Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) Models in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) models, which establish predictive relationships between a drug's laboratory dissolution and its in vivo pharmacokinetic behavior.

Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) Models in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) models, which establish predictive relationships between a drug's laboratory dissolution and its in vivo pharmacokinetic behavior. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content explores foundational principles, methodological approaches for building robust correlations, strategies for troubleshooting complex formulations, and frameworks for regulatory validation. By synthesizing current research and regulatory perspectives, this guide serves as a critical resource for leveraging IVIVC to streamline formulation optimization, reduce development costs, support bioequivalence assessments, and accelerate the translation of drug products from the lab to the clinic.

Understanding IVIVC: Core Concepts, Regulatory Definitions, and Correlation Levels

In the realm of pharmaceutical development, In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) serves as a critical scientific bridge, connecting a drug's laboratory performance to its behavior in the human body. Regulatory authorities recommend establishing IVIVC models for most modified-release dosage forms to streamline development and enhance formulation strategies [1]. According to the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), IVIVC is defined as "the establishment of a rational relationship between a biological property, or a parameter derived from a biological property produced by a dosage form, and a physicochemical property or characteristic of the same dosage form" [2]. In parallel, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides a more application-oriented definition, describing IVIVC as "a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form and a relevant in vivo response" [2] [1]. While the USP emphasizes establishing a rational relationship between broadly defined properties, the FDA specifically focuses on the predictive capability of the mathematical model for in vivo performance.

The primary advantage of IVIVC lies in its ability to provide a mechanism for evaluating how changes in in vitro drug release affect in vivo drug absorption. This predictive capability can reduce the need for certain clinical bioequivalence studies, supporting more ethical research and accelerating development timelines [1]. Furthermore, IVIVC enhances understanding of drug product characteristics, facilitates broader acceptance criteria, and helps optimize formulation stability throughout the product lifecycle [1].

Regulatory Framework and Correlation Levels

Comparative Analysis of USP and FDA Perspectives

The following table summarizes the key distinctions between the USP and FDA perspectives on IVIVC:

Table 1: Comparison of USP and FDA Perspectives on IVIVC

| Aspect | USP Perspective | FDA Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Establishment of a rational relationship between a biological property and a physicochemical property [2]. | A predictive mathematical model between an in vitro property and a relevant in vivo response [2] [1]. |

| Primary Emphasis | Broad relationship establishment, including various biological and physicochemical parameters [2]. | Predictive capability and model application for bioavailability/bioequivalence assessments [1]. |

| In Vivo Response | Can be any "biological property produced by a dosage form" [2]. | Typically plasma drug concentration, amount absorbed, or other PK parameters (e.g., Cmax, AUC) [2] [1]. |

| Regulatory Application | General standard for relationship establishment [2]. | Supports biowaivers, sets dissolution specifications, and justifies formulation changes [1]. |

Levels of IVIVC and Their Regulatory Acceptance

Regulatory guidelines recognize multiple levels of IVIVC, which differ in complexity, predictive power, and regulatory utility. The most common categories are Levels A, B, and C.

Table 2: Levels of IVIVC and Their Regulatory Implications

| Level | Definition | Predictive Value | Regulatory Acceptance & Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level A | A point-to-point correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption [1]. | High – predicts the full plasma concentration-time profile [1]. | Most preferred by FDA; supports biowaivers and major formulation changes. Requires ≥2 formulations with distinct release rates [1]. |

| Level B | A statistical correlation using mean in vitro and mean in vivo parameters [2] [1]. | Moderate – does not reflect individual pharmacokinetic curves [1]. | Less robust; usually requires additional in vivo data. Not suitable for quality control specifications [1]. |

| Level C | A correlation between a single in vitro time point and one pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., Cmax, AUC) [2] [1]. | Low – does not predict the full PK profile [1]. | Least rigorous; not sufficient for biowaivers or major changes. May support early development insights [1]. |

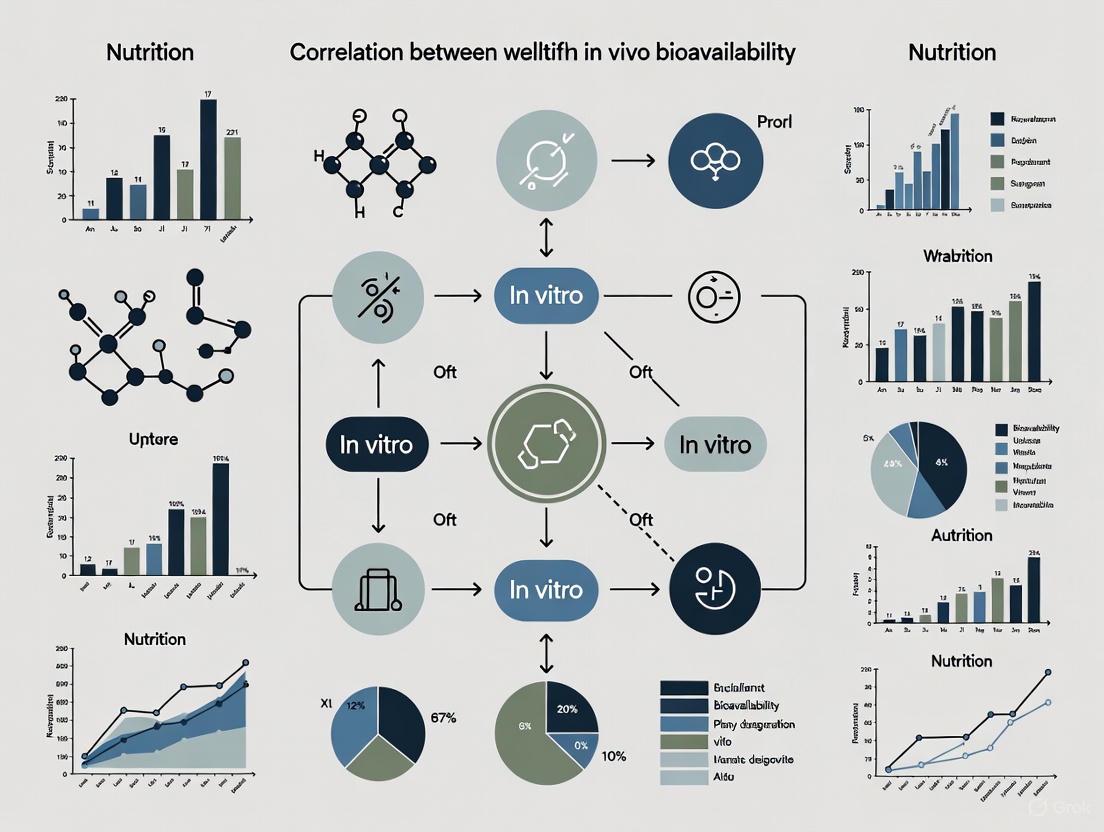

Diagram 1: IVIVC Levels and Predictive Value Hierarchy

Experimental Protocols for IVIVC Development

Development of Level A IVIVC for Extended-Release Tablets

A robust Level A IVIVC was successfully developed for lamotrigine extended-release (ER) 300 mg tablets, establishing patient-centric quality standards for dissolution. The systematic approach involved multiple experimental and computational phases [3].

Materials and Methods:

- Formulations: Marketed lamotrigine ER tablets (Lamictal XR 300 mg) as reference, with in-house manufactured slow, medium, and fast-release formulations for IVIVC validation [3].

- Dissolution Testing: Comprehensive dissolution profiling using USP Apparatus II (paddle) and III (reciprocating cylinder) under various conditions, including biorelevant and standard compendial media with different pH levels and hydrodynamic parameters [3].

- Analytical Techniques: HPLC analysis of dissolution samples with validated methods to determine lamotrigine concentration [3].

- PBPK Modeling: Development and verification of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model using plasma lamotrigine profiles from intravenous solution and oral immediate-release tablets. Model verification showed accurate prediction of Cmax and AUC with confidence levels exceeding 95% [3].

Key Experimental Workflow: The experimental workflow for establishing a predictive IVIVC involves multiple interconnected stages, as illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Comprehensive IVIVC Development Workflow

Results and Validation: The study demonstrated that dissolution in standard compendial media using USP Apparatus II established a robust Level A IVIVC. The model passed both internal and external validation criteria with prediction errors below 10%, confirming its predictive capability. Using these dissolution conditions, patient-centric quality standards (PCQS) were successfully derived as ≤10% release at 2 h, ≤45% at 6 h, and ≥80% at 18 h [3].

Universal In Vivo Predictive Dissolution Method for Immediate-Release Tablets

For acyclovir immediate-release tablets, a universal in vivo predictive dissolution (IPD) method was developed using a mini-vessel/mini-paddle apparatus, guided by computational simulations in a PBPK model [4].

Materials and Methods:

- Formulations: Acyclovir IR tablets (200 mg and 800 mg strengths), including reference (Zovirax) and generic products [4].

- Dissolution Apparatus: Miniaturized version of USP Type II apparatus with 135 mL or 150 mL volumes, compared with standard USP Type II apparatus with 900 mL volume [4].

- Dissolution Media: Hydrochloric acid, pH 2.0, at varying stirring rates (100, 125, 150 rpm) [4].

- PBPK Modeling: Adaptation of a previously built PBPK model for acyclovir IR tablets in GastroPlus software, incorporating optimized effective permeability values and transporter-mediated kinetics [4].

Experimental Findings: The research revealed that dissolution of 800 mg acyclovir tablets in 900 mL of media largely overpredicted observed plasma profiles due to poor resemblance of non-sink conditions in the human lumen. Conversely, dissolution in the mini-vessel filled with 135 mL of HCl, pH 2.0, at 150 rpm produced accurate predictions of plasma profiles without affecting successful predictions with the lowest strength tablets. This method was validated through in-human and virtual bioequivalence studies, confirming its predictive potential as a universal IPD method for acyclovir immediate-release tablets [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for IVIVC Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function in IVIVC Development | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| USP Apparatus II (Paddle) | Standard dissolution apparatus for oral dosage forms under controlled hydrodynamic conditions [3]. | Dissolution testing of lamotrigine ER tablets in compendial media [3]. |

| USP Apparatus III (Reciprocating Cylinder) | Alternative dissolution apparatus with different hydrodynamics, useful for establishing bio-relevant conditions [3]. | Comparative dissolution profiling of lamotrigine ER tablets [3]. |

| Mini-Vessel/Mini-Paddle Apparatus | Miniaturized dissolution apparatus with smaller volumes (135-150 mL) to better simulate physiological conditions [4]. | Development of IPD method for acyclovir 800 mg tablets under non-sink conditions [4]. |

| Biorelevant Media | Dissolution media simulating gastrointestinal fluids (e.g., FaSSIF, FeSSIF) to enhance physiological relevance [3]. | Evaluation of dissolution characteristics under simulated fasted and fed states [3]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software | Computational platform (e.g., GastroPlus) for developing and verifying physiologically based pharmacokinetic models [3] [4]. | Prediction of plasma concentration-time profiles and virtual bioequivalence studies [3] [4]. |

| HPLC-MS/MS Systems | Advanced analytical instrumentation for precise quantification of drug concentrations in dissolution samples and biological matrices [4]. | Bioanalysis of acyclovir in plasma samples from bioequivalence trials [4]. |

Applications and Future Perspectives

IVIVC continues to evolve beyond traditional oral dosage forms, expanding into complex delivery systems. For lipid-based formulations (LBFs), IVIVC development presents unique challenges due to the complex interplay of digestion, permeation, and dynamic solubilization processes [2]. Similarly, for long-acting injectables (LAIs) based on poly(lactide-co-glycolide), IVIVC establishment requires consideration of drastically different circumstances compared to oral formulations, including month-long release durations and more complex release mechanisms [5].

The future of IVIVC is increasingly intertwined with advanced modeling approaches and emerging technologies. The convergence of artificial intelligence-driven modeling platforms, microfluidics, organ-on-a-chip systems, and high-throughput screening assays holds immense potential for augmenting the predictive power and scope of IVIVC studies [1]. Furthermore, the integration of IVIVC with Quality by Design (QbD) frameworks and model-informed drug development (MIDD) approaches enables the establishment of clinically relevant dissolution specifications that better account for variability in patient physiology and drug absorption [3] [4]. These advancements are paving the way for more personalized drug therapies while simultaneously accelerating drug development timelines.

In vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is a pivotal scientific framework in pharmaceutical development, defined as a predictive mathematical model that describes the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form (typically the rate or extent of drug dissolution) and a relevant in vivo response (such as plasma drug concentration or amount absorbed) [1] [6]. The primary objective of establishing an IVIVC is to use in vitro drug release profiles as a surrogate for in vivo performance, enabling researchers to predict how a drug will behave in patients based on laboratory dissolution data [1]. This approach streamlines drug development, enhances formulation strategies, supports regulatory decisions, and can reduce the need for certain clinical bioequivalence studies [1].

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) formalized the modern classification system for IVIVC in its 1997 guidance "Extended Release Oral Dosage Forms: Development, Evaluation, and Application of In Vitro/In Vivo Correlations," which remains the definitive regulatory guidance on the topic [1]. This classification establishes a hierarchy of correlation levels—A, B, C, and Multiple Level C—categorized by their complexity, predictive power, and regulatory utility [1] [7]. Level A represents the most robust and predictive correlation, while Level C provides the most limited relationship. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize formulations and meet regulatory requirements for modified-release dosage forms.

The IVIVC Hierarchy: Levels and Regulatory Applications

The IVIVC hierarchy consists of distinct levels of correlation that differ significantly in their mathematical approaches, predictive capabilities, and regulatory acceptance. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of each level, including their definitions, methodologies, and applications within drug development.

Figure 1: IVIVC Hierarchy and Data Relationships. This diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships between in vitro data and in vivo parameters for each level of IVIVC, showing decreasing predictive power from Level A to Level C.

Level A Correlation: The Gold Standard

Level A correlation represents the highest and most informative category of IVIVC, establishing a point-to-point relationship between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption rates [1] [7]. This model is constructed by comparing the percentage of drug dissolved in vitro with the percentage of drug absorbed in vivo at corresponding time points, creating a direct correlation where in vitro dissolution rate serves as a surrogate for in vivo performance [7].

The mathematical foundation of Level A correlation typically involves deconvolution techniques to derive the in vivo absorption profile. Common approaches include:

- Wagner-Nelson method: Suitable for one-compartment models

- Loo-Riegelman method: Applicable to two-compartment models

- Model-independent deconvolution: Uses a reference formulation to determine the input function [7]

For a valid Level A correlation, regulatory guidelines typically require development using at least two formulations with different release rates (e.g., slow, medium, and fast) [1]. However, in specific cases where formulation changes are minimal, a single formulation may be acceptable. The predictive performance of the model is evaluated using internal validation, where prediction errors for key pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC and Cmax) should not exceed 10% on average, with no individual prediction error exceeding 15% [7].

Level A correlation provides the highest regulatory value and can support:

- Biowaivers for major formulation changes

- Changes in manufacturing site, method, or raw material supplies

- Minor formulation modifications

- Different product strengths using the same formulation [1] [7]

Level B Correlation: Statistical Moment Analysis

Level B correlation utilizes the principles of statistical moment analysis, comparing the mean in vitro dissolution time (MDTvitro) to either the mean residence time (MRT) or mean in vivo dissolution time (MDTvivo) [7]. This approach uses the entire dissolution and plasma concentration dataset but does not establish a point-to-point relationship between in vitro and in vivo profiles [1].

While Level B correlation incorporates complete in vitro and in vivo data, it represents a less predictive approach than Level A because different in vivo plasma concentration curves can produce similar mean residence time values [7]. Consequently, Level B correlation does not uniquely reflect the actual shape of the in vivo plasma concentration curve and cannot predict the complete drug absorption profile [1].

Due to these limitations, Level B correlation has limited regulatory utility and is generally not sufficient to justify biowaivers or support significant post-approval changes (SUPAC) without additional in vivo data [1] [7]. It may serve as an intermediate tool during formulation development but lacks the predictive precision required for definitive regulatory decisions.

Level C and Multiple Level C Correlations

Level C correlation establishes a single-point relationship between one dissolution time point (e.g., t50%, t90%) and one pharmacokinetic parameter (such as AUC, Cmax, or Tmax) [1] [7]. This represents the simplest and least informative form of IVIVC, as it only identifies a partial relationship between absorption and dissolution without reflecting the complete shape of the plasma concentration-time curve [7].

Multiple Level C correlation expands on the basic Level C approach by correlating one or several pharmacokinetic parameters with the amount of drug dissolved at multiple time points throughout the dissolution profile [7]. This multi-point approach should include at least three dissolution time points covering the early, middle, and late stages of the dissolution profile to provide a more comprehensive assessment than single-point Level C correlation [7].

While Multiple Level C correlation offers more information than single-point Level C, both approaches have limited regulatory applications:

- Level C may aid in formulation selection during early development stages

- Multiple Level C may potentially support biowaivers if established over the entire dissolution profile and with appropriate pharmacokinetic parameters [7]

- Neither approach alone is sufficient to predict the complete in vivo performance of drug products [1]

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of IVIVC Levels

| Aspect | Level A | Level B | Level C | Multiple Level C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Point-to-point correlation between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption [1] [7] | Statistical moment analysis comparing mean in vitro dissolution time with mean in vivo residence/time [1] [7] | Single-point relationship between one dissolution time point and one PK parameter [1] [7] | Relationship between PK parameters and drug dissolved at several time points [7] |

| Predictive Value | High – predicts full plasma concentration-time profile [1] | Moderate – does not reflect individual PK curves [1] | Low – does not predict full PK profile [1] | Moderate – more predictive than Level C but less than Level A [7] |

| Mathematical Basis | Deconvolution (Wagner-Nelson, Loo-Riegelman) [7] | Statistical moment analysis [7] | Linear regression between single parameters [7] | Multivariate regression between multiple parameters [7] |

| Data Utilization | Uses entire dissolution and plasma profile [7] | Uses entire dissolution and plasma profile [7] | Uses limited data points [7] | Uses multiple but not complete data points [7] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Most preferred; supports biowaivers and major changes [1] | Less robust; usually requires additional in vivo data [1] | Least rigorous; not sufficient for biowaivers [1] | May support biowaivers if correlation is strong [7] |

| Primary Applications | Surrogate for bioequivalence, SUPAC changes, setting dissolution specifications [1] [7] | Limited regulatory use, primarily for internal development [1] | Early formulation screening and development [7] | Formulation optimization with more insight than Level C [7] |

Experimental Protocols for IVIVC Development

Developing a robust IVIVC requires carefully designed experiments and systematic data analysis. The following section outlines standardized protocols for establishing different levels of correlation, with particular emphasis on Level A IVIVC as the regulatory gold standard.

Formulation Development and In Vitro Testing

The initial stage involves creating formulations with intentionally varied release rates to provide the necessary data range for correlation development.

- Formulation Design: Develop at least two or three formulations with distinct drug release rates (typically slow, medium, and fast) [1] [7]. These formulations should differ only in the critical factors affecting release rate (e.g., polymer composition, excipient ratios, coating thickness) while maintaining similar composition otherwise.

- In Vitro Dissolution Testing:

- Use biorelevant dissolution media that simulate gastrointestinal conditions (e.g., pH 1.2, 4.5, 6.8, or FaSSIF/FeSSIF) [8]

- Employ appropriate apparatus such as USP I (basket), USP II (paddle), or USP IV (flow-through cell) based on dosage form characteristics [8]

- Ensure sink conditions and demonstrate discriminatory power between formulations with different release rates [8]

- For extended-release formulations, aim for a dissolution profile where ≥80% drug release occurs over 12-24 hours [8]

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Studies

Conduct pharmacokinetic studies in human subjects or appropriate animal models to characterize the in vivo performance of each formulation.

- Study Design: Implement a single-dose, randomized crossover study comparing test formulations with different release rates and including an immediate-release reference product for deconvolution [7]

- Subject Selection: Enroll healthy adult volunteers (typically n=12-36) following ethical guidelines and good clinical practice standards

- Sample Collection: Obtain frequent blood samples (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36, 48 hours) to adequately characterize the plasma concentration-time profile [7]

- Bioanalytical Methods: Use validated HPLC-MS/MS or HPLC-UV methods to quantify drug concentrations in plasma samples with appropriate precision and accuracy [7]

Data Analysis and Model Development

The core of IVIVC development involves mathematical manipulation of in vitro and in vivo data to establish predictive relationships.

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Calculate key PK parameters including AUC, Cmax, and Tmax using non-compartmental analysis [7]

- Deconvolution: Apply model-dependent (Wagner-Nelson for one-compartment; Loo-Riegelman for two-compartment) or model-independent deconvolution methods to determine the in vivo absorption time course [7]

- Correlation Establishment:

- For Level A: Plot fraction absorbed in vivo versus fraction dissolved in vitro to establish point-to-point correlation [7]

- Apply time-scaling approaches (e.g., Levy's plot) if in vitro and in vivo timescales differ [7]

- For Level B: Calculate and compare mean dissolution time (MDT) in vitro with mean residence time (MRT) in vivo [7]

- For Level C/Multiple Level C: Perform regression analysis between dissolution parameters (e.g., t50%, t90%) and PK parameters (AUC, Cmax) [7]

Model Validation

Assess the predictive performance of the IVIVC model using internal validation techniques.

- Prediction Validation: Use the established IVIVC model to predict in vivo pharmacokinetic profiles from in vitro dissolution data [7]

- Acceptance Criteria: Evaluate prediction errors for Cmax and AUC; according to regulatory standards, mean prediction error should be ≤10% and individual prediction error should be ≤15% [7]

- For Level A correlation, if these criteria are met, the model can support biowaivers for post-approval changes without additional clinical studies [7]

Figure 2: IVIVC Development Workflow. This flowchart outlines the systematic process for developing and validating IVIVC models, from initial formulation design through to regulatory application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Establishing a robust IVIVC requires specific reagents, equipment, and methodologies. The following table details essential materials and their functions in IVIVC development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IVIVC Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications/Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Dissolution Apparatus | Simulates gastrointestinal conditions to measure drug release rate [8] | USP Apparatus I (basket), II (paddle), or IV (flow-through cell) [8] |

| Biorelevant Dissolution Media | Mimics physiological conditions of GI tract for predictive dissolution testing [8] | pH 1.2 (gastric), pH 4.5-6.8 (intestinal), FaSSIF/FeSSIF (fasted/fed state) [8] |

| Reference Standards | Bioanalytical method calibration and validation for drug quantification [7] | Certified reference materials with known purity and stability |

| HPLC-MS/MS Systems | Quantification of drug concentrations in biological samples (plasma) [7] | Validated methods with appropriate sensitivity, precision, and accuracy |

| Cryopreserved Hepatocytes | Metabolic stability assessment for IVIVE (in vitro-in vivo extrapolation) [9] | Species-specific (human, mouse, rat) with viability >70% [9] |

| Transwell Systems (Caco-2) | Assessment of drug permeability in early development [9] | Cell monolayer integrity with appropriate tightness markers [9] |

| Physicochemical Property Assays | Determination of key parameters affecting absorption (solubility, log P, pKa) [6] | Kinetic solubility, shake-flask method, potentiometric titration |

The hierarchy of IVIVC correlations provides a structured framework for relating in vitro drug release to in vivo performance, with each level offering distinct advantages and limitations. Level A correlation stands as the gold standard for regulatory applications, enabling biowaivers and supporting formulation changes without additional clinical studies. Level B offers limited utility despite using complete datasets, while Level C and Multiple Level C serve primarily in early development stages. The successful implementation of IVIVC requires careful experimental design, appropriate statistical analysis, and rigorous validation. When properly established, particularly with Level A correlation, IVIVC significantly enhances formulation development efficiency, reduces animal and human testing, and strengthens regulatory submissions—ultimately accelerating the delivery of quality drug products to patients.

In the pursuit of efficient drug development, the establishment of a predictive in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is paramount. An IVIVC is defined as a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an oral dosage form's in vitro property (typically the rate or extent of drug dissolution) and a relevant in vivo response (such as plasma drug concentration or amount absorbed) [6]. The primary objective of developing an effective IVIVC is to enable the prediction of in vivo drug performance based on in vitro behavior, thereby reducing the need for extensive clinical studies and accelerating the development of robust drug products [6].

The efficacy of this correlation heavily depends on a thorough understanding of a drug's fundamental physicochemical properties. Among these, solubility, pKa, and particle size play disproportionately critical roles. They collectively govern the journey of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from its release from the dosage form to its dissolution in the gastrointestinal fluids and subsequent absorption across the intestinal membrane. For poorly water-soluble drugs (PWS), which constitute more than 50% of commercially available oral drugs and an even higher percentage of new chemical entities, these factors become the primary determinants of bioavailability [10] [11]. This review objectively examines the experimental data and mechanistic roles of these three key properties in the context of IVIVC, providing a comparative framework for researchers in drug development.

Solubility: The Fundamental Prerequisite for Absorption

Mechanistic Role in Bioavailability

Solubility is the concentration of a drug in a saturated solution at a specific temperature and pH, representing the maximum amount of drug that can remain dissolved in the gastrointestinal (GI) fluid. It is the foundational step in the drug absorption cascade, as a drug must be in solution to permeate the intestinal wall [6]. The critical nature of solubility is captured in the Noyes-Whitney equation (Equation 1), which models dissolution rate [6].

Equation 1: Noyes-Whitney Dissolution Equation [ \frac{dM}{dt} = \frac{D \times S \times (Cs - Cb)}{h} ] Where:

- ( \frac{dM}{dt} ): Dissolution rate

- ( D ): Diffusion coefficient of the drug

- ( S ): Surface area of the drug particle

- ( C_s ): Drug solubility in the dissolution medium

- ( C_b ): Drug concentration in the bulk medium at time t

- ( h ): Thickness of the diffusion layer

This equation illustrates that the dissolution rate is directly proportional to the drug's solubility (( Cs )). Under sink conditions (( Cb ) is negligible), the equation simplifies further, highlighting that the dissolution rate is directly driven by solubility [6]. The Maximum Absorbable Dose (MAD) model (Equation 2) further quantifies the direct relationship between solubility and the potential for oral absorption [6].

Equation 2: Maximum Absorbable Dose (MAD) [ MAD = S \times K_a \times SIWV \times SITT ] Where:

- ( S ): Solubility at pH 6.5 (mg/mL)

- ( K_a ): Intestinal absorption rate constant (min⁻¹)

- ( SIWV ): Small intestinal water volume (≈ 250 mL)

- ( SITT ): Small intestinal transit time (≈ 3 hours)

Experimental Data and Comparison

Table 1: Impact of Solubility on Key Bioavailability Parameters

| Solubility Class | Typical Dose Number (D₀) | Expected Absorption Efficiency | Key Formulation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Solubility | D₀ < 1 | High and consistent absorption; IVIVC often straightforward | Chemical stability, controlled release |

| Low Solubility | D₀ > 1 | Highly variable, incomplete absorption; complex IVIVC | Enhancing dissolution, maintaining supersaturation, preventing precipitation |

The Dose Number (D₀) is a key parameter that relates the dose to solubility, calculated as the ratio of dose concentration to solubility [6]. A dose number greater than 1 indicates that the drug dose is insufficiently soluble to dissolve completely in the available GI fluid volume, signaling potential bioavailability problems.

Standard Experimental Protocols

Shake-Flask Method is the standard for equilibrium solubility measurement.

- Preparation: An excess of the drug is added to a vial containing the dissolution medium (e.g., simulated gastric or intestinal fluid).

- Equilibration: The vial is sealed and shaken at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a sufficient time (typically 24-72 hours) to reach equilibrium.

- Separation: The solution is filtered or centrifuged to separate undissolved solid.

- Quantification: The concentration of the drug in the saturated supernatant is quantified using a validated analytical method, such as UV spectrophotometry or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- pH Profiling: The process is repeated across a physiologically relevant pH range (1.2 to 7.5) to understand pH-dependent solubility.

pKa: The Master of Ionization and pH-Dependent Behavior

Mechanistic Role in Bioavailability

The acid dissociation constant (pKa) determines the pH at which a molecule is 50% ionized. This is critically important because the unionized form of a drug typically exhibits higher membrane permeability than its ionized counterpart, a principle known as the pH-partition hypothesis [6]. The human GI tract possesses a significant and dynamic pH gradient, ranging from highly acidic in the stomach (pH ~1.5) to neutral in the small intestine (pH ~6.5) and more basic in the colon (pH ~7-8) [6]. As a drug transits through these different environments, its pKa dictates its ionization state, thereby influencing both its solubility and permeability in a reciprocal manner.

The fraction of a drug that is unionized can be calculated using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

- For weak acids: ( \text{pH} = \text{pKa} + \log\left(\frac{[\text{Ionized}]}{[\text{Unionized}]}\right) )

- For weak bases: ( \text{pH} = \text{pKa} + \log\left(\frac{[\text{Unionized}]}{[\text{Ionized}]}\right) )

A weakly basic drug with a pKa of 4.5 will be highly ionized (and thus more soluble) in the stomach but will become largely unionized (and more permeable) upon entering the small intestine. This interplay is a major source of complexity in developing IVIVCs, as dissolution tests at a single pH may not accurately reflect the in vivo environment [6].

Experimental Data and Comparison

Table 2: Impact of pKa and Ionization Class on Drug Absorption

| Ionization Class | Absorption Site (pH) | Primary Limiting Factor | IVIVC Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Acid (pKa 3-5) | Stomach (pH 1-3) | Permeability in intestine (ionized form) | Dissolution media must reflect gastric pH |

| Weak Base (pKa 6-8) | Small Intestine (pH 6-8) | Solubility in intestine (precipitation risk) | Biphasic dissolution may be necessary |

| Amphoteric | Varies with pH | Complex solubility/permeability profile | Requires multi-pH dissolution profiling |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Potentiometric Titration is a standard method for pKa determination.

- Setup: A known amount of the drug compound is dissolved in a container of water or a water-co-solvent mixture, maintained at a constant temperature (25°C) and ionic strength.

- Titration: For a basic compound, a strong acid (e.g., HCl) is added incrementally. For an acidic compound, a strong base (e.g., NaOH) is used.

- Measurement: After each addition of titrant, the pH of the solution is measured precisely.

- Calculation: The pKa value is determined from the resulting titration curve by identifying the pH at the half-equivalence point or by using specialized software that performs a non-linear regression analysis on the data.

Particle Size: Engineering the Surface Area for Dissolution

Mechanistic Role in Bioavailability

Particle size directly influences the available surface area (S) for dissolution, as defined in the Noyes-Whitney equation. Reducing particle size increases the surface area-to-volume ratio, thereby enhancing the dissolution rate [6] [12]. This principle is the foundation for several formulation strategies aimed at improving the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. The relationship is not always linear, however, as very small particles (< 1-10 µm) can be susceptible to aggregation, which can counteract the benefits of increased surface area [12].

For drugs with very low solubility and high dose, micronization or nanosizing can be transformative. Nanoparticles not only increase surface area but can also lead to a transient increase in saturation solubility due to the Ostwald-Freundlich equation, further driving dissolution [12]. The success of drug delivery via particle size reduction depends heavily on the anatomical and biological barriers of the administration route, with different optimal size ranges for crossing the GI epithelium, skin, or blood-brain barrier [12].

Experimental Data and Comparison

Table 3: Impact of Particle Size Reduction on Bioavailability

| Particle Size Category | Typical Size Range | Key Mechanism | Reported Bioavailability Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macroscopic (Conventional) | > 100 µm | Standard dissolution | Baseline absorption; often low for BCS Class II/IV drugs |

| Micronized | 1 µm - 100 µm | Increased surface area (S) | Moderate improvement (e.g., 1.5 to 3-fold increase) |

| Nanosized | < 1 µm | Increased S + potential for increased saturation solubility | Significant improvement (e.g., 5 to 10-fold increase or more) |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Laser Diffraction Particle Size Analysis is a widely used technique.

- Dispersion: A representative sample of the drug powder is dispersed in a suitable medium (often a surfactant solution to prevent aggregation) and circulated through the measurement cell.

- Measurement: The sample is passed through a laser beam. The particles scatter light at an angle that is inversely related to their size.

- Detection: A detector array measures the intensity of light scattered at multiple angles.

- Analysis: Using optical models (like Mie Theory or Fraunhofer Approximation), the instrument software calculates the volume-based particle size distribution from the light scattering data, reporting metrics such as D10, D50 (median), and D90.

Integrated Workflow and Research Toolkit

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of experiments and the interconnected roles of solubility, pKa, and particle size in the early-stage development of an oral drug product, framed within the IVIVC context.

Diagram: Integrated workflow for IVIVC-focused physicochemical profiling.

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Key Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Gastric/Intestinal Fluids (e.g., FaSSIF, FeSSIF) | Biorelevant dissolution media mimicking the pH, buffer capacity, and surface-active components of GI fluids. | Solubility and dissolution testing under physiologically predictive conditions [10]. |

| Potentiometric Titrator | Automated system for precise addition of acid/base and measurement of solution pH. | High-throughput and accurate determination of pKa values. |

| Laser Diffraction Particle Sizer | Instrument for rapid, high-resolution measurement of particle size distributions. | Quality control and R&D for APIs and formulated products. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) System | Analytical instrument for separating and quantifying chemical compounds in a mixture. | Quantifying drug concentration in saturated solutions (solubility) and dissolution samples. |

| Lipid-Based Excipients (e.g., Medium-Chain Triglycerides, Labrasol) | Formulation components that enhance solubilization and supersaturation of poorly soluble drugs. | Used in lipid-based formulation strategies to improve bioavailability [10]. |

The physicochemical triumvirate of solubility, pKa, and particle size forms the bedrock of predictive IVIVC models for oral drug absorption. Solubility sets the absolute limit for the amount of drug available for absorption. The pKa governs the dynamic, pH-dependent interplay between a drug's solubility and its permeability across the intestinal membrane. Particle size is a critical engineering parameter that can be manipulated to overcome solubility-limited dissolution.

A robust IVIVC cannot be established by considering these factors in isolation. As demonstrated by the experimental data and protocols, their effects are deeply intertwined. The future of IVIVC development lies in integrated, systems-based approaches that quantitatively model these concurrent processes. This includes leveraging advanced in silico tools and multi-compartmental, biorelevant dissolution models that can simulate the complex journey of a drug—particularly a poorly water-soluble one—through the changing environment of the gastrointestinal tract. A deep, mechanistic understanding of these key physicochemical factors is, therefore, not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for the efficient development of safe and effective oral drug products.

For drug development professionals, predicting a drug's in vivo performance from in vitro data is a critical challenge. The establishment of a robust in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is a central goal, serving as a predictive mathematical model between an in vitro property and a relevant in vivo response [6]. Success hinges on a deep understanding of key biopharmaceutical properties that govern a drug's journey through the body. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three fundamental properties—permeability, partition coefficient (LogP), and absorption potential (AP)—by examining their theoretical bases, experimental protocols, and roles in predicting absorption. Mastery of these properties allows researchers to better navigate the complexities of drug development, from early candidate screening to formulating successful dosage forms.

Theoretical Foundations and Interrelationships

The absorption of an orally administered drug is a complex process contingent upon its dissolution and its ability to permeate the gastrointestinal membrane. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) provides a foundational framework that categorizes drug substances based on two of these key properties: solubility and intestinal permeability [13]. Permeability, LogP, and Absorption Potential are intrinsically linked quantitative descriptors that provide a multi-faceted prediction of a drug's absorption profile.

- Permeability: This measures the rate at which a drug molecule crosses a biological membrane, a prerequisite for systemic absorption. The transcellular permeability (Pm) of a compound is defined by the relationship:

Pm = (Kp × Dm) / Lm, where Kp is the membrane-water partition coefficient, Dm is the membrane diffusivity, and Lm is the membrane thickness [6]. High permeability is a key characteristic of BCS Class I and II drugs. - LogP (Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient): This is a measure of a drug's lipophilicity, defined as the ratio of its concentration in octanol to its concentration in water at equilibrium. It quantifies the molecule's preference for a lipid-like environment over an aqueous one. In general, a bell-shaped distribution exists between absorption and LogP, with compounds having LogP between 0 and 3 typically exhibiting high permeability [6].

- Absorption Potential (AP): This parameter represents a more integrated approach. Developed by Dressman et al., it combines lipophilicity, ionization, and dose-solubility considerations into a single metric:

AP = log[(P × Fun) / D0], where P is the partition coefficient, Fun is the fraction of unionized drug at pH 6.5, and D0 is the dose number (ratio of dose concentration to solubility) [6]. Studies indicate that AP correlates well with the fraction of drug absorbed.

The following diagram illustrates the logical and experimental relationships between these core properties and the ultimate in vivo outcome they aim to predict.

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison of these three critical properties, summarizing their definitions, optimal ranges, and their respective roles in IVIVC.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Critical Biopharmaceutical Properties

| Property | Definition & Measurement | Optimal Range for High Oral Absorption | Role in IVIVC & BCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeability | Rate of membrane crossing. Measured via experimental models (e.g., Caco-2 cells) or predicted via algorithms [14] [6]. | High permeability is required for BCS Class I and III. A good correlation exists between Caco-2 permeability and human fraction absorbed [14]. | Serves as a direct input for mechanistic absorption models. Critical for classifying drug permeability according to BCS and for justifying biowaivers [13]. |

| LogP | Logarithm of the partition coefficient of the unionized drug in an octanol-water system. A measure of lipophilicity [6]. | Generally between 0 and 3. Values outside this range (e.g., < -1.5 or > 4.5) often indicate lower membrane permeability [6]. | Used as an early screening tool for permeability prediction. Informs formulation strategies, especially for BCS Class II and IV drugs where solubility is low [13]. |

| Absorption Potential (AP) | A composite parameter: AP = log[(P * Fun) / D0]. It integrates lipophilicity, ionization, and dose-solubility [6]. |

Higher values correlate with a higher fraction of drug absorbed. The relationship is sigmoidal, allowing for quantitative absorption estimates. | Provides a more holistic pre-formulation assessment than LogP or solubility alone, helping to identify potential absorption issues early in development. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Caco-2 Cell Permeability Assay

The Caco-2 cell model is a gold standard in vitro system for predicting passive intestinal drug absorption in humans [14].

- Principle: Caco-2 cells are human colon adenocarcinoma cells that, upon differentiation, form a monolayer with tight junctions and express brush border enzymes, mimicking the intestinal epithelium. The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) is determined by measuring the rate of drug transport from the donor compartment (apical) to the receiver compartment (basolateral).

- Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Grow Caco-2 cells to confluence on porous membrane filters in transwell plates. Culture for 21 days to ensure full differentiation and polarization.

- Experiment Setup: Prepare drug solution in a suitable transport buffer (e.g., Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution, HBSS, at pH 7.4). Add the solution to the donor compartment (apical for A→B transport, basolateral for B→A transport). The receiver compartment contains blank buffer.

- Incubation: Maintain the system at 37°C with gentle agitation. Sample from the receiver compartment at predetermined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes) and replace with fresh buffer.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in the samples using a validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV, LC-MS/MS).

- Calculations: Calculate the Papp (cm/s) using the formula:

Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A * C0), where dQ/dt is the steady-state flux, A is the surface area of the membrane, and C0 is the initial donor concentration.

- Data Interpretation: A Papp value > 1 × 10⁻⁶ cm/s typically indicates high permeability and is correlated with >90% absorption in humans [14]. Drugs like naproxen, propranolol, and diltiazem exhibit high Papp, while cimetidine and chlorothiazide show low Papp, correlating with their lower human absorption [14].

Determination of LogP

- Principle: LogP is most accurately determined using the shake-flask method, where the drug is partitioned between immiscible octanol and aqueous phases (typically buffer at pH 7.4).

- Detailed Protocol:

- Partitioning: Pre-saturate n-octanol and aqueous buffer with each other. Add the drug to the system in a sealed vial and shake vigorously to reach equilibrium.

- Separation and Analysis: Centrifuge the vial to separate the two phases. Carefully sample from each phase and analyze the drug concentration in each using a suitable method (e.g., UV spectrophotometry, HPLC).

- Calculation: LogP = log10 (Concentrationinoctanol / Concentrationinwater).

Calculation of Absorption Potential (AP)

- Principle: The AP is a calculated value that integrates several experimentally determined properties [6].

- Methodology:

- Determine Input Parameters:

- P: The octanol-water partition coefficient (from 4.2).

- Fun: The fraction of unionized drug at pH 6.5. Calculated from the drug's pKa using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation.

- D0: The dose number. Calculated as

Dose (mg) / [Solubility at pH 6.5 (mg/mL) * 250 mL]. The volume of 250 mL is an estimate for small intestinal water volume [6].

- Calculation: Input the determined parameters into the equation:

AP = log[(P × Fun) / D0].

- Determine Input Parameters:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimental assessment of these properties relies on specific reagents and model systems. The following table details key solutions and materials required for the protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Permeability and Property Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A widely accepted in vitro model of the human intestinal mucosa for permeability screening [14]. | Requires rigorous cell culture practices and 21-day differentiation to form a valid barrier with functional tight junctions. |

| Transwell Plates | Permeable supports that allow for the growth of cell monolayers and separate apical and basolateral compartments for transport studies. | Pore size (e.g., 0.4 μm, 3.0 μm) and membrane material (e.g., polycarbonate, polyester) must be selected based on the experimental goal. |

| HBSS (Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution) | A standard physiological buffer used as the transport medium in permeability assays. It provides essential ions and nutrients to maintain cell viability during the experiment. | Often requires pH adjustment (e.g., to 6.5 and 7.4) with HEPES or MES buffer to simulate different gastrointestinal regions. |

| n-Octanol & Aqueous Buffers | The two-phase solvent system used in the shake-flask method for the experimental determination of the LogP. | Critical to pre-saturate both phases with each other to prevent volume shifts and achieve a stable equilibrium. |

Permeability, LogP, and Absorption Potential are not isolated metrics but interconnected pillars in the predictive science of biopharmaceutics. While LogP offers a simple estimate of lipophilicity, and permeability provides a direct measure of membrane transit, the Absorption Potential synthesizes these with solubility and ionization to deliver a more robust, holistic forecast of a drug's absorbability. A thorough, comparative understanding of these properties—their theoretical basis, their experimental determination, and their integration into models like the BCS—is indispensable for modern drug development. This knowledge empowers scientists to make informed decisions, from selecting promising drug candidates to developing formulations that ensure reliable in vivo performance, thereby strengthening the vital bridge between in vitro data and clinical outcomes.

The journey of an oral drug from ingestion to systemic circulation is a complex process governed by a dynamic interplay between the drug's properties and the physiological environment of the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract. A drug's bioavailability is profoundly influenced by variable factors such as gastrointestinal pH, transit times, and prandial state (fed versus fasted conditions). Food ingestion affects the oral bioavailability of more than 40% of drugs approved since 2010, creating significant challenges for predicting in vivo performance from in vitro data [15]. For drugs with a low therapeutic index, this fast-fed variability can lead to acute toxicities or therapeutic failure, endangering patient lives [16]. This guide objectively compares the capabilities of contemporary experimental models in incorporating these critical physiological realities, providing a framework for selecting appropriate tools in drug development research.

Physiological Factors Governing Oral Drug Absorption

Gastrointestinal pH and Fed-State Dynamics

The pH environment within the GI tract exhibits significant variability both between individuals and between fasted and fed states, particularly impacting drugs with pH-dependent solubility.

- Fasted State Gastric pH: Typically ranges between pH 1 and 2.5 [6] [15].

- Fed State Gastric pH: Can increase to pH 4-5 after a meal due to the buffering capacity of food, gradually returning to fasted state levels over several hours [16] [15].

- Intestinal pH: In the fasted state, duodenal pH ranges from approximately 5.0 to 6.5, while in the fed state, it initially decreases due to acidic chyme from the stomach before returning to near fasted-state levels through pancreatic bicarbonate secretion [16].

These pH shifts alter the ionization state of weakly acidic and basic drugs according to the pH-partition hypothesis, thereby influencing their absorption flux [16]. For instance, weakly acidic drugs become more ionized in the higher pH of the fed state, which can affect their membrane permeability.

Gastrointestinal Transit Times

GI transit time is a critical determinant for drugs with limited dissolution rates or site-specific absorption.

Table 1: Gastrointestinal Transit Parameters in Fasted and Fed States

| GI Segment | Length (m) | Surface Area (m²) | Fasted State Transit Time | Fed State Transit Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | 0.2 | 0.2 | <30 minutes (liquids) [16] | Up to 120 minutes or more [16] |

| Small Intestine | 7.3 | ~200 | 3-4 hours [16] [17] | Similar to fasted state [17] |

| Colon | 1.5 | 3 | 15-48 hours [16] | Not significantly influenced by food [17] |

In the fasted state, gastric emptying is regulated by the Migrating Myoelectric Complex (MMC), a cyclical pattern of electromechanical activity that clears indigestible solids from the stomach every 1.5-2 hours [16] [17]. Food ingestion disrupts the MMC, replacing it with digestive motility patterns that delay gastric emptying, particularly for solid dosage forms [17]. The caloric content of food directly influences this delay, with higher caloric meals prolonging gastric residence time [17].

Food Effects on Drug Solubility and Permeability

Food-induced physiological changes create complex effects on drug absorption:

- Bile Secretion: Fed state promotes bile secretion, leading to micelle formation that can solubilize lipophilic drugs (positive food effect) but potentially trap drugs and reduce free fraction available for absorption [18].

- Luminal Fluid Volume: Increased fluid volume in fed state can enhance dissolution, particularly for poorly soluble drugs [15].

- Splanchnic Blood Flow: Postprandial increase in blood flow may enhance the absorption of high-permeability drugs [15].

- Transporter/Enzyme Interactions: Food components (e.g., grapefruit juice) can inhibit intestinal CYP3A4 metabolism and drug transporters like P-glycoprotein, increasing bioavailability of susceptible drugs [15].

Diagram 1: Food Effect on Drug Absorption Pathways

Comparison of Experimental Models for Absorption Prediction

Different model systems offer varying capabilities for incorporating physiological factors in drug absorption prediction.

Table 2: Capability Comparison of Absorption Prediction Models

| Model System | GI pH Control | Transit Time Simulation | Fed/Fast State Modeling | Throughput | Human Relevance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Dissolution with IVIVC [6] [1] | Moderate (using biorelevant media) | Limited (time points only) | Moderate (different media) | High | Moderate | Does not capture permeability or metabolism |

| Caco-2 Monolayers [19] | Limited | None | Limited | Medium | Moderate (altered expression of transporters/enzymes) | Limited expression of human transporters and metabolic enzymes |

| SPIP (Rat) [20] | Good (controlled perfusate) | Partial (flow rate control) | Good (dosing with/without food) | Low | Good (correlates with human Peff) | Surgical model, species differences |

| Gut-on-a-Chip (MPS) [19] | Good | Good (fluid flow control) | Good (media switching) | Low-medium | High (human cells, physiological shear stress) | Technically complex, low throughput |

| PBPK Modeling [21] [18] | Excellent (parameterizable) | Excellent (computational) | Excellent (integrated parameters) | Very High (once established) | Excellent (human data integration) | Requires extensive validation |

In Vitro - In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) Approaches

IVIVC establishes predictive mathematical relationships between in vitro dissolution and in vivo absorption, with regulatory applications for biowaivers [6] [1].

- Level A IVIVC: Point-to-point correlation representing the highest level of correlation, most preferred by regulatory agencies for supporting biowaivers [1].

- Level B IVIVC: Uses statistical moments (mean dissolution time vs. mean residence time), less useful for predicting in vivo profiles [1].

- Level C IVIVC: Correlates single dissolution time point with pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., Cmax, AUC), useful in early development but insufficient for biowaivers [1].

The predictive power of IVIVC is enhanced using biorelevant media (FaSSGF, FaSSIF, FeSSIF) that simulate fasted and fed state gastrointestinal conditions, including pH, buffer capacity, and bile salt composition [18].

Advanced Microphysiological Systems (Gut-on-a-Chip)

The novel gut MPS/Fluid3D-X system represents a significant advancement in predicting human drug absorption by incorporating key physiological features [19].

Diagram 2: Gut MPS Experimental Workflow

This system utilizes human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived small intestinal epithelial cells (hiSIECs) that form polarized epithelial structures with functional drug transporters (P-gp, BCRP) and metabolic enzymes (CYP3A4) [19]. The Fluid3D-X device features a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) construction that prevents drug adsorption issues encountered with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chips [19]. Validation studies demonstrated accurate prediction of intestinal metabolic extraction (e.g., Fg=0.64 for midazolam vs. clinical value of 0.55) [19].

In Situ Perfusion Models (SPIP)

The Single-Pass Intestinal Perfusion (SPIP) model is an FDA-recognized method for studying regional intestinal permeability [20].

- Experimental Setup: Anesthetized rats undergo surgical isolation of intestinal segments with cannulation for controlled perfusion while maintaining blood and lymph supply [20].

- Key Parameters: Calculates effective permeability (Peff) and fraction absorbed (Fa), with demonstrated correlation to human permeability values [20].

- Fed/Fast State Modeling: Can be modified by including food components in perfusate or pre-treating animals with food [20].

The SPIP model provides direct measurement of drug permeability while avoiding the complicating factors of hepatic first-pass metabolism, enabling isolation of intestinal absorption processes [20].

Experimental Protocols for Physiological Absorption Studies

Biorelevant Dissolution Testing Under Fed and Fasted Conditions

Purpose: To simulate the in vivo dissolution of solid oral dosage forms under physiologically relevant GI conditions [6] [18].

Protocol:

- Prepare biorelevant media: FaSSGF (fasted state simulated gastric fluid) and FaSSIF-V2 (fasted state simulated intestinal fluid) for fasted conditions; FeSSIF-V2 (fed state simulated intestinal fluid) for fed conditions [18].

- For immediate-release products: Begin dissolution in FaSSGF (pH 1.2-1.6) for 30-60 minutes, then transfer to FaSSIF-V2 (pH 6.5) [18].

- Use USP Apparatus II (paddles) at 50 rpm with media volumes of 300 mL for gastric phase and 500 mL for intestinal phase [18].

- Maintain temperature at 37°C ± 0.5°C throughout the experiment.

- Sample at predetermined time points (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes), filter immediately, and analyze drug concentration.

- Perform tests in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

Data Analysis: Compare dissolution profiles between fed and fasted media and correlate with clinical food effect data when available [18].

Protocol for Assessing Enterohepatic Circulation with Fed-State Considerations

Purpose: To predict pharmacokinetics of drugs undergoing enterohepatic circulation with consideration of fed-state physiology [18].

Protocol:

- Select model drugs with known EHC (e.g., meloxicam, ezetimibe) with different solubility characteristics [18].

- Determine solubility ratio in FeSSIF-V2/FaSSIF-V2 to assess drug entrapment in bile micelles.

- Develop PBPK model incorporating gallbladder compartment with meal-triggered emptying.

- For reabsorption process, adjust permeability rate constant based on free fraction ratio (accounting for drug sequestration in bile micelles).

- Validate model by comparing predicted and observed plasma concentration-time profiles using Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [18].

Key Consideration: For drugs solubilized by bile micelles (e.g., ezetimibe), compensating the permeation rate constant based on free fraction ratio significantly improves prediction accuracy [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for GI Absorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Physiological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FaSSIF/FeSSIF Media [18] | Simulates intestinal fluid composition in fasted and fed states | Dissolution testing, solubility measurements | Contains physiological bile salts and phospholipids at relevant concentrations |

| hiSIECs [19] | Human intestinal epithelial cells from induced pluripotent stem cells | Gut-on-a-chip models, permeability studies | Maintains drug transporter and metabolic enzyme expression similar to human intestine |

| PET Microfluidic Devices [19] | Platform for gut MPS with minimal compound adsorption | Advanced in vitro absorption models | Enables fluid flow mimicking peristalsis; prevents compound loss |

| PBPK Software Platforms (e.g., PK-Sim, Simcyp) [21] | Integrates physiological parameters to predict absorption | IVIVC, food effect prediction, formulation optimization | Incorporates population variability and system-specific parameters |

| Permeability Marker Compounds [20] | Reference standards for permeability classification | SPIP studies, Caco-2 validation | Enables BCS-based permeability classification (e.g., metoprolol-high, atenolol-low) |

The accurate prediction of oral drug absorption requires careful consideration of the dynamic physiological environment of the human gastrointestinal tract. While traditional models like IVIVC and SPIP provide valuable frameworks for understanding drug absorption, emerging technologies like gut-on-a-chip systems offer more comprehensive integration of critical factors such as GI pH, transit times, and fed/fast state variability. The selection of an appropriate model system should be guided by the specific research question, stage of development, and resources available. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration with PBPK modeling and artificial intelligence promises to further enhance our ability to predict human oral bioavailability with greater precision, ultimately streamlining drug development and ensuring more predictable clinical outcomes.

Building Predictive Models: From In Vitro Tools to In Vivo Projections

Selecting Biorelevant Dissolution Apparatus and Media

The establishment of a robust in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) is a critical goal in modern drug development, serving as a predictive mathematical model that describes the relationship between an in vitro property of a dosage form and a relevant in vivo response [2] [1]. For orally administered drugs, biorelevant dissolution testing represents a fundamental component of this correlation, as it aims to simulate in vivo dissolution conditions within the gastrointestinal tract [22]. Unlike traditional dissolution methods that may employ simple aqueous buffers, biorelevant dissolution utilizes media that closely mimic the composition, surface tension, and solubilizing properties of human gastric and intestinal fluids under both fasted and fed states [22] [23]. The primary objective of selecting appropriate apparatus and media is to generate in vitro data that can reliably predict in vivo performance, thereby streamlining formulation development, reducing development costs, and potentially supporting regulatory submissions for biowaivers [1].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) provides a framework for understanding the challenges associated with different drug substances, particularly BCS Class II (low solubility, high permeability) and Class IV (low solubility, low permeability) compounds [2]. For these challenging molecules, conventional dissolution methods often fail to establish meaningful IVIVCs because they do not adequately replicate the complex physiological environment of the human GI tract, including dynamic pH changes, the presence of bile components, phospholipids, and digestive enzymes [2] [23]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of available biorelevant dissolution apparatus and media, supported by experimental data, to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate tools for predicting in vivo performance.

Comparison of Dissolution Apparatus

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) standardizes several dissolution apparatuses that are commonly used in biorelevant testing. USP Apparatus II (paddle apparatus) is the most widely implemented system for conventional and biorelevant dissolution studies due to its simplicity and well-characterized hydrodynamics [22] [24]. The apparatus consists of a cylindrical vessel containing the dissolution medium maintained at 37°C, with a paddle that rotates at a controlled speed to provide gentle agitation. This system is particularly valuable for evaluating immediate-release solid oral dosage forms under biorelevant conditions [22].

USP Apparatus III (reciprocating cylinder) offers an alternative hydrodynamic environment that more closely simulates the mechanical stresses and changing physiological conditions experienced by a dosage form as it transits through the gastrointestinal tract [25]. This apparatus features a set of glass tubes containing the dosage form that move vertically within vessels filled with dissolution media. The agitation rate is controlled by the number of dips per minute (dpm), with studies demonstrating that approximately 5 dpm produces hydrodynamic conditions equivalent to USP Apparatus II at 50 rpm [25]. A comparative study evaluating USP Apparatus II and III for immediate-release products of both highly soluble drugs (metoprolol and ranitidine) and poorly soluble drugs (acyclovir and furosemide) found that with appropriate agitation rates, Apparatus III can produce similar dissolution profiles to Apparatus II while offering the advantage of mimicking the changing physiochemical conditions of the GI tract [25].

Apparatus Selection Guide

The selection of an appropriate dissolution apparatus depends on the specific drug properties, formulation characteristics, and the objectives of the dissolution study. The following table provides a comparative overview of the two primary apparatuses used in biorelevant dissolution testing:

Table 1: Comparison of Key Dissolution Apparatus for Biorelevant Testing

| Apparatus Type | Key Features | Hydrodynamic Characteristics | Optimal Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP Apparatus II (Paddle) | Simple design, well-established method [22] [24] | Laminar flow dependent on paddle rotation speed (typically 50-75 rpm) [22] | Immediate-release formulations, quality control testing, comparative dissolution studies [22] | Potential for cone formation, limited ability to simulate GI tract physiology [25] |

| USP Apparatus III (Reciprocating Cylinder) | Ability to transfer between different media, simulates GI transit [25] | Vertical agitation controlled by dips per minute (5-25 dpm) [25] | Extended-release formulations, dosage forms requiring pH changes, simulating fasted/fed state transitions [25] | More complex operation, potential for incomplete dissolution observed with some poorly soluble drugs [25] |

For specialized applications, particularly with lipid-based formulations, additional in vitro tools such as lipolysis assays may be necessary to account for the complex interplay of digestion, permeation, and dynamic solubilization that occurs in vivo [2]. These systems incorporate digestive enzymes and bile components to better simulate the intestinal environment where lipid digestion significantly influences drug release and absorption.

Comparison of Biorelevant Media

Composition and Physiological Relevance

Biorelevant media are specifically designed to simulate the composition and physicochemical properties of human gastrointestinal fluids under both fasted and fed states. These media contain bile salts, phospholipids, and other components that create a solubilizing environment similar to that encountered by a drug product in vivo [22]. The following table summarizes the key biorelevant media and their compositions:

Table 2: Comparison of Key Biorelevant Dissolution Media

| Medium | Prandial State | Simulated GI Fluid | pH | Key Components | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FaSSGF | Fasted [22] | Gastric [22] | 1.6 [22] | 3F Powder + FaSSGF Buffer [22] | Simulates gastric dissolution in fasted state [22] |

| FaSSIF | Fasted [22] | Small Intestinal [22] | 6.5 [22] | 3F Powder + FaSSIF Buffer [22] | Standard fasted state intestinal dissolution [22] |

| FeSSIF | Fed [22] | Small Intestinal [22] | 5.0 [22] | 3F Powder + FeSSIF Buffer [22] | Standard fed state intestinal dissolution [22] |

| FaSSIF-V2 | Fasted [22] | Small Intestinal [22] | 6.5 [22] | FaSSIF-V2 Powder + FaSSIF-V2 Buffer [22] | Updated fasted state formula [22] |

| FeSSIF-V2 | Fed [22] | Small Intestinal [22] | 5.8 [22] | FeSSIF-V2 Powder + FeSSIF-V2 Buffer [22] | Updated fed state formula [22] |

The critical difference between biorelevant and traditional media lies in their solubilizing capacity. Traditional phosphate buffers lack the mixed micelles present in intestinal fluids, which can lead to misleading results, particularly for poorly soluble drugs that may exhibit supersaturation in vivo [23]. As demonstrated in the gefitinib case study, traditional phosphate buffer resulted in rapid drug precipitation, while biorelevant media (FaSSIF) maintained the drug in a supersaturated state, more accurately reflecting the in vivo behavior [23].

Media Selection Strategy

The selection of appropriate biorelevant media should be guided by the anticipated in vivo conditions and the properties of the drug substance. For compounds with pH-dependent solubility, a sequential testing approach that simulates GI transit (e.g., starting with FaSSGF followed by transfer to FaSSIF or FeSSIF) may be necessary to fully capture the dissolution and precipitation behavior [23]. For drugs administered with food, fed-state media (FeSSIF, FeSSIF-V2) are essential to evaluate potential food effects on dissolution and absorption [22].

The updated versions of biorelevant media (FaSSIF-V2 and FeSSIF-V2) offer improved physiological relevance compared to their predecessors, with revised buffer capacities and osmolarity that better match human intestinal fluids [22]. When possible, these updated media should be prioritized for IVIVC development, particularly during later stages of formulation development where predictive accuracy is critical.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Biorelevant Dissolution Protocol

A comprehensive biorelevant dissolution experiment follows a systematic approach to ensure generated data is reproducible and biologically relevant:

Apparatus Setup: Use USP Apparatus II (paddle) or Apparatus III according to study objectives. For USP Apparatus II, set vessel volume to 500-1000 mL and maintain temperature at 37±0.5°C [22] [23].

Medium Preparation: Prepare fresh biorelevant media using standardized powders and buffers according to manufacturer specifications. For fed-state simulations, ensure appropriate reconstitution and equilibration [22].

Dosage Form Introduction: Place the dosage form in the vessel containing the appropriate medium. For two-stage experiments, begin with gastric medium (FaSSGF) [23].

Sampling Schedule: Withdraw samples at predetermined time points (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 minutes) using syringes equipped with glass microfibre filters (13mm, 0.45μm) [22]. Use a fresh filter at each time point to prevent adsorption artifacts and halt the dissolution process effectively.

Sample Analysis: Analyze drug concentration in samples using validated HPLC methods with UV (DAD or PDA) detection. Employ preliminary filter adsorption studies to confirm that sampling methodology does not artificially influence results [22].

Data Processing: Calculate cumulative drug release and plot dissolution profiles for comparison between test and reference formulations.

Two-Stage Dissolution Protocol for GI Transit Simulation

For compounds whose solubility varies with pH, a two-stage dissolution experiment better simulates the transition from stomach to intestinal environment:

Gastric Phase: Conduct dissolution in FaSSGF (pH 1.6) for 60 minutes using USP Apparatus II at 50 rpm [23].

Intestinal Phase Transition: Without removing the dosage form, carefully add a concentrated buffer solution (e.g., FaSSIF Converter Buffer Concentrate) to adjust pH to intestinal conditions (pH 6.5) while maintaining sink conditions [23].

Intestinal Phase Monitoring: Continue dissolution for an additional 120 minutes, sampling at appropriate intervals to monitor for potential precipitation or supersaturation behavior [23].

Data Analysis: Compare the resulting dissolution profile with that obtained using traditional phosphate buffer to identify differences in precipitation behavior that might significantly impact in vivo performance prediction [23].

Case Study: Gefitinib Two-Stage Dissolution

Experimental Design and Results

A compelling case study demonstrating the critical importance of media selection involves the tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (250 mg dose) [23]. This study directly compared two-stage dissolution using biorelevant media (FaSSGF → FaSSIF) versus traditional phosphate buffer in a physiologically-structured experiment.

The results revealed dramatic differences in dissolution behavior between the two media systems. Gefitinib completely dissolved during the first hour in FaSSGF (pH 1.6) under both conditions. However, upon transition to the intestinal phase, stark contrasts emerged:

Table 3: Gefitinib Dissolution Behavior in Different Media

| Medium System | Gastric Phase (60 min) | Intestinal Phase (120 min) | Supersaturation Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biorelevant Media | Complete dissolution in FaSSGF [23] | No significant precipitation; drug remained in metastable supersaturated state [23] | Maintained throughout intestinal phase [23] |

| Traditional Phosphate Buffer | Complete dissolution in FaSSGF [23] | Rapid drug precipitation observed [23] | No supersaturation maintained [23] |

Implications for IVIVC

The gefitinib case study highlights several critical considerations for IVIVC development:

Predictive Accuracy: Traditional phosphate buffer provided a potentially misleading prediction of in vivo behavior by failing to maintain supersaturation, which could have led to underestimation of bioavailability [23].

Physiological Relevance: The biorelevant media, containing mixed micelles of bile salts and phospholipids, more accurately simulated the in vivo intestinal environment where supersaturation is often maintained through interaction with physiological surfactants [23].

Formulation Decision-Making: Reliance on traditional media might have prompted unnecessary formulation optimization for gefitinib, whereas biorelevant testing correctly indicated that the drug would likely remain bioavailable despite the pH shift in the intestine [23].

This case study substantiates the value of biorelevant media in predicting supersaturation and precipitation behaviors—critical phenomena for BCS Class II compounds that significantly influence in vivo absorption [2] [23].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing biorelevant dissolution requires specific reagents and materials to ensure physiological relevance and experimental consistency. The following table catalogues essential solutions and their functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biorelevant Dissolution

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 3F Powder | Base powder for preparing FaSSGF, FaSSIF, and FeSSIF media [22] | Standard biorelevant medium preparation for fasted and fed states [22] |

| FaSSIF-V2 Powder | Base powder for updated FaSSIF-V2 medium [22] | Improved fasted state simulation with updated buffer capacity and osmolarity [22] |

| FeSSIF-V2 Powder | Base powder for updated FeSSIF-V2 medium [22] | Improved fed state simulation [22] |

| Various Buffer Concentrates (FaSSGF Buffer, FaSSIF Buffer, FeSSIF Buffer, etc.) | Provide appropriate pH and ionic strength for specific GI regions [22] | Media reconstitution for regional GI simulation [22] |

| Glass Microfibre Filters (0.45μm) | Sample filtration to separate undissolved drug while minimizing adsorption [22] | Sampling at predetermined time points during dissolution experiments [22] |

| FaSSIF Converter Buffer Concentrate | pH adjustment from gastric to intestinal conditions in two-stage experiments [23] | Transition from FaSSGF to FaSSIF during GI transit simulation [23] |

Decision Framework for Apparatus and Media Selection

The following workflow diagrams provide visual guidance for selecting appropriate dissolution apparatus and media based on research objectives and drug substance properties:

Diagram 1: Apparatus and Media Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: IVIVC Level and Media Requirement Relationship