Beyond Nutrients: Integrating Nutri-Score and NOVA for a Comprehensive Food Assessment in Biomedical Research

This article provides a critical analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the synergistic application of the Nutri-Score and NOVA food classification systems.

Beyond Nutrients: Integrating Nutri-Score and NOVA for a Comprehensive Food Assessment in Biomedical Research

Abstract

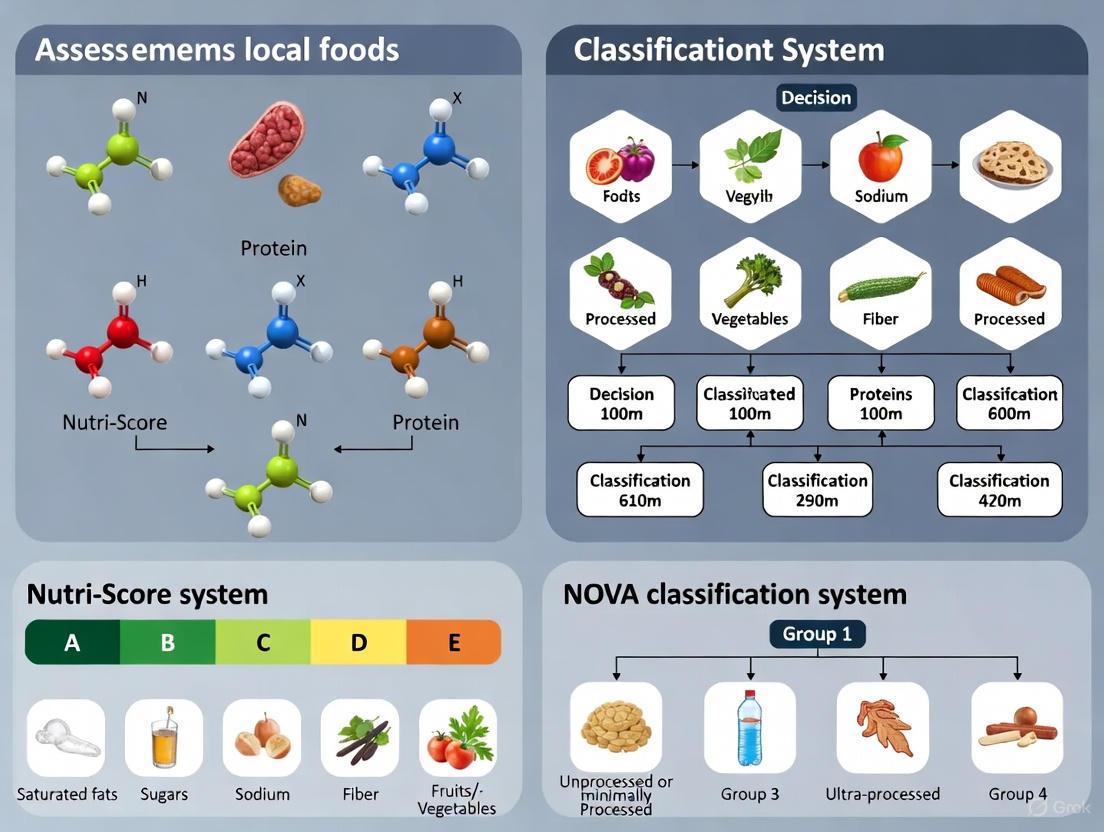

This article provides a critical analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the synergistic application of the Nutri-Score and NOVA food classification systems. It explores the foundational principles of both frameworks, where Nutri-Score evaluates nutritional composition and NOVA assesses the degree of industrial processing. The content details methodological approaches for integrated food assessment, addresses prevalent classification challenges and limitations, and examines the growing body of evidence validating each system's association with health outcomes. By synthesizing these two dimensions, this resource aims to equip scientists with a more nuanced toolkit for dietary exposure assessment in clinical and public health nutrition research, ultimately informing the development of targeted nutritional interventions and therapies.

Decoding the Frameworks: Foundational Principles of Nutri-Score and NOVA Classification

The escalating global burden of diet-related chronic diseases represents one of the most significant public health challenges of the 21st century [1]. Non-communicable diseases including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and cancer have become leading causes of premature mortality worldwide, responsible for approximately 80% of premature deaths from non-communicable diseases [1]. The economic costs are equally staggering, with the social cost of overweight and obesity alone estimated at approximately €20 billion (1% of GDP) in France [1]. Nutrition serves as a key modifiable determinant underlying this crisis, creating a powerful lever for public health intervention [1]. This application note provides researchers with validated methodologies for assessing the nutritional quality and processing characteristics of foods using the Nutri-Score and NOVA classification systems within local food assessment research contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Assessment Frameworks

Nutri-Score: Nutrient-Based Profiling System

The Nutri-Score is a simplified, front-of-pack nutrition label that characterizes the overall nutritional quality of foods using a five-point color-coded scale from dark green (A) to dark orange (E) [1]. Developed by independent academic researchers and officially adopted in France in 2017, this system aims to allow consumers to quickly compare nutritional quality at point of purchase while encouraging manufacturers to improve product formulations through reformulation [1].

The underlying algorithm calculates a score based on both favorable components (fruit, vegetables, nuts, fiber, protein) and unfavorable components (energy, sugars, saturated fat, sodium) per 100g of product [1]. The scientific basis originates from the British Food Standards Agency nutrient profiling model, validated by extensive research on its association with health outcomes [1]. Recent studies demonstrate its effectiveness in guiding institutional food procurements, with research in Norwegian high schools showing that Nutri-Score aligned well with national school meal guidelines and could serve as a complementary tool for evaluating food purchases [2].

NOVA: Food Processing Classification System

The NOVA system classifies foods based on the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial processing rather than nutritional composition [3]. Developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, NOVA categorizes foods into four distinct groups:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods (fresh fruits, vegetables, eggs, meat, milk) [4]

- Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients (oils, butter, sugar, salt) [4]

- Group 3: Processed foods (canned vegetables, cheeses, fresh bread) [4]

- Group 4: Ultra-processed foods (soft drinks, sweetened breakfast cereals, reconstituted meat products) [4]

Ultra-processed foods are industrial formulations typically containing multiple ingredients, including additives not used in home cooking, designed to be hyper-palatable and convenient [3]. The system addresses limitations of conventional food classifications that often group nutritionally dissimilar foods together (e.g., whole grains with sugary cereals) [3].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Food Assessment Frameworks

| Feature | Nutri-Score | NOVA Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Nutrient composition | Degree and purpose of processing |

| Classification Basis | Algorithm balancing favorable/unfavorable nutrients | Industrial processing methods and ingredients |

| Output Format | 5-point scale (A-E with color codes) | 4-category classification |

| Key Strengths | Validated against health outcomes; Consumer-friendly design | Captures non-nutrient aspects of food quality; Addresses food system impacts |

| Key Limitations | Does not account for processing degree or additives | Does not directly address nutrient profile; Classification challenges for complex products |

Experimental Protocols for Local Food Assessment

Protocol for Nutri-Score Calculation and Application

Objective: To calculate Nutri-Score values for food products and assess their distribution within a local food environment.

Materials:

- Food composition data (per 100g/100ml) for energy, sugars, saturated fat, sodium, protein, fiber, fruits/vegetables/nuts

- Nutri-Score calculation algorithm

- Database management software (e.g., Excel, R, Python)

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Compile nutritional information for target food products from nutrition labels, manufacturer specifications, or chemical analysis.

- Point Allocation:

- Calculate points (0-10) for unfavorable components: energy (kJ), sugars (g), saturated fatty acids (g), and sodium (mg)

- Calculate points (0-5) for favorable components: percentage of fruits/vegetables/nuts/rapeseed/walnut/olive oils (%); and dietary fiber (g) and protein (g)

- Final Score Computation:

- Compute final score: Points (unfavorable components) - Points (favorable components)

- Apply specific adjustments for certain food categories (beverages, added fats, cheeses)

- Classification:

- Translate final scores to Nutri-Score categories: A (≤-1), B (0 to 2), C (3 to 10), D (11 to 18), E (≥19) for solid foods; different thresholds apply for beverages, added fats, and cheeses

- Validation:

- Cross-reference calculations with established databases where available

- Conduct sensitivity analysis for borderline cases

Implementation Notes:

- For mixed dishes, calculate based on overall composition per 100g

- For dried products (e.g., soups), consider preparation state unless specified otherwise

- The 2023 updated algorithm provides modified thresholds for specific food categories including beverages, added fats, and cheeses [1]

Protocol for NOVA Classification of Packaged Foods

Objective: To classify food products according to NOVA categories with particular focus on identifying ultra-processed foods.

Materials:

- Food products with complete ingredient lists

- Reference guide for food additives and industrial processes

- Standardized classification template

Procedure:

- Ingredient Analysis:

- Obtain complete ingredient lists for all target products

- Identify industrial ingredients (e.g., high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, protein isolates)

- Flag food substances not commonly used in home kitchens (e.g., maltodextrin, carrageenan, artificial sweeteners)

- Process Evaluation:

- Assess processing methods described or implied by ingredient list and product form

- Identify processing techniques uncommon in home kitchens (e.g., extrusion, pre-frying for stability)

- Categorization:

- Apply NOVA classification criteria systematically:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed (fresh, frozen, dried foods without additives)

- Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients (substances used to prepare Group 1 foods)

- Group 3: Processed foods (simple products with added salt, sugar, or oil)

- Group 4: Ultra-processed foods (industrial formulations with multiple ingredients including additives)

- Apply NOVA classification criteria systematically:

- Validation:

- Conduct independent dual classification with resolution of discrepancies through panel discussion

- Consult reference classifications for ambiguous products

- Document reasoning for borderline cases

Implementation Notes:

- For complex products, consider the primary purpose and nature of processing rather than simply counting ingredients

- Recognize that some traditional processed foods (cheeses, breads) may belong to Group 3 rather than Group 4

- A new tool, WISEcode, has been developed to provide a more nuanced classification of processed foods, addressing limitations of the NOVA system which may over-categorize foods as ultra-processed [5]

Protocol for Integrated Assessment combining Nutri-Score and NOVA

Objective: To evaluate foods using both nutrient profiling and processing dimensions for comprehensive characterization.

Materials:

- Completed Nutri-Score calculations

- NOVA classifications

- Integrated assessment framework

Procedure:

- Data Integration:

- Create a matrix with both classification results for each product

- Identify patterns and discrepancies between systems

- Analysis:

- Calculate proportion of products with concordant classifications (e.g., Nutri-Score D/E and NOVA 4)

- Identify discordant products (e.g., Nutri-Score A/B but NOVA 4, or Nutri-Score D/E but NOVA 1-3)

- Statistically analyze relationships between classifications using appropriate tests (chi-square, correlation)

- Interpretation:

- Contextualize findings within local dietary patterns and public health priorities

- Identify categories where processing or nutrient quality dominates health considerations

Data Analysis and Visualization Framework

Logical Relationship Between Assessment Systems

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship and complementary nature of the Nutri-Score and NOVA classification systems in public health nutrition research:

Comparative Validation Data

Recent research validates the complementary application of these systems. A 2025 study of child-targeted foods in Türkiye found that 92.7% of products were ultra-processed (NOVA 4), and 70% received Nutri-Score D or E ratings, demonstrating significant concordance between poor nutritional quality and high processing levels [6]. The integrated analysis revealed that ultra-processed foods had significantly lower nutritional quality (p < 0.001) according to Nutri-Score [6].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Assessment Systems in Recent Studies

| Study Context | Nutri-Score Findings | NOVA Findings | Integrated Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Targeted Foods in Türkiye (n=775 products) [6] | 70% of products classified as D or E | 92.7% classified as ultra-processed | Significant association between NOVA 4 and lower Nutri-Score ratings (p<0.001) |

| Greek Adult Population (n=220) [7] | Not assessed | GR-UPFAST tool showed negative correlation with Mediterranean diet (rho=-0.162, p=0.016) | UPF consumption positively correlated with body weight (rho=0.140, p=0.039) |

| Food Pantry Intervention (n=187 clients) [8] | Not primary focus | 41.1-43.5% of energy from UPFs across conditions | Behavioral economics intervention showed no significant reduction in UPF selection |

| Norwegian School Food Procurement [2] | Good agreement with national school meal guidelines; effective for evaluation | Not assessed | Proposed target: ≥65% expenditure on Nutri-Score A/B foods; ≤15% on E-rated foods |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Food Assessment Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) | Standardized nutrient analysis and dietary assessment | Provides detailed nutritional information and food subgroup categorization; requires manual coding for NOVA classification [8] |

| GR-UPFAST (Greek Ultra Processed Food intake Assessment Tool) | Assess UPF consumption frequency | Validated tool (Cronbach's α=0.766) with 28 items; useful for Mediterranean populations [7] |

| Food Compass 2.0 | Comprehensive nutrient profiling system | Updated system (2024) incorporating processing and ingredients; validated against health outcomes [9] |

| WISEcode Classification System | Nuanced evaluation of processed foods | Addresses NOVA limitations with weighted scoring of ingredients and health concerns [5] |

| Open Food Facts Database | Crowdsourced product information | Provides ingredient lists and nutritional data for classification; useful for manual verification [8] |

The complementary application of Nutri-Score and NOVA classification systems provides researchers with a robust methodological framework for addressing the public health burden of diet-related chronic diseases through local food assessment. While Nutri-Score effectively evaluates nutritional composition and aligns with health outcome data, NOVA captures important dimensions related to food processing and industrial formulation. The experimental protocols outlined in this application note enable standardized assessment across diverse food environments, facilitating evidence-based public health interventions and policies aimed at creating healthier food systems.

The Nutri-Score is a five-color nutrition label and nutritional rating system designed to provide consumers with simplified, at-a-glance information about the overall nutritional value of food products [10]. Developed by independent academic researchers specializing in nutrition and public health, this front-of-pack labeling system was officially adopted by France in 2017 and has since been implemented in several European countries including Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Switzerland [1] [11]. The system assigns products a rating letter from A (dark green) to E (dark orange), with associated colors from green to red, creating a visual gradient that enables rapid comparison of similar food products [10] [11].

The fundamental public health objective of the Nutri-Score is to combat the growing burden of diet-related chronic diseases by empowering consumers to make more informed nutritional choices without requiring specialized nutritional knowledge [1] [11]. This system emerged in response to the recognition that traditional back-of-package nutrition tables, consisting primarily of numerical data, were rarely used by consumers due to their complexity and difficulty of interpretation [1]. By translating complex nutritional information into a simple, color-coded visual format, the Nutri-Score aims to guide consumers toward products with more favorable nutritional compositions while simultaneously encouraging food manufacturers to improve their products through reformulation [1].

Algorithm and Nutrient Profiling Model

Core Calculation Methodology

The Nutri-Score algorithm is derived from the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (FSA) nutrient profiling system, initially developed at Oxford University [1] [10]. This scientifically validated algorithm operates on a balancing principle between detrimental and beneficial nutritional components, calculating a final score that determines the letter grade and color displayed on packaging [10].

The calculation process follows a structured three-step approach:

- Negative points (N) are calculated based on the content of nutrients considered problematic when consumed in excess: energy density (kcal/100g), sugar content (g/100g), saturated fatty acids (g/100g), and sodium/salt content (mg/100g) [10].

- Positive points (P) are calculated based on the content of nutrients and food components considered beneficial: fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, fiber (g/100g), and protein (g/100g) [10].

- The total score is computed by subtracting the positive points from the negative points, with special adjustments for certain food categories [10].

Table 1: Nutri-Score Negative Points Calculation Matrix

| Points | Energy (kcal/100g) | Sugars (g/100g) | Saturated Fat (g/100g) | Sodium (mg/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ≤ 80 | ≤ 4.5 | ≤ 1.0 | ≤ 90 |

| 1 | 81-160 | > 4.5 | > 1.0 | > 90 |

| 2 | 161-240 | > 9.0 | > 2.0 | > 180 |

| 3 | 241-320 | > 13.5 | > 3.0 | > 270 |

| 4 | 321-400 | > 18.0 | > 4.0 | > 360 |

| 5 | 401-480 | > 22.5 | > 5.0 | > 450 |

| 6 | 481-560 | > 27.0 | > 6.0 | > 540 |

| 7 | 561-640 | > 31.0 | > 7.0 | > 630 |

| 8 | 641-720 | > 36.0 | > 8.0 | > 720 |

| 9 | 721-800 | > 40.0 | > 9.0 | > 810 |

| 10 | > 800 | > 45.0 | > 10.0 | > 900 |

Table 2: Nutri-Score Positive Points Calculation Matrix

| Points | Fruits, Vegetables, Nuts, Legumes (%) | Fibre (g/100g) | Protein (g/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | < 40% | < 0.7 | < 1.6 |

| 1 | ≥ 40% | ≥ 0.7 | ≥ 1.6 |

| 2 | ≥ 60% | ≥ 1.4 | ≥ 3.2 |

| 3 | - | ≥ 2.1 | ≥ 4.8 |

| 4 | - | ≥ 2.8 | ≥ 6.4 |

| 5 | ≥ 80% | ≥ 3.5 | ≥ 8.0 |

Food Category Modifications

The standard Nutri-Score algorithm incorporates specific modifications for particular food categories to better align with public health recommendations and nutritional science:

- Cheese: The protein content is always considered in the calculation, regardless of the total negative score [10].

- Added fats (e.g., vegetable oils, butter): The ratio of saturated fats to total fat content is considered instead of the absolute saturated fat amount, and only energy from saturated fats is counted rather than total energy content [10].

- Beverages: Different calculation parameters apply, with stricter thresholds for negative components [10].

Classification Thresholds

The final Nutri-Score classification is determined by the total points calculated from the algorithm, with the following thresholds defining the letter grades:

Table 3: Nutri-Score Classification Thresholds

| Nutri-Score | Color | Point Range |

|---|---|---|

| A | Dark Green | -15 to -1 |

| B | Light Green | 0 to 2 |

| C | Yellow | 3 to 10 |

| D | Orange | 11 to 18 |

| E | Red | 19 to 40 |

Algorithm Updates for 2023-2025

The Nutri-Score algorithm has undergone scientific revisions to improve its alignment with current nutritional evidence and public health guidelines. Key updates include:

- Modified scoring for sugars, using a point allocation scale aligned with 3.75% of the 90g reference value [10].

- Revised salt component scoring, aligned with 3.75% of the 6g reference value [10].

- Adjusted fiber and protein components using scales aligned with nutrient claim regulations [10].

- Removal of nuts and specific oils (rapeseed, walnut, olive) from the "Fruit, Vegetables, Legumes" component [10].

- Simplification of the final computation by removing the protein cap exemption for products with high fruit and vegetable content [10].

These updates have demonstrated improved correlation with healthy fat sources (fish, seafood, vegetable oils, plain nuts) and whole-grain products in validation studies [12].

Experimental Protocols for Nutri-Score Application and Validation

Protocol 1: Calculating Nutri-Score for Food Products

Purpose: To determine the correct Nutri-Score classification for a specific food product using its nutritional composition data.

Materials and Equipment:

- Complete nutritional composition data per 100g or 100ml of product

- Nutri-Score calculation tables or algorithm

- Excel spreadsheet or specialized software for automated calculation

Procedure:

- Compile Nutritional Data: Gather precise measurements for energy (kcal), sugars (g), saturated fatty acids (g), sodium (mg), fiber (g), protein (g), and percentage of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes.

- Calculate Negative Points (N): Using Table 1, determine points for energy density, sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. Sum these for total negative points.

- Calculate Positive Points (P): Using Table 2, determine points for fruits/vegetables/nuts/legumes content, fiber, and protein. Sum these for total positive points.

- Compute Final Score: Subtract positive points (P) from negative points (N): Final Score = N - P.

- Assign Nutri-Score Classification: Using Table 3, match the final score to the corresponding Nutri-Score letter (A-E).

- Category-Specific Adjustments: Apply modifications for cheese, added fats, or beverages if applicable.

Validation: Verify calculation using multiple methods (manual, automated tool) and cross-reference with similar products for consistency.

Protocol 2: Validating Nutri-Score Against Population Dietary Data

Purpose: To assess how well the Nutri-Score discriminates dietary quality at a population level, as performed in the ESTEBAN study [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- 24-hour dietary recall data from a representative population sample

- Food composition database

- Statistical analysis software (R, SAS, or SPSS)

- Nutri-Score calculation algorithm

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Collect detailed dietary intake data through repeated 24-hour dietary recalls from a representative sample population.

- Compute Individual Dietary Index: For each participant, calculate a dietary index as the average of Nutri-Score values of all foods consumed, weighted by their energy contributions.

- Categorize Participants: Group participants into quartiles based on their dietary index scores.

- Analyze Nutrient Intakes: Compare intakes of key nutrients (proteins, fibers, vitamins, minerals, saturated fats, added sugars) across quartiles using ANOVA and linear contrasts.

- Examine Food Consumption Patterns: Assess consumption frequencies of different food groups (fish, vegetable oils, whole grains, etc.) across score quartiles.

- Correlate with Biomarkers: Where available, analyze associations with blood concentrations of relevant nutrients (β-carotene, vitamin B9, etc.).

- Statistical Comparison: Use Spearman correlations to evaluate the continuous relationship between the dietary index and nutritional outcomes.

Validation: Compare discriminatory power of different Nutri-Score algorithm versions and establish consistency with expected dietary patterns.

Protocol 3: Assessing Nutri-Score Impact on Food Purchases

Purpose: To evaluate how Nutri-Score labeling influences consumer purchasing behavior and nutritional quality of food baskets.

Materials and Equipment:

- Retail sales data (value and volume)

- Loyalty card or digital shopping basket data

- Nutritional composition database

- Statistical modeling software

Procedure:

- Baseline Data Collection: Collect pre-implementation sales data for product categories carrying Nutri-Score labeling.

- Post-Implementation Monitoring: Track sales data after Nutri-Score introduction, noting changes in market share for different score categories.

- Calculate Basket Nutritional Quality: Develop a nutritional quality score for entire shopping baskets using the Grocery Basket Score (GBS) methodology [13].

- Longitudinal Analysis: Compare nutritional quality of purchases before and after Nutri-Score implementation using paired statistical tests.

- Control Group Analysis: Compare results with regions or stores without Nutri-Score implementation where possible.

- Reformulation Assessment: Monitor product reformulations by manufacturers seeking to improve their Nutri-Score.

Validation: Use control groups, interrupted time series analysis, and multivariate regression to account for confounding factors.

Comparative Analysis with NOVA Food Classification System

NOVA System Framework

The NOVA classification system, developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo, categorizes foods based on the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial processing rather than nutritional composition [4] [3]. This system divides foods into four distinct groups:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods - Naturally occurring foods with no added salt, sugar, oils, or fats; includes fresh fruits and vegetables, milk, eggs, meat, poultry, fish, plain yogurt, grains, and pasta [4].

- Group 2: Processed Culinary Ingredients - Substances derived from Group 1 foods or from nature through processes like pressing, refining, grinding, or milling; includes vegetable oils, butter, salt, sugar, and honey [4].

- Group 3: Processed Foods - Simple products made by adding sugar, oil, salt, or other Group 2 ingredients to Group 1 foods; includes canned vegetables, fruits in syrup, salted nuts, cheeses, and freshly made breads [4].

- Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods - Industrial formulations created with multiple ingredients, including additives not typically used in home cooking; includes soft drinks, sweet or savory packaged snacks, mass-produced breads, cookies, ready-to-heat meals, and various reconstituted meat products [4] [3].

Conceptual and Methodological Differences

The fundamental distinction between Nutri-Score and NOVA lies in their assessment frameworks: Nutri-Score evaluates nutritional composition, while NOVA categorizes based on processing level. This leads to significant divergences in how specific foods are classified:

Table 4: Comparative Classification of Select Foods by Nutri-Score and NOVA

| Food Product | Typical Nutri-Score | NOVA Group | Classification Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar-sweetened soda | E | Group 4 (Ultra-processed) | Consistent |

| Plain unsweetened yogurt | A/B | Group 1 (Unprocessed) | Divergent |

| Whole-grain breakfast cereal | B/C | Group 4 (Ultra-processed) | Divergent |

| Canned vegetables with salt | C/D | Group 3 (Processed) | Partial |

| Vegetable oil | C/D | Group 2 (Culinary ingredients) | Partial |

| Hummus with stabilizers | Variable | Group 4 (Ultra-processed) | Context-dependent |

The NOVA system has been particularly influential in highlighting the health implications of ultra-processed foods, with prospective studies linking higher consumption to increased risks of obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality [3]. However, critics note that NOVA's exclusive focus on processing level may overlook the nutritional value of some ultra-processed foods, such as whole-grain breads, fortified breakfast cereals, and yogurts, which can contribute beneficial nutrients despite their processed nature [4].

Integration Potential for Research

For comprehensive food assessment research, integrating both systems provides complementary insights:

- Use Nutri-Score to evaluate nutritional quality within specific food categories

- Apply NOVA to understand the role of food processing in dietary patterns

- Combine both systems to identify products that are both highly processed and nutritionally poor versus those that may be processed but nutritionally adequate

The National Cancer Institute provides standardized methods for applying the NOVA classification system to dietary data collected through tools like ASA24 and NHANES, enabling researchers to systematically analyze food processing levels in population studies [14].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Nutritional Assessment Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) | Standardized dietary analysis software with food composition database | Coding and analyzing dietary intake data from recalls or records |

| Automated Self-Administered 24-hour (ASA24) Dietary Assessment Tool | Self-administered web-based tool for collecting dietary intake data | Large-scale population studies of food consumption patterns |

| Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) | Comprehensive database of food compositions used by NHANES | Linking food intake data to nutritional composition for analysis |

| NHANES Dietary Data | Nationally representative survey data with detailed dietary components | Epidemiological studies linking diet to health outcomes |

| NOVA Classification Framework | Standardized protocol for categorizing foods by processing level | Assessing impact of food processing on health independent of nutrition |

| Healthy Eating Index (HEI) | Diet quality measure assessing alignment with Dietary Guidelines | Validating other nutrition metrics against established standards |

| Grocery Basket Score (GBS) | Nutrient profiling model for entire shopping baskets | Evaluating nutritional quality of food purchases at retail level |

Visualizations

Nutri-Score Calculation Workflow

Nutri-Score and NOVA Conceptual Relationship

The Nutri-Score system represents a significant advancement in public health nutrition by translating complex nutritional information into an accessible, visually intuitive format. Its scientifically validated algorithm balances both detrimental and beneficial nutritional components, enabling consumers to make rapid comparisons between similar products. The ongoing refinement of the algorithm, including the 2023-2025 updates, demonstrates the system's capacity to incorporate emerging nutritional science and maintain alignment with public health guidelines.

For research applications, particularly in local food assessment studies, combining Nutri-Score with the NOVA classification system provides complementary perspectives on food quality—evaluating both nutritional composition and processing level. The experimental protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with standardized methodologies for applying, validating, and assessing the impact of these systems in various contexts. As front-of-pack nutritional labeling continues to evolve globally, the Nutri-Score remains at the forefront of evidence-based approaches to combating diet-related chronic diseases through consumer empowerment and food product reformulation.

The NOVA classification system is a framework for grouping edible substances based on the extent and purpose of food processing applied to them. Developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, and first proposed in 2009, NOVA has become a significant tool in nutrition and public health research worldwide [15]. The system's name means "new" in Portuguese and originates from the title of the original scientific article, "A new classification of foods" [15]. NOVA operates on the central thesis that the nature, extent, and purpose of food processing—rather than just nutrient content—explain the modern relationship between food, nutrition, and health [3].

This system was created in response to significant limitations in conventional food classifications, which often group foods based on botanical origin or animal species and according to nutrient content, thereby combining foods with vastly different health effects [3]. For instance, traditional classifications might group whole grains with sugared breakfast cereals or fresh chicken with chicken nuggets, sidelining the crucial dimension of food processing [3]. The NOVA framework addresses this gap by focusing on processing characteristics, making it particularly relevant for understanding contemporary dietary patterns and their health implications.

The Four NOVA Categories

The NOVA system classifies all foods and food substances into four distinct groups based on the nature, extent, and purpose of the industrial processing they undergo [15]. These groups range from unprocessed foods to formulations designed specifically for convenience and hyper-palatability.

Group 1: Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods

Definition: Unprocessed foods are the edible parts of plants (such as seeds, fruits, leaves, stems, roots) or of animals (muscles, offal, eggs, milk), and also fungi, algae and water, after separation from nature [15]. Minimally processed foods are natural foods altered by processes that include removal of inedible or unwanted parts, drying, crushing, grinding, fractioning, filtering, roasting, boiling, pasteurization, refrigeration, freezing, placing in containers, vacuum packaging, or non-alcoholic fermentation [15]. None of these processes adds substances such as salt, sugar, oils or fats to the original food [4].

Key Features:

- Preserve the integrity and nutritional composition of the original food

- No addition of salt, sugar, oils, fats, or other culinary ingredients

- Typically free of food additives [15]

- Processes used are primarily to extend shelf life, facilitate preparation, or make foods safer or more enjoyable to eat

Examples: Fresh, squeezed, chilled, frozen, or dried fruits and leafy vegetables; grains such as brown rice, corn kernel, wheat berry; legumes such as beans, lentils; starchy roots and tubers such as potatoes, cassava; eggs; fresh or frozen meat, poultry and fish; fresh or pasteurized milk; plain yogurt with no added sugar; mushrooms; fungi; algae; spices; herbs; plain tea, coffee, drinking water [15] [4].

Group 2: Processed Culinary Ingredients

Definition: Processed culinary ingredients are substances derived from Group 1 foods or from nature by processes such as pressing, refining, grinding, milling, and drying [15]. These ingredients are typically not consumed alone but used in home and restaurant kitchens to prepare, season, and cook Group 1 foods [4].

Key Features:

- Extracted and purified from whole foods or natural sources

- Used in combination with Group 1 foods for meal preparation

- Generally free of additives, though some may include added vitamins or minerals (e.g., iodized salt) [15]

- Often require industrial processes for extraction and purification

Examples: Vegetable oils (olive, corn, sunflower); butter; lard; sugar and molasses from cane or beet; honey extracted from combs; syrup from maple trees; salt mined from earth or sea; starches extracted from corn and other plants [15] [4].

Group 3: Processed Foods

Definition: Processed foods are relatively simple products made by adding processed culinary ingredients (Group 2) such as salt, sugar, or oil to unprocessed or minimally processed foods (Group 1) [15]. They are typically made through processes that include baking, boiling, canning, bottling, and non-alcoholic fermentation [15].

Key Features:

- Usually contain two or three ingredients

- Processes aim to extend the durability of Group 1 foods or modify their sensory qualities

- May include additives to preserve original properties or prevent microbial growth

- Recognizably modified versions of Group 1 foods

Examples: Canned vegetables, fruits, and legumes; salted or sugared nuts and seeds; salted, cured, or smoked meats; canned fish; fruits in syrup; cheeses; freshly made breads [15] [4]. Breads, pastries, cakes, biscuits, snacks, and some meat products fall into this group when they are made predominantly from Group 1 foods with the addition of Group 2 ingredients [15].

Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods

Definition: Ultra-processed foods (UPF) are industrial formulations manufactured from substances derived from foods or synthesized from other organic sources [3]. They typically contain little or no whole foods, are ready-to-consume or heat up, and are made with multiple ingredients, including additives whose purpose is to make the final product palatable or hyper-palatable [3] [15].

Key Features:

- Industrial formulations typically containing five or more ingredients [16]

- Often include ingredients of no culinary use (e.g., protein isolates, hydrogenated oils, maltodextrin, high-fructose corn syrup) [15]

- Contain cosmetic additives (flavors, colors, emulsifiers) to imitate sensory properties of Group 1 foods or disguise undesirable qualities [15]

- Designed to be profitable (low-cost ingredients), convenient (ready-to-consume), and hyper-palatable [15]

- Typically branded aggressively and marketed intensely

Examples: Soft drinks; sweet or savory packaged snacks; ice cream; candies (confectionery); mass-produced packaged breads and buns; margarines and other spreads; cookies (biscuits); pastries; cakes; cake mixes; breakfast cereals; cereal and energy bars; milk drinks; cocoa drinks; meat and chicken extracts; infant formulas; health and slimming products; ready-to-heat products such as pizzas, pies, pasta and chicken nuggets; and powder and instant soups [3] [15].

Table 1: Summary of NOVA Food Classification Groups

| NOVA Group | Description | Primary Purpose | Typical Ingredients | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods | Edible parts of plants, animals, fungi, algae, water with minimal alteration | Preservation, safety, preparation ease | Single whole foods; no added substances | Fresh/frozen fruits/vegetables, grains, legumes, eggs, fresh meat/fish, milk, plain yogurt [15] [4] |

| Group 2: Processed Culinary Ingredients | Substances derived from Group 1 foods or nature | Use in cooking and seasoning Group 1 foods | Extracted/purified components; rarely contain additives | Oils, butter, sugar, salt, honey, starches, vinegar [15] [4] |

| Group 3: Processed Foods | Simple products made by adding Group 2 ingredients to Group 1 foods | Extend shelf life, enhance sensory qualities | Group 1 foods + Group 2 ingredients; may include preservatives | Canned vegetables/fish, salted nuts, cheese, fresh bread, fruits in syrup [15] [4] |

| Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods | Industrial formulations with multiple ingredients | Create profitable, convenient, hyper-palatable products | Little/no whole foods; industrial ingredients; cosmetic additives | Soft drinks, sweet/savory snacks, mass-produced breads, cookies, ready-to-heat products [3] [15] |

Methodological Protocols for NOVA Classification

General Classification Workflow

Applying the NOVA classification system in research settings requires a systematic approach to accurately categorize food items. The classification process should follow a defined hierarchy of information sources to ensure consistency and reproducibility across studies.

Primary Data Collection Protocol:

- Product Identification: Record product name, brand, weight, and exact count for all food items [8] [17].

- Nutritional Information: Document all available nutritional information from packaging, including energy density, sugars, saturated fats, sodium, fiber, and protein content per 100g or 100mL [8] [17].

- Ingredient Analysis: Obtain complete ingredient lists, prioritizing branded product information from manufacturer websites or standardized databases [8] [17].

Hierarchical Classification Protocol: When assigning NOVA categories, researchers should follow this decision hierarchy:

- First: Use detailed product descriptions from standardized nutritional databases (e.g., Nutrition Data System for Research) [8] [17].

- Second: Consult raw data files that include specific brand information [8] [17].

- Third: Obtain ingredient lists from brand websites, USDA FoodData Central Branded Foods Database, or Open Food Facts [8] [17].

- Fourth: Apply standardized classification protocols for specific food types when brand information is unavailable (e.g., unsweetened applesauce categorized as Nova 1; applesauce sweetened with natural sweeteners categorized accordingly) [17].

Specific Decision Rules:

- For mixed categories like "fruit juices and drinks," further classification is required: 100% juices are classified as Nova 1, while flavored or sweetened fruit drinks are classified as Nova 4 [8].

- Plain, unsweetened yogurt is classified as Group 1, while sweetened or flavored yogurt typically falls into Group 4 [4].

- Freshly made bread using minimal ingredients (flour, water, salt, yeast) is Group 3, while mass-produced bread with emulsifiers, preservatives, or other additives is Group 4 [15].

Figure 1: NOVA Classification Decision Workflow

Quantitative Assessment Protocol

For research studies analyzing dietary patterns, the following protocol enables quantitative assessment of NOVA category consumption:

Energy Share Calculation Method:

- Categorization: Classify all food items selected or consumed according to NOVA categories [8] [17].

- Caloric Assessment: Calculate the total caloric content of foods within each NOVA category [8] [17].

- Percentage Calculation: Determine the energy share (% of total calories) represented by each NOVA food category using the formula: Energy Share (%) = (Calories from NOVA Category / Total Calories) × 100 [8] [17].

Statistical Analysis Framework:

- Use adjusted mixed linear models to test differences in energy share of NOVA categories between intervention conditions or population groups [8] [17].

- Control for potential confounding variables including demographics, food pantry usage, and cardiovascular health metrics where applicable [8] [17].

- Report mean values and standard deviations for energy shares across NOVA categories to enable cross-study comparisons [8] [17].

Research Reagents and Materials for NOVA-Based Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for NOVA Classification Studies

| Research Tool | Function in NOVA Research | Key Features | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) | Standardized nutritional analysis | Provides product descriptions and detailed nutritional information; designates food subgroups | Primary nutritional analysis in food pantry intervention studies [8] [17] |

| USDA FoodData Central Branded Foods Database | Brand-specific product information | Contains comprehensive ingredient and nutrient data for branded products | Verifying ingredient lists for accurate NOVA classification [8] [17] |

| Open Food Facts | Crowdsourced product database | Provides ingredient lists, nutritional information, and NOVA classifications | Supplementary source for product-specific classification [8] |

| Healthy Eating Index (HEI) | Diet quality assessment | Measures alignment with Dietary Guidelines for Americans | Parallel assessment of diet quality alongside NOVA analysis [8] [4] |

Relationship Between NOVA and Nutri-Score

Complementary Food Assessment Frameworks

The NOVA classification system and the Nutri-Score represent two distinct but potentially complementary approaches to evaluating foods. While NOVA focuses exclusively on food processing dimensions, Nutri-Score is a nutrient profiling system that assesses the nutritional quality of foods based on their composition [10] [1].

Nutri-Score Algorithm Overview: Nutri-Score calculates a score based on both negative and positive nutritional components:

- Negative points (N): Based on energy density, sugar, saturated fatty acids, and salt content per 100g [10].

- Positive points (P): Based on content of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, fiber, and protein [10].

- Final Score: Calculated as N - P, with resulting scores from -15 to +40 corresponding to letter grades from A (best) to E (worst) [10].

Conceptual Integration: The two systems can be integrated to provide a more comprehensive food assessment, as they evaluate different dimensions of food quality [15]. NOVA addresses processing characteristics while Nutri-Score evaluates nutritional composition, together providing insights into both the processing methods and nutrient profile of foods.

Figure 2: Integrated Food Assessment Framework Combining NOVA and Nutri-Score

Comparative Analysis in Research Settings

Studies comparing these classification systems have demonstrated their distinct perspectives on food quality:

Areas of Divergence:

- Some foods classified as ultra-processed by NOVA may receive favorable Nutri-Score ratings due to their nutrient profile (e.g., whole-grain breakfast cereals, flavored yogurts, industrially produced whole-grain breads) [4].

- Conversely, some minimally processed foods traditional to certain cuisines may receive poor Nutri-Score ratings despite their minimal processing (e.g., cheeses, certain meats, added fats) [18].

Research Implications:

- The systems should be viewed as complementary rather than competing frameworks [15].

- Combined use provides a more holistic assessment of food quality, addressing both processing techniques and nutritional composition [4].

- Recent developments in nutrient profiling systems like Food Compass 2.0 attempt to integrate both processing and nutritional dimensions into a single score [9].

Applications in Public Health and Nutritional Epidemiology

Health Outcomes Associations

The NOVA classification system has been increasingly used to evaluate relationships between food processing and health outcomes. Epidemiological studies employing NOVA have identified significant associations between ultra-processed food consumption and various health conditions.

Table 3: Documented Health Outcomes Associated with Ultra-Processed Food Consumption

| Health Outcome | Association Strength | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Obesity | Strong positive association | UPF consumption linked to increased BMI and risk of overweight/obesity in prospective studies [15] [4] |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Significant association | Prospective cohort studies show increased CVD risk with higher UPF consumption [15] [4] |

| Type 2 Diabetes | Significant association | Large prospective cohort studies demonstrate increased risk with higher UPF intake, though some UPF subgroups show protective effects [4] |

| All-Cause Mortality | Dose-response relationship | Systematic review found 15% increased all-cause mortality with every 10% increase in daily UPF caloric consumption [8] |

| Metabolic Syndrome | Significant association | Studies link UPF consumption with increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome [15] |

| Certain Cancers | Moderate association | Research indicates associations between UPF consumption and various cancer types [15] |

Global Public Health Implementation

The NOVA framework has informed food and nutrition policies internationally:

- Brazil: The Ministry of Health incorporated NOVA principles into its dietary guidelines, recommending that citizens "always prefer natural or minimally processed foods and freshly made dishes and meals to ultra-processed foods" [15].

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Has adopted the NOVA classification in its dietary guidelines and reports [15].

- United Nations: Recognized the relevance of food processing in addressing malnutrition as part of the UN Decade of Nutrition (2016-2025) [3].

The system's emphasis on social and economic aspects of food processing has made it particularly valuable for addressing sustainability concerns in addition to health impacts [15].

Limitations and Critical Perspectives

While the NOVA system has gained significant traction in public health nutrition, it has also received critical appraisal from food science and nutritional perspectives:

Classification Challenges:

- Ambiguity in Categorization: Some foods do not fit neatly into NOVA categories, requiring subjective decisions by researchers [16]. For example, breads can fall into Group 3 or Group 4 depending on specific ingredients and production methods [15].

- Ingredient Counting: The system's tendency to classify foods with more than five ingredients as ultra-processed has been criticized as arbitrary, as many traditional recipes and artisanal products contain multiple ingredients [16].

- Neglect of Nutritional Quality: NOVA does not directly address the nutritional content of foods, potentially categorizing nutrient-dense formulated foods together with nutrient-poor products [4] [16].

Scientific Critiques:

- Oversimplification of Processing: Some food scientists argue that NOVA does not accurately categorize foods by processing level and instead focuses primarily on the number of ingredients [16].

- Negative Connotations: The term "ultra-processed" has been criticized for its pejorative connotations toward industrially manufactured foods, regardless of their nutritional value [16].

- Limited Validation: Some researchers have questioned whether NOVA is suitable for scientific control, noting that healthiness does not have a direct correlation with the number of ingredients or processing intensity [16].

These limitations highlight the importance of using NOVA in conjunction with other assessment tools like Nutri-Score to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of food quality [4].

The contemporary landscape of nutritional science is characterized by two predominant frameworks for evaluating food quality: one focusing on nutrient composition and the other on the degree and purpose of industrial processing. The Nutri-Score system operates primarily on the former principle, using a scientific algorithm to classify foods based on their content of both favorable and unfavorable nutrients [1]. In contrast, the NOVA food classification system categorizes foods based on the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial processing, with particular emphasis on identifying ultra-processed foods (UPF) [3]. This application note provides researchers with structured methodologies to quantitatively assess and compare these frameworks for local food assessment research, detailing specific protocols, analytical procedures, and visualization tools to elucidate the distinct insights each approach provides.

Theoretical Framework and Classification Systems

The Nutri-Score System: A Nutrient-Based Approach

The Nutri-Score algorithm translates complex nutritional information into a simple, color-coded label ranging from A (dark green) to E (dark orange). This system is grounded in a nutrient profiling model that assigns points based on the content of specific nutrients per 100g of food or beverage [1].

Calculation Algorithm: The model balances "negative" components (calories, saturated fats, sugars, and sodium) against "positive" components (protein, fiber, and percentages of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes). The final score determines the letter classification, allowing consumers to compare products within the same category or across different brands of the same product type [1].

Scientific Validation: The algorithm underlying Nutri-Score has been validated through numerous studies examining its association with food consumption patterns, nutrient intake, nutritional status biomarkers, and health outcomes in prospective studies [1].

The NOVA System: A Processing-Based Approach

The NOVA system classifies all foods into one of four groups based on the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial processing:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods (e.g., fresh fruits, vegetables, eggs, milk, grains, meat) [3]

- Group 2: Processed Culinary Ingredients (e.g., oils, butter, sugar, salt) [3]

- Group 3: Processed Foods (e.g., canned vegetables, salted meats, fresh bread, cheese) [3]

- Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods - industrial formulations typically containing five or more ingredients, including substances not commonly used in home cooking such as flavors, colors, emulsifiers, and other cosmetic additives [3]

The NOVA system posits that ultra-processing represents a fundamental shift in food systems, creating products designed to be hyper-palatable, convenient, and profitable, often at the expense of nutritional quality [3].

Conceptual Relationship Between Classification Systems

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship between the degree of food processing and typical nutritional quality, while acknowledging the significant variation within categories.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Nutritional Composition Across Processing Categories

Table 1: Comparative Nutritional Profiles by NOVA Category (per 100g)

| NOVA Category | Energy (kcal) | Saturated Fat (g) | Total Sugar (g) | Sodium (mg) | Dietary Fiber (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unprocessed/Minimally Processed | Variable | Variable | Variable | Variable | Variable |

| Processed Foods | Higher than Group 1 | Higher than Group 1 | Higher than Group 1 | Significantly Higher | Lower than Group 1 |

| Ultra-Processed Foods | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

Source: Adapted from [19] [20]

Research demonstrates that highly processed food purchases dominate US household purchasing patterns, supplying more than three-fourths of energy intake, with highly processed (61.0%) and moderately processed (15.9%) categories contributing the majority [19]. These categories consistently show higher saturated fat, sugar, and sodium content compared to less-processed foods [19].

A study of children's foods in Portugal found that of 244 products analyzed, 56.1% were classified as ultra-processed, 33.6% as minimally processed, and 10.2% as processed [20]. The ultra-processed category presented higher amounts of energy, sugars, saturated fat, and salt than unprocessed/minimally processed products [20].

Diet Quality and Health Outcomes

Table 2: Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Diet Quality Metrics

| Population Group | UPF Consumption Level | Healthy Eating Index (HEI) Score | AHA Diet Score | Key Nutrient Deficiencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Children (2-19 years) | Highest Quintile (>79.0% energy) | -9.96 points lower | -6.22 points lower | Higher in saturated fat, sugar, sodium; lower in fiber, protein, micronutrients |

| US Adults (≥20 years) | Highest Quintile (>70.7% energy) | Significantly lower | -12.6 points lower | Similar pattern to children, more pronounced |

Source: Adapted from [21]

Analyses of NHANES data (2015-2018) reveal that higher consumption of ultra-processed foods is strongly correlated with poorer diet quality scores in both children and adults [21]. Households purchasing the most ultra-processed foods (>67.9% energy) scored 10.7 points lower on the HEI-2015 than those purchasing the least (<48.4% energy) and showed greater deviation from Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommendations across multiple food components [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Food Product Classification Using NOVA System

Purpose: To systematically classify food products according to the NOVA system based on the nature, extent, and purpose of processing.

Materials:

- Food products with complete ingredient lists and nutritional information

- NOVA classification guidelines [3]

- Data collection form (digital or paper-based)

Procedure:

Product Identification: Record product name, brand, barcode, and manufacturer details.

Ingredient Analysis: Examine the complete ingredient list for characteristics indicative of processing level:

- Group 1 (Unprocessed/Minimally Processed): Single whole foods with no or minimal additives

- Group 2 (Culinary Ingredients): Substances derived from Group 1 foods or from nature

- Group 3 (Processed Foods): Group 1 foods with added Group 2 ingredients

- Group 4 (Ultra-Processed Foods): Formulations with multiple ingredients, including cosmetic additives and substances not commonly used in home cooking [3]

Classification Decision: Assign to appropriate NOVA category based on predetermined criteria.

Quality Control: Have a second researcher independently classify a random subset (≥10%) of products to ensure inter-rater reliability.

Applications: This protocol was implemented in a study of food pantry selections, which found that ultra-processed foods represented 41.1-43.5% of foods selected by clients, with no significant difference between intervention and control groups [8] [22].

Protocol 2: Nutritional Quality Assessment Using Nutri-Score Algorithm

Purpose: To calculate and assign Nutri-Score classifications to food products based on nutritional composition.

Materials:

- Nutritional information for food products (per 100g or 100ml)

- Nutri-Score calculation algorithm [1]

- Data collection spreadsheet

Procedure:

Data Collection: Record the following nutritional data per 100g/ml of product:

- Energy (kJ)

- Sugars (g)

- Saturated fatty acids (g)

- Sodium (mg)

- Protein (g)

- Fiber (g)

- Percentage of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes

Points Calculation:

- Calculate points A (0-10) for "negative" nutrients: energy, sugars, saturated fat, sodium

- Calculate points C (0-5) for "positive" components: protein, fiber, fruits/vegetables/nuts/legumes percentage

- Compute final score: Points A - Points C

Classification Assignment:

- A: Score ≤ -1

- B: Score 0 to 2

- C: Score 3 to 10

- D: Score 11 to 18

- E: Score ≥ 19

Validation: Cross-verify algorithm calculations with established databases where available.

Protocol 3: Integrated Assessment of Processing and Nutrition

Purpose: To simultaneously evaluate food products using both NOVA and Nutri-Score systems and analyze their concordance and discordance.

Materials:

- Food products with complete ingredient and nutrition information

- Both classification systems' guidelines

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure:

Dual Classification: Classify each product using both NOVA and Nutri-Score systems following Protocols 1 and 2.

Data Analysis:

- Create cross-tabulation of NOVA categories against Nutri-Score classes

- Calculate concordance rates (percentage of products where classifications align)

- Identify discordant cases (e.g., ultra-processed products with favorable Nutri-Scores)

Statistical Analysis:

- Use chi-square tests to examine associations between classification systems

- Calculate Cohen's kappa to measure agreement beyond chance

- Conduct regression analysis to identify nutritional predictors of discordance

Interpretation: Analyze patterns of agreement and disagreement to understand complementary insights provided by each system.

Research Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Materials for Food Classification Studies

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) | Standardized nutrient analysis | Food pantry study analysis [8] |

| Mintel Global New Products Database | Product-specific nutrition and ingredient data | Homescan Panel study product classification [19] |

| USDA FoodData Central Branded Foods | Brand-specific nutritional information | Manual classification verification [8] |

| OpenFood Facts Database | Crowdsourced product information | Ingredient list sourcing [8] |

| Nielsen Homescan Panel | Household purchase data with barcode linkage | National purchasing pattern analysis [19] |

Data Analysis and Visualization Toolkit

The following workflow diagram outlines the integrated methodological approach for comparative assessment of food classification systems:

Discussion and Research Implications

The distinction between nutritional composition and degree of processing represents a fundamental dichotomy in contemporary nutritional science. While these frameworks are often presented as competing approaches, evidence suggests they provide complementary insights for understanding diet quality and health outcomes.

Integration Frameworks

Research indicates that ultra-processed foods tend to have less favorable nutritional profiles, characterized by higher energy density and increased content of saturated fats, sugars, and sodium [19] [23]. However, significant variation exists within processing categories, suggesting that both classification systems provide valuable information. As noted in one study, "wide variation in nutrient content suggests food choices within categories may be important" [19].

Some researchers argue that "nutrient content [may be] more important than degree of processing" [21], pointing to studies showing that the association between UPF intake and adverse health outcomes may result from poor diet quality rather than processing per se. This perspective emphasizes evaluating foods like soy-based meat and dairy alternatives based on their nutritional merits rather than their processing classification [21].

Methodological Considerations

Researchers employing these classification systems should be aware of several methodological challenges:

Classification Ambiguity: Some products resist straightforward NOVA classification, requiring detailed ingredient analysis and expert judgment [8]

Algorithm Limitations: Nutri-Score's focus on specific nutrients may overlook other potentially beneficial or harmful food components [1]

Contextual Factors: The impact of processing may vary based on food matrix, preparation methods, and overall dietary patterns

Technological Evolution: Emerging processing technologies may challenge traditional classification systems, requiring ongoing methodological refinement

Future Research Directions

Priority areas for further investigation include:

- Longitudinal studies examining how reformulation affects both processing classification and nutritional profile

- Research on the biological mechanisms through which processing affects health, beyond nutrient composition

- Development of integrated classification systems that consider both processing and nutritional dimensions

- Investigation of how food processing affects sustainability metrics alongside nutritional quality

The core distinction between nutritional composition and degree of processing represents more than a methodological disagreement; it reflects fundamentally different perspectives on what constitutes a "healthy" food. The Nutri-Score system offers a practical, nutrient-based approach that enables consumers to make comparative choices at point of purchase, while the NOVA system addresses broader concerns about the transformation of food systems and the potential health implications of industrial food formulations.

For researchers engaged in local food assessment, employing both frameworks provides a more comprehensive understanding of food environments than either approach alone. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a foundation for rigorous, comparable research that can advance our understanding of how both processing methods and nutrient composition collectively influence dietary quality and health outcomes.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Approaches for Integrated Food Assessment

Front-of-pack nutrition labels have emerged as crucial public health tools for communicating nutritional information to consumers. The Nutri-Score system, adopted by several European countries, provides a simplified, color-coded assessment of the nutritional quality of food products [10]. This protocol details the operationalization of the Nutri-Score algorithm, which is derived from the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (FSA) nutrient profiling model, often referred to as "model WXYfm" [24] [10]. Understanding this algorithm is essential for researchers conducting local food assessment studies, particularly those examining the relationship between nutritional quality (as measured by Nutri-Score) and degree of food processing (as classified by the NOVA system).

Nutri-Score Algorithm Fundamentals

Core Calculation Principle

The Nutri-Score algorithm calculates a composite score based on the presence of both unfavorable components (N) that should be limited in the diet and favorable components (P) that should be promoted. The final score is determined by the equation: Nutri-Score = N points - P points [25] [10]. This score falls on a scale from -15 (most favorable) to +40 (least favorable), which corresponds to the letter grades A through E [10].

Food Categorization

The algorithm applies distinct calculation methods based on product category. Researchers must correctly classify foods into one of these categories before applying the algorithm [25]:

- General Foods (includes red meat and cheese)

- Added Fats/Oils/Nuts/Seeds

- Beverages (including milk and plant-based drinks)

Table 1: Nutri-Score Category Definitions and Examples

| Category | Definition | Examples | Special Calculation Rules |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Foods | All foods not belonging to other categories | Pasta, soups, most prepared foods | Standard algorithm applied |

| Red Meat | Foods with red meat as main ingredient (≥20% meat content) | Beef, pork, lamb, sausages, edible offal | Calculated using red meat algorithm within general foods |

| Cheese | Cheese, processed cheese, and cheese specialties | Cheddar, brie, processed cheese | Protein content always considered |

| Added Fats/Oils/Nuts/Seeds | Fats meant as ingredients | Vegetable oils, butter, nuts, seeds | Ratio of saturated fats to total fat considered |

| Beverages | All drinks, including milk and plant-based alternatives | Soft drinks, juice, plant milks, flavored waters | Distinct point allocation system |

Detailed Calculation Protocol

Unfavorable Components (N Points)

The unfavorable components are calculated based on energy density, sugar content, saturated fatty acids, and sodium/salt content per 100g or 100ml of product [24] [10].

Table 2: Point Allocation for Unfavorable Components (General Foods)

| Points | Energy (kJ/100g) | Sugars (g/100g) | Saturated Fat (g/100g) | Sodium (mg/100g) | Salt (g/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ≤335 | ≤4.5 | ≤1 | ≤90 | ≤0.225 |

| 1 | >335 | >4.5 | >1 | >90 | >0.225 |

| 2 | >670 | >9.0 | >2 | >180 | >0.45 |

| 3 | >1005 | >13.5 | >3 | >270 | >0.675 |

| 4 | >1340 | >18.0 | >4 | >360 | >0.9 |

| 5 | >1675 | >22.5 | >5 | >450 | >1.125 |

| 6 | >2010 | >27.0 | >6 | >540 | >1.35 |

| 7 | >2345 | >31.0 | >7 | >630 | >1.575 |

| 8 | >2680 | >36.0 | >8 | >720 | >1.8 |

| 9 | >3015 | >40.0 | >9 | >810 | >2.025 |

| 10 | >3350 | >45.0 | >10 | >900 | >2.25 |

Favorable Components (P Points)

The favorable components include fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, fiber, and protein content [24] [10].

Table 3: Point Allocation for Favorable Components (General Foods)

| Points | Fruits, Vegetables, Legumes, Nuts (%) | Fibre (g/100g) | Protein (g/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ≤40 | ≤0.7 | ≤1.6 |

| 1 | >40 | >0.7 | >1.6 |

| 2 | >60 | >1.4 | >3.2 |

| 3 | - | >2.1 | >4.8 |

| 4 | - | >2.8 | >6.4 |

| 5 | >80 | >3.5 | >8.0 |

Special Cases in Algorithm Application

The standard algorithm (N points - P points) applies when negative points are less than 11. For products with negative points ≥11, special rules apply [24]:

- If points for fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts = 5: FSA-score = negative points - positive points

- If points for fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts <5: FSA-score = negative points - (points FVLN + points fiber)

Experimental Protocol for Local Food Assessment

Data Collection Methodology

Materials Required:

- Food product samples with complete nutrition facts panels

- Access to product ingredient lists

- Standardized data extraction form

- Nutritional analysis software/tools (if verifying nutritional composition)

Procedure:

- Product Identification: Collect food products representative of the local food supply

- Data Extraction: Record nutritional values per 100g/ml for:

- Energy (kJ/kcal)

- Total sugars (g)

- Saturated fatty acids (g)

- Sodium (mg) or salt (g)

- Dietary fiber (g)

- Protein (g)

- Percentage of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts (%)

- Category Assignment: Classify each product into the appropriate Nutri-Score category (General Food, Beverage, etc.)

- Point Calculation: Apply the appropriate algorithm based on product category

- Score Assignment: Convert final score to letter grade (A-E)

Workflow Visualization

Category Assignment Logic

Integration with NOVA Classification in Research

Complementary Assessment Framework

While Nutri-Score evaluates nutritional composition, the NOVA system classifies foods based on processing extent and purpose [26]. For comprehensive food assessment, researchers should apply both systems in parallel:

NOVA Classification Groups:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

- Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients

- Group 3: Processed foods

- Group 4: Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) [4]

Research Implementation Protocol

- Independent Classification: Apply Nutri-Score and NOVA classifications separately to each food product

- Data Correlation: Analyze relationships between nutritional quality and processing level

- Identify Discrepancies: Note products with favorable Nutri-Score but high processing level (UPF), and vice versa

- Contextual Interpretation: Consider both dimensions when evaluating food healthfulness

Table 4: Nutri-Score and NOVA Classification Integration Matrix (Sample Data from Open Food Facts Database)

| Nutri-Score Grade | NOVA 1 (%) | NOVA 2 (%) | NOVA 3 (%) | NOVA 4 (Ultra-Processed) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Best) | 40.34 | 0.06 | 33.52 | 26.08 |

| B | 13.67 | 0.00 | 34.85 | 51.48 |

| C | 6.21 | 2.07 | 32.63 | 59.09 |

| D | 2.34 | 0.73 | 29.54 | 67.39 |

| E (Worst) | 1.23 | 1.26 | 13.82 | 83.69 |

Algorithm Updates and Considerations

2023 Algorithm Revision

The Nutri-Score algorithm was updated in 2023 to address several classification issues [25] [27]. Key improvements include:

- Enhanced distinction between whole grain and white bread products

- Better classification of vegetable oils based on fatty acid profile

- Improved scoring for red meat versus poultry

- Modified beverage categorization, including consideration of sweeteners

- Better differentiation of milk products based on saturated fat content

Impact on Ultra-Processed Food Classification

Research comparing the updated Nutri-Score with NOVA classification demonstrates improved coherence between the systems [27] [28]. The algorithm update resulted in:

- 9.8 percentage point reduction in UPFs receiving A or B ratings

- 7.8 percentage point increase in UPFs receiving D or E ratings

- Stronger alignment between poor nutritional quality and high processing level

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Nutri-Score Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Open Food Facts Database | Collaborative food product database with nutritional information | Contains Nutri-Score and NOVA classifications for thousands of products; useful for validation [26] [28] |

| National Nutrient Databases | Country-specific nutritional composition data | Essential for analyzing foods without packaging or nutrition labels |

| Codex Alimentarius | International food standards and classifications | Reference for food additive identification and classification [29] [30] |

| Nutrition Analysis Software | Tools for calculating nutritional composition | Necessary for verifying or calculating nutritional values for complex recipes |

| Standardized Data Extraction Forms | Structured templates for consistent data collection | Ensure reproducible methodology across research teams |

| Dietary Fiber Analysis Methods | AOAC methods for fiber quantification | Critical for accurate P points calculation; fiber content significantly impacts scores [25] |

This protocol provides researchers with comprehensive methodological guidance for implementing the Nutri-Score algorithm in local food assessment studies. The systematic approach to data collection, categorization, and calculation ensures consistent application across research settings. When combined with the NOVA classification system, Nutri-Score offers a multidimensional perspective on food quality that incorporates both nutritional composition and processing extent. The 2023 algorithm updates have strengthened the coherence between these systems, enabling more robust assessment of local food environments and their impact on public health.

The NOVA framework is a pioneering food classification system that categorizes edible substances based on the nature, extent, and purpose of industrial processing applied to them, rather than their nutritional composition alone [31] [15]. Developed by researchers at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, under the leadership of Carlos Augusto Monteiro, NOVA has emerged as a crucial tool for nutritional epidemiology and public health policy [3] [15]. The system identifies four distinct food groups, with its most significant contribution being the conceptualization and definition of ultra-processed foods (UPF) as a unique category with specific characteristics and health implications [3].

The fundamental thesis of NOVA is that "the most important factor now, when considering food, nutrition and public health, is not nutrients, and is not foods, so much as what is done to foodstuffs and the nutrients originally contained in them, before they are purchased and consumed" [3]. This perspective represents a paradigm shift from traditional nutrient-based approaches to one that acknowledges processing as a primary determinant of dietary quality and health outcomes. The system has been validated through numerous epidemiological studies linking UPF consumption with adverse health effects including obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, depression, and various cancers [31] [15].

The Four NOVA Categories

The NOVA system organizes all foods and food products into four groups based on the extent and purpose of processing they undergo.

Table 1: The Four NOVA Food Classification Groups

| Group | Category Name | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods | Edible parts of plants/animals with minimal industrial processing that doesn't add substances | Fresh/frozen fruits/vegetables, grains, legumes, meat, eggs, milk, natural yogurt without additives [31] [15] |

| 2 | Processed Culinary Ingredients | Substances derived from Group 1 or nature, used to prepare/cook Group 1 foods | Oils, butter, sugar, salt, honey, starches, vinegar [31] [15] |

| 3 | Processed Foods | Simple products made by adding Group 2 ingredients to Group 1 foods to enhance durability/palatability | Canned vegetables/fish, salted nuts, cured meats, cheeses, freshly baked breads [31] [15] |

| 4 | Ultra-Processed Foods | Industrial formulations with 5+ ingredients, including substances not used in culinary preparations | Mass-produced packaged snacks, sugary cereals, carbonated drinks, instant noodles, reconstituted meat products [31] [15] |

Defining Characteristics of Ultra-Processed Foods

Ultra-processed foods (UPF), classified as NOVA Group 4, are characterized by several distinctive features that differentiate them from other food categories. These products are industrial formulations typically containing five or more ingredients, often including substances not commonly used in culinary preparation [31] [15]. Formulations frequently include additives with cosmetic functions such as flavors, colorants, non-sugar sweeteners, and emulsifiers designed to imitate sensory properties of minimally processed foods or disguise undesirable qualities [31] [32].

UPFs typically contain little to no intact Group 1 foods and often include substances of no or rare culinary use, such as high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, modified starches, and protein isolates [15]. The processes employed in their creation include industrial techniques like extrusion, molding, and pre-frying [15]. These products are designed to be highly profitable (utilizing low-cost ingredients, having long shelf-life), convenient (ready-to-consume), and hyper-palatable [31] [15]. They are often aggressively marketed and presented in attractive packaging, frequently targeting children [31].

Operational Protocol for Classifying Ultra-Processed Foods

Step-by-Step Classification Methodology

The classification of food products according to NOVA requires systematic analysis of ingredients, processing methods, and product characteristics. The following protocol provides a standardized approach for researchers.

NOVA Food Classification Decision Pathway This diagram outlines the systematic decision process for categorizing foods according to the NOVA framework.

Step 1: Ingredient List Analysis

- Obtain complete ingredient list from product packaging or manufacturer specifications

- Count the total number of ingredients present

- Identify ingredients that qualify as "substances of no or rare culinary use" including:

- High-fructose corn syrup, maltodextrin, dextrose, lactose

- Hydrogenated or interesterified oils

- Modified starches

- Protein isolates (soy, whey, casein)

- Mechanically separated meat

- Identify cosmetic additives including:

- Flavors and flavor enhancers

- Colors

- Emulsifiers and emulsifying salts

- Non-sugar sweeteners