Factor Kappa-B (NF-κB) and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways are central regulators of the inflammatory response, controlling the expression of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines, adhesion molecules, and inflammatory enzymes like COX-2 and iNOS [18] [19]. The chronic activation of these pathways is a hallmark of many neurological disorders, metabolic syndromes, and other age-related diseases [20] [21]. Consequently, targeting NF-κB and MAPK signaling presents a strategic approach for therapeutic intervention. Polyphenols from dietary sources have demonstrated significant potential to modulate these pathways, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects and contributing to the mechanism of action underlying functional foods [20] [18] [22].

Biology of the NF-κB and MAPK Pathways

The NF-κB Signaling Pathway

NF-κB is a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor that exists in the cytoplasm as an inactive heterodimer, typically composed of p50 and p65 (RelA) subunits, bound to its inhibitory protein, IκBα [19]. Activation occurs via two primary routes: the canonical (classical) and non-canonical (alternative) pathways [20].

- Canonical Pathway: This pathway is activated by a wide range of stimuli, including LPS, IL-1, and TNF-α [20]. Ligand binding to receptors like TLRs initiates a signaling cascade that involves adapter proteins such as MyD88, leading to the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. The IKK complex, comprising IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO (IKKγ), phosphorylates IκBα, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [20] [19]. This degradation liberates the NF-κB dimer, allowing its translocation to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences and promotes the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes [20].

- Non-Canonical Pathway: This pathway is activated by specific ligands like CD40L and BAFF. It involves the activation of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), which phosphorylates IKKα. This leads to the processing of p100 to p52 and the subsequent formation of a p52/RelB dimer that translocates to the nucleus to regulate target gene expression [20].

In the central nervous system, NF-κB is involved in physiological processes such as neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory formation. However, its dysregulation is linked to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's [20].

The MAPK Signaling Pathway

The MAPK pathway is another critical signaling cascade that translates external inflammatory signals into cellular responses. It primarily consists of three key subfamilies: p38, JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase), and ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) [23]. Upon activation by stimuli such as LPS or oxidative stress, a kinase cascade is triggered, leading to the phosphorylation and activation of these MAPKs. Activated p38 and JNK, in particular, are strongly associated with stress and inflammatory responses. They phosphorylate various transcription factors, including AP-1, which cooperate with NF-κB to drive the expression of inflammatory mediators [18] [23]. The MAPK and NF-κB pathways often act in concert, creating a robust and integrated inflammatory signaling network.

The following diagram illustrates the core components and interactions within these pathways, highlighting key points of intervention by polyphenols.

Figure 1: NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways and Polyphenol Modulation. The diagram illustrates how inflammatory stimuli (e.g., LPS) activate cell membrane receptors, triggering both NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Key steps include IKK complex activation leading to IκB degradation and NF-κB nuclear translocation, and MAPK activation leading to AP-1 activation. Polyphenols (green) exert inhibitory effects at multiple points, including kinase activation, IKK phosphorylation, and MAPK phosphorylation [20] [18] [19].

Mechanistic Actions of Polyphenols on NF-κB and MAPK

Polyphenols interfere with inflammatory signaling through multiple mechanisms, primarily by inhibiting the activation and nuclear translocation of key transcription factors. The following table summarizes the effects of specific polyphenols on these pathways and their downstream outputs.

Table 1: Effects of Select Polyphenols on NF-κB and MAPK Pathways and Inflammatory Outputs

| Polyphenol | Source | Molecular Target / Effect | Impact on Inflammatory Mediators | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Turmeric | Inhibits IKK phosphorylation and IκB degradation; prevents NF-κB nuclear translocation [20] [19]. | ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, COX-2 [20] | Preclinical models of neurological disorders [20]. |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, Red Wine | Suppresses TLR4, NF-κB, and MAPK signaling; reduces cytokine secretion [18]. | ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β; ↓ plasma pro-inflammatory markers in AD subjects [18] | Human neuroblastoma cells; LPS-induced mouse models; human subjects with Alzheimer's disease (AD) [18]. |

| Quercetin | Apples, Onions | ↓ TLR2/4 expression and NF-κB activation [18]. | ↓ Activity of inflammatory enzymes [18] | Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells; human PBMC [18]. |

| Anthocyanins | Berries | Inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation; reduces ROS production [18]. | ↓ NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β; ↓ iNOS & COX-2 expression [18] | Mouse BV2 microglial cells; rat models of cerebral ischemia [18]. |

| Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) | Green Tea | ↓ TLR4 signaling [18]. | Improves impaired hippocampal neurogenesis | LPS-induced mouse models [18]. |

| Blueberry Extract | Blueberries | Inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation [18]. | ↓ NO & TNF-α release; ↓ iNOS & COX-2 expression [18] | Mouse BV2 microglial cells (LPS-induced) [18]. |

The anti-inflammatory activity of polyphenols is largely attributed to their ability to disrupt the phosphorylation and ubiquitination processes that are crucial for signal propagation. For instance, they can inhibit IKK activity, thereby preventing the degradation of IκB and the subsequent release of NF-κB [20] [19]. Additionally, polyphenols like quercetin and resveratrol have been shown to downregulate the expression of TLRs, the initial sensors of inflammatory stimuli [18]. By acting at these upstream points, polyphenols effectively dampen the entire inflammatory cascade, reducing the production of a wide array of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Models for Investigating Neuroinflammation

In vitro models provide a controlled system for elucidating the specific molecular mechanisms of polyphenol action. Commonly used models include:

- Cell Lines: Immortalized cell lines like mouse BV2 microglial cells and human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells are widely used due to their reproducibility and ease of culture.

- Induction of Inflammation: Inflammation is typically induced using Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the gram-negative bacterial cell wall that is a potent agonist of TLR4 [18] [24]. Common concentrations range from 100 ng/mL to 1 µg/mL, depending on the cell type and desired intensity of the inflammatory response.

- Treatment Protocol: Cells are typically pre-treated with the polyphenol of interest for a period (e.g., 1-2 hours) prior to LPS challenge. The co-incubation of polyphenol and LPS then continues for a defined period, often 6-24 hours, after which cells and supernatants are collected for analysis [18].

- Key Assays:

- Cell Viability: Measured using assays like the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) to ensure that anti-inflammatory effects are not due to cytotoxicity [23].

- Gene Expression: mRNA levels of cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) are quantified using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The 2−ΔΔCT method is used for analysis, with GAPDH or β-actin as housekeeping genes [23].

- Protein Analysis: Protein expression and phosphorylation (e.g., p38, JNK, p65, IκBα) are analyzed by western blotting. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation can be used to assess NF-κB translocation [18] [23].

- Cytokine Secretion: Levels of secreted cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) in cell culture supernatants are measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) [23].

In Vivo Models and Human Challenge Studies

In vivo models are essential for validating findings from cell-based studies within a complex physiological context.

- LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation Models: Mice or rats are administered LPS systemically (intraperitoneally or intravenously) or directly into the brain (intracerebroventricularly) [24]. Doses vary widely, from low doses (0.5-2 mg/kg) for systemic inflammation to higher doses for robust neuroinflammation. Polyphenols are administered orally or via injection prior to or following LPS challenge.

- Measured Outcomes: These include behavioral tests (e.g., for sickness behavior, memory), analysis of brain tissue for cytokine levels and microglial activation, and assessment of signaling pathway molecules via immunohistochemistry or western blot [18] [24].

- Human LPS Challenge Studies: These controlled clinical studies involve administering very low doses of LPS (e.g., 0.5 - 2 ng/kg) intravenously to healthy volunteers to induce a transient inflammatory response [25]. Biomarkers like TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and CRP are measured longitudinally. Mathematical models have been developed to characterize the dynamics and inter-individual variability of these inflammatory biomarkers, providing a quantitative framework for translating preclinical findings to humans [25].

The following diagram outlines a typical experimental workflow from in vitro validation to in vivo and clinical investigation.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating Polyphenol Effects. A typical research pipeline begins with in vitro models to establish mechanism, proceeds to in vivo animal models for physiological validation, and can extend to controlled human challenge studies for clinical translation and quantitative modeling of biomarker dynamics [18] [23] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential reagents, inhibitors, and models used in research targeting NF-κB and MAPK pathways.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NF-κB and MAPK Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Model | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A potent TLR4 agonist used to induce robust inflammatory signaling in both in vitro and in vivo models [18] [24]. | Inducing cytokine production in microglial cell cultures; modeling systemic inflammation or neuroinflammation in rodents [18]. |

| IKK/NF-κB Pathway Inhibitors (e.g., BAY 11-7082) | A selective pharmacological inhibitor of IKK that prevents IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent NF-κB activation [23]. | Used as a positive control to confirm NF-κB-dependent effects in experiments. Validates polyphenol mechanisms targeting the IKK complex [23]. |

| MAPK Pathway Inhibitors (e.g., SB202190 for p38, PD98059 for JNK) | Selective inhibitors that block the activity of specific MAPK pathways (p38 and JNK, respectively) [23]. | Used to dissect the contribution of specific MAPK branches to the overall inflammatory response and to compare with polyphenol effects [23]. |

| Mouse BV2 Microglial Cell Line | An immortalized cell line that retains many characteristics of primary microglia. A standard model for studying neuroinflammation [18]. | Screening the anti-inflammatory effects of polyphenols in a relevant neural cell type following LPS challenge [18]. |

| IPEC-1 (Intestinal Porcine Epithelial Cells) | A non-transformed intestinal epithelial cell line used to study gut barrier integrity and inflammation [23]. | Modeling oxidative stress-induced intestinal inflammation (e.g., with H₂O₂) and testing protective effects of polyphenols [23]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Immunoassays for the quantitative detection of specific proteins (e.g., cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6) in cell supernatants, serum, or tissue homogenates. | Measuring the output of NF-κB/MAPK pathway activation and the efficacy of polyphenol intervention [23]. |

| Human LPS Challenge Model | A controlled clinical model where healthy volunteers receive a low, safe dose of IV LPS to trigger a transient, measurable inflammatory response [25]. | Translating preclinical findings; studying the dynamics of human inflammatory biomarkers and testing the efficacy of polyphenol-rich interventions [25]. |

The NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways represent central hubs in the regulation of the inflammatory response. Polyphenols, as naturally occurring bioactive compounds, exhibit multifaceted mechanisms to modulate these pathways, primarily by inhibiting key kinase activities and preventing the nuclear translocation of transcription factors. The evidence derived from robust in vitro and in vivo models, supplemented by emerging data from human challenge studies, solidifies the rationale for incorporating these compounds into functional food strategies aimed at mitigating chronic inflammation. Future research should focus on optimizing the bioavailability of polyphenols, understanding their synergistic effects, and validating their long-term efficacy through well-designed clinical trials, thereby fully unlocking their potential as targeted modulators of inflammation in human health and disease.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex and dynamic ecosystem of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota, which functions as a critical metabolic interface between dietary intake and host physiology [26]. Comprising primarily the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia, this microbial consortium expands the host's metabolic capabilities through an immense enzymatic repertoire [27]. Among the various dietary components processed by this system, polyphenols—a large group of secondary plant metabolites—have garnered significant scientific interest for their limited bioavailability and consequent extensive interaction with gut microbes [26] [28]. Approximately 90-95% of ingested polyphenols resist absorption in the upper gastrointestinal tract and reach the colon, where they undergo substantial microbial biotransformation [28]. This process not only liberates bioactive metabolites but also exerts prebiotic-like effects by selectively modulating microbial composition, positioning the gut microbiota as a central metabolic hub in mediating the health benefits of polyphenol-rich functional foods [29] [30] [27]. This review examines the mechanisms of this interplay within the context of functional foods research, detailing the biotransformation pathways, resultant microbial shifts, and methodologies for their investigation.

Polyphenols are a heterogeneous group of phytochemicals characterized by the presence of phenolic rings and hydroxyl groups. Their structural diversity underpins their classification, bioavailability, and ultimate bioactivity [31]. The following table summarizes the primary classes, their subcategories, dietary sources, and key features relevant to gut microbiota interactions.

Table 1: Classification, Sources, and Features of Major Dietary Polyphenols

| Class | Subclass | Key Examples | Major Dietary Sources | Bioavailability Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Flavonols | Quercetin, Kaempferol | Onions, tea, lettuce, broccoli, apples [26] | Variable; extensive microbial metabolism [31] |

| Flavanols | Catechins, Gallocatechin | Tea, red wine, chocolate [26] | Low bioavailability [31] | |

| Flavanones | Naringenin, Hesperetin | Oranges, grapefruits [26] | ||

| Anthocyanins | Pelargonidin, Delphinidin | Blackcurrant, strawberries, red wine [26] | Low bioavailability [31] | |

| Isoflavones | Genistein, Daidzein | Soybeans, legumes [26] | Highest bioavailability among polyphenols [31] | |

| Flavones | Apigenin, Luteolin | Parsley, celery, red pepper [26] | ||

| Phenolic Acids | Hydroxybenzoic acids | Gallic acid, Vanillic acid | Raspberries, blackberries, onions [26] | |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid | Cereals, fruits [26] | ||

| Stilbenes | Resveratrol | Red wine, grapes, peanuts [26] | ||

| Lignans | Pinoresinol, Secoisolariciresinol | Flaxseed, sesame seed, whole grains [26] [31] | Require microbial activation to enterolignans [29] |

The bioavailability of these compounds is a critical determinant of their bioactivity. It is influenced by factors such as chemical structure, degree of polymerization, and food processing methods [31]. Notably, polyphenols with higher molecular weight and greater complexity, such as proanthocyanidins and ellagitannins, are poorly absorbed and thus predominantly metabolized in the colon [28].

Microbial Biotransformation of Polyphenols

Upon reaching the colon, dietary polyphenols undergo extensive enzymatic modification by the gut microbiota, a process that converts them into absorbable, low-molecular-weight phenolic metabolites with altered—and often enhanced—biological activities [28].

Key Metabolic Pathways and Bacterial Actors

The biotransformation processes are diverse and include reactions such as hydrolysis, ring cleavage, decarboxylation, dehydroxylation, and hydrogenation [29]. These reactions are catalyzed by specific bacterial enzymes, sometimes termed PAZymes ((Poly)phenol-Associated Enzymes) [27].

The following diagram illustrates the general journey of polyphenols through the gastrointestinal tract and their subsequent biotransformation by gut microbiota.

Specific bacterial genera and species are crucial for metabolizing particular polyphenols, leading to the production of characteristic metabolites [29]:

- Isoflavones (e.g., Daidzein): Certain gut bacteria, including strains from the phyla Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, metabolize daidzein into equol or O-desmethylangolensin (ODMA) [29]. Individuals are classified as equol producers (EP) or non-producers (ENP) based on this metabolic capacity.

- Ellagitannins and Ellagic Acid: These compounds, found in pomegranates and berries, are hydrolyzed to ellagic acid, which is further transformed by bacteria from the genera Gordonibacter, Ellagibacter, and Enterocloster into urolithins (e.g., Urolithin A and B) [29] [32]. This gives rise to urolithin metabotypes (UMA, UMB, UM0).

- Lignans: Plant lignans like secoisolariciresinol are converted to enterolignans (enterodiol and enterolactone) by species such as Lactonifactor longoviformis and Ruminococcus spp. [29].

These microbial metabolites often exhibit enhanced bioavailability and possess potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective activities compared to their parent compounds [28]. They are key mediators of the systemic health benefits associated with polyphenol consumption.

Prebiotic-like Effects and Modulation of the Microbiota

The interaction between polyphenols and the gut microbiota is bidirectional. While microbiota metabolize polyphenols, the polyphenols, in turn, act as prebiotic-like compounds, selectively modulating the composition and function of the microbial community [26] [29] [27]. According to the current definition, a prebiotic is "a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit" [26]. Polyphenols fit this definition through a dual mode of action, potentially classified as a "duplibiotic" effect: stimulating beneficial bacteria while inhibiting pathogenic ones [27].

Selective Modulation of Bacterial Populations

Numerous preclinical and clinical studies demonstrate that polyphenol consumption leads to significant shifts in gut microbiota profiles. The table below summarizes the effects of specific polyphenols on key bacterial taxa.

Table 2: Effects of Dietary Polyphenols on Gut Microbiota Composition

| Polyphenol / Source | Key Microbial Changes | Context of Evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catechins, Anthocyanins, Proanthocyanidins | ↑ Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium spp. | Preclinical (Animal) Studies | [30] |

| Pomegranate (Ellagitannins) | ↑ Lactobacillus, Enterococcus | RCT (Overweight/Obesity) | [29] |

| Cocoa Flavan-3-ols | ↑ Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans, Flavonifractor plautii | RCT (Athletes) | [29] |

| General Flavonoids & Lignans | ↑ Lactobacillus, Sutterella | Cohort Study (High vs. Low Consumers) | [29] |

| Ellagic Acid | ↑ Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium spp.; Antimicrobial vs. E. coli | Clinical Trials & In Vitro | [29] [30] |

The stimulation of beneficial bacteria is often accompanied by an increase in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, which is crucial for colonic health and systemic anti-inflammatory effects [30]. Concurrently, polyphenols can exert antimicrobial effects against potential pathogens, helping to maintain a healthy microbial equilibrium [29] [27].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Polyphenol-Microbiota Interactions

Elucidating the complex relationship between polyphenols and the gut microbiota requires a multi-faceted approach. Below is a detailed methodology for a comprehensive investigation, integrating in vitro and in vivo models with modern omics technologies.

In Vitro Fermentation Models

- Purpose: To simulate the human colon environment for studying polyphenol metabolism and acute microbial responses under controlled conditions.

- Protocol:

- Inoculum Preparation: Collect fresh fecal samples from healthy human donors. Homogenize in anaerobic phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0) under a constant stream of CO₂.

- Fermentation System: Use a bioreactor containing a defined culture medium (e.g., YCFA) and the fecal inoculum. Maintain strict anaerobic conditions at 37°C with continuous pH control.

- Intervention: Introduce the polyphenol of interest (e.g., purified compound or plant extract) at a physiologically relevant concentration (e.g., 50-200 µg/mL) to the test reactor. A control reactor receives no polyphenols.

- Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours) for subsequent analysis.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Microbiota Composition: 16S rRNA gene sequencing (e.g., V3-V4 region) on the collected samples.

- Metabolite Profiling: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to identify and quantify polyphenol-derived metabolites (e.g., urolithins, equol) and SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate).

- Functional Metagenomics: Shotgun sequencing of metagenomic DNA to assess changes in the microbial gene content, particularly pathways involved in polyphenol metabolism [29] [28].

In Vivo Animal Studies

- Purpose: To assess the physiological impact of polyphenol consumption on the gut microbiota and host health within a whole-organism context.

- Protocol:

- Animal Model: Use specific pathogen-free C57BL/6J mice (or a relevant disease model, e.g., high-fat diet-induced obesity).

- Study Design: Randomize mice into control and treatment groups (n=8-12). The treatment group receives a defined diet supplemented with the polyphenol (e.g., 0.5% w/w grape seed proanthocyanidins), while the control group receives an isocaloric diet.

- Intervention Duration: A minimum of 8-12 weeks.

- Sample Collection: At sacrifice, collect cecal content, fecal pellets, blood, and tissue samples (e.g., liver, muscle, colon).

- Analysis:

- Gut Microbiota: 16S rRNA sequencing of cecal/fecal content.

- Metabolomics: LC-MS/MS analysis of plasma and cecal content for phenolic metabolites.

- Host Phenotype: Measure body weight, fat mass, glucose tolerance (IPGTT), insulin sensitivity. Analyze tissues for markers of inflammation (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), intestinal barrier function (e.g., zonulin-1, occludin), and metabolic pathways [28] [32].

Human Clinical Trials

- Purpose: To validate findings from pre-clinical models in humans and account for inter-individual variability (e.g., metabotypes).

- Protocol (Randomized Controlled Trial):

- Participant Recruitment: Enroll overweight or obese adults (e.g., BMI 28-35 kg/m²). Exclude individuals with recent antibiotic/probiotic use or chronic GI diseases.

- Study Design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm trial. Participants are randomized to receive either a polyphenol-rich intervention (e.g., 500 mg/day of a specific polyphenol extract) or an identical placebo for 8-12 weeks.

- Dietary Control: Implement a run-in period with controlled, low-polyphenol diet. Maintain dietary records throughout the study.

- Sample Collection: Collect fasting blood and stool samples at baseline and post-intervention.

- Analysis:

- Microbiome: Shotgun metagenomics on stool DNA for high-resolution taxonomic and functional profiling.

- Metabolomics: Untargeted and targeted metabolomics on plasma and urine to profile microbial and host metabolites.

- Health Markers: Measure clinical endpoints like LDL-cholesterol, HOMA-IR, inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP, LPS-binding protein) [29] [30].

- Metabotyping: Stratify participants based on their capacity to produce specific metabolites (e.g., equol or urolithin producers vs. non-producers) for sub-group analysis [29].

The workflow for integrating these methodologies is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Research in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents, biological materials, and analytical platforms. The following table outlines essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Investigating Polyphenol-Microbiota Interactions

| Category | Item | Specific Example / Model | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol Reagents | Standardized Extracts | Grape seed proanthocyanidins, Green tea catechins | Provide a defined, reproducible polyphenol source for interventions. |

| Purified Compounds | Resveratrol, Quercetin, Genistein | Allow for precise mechanistic studies of single compounds. | |

| Biological Models | In Vitro Model | SHIME (Simulator of Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem) | Simulates different regions of the human GI tract for dynamic fermentation studies. |

| Animal Model | C57BL/6J mouse (wild-type or specific disease model) | Provides a whole-organism system to study host-microbe interactions. | |

| Bacterial Strains | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Akkermansia muciniphila, Gordonibacter spp. | Used for in vitro co-culture or metabolism studies to define specific pathways. | |

| Analytical Tools | Metagenomics Kits | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN) | High-quality DNA extraction from complex fecal/cecal samples for sequencing. |

| Metabolomics Platform | UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS (Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry) | Identifies and quantifies a broad range of polyphenol metabolites and microbial products. | |

| SCFA Analysis | GC-FID (Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionization Detection) | Quantifies short-chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, butyrate) from fermentation samples. | |

| Software & Databases | Bioinformatics Tool | QIIME 2, HUMAnN 2 | Processes 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing data for taxonomic and functional analysis. |

| Metabolomics Database | HMDB (Human Metabolome Database), Metlin | Aids in the identification of microbial and host metabolites. |

The gut microbiota unequivocally functions as a critical metabolic hub that extensively biotransforms dietary polyphenols, giving rise to a spectrum of bioactive metabolites with systemic health effects. Simultaneously, polyphenols exert prebiotic-like effects, selectively modulating the microbial ecosystem towards a more beneficial composition. This intricate, bidirectional interaction is a fundamental mechanism underlying the efficacy of polyphenol-rich functional foods. Future research must prioritize standardized methodologies, long-term human studies, and a deeper molecular understanding of the involved bacterial enzymes and pathways. Furthermore, accounting for inter-individual variability in gut microbiota composition—through concepts like metabotyping—will be essential for developing personalized nutritional strategies that fully leverage the potential of polyphenols to promote human health.

Within the framework of functional foods research, dietary polyphenols have emerged as a major class of bioactive compounds with significant potential for managing metabolic and neurological disorders. Their ability to modulate the activity of key enzymes is a fundamental mechanism of action. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the inhibition mechanisms of polyphenols against three critical enzymatic targets: xanthine oxidase (XO)—central to purine metabolism and hyperuricemia; digestive enzymes (α-amylase, α-glucosidase, lipase)—crucial for managing postprandial glycemia and obesity; and acetylcholinesterase (AChE)—a key target in Alzheimer’s disease therapy. The discussion is framed by structure-activity relationships (SAR), detailed experimental methodologies for characterizing these interactions, and the implications for developing targeted functional foods and natural therapeutic strategies.

Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition and Hyperuricemia Management

Xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) is a molybdenum-containing flavoprotein that catalyzes the final two steps in purine catabolism: the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid. Hyperuricemia, a condition characterized by elevated serum uric acid levels, is a key risk factor for gout and is associated with chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases [33]. XO is a primary therapeutic target for this condition.

Structural Basis of XO Inhibition by Polyphenols

XOR exists as a homodimer, with each subunit containing three redox cofactor domains: a 20 kDa N-terminal iron-sulfur cluster (2Fe/S), a 40 kDa flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) domain, and an 85 kDa C-terminal molybdopterin cofactor (MOC) domain where substrate oxidation occurs [33]. The MOC active site is hydrophobic and lined with key residues that facilitate inhibitor binding.

- Key Residue Interactions: Polyphenols, particularly flavonoids, bind within the MOC active site. Crystallographic studies of the quercetin/XOR complex reveal that the planar flavonoid structure interacts with Phe914 and Phe1009 via π-π stacking forces. Furthermore, van der Waals forces form with hydrophobic residues Leu873, Leu1014, Leu648, Val1011, and Phe1013 [33]. Critical hydrogen bonds are often established between the hydroxyl groups of the flavonoid and catalytic residues Glu802 and Arg880, which are essential for substrate orientation and the final protonation and release of uric acid [33]. The binding of inhibitors can induce conformational changes that tighten the "pocket portion" of the active site, involving residues like Thr1010, further impairing substrate access [33].

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) of Flavonoids:

- Hydroxylation: The presence and position of hydroxyl groups are critical. Hydroxylation at the C5 and C7 positions of the A-ring consistently enhances XO inhibitory activity [33]. The effect of B-ring hydroxylation (e.g., at C3' and C4') is less pronounced, as similar activities are observed for kaempferol (4'-OH), quercetin (3',4'-OH), and myricetin (3',4',5'-OH) [33].

- Glycosylation: The attachment of sugar moieties to the flavonoid aglycone (glycosylation) dramatically reduces XO inhibitory activity compared to their aglycone counterparts [33].

- Methylation: Methoxy groups can enhance inhibitory effects, likely by increasing hydrophobicity and facilitating better penetration into the enzyme's active site [33].

- Planar Structure: A coplanar configuration between the A and C rings stabilizes binding within the planar active site through enhanced π-π interactions [33].

Table 1: Inhibitory Activity (IC50) of Selected Polyphenols and Drugs against Xanthine Oxidase

| Compound Class / Name | IC50 Value | Reference Compound & IC50 |

|---|---|---|

| Chalcone derivative (Compound 2) | 0.064 µM | Febuxostat: 0.028 µM [34] |

| Benzaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (Compound 3) | 0.0437 µM | Allopurinol: 7.56 µM [34] |

| Myricetin | Information missing from search results | Allopurinol: 0.2-50 µM [34] |

| Quercetin | Information missing from search results | Allopurinol: 0.2-50 µM [34] |

| Allopurinol (Drug) | 0.2 - 50 µM | - [34] |

| Febuxostat (Drug) | 0.028 µM | - [34] |

Experimental Protocol for XO Inhibition Kinetics

Objective: To determine the inhibitory potency (IC50) and mechanism of a polyphenol compound against xanthine oxidase.

Reagents:

- Xanthine oxidase (from bovine milk)

- Xanthine substrate

- Test polyphenol compound (dissolved in DMSO or buffer)

- Phosphate buffer (pH 7.5)

- Allopurinol or Febuxostat (positive control)

Method:

- Enzyme Activity Assay: The assay monitors uric acid production at 295 nm spectrophotometrically. Reaction mixtures contain phosphate buffer, various concentrations of xanthine substrate, and XO enzyme, with or without the inhibitor [33] [34].

- IC50 Determination: The enzyme activity is measured in the presence of a range of inhibitor concentrations. The IC50 value (concentration causing 50% inhibition) is calculated by plotting inhibition percentage versus inhibitor concentration.

- Kinetic Mechanism Analysis: Initial reaction rates are measured at varying substrate (xanthine) concentrations and several fixed inhibitor concentrations. The data are plotted as Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plots.

- Competitive Inhibition: Lines intersect on the y-axis.

- Non-competitive Inhibition: Lines intersect on the x-axis.

- Mixed-type Inhibition: Lines intersect in the second quadrant [34].

- Molecular Docking: Computational docking simulations (e.g., using AutoDock Vina) are performed to visualize the binding pose of the polyphenol within the XO active site (e.g., PDB ID: 1FIQ). Key interactions (H-bonds, π-π stacking, van der Waals) with residues like Glu802, Arg880, and Phe914 are identified [33] [34].

Diagram 1: XO inhibition kinetics and analysis workflow.

Inhibition of Digestive Enzymes for Metabolic Health

The inhibition of carbohydrate- and lipid-digesting enzymes is a primary mechanism by which polyphenols exert anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects. This reduces postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia by decreasing the absorption of glucose and fatty acids [35] [36].

Targets and SAR of Digestive Enzyme Inhibition

- α-Amylase & α-Glucosidase: These enzymes break down complex carbohydrates into absorbable sugars.

- Inhibition Mechanism: Polyphenols act primarily through non-covalent binding—van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions—often leading to non-competitive or mixed-type inhibition [35]. They can bind to the active site or other regions, inducing conformational changes.

- SAR: Molecular weight, the number and position of hydroxyl groups, and glycosylation status influence potency. Generally, larger polymeric polyphenols (e.g., tannins) are more effective inhibitors than monomeric forms. For flavonoids, hydroxyl groups on the A and C rings are important [35].

- Lipase: This enzyme hydrolyzes dietary triglycerides into fatty acids and monoglycerides.

- Inhibition Mechanism: Polyphenols bind to lipase, often at the enzyme's surface or near the active site, preventing it from accessing its lipid substrate at the oil-water interface [35].

- SAR: Hydrophobic interactions are key. Compounds with higher hydrophobicity can more effectively disrupt the enzyme's interaction with lipid droplets.

Table 2: Inhibitory Activity (IC50) of Selected Polyphenols against Digestive Enzymes

| Enzyme | Compound Class / Name | IC50 Value | Inhibition Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase | Tannic Acid | Information missing from search results | Competitive [36] |

| α-Amylase | Caffeic Acid | Information missing from search results | Competitive [36] |

| α-Glucosidase | Acarbose (Drug) | Information missing from search results | Competitive [37] |

| Lipase | Orlistat (Drug) | Information missing from search results | Information missing from search results |

Ternary Interactions: Polyphenols, Dietary Fiber, and Digestive Enzymes

In whole foods, polyphenols do not act in isolation. A critical phenomenon is their interaction with dietary fiber, which can modulate bioactivity [36].

- Fiber-Polyphenol Complexes: During processing or digestion, polyphenols can form complexes with insoluble dietary fiber (e.g., cellulose) via non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic) [36].

- Impact on Inhibition: These complexes can have distinct inhibitory effects on digestive enzymes. A fiber-polyphenol conjugate may inhibit α-amylase more effectively than the polyphenol or fiber alone, due to the combined molecular barrier effect of the fiber and the specific enzyme-binding ability of the polyphenol [36]. This highlights the importance of the food matrix in determining functional outcomes.

Experimental Protocol for Digestive Enzyme Inhibition

Objective: To assess the inhibitory activity of a polyphenol extract on α-amylase and pancreatic lipase.

Reagents for α-Amylase Assay:

- Pancreatic α-amylase

- Starch solution

- DNS reagent (3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid)

- Phosphate buffer (pH 6.9)

- Acarbose (positive control)

Method for α-Amylase:

- The reaction mixture containing buffer, α-amylase, and the test polyphenol is pre-incubated.

- Starch solution is added to initiate the reaction, which is stopped after a fixed time using DNS reagent.

- The mixture is heated, and the reduction of DNS to 3-amino-5-nitrosalicylic acid is measured at 540 nm, corresponding to the amount of maltose released. Reduced absorbance indicates enzyme inhibition [35].

Reagents for Lipase Assay:

- Pancreatic lipase

- p-Nitrophenyl palmitate (pNPP) or triolein emulsion

- Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.2)

- Orlistat (positive control)

Method for Lipase (using pNPP):

- Lipase is incubated with the test polyphenol in buffer.

- The substrate pNPP is added. Upon hydrolysis by lipase, it releases yellow-colored p-nitrophenol.

- The increase in absorbance at 405-410 nm is monitored. A lower rate of increase indicates lipase inhibition [35].

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by a cholinergic deficit, where a decrease in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) leads to cognitive decline. Inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE), the enzyme that hydrolyzes ACh, is a primary therapeutic strategy [38] [39].

Structural Mechanism and Synergistic Effects

AChE has a deep active-site gorge with two primary ligand-binding sites: the Catalytic Anionic Site (CAS) at the bottom and the Peripheral Anionic Site (PAS) near the rim.

- Key Residue Interactions: Polyphenols can bind to either or both sites.

- Inhibition Mechanism: Binding occurs via hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and π-π stacking with aromatic residues like Trp84 [38]. Multiple hydroxyl groups on the polyphenol enhance binding affinity and inhibitory potency [38].

- Synergistic Inhibition: Combinations of different polyphenols can produce enhanced effects. A study on Phyllanthus emblica Linn. fruit polyphenols showed that a combination of myricetin, quercetin, fisetin, and gallic acid exhibited a synergistic inhibition of AChE in a mixed-type manner, which was more effective than the sum of their individual effects [39].

Table 3: Inhibitory Activity (IC50) of Selected Polyphenols against Acetylcholinesterase (AChE)

| Compound Name | IC50 Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Myricetin | 0.1974 ± 0.0047 mM | Phyllanthus emblica Linn. [39] |

| Quercetin | 0.2589 ± 0.0131 mM | Phyllanthus emblica Linn. [39] |

| Fisetin | 1.0905 ± 0.0598 mM | Phyllanthus emblica Linn. [39] |

| Gallic Acid | 1.503 ± 0.0728 mM | Phyllanthus emblica Linn. [39] |

| Resveratrol | 1.66 µmol/L | Vitis amurensis [38] |

| Curcumin | 19.67 µmol/L | Purified form [38] |

Experimental Protocol for AChE Inhibition and Interaction Studies

Objective: To determine the IC50, inhibition kinetics, and binding parameters of a polyphenol with AChE.

Reagents:

- Acetylcholinesterase (e.g., from electric eel)

- Acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh) or Acetylcholine (ACh)

- 5,5'-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, Ellman's reagent)

- Phosphate buffer (pH 8.0)

- Donepezil or Galantamine (positive control)

Method:

- Ellman's Assay: The reaction mixture contains buffer, DTNB, AChE, and the test compound. The reaction is initiated with ATCh. AChE hydrolyzes ATCh to thiocholine, which reacts with DTNB to produce 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (TNB), a yellow anion measured at 412 nm. Inhibitor activity reduces the rate of color development [39].

- IC50 and Kinetic Analysis: Performed similarly to the XO protocol, using varying ATCh and inhibitor concentrations with Lineweaver-Burk analysis to determine the inhibition modality (e.g., competitive for myricetin, non-competitive for gallic acid) [39].

- Fluorescence Quenching Spectroscopy: The intrinsic fluorescence of AChE (mainly from tryptophan residues) is measured (excitation ~280 nm, emission ~300-400 nm) with increasing concentrations of the polyphenol. A decrease in fluorescence intensity indicates binding. The data are analyzed using the Stern-Volmer equation to determine the quenching constant (Ksv) and deduce a static (complex formation) or dynamic (collisional) quenching mechanism [39].

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Far-UV CD spectra (190-260 nm) of AChE are recorded with and without the polyphenol. Changes in the spectra (e.g., increase in α-helix, decrease in β-sheet) indicate conformational alterations in the enzyme's secondary structure induced by polyphenol binding [39].

Diagram 2: AChE active site gorge and polyphenol binding mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Enzyme Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Assay Kit | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|