Beyond the Calorie Count: Assessing Wearable Sensor Technologies for Dietary Intake Monitoring in Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of wearable device technologies for caloric and dietary intake assessment, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Beyond the Calorie Count: Assessing Wearable Sensor Technologies for Dietary Intake Monitoring in Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of wearable device technologies for caloric and dietary intake assessment, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science driving this field, including the synergy between continuous glucose monitors, AI-driven meal planning, and image-based sensors. The review details methodological approaches for implementing these technologies in clinical and research settings, examines common challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a critical evaluation of device validation and comparative accuracy. By synthesizing evidence from recent feasibility studies and validation trials, this article serves as a strategic guide for integrating objective dietary monitoring into biomedical research and clinical trials.

The Science of Dietary Sensing: From Physiological Tracking to AI-Driven Nutrition

The Paradigm Shift from Self-Reported to Sensor-Based Dietary Assessment

For decades, nutritional science and clinical research have relied predominantly on self-reported methods for dietary assessment, including 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), and food diaries [1] [2]. These methods are plagued by significant limitations that impede research accuracy and clinical efficacy. Systematic under-reporting of energy intake is widespread, particularly for between-meal snacks and socially undesirable foods [2]. One large-scale study comparing self-reported intake to objective energy expenditure found under-reporting averaging 33%, with greater discrepancies among men, younger individuals, and those with higher body mass index [3].

Additional challenges include recall bias, difficulties in estimating portion sizes, and reactivity (altering intake when being monitored) [1] [2]. The labor-intensive nature of data collection and coding further restricts these methods to short time periods, capturing only snapshots of highly variable eating patterns [2]. With analyses of 4-day food diaries revealing that as much as 80% of food intake variation occurs within individuals rather than between them, the limitations of traditional methods have constrained research into crucial aspects of dietary behavior [2].

The Emergence of Sensor-Based Assessment Technologies

Sensor-based dietary assessment represents a fundamental shift from subjective recall to objective measurement using wearable and mobile technologies. These approaches leverage diverse sensing modalities to capture data passively or with minimal user input, thereby reducing bias and burden [1] [4]. The field has evolved rapidly, moving from research prototypes to validated systems capable of deployment in free-living conditions.

Current sensor technologies can be broadly categorized into two approaches: those that measure eating behavior (the process of eating) and those that identify food composition (what is consumed) [4]. The most significant advancement lies in the integration of multiple sensing modalities to create comprehensive dietary monitoring systems that capture both aspects simultaneously [1] [4].

Table 1: Major Sensor Modalities for Dietary Assessment

| Sensor Modality | Measured Parameters | Examples of Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Hand-to-mouth gestures, wrist motion, jaw movement [4] [5] | Smartwatches, head-mounted sensors [6] [5] |

| Acoustic Sensors | Chewing sounds, swallowing frequency [4] | Neck-mounted microphones, eyeglass-embedded sensors [4] |

| Camera Systems | Food type, portion size, eating environment [2] [6] | Wearable cameras (eButton, AIM), smartphones [7] [6] |

| Bioimpedance Sensors | Fluid concentration changes indicating nutrient absorption [8] | Wristband devices (e.g., GoBe2) [8] |

Technical Architectures and Methodological Frameworks

Multimodal Sensing Systems

Advanced dietary monitoring systems increasingly combine multiple sensors to improve accuracy through data fusion. The Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM) represents one such approach, integrating cameras, inertial sensors, and other modalities to detect eating episodes [9]. Similarly, the DietGlance system utilizes eyeglasses equipped with IMU sensors, acoustic sensors, and cameras to capture ingestive episodes passively while preserving privacy through strategic camera placement [5].

These systems typically employ a hierarchical detection framework beginning with identification of eating episodes, followed by food recognition and quantification. The EgoDiet pipeline exemplifies this approach with specialized modules for food segmentation (SegNet), 3D reconstruction (3DNet), feature extraction, and portion size estimation (PortionNet) [6]. This modular architecture allows for targeted improvements in specific components while maintaining system integrity.

Image-Based Assessment Methodologies

Image-based methods have evolved from manual photography to automated capture and analysis. The Remote Food Photography Method (RFPM) and mobile Food Record (mFR) represent intermediate technologies requiring active user participation but providing improved accuracy over traditional recalls [2]. Validation studies against doubly labeled water have shown the RFPM underestimates energy expenditure by only 3.7%, significantly better than many self-report methods [2].

Recent advances focus on fully passive systems using wearable cameras that automatically capture images at regular intervals. These systems address the limitation of active methods, which remain susceptible to memory lapses and selective reporting [2]. The primary technical challenges include efficiently identifying the small percentage of images containing food (typically 5-10% of total captures) and accurately estimating portion sizes from single images without reference objects [2] [6].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Sensor-Based Assessment Technologies

| Technology | Validation Method | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GoBe2 Wristband [8] | Compared to weighed meals in dining facility | Mean bias: -105 kcal/day (SD 660); tendency to overestimate at lower intake and underestimate at higher intake [8] | Signal loss issues; accuracy affected by individual metabolic variations [8] |

| EgoDiet (Wearable Camera) [6] | Compared to dietitian assessments | MAPE: 31.9% for portion size (outperforming dietitians' 40.1%) [6] | Challenges with low lighting conditions; requires sufficient training data [6] |

| Camera-Based Methods [2] | Doubly labeled water | Underestimate by 3.7% (RFPM) to 19% (mFR) [2] | Burdensome image analysis; privacy concerns [2] [7] |

| Acoustic Sensors [4] | Laboratory ground truth | High accuracy for chewing and swallowing detection in controlled settings [4] | Performance degradation in noisy environments; limited food identification capability [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Laboratory-Based Validation Protocol

Controlled laboratory studies provide essential initial validation for sensor technologies. The following protocol adapts methodologies from multiple studies for comprehensive evaluation [8] [6]:

Participant Preparation: Recruit participants meeting specific inclusion criteria (typically healthy adults, balanced gender representation). Exclude those with conditions affecting eating patterns (e.g., dysphagia, dental issues) or chronic diseases affecting metabolism [8].

Sensor Configuration: Simultaneously deploy multiple sensors on each participant:

Standardized Meal Protocol: Present participants with pre-weighed meals representing diverse food types (liquids, solids, mixed consistency). Record exact weights of served and leftover items to calculate consumed mass and nutrients [8].

Data Synchronization: Use timestamps to align sensor data with video recordings (reference standard) of eating episodes.

Analysis: Calculate accuracy metrics for eating episode detection, food identification, and portion size estimation compared to ground truth measurements.

Free-Living Validation Protocol

Field testing in free-living conditions is essential for evaluating real-world applicability. The following protocol adapts approaches from recent studies [7] [6]:

Participant Screening and Training: Recruit participants representing target populations (e.g., specific ethnic groups, clinical populations). Provide comprehensive training on device usage [7].

Study Duration: Deploy sensors for extended periods (typically 7-14 days) to capture habitual intake. The study by Vasileiou et al. utilized two 14-day test periods with a wristband sensor [8].

Reference Method Integration: Implement rigorous reference methods such as:

Compliance Monitoring: Use automated sensors (e.g., camera activation timestamps) and manual checks (e.g., daily check-ins) to monitor device usage.

Data Processing and Analysis: Apply machine learning algorithms to sensor data and compare outcomes to reference methods using statistical approaches including Bland-Altman analysis and regression models [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Technologies and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Sensor-Based Dietary Assessment

| Tool/Technology | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Wearable Cameras | Passive capture of eating episodes and food items | eButton (chest-mounted), AIM (eyeglass-mounted) [7] [6] |

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Detection of eating gestures through motion patterns | Wrist-worn accelerometers, gyroscopes in smartwatches [4] [5] |

| Acoustic Sensors | Capture chewing and swallowing sounds for eating detection | Microphones embedded in necklaces or eyeglass frames [4] |

| Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) | Correlate dietary intake with physiological responses | Freestyle Libre Pro, Dexcom G6 [7] |

| Food Image Databases | Training data for computer vision algorithms | Food-101, UNIMIB2016, specialized cultural food databases [6] [10] |

| Reference Validation Tools | Establish ground truth for algorithm training | Direct observation protocols, weighed food records, doubly labeled water [8] [2] |

Implementation Workflow for Research Studies

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, sensor-based dietary assessment faces several persistent challenges. Privacy concerns remain paramount, particularly for continuous image capture [7] [4]. Technical hurdles include limited battery life, data management for high-volume image collection, and ensuring algorithm robustness across diverse populations and food cultures [2] [6]. Disparities in technology access and digital literacy may also limit broad implementation [1].

Future development will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine complementary technologies while addressing current limitations [10]. The integration of large language models (LLMs) with retrieval-augmented generation shows promise for enhancing nutritional analysis and providing personalized feedback, as demonstrated in the DietGlance system [5]. Advancements in miniaturized sensors and edge computing will enable more discreet monitoring with local data processing to address privacy concerns [4] [5].

The trajectory clearly points toward comprehensive monitoring systems that integrate dietary intake with physiological responses, enabling truly personalized nutrition recommendations based on objective data rather than estimation and recall [1] [10]. This paradigm shift will fundamentally transform nutritional science, clinical practice, and public health initiatives by providing unprecedented insights into the complex relationships between diet and health.

The objective assessment of caloric intake and energy balance is a fundamental challenge in nutritional science, obesity research, and chronic disease management. Traditional methods of dietary assessment, including food diaries, 24-hour recalls, and food frequency questionnaires, are prone to significant error, bias, and participant burden due to difficulties in estimating portion sizes, social desirability bias, and misreporting [2]. Wearable sensing technologies have emerged as transformative tools for passive, objective monitoring of eating behaviors and metabolic responses. Among these, Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) and the eButton represent two complementary technological approaches that enable researchers to capture rich, longitudinal data in free-living conditions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of these core sensor technologies, their operating principles, experimental applications, and integration within the broader context of wearable devices for caloric intake assessment research.

Technology-Specific Analysis

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Systems

2.1.1 Technical Operating Principles Continuous Glucose Monitors are wearable biosensors that measure glucose concentrations in the interstitial fluid. Unlike traditional HbA1c tests or fingerstick capillary blood measurements that provide single-point estimates, CGMs record thousands of measurements daily, revealing glucose patterns, trends, and tendencies that were previously unobservable [11]. The fundamental components of a CGM system include:

- Subcutaneous Sensor: A tiny electrode filament inserted into the interstitial fluid, typically worn on the arm or abdomen.

- Transmitter: Attached to the sensor, it wirelessly sends glucose data to a receiver or smart device.

- Receiver/Display Device: A dedicated device or smartphone app that shows real-time glucose readings, trends, and historical data.

Modern CGMs measure the electrochemical reaction between interstitial glucose and the enzyme glucose oxidase on the sensor tip, generating an electrical signal proportional to glucose concentration. Advanced algorithms filter and process this signal to account for sensor lag time between interstitial fluid and blood glucose levels [12].

2.1.2 Key Performance Metrics and Clinical Applications CGMs have revolutionized diabetes care and serve as a pivotal step toward developing an artificial pancreas system [11]. Their value extends beyond traditional diabetes management to diverse clinical scenarios:

Table 1: Key CGM Performance Metrics and Clinical Applications

| Metric/Application | Technical Specification | Research/Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Time in Range (TIR) | Percentage of time glucose spends in target range (typically 70-180 mg/dL) | Primary endpoint in clinical trials; associated with reduced diabetes complications [12] |

| Glycemic Variability | Coefficient of variation (CV) and standard deviation of glucose measurements | High variability associated with low TIR and HbA1c >7% [12] |

| Hypoglycemia Detection | Capability to identify low glucose episodes (<70 mg/dL) | Particularly valuable for patients with chronic kidney disease during dialysis [11] |

| Sleep Apnea Monitoring | Identification of nocturnal glucose swings | Reveals connections between sleep disturbances and glucose metabolism [11] |

| Post-Bariatric Surgery Monitoring | Capturing sudden glucose drops | Helps predict diabetes improvement following weight-loss surgery [11] |

Recent technological innovations have significantly expanded CGM capabilities. The Biolinq Shine wearable biosensor received FDA de novo clearance in 2025 as a needle-free, non-invasive CGM that utilizes a microsensor array manufactured with semiconductor technology, registering up to 20 times more shallow than conventional CGM needles [13]. Meanwhile, Glucotrack is advancing a 3-year implantable monitor that measures glucose directly from blood rather than interstitial fluid, eliminating lag time [13].

eButton Wearable Imaging System

2.2.1 Technical Specifications and Design The eButton is a wearable, multi-sensor device designed for passive assessment of diet, physical activity, and lifestyle behaviors. Its technical configuration includes:

- Form Factor: Chest-mounted device attached to clothing

- Imaging System: Camera that records pictures of everything in front of the wearer at regular intervals (typically 4-second intervals) [14]

- Additional Sensors: Integrated 9-axis motion sensor (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer), barometer, temperature sensor, and light sensor [14]

- Data Storage: MiniSD flash card for local storage of encrypted images

- Power Supply: Lithium-ion battery for all-day operation

The device's chest mounting is a critical design feature that optimizes its ability to capture images of meals and food preparation activities, addressing limitations of previous wearable cameras that experienced variations in lens direction due to body shape differences [2].

2.2.2 Data Processing and Food Identification Pipeline The eButton generates extensive image datasets that require sophisticated processing and analysis:

Table 2: eButton Data Processing Workflow

| Processing Stage | Methodology | Challenges and Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Image Acquisition | Automatic capture at 4-second intervals during waking hours | A 12-hour wearing period generates approximately 30,000 images; only 5-10% contain eating events [2] |

| Food Image Identification | Automatic detection using artificial intelligence and machine learning | Accuracy ranges from 95% for meals to 50% for snacks/drinks due to poor lighting and blurring [2] |

| Food Content Coding | Expert analysis by nutritionists or automated food identification using convolutional neural networks | Manual coding is time-consuming and expensive (>$10 per image); automated methods show promise with accuracy of 0.92-0.98 [2] |

| Food Preparation Behavior Analysis | Coding into categories: browsing, altering food, food media, tasks, prep work, cooking, observing | Enables measurement of child involvement in meal preparation; Cohen's kappa used to establish inter-coder reliability [14] |

Emerging Integrated Systems

The convergence of CGM and eButton technologies represents the cutting edge of integrative objective assessment. A 2025 study with Chinese Americans with type 2 diabetes demonstrated the feasibility of simultaneously using eButton and CGM for dietary management [7]. When paired, these tools helped patients visualize the relationship between food intake and glycemic response, creating a powerful method for understanding individual responses to specific foods and eating patterns [15].

Industry partnerships are accelerating the development of integrated systems. In 2025, Sequel Med Tech and Senseonics announced a commercial development agreement to combine insulin delivery and glucose monitoring systems, while Medtronic and Abbott collaborated on the Instinct sensor specifically designed for integration with automated glycemic controllers [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CGM Clinical Trial Implementation

The implementation of CGM in clinical trials requires careful consideration of data quality and missing data patterns. A retrospective assessment of CGM data from a 16-week, double-blind phase 3 trial involving 461 patients with type 1 diabetes revealed several critical methodological considerations [12]:

- Missing Data Patterns: Across three observation periods, 4.7-6% of CGM observations were missing, with approximately 16% of daily values missing on days when a new CGM sensor was inserted [12]

- Documentation Requirements: Adequate documentation indicating patient- and device-related events (e.g., sensor changes, non-wear time) is essential to address causes of missing CGM data prior to statistical assessment [12]

- Endpoint Selection: CGM metrics like Time in Range (TIR) and glucose variability are increasingly used as primary endpoints alongside traditional HbA1c measurements [12]

eButton Dietary Assessment Protocol

A standardized protocol for eButton implementation in dietary assessment research includes the following key components [14] [15]:

- Participant Training: Comprehensive explanation of the eButton device and detailed instructions for use, including how to position the device on the chest

- Wearing Protocol: Participants are instructed to wear the device from waking until bedtime for one or multiple days, depending on study design

- Data Collection: Images are automatically encrypted upon capture and emailed to research staff or downloaded directly

- Image Processing: De-identification of images using specialized software to blur visible faces for privacy protection

- Behavioral Coding: Application of structured codebooks to categorize food preparation behaviors, with inter-coder reliability measured using Cohen's kappa and percent agreement

Integrated CGM-eButton Study Design

A 2025 prospective cohort study illustrates the protocol for integrating multiple wearable sensors [15]:

- Study Population: Chinese Americans with type 2 diabetes (N=11)

- Device Deployment: Participants wore an eButton on the chest to record meals over 10 days and a Freestyle Libre Pro CGM for 14 days

- Complementary Data Collection: Participants maintained paper diaries to track food intake, medication, and physical activity

- Data Integration: Research staff downloaded CGM and eButton image data and reviewed CGM results alongside food diaries and eButton pictures to identify factors influencing glucose levels

- Qualitative Assessment: Individual interviews conducted after the monitoring period to explore user experience, barriers, and facilitators

Visualization of System Workflows

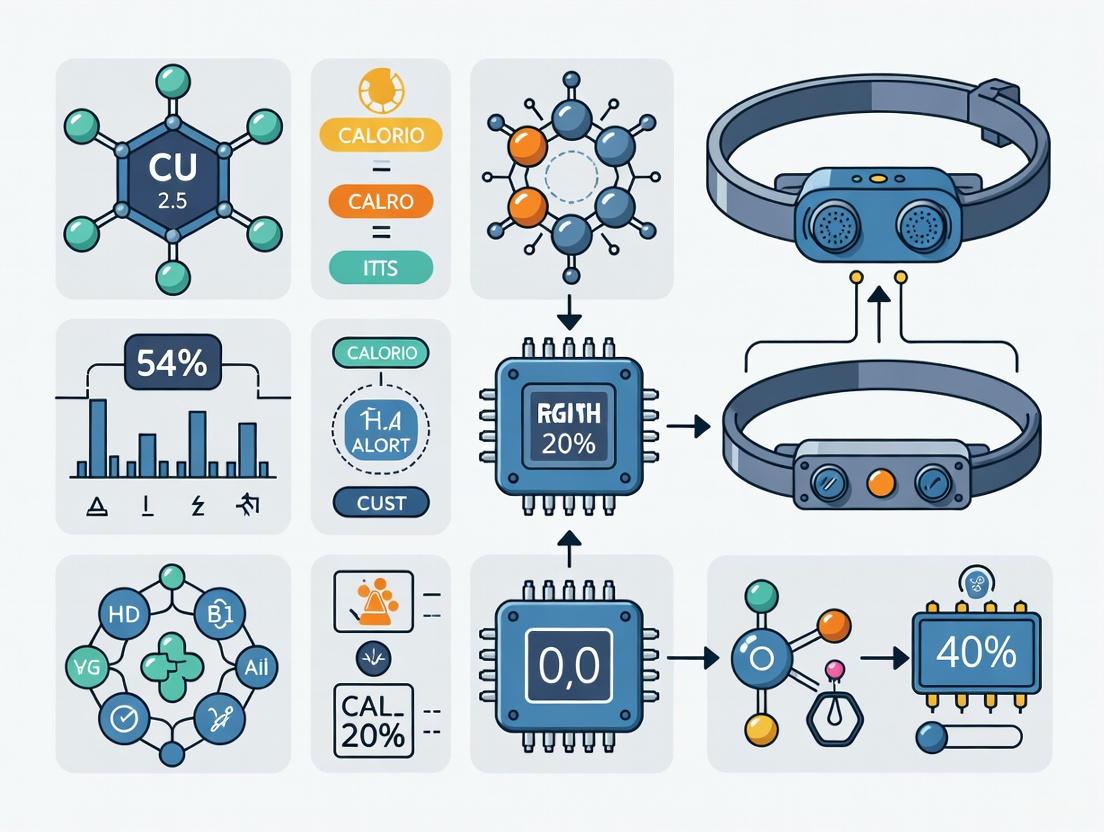

Integrated Sensing Workflow

Data Processing and Validation Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Wearable Sensor Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Freestyle Libre Pro CGM | Continuous glucose monitoring in clinical research | 14-day wear; measures interstitial glucose; requires professional application [15] |

| eButton Device | Wearable imaging for passive dietary assessment | Chest-mounted; 4-second image intervals; 9-axis motion sensor; encrypted data storage [14] |

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Gold standard validation of energy intake assessment | Biochemical marker for total energy expenditure; used to validate energy intake from image-based methods [2] |

| ATLAS.ti Software | Qualitative analysis of user experience data | Used for thematic analysis of interview transcripts regarding device usability [15] |

| Activity Categorization Software | Clustering images into homogenous events | Uses accelerometer data to group images; enables efficient identification of food preparation events [14] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Automated food identification and portion size assessment | Machine learning approach for image analysis; accuracy ranges from 0.92 to 0.98 [2] |

CGM and eButton technologies represent complementary approaches in the evolving landscape of wearable sensors for caloric intake assessment. CGMs provide high-temporal resolution metabolic monitoring, revealing individual glycemic responses to dietary intake, while the eButton offers objective, passive recording of eating behaviors and food consumption. The integration of these systems creates a powerful multimodal platform for understanding the complex relationships between diet, behavior, and metabolic health. For researchers and drug development professionals, these technologies offer novel endpoints for clinical trials, deeper insights into behavioral interventions, and opportunities for personalized medicine approaches. Future directions include the development of minimally invasive sensors, improved automated food recognition algorithms, and standardized analytical frameworks for combining physiological and behavioral data streams. As these technologies continue to advance, they hold significant promise for transforming nutritional science, chronic disease management, and precision health initiatives.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Interpreting Dietary Data from Wearables

The accurate assessment of caloric intake is a fundamental challenge in nutritional science and the management of chronic diseases. Traditional methods, such as food diaries and 24-hour recalls, are prone to significant reporting bias and inaccuracies [16]. The emergence of wearable sensors, coupled with sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models, is revolutionizing this field by enabling objective, continuous, and automated dietary monitoring. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how AI and ML are deployed to interpret complex data from wearable devices for caloric and dietary intake assessment. Framed within a broader thesis on wearable technology for nutrition research, it details the core sensing modalities, data processing methodologies, and AI architectures in use. Furthermore, it presents structured quantitative data, experimental protocols, and essential research tools, serving as a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of digital health and precision nutrition.

The global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease is intimately linked to diet [17]. A critical obstacle in nutritional research and clinical practice is the "fundamental challenge... [of] the accurate quantification of food intake" [16]. Memory-based dietary assessment methods, including food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour dietary recalls (24HR), are not only labor-intensive but also "nonfalsifiable," as they reflect perceived rather than actual intake, leading to systematic under- or over-reporting [16]. This limitation hinders the development of effective, personalized nutritional interventions.

Automated Dietary Monitoring (ADM) via wearable technology offers a paradigm shift from subjective recall to objective measurement [18]. Early wearable devices focused on simple metrics like bite counting via wrist-worn inertial measurement units (IMUs) [17]. The integration of AI has dramatically expanded these capabilities, transforming raw sensor data into actionable insights. AI, particularly machine learning and deep learning, excels at identifying complex patterns in multidimensional datasets generated by wearables, enabling the recognition of eating activities, food type classification, and even prediction of individual metabolic responses [19] [20]. This technical guide explores the core mechanisms behind this transformation, providing researchers with a foundational understanding of this rapidly advancing field.

Core Sensing Modalities and AI Interpretation

AI models are only as good as the data they process. The following section details the primary sensing modalities used in wearable dietary monitoring and the specific AI methods employed to interpret their signals.

Visual Data: Egocentric Cameras and Image Analysis

Wearable cameras capture the most direct visual record of food consumption. Systems like the eButton (worn at chest-level) and the Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM) (aligned with gaze) passively capture first-person (egocentric) video of eating episodes [6].

AI Interpretation Workflow: The raw image data is processed through a multi-stage, AI-driven pipeline, as exemplified by the EgoDiet framework [6]:

- Food and Container Segmentation: A network like EgoDiet:SegNet, based on Mask R-CNN, identifies and delineates food items and the containers they are in within each image frame.

- 3D Reconstruction and Depth Estimation: The EgoDiet:3DNet module, an encoder-decoder network, estimates the camera-to-container distance and reconstructs the 3D geometry of the containers. This is crucial for overcoming perspective distortions inherent in passive capture.

- Feature Extraction: The EgoDiet:Feature module extracts portion size-related features, such as the Food Region Ratio (FRR) and Plate Aspect Ratio (PAR), from the segmentation masks and 3D models.

- Portion Size Estimation: The final module, EgoDiet:PortionNet, uses the extracted features to perform few-shot regression, estimating the consumed portion size in weight.

This pipeline demonstrated a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 28.0% in portion size estimation in a study conducted in Ghana, outperforming the traditional 24HR method (MAPE of 32.5%) [6]. This approach is particularly valuable for population-level studies and understanding dietary behaviors in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [6].

Physiological and Acoustic Data: Bio-Impedance, Sound, and Swallowing

This category of sensing infers dietary intake by measuring the body's physiological responses during eating.

- Bio-Impedance Sensing (iEat): The iEat system uses an atypical application of bio-impedance, measuring electrical signals between electrodes on both wrists [18]. During dining activities, dynamic circuits are formed through the hands, mouth, utensils, and food, causing unique temporal patterns in impedance. A lightweight, user-independent neural network model can detect specific food-intake activities (e.g., cutting, drinking) with a macro F1 score of 86.4% and classify seven food types with a macro F1 score of 64.2% [18].

- Acoustic Sensing (AutoDietary): The AutoDietary system uses a high-fidelity, neck-worn microphone to capture sounds of mastication and swallowing [17]. AI algorithms, including signal processing and classification models, analyze these audio signals to distinguish between different food types based on their acoustic signatures.

Motion Data: Inertial Sensing and Gesture Recognition

Wrist-worn devices with inertial measurement units (IMUs), such as accelerometers and gyroscopes, detect the characteristic gestures associated with eating.

- Bite Counting: Devices like the Bite Counter use an integrated tri-axial accelerometer and gyroscope to record wrist rotational movements (e.g., hand-to-mouth gestures) to count the number of bites during a meal [17]. An algorithm then estimates total caloric intake based on the bite count and individual anthropometric data.

- Activity Recognition: More advanced models can classify the type of eating activity, such as eating with a hand versus eating with a fork, by analyzing the distinct motion patterns associated with each [18].

Metabolic Response Data: Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs)

CGMs measure interstitial glucose levels in near real-time, providing a direct window into the metabolic consequences of food intake. When combined with AI, this goes beyond monitoring to prediction.

AI models process CGM data, along with contextual information like meal composition, sleep, and stress, to build personalized models of glycemic response [20] [21]. For instance, startups like January AI use generative AI trained on millions of data points to create a "digital twin" that can predict an individual's blood sugar response to specific foods before they are consumed [21]. Research indicates that after a short adaptation period, these AI models can anticipate a user's response to common foods with up to 85% accuracy [22]. This is a key enabler for precision nutrition, as "different people spike to different foods" in a highly individualized manner [21].

Table 1: Summary of Wearable Sensing Modalities for Dietary Intake Assessment

| Sensing Modality | Example Devices/Sensors | Primary Data Type | Key AI/ML Tasks | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | eButton, AIM [6] | Egocentric Video / Images | Food segmentation, portion size estimation | MAPE: 28.0% (portion size) [6] |

| Physiological/Acoustic | iEat (Bio-impedance) [18], AutoDietary (Acoustic) [17] | Electrical Impedance, Audio Signals | Activity recognition, food type classification | Macro F1: 86.4% (activity), 64.2% (food type) [18] |

| Motion | Bite Counter [17], Wrist-worn IMU | Accelerometer, Gyroscope | Bite counting, gesture classification | Varies; can underestimate/overestimate based on utensil [17] |

| Metabolic | Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) [20] [21] | Interstitial Glucose Levels | Glucose prediction, personalized nutrition advice | Up to 85% prediction accuracy [22] |

AI Methodologies and Architectural Frameworks

The choice of AI architecture is critical and is dictated by the nature of the sensor data and the target outcome.

Deep Learning for Temporal and Visual Data

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): The backbone for image-based tasks. In the EgoDiet pipeline, a Mask R-CNN (a variant of CNN) is used for the precise segmentation of food items and containers [6].

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks: These are dominant in processing time-series data. They are extensively used for predicting interstitial glucose trends from CGM data, as they can model temporal dependencies and sequences [20]. A systematic review found that 45% of studies integrating AI with wearables for diabetes management used deep learning models, primarily RNNs and LSTMs [20].

Traditional Machine Learning and Emerging Architectures

- Traditional ML Models: Algorithms like Random Forests and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) remain popular, particularly when interpretability is a priority. They accounted for 30% of studies in the aforementioned review [20]. They are often used for classification tasks, such as identifying food types from extracted features.

- Hybrid and Transformer Models: A trend toward more sophisticated models is evident, with 25% of studies employing emerging architectures like temporal fusion transformers and hybrid models [20]. These can capture complex, long-range dependencies in multimodal data, further improving prediction accuracy.

Table 2: AI Model Performance in Diabetes Management Applications

| AI Model Type | Primary Application | Reported Performance Metrics | Prevalence in Reviewed Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning (LSTM/RNN) | Glucose prediction from CGM data [20] | RMSE <15 mg/dL (clinically acceptable) [20] | 45% [20] |

| Traditional ML (Random Forest, SVM) | Food type classification, activity recognition [20] | High interpretability; accuracy varies with features | 30% [20] |

| Hybrid & Transformer Models | Multimodal data fusion, advanced glucose forecasting [20] | Higher accuracy in some studies; less interpretable | 25% [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Robust validation is essential to transition these technologies from research to clinical application. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this paper.

Protocol: Validation of a Passive Camera System (EgoDiet)

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of a passive, vision-based pipeline (EgoDiet) for portion size estimation against dietitian assessments and the 24HR method [6].

- Study Design: Field studies conducted in London (Study A) and Ghana (Study B) among populations of Ghanaian and Kenyan origin.

- Participants: 13 healthy subjects in London; a separate cohort in Ghana [6].

- Data Collection:

- Devices: Participants wore either the AIM (eye-level) or eButton (chest-level) camera during meals.

- Meal Protocol: In a controlled facility, subjects consumed foods of Ghanaian and Kenyan origin. A standardized weighing scale (Salter Brecknell) was used to measure the true weight of food items before and after consumption to establish ground truth [6].

- Data Analysis:

- The EgoDiet pipeline processed the captured video footage.

- Outputs (estimated portion sizes in weight) were compared against dietitians' assessments (Study A) and against the 24HR method (Study B) using Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE).

Protocol: Validation of a Bio-Impedance Wearable (iEat)

- Objective: To assess the performance of the iEat wrist-worn bio-impedance system in recognizing food intake activities and classifying food types [18].

- Study Design: A food intake experiment in an everyday table-dining environment.

- Participants: 10 volunteers performing 40 meals in total [18].

- Data Collection:

- Device: Participants wore the iEat device with one electrode on each wrist.

- Meal Protocol: Participants engaged in natural dining activities, including cutting, drinking, and eating with hands or a fork. The experiment was designed to capture real-life variability.

- Data Analysis:

- Impedance signals were segmented and labeled according to activities and food types.

- A user-independent neural network model was trained and evaluated using the macro F1 score for both activity recognition and food classification tasks.

Protocol: Validation of a Caloric Intake Wristband

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of a commercial wristband (GoBe2) in estimating daily energy intake against a reference method [16].

- Study Design: A study of free-living participants over two 14-day test periods.

- Participants: 25 adult participants aged 18-50 years without chronic diseases [16].

- Data Collection:

- Test Method: Participants used the GoBe2 wristband consistently.

- Reference Method: The research team collaborated with a university dining facility to prepare, calibrate, and serve all meals. Participants consumed these meals under direct observation, allowing for precise measurement of actual energy and macronutrient intake [16].

- Data Analysis:

- Bland-Altman analysis was used to compare the daily energy intake (kcal/day) reported by the wristband against the reference method from the dining facility.

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Dietary Data Interpretation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the generalized pipeline from raw sensor data acquisition to the generation of dietary insights through AI/ML models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Wearable Dietary Monitoring Experiments

| Item / Technology | Function in Research | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wearable Cameras | Passively captures egocentric video of eating episodes for visual analysis. | eButton (chest-pin), AIM (glasses-mounted) [6]. |

| Bio-Impedance Sensor | Measures electrical impedance across the body to detect dynamic circuits formed during hand-mouth-food interactions. | Custom-built devices like iEat [18]. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Tracks wrist and arm movements to detect bites and eating gestures. | Integrated into devices like the Bite Counter [17]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides real-time, minute-by-minute interstitial glucose data to link diet with metabolic response. | Used in studies for glycemic prediction and management [20] [21]. |

| Acoustic Sensor | Captures sounds of chewing and swallowing for food type identification. | High-fidelity microphone in a neck-worn pendant (AutoDietary) [17]. |

| Standardized Weighing Scale | Provides ground truth measurement of food weight before and after consumption for algorithm validation. | Salter Brecknell scale [6]. |

| AI Modeling Frameworks | Software platforms for building, training, and validating machine learning models (CNNs, RNNs, etc.). | TensorFlow, PyTorch. Essential for implementing pipelines like EgoDiet [6]. |

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain for the widespread adoption of AI-powered dietary wearables in research and clinical practice.

- Data Quality and Accuracy: Sensor data can be noisy and affected by environmental factors or user behavior (e.g., improper device placement). Inaccurate measurements can lead to false alarms or missed intake [19].

- Demographic Diversity and Bias: Many studies have limited demographic diversity, with underrepresentation of certain racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. This can lead to biased AI models that do not generalize well [20].

- Model Interpretability: A significant portion of AI models used are complex "black-box" systems (60% in one review), which poses a barrier to clinical adoption as the reasoning behind recommendations is not transparent [20].

- Privacy and Ethics: Wearable cameras and continuous physiological monitoring raise profound data privacy concerns. Ensuring GDPR-grade compliance and transparent data handling is paramount [22].

Future research should prioritize improving model transparency using explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP, conducting larger and more diverse validation studies, and establishing clear benchmarks for evaluating AI performance in dietary assessment [20]. The ultimate goal is the development of reliable, equitable, and secure systems that can provide an objective ground truth for nutritional intake, thereby advancing the fields of precision nutrition and chronic disease management.

Diagram 2: Research Challenges and Future Directions. This chart outlines the primary obstacles in the field and the corresponding research priorities needed to overcome them.

The management of metabolic health, particularly in conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D), hinges on a precise understanding of the relationship between caloric intake and the body's subsequent physiological response. Traditional methods of dietary assessment, such as food diaries, are prone to under-reporting and inaccuracies [23]. The emergence of wearable biosensors, especially Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs), offers a paradigm shift. These devices enable the real-time, high-resolution measurement of interstitial glucose levels, providing an objective window into the metabolic consequences of nutrient consumption [24] [25]. This whitepaper details the foundational concepts, quantitative relationships, and experimental methodologies that underpin the use of real-time glucose data as a dynamic biomarker for assessing caloric intake, framed within the broader research context of wearable devices for caloric intake assessment.

Scientific Foundation: From Diet to Glycemic Response

The pathway from food consumption to a measurable change in interstitial glucose concentration involves a complex interplay of physiological processes. Understanding this pathway is crucial for interpreting CGM data in the context of caloric intake.

The Physiological Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core physiological pathway linking dietary intake to the CGM-derived glycemic response, a cornerstone for interpreting sensor data.

This physiological cascade is influenced by several key factors, creating significant inter-individual variability:

- Meal Composition: The macronutrient profile of a meal is a primary determinant of the glycemic response. Carbohydrates have the most direct and pronounced effect, but the carbohydrate quality is critical. Diets with higher fiber content or a lower carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio are associated with more favorable CGM metrics, such as reduced time spent above 140 mg/dL [26]. Replacing protein calories with carbohydrate calories has been shown to significantly increase mean CGM glucose levels [26].

- Circadian Timing and Lifestyle: High-resolution lifestyle profiling reveals that the timing of eating and sleep irregularity are strongly associated with metabolic subphenotypes like muscle insulin resistance and incretin function [27]. Furthermore, the time-of-day of physical activity exerts variable effects on glucose control depending on an individual's underlying physiology [27].

- Individual Metabolic Phenotype: Underlying physiological traits, including beta-cell function, tissue-specific insulin resistance (in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue), and impaired incretin response, fundamentally shape an individual's glycemic response to a standard meal [27].

Quantitative Link Between CGM Metrics and Nutrient Intake

The dynamic CGM trace can be distilled into specific quantitative metrics that correlate with nutrient consumption. Research has established robust correlations between these metrics and the glycemic load (GL) or macronutrient content of a meal.

Key CGM Metrics Correlated with Nutrient Intake

Table 1: CGM Metrics and Their Correlation with Glycemic Load and Carbohydrate Intake

| CGM Metric | Abbreviation | Observation Window | Correlated Nutrient | Correlation Coefficient (ρ) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance [23] | - | 4 hours | Glycemic Load | 0.43 | < 0.0004 |

| Standard Deviation [23] | SD | 4 hours | Glycemic Load | 0.41 | < 0.0004 |

| Relative Amplitude [23] | - | 3-4 hours | Glycemic Load | 0.40-0.42 | < 0.0004 |

| Area Under the Curve [23] | AUC | 2 hours | Glycemic Load | 0.40 | < 0.0004 |

| Standard Deviation [23] | SD | 24 hours | Carbohydrates | 0.45 | < 0.0004 |

| Variance [23] | - | 24 hours | Carbohydrates | 0.44 | < 0.0004 |

| Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursions [23] | MAGE | 24 hours | Carbohydrates | 0.40 | < 0.0004 |

Predictive Models for Nutrient Intake

Beyond correlation, CGM metrics can be used to construct predictive models for nutrient intake. Statistical approaches like linear mixed models have successfully predicted Glycemic Load (GL) using CGM metrics (e.g., AUC, Relative Amplitude) obtained within a 2-hour postprandial window [23]. Furthermore, models predicting total energy intake have been developed by integrating CGM metrics with other lifestyle data, such as body composition, sleep duration, and physical activity [23].

More advanced, deep learning frameworks are now being explored to create virtual CGM systems. These models use bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with an encoder-decoder architecture to infer current and future glucose levels based solely on life-log data (diet, physical activity) without prior glucose measurements, achieving a Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 19.49 ± 5.42 mg/dL [28]. This demonstrates the potential for inferring glycemic state from behavioral inputs alone.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To establish the link between real-time glucose response and caloric intake, rigorous experimental protocols are required. The following methodology, derived from a high-resolution lifestyle study, provides a gold-standard framework.

High-Resolution Physiological Phenotyping Protocol

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive assessment involves deep physiological phenotyping coupled with high-resolution digital tracking, as visualized below.

Key Methodological Details:

- Participant Cohort: Studies should include individuals across the glycemic spectrum (normoglycemia, prediabetes, T2D) with careful characterization of demographics, clinical labs (HbA1c, fasting glucose, lipids), and medication use [27].

- Digital Monitoring Duration: A minimum of 10-14 days of continuous monitoring is typical to capture habitual behavior, generating thousands of data points including meals, sleep episodes, physical activity, and CGM readings [27] [7].

- Gold-Standard Physiological Tests:

- Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT): Assesses beta-cell function and overall glucose tolerance [27].

- Insulin Suppression Test (IST): Directly measures tissue-specific insulin resistance in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue [27].

- Isoglycemic Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IVGTT): Used to isolate and quantify the incretin effect [27].

The Researcher's Toolkit

This field relies on a suite of specialized reagents, devices, and software for data acquisition and analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Wearable Dietary Monitoring

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Freestyle Libre Pro [28], Dexcom G7 [28] | Measures interstitial glucose concentrations every 5-15 minutes for real-time glycemic assessment. |

| Activity & Sleep Monitor | Wrist-worn Actigraphy Device [27] [23] | Objectively quantifies physical activity levels, energy expenditure, and sleep duration/regularity. |

| Dietary Intake Logger | Smartphone-based Food Log App [27] [28] | Captures self-reported or image-based (e.g., eButton [7]) records of food type, portion size, and timing. |

| Bio-Impedance Wearable | iEat Wristwear [18], NeckSense [29] | Detects eating gestures (bites, chews, swallows) and can classify food types passively via bio-impedance or other sensors. |

| Activity-Oriented Camera | HabitSense Bodycam [29] | Automatically records food-related activities using thermal sensing to trigger recording, preserving privacy. |

| Data Analysis Software | R package "cgmanalysis" [26], Custom Python/LSTM models [28] | Computes CGM-derived metrics (AUC, MAGE, TIR) and implements machine learning algorithms for prediction and inference. |

The integration of real-time glucose monitoring with detailed caloric and nutrient intake data represents a transformative approach to understanding human metabolism. Foundational research has firmly established that specific, quantifiable CGM metrics show significant correlations with the glycemic load and carbohydrate content of consumed meals. The timing and composition of food, alongside an individual's unique metabolic phenotype, are critical determinants of the resulting glycemic response. Experimental protocols that combine high-resolution digital phenotyping with gold-standard physiological tests are essential for validating these relationships. As the field advances, the researcher's toolkit is expanding to include not only CGMs but also a suite of complementary wearable sensors and sophisticated AI-driven analytical models. This multi-modal, data-rich paradigm is paving the way for highly personalized nutritional strategies and effective interventions for metabolic disease prevention and management.

The convergence of gut microbiome science and wearable technology is forging a new frontier in personalized health research: the Gut-Brain-Device Axis. This paradigm investigates the bidirectional relationship between gut microbial activity, brain function, and quantifiable physiological data captured from wearable devices. Framed within advanced research on caloric intake assessment, this whitepaper explores how microbiome-informed wearable data can transform our understanding of metabolic health, neurological conditions, and nutritional interventions. By integrating multi-omics microbiome analysis with continuous physiological monitoring from wearables, researchers can develop unprecedented predictive models for dietary response, neurobehavioral outcomes, and therapeutic efficacy, ultimately advancing precision medicine for metabolic and neurological disorders.

The gut-brain axis represents one of the most dynamic interfaces in human physiology, comprising bidirectional communication between gastrointestinal processes and central nervous system function. Traditional research approaches have studied this relationship through isolated physiological measures, but the emergence of sophisticated wearable technologies now enables continuous, real-time monitoring of behavioral and physiological endpoints. Simultaneously, advances in microbiome sequencing and computational analysis have revealed the profound influence of gut microbiota on both metabolic and neurological health through multiple signaling pathways [30] [31].

When contextualized within wearable devices for caloric intake assessment, this integrated approach—the Gut-Brain-Device Axis—provides a revolutionary framework for investigating how microbial activity influences dietary behaviors, nutrient absorption, and metabolic responses, while wearable data offers objective, continuous measures of these complex interactions. This technical guide examines the mechanistic foundations, methodological approaches, and experimental protocols for implementing this multidisciplinary paradigm in research settings.

Scientific Foundations of the Gut-Brain Axis

Key Communication Pathways

The gut-brain axis facilitates complex bidirectional communication through multiple parallel pathways that integrate neural, endocrine, and immune signaling mechanisms:

- Neural Pathway: The vagus nerve serves as a direct information superhighway, transmitting sensory information from the gut lumen to the brainstem and relaying efferent signals back to the gastrointestinal tract. Gut microbes produce neuroactive compounds (e.g., GABA, serotonin precursors) that directly stimulate vagal afferents [30].

- Endocrine Pathway: Enteroendocrine cells in the gut epithelium release hormones in response to microbial metabolites and nutritional cues. These include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which influence satiety, glucose homeostasis, and energy metabolism [31].

- Immune Pathway: Gut microbiota continuously interact with gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), modulating cytokine production and systemic inflammation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines can cross the blood-brain barrier, influencing neuroinflammation and brain function [30] [31].

- Circulatory/Metabolic Pathway: Microbial metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, enter systemic circulation and cross the blood-brain barrier, directly influencing brain function and behavior [30] [31].

The following diagram illustrates these primary communication pathways within the gut-brain axis:

Microbial Metabolites as Key Signaling Molecules

Gut microbiota produce numerous neuroactive and immunomodulatory metabolites that significantly influence host physiology:

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Produced from microbial fermentation of dietary fiber, butyrate, acetate, and propionate influence central and enteric nervous system function, strengthen the blood-brain barrier, and regulate appetite hormones including GLP-1 and PYY [31].

- Neurotransmitters and Precursors: Gut bacteria synthesize GABA, serotonin precursors (tryptophan), dopamine, and norepinephrine, which can influence mood, cognition, and eating behaviors [30].

- Bile Acid Metabolites: Bacteria transform primary bile acids into secondary bile acids that act as signaling molecules, influencing metabolic homeostasis, inflammation, and satiety pathways [31].

Wearable Technology for Caloric Intake and Physiological Monitoring

Wearable devices provide objective, continuous data streams that capture behavioral and physiological manifestations of gut-brain communication. The table below summarizes primary wearable modalities relevant to the Gut-Brain-Device Axis:

Table 1: Wearable Device Modalities for Gut-Brain-Device Axis Research

| Device Category | Measured Parameters | Relationship to Gut-Brain Axis | Research-Grade Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingestion Monitoring | Bites, chews, swallows, hand-to-mouth gestures [32] [33] | Automated caloric intake assessment; eating behavior patterns | Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM-2) [32] |

| Metabolic Sensing | Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), heart rate, heart rate variability [34] | Direct measurement of metabolic response to nutrition; stress physiology | Abbott Freestyle Libre, Dexcom G6 [34] |

| Physical Activity & Sleep | Activity intensity, steps, sleep stages, recovery metrics [19] [34] | Energy expenditure, circadian rhythms, recovery status | Apple Watch, Oura Ring, WHOOP Strap [19] |

| Autonomic Physiology | Heart rate variability (HRV), skin conductance, body temperature [19] | Stress response, vagal tone, inflammatory state | Empatica E4, Hexoskin Smart Shirt |

These devices enable researchers to move beyond subjective self-reporting (e.g., food diaries) to obtain high-frequency objective data on eating behaviors and their physiological consequences, thereby capturing dynamic interactions along the gut-brain axis [32] [34].

Methodological Framework for Microbiome Data Integration

Microbiome Sequencing and Analysis Protocols

Advanced sequencing technologies and specialized statistical methods are required to analyze microbiome data and integrate it with wearable device outputs:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Collect fecal samples using standardized collection kits with DNA/RNA stabilization buffers. Extract genomic DNA using kits optimized for bacterial cell lysis (e.g., MoBio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit) [31].

- Sequencing Approach: Amplify the 16S rRNA gene (V3-V4 region) for cost-effective microbial community profiling. For functional insights, employ shotgun metagenomic sequencing, which also enables strain-level identification [31] [35].

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process raw sequences through QIIME 2 or Mothur pipelines for 16S data. For metagenomic data, use HUMAnN2 for pathway analysis and MetaPhlAn for taxonomic profiling [35].

- Statistical Considerations: Account for the compositional nature of microbiome data (relative abundance) using specialized methods like ALDEx2 or ANCOM. For longitudinal analysis of microbiome-wearable data integration, employ multivariate methods like Multivariate Association with Linear Models (MaAsLin2) or linear mixed-effects models [35].

The workflow below illustrates the process for generating and integrating microbiome data with wearable device metrics:

Experimental Design Considerations

For rigorous investigation of the Gut-Brain-Device Axis, researchers should implement:

- Longitudinal Sampling: Collect microbiome samples (feces, blood for inflammatory markers) and continuous wearable data over extended periods (weeks to months) to capture dynamic interactions and establish temporal relationships [35].

- Dietary Control/Recording: Implement controlled dietary interventions or detailed food logging (via companion apps with nutrient databases) to account for nutritional inputs that directly affect both microbiome composition and physiological responses [34].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combine microbiome data with metabolomic profiling (mass spectrometry of serum/feces) to characterize the functional metabolic output of gut microbiota and its relationship to wearable-derived physiology [31].

- Cohort Stratification: Pre-stratify participants based on relevant clinical characteristics (e.g., prediabetic status, BMI categories, psychiatric comorbidities) to identify subgroup-specific relationships within the Gut-Brain-Device Axis [34].

Experimental Protocols for Gut-Brain-Device Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Microbial Influence on Glycemic Response to Caloric Intake

Objective: To determine how baseline gut microbiome composition predicts postprandial glycemic responses to standardized meals, as measured by continuous glucose monitors.

Materials:

- Research-grade continuous glucose monitors (e.g., Abbott Freestyle Libre)

- Fecal sample collection kits with DNA stabilizer

- 16S rRNA or shotgun metagenomic sequencing services

- Standardized test meals with varying macronutrient compositions

- Mobile app for meal timing logging

Procedure:

- Recruit participants meeting inclusion criteria (e.g., adults with prediabetes).

- Collect baseline fecal samples for microbiome analysis prior to dietary intervention.

- Fit participants with CGM sensors and instruct on proper use.

- Implement a rotating schedule of standardized test meals over 7-14 days, with precise recording of meal consumption times via mobile app.

- Extract features from CGM data: peak postprandial glucose, time to peak, area under the curve (AUC), and glucose variability indices.

- Sequence baseline microbiome samples and perform taxonomic/professional analysis.

- Use machine learning models (e.g., random forest regression) to predict glycemic responses from baseline microbiome features, controlling for relevant covariates.

Analysis: Identify specific microbial taxa and functional pathways associated with favorable glycemic responses, potentially informing personalized nutritional recommendations [34].

Protocol 2: Investigating Gut-Vagal Communication via Wearable-Derived Physiology

Objective: To examine associations between gut microbiome composition, heart rate variability (as a proxy for vagal tone), and eating behaviors.

Materials:

- Wearable devices capable of measuring HRV (e.g., Oura Ring, Polar H10)

- Ingestive behavior sensors (e.g., AIM-2 or acoustic sensors)

- Fecal sample collection kits

- Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) platform for stress and mood reporting

Procedure:

- Recruit participants stratified by stress-related eating behaviors.

- Collect baseline microbiome samples and administer psychological questionnaires.

- Participants wear HRV monitor and ingestive behavior sensors for 14 days.

- Implement EMA 3-5 times daily to capture stress, mood, and hunger states.

- Process HRV data to extract time-domain (RMSSD) and frequency-domain (HF power) metrics, particularly focusing on pre-prandial and post-prandial periods.

- Correlate microbial diversity and specific taxa abundances with average vagal tone and vagal responses to food intake.

- Analyze how microbiome-vagal relationships moderate stress-induced eating patterns captured by wearable sensors.

Analysis: Identify microbial signatures associated with resilient vagal responses to stress and healthier eating patterns, potentially revealing new targets for microbiome-based interventions for stress-related eating disorders [30] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Gut-Brain-Device Axis Investigation

| Category | Specific Tools & Reagents | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiome Sequencing | MoBio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, 16S rRNA primers (515F/806R), Illumina MiSeq platform, QIIME 2 pipeline | Standardized DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis of microbial communities [35] |

| Wearable Data Acquisition | Abbott Freestyle Libre CGM, Apple Watch Series, Oura Ring, AIM-2 sensor, Fitbit Charge, Empatica E4 | Continuous objective monitoring of glucose, physical activity, sleep, ingestion behavior, and autonomic physiology [32] [19] [34] |

| Computational & Analytical | R packages: vegan (alpha-diversity), MaAsLin2 (multivariate association), lme4 (mixed models), Python scikit-learn (machine learning) | Statistical analysis of microbiome data, longitudinal modeling, and predictive machine learning for integrated datasets [35] |

| Laboratory Analysis | ELISA kits for inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α), LC-MS for SCFA quantification, cortisol immunoassays | Quantification of systemic inflammation, microbial metabolites, and stress biomarkers for mechanistic insights [30] [31] |

Future Research Directions and Clinical Translation

The Gut-Brain-Device Axis framework presents several promising avenues for future investigation and clinical application:

- Microbiome-Informed Personalized Nutrition: Develop machine learning algorithms that integrate baseline microbiome data with continuous wearable metrics to generate personalized dietary recommendations for improving metabolic health, moving beyond one-size-fits-all nutritional guidance [31] [34].

- Targeted Microbiome Engineering: Explore how engineered probiotics and next-generation biotics can modulate gut-brain communication to improve outcomes in neurological disorders (e.g., Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, autism spectrum disorder), using wearable devices to objectively track behavioral and physiological responses to interventions [30] [31].

- Digital Phenotyping for Drug Development: Implement Gut-Brain-Device monitoring in clinical trials for metabolic and neurologic drugs to identify microbiome and wearable-based biomarkers that predict treatment response, potentially enabling patient stratification and personalized dosing [36].

- Closed-Loop Bio-Digital Systems: Develop integrated systems that continuously monitor physiological states via wearables and automatically deliver microbiome-modulating interventions (e.g., prebiotics, probiotics) or digital interventions (e.g., nutritional guidance) to maintain optimal metabolic and cognitive health [37].

The Gut-Brain-Device Axis represents a transformative approach for investigating the complex interactions between nutrition, gut microbiota, and brain function. By integrating high-resolution data from wearable sensors with advanced microbiome analysis, researchers can move beyond correlation to establish mechanistic links between microbial communities, their metabolic outputs, and measurable physiological and behavioral outcomes. This multidisciplinary framework, particularly when grounded in rigorous caloric intake assessment research, promises to accelerate the development of personalized interventions for metabolic disorders, neurological conditions, and the intricate interplay between them. As wearable technologies continue to evolve and microbiome sequencing becomes more accessible, this integrated approach will undoubtedly yield novel insights into human physiology and pioneer new frontiers in precision medicine.

Implementing Wearable Dietary Monitors: Protocols for Clinical and Research Settings

The integration of wearable devices into nutritional science represents a paradigm shift in data collection methodologies, demanding rigorous study designs to establish validity and reliability. Research on wearable devices for caloric intake assessment faces unique methodological challenges, including the need for objective verification of self-reported data, management of participant burden, and demonstration of clinical utility [38] [33]. The selection of an appropriate study architecture—prospective cohort or crossover trial—fundamentally shapes the research questions that can be addressed, the quality of evidence generated, and the eventual application of findings to clinical practice. This technical guide examines the core considerations, implementation protocols, and analytical frameworks for these two dominant designs within the specific context of advancing wearable technology for dietary assessment.

Prospective cohort studies provide essential real-world evidence on how wearable devices perform in free-living conditions over extended periods, making them ideal for establishing ecological validity [39] [40]. In contrast, crossover trials offer a methodologically robust approach for internal validation of devices against gold-standard measures while controlling for inter-individual variability [41] [42]. For a field grappling with the limitations of traditional self-reported dietary assessment methods—including systematic under-reporting, portion size estimation errors, and social desirability bias—these research designs provide the methodological foundation needed to advance more objective, passive monitoring technologies [38].

Prospective Cohort Studies in Wearable Research

Core Design Characteristics and Applications

Prospective cohort studies involve following a group of participants over time to observe how exposures or interventions affect specified outcomes. In wearable device research, this design is particularly valuable for understanding long-term adherence, device reliability in natural environments, and predictive validity for health outcomes [39] [40]. The defining feature of this design is the observation of outcomes as they occur naturally over time, without the researcher actively manipulating interventions.

This methodology is exceptionally suited for investigating how wearable devices function in free-living conditions, capturing data on real-world usability and identifying patterns that may not be evident in controlled settings [40]. For caloric intake assessment research, prospective cohorts can track how consistently participants use wearable technologies like wearable cameras, swallow sensors, or automated food photography apps in their daily lives, providing crucial data on feasibility and implementation barriers [38] [33]. Furthermore, this design enables researchers to examine how longitudinal data from wearables correlates with health outcomes like weight change, glycemic control, or cardiovascular risk factors, establishing predictive utility for nutritional interventions [41].

Implementation Protocol

The successful execution of a prospective cohort study for wearable device research requires meticulous planning across several domains:

Participant Recruitment and Stratification: Identify and enroll a well-defined population, often stratifying by key variables such as body mass index, age, health status, or technological proficiency. For example, the PAPHIO study focused specifically on breast cancer survivors within 3 years of diagnosis and at least 6 months post-active treatment [43]. Sample sizes vary considerably based on primary endpoints, ranging from 34 participants in a feasibility study of adolescent athletes to 20,000 in the COVID-RED study [39] [42].

Baseline Assessment: Collect comprehensive baseline data including demographic characteristics, clinical parameters, relevant biomarkers, and self-reported behavioral measures. The AI4Food study collected lifestyle data, anthropometric measurements, and biological samples from all participants at baseline [41].

Intervention Deployment: Distribute wearable devices and provide standardized training on their use. The PAPHIO study provided Fitbit Alta HR devices to all participants alongside instructions for use [43]. In the adolescent athlete study, researchers equipped participants with a Fitbit Sense for continuous monitoring of physiological markers [39].

Longitudinal Follow-up: Establish a schedule for repeated assessments at predetermined intervals. Follow-up protocols typically include device data synchronization, repeated clinical measurements, behavioral assessments, and collection of biological samples. The AI4Food study conducted these assessments throughout the nutritional intervention [41].

Data Integration and Management: Implement robust systems for aggregating multi-source data from wearables, clinical measures, and participant-reported outcomes. This often requires specialized software platforms and data processing pipelines [42].

Table 1: Key Considerations for Prospective Cohort Studies in Wearable Research

| Design Element | Considerations | Exemplar Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Selection | Target population characteristics, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sampling method | PAPHIO: Female breast cancer survivors within 3 years of diagnosis [43] |

| Sample Size | Primary outcome variability, anticipated effect size, attrition rate | COVID-RED: 20,000 participants; Adolescent athlete study: 34 participants [39] [42] |

| Follow-up Duration | Natural history of outcome, participant burden, device durability | Adolescent athlete study: 4-6 weeks post-injury clearance [39] |

| Data Collection Points | Frequency of assessments, timing relative to intervention, feasibility of repeated measures | PAPHIO: Assessments at week 1 (T1), week 12 (T2), and week 24 (T3) [43] |

| Adherence Monitoring | Methods for tracking device usage, defining adherence thresholds, handling missing data | Adolescent athlete study: Defined adherence as proportion with ≥1 heart rate data point per 24-hour period [39] |

Analytical Approaches

Statistical analysis of prospective cohort data typically employs longitudinal mixed-effects models to account for within-subject correlations over time [43]. Time-to-event analyses (e.g., Cox proportional hazards models) may be used when examining how wearable-derived metrics predict clinical outcomes. Methods for addressing missing data (e.g., multiple imputation) are particularly important given the potential for device non-adherence or technical failures.

Crossover Trials in Wearable Device Validation

Core Design Characteristics and Applications

Crossover trials represent a methodologically rigorous approach in which participants receive multiple interventions in sequentially randomized order, serving as their own controls. This design is particularly powerful in wearable research for comparing measurement techniques or validation studies where within-subject comparisons increase statistical power and control for inter-individual variability [41] [42]. The fundamental principle is that each participant experiences both the experimental and control conditions, with a washout period typically intervening to minimize carryover effects.

In wearable device research, crossover designs are exceptionally valuable for directly comparing new wearable technologies against established reference methods, or for comparing multiple wearable platforms against each other. For example, the AI4Food study employed a crossover design to compare automatic data collection methods (wearable sensors) against manual methods (validated questionnaires) within the same participants [41]. Similarly, the COVID-RED trial used a crossover approach to compare the performance of a wearable-based algorithm plus symptom diary against a symptom diary alone for early detection of SARS-CoV-2 infections [42]. This design is particularly efficient for methodological studies aiming to establish the validity and reliability of new wearable technologies for caloric intake assessment.

Implementation Protocol

Implementing a robust crossover trial for wearable device research requires careful attention to several methodological considerations:

Randomization and Sequence Generation: Participants are randomly assigned to different intervention sequences. The AI4Food study randomized participants into two groups: Group 1 started with manual data collection methods, while Group 2 started with automatic data collection methods using wearable sensors [41]. Adequate allocation concealment and sequence generation are critical to prevent selection bias.

Washout Period Determination: The interval between intervention periods must be sufficient to minimize carryover effects—where the effects of the first intervention persist into the second period. In wearable studies comparing measurement techniques, the washout period may be relatively short (e.g., the AI4Food study used a 2-week period before crossover) [41], as the interventions are measurement approaches rather than therapeutic agents with prolonged biological effects.

Intervention Protocols: Standardized protocols for each study condition are essential. In the COVID-RED trial, the experimental condition involved using data from both the Ava bracelet and a daily symptom diary, while the control condition used the symptom diary alone [42]. Detailed protocols ensure consistent implementation across participants and study sites.

Blinding Procedures: While complete blinding may be challenging when comparing visible wearable devices, partial blinding is often possible. In the COVID-RED trial, participants were blinded to their randomization sequence and whether the feedback they received was based solely on symptom diary data or combined wearable and symptom data [42].

Outcome Assessment: Primary and secondary endpoints should be clearly defined and measured consistently across study periods. The COVID-RED trial used laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections as the gold standard to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the wearable-based algorithm [42].

Table 2: Key Considerations for Crossover Trials in Wearable Research

| Design Element | Considerations | Exemplar Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Sequence generation, allocation concealment, stratification factors | COVID-RED: Stratified block randomization with 1:1 allocation to two sequences [42] |

| Washout Period | Biological persistence of intervention effects, device learning effects, participant burden | AI4Food: 2-week intervention periods with crossover after initial period [41] |

| Blinding | Feasibility of blinding participants, outcome assessors, data analysts | COVID-RED: Participants blinded to study condition and randomization sequence [42] |

| Sample Size | Within-subject correlation, effect size, primary outcome variability | AI4Food: 93 participants completing the intervention [41] |

| Statistical Analysis | Period effects, carryover effects, within-subject comparisons | COVID-RED: Intraperson performance comparison of algorithms [42] |

Analytical Approaches

The analysis of crossover trials typically employs mixed-effects models that account for both within-subject and between-subject variability. Key considerations include testing for period effects (where outcomes differ based on the sequence period) and carryover effects (where the first intervention influences the response to the second intervention). When no significant carryover effects are detected, data from both periods can be analyzed to compare interventions using paired statistical tests.

Comparative Analysis: Selecting the Appropriate Design

Decision Framework

The choice between prospective cohort and crossover designs depends on the research question, logistical considerations, and methodological priorities. The following table summarizes key comparative aspects:

Table 3: Design Selection Guide for Wearable Device Studies

| Consideration | Prospective Cohort | Crossover Trial |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Question | Natural history, prediction, real-world effectiveness | Comparative efficacy, method validation, device comparison |

| Control Group | External comparison group | Internal control (self-matching) |

| Sample Size Requirements | Generally larger | Generally smaller due to within-subject comparisons |

| Time Requirements | Longer follow-up periods | Typically shorter overall duration |