Cold Atmospheric Plasma for Food Bioactive Compounds: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Potential

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an emerging non-thermal technology gaining traction for its ability to safely enhance and preserve bioactive compounds in foods.

Cold Atmospheric Plasma for Food Bioactive Compounds: Mechanisms, Applications, and Clinical Potential

Abstract

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an emerging non-thermal technology gaining traction for its ability to safely enhance and preserve bioactive compounds in foods. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental mechanisms by which CAP's reactive species interact with food matrices. It details practical methodologies and applications for optimizing the extraction and stability of pigments, phenolics, and vitamins, while also addressing critical challenges in process standardization. A comparative evaluation validates CAP's efficacy against conventional techniques, highlighting its significant potential not only for creating functional foods but also for contributing to nutraceutical development and clinical research by improving the bioavailability of health-promoting bioactives.

Understanding Cold Plasma: Mechanisms of Action on Food Bioactives

Defining Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) and Its Key Reactive Species

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is a partially or fully ionized gas considered the fourth state of matter, generated at or near ambient temperature and pressure conditions [1] [2]. It is composed of a complex mixture of reactive particles, including electrons, positive and negative ions, free radicals, excited atoms and molecules, and electromagnetic radiation [1] [3]. Unlike thermal plasma, CAP is characterized by its non-equilibrium state, where electrons exist at a much higher temperature (10⁶–10⁸ K) than ions and neutral particles, which remain close to room temperature [2]. This unique property makes it suitable for application on heat-sensitive materials, including biological tissues and food products [1].

The technology has gained significant attention as a novel, non-thermal, and eco-friendly method for enhancing food processing, reducing nutrient loss and degradation compared to traditional thermal methods [4]. Its operational simplicity, low energy consumption, high reactivity, and absence of toxic chemical residues align with sustainable development goals and the increasing consumer demand for minimally processed, high-quality foods [5] [6].

Fundamental Principles and Generation of CAP

Plasma Generation Mechanisms

CAP is produced by supplying sufficient energy (electrical, radiant, or thermal) to a neutral gas, causing its molecules to undergo ionization through collisions [1]. This process strips electrons from atoms, creating a soup of charged particles that is overall electrically neutral [3]. The resulting plasma is a highly reactive medium containing various active species.

Common CAP Generation Systems

Several reactor configurations are employed for generating CAP, each with distinct characteristics and suitability for different applications:

Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD): This prevalent method uses two metal electrodes, at least one covered with a dielectric layer (e.g., ceramic, glass, quartz) [6]. It operates at atmospheric pressure with alternating current or pulsed voltages (typically 1–500 kHz), creating discrete filamentary or uniform glow discharges [6]. DBD is valued for its uniform discharge, operational safety, and cost-effectiveness [6].

Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ): This configuration generates plasma beyond its discharge gap, ejecting a plume of ionized gas through a nozzle into an unconfined working zone [6]. It typically uses coaxial or ring-shaped electrodes with inert or mixed gases, allowing for remote treatment of complex, three-dimensional surfaces [6].

Corona Discharge (CD): CD generates non-thermal plasma through localized electron avalanches in a strongly non-uniform electric field between asymmetric electrodes (e.g., a sharp needle and a larger plate) [6]. It is often used in electrostatic precipitation and ozone generation, though it can face challenges with spatial uniformity [6].

Other Systems: Additional methods include Gliding Arc Discharge (GAD), which elongates arcs by gas-dynamic shear forces [6], and systems driven by radio frequency (RF) or microwave (MW) energy [1] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Cold Atmospheric Plasma Generation Systems

| System Type | Key Characteristics | Common Gases Used | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) | Electrodes with dielectric barrier; filamentary/glow discharge | Air, N₂, O₂, Ar, He, mixtures | Surface treatment, food decontamination, enzyme inactivation | Uniform discharge, operational safety, cost-effective | Limited penetration depth |

| Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ) | Plasma plume generated beyond electrodes; remote treatment | Ar, He, often with admixtures (O₂, N₂) | Biomedical applications, sterilization of irregular surfaces | Remote treatment, good spatial control, high reactivity | Can require noble gases |

| Corona Discharge (CD) | Non-uniform field; sharp electrode vs. large counter-electrode | Ambient air, O₂ | Ozone generation, electrostatic precipitation | Simple design, low cost | Small treatment area, risk of localized damage |

| Gliding Arc Discharge (GAD) | Elongated arcs driven by gas flow; cyclic ignition/extinction | Air, N₂, O₂ | Wastewater treatment, chemical reforming | High ionization rates, handles flowing media | Can transition to thermal plasma |

Key Reactive Species in CAP: Identity and Formation

The biocidal and functional-modifying actions of CAP are primarily attributed to the synergistic effects of its diverse reactive species, which can be categorized as follows:

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS are oxygen-containing, highly reactive molecules and free radicals. Key examples generated in CAP include:

- Ozone (O₃) [6]

- Atomic Oxygen (O) [1]

- Superoxide (O₂⁻) [1]

- Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) [1]

- Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [1]

- Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) [1]

Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS)

RNS are nitrogen-containing reactive molecules crucial for biological interactions. Prominent examples include:

Other Plasma Components

- Charged Particles: Electrons, positive ions (e.g., Ar⁺, N₂⁺, O₂⁺), and negative ions [1] [3].

- Photons: Ultraviolet (UV) and vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) radiation emitted during the relaxation of excited species [6] [3].

- Electric Fields: The electromagnetic field present in the plasma region [1] [2].

These species are not pre-existing but are generated in situ through collisions of electrons with the background gas molecules (e.g., O₂, N₂, H₂O) when energy is supplied to the system.

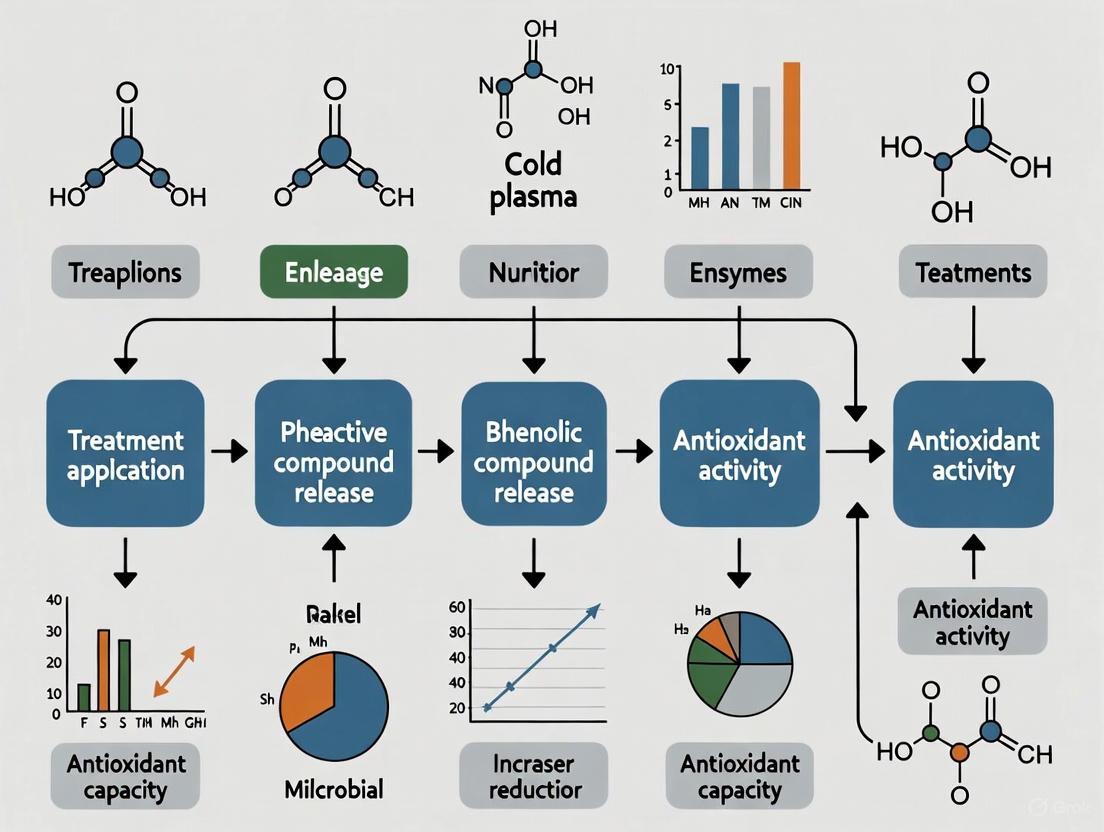

Diagram 1: Reactive species generation in CAP.

Mechanisms of Action: Interaction with Biological Systems

The reactive species in CAP act synergistically through multiple mechanisms to inactivate microorganisms and modify biological structures:

Microbial Inactivation

CAP is highly effective against a broad spectrum of pathogens, including bacteria (Gram-positive and Gram-negative), viruses, and fungi [3]. The microbial inactivation is a multi-target process:

- Cell Membrane Damage: ROS and RNS cause oxidative stress, leading to lipid peroxidation, disruption of membrane integrity, and eventual cell lysis [5] [3]. Studies show direct plasma exposure induces severe membrane damage and disintegration after 300 seconds [3].

- Intracellular Damage: Reactive species penetrate the compromised cell wall, damaging vital internal biomolecules. This includes protein oxidation and denaturation, and DNA strand breaks induced by UV radiation and oxidative stress [5] [3].

- Electrostatic Disruption: Charged particles and the electric field can also contribute to the rupture of microbial cells [2].

Interaction with Food Bioactives

The effect of CAP on food constituents is dualistic and depends on treatment parameters:

- Enhancement of Bioactive Compounds: CAP can increase the extractability and stability of phenolic compounds, anthocyanins, and vitamins by activating enzymes like phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and breaking down cell walls to release bound compounds [4] [7]. For instance, treatments have been shown to increase total phenolic content in mango, green tea, and strawberry [4].

- Degradation Risks: Excessive treatment (high power/long duration) can lead to the degradation of sensitive compounds like phenolics, pigments, and vitamins due to intense oxidative reactions that break aliphatic chains and benzene rings [4].

Enzyme Inactivation

CAP effectively inactivates enzymes responsible for food quality deterioration, such as polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD), which cause enzymatic browning. Reductions in activity of up to 70% have been achieved under specific CAP conditions [4] [5]. This is primarily due to the oxidation of amino acid residues in the enzyme's active site and changes in the protein's secondary and tertiary structure [4].

Experimental Protocols for Food Bioactives Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Microbial Inactivation on Food Surfaces

This protocol outlines a method to evaluate the efficacy of CAP in reducing microbial load on solid food samples, such as fruits and vegetables.

Principle: Direct exposure of contaminated food surfaces to CAP causes microbial inactivation via oxidative damage from ROS/RNS, UV radiation, and electrostatic effects [3].

Materials:

- CAP source (e.g., DBD or plasma jet system)

- High-voltage power supply and gas flow controller

- Sterile scalpels, forceps, and stomacher bags

- Nutrient agar plates and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Analytical balance and incubator

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut food material (e.g., apple, lettuce) into uniform discs (e.g., 2 cm diameter).

- Inoculation: Spot-inoculate food surfaces with a standardized microbial suspension (e.g., 10⁵–10⁶ CFU/mL of E. coli or Listeria monocytogenes). Air-dry in a laminar flow hood for 30-60 minutes.

- CAP Treatment: Place inoculated samples in the plasma discharge zone. Treat samples at varying power (e.g., 100-200 W), exposure times (e.g., 30-300 s), and gas compositions (e.g., air, Ar/O₂ mix) according to experimental design [3]. Maintain a fixed electrode-to-sample distance.

- Microbial Enumeration: Post-treatment, transfer each sample into a stomacher bag with 10 mL of PBS and homogenize. Perform serial dilutions and spread-plate onto nutrient agar. Incubate plates at 37°C for 24-48 hours.

- Analysis: Count viable colonies and calculate log reduction compared to untreated controls. Express inactivation efficacy as Log₁₀(N₀/N), where N₀ and N are the counts before and after treatment.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

This protocol is used to investigate how CAP treatment affects the concentration and bioactivity of phenolic compounds in plant-based foods.

Principle: CAP can disrupt plant cell walls, enhancing the release of bound phenolic compounds, while optimal parameters can preserve or increase their content and associated antioxidant capacity [4] [7].

Materials:

- CAP source (DBD preferred for uniform surface treatment)

- Refrigerated centrifuge and spectrophotometer

- Solvents: Methanol, ethanol, acetone

- Analytical reagents: Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, gallic acid, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), Trolox standard, sodium carbonate

Procedure:

- Treatment: Apply CAP to whole or sliced plant material (e.g., grape pomace, strawberry puree). Use a central composite design or RSM to vary key parameters: voltage (e.g., 20-80 kV), time (e.g., 1-10 min), and gas type (e.g., Air, Ar) [7].

- Extraction: Homogenize treated and control samples with a suitable solvent (e.g., 80% methanol) at a defined ratio (e.g., 1:10 w/v). Centrifuge at 8000×g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Collect the supernatant.

- Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Analysis:

- Use the Folin-Ciocalteu method [7].

- Mix supernatant aliquot with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and sodium carbonate solution.

- Incubate in the dark for 2 hours, then measure absorbance at 765 nm.

- Quantify TPC against a gallic acid standard curve (mg GAE/g sample).

- Antioxidant Activity (DPPH Assay):

- Mix sample extract with methanolic DPPH solution.

- Incubate for 30 minutes in the dark.

- Measure absorbance decrease at 517 nm.

- Express results as Trolox Equivalents (μmol TE/g sample) [7].

- Data Modeling: Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) or Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to model the relationship between CAP parameters and the responses (TPC, DPPH), identifying optimal treatment conditions [7].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CAP Food Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Reactor | Core device for generating uniform cold plasma at atmospheric pressure. | Widely used for surface decontamination and modification of flat food samples. |

| Plasma Jet (APPJ) System | Generates a remote plasma plume for treating irregular 3D surfaces. | Ideal for spot treatment or complex geometries; often uses noble gases. |

| Noble Gases (Ar, He) | Common feed gases for plasma generation; provide a stable, controllable discharge. | Argon is frequently used; often mixed with small amounts of reactive gases (O₂). |

| Reactive Gas Admixtures (O₂, N₂) | Introduced to modulate the cocktail of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS). | Critical for studying the specific roles of ROS vs. RNS in biological effects. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Chemical assay for quantifying total phenolic content (TPC) in extracted samples. | Essential for evaluating CAP's impact on food bioactives. |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable free radical used to assess the free radical scavenging (antioxidant) activity of extracts. | Standard method for determining antioxidant capacity post-CAP treatment. |

| Nutrient Agar & Broth | Microbiological growth media for cultivating and enumerating microorganisms. | Used in viability assays to determine microbial log reduction after CAP treatment. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic buffer for sample dilution, washing, and suspension of biological material. | Used for preparing microbial inocula and homogenizing food samples post-treatment. |

Applications in Food Bioactives Research

CAP technology offers diverse applications that align with the goals of modern food science, particularly in enhancing the value and safety of plant-based foods.

- Enhancing Extractability of Bioactives: CAP pretreatment acts as a green physical method to disrupt plant cell walls, facilitating the release of bound bioactive compounds. This has been successfully applied to improve the recovery of phenolics from grape pomace, stevia glycosides from Stevia reubadiana, and essential oils from various herbs [4] [1].

- Enzyme Inactivation for Quality Preservation: By inactivating browning enzymes like polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD), CAP helps maintain the color, sensory attributes, and shelf-life of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables [4] [2]. Treatment conditions must be optimized to achieve enzyme inactivation without damaging the food matrix.

- Microbial Decontamination for Safety and Shelf-life: CAP is a powerful tool for surface decontamination, achieving significant log reductions (>5-log) in pathogens like E. coli and Listeria on produce, meat, and dairy [5] [3]. The in-package cold plasma technology, where food is sealed and then treated, is particularly promising for maintaining sterility and extending shelf life up to 14 days in products like chicken and fresh-cut melon [5].

- Modification of Macromolecules: CAP induces functional changes in food polymers. It can improve the solubility, emulsification, and foaming capacity of plant proteins (e.g., soy, pea) by altering their structure [5] [8]. It also modifies starch granules, enhancing water absorption and reducing cooking time, as demonstrated in rice [5] [8].

Diagram 2: Primary applications of CAP in food processing.

Application Notes: Mechanisms of Action and Quantitative Effects

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an emerging non-thermal technology for food processing, capable of modifying food matrices and enhancing the extractability and activity of bioactive compounds. Its effects are primarily mediated by Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS), UV photons, and electric fields [9]. The following table summarizes the core interaction mechanisms and their documented effects on food components.

Table 1: Core Interaction Mechanisms of Cold Atmospheric Plasma with Food Matrices

| Plasma Agent | Primary Mechanisms of Action | Observed Effects on Food Matrices & Bioactives | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS) | - Induces oxidative stress, damaging microbial cell walls and intracellular components [9].- Triggers mild oxidation and cleavage of phenolic compounds in plant tissues [10].- Generates secondary reactive species in solution (e.g., peroxynitrite) [9]. | - Microbial inactivation and destruction of biofilms [9].- Increased extractability of phenolic and flavonoid compounds from plant matrices [10].- Modulation of antioxidant activity, often leading to an increase [10]. | - Buckwheat Flour/Grain: TPC increased to 83.99/80.47 mg GAE/g DW; TFC to 96.60/91.53 mg RE/g DW; DPPH scavenging activity reached 92.25/89.69% after optimal CAP treatment [10]. |

| UV Radiation | - Causes direct damage to microbial DNA and proteins [9].- Contributes to the breakdown of organic polymeric layers and biofilms [9]. | - Synergistic effect with RONS for microbial deactivation.- Can facilitate the release of bound phytochemicals. | - Often works synergistically; quantitative contribution is system-dependent and less frequently isolated in studies. |

| Electric Fields | - Causes electroporation (permeabilization) of microbial and plant cell membranes [9].- Facilitates the entry of reactive species into cells [9]. | - Enhances mass transfer, improving the diffusion of solvents into cells and bioactives out of cells during extraction.- Accelerates microbial inactivation. | - The electrostatic field permeates cell walls, leading to the breakage of chemical bonds and membrane openings [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Assessing the Impact of CAP on Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity in Grains

This protocol is adapted from a study on buckwheat, providing a template for evaluating CAP treatment on whole grains and flours [10].

Aim: To determine the effect of cold atmospheric plasma treatment time and voltage on the Total Phenolic Content (TPC), Total Flavonoid Content (TFC), and Antioxidant Activity (AOA) of food matrices.

Equipment and Reagents:

- CAP Device: Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma reactor [10].

- Samples: Whole grain and corresponding flour.

- Key Reagents: Methanol (80%), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, Sodium carbonate, Gallic acid, Sodium nitrite, Aluminum chloride, Rutin, DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl), FRAP reagent [10].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Clean whole grains and mill into flour, sieving to a uniform particle size (e.g., through No. 40 & 50 mesh sieves) [10].

- CAP Treatment:

- Place 10 g of sample in a glass Petri dish.

- Set the plasma reactor parameters: constant frequency (e.g., 37.2 kHz), variable voltage (e.g., 50 kV, 60 kV), and variable treatment time (e.g., 5 min, 10 min) [10].

- Use air as the discharge gas at a fixed flow rate (e.g., 10 mL/min) [10].

- Include untreated control samples.

- Extraction:

- Homogenize 1 g of treated/control sample with 20 mL of 80% methanol.

- Centrifuge the mixture at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes and collect the supernatant.

- Repeat extraction steps and combine supernatants to a final volume [10].

- Analysis:

- Total Phenolic Content (TPC): Use the Folin-Ciocalteu method. Measure absorbance at 765 nm and express results as mg Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) per g Dry Weight (DW) [10].

- Total Flavonoid Content (TFC): Use the aluminum chloride method. Measure absorbance at 510 nm and express results as mg Rutin Equivalents (RE) per g DW [10].

- Antioxidant Activity (AOA):

- DPPH Assay: Mix extract with DPPH solution, incubate in the dark, and measure absorbance at 517 nm. Calculate radical scavenging activity as a percentage [10].

- FRAP Assay: Mix extract with FRAP working reagent, incubate, and measure absorbance at 593 nm. Express results as mmol Fe²⁺ equivalent per mg DW [10].

Protocol for Generating and Utilizing Plasma-Activated Water (PAW)

Aim: To produce and characterize Plasma-Activated Water (PAW) for liquid-based food treatment or surface sanitation.

Equipment and Reagents:

- CAP Device: Any suitable system for treating liquids (e.g., DBD over water surface, plasma jet submerged in water) [9].

- Ultrapure Water

- pH meter

- Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP) meter

Methodology:

- PAW Generation: Expose a volume of ultrapure water to cold plasma for a defined duration. Key parameters include plasma power, gas composition (air, oxygen, nitrogen), and treatment time [9].

- PAW Characterization:

- Measure the immediate change in pH (expected to decrease due to acid formation) and ORP (expected to increase due to RONS) [9].

- Application: Use the freshly generated PAW for treating food samples (e.g., by immersion, spraying) or as a disinfectant wash. The efficacy is attributed to the reactive mixture of ROS (e.g., OH, O₂⁻, O₃, H₂O₂) and RNS (e.g., NO₂⁻, NO₃⁻, ONOO⁻) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for CAP Research on Food Bioactives

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Colorimetric assay for quantifying total phenolics. | Reacts with phenolic compounds in the TPC assay; results expressed in Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) [10]. |

| DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable free radical used to assess antioxidant scavenging capacity. | The decrease in absorbance at 517 nm after reaction with an extract measures its free radical scavenging activity [10]. |

| FRAP Reagent | (Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma) measures antioxidant power via reduction of Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺. | Used to determine the reducing power of a sample, with results expressed as mmol Fe²⁺ equivalents [10]. |

| Aluminum Chloride (AlCl₃) | Complexes with flavonoids to form a colored adduct. | Essential for the colorimetric quantification of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) [10]. |

| Rutin and Gallic Acid | High-purity standard compounds for calibration curves. | Rutin is used as a standard for TFC; Gallic Acid is used as a standard for TPC [10]. |

| HPLC-grade Solvents (Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Mobile phase for chromatographic separation and identification. | Used in HPLC analysis to identify and quantify specific phenolic compounds (e.g., rutin, quercetin) [10]. |

Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an emerging non-thermal technology rapidly transforming food bioactive research. CAP generates a unique mix of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), ultraviolet photons, and charged particles [11] [6]. When applied to biological materials, these reactive species induce controlled modifications to cellular structures, a process that can be strategically harnessed to enhance the release and bioavailability of bioactive compounds embedded within plant and microbial cells [12] [13]. This application note details the mechanisms, quantitative effects, and standardized protocols for using CAP to manipulate cellular architectures for improved bioactive accessibility, providing a critical resource for researchers and scientists in food and pharmaceutical development.

The core principle involves using CAP's RONS to selectively degrade or permeabilize structural barriers—such as plant cell walls and microbial membranes—that typically impede the extraction and release of valuable compounds like polyphenols, vitamins, and lipids [5] [13]. This physical disruption facilitates a more efficient release of intracellular content, thereby increasing the concentration of bioactives in the surrounding matrix and potentially improving their absorption efficacy [12] [11].

Mechanisms of Cellular Disruption

Cold Plasma's effect on cellular structures is primarily mediated by the oxidative action of RONS on key biochemical components. The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms through which CAP disrupts cellular and macromolecular structures to enhance compound release.

Membrane and Cell Wall Interactions

The initial interaction occurs at the cellular boundary. In microbial cells, RONS such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), atomic oxygen (O), and ozone (O₃) trigger lipid peroxidation in the phospholipid bilayer, compromising membrane integrity and leading to increased permeability, leakage of cellular contents, and eventual cell death [14] [13]. Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria exhibit different susceptibility patterns due to variations in cell wall structure [13].

For plant tissues, the primary target is the rigid cell wall composed of polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin. CAP-generated RONS facilitate the oxidative cleavage of these polymers, weakening the structural matrix and creating micropores [5] [6]. This degradation reduces the physical barrier to diffusion, allowing intracellular bioactives such as polyphenols, antioxidants, and oils to leach out more readily during subsequent extraction or digestion. This mechanism is crucial for enhancing the yield of valuable compounds from plant-based food materials [12] [6].

Quantitative Effects on Bioactive Release

The efficacy of CAP treatment is highly dependent on process parameters, including treatment time, power input, gas composition, and the specific food matrix. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on bioactive compound release and microbial inactivation.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Cold Plasma Treatment on Bioactive Compound Release and Microbial Load

| Food Matrix | CAP Treatment Parameters | Key Quantitative Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banana-Carrot Smoothie + Sumac | Gliding arc plasma, 10 min | - 4.17 log CFU/mL reduction in microbial counts- 63% increase in total polyphenols after storage- 46% higher Vitamin C retention after 24 h | [12] |

| Plant-Based Proteins | Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) | - Up to 12.7% improvement in protein solubility- Enhanced emulsification and foaming capacity | [11] [5] |

| Cereals & Starch | Atmospheric Pressure Plasma | - Cross-linking of starch granules improves water absorption- 27.5% reduction in rice cooking time | [5] |

| Fresh Produce Surfaces | DBD, 60 sec | - >5-log reduction in E. coli, Listeria, and Salmonella- Up to 70% reduction in peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase activity | [5] [13] |

| Shrimp (Shewanella putrefaciens) | DBD-ACP, Cyclic Treatment | - Significant bactericidal effect via ROS/RNS synergy- DNA damage and irreversible electroporation leading to cell death | [15] |

The data demonstrates that CAP can simultaneously enhance microbiological safety and the bioactive profile of food matrices. The 10-minute plasma treatment on the sumac-enriched smoothie not only ensured microbial safety but also significantly improved the release and retention of polyphenols and vitamin C, indicating a dual benefit of preservation and nutritional enhancement [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Treatment of Liquid Food Matrices (e.g., Smoothies, Juices)

This protocol is adapted from studies on smoothies and juices to assess the impact of CAP on bioactive release and microbial stability [12].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare the liquid matrix (e.g., banana-carrot smoothie). For enriched formulations, add functional ingredients like sumac powder (e.g., 2 g/100 mL) [12].

- Divide the sample into aliquots (e.g., 25-50 mL) in sterile, shallow containers to maximize plasma exposure surface area.

2. Plasma Treatment:

- Equipment Setup: Use a gliding arc discharge (GAD) or Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) reactor at atmospheric pressure [12] [6].

- Gas & Power: Use dry air or a specified gas mixture (e.g., Nitrogen). Set the RMS voltage and power (e.g., 680 V, 40 VA for GAD) [12] [16].

- Application: Place the sample container at a fixed distance (e.g., 1-5 cm) from the plasma source. Treat samples for varying durations (e.g., 1 min and 10 min) to establish a dose-response relationship [12].

3. Post-Treatment Analysis:

- Microbiological Analysis: Determine total aerobic mesophilic bacteria, yeast, and mold counts immediately after treatment and at intervals during storage (e.g., using plate count methods) [12] [16].

- Bioactive Compound Quantification:

- Colloidal Stability: Monitor particle size distribution and zeta potential to evaluate plasma-induced changes to the product's physical structure [12].

Protocol for Solid Food Surfaces (e.g., Seeds, Meat, Shrimp)

This protocol is designed for the decontamination and surface modification of solid foods, derived from applications on shrimp, seeds, and meat [13] [15].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Use uniform pieces or grains (e.g., shrimp, wheat grains). For bread studies, cut into cubes (e.g., 15x15x15 mm) to standardize treatment [16].

- Artificially contaminate surfaces with target microorganisms if evaluating decontamination efficacy.

2. Plasma Treatment:

- Equipment Setup: A DBD system or an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ) is often suitable for surface treatment [15] [6].

- Configuration: For DBD, place the sample directly on the grounded electrode, which may be covered with a dielectric barrier. Ensure the sample surface is parallel to the electrode.

- Parameters: Apply a high voltage (e.g., 6.9 kV to 80 kV depending on the device) for a set duration (e.g., 30 seconds to 10 minutes). Gas composition (e.g., ambient air, 70% O₂ + 30% CO₂) should be controlled and documented [15] [16].

3. Post-Treatment Analysis:

- Microbial Inactivation: Enumerate surviving microorganisms by stomaching or swabbing the treated surface and performing serial dilution and plating.

- Lipid Oxidation: Assess in protein-rich matrices like shrimp and meat using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay [15].

- Color and Texture Analysis: Use a colorimeter to measure L, a, b* values and a texture analyzer for hardness/firmness to evaluate any quality changes.

- Enzymatic Activity: Assess the activity of spoilage-related enzymes (e.g., polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase) using standard spectrophotometric assays [13].

The following workflow graph outlines the key stages of a standard CAP experimental procedure for evaluating bioactive release.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of CAP experiments requires specific reagents and equipment for treatment and subsequent analysis. The following table lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for CAP Bioavailability Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma Generation | ||

| DBD or GAD Reactor | Core device for generating cold plasma at atmospheric pressure. | Can be laboratory-built; DBD offers uniform discharge, GAD is effective for liquids and surfaces [12] [6]. |

| High-Voltage Power Supply | Energizes the plasma reactor. | Typical frequencies: kHz to MHz range; voltages from kV to tens of kV [6]. |

| Gas Supply & Controller | Provides and controls the working gas for plasma generation. | Gases: Air, Nitrogen, Argon, Helium, or mixtures. Purity (e.g., 6.0 for N₂) is often critical [16]. |

| Analytical Reagents | ||

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Quantification of total polyphenolic content in extracted supernatants. | Reacts with phenolic hydroxyl groups; results expressed as GAE [12]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Agar | Microbiological analysis for assessing decontamination efficacy. | e.g., Plate Count Agar for total viable counts; specific media for pathogens [12] [16]. |

| Griess Reagent / Probes | Detection and quantification of RONS, particularly nitrite (NO₂⁻) in Plasma-Activated Liquids (PAL). | Used in UV-Vis or fluorescence spectroscopy [17]. |

| Biological Models | ||

| Zebrafish Larvae (Danio rerio) | In vivo toxicological assessment of CAP-treated complex food matrices. | Model organism for holistic toxicity evaluation, including locomotor and developmental effects [12]. |

| Human Cell Lines (e.g., cancer lines) | In vitro assessment of cytotoxicity and bioactivity of CAP-treated extracts. | Used in plasma oncology and to study cellular uptake of released compounds [14] [17]. |

Cold Atmospheric Plasma technology presents a powerful, non-thermal tool for precisely manipulating cellular structures to enhance the bioavailability of bioactive compounds in food and biological matrices. The synergistic effect of RONS induces controlled oxidative stress on cellular walls and membranes, facilitating the release of intracellular content while simultaneously ensuring microbiological safety. The provided protocols and data frameworks offer researchers a foundation for standardizing experiments and optimizing parameters for specific applications. Future research should focus on the long-term safety of plasma-treated foods, scaling up laboratory systems for industrial application, and a deeper mechanistic understanding of how CAP-induced structural changes directly influence the absorption and metabolism of released bioactives in humans.

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an emerging non-thermal technology rapidly gaining traction in food and bioactive research. It consists of a partially ionized gas generated at or near room temperature, containing a complex mixture of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), electrons, ions, and ultraviolet photons [6] [8]. Its unique mode of action, which avoids thermal degradation, positions it as a promising alternative to conventional thermal processing for manipulating and preserving heat-sensitive bioactive compounds in food and plant matrices. This application note details the fundamental effects of CAP on three major bioactive classes—phenolics, pigments, and vitamins—and provides standardized protocols for researchers investigating these interactions.

Quantitative Effects on Major Bioactive Classes

The impact of CAP is dual-faceted, capable of either enhancing or degrading bioactives, heavily dependent on treatment parameters and the food matrix. The table below summarizes the documented effects on key bioactive compounds.

Table 1: Documented Effects of Cold Plasma on Major Bioactive Compounds

| Bioactive Class | Specific Compound/Matrix | Reported Effect | Key Treatment Parameters | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolics | Total Phenolics/ Buckwheat Grain & Flour | Increase: Up to 84.0 mg GAE/g DW (from 50 kV, 10 min) [10] | DBD, 50-60 kV, 5-10 min [10] | Cell wall disruption, improved extractability, possible stress-induced biosynthesis [18] [19] |

| Total Flavonoids/ Buckwheat | Increase: Up to 96.6 mg RE/g DW [10] | DBD, 50-60 kV, 5-10 min [10] | Same as above; release of bound forms [7] | |

| Rutin/ Buckwheat | Increase: Up to 3.6 mg/kg [10] | DBD, 50 kV, 10 min [10] | Enhanced release from the matrix [10] | |

| Phenolics/ Tomato Pomace | Increase: ~10% higher extraction yield [19] | HVACP, He/N₂ gas [19] | Surface etching, increased hydrophilicity, cell rupture [19] | |

| Pigments | Chlorophylls | Variable: Degradation reported [20] | Various DBD, Jet Plasma [20] | Oxidative degradation by RONS; cell rupture can increase initial extractability [20] [21] |

| Carotenoids | Variable: Generally good preservation; some degradation [20] [21] | Various DBD, Jet Plasma [22] | Less sensitive than chlorophylls; oxidation and isomerization possible [20] | |

| Anthocyanins | Variable: Degradation or preservation reported [20] | Various DBD, Jet Plasma [22] [20] | Susceptible to oxidation; degradation increases with treatment time [20] | |

| Betalains | Variable: Degradation or preservation reported [20] | Various DBD, Jet Plasma [22] [20] | High sensitivity to RONS; prone to oxidative degradation [20] | |

| Vitamins | Vitamin C | Decrease: Reported in some juices [10] [23] | Various [22] | High susceptibility to oxidation by ROS and UV photons [22] [23] |

| B Vitamins (B1, B2) | Generally Stable: Minimal losses reported [10] | Various [10] | Higher stability compared to vitamin C [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Enhancing Phenolic Bioaccessibility in Plant Matrices

This protocol is adapted from studies on buckwheat and tomato pomace, demonstrating how CAP can increase the extractability and content of phenolic compounds [10] [19].

Application Objective: To enhance the total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant activity (AOA) of whole grains or flours via CAP pretreatment.

Materials & Reagents:

- Plant Material: Whole buckwheat grains or similar (e.g., wheat, barley).

- CAP Reactor: Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) system at atmospheric pressure.

- Power Supply: High-voltage AC power (0-100 kV range, frequency 37-50 kHz).

- Gases: Food-grade air, nitrogen (N₂), argon (Ar), or helium (He).

- Extraction Solvents: Methanol (70-80%), Ethanol (aqueous solutions).

- Analytical Reagents: Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, Gallic acid, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), Sodium carbonate.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mill grains to a uniform particle size (e.g., pass through #40 & #50 mesh sieves). For whole grains, clean and dry to a uniform moisture content.

- CAP Treatment:

- Place a 2 mm thick layer of sample (≈10 g) in a glass Petri dish.

- Position the dish between the two electrodes of the DBD reactor.

- Set the operating parameters. A recommended starting point is:

- Voltage: 50 - 60 kV

- Treatment Time: 5 - 10 minutes

- Gas: Air or Nitrogen

- Flow Rate: 10 mL/min

- Frequency: 37.2 kHz

- Initiate plasma discharge for the set duration. For uniformity, stir the sample midway using a vortex mixer.

- Post-treatment Extraction:

- Homogenize 1 g of treated sample with 20 mL of 80% methanol for 2 min.

- Stir the mixture for 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Centrifuge at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Collect the supernatant. Repeat the extraction process 2-3 times on the residue and pool the supernatants.

- Adjust the final volume to 25 mL with methanol and store at -20°C until analysis.

- Analysis:

Key Optimization Notes: The effects are highly parameter-dependent. Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) or Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to optimize voltage, time, and gas composition for your specific matrix [18] [7].

Protocol for Assessing Pigment Stability

This protocol outlines a method for evaluating the impact of CAP on natural pigments, which can exhibit variable stability [20] [21].

Application Objective: To determine the stability of chlorophylls, carotenoids, and anthocyanins in fresh produce or powders after CAP exposure.

Materials & Reagents:

- Food Matrix: Fresh leafy greens (for chlorophyll), carrot powder (for carotenoids), berry puree (for anthocyanins).

- CAP Reactor: DBD or Plasma Jet system.

- Extraction Solvents: Acetone (for chlorophyll), Hexane/Acetone mixture (for carotenoids), Acidified Methanol (e.g., 1% HCl) for anthocyanins.

- Analytical Reagents: Quartz cuvettes, spectrophotometer or HPLC system.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the matrix in a uniform form (e.g., cut leaves into 1x1 cm pieces, create a thin layer of puree).

- CAP Treatment:

- Expose samples to CAP. A suggested parameter range is:

- Voltage: 40 - 80 kV

- Treatment Time: 1 - 10 minutes (shorter times recommended for pigments)

- Gas: Argon, Helium, or air (inert gases may be less degradative).

- Include an untreated control sample.

- Expose samples to CAP. A suggested parameter range is:

- Pigment Extraction:

- Chlorophyll/Carotenoids: Homogenize sample with solvent (e.g., acetone) in the dark, centrifuge, and collect supernatant.

- Anthocyanins: Homogenize with acidified methanol, centrifuge, and collect supernatant.

- Analysis:

- Spectrophotometry: Measure absorbance at specific wavelengths (e.g., 663nm & 645nm for chlorophyll, 520nm for anthocyanins) and calculate concentration using standard equations.

- HPLC: For higher precision, use HPLC with a PDA detector to quantify individual pigment species and identify degradation products.

Key Consideration: Pigments are highly susceptible to oxidative degradation by RONS. The treatment must be carefully optimized, as the same process that ruptures cells to release pigments can also degrade them if over-applied [20].

Mechanisms and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms through which Cold Plasma interacts with plant tissue and bioactive compounds, leading to either positive or negative outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for CAP Bioactivity Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAP Systems | Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD), Plasma Jet (PJ) | Generation of reactive plasma species at near-ambient temperature. | DBD offers uniform treatment; PJ allows for remote, targeted application [6]. |

| Working Gases | Air, Nitrogen (N₂), Argon (Ar), Helium (He) | Medium for plasma generation; determines RONS profile. | Inert gases (Ar, He) are less oxidative, potentially better for pigments [20] [19]. |

| Analytical Kits & Reagents | Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent, DPPH, ABTS, FRAP reagents | Quantification of Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Activity (AOA) [10]. | Validate method for specific matrix; prepare fresh radical solutions for AOA. |

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, Ethanol, Acetone, Acidified Methanol | Extraction of specific bioactive classes from plant matrices. | Solvent polarity must match target compounds (e.g., acidified methanol for anthocyanins) [20]. |

| Reference Standards | Gallic Acid, Rutin, Quercetin, Cyanidin, β-Carotene | Calibration and quantification in HPLC/spectrophotometric analysis. | Use high-purity (>95%) standards for accurate calibration curves. |

Cold Atmospheric Plasma presents a powerful, non-thermal tool for modulating the content and accessibility of dietary bioactives. Its effects are complex and parameter-dependent, capable of significantly enhancing phenolic release while posing a risk of degradation to more sensitive pigments and vitamins. Successful application requires a meticulous, optimization-based approach tailored to the specific food matrix and target compound. The protocols and mechanisms outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers in food science, nutrition, and drug development to further explore and harness this promising technology.

CAP Systems and Protocols for Bioactive Enhancement in Food

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is a partially ionized gas operating at near-ambient temperatures, representing an advanced non-thermal technology with transformative applications across the food and biomedical sectors. CAP is generated by applying electric fields to gases, producing a unique reactive environment containing electrons, ions, free radicals, and various excited species without significant heat input [24] [25]. This non-equilibrium characteristic makes CAP particularly suitable for processing heat-sensitive materials, including food bioactives and biological tissues.

The therapeutic and processing efficacy of CAP primarily stems from its generation of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS), which include both long-lived species (nitrate, hydrogen peroxide, ozone) and short-lived species (hydroxyl radicals, superoxide) [26] [6]. These reactive components, along with secondary effects such as ultraviolet radiation and mild electromagnetic fields, enable CAP to effectively inactivate microorganisms, modify surface properties, and influence cellular processes without compromising the structural integrity or nutritional value of treated materials [24] [27].

Within food bioactives research, CAP technology offers a innovative approach to addressing critical challenges in microbial safety, enzymatic stability, and functional property enhancement. Unlike conventional thermal processing methods that often degrade heat-sensitive nutrients and bioactive compounds, CAP operates at low temperatures, thereby preserving the nutritional quality, sensory attributes, and biological activity of processed food products [6] [8]. This technical note provides a comprehensive overview of three principal CAP systems—Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD), Plasma Jet, and Microwave Discharge—detailing their operational mechanisms, standard protocols, and specific applications relevant to food bioactives research.

System Fundamentals and Technical Specifications

The design and configuration of CAP systems significantly influence the composition and concentration of generated reactive species, thereby determining their applicability and effectiveness for specific research objectives. The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of the three primary CAP systems used in food bioactives research.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Cold Atmospheric Plasma Systems

| System Parameter | Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) | Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ) | Microwave Discharge (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | High-voltage discharge between electrodes with dielectric barrier(s) [26] [6] | Plasma plume ejected beyond electrodes into open environment [24] [6] | High-frequency electromagnetic waves (GHz range) ionize gas [6] |

| Electrode Configuration | Parallel plates with one or two dielectric barriers [26] | Coaxial or ring-shaped electrodes [6] | Waveguide or applicator, no direct electrodes in contact [6] |

| Power Requirements | AC or pulsed voltages (1–500 kHz, up to 10 MHz) [6] | High-frequency, low-frequency, or nanosecond pulses (100–250 V) [6] | Microwave frequency (e.g., 2.45 GHz) [6] |

| Typical Gases Used | Air, nitrogen, oxygen, argon, helium [6] | Primarily inert gases (Ar, He) sometimes with admixtures [6] | Various, including air and specific gas mixtures [24] |

| Plasma Temperature | Near-ambient (non-thermal) [25] | Near-ambient (non-thermal) [27] | Near-ambient (non-thermal) [6] |

| Discharge Characteristics | Filamentary micro-discharges or uniform glow discharge [26] [6] | Streamer or glow discharge characteristics [6] | Often continuous, uniform discharge [6] |

| Key Advantages | Uniform discharge, operational safety, scalable design [6] | Remote treatment capability, suitable for complex surfaces [24] [6] | High electron density, efficient reactive species generation [6] |

| Research Applications | Microbial inactivation on flat surfaces, enzyme modification [26] [8] | Treatment of irregular 3D structures, medical applications [27] | Volumetric treatment, efficient pesticide degradation [6] |

Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Systems

DBD systems represent one of the most prevalent CAP configurations in food processing research due to their operational flexibility and effectiveness. These systems operate by generating plasma between two metal electrodes separated by at least one dielectric barrier (e.g., ceramic, glass, quartz, or polymer) that prevents current flow and arc formation, sustaining a stable non-thermal plasma zone in the gas-filled gap [6]. The dielectric material accumulates surface charges during each voltage half-cycle, creating a self-pulsing mechanism that quenches individual micro-discharges and maintains the non-equilibrium character of the plasma [26] [6].

DBD configurations are categorized based on their dielectric layer arrangement. Single DBD (S-DBD) systems feature one electrode covered by a dielectric, while the other remains exposed. This asymmetric configuration typically generates stronger discharge intensity, higher charge characteristics, and increased reactive species production due to more effective field emission and secondary electron emission [26]. In contrast, Double DBD (D-DBD) systems incorporate dielectric barriers on both electrodes, resulting in more uniform filamentary micro-discharges with enhanced stability, albeit with generally lower discharge intensity compared to S-DBD systems [26]. Comparative studies have demonstrated that S-DBD reactors achieve higher microbial inactivation rates (e.g., 3.52-log₁₀ reduction in Salmonella typhimurium at 80 W for 4 minutes) compared to D-DBD reactors (0.82-log₁₀ reduction for the same pathogen under identical conditions), attributed to their stronger discharge characteristics and higher electron density [26].

Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ) Systems

APPJ systems generate plasma within a confined region but project the resulting plasma plume beyond the electrode assembly into an open treatment zone, enabling remote processing of samples without direct contact with the electrodes [6]. This distinctive characteristic makes APPJ particularly valuable for treating irregular surfaces, complex geometries, and heat-sensitive materials that cannot be positioned between conventional DBD electrodes [24]. The plasma plume formation relies on precise combinations of gas flow dynamics and electric field distribution, typically utilizing inert gases like argon or helium to facilitate discharge initiation and plume stability [6].

APPJ systems offer significant advantages for three-dimensional food products and biomedical applications where targeted treatment is essential. The separation between the discharge region and the treatment zone enhances process control and minimizes potential damage to both the plasma source and the treated material [27]. Additionally, the directed flow of reactive species enables efficient delivery of RONS to specific surface areas, making APPJ suitable for selective modification of food surfaces and functionalization of bioactive compounds [6] [27].

Microwave Discharge (MW) Systems

Microwave discharge systems generate plasma through the interaction between high-frequency electromagnetic radiation (typically at 2.45 GHz) and gas molecules, creating intense ionization without direct electrode contact [6]. This electrode-less design minimizes contamination risks and electrode erosion issues encountered in other plasma systems, while the high-frequency excitation produces dense plasma with substantial concentrations of reactive species [24]. Microwave plasma sources often achieve higher electron densities compared to DBD and APPJ systems, resulting in enhanced production rates of biologically and chemically active species relevant for food bioactive modification [6].

The operational principle involves coupling microwave energy into a resonant cavity or waveguide containing the process gas, where the alternating electromagnetic field accelerates free electrons, subsequently ionizing neutral gas molecules through collisions [6]. This configuration enables efficient energy transfer and volumetric plasma generation, making microwave systems particularly effective for gas conversion applications and treatment of powdered or granular food materials where uniform exposure is challenging [6].

Experimental Protocols for Food Bioactives Research

Protocol 1: Microbial Inactivation on Food Surfaces Using DBD

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of DBD plasma for inactivating foodborne pathogens on solid food surfaces while preserving bioactive compounds.

Materials and Equipment:

- DBD plasma reactor with parallel plate electrode configuration

- High-voltage AC power supply (CTP-2000K or equivalent) [26]

- Gas supply system (compressed air, nitrogen, or specific gas mixtures)

- Target microorganisms (Salmonella typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli)

- Sterile food samples (fresh produce, meat slices, or model systems)

- Neutralizing buffer for microbial recovery

- Standard plate count equipment and materials

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Inoculate sterile food samples (e.g., 5×5 cm sections) with 100 μL of bacterial suspension (approximately 10⁷-10⁸ CFU/mL) and air-dry in a laminar flow hood for 30 minutes under controlled conditions [26].

- DBD System Setup: Configure the DBD reactor with electrode gap adjusted to 2-10 mm based on sample thickness. Set the dielectric barrier(s) according to experimental requirements (single or double dielectric configuration) [26].

- Parameter Optimization: Set plasma input power to 40-80 W, excitation frequency to 10 kHz, and select appropriate treatment gas (e.g., ambient air or modified atmosphere) [26].

- Treatment Application: Position inoculated samples between DBD electrodes and apply plasma for predetermined durations (30-300 seconds). For indirect treatment, position samples downstream from the discharge zone [24].

- Post-treatment Analysis: Transfer treated samples to sterile bags containing neutralizing buffer, homogenize for 60 seconds, and perform serial dilutions for viable plate counting [26]. Calculate log reduction values compared to untreated controls.

- Bioactive Compound Assessment: Analyze key bioactive compounds (e.g., polyphenols, vitamins, antioxidants) in treated and control samples using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC, spectrophotometric assays) to quantify preservation efficiency [6] [8].

Technical Notes: Maintain consistent humidity levels (40-60% RH) throughout experiments as moisture significantly influences plasma chemistry. For temperature-sensitive bioactives, monitor and record sample temperature during treatment using infrared thermography or embedded thermocouples [26].

Protocol 2: Surface Functionalization of Protein Matrices Using APPJ

Objective: To modify the functional properties and bioactivity of food protein surfaces using atmospheric pressure plasma jet treatment.

Materials and Equipment:

- APPJ system with coaxial electrode configuration

- Inert gas supply (argon or helium with optional oxygen admixtures)

- Protein samples (isolates, concentrates, or model protein films)

- Analytical equipment for protein characterization (FTIR, spectrophotometer)

- Contact angle goniometer for wettability measurements

- Solubility and emulsification assessment apparatus

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare uniform protein films or layers on glass slides using solvent casting method, or use standardized protein powder compressed into tablets for consistent surface characteristics [6].

- APPJ Configuration: Set plasma jet to operating parameters: voltage 100-250 V, gas flow rate 1-10 standard liters per minute (slm), and treatment distance 5-30 mm from sample surface [6].

- Treatment Optimization: Conduct preliminary tests to determine optimal exposure time (30-180 seconds) and gas composition for specific protein modifications.

- Plasma Treatment: Apply APPJ treatment to protein samples using predetermined parameters, ensuring consistent plume coverage across the surface through controlled movement or expanded jet diameter [6].

- Functional Property Assessment:

- Structural Analysis: Employ FTIR spectroscopy to examine secondary structure changes, particularly in amide I and II regions, and assess surface chemistry modifications through XPS if available [6].

Technical Notes: Protein modifications are highly dependent on plasma parameters and sample characteristics. Preliminary experiments should establish dose-response relationships for specific protein systems. Immediate analysis post-treatment is recommended as some plasma-induced modifications may be transient [6] [8].

Protocol 3: Enhancement of Bioactive Extraction Efficiency Using Microwave Plasma

Objective: To utilize microwave-driven cold plasma as a pretreatment to enhance the extraction efficiency of bioactive compounds from plant matrices.

Materials and Equipment:

- Microwave plasma system with appropriate applicator

- Plant material (herbs, seeds, or agricultural by-products)

- Extraction equipment (soxhlet, ultrasound-assisted, or pressurized liquid extraction)

- Analytical instruments (HPLC, GC-MS, spectrophotometer)

- Milling and sieving equipment for sample preparation

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mill plant materials to consistent particle size (0.5-2.0 mm), and determine initial moisture content. For comparative studies, divide homogeneous samples into treatment and control groups [6].

- Microwave Plasma Pretreatment: Place samples in the microwave plasma treatment chamber, ensuring uniform exposure. Apply plasma using optimized parameters: microwave power 500-1500 W, treatment time 60-300 seconds, and appropriate gas atmosphere (air, nitrogen, or argon-oxygen mixtures) [6].

- Extraction Process: Subject plasma-pretreated and control samples to identical extraction procedures (solvent, temperature, time, and solid-to-liquid ratio).

- Extract Analysis: Quantify target bioactive compounds (phenolics, flavonoids, essential oils, or specific phytochemicals) in extracts using validated analytical methods [6] [8].

- Yield Comparison: Calculate extraction yield enhancement by comparing bioactive compound concentrations from plasma-pretreated samples versus controls.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate the quality of extracted bioactives by assessing antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP, ORAC assays), compound stability, and potential formation of degradation products [8].

Technical Notes: The enhancement mechanism may involve cellular structure disruption, increased surface permeability, or chemical modification of cell wall components. Microscopic analysis (SEM) of plant tissues before and after plasma treatment can provide insights into structural changes responsible for improved extraction efficiency [6].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CAP Food Bioactives Research

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Gases | High-purity (>99.5%) argon, helium, nitrogen, oxygen, or synthetic air [6] | Plasma medium determining RONS profile | Argon for APPJ; air for DBD; specialized mixtures for targeted chemistry [26] [6] |

| Biological Indicators | Certified microbial strains (E. coli, L. monocytogenes, S. typhimurium) [26] [24] | Validation of antimicrobial efficacy | Inoculation studies on relevant food matrices [26] [24] |

| Chemical Trapping Agents | Analytical grade scavengers (e.g., L-histidine, mannitol, TEMP) [26] | Identification of specific reactive species | Mechanism studies to determine primary inactivation pathways [26] |

| Bioactive Standards | Certified reference materials (phenolic compounds, vitamins, antioxidants) [8] | Quantification of preservation efficacy | HPLC/spectrophotometric analysis of bioactive retention [6] [8] |

| Dielectric Materials | High-quality ceramics, quartz, or alumina plates [26] [6] | Barrier formation in DBD systems | Custom DBD reactor construction and optimization [26] |

| Analytical Kits | Commercial antioxidant capacity assays (ORAC, FRAP, DPPH) [8] | Assessment of oxidative stress on bioactives | Evaluation of plasma-induced oxidation in sensitive compounds [8] |

Visualization of CAP Mechanisms and Workflows

CAP Microbial Inactivation Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for CAP Bioactives Research

The strategic application of DBD, plasma jet, and microwave discharge systems offers researchers powerful tools for investigating plasma-mediated effects on food bioactives. Each system presents distinct advantages: DBD provides uniform treatment of planar surfaces, APPJ enables targeted application on complex geometries, and microwave discharge ensures high-efficiency reactive species generation. The protocols outlined herein establish standardized methodologies for evaluating microbial safety, functional properties, and extraction efficiency while preserving bioactive compound integrity.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular interactions between plasma-generated species and specific bioactive compounds, developing intelligent process control systems based on real-time monitoring of plasma chemistry, and establishing predictive models for process optimization across diverse food matrices. As CAP technology continues to evolve, its integration with complementary non-thermal processing methods and alignment with sustainable development goals will further enhance its value for advancing food bioactives research and development.

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an advanced non-thermal technology gaining significant traction in food bioactives research. Its efficacy stems from generating Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS) which interact with biological materials. The biological outcomes of CAP treatment—including microbial inactivation, enzyme modification, and enhancement of bioactive compound extractability—are critically dependent on three fundamental parameters: voltage, gas composition, and exposure time. This protocol provides a structured framework for researchers to systematically optimize these parameters to achieve specific experimental objectives in food science applications.

The Core Parameters of Cold Plasma Treatments

The effects of Cold Plasma are governed by the synergistic interaction of its operational parameters. Optimizing these settings is essential for targeting specific food components while preserving product quality.

Voltage/Power Input determines the energy supplied to ionize the gas, directly influencing the density and type of reactive species generated. Higher voltages typically increase the concentration of RONS, enhancing treatment intensity [8] [24].

Gas Composition is the primary factor determining the chemical nature of the plasma plume. Different gases yield distinct RONS profiles: oxygen-rich plasmas promote the formation of ozone and atomic oxygen, while nitrogen-based plasmas favor the generation of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite, each with unique biological interactions [24] [6].

Exposure Time controls the duration of interaction between the plasma-generated reactive species and the target material. Longer exposure times increase the cumulative dose of RONS, allowing for deeper penetration or more extensive modification of the substrate [8].

Table 1: Core Cold Plasma Treatment Parameters and Their Functional Roles

| Parameter | Functional Role | Impact on Plasma Treatment | Common Ranges in Food Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage/Power | Determines ionization energy and reactive species density [8] [24]. | Higher voltage increases RONS generation, enhancing microbial inactivation and modification effects. | 2–90 kV; 30–549 W [24] [6]. |

| Gas Composition | Defines the chemical identity of reactive species (ROS vs. RNS) [24] [6]. | Oxygen-rich gases enhance oxidative effects; noble gases like Ar/He allow deeper penetration. | Air, O₂, N₂, Ar, He, and custom mixtures [6]. |

| Exposure Time | Controls the cumulative dose of reactive species delivered to the sample [8]. | Longer exposure increases treatment intensity and effect magnitude but risks quality degradation. | 60 seconds to 720 seconds [8] [24]. |

The following tables consolidate quantitative findings from recent research, illustrating the effects of varying key parameters across different food applications.

Table 2: Optimizing Parameters for Microbial Inactivation in Various Foods

| Food Product | Target Microorganism | Device & Key Parameters | Reduction (log CFU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Delicious Apples [24] | Salmonella, E. coli | Device: DBDVoltage: 200 WTime: 240 s | 5.3–5.5 /cm² |

| Boiled Chicken Breast [24] | Salmonella, E. coli, L. monocytogenes | Device: DBDVoltage: 39 kVTime: 210 s | 3.5–3.9 /cube |

| Prepackaged Mixed Salad [24] | Salmonella | Device: DBDVoltage: 35 kVTime: 180 s | 0.8 /g |

| Tender Coconut Water [24] | L. monocytogenes, E. coli | Device: DBDGas: Modified Air (M65)Voltage: 90 kVTime: 120 s | 2.0–2.2 /mL |

Table 3: Optimizing Parameters for Functional Food Property Modification

| Target Application | Food Matrix | Device & Key Parameters | Observed Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Inactivation [8] [5] | Fruits & Vegetables | Device: Atmospheric DBDVoltage: 6.9 kVTime: < 60 s | Up to 70% reduction in Polyphenol Oxidase & Peroxidase activity |

| Starch Modification [8] [5] | Rice | Device: Cold PlasmaTreatment: Optimized | 27.5% reduction in cooking time; improved gelatinization |

| Protein Functionalization [8] [5] | Soy & Pea Protein Isolates | Device: Cold PlasmaTreatment: Optimized | Solubility increased by up to 12.7%; improved emulsification/foaming |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Microbial Inactivation on Fresh Produce Surface

Objective: To achieve a >5-log reduction of E. coli and Salmonella on the surface of fresh produce using Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma.

Materials:

- Plasma Device: Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) system with parallel plate electrodes [24] [6].

- Gas Supply: Compressed dry air or specified gas mixture (e.g., 65% O₂, 30% CO₂, 5% N₂) [24].

- Sample Prep: Fresh produce (e.g., apples, lettuce), artificially inoculated with target pathogens.

- Culture Media: Tryptic Soy Agar for bacterial enumeration.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Inoculate produce surfaces with a standardized suspension (e.g., 10⁶ CFU/mL) of the target pathogen. Air-dry in a biosafety cabinet for 1 hour.

- Plasma Setup: Place samples between two DBD electrodes. Set electrode gap to 10–35 mm [24].

- Parameter Setting:

- Post-treatment Analysis: Serially dilute treated samples in peptone water, plate on TSA, and incubate at 37°C for 24–48 hours before counting colonies. Compare with untreated controls.

Protocol 2: Enhancement of Plant-Based Protein Functionality

Objective: To improve the solubility and emulsifying capacity of plant-based protein isolates (e.g., from soy or pea) via cold plasma treatment.

Materials:

- Plasma Device: Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ) or DBD [11] [6].

- Protein Sample: Commercial soy or pea protein isolate powder.

- Gas Supply: Helium or argon gas, optionally with reactive gas admixtures (e.g., oxygen).

- Analytical Equipment: Spectrophotometer, pH meter, centrifuge.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve or suspend protein isolate in buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) to a defined concentration (e.g., 1% w/v).

- Plasma Setup: For liquid treatment, use an APPJ configuration where the plasma plume is directed onto the surface of the protein solution [6].

- Parameter Setting:

- Gas Composition: Pure helium or argon with 0.1–1% oxygen admixture.

- Power Input: 50–200 W.

- Treatment Time: 60–300 seconds, with continuous stirring of the solution.

- Post-treatment Analysis:

- Protein Solubility: Measure by Bradford assay or nitrogen solubility index.

- Emulsifying Activity: Use the turbidometric method of Pearce and Kinsella.

- Structural Analysis: Employ techniques like SDS-PAGE or fluorescence spectroscopy to assess conformational changes.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram visualizes the logical workflow for optimizing cold plasma treatment parameters, from initial objective setting to final validation.

The mechanistic pathway below illustrates how optimized cold plasma parameters lead to specific outcomes in food bioactives research through the action of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species (RONS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Cold Plasma Food Bioactives Research

| Tool Category | Specific Item/Technique | Function & Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Core Plasma Systems [24] [6] [28] | Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) | Function: Generates uniform plasma for surface treatment and in-package decontamination.Note: Ideal for treating flat or regularly shaped solid foods. |

| Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet (APPJ) | Function: Produces a focused plasma plume for targeted treatment.Note: Suitable for liquid treatment or localized surface decontamination. | |

| Process Gases [24] [6] | Noble Gases (Argon, Helium) | Function: Facilitates stable plasma generation at lower voltages.Note: Often used as carrier gases; can be mixed with reactive gases (O₂, N₂). |

| Reactive Gases (Oxygen, Nitrogen, Air) | Function: Determines the primary reactive species (ROS or RNS) profile.Note: Dry, compressed air is a cost-effective option for microbial inactivation. | |

| Analytical & Validation Tools [8] [24] | Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES) | Function: Identifies and quantifies reactive species in the plasma plume. |

| Microbial Culture & Enumeration | Function: Quantifies log reduction of pathogens (e.g., E. coli, L. monocytogenes). | |

| Protein & Starch Functionality Assays | Function: Measures solubility, emulsification, gelatinization, and structural changes. |

Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) has emerged as a groundbreaking non-thermal technology for enhancing food safety and preserving nutritional quality in the food processing industry. This application note details specific case studies and protocols for implementing CAP in fruit, vegetable, and grain processing, framed within broader research on its effects on food bioactives. CAP technology utilizes ionized gas containing reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), electrons, and ultraviolet photons to inactivate pathogens and modify food matrices while preserving heat-sensitive bioactive compounds [3] [13]. The non-thermal nature of CAP (operating at temperatures below 40°C) makes it particularly suitable for treating heat-sensitive food products without compromising their nutritional or organoleptic properties [3].

The efficacy of CAP treatments depends on multiple parameters including power intensity, exposure time, gas composition, and food matrix characteristics. Research demonstrates that CAP can simultaneously address microbial safety concerns while enhancing the bioavailability of beneficial phytochemicals in plant-based foods [13] [10]. This dual functionality positions CAP as a valuable technology for producing minimally processed foods with extended shelf life and enhanced functional properties, meeting growing consumer demand for fresh, high-quality food products.

Key Application Case Studies

Microbial Inactivation on Produce Surfaces

Multiple studies have confirmed the efficacy of CAP for reducing microbial loads on fresh produce. Research examining two Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644) and three Gram-negative bacteria (Salmonella typhimurium CCM 5445, Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 13076, Escherichia coli O157:H7), plus yeast (Candida albicans ATCC 10231), demonstrated significant inactivation through direct CAP treatment [3]. The study identified that direct plasma application was more effective than indirect methods involving distilled water, with microbial inhibition increasing proportionally with both power intensity (100-200 W) and exposure time (30-300 seconds) [3].

Table 1: Microbial Inactivation Efficacy of CAP Treatment on Foodborne Pathogens

| Microorganism | Type | Optimal Power | Optimal Exposure Time | Reduction Efficacy | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Gram-positive | 200 W | 300 s | >5 log reduction | Intracellular disruption, moderate envelope damage [13] |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Gram-positive | 200 W | 300 s | >5 log reduction | Cell membrane disruption, enzyme inactivation [3] |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Gram-negative | 200 W | 300 s | >5 log reduction | Low-level DNA mutation, cell leakage [13] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Gram-negative | 200 W | 300 s | >5 log reduction | Membrane lipid oxidation, protein denaturation [3] |

| Candida albicans | Yeast | 200 W | 300 s | >4 log reduction | Cell wall erosion, membrane disintegration [3] |

Morphological analysis revealed that CAP treatment induces substantial damage to microbial cell membranes, with longer exposure times (300 seconds) causing complete cell lysis and membrane disintegration [3]. The reactive species generated during plasma formation, particularly reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), oxidize lipids and sugars in microbial cell membranes, leading to cell death [3]. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria exhibited different inactivation patterns, with Gram-positive bacteria showing primarily intracellular disruption and Gram-negative bacteria experiencing DNA damage and cell leakage [13].

Enhancement of Bioactive Compounds in Buckwheat

A comprehensive study investigated the effects of CAP treatment on the phenolic and flavonoid content of whole buckwheat grain and flour, revealing significant enhancement of antioxidant compounds [10]. Using a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma reactor at varying voltages (50 and 60 kV) and exposure times (5 and 10 minutes), researchers observed substantial increases in total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and antioxidant activity (AOA) compared to untreated controls.

Table 2: Effect of CAP Treatment on Bioactive Compounds in Buckwheat

| Sample Type | Treatment Conditions | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g DW) | Total Flavonoid Content (mg RE/g DW) | DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity (%) | FRAP (mmol Fe²⁺/mg DW) | Rutin Content (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckwheat Flour | Control | 58.42 ± 0.05 | 65.31 ± 0.04 | 75.18 ± 0.05 | 35.12 ± 0.03 | 1.8 ± 0.03 |

| Buckwheat Flour | 50 kV, 10 min (S2) | 83.99 ± 0.07 | 96.60 ± 0.03 | 92.25 ± 0.03 | 48.09 ± 0.05 | 3.6 ± 0.06 |

| Buckwheat Grain | Control | 55.63 ± 0.04 | 62.15 ± 0.06 | 72.45 ± 0.04 | 32.85 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.02 |

| Buckwheat Grain | 60 kV, 5 min (S3) | 80.47 ± 0.03 | 91.53 ± 0.07 | 89.69 ± 0.04 | 42.88 ± 0.03 | 2.7 ± 0.02 |

The study demonstrated that optimal CAP treatment conditions can significantly increase the concentration of beneficial phytochemicals in buckwheat products. The sample treated at 50 kV for 10 minutes (S2) showed the highest values for TPC, TFC, AOA, and rutin content among flour samples, while grain treated at 60 kV for 5 minutes (S3) showed optimal results for whole grains [10]. This enhancement of bioactive compounds is attributed to the ability of CAP to disrupt plant cell walls and facilitate the release of bound phenolic compounds, thereby increasing their extractability and bioavailability.

Inactivation of Microorganisms on Food Contact Materials

Research has extended beyond direct food treatment to include CAP application on food contact materials (FCMs) for enhanced food safety. A recent study investigated the inactivation efficacy of CAP against Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus on three common FCMs: kraft paper, 304 stainless steel, and glass [29]. Using an atmospheric helium plasma jet (15 kV, 10.24 kHz, He 4 L/m), the researchers observed gradually increasing inactivation effects as plasma treatment duration increased (0-5 minutes).

The bactericidal efficacy varied significantly based on both the microbial species and the FCM surface characteristics. Salmonella typhimurium exhibited weaker resistance than Staphylococcus aureus to the same CAP treatment [29]. Under identical conditions, CAP demonstrated the strongest bactericidal effect on bacteria adhered to glass surfaces, followed by 304 stainless steel, with the weakest effect on kraft paper surfaces. These differences were attributed to the surface hydrophilicity and roughness of the FCMs, which influence bacterial adhesion and exposure to reactive plasma species [29]. Among three classical sterilization kinetic models evaluated (Log-linear, Weibull, and Log-linear + Shoulder + Tail), the Log-linear + Shoulder + Tail model provided the highest fitting degree for CAP inactivation kinetics on FCMs [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for CAP Treatment of Grains and Flours

Objective: To evaluate the effects of CAP treatment on microbial safety and bioactive compound enhancement in grains and flours.

Materials and Equipment:

- Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma reactor

- Whole grains and corresponding flours

- Polyethylene bags for sample containment

- Vortex mixer (capable of 3,400 rpm)

- Glass Petri dishes (15 cm diameter)

- Analytical equipment: UV-visible spectrophotometer, HPLC system

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Clean whole grains and mill portion to produce flour. Pass flour through standardized sieves (No. 40 & 50 mesh) to ensure uniform particle size [10].