Beyond One-Size-Fits-All: Decoding Interindividual Variability in Dietary Bioactive Absorption for Precision Nutrition

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on the significant interindividual variability in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of dietary bioactive compounds.

Beyond One-Size-Fits-All: Decoding Interindividual Variability in Dietary Bioactive Absorption for Precision Nutrition

Abstract

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on the significant interindividual variability in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of dietary bioactive compounds. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biological drivers of this variability, including genetic polymorphisms, gut microbiota composition, and physiological factors. The content further examines advanced methodological approaches for assessing and addressing this heterogeneity in clinical research, discusses strategies to troubleshoot inconsistent trial outcomes, and validates the translation of this knowledge into personalized nutrition and therapeutic development. By integrating insights from recent systematic reviews and the work of consortia like COST POSITIVe, this resource provides a comprehensive framework for advancing precision nutrition and optimizing the efficacy of bioactive interventions.

The Biological Underpinnings of Variable Bioactive Responses

Defining Interindividual Variability in ADME Processes

Interindividual variability in Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) processes represents a critical determinant of efficacy and safety for pharmaceuticals and dietary bioactive compounds. This variability stems from complex interactions between genetic, physiological, and environmental factors that collectively influence how individuals process xenobiotics. Understanding these sources of variation is particularly crucial in the context of dietary bioactive absorption research, where subtle differences in compound bioavailability can significantly impact physiological responses and health outcomes. The high heterogeneity in results from nutritional intervention studies often derives from this inherent interindividual variability in (poly)phenol bioavailability, which is a main determinant of their effectiveness [1]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of the sources, assessment methodologies, and implications of ADME variability for researchers and drug development professionals.

Genetic Foundations of ADME Variability

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in Xenobiotic Metabolism

Genetic variations, particularly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), constitute a fundamental source of interindividual variability in ADME processes. These polymorphisms affect genes encoding proteins involved in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of xenobiotics, including dietary bioactive compounds [1].

Table 1: Key Genetic Polymorphisms Influencing (Poly)phenol ADME

| Gene | Gene Product | Polymorphism Impact | ADME Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| SULT | Sulfotransferases | Alters sulfation of phenolic compounds | Phase II Metabolism |

| UGT | UDP-glucuronosyltransferases | Modifies glucuronidation capacity | Phase II Metabolism |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | Affects methylation of catechol-containing phenols | Phase II Metabolism |

| CYP450 | Cytochrome P450 enzymes | Influences oxidative metabolism | Phase I Metabolism |

| Transporters | Efflux/Uptake transporters (P-gp, BCRP, OATP) | Changes cellular uptake and efflux | Absorption & Excretion |

A systematic review of the literature identified 88 SNPs in 33 genes studied for their association with variability in (poly)phenol bioavailability and metabolism. Of these genes, slightly more than half (n=17) were related to drug/xenobiotic metabolism, with the remainder associated with steroid hormone metabolism and activity. Specifically, polymorphisms were identified in genes involved in absorption (2 genes), phase I metabolism (7 genes), phase II metabolism (4 genes), and excretion (4 genes) [1]. Among genes specifically related to (poly)phenol ADME, 16 SNPs demonstrated significant modifying effects on urinary and/or plasma levels of phenolic metabolites and/or on their kinetic parameters [1].

Biochemical Pathways of (Poly)phenol Metabolism

(Poly)phenols undergo complex biotransformation that exhibits substantial interindividual variation. These compounds are often found in glycosylated forms and are partially hydrolyzed by human enzymes in the upper gastrointestinal tract, releasing aglycones that can be absorbed and conjugated by phase II enzymes in enterocytes and hepatocytes. However, most (poly)phenols are not absorbed in the small intestine and reach the colon intact, where they are extensively modified by the gut microbiota into smaller catabolites. These microbial catabolites are more easily absorbed and can be further conjugated by phase II enzymes in colonocytes and hepatocytes [1]. The molecules ultimately present in circulation are phase II metabolites of both human and microbial-human origin, which are finally excreted in urine. SNPs in genes involved in any step of this process can significantly impact the amount and type of metabolites excreted [1].

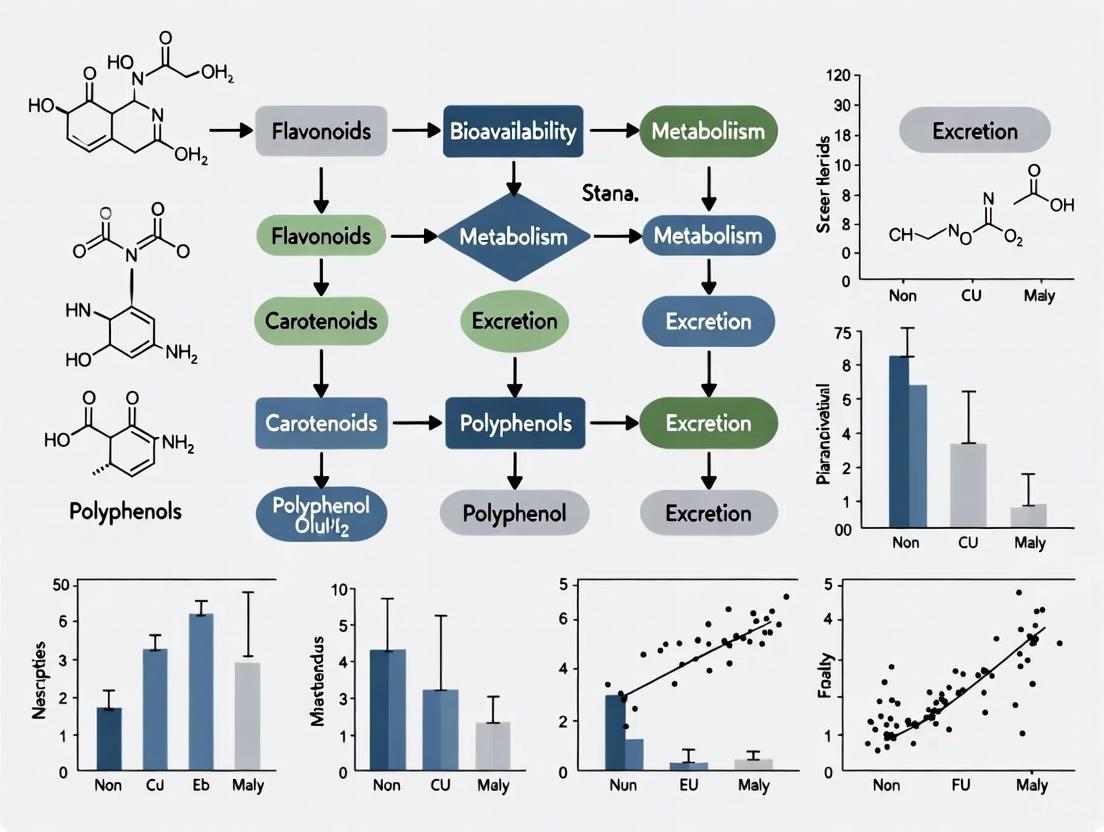

Figure 1: Metabolic Fate of Dietary (Poly)phenols and Genetic Influence Points

Methodological Approaches for Assessing ADME Variability

In Vitro ADME Assessment Techniques

In vitro ADME studies provide controlled systems for evaluating compound properties before advancing to more complex in vivo models. These assays require fewer resources and generate reproducible data for comparing ADME parameters across compounds [2] [3].

Table 2: Essential In Vitro ADME Assays for Variability Assessment

| Assay Category | Specific Assays | Parameters Measured | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | PAMPA, Caco-2, MDCKII | Permeability, Transport mechanisms | Predicting intestinal absorption |

| Distribution | Protein binding (equilibrium dialysis), Blood-to-plasma ratio | Protein binding, Tissue distribution | Estimating free drug concentration |

| Metabolism | Hepatic microsome stability, S9 fractions, Hepatocytes | Metabolic stability, Metabolite identification | Predicting clearance, metabolite profile |

| Transporter Effects | P-gp, BCRP, OATP assays | Transporter affinity, Inhibition potential | Assessing transporter-mediated interactions |

| Drug-Drug Interactions | CYP inhibition, CYP induction | Enzyme inhibition, Induction potential | Predicting metabolic interactions |

The metabolic stability assay using hepatic microsomes exemplifies a key in vitro approach. This assay uses subcellular fractions of liver (microsomes) containing drug-metabolizing enzymes including cytochrome P450s (CYPs), flavin monooxygenases, carboxylesterases, and epoxide hydrolase to investigate metabolic fate [2]. In a standard protocol, test articles are assayed in triplicate using human liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) at one concentration (typically 10 μM) at t=0 and t=60 minutes. Analysis via LC/MS/MS measures remaining parent compound at specific time points, reporting percentage metabolism of the test article, with options to determine intrinsic clearance and half-life with multiple time points [2].

Computational and QSAR Modeling Approaches

Computational models provide valuable tools for predicting ADME properties, especially during early discovery stages when compound availability is limited. These in silico methods help researchers understand how chemical structure contributes to ADME properties and enable virtual screening of compound libraries [4] [5].

Publicly available tools like SwissADME provide free access to predictive models for physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness. This web tool incorporates various predictive methods including iLOGP (a physics-based method relying on free energies of solvation), the BOILED-Egg model for predicting gastrointestinal absorption and brain access, and the Bioavailability Radar for rapid drug-likeness appraisal [4]. The platform calculates key descriptors such as molecular weight, lipophilicity (log P), polarity (TPSA), solubility, flexibility, and saturation, providing researchers with a comprehensive physicochemical profile that influences ADME behavior [4].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models have been validated for key ADME endpoints including kinetic aqueous solubility, PAMPA permeability, and rat liver microsomal stability. These models, when validated against marketed drugs, have demonstrated balanced accuracies ranging between 71% and 85%, providing important tools for the drug discovery community [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADME Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Specifications | Research Application | Variability Assessment Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes | Pooled from multiple donors, specific protein concentration | Hepatic metabolism studies | Captures interindividual metabolic variability |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Individual cytochrome P450 isoforms | Reaction phenotyping | Identifies specific metabolic pathways |

| Transfected Cell Lines | MDCKII, MDR1-MDCKII, Caco-2 | Permeability and transporter studies | Assesses transporter-based variability |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Pooled or individual donor sources | Hepatic metabolism and toxicity | Models population variability in liver function |

| ADME Predictive Software | SwissADME, ADME@NCATS | In silico property prediction | Generates hypotheses on structure-ADME relationships |

Experimental Workflow for Variability Assessment

A systematic approach to evaluating interindividual variability in ADME processes requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow outlines key methodological considerations:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for ADME Variability Assessment

Statistical Considerations and Variability Quantification

Proper characterization of variability requires appropriate statistical approaches. Variability represents the inherent heterogeneity or diversity of data in an assessment and is quantitatively described through statistical metrics such as variance, standard deviation, and interquartile ranges [6]. Techniques for addressing variability in risk assessment include:

- Disaggregating variability: Separating data into categories by factors such as sex, age, or genotype to better characterize interindividual differences [6]

- Probabilistic techniques: Using methods like Monte Carlo analysis to calculate a distribution of risk from repeated sampling of probability distributions of variables [6]

- Population pharmacokinetics: Implementing nonlinear mixed-effects models to quantify population parameters and interindividual variability

It is crucial to distinguish between variability (which cannot be reduced but can be better characterized) and uncertainty (which can be reduced with more or better data) [6]. Well-designed studies should recruit sufficiently large and diverse samples to adequately capture population variability and apply stringent statistical criteria to reach reliable conclusions [1].

Interindividual variability in ADME processes represents a critical challenge in both pharmaceutical development and dietary bioactive research. Genetic polymorphisms, particularly SNPs in genes encoding xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and transporters, significantly contribute to this variability. A systematic approach combining in silico predictions, in vitro assays, and appropriate statistical analysis provides researchers with robust methodologies to characterize and predict this variability. Understanding these sources of variation enables more effective personalization of therapeutic and nutritional interventions, ultimately improving health outcomes through tailored approaches that account for individual metabolic characteristics. Future research directions should include larger, more diverse cohort studies, advanced integrative bioinformatics approaches, and genome-wide association studies to further elucidate the complex genetic architecture underlying ADME variability.

Interindividual variability in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of dietary bioactive compounds represents a significant challenge in nutritional science and drug development. This variation often stems from genetic polymorphisms in key proteins—specifically, conjugative enzymes and membrane transporters—that govern the fate of phytochemicals and drugs within the body [7] [8]. Understanding these genetic determinants is crucial for predicting biological outcomes and personalizing nutritional and therapeutic interventions. Research indicates that factors such as gut microbiota composition, genetic background, age, and sex contribute to this variability, but genetic polymorphisms in human enzymes and transporters are among the most significant and stable influencing factors [9]. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of these polymorphisms, their functional consequences, and methodologies for their study, contextualized within the broader framework of interindividual variability research.

Key Enzymes and Transporters: Functions and Genetic Landscapes

Conjugative Enzymes

Conjugative enzymes, primarily Phase II enzymes, catalyze the conjugation of bioactive compounds with hydrophilic molecules (e.g., glucuronic acid, sulfate, glutathione), enhancing their water-solubility and facilitating excretion.

- UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs): Catalyze glucuronidation. Genetic variants in genes like UGT1A1 can significantly alter the metabolism and bioavailability of flavonoids and phenolic acids [10].

- Sulfotransferases (SULTs): Mediate sulfation. Polymorphisms in SULT1A1 have been linked to variable metabolism of compounds like resveratrol and flavonoids [10].

- Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT): Catalyzes the methylation of catechol-containing compounds. A common functional polymorphism (Val158Met) is associated with differences in the metabolism of catechins and other polyphenols [10].

- Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs): Facilitate glutathione conjugation. Null polymorphisms in GSTM1 and GSTT1, which result in a complete lack of enzyme activity, are prevalent and have been associated with interindividual differences in the metabolism of isothiocyanates from cruciferous vegetables and other phytochemicals [11].

Membrane Transporters

Membrane transporters facilitate the cellular uptake and efflux of bioactive compounds and their metabolites, critically influencing their absorption and tissue distribution.

- ABC Transporters (ATP-Binding Cassette): Function as efflux pumps. The International Transporter Consortium (ITC) highlights polymorphisms in ABCG2 (BCRP) as clinically important. The common Q141K (rs2231142) variant reduces protein expression and function, impacting the bioavailability of sulfated flavonoids and allopurinol [12].

- SLC Transporters (Solute Carrier): Mediate cellular uptake.

- SLCO1B1 (OATP1B1): Expressed in the liver, it mediates the uptake of various compounds. The Val174Ala (rs4149056) variant is a key polymorphism associated with reduced hepatic uptake of substrates, including statins and potentially ticagrelor metabolites [12].

- SLC22A1 (OCT1): A hepatic uptake transporter for organic cations. Emerging evidence indicates that polymorphisms in SLC22A1 significantly influence the disposition and effects of several drugs and, by extension, dietary cations [12].

Table 1: Key Genetic Polymorphisms in Conjugative Enzymes and Transporters

| Protein/Gene | Common Polymorphism(s) | Functional Consequence | Example Substrates Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCG2 (BCRP) | Q141K (rs2231142) | ↓ Protein expression & transport activity | Sulfated flavonoids, allopurinol [12] |

| SLCO1B1 (OATP1B1) | Val174Ala (rs4149056) | ↓ Hepatic uptake | Statins, ticagrelor metabolite [12] |

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | Multiple (e.g., R61C, M420del) | Altered transport activity & expression | Metformin, dietary cations [12] |

| COMT | Val158Met | ↓ Enzyme activity | Catechins, flavonols [10] |

| GSTM1/GSTT1 | Null alleles | Complete lack of enzyme activity | Isothiocyanates, oxidative stress products [11] |

Functional and Clinical Implications: From Metabolism to Personalized Nutrition

Genetic variation in enzymes and transporters translates directly into phenotypic differences in the ADME of bioactive compounds. This often results in distinct metabotypes—subpopulations classified based on their metabolic capacity [9] [10].

- Qualitative Metabotypes: For instance, gut microbiota metabolism of ellagitannins produces urolithins, but only a subset of the population are "producers" of specific urolithin types (e.g., Urolithin A). Similarly, only 30% of Western populations can convert soy isoflavones to equol ("equol producers") [7] [9]. While microbial-driven, these phenotypes are influenced by host genetics that shape the gut environment.

- Quantitative Metabotypes: For flavonoids like flavanones and flavan-3-ols, individuals can be stratified as "high" or "low" excretors of specific metabolites, a variation linked to polymorphisms in conjugative enzymes like UGT1A1 and SULT1A1 [9] [10].

These genetic-driven differences in internal exposure to bioactive metabolites have profound implications for health outcomes. For example, equol producers experience greater cardiometabolic benefits from soy consumption than non-producers [7]. Understanding an individual's genetic predispositions allows for a personalized nutrition approach, where dietary recommendations are tailored to one's genetic makeup to maximize health benefits and minimize adverse reactions [13] [14].

Experimental and Methodological Approaches

Deciphering the role of genetics in interindividual variability requires a multi-faceted methodological framework. The following workflow and toolkit outline standard approaches in the field.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Studying Genetic Determinants in ADME. This integrated workflow combines population phenotyping with multi-omics data collection and analysis to identify and validate genetic factors contributing to interindividual variability. WES: Whole Exome Sequencing; WGS: Whole Genome Sequencing; LC-MS: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; NMR: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; GWAS: Genome-Wide Association Study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item | Function & Application | Example Resources |

|---|---|---|

| HapMap & 1000 Genomes Data | Reference databases for allele frequency comparison across ethnicities [11]. | HapMap Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp) |

| Pharmacogenomic Databases | Curated gene-drug interactions and clinical guidelines. | CPIC (https://cpicpgx.org/), PharmGKB |

| Bioactive Compound Databases | Identify and quantify food-derived phytochemicals. | Phenol-Explorer [15] [16], FooDB [15] |

| Genotyping Assays | Interrogation of specific polymorphisms (e.g., TaqMan, SNP arrays). | Commercially available platforms (e.g., Thermo Fisher, Illumina) |

| Transfected Cell Systems | In vitro functional characterization of polymorphic transporters/enzymes. | Overexpression models (e.g., HEK293, MDCK cells) [12] |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Gold standard for sensitive quantification of metabolites and conjugates. | Triple quadrupole and high-resolution mass spectrometers |

Detailed Genotyping and Functional Characterization Protocol

A core methodology involves genotyping followed by functional validation.

Objective: To determine the functional impact of a specific polymorphism (e.g., ABCG2 Q141K) on the transport of a dietary bioactive metabolite.

Methodology:

- Genotyping: Isolate genomic DNA from participant saliva or blood samples [11]. Genotype for the target SNP (e.g., rs2231142 for ABCG2) using a validated method such as TaqMan allelic discrimination assay. PCR conditions and primer/probe sequences should be optimized and obtained from sources like dbSNP or the primary literature.

- In Vitro Transport Assay:

- Cell Model: Use polarized cell lines (e.g., MDCK-II or Caco-2) stably transfected with either the wild-type (ABCG2 p.Q141) or variant (ABCG2 p.K141) transporter cDNA [12].

- Experimental Procedure: Plate cells on transwell filters until they form a confluent monolayer. On the day of the experiment, add the compound of interest (e.g., a sulfated flavonoid) to the donor compartment (apical for efflux studies). Collect samples from the receiver compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes).

- Quantification: Analyze samples using LC-MS/MS to determine the concentration of the transported compound. Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) and efflux ratio.

- Data Analysis: Compare the efflux ratio between wild-type and variant transporter-expressing cells. A statistically significant reduction in the efflux ratio for the variant cells confirms a loss-of-function phenotype associated with the polymorphism.

Genetic polymorphisms in conjugative enzymes and transporters are fundamental drivers of interindividual variability in the ADME of dietary bioactives. A comprehensive understanding of these determinants, facilitated by the integrated experimental approaches and resources detailed herein, is critical for advancing the fields of nutrigenomics, pharmacology, and personalized medicine. Future research must prioritize large-scale studies that incorporate diverse omics platforms to fully elucidate the complex interactions between genetics, microbiome, and diet, ultimately enabling more effective and individually tailored health interventions.

The Gut Microbiome as a Central Metabolic Organ

The human gut microbiome functions as a sophisticated metabolic organ, encoding a vast repertoire of enzymes that significantly expand the host's biochemical capabilities. This complex microbial community is instrumental in the transformation of dietary components that escape host digestion into a diverse array of metabolites with local and systemic health effects. The metabolic output of the gut microbiome is not uniform; it exhibits substantial interindividual variability driven by differences in microbial composition and functional capacity, which in turn influences host responses to dietary interventions and disease susceptibility [17] [18]. Understanding the mechanisms underlying this variability is crucial for developing targeted nutritional strategies and therapeutic interventions.

The gut microbiota's metabolic prowess primarily targets two major classes of dietary compounds: fermentable fibers and polyphenols. Through fermentation processes, gut microbes generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) from dietary fibers and various phenolic acids from polyphenols [19]. These metabolites exert profound effects on host physiology, including energy regulation, immune modulation, and gut barrier integrity. Furthermore, the microbiome's role in metabolizing bioactive small molecules from the diet is a major driver of both inter- and intra-individual differences in metabolic outcomes, as highlighted by studies on coffee-derived chlorogenic acids [18]. This review explores the gut microbiome's central metabolic functions, the consequences of its metabolic output for host health, the critical challenge of interindividual variability, and the advanced methodological frameworks required for its study.

Major Metabolic Pathways and Host Interactions

Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production from Dietary Fiber

Dietary fibers are complex carbohydrates that resist host digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and reach the colon, where they serve as primary substrates for microbial fermentation. The main end products of this fermentation are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), with acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4) being the most abundant, typically produced in an approximate ratio of 3:1:1 [19]. The production of these SCFAs involves a complex network of microbial taxa with functional redundancy, where taxonomically distinct bacteria can perform similar metabolic roles.

Table 1: Major Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), Their Microbial Producers, and Host Functions

| SCFA | Key Producing Genera | Primary Host Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Most gut bacteria, including Bifidobacterium | Substrate for butyrate production via cross-feeding; cholesterol and lipogenesis precursor; immune regulation [19]. |

| Propionate | Akkermansia, Bacteroides, Dialister, Phascolarctobacterium | Gluconeogenesis substrate in liver; satiety signal; inhibits NF-κB, reducing inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17) [19]. |

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Eubacterium, Anaerostipes | Primary energy source for colonocytes (provides 70% of their energy); promotes gut barrier integrity via tight junction assembly; HDAC inhibitor; induces regulatory T-cells [19]. |

SCFAs mediate their effects through multiple mechanisms: serving as signaling molecules via G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) such as GPR41 and GPR43, inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDAC), and serving as energy sources [19]. Butyrate is particularly crucial for colonic health, as it provides the main energy source for colonocytes, facilitates tight junction assembly, and exhibits potent anti-inflammatory effects through NF-κB inhibition and HDAC activity [19]. Cross-feeding interactions between microbial species are fundamental to efficient SCFA production; for instance, acetate produced by Bifidobacterium can enhance butyrate production by Faecalibacterium [19].

Figure 1: Microbial Fermentation of Dietary Fiber to SCFAs and Resulting Host Effects. SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) are produced through microbial fermentation of dietary fiber, leading to diverse host physiological effects through multiple interconnected pathways.

Bioactivation of Dietary Polyphenols

Dietary polyphenols, abundant in plant-based foods, undergo extensive microbial transformation in the gut, which significantly enhances their bioavailability and biological activity. Many polyphenols are poorly absorbed in their native forms; their bioactivation relies heavily on microbial metabolism involving hydrolysis, ring cleavage, decarboxylation, and dehydroxylation reactions [18]. This process exemplifies the gut microbiome's role as a central metabolic organ, converting complex dietary constituents into bioactive metabolites.

A prime example is the metabolism of chlorogenic acids from coffee. Upon consumption, these compounds can be hydrolyzed in the small intestine to release free phenolic acids like caffeic acid and ferulic acid, which are then absorbed and undergo host conjugation (sulfation, glucuronidation, glycination) [18]. However, a substantial portion reaches the colon, where gut microbiota transform them into metabolites such as dihydrocaffeic acid (DHCA), dihydroferulic acid (DHFA), and vanillic acid [18]. These microbially derived metabolites exhibit enhanced absorption and distinct biological activities compared to their parent compounds.

The interindividual variation in the production of these metabolites is striking. Studies quantifying key urinary coffee phenolic acid metabolites have observed the highest inter- and intra-individual variation for metabolites produced by the colonic microbiome, highlighting the gut microbiota as the main driver of metabolic variability [18]. Notably, the specific metabolic pathway taken has implications for host physiology; for instance, urinary ferulic acid-4′-sulfate, a metabolite not requiring microbial action, was strongly correlated with fasting insulin, whereas microbially derived sulfate metabolites correlated with plasma cysteinylglycine levels [18].

Interindividual Variability and Methodological Challenges

Interindividual variability in gut microbiome composition and function poses a significant challenge for predicting host responses to dietary interventions and for developing personalized nutritional strategies. This variability stems from multiple factors:

- Microbial Community Composition: The presence or absence of specific bacterial taxa and strains with the requisite enzymatic capabilities for substrate metabolism varies between individuals [17]. This functional redundancy and specificity directly impact the metabolic output from dietary inputs.

- Gut Microbiome as a Variability Driver: Research has conclusively shown that the gut microbiome is the primary driver of both inter- and intra-individual differences in the metabolism of dietary bioactive small molecules. For example, in a study on coffee consumption, metabolites requiring microbial transformation showed substantially higher variation than those produced solely by host metabolism [18].

- Habitual Dietary Intake: Long-term dietary patterns shape the gut microbial ecosystem, selecting for communities that are more efficient at processing frequently consumed substrates. This baseline configuration influences the response to new dietary interventions [17].

- Technical and Analytical Limitations: The inherent limitations of common microbiome analysis methods, including their compositional nature and high variability, can obscure true biological signals and contribute to inconsistent findings across studies [20].

This variability has direct implications for the efficacy of dietary interventions and the interpretation of research findings. The perceived success or failure of an intervention may depend as much on the baseline microbiome of the individual as on the intervention itself [17].

Quantitative Methodologies for Microbiome Analysis

Accurate quantification of microbial abundance is fundamental to understanding its metabolic function. Traditional 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics provide relative abundances, where the proportion of one taxon depends on the abundances of all others, making it difficult to discern true changes in microbial loads [21]. This compositional nature of microbiome data is a major challenge, as an increase in the relative abundance of a taxon could mean it actually increased, or that other taxa decreased [21].

To overcome these limitations, researchers are developing absolute quantification frameworks:

- Digital PCR (dPCR) Anchoring: This method involves using dPCR to precisely count the number of 16S rRNA gene copies in a sample. This absolute count then serves as an "anchor" to convert relative abundances from sequencing into absolute quantities [21]. dPCR is highly sensitive and does not require a standard curve, as it relies on partitioning a sample into thousands of nanoliter-scale reactions and counting positive amplifications [22] [21].

- Strain-Specific Quantitative PCR (qPCR): For targeting specific bacterial strains, such as probiotics, qPCR with strain-specific primers offers high accuracy and sensitivity. A validated protocol for this approach can achieve a detection limit of around 10³ cells per gram of feces, providing a broader dynamic range and lower limit of detection compared to next-generation sequencing methods [22].

- Spiked Standards: Adding known quantities of exogenous DNA from an organism not present in the sample prior to DNA extraction allows for the calculation of absolute microbial loads based on the ratio of endogenous to spiked DNA recovered after sequencing [21].

Figure 2: Absolute Quantification Workflow Using dPCR Anchoring. Combining dPCR-based total bacterial load measurement with relative abundance data from sequencing allows for the calculation of absolute abundances, enabling accurate assessment of taxonomic changes.

Table 2: Comparison of Microbial Quantification Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing of a taxonomic marker gene. | Community-wide profiling; identifies unculturable taxa; cost-effective for large studies. | Data is relative and compositional; cannot determine direction/magnitude of change without anchoring [21]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | Sequencing all DNA in a sample. | Strain-level resolution; functional gene profiling. | Data is relative and compositional; computationally intensive; high host DNA can be problematic in mucosal samples [21]. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Target-specific amplification with a standard curve. | Absolute quantification of specific taxa; high sensitivity (~10³ cells/g); cheaper and faster than dPCR for specific targets [22]. | Requires strain-specific primers; limited to targeted taxa; potentially affected by PCR inhibitors. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (dPCR) | Partitioning of sample into thousands of nano-droplets for absolute counting. | Absolute quantification without standard curve; high precision; resistant to PCR inhibitors [22] [21]. | More expensive and slower than qPCR for strain quantification; narrower dynamic range than qPCR [22]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Gut Microbiome Metabolic Research

| Reagent / Method | Function/Description | Application in Metabolic Research |

|---|---|---|

| Kit-Based DNA Isolation (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) | Efficient and standardized isolation of microbial DNA from complex fecal or mucosal samples. | Provides high-quality DNA for downstream qPCR, dPCR, and sequencing; critical for achieving accurate and reproducible quantification of microbial loads and taxa [22]. |

| Strain-Specific PCR Primers | Oligonucleotides designed to uniquely target a specific bacterial strain based on its genome sequence. | Enables precise quantification of probiotic or live biotherapeutic strains in fecal samples after intervention, crucial for tracking colonization and metabolic contribution [22]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Reagents | Reagents for microfluidic-based absolute quantification of target genes (e.g., total 16S rRNA gene). | Used as an "anchor" to convert relative sequencing data to absolute abundances, allowing accurate assessment of total microbial load and taxon-specific changes in response to diet [21]. |

| Spike-in DNA Standards | Known quantities of exogenous DNA (e.g., from a non-native organism) added to the sample pre-extraction. | Serves as an internal standard to control for technical variation during DNA extraction and library preparation, enabling absolute quantification in metagenomic sequencing [21]. |

| Anaerobic Culture Media (e.g., MRS Broth) | Nutrient media for the growth and maintenance of oxygen-sensitive gut bacteria. | Used to cultivate and harvest specific bacterial strains (e.g., Limosilactobacillus reuteri) for spiking experiments to validate quantification methods or study their metabolism in vitro [22]. |

| LC-MS/MS Standards | Isotope-labeled or pure chemical standards for targeted metabolomics. | Quantitative measurement of microbial metabolites (SCFAs, phenolic acids, BCFAs) in fecal, blood, or urine samples to link microbial metabolic activity to host outcomes [18]. |

The gut microbiome rightfully claims its role as a central metabolic organ, responsible for biotransforming dietary components into a myriad of signaling molecules and metabolites that profoundly influence host physiology. Its metabolic functions, particularly SCFA production from fibers and the bioactivation of polyphenols, are integral to maintaining metabolic, immune, and gut barrier homeostasis. However, the significant interindividual variability in the composition and function of this microbial community presents both a challenge and an opportunity. It complicates the prediction of dietary intervention outcomes but also opens the door to truly personalized nutrition strategies. Advancing our understanding in this field requires a concerted move away from purely relative microbial profiling toward absolute quantification methodologies that can accurately capture changes in microbial loads. Integrating robust quantitative microbial data with detailed metabolomic profiles from well-designed human interventions will be essential to unravel the complex, individual-specific interactions between diet, gut microbes, and host health, ultimately harnessing the gut microbiome's metabolic potential for preventive and therapeutic applications.

Interindividual variability in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of dietary bioactives represents a significant challenge in nutritional science and drug development. This variation, observed even in highly controlled clinical trials, often distinguishes "responders" from "non-responders" and can determine the success or failure of nutritional interventions [10]. Understanding the factors driving this heterogeneity is crucial for developing personalized nutrition strategies and improving the efficacy of bioactive compounds.

The physiological journey of a bioactive compound from consumption to systemic circulation is complex, governed by multiple processes collectively known as LADME (liberation, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination) [23]. Each step presents an opportunity for interindividual variation, which can be influenced by a combination of modifiable and non-modifiable factors. This technical guide examines the core determinants of this variability, focusing on age, sex, health status, and lifestyle factors, with particular emphasis on their mechanisms and implications for research and development.

Non-Modifiable Factors

Genetic Background

Genetic polymorphisms significantly influence the metabolism and bioavailability of dietary bioactives, primarily through variations in genes encoding metabolic enzymes and transporters.

Key Mechanisms:

- Enzyme Polymorphisms: Genetic variations in phase II conjugating enzymes such as UGT (UDP-glucuronosyltransferases), SULT (sulfotransferases), and COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) affect the conjugation and elimination of polyphenols [10]. These polymorphisms create distinct metabolic phenotypes that determine circulating metabolite profiles and potential bioactivity.

- Transporter Variations: Genetic differences in membrane transporters (e.g., ABC transporters, OATP) influence the absorption and tissue distribution of bioactive compounds and their metabolites [10].

Research Implications: Stratified randomization based on genetic profiles ensures balanced distribution of metabolic capacities across study arms, enabling clearer identification of responsive subgroups [10].

Table 1: Genetic Factors Influencing Bioactive Compound Metabolism

| Genetic Factor | Target Bioactives | Impact on ADME | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| UGT polymorphisms | Flavonoids, phenolic acids | Altered glucuronidation rates | Affects systemic exposure and elimination half-life |

| COMT variants | Catechol-containing polyphenols | Modified methylation patterns | Influences metabolite bioactivity and excretion |

| ABC transporter polymorphisms | Various polyphenols | Modified cellular efflux | Alters tissue distribution and bioavailability |

| Gut microbiota composition genes | Ellagitannins, isoflavones | Qualitative production of microbial metabolites | Determines equol, urolithin production capability |

Age

Age-related physiological changes systematically alter the absorption and metabolism of dietary bioactives through multiple mechanisms.

Key Mechanisms:

- Gastrointestinal Changes: Reduced gastric acid secretion, altered intestinal permeability, and decreased gastrointestinal blood flow can modify the liberation and absorption of compounds from the food matrix [9].

- Metabolic Capacity: Age-associated declines in hepatic and renal function may reduce first-pass metabolism and elimination of bioactive compounds [9].

- Body Composition: Changes in body fat percentage and lean mass that occur with aging can influence the volume of distribution for lipophilic and hydrophilic compounds.

Research Evidence: While the POSITIVe network analysis identified age as a potential determinant of variability, information remains limited compared to other factors [10]. The systematic review by [9] confirmed age as a relevant factor for interindividual differences in the ADME of certain (poly)phenols, though the specific effects vary by compound class.

Sex

Sex-based differences in the processing of dietary bioactives arise from hormonal, physiological, and body composition variations.

Key Mechanisms:

- Hormonal Influences: Sex hormones regulate the expression and activity of various drug-metabolizing enzymes, creating distinct metabolic environments in males and females [9].

- Body Composition: Differences in fat distribution and lean body mass between sexes can affect the distribution and accumulation of lipophilic bioactive compounds.

- Gastrointestinal Physiology: Variations in gastric emptying time and gastrointestinal transit between sexes may influence absorption kinetics.

Research Evidence: The POSITIVe network highlighted vascular responses to polyphenols that varied across study populations depending on sex [10]. However, the systematic analysis noted that information on sex as a determinant of variability remains limited and requires further investigation [10] [9].

Modifiable Factors

Gut Microbiota Composition and Function

The gut microbiota represents perhaps the most significant modifiable factor influencing interindividual variation in dietary bioactive metabolism, particularly for polyphenols.

Key Mechanisms:

- Metabolic Transformation: Gut microbiota convert parent polyphenols into biologically active metabolites (e.g., conversion of daidzein to equol, ellagitannins to urolithins) [10] [9].

- Bioactivation: Many dietary polyphenols undergo minimal absorption in the small intestine and reach the colon where microbial enzymes hydrolyze glycosides to aglycones, enhancing absorption [24].

- Individual Phenotypes: Interindividual differences in gut microbiota composition result in distinct metabotypes, categorized as "producers" versus "non-producers" of specific bioactive metabolites [9].

Research Implications: Metabotyping individuals based on their microbial metabolic capabilities provides a practical approach to stratify study populations and predict responsiveness to specific dietary bioactives [10].

Table 2: Gut Microbiol-Dependent Metabotypes for Selected Bioactives

| Bioactive Compound | Metabotype Categories | Key Microbial Metabolites | Health Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflavones (e.g., Daidzein) | Equol producers vs. non-producers | Equol | Enhanced estrogenic/anti-estrogenic activity |

| Ellagitannins | Urolithin producers (A, B), non-producers | Urolithin A, B | Varied anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects |

| Flavan-3-ols | Quali-quantitative metabotypes | γ-Valerolactones, phenyl-γ-valerolactones | Differential cardiometabolic benefits |

| Resveratrol | Lunularin producers vs. non-producers | Lunularin | Altered bioactive potential |

Health Status

Baseline health status, particularly cardiometabolic parameters, significantly influences responsiveness to dietary bioactives.

Key Mechanisms:

- Metabolic Dysregulation: Conditions such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension create physiological environments that may enhance sensitivity to certain bioactive interventions [10] [25].

- Inflammatory Status: Chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome may modulate cellular responsiveness to anti-inflammatory bioactives.

- Endothelial Function: The degree of endothelial dysfunction at baseline influences the potential for improvement following polyphenol intervention [10].

Research Evidence: Overweight individuals or those with cardiovascular risk factors appear to respond more consistently to polyphenol interventions, though findings are inconsistent across polyphenol types and health outcomes [10]. Individuals with metabolically unhealthy phenotypes, regardless of BMI, may demonstrate different responses compared to their metabolically healthy counterparts [25].

Lifestyle Factors

Dietary Patterns

Overall dietary context modulates the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of specific bioactive compounds through multiple mechanisms.

Key Mechanisms:

- Food Matrix Effects: The liberation of bioactives from their food matrix during digestion determines bioaccessibility [23] [26]. Processing methods (e.g., cooking, fermentation) can enhance or impair this release.

- Nutrient Interactions: Co-consumed nutrients can act as absorption enhancers or inhibitors. Dietary fat improves absorption of lipophilic compounds, while dietary fiber may bind certain bioactives, reducing their bioavailability [23].

- Meal Composition: The macronutrient profile of a meal influences gastrointestinal processing time, pH, and enzymatic activity, collectively affecting bioactive compound liberation and absorption.

Research Evidence: In vitro digestion models demonstrate significant variability in bioactive compound bioaccessibility depending on the food matrix and dietary context [26] [27]. For instance, the bioaccessibility of galangin from Alpinia officinarum ranged from 17.36% to 36.13% across different dietary models [26].

Physical Activity

Regular physical activity modulates metabolic health and may influence the absorption and efficacy of dietary bioactives.

Key Mechanisms:

- Gastrointestinal Motility: Exercise affects gastrointestinal transit time, potentially altering the absorption kinetics of bioactive compounds.

- Metabolic Flexibility: Physical activity enhances insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function, potentially creating a more responsive physiological environment to certain bioactive interventions [25].

- Tissue Perfusion: Exercise-induced improvements in cardiovascular function and tissue blood flow may enhance distribution of bioactive compounds to target tissues.

Research Evidence: The systematic review by [9] identified physical activity as one of the factors driving interindividual variability in the metabolism and bioavailability of (poly)phenolic metabolites, though specific mechanisms remain less characterized compared to other factors.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Variability

Data-Driven Methods

Comprehensive Baseline Assessment: Detailed characterization of study participants at baseline provides essential context for interpreting individual responses. Key parameters include genetics, gut microbiota composition, health status, and lifestyle factors [10].

Metabotyping: Categorizing individuals into metabolic phenotypes based on their capacity to metabolize specific bioactive compounds. This approach moves beyond simple "producer" versus "non-producer" dichotomies to capture the spectrum of metabolic capabilities [10] [9].

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and metagenomics provides comprehensive insights into the factors driving interindividual variability [10]. Advanced computational methods, including machine learning and big data analytics, are essential for analyzing these complex datasets and identifying response patterns.

Enhanced Experimental Designs

Stratified Randomization: Distributing participants across study arms based on key variables likely to influence bioactive metabolism (e.g., genetic polymorphisms, gut microbiota composition) [10]. This approach minimizes variability and facilitates identification of responsive subgroups.

Crossover Designs: Having participants serve as their own control reduces between-subject variability and clarifies intervention-specific effects, particularly valuable for acute or short-term studies [10].

N-of-1 Trials: Highly personalized approach assessing effects of interventions on individual participants over multiple intervention and control periods [10]. This method captures unique response variations often masked in group-based designs and supports personalized nutrition approaches.

Adaptive Trial Designs: Modifying study protocols during the trial based on interim data analyses without compromising validity [10]. Adaptations may include participant stratification based on early response patterns, dosage adjustments, or modification of outcome measures.

Methodological Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methods for Investigating Interindividual Variability

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| In vitro digestion models | Simulate gastrointestinal conditions to assess bioaccessibility | Static vs. dynamic systems; incorporation of dialysis membranes for absorption simulation [26] [27] |

| Caco-2 cell lines | Model intestinal epithelium for absorption studies | Standardized for permeability assessment; often coupled with digestion models [27] |

| TIM systems | Computer-controlled dynamic gastrointestinal models | Superior physiological mimicry; adjustable parameters per research needs [26] |

| Mass spectrometry | Metabolomic profiling; quantification of metabolites | High-resolution assessment; requires standardized workflows for comparability [10] |

| DNA sequencing | Genetic polymorphism identification; microbiome composition | Targeted (specific genes) vs. untargeted (metagenomics) approaches [10] |

| Challenge tests | Standardized polyphenol supplements for metabotyping | Enables comparison across individuals and studies [10] |

Analytical Workflow Visualization

Research Workflow for Variability Analysis

Factors Influencing Bioavailability Pathway

Bioavailability Pathway and Influencing Factors

The interindividual variability in response to dietary bioactives is influenced by a complex interplay of modifiable and non-modifiable factors. Non-modifiable factors such as genetics, age, and sex create a baseline metabolic phenotype, while modifiable factors including gut microbiota composition, health status, and lifestyle elements provide opportunities for intervention and personalization.

Understanding these factors and their interactions requires sophisticated research approaches that integrate comprehensive baseline characterization, advanced metabotyping, multi-omics technologies, and innovative study designs. The future of dietary bioactive research lies in moving beyond one-size-fits-all recommendations toward personalized nutrition strategies that account for individual metabolic capacities and physiological contexts.

This approach has significant implications for drug development, where understanding the factors influencing bioactive absorption and metabolism can inform the development of nutraceuticals and enhance the efficacy of pharmaceutical interventions that interact with dietary components. As research in this field advances, the integration of these factors into clinical trial design and nutritional recommendations will be essential for maximizing the health benefits of dietary bioactives across diverse populations.

The study of dietary bioactives has moved beyond mere nutrient absorption to encompass the complex metabolic interplay between host physiology and the gut microbiome. A central thesis in this field is the profound interindividual variability in the production and subsequent bioavailability of metabolites derived from dietary precursors. This variability often dictates the efficacy of dietary interventions and confounds clinical trial outcomes. The production of equol from daidzein, urolithins from ellagitannins, and enterolactone from lignans serves as a quintessential model for this phenomenon. This whitepaper provides a technical deep-dive into these three case studies, summarizing key quantitative data, detailing experimental protocols, and visualizing critical pathways to equip researchers with the tools to dissect this metabolic heterogeneity.

Case Study 1: Equol Production from Soy Isoflavones

Soy isoflavones, primarily daidzein, are metabolized by specific gut bacteria to produce equol, a metabolite with significantly higher estrogenic and antioxidant activity than its precursor.

2.1 Key Quantitative Data

Table 1: Comparative Metrics for Equol Producers vs. Non-Producers

| Metric | Equol Producers | Non-Producers | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 25-30% (Western) | 70-75% (Western) | Prevalence is higher (>50%) in Asian populations. |

| Plasma [Equol] | 10-1000 nM | < 40 nM | Post-soy challenge; highly variable among producers. |

| Bioactivity (ERβ) | ~100x Daidzein | N/A | Equol has a high affinity for Estrogen Receptor Beta. |

| Key Bacterial Taxa | Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, Slackia isoflavoniconvertens, Eggerthella sp. YY7918 | Lacking or low abundance of equol-producing genes. | Presence of the tda gene cluster is a key determinant. |

2.2 Experimental Protocol: Identification of Equol Producers via UPLC-MS/MS

Objective: To quantify daidzein and equol in human urine or plasma to classify subjects as equol producers or non-producers. Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Collect 24-hour urine or fasting plasma samples before and 8-24 hours after a standardized soy challenge (e.g., 1 serving of soy milk).

- Sample Preparation:

- Enzymatic Deconjugation: Incubate sample with β-glucuronidase/sulfatase (from Helix pomatia) in sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 37°C for 2-4 hours to hydrolyze glucuronide and sulfate conjugates.

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction: Add ethyl acetate, vortex, and centrifuge. Transfer the organic layer and evaporate to dryness under nitrogen.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the residue in methanol/water for analysis.

- UPLC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Column: C18 reverse-phase (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm).

- Mobile Phase: A) 0.1% Formic acid in water, B) 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile. Gradient elution.

- Mass Spectrometer: Triple quadrupole in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode.

- MRM Transitions: Daidzein: 253→132, 253→224; Equol: 241→121, 241→148; D4-Equol (internal standard): 245→125.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the equol-to-daidzein ratio. A common classification threshold is a log10(equol:daidzein) ratio > -1.75 in urine.

Diagram 1: Equol Producer Identification Workflow

Case Study 2: Urolithin Production from Ellagitannins

Ellagitannins and ellagic acid from pomegranates, berries, and nuts are metabolized to a series of urolithins (Uro-A, -B, -C, -D, etc.) via the gut microbiome. Individuals are stratified into three distinct metabotypes.

3.1 Key Quantitative Data

Table 2: Urolithin Metabotypes (UMs)

| Metabotype | Phenotype | Key Urolithins Detected | Estimated Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| UM-A | No/Weak Producers | None or only Uro-C & IsoUro-A | 10-15% |

| UM-B | Intermediate Producers | Uro-A & Uro-B (but not Uro-D) | 65-80% |

| UM-C | Extensive Producers | Uro-A, Uro-B, and Uro-D | 5-25% |

Table 3: Bioactivity of Urolithin A

| Pathway/Process | Effect | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Mitophagy | Inducer | Activates PINK1-Parkin pathway; promotes mitochondrial autophagy. |

| Anti-inflammatory | Suppressor | Inhibits NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. |

| Muscle Function | Enhancer | Improves mitochondrial function and reduces sarcopenia in aged models. |

3.2 Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Gut Model Fermentation

Objective: To simulate the human gut environment and assess an individual's urolithin-production capacity from a standardized ellagitannin source. Workflow:

- Inoculum Preparation: Collect fresh fecal sample from donor in an anaerobic chamber. Homogenize in pre-reduced phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Fermentation Setup:

- Use a bioreactor containing a complex, pre-reduced culture medium (e.g., YCFA).

- Inoculate with 10% (w/v) fecal slurry.

- Add a purified ellagitannin or pomegranate extract (e.g., 100 µg/mL) as the substrate.

- Maintain anaerobiosis (with N2/CO2), pH (~6.8), and temperature (37°C) with continuous stirring.

- Sampling: Collect samples at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours.

- Analysis:

- Centrifuge samples to remove bacteria.

- Analyze supernatant using UPLC-MS/MS for urolithin profiling (Uro-A, -B, -C, -D, IsoUro-A).

- Metabotype assignment is based on the final urolithin profile at 48 hours.

Diagram 2: Urolithin Biosynthetic Pathway

Case Study 3: Enterolactone Production from Dietary Lignans

Dietary lignans (secoisolariciresinol diglucoside - SDG, matairesinol) are converted by the gut microbiota to the enterolignans enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL), with ENL being the more stable and bioactive end-product.

4.1 Key Quantitative Data

Table 4: Factors Influencing Enterolactone Concentration

| Factor | Impact on Plasma [ENL] | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Use | Drastic decrease (>90%) | Recovery can take weeks to months. |

| Diet (Lignan-rich) | Moderate increase | Flaxseed is the richest source of SDG. |

| Gut Microbiota | High interindividual variability | Key bacteria: Eggerthella lenta, Blautia producta, Lactonifactor longoviformis. |

| Smoking | Decrease | Associated with lower ENL levels. |

4.2 Experimental Protocol: 16S rRNA Sequencing & Metagenomic Analysis for Predictive Profiling

Objective: To correlate gut microbial community structure with enterolignan production capacity. Workflow:

- Phenotyping: Determine subjects' ENL production phenotype via UPLC-MS/MS of urine/plasma after a flaxseed challenge (as per Equol protocol).

- DNA Extraction: Extract total genomic DNA from fecal samples using a dedicated kit (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit) with bead-beating for cell lysis.

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification & Sequencing:

- Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable region with primers 341F and 805R.

- Perform sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2x250 bp).

- Bioinformatics:

- Process sequences using QIIME 2 or Mothur.

- Cluster sequences into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs).

- Assign taxonomy using a reference database (e.g., SILVA or Greengenes).

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use linear models (e.g., MaAsLin2) or machine learning (Random Forest) to identify ASVs significantly associated with high ENL producer status.

Diagram 3: Microbiome Analysis for ENL Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 5: Key Reagents for Studying Microbial Metabolites of Polyphenols

| Item | Function & Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| β-Glucuronidase/Sulfatase | Enzymatic deconjugation of phase II metabolites in biofluids prior to LC-MS analysis for quantification of aglycones. | Helix pomatia Type H-2 |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for absolute quantification via LC-MS/MS, correcting for matrix effects and recovery losses. | D4-Equol, 13C3-Enterolactone |

| Anaerobic Chamber/Workstation | Creates an oxygen-free environment for culturing strict anaerobic gut bacteria and setting up in vitro fermentations. | Coy Laboratory Products |

| Pre-reduced Media | Culture media deoxygenated and supplemented with reducing agents (e.g., cysteine, Na2S) to support anaerobic growth. | YCFA, M2GSC, BHI + Resazurin |

| UPLC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity, high-resolution quantification and identification of metabolites and their isomers in complex mixtures. | Waters ACQUITY UPLC & Xevo TQ-S |

| DNA Extraction Kit (Stool) | Standardized, bead-beating-based kits for efficient lysis of diverse microbial cells and isolation of high-quality DNA. | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit |

Diagram 4: ENL Signaling via ER and NRF2

Advanced Research Designs and Omics Technologies for Variability Mapping

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for implementing data-driven characterization in research investigating interindividual variability in dietary bioactive absorption. We detail rigorous methodologies for baseline assessment and metabotyping that enable researchers to stratify populations based on their capacity to metabolize specific bioactive compounds. The protocols and analytical approaches presented here facilitate the move from one-size-fits-all nutrition recommendations toward precision nutrition strategies that account for substantial interindividual differences in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of plant bioactives. By establishing standardized procedures for capturing key determinants of variability, this guide aims to enhance methodological consistency across studies and accelerate the development of targeted dietary interventions.

Interindividual variability in response to dietary bioactives represents a significant challenge in nutritional research and therapeutic development. Despite consistent dietary interventions, substantial differences in physiological responses and health outcomes are routinely observed across individuals [28]. This variability predominantly originates from differences in the ADME of bioactive compounds, which are modulated by factors including genetic polymorphisms, gut microbiota composition, age, sex, dietary habits, health status, and medication use [9] [28].

The concept of metabotyping has emerged as a crucial strategy to categorize individuals based on their metabolic capabilities, particularly their capacity to produce specific gut microbial metabolites from dietary precursors [29]. Well-established metabotypes include equol producers (EP) versus non-producers (ENP) from isoflavone metabolism, urolithin metabotypes (UM-A, UM-B, UM-0) from ellagitannin metabolism, and lunularin producers (LP) versus non-producers (LNP) from resveratrol metabolism [29] [9]. These metabotypes demonstrate qualitative metabolic differences that significantly influence the biological effects of dietary interventions.

This guide provides comprehensive methodological approaches for characterizing research participants through systematic baseline assessment and metabotyping protocols, enabling researchers to account for key sources of variability in study design and analysis.

Comprehensive Baseline Assessment Framework

Core Demographic and Anthropometric Measures

A comprehensive baseline assessment should capture fundamental demographic, clinical, and lifestyle factors that influence bioactive metabolism. The minimum dataset should include:

- Basic Demographics: Age, sex, ethnicity, and menopausal status for female participants [29] [28]

- Anthropometric Measurements: Body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body composition via bioelectrical impedance analysis or DEXA [25] [30]

- Health Status: Comorbidities, medication use, and specific health conditions that may affect metabolism or eligibility [31] [30]

Standardized protocols for data collection are essential, including calibrated instruments for anthropometrics and validated questionnaires for demographic and health information.

Dietary and Lifestyle Assessment

Dietary quality and lifestyle factors significantly influence baseline metabolic status and intervention responses:

- Dietary Patterns: Assess using validated instruments like the 14-item Taiwanese Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (T-MEDAS) or similar tools appropriate to the population [30]

- Dietary Behaviors: Document frequent night meals, prolonged sedentary time, meals eaten outside home, sweet consumption frequency, and fried food preference [30]

- Lifestyle Factors: Physical activity levels, smoking status, and alcohol consumption [30]

These factors should be captured using standardized questionnaires administered at baseline, with attention to validation for the specific population under study.

Biological Sample Collection and Biobanking

Systematic collection and preservation of biological samples enables comprehensive metabolic profiling:

Table 1: Biological Samples for Baseline Assessment

| Sample Type | Analytes | Processing Method | Storage Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | DNA, serum metabolites, clinical biomarkers (glucose, lipids, inflammatory markers) | Fasting collection, centrifugation | -80°C |

| Urine | Phenolic metabolites, organic acids | 24-hour or first-morning void, aliquoting | -80°C |

| Feces | Gut microbiota composition, microbial metabolites | Immediate freezing or stabilization buffer | -80°C |

Standard operating procedures should be established for sample collection, processing, and storage to maintain sample integrity and analytical reproducibility.

Metabotyping Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Challenge Tests for Metabotype Determination

Metabotype determination requires controlled exposure to specific bioactive compounds followed by monitoring of metabolite production:

Protocol for Polyphenol Metabotype Determination

Principle: Administer standardized polyphenol mixture and quantify microbial metabolite production in urine [29].

Materials:

- Polyphenol-rich supplement (PPs) containing resveratrol (50 mg), pomegranate extract (400 mg rich in ellagitannins and ellagic acid), and red clover extract (250 mg containing 20% isoflavones) [29]

- Control placebo matched in appearance

- UPLC-QTOF-MS system for metabolite quantification

- Authentic standards: urolithins (A, B, isourolithin A), equol, O-desmethylangolensin (ODMA), lunularin, and their phase II metabolites [29]

Procedure:

- Baseline urine collection after 3-day polyphenol restriction

- Administer PPs for 3 consecutive days

- Collect 24-hour urine on day 3 of intervention

- Sample processing: dilute urine 1:1 with methanol:water (1:1, v/v) containing internal standard, centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 min

- UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis with HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm), 0.3 mL/min flow rate, 5 μL injection volume

- Gradient elution with water:formic acid (99.9:0.1, v/v) and acetonitrile:formic acid (99.9:0.1, v/v)

- Metabotype classification based on established urinary metabolite thresholds [29]

Classification Criteria:

- Urolithin metabotypes: UM-A (urolithin A producers), UM-B (urolithin A, isourolithin A, and urolithin B producers), UM-0 (non-producers) [29]

- Equol producers: Urinary equol >1000 nmol/24h or log10(equol:daidzein) >-1.75 [9]

- Lunularin producers: Detection of lunularin and/or 4-hydroxydibenzyl above threshold levels [29]

Genotyping Approaches

Genetic variants in enzymes and transporters involved in bioactive compound metabolism contribute significantly to interindividual variability:

Table 2: Key Genetic Variants for Bioactive Compound Metabolism

| Bioactive Class | Gene | Protein Function | Impact on ADME |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | BCO1/2 | Carotenoid cleavage enzymes | Altered conversion to retinol |

| Carotenoids | SCARB1, CD36 | Cholesterol transporters | Modified absorption efficiency |

| Isoflavones | UGT1A, SULT1A | Phase II conjugation enzymes | Varied conjugation patterns |

| Ellagitannins | GST, UGT | Detoxification enzymes | Altered urolithin conjugation |

| Flavanones | COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase | Modified hesperetin methylation |

Methodology:

- DNA extraction from blood or saliva samples

- Genotyping using targeted arrays, whole-exome sequencing, or candidate gene approaches

- Analysis of SNPs in genes encoding metabolizing enzymes (UGTs, SULTs, COMT) and transporters (ABC, SLC families) [28]

Gut Microbiota Characterization

Gut microbiota composition is a primary determinant of metabotype for many dietary bioactives:

Sample Collection:

- Fecal sample collection in sterile containers with stabilization buffer if necessary

- Immediate freezing at -80°C to preserve microbial integrity

Sequencing Protocol:

- DNA extraction using validated kits for microbial DNA

- 16S rRNA gene amplification of V3-V4 hypervariable regions

- Library preparation and sequencing on Illumina platform

- Bioinformatic analysis using QIIME2 or similar pipelines

- Taxonomic assignment against curated databases (Greengenes, SILVA)

- Functional prediction using PICRUSt2 or similar tools

Metabotype-Associated Microbes:

- Equol production: Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, Slackia isoflavoniconvertens

- Urolithin production: Gordonibacter species, Ellagibacter isourolithinifaciens

- Lunularin production: Specific resveratrol-reducing bacteria [32]

Analytical Approaches and Data Integration

Metabolomic Analysis

Metabolomic profiling provides comprehensive assessment of internal exposure to bioactive metabolites:

Untargeted Metabolomics:

- Platform: UHPLC-QTOF-MS or Orbitrap-based systems

- Sample preparation: protein precipitation with cold acetonitrile

- Chromatography: reversed-phase and HILIC separations for comprehensive coverage

- Data processing: XCMS, Progenesis QI, or similar software

- Metabolite identification: spectral matching to authentic standards and databases

Targeted Metabolomics:

- Platform: UHPLC-MS/MS with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)

- Quantification using stable isotope-labeled internal standards

- Focus on specific metabolite classes: phenolic metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, bile acids

Data Integration and Statistical Analysis

Multivariate Statistics:

- Principal component analysis (PCA) for data structure exploration

- Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) for group separation

- Orthogonal projections to latent structures (OPLS) for biomarker identification

Machine Learning Approaches:

- Random forest for feature selection and classification

- Support vector machines for metabotype prediction

- Neural networks for complex pattern recognition

Pathway Analysis:

- Metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA)

- Integration with genomic and microbial data

Visualization of Research Framework

Figure 1: Comprehensive Research Framework for Baseline Assessment and Metabotyping. This workflow integrates multiple data types to stratify populations based on metabolic capabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabotyping Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Urolithins (A, B), Equol, Lunularin, ODMA, Phase II metabolites | Metabolite identification and quantification in biofluids |

| Chromatography | UPLC/HPLC systems, HSS T3 columns, mobile phase additives (formic acid) | Separation of complex metabolite mixtures prior to detection |

| Mass Spectrometry | QTOF, Orbitrap, Triple Quadrupole systems | High-sensitivity detection and quantification of metabolites |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Microbial DNA isolation kits, host DNA removal protocols | Preparation of high-quality DNA for microbiome analysis |

| Sequencing Reagents | 16S rRNA primers, library preparation kits, sequencing chips | Characterization of gut microbiota composition and function |

| Polyphenol Challenge | Resveratrol, pomegranate extract, red clover isoflavones | Standardized compounds for metabotype determination tests |

| Sample Collection | Stabilization buffers, DNA/RNA shields, sterile containers | Preservation of sample integrity during collection and storage |

Implementation of comprehensive baseline assessment and metabotyping protocols is essential for advancing research on interindividual variability in dietary bioactive absorption. The methodologies outlined in this guide provide a rigorous framework for characterizing research participants and stratifying populations based on their metabolic capabilities. By adopting these standardized approaches, researchers can enhance study reproducibility, identify responsive subpopulations, and ultimately contribute to the development of targeted nutritional interventions that account for the substantial interindividual differences in response to dietary bioactives. The integration of multi-omics data with challenge test outcomes represents the most promising path forward for predicting individual responses to dietary components and personalizing nutritional recommendations for improved health outcomes.

The challenge of interindividual variability in response to dietary bioactives represents a significant frontier in nutritional science. Despite the well-documented health benefits of many bioactive compounds, consistent therapeutic outcomes across populations remain elusive, primarily due to complex interactions between genetics, gut microbiota, and metabolic pathways [33] [34]. Deep phenotyping through integrated omics technologies—genomics, metagenomics, and metabolomics—provides a powerful framework to deconstruct this variability, moving beyond one-size-fits-all dietary recommendations toward personalized nutrition strategies [35].

This technical guide examines how the triangulation of omics technologies can unravel the multilayered factors governing absorption, metabolism, and physiological response to dietary bioactives. By capturing the intricate interplay between host genetics, microbial communities, and metabolic phenotypes, researchers can identify key determinants of bioavailability and bioefficacy, ultimately enabling more precise and effective dietary interventions for disease prevention and health promotion [36] [35] [33].

Omics Technologies in Nutritional Research

Genomics and Nutrigenetics

Nutrigenetics explores how an individual's genetic variations influence responses to specific dietary components and nutrients [35]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes involved in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of dietary bioactives significantly contribute to interindividual variability [33]. For instance, research on (poly)phenols has identified 88 SNPs across 33 genes associated with variability in bioavailability, with 16 SNPs demonstrating significant modifying effects on urinary and/or plasma levels of phenolic metabolites [33]. These genetic variations occur in genes encoding transporters, glycosidases, and phase II enzymes such as sulfotransferases (SULTs), UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) [33].

Metagenomics and the Gut Microbiome

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors a complex ecosystem of over 5-10 trillion bacteria that play pivotal roles in nutrient metabolism, immune regulation, and production of biologically active compounds [35]. The gut microbiota acts as a key metabolic organ that significantly influences the bioavailability and bioactivity of dietary compounds [33] [34]. For glucosinolates from cruciferous vegetables, specific gut microbes possess the capacity to selectively metabolize these precursors into active isothiocyanates [34]. Similarly, most (poly)phenols reach the colon intact where they undergo microbial transformation into smaller, more bioavailable catabolites [33]. Each individual's unique microbial composition therefore serves as a major determinant of their metabolic phenotype (metabotype) and subsequent physiological response to dietary interventions [33] [34].

Metabolomics and Metabolic Phenotyping

Metabolomics provides a comprehensive analysis of small molecule metabolites in biological systems, offering a direct readout of physiological activity and biochemical status [36] [25]. In nutritional research, metabolomic profiling captures the complex metabolic consequences of dietary exposures, reflecting inputs from both host genetics and microbial metabolism [25]. Specific metabolite patterns can serve as biomarkers for predicting individual responses to dietary bioactives [25]. For example, the production of microbiota-derived catabolites from (poly)phenols varies significantly between individuals and influences the compounds ultimately available for physiological activity [33]. Metabolomic analysis also reveals how dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet improve cardiometabolic markers, with studies showing approximately a 52% reduction in metabolic syndrome prevalence within six months [25].

Table 1: Key Omics Technologies for Deep Phenotyping in Nutrition Research

| Technology | Analytical Focus | Key Applications in Bioactive Research | Representative Analytical Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence variations | Identifying SNPs in ADME genes; Nutrigenetic profiling | Whole-genome sequencing; SNP microarrays; Targeted genotyping |

| Metagenomics | Gut microbial community structure and function | Characterizing microbial biodegradation pathways; Identifying key taxa for bioactive activation | 16S rRNA sequencing; Shotgun metagenomics; Metatranscriptomics |

| Metabolomics | Small molecule metabolites (<1,500 Da) | Profiling microbial and host metabolites; Quantifying bioactive derivatives; Discovering response biomarkers | LC-MS; GC-MS; NMR spectroscopy |

Integrated Omics Approach to Interindividual Variability

The Triangulation Concept