Bioequivalence of Synthetic vs Natural Bioactive Compounds: Scientific Foundations, Methodologies, and Clinical Implications

This comprehensive review examines the scientific and regulatory framework for establishing bioequivalence between synthetic and natural bioactive compounds, a critical consideration for drug development professionals and researchers.

Bioequivalence of Synthetic vs Natural Bioactive Compounds: Scientific Foundations, Methodologies, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the scientific and regulatory framework for establishing bioequivalence between synthetic and natural bioactive compounds, a critical consideration for drug development professionals and researchers. The article explores fundamental differences in compound origin, structure, and complexity, alongside methodological approaches for bioavailability assessment including pharmacokinetic studies and advanced analytical techniques. It addresses significant challenges in ensuring therapeutic equivalence, including variability in natural sources, metabolic differences, and complex formulation requirements. Through comparative analysis of regulatory standards and clinical evidence, this work provides a rigorous foundation for evaluating interchangeability, offering strategic insights for developing safe, effective, and standardized bioactive therapies across pharmaceutical and nutraceutical domains.

Defining Bioequivalence and Bioactive Compound Diversity

Bioequivalence establishes that two products with the same active ingredient are therapeutically equivalent by demonstrating comparable rate and extent of drug availability at the site of action. For natural bioactive compounds and their synthetic counterparts, demonstrating bioequivalence presents unique scientific challenges. While small molecule synthetic drugs typically have well-defined chemical structures that enable straightforward bioequivalence testing, natural products often exist as complex mixtures whose full composition may not be completely characterized [1]. The fundamental principle governing this evaluation is that the human body responds to chemical structure, not the source of that structure [2]. When natural and synthetic versions are chemically identical ("nature-identical"), they are expected to behave identically in biological systems, though differences in impurities, chirality, or formulation can significantly impact their biological performance.

The assessment of rate and extent of availability involves sophisticated pharmacokinetic measurements and, when necessary, pharmacodynamic endpoint studies. For conventional chemical drugs, generic versions must demonstrate chemical identity and bioequivalence in healthy human subjects [1]. However, for more complex natural product-based therapeutics and biologics, the regulatory requirements are more stringent, often requiring a "totality of evidence" approach that integrates multiple analytical and biological methods to establish comparable safety and efficacy profiles [1].

Structural and Physicochemical Comparison

Comparative analysis of natural products (NPs) and synthetic compounds (SCs) reveals significant differences in their structural characteristics that can influence bioequivalence. A comprehensive time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis of over 186,000 natural products and an equal number of synthetic compounds provides quantitative insights into these distinctions [3].

Molecular Size and Complexity

Table 1: Physicochemical Properties of Natural vs. Synthetic Compounds

| Property | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Analytical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Larger and increasing over time [3] | Controlled range (often 100-1000 Da) [1] | Affects membrane permeability and bioavailability |

| Ring Systems | More rings, larger fused rings, increasing glycosylation [3] | More aromatic rings, stable 5-6 membered rings [3] | Impacts protein binding and metabolic stability |

| Structural Complexity | Higher complexity and structural diversity [3] | Governed by drug-like constraints (e.g., Rule of Five) [3] | Influences dissolution and absorption kinetics |

| Heavy Atoms | Higher counts, increasing over time [3] | Moderate counts with limited variation [3] | Affects distribution and elimination profiles |

Elemental Composition and Functional Groups

Natural products exhibit distinct elemental distributions, with higher oxygen content and specific functional group patterns compared to synthetic compounds, which contain more nitrogen atoms, sulfur atoms, and halogens [3]. These differences influence solubility characteristics, metabolic pathways, and ultimately the rate and extent of bioavailability. The structural evolution of synthetic compounds shows some influence from natural products but has not fully evolved in their direction, maintaining more constrained physicochemical properties governed by synthetic accessibility and drug-like criteria [3].

Regulatory Frameworks and Bioequivalence Standards

Small Molecule Drugs vs. Biologics

The regulatory requirements for demonstrating bioequivalence differ significantly between conventional small molecules and complex natural products or biologics. For small molecule drugs, generic versions must exhibit chemical identity and be bioequivalent in healthy human subjects, typically demonstrated through pharmacokinetic studies measuring rate (C~max~, T~max~) and extent (AUC) of availability [1]. This established pathway depends on the ability to fully characterize the chemical structure and establish pharmaceutical equivalence.

For natural product-based therapies and biological drugs, the regulatory framework is more complex. These products "are produced in living systems or are derived from biologic material" and "tend to be larger in size than chemically-derived drugs, can exhibit a variety of post-translational modifications, and can have activities that are dependent on specific conformations" [1]. The European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration have established specific pathways for biosimilar products (termed "subsequent entry biologics" or "biocomparables") that acknowledge the impossibility of exact replication of complex biological products [1].

The "Totality of Evidence" Approach

For complex natural products and biosimilars, regulators employ a risk-based "totality of evidence" approach that integrates multiple lines of evidence [1]. This includes:

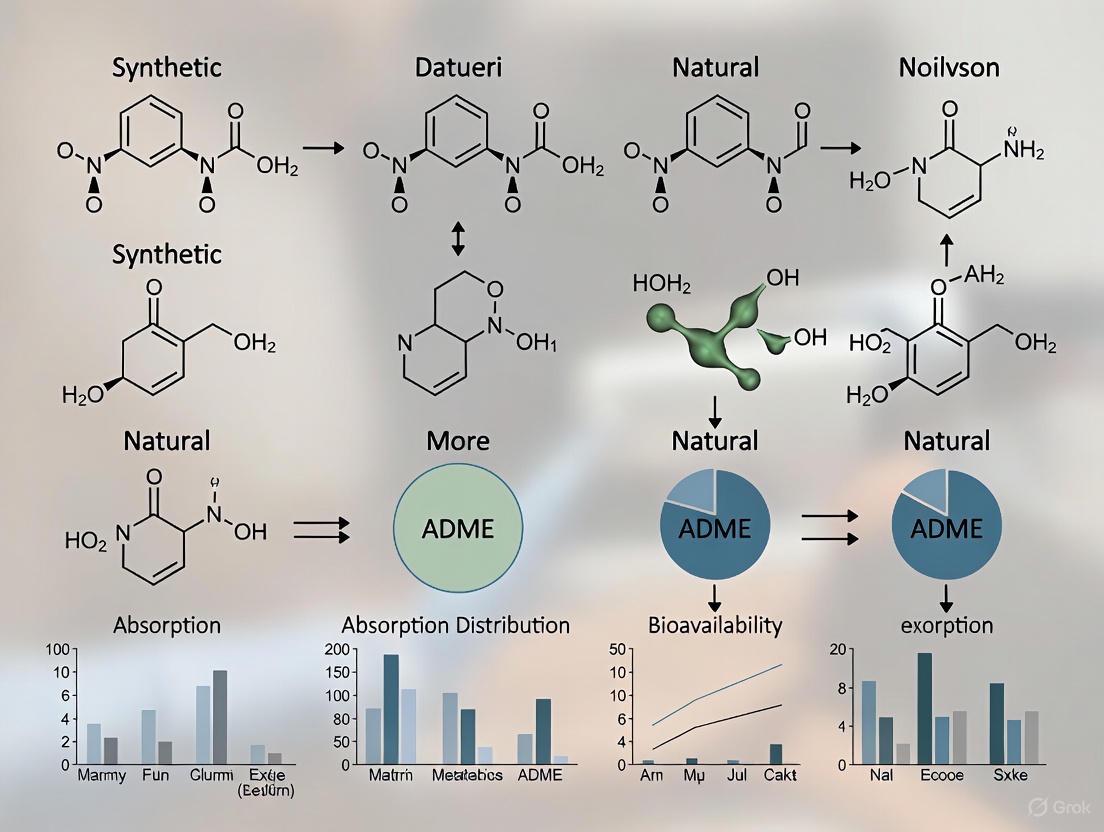

Diagram 1: Totality of Evidence Approach for Complex Products. This integrated strategy is required for natural products and biosimilars where conventional bioequivalence studies are insufficient [1].

Experimental Methodologies for Bioequivalence Assessment

Analytical Techniques for Structural Characterization

Establishing bioequivalence begins with comprehensive structural characterization using advanced analytical techniques:

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) provides high-resolution separation and identification of compounds in complex natural product mixtures. Modern ultra high pressure liquid chromatography systems coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometers enable crude plant extract profiling and metabolite identification [4]. Key parameters include: reversed-phase columns (C18, 1.7-1.8 μm particle size), water-acetonitrile gradients with 0.1% formic acid, and full-scan MS with data-dependent MS/MS fragmentation.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy offers complementary structural information, particularly for stereochemistry and molecular conformation. The HPLC-PDA-HRMS-SPE-NMR platform integrates multiple techniques for definitive structural elucidation directly from crude extracts [4]. Standard experiments include ^1^H, ^13^C, COSY, HSQC, and HMBC NMR collected in appropriate deuterated solvents (methanol-d~4~, DMSO-d~6~).

Pharmacokinetic Study Design

For bioavailability assessment, well-controlled pharmacokinetic studies remain the gold standard:

Study Population: Typically 24-36 healthy adult volunteers under fasting conditions, with crossover design to minimize inter-subject variability. For natural products with known pharmacological effects, patient populations may be more appropriate.

Bioanalytical Method Validation: Fully validated methods per FDA/EMA guidelines assessing selectivity, sensitivity, linearity, accuracy, precision, and stability. For natural products, simultaneous quantification of multiple active constituents and metabolites may be required.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters: Primary endpoints include AUC~0-t~, AUC~0-∞~, and C~max~, with T~max~ as a secondary parameter. Bioequivalence is established if the 90% confidence intervals for the geometric mean ratios of test/reference products fall within 80-125% for AUC and C~max~.

In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models

Table 2: Experimental Models for Bioavailability Assessment

| Model System | Application | Key Parameters | Relevance to Natural Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Monolayers | Intestinal permeability | Apparent permeability (P~app~), efflux ratios | Predicts absorption of multiple constituents |

| Hepatocyte Cultures | Metabolic stability | Intrinsic clearance, metabolite identification | Accounts for complex metabolism |

| Plasma Protein Binding | Distribution characteristics | Free fraction, binding constants | Impacts volume of distribution |

| Biopharmaceutics Classification | Solubility and permeability | Dose number, dissolution rate | Guides formulation development |

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioequivalence Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioequivalence Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation | Low UV cutoff, minimal background ions |

| Stable Isotope Standards | Internal standards for quantification | Deuterated or ^13^C-labeled analogs |

| Transwell Permeability Systems | In vitro absorption models | Caco-2, MDCK, PAMPA models |

| Human Liver Microsomes | Metabolic stability assessment | Cytochrome P450 phenotyping |

| Biorelevant Media | Dissolution testing | FaSSGF, FaSSIF, FeSSIF simulating gastrointestinal conditions |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Hepatic clearance prediction | Metabolic pathway identification |

| Plasma Protein Solutions | Protein binding studies | Human serum albumin, α-1-acid glycoprotein |

Bioequivalence Assessment Workflow

The comprehensive evaluation of bioequivalence between natural and synthetic bioactive compounds follows a structured methodology:

Diagram 2: Bioequivalence Assessment Workflow. This iterative process integrates in vitro and in vivo data to establish therapeutic equivalence [1].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

The demonstration of bioequivalence for natural products faces several significant challenges. Structural complexity increases with newly discovered natural products becoming "larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over time" [3], creating analytical challenges for complete characterization. Multi-constituent preparations may contain multiple active compounds with synergistic or antagonistic effects that are not fully captured by measuring single marker compounds. Batch-to-batch variability in natural product sourcing contrasts with the highly controlled consistency achievable through synthetic production [2].

Emerging approaches to address these challenges include physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling to predict in vivo performance, biopharmaceutics tools for predicting absorption limitations, and pharmacometabolomics for comprehensive assessment of biological effects. The continuing evolution of analytical technologies, particularly in mass spectrometry and NMR, enables increasingly sophisticated characterization of complex natural products and their biological fates [4].

For drug development professionals, understanding these bioequivalence fundamentals is essential for bridging natural product research with contemporary drug development paradigms. The integration of advanced analytical methodologies with robust biological evaluation creates a framework for demonstrating therapeutic equivalence, enabling the rational development of both natural and synthetic bioactive compounds into safe and effective medicines.

The debate surrounding natural versus synthetic bioactive compounds is a foundational topic in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical research. For drug development professionals and scientists, the choice between these origins involves a complex trade-off between structural complexity, production scalability, and bioequivalence. Every ingredient, whether natural or synthetic, is fundamentally a chemical, and the human body responds to chemical structures rather than their sources [5]. This comprehensive guide objectively compares these two pathways by examining their distinct sources, structural characteristics, production methodologies, and experimental approaches for evaluation, providing researchers with critical data for informed decision-making in therapeutic development.

Natural bioactive compounds are directly extracted or derived from biological sources—plants, animals, marine organisms, or microorganisms [5] [6]. These compounds, including alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolics, have evolved through natural selection, resulting in sophisticated chemical architectures [7]. In contrast, synthetically derived chemicals are produced through human-designed chemical processes in laboratory or industrial settings, either mimicking natural compounds ("nature-identical") or creating entirely novel structures not found in nature [5].

Comparative Analysis of Chemical Profiles

Table 1: Source and Structural Characteristics of Natural vs. Synthetic Bioactive Compounds

| Characteristic | Natural Bioactive Compounds | Synthetic Bioactive Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Sources | Plants, marine organisms, microorganisms, animals [6] [8] | Laboratories, industrial settings [5] |

| Structural Diversity | High chemical diversity; evolved through natural selection [7] | Can be nature-identical or novel structures [5] |

| Molecular Complexity | Elevated molecular complexity, higher sp³ carbon fractions, more stereocenters [9] [7] | Often simpler structures; complexity depends on design [9] |

| Structural Signature | Higher proportions of sp³-hybridized carbon atoms, increased oxygenation, lower halogen/nitrogen content [7] | Controlled structural parameters; potentially higher halogen content [5] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | Subject to natural variation (climate, soil, season) [5] | Highly controlled for consistency and purity [5] |

| Typical Impurities | Natural contaminants from complex biological matrices [5] | Process-related impurities, synthetic intermediates [5] |

Natural products distinguish themselves through their "privileged" structural characteristics, which include higher proportions of sp³-hybridized carbon atoms, increased oxygenation, and decreased halogen and nitrogen content compared to synthetic compounds [7]. This chemical richness is coupled with rigid molecular frameworks and lower lipophilicity (cLogP), traits that facilitate favorable interactions with challenging biological targets [7]. These structural advantages are evolutionary honed, as these molecules function as defense chemicals, signaling agents, and ecological mediators in their native contexts [7].

Production Methods and Technological Approaches

The production pipelines for natural and synthetic bioactive compounds diverge significantly, each with distinct technological requirements, advantages, and limitations.

Production Pathways for Natural and Synthetic Bioactives

Natural Compound Production

Natural compound production begins with sourcing biomass, followed by extraction using either conventional techniques (e.g., Soxhlet extraction, maceration) or modern green technologies including Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), and Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [10] [11]. These advanced methods demonstrate improved efficiency in recovering bioactives while aligning with green chemistry principles through reduced solvent usage, lower energy consumption, and shorter processing times [10] [11]. Subsequent purification employs chromatographic techniques (HPLC, GC-MS) to isolate target compounds from complex biological matrices [8].

Synthetic Compound Production

Synthetic production utilizes chemical synthesis from petroleum-derived or plant-based feedstocks, or biocatalytic approaches using engineered enzymes or microorganisms [5] [12]. Chemical synthesis offers high flexibility for structural modification and analog generation, while biocatalysis leverages nature's synthetic machinery for stereoselective transformations under mild conditions [12]. Emerging hybrid approaches combine chemical and enzymatic steps (chemoenzymatic synthesis) to access complex molecules more efficiently than either method alone [12] [9].

Quantitative Production Metrics

Table 2: Production Method Comparison for Natural and Synthetic Compounds

| Production Aspect | Natural Production | Synthetic Production |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Materials | Plant/animal/microbial biomass [5] | Petroleum derivatives, plant-based feedstocks [5] |

| Extraction/Synthesis | UAE, MAE, SFE [10] | Chemical synthesis, fermentation, biocatalysis [5] [12] |

| Step Count (Complex Molecules) | Fewer biosynthetic steps [9] | High step counts (e.g., 7+ steps for sporothriolide) [9] |

| Scalability Challenges | Limited by biomass availability, seasonal variation [5] | Highly scalable but can be carbon-intensive [9] |

| Environmental Impact | Potential ecological damage from overharvesting [7] | High carbon emissions, energy consumption [9] |

| Purity Control | Variable purity, natural contaminants [5] | Highly controlled purity and consistency [5] |

| Stereochemical Control | Enzyme-controlled (high specificity) [12] | Requires chiral catalysts or resolution [12] |

Experimental Assessment and Bioequivalence

Evaluating the bioequivalence of natural and synthetic bioactive compounds requires rigorous experimental protocols assessing structural identity, biological activity, and pharmacological behavior.

Molecular Complexity Analysis

Quantitative complexity metrics enable direct comparison of natural and synthetic molecules and their production pathways. Key descriptors include molecular weight (MW), the fraction of sp³ hybridized carbon atoms (Fsp³), and complexity index (Cm) [9]. These parameters can be visualized in 3D plots to compare the efficiency of different synthetic strategies, with efficient pathways creating complex target molecules in fewer steps with more direct trajectories through this chemical space [9].

Protocol: Molecular Complexity Calculation

- Calculate Fsp³: Determine the ratio of sp³-hybridized carbon atoms to total carbon atoms [9]

- Determine Cm (Complexity Index): Calculate using the formula Cm = A + B - F, where A represents carbon atoms, B represents stereocenters, and F represents flexibility parameters [9]

- Plot in 3D Chemical Space: Create 3D plots parameterized by Fsp³, Cm, and MW to visualize and compare synthetic routes [9]

- Measure Chemical Distance: Calculate linear distance between intermediates using: Distance = √[(MW₂-MW₁)² + (Fsp³₂-Fsp³₁)² + (Cm₂-Cm₁)²] [9]

Bioequivalence Assessment Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Bioequivalence Testing

Protocol 1: Structural Identity Confirmation

- Chromatographic Analysis: Perform co-elution studies using HPLC/HPLC-MS to confirm identical retention times and mass spectra for natural and synthetic versions [8]

- Spectroscopic Characterization: Conduct comprehensive NMR (¹H, ¹³C, 2D) and HRMS analysis to verify structural identity [8]

- Stereochemical Analysis: Use chiral chromatography or circular dichroism to confirm identical stereochemistry for chiral compounds [12]

Protocol 2: Biological Activity Assessment

- In Vitro Target Engagement: Measure IC₅₀/EC₅₀ values against molecular targets using fluorescence-based or radiometric assays [7]

- Cellular Phenotypic Screening: Evaluate effects in relevant cell models (e.g., cytotoxicity, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial activity) [7]

- Mechanism of Action Studies: Employ techniques like thermal shift assays, surface plasmon resonance, or CRISPR-based screening to confirm identical mechanisms [7]

Protocol 3: Pharmacokinetic Evaluation

- Bioavailability Assessment: Compare Cmax, Tmax, and AUC in appropriate animal models following oral and intravenous administration [8]

- Metabolite Profiling: Identify and compare metabolic products using LC-MS/MS in plasma, urine, and feces [8]

- Tissue Distribution Studies: Quantify compound levels in target tissues to confirm equivalent biodistribution [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Natural vs. Synthetic Compound Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Relevance to Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction/Synthesis | UAE/MAE systems, bioreactors, chemical synthesis glassware | Obtaining target compounds from source or feedstocks [10] | Both, with technology variation |

| Separation & Analysis | HPLC/UPLC, GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, NMR spectroscopy | Purity assessment, structural elucidation [8] | Essential for both |

| Bioactivity Screening | HTS platforms, microplate readers, SPR instruments | Target engagement and potency assessment [7] | Critical for bioequivalence |

| Computational Tools | AntiSMASH, GNPS, molecular docking software | Pathway prediction, metabolite annotation [7] | Both origins |

| Cell-Based Assays | iPSCs, reporter cell lines, primary cells | Functional activity in biological systems [7] | Mechanism confirmation |

| Formulation Aids | Liposomes, nanoemulsions, solid lipid nanoparticles | Bioavailability enhancement [8] [13] | Addresses limitations of both |

The choice between natural and synthetic origins for bioactive compounds presents researchers with a multifaceted decision matrix rather than a simple binary selection. Natural products offer unparalleled structural complexity honed by evolution, often with privileged bioactivity profiles, but face challenges in sustainable sourcing and batch-to-batch consistency [9] [7]. Synthetic compounds provide superior production control, scalability, and purity but may lack the sophisticated structural features of natural counterparts and can involve carbon-intensive manufacturing processes [5] [9].

The emerging paradigm leverages the strengths of both approaches through hybrid strategies: using synthetic biology to optimize natural compound production, applying synthetic chemistry to diversify natural scaffolds, and utilizing biosynthetic pathways for complex steps coupled with chemical synthesis for diversification [12] [9]. For researchers, the critical determinant remains the demonstrated bioequivalence—structural, functional, and pharmacological—between natural and synthetic versions, rather than their origin. As technological advances in genomics, synthetic biology, and artificial intelligence continue to transform both fields, the distinction between natural and synthetic continues to blur, pointing toward an integrated future that maximizes the benefits of both approaches for drug discovery and development [7].

For researchers investigating the bioequivalence of synthetic versus natural bioactive compounds, understanding the regulatory framework established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is fundamental. Bioequivalence (BE) studies are critical for demonstrating that a generic drug product performs in the same manner as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD) [14]. The FDA defines two products as bioequivalent when they are equal in the rate and extent to which the active pharmaceutical ingredient becomes available at the site(s) of drug action [15]. For generic drug approval, these studies provide the essential proof that the generic product matches the reference brand in terms of safety, efficacy, and quality, ensuring patients receive safe, effective, and interchangeable medicines [16].

The foundation of therapeutic equivalence rests on two key concepts: pharmaceutical equivalents and therapeutic equivalents. Pharmaceutical equivalents are drug products that contain identical amounts of the identical active drug ingredient in the identical dosage form and route of administration, meet identical compendial standards, but may differ in characteristics such as shape, scoring configuration, release mechanisms, packaging, and excipients [17]. Therapeutically equivalent products must be both pharmaceutical equivalents and bioequivalent, ensuring they can be expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile when administered to patients under conditions specified in the labeling [17].

Quantitative Bioequivalence Standards

Statistical Criteria for Establishing Bioequivalence

The FDA employs rigorous statistical criteria to determine bioequivalence between generic and reference products. For most orally administered immediate-release solid oral dosage forms, the primary pharmacokinetic parameters assessed are the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC), which measures the extent of absorption, and the maximum concentration (Cmax), which measures the rate of absorption [16].

Table 1: Standard FDA Bioequivalence Criteria for Systemic Exposure Measures

| Parameter | Statistical Comparison | Acceptance Range | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC₀–t | Geometric mean ratio (Test/Reference) | 90% CI must fall within 80.00%-125.00% | Randomized, two-period, two-sequence crossover |

| AUC₀–∞ | Geometric mean ratio (Test/Reference) | 90% CI must fall within 80.00%-125.00% | Randomized, two-period, two-sequence crossover |

| Cmax | Geometric mean ratio (Test/Reference) | 90% CI must fall within 80.00%-125.00% | Randomized, two-period, two-sequence crossover |

These criteria apply to dosage forms intended for oral administration and to non-orally administered drug products where reliance on systemic exposure measures is suitable for documenting BE [18]. The 90% confidence intervals for the ratio of test-to-reference product pharmacokinetic parameters must fall entirely within the 80.00%-125.00% range, typically using a logarithmic transformation of the data [16].

Special Criteria for Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

For narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, where small differences in dose or concentration can lead to serious therapeutic failures or adverse effects, the FDA applies stricter bioequivalence criteria. While specific harmonized criteria are still under development through the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M13 process, current approaches may include tighter confidence intervals, scaling approaches based within-subject variability, and point estimate constraints [19].

Recent research proposes alternative FDA BE criteria for NTI drugs that include "capping the minimum BE limits, applying alpha adjustment, and applying a point estimate constraint" [19]. This aligns with the ICH M13's goal of harmonizing BE standards globally and reflects the critical nature of NTI drugs where the balance between therapeutic efficacy and toxicity is particularly delicate.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Study Designs

The FDA provides detailed recommendations for BE study designs to ensure generation of reliable and scientifically valid results. For most bioequivalence studies with pharmacokinetic endpoints, the agency recommends a randomized, two-period, two-sequence crossover design under both fasting and fed conditions where applicable [16].

Table 2: Key Elements of FDA Bioequivalence Study Protocols

| Study Component | Protocol Requirements | Scientific Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Selection | Healthy adult volunteers generally preferred; sufficient number to achieve adequate statistical power | Minimizes variability from disease states; ensures statistical validity |

| Study Conditions | Both fasting and fed conditions for applicable oral dosage forms | Accounts for food effects on drug absorption |

| Blood Sampling | Adequate sampling over time to define pharmacokinetic profile | Ensures accurate characterization of absorption and elimination phases |

| Bioanalytical Methods | Validated methods per Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards | Ensures reliability and reproducibility of concentration measurements |

| Statistical Analysis | Average bioequivalence using two one-sided tests procedure | Standard statistical approach for establishing equivalence |

Studies must be conducted according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards to ensure the reliability and integrity of data [15] [16]. The FDA encourages sponsors to submit in vivo BE study protocols for review before beginning studies, particularly for complex products or novel methodologies [15].

Bioequivalence Establishment Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key decision pathways and methodological considerations for establishing bioequivalence according to FDA standards, particularly highlighting the role of biowaivers and product-specific guidances.

Diagram 1: FDA Bioequivalence Assessment Pathway - This workflow outlines the key regulatory and scientific decision points for establishing bioequivalence, including biowaiver eligibility and study requirements.

Alternative Approaches: Biowaivers

The FDA may waive the requirement for in vivo BE studies (biowaivers) for certain generic products when in vitro approaches provide sufficient assurance of bioequivalence [15]. Categories of products potentially eligible for biowaivers include:

- Parenteral solutions intended for intravenous, subcutaneous, or intramuscular injection

- Oral solutions or other solubilized forms

- Topically applied solutions intended for local therapeutic effects

- Inhalant volatile anesthetic solutions

For a generic product to be considered for a biowaiver, it must generally contain the same active and inactive ingredients (Q1) in the same dosage form and concentration (Q2) and have the same pH and physico-chemical characteristics (Q3) as the approved Reference Listed Drug [15]. The ICH M13B guidance further describes scientific and technical aspects for supporting biowaivers for additional strengths of orally administered immediate-release solid oral dosage forms when in vivo BE has been demonstrated for at least one strength [20].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The Scientist's Toolkit for Bioequivalence Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FDA-Compliant Bioequivalence Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in BE Assessment | Regulatory Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Bioanalytical Assays (LC-MS/MS) | Quantification of drug and metabolites in biological matrices | FDA Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidelines [15] |

| USP Calibration Standards | Reference materials for dissolution testing | USP General Chapter <711> Dissolution [21] |

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Simulate gastrointestinal conditions for in vitro release | Product-specific guidances [14] |

| Certified Reference Standards | Quantify active ingredient in test and reference products | 21 CFR 211.160 (cGLP) |

| Pharmacokinetic Modeling Software | Calculate AUC, Cmax, Tmax, and other parameters | FDA Statistical Guidance for Bioequivalence [18] |

Researchers must employ validated bioanalytical methods to generate reliable data for bioequivalence assessment. The FDA recommends submission of bioanalytical method validation reports for review prior to beginning pivotal BE studies [15]. For dissolution testing, which serves as a critical in vitro tool for predicting in vivo performance, the harmonized USP General Chapter <711> Dissolution provides standardized methodologies, though the FDA recommends mechanical calibration of dissolution apparatus rather than reliance on calibration tablets for GMP purposes [21].

Emerging Regulatory Trends and Complex Products

Product-Specific Guidance and Harmonization

The FDA issues product-specific guidances (PSGs) that provide detailed recommendations for developing generic versions of specific reference listed drugs [14]. These PSGs are developed and revised on a quarterly basis and describe the agency's current thinking on the most appropriate methodology for demonstrating bioequivalence for specific products [22]. For complex generic drug products—including those with complex active ingredients, formulations, routes of delivery, or dosage forms—the PSGs provide critical guidance on navigating uncertainty in the approval pathway [22].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is actively working to harmonize global bioequivalence standards through the M13 series of guidances. The recently drafted M13B guidance focuses on bioequivalence for immediate-release solid oral dosage forms, specifically addressing additional strengths biowaivers [20]. Simultaneously, scientific research continues to propose refined approaches for narrow therapeutic index drugs, aiming to balance statistical rigor with practical considerations for drug development [19].

Revision Categories for Product-Specific Guidances

The FDA categorizes revisions to PSGs based on their potential impact on generic drug development programs [22]:

- Critical revisions: Include additional BE studies necessary to establish BE reflecting a change in safety or effectiveness; impact all ANDAs including approved applications

- Major revisions: Include additional BE studies necessary to establish BE and support FDA approval (subcategorized as in vivo or in vitro major revisions)

- Minor revisions: Clarify study designs, provide less burdensome approaches, or add information on newly approved strengths without generally requiring additional studies

- Editorial revisions: Non-substantive changes such as updating references or correcting grammatical issues

This transparent categorization system helps generic drug developers anticipate potential changes to regulatory expectations and plan their development programs accordingly, particularly for products involving synthetic versus natural bioactive compounds where complexity may necessitate more frequent guidance updates.

The fundamental bioequivalence (BE) assumption is a cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical regulation, positing that if two drug products demonstrate equivalent pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles in the body, they will produce equivalent therapeutic outcomes. This principle enables the approval of generic small molecule drugs and biosimilar biological products without repeating large-scale clinical efficacy trials, thereby improving patient access to affordable medicines. BE studies bridge the gap between measured drug concentration-time profiles in biological fluids and the complex physiological processes that lead to a clinical effect.

This assumption rests on a critical chain of reasoning: equivalent PK parameters (the measure of what the body does to the drug) ensure equivalent pharmacodynamic (PD) effects (what the drug does to the body), which in turn produces equivalent clinical efficacy and safety. This review examines the experimental evidence supporting this critical linkage, with particular attention to the evolving context of natural product-based drug development, where complex mixtures and prodrug mechanisms may challenge traditional BE assessment frameworks.

Core Pharmacokinetic Parameters in Bioequivalence Assessment

Bioequivalence evaluation primarily relies on comparing key PK parameters that characterize the rate and extent of drug absorption into the systemic circulation. These parameters are derived from drug concentration measurements in plasma or blood over time following product administration.

Table 1: Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters in Bioequivalence Assessment

| PK Parameter | Definition | Relationship to Therapeutic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| AUC0-t | Area Under the concentration-time curve from zero to last measurable time point | Measures total drug exposure; correlates with efficacy and safety for most drugs |

| AUC0-∞ | Area Under the curve from zero to infinity | Represents complete total exposure; critical for drugs with long half-lives |

| Cmax | Maximum observed concentration | Indicates absorption rate; important for acute effects or concentration-dependent toxicity |

| Tmax | Time to reach Cmax | Reflects absorption speed; critical for drugs needing rapid onset |

Regulatory standards for BE typically require that the 90% confidence intervals for the geometric mean ratios (test/reference) of AUC and Cmax fall within the range of 80.00%-125.00% [23] [24]. For highly variable drugs with intra-individual variability ≥30%, reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) approaches may be applied [23].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies Linking PK Equivalence to Clinical Outcomes

Small Molecule Drugs: Mycophenolate and Palbociclib Formulations

Recent studies on synthetic small molecule drugs provide robust evidence for the fundamental BE assumption. A 2025 randomized, replicated crossover study of enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS) in healthy Chinese males established BE between generic and branded (Myfortic) formulations under both fasting and fed conditions [23]. The study design meticulously characterized PK parameters while also observing clinical tolerability.

Experimental Protocol:

- Design: Single-dose, open-label, four-period replicated crossover with 7-day washout

- Participants: 60 healthy Chinese male subjects

- Interventions: Single 180 mg oral dose of generic or branded EC-MPS

- PK Assessment: Plasma concentrations of mycophenolic acid quantified using validated LC-MS/MS; primary parameters (Cmax, AUC0-48, AUC0-inf) evaluated via non-compartmental analysis

- BE Determination: Reference-scaled average bioequivalence for highly variable parameters (CV ≥30%); average bioequivalence otherwise

- Clinical Correlation: 20 mild adverse events reported across both formulations; no serious AEs occurred, supporting equivalent safety profiles [23]

Similarly, a 2025 study of palbociclib tablets in healthy Chinese subjects demonstrated BE between generic and reference (Ibrance) formulations even under challenging gastric pH conditions created by rabeprazole pre-treatment [24]. This finding is clinically significant as cancer patients frequently require acid-reducing therapy.

Table 2: Bioequivalence Study Results for Synthetic Drugs

| Drug Product | Study Design | Geometric Mean Ratios (Test/Reference) | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycophenolate Sodium (Fasting) [23] | 4-period crossover (n=60) | Cmax: 99.00-111.00%AUC0-48: 98.00-106.00%AUC0-inf: 98.00-106.00% | Equivalent mild AE profile; no serious AEs |

| Mycophenolate Sodium (Fed) [23] | 4-period crossover (n=60) | Cmax: 119.74% (RSABE)AUC0-inf: 99.87% (RSABE) | Food delayed absorption but maintained BE |

| Palbociclib Tablets [24] | 2-period crossover with rabeprazole (n=64) | Cmax: 84.53-91.72%AUC0-t: 87.81-92.49%AUC0-∞: 87.59-92.03% | No serious AEs; well tolerated |

Biological Products: Biosimilar Monoclonal Antibodies

The fundamental BE assumption extends to complex biological products with the demonstration of PK equivalence for biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. The STELLAR-1 phase 1 study established three-way PK equivalence between Biocon's ustekinumab (Bmab-1200) and both EU-approved and US-licensed reference products in healthy subjects [25].

Experimental Protocol:

- Design: Randomized, double-blind, three-arm, parallel-design study over 20 weeks

- Participants: 258 healthy subjects (18-55 years) stratified by ethnicity, body weight, and gender

- Intervention: Single 45-mg subcutaneous injection

- Endpoints: Primary (AUC0-inf, Cmax); secondary (additional PK parameters, immunogenicity, safety)

- Results: All pairwise comparisons met equivalence criteria (90% CIs within 80-125%)

- Clinical Correlation: Similar safety profiles and immunogenicity across groups support the PK-PD-efficacy linkage for biologics [25]

Methodological Framework: Approaches for Establishing Bioequivalence

Study Designs and Statistical Approaches

Different methodological approaches support BE assessment throughout drug development:

BE Establishment Pathway

Advanced Modeling Approaches

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling integrates physiological parameters with drug-specific data to simulate ADME processes [26]. These models are increasingly used in regulatory submissions to support BE evaluation, particularly for:

- Formulation selection and optimization

- Predicting food effects

- Special population dosing

- Pediatric extrapolation [26]

Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced PBPK represents the cutting edge, using machine learning to predict PK parameters from structural formulas when experimental data are limited [27]. This approach is particularly valuable during early development phases of both synthetic and natural product-derived compounds.

Population PK (PopPK) Models enable model-informed precision dosing (MIPD) by quantifying variability in drug concentrations among individuals [28]. The predictive performance of these models is optimally evaluated using forecasting approaches that simulate real-world clinical use [28].

Natural Bioactive Products: Unique Challenges in Bioequivalence Assessment

Natural products present distinctive challenges for BE assessment due to their complex composition and potential prodrug mechanisms [29] [4]. Unlike synthetic compounds with well-defined active pharmaceutical ingredients, natural products often contain multiple constituents that may contribute to overall therapeutic effects.

The FDA and other regulatory agencies generally require identification of marker compounds or active constituents for BE evaluation of natural product-based drugs. However, the complex mixture nature of many natural products means that equivalent PK profiles for known markers may not fully capture potential differences in other bioactive constituents.

Experimental Considerations for Natural Products:

- Complex Mixtures: Multiple potentially active constituents with synergistic effects

- Prodrug Metabolism: Parent compounds may require metabolic activation

- Phytochemical Variation: Batch-to-batch consistency in complex botanical products

- Enteric Metabolism: Differential effects of gut microbiota on natural vs. synthetic compounds [30] [29]

Despite these challenges, technological advances in analytical methods (e.g., LC-MS/MS, NMR) and modeling approaches are strengthening the BE assessment framework for natural products [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Bioequivalence Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function in BE Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological matrices | Gold standard for PK parameter determination; essential for both synthetic and natural compounds [23] |

| Caco-2 Cell Models | Prediction of human intestinal absorption and permeability | Early development phase; estimates absorption rate constant (ka) and fraction absorbed [31] |

| Human Liver Microsomes/Hepatocytes | Prediction of metabolic clearance via IVIVE | Critical for projecting human clearance from in vitro data [31] |

| PBPK Modeling Software (GastroPlus, Simcyp) | Simulation of ADME processes in virtual populations | Formulation optimization, food effect prediction, special population dosing [26] [27] |

| Rabeprazole Pre-treatment | Induction of high gastric pH conditions | Assessment of BE under acid-reducing medication use; required for pH-dependent drugs like palbociclib [24] |

The fundamental bioequivalence assumption remains a scientifically valid and regulatory robust principle supported by extensive clinical evidence across diverse drug classes. The consistent demonstration that equivalent PK profiles predict equivalent clinical outcomes has enabled an efficient generic and biosimilar approval pathway that benefits global healthcare systems.

Ongoing scientific advances are strengthening this linkage through:

- More sophisticated study designs that evaluate BE under challenging clinical scenarios

- Enhanced analytical methods for complex natural products and biologics

- Advanced modeling approaches that improve prediction of clinical performance from PK data

As drug products grow more complex, particularly with the increasing development of natural product-derived therapeutics, the fundamental BE assumption will continue to evolve while maintaining its critical role in ensuring therapeutic equivalence for patients worldwide.

Natural products represent a cornerstone in drug discovery, with over 30% of prescribed medicines originating from flowering plants and more than 80% of populations in developing countries relying on traditional medicines predominately derived from herbal sources [29] [32]. These compounds, derived from plants, animals, and microbial resources, exhibit tremendous chemical diversity with superfluous potency for managing communicable and non-communicable diseases [29]. This very diversity, however, creates a fundamental challenge for standardization—the process of establishing consistent and reproducible quality parameters for natural product-based therapeutics.

The standardization paradox emerges from the tension between chemical complexity and therapeutic reproducibility. While natural products offer privileged chemical scaffolds with proven biological relevance, their inherent variability poses significant challenges for bioequivalence studies comparing natural and synthetic bioactive compounds [29] [6]. Low-income countries predominantly rely on natural products as primary health support, yet most herbal medicines are prescribed based on practical evidence and recommended in crude and semi-standardized forms, creating impediments for integration into contemporary medicinal practices [29]. This article examines the analytical frameworks and experimental approaches designed to navigate this complexity, enabling meaningful comparisons between natural and synthetic bioactive compounds within bioequivalence research.

Analytical Methodologies for Characterizing Complex Natural Matrices

Advanced Spectroscopic and Chromatographic Platforms

Modern natural product analysis employs sophisticated hyphenated techniques that combine separation and detection capabilities to address chemical complexity. The inherent chemical diversity of natural products has driven significant progress in analytical technologies, with hyphenated analytical platforms emerging as valuable tools for de novo identification, distribution, quantification, and authentication of constituents [33].

Chromatographic separation coupled with high-sensitivity detection forms the foundation of these approaches. Ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) provides enhanced resolution for crude plant extracts, while high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) systems enable quantification of biomarker compounds [32] [4]. When coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, these platforms facilitate unambiguous structural elucidation directly from complex mixtures [4]. The Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) technique further contributes to functional group identification and chemical fingerprinting [32].

Table 1: Core Analytical Techniques for Natural Product Standardization

| Technique | Application | Resolution/Sensitivity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-PDA | Quantification of biomarker compounds | High resolution for separated compounds | Limited without authentic standards |

| LC-HRMS | Structural elucidation, metabolomics | High mass accuracy (<5 ppm) | Database dependencies |

| FTIR | Functional group identification | Rapid fingerprinting | Limited structural specificity |

| SEM with TLD | Microscopic structural analysis | High-resolution imaging | Surface characterization only |

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Phytochemical Characterization

A standardized methodology for natural product analysis begins with proper specimen collection and authentication, including voucher specimen deposition in recognized herbariums [32]. The process continues through multiple validation stages:

Sample Preparation and Macroscopic Evaluation: Plant material undergoes controlled drying and pulverization before storage in amber containers to prevent degradation. Macroscopic and organoleptic evaluation documents shape, texture, odor, taste, and appearance according to established pharmacognostic parameters [32].

Microscopic and Physicochemical Analysis: Microscopic investigations include transverse sectioning with staining techniques (e.g., toluidine blue) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with through-the-lens detectors for high-resolution structural details [32]. Physicochemical analyses determine ash values, moisture content, extractive values, foaming index, and swelling index—critical quality control parameters [32].

Fluorescence Characterization: Powdered plant material is treated with various reagents and examined under different wavelengths (natural daylight, UV at 254nm and 365nm) to generate unique fluorescence profiles that serve as identifying fingerprints [32].

Phytochemical Screening and Quantification: Preliminary qualitative analysis detects major compound classes (alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, fixed oils) across different extraction solvents (ethanol, dichloromethane, n-hexane) [32]. Quantitative estimation employs the Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content and aluminum chloride colorimetry for total flavonoid content, with results expressed relative to standard compounds (gallic acid and quercetin) [32].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive phytochemical characterization of natural products, encompassing authentication, extraction, and analytical profiling.

Comparative Bioequivalence Assessment: Natural vs. Synthetic Bioactives

Methodological Framework for Bioequivalence Studies

Establishing bioequivalence between natural and synthetic bioactive compounds requires rigorous experimental design that accounts for the complex matrix effects in natural extracts. Pharmacological validation must encompass in-vivo and in-vitro studies evaluating cell cytotoxicity, cell-cell interactions, intracellular activity, gene expression, and metabolomic fingerprints [29]. These preclinical assessments provide robust evidence for the safe long-term utilization of natural medicines to treat diseases [29].

The standardization imperative addresses the economics of large-scale industrial production, shelf life, and distribution challenges that were not concerns when traditional practitioners prepared medicines individually according to patient needs [32]. Modern bioequivalence studies must apply rigorous scientific methodologies to ensure quality and lot-to-lot consistency while maintaining the chemical complexity that may contribute to therapeutic efficacy through synergistic effects [32].

Table 2: Key Methodological Considerations for Natural-Synthetic Bioequivalence Studies

| Parameter | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Standardization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Definition | Complex mixtures with multiple actives | Single chemical entity | Biomarker quantification & chemical fingerprinting |

| Variability Source | Biological, environmental, processing | Synthetic process, purification | Strict quality control protocols |

| Synergistic Effects | Often present due to multi-component nature | Typically absent | Controlled extract ratios & enhanced characterization |

| Bioavailability | Influenced by plant matrix | More predictable | Pharmacokinetic studies with standardized formulations |

Analytical Validation and Quantification Protocols

Validation of analytical methods for natural product standardization requires demonstration of specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness. The calibration curve approach quantifies total phenolic content (TPC) using gallic acid equivalents and total flavonoid content (TFC) using quercetin equivalents, establishing linearity across relevant concentration ranges (typically 20-100 μg/mL) [32].

Chromatographic fingerprinting employs thin-layer chromatography (TLC) for preliminary separation and Rf value calculation, while HPLC provides quantitative analysis of specific marker compounds [32]. Method validation must include determination of limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), precision (repeatability and intermediate precision), and accuracy through recovery studies [33].

Advanced metabolomic approaches using LC-HRMS and multivariate statistical analysis can comprehensively capture the chemical complexity of natural products, enabling comparison of batch-to-batch consistency and detection of adulterants [4]. These methods facilitate the identification of chemical signatures responsible for therapeutic activity rather than focusing solely on single marker compounds.

Technological Innovations Addressing Standardization Challenges

Biotechnology and AI-Driven Solutions

Emerging technologies are revolutionizing natural product standardization by addressing historical bottlenecks. Biotechnological approaches including plant cell culture, microbial fermentation, and metabolic engineering enable more sustainable and scalable production of complex natural products [34] [6]. For instance, engineered yeast platforms can biomanufacture plant-inspired therapeutics like monoterpene indole alkaloids (MIAs) with improved pharmacological properties, overcoming the challenge of low extraction yields from natural sources (often below 0.001%) [34].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning accelerate compound identification and activity prediction. AI models trained on datasets linking molecular fingerprints with pharmacological properties can suggest structural modifications to optimize natural scaffolds for improved efficacy and bioavailability [34] [6]. These computational approaches significantly reduce the dependency on large-scale physical screening while enabling targeted exploration of chemical space around validated natural scaffolds [35].

Enhanced Analytical Capabilities

Modern spectroscopic and chromatographic technologies continue to evolve, addressing previous limitations in sensitivity and resolution. Hyphenated platforms such as LC-MS-NMR combine separation power with structural elucidation capabilities, enabling de novo identification of compounds directly from complex mixtures [33] [4]. Improvements in mass spectrometry instrumentation provide higher mass accuracy and resolution, supporting confident molecular formula assignment even for novel compounds [4].

Metabolic engineering represents another frontier in standardization, with researchers successfully engineering yeast cells to produce complex natural products like vinblastine through the insertion of extensive biosynthetic pathways (31 enzymatic reactions requiring approximately 100,000 DNA bases added to the yeast genome) [34]. This approach bypasses the biological variability associated with plant cultivation and enables consistent production of complex molecules that are difficult to synthesize chemically.

Figure 2: Integrated biotechnology and AI approach for standardized production of natural products, enabling consistent quality and enhanced properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful standardization of natural products requires specialized reagents and reference materials carefully selected for their specific applications in phytochemical analysis and bioequivalence assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Natural Product Standardization

| Reagent/Solution | Application | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Total phenolic content quantification | Oxidation-reduction reaction with phenolics | Fresh preparation required; measures total phenolics not specific compounds |

| Aluminum Chloride (10%) | Total flavonoid content determination | Forms acid-stable complexes with C-4 keto group and C-3 or C-5 hydroxyl | Specific for flavones and flavonols; less reactive with other flavonoid subtypes |

| Toluidine Blue Stain | Microscopic section staining | Metachromatic staining for structural visualization | Differentiates cell types and tissues in transverse sections |

| Chloral Hydrate Solution | Powder microscopy | Clearing agent for tissue examination | Enhances visibility of cellular structures; requires careful handling |

| Standard Compounds (Gallic Acid, Quercetin) | Quantitative calibration | Reference standards for quantification | High-purity standards essential for accurate calibration curves |

| Chromatographic Solvents | TLC/HPLC analysis | Mobile phase components | HPLC-grade purity required; solvent systems optimized for target compounds |

The chemical diversity inherent in natural products presents both challenges and opportunities for standardization in the context of bioequivalence research. While complexity creates hurdles for reproducibility and quality control, it also represents a rich source of chemical scaffolds with validated biological relevance. Modern analytical technologies, including hyphenated chromatographic-spectroscopic platforms and AI-assisted compound identification, are progressively overcoming historical limitations in natural product characterization.

The future of natural product standardization lies in integrated approaches that combine advanced analytics with biotechnological production methods. By leveraging metabolic engineering and microbial biomanufacturing, researchers can achieve consistent production of complex natural compounds while reducing dependence on variable biological sources. Simultaneously, enhanced analytical capabilities enable comprehensive chemical profiling that captures the complexity of natural extracts rather than reducing them to single marker compounds.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape offers new frameworks for establishing meaningful bioequivalence between natural and synthetic bioactives. By adopting these technological advances and standardized methodologies, the scientific community can fully leverage the therapeutic potential of natural products while ensuring consistency, safety, and efficacy—ultimately bridging traditional knowledge with contemporary evidence-based medicine.

Natural products (NPs), or secondary metabolites, have served as the most successful source of potential drug leads throughout human history [36]. These compounds, produced by terrestrial plants, marine organisms, fungi, and bacteria, are not essential for the growth and development of the organism but often evolve as defense mechanisms or adaptations to the environment [36]. Historically, natural products have been used since ancient times and in folklore for treating numerous diseases, with the earliest records depicted on clay tablets in cuneiform from Mesopotamia (2600 B.C.) documenting oils from Cupressus sempervirens (Cypress) and Commiphora species (myrrh) which are still used today [36]. The profound influence of natural products continues in modern medicine, with analyses indicating that approximately half of all new drug approvals trace their structural origins to a natural product [37]. Between 1981 and 2019, 68% of approved small-molecule drugs were directly or indirectly derived from natural products [3]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of natural and synthetic compounds, examining their structural properties, biological relevance, and experimental approaches to inform future drug discovery efforts.

Structural and Physicochemical Comparison

Historical Trajectories and Property Evolution

Table 1: Time-Dependent Evolution of Key Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Natural Products Trend | Synthetic Compounds Trend | Comparative Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Consistent increase over time; recently discovered NPs tend to be larger [3] | Variation within limited range; constrained by synthesis technology and drug-like rules [3] | NPs generally larger than SCs; trend becomes more pronounced over time [3] |

| Ring Systems | Increasing numbers of rings, particularly non-aromatic and sugar rings; fewer ring assemblies indicating bigger fused rings [3] | Increase in aromatic rings; prevalence of five- and six-membered rings due to synthetic stability [3] | NPs feature more complex fused ring systems; SCs dominated by aromatic rings [3] |

| Stereocomplexity | Higher stereochemical content; greater number of stereocenters [37] | Lower stereochemical content; fewer stereocenters [37] | Increased complexity in NPs correlates with biological specificity and selectivity [37] |

| Hydrophobicity | Lower hydrophobicity (ALOGPs) despite larger size [37] | Generally higher hydrophobicity [37] | NPs maintain better solubility profiles despite structural complexity [38] |

| Chemical Diversity | Greater structural diversity and uniqueness; expanding chemical space [3] | Broader synthetic pathways but constrained structural diversity [3] | NPs occupy more diverse chemical space than SCs and drugs [37] |

Molecular Architecture and Drug-Like Properties

Natural products exhibit distinct structural features compared to synthetic compounds. NPs display greater three-dimensional complexity, measured by fraction of sp3 carbons (Fsp3) and stereocenter count [37]. They contain more oxygen atoms and fewer nitrogen atoms, while synthetic compounds show the opposite pattern [3] [37]. Notably, natural products frequently violate Lipinski's Rule of Five while remaining bioavailable, forming what has been described as a "parallel universe" of drug-like compounds [38]. This is possible because nature maintains low hydrophobicity and intermolecular H-bond donating potential when creating biologically active compounds with high molecular weight and numerous rotatable bonds [38].

Table 2: Structural and Biological Property Comparison Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Parameter | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction sp3 (Fsp3) | Higher (>0.5) [37] | Lower (<0.5) [37] | Correlated with improved clinical progression [37] |

| Aromatic Rings | Fewer aromatic rings [37] | More aromatic rings [3] [37] | Reduced flatness improves specificity [37] |

| Oxygen Content | Higher number of oxygen atoms [3] [37] | Lower number of oxygen atoms [3] [37] | Influences hydrogen bonding capacity [37] |

| Nitrogen Content | Fewer nitrogen atoms [3] [37] | Higher number of nitrogen atoms [3] [37] | Affects basicity and interaction patterns [37] |

| Biological Relevance | High; evolved to interact with biological targets [3] | Declining over time [3] | NPs access broader target space [37] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Modern Natural Product Library Development

The construction of chemically diverse natural product libraries requires strategic methodologies to maximize metabolite diversity. A bifunctional approach combining genetic barcoding with metabolomics has proven effective for assessing chemical diversity coverage [39].

Experimental Protocol: Library Development and Diversity Assessment

Sample Collection and Preparation: Environmental isolates are obtained through systematic collection programs (e.g., citizen-science-based soil collection). For fungi, samples are plated and strains exhibiting colony morphologies consistent with target taxa are selected [39].

Genetic Barcoding: Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequencing is performed to establish phylogenetic relationships. Sequences with >90% similarity to type strain data in GenBank are retained for further analysis [39].

Metabolome Profiling: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis is conducted to detect chemical features based on retention time and mass-to-charge ratio. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) helps identify chemical clusters [39].

Diversity Assessment: Chemical diversity coverage is quantified using feature accumulation curves, which measure the rate of new chemical feature discovery as more isolates are added to the library. This enables data-driven decisions about optimal library size [39].

Library Optimization: The relationship between phylogenetic clades and chemical clusters guides strategic inclusion of isolates from underrepresented chemical space, maximizing structural diversity while minimizing redundancy [39].

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Dereplication

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Research

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LC-HRMS-MS Systems | High-resolution metabolite profiling | Separation and identification of complex natural product mixtures [4] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Structural elucidation | Determination of stereochemistry and complete molecular structure [4] |

| ITS Barcode Primers | Phylogenetic identification | Fungal identification and clade determination [39] |

| HPLC-UV/MS-SPE-NMR | Integrated isolation and characterization | Hyphenated system for rapid dereplication [4] |

| Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking | Mass spectrometry data sharing and community curation | Structural analog identification and collaborative discovery [4] |

Modern natural product research employs advanced hyphenated techniques to accelerate compound identification:

- LC-HRMS-MS: Enables rapid dereplication through accurate mass measurement and fragmentation pattern analysis [4]

- HPLC-HRMS-SPE-NMR: Combined system that automates separation, purification, and structural elucidation, minimizing sample loss [4]

- Molecular Networking: Visualizes structural relationships between compounds within complex mixtures using mass spectrometry data [4]

Case Studies: Successful Clinical Translation

Historic Foundations to Modern Therapeutics

The trajectory from traditional natural medicines to modern drugs exemplifies the enduring value of natural products:

- Aspirin: Derived from salicin isolated from the bark of the willow tree Salix alba L. [36]

- Morphine: Isolated from Papaver somniferum L. (opium poppy) and first reported in 1803 [36]

- Artemisinin: Discovered by Youyou Tu (2015 Nobel Prize) from traditional Chinese medicine, now frontline antimalarial therapy [40] [41]

- Avermectins: Discovered by William C. Campbell and Satoshi Omura (2015 Nobel Prize), revolutionized treatment of parasitic diseases [41]

Impact on Drug Approval Trends

Analysis of new chemical entities (NCEs) approved between 1981-2010 reveals consistent influence of natural products, with approximately half of all small-molecule drugs tracing structural origins to natural products across all five-year intervals [37]. Natural product-based drugs occupy larger regions of chemical space and address a wider range of biological targets compared to completely synthetic drugs [37].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Natural products continue to shape modern drug discovery, with technological advances including improved analytical tools, genome mining, and engineering strategies addressing previous challenges [4]. The unique structural features of natural products—increased three-dimensionality, stereocomplexity, and diverse ring systems—provide advantages in targeting challenging biological targets [3] [37]. As chemical diversity remains crucial for addressing emerging health challenges, including antimicrobial resistance, natural products offer expanding opportunities for drug discovery [4] [40]. The integration of modern analytical technologies with traditional knowledge presents a promising path for identifying next-generation therapeutics inspired by nature's chemical innovations [4] [39].

Assessment Methods and Production Technologies for Bioactive Compounds

Bioequivalence studies are fundamental to drug development, ensuring that generic drugs or different formulations of a product perform in the body similarly to a reference product. These studies rely on comparing key pharmacokinetic parameters that describe the rate and extent of drug absorption. For two products to be considered bioequivalent, they must exhibit comparable bioavailability, meaning the active ingredient is absorbed and becomes available at the site of action at a similar rate and extent. The core parameters used to establish this equivalence are the Area Under the Curve (AUC), the Maximum Concentration (Cmax), and the Time to Maximum Concentration (Tmax).

Regulatory agencies worldwide, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), require that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the geometric means of these parameters (test/reference) falls within a predefined range, typically 80% to 125% [42]. This statistical evaluation ensures that any difference between the two products is unlikely to have clinical significance. While this is sometimes misinterpreted as the generic containing 80-125% of the active ingredient, it actually pertains to the confidence interval of the pharmacokinetic ratios [42]. This review provides a detailed comparison of how AUC, Cmax, and Tmax are utilized in bioequivalence studies, with a specific focus on the context of natural and synthetic bioactive compounds.

Core Pharmacokinetic Parameters in Bioequivalence Assessment

Definition and Physiological Significance

The assessment of bioequivalence hinges on three primary pharmacokinetic parameters, each providing distinct insight into the drug's journey in the body.

Area Under the Curve (AUC): The AUC represents the total integrated drug exposure over time. It is calculated from the plasma drug concentration-time curve and is the primary measure of the extent of absorption [43]. A UC reflects how much of the drug ultimately reaches the systemic circulation. In bioequivalence studies, the parameters of interest are typically AUC from zero to the last measurable time point (AUC0–t) and AUC extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞) [43] [44].

Maximum Concentration (Cmax): Cmax is the peak plasma concentration observed after drug administration. It is a critical parameter for assessing the rate of absorption [43]. A drug's Cmax can influence both its therapeutic efficacy and its safety profile, particularly for substances with a narrow therapeutic index where high peak levels could cause toxicity.

Time to Maximum Concentration (Tmax): Tmax is the time taken to reach Cmax following drug administration. Like Cmax, it is an indicator of the absorption rate [45]. While Tmax is easier to interpret physiologically, it is generally observed with lower statistical precision than Cmax or AUC and is often considered a secondary parameter in bioequivalence testing [45].

Table 1: Summary of Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters in Bioequivalence Studies

| Parameter | Description | Primary Role in Bioequivalence | Regulatory Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Area under the plasma concentration-time curve | Measures the extent of absorption; indicates total drug exposure | Primary parameter; 90% CI must be within 80-125% |

| Cmax | Maximum observed plasma concentration | Measures the rate of absorption; indicates peak drug exposure | Primary parameter; 90% CI must be within 80-125% |

| Tmax | Time to reach Cmax | Supports absorption rate assessment; indicates speed of drug arrival | Secondary parameter; typically assessed for clinical relevance rather than statistical equivalence |

Regulatory Standards and Statistical Evaluation

For a test product (e.g., a generic drug or a new formulation) to be deemed bioequivalent to a reference product, a randomized, crossover pharmacokinetic study is conducted. The 90% confidence intervals (CI) for the geometric mean ratios (test/reference) of AUC and Cmax must fall entirely within the bioequivalence range of 80% to 125% [42]. This means that the test product can be statistically shown to deliver drug exposure that is no less than 80% and no more than 125% of the reference product. In practice, for the entire 90% CI to meet this requirement, the mean values for the test and reference products must be very close, indicating that the actual variation between products is small [42].

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a bioequivalence study, from design to regulatory conclusion.

Diagram 1: Standard Workflow for a Bioequivalence Study

Experimental Protocols in Bioequivalence Studies

Standardized Clinical Trial Design

The gold standard for assessing bioequivalence is a single-dose, randomized, crossover study in healthy volunteers. This design minimizes inter-subject variability by having each participant serve as their own control. A typical protocol involves:

- Ethics and Consent: The study must be approved by an independent ethics committee and conducted in accordance with international guidelines (e.g., ICH-GCP, Declaration of Helsinki). Written informed consent is obtained from all participants prior to enrollment [44].

- Subject Selection: Healthy volunteers, often within a specific age range (e.g., 18-40 or 18-55) and with a body mass index (BMI) within normal limits, are selected after medical screening [43] [44].

- Dosing and Washout: Participants are randomly assigned to receive either the test or reference formulation first. After administration, serial blood samples are collected over a period that covers the drug's absorption, distribution, and elimination phases (e.g., up to 84 hours for a long half-life drug) [43]. A washout period of at least 5-7 elimination half-lives separates the two treatment periods to ensure no drug carryover [44].

- Standardized Conditions: Studies are typically conducted under fasting conditions, with standardized meals served post-dose. Fluid intake is often controlled to minimize variability in drug absorption [44].

Analytical and Statistical Methods

- Bioanalysis: Plasma samples are analyzed using highly sensitive and specific methods, such as Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) or Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [43] [44]. These methods are validated to ensure accuracy, precision, and selectivity in measuring the drug's plasma concentration.

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Non-compartmental analysis is typically used to calculate the primary parameters: AUC0–t, AUC0–∞, and Cmax. Tmax is directly observed from the concentration-time data [44].

- Statistical Analysis for Bioequivalence: The calculated AUC and Cmax values are log-transformed and analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The 90% confidence intervals for the geometric mean ratios (test/reference) of AUC and Cmax are then derived. Bioequivalence is concluded if these intervals lie entirely within the 80-125% range [42] [44].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioequivalence Bioanalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Test and Reference Formulations | The pharmaceutical products being compared for bioequivalence. |

| LC-MS/MS or UPLC System | High-precision instrumentation for quantifying drug concentrations in biological samples (e.g., plasma) [43] [44]. |

| Validated Analytical Method | A protocol ensuring the bioanalytical assay is specific, accurate, precise, and reproducible over the expected concentration range. |

| Drug-Specific Standards & Internal Standards | Pure chemical standards used to calibrate the analytical instrument and correct for variability in sample preparation and analysis. |

| Healthy Human Volunteers | Study participants who provide the plasma samples for pharmacokinetic analysis after informed consent [43] [44]. |

Comparative Data: Bioequivalence in Practice

Case Studies of Synthetic Drugs

Recent bioequivalence studies provide clear examples of how pharmacokinetic parameters are applied. A study on rifapentine capsules, a synthetic antibiotic, compared test and reference formulations in healthy male volunteers. The results demonstrated bioequivalence, with the 90% confidence intervals for Cmax, AUC0-t, and AUC0-∞ all falling within the 80-125% range. The mean values for these parameters were closely aligned between the two formulations, confirming similar rates and extents of absorption [43].

Similarly, a study on a low-dose anagrelide capsule (0.5 mg), a synthetic drug for thrombocythemia, showed equivalent bioavailability. The mean AUC0–t was 4533.3 pg·h/mL for the test formulation versus 4515.0 pg·h/mL for the reference. The mean Cmax values were 1997.1 pg/mL and 2061.3 pg/mL, respectively. The point estimates for the ratios were 99.28% for AUC0–t and 94.37% for Cmax, well within the required bioequivalence range [44].

Considerations for Natural Bioactive Compounds

The assessment of natural bioactive compounds and nutraceuticals presents unique challenges. While formal bioequivalence studies are less common, research focuses on their bioavailability—how effectively the body absorbs and utilizes the active compounds.