Combating Nutritional Dilution: Science-Backed Strategies for Nutrient-Dense Crops in Modern Agriculture

This article addresses the critical challenge of nutritional dilution, the declining concentration of vitamins, minerals, and proteins in modern crops driven by soil degradation, climate change, and intensive farming practices.

Combating Nutritional Dilution: Science-Backed Strategies for Nutrient-Dense Crops in Modern Agriculture

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of nutritional dilution, the declining concentration of vitamins, minerals, and proteins in modern crops driven by soil degradation, climate change, and intensive farming practices. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes the latest interdisciplinary research to explore the biochemical mechanisms behind nutrient loss, evaluate emerging remediation strategies—from advanced breeding to precision agronomy—and discuss the implications for clinical research and public health. The content provides a foundational understanding, practical methodologies, troubleshooting for implementation, and a comparative validation of approaches to build resilient, nutrient-secure food systems.

The Silent Crisis: Understanding the Causes and Scale of Nutrient Decline in Our Food

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is nutritional dilution, and why is it a significant concern in modern agriculture? Nutritional dilution refers to the decline in the concentration of essential nutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, in edible parts of crops. This phenomenon is a significant concern because it can lead to reduced dietary nutritional value, potentially contributing to hidden hunger and impacting human health, even when caloric intake is sufficient [1].

Q2: How does climate change exacerbate the problem of nutritional dilution? Climate change disrupts agricultural nutrient dynamics through increased temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events. These changes can alter soil nutrient cycles, microbial activity, and crop physiology. For instance, elevated CO2 levels can reduce grain quality, while erratic rainfall increases nutrient losses through leaching and runoff, worsening nutritional dilution [1].

Q3: What are the limitations of conventional fertilizer practices in addressing nutritional dilution? Conventional practices often rely on excessive chemical fertilizer use, which contributes to nutrient losses, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions. These methods are inefficient; for example, only 30–40% of applied nitrogen is typically utilized by the crop, with the rest lost to the environment, failing to ensure nutrients are effectively translated into the harvested crop [1].

Q4: Which emerging nutrient management strategies are most effective for reducing nutritional dilution? Integrated Nutrient Management (INM), which combines organic and inorganic sources, and precision agriculture techniques like Site-Specific Nutrient Management (SSNM) are highly effective. These strategies improve nutrient use efficiency (NUE), enhance soil health, and can increase crop yields by 8–150% compared to conventional practices, thereby countering dilution [1].

Q5: How can researchers accurately diagnose and monitor nutritional dilution in field experiments? Diagnosis requires monitoring soil nutrient availability, plant nutrient uptake, and the final nutrient concentration in the harvested yield. Methodologies include soil and plant tissue sampling, using decision support systems for nutrient management planning, and employing precision agriculture tools to assess spatial and temporal variability in nutrient levels [1].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Nutritional Dilution

Protocol 1: Evaluating Integrated Nutrient Management (INM)

Objective: To assess the impact of combined organic and inorganic fertilizers on crop nutritional quality and yield.

- Experimental Design: Establish a randomized complete block design with a minimum of four treatments replicated three times.

- Treatment Application:

- T1: Control (No fertilizer).

- T2: 100% recommended dose of NPK chemical fertilizers.

- T3: 75% recommended NPK + 10 t ha⁻¹ Farmyard Manure (FYM).

- T4: 75% recommended NPK + 10 t ha⁻¹ FYM + Bioinoculants.

- Data Collection:

- Soil Analysis: Pre-sowing and post-harvest analysis of soil for major nutrients (N, P, K), organic carbon, and microbial activity.

- Plant Tissue Analysis: Sample plant tissue at critical growth stages to measure nutrient uptake.

- Yield and Quality Analysis: At harvest, measure grain and straw yield. Analyze grain for protein content and micronutrient concentrations (e.g., Zn, Fe).

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze data using ANOVA, and compare treatment means with appropriate post-hoc tests (e.g., Tukey's HSD) at a 5% significance level [1].

Protocol 2: Implementing Site-Specific Nutrient Management (SSNM)

Objective: To optimize nutrient application based on localized field requirements to enhance Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) and reduce losses.

- Field Characterization: Divide the experimental field into management zones based on soil test results, crop yield history, and topography.

- Sensor-Based Assessment: Use soil sensors or remote sensing (e.g., NDVI from drones) to assess spatial variability in soil fertility and crop nitrogen status during the growing season.

- Variable-Rate Application: Apply fertilizers using variable-rate technology, tailoring the rate of N, P, and K to the needs of each specific management zone. Banding application of phosphorus is often more efficient than broadcasting [1].

- Validation: Compare the SSNM approach with a uniform application practice, measuring differences in yield, nutrient concentration in grains, and post-harvest soil nutrient levels to calculate NUE and apparent nutrient recovery.

The following table summarizes quantitative data on the performance of various nutrient management strategies in mitigating nutritional dilution and improving sustainability.

Table 1: Comparison of Nutrient Management Strategies and Their Impacts

| Strategy | Key Performance Metrics | Impact on Nutritional Dilution & Sustainability | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Nutrient Management (INM) [1] | Yield increase of 8% to 150%; improved soil organic carbon. | Reduces reliance on chemical fertilizers; enhances nutrient availability and grain quality. | Requires access to quality organic amendments; management is more complex. |

| Precision Agriculture & SSNM [1] | Can significantly improve Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE); reduces fertilizer losses. | Ensures optimal nutrient availability during critical growth stages, improving nutrient content in grains. | High initial investment in technology and skills for data interpretation. |

| Conservation Agriculture [1] | Enhances soil moisture retention; improves soil structure. | Builds soil health and resilience, creating a more stable environment for nutrient uptake. | Requires changes to traditional tillage practices; weed management can be challenging. |

| 4R Nutrient Stewardship [1] | Aims to increase Fertilizer Utilization Efficiency (FUE). | Minimizes nutrient losses to the environment, making more nutrients available for the crop. | Involves careful planning for right source, rate, time, and place of application. |

| Biofertilizers & Biostimulants [1] | Reduces chemical N fertilizer requirement; promotes soil microbial activity. | Improves plant nutrient acquisition, potentially increasing nutrient density. | Effectiveness can be dependent on specific soil and environmental conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Nutritional Dilution Research

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Soil Test Kits (N, P, K, pH) | For initial and ongoing assessment of soil nutrient status and acidity, which forms the basis for fertilizer recommendations. |

| Plant Tissue Digestation Reagents (e.g., HNO₃, H₂O₂) | Used in microwave-assisted digestion to prepare plant tissue samples for elemental analysis. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Standards | Certified reference materials for calibrating ICP-OES or ICP-MS instruments to accurately quantify micronutrients (e.g., Zn, Fe) in plant digests. |

| Bioinoculants (e.g., Rhizobium, Azotobacter, Mycorrhizae) | Microbial formulations used as treatments to enhance biological nitrogen fixation and improve phosphorus solubility and uptake by plants. |

| Controlled-Release Fertilizer Coatings (e.g., polymer-coated urea) | Materials studied to create fertilizers that release nutrients in sync with crop demand, improving NUE and reducing losses. |

| Farmyard Manure (FYM) / Compost | Standardized organic amendment used in INM studies to improve soil structure, water-holding capacity, and slow-release nutrient supply. |

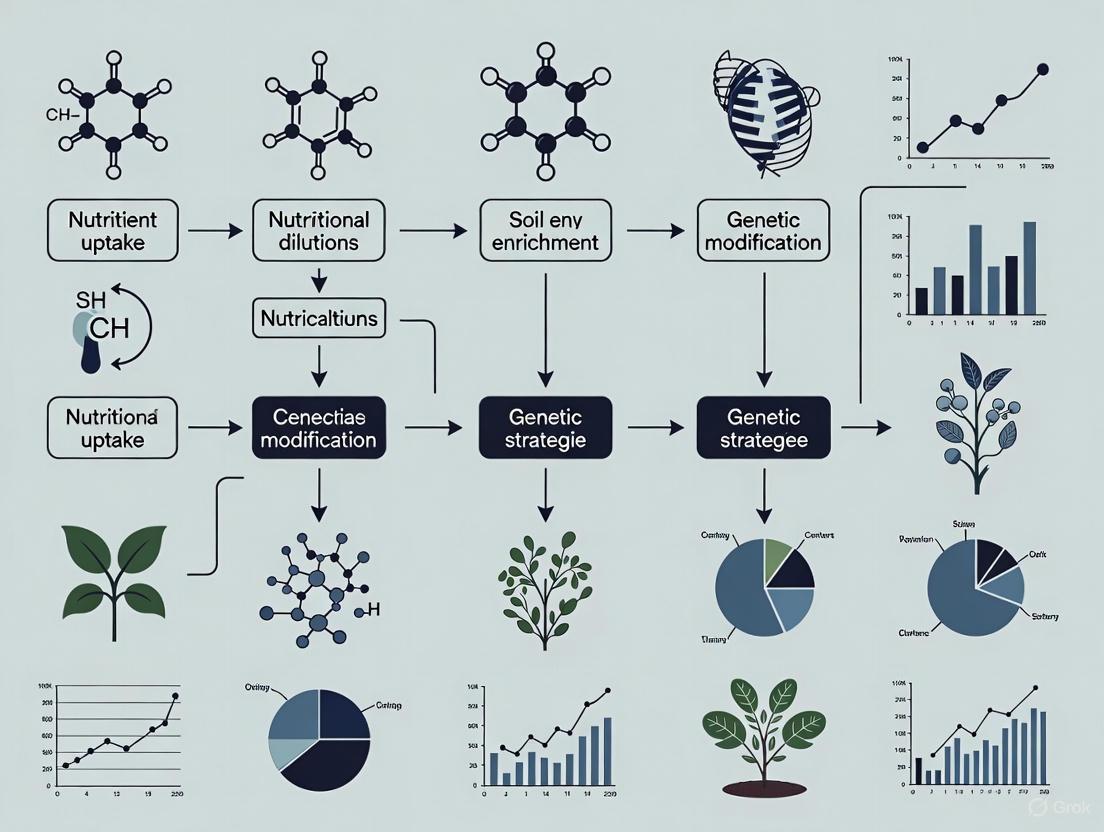

Research Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Nutritional Dilution Research

This diagram outlines a generalized workflow for conducting experiments aimed at mitigating nutritional dilution in crops.

Integrated Nutrient Management (INM) Concept

This diagram illustrates the components and benefits of an Integrated Nutrient Management strategy.

FAQs: Understanding the Problem

What is "nutrient dilution" in the context of food crops? Nutrient dilution, or Nutrient Dilution Food Quality, refers to the observed decline in the concentration of essential vitamins and minerals in many common food crops over the past several decades [2]. This phenomenon means that for the same amount of food, we are getting fewer nutrients than previous generations did.

What is the primary cause of mineral depletion in modern crops? The decline is attributed to a combination of factors, primarily modern agricultural practices that prioritize high yield volume over nutritional density [2] [3]. This includes chaotic mineral nutrient application, the use of high-yielding varieties that allocate nutrients differently, and agronomic issues associated with a shift from natural to chemical farming, which disrupts soil biological activity [3].

How significant is the decline in mineral content? Research shows a dramatic and alarming decline. The table below summarizes key findings on the reduction of mineral content in fruits and vegetables over various periods in the last century [3].

Table: Documented Declines in Mineral Content of Fruits and Vegetables

| Mineral | Time Period | Documented Decline | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca) | 1975-1997 | Up to 46% | Lemons (-57.4%), Pineapples (-58.8%), Tangerines (-65%) [3]. |

| Iron (Fe) | 1940-1991 | 24% to 50% | Bananas (-55.7%), Oranges (-75%), Watercress (-88.2%) [3]. |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 1936-1991 | 10% to 35% | Consistent decrease in vegetables and wheat [3] [4]. |

| Copper (Cu) | 1940-1991 | 49% to 81% | Dramatic absolute and relative reductions [3]. |

| Zinc (Zn) | 1978-1991 | 27% to 59% | Noted across a range of vegetable crops [3]. |

| Vitamin A | 1975-1997 | Up to 38% | Cauliflower (-68.3%), Broccoli (-38.3%) [3]. |

How does soil health directly impact the nutritional quality of a crop? Soil is not an inert growing medium but a vital living ecosystem [5]. Healthy soil, teeming with diverse microbes like bacteria and fungi, is the foundation for nutrient cycling. These organisms help break down organic matter and make minerals available for plant uptake. Degraded soil with low biological activity cannot effectively support this process, leading to plants with lower nutrient density [5] [6].

What are the key soil functions that support nutritious crops? According to the USDA NRCS, healthy soil performs five essential functions that are critical for producing nutrient-dense crops [5]:

- Cycling nutrients: Carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients are stored, transformed, and cycled.

- Sustaining plant and animal life: The diversity and productivity of living things depend on soil.

- Regulating water: Soil controls the flow and infiltration of water.

- Filtering and buffering potential pollutants: Minerals and microbes degrade and detoxify materials.

- Providing physical stability and support: Soil structure provides a medium for plant roots.

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: Diagnosing Soil Health and Nutrient Availability

This guide provides a methodology for assessing whether your experimental or field site has soil conditions that predispose crops to nutrient dilution.

Table: Soil Health Assessment Parameters and Methods

| Parameter to Assess | Signs of a Healthy System | Warning Signs of Degradation | Recommended Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Organic Matter | High levels; dark, crumbly structure. | Low levels; poor structure, compaction. | Loss-on-Ignition (LOI) Test: Measure soil weight loss after combustion at high temperatures to estimate organic matter content [5]. |

| Microbial Activity | Diverse and abundant microbial populations. | Low microbial biomass and diversity. | Soil Respiration Test: Measure CO2 flux from a soil sample as an indicator of microbial metabolic activity [5]. |

| Soil Structure & Infiltration | Stable aggregates, high water infiltration. | Crusting, compaction, high runoff. | Slake Test: Immerse an air-dried soil aggregate in water to observe its stability. Infiltration Ring Test: Measure the rate of water entry into the soil [5]. |

| Plant Nutrient Status | Optimal tissue concentrations of minerals. | Nutrient deficiency symptoms (e.g., chlorosis). | Plant Tissue Analysis: Laboratory analysis of specific crop tissues for nutrient concentrations to compare against established sufficiency ranges [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Soil Health Management Systems Objective: To quantify the effect of different soil management practices on soil health indicators and crop mineral density.

- Site Selection & Plot Design: Establish replicated plots in a uniform field.

- Treatment Application:

- Treatment A (Conventional): Tillage, synthetic fertilizers, monoculture.

- Treatment B (Regenerative): No-till, diverse cover crop mixes, compost application, diversified rotations [5].

- Soil Sampling: Collect soil samples from each plot at 0-15 cm depth at the beginning and end of the growing season. Analyze for soil organic matter, microbial biomass (e.g., via phospholipid fatty acid analysis), and available nutrient levels (e.g., Mehlich-3 or DTPA extraction).

- Plant Sampling: At harvest, collect crop samples from each plot. Prepare tissue samples for laboratory analysis of target minerals (e.g., Fe, Zn, Mg, Ca) using ICP-MS or similar techniques.

- Data Analysis: Perform ANOVA to determine if differences in soil parameters and crop mineral content between treatments are statistically significant.

The logical relationship between management practices, soil health, and crop nutrition is outlined below.

Guide 2: Addressing Nutrient Dilution in Experimental Crops

This guide provides actionable strategies for researchers to counter nutrient dilution in their agricultural studies.

Strategy 1: Enhance Soil Biological Activity

- Principle: Feed the soil microbiome to improve nutrient cycling [5].

- Protocol: Incorporate a multi-species cover crop mix (e.g., legumes, grasses, and brassicas) into the crop rotation. Terminate the cover crop and allow it to decompose as a green manure. Compare crop nutrient uptake and yield in these plots against fallow controls [5].

- Troubleshooting: If biomass is low, ensure adequate soil moisture during the cover crop growth period. Test different cover crop species mixtures to find the optimal combination for your soil type and climate.

Strategy 2: Utilize Cultivars with High Nutrient-Use Efficiency

- Principle: Genetic variation exists in the ability of crops to uptake and translocate minerals [3].

- Protocol: Screen different cultivars or landraces of the same crop under identical field conditions. Measure the concentration of target minerals in the edible parts. Select breeding lines that consistently show higher nutrient density without significant yield penalty [3].

- Troubleshooting: High nutrient density may be linked to smaller seed or fruit size. Focus breeding efforts on breaking this negative correlation.

Strategy 3: Re-mineralize Soils with Balanced Amendments

- Principle: Replenish the full spectrum of macro and micronutrients depleted by intensive farming [4].

- Protocol: Conduct a detailed soil test to identify specific mineral deficiencies. Apply soil amendments such as rock dust (for trace minerals), gypsum (for calcium and sulfur), or compost to address imbalances. Monitor soil test levels and plant tissue concentrations over multiple seasons.

- Troubleshooting: Be aware of nutrient antagonisms (e.g., high phosphorus can inhibit zinc uptake). Apply amendments based on soil test recommendations to avoid creating new imbalances.

The workflow for developing a nutrient-dense cropping system integrates these strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Reagents for Soil Health and Crop Nutrition Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) | High-sensitivity analytical instrument for precise quantification of multiple mineral elements (e.g., Fe, Zn, Se, Ca) in plant tissue and soil extracts [3]. |

| PLFA (Phospholipid Fatty Acid) Analysis | A biochemical technique used to profile the structure and mass of the soil microbial community, serving as an indicator of soil biological health [5]. |

| Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculant | Beneficial soil fungi that form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, significantly enhancing the plant's ability to forage for phosphorus and other immobile nutrients [6]. |

| Multi-Species Cover Crop Seed Mix | A living reagent used to maximize biodiversity. Legumes fix nitrogen, grasses build soil organic matter, and deep-rooted brassicas mine minerals from the subsoil [5]. |

| Soil Respiration Chambers | Portable field equipment used to measure CO2 flux from the soil surface, which is a direct indicator of microbial metabolic activity and soil organic matter decomposition [5]. |

| DTPA (Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) Extractant | A common chemical extractant used to simulate plant uptake and estimate the bioavailable fraction of micronutrients like zinc, iron, copper, and manganese in soil [7]. |

| Biochar | A carbon-rich soil amendment produced from pyrolyzed organic biomass. It can improve soil fertility, water retention, and microbial habitat, potentially increasing nutrient availability to plants [8]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: In my experiments with elevated CO₂, I am observing a decline in plant nutritional quality despite increased biomass. What are the primary biochemical mechanisms behind this, and how can I mitigate it in a research setting?

A1: The decline in nutritional quality, often termed "nutritional dilution," under elevated CO₂ is primarily driven by two key mechanisms:

- Carbohydrate Accumulation: Elevated CO₂ significantly enhances the net photosynthetic rate (Aₙₑₜ), leading to a greater production of carbohydrates (e.g., total soluble sugars and starch) [9]. This increase in carbon-rich compounds can dilute the concentration of other essential nutrients, such as proteins and minerals, in plant tissues [10].

- Reduced Nitrogen Assimilation: A critical factor is the down-regulation of photosynthetic capacity and the impairment of the carboxylation process often observed under high CO₂, which can be linked to a reduction in nitrogen uptake and assimilation [10] [11]. This results in a wider carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio in plant tissues [9]. Hormonal shifts, particularly a reduction in growth-promoting hormones like cytokinins which are vital for nitrogen metabolism, can further exacerbate this issue under combined stress [11].

Mitigation Strategies for Researchers:

- Nutrient Management: Implement a split-application of nitrogen fertilizers timed to coincide with peak crop demand. This helps ensure nitrogen availability matches the plant's enhanced growth under eCO₂, preventing dilution [12].

- Genotype Selection: Screen and select plant varieties that maintain robust nitrogen assimilation and photosynthetic machinery under eCO₂ conditions. For instance, some maize hybrids like DHM117 show better physiological recovery under combined eCO₂ and temperature stress, which can be linked to better resource allocation [9].

Q2: High night temperature (HNT) stress is causing significant yield loss in my grain crops. What are the specific physiological disruptions, and what experimental parameters should I monitor to identify tolerant lines?

A2: HNT stress primarily induces a carbon deficit and disrupts reproductive processes.

- Carbon Deficit: HNT increases dark respiration rates, leading to excessive consumption of photosynthetic products (carbohydrates) that were accumulated during the day. This results in a net loss of carbon reserves essential for growth and grain filling [11]. Monitoring non-structural carbohydrates (starch and sugars) in leaves and stems can quantify this loss.

- Reproductive Disruption: HNT during critical stages like grain number determination or anthesis silking interval (ASI) can cause spikelet sterility and reduce seed set [11] [9]. This is often linked to inhibition of pollen tube elongation and disruption of auxin homeostasis in pollinated pistils [11].

Key Experimental Parameters to Monitor:

- Phenology: Precisely record the Anthesis Silking Interval (ASI); a widening interval is a key indicator of heat stress in cereals like maize [9].

- Physiology: Measure leaf photosynthetic rate (Aₙₑₜ) and dark respiration rate throughout the growth cycle [11] [9].

- Stress Markers: Quantify biochemical stress markers like malondialdehyde (MDA) for lipid peroxidation and proline for osmotic adjustment. Elevated CO₂ has been shown to mitigate MDA accumulation under high temperature stress [9].

- Yield Components: Conduct detailed analyses of biomass allocation (root vs. shoot), grain yield, and harvest index [10] [9].

Q3: I am observing conflicting interactions between elevated CO₂ and elevated temperature in my C4 plant studies. How can I reconcile these responses in my experimental design and data interpretation?

A3: The interaction between elevated CO₂ (eCO₂) and elevated temperature (eT) is complex and can be antagonistic or synergistic, depending on the plant process being observed. Your experimental design should therefore treat them as independent variables.

- Ameliorating Effect: eCO₂ can partially mitigate the negative impacts of eT. For example, eT often impairs stomatal conductance and the carboxylation capacity of Rubisco, but eCO₂ can help revert this impact by improving water use efficiency and protecting photochemical processes [10] [9]. This is evident in the restoration of photosynthetic rates and reduction of oxidative damage markers like MDA [9].

- Non-Linear Interactions: In some cases, the combination of eT + eCO₂ can lead to unique outcomes not seen with either factor alone. For instance, one study on Dianthus inoxianus found that while eT alone hastened flowering and eCO₂ alone induced photosynthetic acclimation, the combination reduced both leaf-level assimilation and flower production [10].

Guidance for Experimental Design:

- Always include a full factorial design with four core treatments: Ambient CO₂ & Temperature, Ambient CO₂ & Elevated Temperature, Elevated CO₂ & Ambient Temperature, and Elevated CO₂ & Elevated Temperature.

- Focus interpretation on the significance of the interaction term in your statistical models, rather than just main effects. This allows you to formally test whether the effect of temperature depends on the CO₂ level, and vice versa.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: High variability in plant physiological responses to controlled climate treatments.

- Solution: Ensure rigorous monitoring of chamber conditions. Use soil and plant tissue testing to track nutrient status throughout the experiment, as pre-existing nutrient levels can dramatically influence results [12]. For HNT studies, maintain precise control over the entire 24-hour diurnal cycle, as even short-term fluctuations can trigger respiratory bursts [11].

Challenge: Differentiating between heat avoidance and heat tolerance mechanisms in phenotyping.

- Solution: A plant may complete its life cycle early (avoidance) rather than truly tolerating the stress. To differentiate, measure a suite of traits:

- For Avoidance: Track phenology (days to flowering) and biomass allocation (e.g., increased root-to-shoot ratio) [10].

- For Tolerance: Measure real-time physiological performance (photosynthesis, stomatal conductance) and cellular integrity (membrane stability via electrolyte leakage, MDA content) under sustained stress [13] [9].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Biochemical and Yield Responses to Elevated CO₂ and Temperature

| Stress Factor | Impact on Photosynthesis | Impact on Respiration | Key Biochemical Changes | Typical Impact on Yield | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated CO₂ (eCO₂) | Increases net photosynthesis (Aₙₑₜ) in C3 plants; can lead to acclimation in some species. | Can be variable; may increase with greater biomass. | ↑ Total Soluble Sugars, ↑ Starch, Wider C/N ratio, ↓ Specific Nitrogen Content | Increase in C3 crops (up to 18-41%); modest increase (5-10%) in C4 crops. | [10] [9] |

| Elevated Temperature (eT) | Impairs photosynthesis; damages PSII, disrupts thylakoid membranes. | Significant increase in dark respiration, especially at night. | ↑ Proline, ↑ MDA (oxidative stress), ↓ Total phenolics, Altered hormone balance (↓ Cytokinins, ↑ ABA) | Decrease; e.g., maize yield reduced by ~8% per 2°C rise. | [13] [11] [9] |

| High Night Temperature (HNT) | Inhibits carbon fixation capacity via accelerated senescence. | Markedly increases, causing carbon deficit. | Depletion of non-structural carbohydrates, Accumulation of stress-protective amino acids. | Significant loss due to reduced grain set and size. | [11] |

| eCO₂ + eT | Can mitigate the negative impact of eT on photosynthesis to some extent. | Interaction effect is complex and species-specific. | eCO₂ can ameliorate eT-induced proline and MDA increases. | eCO₂ can partially offset eT-induced yield losses. | [9] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Stress Physiology Studies

| Research Reagent / Kit | Primary Function in Experiment | Example Application in Climate Stress Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Li-Cor Photosynthesis System | Measures leaf gas exchange parameters (Aₙₑₜ, gₛ, Cᵢ). | Quantifying photosynthetic acclimation to eCO₂ and impairment by eT. |

| Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imager | Assesses PSII efficiency (Fᵥ/Fₘ), photoinhibition, and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ). | Evaluating heat damage to photosynthetic apparatus and photoprotective capacity. |

| MDA (Malondialdehyde) Assay Kit | Quantifies lipid peroxidation, a key marker of oxidative stress. | Measuring the severity of membrane damage under HNT and the mitigating effect of eCO₂. |

| Proline Assay Kit | Measures proline accumulation, involved in osmotic adjustment and stress protection. | Assessing osmotic stress response in plants under combined eT and water deficit. |

| ELISA for Phytohormones | Quantifies levels of hormones (ABA, Salicylic Acid, Cytokinins). | Profiling hormonal shifts (e.g., drop in cytokinins) under HNT stress. |

| Soil & Plant Tissue Testing Kits | Determines nutrient content (N, P, K) in soil and plant tissue. | Monitoring nutrient uptake and C/N ratio to study nutritional dilution under eCO₂. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Quantifying Oxidative Stress via Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content

- Principle: MDA, a product of lipid peroxidation, reacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to form a colored complex that can be quantified spectrophotometrically.

- Procedure:

- Homogenize 0.5 g of fresh leaf tissue in 5 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) on ice.

- Centrifuge the homogenate at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer 1 mL of the supernatant to a new tube and add 4 mL of a solution containing 20% TCA and 0.5% TBA.

- Incubate the mixture in a boiling water bath for 30 minutes, then quickly cool on ice.

- Centrifuge again to clarify and measure the absorbance of the supernatant at 532 nm and 600 nm (for background correction).

- Calculate MDA concentration using its extinction coefficient (155 mM⁻¹cm⁻¹) [9].

Protocol 2: Assessing Photosynthetic Acclimation via CO₂ Response Curves (A/Cᵢ)

- Principle: A/Cᵢ curves describe the relationship between net CO₂ assimilation rate (A) and intercellular CO₂ concentration (Cᵢ), allowing for the determination of key photosynthetic parameters like maximum carboxylation capacity (Vcₘₐₓ) and maximum electron transport rate (Jₘₐₓ).

- Procedure:

- Using an infrared gas analyzer (IRGA) system, stabilize a attached leaf under controlled light and temperature conditions.

- Measure Aₙₑₜ at a series of decreasing CO₂ concentrations (e.g., from 400 ppm down to 50 ppm) to capture the Rubisco-limited region.

- Subsequently, measure Aₙₑₜ at a series of increasing CO₂ concentrations (e.g., from 400 ppm up to 1500 ppm) to capture the RuBP regeneration-limited region.

- Fit the data to a biochemical model of photosynthesis (e.g., the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry model) to extract Vcₘₐₓ and Jₘₐₓ. A decline in these parameters under long-term eCO₂ exposure indicates photosynthetic acclimation [10].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Plant Stress Signaling Pathways

Experimental Stress Phenotyping Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers and scientists in diagnosing and resolving common experimental challenges related to nutritional dilution in agricultural research. Nutritional dilution—the decline in nutrient concentration in crops despite increased yield—presents a significant challenge for balancing agricultural productivity with nutritional security [3] [14].

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary drivers of nutritional dilution in modern cropping systems? Research indicates that the decline in nutritional quality is multifactorial. Key drivers include: soil degradation from chaotic mineral nutrient application, preference for high-yielding varieties over nutrient-dense cultivars, depletion of soil organic matter, and the shift from natural to chemical farming systems. Elevated atmospheric CO₂ levels have also been shown to extensively reduce nutritional quality, particularly in fruits, vegetables, and staple crops [3].

How significant is the documented decline in nutrient density? The decline is substantial and well-documented across multiple crop types and geographical regions. The following table summarizes key reductions observed in various studies:

Table 1: Documented Nutrient Declines in Crops Over Recent Decades

| Time Period | Crop/Group | Nutrient Reductions Documented | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940–2019 [3] | Mixed Vegetables | Multiple Minerals | 52% decline in sodium, 50% in iron, 49% in copper, 10% in magnesium. |

| 1963–1992 [3] | 13 US Fruits & Vegetables | Minerals | 29% decline in calcium, 21% in magnesium, 32% in iron. |

| 1975–1997 [15] | Broccoli | Vitamins & Minerals | 56% decline in calcium, 38.3% in Vitamin A, 17.5% in Vitamin C, 20% in iron. |

| 1936–1987 [3] | 20 UK Fruits & Vegetables | Minerals | 19% decline in calcium, 35% in magnesium, 81% in copper. |

What agricultural practices show promise for mitigating nutrient dilution while maintaining yield? Empirical evidence points to moderate-investment practices that emphasize targeted and efficient input application. These strategies can achieve yields comparable to high-investment (input-intensive) practices while significantly reducing environmental costs by approximately $135 per hectare and increasing profits by $23 per hectare [16]. Furthermore, specific interventions like organic amendments, deficit irrigation, and foliar application of amino acids or minerals have been shown to enhance antioxidant content and reduce heavy metal uptake in contaminated soils [17].

Are there trade-offs between increasing crop production and other ecosystem services? Yes, significant trade-offs exist. Research from the Loess Plateau of China demonstrates clear tensions between provisioning services (crop yield) and regulating/supporting services like water yield, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity. Sustainable intensification scenarios that increase agricultural production must be carefully managed to avoid negative impacts on these critical ecosystem functions [18].

Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Challenge: Inconsistent nutrient density outcomes in biofortification trials.

- Problem Identification: Biofortification efforts successfully increase target minerals (e.g., zinc, iron, selenium) in grains but inadvertently cause reductions in other beneficial compounds.

- Possible Explanations:

- Nutrient Antagonism: Competition between minerals during plant uptake (e.g., phosphorus-zinc interaction) [17].

- Biochemical Trade-offs: Resource allocation within the plant may shift from secondary metabolites (e.g., antioxidants) to the targeted nutrient.

- Diagnostic Experimentation:

- Implement targeted soil testing to identify pre-existing nutrient imbalances.

- Design experiments that measure a comprehensive panel of nutrients and phytochemicals, not just the target mineral.

- Compare foliar application (which can bypass soil antagonisms) with soil amendment strategies [17].

- Solution: Employ balanced fertilization strategies based on comprehensive soil testing. Consider combined approaches, such as integrating soil amendments with foliar feeding at critical growth stages to mitigate antagonistic effects.

Challenge: Yield reductions when implementing quality-enhancing practices.

- Problem Identification: Transition to practices that improve soil health and nutrient density (e.g., organic amendments, reduced chemical inputs) results in unacceptable yield loss.

- Possible Explanations:

- Transition Period Lag: Soil microbiome and organic matter require time to rebuild ecosystem functions that support yield [3].

- Insufficient Nutrient Availability: Rapid release of soluble nutrients is reduced, creating a temporary deficit.

- Diagnostic Experimentation:

- Conduct phased implementation, converting only portions of experimental plots to track recovery timelines.

- Monitor key soil health indicators (organic matter, microbial biomass) alongside yield and quality metrics.

- Test "moderate-investment" combinations, such as reduced synthetic inputs with complementary organic amendments [16].

- Solution: Implement a graduated transition strategy over multiple growing seasons. Use integrated nutrient management that combines quick-release fertilizers at critical growth stages with slow-release organic sources to build long-term soil health without sacrificing yield during the transition.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Moderate-Investment Agricultural Practices

Background: This methodology assesses farming strategies that balance input application to optimize both productivity and nutritional quality, thereby mitigating nutritional dilution and environmental impact [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Field Trials

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Soil Testing Kit | Pre-experiment analysis of NPK, pH, and organic matter to establish baseline soil fertility. |

| Precision Fertilizer Applicator | Enables targeted and efficient input application as per moderate-investment protocol. |

| Leaf Tissue Sampling Kits | For collecting plant samples at multiple growth stages for nutrient density analysis. |

| Environmental Cost Calculation Matrix | Standardized framework for quantifying externalities ($/hectare) of different practices. |

Procedure:

- Site Selection & Characterization: Select uniform field plots and conduct a comprehensive soil census to characterize chemical and physical properties.

- Treatment Establishment: Implement three distinct management regimes:

- High-Investment: Characterized by intensive, conventional chemical application.

- Moderate-Investment: Defined by targeted, efficient input use based on soil test recommendations.

- Low-Investment: Applies inputs minimally or organically.

- Data Collection:

- Agronomic Data: Record yields at harvest for all treatments.

- Nutritional Analysis: Collect edible portions and analyze for target micronutrients, proteins, and antioxidant compounds.

- Economic & Environmental Metrics: Document input costs, calculate profits, and quantify environmental costs (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution).

- Data Analysis: Perform trade-off analysis comparing yield, nutritional density, profitability, and environmental costs across the three management strategies.

Protocol 2: Assessing Trade-offs Between Production and Ecosystem Services

Background: This integrated framework quantifies the trade-offs between agricultural production (a provisioning service) and other key ecosystem services, which is critical for developing sustainable intensification strategies that do not undermine environmental health [18].

Procedure:

- Scenario Definition: Model and/or establish field plots representing different land management scenarios: Business-as-Usual, Ecological Restoration, and Sustainable Intensification.

- Biophysical Modeling & Field Measurement:

- Use models like InVEST and RUSLE to quantify ecosystem services (water yield, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, habitat quality).

- Collect field data on crop yields and net primary productivity (NPP) to measure provisioning services.

- Indicator Integration: Employ a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) or similar framework to integrate the quantified indicators and visualize the trade-offs and synergies between agricultural production and other ecosystem services.

- Strategy Formulation: Based on the analysis, identify management practices within the Sustainable Intensification scenario that provide the best balance between productivity and environmental sustainability.

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Nutritional Dilution Research. This resource is designed to support researchers and scientists in quantifying and addressing the decline of essential nutrients in staple crops, a phenomenon often referred to as "nutritional dilution." The following guides and FAQs provide structured data, experimental protocols, and key reagents to advance your research in this critical field.

★ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the historical evidence for nutrient decline in crops? Extensive research over the last half-century to eighty years has documented a significant decline in the nutrient density of fruits, vegetables, and staple crops. The most pronounced depletion has occurred over the last 30-40 years. The table below summarizes key findings from long-term studies [3].

Table 1: Documented Nutrient Declines in Fruits and Vegetables Over the 20th Century

| Nutrient | Documented Decline (%) | Time Period | Crops Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 49% - 81% | 1940 to 2019 | Mixed Vegetables & Fruits |

| Iron | 22% - 50% | 1936 - 1991 | Mixed Vegetables & Fruits |

| Sodium | 29% - 52% | 1940 to 2019 | Mixed Vegetables & Fruits |

| Calcium | 16% - 46% | 1936 - 1987 | Mixed Vegetables & Fruits |

| Magnesium | 10% - 35% | 1936 - 1991 | Mixed Vegetables & Fruits |

| Vitamin A | 18% (average) | Past 50 years | 43 Fruits & Vegetables |

| Riboflavin | 38% (average) | Past 50 years | 43 Fruits & Vegetables |

FAQ 2: How does rising atmospheric CO₂ specifically affect crop nutrition? Rising CO₂ levels induce a "carbon dilution effect," where plants accumulate more carbohydrates but have reduced concentrations of proteins and essential micronutrients. This is not just a theoretical model; it has been empirically demonstrated in Open-Top Chamber (OTC) and Free-Air CO₂ Enrichment (FACE) experiments, which simulate future atmospheric conditions [19] [20] [21]. The impact varies by crop and nutrient, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Nutrient Reduction in Staple Crops Under Elevated CO₂ Conditions

| Staple Crop | Protein Reduction | Iron (Fe) Reduction | Zinc (Zn) Reduction | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Staples (Wheat, Rice, etc.) | Nearly 10% (average) | Up to 16% (average) | Up to 9% (average) | Meta-analysis of FACE/OTC studies [20] |

| Rice | 6% - 10% (projected) | 3% - 11% (projected) | 3% - 11% (projected) | FACE experiments, CO₂ ~550 ppm [19] |

| Leafy Greens (e.g., Spinach) | Significant reduction observed | Reduction in Calcium & Antioxidants | Not Specified | Growth chamber simulation of UK future climate [22] |

FAQ 3: What are the projected global health impacts of this nutrient decline? By 2050, it is projected that hundreds of millions more people could slip below minimum thresholds for essential nutrients. This will exacerbate existing health inequities, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations in low-income countries [21].

- Zinc Deficiency: An extra 175 million people could become deficient, increasing vulnerability to malaria, diarrheal diseases, and impaired immune function [21].

- Protein Deficiency: 122 million people could become protein deficient, leading to increased infant mortality and stunted growth [21].

- Iron Deficiency: 1.4 billion women and children under 5 could see their iron intake drop by 4% or more, raising the risk of anemia and cognitive impairment [21].

★ Troubleshooting Guide: Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Free-Air CO₂ Enrichment (FACE) for Nutrient Impact Studies

Issue: How to experimentally simulate the effect of future CO₂ levels on crop nutrition in a real-world, open-field setting, avoiding the limitations of greenhouse or growth chamber studies.

Solution: The FACE system uses a ring of jets to precisely control and elevate CO₂ concentrations over an open field, allowing plants to be grown in natural conditions while exposed to target CO₂ levels [20] [21].

Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 1: FACE experimental workflow.

Detailed Methodology:

- Site Selection & Baseline Analysis: Select a representative agricultural field. Analyze initial soil chemistry, nutrient content, and microbial activity to establish a baseline [1].

- Install FACE Infrastructure: Erect a ring of CO₂ jets and sensors around the experimental plot. A control plot with identical infrastructure but ambient CO₂ is essential.

- CO₂ Treatment Application: Program the system to release CO₂ to maintain a predetermined elevated concentration (e.g., 550 ppm, 690 ppm). Sensors provide real-time feedback for precise control [20].

- Crop Growth & Monitoring: Grow test crops (e.g., rice, wheat, leafy greens). Monitor photosynthetic markers (e.g., chlorophyll fluorescence, quantum yield), growth rates, and biomass throughout the season [22].

- Harvest & Sample Collection: At maturity, harvest crops from both treatment and control plots. Record yield and biomass. Prepare samples for biochemical analysis.

- Nutritional Quality Analysis: This is the core analytical phase. Use the following techniques:

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): To measure concentrations of sugars, proteins, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and vitamins [22].

- X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Profiling: To quantify mineral content (e.g., Iron, Zinc, Calcium, Potassium) [22].

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): For highly sensitive multi-elemental analysis of micronutrients and heavy metals.

- Data Synthesis: Statistically compare the nutritional profiles of crops grown under elevated CO₂ versus ambient conditions to quantify the dilution effect.

Protocol 2: Genomic-Assisted Breeding for Biofortification

Issue: How to develop new crop varieties with enhanced nutritional content to counteract nutrient dilution.

Solution: Leverage molecular markers and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping to identify and introgress genes associated with high nutrient density into elite breeding lines [23].

Breeding Workflow:

Diagram 2: Biofortification breeding workflow.

Detailed Methodology:

- Germplasm Screening: Screen diverse germplasm, including wild relatives, landraces, and local cultivars, to identify accessions with naturally high levels of target nutrients (e.g., high zinc, iron, or pro-vitamin A) [23].

- Genetic Analysis & QTL Mapping:

- Cross a high-nutrient donor parent with a high-yielding, adapted elite line to create a mapping population (e.g., Recombinant Inbred Lines - RILs).

- Phenotype the population for nutritional traits.

- Genotype the population using molecular markers (e.g., SNPs, DArT).

- Perform QTL analysis to identify genomic regions significantly associated with the nutritional traits. Examples: QTLs for grain protein content (Gpc) in wheat on chromosomes 1B and 4B; QTLs for pro-vitamin A (crtRB1) in maize on chromosome 10 [23].

- Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS): Develop DNA markers tightly linked to the identified QTLs. Use these markers to screen breeding material and select individuals that carry the desirable nutrient-rich genomic regions.

- Development of Biofortified Lines: Backcross the selected individuals with the elite parent to recover the agronomic background while retaining the high-nutrient QTLs.

- Nutritional Validation: Confirm the enhanced nutritional content of the new biofortified lines using HPLC, XRF, or ICP-MS to ensure the successful introgression of the traits.

★ The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Nutritional Dilution Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Free-Air CO₂ Enrichment (FACE) Systems | In-situ exposure of crops to elevated atmospheric CO₂ in open-field conditions. | Gold standard for realism; requires significant infrastructure and funding [20] [21]. |

| Open-Top Chambers (OTCs) | Controlled exposure to elevated CO₂ and temperature for smaller-scale field studies. | More affordable than FACE but creates a semi-closed environment [19]. |

| Molecular Markers (SNPs, SSRs) | Genotyping for QTL mapping and Marker-Assisted Selection in biofortification programs. | Critical for tracking nutrient-related genes (e.g., crtRB1 for pro-vitamin A) without complex phenotyping [23]. |

| HPLC Systems | Separation and quantification of proteins, vitamins, sugars, and antioxidant compounds. | Essential for detailed biochemical profiling of crop quality [22]. |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Analyzer | High-throughput, non-destructive measurement of elemental composition (e.g., Zn, Fe, K). | Ideal for rapid screening of mineral content in large numbers of samples [22]. |

| Controlled-Release Fertilizers | Slow nutrient release to match crop uptake, improving Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE). | Reduces nutrient leaching and can mitigate antagonisms that cause dilution [1]. |

| Biofertilizers / Biostimulants | Microbial inoculants that enhance nutrient solubilization and uptake from soil. | Improves plant access to soil minerals, potentially increasing nutrient density [1]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Genome editing for precise enhancement of nutrient pathways in crops. | Emerging tool for directly editing genes responsible for nutrient accumulation [23]. |

Building Nutrient Resilience: Practical Agronomic and Genetic Tools

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: How can I differentiate between nitrogen deficiency caused by soil health issues versus simple under-fertilization in a no-till system?

Answer: This is a common diagnostic challenge. In a no-till system with cover crops, nitrogen deficiency symptoms (like chlorosis) may not indicate simple fertilizer shortage but rather a temporary nitrogen immobilization caused by high carbon residues. To diagnose:

- Test the Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C:N) Ratio: Analyze the C:N ratio of your cover crop residue or soil organic amendments. Residue with a C:N ratio wider than 30:1 (e.g., mature cereal rye) can tie up nitrogen, while residue with a C:N ratio narrower than 20:1 (e.g., hairy vetch) mineralizes nitrogen quickly [24].

- Conduct a Soil Incubation Test: Incubate a soil sample under controlled conditions and measure mineral nitrogen release over 2-4 weeks. This distinguishes between total nitrogen and plant-available nitrogen.

- Check for Surface Banding: In no-till systems, nitrogen can be stratified in the top few centimeters. Sample soil at different depths (0-5 cm, 5-15 cm, 15-30 cm) to assess nutrient distribution.

- Solution: If immobilization is the issue, consider switching to a cover crop mix that includes legumes (e.g., clover, vetch) to balance the C:N ratio, or adjust the timing of cover crop termination to allow for partial decomposition before planting the cash crop [25].

FAQ 2: My cover crops are failing to establish adequately, leading to poor weed suppression and soil cover. What are the potential causes?

Answer: Poor establishment undermines the core goals of cover cropping. The issue often lies in seeding methodology or species selection.

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Seed-to-Soil Contact. In no-till systems, simply broadcasting seed onto compacted residue may fail.

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect Seeding Rate or Timing.

- Solution: Follow species-specific guidelines. For example, cereal rye should be seeded at 60-120 lbs/acre, while hairy vetch is seeded at 20-40 lbs/acre. Planting too late in the fall does not allow seedlings to establish sufficiently before frost [25].

- Potential Cause 3: Inappropriate Species for Your Climate or Soil.

- Solution: Select cold-hardy species for winter cover (e.g., winter rye, crimson clover) and heat-tolerant species for summer (e.g., sorghum-sudan grass, cowpeas). Using diverse mixes improves the odds of success [25].

FAQ 3: In a field experiment, how do I quantitatively attribute improvements in crop nutritional density directly to a specific soil health practice?

Answer: Isolating the effect of a single practice requires a carefully controlled experimental design and specific metrics.

- Establish Baselines: Pre-treatment, measure baseline soil health indicators (SOC, microbial biomass, aggregate stability) and the nutrient density (minerals, vitamins) of your crop of interest [3].

- Implement Controlled Treatments: Use replicated plots with treatments such as:

- Treatment A: Conventional tillage + inorganic fertilizer (control).

- Treatment B: No-till + inorganic fertilizer.

- Treatment C: No-till + cover crops + inorganic fertilizer.

- Treatment D: No-till + cover crops + organic amendments (e.g., biochar, compost) [27].

- Track Correlation and Causation: Use regression analysis to correlate changes in specific soil health parameters (e.g., percent increase in SOC, microbial activity) with changes in the concentration of target nutrients in the crop (e.g., iron, zinc, vitamin C). This helps move beyond simple correlation to a stronger causal inference [1] [3].

Quantitative Data on Strategy Efficacy

Table 1: Impact of Integrated Strategies on Soil Health and Crop Outcomes

| Strategy | Key Metric | Result | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Till + Cover Crop + Biochar | Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) Stock | Increased in top 0-30 cm profile | Randomized complete block study on Andosol; Japan | [27] |

| No-Till + Cover Crop + Biochar | Soil Bulk Density & Penetration Resistance | Reduced, improving soil structure | Randomized complete block study on Andosol; Japan | [27] |

| Integrated Nutrient Management (INM) | Crop Yield | 8% to 150% increase vs. conventional | Systematic review of 65 peer-reviewed studies | [1] |

| 75% NPK + Farmyard Manure + Bioinoculants | Productivity & Soil Health | High productivity achieved while reducing chemical fertilizer reliance | Field and greenhouse experiments | [1] |

| Cover Crop Mix (Turnips, Cowpeas, Lentils) | Subsequent Corn Yield | Increased by 18-20 bushels per acre | On-farm trials, South Dakota | [26] |

Table 2: Documented Decline in Food Nutrient Density (Context for Research Urgency)

| Food Category | Nutrient | Documented Decline | Time Period | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits & Vegetables | Iron | Up to 50% | 1940-2019 | [3] |

| Fruits & Vegetables | Copper | Up to 49% | 1940-2019 | [3] |

| Vegetables (20 varieties) | Calcium | 19% | 1936-1991 | [3] |

| Vegetables (20 varieties) | Magnesium | 35% | 1936-1991 | [3] |

| 43 Fruits & Vegetables | Protein | 6% | ~50 years | [3] |

| 43 Fruits & Vegetables | Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | 38% | ~50 years | [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a No-Till System with Cover Crops for Nutrient Density Research

Objective: To transition from conventional tillage to a no-till system integrated with cover crops and measure the impact on soil health parameters and crop nutrient density.

Materials: No-till drill, roller-crimper or mower, cover crop seeds, soil corer, soil test kits, plant tissue sampling equipment.

Methodology:

- Site Selection & Baseline Sampling: Select a uniform field area. Collect composite soil samples (0-15 cm and 15-30 cm depths) for standard nutrient analysis, SOC, and microbial biomass carbon. Harvest the current cash crop and analyze its nutrient content.

- Cover Crop Establishment:

- Timing: Plant immediately after harvest of the main crop.

- Species Selection: Use a diverse mix. A standard mix for cool seasons could be cereal rye (biomass producer), hairy vetch (N-fixer), and forage radish (for compaction breakup) [25].

- Planting: Use a no-till drill to plant the cover crop mix into the crop residue. Ensure good seed-to-soil contact [26].

- Cover Crop Termination:

- Timing: Terminate at full flowering (anthesis) for cereals or at mid-bloom for legumes. This is when the plants are easiest to kill and have accumulated maximum biomass [25].

- Method: Use a roller-crimper or mower to terminate the cover crop, creating a thick mulch layer on the soil surface.

- Cash Crop Planting: Plant the cash crop (e.g., soybeans, corn) directly into the cover crop residue using a no-till planter.

- Data Collection: Monitor soil moisture, temperature, and weed pressure. At cash crop harvest, collect yield data and tissue samples for detailed nutrient analysis. Repeat soil sampling annually to track changes in SOC and other health indicators.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Organic Amendments on Nutrient Availability

Objective: To assess the effect of biochar and compost on soil nutrient cycling, microbial activity, and subsequent crop nutrient density.

Materials: Biochar, compost, plot markers, soil moisture and temperature sensors, equipment for measuring soil respiration.

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Set up a randomized complete block design with treatments like: a) Control (inorganic fertilizer only), b) Inorganic fertilizer + Compost, c) Inorganic fertilizer + Biochar, d) Inorganic fertilizer + Compost + Biochar [27].

- Amendment Application: Source standardized, well-characterized biochar and compost. Apply amendments uniformly to plots according to treatment specifications and incorporate lightly into the topsoil (unless in a strict no-till system, where it would be surface-applied).

- Monitoring: Regularly measure:

- Soil Physico-chemical Properties: SOC, pH, CEC, bulk density.

- Biological Activity: Soil respiration (CO2 flux), microbial biomass carbon/nitrogen.

- Nutrient Availability: In-season soil nitrate and ammonium tests.

- Plant Analysis: At key growth stages (e.g., flowering) and at harvest, collect plant tissue to analyze for macro- and micronutrients. Compare the results across treatments to identify amendments that enhance nutrient uptake and reduce dilution effects.

Conceptual Workflow and Pathways

Soil Health Pathway to Reduce Nutritional Dilution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Soil Health Research

| Item | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| No-Till Drill | Plants seeds directly into previous crop residue with minimal soil disturbance. | Critical for maintaining the integrity of no-till experimental plots. Ensures good seed-to-soil contact. |

| Roller-Crimper | Mechanically terminates cover crops by crushing stems without cutting. | Creates a uniform mulch layer that suppresses weeds and conserves moisture. |

| Biochar | Stable carbon-rich soil amendment. Improves water and nutrient retention, provides microbial habitat. | Source and production temperature (pyrolysis) significantly impact its properties. Characterize before use [27]. |

| Legume Cover Crop Seeds (e.g., Hairy Vetch, Clover) | Biological nitrogen fixation; reduces need for synthetic N fertilizers. | Inoculate seeds with appropriate Rhizobium strains to ensure effective nodulation and N-fixation [25]. |

| Grass Cover Crop Seeds (e.g., Cereal Rye, Oats) | Produces high biomass, scavenges residual soil nitrogen, prevents leaching. | High C:N ratio can immobilize N if not managed correctly. Terminate at flowering [24] [25]. |

| Soil Cores & Microbial Biomass Kits | For collecting undisturbed soil samples and quantifying active soil microbial population. | Essential for measuring changes in Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) and biological activity over time. |

| Plant Tissue Testing Kits | For precise quantification of micronutrients and macronutrients in harvested crops. | Used to directly measure the outcome variable—nutritional density—against experimental treatments. |

FAQs: Core Concepts of Integrated Nutrient Management

What is the primary goal of INM in modern agricultural research? The primary goal of INM is to develop sustainable nutrient management strategies that synergistically combine organic and inorganic sources. This approach aims to maintain high crop productivity, improve soil health, enhance nutrient use efficiency, and reduce environmental impacts, thereby addressing issues like soil degradation and nutritional dilution in food systems [1] [28].

How does INM help in reducing nutritional dilution in crops? Nutritional dilution occurs when crop yields are prioritized at the expense of nutrient density. INM combats this by fostering a balanced soil ecosystem. Integrated application of chemical fertilizers with organic amendments like farmyard manure (FYM) and bio-inoculants has been shown to significantly improve nutrient concentrations (N, P, K, Zn, Fe) and their uptake in plants, ensuring that high yields do not come at the cost of nutritional quality [29] [1].

What are the common challenges researchers face when designing long-term INM experiments? Key challenges include selecting appropriate treatment combinations, managing the logistics of long-term field experiments, and accurately measuring soil health indicators. Best practices recommend a minimum of 3-4 biological replicates to account for variability and ensure statistical robustness [30]. Long-term studies, such as those spanning over 30 years, are crucial to understanding the cumulative benefits of INM on soil ecosystem services [28].

Troubleshooting Common INM Experimental Issues

Issue: Inconsistent crop yield responses to INM treatments.

Solution: Ensure the balanced integration of nutrient sources. A study on a maize-berseem-cowpea system found that the most effective treatment (T7) combined 100% recommended nitrogen through FYM, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), and a 3% foliar spray of Panchagavya. This combination significantly improved green fodder yields over three consecutive years [29]. In a rice-rice system, the combination of recommended chemical fertilizers with FYM or Azolla led to enhanced soil health and sustained yields [28]. Verify that your treatment design includes complementary inputs to meet both immediate and long-term crop nutrient demands.

Issue: Unclear or minimal improvements in soil health parameters. Solution: Focus on measuring sensitive biological indicators. Research shows that long-term INM practices significantly alter soil microbiological properties. For instance:

- Treatment

RDF + Azollaresulted in the highest bacterial count and dehydrogenase activity. - Treatment

RDF + FYMled to the highest fungal count and phosphomonoeasterase activity [28]. If improvements are not observed, consider the application rates and quality of your organic amendments, and allow sufficient time for these inputs to influence the soil ecosystem.

Issue: Low Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) persists in the system. Solution: Integrate precision agriculture technologies and advanced fertilizer formulations. Strategies include:

- Adopting the 4Rs of nutrient stewardship (right source, rate, time, and place) [1].

- Using slow- and controlled-release fertilizers to minimize losses [1].

- Implementing site-specific nutrient management (SSNM) to tailor applications to field variability [1]. These approaches can significantly enhance NUE, reduce nutrient losses, and improve the overall effectiveness of your INM strategy.

Quantitative Data from INM Studies

Table 1: Crop Yield Response to INM in a Maize-Berseem-Cowpea System (2018-2021) [29]

| Treatment Description | Crop | Green Fodder Yield (t ha⁻¹) 2018-19 | Green Fodder Yield (t ha⁻¹) 2019-20 | Green Fodder Yield (t ha⁻¹) 2020-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% RDN via FYM + PGPR + Panchagavya (T7) | Maize | 35.4 | 37.0 | 38.6 |

| 100% RDN via FYM + PGPR + Panchagavya (T7) | Berseem | 58.2 | 60.0 | 60.6 |

| 100% RDN via FYM + PGPR + Panchagavya (T7) | Cowpea | 25.7 | 27.5 | 28.3 |

Table 2: Soil Biological Properties under Long-Term INM in a Rice-Rice System (32 years) [28]

| Treatment | Microbial Biomass Carbon (µg g⁻¹) | Bacterial Count (log cfu g⁻¹) | Fungal Count (log cfu g⁻¹) | Dehydrogenase Activity (µg TTF g⁻¹ 24 h⁻¹) | Phosphomonoeasterase Activity (µg p-nitrophenol g⁻¹ h⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDF + Azolla | 412.1 | 8.95 | 7.18 | 223.6 | 295.2 |

| RDF + FYM | 392.4 | 8.45 | 7.47 | 191.5 | 337.4 |

| Control (No nutrients) | 129.4 | 7.12 | 6.21 | 52.1 | 152.6 |

RDF: Recommended Dose of Fertilizers; FYM: Farmyard Manure

Experimental Protocols for INM Research

Protocol 1: Field Evaluation of INM in a Sequential Cropping System

This methodology is adapted from a three-year field study on a maize-berseem-cowpea fodder system [29].

1. Experimental Design and Setup:

- Site Selection: Choose a representative site with known soil history. Initial soil analysis is critical for establishing baseline fertility (e.g., pH, organic carbon, available N, P, K).

- Design: Employ a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with a minimum of 3-4 replications to account for field variability [30].

- Treatment Structure: Include 7 or more treatments to compare:

- T1: 100% recommended NPK via inorganic fertilizers (control).

- T2: 100% RDN through FYM.

- T3-T6: Combinations of 50-75% RDN through FYM + remaining N through fertilizers.

- T7: 100% RDN through FYM + PGPR seed treatment + 3% foliar spray of Panchagavya.

2. Treatment Application:

- Inorganic Fertilizers: Apply as per treatment specification, with N splits for maize (half at sowing, half 30 DAS) and full dose at sowing for berseem and cowpea. Apply P and K as basal doses.

- Organic Amendments (FYM): Apply as a basal dose during field preparation, calculated based on its nitrogen content.

- Bio-inoculants (PGPR): Treat seeds with PGPR as per manufacturer's instructions before sowing.

- Panchagavya: Apply as a 3% foliar spray at critical growth stages of each crop.

3. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Plant Growth Metrics: Record plant height, leaf area, and dry matter accumulation at different stages.

- Yield Attributes: Measure green fodder yield (t ha⁻¹) and grain yield if applicable.

- Nutrient Uptake: Analyze plant tissue samples for N, P, K, and micronutrients (Zn, Fe).

- Soil Health Indicators: Post-harvest, analyze soil for available N, P, K, organic carbon, and microbial properties.

Protocol 2: Assessing Soil Microbial and Enzymatic Responses to INM

This protocol is derived from a long-term experiment on a double rice-cropping system [28].

1. Soil Sampling:

- Collect soil samples from the root zone (0-15 cm depth) at critical growth stages or after harvest.

- Process samples by sieving (2 mm) and store a subset at 4°C for biological analysis.

2. Microbial Biomass Carbon (MBC) Determination:

- Use the chloroform fumigation-extraction method.

- Fumigate soil samples with ethanol-free chloroform for 24 hours in a desiccator.

- Extract both fumigated and non-fumigated soils with 0.5 M K₂SO₄.

- Analyze the organic carbon in the extracts and calculate MBC using the formula: MBC = (Carbon from fumigated soil - Carbon from non-fumigated soil) / KEC, where KEC is a conversion factor (typically 0.45).

3. Microbial Population Count:

- Perform serial dilutions of soil suspensions.

- Plate onto appropriate media (e.g., nutrient agar for bacteria, Rose Bengal agar for fungi).

- Incubate and count colony-forming units (cfu g⁻¹ soil), converting to log values.

4. Soil Enzyme Assays:

- Dehydrogenase Activity: Measure by incubating soil with TTC (triphenyltetrazolium chloride) and quantifying the reduced TPF (triphenylformazan).

- Phosphomonoeasterase (Acid Phosphatase) Activity: Incubate soil with p-nitrophenyl phosphate and measure the released p-nitrophenol.

- Urease Activity: Incubate soil with urea and determine the released ammonium nitrogen.

- Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) Hydrolysis: Incubate soil with FDA and measure the fluorescein released, indicating overall microbial activity.

INM Experimental Workflow and Pathways

Diagram 1: INM experimental workflow from design to outcome.

Diagram 2: INM pathways to improved crop performance and reduced nutritional dilution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for INM Research

| Item | Function in INM Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Farmyard Manure (FYM) | Provides slow-release macro/micronutrients, improves soil structure and water retention [29] [28]. | Basal application at calculated N rate; e.g., 100% RDN through FYM [29]. |

| Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) | Bio-inoculants that fix N, solubilize P, produce phytohormones; enhance nutrient uptake and root development [29]. | Seed treatment before sowing [29]. |

| Panchagavya | Traditional bio-formulation rich in nutrients, hormones, and beneficial microbes; promotes plant metabolism and growth [29]. | 3% foliar spray at critical crop growth stages [29]. |

| Azolla | Aquatic fern that fixes atmospheric nitrogen; used as biofertilizer to supplement N in cropping systems [28]. | Application in rice fields to enhance N availability and boost bacterial populations [28]. |

| Chloroform | Organic solvent used for fumigation in the microbial biomass carbon determination assay [28]. | Soil fumigation prior to extraction for MBC calculation. |

| p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate | Synthetic substrate used for quantifying phosphomonoeasterase enzyme activity in soil [28]. | Incubated with soil sample; enzyme activity measured by yellow color intensity from p-nitrophenol release. |

| Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) | Colorless, water-soluble compound accepted by dehydrogenases and reduced to red, insoluble triphenylformazan (TPF) [28]. | Used as an electron acceptor in the assay to measure total soil dehydrogenase activity. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Substrate hydrolyzed by a broad range of enzymes (proteases, lipases, esterases); indicator of total microbial activity [28]. | Incubated with soil; hydrolysis measured by spectrophotometric detection of fluorescein. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Technologies & Reagents

The following table details the key technologies that function as the essential "research reagents" in modern precision agriculture experiments focused on nutritional outcomes.

| Technology / Solution | Primary Function in Research | Key Metric / Specification | Relevance to Nutritional Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multispectral/Hyperspectral Satellite Imagery [31] [32] | Measures crop reflectance to assess plant health and vigor (e.g., via NDVI). | Spatial Resolution: Sub-meter to meters; Spectral Bands: 4+ (Red, Green, Blue, NIR, Red Edge) [32]. | Detects subtle nutrient deficiency patterns across large field trials before visual symptoms appear, allowing for targeted correction. |

| AI-Powered Predictive Analytics [31] [32] | Analyzes historical & real-time data (imagery, weather, soil) to forecast yield and quality. | Prediction Accuracy: Can exceed 90% in detection tasks; leading yield models report ~98% accuracy [32] [33]. | Models the impact of specific interventions (e.g., micronutrient application) on final crop nutritional density, not just yield. |

| Soil & IoT Sensor Networks [34] [32] [35] | Provides real-time, continuous data on soil moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels. | Parameters: Soil moisture, temperature, NPK levels, electrical conductivity [32]. | Enables precise management of soil moisture and nutrients, key factors in preventing nutrient dilution from imbalanced irrigation or fertilization. |

| Variable Rate Technology (VRT) Systems [34] [36] | Precisely applies water, fertilizers, or other inputs at variable rates across a field based on prescription maps. | Input Reduction: Can reduce fertilizer and pesticide use by 20-70% [31] [32] [36]. | The execution tool for targeted nutritional interventions, applying supplements only where needed to optimize nutrient uptake. |

| Agricultural Drones (UAVs) [34] [32] | High-resolution aerial imaging and targeted spraying for small-scale experimental plots. | Application Impact: Can reduce pesticide use by up to 30% and enable targeted input application [32] [36]. | Ideal for high-precision phenotyping and applying experimental nutrient formulations in controlled field trials. |

Experimental Protocols for Nutritional Research

Protocol: Mapping Micronutrient Availability Using Remote Sensing

Objective: To establish a correlation between satellite-derived vegetation indices and foliar nutrient concentrations to identify zones of potential nutritional dilution.

Materials:

- Satellite imagery (e.g., Sentinel-2, Planet) with Red-Edge and Near-Infrared bands [32].

- GNSS/GPS receiver with submeter accuracy [37].

- Leaf sample collection kits (punches, bags, coolers).

- Access to a lab for foliar nutrient analysis.

Methodology:

- Scheduled Image Acquisition: Capture multispectral satellite imagery at key crop growth stages (e.g., stem elongation, flowering) [32].

- Generate Vegetation Indices: Calculate indices like NDVI (broad health) and NDRE (chlorophyll/content sensitivity) for the entire research area [32].

- Stratified Sampling: Based on index variability, stratify the field into high, medium, and low vigor zones. Within each zone, randomly assign geotagged sampling points [34].

- Field Sampling: At each point, collect leaf samples from a defined number of plants, record GPS coordinates, and process for lab analysis of target micronutrients (e.g., Zinc, Iron).

- Data Integration & Model Building: Integrate lab results with corresponding vegetation index values in a statistical model. Use regression analysis to establish a predictive relationship between spectral data and nutrient concentration [31] [32].

- Validation: Validate the model's accuracy using a separate set of ground-truthed samples.

Protocol: Implementing a Targeted Nutritional Intervention with VRT

Objective: To assess the efficacy of a variable-rate nutritional application in reducing the spatial variability of a target micronutrient in the harvested crop.

Materials:

- Prescription map from Protocol 1.

- VRT-capable sprayer or spreader [34] [36].

- Control and treatment formulations of the nutritional supplement.

Methodology:

- Prescription Map Development: Using the model from Protocol 1, create an application map that specifies a higher rate of nutritional supplement in zones predicted to have low nutrient concentration and a lower or zero rate in zones with sufficient levels [31] [34].

- Experimental Design: Establish control plots (uniform application) and treatment plots (variable-rate application) with sufficient replication.

- Precision Application: Use the VRT system to apply the supplement according to the prescription map. Log as-applied data to verify compliance [34].

- Post-Harvest Analysis: During harvest, use a yield monitor to collect georeferenced yield data. Collect grain/tissue samples from corresponding zones in both control and treatment plots.

- Efficacy Assessment: Analyze the harvested samples for nutrient concentration. Compare the variability and mean concentration between control and treatment plots to determine the intervention's success in homogenizing and elevating nutritional quality [38].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Data & Connectivity

Q1: Our field site has poor internet connectivity. How can we ensure reliable data transmission from IoT sensors?

A: This is a common challenge in rural research areas. Consider these solutions:

- Edge Computing: Use sensors or gateways with edge processing capabilities to perform initial data filtering and storage locally, transmitting only summarized data packets when a connection is available [39].

- LoRaWAN or Mesh Networks: Implement a Long-Range Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN) or a mobile mesh network that creates a local communication infrastructure independent of cellular data, which can then batch-send data to a central hub [39].

- Manual Data Retrieval: For small-scale, fixed plots, using data loggers with physical retrieval remains a reliable, though labor-intensive, fallback.

Q2: We are seeing a discrepancy between drone and satellite NDVI values for the same plot. Which data source should we trust?

A: Discrepancies are often due to different spatial resolutions and atmospheric conditions.

- Check Spatial Resolution: Drone imagery typically has a much higher resolution (centimeters) than satellite imagery (meters). The satellite pixel might be averaging the signal from the plant and any exposed soil, lowering the NDVI value [32] [36]. Ensure you are comparing data at a comparable scale.

- Verify Acquisition Time: Atmospheric haze, clouds, or different sun angles at the time of capture can affect readings. Always use atmospherically corrected satellite data and try to align acquisition times as closely as possible [32].

- Calibration: Use ground-based spectroradiometer measurements to calibrate both your drone and satellite-derived indices for your specific crop and conditions.

FAQ: Implementation & Analysis

Q3: Our AI yield prediction model is performing well overall but is highly inaccurate in specific parts of the field. What could be the cause?

A: This is often a sign of algorithmic bias or insufficient model training data for certain soil or management conditions [33].

- Root Cause Analysis: Investigate the inaccurate zones. Are they characterized by a specific soil type, a history of pest pressure, or a different management history that isn't well-represented in the model's training data? [33].

- Solution: Retraining with Targeted Data: Collect more ground-truthed data (e.g., hand-harvested yields) specifically from these underperforming zones and retrain your model with this enriched dataset. Techniques like "transfer learning" can also be explored to adapt a general model to your specific field anomalies [31] [33].

Q4: How can we effectively track the impact of our interventions on nutritional content without testing every single plant?

A: Leverage the stratified sampling approach from Protocol 1.

- Zone-Based Sampling: Do not sample randomly. Use your satellite-derived zones (e.g., high, medium, low vigor) as your sampling strata. This ensures you capture the full range of variability with far fewer samples [34].

- Composite Sampling: Within each zone and for each treatment, create a composite sample by combining tissue from multiple plants. This provides a representative value for the zone and reduces the number of lab tests required.