Colonic Fermentation of Undigested Food: Mechanisms, Metabolites, and Therapeutic Applications in Human Health

This article provides a comprehensive review of the colonic fermentation of undigested dietary components, a critical process shaping human metabolic health.

Colonic Fermentation of Undigested Food: Mechanisms, Metabolites, and Therapeutic Applications in Human Health

Abstract

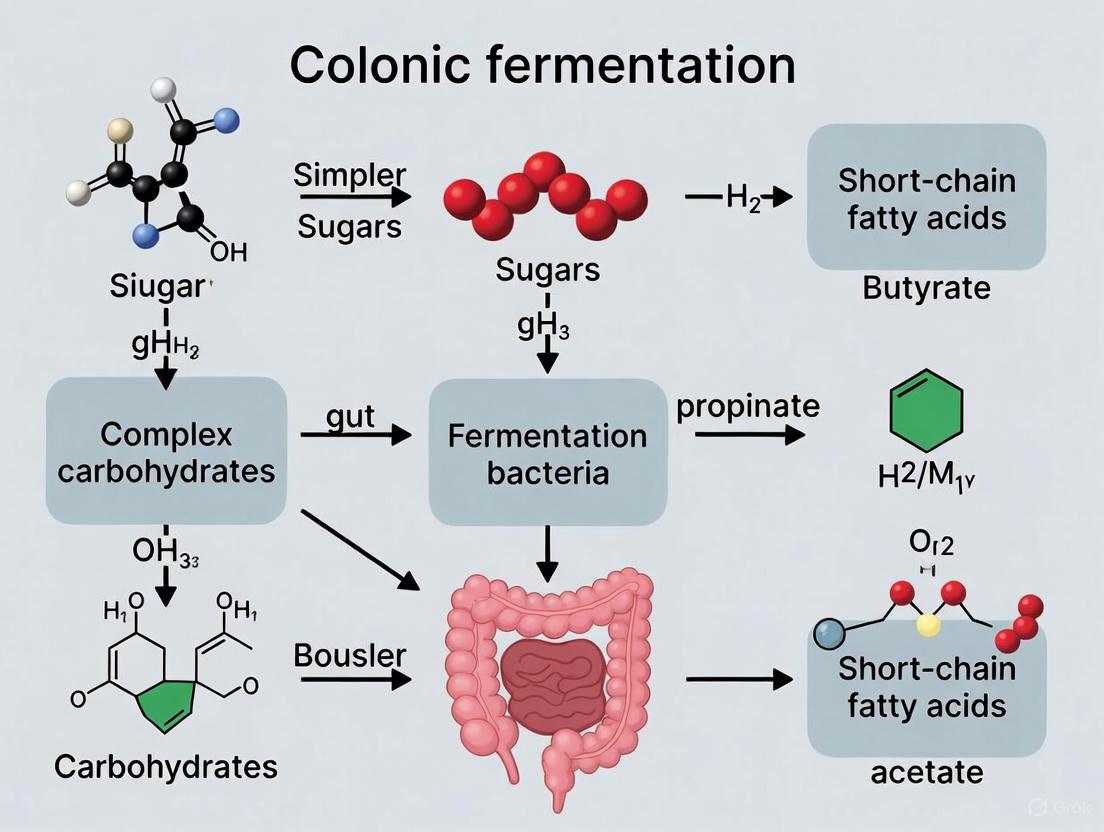

This article provides a comprehensive review of the colonic fermentation of undigested dietary components, a critical process shaping human metabolic health. It explores the foundational science of gut microbiota transforming fibers and resistant starches into key metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). The scope extends to established in vitro methodologies, such as the INFOGEST model, for studying these processes, and examines the challenges in translating research into targeted interventions. Finally, it synthesizes clinical evidence and comparative data on how fermented foods and specific microbial consortia modulate colonic fermentation, offering insights for developing microbiome-based therapeutics for conditions like colorectal cancer, metabolic disorders, and gastrointestinal diseases. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to harness colonic fermentation for precision medicine.

The Gut as a Bioreactor: Unraveling the Science of Colonic Fermentation

The traditional view of digestion as a process governed solely by host-derived enzymes has been fundamentally redefined. Current scientific understanding reveals that intestinal metabolism is a complex, cooperative endeavor between the host and the vast community of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract—the gut microbiota [1]. This symbiotic relationship facilitates the breakdown of dietary components and xenobiotics through intricate and dynamic interactions between host epithelial cells and gut microbes [2]. Disruptions in this fragile equilibrium can lead to metabolic and gastrointestinal diseases, highlighting the profound significance of this host-microbe symbiosis for human health [2]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of the core mechanisms governing intestinal metabolism and host-microbe relationships, framed within the context of colonic fermentation research.

The gut microbiota contributes a vast enzymatic repertoire that complements host capabilities, particularly in the fermentation of undigested food components that reach the colon. This collaborative processing generates a diverse array of metabolic products, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which serve as crucial energy sources and signaling molecules that influence systemic health [1] [3]. Understanding this sophisticated host-microbe symbiosis is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to develop targeted interventions for metabolic disorders, inflammatory conditions, and other microbiota-associated diseases.

Core Concepts and Terminologies

Fundamental Definitions

- Intestinal Metabolism: The metabolic processes exclusively occurring within the intestines that facilitate the breakdown and absorption of dietary nutrients and xenobiotics, entailing a multifaceted interaction between the host and gut bacteria [2]. These processes include nutrient sensing, digestion, absorption, energy harvesting, detoxification, and immunomodulation.

- Host-Microbe Symbiosis: A mutually beneficial relationship between the host organism and the gut microbiota, where both parties derive advantages from coexistence, including metabolic cooperation, immune education, and niche specialization [4].

- Colonic Fermentation: The anaerobic breakdown of undigested dietary components, primarily nondigestible carbohydrates, by gut microbiota in the colon, producing SCFAs, gases, and other metabolites [3] [4].

- Gut Metabolome: The cumulative metabolites produced by intestine-specific metabolic processes, both host and microbe-derived, which regulate intestinal immunometabolic homeostasis [2].

- Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates (MACs): Complex dietary components, primarily fibers and resistant starches, that resist host enzyme digestion in the upper GI tract and become available for microbial fermentation in the colon [4].

Conceptual Models of Host-Microbe Metabolic Cooperation

Two primary frameworks describe the enzymatic interaction between host and microbiota in the gut ecosystem [1]:

- The "Duet" Model: Represents sequential or complementary enzymatic activities where host enzymes initiate digestion and microbial enzymes complete it, or vice versa. For example, salivary and pancreatic amylases hydrolyze starch to maltose and oligosaccharides, which are subsequently fermented by microbial glycoside hydrolases into SCFAs in the colon.

- The "Orchestra" Model: Envisions a highly coordinated, multi-layered interaction where host and microbial enzymes operate in a spatially and temporally regulated manner with complex feedback loops. An exemplary orchestra interaction involves bile acids secreted by the liver being modified by microbial bile salt hydrolases, which subsequently modulate bile acid signaling via nuclear receptors (FXR, TGR5), influencing host metabolism and immune responses.

Key Metabolic Processes in Host-Microbe Symbiosis

Carbohydrate Fermentation and SCFA Production

The fermentation of nondigestible carbohydrates represents a fundamental metabolic cooperation between host and microbiota. While host enzymes effectively digest simple sugars and easily accessible starches, complex dietary fibers resist host enzymatic degradation and reach the colon intact [4]. Here, gut microbiota—particularly species belonging to Bacteroides, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and Bifidobacterium—deploy an extensive arsenal of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) to break down these complex substrates [1].

The principal products of this saccharolytic fermentation are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate, typically present in molar ratios ranging from 3:1:1 to 10:2:1 [3]. These SCFAs serve distinct but complementary physiological roles:

- Butyrate: Serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, exhibits anti-inflammatory properties, and regulates gene expression through inhibition of histone deacetylases [3].

- Propionate: Transferred to the liver where it participates in gluconeogenesis and satiety signaling through interaction with GPR41 and GPR43 receptors [3].

- Acetate: The most abundant SCFA, serves as an essential co-factor for microbial cross-feeding and influences cholesterol metabolism and central appetite regulation [3].

Table 1: Primary Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Physiological Roles

| SCFA | Primary Producers | Receptors | Major Physiological Functions | Dysregulation Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia spp. | GPR109a, GPR41 | Primary energy source for colonocytes; anti-inflammatory; histone deacetylase inhibitor; promotes gut barrier function | Reduced levels associated with IBD, colitis, and metabolic syndrome |

| Propionate | Bacteroides spp., Negativicutes, some Clostridium clusters | GPR41, GPR43 | Hepatic gluconeogenesis precursor; satiety signaling; cholesterol synthesis regulation | Impaired glucose homeostasis; disrupted energy balance |

| Acetate | Many commensal bacteria including Bifidobacterium spp. | GPR43 | Substrate for other bacteria; cholesterol metabolism and lipogenesis; central appetite regulation | Altered microbial composition; metabolic dysfunction |

Protein and Amino Acid Metabolism

When carbohydrate availability is limited, gut microbiota shift toward proteolytic fermentation, breaking down dietary and endogenous proteins that escape host digestion [3]. Specific Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes species ferment amino acids, producing both SCFAs and various potentially detrimental metabolites:

- Propionate production from aspartate, alanine, threonine, and methionine [3]

- Butyrate production from glutamate, lysine, histidine, cysteine, serine, and methionine [3]

- Generation of branched-chain fatty acids, ammonia, amines, phenols, and indoles

This metabolic flexibility allows the microbiota to maintain metabolic activity during periods of dietary carbohydrate restriction, though excessive proteolytic fermentation has been associated with mucosal inflammation and gut barrier dysfunction.

Bile Acid Metabolism

Bile acid transformation represents a quintessential example of host-microbe co-metabolism. Primary bile acids synthesized in the liver from cholesterol are conjugated to glycine or taurine before secretion into the intestine [1]. Gut microbes, particularly Clostridium and Bacteroides species, express bile salt hydrolases (BSH) that deconjugate these primary bile acids [2]. Further microbial modifications generate a diverse array of secondary bile acids that function as important signaling molecules through activation of nuclear receptor FXR and membrane receptor TGR5, influencing lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and immune function [2] [1].

Bioactivation of Dietary Phytochemicals

Gut microbiota significantly expand the host's metabolic capabilities by transforming dietary polyphenols and other phytochemicals into more bioavailable and active metabolites [1]. For instance, microbial communities convert glucoraphanin from cruciferous vegetables into isothiocyanate sulforaphane, a potent antioxidant and chemopreventive compound [1]. Similarly, complex polyphenols from fruits, vegetables, and tea undergo microbial biotransformation into simpler phenolic acids with enhanced bioavailability and biological activity, substantially contributing to their documented health benefits.

Table 2: Microbial Metabolic Capabilities and Health Implications

| Metabolic Process | Key Bacterial Taxa | Major Products | Health Implications | Associated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber Fermentation | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium | SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) | Gut health, reduced inflammation, improved glucose metabolism | GPR41, GPR43 signaling |

| Bile Acid Transformation | Clostridium, Bacteroides | Secondary bile acids | Lipid digestion, vitamin absorption, metabolic regulation | FXR, TGR5 signaling |

| Vitamin Synthesis | Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium | Vitamins K, B12, others | Coagulation, energy production, neural function | Various metabolic pathways |

| Polyphenol Metabolism | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Bioactive phenolic compounds | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory effects | Antioxidant response elements |

| Choline Metabolism | Desulfovibrio, Bacteroides | TMA, TMAO | Cardiovascular risk modulation | Conversion to TMA/TMAO |

| Tryptophan Metabolism | Escherichia, Bacteroides | Indole derivatives | Immune function, gut barrier integrity | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

Methodologies for Studying Host-Microbe Metabolic Interactions

Experimental Models and Systems

Research into host-microbe symbiosis employs a hierarchical approach utilizing multiple complementary model systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations for investigating specific aspects of intestinal metabolism.

In Vitro Systems

- Batch Culture Fermenters: Simple, reproducible systems using fecal inocula in defined media to study specific metabolic pathways under controlled conditions [3]. Useful for preliminary screening of substrate utilization and metabolite production.

- Continuous Culture Gut Models: Multi-chambered systems (e.g., SHIME, TIM-2) that simulate different regions of the human gastrointestinal tract, maintaining complex microbial communities for extended periods [3]. These models enable investigation of microbial community dynamics and metabolic responses to dietary interventions.

- Intestinal Organoids: Three-dimensional structures derived from intestinal stem cells that recapitulate key aspects of intestinal architecture and function [2]. As demonstrated by Dougherty et al., treatment of organoids with filtered fecal supernatants from infants revealed that microbial metabolites promote enterocyte proliferation and maturation, indicating that varied microbiota generates metabolites facilitating intestinal epithelial development [2].

In Vivo Models

- Germ-Free (GF) Mice: Raised in sterile isolators without any microorganisms, providing a blank slate for assessing microbial contributions to intestinal metabolism [2]. GF mice exhibit substantially altered intestinal development and metabolism compared to conventional counterparts, highlighting the essential role of microbiota in digestive processes [2].

- Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Mice: Germ-free mice colonized with human donor microbiota, enabling investigation of specific microbial communities in a controlled animal model [3].

- Antibiotic-Treated Mice: Animals treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics to deplete gut microbes, resulting in altered luminal metabolite profiles, mucosal metabolic signaling, and colonocyte transcriptome and metabolism [2]. This model helps elucidate the metabolic consequences of microbial depletion.

Analytical Approaches

- Metagenomics: High-throughput sequencing of total microbial DNA to determine taxonomic composition and genetic potential of the gut microbiome [3]. Reveals the presence of genes encoding specific metabolic enzymes.

- Metatranscriptomics: RNA sequencing to assess actively expressed genes and metabolic pathways under different physiological conditions [1].

- Metabolomics: Comprehensive profiling of metabolites in fecal, luminal, or systemic samples using mass spectrometry or NMR spectroscopy [1] [3]. Directly measures the metabolic output of host-microbe interactions.

- Targeted Functional Gene Analysis: Primer-based approaches targeting key metabolic genes (e.g., for butyrate synthesis pathways) to enumerate functional microbial groups beyond phylogenetic identification [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SCFA Production from Dietary Fiber Fermentation

Objective: To quantify and characterize short-chain fatty acid production from microbial fermentation of specific nondigestible carbohydrates using an in vitro batch culture system.

Materials and Reagents:

- Anaerobic workstation (e.g., Coy Laboratory Products)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Defined medium for gut microbiota (e.g., YCFA or similar)

- Substrate carbohydrates (e.g., fructo-oligosaccharides, arabinoxylan, resistant starch)

- Fresh fecal samples from healthy human donors (collected anaerobically)

- Gas chromatography system with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) or mass spectrometer (GC-MS)

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- PCR reagents for functional gene analysis

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect fresh fecal samples from healthy human donors (n=minimum 5) under anaerobic conditions. Homogenize samples in pre-reduced PBS (1:10 w/v) and filter through sterile mesh to remove large particles.

- Inoculum Preparation: Combine equal volumes of filtered fecal slurry from multiple donors to create a pooled inoculum. Alternatively, maintain donor-specific inocula for personalized response assessment.

- Fermentation Setup: In anaerobic chamber, aliquot 10 mL of defined medium into sterile fermentation vessels. Add test substrates at physiological concentrations (e.g., 1% w/v). Include negative controls (no substrate) and positive controls (known fermentable carbohydrate).

- Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate vessels with 1 mL of fecal slurry (final concentration 10% v/v). Seal vessels with butyl rubber stoppers to maintain anaerobiosis. Incubate at 37°C with constant agitation (150 rpm) for 24-48 hours.

- Sample Collection: At predetermined timepoints (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48h), aseptically remove 1 mL aliquots for:

- SCFA analysis: Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 10 min, collect supernatant, acidify with 1% formic acid, store at -80°C until analysis

- Microbial composition: Pellet cells for DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

- Functional gene expression: Preserve samples in RNA stabilization reagent for transcriptomic analysis

- SCFA Analysis by GC-FID:

- Derivatize samples with N-methyl-N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide

- Separate using DB-FFAP column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm)

- Employ temperature program: 80°C for 1 min, ramp to 120°C at 10°C/min, then to 240°C at 20°C/min, hold for 5 min

- Quantify acetate, propionate, butyrate, and branched-chain fatty acids against external calibration standards

- Microbial Community Analysis:

- Extract DNA using commercial kits with bead-beating step

- Amplify V4 region of 16S rRNA gene with dual-indexed primers

- Sequence on Illumina MiSeq platform (2×250 bp)

- Process data using QIIME2 or similar pipeline

- Functional Gene Quantification:

- Design primers targeting key butyrate synthesis genes (but, buk) and propionate pathways

- Perform quantitative PCR with SYBR Green chemistry

- Normalize to 16S rRNA gene copies

Data Analysis:

- Calculate SCFA production rates and yields relative to substrate consumed

- Determine correlations between specific microbial taxa and metabolite production

- Assess changes in microbial diversity (α- and β-diversity metrics)

- Integrate metabolite production with functional gene abundance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Investigating Host-Microbe Symbiosis

| Category | Specific Reagents/Models | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Models | SHIME (Simulator of Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem), TIM-2, Intestinal organoids | Study of microbial community dynamics, substrate utilization, host-microbe interactions | Requires specialized equipment; organoids need stem cell isolation and 3D culture expertise |

| Animal Models | Germ-free mice, Human microbiota-associated mice, Antibiotic-treated mice | Investigation of causal relationships in host-microbe interactions | GF facilities expensive; HMA mice require human donor screening; antibiotic cocktails must be validated |

| Molecular Biology Tools | 16S rRNA gene primers (V3-V4 region), Metagenomic sequencing kits, RNA stabilization reagents | Microbial community profiling, functional potential assessment, gene expression studies | Primer selection affects taxonomic resolution; rapid RNA preservation critical for accurate transcriptomics |

| Metabolite Analysis | GC-MS/FID systems, LC-MS platforms, NMR spectroscopy | Quantification of SCFAs, bile acids, neurotransmitters, other microbial metabolites | Derivatization often needed for volatile compounds; authentic standards required for quantification |

| Specialized Reagents | Defined media for gut microbiota (YCFA), Bile acid standards, SCFA calibration mixes | Cultivation of fastidious anaerobes, metabolite identification and quantification | Media must be pre-reduced for anaerobic work; standard purity critical for accurate quantification |

| Cell Culture Systems | Caco-2 cells, HT-29-MTX cells, Primary intestinal epithelial cells | Assessment of host responses to microbial metabolites, barrier function studies | Differentiation time varies; primary cells have limited lifespan and donor variability |

Signaling Pathways in Host-Microbe Communication

The continuous dialogue between gut microbiota and the host occurs through multiple sophisticated signaling pathways that translate microbial metabolic activities into host physiological responses. Three particularly significant pathways include SCFA receptor signaling, bile acid receptor activation, and enterocrine signaling.

SCFA Signaling Through G-Protein Coupled Receptors

SCFAs produced through microbial fermentation act as signaling molecules primarily through the G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) GPR41 (FFAR3) and GPR43 (FFAR2) [2] [3]. Butyrate also signals through GPR109a. Receptor activation triggers intracellular cascades that influence numerous physiological processes:

- GPR43 Activation: Predominantly by acetate and propionate, leading to enhanced expression of peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), promoting satiety and glucose homeostasis [3].

- GPR41 Activation: Primarily by propionate, resulting in sympathetic nervous system modulation and energy expenditure regulation [3].

- GPR109a Activation: By butyrate, inducing anti-inflammatory responses in colonic macrophages and dendritic cells, and promoting regulatory T-cell differentiation [3].

Bile Acid Signaling Through Nuclear Receptors

Microbial transformation of primary bile acids into secondary bile acids creates potent signaling molecules that activate the nuclear farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and membrane receptor TGR5 [2] [1]. These signaling pathways exert profound effects on host metabolism:

- FXR Activation: Regulates bile acid synthesis, lipid metabolism, and glucose homeostasis through modulation of gene expression networks in the liver and intestine [1].

- TGR5 Activation: Stimulates GLP-1 secretion in intestinal L-cells, enhances energy expenditure in brown adipose tissue, and exerts neuroprotective effects [1].

Microbial Influence on Enterocrine Signaling

Gut microbes significantly influence the production of enterocrine hormones through multiple direct and indirect mechanisms [2]. Microbial metabolites including SCFAs, secondary bile acids, and indole derivatives stimulate enteroendocrine cells to secrete hormones such as GLP-1, PYY, and serotonin (5-HT), which regulate gastrointestinal motility, appetite, glucose homeostasis, and mood [2].

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Interventions

The intricate metabolic interplay between host and microbiota presents numerous promising targets for therapeutic intervention in metabolic, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases.

Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutics

- Next-Generation Probiotics: Moving beyond traditional Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains to include species such as Akkermansia muciniphila (mucin degradation), Faecalibacterium prausnitzii* (butyrate production), and defined consortia targeting specific metabolic deficiencies [5].

- Prebiotic Strategies: Targeted supplementation with specific nondigestible carbohydrates (e.g., arabinoxylan oligosaccharides, resistant starch, fructo-oligosaccharides) to selectively stimulate growth of beneficial taxa and enhance production of health-promoting metabolites like butyrate [5] [4].

- Synbiotic Approaches: Rational combinations of prebiotics and probiotics designed to work synergistically, such as pairing Bifidobacterium strains with fructo-oligosaccharides that they efficiently utilize [6].

- Postbiotic Formulations: Administration of microbial metabolites themselves (e.g., SCFAs, secondary bile acids) or inactivated microbial cells to bypass the need for live microorganisms while still delivering beneficial effects [1].

Precision Nutrition Approaches

The understanding that individuals harbor unique microbial communities with distinct metabolic capabilities enables development of personalized nutritional strategies [5]. This includes dietary recommendations tailored to an individual's microbial composition and functional capacity, potentially determined through metagenomic sequencing and metabolomic profiling [5]. For instance, individuals with high abundance of Bacteroides species may respond differently to dietary interventions than those dominated by Prevotella, allowing for more effective, personalized dietary recommendations for metabolic disease management.

Drug Metabolism Considerations

The gut microbiota significantly influences the metabolism and efficacy of numerous pharmaceutical compounds, opening avenues for microbiome-informed drug development [2] [1]. Strategies include:

- Screening new chemical entities for microbial metabolism

- Developing microbiome-compatible formulations that maintain efficacy despite microbial transformation

- Considering an individual's microbial metabolic capacity when prescribing drugs subject to significant microbial metabolism

- Utilizing microbial enzymes for targeted drug activation in the colon

The paradigm of intestinal metabolism has evolved from a host-centric process to a sophisticated collaborative system between host and microbiota. This host-microbe symbiosis, particularly through colonic fermentation of undigested food components, profoundly influences not only gastrointestinal health but also systemic metabolic homeostasis, immune function, and even neurological processes. The intricate enzymatic cooperation between host and microbiota—conceptualized as both "duet" and "orchestra"—generates a diverse metabolome that serves as a key interface between diet, microbiota, and host physiology.

Ongoing research in this field continues to unravel the complex mechanisms underlying host-microbe metabolic interactions, providing unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic intervention. From next-generation probiotics and precision nutrition to microbiome-informed drug development, leveraging this symbiotic relationship holds tremendous promise for addressing the growing burden of metabolic, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases. As methodologies advance and our understanding deepens, targeting the gut microbiota and its metabolic output will undoubtedly play an increasingly prominent role in both preventive medicine and therapeutic strategies.

The human colonic microbiota, a complex ecosystem comprising over 1000 bacterial species, possesses an extensive metabolic repertoire that is distinct from but complementary to mammalian enzymes [3]. This microbial community plays an indispensable role in host health through the fermentation of undigested dietary components, primarily driven by specific functional groups including lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and butyrate-producing bacteria [3] [7]. The metabolic activities of these key microbial players result in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—particularly acetate, propionate, and butyrate—which exert profound effects on host physiology, including energy homeostasis, anti-inflammatory responses, and anti-carcinogenic activity [3] [8]. Understanding the intricate relationships between these microbial groups, their metabolic cross-feeding, and the environmental factors that shape their activities is fundamental to advancing research in colonic fermentation and its implications for human health and disease [7].

The human colon hosts a diverse microbial community dominated by four main bacterial phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria [8]. Within this ecosystem, specific functional groups perform specialized metabolic roles in the breakdown of undigested food components that escape host digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract [3]. The colonic microbiota's gene set, or microbiome, is estimated at approximately 3 million genes—150 times larger than the human genome—providing an extensive enzymatic capability that complements human physiology [3].

Research comparing germ-free and conventional animals, along with in vitro human fecal incubations, has demonstrated the critical importance of these microbial communities in host metabolism [3]. The microbial fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starches represents a fundamental process for energy harvest in the colon, with the metabolic outputs having systemic effects on host health [3] [7]. More recently, evidence has accumulated implicating the gut microbiota in various conditions including obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [3]. This review will focus on the key microbial players involved in these processes, with particular emphasis on lactic acid bacteria as primary fermenters and butyrate-producing bacteria as critical contributors to gut health.

Key Microbial Players and Their Metabolic Pathways

Lactic Acid Bacteria: Primary Fermenters

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including genera such as Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Lactococcus, and Pediococcus, typically belong to the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria phyla [9]. These bacteria are often considered primary fermenters, capable of initiating the breakdown of dietary carbohydrates into intermediate products including lactate, acetate, and ethanol [3]. In traditional fermented foods, these same bacterial groups drive the fermentation process and may act as probiotics when consumed, potentially inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms and contributing to host gut health [9].

LAB play a crucial role in shaping the gut environment through acid production, which lowers pH and creates selective pressure for other microbial community members [7]. However, lactate is typically present at negligible levels in adult feces due to extensive utilization by other bacteria, except in certain pathological conditions such as ulcerative colitis where it can be detected in significantly higher amounts [3]. This observation highlights the importance of metabolic cross-feeding relationships between LAB and other bacterial groups in maintaining gut homeostasis.

Butyrate-Producing Bacteria: Key Health-Promoting Metabolites

Butyrate-producing bacteria are predominantly found within the Firmicutes phylum, including some Lachnospiraceae and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [3]. Butyrate is arguably the most important SCFA for human health, serving as the primary energy source for colonocytes and exhibiting anti-cancer activity through its ability to induce apoptosis of colon cancer cells and regulate gene expression by inhibiting histone deacetylases [3]. There is also evidence that butyrate can activate intestinal gluconeogenesis via a cAMP-dependent mechanism with beneficial effects on glucose and energy homeostasis [3].

Butyrate production occurs mainly through two metabolic pathways identified by Louis and colleagues [3]. Genomic analyses have revealed that butyrate production capability is distributed across multiple bacterial taxa without strict phylogenetic consistency, necessitating functional gene approaches rather than 16S rRNA analysis alone to enumerate these important bacterial groups [3]. Butyrate can be produced directly from carbohydrate fermentation or through cross-feeding interactions where bacteria utilize intermediates such as lactate and acetate produced by other community members [7].

Cross-Feeding Dynamics and Metabolic Interactions

Cross-feeding represents a fundamental ecological principle within gut microbial communities, where metabolic products of one bacterium serve as substrates for another. These interactions significantly influence the final SCFA profile and overall gut environment [3]. For example, lactate produced by Bifidobacterium longum during growth on fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) completely disappears in co-culture with Eubacterium hallii, replaced by significant butyrate production—despite the fact that E. hallii alone cannot utilize the carbohydrate substrate [3].

Similarly, growth of Roseburia intestinalis on FOS is stimulated by acetate, and in co-culture with B. longum, growth of R. intestinalis is delayed until sufficient acetate produced by B. longum accumulates in the growth medium [3]. These cross-feeding relationships create metabolic interdependence among gut microbes, contributing to community stability and functional redundancy.

Table 1: Key Microbial Functional Groups in Colonic Fermentation

| Microbial Group | Representative Genera | Primary Metabolic Outputs | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) | Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Lactococcus, Pediococcus | Lactate, acetate, ethanol [3] [9] | Primary fermentation, pH reduction, pathogen inhibition [9] |

| Butyrate Producers | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Eubacterium, Lachnospiraceae members | Butyrate, acetate, CO₂ [3] [7] | Colonocyte energy source, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic [3] |

| Acetate Producers | Many bacterial groups including Bifidobacterium | Acetate [3] | Universal metabolite, precursor for butyrogenesis, cholesterol metabolism [3] |

| Propionate Producers | Bacteroides, Negativicutes, some Clostridium | Propionate, acetate, succinate [3] | Gluconeogenesis, satiety signaling [3] |

| Lactate-Utilizing Bacteria | Eubacterium hallii, Anaerositpes caccae | Butyrate, propionate [7] | Lactate conversion to other SCFAs, pH regulation [7] |

Quantitative Analysis of Microbial Metabolites

Short-Chain Fatty Acid Profiles and Ratios

The three most abundant SCFAs detected in feces are acetate, propionate, and butyrate, normally present in molar ratios ranging from 3:1:1 to 10:2:1 [3]. These ratios are consistent with values observed within the intestine in sudden death victims [3]. Each of these primary SCFAs performs distinct roles in human physiology:

Acetate: The most abundant SCFA, serves as an essential co-factor/metabolite for the growth of other bacteria (e.g., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii requires acetate for growth) [3]. Within the human body, acetate is transported to peripheral tissues and used in cholesterol metabolism and lipogenesis, and recent evidence from mouse studies indicates it plays a significant role in central appetite regulation [3].

Propionate: Serves as an energy source for epithelial cells and is transported to the liver where it participates in gluconeogenesis [3]. It is increasingly recognized as an important molecule in satiety signaling due to interaction with gut receptors (GPR41 and GPR43, also known as FFAR3 and FFAR2), which may activate intestinal gluconeogenesis [3].

Butyrate: Forms the key energy source for human colonocytes and has potential anti-cancer activity [3]. Butyrate also regulates gene expression by inhibiting histone deacetylases and activates intestinal gluconeogenesis via a cAMP-dependent mechanism [3].

The Butyrate Shift Phenomenon

Recent analyses of human volunteer studies have established that the proportions of SCFAs in fecal samples significantly shift toward butyrate as the overall concentration of SCFAs increases [7]. This "butyrate shift" has important implications for gut health, as butyrate plays a key role in maintaining colonic epithelium and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects [7]. Multiple factors may contribute to this phenomenon, including:

- Selection for butyrate-producing bacteria by certain types of dietary fiber

- Additional butyrate formation from lactate and acetate via cross-feeding

- Impact of decreased pH in the proximal colon as SCFA concentrations increase [7]

A mildly acidic pH has been shown to significantly impact microbial competition and the stoichiometry of butyrate production, creating conditions that favor butyrate-producing bacteria [7].

Table 2: Short-Chain Fatty Acid Characteristics and Physiological Roles

| SCFA | Typical Molar Ratio | Primary Producers | Major Physiological Roles | Health Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | 60% (3-10 in ratio) [3] | Many bacterial groups [3] | Cholesterol metabolism, lipogenesis, appetite regulation [3] | Essential co-factor for other bacteria; peripheral tissue metabolism [3] |

| Propionate | 20% (1-2 in ratio) [3] | Bacteroides species, Negativicutes, some Clostridium [3] | Gluconeogenesis, satiety signaling [3] | GPR41/43 activation; intestinal gluconeogenesis activation [3] |

| Butyrate | 20% (1 in ratio) [3] | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia [3] | Colonocyte energy, histone deacetylase inhibition, apoptosis induction [3] | Anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, energy homeostasis [3] [7] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Fermentation Models

Studying variations in the gut microbiota via in vivo methods is often restricted for ethical and safety reasons, making in vitro digestion models valuable tools for investigating the effects of food on the microbiome and related metabolite production [9]. These models range from complex automated dynamic systems to simple static models, all aiming to mimic human and animal digestion. Protocols validated by the INFOGEST static digestion and fermentation model are widely recommended for studying the characteristics of food matrices [9].

The INFOGEST model can be used to complement outcomes from advanced dynamic computerized models such as the Simulator of Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME) and the TNO Intestinal Model (TIM) [9]. These systems allow researchers to investigate microbial community dynamics and metabolite production under controlled conditions that simulate different regions of the gastrointestinal tract.

Methodological Workflow for In Vitro Colonic Fermentation

The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow for studying microbial fermentation using in vitro models:

Experimental Workflow for In Vitro Fermentation

This workflow typically begins with stool sample collection from human donors, followed by treatment preparation (e.g., test substrates, positive controls like fructooligosaccharides, and negative controls like sterile water) [9]. Samples undergo simulated digestion using the INFOGEST protocol before anaerobic incubation for 24 hours with stool inoculum [9]. Post-incubation, genomic DNA is extracted for bacterial composition analysis via 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the V3-V4 hypervariable region, while supernatants are collected for SCFA analysis using gas chromatography or mass spectrometry techniques [9].

Molecular and 'Omics Approaches

Advanced molecular techniques have revolutionized our ability to study gut microbial communities and their functional capacities. While 16S rRNA gene sequencing provides information about bacterial composition, it reveals little about metabolic activities [3]. Targeted approaches focusing on key metabolic genes offer more functional insights.

Primers designed against key genes in butyrate and propionate production pathways can help enumerate functional groups of bacteria in different cohorts [3]. This functional gene approach may prove more useful than 16S rRNA analysis alone for understanding fluctuations in metabolic activities. Additionally, metagenomic screening of bacterial genomes has identified numerous species containing butyrate production pathways, with no consistency within families, further supporting the need for functional rather than purely phylogenetic analyses [3].

Butyrate Signaling and Host Interactions

Butyrate and other SCFAs exert profound effects on host physiology through multiple signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates key molecular mechanisms through which butyrate influences host cellular processes:

Butyrate Signaling Pathways and Host Mechanisms

Butyrate regulates the expression of 5-20% of human genes through multiple mechanisms [8]. In colonic cell lines, at low concentrations (0.5 mM), 75% of the upregulated genes are dependent on ATP citrate lyase activity, while at high concentrations (5 mM), this proportion reverses, with 75% becoming independent of this enzyme [8]. This concentration-dependent shift in gene regulation mechanisms underscores the complexity of butyrate's effects on host cellular processes.

Through their capacity to modulate gene expression, SCFAs play pivotal roles in regulating critical cellular processes including proliferation and differentiation, highlighting their importance in maintaining tissue homeostasis, supporting development, and potentially influencing disease progression [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Fermentation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Colonic Fermentation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digestive Enzymes | Porcine pepsin (P6887), Porcine pancreatin (P7545), Human salivary amylase (A1031) [9] | Simulate human gastrointestinal digestion in INFOGEST model [9] | In vitro digestion preceding colonic fermentation [9] |

| Bile Salts & Digestive Components | Sodium taurodeoxycholate, Bovine blood hemoglobin, Trichloroacetic acid [9] | Emulate intestinal environment for lipid digestion and protein breakdown [9] | Physiological relevance in digestion models [9] |

| SCFA Standards | Acetate, propionate, isobutyrate, butyrate, formate, lactate standards [9] | Quantitative calibration for chromatographic analysis of fermentation products [9] | SCFA quantification via GC/MS or HPLC [9] |

| Prebiotic Controls | Fructooligosaccharides (F8052), Peptone from potatoes [9] | Positive control substrates for microbial fermentation studies [9] | Comparison of test substrates to known fermentable compounds [9] |

| Biochemical Assays | 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid, Maltose standard, Phosphocreatine disodium salt [9] | Quantification of carbohydrate utilization and metabolic activity [9] | Monitoring fermentation progress and microbial activity [9] |

| Buffer Systems | Sodium phosphate buffer, Sodium hydroxide, Hydrochloric acid [9] | pH control and maintenance of physiological conditions during fermentation [9] | Environmental parameter control in fermentation systems [9] |

The intricate relationships between lactic acid bacteria, butyrate producers, and other microbial functional groups in the human colon represent a sophisticated metabolic network with profound implications for human health. Understanding the key microbial players involved in colonic fermentation of undigested food components—from primary fermenters like lactic acid bacteria to butyrate-producing specialists—provides crucial insights for developing targeted nutritional interventions and therapeutic strategies.

The experimental methodologies outlined, including in vitro fermentation models and molecular approaches, offer powerful tools for investigating these complex microbial communities and their metabolic outputs. As research advances, the "butyrate shift" phenomenon and the critical roles of cross-feeding relationships underscore the importance of considering microbial ecology and community dynamics rather than focusing solely on individual bacterial species.

Future research directions should include further elucidation of the specific mechanisms underlying microbial cross-feeding, the development of more sophisticated in vitro models that better capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of the colonic environment, and translational studies exploring how manipulation of these key microbial players can be leveraged for improving human health and treating disease.

The human colon represents a critical interface where diet, microbial ecology, and host physiology converge through the process of colonic fermentation. This anaerobic process, primarily mediated by the complex consortium of gut microbiota, transforms indigestible dietary components, notably dietary fiber, into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—predominantly acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These bacterial metabolites exert profound effects on human health, influencing everything from colonic integrity and immune function to systemic metabolism [10] [11]. Over recent centuries, a marked decrease in dietary fiber intake has driven detrimental alterations in the gut microbiota, contributing to the global epidemic of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other metabolic disorders [12]. Understanding the precise metabolic pathways from fiber to SCFAs is therefore not only a fundamental scientific pursuit but also a venture with significant implications for therapeutic development and nutritional interventions. This whitepaper delineates the current scientific understanding of these pathways, framed within the context of colonic fermentation research, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide to this critical field.

Dietary Fiber: Definitions, Types, and Intake

Classification of Dietary Fibers

Dietary fiber comprises carbohydrate polymers that resist hydrolysis by human endogenous enzymes and absorption in the small intestine [12]. The official definition has evolved to include oligosaccharides, recognizing their similar physiological activities to traditional fibers [12]. Based on physiological properties and monomeric unit (MU) polymerization, dietary fibers are classified into three primary types, each with distinct structures and sources [12]:

- Non-Starch Polysaccharides (NSPs) (MU ≥ 10): Include cellulose, hemicellulose, pectins, inulin, and various hydrocolloids.

- Resistant Starches (RS) (MU ≥ 10): Categorized as RS1 (physically inaccessible, e.g., in milled grains), RS2 (ungelatinized, e.g., raw potatoes, green bananas), RS3 (retrograded, e.g., cooked and cooled potatoes), RS4 (chemically modified), and RS5 (amylose-lipid complexes).

- Resistant Oligosaccharides (ROS) (MU: 3–9): Include fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), and xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS).

The chemical structure, solubility, degree of polymerization, and viscosity of these fibers are critical determinants of their fermentability and the specificity of bacterial degradation in the colon [12] [11].

Global Intake Levels and Recommendations

Table 1: Global Dietary Fiber Intake Levels and Official Recommendations

| Region | Average Intake (g/day) | Recommended Intake (g/day) | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 17.6 (Women), 19.4 (Men) | 25-30 (Overall) | Chinese Dietary Reference Intake (2017) [12] |

| Japan | 18.0 (Women), 19.9 (Men) | 18 (Women), 21 (Men) | National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan (2019) [12] |

| USA | 15.2 (Women), 18.1 (Men) | 25 (Women), 38 (Men) | Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020-2025) [12] |

| Australia | 21.1 (Women), 24.8 (Men) | 28 (Women), 38 (Men) | Australian Health Survey (2011-2012) [12] |

| European Union | ~25 (Overall) | 30 (Overall) | EFSA Scientific Opinion (2010) [12] |

Globally, average dietary fiber intake ranges from 15 to 26 g/day, consistently falling below the recommended levels of 20 to 38 g/day established in most countries [12]. Discrepancies in intake and recommendations are influenced by factors such as dietary habits, body size, and tolerance to high-fiber diets [12]. The widespread failure to meet recommended intake levels underscores a significant modifiable factor in the global burden of non-communicable diseases.

The Gut Microbiota and Fermentation Machinery

The human colon harbors a dense and diverse ecosystem of over 1000 microbial species, dominated by the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria [11]. This community's collective genome encodes a vast repertoire of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), such as glycoside hydrolases (GHs) and polysaccharide lyases (PLs), which far exceed the host's endogenous digestive capabilities [12]. The ability of specific bacterial taxa to utilize particular dietary fibers is genetically predetermined, depending on whether their genomes encode the necessary enzymes, carbohydrate-binding proteins, and transporters [11].

Bacterial fermentation is an anaerobic process wherein these microbes break down complex carbohydrates into SCFAs, gases (H₂, CH₄, CO₂), and other metabolites [11]. The rate and extent of fermentation are influenced by the fiber's properties (e.g., solubility, particle size) and the gut transit time [10]. Soluble fibers (e.g., inulin, pectins, β-glucans) are generally fermented more rapidly than insoluble fibers (e.g., cellulose) [11]. This intricate interplay between substrate and microbe ultimately dictates the quantity and profile of SCFAs produced.

Figure 1: Core Pathway of Microbial Fermentation of Dietary Fiber to SCFAs. NSPs: Non-Starch Polysaccharides; RS: Resistant Starch; ROS: Resistant Oligosaccharides; CAZymes: Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes; GHs: Glycoside Hydrolases; PLs: Polysaccharide Lyases.

Metabolic Pathways of SCFA Production

The saccharolytic fermentation of dietary fiber primarily yields three major SCFAs: acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4). These acids account for over 90-95% of the SCFAs produced, with minor amounts of valerate, hexanoate, and branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs) derived from protein fermentation [11]. The metabolic pathways for their synthesis are distinct and often carried out by different bacterial specialists.

- Acetate Production: Acetate is the most abundant SCFA in the colon. It is produced through the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway by many obligate anaerobes, including Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium species. This pathway also serves as a key hydrogen sink, maintaining anaerobic conditions.

- Propionate Production: Propionate is generated via multiple pathways, with the succinate pathway (common in Bacteroidetes), the acrylate pathway (used by some Firmicutes like Coprococcus catus), and the propanediol pathway (which ferments deoxy sugars like rhamnose or fucose) being the most significant.

- Butyrate Production: Butyrate is a primary energy source for colonocytes. It is synthesized mainly through the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase pathway, employed by key butyrate producers such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Eubacterium rectale, which convert two molecules of acetate into one of butyrate.

The specific SCFA profile resulting from fermentation is highly dependent on the dietary fiber substrate, as different fibers selectively enrich for bacterial taxa that possess the requisite pathways [11] [13].

Table 2: SCFA Production from Different Dietary Substrates in In Vitro Fermentation (72h)

| Substrate | Acetate | Propionate | Butyrate | Key Microbial Shifts | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoprotein | High | High (delayed) | Moderate | Enrichment of Bacteroides ovatus, B. uniformis | [13] |

| Oat Bran | High (rapid) | High (rapid) | Lower | Enrichment of Bifidobacterium longum, B. adolescentis | [13] |

| Chicken | Moderate | Moderate | High (delayed) | Minimal change; small increase in Alistipes | [13] |

| Inulin | Increased | Increased (in YA) | Increased (44% in inaccessible pool) | Not Specified | [14] |

Experimental Models for Studying Colonic Fermentation

In Vitro Fermentation Models

In vitro models are indispensable tools for studying the fermentation of specific substrates without the ethical and financial constraints of human or animal trials. They allow for controlled, dynamic sampling and quantitative measurement of metabolites [11].

Static Batch Fermentation: This is a closed system in sealed tubes or reactors, inoculated with single bacterial strains or mixed fecal microbiota from humans or animals. It is simple and requires less inoculum but can inhibit bacterial growth due to nutrient limitation and metabolite accumulation over time [11]. A typical protocol involves:

- Inoculum Preparation: Fresh fecal samples from healthy donors are homogenized in an anaerobic buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) under a constant flow of CO₂ or N₂ to maintain anaerobiosis.

- Substrate Incubation: The substrate of interest is added to a fermentation vessel containing a defined nutritional medium and the fecal inoculum.

- Sampling: Headspace gases and liquid samples are collected at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72 h) for analysis of SCFAs (via GC-MS or HPLC), microbial composition (via 16S rRNA sequencing or MetaPhlAn), and other metabolites [11] [13].

Dynamic Multi-Stage Continuous Systems: These systems (e.g., the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem - SHIME) use multiple, sequentially connected vessels to simulate the different physiological conditions of the proximal, transverse, and distal colon. They are more complex but offer greater stability and a more accurate representation of the colonic environment by continuously adding fresh media and removing microbial suspensions and metabolites [11].

In Vivo and Clinical Methodologies

Human studies are crucial for validating findings from in vitro models. Recent advances have enabled more precise measurement of SCFA kinetics in vivo.

- Stable Tracer Methodology: A cutting-edge approach involves intravenous administration of [U-¹³C]-labeled SCFAs followed by serial blood draws. Compartmental modeling of plasma tracer enrichments and concentrations measured by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) allows for the calculation of SCFA production rates in both accessible (systemic circulation) and inaccessible (potentially intestinal) pools [14]. A recent randomized controlled trial used this method to demonstrate that inulin supplementation increased butyrate production by 44% in an inaccessible intestinal pool [14].

- Wireless Motility Capsule (WMC): This ambulatory device measures pH, temperature, and pressure as it traverses the gastrointestinal tract. A characteristic pH drop identifies the ileo-caecal junction, and a low caecal pH serves as a non-invasive, inverse surrogate biomarker for excessive SCFA production and fermentation, which has been linked to symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [15].

Figure 2: Integrated Experimental Workflow for SCFA Research. The workflow shows parallel in vitro and in vivo approaches converging on analytical measurement and data modeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SCFA Fermentation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application in Research | Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Dietary Fibers(e.g., Inulin, FOS, β-Glucans) | Used as controlled fermentation substrates to study structure-function relationships and selective bacterial growth. | [14] [11] [13] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers(e.g., [U-¹³C]-SCFAs) | Enable precise kinetic studies of SCFA production, turnover, and distribution in vivo via GC-MS. | [14] |

| Anaerobic Chamber/Gassing Kit | Creates and maintains a strict anaerobic environment (e.g., with CO₂/N₂/H₂ mix) essential for cultivating gut microbiota. | [16] [11] |

| Chromatography Standards(Pure SCFAs for GC/LC) | Required for calibrating instruments (GC-MS, HPLC) to accurately identify and quantify SCFA concentrations. | [14] [13] |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits(Optimized for stool) | Facilitate the analysis of microbial community composition and gene expression via 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics. | [13] |

| Pre-defined Media(for gut microbiota) | Provides standardized nutritional support for microbial growth in in vitro fermentation models. | [16] [11] |

Implications for Drug Metabolism and Therapeutics

The gut microbiome, through its metabolic activities including SCFA production, is a key modifier of drug metabolism and efficacy. The colon is a site of significant drug-microbiome interaction, especially for poorly soluble orally administered drugs or drugs that reach the colon via biliary excretion [16].

- Microbial Drug Metabolism: Gut microbiota encode enzymes that can directly metabolize drugs, altering their bioavailability and toxicity. An ex vivo fermentation screening platform identified that 5 out of 12 tested drugs (sulfasalazine, sulfinpyrazone, sulindac, nizatidine, and risperidone) were biotransformed by human gut microbiota [16]. Sulfasalazine is a canonical example of a prodrug designed to be activated by gut bacterial azoreductases into active 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and sulfapyridine [16].

- SCFAs as Therapeutic Modulators: SCFAs, particularly butyrate, influence host health at multiple levels. Butyrate is a primary energy source for colonocytes, helps maintain gut barrier integrity, and has anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic properties, partly through its role as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor [10]. This has therapeutic implications for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Furthermore, SCFAs can indirectly influence drug response by modulating host physiology, immune function, and systemic metabolism [17].

The metabolic pathways converting dietary fiber to SCFAs represent a cornerstone of the symbiotic relationship between the host and the gut microbiota. The type and structure of dietary fiber dictate the rate of fermentation, the resulting SCFA profile, and the subsequent physiological effects. Advanced in vitro models and sophisticated in vivo techniques, such as stable isotope tracers, are unraveling the complex kinetics and health impacts of these critical metabolites. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these pathways is increasingly vital. The gut microbiome and its metabolites are now recognized as significant variables influencing drug pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety. Future research will likely focus on designing targeted dietary interventions and novel therapeutics that leverage these pathways—for instance, by developing fibers with specific fermentation properties or by manipulating the microbiota to optimize SCFA production—to prevent and treat a wide spectrum of metabolic, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases.

The gut metabolome represents the complete set of small molecule metabolites present in the gastrointestinal tract, constituting a dynamic interface between host physiology, dietary components, and the gut microbiota. This complex mixture arises from both host-derived metabolic processes and the biochemical activities of trillions of resident microorganisms. In the context of colonic fermentation of undigested food components, the gut metabolome serves as a functional readout of microbial activity and host-microbe interactions [18] [19]. The intricate chemical dialogue between microbial metabolites and host signaling pathways fundamentally influences gastrointestinal health, systemic metabolism, and disease susceptibility [20] [18].

Understanding the precise origins and functional consequences of these metabolites provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. This technical guide comprehensively defines microbial and host-derived metabolites within the gut ecosystem, detailing their sources, measurement methodologies, and functional significance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts in Gut Metabolome Composition

Origins and Classification of Gut Metabolites

The gut metabolome comprises molecules originating from distinct sources, each contributing to the overall metabolic landscape:

- Host-Derived Metabolites: Synthesized by human biochemical pathways, these include digestive enzymes, bile acids, mucins, and other secretions essential for nutrient processing and gut homeostasis [18] [19].

- Microbiota-Derived Metabolites: Produced by gut microorganisms through fermentation of dietary components or transformation of host secretions. These include short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan catabolites, and secondary bile acids [20] [19].

- Diet-Derived Metabolites: Originating directly from food sources, including undigested carbohydrates, fibers, polyphenols, and other complex compounds that serve as substrates for microbial metabolism [19] [21].

Table 1: Major Classes of Microbial-Derived Metabolites and Their Microbial Producers

| Metabolite Class | Specific Metabolites | Producing Bacterial Species/Genera | Primary Dietary Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate | Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Prevotella spp., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp., Blautia hydrogenotrophica, Clostridium spp. [20] | Dietary fiber, resistant starch [21] |

| Tryptophan Catabolites | Indole, IAA, IPA, IAld, Tryptamine | Clostridium sporogenes, Bacteroides ovatus, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus spp., Ruminococcus gnavus [20] | Dietary tryptophan [20] |

| Bile Acid Metabolites | Lithocholic acid, Deoxycholic acid, Ursodeoxycholic acid | Multiple species expressing bile salt hydrolases (BSHs) and 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (7α-HSDH) [20] [19] | Primary bile acids (host-derived) [20] |

Quantitative Distribution and Compartmentalization

The distribution and concentration of metabolites vary significantly between gut compartments and systemic circulation. A recent comparative study of paired fecal and blood metabolomes revealed critical insights:

- Fecal vs. Blood Metabolome Correlations: Phenotypic correlations between paired fecal and blood metabolites are generally low (correlation coefficients: 0.05 ± 0.12), with only 8 of 132 metabolites showing significant correlations (coefficients >0.3) [22].

- Microbiome Explainability: Fecal metabolites show substantially higher predictability from gut microbiome composition (mean correlation coefficient: 0.40±0.15) compared to blood metabolites (mean correlation coefficient: 0.09±0.11) [22].

- Well-Predicted Metabolites: Based on taxonomic composition, 98 fecal metabolites were well-predicted (correlation coefficient >0.3), including SCFAs, bile acids, and phenylpropanoic acids, while only 10 blood metabolites met this threshold [22].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Distinguishing Metabolite Origins

| Experimental Approach | Core Methodology | Key Findings | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic-mediated Microbiome Depletion [19] | Administration of non-absorbable antibiotics (vancomycin, neomycin) + polyethylene glycol purge; comparison of pre- vs. post-depletion metabolomes | 2,856 microbial products decreased post-depletion; 1,057 microbial substrates increased post-depletion; 2,496 diet-derived metabolites identified | Gold standard for identifying microbiome-dependent metabolites; cannot distinguish direct vs. indirect microbial effects |

| Controlled Feeding Studies [19] | Subjects randomized to defined diets (omnivore vs. enteral nutrition); metabolomic profiling across diet groups | In depleted microbiome: 162 omnivore-derived metabolites identified vs. 2496 when considering intact microbiome | Isolates diet-derived metabolites; reveals microbiome's role in diet metabolism; requires strict dietary control |

| Germ-Free vs. Conventionalized Models [18] | Comparison of metabolite profiles between germ-free and conventionally colonized animals | Altered secondary bile acids, SCFAs, and indole derivatives in germ-free animals | Provides causal evidence for microbial contribution; limited translational relevance to humans |

Methodologies for Gut Metabolome Characterization

Experimental Workflows for Metabolite Origin Determination

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for distinguishing metabolite origins through microbiome depletion. LC-MS: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; GC-MS: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry.

Analytical Techniques for Metabolite Quantification

Targeted Metabolomics for Absolute Quantification:

- Short-Chain Fatty Acid Analysis: Acidification with hydrochloric acid, extraction with diethyl ether, derivatization with N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide, and detection using gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) [23]. Quantification against standard solutions of acetate, propionate, and butyrate with 2-ethyl butyric acid as internal standard.

- Bile Acid Profiling: Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with multiple reaction monitoring for primary, secondary, and conjugated bile acids. Identification based on retention time matching to pure standards and characteristic fragmentation patterns [20] [19].

Untargeted Metabolomics for Comprehensive Discovery:

- High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) coupled with reverse-phase and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) to maximize metabolite coverage. Data processing using XCMS, MZmine, or similar platforms for peak picking, alignment, and annotation [19].

- Metabolite identification using reference standards when available, or putative annotation based on accurate mass, isotopic pattern, and fragmentation spectra against databases such as HMDB, METLIN, and MassBank.

Computational Integration with Microbial Communities

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GEMs):

- MICOM Platform: Uses flux balance analysis under mass steady-state assumptions to predict microbial metabolite production as fluxes (units of concentration per time) [23]. Constraints based on dietary compound availability and microbial community composition.

- AGORA2 Metabolic Reconstructions: Resource of genome-scale metabolic models for human gut microbes, enabling in silico prediction of SCFA production from defined nutritional inputs [23].

Machine Learning Approaches:

- LOCATE (Latent variables Of miCrobiome And meTabolites rElations): Treats microbiome-metabolome relations as equilibria of complex interactions, using a latent representation to predict host condition [24]. Demonstrates superior performance for predicting metabolite concentrations from microbiome composition compared to linear models.

- Random Forest Regression: Applied to predict metabolite abundances from taxonomic composition or microbial pathways, with performance evaluation through cross-validation [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gut Metabolome Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Product Examples | Primary Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics for Microbiome Depletion | Vancomycin, Neomycin (non-absorbable) | Selective reduction of gut microbial load to identify microbiome-derived metabolites [19] | Requires polyethylene glycol purge for complete clearance; confirm depletion via 16S rRNA quantification |

| Chromatography Columns | HILIC, C18 reverse-phase | Separation of polar and non-polar metabolites prior to mass spectrometry | Column choice dramatically impacts metabolite coverage; requires method optimization |

| Metabolite Standards | SCFA mixtures, bile acid panels, isotopically labeled internal standards (e.g., 13C-acetate) | Absolute quantification of targeted metabolites; quality control | Use deuterated/internal standards for quantification accuracy; purity >95% recommended |

| DNA Extraction Kits | MOBIO PowerSoil, QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | Concurrent microbiome analysis from same fecal samples | Extraction method significantly impacts microbial community profiles; maintain consistency |

| In Silico Modeling Platforms | MICOM, AGORA2 reconstructions | Prediction of community-level metabolite production from genomic data [23] | Accuracy varies by dietary context; better performance with complex carbohydrates vs. other compounds |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | V3-V4 (341F/806R), other hypervariable region targets | Taxonomic profiling of microbial communities | V region selection introduces bias; V3-V4 most common but may miss specific taxa [25] |

Functional Significance of Key Metabolite Classes

Signaling Pathways and Host Receptors

Diagram 2: Key microbial metabolite classes and their signaling pathways. SCFAs: Short-Chain Fatty Acids; GPCR: G-Protein Coupled Receptor; Tregs: Regulatory T cells; tMacs: Tolerogenic Macrophages; LCA: Lithocholic Acid; DCA: Deoxycholic Acid; FXR: Farnesoid X Receptor; TGR5: G Protein-coupled Bile Acid Receptor; I3A: Indole-3-Aldehyde; IAld: Indole-3-Aldehyde; IPA: Indole-3-Propionic Acid; AHR: Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor.

Impact on Intestinal and Systemic Homeostasis

The functional effects of gut microbial metabolites extend from local intestinal processes to systemic physiological regulation:

- Immune Cell Differentiation: SCFAs promote differentiation and function of immunosuppressive cells including regulatory T cells (Tregs), tolerogenic macrophages (tMacs), and tolerogenic dendritic cells (tDCs), while inhibiting inflammatory cells such as inflammatory Macs (iMacs) and Th17 cells [20].

- Intestinal Barrier Function: Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, enhancing epithelial barrier integrity through upregulation of tight junction proteins and promoting mucus production [20] [18].

- Systemic Metabolic Regulation: Secondary bile acids and SCFAs influence glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism through activation of FXR and GPCR receptors, impacting hepatic gluconeogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and energy expenditure [20] [18].

- Gut-Brain Axis Communication: Microbial metabolites including SCFAs, tryptamine, and indole derivatives modulate enteric nervous system function and influence central processes through vagal afferent signaling [18].

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The strategic manipulation of gut microbial metabolites presents promising avenues for therapeutic intervention:

- Microbiome-Informed Dietary Interventions: Baseline microbiota composition (e.g., Prevotella-rich vs. Bacteroides-rich enterotypes) determines response to dietary fiber interventions, suggesting personalized nutritional approaches [21].

- Metabolite-Based Biomarker Discovery: Specific microbial metabolites, including secondary bile acids and indole derivatives, show promise as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for cardiometabolic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and colorectal cancer [22] [19].

- Targeted Microbial Consortia: Defined communities of metabolite-producing bacteria (e.g., butyrate-producing consortia) represent a novel therapeutic modality for restoring metabolic deficiencies in dysbiotic states [20] [21].

- Enzyme-Targeted Inhibitors: Selective inhibition of microbial enzymes (e.g., bile salt hydrolases) offers precision approaches to modulate metabolite pools without broad-spectrum microbiome disruption [20].

The gut metabolome represents a rich source of biological insight and therapeutic potential, with advanced methodologies now enabling precise dissection of microbial and host contributions to this complex chemical environment. Integration of multi-omics datasets with computational modeling and controlled intervention studies continues to accelerate our understanding of how microbial metabolites shape human health and disease.

The colon represents a critical interface where host physiology and the gut microbiota interact through the fermentation of undigested food components. This process is not merely digestive but is fundamental to maintaining host health, influencing everything from local barrier integrity to systemic immunity. Colonic fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starches by gut microbes produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which serve as key signaling molecules and energy sources [26] [27]. These metabolites and others directly modulate the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier (IEB) and the more recently discovered gut vascular barrier (GVB) [28] [18]. Disruption of these barriers, often described as "leaky gut," facilitates the translocation of bacteria and inflammatory molecules into systemic circulation, contributing to various pathological conditions [28] [29] [30]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to provide an in-depth technical guide on how colonic fermentation products impact host physiology, with a specific focus on barrier function, immune regulation, and systemic signaling pathways relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Colonic Fermentation and Key Microbial Metabolites

The colon harbors a complex microbial ecosystem that ferments non-digestible carbohydrates and other dietary substrates. The metabolic output of this fermentation is highly dependent on the structural characteristics of the dietary inputs and the composition of the microbial community [26] [27].

- Resistant Starch (RS) Fermentation: The fermentative behavior of RS and its resulting SCFA profile are dictated by structural domains such as amylose-to-amylopectin ratio, granular morphology, and crystalline type [26]. For instance, high-amylose, B-type crystalline RS selectively enriches for butyrate-producing bacteria (e.g., Ruminococcus and Bifidobacterium), thereby enhancing butyrate production. Conversely, retrograded RS may promote Bacteroides and alter the acetate-to-propionate ratio [26].

- SCFA Production and Functions: SCFAs, primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are the most studied fermentation metabolites. Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, maintains epithelial barrier integrity, and possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties, including histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition [26]. Propionate is involved in gluconeogenesis and cholesterol synthesis in the liver, while acetate enters systemic circulation to influence appetite regulation and peripheral tissues [26] [18].

- Other Bioactive Metabolites: Beyond SCFAs, microbial fermentation of proteins and amino acids can produce metabolites like branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs), biogenic amines, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and ammonia, which in excess can be detrimental to barrier health [27]. Conversely, fermentation of dietary polyphenols and yeast-derived β-glucans/MOS yields metabolites with anti-inflammatory and barrier-protective effects [31].

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Physiological Roles in Host Physiology

| Metabolite | Primary Microbial Producers | Key Physiological Roles | Impact on Barriers & Immunity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Ruminococcus, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Primary energy source for colonocytes, HDAC inhibition, anti-inflammatory [26] | Enhances tight junction proteins (ZO-1), reduces inflammation, supports GVB integrity [28] [26] |

| Propionate | Bacteroides, Phascolarctobacterium | Gluconeogenesis precursor, cholesterol metabolism, immune cell regulation [26] | Binds to GPCRs (GPR41/43) on immune cells, exerts anti-inflammatory effects [26] [18] |

| Acetate | Many saccharolytic bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium) | Substrate for systemic metabolism, lipogenesis, cross-feeding other bacteria [26] [31] | Contributes to mucus layer viscosity, supports overall epithelial health [28] |

| Yeast β-Glucans/MOS Metabolites | Microbes utilizing yeast cell walls | Immunomodulation, pathogen agglutination [31] | Increases IL-10 production, improves transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) [31] |

The Multi-Layered Intestinal Barrier System

The intestine is protected by a sophisticated, multi-layered barrier system that is profoundly influenced by microbial metabolites.

The Intestinal Epithelial Barrier (IEB)

The IEB is a continuous monolayer of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) bound together by tight junction (TJ) proteins like Zonula Occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudins [28] [30]. A critical component is the mucus layer, secreted by goblet cells, which physically separates the luminal microbiota from the epithelium [28] [30]. The cellular hierarchy of the IEB is maintained within the colonic crypts, which house LGR5+ stem cells that give rise to all mature epithelial lineages, including colonocytes, goblet cells, and enteroendocrine cells [30]. The balance between proliferation, differentiation, and extrusion is regulated by signaling pathways such as WNT, Notch, and BMP [30].

The Gut Vascular Barrier (GVB)

Beyond the IEB lies the GVB, a specialized endothelial barrier that controls the passage of molecules and bacteria from the gut lamina propria into the portal circulation and systemic organs [28]. Structurally analogous to the blood-brain barrier, the GVB is composed of endothelial cells sealed by tight junctions, supported by pericytes and enteric glial cells [28]. Its integrity is regulated by the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Activation of this pathway promotes a sealed barrier, while its disruption, as seen during Salmonella infection, leads to upregulation of Plasmalemma Vesicle-Associated Protein-1 (PV1) and increased vascular permeability, facilitating bacterial dissemination to the liver and spleen [28]. GVB dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcoholic liver disease, and colorectal cancer metastasis [28].

Experimental Models for Assessing Barrier Integrity and Immunity

Investigating host-microbe interactions requires robust in vitro and in vivo models. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

In Vivo Model: Assessing Probiotic Effects in a Murine Infection Model

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a multi-strain probiotic formulation (MPF) in preserving intestinal barrier integrity against Salmonella typhimurium challenge [28].

Materials:

- Animals: C57BL/6J mice.

- Test Material: Multi-strain probiotic (e.g., Lactobacillus rhamnosus LR32, Bifidobacterium lactis BL04, Bifidobacterium longum BB536).

- Pathogen: Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL3261AT (attenuated, mCherry-labeled).

- Key Reagents: Formaldehyde, OCT compound, anti-ZO-1 antibody, anti-PV1 antibody, Alcian Blue/PAS stain, collagenase D, LB agar with chloramphenicol.

Methodology:

- Pretreatment: Administer MPF (e.g., 10^8 CFUs/strain) daily to mice via oral gavage for 10 days.

- Infection: Orally infect pretreated and control mice with Salmonella (10^9–10^11 CFU).

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize mice 6-16 hours post-infection. Aseptically remove the colon and ileum.

- Bacterial Translocation Assay:

- Digest colon tissue with collagenase D.

- Lyse cells and plate homogenates on chloramphenicol-containing LB agar.

- Quantify Salmonella CFUs after overnight culture to assess systemic translocation [28].

- Histological & Immunofluorescence Analysis:

- Fix tissues in formaldehyde or PLP buffer for immunofluorescence.

- Embed in paraffin for H&E staining (to assess villus/crypt morphology) and Alcian Blue/PAS staining (to quantify acid/neutral mucins in the mucus layer).

- For immunofluorescence, embed tissues in OCT and section. Stain with antibodies against ZO-1 (for IEB integrity) and PV1 (for GVB integrity). Quantify fluorescence intensity [28].

In Vitro Model: Colon-on-a-Plate with Host Cell Co-Culture