Bridging the Data Gap: A Research Framework for Consistent Nutrient Comparisons in Organic vs Conventional Agriculture

This article addresses the critical lack of consistency in studies comparing the nutrient profiles of organic and conventional foods, a significant hurdle for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Bridging the Data Gap: A Research Framework for Consistent Nutrient Comparisons in Organic vs Conventional Agriculture

Abstract

This article addresses the critical lack of consistency in studies comparing the nutrient profiles of organic and conventional foods, a significant hurdle for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational reasons for conflicting evidence, from heterogeneous study designs to unmeasured confounding variables. The piece then outlines robust methodological frameworks, including standardized nutrient profiling systems and precision nutrition tools, to enhance data quality. It further provides strategies for troubleshooting common experimental biases and validates approaches through comparative analysis of existing models. The goal is to equip the scientific community with a unified framework to generate reliable, comparable data that can inform clinical research and public health policy.

Deconstructing the Controversy: Why Organic vs. Conventional Nutrient Data Remains Inconclusive

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Research Consistency

FAQ 1: What is the current state of evidence regarding nutritional differences between organic and conventional foods? The body of evidence presents a complex picture without a consensus on general superiority. A comprehensive systematic review from 2024, which analyzed 147 scientific articles encompassing 656 comparative analyses, found that:

- 41.9% of comparisons showed no significant difference.

- 29.1% of comparisons found significant differences.

- 29.0% of comparisons had divergent results (where some studies reported significant differences while others did not) [1]. This indicates that claims of nutritional advantages are highly specific to the food type and nutritional parameter being studied, rather than being universally applicable [1].

FAQ 2: What are the primary methodological sources of inconsistency in study results? Inconsistencies often arise from several key methodological variables:

- Study Duration & Soil History: Short-term studies may not capture long-term soil and crop dynamics. The initial health and organic matter content of the soil at the experiment's start can significantly influence results [2].

- Nutrient Management Systems: Comparisons are confounded by the type of organic inputs used (e.g., farmyard manure, compost, biofertilizers) and the specific practices of the conventional system used as a control [2] [3].

- Analytical Focus: Variations exist in the specific nutritional properties (macronutrients, micronutrients, antioxidants, pesticide residues) and food types analyzed, making cross-study comparisons difficult [1] [4].

- Post-Harvest Handling: Differences in the time to analysis, storage conditions, and transportation of samples can affect the measured nutrient content [5].

FAQ 3: How can researchers better account for soil health in their experimental designs? Soil health is a critical confounding variable. Key parameters to monitor throughout the experiment include:

- Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) and Soil Organic Matter (SOM): Fundamental indicators of soil fertility.

- Microbial Population and Diversity: Measures the soil's biological activity.

- Soil Enzymatic Activities: Indicators of functional soil processes like nutrient cycling [2]. Integrating these soil health metrics with crop nutrient data allows for a more nuanced interpretation of why nutritional differences may or may not occur.

FAQ 4: What are the proven health benefits linked to organic food consumption? While nutritional content may be comparable, health benefits are often linked to reduced exposure to synthetic inputs. Evidence suggests that organic food consumption:

- Is associated with fewer cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [6] [5].

- May reduce risks of pregnancy complications and pre-eclampsia, likely due to lower pesticide exposure [5].

- Can lead to a reduction in obesity and body mass index (BMI) [6]. It is crucial to note that these observed benefits may be influenced by broader lifestyle factors common among consistent organic consumers [5].

FAQ 5: What is the typical yield trade-off in organic systems, and how does it affect research interpretations? A meta-analysis on organic farming in Bangladesh revealed a yield reduction of 5-34% compared to conventional methods [3]. This is a critical factor to consider when designing studies and interpreting data, as it relates to the broader debate on the trade-offs between nutritional quality, environmental sustainability, and productivity. Some integrated systems show that initial yield penalties can decrease over time with improved soil health [2].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews to provide a clear, comparative overview of the evidence base.

Table 1: Statistical Overview of Comparative Nutritional Analyses

| Category of Finding | Percentage of Comparisons | Number of Comparisons (Out of 656) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Significant Difference | 41.9% | 275 | No consistent evidence of superiority for either system in these parameters [1]. |

| Significant Differences | 29.1% | 191 | Highlights context-specific advantages, dependent on crop and nutrient [1]. |

| Divergent Results | 29.0% | 190 | Underscores methodological inconsistencies and high variability in the research field [1]. |

Table 2: Documented Health Outcomes Associated with Organic Food Consumption

| Health Outcome | Associated Effect | Notes / Potential Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Risk | Reduction in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) risk [6] [5]. | Linked to reduced exposure to synthetic pesticides like glyphosate [6]. |

| Maternal & Fetal Health | Reduced risks of pregnancy complications and impaired fetal development [5]. | Associated with lower maternal pesticide exposure [5]. |

| Body Weight | Reduction in obesity and body mass index (BMI) [6]. | Correlational; may be influenced by overall healthier lifestyle choices [6]. |

Table 3: Soil Health Improvements Under Organic Management

| Soil Health Parameter | Documented Improvement | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Microbial Activity | Increase of 32-84% [3]. | Meta-analysis of organic farming studies. |

| Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) | Increase of up to 15.2% [2]. | Field experiment with integrated organic amendments. |

| Soil Organic Matter (SOM) | Increase of up to 14.7% [2]. | Field experiment with integrated organic amendments. |

| Available Nutrients (N, P, K, etc.) | Increase of 10.7-36.6% [2]. | Field experiment with integrated organic amendments. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Integrated Field Trial for Soil and Crop Nutrient Analysis

This protocol is designed to systematically compare the long-term effects of organic and conventional systems on both soil health and crop nutritional quality.

Detailed Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Establish a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with a minimum of three replications to account for field variability [2].

- Treatment Structure:

- T1 (Conventional Control): 100% Recommended Dose of Fertilizers (RDF) using synthetic sources [2].

- T2 (Basic Organic): 100% Recommended Dose of Nitrogen (RDN) through Farmyard Manure (FYM) [2].

- T3-T7 (Integrated Organic): Combinations of FYM (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100% RDN), Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR), and foliar sprays like panchagavya [2].

- Soil Sampling & Analysis: Collect soil samples (0-15 cm depth) at baseline and after each cropping cycle. Analyze for:

- Plant Sampling & Analysis: Harvest crops at physiological maturity. Analyze for:

- Data Collection Period: Conduct the experiment over a minimum of three consecutive years to observe trends and mitigate seasonal variations [2].

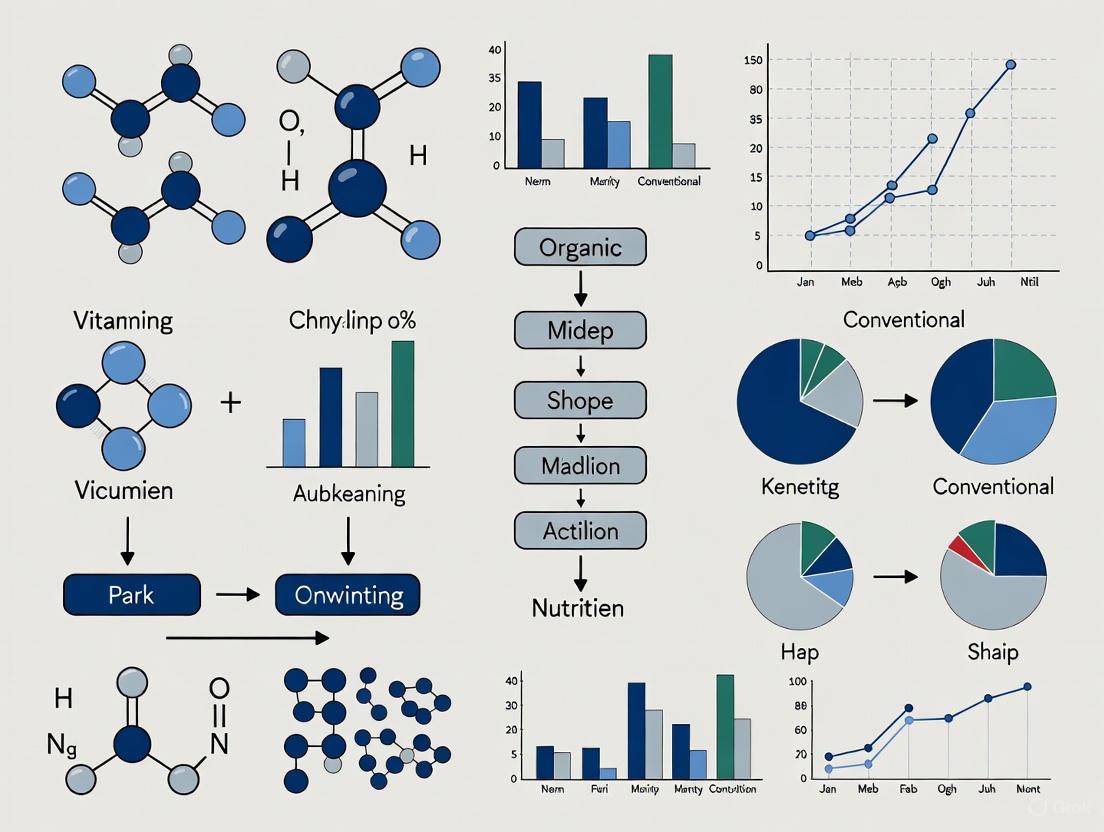

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Systematic Review for Evidence Synthesis

This protocol outlines a rigorous methodology for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses on organic vs. conventional research, aiming to reduce bias and enhance reproducibility.

Detailed Methodology:

- Protocol Registration: Prospectively register the review protocol on an international platform like PROSPERO (CRD42024512893) to enhance transparency and reduce reporting bias [7].

- Search Strategy: Develop a comprehensive search strategy using PRISMA 2020 guidelines [7]. Search multiple electronic databases (e.g., PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science) with predefined inclusion criteria.

- Study Screening & Selection: Systematically screen records (title/abstract, then full-text) against the inclusion criteria. Document the flow of studies and reasons for exclusions [7].

- Data Extraction & Quality Assessment: Use standardized data extraction forms. Assess the quality and risk of bias in individual studies using validated tools (e.g., RoB 2, ROBINS-I, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale) [7].

- Data Synthesis: Perform a random-effects meta-analysis where appropriate, as heterogeneity is expected. Quantify heterogeneity using I² statistics. Assess publication bias using funnel plots and Egger's test [7].

The workflow for this evidence synthesis protocol is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Comparative Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Farmyard Manure (FYM) | A primary source of organic matter and slow-release nutrients. Improves soil structure, water retention, and microbial activity [2]. | Quality can vary; should be well-composted and characterized for nutrient content before application. |

| Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) | Biofertilizers that enhance plant nutrient uptake via biological nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and production of growth-promoting substances [2]. | Strain selection is critical; must be compatible with the crop and soil conditions. |

| Panchagavya | An indigenous liquid formulation used as a foliar spray to enhance plant immunity, soil microbial activity, and nutrient assimilation efficiency [2]. | Typically applied as a 3% foliar spray at critical growth stages [2]. |

| Cover Crop Seeds (e.g., Clover, Rye) | Used to maintain soil cover, prevent erosion, fix nitrogen (legumes), improve soil structure, and enhance nutrient cycling [4]. | Species selection depends on the cropping system and climate. |

| Solvents & Standards for HPLC/GC-MS | Used for the extraction and quantification of specific bioactive compounds (e.g., polyphenols, vitamins) and pesticide residues in plant tissues [6] [4]. | Requires high-purity grades and calibrated standards for accurate quantification. |

| Culture Media for Soil Microbiology | Used to isolate, enumerate, and identify soil microbial populations (bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes) to assess biological soil health [2]. | Different media are required for different microbial groups. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers on controlling critical variables that can compromise the validity of studies comparing organic and conventional agricultural systems, with a focus on nutrient composition research.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How significant are soil properties in skewing crop nutrient data, and what is the most critical factor to control? Soil properties are a primary source of experimental skew. Soil thinning (topsoil loss) is the dominant degradation factor affecting yield and, by extension, nutrient concentration. A meta-analysis of black soil regions established that a topsoil removal depth of 5 cm is the critical threshold, beyond which crop yields are significantly reduced [8]. Yield reduction from soil thinning (-27%) exceeds that from nutrient depletion (-20%) or soil structure degradation (-6%) [8]. This directly impacts nutrient density per unit of yield.

Table 1: Impact of Soil Degradation Types on Crop Yield [8]

| Degradation Type | Average Yield Reduction | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Thinning | 27% | Topsoil removal depth, Soil Organic Matter (SOM), Total Soil Nitrogen (STN) |

| Nutrient Depletion | 20% | Depletion of soil organic matter and essential nutrients |

| Soil Structure Degradation | 6% | Breakdown of soil aggregates, soil compaction |

Experimental Protocol for Controlling Soil Variables:

- Site Selection & Baseline Analysis: Select paired plots (organic & conventional) with similar soil types. Conduct pre-experiment soil analysis to determine baseline levels of Soil Organic Matter (SOM), Total Nitrogen (STN), Available Phosphorus, bulk density, and pH [8] [9].

- Monitor Thickness: Measure and ensure comparable topsoil depth across all study plots, noting that differences greater than 5 cm can be a significant confounder [8].

- Long-Term Monitoring: In long-term studies, track changes in these soil properties annually, as factors like experimental duration and fertilizer types can alter soil chemistry and physics over time, indirectly affecting yield and nutrient content [8].

FAQ 2: To what extent does crop variety, rather than farming system, influence nutritional outcomes? Crop variety can be a more significant determinant of nutrient content than the farming system itself. Controlled environment studies demonstrate that genetic differences between varieties can lead to statistically significant variations in nutraceutical properties, while the difference between a common and a hybrid variety grown under identical conditions can be negligible [10].

Table 2: Effect of Cultivar on Bioactive Compounds in a Controlled Environment [10]

| Plant Crop | Varieties Compared | Key Findings on Nutraceutical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Spinach | Virofly vs. Acadia F1 | No statistically significant differences in antioxidant activity, phenolic content, flavonoids, and photosynthetic pigments were found between the common (Virofly) and hybrid (Acadia F1) varieties. |

| Grapes | Khalili vs. Halwani | The two cultivars showed significantly different responses to the same NPK, Selenium, and Silicon dioxide treatments for traits like cluster length, cluster weight, and total sugar levels. |

Experimental Protocol for Controlling Crop Variety:

- Variety Selection: Use the same genetic cultivar for both organic and conventional arms of the experiment. If this is not feasible, use multiple, well-matched varieties in a balanced design to account for genetic variation.

- Controlled Assessment: When evaluating the effect of a farming practice on a specific nutrient profile, first screen multiple varieties under uniform, controlled conditions (e.g., in a Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting - PFAL) to establish baseline genetic variability [10].

- Documentation: Clearly report the specific cultivars used in all study publications to enable accurate cross-study comparisons and replication.

FAQ 3: What post-harvest handling factors pose the greatest risk to data integrity in nutritional studies? Post-harvest losses (PHL) severely skew results by reducing the edible mass and nutritional value of food before it can be analyzed or consumed [11]. For fruits and vegetables, losses can reach 30-50% along the value chain [11]. The stages of highest loss vary by crop but commonly include threshing/cleaning, transport, and storage [12]. These losses decrease the availability of essential nutrients in the food system, directly impacting measurements of nutritional security [11].

Table 3: Documented Post-Harvest Losses for Key Crops in Niger [12]

| Crop | Reported Loss Rate (Declarative) | Objectively Measured Loss Rate | Stages of Highest Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cowpea | 19.0% | 14.1% | Threshing, cleaning, transport, drying |

| Maize | 16.7% | 19.5% | Threshing, cleaning, transport, drying |

| Sorghum | 17.1% | 14.2% | Threshing, cleaning, transport, drying |

| Millet | 12.5% | 15.7% | Threshing, cleaning, transport, drying |

Experimental Protocol for Standardizing Post-Harvest Handling:

- Define a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP): Establish a strict, documented protocol for harvesting, handling, transporting, and storing samples for all study arms. This includes defining temperature conditions, handling procedures, and time intervals.

- Simulate Value Chain Stages: For a comprehensive assessment, measure key nutritional compounds at multiple points: immediately after harvest, after simulated transport, and after a defined storage period.

- Use Appropriate Technologies: Implement proven loss-reduction technologies consistently. For durable cereals and legumes, hermetic storage bags are widely effective. For perishables, storage structures that maintain temperatures below ambient are critical [13].

Visualizing Research Workflows and Variable Interactions

The following diagrams map the key variables and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Key Variables Affecting Nutrient Research

Diagram 2: Robust Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Methods for Controlled Experiments

| Item / Method | Function / Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hermetic Storage Bags | Creates an oxygen-depleted, modified atmosphere that kills pests and suppresses mold growth, significantly reducing storage losses. | Storing grains and pulses in post-harvest intervention studies to maintain quality and minimize nutrient degradation [13]. |

| Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model (PAHO-NPM) | A profiling tool to objectively classify the "healthiness" of food products based on their nutrient composition, beyond simple nutrient comparisons. | Assessing and reporting the overall nutritional quality of organic and conventional processed foods in a standardized way [14]. |

| Core Sampler | A metal cylinder driven into the soil to extract an undisturbed sample for determining soil bulk density, a key indicator of soil structure and health. | Measuring soil compaction and porosity as part of the baseline soil analysis in experimental plots [8] [9]. |

| Controlled Environment (PFAL) | Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting allows for the precise control of temperature, humidity, light spectrum, and nutrients, eliminating environmental variability. | Studying the intrinsic effect of crop variety on nutraceutical properties without the confounding effects of field conditions [10]. |

| Walkley-Black Method | A wet-chemical oxidation procedure for determining the percentage of organic carbon in soil, a critical metric for soil fertility. | Quantifying Soil Organic Matter (SOM) during the initial site characterization and throughout long-term studies [9]. |

For researchers investigating the compositional differences between organic and conventional foods, the landscape extends far beyond macronutrients. Significant, yet often inconsistent, variations are reported in the concentrations of secondary metabolites like antioxidants, and in the levels of environmental contaminants such as heavy metals and pesticide residues. This technical guide addresses the key methodological challenges in this field and provides standardized protocols to enhance the consistency, reliability, and comparability of future research.

Table 1: Summary of Compositional Differences Between Organic and Conventional Crops from Meta-Analyses

| Compound Category | Specific Compound | Median Difference (Organic vs. Conventional) | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants & Polyphenolics | Total Polyphenolics | + 18% to +69% | [15] [16] |

| Flavanones | +69% | [15] | |

| Anthocyanins | +51% | [15] | |

| Stilbenes | +28% | [15] | |

| Flavonols | +50% | [15] | |

| Toxic Heavy Metals | Cadmium (Cd) | -48% | [15] [16] |

| Pesticide Residues | Incidence on Crops | 4x lower frequency | [16] |

Table 2: Summary of Associated Health Outcomes from Observational Studies

| Health Outcome | Association with Higher Organic Food Intake | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | Reduced incidence | [17] [5] |

| Pregnancy & Fetal Development | Fewer complications and improved development (linked to reduced pesticide exposure) | [5] |

| Allergic Sensitization | Reduced incidence | [17] |

| Infertility | Reduced incidence | [17] |

| Metabolic Syndrome | Reduced incidence | [17] |

Troubleshooting Common Research Inconsistencies

FAQ 1: Why do studies on antioxidant levels in organic vs. conventional crops show such high variability?

Answer: Variability often stems from agronomic and environmental factors that are not adequately controlled.

- Root Cause: Differences are linked to specific agronomic practices. The absence of chemical pesticides forces plants to increase production of defensive secondary metabolites, including polyphenolics [15]. Furthermore, the shift from soluble mineral fertilizers (conventional) to slow-release organic fertilizers (organic) alters soil nutrient dynamics and stress responses, significantly affecting gene and protein expression patterns related to secondary metabolism [15].

- Solution: Implement strict control and reporting of the following variables:

- Fertilizer Type & Regimen: Document the type (e.g., manure, compost), nitrogen content, and application schedule.

- Crop Variety: Use identical genotypes in comparative trials.

- Soil Health Metrics: Measure and report soil organic matter, microbial biomass, and biodiversity.

- Post-Harvest Handling: Standardize time to analysis, storage conditions, and processing methods.

FAQ 2: How can we reliably assess the health implications of lower-level, chronic pesticide exposure via diet?

Answer: The limitation of current regulatory standards, which are based on Maximum Residue Levels (MRLs) for single pesticides, is a key factor.

- Root Cause: Pesticide approval processes typically do not require safety testing for complex mixtures or formulations [17]. Conventional crops often contain multiple pesticide residues simultaneously, creating a "cocktail effect" that is not captured by individual MRL assessments [17].

- Solution: In clinical and cohort studies, move beyond simply measuring the presence or absence of residues. Employ:

- Biomarker Monitoring: Use urine or blood samples to quantify specific pesticide metabolites (e.g., pyrethroid or organophosphate breakdown products) as a direct measure of internal exposure and bioavailability [18].

- Mixture Toxicology Models: Develop and apply experimental models that test the synergistic or additive effects of common pesticide combinations found in the food supply.

FAQ 3: Why do some large-scale reviews conclude there are no significant nutritional benefits to organic food?

Answer: This often results from differing study methodologies and inclusion criteria, particularly the conflation of nutrient composition studies with direct health outcome studies.

- Root Cause: Early systematic reviews were limited by a small number of available studies, especially long-term human dietary interventions [17] [16]. Conclusions based solely on macronutrient (protein, fat, carbohydrate) content often obscure differences in micronutrients and contaminants [1].

- Solution: Design studies with a holistic compositional approach. Focus on:

- Whole-Diet Substitution: Use long-term interventions where the entire diet is replaced with certified organic counterparts to detect measurable health impacts [17].

- Beyond Macronutrients: Prioritize the analysis of bioactive compounds (antioxidants) and contaminants (Cd, pesticides) linked to chronic disease pathways [15] [18].

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Polyphenolics in Plant Tissues

1. Sample Preparation:

- Homogenization: Flash-freeze plant material in liquid N₂ and homogenize to a fine powder using a ceramic mortar and pestle or a laboratory-grade mixer mill.

- Extraction: Weigh 1.0 g of homogenate. Add 10 mL of acidified methanol (e.g., 1% HCl/methanol) or another suitable solvent (e.g., 70% aqueous acetone) for comprehensive polyphenol extraction. Sonicate for 20 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuge at 10,000 x g for 15 minutes.

- Filtration: Collect the supernatant and filter through a 0.45 μm PTFE or nylon syringe filter prior to chromatographic analysis.

2. HPLC-DAD/MS Analysis:

- Instrumentation: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography system coupled with a Diode Array Detector (DAD) and Mass Spectrometer (MS).

- Column: Reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm).

- Mobile Phase: (A) Water with 0.1% Formic Acid; (B) Acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic Acid.

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 40-60 minutes, followed by a column wash and re-equilibration.

- Detection: Use DAD for quantification at characteristic wavelengths (e.g., 280 nm for flavan-3-ols, 360 nm for flavonols). Use MS for definitive compound identification based on mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and fragmentation patterns.

3. Data Quantification:

- Quantify individual compounds using external calibration curves of authentic standards. Express results as μg per g of fresh or dry weight.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Pesticide Exposure in Human Subjects

1. Study Design:

- Intervention: A 24-week randomized, controlled crossover trial is recommended [18]. Participants replace their conventional diet with a certified organic diet for a set period, followed by a washout period and a return to their conventional diet.

- Control: Maintain a consistent cohort on a conventional diet for comparison.

2. Biospecimen Collection:

- Urine Sampling: Collect first-morning void urine samples from participants at baseline, weekly during the intervention, and post-washout.

- Storage: Aliquot samples and store immediately at -80°C to prevent analyte degradation.

3. LC-MS/MS Analysis for Pesticide Metabolites:

- Analytes: Target specific metabolites of common pesticides (e.g., 3-phenoxybenzoic acid for pyrethroids; dialkyl phosphates for organophosphates).

- Sample Prep: Thaw samples on ice. Dilute 1:1 with a buffer. Use solid-phase extraction (SPE) or dilute-and-shoot protocols for clean-up and pre-concentration.

- Instrumentation: Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Quantification: Use isotope-labeled internal standards for each target metabolite to ensure analytical precision and accuracy. Report results as μg of metabolite per g of creatinine.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Comparative Food Composition Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Organic & Conventional Reference Materials | Essential for method validation and calibration. Provides a known baseline for compositional analysis. | Must be sourced from the same crop variety, harvest year, and geographical region to control for confounding variables. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., ¹³C-labeled pesticide metabolites) | Used in LC-MS/MS for highly accurate quantification. Corrects for matrix effects and analyte loss during sample preparation. | Critical for achieving publication-grade data in complex biological matrices like urine or plant extracts. |

| Reverse-Phase C18 HPLC Columns | The workhorse for separating complex mixtures of antioxidants, polyphenols, and pesticide residues. | Standard dimensions: 250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size. UHPLC columns (sub-2 μm) offer higher resolution and faster analysis. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes from complex sample matrices (e.g., urine, food extracts). | Various sorbents available (C18, HLB). Select based on the chemical properties of the target analytes to maximize recovery and reduce interference. |

| Authentic Phytochemical Standards (e.g., Quercetin, Cyanidin, Resveratrol) | Used to create calibration curves for the identification and absolute quantification of specific antioxidants. | Purity should be ≥95% (HPLC grade). Store according to manufacturer specifications to maintain stability. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical confounding factors when comparing organic and conventional diets in human studies?

The most significant confounding factors stem from the difficulty in accurately assessing dietary intake and the inherent differences between people who choose organic versus conventional foods [19] [17].

- Dietary Assessment Limitations: All methods for measuring what people eat (e.g., 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires) have weaknesses. These include poor memory, underreporting of disliked foods like alcohol, and an inability to correctly estimate portion sizes. Furthermore, a single 24-hour recall does not capture an individual's habitual diet, which is what matters for chronic disease risk [19].

- Systematic Consumer Differences: Studies show that regular organic food consumers are often more health-conscious, have higher educational attainment and income, are more physically active, and are more likely to follow plant-based or whole-food diets. These lifestyle and socioeconomic factors are independently linked to better health outcomes and can easily confound observed health differences [17] [20].

- The "Healthy Consumer" Bias: An individual's current diet may not reflect their past diet, and recall of past diet can be influenced by their present habits and beliefs. This makes case-control studies investigating diet and disease particularly susceptible to bias [19].

FAQ 2: How can I control for the "healthy consumer" effect in my observational study design?

Controlling for this effect requires meticulous study design and statistical analysis.

- Measure and Adjust: Collect extensive data on potential confounders, including:

- Use Propensity Score Matching: This statistical technique can help create a comparison group of conventional consumers who are similar to the organic consumers across all measured confounding variables.

- Longitudinal Cohort Designs: Prospective studies that enroll participants before disease develops and follow them over time are more robust than case-control studies for this type of research [21].

FAQ 3: My intervention trial requires participants to switch to an organic diet. What practical challenges should I anticipate?

Dietary intervention trials face specific hurdles related to compliance and study design.

- Cost and Accessibility: Organic foods are often more expensive and less available, which can be a barrier for participants and increase the cost of the study [20].

- Blinding Difficulty: It is challenging to blind participants to their dietary assignment, which may lead to placebo or nocebo effects.

- Defining the Intervention: The "organic" intervention must be clearly defined, typically requiring the use of certified organic foods, and the control diet must be matched in every way except for the production method [17].

- Appropriate Duration: Short-term studies may only capture immediate changes (e.g., reduction in pesticide urine biomarkers) but miss long-term health outcomes. Determining the required length to see a physiological effect is a key design challenge [17] [22].

FAQ 4: How does day-to-day variation in an individual's diet impact my results, and how can I account for it?

Day-to-day variation is a major source of error that can obscure true dietary patterns [19].

- The Problem: An individual's intake of foods and nutrients varies widely from day to day. A single 24-hour recall may miss commonly eaten foods simply because they were not consumed on that specific day.

- The Solution: Increase the number of dietary assessment days. The number needed for a moderately accurate estimate of habitual intake varies by nutrient but can sometimes exceed 30 days. Using food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) designed to capture habitual intake over a longer period (months or a year) is another common, though less precise, approach [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: An observed health benefit from organic food consumption disappears after adjusting for socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors.

- Diagnosis: This strongly suggests that the observed association was not causal but was instead confounded by the "healthy consumer" effect. The health benefit was likely driven by the overall healthier profile of people who choose organic food, not the organic food itself [17] [20].

- Solution:

- Re-evaluate Your Model: Ensure you have collected and adjusted for all relevant confounding variables. Consider using more sophisticated statistical methods like propensity score analysis.

- Design for the Future: For future studies, consider a long-term, whole-diet substitution trial where participants are randomly assigned to receive either organic or conventional diets, thereby minimizing the self-selection bias [17].

Problem: Urine biomarker data shows high variability between participants on the same diet regime.

- Diagnosis: This is expected due to interindividual variation in metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and baseline microbiome composition. Personalization is a key feature of diet-microbiome interactions; the same food can be metabolized differently by different people [22].

- Solution:

- Longitudinal Sampling: Take multiple samples from the same individual over time to define their personalized response, rather than relying on a single time point [22].

- Increase Sample Size: Ensure your study has enough participants to capture and account for the range of human variability.

- Control Diet Pre-sampling: In intervention studies, provide participants with a standardized diet for a few days before sample collection to reduce noise from recent dietary intake [22].

Problem: A study finds no compositional differences between organic and conventional foods, but other literature claims there are.

- Diagnosis: Inconsistencies can arise from methodological differences in food sampling, chemical analysis, and statistical modeling. Factors like crop variety, soil type, weather, and harvest timing can also cause natural variation that obscures production method effects [19] [20].

- Solution:

- Review the Protocol: Critically examine the methodologies of the conflicting studies. Were the foods grown in controlled conditions or purchased from the market? Were they analyzed in the same lab using the same methods?

- Check for Systematic Reviews: Rely on large-scale systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which pool data from multiple studies to provide a more definitive conclusion than any single study can [17] [20].

- Focus on Consistent Trends: Look for patterns across the literature. For example, some meta-analyses consistently report higher antioxidant concentrations and lower cadmium levels in organic crops, even if individual studies disagree [17].

Methodological Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Confounding Factors and Mitigation Strategies in Organic vs. Conventional Diet Studies

| Confounding Factor | Impact on Research | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Status | Organic consumers often have higher income/education, which correlates with better health. | Measure and statistically adjust for income, education, and occupation [17] [20]. |

| Overall Diet Quality | Organic consumers may eat more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and less processed food. | Assess and control for overall dietary patterns (e.g., Mediterranean diet score) and food group intake [17] [20]. |

| Lifestyle Factors | Organic consumers are often more physically active and less likely to smoke. | Collect data on physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol use for use as covariates [17]. |

| Health Consciousness | Greater attention to personal health leads to behaviors that improve outcomes, independent of diet. | Use validated questionnaires to measure health consciousness and include in analysis [20]. |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | BMI is a strong independent risk factor for many diseases and can be a confounder. | Measure and adjust for BMI at baseline and, in long-term studies, over time [17]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Dietary Intake Assessment Methods [19]

| Method | Description | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Recall | Interviewer asks participant to recall all food/beverages consumed in the previous 24 hours. | Low participant burden; does not alter eating behavior. | Relies on memory; single day not representative of usual intake; prone to under-reporting. |

| Food Record/Diary | Participant records all foods/beverages as they are consumed, often with weighed amounts. | More detailed and accurate than recall; multiple days possible. | High participant burden; can alter habitual diet ("reactivity"); requires high motivation. |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Participant reports how often they consumed a fixed list of foods over a long period (e.g., past year). | Captures habitual intake; efficient for large studies. | Portion size estimates are imprecise; memory decay over long periods; fixed food list may not capture all items. |

| Food Supply Data | Estimates national consumption based on food production + imports - exports. | Useful for international comparisons and tracking trends. | Does not account for waste or individual intake; only provides population-level averages. |

Experimental Protocol: Designing a Controlled Feeding Trial to Isolate Production Method Effects

Objective: To determine the effect of a diet made from certified organic ingredients versus a conventional diet on specific health biomarkers, while controlling for diet composition and confounding factors.

Key Materials & Reagents:

- Certified Organic Foodstuffs: All intervention foods must be sourced from certified organic producers.

- Conventional Control Foodstuffs: Sourced to be of the same variety and type as the organic foods.

- Food Composition Database: For nutritional analysis and meal matching (e.g., USDA FoodData Central).

- Biomarker Assay Kits: Validated kits for measuring outcomes of interest (e.g., pesticide metabolites, nutritional biomarkers, oxidative stress markers).

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment & Screening: Recruit healthy participants and screen for willingness to consume all provided study foods. Exclude those with allergies or dietary restrictions that would interfere with the diet.

- Randomization & Blinding: Randomly assign participants to the Organic Diet group or the Conventional Diet group. Implement single-blinding where possible (e.g., participants are not told which diet they are receiving, though complete blinding is difficult).

- Diet Design & Preparation:

- Develop a standardized 7-day rotating menu.

- Prepare identical meals for both groups, differing only in the production method (organic vs. conventional) of the ingredients.

- Control for all other variables: use the same recipes, cooking methods, and portion sizes.

- Food Provision: Provide all meals and snacks to participants for the duration of the intervention period (e.g., 2 weeks to 3 months).

- Compliance Monitoring: Use multiple methods to monitor compliance, such as daily check-ins, returned food containers, and periodic 24-hour recalls.

- Biological Sampling: Collect biological samples (e.g., blood, urine, feces) at baseline, at regular intervals during the intervention, and at the end of the study.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze samples for target biomarkers using standardized, validated laboratory protocols [23].

Visual Workflows and Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Diet-Microbiome and Nutritional Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Organic Reference Materials | Serves as the verified organic intervention material in controlled feeding studies. | Used as the primary ingredient in meals for the organic arm of a clinical trial [17]. |

| Pesticide Metabolite ELISA Kits | Quantifies specific pesticide breakdown products in urine or blood serum. | Measuring changes in pesticide exposure biomarkers in participants before and after an organic diet intervention [17]. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Isolates high-quality genetic material from microbial samples (e.g., stool). | Profiling the gut microbiome composition of study participants to investigate diet-microbiome interactions [22]. |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Assay Kits | Measures concentrations of microbially produced fatty acids (e.g., acetate, propionate, butyrate) in fecal or blood samples. | Assessing functional changes in the gut microbiome in response to different dietary regimes [22]. |

| Food Composition Database | Provides standardized nutrient profile data for thousands of food items. | Calculating the nutritional content of study diets and ensuring the organic and conventional arms are matched for macronutrients and key micronutrients [24] [25]. |

| Nutrient Profiling Model | A algorithm to score the overall nutritional quality of foods or diets. | Controlling for overall diet quality as a confounding variable in observational studies comparing organic and conventional consumers [25]. |

Implementing Rigorous Frameworks: Standardized Methods for Reliable Food Composition Analysis

Leveraging Validated Nutrient Profiling Models (NPS) for Objective Food Quality Assessment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a Nutrient Profiling Model (NPM), and why is its validation critical for research?

A1: A Nutrient Profiling Model (NPM) is a science-based tool that classifies or ranks foods based on their nutritional composition to assess their healthfulness [26] [27]. Validation is the process of testing how well the model's ratings correlate with real-world health outcomes. Using a validated model is crucial for research integrity, as it ensures that the conclusions drawn about a food's quality are supported by scientific evidence and not just the arbitrary output of an algorithm [26] [28]. For instance, a model with strong criterion validity has been shown in studies that higher-rated foods are linked to a lower risk of chronic diseases [28].

Q2: Which NPMs have the strongest scientific validation for predicting health outcomes?

A2: Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis, several NPMs have been assessed for their criterion validity. The following table summarizes the current validation evidence for key models [28]:

| Nutrient Profiling System (NPS) | Level of Criterion Validation Evidence | Key Health Outcomes Linked to Higher Diet Quality (Where Available) |

|---|---|---|

| Nutri-Score | Substantial | Lower risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. |

| Food Standards Agency (FSA-NPS) | Intermediate | Evidence exists but is less extensive than for Nutri-Score. |

| Health Star Rating (HSR) | Intermediate | Evidence exists but is less extensive than for Nutri-Score. |

| Food Compass | Intermediate | Evidence exists but is less extensive than for Nutri-Score. |

| Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF) Index | Intermediate | Evidence exists but is less extensive than for Nutri-Score. |

Q3: My research compares organic and conventional foods. Are some NPMs better suited for this purpose?

A3: The choice of NPM is critical in organic vs. conventional studies. Systematic reviews have found that significant nutritional differences between organic and conventional foods are not universal but are highly dependent on the specific food type and nutrient being analyzed [29] [30]. Therefore, you should select a model with high content validity that incorporates a wide range of relevant nutrients. A model that only considers a few "negative" nutrients (e.g., sugar, sodium, saturated fat) may miss subtle differences in beneficial nutrients (e.g., certain minerals, polyphenols) that could be influenced by production methods [31]. The model should be transparent and its algorithm publicly available to ensure the reproducibility of your findings [31].

Q4: What are common sources of error when applying an NPM in an experimental setting?

A4: Common experimental issues include:

- Inaccurate Input Data: The quality of the NPM output is entirely dependent on the accuracy of the nutrient composition data entered. Reliable data must come from rigorous chemical analysis using validated methods, not just estimated from packaging [32].

- Improper Sample Preparation: Inconsistent sample preparation techniques can alter the nutrient composition of the food being tested, leading to erroneous profiling results [32].

- Misapplication of the Model: Using a model outside its intended scope (e.g., applying a general model to a specific food category for which it wasn't designed) can produce invalid classifications [26] [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Unreliable Nutrient Composition Data

Problem: Results from the NPM are inconsistent with nutritional expectations, potentially due to poor-quality input data.

Solution: Implement a rigorous protocol for generating and handling nutrient composition data.

Experimental Protocol for Food Composition Analysis:

- Representative Sampling: Ensure the food sample is a true representative of the bulk material being studied. Use appropriate quartering or riffling techniques for solid foods [32].

- Standardized Sample Preparation:

- Validated Analytical Methods:

- Total Protein: Prefer the Enhanced Dumas method over traditional Kjeldahl, as it is faster, does not require toxic chemicals, and can be automated [32].

- Total Fat: For complex matrices, Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) offers a faster, more efficient, and less solvent-consuming alternative to traditional Soxhlet extraction [32].

- Dietary Fibre: Utilize integrated assay kits (e.g., Rapid Integrated Total Dietary Fibre (RITDF)) that combine multiple official methods for greater accuracy and potential cost savings [32].

- Data Quality Control: All analytical methods should follow Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and, where possible, use methods endorsed by international organizations like AOAC International to ensure reliability and reproducibility [32].

Issue 2: The Chosen NPM Fails to Detect Relevant Nutritional Differences

Problem: In an organic vs. conventional comparison study, the selected NPM shows no difference, but you hypothesize there may be differences in micronutrients or phytochemicals.

Solution: Employ advanced, non-targeted analytical techniques to build a comprehensive nutrient profile and consider using or developing an NPM that incorporates a wider range of beneficial components.

Experimental Protocol for Non-Targeted NMR Metabolomics:

This technique provides a holistic "fingerprint" of a food's metabolome, capturing subtle variations that targeted methods might miss [33].

- Sample Preparation: Extract metabolites using a standardized solvent (e.g., buffer solution in D₂O). The process must be identical for all samples to ensure comparability [33].

- NMR Measurement: Use optimized and agreed-upon acquisition parameters. The 1D NOESY-presat pulse sequence is often used for aqueous extracts to suppress the water signal. The Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence can be used to highlight low-molecular-weight metabolites [33].

- Data Processing: Process the Free Induction Decay (FID) signals by applying Fourier Transform (FT), phase correction, and baseline correction. Normalize the spectra to a internal standard, such as DSS [33].

- Data Analysis: Use multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA) on the processed spectral data to identify metabolite patterns that differentiate sample groups (e.g., organic vs. conventional) [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and instruments essential for generating high-quality data for nutrient profiling.

| Item | Function / Relevance in Nutrient Profiling Research |

|---|---|

| Halogen Moisture Analyzer | Determines moisture content rapidly and accurately, which is critical for expressing all other nutrient data on a consistent dry-weight basis [32]. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) System | Extracts components like fat efficiently from complex food matrices with reduced solvent use and time compared to traditional methods [32]. |

| NMR Spectrometer | The core instrument for non-targeted metabolomics. It provides a highly reproducible and comprehensive fingerprint of a food's molecular composition, ideal for detecting subtle differences and ensuring authenticity [33]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., DSS for NMR) | A compound of known concentration added to samples to provide a reference point for quantitative analysis and spectral normalization, ensuring data comparability across different runs and instruments [33]. |

| Integrated Dietary Fibre Assay Kit | Provides a streamlined and accurate method for quantifying total dietary fibre by combining several official methods into a single test [32]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Samples with known nutrient concentrations used to calibrate instruments and validate analytical methods, ensuring the accuracy and traceability of all generated data [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a criterion-validated system like the FSA-NPS and a simple, unvalidated checklist for classifying food quality? A criterion-validated system undergoes rigorous scientific testing to ensure it measures what it intends to measure. The FSA-NPS, which underpins the Nutri-Score, has been evaluated for three key types of validity, as recommended by the WHO [34]:

- Content Validity: Its ability to correctly rank foods according to their healthfulness across the entire food supply [34] [35].

- Convergent Validity: Its alignment with national food-based dietary guidelines. Studies have assessed its consistency with French dietary guidelines, though further adaptations may be needed for other European countries [34].

- Predictive Validity: Its ability, when applied to population dietary data, to predict disease risk. Prospective cohort studies have shown that diets composed of foods with worse FSA-NPS scores are associated with higher risks of overall cancer, as well as specific cancers like colon-rectum and lung cancer [36].

An unvalidated checklist lacks this evidence base, leading to potential misclassification and unreliable results in comparative studies.

FAQ 2: Our research involves comparing the nutritional quality of organic versus conventional foods. How can the FSA-NPS algorithm be integrated into our study design to improve consistency? You can use the FSA-NPS as a standardized, quantitative tool to score and compare products from both production systems. This addresses a key challenge in the field, as systematic reviews have found "no evidence of a difference in nutrient quality between organically and conventionally produced foodstuffs" when using simple nutrient comparisons [30]. The FSA-NPS provides a holistic profile.

- Data Collection: For each food item in your study, collect the nutritional data required by the FSA-NPS algorithm per 100g or 100ml: energy, saturated fat, total sugars, sodium, protein, fiber, and the percentage of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts [34] [35].

- Calculation: Apply the FSA-NPS algorithm to calculate a single score for each product. A lower score indicates better nutritional quality [34].

- Comparison: Statistically compare the mean FSA-NPS scores between the organic and conventional product groups. This provides an objective, validated metric for overall nutritional quality comparison, moving beyond isolated nutrient comparisons.

FAQ 3: We applied the FSA-NPS algorithm and found that some results appear counter-intuitive (e.g., a traditional product scores poorly). Does this invalidate the system? Not necessarily. This scenario often highlights a key principle: the system is designed for public health guidance, not to endorse all traditional or "natural" products.

- Check the Algorithm's Scope: The FSA-NPS is designed for "across-the-board" comparison of all packaged and processed foods [34]. It may correctly identify products high in energy, saturated fats, sugars, or salt, even if they are traditional [37].

- Confirm Your Inputs: Double-check that the nutritional composition data for your products is accurate and that you have correctly applied the algorithm's specific modifications for categories like beverages, cheeses, and added fats [35].

- Contextualize Findings: Acknowledge that the system focuses on nutritional quality for chronic disease prevention. A product's cultural value or "natural" status does not automatically equate to a high nutritional quality within this specific framework [38].

FAQ 4: A reviewer has questioned the real-world effectiveness of the Nutri-Score system, citing publication bias. How should we address this in our manuscript? Acknowledge this ongoing scientific debate and present a balanced view based on the available evidence.

- Cite Supporting Evidence: Reference studies that demonstrate the label's effectiveness in laboratory and simulated shopping environments, such as its superior ability to help consumers rank products by nutritional quality compared to other labels [35].

- Acknowledge Limitations: Note that a recent systematic review found limited real-life impact on purchasing behavior and that effect sizes can be small, particularly for products in the middle (C, D) categories [39].

- Discuss Bias Concerns: Cite analyses that report a potential publication bias, where a large majority of studies supporting Nutri-Score are carried out by its developers, while a majority of independently conducted studies show unfavorable results [40]. Clearly state the affiliations of the studies you cite to ensure transparency.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Application of the FSA-NPS Algorithm to Composite Foods

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Wide variation in scores for similar composite foods (e.g., pizzas, sandwiches). | • Inaccurate estimation of the Fruits, Vegetables, Legumes, and Nuts (FVLN) component, which is a key "positive" element in the algorithm [35]. | • Do not estimate FVLN from nutritional proxies. Instead, obtain the precise percentage (by weight) from the product manufacturer or use detailed recipe-based calculations. |

| • Misapplication of the specific algorithm rules for borderline food categories. | • Consult the specific technical guides for the adapted FSA-NPS (FSAm-NPS). Adhere to the distinct rules for beverages, cheeses, and added fats [34] [35]. | |

| • Use of generic nutritional data that does not match the specific product formulation. | • Source product-specific data from food composition databases or direct chemical analysis where feasible, especially for key variables like fiber and sodium. |

Issue: Low Discriminatory Power in Specific Food Subgroups

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| All products within a narrow category (e.g., different brands of white bread) receive similar or identical scores. | • The nutritional composition of products within the category is genuinely very similar. | • Acknowledge the finding. The system may be working correctly, indicating a market segment with little nutritional variation. Report the lack of discrimination as a result. |

| • The algorithm's resolution is insufficient for making fine distinctions within very homogeneous, low-quality categories. | • Supplement the FSA-NPS analysis with additional, more specific nutrient analyses (e.g., free sugars vs. total sugars, specific fatty acid profiles) that are relevant to your research question [17]. | |

| • The product category is outside the system's optimal design scope (e.g., single-ingredient, unprocessed foods). | • Contextualize the results. For basic ingredients (e.g., fresh fruits, vegetables, plain meat), the primary differentiator may be the presence of pesticide residues or other non-nutritional factors, which FSA-NPS does not capture [41] [17]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating a Nutrient Profiling System for Comparative Studies

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing the content and convergent validity of a profiling system, based on the validation framework of the FSA-NPS/Nutri-Score [34] [35].

Objective: To determine if a nutrient profiling system correctly ranks foods by healthfulness (content validity) and aligns with independent dietary guidance (convergent validity).

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See the detailed table in Section 4.

- Software: Statistical analysis software (e.g., R, SPSS, SAS), data visualization tools.

- Primary Input: A comprehensive food composition database representing the food supply under study (e.g., a national database or a study-specific database of analyzed samples).

Methodology:

- Food Sampling & Data Collection:

- Assemble a representative sample of foods from the relevant food supply. The sample should cover all major food groups and subgroups.

- For each food, compile accurate data for all nutrients and components required by the profiling algorithm.

Calculation of Profile Scores:

- Apply the algorithm to each food item to compute its nutritional quality score.

Content Validity Assessment:

- Analysis: Examine the distribution of scores within and across pre-defined food groups (e.g., grains, dairy, meats, composite foods).

- Expected Outcome: The system should demonstrate a gradient of scores. For example, in the Nutri-Score validation, fruits and vegetables were predominantly classified in the healthier categories (A/B), while fats and sugars were concentrated in the less healthy categories (D/E) [35]. A system that fails to create such discrimination has poor content validity.

Convergent Validity Assessment:

- Analysis: Compare the system's classifications with official national dietary guidelines. Categorize foods as "Recommended" (to be consumed frequently), "Neutral," or "Limit" (to be consumed in moderation) based on the guidelines.

- Expected Outcome: A statistically significant majority of foods classified as "Recommended" by the guidelines should receive favorable scores from the profiling system, and vice-versa [34] [35].

Workflow Diagram: System Validation and Application

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for validating and applying a criterion-validated system like the FSA-NPS in a research study, such as comparing organic and conventional foods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the core components required to implement the FSA-NPS algorithm in a research setting.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment | Technical Specifications & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Composition Database | Provides the primary input data for calculating the FSA-NPS score for each food item. | • Must contain data per 100g/100ml for: energy (kJ), saturated fat (g), total sugars (g), sodium (mg), protein (g), fiber (g).• Critical: Must include or allow estimation of Fruits, Vegetables, Legumes, and Nuts (FVLN) as a percentage of total weight [35]. |

| FSA-NPS / FSAm-NPS Algorithm | The core computational formula that integrates positive and negative nutritional components into a single score. | • Use the officially documented and updated algorithm (e.g., the FSAm-NPS used for Nutri-Score) [34] [37].• Note specific rules for product categories like beverages, cheeses, and fats [35]. |

| Food Classification Framework | Allows for the analysis of score distributions within and across homogeneous food groups. | • Use a standardized system like the EUROFIR classification (e.g., "grain product" -> "breakfast cereals") to ensure consistent grouping and meaningful interpretation of results [35]. |

| Laboratory Analysis Kits | For generating primary nutritional data when reliable database information is unavailable. | • Required for analyzing: Dietary Fiber, Specific Sugar Profiles, Saturated Fatty Acids, and Sodium content. Essential for primary data collection in intervention studies [41]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software | To perform significance testing on score differences between groups and to assess the discriminatory power of the system. | • Used for tests like ANOVA (to compare mean FSA-NPS scores between organic and conventional groups) and Chi-Square (to compare distributions across nutritional classes) [35]. |

Designing Long-Term, Whole-Diet Substitution Trials to Assess Clinically Relevant Health Outcomes

Troubleshooting Common Challenges in Dietary Trials

FAQ: What are the most significant threats to the viability of long-term dietary intervention trials?

High attrition rates and difficulties maintaining participant compliance are major threats to trial viability. One 12-month dairy intervention trial reported a 49.3% attrition rate, fundamentally threatening the study's statistical power. The primary factors contributing to dropout included: inability to comply with dietary requirements (27.0%), health problems or medication changes (24.3%), and excessive time commitment (10.8%) [42].

FAQ: How can we mitigate participant dropout in long-term studies?

Implementing a run-in period before randomization helps assess participant motivation, commitment, and availability. Maintaining regular contact during control phases, minimizing time commitment, providing flexibility with dietary requirements, and facilitating positive experiences also improve retention. Stringent monitoring of diet through logs and regular check-ins can further enhance adherence [42].

FAQ: What biases are particularly problematic in dietary trials?

Dietary trials are susceptible to several unique biases. Selection bias occurs when participants with certain dietary habits or beliefs are more likely to enroll. Compliance bias emerges when pre-existing diet beliefs and behaviors influence a participant's ability to adhere to the protocol. Participant expectancy effects can shape clinical responses based on prior knowledge of the intervention. Dietary collinearity presents another challenge, where changing one dietary component leads to compensatory changes in others, confounding results [43].

Methodological Guidance for Robust Trial Design

FAQ: What are the key considerations when choosing a mode of dietary intervention delivery?

The choice of delivery method involves trade-offs between precision, adherence, cost, and real-world applicability. The table below compares the primary approaches:

| Delivery Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding Trials (Providing all food) | High precision; Excellent adherence control; Direct compensation for dietary collinearity [43] | High cost; Limited real-world applicability; Logistically complex [43] | Highly controlled efficacy studies with sufficient budget [43] |

| Dietary Counseling (Guiding food choices) | High clinical applicability; Lower cost; Respects personal preferences [43] | Variable adherence; Imprecise intervention; Difficult to control for collinearity [43] | Pragmatic effectiveness trials and clinical practice translation [43] |

| Hybrid Approaches (Combining methods) | Balances control and practicality; Can improve adherence | Still faces some limitations of both methods | Trials needing moderate control with better real-world application |

FAQ: How can we improve dietary adherence and acceptability in long-term trials?

Incorporating cultural and taste preferences is crucial. Using herbs and spices can maintain the acceptability of healthier food options without adding excessive saturated fat, sodium, or sugar. Providing detailed recipes and preparation methods improves intervention reproducibility and translatability. Collaboration with specialist dietitians allows for personalization based on food preferences, cultural and religious practices, and socioeconomic restrictions while maintaining nutritional adequacy [43] [44].

FAQ: What design aspects are critical for a robust whole-diet substitution trial?

- Crossover vs. Parallel Design: Crossover designs (where participants act as their own controls) reduce required sample size but risk carryover effects and require careful consideration of washout periods [42] [43].

- Control Group Selection: A well-designed control diet is essential. For organic versus conventional comparisons, this may involve matching for all variables except the farming method [43].

- Blinding: While full blinding is challenging in dietary trials, partial blinding (e.g., to the study hypothesis) and using neutral language can mitigate expectancy effects [43].

- Outcome Measurement: Use high-quality, clinically relevant, and validated endpoints. For microbiome-related outcomes, consider the rapidity of diet-induced changes and substantial temporal variability [43].

Experimental Protocols for Diet-Metabolic Health Assessments

Protocol: Assessing Cardiometabolic and Cognitive Health Outcomes in a 12-Month Dietary Intervention

This protocol is adapted from a published 12-month, randomised, two-way crossover study [42].

1. Participant Recruitment and Screening:

- Target Population: Recruit overweight/obese adults (BMI ≥25 kg/m²) with habitually low intake of the food of interest (e.g., <2 dairy servings/day).

- Exclusion Criteria: Include current smokers, pre-existing metabolic diseases (diabetes, CVD, liver/renal disease), food allergies/intolerances related to the intervention, use of medications affecting outcomes, and pregnancy.

- Recruitment Strategies: Utilize local newspaper advertisements, public noticeboards, and television segments to reach potential volunteers [42].

2. Baseline and Follow-up Assessments: Conduct comprehensive assessments at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months.

- Anthropometry & Body Composition: Measure body weight, waist circumference, and percentage total and abdominal body fat (via DEXA).

- Blood Pressure & Biochemistry: Assess systolic/diastolic blood pressure and analyze fasting plasma glucose, triglycerides, HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol.

- Metabolic Rate: Measure resting metabolic rate by indirect calorimetry.

- Vascular Health: Assess arterial compliance via pulse wave velocity.

- Cognitive Function: Administer a battery of neuropsychological tests (approx. 1-1.5 hours) assessing processing speed, attention, memory, executive function, etc [42].

3. Dietary Intervention Delivery:

- High-Intake Phase: Provide participants with all required intervention foods (e.g., 4 servings/day) weekly or fortnightly. Use coolers and ice bricks for transport. Provide verbal and written serving size instructions.

- Low-Intake (Control) Phase: Instruct participants to limit intake to habitual low levels (e.g., 1 serving/day). Do not provide food during this phase.

- Dietary Compliance Monitoring: Use daily food logs during the high-intake phase. Offer nutritional counseling to help participants incorporate intervention foods without increasing total energy intake [42].

4. Data Collection and Monitoring:

- Dietary Intake: Collect 3-day weighed food records, food frequency questionnaires, and 3-day physical activity diaries at each assessment point.

- Participant Retention: Send reminder letters 2 weeks before assessments and make reminder phone calls the week prior. Follow a strict protocol (max. 3 calls + 1 letter) for non-attendance before considering withdrawal [42].

Diagram: 12-Month Crossover Trial Workflow for Whole-Diet Intervention

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Intervention Trials

| Item/Category | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Tools | To quantify habitual intake and monitor compliance during the trial. | 3-day weighed food records [42], Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) [42], 24-hour dietary recalls. |

| Food Provision System | To ensure consistent quality and dosage of the intervention diet. | Cooler bags, ice bricks for transport [42], standardized food portions. |

| Anthropometry Kit | To measure body composition changes as primary/secondary outcomes. | DEXA for body fat [42], stadiometer, calibrated scales, waist circumference tape. |

| Phlebotomy & Blood Analysis | To assess cardiometabolic biomarkers. | Fasting blood samples for glucose, lipids (HDL, LDL, triglycerides) [42]. |

| Cognitive Assessment Batteries | To evaluate cognitive health outcomes. | Neuropsychological tests for memory, attention, executive function [42]. |

| Physical Activity Monitors | To control for confounding from energy expenditure. | 3-day physical activity diaries [42], accelerometers. |

Logical Framework for Designing a Dietary Substitution Trial

Diagram: Logical Flow for Trial Design Decision-Making

This technical support center provides troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers integrating Dried Blood Spot (DBS) testing and metabolic profiling into nutritional studies. The content is specifically framed to support investigations aimed at improving consistency in comparing the biological effects of organic versus conventional foods. The following FAQs, protocols, and data summaries are designed to address key experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

1. How does the metabolic coverage of DBS compare to plasma, and is it suitable for detecting nutritional biomarkers?

While DBS samples contain whole blood (including blood cells), they typically yield a lower number of detectable metabolites (~700-900) compared to plasma (~1200) [45]. However, all major metabolic pathways and over 95% of the sub-pathways detectable in plasma are also covered by DBS analysis [45]. DBS is particularly well-suited for detecting certain nutritional and inflammatory markers, including:

- Carbohydrates from nucleotide sugars and glycolysis.

- Amino acids related to glutathione metabolism.

- Nucleotides in purine metabolism.

- Cofactors and vitamins such as NAD+.

- Inflammatory markers like eicosanoids and docosanoids [45]. Well-characterized metabolic signatures of disease and dietary intake identified in plasma are generally maintained in DBS, making it a valid matrix for nutritional biomonitoring [45].

2. What are the critical factors affecting metabolite stability in DBS samples, and how can we mitigate them?

Metabolite stability is highly dependent on storage temperature and the chemical nature of the metabolite [46]. Temperature has a more significant impact than storage duration, with warmer conditions accelerating degradation [45].

- Stable Metabolites: 69 metabolites, including 15 lipids, 9 amino acids, and 8 carbohydrates, have been shown to remain stable (RSD < 15%) for 21 days even at temperatures up to 40°C [46].

Unstable Metabolites: Certain classes are highly susceptible to degradation, particularly at higher temperatures. These include:

Mitigation Strategies:

- Consistent Handling: Process all samples (cases and controls) identically [45].

- Optimal Storage: Store and ship samples at -80°C in gas-impermeable bags with desiccant packs. This is the best practice for preserving a wide range of metabolites [45].

- Rapid Analysis or Equilibration: If cold chain is broken, note that most stability changes occur rapidly and stabilize after about three weeks. Metabolon recommends not analyzing samples until they have been stored for at least three weeks post-collection to allow metabolite levels to equilibrate [45].

3. Our study involves remote, at-home sample collection. What are the best practices for DBS collection to ensure data quality?

Successful at-home collection is feasible but requires clear protocols for participants [45].

- Improve Blood Flow: Instruct participants to drink water 30 minutes before collection and keep their hands warm with their hand below waist level before and during collection [45].

- Spot Size: Allow a large blood droplet to form (close to dripping) before application. A single spot should be larger than 7 mm in diameter. Do not "milk" the finger, as this can cause hemolysis [45].

- Spotting: Apply only one droplet per designated circle on the DBS card. If a spot seems too small, wait for a larger droplet and use the next circle. Two full spots are typically required for a comprehensive metabolomic analysis [45].

4. From a precision nutrition standpoint, how can metabolomic data objectively improve comparisons between organic and conventional diets?

Self-reported dietary data is prone to significant inaccuracies [47]. Metabolomics provides an objective snapshot of an individual's nutritional status, capturing the complex biological response to dietary intake beyond what questionnaires can achieve [48] [47].

- Biomarkers of Food Intake: Metabolites can distinguish between dietary patterns.

- Metabotyping: Individuals can be grouped based on their metabolic phenotype (metabotype), which influences their response to dietary interventions [47]. This can help stratify study populations to reduce inter-individual variability and identify subgroups that may respond differently to organic or conventional diets. For example, individuals with "unfavorable" baseline metabotypes may show the greatest metabolic improvement from a dietary intervention [47].

Key Experimental Data for Study Design

Table 1: Metabolite Stability in DBS Under Various Storage Conditions

Data derived from multi-platform untargeted metabolomics analysis (based on [46]).

| Metabolite Category | Stability at 4°C (21 days) | Stability at 25°C (21 days) | Stability at 40°C (21 days) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids | Mostly Stable | Stable (<14 days) | Becomes Unstable (>14 days) | Chemical transformations at high temps [46]. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | Variable | Unstable | Unstable | Major driver of profile separation; susceptible to hydrolysis/oxidation [46]. |

| Triglycerides (TAGs) | Variable | Unstable | Unstable | Major driver of profile separation; susceptible to hydrolysis/oxidation [46]. |

| LysoPCs | Stable | Increased Intensity | Increased Intensity | Elevated intensities observed at higher temperatures [46]. |

| Carbohydrates | Stable | Variable | Variable | Instability observed over 14 days at 25°C & 40°C [46]. |

| Nucleotides, Peptides, SMs | Stable | Stable | Stable | Generally stable across temperature ranges [46]. |

| Number of Stable Metabolites (of 353) | 188 | 130 | 81 | 69 metabolites stable across all three temperatures [46]. |

Table 2: DBS vs. Plasma for Metabolomic Analysis

A comparison of matrix properties and suitability for nutritional studies (based on [45]).

| Parameter | Dried Blood Spot (DBS) | Venous Plasma/Serum |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume | Low (finger-prick) | High (venipuncture) |

| Collection | Minimally invasive; suitable for remote, self-collection | Invasive; requires trained phlebotomist |

| Transport/Storage | Stable at ambient temp for many metabolites; easy shipping [47] | Requires cold chain (refrigeration/frozen) |

| Metabolite Coverage | ~700-900 metabolites [45] | ~1200 metabolites [45] |

| Pathway Coverage | >95% of plasma sub-pathways [45] | Standard for biomarker discovery |

| Key Strengths | Ideal for longitudinal & remote studies; good for cellular metabolites (e.g., purines, NAD+) [45] | Higher metabolite coverage; traditional gold standard |

| Key Limitations | Susceptible to oxidation of certain lipids; hematocrit effects can be a factor [45] | Logistically complex and expensive for large-scale studies |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validated Workflow for DBS Metabolomic Analysis in Nutritional Studies

This protocol is adapted from established LC-HRMS workflows for exposomic and metabolomic analysis [49].

1. Sample Collection:

- Material: Use standardized filter paper cards (e.g., Whatman 903 Protein Saver Card) [45].

- Procedure: Follow best practices for finger-prick collection as outlined in the FAQ section. Ensure complete saturation of spots and air-dry for a minimum of 3 hours at room temperature without stacking or exposing to direct heat sources [45].

2. Sample Storage and Transportation:

- Place dried cards in gas-impermeable zip-lock bags with a desiccant pack.