Bioactive Compounds and the Gut Microbiota: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions in Precision Medicine

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate interplay between dietary bioactive compounds and the gut microbiota, a dynamic interface critical for human health.

Bioactive Compounds and the Gut Microbiota: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions in Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate interplay between dietary bioactive compounds and the gut microbiota, a dynamic interface critical for human health. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms by which polyphenols, fibers, and other bioactives modulate microbial ecology and metabolite production. The scope extends to methodological advances in studying these interactions, the challenges of individual variability and drug-microbiome interactions (pharmacomicrobiomics), and the validation of these relationships in therapeutic contexts for conditions like inflammatory diseases, metabolic disorders, and cancer. The review concludes by highlighting the transformative potential of leveraging these insights for developing targeted, microbiome-informed therapies and precision nutrition strategies.

The Gut-Microbiota Interface: How Bioactive Compounds Shape Our Microbial Ecosystem

Dietary bioactive compounds are secondary metabolites derived from plant-based foods that exert significant effects on human health beyond basic nutrition, primarily through their modulation of the gut microbiota. These compounds, which include polyphenols, flavonoids, dietary fibers, and carotenoids, escape digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and reach the colon, where they are metabolized by the residing microbial communities. This biotransformation process produces a myriad of bioactive metabolites that influence host physiology, immune function, and metabolic pathways. Understanding the structural diversity, dietary sources, and microbial metabolism of these compounds is fundamental to advancing gut microbiota research and developing targeted nutritional interventions for chronic disease prevention and management. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of these key dietary bioactives, with emphasis on their classification, sources, and analytical approaches for researchers and drug development professionals.

Polyphenols

Definition and Classification

Polyphenols constitute a large family of naturally occurring phenols characterized by the presence of multiple phenolic rings with hydroxyl groups [1]. They are abundant in plants and structurally diverse, with molecular weights typically ranging from 500 to 4000 Daltons [1]. The White–Bate-Smith–Swain–Haslam (WBSSH) definition characterizes polyphenols as moderately water-soluble compounds with more than 12 phenolic hydroxyl groups and 5–7 aromatic rings per 1000 Da [1]. According to Quideau's more inclusive definition, polyphenols are compounds derived from the shikimate/phenylpropanoid and/or polyketide pathways, featuring more than one phenolic unit without nitrogen-based functions [1].

Polyphenols are classified into four principal categories based on their chemical structure: phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes, and lignans [1] [2]. This classification reflects their biosynthetic origins and structural complexity, which directly influence their bioavailability and physiological effects.

Table 1: Major Classes of Polyphenols and Their Characteristics

| Class | Subclasses | Representative Compounds | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Acids | Hydroxybenzoic acids, Hydroxycinnamic acids | Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid | C1-C6 and C3-C6 backbones [2] |

| Flavonoids | Flavonols, Flavanols, Flavanones, Anthocyanins, Isoflavones | Quercetin, Catechin, Cyanidin, Daidzein | C6-C3-C6 skeleton with varying oxidation states [2] |

| Stilbenes | - | Resveratrol | C6-C2-C6 structure with two phenyl groups connected by a two-carbon methylene bridge [2] |

| Lignans | - | Secoisolariciresinol | Phenylpropane dimers [2] |

Polyphenols are widely distributed in the plant kingdom, with particularly high concentrations found in fruits, vegetables, cereals, beans, tea, coffee, honey, and red wine [2]. The most abundant polyphenols are the condensed tannins, found in virtually all families of plants, often concentrated in leaf tissue, epidermis, bark layers, flowers, and fruits [1]. Total phenolic content in plant tissues typically ranges from 1% to 25% of dry green leaf mass, varying widely depending on plant species, tissue type, and environmental conditions [1].

Bioavailability of polyphenols is generally low, with a large proportion of dietary polyphenols remaining unabsorbed along the gastrointestinal tract [2]. Their complicated structures and high molecular weights limit absorption in the small intestine, resulting in accumulation in the large intestine where they undergo extensive biotransformation by gut microbiota into bioactive, low-molecular-weight phenolic metabolites [2]. This microbial metabolism is crucial for unlocking the health-promoting effects of polyphenols.

Table 2: Major Dietary Sources of Polyphenols

| Food Category | Specific Sources | Dominant Polyphenol Types |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Berries, apples, grapes, pears, cherries | Flavonols, anthocyanins, flavanols, phenolic acids |

| Vegetables | Onions, kale, broccoli, tomatoes, parsley | Flavonols, flavones, phenolic acids |

| Beverages | Tea, coffee, red wine | Flavanols, flavonols, phenolic acids |

| Cereals & Legumes | Soybeans, whole grains | Isoflavones, phenolic acids, lignans |

| Nuts & Seeds | Flaxseed, almonds | Lignans, phenolic acids |

Experimental Protocols for Polyphenol Analysis

Extraction Methodologies

Efficient extraction is critical for accurate polyphenol analysis. Conventional solvent extraction remains the most widely used approach, with the choice of solvent depending on the polyphenol classes of interest [1]. Common protocols include:

- Solvent Selection: Water, methanol, methanol/formic acid, methanol/water/acetic or formic acid mixtures are typically employed. The polarity of the solvent should match the target polyphenols [1].

- Advanced Extraction Techniques: Ultrasonic extraction, heat reflux extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, critical carbon dioxide, high-pressure liquid extraction, and immersion extractors using ethanol have been developed to improve efficiency and reduce solvent consumption [1].

- Optimization Parameters: Extraction conditions including temperature, duration, solvent-to-solid ratio, particle size, and solvent concentration must be optimized for different raw materials [1].

Analysis and Quantification

- Separation Techniques: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), especially reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC), is the gold standard for polyphenol separation [1].

- Detection Methods: Diode array detectors coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) provide both structural identification and quantification capabilities [1].

- Quantification Approaches: Volumetric titration using permanganate as an oxidizing agent can quantify tannin content [1]. Colorimetric methods include the Porter's assay for specific polyphenol classes and the Folin-Ciocalteu reaction for total phenol content, with results expressed as gallic acid equivalents [1].

- Antioxidant Capacity Assays: The Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay using ABTS radical cation, diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH), oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC), and ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) assays are commonly employed [1].

Flavonoids

Structural Classification and Properties

Flavonoids represent the largest subclass of polyphenols, with over 10,000 identified structures [3]. They share a common C6-C3-C6 skeleton consisting of two aromatic rings (A and B) connected by a three-carbon bridge that forms an oxygenated heterocycle (C ring) [3]. This basic structure allows for extensive structural variation through different substitution patterns, degrees of unsaturation, and oxidation states of the C ring.

Flavonoids are classified into seven major subclasses based on these structural modifications: flavones, flavonols, flavanones, isoflavonoids, flavanols, anthocyanins, and chalcones [3] [4]. Each subclass possesses distinct chemical properties that influence their biological activities, bioavailability, and microbial metabolism.

Table 3: Major Subclasses of Flavonoids and Their Characteristics

| Subclass | Structural Features | Representative Compounds | Key Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonols | 3-hydroxyflavone backbone with a double bond between C2 and C3 | Quercetin, Kaempferol, Myricetin | Onions, kale, broccoli, apples, tea [5] [3] |

| Flavones | No substitution at C3 position | Apigenin, Luteolin | Parsley, celery, chamomile, mint [3] |

| Flavanones | Saturated C ring with no double bond between C2 and C3 | Naringenin, Hesperetin | Citrus fruits and peels [5] [3] |

| Isoflavonoids | B-ring attached at C3 position of C-ring | Genistein, Daidzein | Soybeans, legumes [5] [3] |

| Flavanols | Hydroxyl group at C3, no double bond between C2 and C3 | Catechin, Epicatechin | Tea, cocoa, apples, grapes [5] [3] |

| Anthocyanins | Flavylum cation structure, exist as glycosides | Cyanidin, Delphinidin | Berries, red grapes, red cabbage [5] [3] |

| Chalcones | Open-chain structure with no heterocyclic C ring | Phloretin, Arbutin | Tomatoes, pears, strawberries [5] |

Biosynthesis Pathways

Flavonoids are synthesized through the phenylpropanoid pathway, which originates from the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine [3]. The pathway involves a series of enzymatic reactions that sequentially modify the basic phenylpropanoid skeleton:

- Initial Conversion: Phenylalanine is converted to cinnamic acid by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL).

- Hydroxylation: Cinnamic acid undergoes hydroxylation to form p-coumaric acid.

- Activation: Formation of p-coumaroyl-CoA by 4-coumarate:CoA ligase.

- Core Structure Formation: Condensation of p-coumaroyl-CoA with three molecules of malonyl-CoA by chalcone synthase produces the first flavonoid, naringenin chalcone.

- Structural Diversification: Chalcone isomerase catalyzes the formation of the flavanone naringenin, which serves as the central intermediate for the biosynthesis of all other flavonoid classes through the action of various enzymes including hydroxylases, reductases, and glycosyltransferases.

This biosynthetic pathway is highly conserved across plant species, though the specific flavonoid profiles vary considerably depending on genetics, developmental stage, and environmental conditions.

Interaction with Gut Microbiota

The bidirectional interaction between flavonoids and gut microbiota represents a crucial aspect of their bioactivity. Most dietary flavonoids are poorly absorbed in the small intestine due to their glycosylated forms and complex structures, with approximately 90-95% reaching the colon [4]. Here, they undergo extensive microbial metabolism through three primary mechanisms:

- Deglycosylation: Removal of sugar moieties by bacterial glycosidases such as β-glucosidase, enhancing absorption.

- Ring Cleavage: Breakdown of the heterocyclic C ring producing various phenolic acids and other metabolites.

- Modification Reactions: Including dehydroxylation, demethylation, and decarboxylation.

These microbial transformations produce bioactive metabolites with enhanced absorption and diverse physiological effects. Simultaneously, flavonoids modulate the composition and function of gut microbiota, often promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus) while inhibiting potential pathogens [4]. This reciprocal relationship significantly influences host health through multiple pathways, including strengthening intestinal barrier function, modulating immune responses, and regulating metabolic processes.

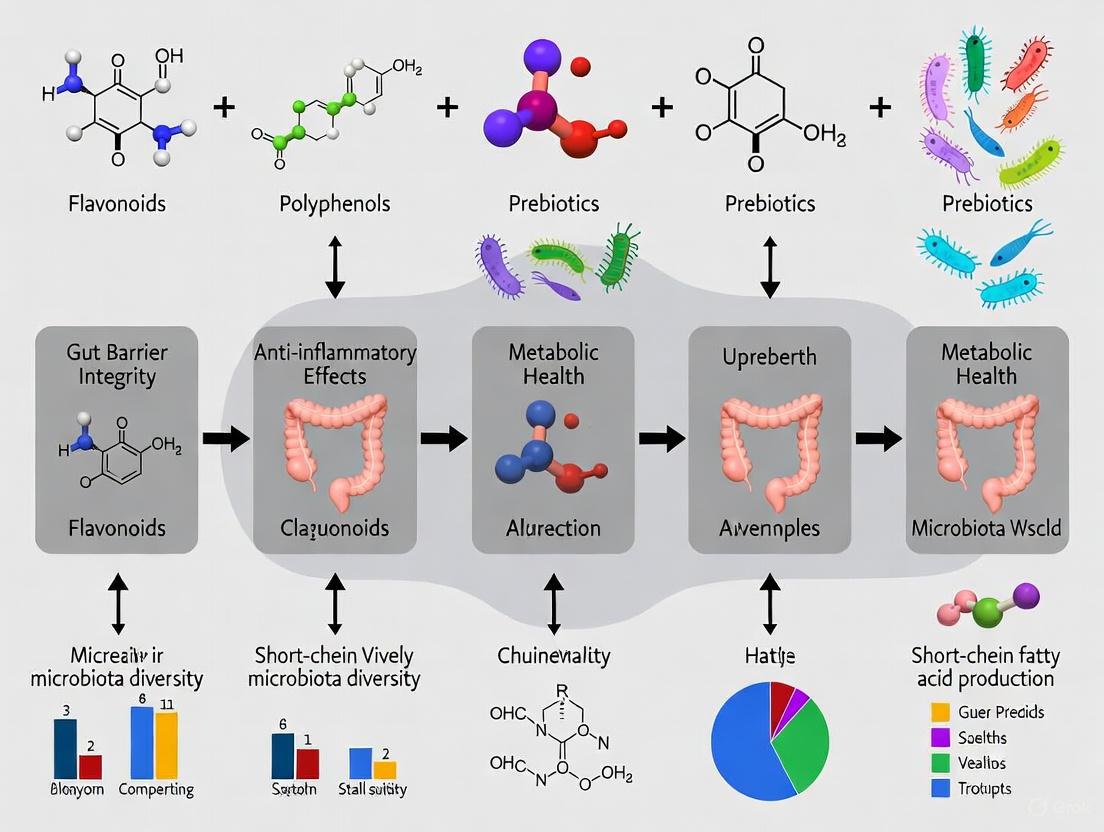

Diagram 1: Bidirectional Interaction Between Flavonoids and Gut Microbiota. This diagram illustrates how dietary flavonoids interact with gut microbiota, leading to the production of bioactive metabolites and modulation of microbial communities, ultimately influencing host health.

Dietary Fibers

Definition and Classification

Dietary fiber encompasses carbohydrate polymers with ten or more monomeric units that are resistant to hydrolysis by human endogenous enzymes and absorption in the small intestine [6]. This definition has been expanded to include indigestible oligosaccharides with 3-9 monomeric units, recognizing their similar physiological effects [6]. The traditional binary classification of soluble versus insoluble fiber is increasingly recognized as insufficient for predicting physiological effects, leading to proposals for more comprehensive frameworks that consider additional properties such as backbone structure, water-holding capacity, structural charge, fiber matrix, and fermentation rate [7].

Based on physiological properties and monomeric unit polymerization, dietary fibers are classified into three main types:

- Nonstarch Polysaccharides (NSPs): Include cellulose, hemicellulose, pectins, inulin, and various hydrocolloids with monomeric units ≥10 [6].

- Resistant Starches (RS): Classified into RS1 (physically inaccessible), RS2 (ungelatinized granular starch), RS3 (retrograded starch), RS4 (chemically modified), and RS5 (amylose-lipid complex) [6].

- Resistant Oligosaccharides (ROS): Include fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), and xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS) with 3-9 monomeric units [6].

Fermentation by Gut Microbiota and Health Implications

Dietary fibers escape digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and undergo fermentation by colonic microbiota, producing beneficial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate [6]. The extent and rate of fermentation depend on fiber characteristics including degree of polymerization, particle size, solubility, and viscosity [6]. Fibers with low polymerization degrees are degraded more rapidly, while soluble, viscous fibers exhibit slower fermentation patterns [6].

The specific microbial metabolism of dietary fibers depends on the presence of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), primarily glycoside hydrolases (GHs) and polysaccharide lyases (PLs), which vary across bacterial taxa [6]. This fiber-specific fermentation leads to selective stimulation of beneficial microbes, contributing to host health through multiple mechanisms:

- SCFA Production: Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, propionate regulates gluconeogenesis and satiety, and acetate influences cholesterol metabolism and lipogenesis.

- Microbial Diversity: Fiber fermentation promotes microbial richness and functional diversity, associated with improved metabolic health.

- Barrier Function: SCFAs enhance intestinal barrier integrity through upregulation of tight junction proteins.

- Immunomodulation: Fiber-derived metabolites regulate immune cell function and inflammatory responses.

Global dietary fiber intake ranges from 15-26 g/day, generally below recommended levels of 20-35 g/day [6]. This "fiber gap" has significant implications for gut microbiota composition and function, contributing to the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders [6].

Table 4: Dietary Fiber Classification, Sources, and Microbial Fermentation Characteristics

| Fiber Type | Subtypes & Examples | Primary Food Sources | Fermentation Characteristics | Primary Health Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonstarch Polysaccharides | Cellulose, Hemicellulose, Pectins, Inulin | Whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes | Varies from slow (cellulose) to rapid (inulin) fermentation | Stool bulking, SCFA production, prebiotic effects |

| Resistant Starches | RS1-RS5 (based on structure and source) | Legumes, unripe bananas, cooked and cooled potatoes, whole grains | Generally slow to moderate fermentation | Butyrate production, improved insulin sensitivity, enhanced satiety |

| Resistant Oligosaccharides | FOS, GOS, XOS | Chicory root, onions, leeks, asparagus, soybeans | Rapid and selective fermentation | Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, enhanced mineral absorption |

Carotenoids

Chemistry and Classification

Carotenoids are isoprenoid polyenes comprising approximately 750 naturally occurring pigments synthesized by plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria [8]. Their structure consists of isoprene (C5) units connected head-to-tail, forming symmetrical molecules typically containing 40 carbon atoms (tetraterpenoids) [9]. The extensive system of conjugated double bonds in the polyene chain is responsible for their characteristic yellow, orange, and red colors and their ability to absorb light in the UV-visible spectrum [9].

Carotenoids are broadly classified into two main categories:

- Carotenes: Hydrocarbon carotenoids without oxygen atoms (e.g., β-carotene, α-carotene, lycopene).

- Xanthophylls: Oxygenated derivatives containing hydroxyl, methoxy, epoxy, keto, or carboxy functional groups (e.g., lutein, zeaxanthin, astaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin) [9] [8].

Carotenoids also differ in their terminal groups, which can be acyclic, monocyclic, or bicyclic. The most common dietary carotenoids include α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene [8]. Among these, α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin function as provitamin A carotenoids that can be converted by the body to retinol, whereas lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene lack provitamin A activity [8].

Absorption, Metabolism, and Microbial Interactions

Carotenoid absorption is a complex process that requires release from the food matrix and incorporation into mixed micelles in the presence of dietary fat (minimum 3-5 g per meal) [8]. Food processing and cooking enhance carotenoid bioavailability by disrupting the food matrix [8]. Within enterocytes, carotenoids are absorbed via both passive diffusion and active transport through membrane transporters including Scavenger Receptor-class B type I (SR-BI), Cluster Determinant 36 (CD36), and Niemann-Pick C1 like intracellular transporter 1 (NPC1L1) [8].

Metabolic fate within enterocytes differs between provitamin A and nonprovitamin A carotenoids:

- Provitamin A Carotenoids: May be cleaved by β-carotene 15,15'-oxygenase 1 (BCO1) to produce retinal, which is further converted to retinol or retinoic acid, or by β-carotene 9',10'-oxygenase 2 (BCO2) to produce apocarotenals [8].

- Nonprovitamin A Carotenoids: Primarily cleaved by BCO2 [8].

The conversion efficiency of provitamin A carotenoids to retinol is influenced by vitamin A status, regulated through the intestine-specific homeobox (ISX) transcription factor that modulates expression of SR-BI and BCO1 [8]. Genetic polymorphisms in genes involved in carotenoid absorption, transport, and metabolism contribute to substantial interindividual variability in carotenoid status [8].

While carotenoid metabolism has traditionally been viewed as a host-centric process, emerging evidence indicates significant roles for gut microbiota in carotenoid biotransformation. Microbial enzymes may cleave carotenoids, producing bioactive metabolites such as apocarotenoids, and modulate carotenoid absorption efficiency through interactions with host absorption pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Carotenoid Analysis

Extraction Methods

Carotenoid extraction requires careful optimization due to their susceptibility to degradation during processing:

- Solvent Selection: Nonpolar solvents (hexane, petroleum ether) for carotenes; polar solvents (acetone, ethanol, methanol) for xanthophylls [9]. Ethanol and acetone are preferred for algal samples with high water content [9].

- Cell Disruption: Mechanical methods (homogenization, grinding) or enzymatic approaches to facilitate carotenoid release [9].

- Advanced Techniques: Microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasound-assisted extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, and pressurized liquid extraction improve efficiency and reduce solvent use [9].

- Saponification: Alkaline hydrolysis removes chlorophylls, lipids, and esters that interfere with analysis, though it should be omitted for alkali-sensitive carotenoids like astaxanthin and fucoxanthin [9].

Analysis and Quantification

- Spectrophotometric Methods: UV/Vis spectrophotometry for rapid determination of total carotenoid content based on specific absorption maxima [9].

- Chromatographic Techniques: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV/Vis or mass spectrometric detection for separation and quantification of individual carotenoids [9].

- Additional Techniques: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for structural elucidation [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Research

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol/Acetone with Acid Modifiers | Polyphenol and Flavonoid Extraction | Solvent system for efficient extraction of various phenolic compounds | Acid modifiers (formic/acetic acid) improve stability and recovery of acidic phenolics [1] |

| Hexane/Ethanol Solvent Systems | Carotenoid Extraction | Sequential extraction of nonpolar and polar carotenoids | Hexane for carotenes; ethanol for xanthophylls; consider safety and environmental impact [9] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Total Phenolic Content Assay | Oxidizing agent for colorimetric quantification of phenolics | Results expressed as gallic acid equivalents; interference from reducing agents [1] |

| DPPH/ABTS+ Radicals | Antioxidant Capacity Assessment | Stable radicals for measuring free radical scavenging activity | Results expressed as Trolox equivalents; different mechanisms of action [1] |

| β-Glucosidase Enzymes | Flavonoid Bioavailability Studies | Simulates intestinal deconjugation of flavonoid glycosides | Critical for assessing bioaccessibility; microbial sources often used [4] |

| Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes) | Dietary Fiber Characterization | Specific enzymes for fiber structure analysis | Glycoside hydrolases (GHs) and polysaccharide lyases (PLs) for fiber degradation studies [6] |

| Sodium/ Potassium Hydroxide in Methanol | Carotenoid Saponification | Alkaline hydrolysis for removal of interfering compounds | Omit for alkali-sensitive carotenoids; potential degradation issues [9] |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample Clean-up | Purification and concentration of analytes prior to analysis | Removes interfering compounds; improves chromatographic performance [1] |

Advanced Methodological Approaches

In Vitro Fermentation Models

- Batch Culture Systems: Simple, high-throughput screening of microbial metabolism using fecal inocula in anaerobic conditions.

- Continuous Culture Models: Multi-stage systems (e.g., TIM-2, SHIME) simulating different colonic regions with more physiological relevance.

- Analytical Endpoints: SCFA analysis by GC-FID, microbial composition by 16S rRNA sequencing, metabolite profiling by LC-MS.

Omics Technologies

- Metagenomics: Reveals microbial community structure and genetic potential for bioactive compound metabolism.

- Metatranscriptomics: Identifies actively expressed genes involved in compound biotransformation.

- Metabolomics: Comprehensive profiling of microbial metabolites derived from dietary bioactives.

- Integration: Multi-omics approaches provide systems-level understanding of diet-microbiota-host interactions.

The intricate relationships between dietary bioactive compounds (polyphenols, flavonoids, dietary fibers, and carotenoids) and gut microbiota represent a frontier in nutritional science with profound implications for human health and disease management. The structural diversity of these compounds dictates their bioavailability, microbial metabolism, and ultimate physiological effects. As research in this field advances, sophisticated analytical approaches and model systems are enabling deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying these interactions. Future research directions should focus on personalized nutrition approaches that account for interindividual variability in microbiota composition and function, the development of targeted delivery systems to enhance bioactive compound efficacy, and the integration of multi-omics technologies to unravel the complex networks connecting diet, microbiota, and host physiology. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the fundamental concepts and methodologies presented in this guide provides a critical foundation for advancing this rapidly evolving field and developing evidence-based nutritional interventions for gut microbiota modulation.

The human gut microbiota, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotes, encodes over 3 million genes—far exceeding the human genome. This review delineates the composition and function of the gut microbiota, framing it as a critical metabolic organ that biotransforms dietary components, synthesizes essential metabolites, and modulates host physiology. Within the context of bioactive compounds research, we explore how diet-derived phytochemicals, prebiotics, and other bioactives interact with microbial communities to influence host health. We present standardized methodologies for microbial profiling, quantitative data on core microbial associations with disease, and visualizations of key metabolic pathways. This synthesis aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with advanced tools and frameworks for leveraging gut microbiota modulation in therapeutic interventions.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a dynamic community of trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota. This community encodes a metabolic repertoire vastly exceeding human hepatic capabilities, with its gene set—the gut microbiome—estimated at approximately 3 million genes, 150 times larger than the human genome [10]. This "second genome" functions as an invisible organ [11], essential for nutrient extraction, vitamin synthesis, and metabolic regulation. The microbiota's composition remains relatively stable yet exhibits plasticity in response to dietary bioactive compounds, medications, and other environmental factors [12] [11]. Its metabolic output, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), vitamins, and bile acid derivatives, profoundly influences local and systemic host physiology through intricate gut-organ axes, including the gut-brain, gut-liver, and gut-immune pathways [13] [12].

Composition and Core Functions of the Gut Microbiota

Microbial Composition and Enterotypes

The healthy human gut microbiota is dominated by six major bacterial phyla: Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes), Bacteroidota (formerly Bacteroidetes), Pseudomonadota (Proteobacteria), Actinomycetota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Fusobacteria [12]. Bacteroidota and Bacillota typically constitute the majority of the microbial community. At the species level, certain microbial members are consistently prevalent and abundant across populations, forming a core microbiota believed to be crucial for maintaining gut homeostasis [14]. Enterotype analysis often classifies the human gut microbiome into distinct community types, frequently characterized by dominance of either Bacteroides or Prevotella [15].

Table 1: Core Gut Microbiota and Key Functional Roles

| Microbial Taxon | Category | Relative Abundance/Prevalence | Primary Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phocaeicola vulgatus [15] | Bacterial Species | High Abundance | Polysaccharide fermentation |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [16] | Bacterial Species | Prevalent & Abundant | Butyrate production, anti-inflammatory |

| Akkermansia muciniphila [13] [16] | Bacterial Species | Prevalent | Mucin degradation, gut barrier integrity |

| Roseburia spp. [10] [16] | Bacterial Genus | ~2.7% average abundance [15] | Butyrate production from dietary fiber |

| Bifidobacterium [16] | Bacterial Genus | Variable | SCFA production, pathogen exclusion |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) [17] | Functional Group | Variable | Bioactive metabolite production (e.g., organic acids) |

Central Metabolic Functions

The gut microbiota performs fundamental metabolic processes essential for host health:

- Nutrient Fermentation: Saccharolytic fermentation of undigested dietary carbohydrates, primarily dietary fibers, produces SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) and gases [10].

- Biosynthesis: The microbiota synthesizes essential vitamins (e.g., Vitamin K, B vitamins) and amino acids for the host [12] [16].

- Biotransformation: It metabolizes host-derived compounds, such as bile acids, and dietary xenobiotics, including plant polyphenols, significantly altering their bioavailability and bioactivity [18] [11].

The Gut Microbiota as a Metabolic Organ

Metabolism of Dietary Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds

The gut microbiota acts as a critical interface for the metabolism of dietary components, particularly those inaccessible to human digestive enzymes.

Carbohydrate Metabolism: The fermentation of microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) is a primary metabolic function. SCFAs, the key fermentation products, serve multiple roles: butyrate is the primary energy source for colonocytes and has anti-cancer properties, propionate regulates gluconeogenesis and satiety, and acetate is involved in cholesterol metabolism and lipogenesis [10]. The specificity of SCFA production is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: Primary Bacterial Metabolites and Their Systemic Effects

| Metabolite | Primary Producers | Key Physiological Functions | Impact of Bioactive Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp., Eubacterium rectale [10] | Colonocyte energy source, anti-inflammatory, HDAC inhibition [10] [16] | Prebiotics (e.g., resistant starch) increase butyrate producers [16] |

| Propionate | Bacteroides species, Negativicutes [10] | Hepatic gluconeogenesis, satiety signaling [10] | Influenced by dietary fiber composition |

| Acetate | Many bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium) [10] | Cholesterol metabolism, lipogenesis, cross-feeding [10] | Produced by fermentative LAB [17] |

| Equol | Adlercreutzia equolifaciens [16] | Antioxidant, estrogenic properties | Derived from soy isoflavone metabolism by specific bacteria |

Protein Metabolism: When carbohydrate availability is low, gut bacteria can utilize proteins and amino acids for energy, producing metabolites like branched-chain fatty acids, ammonia, and phenolic compounds, which can be detrimental in high concentrations [10].

Metabolism of Bioactive Compounds: Dietary bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols from berries and cocoa, rely extensively on gut microbiota for activation. These compounds are often metabolized into more bioavailable forms by bacterial enzymes, enhancing their health benefits [18] [16]. For instance, specific bacteria like Adlercreutzia equolifaciens convert soy isoflavones into equol, a potent antioxidant [16]. Furthermore, microalgae-derived bioactive compounds (polysaccharides, peptides) have emerged as promising modulators of gut microbial composition and function [19].

Key Metabolic Pathways and Interactions

The following diagram illustrates the central metabolic pathways through which the gut microbiota processes dietary inputs and generates bioactive metabolites that influence host health.

Methodologies for Gut Microbiota Research

Profiling and Quantification Techniques

Advanced molecular techniques are essential for characterizing the gut microbiota's composition and functional potential.

- Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS): This discovery-oriented approach allows for comprehensive analysis of all microbial genes in a sample, enabling taxonomic profiling and functional inference [14] [15]. A large-scale meta-analysis of 6,314 metagenomes demonstrated its power in identifying disease-associated microbial signatures across multiple studies [15]. However, mNGS is costly, requires sophisticated bioinformatics, and lacks standardization [14].

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): For targeted, rapid quantification of specific bacterial taxa, qPCR is a highly effective method. A recently developed panel of 45 qPCR assays targeting gut core microbes allows for absolute quantification with high sensitivity (limit of detection: 0.1-1.0 pg/µL DNA) and strong correlation with mNGS results (Pearson’s r = 0.87) [14]. This method is ideal for tracking dynamic changes of key microbes in individuals over time [14].

Experimental Workflow for Microbiota Analysis

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for a gut microbiota study, from sample collection to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gut Microbiota Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [14] | High-quality genomic DNA extraction from fecal samples or bacterial cultures. | Standardized DNA preparation for downstream qPCR or NGS. |

| Species-Specific qPCR Primers [14] | Quantitative detection and enumeration of specific gut bacterial taxa (e.g., core microbes). | Tracking abundance of A. muciniphila or F. prausnitzii in intervention studies. |

| MetaPhlAn4 Database [15] | Reference database for taxonomic profiling of metagenomic sequencing data. | Identifying microbial community composition from mNGS data in population studies. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix [14] | Fluorescent dye for real-time detection of amplified DNA in qPCR assays. | Enabling quantification of target bacteria in qPCR reactions. |

| Gnotobiotic Mouse Models [13] [14] | Animals with defined microbiota, allowing for causal studies of microbial function. | Investigating the impact of a defined human microbial community on host physiology. |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Interventions

The recognition of the gut microbiota as a metabolic organ has profound implications for pharmacology and drug development. The microbiota can directly and indirectly modulate drug function by affecting drug absorption, metabolism, bioavailability, and toxicity—a phenomenon termed "pharmacomicrobiomics" [11]. Key mechanisms include:

- Biotransformation of Drugs: Gut bacterial enzymes can chemically modify drugs, altering their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [11].

- Modulation of Host Metabolism: Microbiota-derived metabolites like SCFAs can influence the expression of host drug-metabolizing enzymes in the liver [11].

- Impact on Mucosal Barrier: The microbiota affects the integrity of the gut mucosal barrier, which in turn influences oral drug absorption [11].

These interactions present both challenges and opportunities. Understanding an individual's gut microbiota composition could inform personalized drug dosing and selection. Furthermore, targeted modulation of the gut microbiota using prebiotics (e.g., specific fibers, microalgae-derived compounds [19] [16]), probiotics (e.g., specific lactic acid bacteria strains [17]), and faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) [13] represents a novel therapeutic avenue for managing metabolic, inflammatory, and other microbiota-associated disorders.

The human gut microbiota, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa, plays an indispensable role in maintaining host health by influencing metabolism, immune function, and disease protection [20]. The composition and function of this microbial community are profoundly shaped by various modifiable factors, with diet being the most significant [20]. Within our diet, bioactive compounds—non-nutrient food constituents with biological activity—serve as critical mediators of the host-microbiota interface [20]. These compounds, including polyphenols, dietary fibers, and antimicrobial phytochemicals, exert profound effects on microbial ecology through multifaceted mechanisms. This whitepaper delineates the direct and indirect pathways through which dietary bioactives modulate gut microbial communities, promoting beneficial bacteria while inhibiting pathogenic species, with implications for therapeutic development and clinical practice. Understanding these mechanisms provides a scientific foundation for developing targeted nutritional interventions to maintain gut eubiosis and prevent dysbiosis-associated diseases.

Direct Mechanisms of Microbial Modulation

Bioactive compounds directly influence gut microbiota through specific biochemical interactions that either enhance beneficial bacterial populations or directly inhibit pathogens.

Direct Antimicrobial Action Against Pathogens

Many plant-derived bioactive compounds exert direct antibacterial effects against pathogenic bacteria through well-characterized mechanisms (Table 1). These compounds target fundamental cellular structures and processes essential for bacterial survival and virulence.

Table 1: Direct Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Selected Bioactive Compounds

| Bioactive Compound | Source | Target Pathogens | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catechins (e.g., EGCG) | Green tea, cocoa | E. coli, Salmonella spp. | Inhibits bacterial DNA gyrase and dihydrofolate reductase [20] |

| Bacteriocins | Probiotic bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus lactis) | Various intestinal pathogens | Forms pores in bacterial membranes; acts as signaling molecules [21] |

| Allicin | Garlic | E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus | Inhibits biofilm formation; disrupts cellular functions [22] |

| Chitosan | Shellfish exoskeletons | E. coli, Salmonella typhi | Disrupts cell membrane integrity [23] |

| Flavonoids | Various plants | Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli | Disrupts bacterial cell membranes and inhibits biofilm formation [22] |

| Alkaloids (e.g., Berberine) | Various plants | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) | Targets nucleic acid synthesis and compromises cell wall integrity [22] |

| Terpenes (e.g., Carvacrol, Thymol) | Oregano, thyme | Foodborne pathogens | Disrupts cellular functions and enhances membrane permeability [22] |

Polyphenols such as catechins from green tea inhibit bacterial enzymes critical for DNA replication and folate synthesis, effectively suppressing pathogenic bacterial growth [20]. Similarly, bacteriocins—ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by probiotic bacteria—create pores in bacterial membranes, leading to cell death [21]. Plant antimicrobials including flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenes disrupt cell membrane integrity, impede cell wall and protein synthesis, and prevent biofilm formation, ultimately causing bacterial cell death [22]. These direct antimicrobial properties provide a mechanistic basis for using bioactives as natural alternatives to synthetic antimicrobials, particularly in addressing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [22].

Selective Promotion of Beneficial Bacteria

Bioactive compounds selectively enhance beneficial bacterial populations through prebiotic effects and metabolic support:

Prebiotic Fibers and Oligosaccharides: Non-digestible dietary components like inulin, oligosaccharides, and d-Tagatose selectively stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus [24] [25]. These compounds resist host digestion and serve as fermentable substrates for commensal bacteria, promoting their proliferation and metabolic activity [24].

Polyphenol Metabolism: Many dietary polyphenols have low bioavailability in the upper gastrointestinal tract, with 90-95% reaching the colon intact [20]. Gut microbiota metabolize these complex polyphenols into bioavailable metabolites through reactions including dehydroxylation, decarboxylation, and aromatic ring cleavage [20]. This metabolic relationship creates a symbiotic association where certain bacterial taxa obtain energy while generating beneficial metabolites for the host.

Synbiotic Combinations: Strategic combinations of prebiotics and probiotics demonstrate synergistic effects on gut microbiota. Prebiotics provide specialized substrates for probiotics, enhancing their survival and functionality within the competitive gut environment [24].

The following diagram illustrates the direct mechanisms through which bioactive compounds modulate gut microbiota:

Indirect Mechanisms of Microbial Modulation

Beyond direct antimicrobial effects, bioactives influence gut microbiota through complex host-mediated pathways that alter the gut environment and immune responses.

Enhancement of Gut Barrier Function

Bioactive compounds strengthen intestinal barrier integrity through multiple mechanisms:

Tight Junction Protein Regulation: Bioactive compounds such as hesperidin from citrus fruits enhance the expression of tight junction proteins including occludin and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in intestinal epithelial cells [20]. This fortification of the epithelial barrier reduces bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation.

Mucosal Barrier Support: Compounds like chitosan have been shown to improve intestinal mucosal barrier function and regulate the expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and tight junction proteins in colitis models [25].

Immune-Mediated Barrier Protection: By modulating host immune responses, bioactives create an intestinal environment less conducive to pathogen colonization while supporting commensal species.

Immunomodulation

The intestinal immune system maintains a delicate balance between tolerance to commensals and defense against pathogens. Bioactive compounds modulate this balance through several pathways:

Cytokine Regulation: Compounds like quercetin reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production by modulating NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cells [20]. Similarly, pistachio consumption reduces protein levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in serum and adipose tissue [25].

Immune Cell Differentiation: Certain polyphenols influence dendritic cell function and promote regulatory T cell differentiation through increased interleukin-10 (IL-10) production, fostering an anti-inflammatory environment [20].

Innate Immune Activation: Some microbial metabolites derived from bioactive compounds directly influence pattern recognition receptors on immune cells, fine-tuning inflammatory responses.

Metabolic Byproducts and Signaling Molecules

Beneficial gut bacteria ferment dietary bioactives to produce metabolites that profoundly influence host physiology and microbial ecology (Table 2).

Table 2: Key Microbial Metabolites Derived from Bioactive Compounds and Their Functions

| Metabolite | Producing Bacteria | Health Effects | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (Butyrate, Propionate, Acetate) | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp., Bifidobacterium | Energy for colonocytes, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor [21] | Lower colonic pH, inhibit pathogens, enhance barrier function [20] |

| Bile Acid Derivatives | Various gut microbes | Lipid digestion, glucose metabolism [26] | Activation of nuclear receptors (FXR, TGR5) [20] |

| Tryptophan Metabolites | Multiple species | Immune regulation, gut barrier maintenance [20] | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation [20] |

| Lactic Acid | Lactobacillus species | Lowers pH, inhibits pathogens [21] | Creates unfavorable environment for acid-sensitive pathogens [21] |

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—including acetate, propionate, and butyrate—are produced through bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starches [21]. These metabolites lower colonic pH, inhibiting pH-sensitive pathogens while promoting acid-tolerant commensals [20]. Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes and exhibits anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties [21]. Other microbial metabolites such as bile acid derivatives and tryptophan intermediates influence host metabolism and immune function through specific receptor interactions [20].

The following diagram illustrates the indirect pathways through which bioactives influence gut microbiota:

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Investigating bioactive-microbiota interactions requires sophisticated experimental models and analytical techniques.

In Vitro Screening Methods

Initial assessment of antimicrobial activity typically employs standardized in vitro assays:

Disk Diffusion Method: This classic technique involves impregnating filter paper disks with test compounds, placing them on agar plates inoculated with target pathogens, and measuring inhibition zones after incubation. Studies testing chitosan, EGCG, and garlic against E. coli and Salmonella typhi used this method with 50μL of 0.5%, 1%, and 2% solutions applied to 8mm discs [23].

Broth Dilution Methods: Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations using serial dilutions of bioactive compounds in liquid culture provide quantitative data on antimicrobial potency.

Biofilm Assays: Specific assays quantify inhibition of biofilm formation—a key virulence mechanism—addressing challenges in food processing and clinical infections [22].

In Vivo and Ex Vivo Models

Animal models and human studies provide physiological context for bioactive effects:

Animal Studies: Rodent models allow investigation of complex host-microbe interactions. For example, studies with pistachio consumption demonstrated reduced Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and increased abundance of beneficial genera like Parabacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Anaeroplasma in mice [25].

Human Intervention Trials: Randomized controlled trials provide clinically relevant data. A study with orange juice consumption for two months significantly increased anaerobic bacteria and lactobacilli in healthy human subjects [20].

Ex Vivo Fecal Cultures: In vitro fermentation systems inoculated with human fecal microbiota simulate colonic conditions. Studies with different inulin-type fructans demonstrated prebiotic-specific increases in Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibacterium [25].

Analytical Methods

Advanced analytical techniques characterize microbial community changes and metabolic outputs:

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Profiling bacterial communities before and after interventions identifies taxonomic shifts. Chemogenetic activation of hypothalamic POMC neurons revealed rapid, anatomically-specific changes in duodenal microbiota composition within 2-4 hours [26].

Metabolomics: Mass spectrometry-based profiling of microbial metabolites (SCFAs, bile acids, tryptophan derivatives) in feces, serum, and tissues connects microbial changes to functional outcomes [20].

Transcriptomics and Proteomics: RNA sequencing and protein analysis identify host pathways affected by bioactive-microbiota interactions, such as NF-κB and MAPK signaling in inflammation [20].

The following workflow represents a standardized experimental approach for evaluating bioactive effects on gut microbiota:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table provides essential research tools for investigating bioactive-microbiota interactions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bioactive-Microbiota Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebiotics | Inulin, 1-kestose, Actilight, galactooligosaccharides [25] | Prebiotic specificity studies; microbial enrichment | Selective stimulation of beneficial bacteria; SCFA production |

| Probiotic Strains | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Saccharomyces boulardii [21] | Mechanistic studies; therapeutic applications | Direct introduction of beneficial species; bacteriocin production |

| Antimicrobial Compounds | Chitosan, EGCG, allicin, bacteriocins [23] [22] | Pathogen inhibition assays; biofilm studies | Membrane disruption; enzyme inhibition; biofilm prevention |

| Culture Media | Nutrient agar, Luria-Bertani medium, specialized fermentation media [23] | Microbial cultivation; fermentation studies | Support bacterial growth; simulate gut conditions |

| Analytical Standards | SCFA mixes, bile acids, phenolic metabolites [20] | Metabolite quantification; method validation | Calibration; identification of microbial metabolites |

| Molecular Biology Kits | 16S rRNA sequencing kits, RNA isolation kits, cytokine assays [26] [25] | Community analysis; host response measurement | Taxonomic profiling; gene expression; inflammation assessment |

Bioactive compounds modulate gut microbiota through an intricate network of direct and indirect mechanisms that collectively shape microbial ecology and function. Direct mechanisms include selective antimicrobial activity against pathogens and nutritional support for beneficial species, while indirect pathways involve enhancement of gut barrier function, immunomodulation, and production of microbial metabolites that influence host physiology. The therapeutic potential of these compounds is particularly relevant in addressing modern health challenges including antimicrobial resistance, metabolic diseases, and inflammation-related disorders. Future research should prioritize human clinical trials, personalized nutrition approaches accounting for interindividual microbiota variability, and systematic investigation of synergistic effects between different bioactive compounds. As our understanding of these mechanisms deepens, targeted modulation of gut microbiota through dietary bioactives represents a promising frontier in nutritional science and therapeutic development.

The human gut microbiota functions as a metabolic organ, converting dietary components into a diverse array of bioactive molecules that profoundly influence host physiology and disease susceptibility. Among these microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids (BAs), and tryptophan derivatives represent three critical classes that mediate host-microbe communication through specialized molecular pathways [27] [28]. These microbiota-dependent metabolites (MDMs) serve as essential signaling molecules at the interface between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, regulating fundamental processes including immune cell differentiation, epithelial barrier integrity, metabolic homeostasis, and neuroendocrine signaling [27]. The structural diversity of these metabolites enables them to engage specific host receptors—including G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), nuclear receptors, and ligand-activated transcription factors—thereby orchestrating complex transcriptional and epigenetic programs across tissues [28]. This technical guide comprehensively details the biosynthetic pathways, molecular mechanisms, and research methodologies for these critical microbial metabolites, providing a foundational resource for advancing targeted therapeutic interventions in human health and disease.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Production and Biosynthesis

Short-chain fatty acids are fatty acids with 1-6 carbon atoms, primarily produced from microbial fermentation of undigested dietary fibers in the colon and cecum [27]. The three most abundant SCFAs in the intestine are acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), which typically occur in a molar ratio of approximately 3:1:1 in healthy individuals [28]. Their production exhibits significant regional variation within the gastrointestinal tract, with total SCFA concentration substantially higher in the colon (ranging from 80±11 mmol/kg in the descending colon to 131±9 mmol/kg in the cecum) compared to the terminal ileum (13±6 mmol/kg) [27]. Following production, SCFAs are absorbed into the bloodstream via passive diffusion or carrier-mediated transport (primarily through monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and SMCT1), though significant hepatic metabolism ensures only a small fraction reaches peripheral tissues [27]. Plasma concentrations in human peripheral venous blood are estimated at 19–146 μM for acetate, 1–13 μM for propionate, and 1–12 μM for butyrate [27].

SCFA biosynthesis pathways demonstrate notable microbial species specificity:

- Acetate is produced from pyruvate via acetyl-CoA or through the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway by various intestinal bacteria including Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides spp., and Bifidobacterium spp. [27].

- Propionate is synthesized through three distinct pathways: succinate, acrylate, and propanediol pathways by specific microorganisms like Bacteroides spp. and Salmonella spp. [27].

- Butyrate is formed from two acetyl-CoA molecules through two enzymatic routes involving bacteria such as Anaerostipes spp., Roseburia spp., and Coprococcus eutactus [27] [28].

The intestinal pH plays a critical regulatory role in SCFA synthesis by shaping microbial composition and modulating enzyme activity. For instance, at pH 5.5, butyrate-producing bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii become dominant, whereas at pH 6.5, genera including Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium preferentially produce acetate and propionate [28].

Mechanisms of Action and Immunomodulatory Roles

SCFAs exert their biological effects through three primary mechanisms: (1) serving as cellular energy substrates; (2) inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs); and (3) activating G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) including GPR41 (FFAR3), GPR43 (FFAR2), and GPR109A (HCAR2) [27] [28]. While early research suggested that SCFA-sensing GPCRs were predominantly expressed in innate immune populations (macrophages, dendritic cells, and intestinal Tregs) with minimal expression in conventional T lymphocytes, subsequent studies have demonstrated functional GPCR expression on differentiated effector T cells, revealing direct SCFA-GPCR signaling crosstalk [27].

The immunomodulatory effects of SCFAs include:

- Enhancing regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation and function through HDAC inhibition and GPR43 activation [28].

- Reinforcing intestinal barrier integrity via upregulation of tight junction proteins [29] [28].

- Modulating inflammatory responses in macrophages and dendritic cells through HDAC inhibition and GPCR signaling [27] [28].

- Enhancing CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity and altering T cell memory potential [27].

Table 1: SCFA Concentrations in Biological Compartments

| SCFA | Colonic Concentration (mmol/kg) | Plasma Concentration (μM) | Primary Producing Bacteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | 70-140 (proximal colon) [28] | 19-146 [27] | Akkermansia muciniphila, Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium spp. [27] |

| Propionate | 20-70 (distal colon) [28] | 1-13 [27] | Bacteroides spp., Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens, Veillonella spp. [27] [28] |

| Butyrate | 20-70 (distal colon) [28] | 1-12 [27] | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Anaerostipes spp., Roseburia spp., Coprococcus eutactus [27] [28] |

Figure 1: SCFA Biosynthesis and Immunomodulatory Mechanisms

Bile Acids

Production and Microbial Modification

Bile acids are synthesized by hepatocytes through cholesterol oxidation, resulting in primary bile acids including cholate (CA) and chenodeoxycholate (CDCA) [27]. These primary BAs are conjugated with glycine or taurine in the liver, rendering them more hydrophilic, and subsequently secreted into the intestinal lumen to facilitate nutrient digestion, transport, and absorption [27] [28]. Approximately 95% of conjugated primary BAs are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum and returned to the liver via enterohepatic circulation, while the remaining 5% undergo extensive microbial transformation in the cecum and colon into secondary bile acids [27].

Microbial transformation of BAs involves five key reactions:

- Deconjugation: The initial and crucial step mediated by bile salt hydrolases (BSHs) found in many bacteria including Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus [27] [28].

- Dehydroxylation: Primarily carried out by anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium, essential for converting primary BAs into secondary BAs like deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA) [27].

- Oxidation: Conversion of BAs to oxo-BAs mediated by position-specific hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (HSDHs) [27].

- Epimerization: Requires coordinated effort of different HSDHs (e.g., 7α-HSDH and 7β-HSDH) [27].

- Re-conjugation: Recently identified fifth microbial modification producing novel BA amidates independent of glycine or taurine, such as phenylalanocholic acid and tyrosocholic acid [27].

Signaling Mechanisms and Biological Functions

BAs and their derivatives engage with specific receptors including the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), pregnane X receptor (PXR), vitamin D receptor (VDR), and G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GPBAR1, also known as TGR5) [27] [28]. Through these receptors, BAs regulate diverse physiological processes:

- Metabolic homeostasis: FXR activation regulates glucose and lipid metabolism [28] [30].

- Immune modulation: Secondary BAs influence the immune phenotype of hepatic Kupffer cells and modulate inflammasome activation through FXR and TGR5 signaling [28].

- Gastrointestinal function: BAs impact gut barrier function, motility, and mucosal immunity [30].

- Carcinogenesis: Increased levels of certain secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid (DCA), are associated with genotoxic stress and pro-oncogenic signaling cascades in gastrointestinal cancers [28] [31].

Table 2: Primary and Secondary Bile Acids: Production and Receptors

| Bile Acid Type | Examples | Production/Modification | Primary Receptors | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary BAs | Cholate (CA), Chenodeoxycholate (CDCA) | Synthesized in liver from cholesterol [27] | FXR, PXR [27] [28] | Nutrient digestion and absorption [27] |

| Secondary BAs | Deoxycholic acid (DCA), Lithocholic acid (LCA) | Microbial dehydroxylation of primary BAs [27] | FXR, TGR5, VDR [27] [28] | Immune modulation, metabolic regulation [28] |

| Re-conjugated BAs | Phenylalanocholic acid, Tyrosocholic acid | Microbial re-conjugation independent of glycine/taurine [27] | Not specified | Emerging roles in host signaling [27] |

Figure 2: Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling Pathways

Tryptophan Derivatives

Production and Biosynthetic Pathways

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid obtained from dietary protein that reaches the colon, where it undergoes extensive microbial metabolism into various bioactive indole derivatives [27] [32]. In the human body, tryptophan is metabolized via three main pathways: the kynurenine (Kyn) pathway, the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) pathway, and the indole pathway, with microorganisms primarily utilizing the indole pathway to generate various derivatives [27] [32].

Key microbial tryptophan metabolites and their producing organisms include:

- Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) and indole-3-lactic acid (ILA): Produced by Clostridium sporogenes (with the fldC subunit being indispensable for IPA biosynthesis) and Peptostreptococcus species including P. russellii, P. anaerobius, and P. stomatis [27].

- Indolealdehyde (IAld) and ILA: Generated by Lactobacillus species [27].

- Indoleacrylic acid (IA): Produced by Peptostreptococcus species [27].

- Kynurenine (Kyn) and serotonin: Some microorganisms can produce these metabolites and their downstream products such as 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) and 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-H-Kyn) [27].

The average serum concentrations of microbial indole derivatives are estimated to be 60-80 μM for IPA and indolepyruvic acid and 0-20 μM for IAA and ILA in mice [27]. In humans, mean concentrations in healthy adults have been reported as 227 ng/ml for IAA, 191.1 ng/ml for IPA, and 31.5 ng/ml for ILA [27].

Biological Activities and Health Implications

Tryptophan-derived metabolites function as bioactive compounds that facilitate communication between bacteria and the host mainly by binding to specific receptors like the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and pregnane X receptor (PXR) [27] [28] [32]. These interactions mediate diverse physiological effects:

- Mucosal defense enhancement: IPA enhances mucosal defense mechanisms through activation of the AhR-IL-22 signaling pathway [28].

- Immune regulation: Tryptophan metabolites help maintain the equilibrium between Tregs and Th17 cells, with insufficient AhR ligand availability increasing the risk of autoimmune disorders [28].

- Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities: Tryptamine and IPA demonstrate potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may protect against age-related diseases [32].

- Gut-brain axis modulation: Tryptophan metabolites serve as crucial mediators in gut-brain communication, influencing neuronal function and potentially affecting neuropsychiatric conditions [33] [32].

Table 3: Microbial Tryptophan Metabolites and Their Functions

| Metabolite | Producing Microbes | Primary Receptors | Concentrations | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) | Clostridium sporogenes, Peptostreptococcus spp. [27] | AhR, PXR [27] [28] | 191.1 ng/ml (human serum) [27] | Antioxidant, enhances mucosal defense [28] [32] |

| Indole-3-lactic acid (ILA) | Clostridium sporogenes, Lactobacillus spp. [27] | AhR [27] | 31.5 ng/ml (human serum) [27] | Immune modulation [27] |

| Indolealdehyde (IAld) | Lactobacillus spp. [27] | AhR [27] | Not specified | Mucosal immunity [27] |

| Kynurenine (Kyn) | Various microorganisms [27] | AhR [27] | Not specified | Immune regulation [27] |

Figure 3: Tryptophan Metabolism and Biological Functions

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Analytical Techniques for Metabolite Quantification

Accurate measurement of microbial metabolites requires sophisticated analytical platforms that can handle complex biological matrices while providing sufficient sensitivity and specificity:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Widely employed for SCFA analysis due to its ability to separate and quantify these volatile fatty acids [31]. Sample preparation typically involves acidification followed by liquid-liquid extraction or solid-phase microextraction.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): The preferred method for analyzing tryptophan derivatives and bile acids due to its superior sensitivity for semi-volatile and non-volatile metabolites [31]. Reverse-phase chromatography with C18 columns coupled to tandem mass spectrometry enables simultaneous quantification of multiple metabolite classes.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Useful for untargeted metabolite profiling and structural elucidation of novel microbial metabolites [31]. While less sensitive than MS-based methods, NMR provides complementary structural information without extensive sample preparation.

Genetic Manipulation of Microbial Producers

Elucidating the specific contributions of microbial genes to metabolite production requires targeted genetic approaches:

- CRISPR-Cas Systems: Enable precise gene knockouts in model gut bacteria such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Clostridium sporogenes to validate gene functions in SCFA and tryptophan derivative biosynthesis [27]. For example, the fldC subunit in C. sporogenes has been identified as indispensable for IPA biosynthesis through genetic approaches [27].

- Heterologous Expression: Biosynthetic genes from difficult-to-culture microbes can be expressed in model organisms like E. coli or Lactococcus lactis to confirm enzyme functions and reconstitute metabolic pathways [27].

In Vitro and Ex Vivo Model Systems

Several experimental models facilitate the study of host-microbe metabolic interactions:

- In vitro Bioreactors: Sophisticated continuous-culture systems that simulate different regions of the gastrointestinal tract, allowing controlled investigation of microbial metabolite production under varying environmental conditions [27].

- Intestinal Organoids: Three-dimensional structures derived from intestinal stem cells that recapitulate key aspects of intestinal epithelium physiology, enabling study of host-metabolite interactions in a human-derived system [30]. Filtered fecal supernatants from different donor populations can be applied to organoids to assess effects on enterocyte proliferation and maturation [30].

- Gnotobiotic Mouse Models: Germ-free animals colonized with defined microbial communities permit causal inference between specific microbes, their metabolites, and host phenotypes [30].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Metabolite Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Deuterated SCFAs (d3-acetate), Stable isotope-labeled tryptophan derivatives, Certified bile acid standards | Quantification via GC-MS/LC-MS, Method validation [31] |

| Recombinant Receptors | Human FXR, TGR5, AhR, GPR43 | Receptor-ligand binding assays, Signaling studies [27] [28] |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas systems for Bacteroides and Clostridium, Shuttle vectors for lactic acid bacteria | Microbial gene manipulation, Pathway engineering [27] |

| Cell-based Assays | Reporter cell lines (AhR-luciferase), Primary immune cell cultures, Intestinal organoids | Functional validation of immunomodulatory effects [27] [30] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | HDAC inhibitors (Trichostatin A), BSH inhibitors, HSDH inhibitors | Mechanistic studies of metabolite actions [27] [28] |

The intricate metabolic interplay between gut microbes and their human host represents a fundamental biological dialogue maintained through chemical signaling molecules. SCFAs, bile acids, and tryptophan derivatives exemplify how structurally diverse microbial metabolites engage specialized host receptor systems to regulate immunity, metabolism, and tissue homeostasis. Current research continues to unravel the complexity of these interactions, revealing novel microbial transformations—such as the recently discovered re-conjugation of bile acids—and clarifying the molecular mechanisms through which these metabolites influence health and disease [27]. Emerging technologies including spatial metabolomics, synthetic biology, and AI-driven predictive modeling are poised to accelerate discovery in this field, enabling the development of targeted therapeutic strategies that leverage the gut microbiome's metabolic potential [28]. Future research directions should focus on establishing comprehensive metabolite-receptor interaction networks, validating clinical biomarkers, and developing precision interventions that account for interindividual variation in microbial metabolic capacity. As our understanding of these critical microbial metabolites deepens, they offer promising avenues for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches across a spectrum of conditions including inflammatory disorders, metabolic diseases, cancer, and age-related pathologies.

The gastrointestinal tract represents a critical interface between the external environment and the internal milieu, with its integrity being paramount for systemic health. This whitepaper delineates the sophisticated structure of the gut barrier, its dynamic interplay with the commensal microbiota, and the subsequent priming of the host immune system. Within the context of bioactive compounds research, we examine how dietary and microbial-derived factors modulate these relationships. The document provides a detailed analysis of core gut microbiota constituents, standardized methodologies for assessing barrier integrity and immune responses, and visualizes key signaling pathways. Furthermore, we present a curated toolkit of research reagents and solutions to support experimental replication and innovation in the field of mucosal immunology and gut microbiome research.

The intestinal epithelium, a single-cell layer covering a surface of over 300 m², serves as a primary physical and immunological barrier [34]. It is constantly exposed to a vast array of dietary antigens and a dense community of commensal microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota, which contains over 10¹⁴ microorganisms and a gene repertoire (the microbiome) 10-fold larger than the human genome [34] [35]. The functional integrity of this barrier is not static but is dynamically regulated by complex interactions between host cells, microbial metabolites, and dietary components [34] [36]. Compromised barrier function, often referred to as "leaky gut," is characterized by increased intestinal permeability and has been associated with a spectrum of gastrointestinal and systemic disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), food allergies, obesity, diabetes, and neurological conditions [34] [35] [37]. A foundational understanding of the gut barrier's composition and function is essential for developing interventions aimed at preserving systemic health.

Architectural and Functional Composition of the Intestinal Barrier

The gut barrier is a multi-layered system comprising chemical, physical, and immunological components that function in concert to maintain homeostasis.

Cellular and Junction Protein Complexes

The intestinal epithelium is a rapidly self-renewing tissue, with stem cells giving rise to various specialized lineages: enterocytes (nutrient absorption), goblet cells (mucus secretion), enteroendocrine cells (hormone production), and Paneth cells [34]. Paneth cells, located in the small intestinal crypts, secrete antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) such as α-defensins, which are crucial for shaping the microbiota and defending against pathogens [34] [35].

The paracellular space between epithelial cells is sealed by the junctional protein complex, which includes tight junctions (TJs), adherens junctions, and desmosomes [34]. Tight junctions, primarily composed of proteins like claudin (CLDN) and occludin (OCLN), are dynamic structures that regulate the selective passage of ions, water, and solutes, while preventing the translocation of harmful luminal substances [34] [38]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, can dysregulate the expression of these junctional proteins, initiating a vicious cycle of increased permeability and inflammation [34].

Biochemical and Immunological Defense Layers

- The Mucus Layer: Goblet cells secrete gel-forming mucins, primarily MUC2, which form a bilayered structure in the colon. The outer layer is colonized by microbiota, while the inner layer is largely sterile and prevents direct contact between bacteria and the epithelium [34] [35]. This mucus barrier is not merely a physical shield; it also constrains the immunogenicity of intestinal antigens by imprinting dendritic cells (DCs) in an anti-inflammatory state [35].

- Secretory Immunoglobulin A (sIgA): The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) produces sIgA, which is transcytosed across the epithelium into the lumen. sIgA neutralizes pathogens and toxins and helps maintain host-commensal mutualism by coating bacteria and limiting their epithelial adhesion and invasion [34] [35].

- Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs): Paneth cell-derived AMPs, including defensins and cathelicidins, provide innate immune defense by directly killing or inhibiting the growth of microbes, thereby contributing to the regulation of microbial community composition [35].

Table 1: Core Components of the Intestinal Barrier and Their Functions

| Barrier Component | Key Elements | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Epithelium | Enterocytes, Goblet cells, Paneth cells | Nutrient absorption, mucus secretion, AMP production |

| Junctional Complex | Claudins, Occludin, ZO-1 | Regulation of paracellular permeability |

| Mucus Layer | Mucins (e.g., MUC2) | Physical separation of microbes from epithelium |

| Immunological Agents | sIgA, Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) | Pathogen neutralization, microbial population control |

Gut Microbiota and Immune System Cross-Talk

The gut microbiota is indispensable for the proper development and function of the host immune system. Germ-free (GF) animal models have been instrumental in revealing the profound immunodeficiency associated with the absence of microbial colonization [35].

Microbiota in Immune Development and Education

Early-life colonization is a critical period for immune maturation. The microbiota educates the host immune system by driving the development of gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT), including Peyer's patches [34] [35]. Key immune cells are primed by microbial signals:

- T Helper 17 (Th17) Cells: These pro-inflammatory cells are absent in GF mice and can be induced by specific commensals like segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) [35].

- Regulatory T (Treg) Cells: Certain microbial products, such as Polysaccharide A (PSA) from Bacteroides fragilis, promote the differentiation of Treg cells, which are vital for sustaining immune tolerance and preventing aberrant inflammation [35].

- Immunoglobulin A (IgA): Microbial colonization stimulates the production of IgA, which is significantly reduced in GF animals [35].

Recognition and Signaling Pathways

The innate immune system uses Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs), to detect conserved Microbial-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs).

- TLR Signaling: For instance, TLR5 recognizes bacterial flagellin. Signaling through TLRs is involved not only in host defense but also in maintaining epithelial integrity and regulating the composition of the commensal microbiota [35].

- Anti-inflammatory Pathways: PSA from B. fragilis is recognized by a TLR2/TLR1 heterodimer in cooperation with Dectin-1. This signaling cascade activates the PI3K pathway, inactivating GSK3β and leading to CREB-dependent expression of anti-inflammatory genes [35].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways in microbiota-immune system crosstalk:

Diagram 1: Microbiota-Immune Signaling Pathways. MAMPs from microbiota engage PRRs on host cells, activating pro-inflammatory (NFkB) or anti-inflammatory pathways. Microbial metabolites like SCFAs also directly strengthen the barrier and modulate immune cells.

Quantitative Profiling of Gut Core Microbiota: Methodological Frameworks

Accurate quantification of gut microbiota is vital for understanding its role in health and disease. While metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is a powerful discovery tool, its limitations—including cost, turnaround time, and lack of standardization—hinder wide clinical application [14].

Absolute vs. Relative Quantification

A critical advancement in the field is the shift from relative to absolute quantitative analysis. Relative quantification, which expresses the abundance of a microbe as a proportion of the total sequenced community, can be misleading. For example, a decrease in one species' relative abundance might not reflect an actual decrease in its absolute numbers but rather an increase in another species [39]. Absolute quantification measures the true, concrete number of each microbial target, providing a more accurate picture of the microbial community [39]. A 2025 study on berberine highlighted that conclusions about drug-induced microbial changes drawn from absolute and relative quantification methods can differ significantly, underscoring the importance of absolute quantification for evaluating drug effects [39].

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Assay Panel

To address the need for rapid and precise quantification, a panel of 45 quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assays targeting gut core microbes with high prevalence and/or abundance has been developed [14]. This method offers a streamlined alternative to mNGS for targeted analysis.

- Primer Design: Species-specific genetic markers and primers were selected through comprehensive comparative genomic analysis. For 31 of the 45 core microbes, novel specific primers were designed to ensure high specificity [14].

- Performance Metrics: The established qPCR assays demonstrate high sensitivity, with a limit of detection ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 pg/µL of genomic DNA. The method showed strong consistency with mNGS (Pearson’s r = 0.8688, P < 0.0001) when analyzing the abundance of selected bacteria in human fecal samples [14].

- Application: This qPCR system enables simple, rapid (1-2 hours), and quantitative tracking of dynamic changes in core microbes, providing a valuable tool for understanding their role in health and disease [14].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Gut Microbiota and Barrier Integrity Assessment

| Methodology | Key Feature | Application in Gut Research | Performance/Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Quantitative Metagenomics | Measures total microbial load | Accurately evaluates drug effects on microbiota; overcomes limitations of relative abundance data [39] | Reveals true bacterial count changes; critical for pharmacological studies |

| qPCR Assay Panel | Targets 45 core gut microbes | Rapid, specific quantification of known bacterial targets; tracking dynamic changes in individuals [14] | LOD: 0.1-1.0 pg/µL; High correlation with mNGS (r=0.87) |

| Germ-Free (GF) Animal Models | Complete absence of microorganisms | Studies on microbiota's role in immune system development and barrier function [35] | Reveals immunodeficiency and underdeveloped lymphoid tissues in GF animals |