Bioaccessibility vs Bioavailability: Defining the Key Concepts for Drug and Nutrient Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of bioaccessibility and bioavailability, two fundamental yet distinct concepts in pharmaceutical and nutritional sciences.

Bioaccessibility vs Bioavailability: Defining the Key Concepts for Drug and Nutrient Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of bioaccessibility and bioavailability, two fundamental yet distinct concepts in pharmaceutical and nutritional sciences. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it clarifies definitions, explores established and emerging assessment methodologies, and addresses key challenges in enhancing compound efficacy. The scope spans from foundational principles and in vitro/in vivo models to optimization strategies and regulatory validation, offering a holistic guide for application in research and development.

Core Concepts: Defining Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability in Research and Development

In the development of functional foods and pharmaceuticals, two parameters are pivotal for predicting the efficacy of a bioactive compound: bioaccessibility and bioavailability. While often used interchangeably, they represent distinct phases in the journey of a compound from ingestion to systemic action. Bioaccessibility describes the fraction of a compound that is released from its food matrix and becomes available for intestinal absorption; it is the process of liberation into a form suitable for uptake. Bioavailability, however, refers to the proportion of the ingested compound that reaches the systemic circulation and is thus delivered to the site of physiological action [1]. This distinction is not merely semantic but is the critical path that determines the success or failure of a nutraceutical or therapeutic agent. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of this continuum is essential for rational engineering of delivery systems that can navigate the harsh environment of the gastrointestinal tract and ensure optimal biological activity.

Quantitative Distinctions: A Data-Driven Perspective

The practical impact of this distinction is quantifiable. Recent studies on encapsulated vitamins and polyphenols provide clear data on the differential performance between these two parameters, highlighting the significant attrition that can occur even after a compound is liberated.

Table 1: Comparative Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Encapsulated Bioactives

| Bioactive Compound | Delivery System | Bioaccessibility (%) | Bioavailability (%) | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins (General) | Nano-delivery Systems | 75 - 88 | Varies (2-8 fold increase) | Nano systems significantly enhance cellular transport. | [2] |

| Vitamin D | Nano-delivery Systems | - | Up to 5-fold enhancement | Enhanced cellular transport was observed. | [2] |

| Polyphenols | Purified Polyphenolic Extract (IPE) | - | 3-11 times higher | IPE showed higher indices vs. Fruit Matrix Extract (FME). | [3] |

| Curcumin | Og/W and W1/Og/W2 Emulsions | - | ~20% | 2.5x greater than literature values for free curcumin. | [1] |

| Curcumin | Oleogel | - | 41.8% of bioaccessible fraction | High efficiency post-release, but low overall bioaccessibility. | [1] |

Table 2: Stability Enhancements via Encapsulation

| Compound | Encapsulation System | Stability Provided | Citation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | Liposomes, Oleogels | > 80% | [2] | |

| Vitamin A | Emulsion-based Systems | > 70% | [2] | |

| Vitamin B12 | Spray-dried Microcapsules | - | Bioavailability enhanced up to 1.5-fold. | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability Studies

The accurate assessment of these parameters relies on well-established in vitro simulated digestion models. These protocols require a specific set of reagents to mimic the biochemical conditions of the human gastrointestinal tract.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Simulated Gastrointestinal Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Simulated Phase |

|---|---|---|

| α-amylase (from human saliva) | Catalyzes the breakdown of starch, initiating oral digestion. | Oral (2 min) |

| Pepsin (from porcine gastric mucosa) | Proteolytic enzyme that degrades proteins in the acidic stomach environment. | Gastric (30 min) |

| Pancreatin (from porcine pancreas) | A mixture of digestive enzymes (e.g., proteases, lipase, amylase) for intestinal digestion. | Intestinal (180 min) |

| Lipase (from porcine pancreas) | Specifically catalyzes the hydrolysis of fats (lipolysis). | Intestinal |

| Bile Salts | Biological surfactants that emulsify lipids, facilitating the formation of mixed micelles for absorption. | Intestinal |

| Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF) | Low-pH solution (with HCl, NaCl, etc.) replicating the chemical environment of the stomach. | Gastric |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF) | Neutral-pH solution (with NaHCO₃, KH₂PO₄, etc.) replicating the chemical environment of the intestine. | Intestinal |

| Dialysis Membranes or Filters | Used to separate the bioaccessible fraction (micellar phase) from the non-absorbable residue in static models. | Absorption Phase |

| Dynamic in vitro systems (e.g., SimuGIT) | Advanced equipment that dynamically adjusts pH, introduces secretions gradually, and mimics peristalsis and gastric emptying. | Full GIT Transit |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Assessment

StaticIn VitroDigestion Protocol

A widely adopted method for assessing bioaccessibility is the static in vitro simulation, often based on the INFOGEST protocol. The following diagram outlines the core workflow.

Assessing Bioavailability Using Cell Models

To move beyond bioaccessibility and estimate true bioavailability, the bioaccessible fraction is often applied to intestinal cell models, such as Caco-2 monolayers, to simulate transport and metabolism.

Engineering Enhanced Delivery: From Concept to Application

The core challenge in formulation science is to design delivery systems that bridge the gap between high bioaccessibility and meaningful bioavailability. Advanced encapsulation technologies are at the forefront of this endeavor. For instance, lipid-based nanoemulsions can enhance the bioaccessibility of lipophilic vitamins by solubilizing them within mixed micelles during the intestinal phase [2]. Furthermore, protein-based carriers, such as whey or soybean protein isolates, provide a protective barrier against harsh pH changes and enzymatic degradation throughout the gastrointestinal tract, thereby stabilizing the bioactive until it reaches the site of absorption [2].

The choice of delivery system can be rationalized based on the target release profile. For example, a study on curcumin delivery systems found that while a W1/Og/W2 multiple emulsion was suitable for rapid delivery, a simpler Og/W single emulsion was more appropriate for longer-term release applications [1]. This demonstrates that the critical distinction between bioaccessibility and bioavailability is not just a scientific concept but a fundamental design principle for creating effective nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals. By first ensuring efficient liberation (bioaccessibility) and then focusing on promoting absorption and transport (bioavailability), researchers can systematically engineer solutions that maximize the therapeutic potential of bioactive compounds.

The LADME framework is a fundamental pharmacokinetic model that systematically describes the journey of any bioactive compound through a biological system. This acronym represents the sequential processes of Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion that collectively determine the ultimate bioavailability and efficacy of compounds ranging from pharmaceutical drugs to nutritional bioactives [4] [5]. While these processes are presented as a sequence, they are not discrete events; rather, they often occur simultaneously, particularly with modified-release formulations where liberation may continue while previously absorbed compound is being distributed, metabolized, and eliminated [4].

In the broader context of bioaccessibility versus bioavailability research, LADME provides a critical structural framework for differentiating these related concepts. Bioaccessibility refers specifically to the fraction of a compound that is released from its matrix in the gastrointestinal tract and becomes available for intestinal absorption, representing the initial L (Liberation) phase [5]. In contrast, bioavailability encompasses the entire LADME sequence, describing the rate and extent to which the bioactive component is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and becomes available at the site of action [5] [6]. This distinction is particularly crucial in nutritional sciences, where bioactive food components must first be released from the food matrix (bioaccessible) before they can undergo the subsequent ADME processes that determine their systemic bioavailability [5].

Detailed Breakdown of LADME Processes

Liberation: The Critical First Step

Liberation represents the initial release of a bioactive compound from its delivery form, whether a pharmaceutical formulation or food matrix [4]. For orally administered compounds, this process begins with disintegration and dissolution in the gastrointestinal fluids. The liberation phase is particularly critical for compounds with poor solubility or those encapsulated in protective delivery systems designed to enhance stability. The rate and extent of liberation directly influence subsequent processes, as only dissolved molecules can permeate biological membranes [4] [6].

Advanced delivery systems have been developed to precisely control the liberation process. For sensitive compounds like vitamins, encapsulation techniques using liposomes, oleogels, or emulsion-based systems can provide over 80% stability for vitamin C and over 70% stability for vitamin A during processing and storage [2]. These protective barriers are designed to withstand harsh environmental conditions and gradually release their payload under specific physiological conditions, demonstrating how liberation can be engineered to optimize overall bioavailability.

Absorption: Gateway to Systemic Circulation

Absorption encompasses the movement of the liberated compound from the site of administration into the systemic circulation [4]. For oral administration, this primarily occurs across the intestinal epithelium through various mechanisms including passive diffusion, carrier-mediated transport, and paracellular pathways. The efficiency of absorption depends on multiple factors including the compound's molecular size, lipophilicity, ionization state, and stability in the gastrointestinal environment [6].

The critical distinction between bioaccessibility and bioavailability becomes most apparent at the absorption stage. A compound may be fully bioaccessible (released from its matrix) yet poorly bioavailable if absorption barriers prevent its transit into systemic circulation [5]. This is particularly relevant for compounds that are substrates for efflux transporters or those that undergo extensive gut metabolism. Research on zinc absorption illustrates how nutritional factors influence this process, with phytates negatively affecting absorption while proteins, peptides, and amino acids enhance bioavailability through complex formation and utilization of alternative transport pathways [7].

Distribution: Tissue Penetration and Target Engagement

Following absorption, distribution describes the reversible transfer of a compound from systemic circulation to various tissues and organs [4]. The extent of distribution determines the compound's access to its target site of action and is influenced by physiological factors including blood flow, membrane permeability, tissue composition, and binding to plasma proteins and tissue components [4] [8].

Distribution patterns vary significantly between compounds and are quantified using parameters such as volume of distribution (Vd). The distribution phase is crucial for therapeutic efficacy, as the compound must reach its target site in sufficient concentrations to exert the desired pharmacological effect. For instance, zinc distribution following absorption demonstrates the dynamic nature of this process, with over 95% of zinc located intracellularly and the highest concentrations found in muscles, bones, skin, and liver [7].

Metabolism: Biochemical Transformation

Metabolism encompasses the chemical conversion or transformation of compounds into metabolites, typically facilitating easier elimination [4]. Hepatic enzymes, particularly cytochrome P450 systems, play a major role in drug metabolism, but extrahepatic metabolism in the gut wall, kidneys, and other tissues also contributes significantly. Metabolism can produce inactive metabolites, active metabolites with similar or different pharmacological profiles, or occasionally toxic metabolites [4] [8].

Metabolic processes can be influenced by numerous factors including genetic polymorphisms, environmental factors, and interactions with other compounds. The gut microbiota plays a particularly important role in the metabolism of certain nutritional bioactives, as illustrated by the conversion of soy isoflavones into equol, which varies between individuals based on their gut microbiome composition [5]. This interindividual variability in metabolism contributes significantly to differences in compound bioavailability and efficacy across populations.

Excretion: Elimination from the Body

Excretion represents the final elimination of the parent compound and its metabolites from the body, primarily through renal (urinary) and biliary (fecal) routes, with minor contributions from pulmonary, sweat, and other pathways [4]. The rate and route of excretion determine the compound's elimination half-life and significantly influence dosing regimens [8].

For many compounds, excretion is not merely a passive elimination process but involves active transport systems. Zinc homeostasis, for example, is maintained through a balance of absorption in the duodenum and proximal jejunum and excretion primarily in feces, with urinary excretion playing a minor role [7]. When dietary zinc intake is low, fecal and urinary excretion decreases while intestinal absorption increases, demonstrating the dynamic regulation of excretion processes to maintain physiological homeostasis [7].

Table 1: LADME Processes and Their Determining Factors

| LADME Process | Key Determinants | Primary Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Liberation | Formulation characteristics, solubility, dissolution rate | Food matrix, particle size, encapsulation, digestive fluids |

| Absorption | Membrane permeability, transport mechanisms, stability | Molecular size, lipophilicity, pH, transporters, gut microbiota |

| Distribution | Blood flow, tissue permeability, protein binding | Plasma protein levels, tissue composition, blood-brain barrier |

| Metabolism | Enzyme activity, metabolic pathways | Genetic polymorphisms, drug interactions, nutritional status |

| Excretion | Renal function, biliary secretion, transporter activity | Kidney function, liver function, urine pH, enterohepatic recycling |

Contemporary Research Applications of LADME

Pharmaceutical Drug Development

In pharmaceutical research, the LADME framework forms the cornerstone of drug discovery and development, with significant resources dedicated to optimizing these properties during lead compound selection [9] [10]. The high attrition rate in drug development, previously dominated by poor pharmacokinetic properties, has substantially decreased due to early screening of LADME parameters [9]. Modern approaches incorporate both in silico predictions and high-throughput in vitro assays to assess critical parameters including solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, and drug-drug interaction potential before compounds advance to costly clinical trials [9].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) represents an advanced application of LADME principles, integrating complex mathematical models that account for detailed physiology, environmental factors, and individual patient characteristics [11]. These models evolve from simple pharmacokinetic descriptions to comprehensive frameworks that capture drug liberation, absorption, disposition, metabolism, and excretion alongside pharmacodynamic responses, enabling more accurate predictions of human responses from preclinical data [11].

Nutritional Science and Bioactive Compounds

The LADME framework has been increasingly applied in nutritional sciences to understand the bioavailability of bioactive food components and micronutrients [2] [5] [6]. Research on vitamin encapsulation technologies demonstrates how strategic intervention at the liberation stage can enhance overall bioavailability. Nano-delivery systems for vitamin D have been shown to offer 75-88% bioaccessibility and enhance cellular transport up to five-fold, while spray-dried microcapsules can increase vitamin B12 bioavailability by up to 1.5-fold [2].

Similar approaches have been applied to mineral bioavailability, with research on zinc demonstrating how dietary factors significantly influence absorption [7]. Organic forms of zinc complexed with amino acids demonstrate superior bioavailability compared to inorganic salts, attributed to their ability to utilize amino acid transporters during absorption [7]. These findings highlight how understanding specific LADME processes enables the design of more bioavailable nutritional supplements.

Interindividual Variability and Personalized Approaches

Recent research has increasingly focused on understanding the factors underlying interindividual variability in LADME processes, moving toward personalized nutrition and medicine approaches [5]. Genetic polymorphisms, gut microbiota composition, age, sex, and physiological status all contribute to significant differences in how individuals process bioactive compounds [5]. The well-documented example of soy isoflavone metabolism illustrates this principle, where only certain individuals (equol producers) possess gut microbiota capable of converting daidzein to the more bioactive equol, resulting in enhanced health benefits [5].

This understanding of interindividual variability has led to the identification of responder and non-responder subpopulations for various bioactive compounds, explaining why significant health benefits may be observed only in subgroups within clinical trials [5]. These findings underscore the importance of considering individual LADME characteristics when evaluating compound efficacy and designing personalized intervention strategies.

Table 2: Quantified Bioavailability Enhancement Through Advanced Delivery Systems

| Bioactive Compound | Delivery System | Bioavailability Enhancement | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | Liposomes, Oleogels | >80% stability | Protection from degradation, controlled release |

| Vitamin A | Emulsion-based systems | >70% stability | Enhanced solubility, gastrointestinal protection |

| Vitamin D | Nano-delivery systems | 75-88% bioaccessibility, 5-fold cellular transport | Improved solubility, enhanced mucosal permeability |

| Vitamin B12 | Spray-dried microcapsules | 1.5-fold bioavailability | Protection from gastric degradation, enhanced absorption |

| Zinc | Amino acid complexes | Superior to inorganic salts | Utilization of amino acid transporters, reduced antagonism |

Experimental Methodologies for LADME Assessment

In Silico Prediction Methods

Computational approaches for predicting LADME properties have become indispensable tools in early research phases, enabling virtual screening of compound libraries before synthetic or testing efforts [9]. These in silico methods range from quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models that correlate molecular descriptors with specific pharmacokinetic parameters to more complex physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models that integrate compound properties with physiological system data [9] [11]. The number of computational models for various LADME processes has considerably increased in recent years, providing valuable insights for lead compound optimization despite their inability to fully replace experimental verification [9].

These computational approaches are particularly valuable for predicting difficult-to-measure parameters such as tissue distribution and for extrapolating between species during preclinical development [11]. The continued refinement of these models, particularly through the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches, represents an active area of research with significant potential to accelerate compound development while reducing resource requirements [9].

In Vitro Assays and Models

In vitro methodologies provide controlled systems for evaluating specific LADME processes without the complexity and ethical considerations of whole organisms [6]. These include dissolution testing for liberation assessment, cell monolayer models (particularly Caco-2 cells) for absorption prediction, metabolic stability assays using liver microsomes or hepatocytes, and plasma protein binding studies for distribution estimation [9] [6].

The combination of sequential in vitro systems to simulate gastrointestinal passage has become particularly valuable for bioaccessibility assessment. As highlighted in zinc bioavailability research, methods combining dialysis with Caco-2 cell models provide robust correlation with human absorption data while enabling high-throughput screening [7]. Similarly, research on luteolin glucosides utilized digestive stability assessments combined with Caco-2 cell models to demonstrate how glycosylation type influences both bioaccessibility and intracellular antioxidant effects [12].

In Vivo Methodologies

Despite advances in alternative methods, in vivo studies remain essential for comprehensive LADME characterization, providing integrated data on all processes within a complete physiological system [7]. These studies typically involve administering the compound to animal models or human volunteers and collecting serial biological samples (blood, urine, tissues) to quantify the parent compound and metabolites over time [7] [8].

The sophisticated application of in vivo methodologies is illustrated by compartmental modeling approaches used to describe the kinetics of β-carotene and its conversion to retinol in healthy older adults [2]. Similarly, advanced techniques for measuring vitamin B12 bioavailability using [13C]-cyanocobalamin in humans provide precise quantification of absorption and distribution processes [2]. These in vivo data remain the gold standard for validating in silico predictions and in vitro models, particularly for regulatory submissions [8].

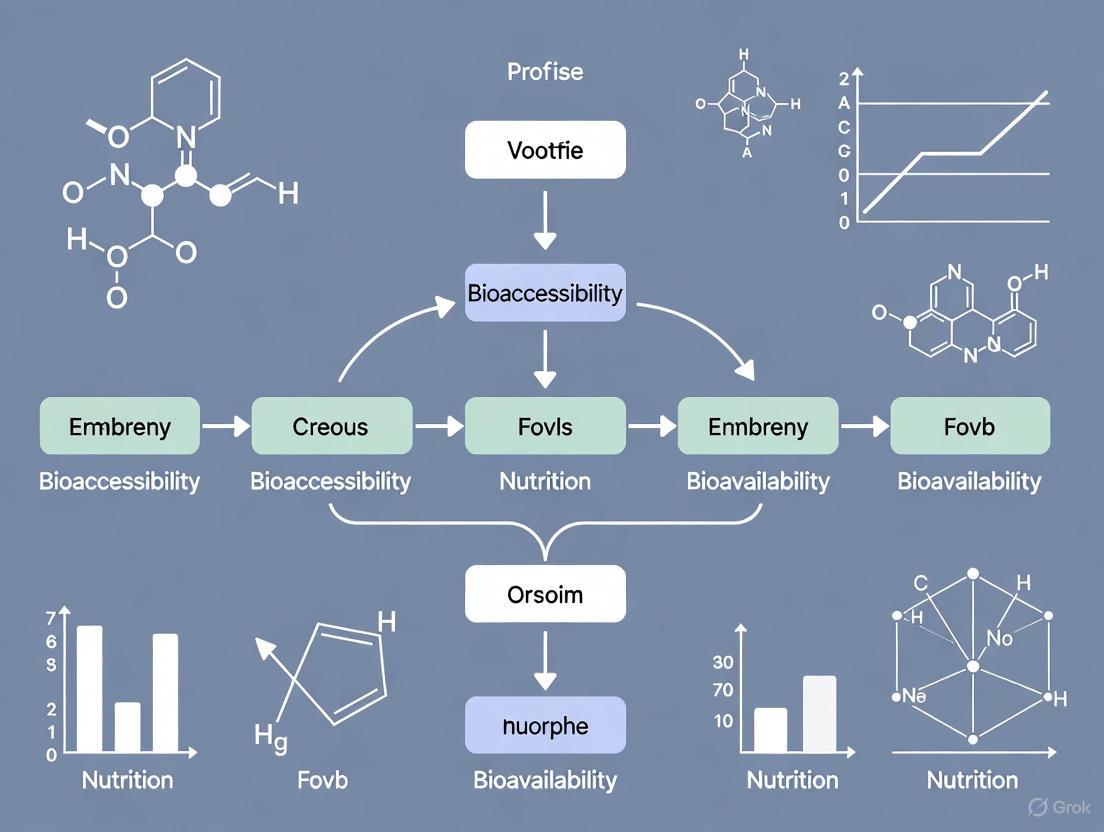

Diagram 1: The LADME Framework and Bioavailability Relationship. This workflow illustrates the sequential nature of LADME processes while highlighting how absorption, distribution, and metabolism directly influence overall bioavailability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LADME and Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Application | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 cells | Absorption prediction | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates to form intestinal epithelium-like monolayers for permeability assessment |

| Liver microsomes | Metabolism studies | Subcellular fractions containing cytochrome P450 enzymes for metabolic stability and metabolite identification |

| Artificial digestive fluids | Bioaccessibility assessment | Simulated salivary, gastric, and intestinal fluids for in vitro digestion models to evaluate compound liberation |

| Dialysis membranes | Bioaccessibility measurement | Semi-permeable membranes with specific molecular weight cutoffs to separate bioaccessible fractions |

| LC-MS/MS systems | Compound quantification | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry for sensitive detection and quantification of compounds and metabolites |

| Specific transporter substrates/inhibitors | Transport mechanism elucidation | Pharmacological tools to identify involvement of specific uptake or efflux transporters in absorption and distribution |

| Stable isotopically labeled compounds | Tracing studies | Compounds labeled with non-radioactive heavy isotopes for precise tracking of absorption, distribution, and elimination in complex biological matrices |

The LADME framework continues to provide an indispensable foundation for understanding and optimizing the bioavailability of bioactive compounds across pharmaceutical and nutritional domains. Its systematic approach enables researchers to identify specific rate-limiting steps in compound bioavailability and develop targeted strategies to overcome these barriers. The integration of advanced delivery systems, particularly nanoencapsulation technologies, demonstrates how strategic intervention at the liberation stage can dramatically enhance stability, bioaccessibility, and ultimate bioavailability of sensitive compounds [2].

Future applications of the LADME framework will increasingly focus on personalization approaches that account for interindividual variability in LADME processes due to genetic, microbiological, and physiological factors [5]. The continued refinement of integrated in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methodologies will enable more accurate predictions of human bioavailability while reducing development timelines and resource requirements [9] [11]. As these approaches mature, the LADME framework will remain central to the rational design and development of bioactive compounds with optimized bioavailability profiles tailored to specific population needs.

Diagram 2: Integrated Bioavailability Assessment Workflow. This methodology illustrates the complementary use of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo approaches to develop a comprehensive bioavailability profile, with PBPK modeling integrating data across all levels.

This whitepaper examines the distinct yet interconnected concepts of nutritional efficacy and pharmacological action through the critical lens of bioaccessibility and bioavailability. For researchers and drug development professionals, precise understanding of these terms is paramount, as they define fundamental processes from compound liberation to physiological effect. Despite their importance, inconsistent terminology persists in scientific literature, complicating cross-study comparisons and hampering development efforts. This paper provides standardized definitions, detailed experimental methodologies for in vitro and in vivo assessment, and visual workflows to clarify the pathways from ingestion to physiological impact. By framing these concepts within a rigorous technical context, we aim to establish a unified framework for evaluating compound efficacy across nutritional and pharmacological domains.

The efficacy of any ingested compound—whether a nutrient or an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)—is governed by a series of sequential processes that determine its ultimate biological fate and physiological impact. Within this cascade, bioaccessibility and bioavailability represent critical, distinct phases. Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a compound that is released from its food or drug matrix and becomes soluble in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby available for intestinal absorption [13] [14]. It is primarily concerned with digestion-mediated release and solubilization. In contrast, bioavailability describes the proportion of an administered substance that reaches systemic circulation intact, from where it can be distributed to sites of action and exert its physiological effects [15] [14].

The distinction is crucial for both nutritional science and pharmacology. In nutrition, efficacy is often evaluated as the ability of a nutrient to perform its normal physiological functions, which is inherently dependent on its bioavailability. In pharmacology, therapeutic action is measured by the drug's capacity to bind to specific molecular targets at effective concentrations, which is a function of its pharmacokinetic profile, with bioavailability (F) being a fundamental parameter [15]. Understanding the relationship between these concepts is essential for developing effective nutraceuticals, functional foods, and pharmaceutical formulations.

Core Concepts and Terminological Framework

Standardized Definitions and Comparative Analysis

The following table provides standardized definitions for the core concepts governing compound efficacy, unifying terminology across nutritional and pharmacological contexts.

Table 1: Core Terminology in Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

| Term | Technical Definition | Nutritional Context | Pharmacological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaccessibility | The fraction of a compound released from its matrix into the gut lumen during digestion, making it potentially available for absorption [13] [14]. | Liberation of nutrients (e.g., Zn, Se) from food; measured via in vitro digestion models [7] [14]. | Dissolution and solubilization of an API from its dosage form in the GI tract. |

| Bioavailability | The proportion of an ingested compound that reaches systemic circulation and is available for tissue uptake and physiological action [15] [14]. | Fraction of ingested nutrient that is absorbed and utilized (e.g., for selenoprotein synthesis) [14]. | Fraction of administered drug dose (F) that reaches systemic circulation unchanged; key PK parameter [15]. |

| Absolute Bioavailability | The systemic availability of a compound after extravascular administration compared to intravenous administration [15]. | Rarely measured for nutrients, as intravenous reference is seldom used. | Standard pharmacokinetic measure (F) calculated as AUCev/AUCiv × Doseiv/Doseev [15]. |

| Relative Bioavailability | The bioavailability of a test formulation compared to a standard formulation administered via the same route [15]. | Used to compare different food formats or supplements (e.g., organic vs. inorganic Zn) [7]. | Used in bioequivalence studies to compare generic vs. innovator drug products. |

| Nutritional Efficacy | The demonstrated ability of a nutrient to perform its normal physiological roles (e.g., as cofactor, structural element) [7]. | Improvement in health status (e.g., Zn's role in immune function, endocrine health) [7]. | Not directly applicable. |

| Pharmacological Action | The specific biochemical interaction through which a drug substance produces its therapeutic effect [15]. | Not directly applicable. | Drug-receptor binding, enzyme inhibition, or other target modulation leading to a therapeutic outcome. |

The Sequential Pathway: From Liberation to Action

The journey from ingestion to effect follows a defined sequence. The following diagram illustrates this pathway, highlighting the distinct stages of bioaccessibility and bioavailability for both nutrients and drugs.

Methodologies for Assessment

In Vitro Experimental Protocols

In vitro models are indispensable for initial, high-throughput assessment of bioaccessibility, providing controlled, reproducible, and ethical alternatives to animal studies.

3.1.1 Standardized In Vitro Digestion Protocol This protocol simulates human gastrointestinal digestion to measure the bioaccessibility of compounds from food or oral dosage forms [13] [7] [14].

- Oral Phase: The sample is mixed with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) containing electrolytes and α-amylase. The pH is adjusted to 7.0, and the mixture is incubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Gastric Phase: Simulated gastric fluid (SGF) containing pepsin is added. The pH is reduced to 3.0, and the mixture is incubated for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme is mixed with simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) containing pancreatin and bile salts. The pH is raised to 7.0, and the mixture is incubated for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Bioaccessibility Analysis: The digested sample is centrifuged. The supernatant (bioaccessible fraction) is collected and filtered. The concentration of the target compound (e.g., nutrient, API) in this fraction is quantified via HPLC, MS, or ICP-MS. Bioaccessibility (%) is calculated as (Amount in supernatant / Total amount in sample) × 100.

3.1.2 Caco-2 Cell Absorption Model This model uses human colon adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2) that spontaneously differentiate into enterocyte-like monolayers, providing a predictive tool for intestinal absorption and bioavailability [7] [14].

- Cell Culture: Caco-2 cells are cultured and seeded on porous Transwell filters. They are allowed to differentiate for 21-28 days to form a tight polarized monolayer. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) is regularly monitored to confirm monolayer integrity.

- Sample Application: The bioaccessible fraction obtained from the in vitro digestion is applied to the apical (upper) compartment, simulating the intestinal lumen.

- Incubation and Sampling: The system is incubated at 37°C for a set period (e.g., 2-4 hours). Samples are taken from the basolateral (lower) compartment at timed intervals.

- Transport Analysis: The concentration of the compound that has traversed the monolayer into the basolateral compartment is quantified. Apparent permeability (Papp) is calculated, providing a measure of absorption potential.

In Vivo Experimental Protocols

In vivo studies in animals or humans provide the definitive assessment of absolute bioavailability and physiological efficacy.

3.2.1 Absolute Bioavailability Study Design (Pharmacology) This clinical trial design is the gold standard for determining a drug's absolute bioavailability (F) by using an intravenous (IV) reference [15].

- Study Population: Healthy volunteers or patients (n=12-24) are enrolled following ethical approval and informed consent.

- Study Design: A randomized, two-period, crossover design is typically used.

- Period 1: Administration of a single IV dose.

- Washout Period.

- Period 2: Administration of a single oral dose.

- Blood Sampling: Serial blood samples are collected over a period covering at least 5 elimination half-lives post-dose for both routes.

- Bioanalysis: Plasma/serum concentrations of the API are determined using a validated analytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: The Area Under the Curve (AUC) from zero to infinity (AUC0-∞) is calculated for both IV and oral administration. Absolute bioavailability (F) is determined as: F (%) = (AUCoral / AUCIV) × (DoseIV / Doseoral) × 100.

3.2.2 Post-Absorptive Efficacy Endpoints (Nutrition) For nutrients, bioavailability is often inferred through functional efficacy measures after oral administration, as an IV reference is typically unavailable [7] [14].

- Dosing and Sampling: Subjects consume a test meal or supplement containing the nutrient of interest. Blood samples are collected over time.

- Kinetic Analysis: The plasma concentration-time curve is analyzed for the nutrient or its functional biomarkers (e.g., specific selenoproteins for Se [14], activity of Zn-dependent enzymes [7]).

- Efficacy Outcome Measures: Longer-term studies measure changes in validated physiological or functional endpoints. For example:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids (SSF, SGF, SIF) | Provide a chemically defined environment mimicking the ionic composition and pH of human digestive secretions. | Standardized in vitro digestion models (INFOGEST protocol) [13]. |

| Digestive Enzymes (Pepsin, Pancreatin, α-Amylase) | Catalyze the breakdown of complex macronutrients (proteins, fats, carbohydrates) to liberate encapsulated compounds. | Simulating proteolysis in the stomach (pepsin) and small intestine (pancreatin) [13] [14]. |

| Bile Salts (e.g., Taurocholate) | Emulsify lipids and form micelles, facilitating the solubilization of hydrophobic compounds for absorption. | Critical for studying bioavailability of lipophilic drugs and nutrients (e.g., fat-soluble vitamins) [13]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A well-established in vitro model of the human intestinal epithelium for predicting compound absorption and transport mechanisms. | Transport studies to determine apparent permeability (Papp) and identify active/passive transport pathways [7] [14]. |

| Transwell Permeable Supports | Porous filters that support the growth of polarized cell monolayers, allowing separate access to apical and basolateral compartments. | Essential for conducting Caco-2 cell transport assays [7]. |

| Analytical Standards | Highly pure reference compounds for accurate identification and quantification of analytes in complex biological matrices. | LC-MS/MS and HPLC quantification of drugs, nutrients, and their metabolites in plasma, urine, and digested samples [15] [14]. |

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Interplay

The efficacy of bioactive compounds is often mediated through complex signaling pathways. Furthermore, the gut microbiota has emerged as a critical player in modulating bioavailability. The following diagram integrates the host's metabolic pathways with the emerging role of the gut microbiome in determining bioavailability and efficacy.

The precise distinction between bioaccessibility and bioavailability provides a foundational framework for evaluating compound efficacy across the nutritional and pharmacological spectra. While bioaccessibility is a prerequisite for absorption, it does not guarantee bioavailability, which is itself a necessary but insufficient condition for nutritional efficacy or pharmacological action. The experimental methodologies outlined—from standardized in vitro digestion and Caco-2 models to rigorous in vivo pharmacokinetic and functional studies—provide a robust toolkit for deconstructing this efficacy cascade. Future research must continue to integrate emerging factors, such as the role of the gut microbiome and host genetics, into these models. A consistent and nuanced application of this terminological and methodological framework is essential for advancing the development of more effective, targeted, and personalized interventions in both food and pharmaceutical sciences.

For any orally ingested compound—be it a drug or a bioactive food component—the journey from ingestion to systemic circulation is fraught with physiological challenges. Understanding this journey is critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to enhance the efficacy of their compounds. This process is formally captured by the concepts of bioaccessibility and bioavailability.

Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a compound that is released from its food or product matrix into the gastrointestinal lumen and thus becomes accessible for intestinal absorption [16] [17]. It is the first and prerequisite step, encompassing digestive transformations. In contrast, Bioavailability is a broader, more complex term. From a nutritional and pharmacological perspective, it describes the fraction of an ingested compound that reaches the systemic circulation and is utilized for physiological functions or delivered to the site of action [18] [19] [20]. Bioavailability therefore includes the processes of bioaccessibility, absorption, metabolism, tissue distribution, and bioactivity.

The path to bioavailability is systematically described by the LADME framework: Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination [20]. This review will focus on the key physiological hurdles within the initial phases of this framework: digestive stability (liberation), absorption, and pre-systemic metabolism.

The Physiological Hurdle of Digestive Stability and Bioaccessibility

Before a compound can be absorbed, it must first be liberated from its product matrix and survive the harsh environment of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This stage, known as bioaccessibility, is the first major physiological hurdle.

The Digestive Process and Bioaccessibility

The process of bioaccessibility begins with mastication in the mouth and continues as the compound encounters various digestive fluids and enzymes throughout the stomach and intestines [20]. These digestive aids are crucial for breaking down the food or product matrix to release the compound. For lipid-soluble bioactive compounds and drugs, such as some vitamins, carotenoids, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), the sequential steps of lipid digestion—partial gastric hydrolysis, emulsification by bile, and further lipolysis by pancreatic lipases—are obligatory for their release into the GI lumen [20].

Factors Affecting Digestive Stability

Several factors determine whether a compound remains stable and is successfully released during digestion:

- Food Matrix Effect: The composition of the ingested matrix can have profound effects. Components like fat and protein can enhance the bioaccessibility of certain compounds. For instance, the bioavailability of isoflavonoids from foods containing fat and protein exceeds that from supplements consumed without food [20]. Similarly, fat in a salad dressing significantly improves the absorption of carotenoids from the salad [20].

- Impact of Processing: For plant-based compounds, processing can influence bioaccessibility by altering the plant cell wall structure. Ferulic acid in whole grain wheat, for example, has limited bioavailability due to its binding to polysaccharides. However, fermentation prior to baking can break these ester links, releasing the ferulic acid and improving its bioavailability [20].

- GI Tract Physiology: The caloric content and volume of the ingested material can cause physiological changes in the GI tract, such as altered pH, gastric emptying, and bile secretion, which in turn affect the release of the compound [20].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing the Bioaccessibility of Oral Compounds

| Factor | Impact on Bioaccessibility | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Food Matrix | Can enhance or reduce release from the matrix. | Fat improves carotenoid and quercetin bioaccessibility [18] [20]. |

| Processing | Can break down physical barriers within the matrix. | Fermentation of wheat releases bound ferulic acid [20]. |

| GI Physiology | Alters the digestive environment (pH, enzymes, bile). | Caloric content affects bile secretion and emulsification [20]. |

| Compound Stability | Determines resilience to pH and enzymatic degradation. | Peptide drugs like insulin are degraded in the GI tract [21]. |

The Physiological Hurdle of Intestinal Absorption

Once a compound is bioaccessible, it must cross the intestinal epithelium to enter the systemic circulation or lymphatic system. The mechanisms of absorption and the factors influencing them constitute the second major hurdle.

Mechanisms of Absorption

Drugs and bioactive compounds cross the semipermeable cell membranes of the intestinal epithelium through several distinct mechanisms [19] [21]:

- Passive Diffusion: This is the most common mechanism for drug absorption. Molecules move from a region of high concentration (GI lumen) to one of low concentration (bloodstream) without energy expenditure. The rate is proportional to the concentration gradient and depends on the molecule's lipid solubility, size, and degree of ionization [19] [21]. The lipoid nature of the cell membrane means lipid-soluble (lipophilic) drugs diffuse most rapidly.

- Carrier-Mediated Membrane Transport:

- Active Transport: This process is selective, requires energy, and can transport compounds against a concentration gradient. It is typically limited to drugs structurally similar to endogenous substances (e.g., ions, sugars, amino acids) [19] [21].

- Facilitated Passive Diffusion: A carrier molecule assists the substrate across the membrane without energy expenditure. It is faster than passive diffusion for specific, low-lipid-solubility molecules but cannot transport against a concentration gradient [21].

- Pinocytosis: A process where the cell membrane engulfs fluid or particles, forming a vesicle that moves into the cell interior. It requires energy and plays a role in the transport of larger molecules, such as protein drugs [21].

The Critical Role of Solubility and Ionization

A compound must be in solution to be absorbed [21]. Its solubility and ionization state, governed by the pH of the GI environment and the compound's acid dissociation constant (pKa), are critical determinants of absorption.

Most drugs are weak acids or bases, existing in both un-ionized and ionized forms. The un-ionized form is typically lipid-soluble and diffuses readily across cell membranes, while the ionized form has low lipid solubility and high electrical resistance, preventing easy membrane penetration [19] [21]. The proportion of each form is determined by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

- For a weak acid: When the environmental pH is lower than its pKa, the un-ionized form predominates.

- For a weak base: When the environmental pH is lower than its pKa, the ionized form predominates.

While theoretically a weak acidic drug (e.g., aspirin) would be best absorbed in the acidic stomach, and a weak basic drug in the more alkaline intestine, the reality is more nuanced. The small intestine is the primary site of absorption for most drugs due to its immense surface area, created by villi and microvilli, and highly permeable membranes [19] [21]. Therefore, the drug's ability to dissolve and remain in an absorbable form as it transits to the intestine is often the limiting factor.

Table 2: Key Patient-Specific and Drug-Specific Factors Affecting Absorption

| Category | Factor | Impact on Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Specific (Physiological) | Age | Gastric pH, intestinal surface area, and blood flow can change with age, reducing absorption [19]. |

| Gastric Emptying & Intestinal Transit Time | Faster emptying speeds drug delivery to the intestine; transit time affects exposure to absorptive surfaces [19] [21]. | |

| Blood Flow | Reduced perfusion (e.g., in shock) lowers the concentration gradient and passive diffusion [21]. | |

| Disease Status | GI and systemic diseases (e.g., Crohn's, cystic fibrosis, diabetes) can alter GI tract anatomy and physiology [22]. | |

| GI Content (Food) | Can slow gastric emptying, bind to drugs, or enhance dissolution of poorly soluble drugs [19] [21]. | |

| Drug-Specific (Physicochemical) | Dissolution Rate | For solid forms, dissolution is the rate-limiting step before absorption can occur [19] [21]. |

| Particle Size & Surface Area | Smaller particle size increases surface area and dissolution rate [19]. | |

| Polymorphism | Different crystalline forms of the same drug can have different solubilities and bioavailability [19]. | |

| Dosage Form | Solutions are absorbed faster than solid dosage forms like tablets and capsules [19]. |

Diagram 1: The journey of an oral compound from ingestion to systemic circulation, highlighting key hurdles of digestive stability and absorption mechanisms.

The Physiological Hurdle of Metabolism

A compound that successfully navigates absorption then faces the third major hurdle: metabolism. This process can significantly reduce the amount of intact compound that reaches the systemic circulation.

First-Pass Metabolism

A pivotal challenge for orally administered compounds is first-pass metabolism (or pre-systemic metabolism) [19]. Before a drug or bioactive compound reaches the systemic circulation, it can be extensively metabolized in the gut wall and the liver. This phenomenon is a primary reason for the low oral bioavailability of many compounds.

- Gut Wall Metabolism: The enterocytes of the intestinal epithelium contain various metabolizing enzymes, most notably cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, such as CYP3A4, which can metabolize compounds during the absorption process [20].

- Hepatic Metabolism: After absorption into the portal vein, the compound travels directly to the liver, where it is subjected to a battery of hepatic enzymes before it can enter the systemic circulation.

The Role of the Gut Microbiota

The human colon harbors a vast and diverse community of microorganisms that possess immense metabolic capability. The gut microbiota can metabolize compounds that are otherwise poorly absorbed in the upper GI tract [20]. For instance, many polyphenols are relatively poorly absorbed in the small intestine but are extensively metabolized by colonic bacteria into a range of metabolites that may be absorbed and contribute to the biological activity of the parent compound [20]. These microbial metabolites could be considered the missing link between the consumption of certain dietary compounds and their health effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Experimental Models and Reagents

To study and overcome these physiological hurdles, scientists employ a range of in vitro, in silico, and in vivo models. The choice of model is critical, as each offers a different balance of physiological relevance, throughput, cost, and ethical considerations [16].

In Vitro Digestion and Absorption Models

In vitro models are widely used to predict bioaccessibility and bioavailability, offering an ethical and high-throughput alternative to in vivo studies [16] [23].

- In Vitro Digestion Models: These simulate the physiological conditions of the human GI tract, including pH, digestive enzymes (e.g., pepsin, pancreatin), and bile salts, to study the release of compounds from their matrix (bioaccessibility) [16]. They can be static, semi-dynamic, or dynamic (computer-controlled to simulate peristalsis and secretion rates).

- Intestinal Absorption Models: To study the absorption phase, several cell-based models are used:

- Caco-2 Cell Model: This is a well-established model of the human intestinal epithelium. When cultured on permeable filters, these cells differentiate into a monolayer that exhibits microvilli and expresses brush-border enzymes and transporters, making it a standard for predicting passive and carrier-mediated intestinal drug absorption [23] [17].

- HT-29 Cell Lines: Other intestinal cell lines, such as HT-29, can be used to study specific aspects of intestinal function and immune response [23].

- Multi-Organs-on-a-Chip: Emerging microphysiological systems (MPS) can simulate the systemic distribution and interactions between different organs, such as the gut, liver, and kidney, on a microfluidic chip. This provides a more integrated view of the LADME process [16].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Bioavailability Hurdles

| Research Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Reagents/Components |

|---|---|---|

| Static In Vitro Digestion Model | Simulates gastric and intestinal phases to assess bioaccessibility. | Pepsin (gastric phase), Pancreatin (intestinal phase), Bile salts, pH-adjusted buffers [16] [23]. |

| Caco-2 Intestinal Absorption Model | Models human intestinal epithelium for transepithelial transport studies. | Caco-2 cell line, DMEM culture medium, Transwell permeable supports, Transport buffer (e.g., HBSS) [23]. |

| CYP Enzyme Inhibition Assay | Evaluates potential for first-pass metabolism by key liver enzymes. | Human CYP enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4), CYP-specific substrates (e.g., Testosterone), NADPH regeneration system, LC-MS/MS for analysis. |

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Assay | Assesses if a compound is a substrate or inhibitor of this key efflux transporter. | Cell lines overexpressing P-gp (e.g., MDCK-MDR1), Reference substrates (e.g., Digoxin), Inhibitors (e.g., Verapamil) [19]. |

Diagram 2: A multi-stage experimental workflow for predicting bioavailability, integrating in vitro digestion, cellular absorption models, and advanced microphysiological systems.

The path to achieving effective oral delivery of drugs and bioactive compounds is governed by a series of defined yet interlinked physiological hurdles: digestive stability (bioaccessibility), intestinal absorption, and pre-systemic metabolism. A deep understanding of these processes—the LADME framework—is non-negotiable for rational drug and nutraceutical development.

The factors influencing these hurdles are multifaceted, stemming from both the physicochemical properties of the compound itself and the variable physiology of the patient. Overcoming these challenges requires a sophisticated toolkit. The continued refinement of in vitro models, particularly the development of more complex and physiologically relevant systems like multi-organs-on-a-chip, promises to enhance our predictive capabilities. By systematically investigating and addressing these key physiological hurdles, researchers can design better formulations, optimize dosing regimens, and ultimately develop safer and more effective therapeutic and functional food products.

Assessment Techniques: From In Vitro Models to Clinical Bioequivalence

Within nutritional sciences and drug development, understanding the journey of dietary compounds through the human body is paramount. Two critical concepts—bioaccessibility and bioavailability—form the foundation of this understanding, yet they represent distinct phases of nutrient release and absorption [24]. Bioaccessibility refers to the proportion of a compound that is released from its food matrix during digestion and becomes accessible for intestinal absorption. It is the fraction made available for potential uptake by the intestinal epithelium [24]. In contrast, bioavailability encompasses the complete pathway, referring to the proportion of an ingested compound that is absorbed, metabolized, reaches systemic circulation, and becomes available for physiological functions or storage in target tissues [24]. This distinction is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals when evaluating the efficacy of nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, and functional foods. The INFOGEST standardized static in vitro digestion model provides a robust, harmonized methodology to simulate the gastrointestinal processes that govern bioaccessibility, serving as a critical predictive tool before undertaking more complex and costly in vivo studies [25] [26].

The INFOGEST Protocol: A Standardized Framework

The INFOGEST protocol was developed through an international consensus by the COST Action INFOGEST network to address the critical lack of standardization in in vitro digestion methodologies [25] [26]. Prior to its introduction, research teams employed a wide range of non-physiological conditions, including varying pH levels, enzyme sources and activities, and digestion times, which impeded meaningful comparison of results across studies [26]. The INFOGEST framework provides a standardized, physiologically relevant static digestion method that simulates the successive phases of the upper gastrointestinal tract: oral, gastric, and intestinal [25]. This protocol is designed for use with standard laboratory equipment, making it highly accessible while ensuring reproducibility and comparability of data across the global scientific community [25] [27].

Detailed Methodological Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of the INFOGEST static in vitro digestion protocol:

Phase-by-Phase Protocol Specifications

Oral Phase: Solid foods are typically minced to simulate chewing, then mixed with Simulated Salivary Fluid (SSF) containing electrolytes and α-amylase from human saliva (150 units per mL of SSF) at a 1:1 (v/w) ratio [26]. The mixture is incubated for 2 minutes at pH 7.0 and 37°C with constant agitation [25] [27]. For liquid samples or studies where starch digestion is irrelevant, this phase may be simplified or omitted [26].

Gastric Phase: The oral bolus is combined with Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF) and porcine pepsin (2,000 U/mL of gastric contents) [26]. The pH is adjusted to 3.0 using HCl, and the mixture is incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with agitation [25] [27]. The recommended pH represents a mean fasting-state value, though some applications may adjust to pH 2.0 for an additional 30 minutes to model postprandial acidification [27].

Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme is mixed with Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF) and porcine pancreatin (providing trypsin, chymotrypsin, amylase, and lipase activities) along with bile salts (10 mM final concentration) [28]. The pH is raised to 7.0, and the mixture is incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with agitation [25] [27]. Following digestion, the resulting chyme can be analyzed for nutrient hydrolysis products, bioaccessibility, or subjected to further absorption models.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table details the essential reagents and materials required for implementing the INFOGEST protocol, based on the standardized recommendations [25] [26] [28].

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for INFOGEST Protocol Implementation

| Reagent/Equipment | Specifications & Sources | Physiological Function in Digestion |

|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase | Human salivary (e.g., Sigma A1031); 150 U/mL in SSF [26] | Initiates starch hydrolysis in the oral cavity |

| Pepsin | Porcine gastric mucosa (e.g., Sigma P7545); 2,000 U/mL in SGF [26] [28] | Primary proteolytic enzyme in the stomach, breaks down proteins |

| Pancreatin | Porcine pancreas (e.g., Sigma P7545); contains enzyme mix [28] | Provides key intestinal enzymes (proteases, amylase, lipase) for macronutrient digestion |

| Bile Salts | Porcine bile extract (e.g., Sigma B8631); 10 mM final concentration [28] | Emulsifies lipids, forming mixed micelles to solubilize hydrophobic compounds |

| Simulated Fluids | SSF, SGF, SIF with specific electrolyte compositions [25] [26] | Maintains physiologically relevant ionic strength and pH for optimal enzyme activity |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | 0.3 M solution added incrementally [26] [28] | Cofactor for several digestive enzymes, including gastric lipase and pancreatic lipase |

Applications in Food and Nutritional Research

The INFOGEST model has been extensively applied to study the digestive fate of diverse foods and bioactive compounds, providing critical insights into bioaccessibility and informing product development.

Investigating Lipid Bioaccessibility

A prominent application of the INFOGEST protocol involves assessing the bioaccessibility of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) from enriched oil supplements. A 2023 study investigated omega-3 (EPA and DHA), conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), and conjugated linolenic acid (CLNA) from various oil sources and soft-gel capsules [29]. The findings revealed several critical factors:

- Significant Lipid Degradation: The intestinal phase caused substantial degradation of the lipid fraction, with recovery indices for major bioactive PUFAs being remarkably low across all matrixes [29].

- Impact of Oxygen and Concentration: The presence of oxygen during digestion and higher initial PUFA concentrations were correlated with increased oxidation, reducing the recovery of these sensitive compounds [29].

- Variable Antioxidant Potential: The digestion process differentially affected the antioxidant potential of the oils, negatively impacting pomegranate oil, CLNA, and omega-3 capsules, while fish oil and CLA capsules showed improved antioxidant potential post-digestion [29].

Table 2: Bioaccessibility of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids After INFOGEST Digestion [29]

| Oil Matrix | Major Bioactive PUFAs | Recovery Index (%) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pomegranate Oil | Punicic Acid (CLNA) | ~2% | Strong degradation; negative impact on antioxidant potential |

| Fish Oil | EPA & DHA (Omega-3) | 11-13% | Highest recovery among tested oils; improved antioxidant potential |

| CLNA Capsules | Conjugated Linolenic Acid | ~17% | Highest recovery but suffered from oxidation |

| CLA Capsules | Conjugated Linoleic Acid | ~6% | Low recovery but improved antioxidant potential post-digestion |

| Omega-3 Capsules | EPA & DHA | ~3% | Very low recovery; negatively impacted antioxidant potential |

Broader Food Matrix Applications

Beyond lipids, the INFOGEST protocol has been validated across a wide spectrum of food matrices. A comprehensive review highlights its use for dairy, egg, meat, seafood, fruit, vegetable, cereal, and emulsified products [30]. The method is particularly valuable for studying the digestibility of next-generation plant-based foods, such as meat, seafood, dairy, and egg analogs, allowing researchers to optimize processing techniques that maximize nutrient release [30]. The protocol's standardized nature enables direct comparison between traditional and novel food products, providing crucial data for the food industry and regulatory bodies.

Technological Advancements and Automation

While the basic INFOGEST protocol is designed for manual execution with standard lab equipment, technological advancements are enhancing its reproducibility and throughput. Automated digestion systems, such as the BioXplorer 100, can be programmed to execute the INFOGEST protocol with minimal human intervention [28]. A comparative study digesting Ensure Plus Vanilla found no significant differences in protein or lipid hydrolysis between the manual tube method and the automated BioXplorer system [28]. This automation reduces human error and ensures superior control and monitoring of critical parameters like temperature and pH, thereby enhancing data robustness and reproducibility [28].

From Bioaccessibility to Bioavailability: Intestinal Absorption Models

The INFOGEST protocol concludes with the intestinal phase, providing data on bioaccessibility. To predict bioavailability, the digesta must be applied to intestinal absorption models. The most widely used cellular model employs human intestinal cell lines, particularly Caco-2 (human col adenocarcinoma) monolayers, often co-cultured with mucus-secreting cells like HT29-MTX [29] [24]. These cells spontaneously differentiate into enterocyte-like cells and form tight junctions, creating a model intestinal barrier for transport studies.

The diagram below illustrates the pathway from food consumption to systemic bioavailability, integrating in vitro digestion and absorption models:

In the fatty acid study, despite low bioaccessibility, researchers detected significant incorporation of bioactive PUFAs into Caco-2/HT29-MTX intestinal cells, highlighting that the fraction that does get absorbed may still exert local biological effects or influence cellular metabolism [29]. This underscores the importance of combining digestion models with intestinal absorption studies to gain a more complete picture of a compound's physiological potential.

The INFOGEST static in vitro digestion protocol represents a cornerstone methodological advancement for food scientists, nutrition researchers, and drug development professionals. By providing a standardized, physiologically relevant framework for simulating upper gastrointestinal digestion, it enables reliable and comparable assessment of the bioaccessibility of nutrients and bioactive compounds from diverse matrices. As research progresses, the integration of this harmonized digestion method with advanced intestinal absorption models and automated systems will continue to refine our predictive capacity for human bioavailability, ultimately guiding the development of more effective functional foods, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceutical formulations.

In nutritional sciences and drug development, understanding the journey of a compound from ingestion to physiological utilization is paramount. This journey is conceptualized through the terms bioaccessibility and bioavailability. Bioavailability is a broader concept defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient or compound that is absorbed, becomes available for physiological functions, and is utilized by the body [31]. It encompasses the entire process of digestion, absorption, metabolism, and tissue distribution. In contrast, bioaccessibility is a subset of bioavailability. It refers specifically to the fraction of a compound that is released from its food or supplement matrix during digestion and becomes soluble in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby making it potentially available for absorption by the intestinal epithelium [31] [32] [33]. It is the "maximum or upper limit of bioavailability" [34], dependent solely on digestion and release from the food matrix, while excluding absorption, metabolism, and systemic distribution [33].

The measurement of bioaccessibility is a critical preliminary step in evaluating the efficacy of dietary supplements, functional foods, and pharmaceuticals. In vitro methods, primarily dialyzability and solubility assays, have been developed as efficient, cost-effective, and high-throughput screening tools to estimate this parameter before undertaking more complex and expensive in vivo studies [33]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these two core assays, detailing their methodologies, applications, and relevance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core In Vitro Methods for Assessing Bioaccessibility

The Principle of Solubility Assays

The solubility assay is a fundamental method for determining bioaccessibility. Its core principle is straightforward: a compound must be dissolved in the gastrointestinal fluids to be absorbable. The assay measures the fraction of a nutrient or compound that transitions into the soluble portion of the digestive chyme after the in vitro digestion process is complete [33].

Experimental Protocol for the Solubility Assay:

In Vitro Digestion: The sample first undergoes a simulated gastrointestinal digestion. This typically involves a two-step process:

- Gastric Phase: The sample is incubated with a simulated gastric fluid, usually containing pepsin (from porcine stomach) and adjusted to a low pH (e.g., pH 2.0 for adults, pH 4.0 for infants) to mimic stomach conditions [33].

- Intestinal Phase: The gastric digest is then neutralized to a pH between 5.5 and 7.0. A simulated intestinal fluid, containing pancreatin (a mixture of pancreatic enzymes such as trypsin and amylase) and bile salts, is added to mimic the environment of the small intestine [33].

Separation: Following the intestinal digestion, the entire digest is centrifuged at high speed (e.g., 10,000 × g) for a defined period. This separation yields a soluble supernatant and an insoluble precipitate [33].

Quantification: The nutrient or compound of interest is quantitatively analyzed in the supernatant. Analytical techniques such as Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) for elements, or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for organic compounds are commonly employed [33].

Calculation: The bioaccessibility is calculated as the percentage of the total compound present in the soluble supernatant.

% Bioaccessibility = (Amount in Supernatant / Total Amount in Test Sample) × 100[33].

The Principle of Dialyzability Assays

The dialyzability assay, introduced by Miller et al. in 1981 to estimate iron bioaccessibility, provides a more refined estimate [33]. It is based on equilibrium dialysis and aims to measure only the soluble compounds of low molecular weight that are capable of passing through a semi-permeable membrane, simulating passage across the intestinal mucosa [33].

Experimental Protocol for the Dialyzability Assay:

Gastric Digestion: The sample undergoes an initial gastric digestion phase with pepsin at low pH, similar to the solubility assay.

Dialysis Setup: Following gastric digestion, a dialysis tube or bag with a specific molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) is introduced into the mixture. This bag is filled with a buffer solution, such as NaHCO₃.

Intestinal Digestion and Dialysis: The system is incubated, allowing the bicarbonate buffer to slowly diffuse out of the bag and neutralize the gastric digest. Subsequently, a pancreatin/bile mixture is added to the solution outside the dialysis bag (the dialysate) to initiate the intestinal phase. During this incubation, low molecular weight, soluble compounds diffuse from the dialysate across the membrane into the buffer inside the bag.

Sample Collection: After incubation, the solution inside the dialysis bag is collected. This represents the fraction of the compound that is not only soluble but also of a size suitable for passive absorption.

Quantification and Calculation: The amount of the target compound in the dialysate (the bag's content) is quantified. The dialyzability is then calculated as:

% Dialyzability = (Amount in Dialysate / Total Amount in Test Sample) × 100[33].

An advanced variation of this method is the continuous-flow dialysis system, which uses a hollow-fibre system. This method offers a potential better estimate of in vivo bioavailability by continuously removing dialyzable components, preventing equilibrium and more closely mimicking the dynamic absorption process in the intestine [33].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for both the solubility and dialyzability assays, highlighting their key differences:

Comparative Data and Applications

The application of solubility and dialyzability assays reveals significant variations in the bioaccessibility of different elements and compounds, heavily influenced by the food matrix and chemical speciation.

Table 1: Element Bioaccessibility in Different Matrices Measured via Solubility/Dialyzability Assays

| Element/Compound | Food Matrix | Assay Type | Bioaccessibility (%) | Key Findings & Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium (Se) | Brazil Nut Flour | Not Specified | ~85% | High bioaccessibility attributed to organic speciation as selenomethionine. [35] |

| Barium (Ba) | Brazil Nut Flour | Not Specified | ~2% | Low bioaccessibility likely due to formation of insoluble salts like BaSO₄. [35] |

| Radium (Ra) | Brazil Nut Flour | Not Specified | ~2% | Very low bioaccessibility for radioactive elements. [35] |

| Iron (Fe) | Edible Herbs | BARGE (Solubility) | <30% (GI) | Bioaccessibility reduced from stomach (34-57%) to gastrointestinal phase. [36] |

| Zinc (Zn) | Edible Herbs | BARGE (Solubility) | <30% (GI) | Bioaccessibility reduced from stomach (28-80%) to gastrointestinal phase. [36] |

| Copper (Cu) | Edible Herbs | BARGE (Solubility) | 38-60% (GI) | More bioaccessible during gastrointestinal digestion than gastric. [36] |

| Magnesium (Mg) | Edible Herbs | BARGE (Solubility) | 79-95% (G), <30% (GI) | Highly soluble in gastric fluid, but precipitates in intestinal tract. [36] |

These assays are crucial for screening the impact of food matrices and processing. For instance, in vitro studies have shown that phytates negatively affect zinc absorption, while proteins, peptides, and amino acids increase its bioavailability [37] [7]. Similarly, the health benefits of polyphenols and carotenoids are not solely determined by their total content in food, but by their bioaccessible fraction, which can be significantly altered by processing techniques and interactions with other nutrients like lipids [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials required to perform standardized in vitro bioaccessibility assays, such as the unified BARGE method (UBM) or INFOGEST protocol.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for In Vitro Bioaccessibility Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Physiological Role | Typical Composition / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Saliva Fluid | Mimics oral processing; initiates enzymatic (carbohydrate) digestion. | Contains electrolytes (KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, etc.), and often α-amylase. [34] [36] |

| Simulated Gastric Fluid | Mimics stomach environment; denatures proteins and initiates proteolysis. | Pepsin (from porcine stomach), HCl to adjust pH to 2.0 (adult) or 4.0 (infant). [33] [36] |

| Simulated Intestinal/Duodenal Fluid | Mimics small intestine environment; continues digestion of macronutrients. | Pancreatin (mixture of amylase, lipase, proteases), bile salts as emulsifiers, pH adjusted to 6.5-7.0. [33] [36] |

| Bile Salts | Emulsifies lipids, facilitating lipolysis and formation of mixed micelles for absorption of hydrophobic compounds. | Often porcine bile extract. [33] |

| Dialysis Tubing | For dialyzability assays; simulates the selective absorption barrier of the intestinal mucosa. | Semi-permeable membrane with a defined Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO). [33] |

| Centrifuge | For solubility assays; separates the soluble (bioaccessible) fraction from the insoluble residue. | Capable of high-speed runs (e.g., 10,000 × g). [33] |

Advanced Models and Methodological Considerations

While solubility and dialyzability are foundational, more sophisticated models exist. The TNO Intestinal Model (TIM) is a dynamic, computer-controlled system that more accurately simulates physiological parameters like body temperature, peristalsis, gradual pH changes, and transit times [33]. It consists of multiple compartments representing the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum (TIM1), and can even include a colon simulation (TIM2) for fermentation studies [33].

To assess bioavailability (specifically, intestinal uptake and transport), the Caco-2 cell model is widely used. This human colon adenocarcinoma cell line differentiates into enterocyte-like cells when cultured on Transwell inserts, allowing researchers to measure the uptake of compounds from the apical side and their transport to the basolateral side, providing insight into absorption mechanisms [33] [38]. A co-culture of Caco-2 cells with mucus-producing HT29-MTX cells offers an even more physiologically relevant model by incorporating the protective intestinal mucus layer [33].

A critical methodological consideration is the need to protect these cell lines from the digestive enzymes used in the in vitro digestion prior to the absorption assay. This can be achieved by using a dialysis membrane placed over the cells, heat-inactivating the enzymes (which may denature other compounds), or utilizing the more physiologically relevant Caco-2/HT29-MTX co-culture where the mucus layer acts as a natural barrier [33].

The relationship between different models in the study of compound absorption is summarized below:

Dialyzability and solubility assays are indispensable tools in the scientist's arsenal for the initial assessment of bioaccessibility. They provide a critical, high-throughput link between the total content of a compound in a matrix and its potential for absorption. While these methods are powerful for screening and ranking, and for studying the effects of inhibitors, promoters, and processing, they represent a simplification of a complex in vivo reality. Therefore, data from these in vitro assays should be interpreted as an estimate of the maximum potential bioavailability. For a comprehensive understanding, these methods are best used as part of a tiered strategy, informing the design of more complex cell-based models and, ultimately, validating clinical trials to fully elucidate the bioavailability and health impacts of dietary bioactives, nutrients, and pharmaceutical compounds.

In the development of new drugs and functional foods, accurately predicting how a substance is absorbed by the human intestine is a critical challenge. Within this context, two distinct but related concepts—bioaccessibility and bioavailability—form the cornerstone of absorption research. Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a compound that is released from its food or dosage matrix and becomes soluble in the gastrointestinal tract, making it available for intestinal absorption. In contrast, bioavailability describes the proportion of the ingested substance that reaches the systemic circulation and is delivered to the site of action, thereby exerting a physiological effect. The difference between these two parameters is significant; a compound may be fully bioaccessible yet exhibit poor bioavailability due to extensive metabolism or active efflux during intestinal transit.

To bridge the gap between simple chemical tests and complex human studies, researchers have developed sophisticated in vitro models that simulate human intestinal absorption. Among these, the Caco-2 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) cell line has emerged as the gold standard for predicting intestinal permeability. When cultured under specific conditions, these cells spontaneously differentiate to form a polarized monolayer that morphologically and functionally resembles the small intestinal epithelium, complete with tight junctions and brush border enzymes. This technical guide explores the pivotal role of Caco-2 cell cultures in simulating absorption, providing researchers with detailed methodologies, applications, and emerging advancements in the field.

The Caco-2 Model: Fundamentals and Validation

Biological and Functional Basis

The Caco-2 cell model is prized for its ability to mimic the human intestinal barrier without the ethical and practical complexities of human or animal studies. Upon reaching confluency, Caco-2 cells undergo a differentiation process over 14-21 days, developing critical characteristics of absorptive enterocytes:

- Formation of tight junctions that create a physiologically relevant barrier, allowing for the measurement of paracellular transport.

- Expression of a well-defined brush border with associated microvilli and digestive enzymes, such as alkaline phosphatase and sucrase-isomaltase [39].