Correlating Continuous Glucose Monitoring with Food Intake: From Foundational Science to Clinical Endpoints in Drug Development

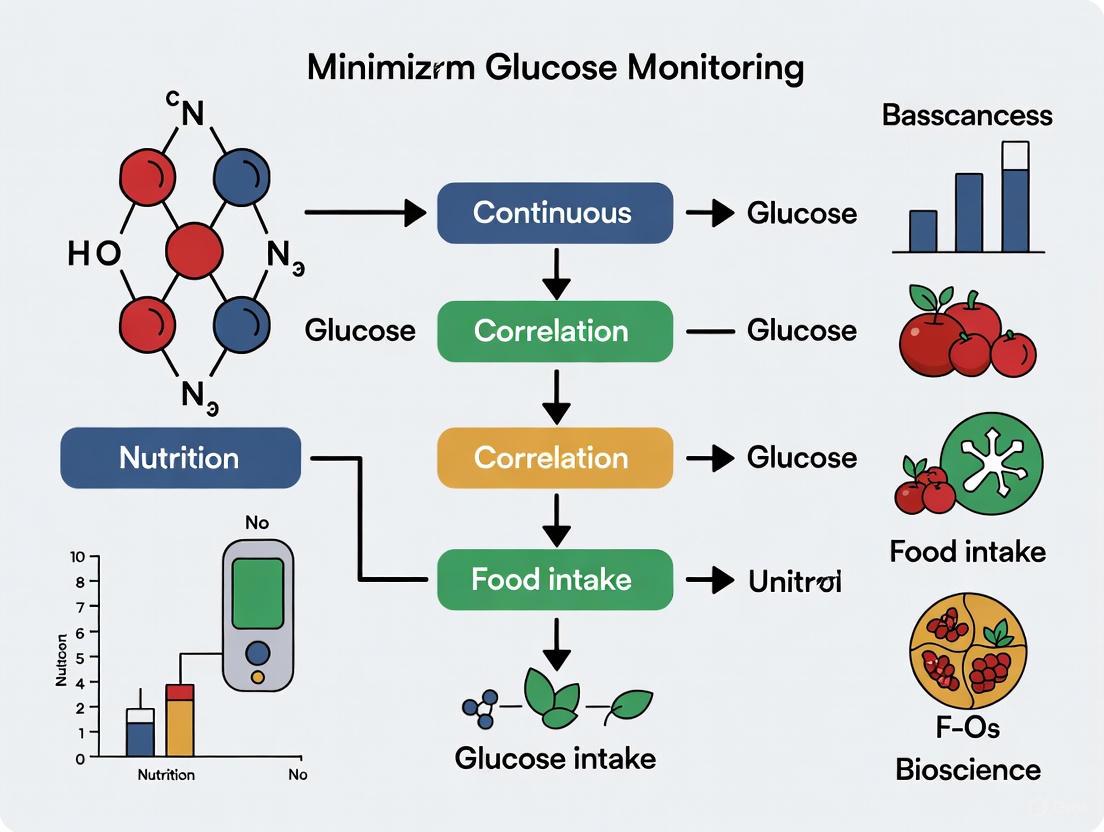

This article synthesizes the latest evidence on the application of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) for correlating food intake with glycemic responses, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Correlating Continuous Glucose Monitoring with Food Intake: From Foundational Science to Clinical Endpoints in Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest evidence on the application of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) for correlating food intake with glycemic responses, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of glucose dynamics, examines advanced methodological approaches like Functional Data Analysis (FDA) for modeling postprandial trajectories, and reviews the use of CGM-derived endpoints like Time in Range (TIR) in clinical trials. The content further addresses the critical evaluation of CGM device performance and the optimization of dietary interventions, providing a comprehensive resource for integrating CGM data into biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Understanding Glucose Dynamics: The Physiological Basis of Food-Induced Glycemic Responses

Core Principles of Postprandial Glucose Metabolism in Health and Disease

Postprandial glucose metabolism represents a critical physiological process wherein the body regulates blood sugar levels following food intake. Effective control of postprandial glucose responses (PPGR) is essential for managing the progression of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and overall metabolic health [1] [2]. The global epidemic of T2DM, affecting approximately 537 million people worldwide, underscores the urgent need to understand these core principles [3]. Postprandial glucose excursions contribute significantly to elevated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and are independently associated with increased risk of cardiovascular complications, neuropathy, and kidney damage [3]. Recent advances in continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology have revolutionized our ability to study these metabolic processes in real-time, providing unprecedented insights into the complex interplay between dietary factors, physiological mechanisms, and individual variability in glucose regulation [4] [3] [5].

Physiological Mechanisms of Postprandial Glucose Regulation

Key Metabolic Pathways

The regulation of postprandial glucose involves multiple integrated physiological processes across various tissues and organ systems. Following carbohydrate ingestion, the breakdown of complex carbohydrates into monosaccharides enables intestinal absorption, primarily as glucose, which enters the bloodstream and triggers a cascade of metabolic responses [6]. Insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells represents the primary hormonal response, facilitating glucose uptake into insulin-sensitive tissues including skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and liver. Simultaneously, incretin hormones such as GLP-1 and GIP amplify glucose-dependent insulin secretion while inhibiting glucagon release and delaying gastric emptying.

Skeletal muscle constitutes the major site for postprandial glucose disposal, accounting for approximately 70-80% of ingested glucose clearance under normal physiological conditions. The process is mediated by insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell surface. Concurrently, the liver suppresses endogenous glucose production and enhances glycogen synthesis. These coordinated processes normally limit postprandial glucose excursions to a peak of <140 mg/dL within 30-60 minutes after eating, returning to baseline within 2-3 hours.

Disrupted Mechanisms in Disease States

In insulin-resistant states such as T2DM, these regulatory mechanisms become compromised at multiple levels. Peripheral tissues, particularly skeletal muscle, exhibit reduced sensitivity to insulin, impairing glucose disposal. Hepatic insulin resistance fails to adequately suppress endogenous glucose production, resulting in continued glucose output despite elevated postprandial glucose levels. Additionally, pancreatic β-cell dysfunction leads to impaired, delayed, or insufficient insulin secretion relative to the glucose load. These defects collectively result in exaggerated and prolonged postprandial hyperglycemia, which further contributes to glucotoxicity and progressive metabolic deterioration [3].

Recent research has highlighted that the entire musculature normally accounts for only about 15% of the oxidative metabolism of glucose when sitting inactive, despite being the body's largest lean tissue mass [6]. This suggests that methods capable of elevating oxidative muscle metabolism could be advantageous to complement other lifestyle and pharmacological approaches whose mechanisms of action are limited to non-oxidative metabolic pathways.

The following diagram illustrates the core pathways of postprandial glucose regulation in health and their dysregulation in disease states:

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Postprandial Glucose Metabolism

Continuous Glucose Monitoring Methodologies

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has emerged as a transformative technology for investigating postprandial glucose metabolism in both research and clinical settings. CGM devices measure glucose concentrations in the interstitial fluid at regular intervals (typically every 5-15 minutes), providing high-resolution temporal data on glucose fluctuations [3]. This comprehensive profiling enables researchers to capture postprandial glucose peaks, excursion duration, and glucose variability that would be missed with conventional intermittent blood sampling.

Standard CGM-derived metrics for assessing postprandial glucose metabolism include:

- Postprandial glucose peak: The maximum glucose level reached after meal consumption

- Incremental Area Under the Curve (iAUC): The net increase in glucose above baseline following a meal

- Time in Range (TIR): The percentage of time glucose levels remain within a target range (typically 70-180 mg/dL)

- Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursions (MAGE): A measure of glycemic variability

- 24-hour mean glucose: The average glucose concentration across a full day [4] [5]

Recent research has demonstrated significant correlations between various CGM metrics and dietary factors. A study in healthy adults found significant positive moderate correlations between glycemic load and several CGM metrics including area under the curve (ρ = 0.40), relative amplitude (ρ = 0.40-0.42), and standard deviation (ρ = 0.41) in time windows of 2-4 hours postprandially [7].

Personalized Nutrition Approaches

Substantial interindividual variability in postprandial glucose responses to identical foods has driven the development of personalized nutrition approaches. Research has shown that no two individuals share the same dietary and temporal predictors of PPG excursions [3]. This variability stems from differences in biological factors (insulin sensitivity, gut microbiota composition, genetic variations), food properties (food structure, nutrient composition), and behavioral contexts (meal timing, eating rate, physical activity patterns) [2].

N-of-1 trial designs have emerged as a powerful methodology for investigating this individual variability. These trials determine individual responses to specific interventions through prospective, randomized crossover designs conducted either on individual patients or a series of patients [1] [2]. A prototypical N-of-1 trial protocol for testing PPGR to various staple foods involves:

- Randomizing participants to receive different test foods (e.g., white rice, germ rice, brown rice, rice noodles, pasta) three times in a randomized order

- Using CGM to track PPGR at 5-minute intervals

- Standardizing available carbohydrate content across test meals (typically 50g)

- Maintaining consistent accompanying foods and meal timing

- Applying Bayesian analysis at both individual and group levels to assess PPGR [2]

Machine learning approaches have further advanced personalized predictions of PPG excursions. Personalized models trained on individual CGM data, with or without manually-logged meal information, can predict PPG excursions with average F1-scores of 75.88% [3]. These models enable identification of individual "vulnerability states" - periods of heightened susceptibility to PPG excursions - which can inform just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) for glycemic control.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental approach for personalized postprandial glucose research:

Quantitative Data on Dietary Interventions and Postprandial Glucose Responses

Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets

Meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that carbohydrate-restricted diets (CRDs) significantly improve 24-hour mean blood glucose in patients with T2DM (d = -0.51, 95% CI: -0.88 to -0.14, p < 0.05) [4]. Exploratory trend analysis suggests a positive correlation between intervention duration and the magnitude of 24-hour mean glucose reduction, with longer interventions (≥1 year) potentially yielding greater benefits, though this requires confirmation through longer-term randomized controlled trials [4].

Table 1: Effects of Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets on Glucose Metrics in T2DM

| Intervention Type | Duration | Participants | Effect on 24-h Mean Glucose | Other Significant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-carbohydrate diets (≤45% energy from carbs) | 6 days to 6 months | 301 (pooled) | Standardized mean difference: -0.51 (95% CI: -0.88 to -0.14) | Trend toward greater improvement with longer duration |

| Very-low-carbohydrate diets (<26% energy from carbs) | Varies | Subset of above | Generally larger effects | Improved β-cell function and insulin sensitivity |

Diet Quality and Carbohydrate Composition

Beyond carbohydrate quantity, diet quality and carbohydrate composition significantly influence postprandial glucose profiles. Data from the Framingham Heart Study demonstrates that higher overall diet quality and better carbohydrate quality are associated with favorable CGM-derived metrics [5]. Specifically, replacing 5% of energy intake from protein with equivalent energy from carbohydrates was associated with a 0.97 mg/dL higher CGM mean glucose (SE = 0.47; P = 0.04) [5].

Notably, consuming a diet with more than 1g of fiber for every approximately 9g of carbohydrates was associated with 7-10% lower time spent above 140 mg/dL compared with higher carb-to-fiber ratios in individuals with prediabetes (P-trend < 0.001) [5]. This highlights the importance of considering carbohydrate quality rather than merely quantity in dietary interventions for glucose management.

Table 2: Association of Diet Quality and Carbohydrate Composition with CGM Metrics

| Dietary Factor | Population | Key Associations with CGM Metrics | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Diet Quality | Normoglycemic (n=385) | Stronger associations with favorable CGM measures | More pronounced in normoglycemia |

| Carbohydrate-to-Fiber Ratio | Prediabetes (n=292) | Higher ratio associated with increased time >140 mg/dL | 7-10% reduction with ratio <~9:1 |

| Carbohydrate Substitution | Overall (n=677) | Replacing protein with carbohydrates increased mean glucose | 0.97 mg/dL increase per 5% energy |

Physical Activity Interventions

Brief interruptions to prolonged sitting, known as "exercise snacks," acutely attenuate postprandial glucose and insulin responses in adults with obesity [8]. Meta-analysis of 17 trials (261 unique participants) showed that versus uninterrupted sitting, activity breaks reduced glucose iAUC (SMD = -0.49, 95% CI: -0.85 to -0.14) and insulin iAUC (SMD = -0.26, 95% CI: -0.50 to -0.03) [8]. Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested larger effects with higher-frequency (≤30-minute) and short-bout (≤3-minute) interruptions and with walking or simple resistance activities.

Different types of physical activity induce distinct physiological processes that either oppose or enhance postprandial glucose tolerance [6]. Methods capable of elevating oxidative muscle metabolism, such as specialized soleus muscle activity, may be particularly advantageous as they complement other lifestyle and pharmacological approaches whose mechanisms of action are limited to non-oxidative metabolic pathways [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Technologies for Postprandial Glucose Studies

| Research Tool | Specification/Model | Primary Research Application | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Dexcom G7 or equivalent | Real-time glucose measurement in interstitial fluid | 5-15 minute sampling intervals; MARD <9% |

| CGM Data Analysis Software | "cgmanalysis" R package or equivalent | Calculation of glycemic variability metrics | Computes iAUC, MAGE, CONGA, TIR, etc. |

| Standardized Test Meals | Varies by protocol (e.g., 50g available carbohydrate) | Controlled nutrient challenge for PPGR assessment | Precise macronutrient composition |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | Digital food diaries, image-assisted methods | Tracking dietary intake and timing | Correlation with CGM metrics (ρ = 0.40-0.45) |

| Physical Activity Monitors | Research-grade accelerometers | Quantifying activity patterns and energy expenditure | MET estimation, sedentary time quantification |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Python Scikit-learn, R caret | Personalized PPG excursion prediction | F1-score for prediction (~75.88%) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

N-of-1 Trial Protocol for Staple Food Testing

This protocol systematically evaluates individual postprandial glucose responses to different carbohydrate-rich staple foods using a randomized, crossover N-of-1 design [2].

Materials and Setup:

- CGM device with 5-minute sampling capability

- Standardized test meals with 50g available carbohydrate portions

- Digital food scales and preparation guidelines

- Meal timing and contextual factor logging system

Test Diet Composition:

- Staple foods: White rice (143g), germ rice (175g), brown rice (173g), rice noodles (198g), pasta (178g) - portions adjusted to provide 50g available carbohydrates

- Accompanying foods: 150g scrambled eggs with tomatoes, 50g cucumber, 200mL milk (consistent across tests)

- Nutritional analysis: Verify macronutrient composition through certified laboratory analysis

Experimental Procedure:

- Participant screening: Recruit adults with T2DM (age 18-70 years) diagnosed for ≥3 months, on stable lifestyle intervention or single hypoglycemic medication

- Baseline assessment: Collect demographic data, medical history, anthropometric measurements

- Randomization sequence: Generate computerized randomization schedule for the 5 test diets across 3 periods (15 test days total)

- Test day protocol:

- Overnight fast of 10-12 hours

- Baseline CGM reading pre-meal

- Test meal consumption within 20 minutes under supervision

- CGM monitoring for 3-5 hours postprandially

- Standardized physical activity and medication patterns across test days

- Data collection: Capture CGM data at 5-minute intervals, document meal timing, self-reported symptoms, and contextual factors

Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate primary outcome (postprandial blood glucose peak) and secondary outcomes (iAUC, time to peak, time to return to baseline)

- Apply Bayesian hierarchical models for individual and group-level inference

- Conduct sensitivity analyses adjusting for potential confounding factors (medication timing, prior physical activity, sleep quality)

Protocol for Exercise Snack Interventions

This protocol examines the acute effects of brief activity breaks on postprandial glucose metabolism in adults with obesity [8].

Experimental Conditions:

- Control condition: Uninterrupted sitting

- Intervention conditions: Interruptions of sitting every 30 minutes with 2-5 minutes of light-to-moderate activity (walking or simple resistance exercises)

Outcome Measures:

- Co-primary outcomes: Glucose iAUC and insulin iAUC

- Secondary outcomes: Total AUC, mean glucose and insulin levels, glucose and insulin peaks

Standardized Procedures:

- Pre-test standardization: 48-hour control of diet and physical activity prior to testing

- Test meal: Standardized mixed meal (e.g., 75g carbohydrate, 25g protein, 15g fat)

- Blood sampling: Frequent venous blood samples (every 15-30 minutes) for 2-3 hours postprandially

- Activity protocols: Precisely timed activity breaks with standardized intensity and duration

- Data analysis: Calculate iAUC using the trapezoidal method above baseline; compare conditions using linear mixed models with participant as random effect

This systematic approach enables rigorous investigation of the dose-response relationships between activity interruption patterns and postprandial metabolic outcomes.

CGM as a Tool for Behavioral Modification and Lifestyle Guidance

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) has transcended its original purpose as a passive glucose tracking tool for diabetes management, emerging as a dynamic technology for motivating behavioral modification and guiding lifestyle choices. By providing real-time, visual feedback on how nutrition, physical activity, and other daily behaviors impact glycemic responses, CGM serves as a powerful catalyst for behavior change [9]. This application note details the quantitative evidence, underlying behavioral mechanisms, and practical protocols for utilizing CGM as an intervention tool in research and clinical practice, framing its use within the broader context of food intake correlation research.

Quantitative Evidence: CGM Metrics and Behavioral Outcomes

The efficacy of CGM-driven interventions is supported by a growing body of quantitative research linking specific CGM metrics to dietary components and behavioral changes. The tables below summarize key findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Correlations between CGM Metrics and Dietary Components in a Healthy Cohort (n=48) [10]

| Dietary Component | Correlated CGM Metric(s) | Correlation Coefficient (ρ) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycemic Load (GL) | Relative Amplitude (4-hour window) | 0.42 | P < .0004 |

| Standard Deviation (4-hour window) | 0.41 | P < .0004 | |

| Variance (4-hour window) | 0.43 | P < .0004 | |

| Carbohydrates | Standard Deviation (24-hour) | 0.45 | P < .0004 |

| Variance (24-hour) | 0.44 | P < .0004 | |

| Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursions (MAGE) | 0.40 | P < .0004 |

Table 2: Effects of Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets (CRDs) on 24-Hour Mean Glucose in T2DM (Meta-Analysis) [4]

| Parameter | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|

| Overall Effect | Significant improvement in 24-h mean blood glucose (d = -0.51, 95% CI: -0.88 to -0.14, p < 0.05) |

| Intervention Duration | Exploratory trend analysis suggested a positive correlation between longer intervention duration and greater magnitude of glucose reduction. |

| Conclusion | CRDs may improve 24-h MBG in T2DM patients, with longer durations potentially yielding greater benefits. |

Table 3: Self-Reported Behavioral Changes in CGM Users (Survey of n=40 Users) [11]

| Behavioral Change | Percentage of Users Reporting Change |

|---|---|

| Overall healthier lifestyle | 90% |

| Modified food choices | 87% |

| Noticed how food affects glucose | 87.5% |

| Increased physical activity | 42.5% |

| More likely to walk/be active after seeing glucose rise | 47.5% |

Mechanism of Action: The CGM-Driven Feedback Loop

CGM facilitates behavior change through a continuous feedback loop, transforming abstract dietary choices into tangible, visual outcomes. The process can be summarized in the following workflow, which illustrates how CGM data leads to sustained behavioral modification.

Experimental Protocols for CGM-Based Behavioral Research

Protocol: Investigating the Diet-Glucose Relationship in Free-Living Populations

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully correlated CGM metrics with dietary intake in free-living conditions [10] [5] [12].

Objective: To quantify the relationship between meal composition (macronutrients, glycemic load) and subsequent glycemic responses in a target population.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. CGM devices should be selected based on required data accessibility (blinded vs. unblinded) and approval for use in the target population (e.g., FDA-cleared for over-the-counter use in non-insulin using populations) [13].

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment & Sensor Application: Recruit participants according to inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., adults with or without diabetes). Apply CGM sensor according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Dietary Recording: Participants concurrently record all food and beverage intake for a minimum of 3 days. Preferred methods include:

- Image-assisted Dietary Log: Use of a wearable camera (e.g., eButton) [12] or smartphone to capture images of all meals and snacks.

- Digital Food Diary: Utilization of a mobile app to log food type, estimated portion size, and timing.

- Data Collection Period: Maintain simultaneous CGM wear and dietary recording for a target of 10-14 days to capture intra-individual variability [12].

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- CGM Data: Extract standard glycemic metrics (e.g., mean glucose, TIR, TAR, TBR, GV, MAGE) using analysis packages (e.g.,

cgmanalysisR package) [5]. - Dietary Data: Convert food logs into quantitative nutritional data (energy, carbs, protein, fat, fiber, glycemic load).

- Statistical Analysis: Employ linear mixed models to account for repeated measures within individuals. Correlate dietary components (independent variables) with CGM metrics (dependent variables).

- CGM Data: Extract standard glycemic metrics (e.g., mean glucose, TIR, TAR, TBR, GV, MAGE) using analysis packages (e.g.,

Protocol: A Nutrition-Focused CGM Initiation Intervention

This protocol is based on the "Using Nutrition to Improve Time in Range (UNITE)" study, which integrated evidence-based nutrition guidance with CGM initiation [14].

Objective: To evaluate the impact of a structured, nutrition-focused educational session during CGM initiation on subsequent food-related behaviors and glycemic outcomes.

Materials: CGM device and companion app; NFA educational materials (e.g., interactive slides, one-page CGM nutrition guide) emphasizing a "1, 2, 3 approach" (check glucose before, 1-2 hours after meals) and a "yes/less framework" for food choices [14].

Procedure:

- Baseline & Recruitment: Recruit eligible participants (e.g., non-insulin-using T2D adults). Collect baseline HbA1c and demographic data.

- Session 1 - CGM Initiation & Education (60 mins, in-person):

- Apply the CGM sensor.

- Deliver the NFA curriculum using the prepared materials. Key messages include:

- Defining glucose goals (TIR >70%, TBR <4%).

- Teaching the "1, 2, 3" method for discovering personal postprandial responses.

- Introducing the "yes/less" food choice framework to align eating patterns with evidence-based nutrition guidance.

- Free-Living Phase (14 days): Participants use the CGM in real-time. They are encouraged to actively review their data before and after meals.

- Session 2 - Data Review & Reinforcement (30 mins, remote):

- Review the participant's ambulatory glucose profile (AGP) report.

- Discuss patterns and link high or low glucose events to specific meals or behaviors.

- Problem-solve and reinforce nutrition messages from Session 1.

- Outcome Assessment (2-month endpoint):

- Quantitative: Analyze CGM metrics (TIR, GV) from the final 2 weeks of the study.

- Qualitative: Conduct semi-structured interviews to understand user experience, perceived behavior change, and intervention receipt [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Tools for CGM-Based Behavioral Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples & Functions |

|---|---|

| CGM Systems | Dexcom G7/Freestyle Libre: For real-time, unblinded data collection. Blinded Pro versions: For objective endpoint assessment without participant behavior influence. Stelo Glucose Biosensor: An over-the-counter CGM indicated for non-insulin using adults to understand lifestyle impacts [13]. |

| Dietary Assessment Tools | eButton: A wearable, automatic camera that captures food images, reducing self-reporting burden and bias [12]. Digital Food Diaries (Apps): Log food intake, timing, and portion sizes. Dietitian-Led 24-hr Recall: Validated method for reconstructing dietary intake and calculating nutrient composition and glycemic load [10]. |

| Data Analysis Software | cgmanalysis R Package: A standardized tool for batch-processing CGM data and calculating a wide array of glycemic metrics (Mean glucose, TIR, MAGE, etc.) [5]. Functional Data Analysis (FDA) Software (R, MATLAB): For analyzing entire postprandial glucose trajectories instead of scalar summaries, revealing time-dependent effects of diet [15]. |

| Educational & Visualization Aids | Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) Report: The international standard report for visualizing CGM data, using color-coding (Green=TIR, Red=TBR) for quick pattern recognition [16]. Nutrition-Focused Approach (NFA) Guides: Simplified materials (e.g., "yes/less" framework) to help users connect CGM data with evidence-based food choices [14]. |

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Outcomes of Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets

Table 1: Composite findings from meta-analyses on cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes.

| Outcome Measure | Effect of CRDs | Magnitude of Change (SMD or Mean Difference) | Certainty of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides | Significant reduction | SMD: −15.11 mg/dL (CI: −18.76, −11.46) [17] [18] | High |

| HDL Cholesterol | Significant increase | SMD: +2.92 mg/dL (CI: 2.10, 3.74) [17] [18] | High |

| LDL Cholesterol | Modest increase | SMD: +4.81 mg/dL (CI: 2.58, 7.05) [17] [18] | High |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | Significant reduction | SMD: −2.05 mmHg (CI: −3.13, −0.96) [17] [18] | High |

| 24-h Mean Blood Glucose (T2D) | Significant reduction | d = −0.51 (CI: −0.88, −0.14) [4] [19] | Moderate |

| HOMA-IR | Significant reduction | SMD: −0.54 (CI: −0.75, −0.33) [20] | High |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Significant reduction | SMD: −0.48 (CI: −0.75, −0.21) [17] | High |

Body Composition and Dose-Response Weight Loss

Table 2: Impact on body composition and dose-response weight loss effects.

| Parameter | Effect of CRDs | Details / Dose-Response | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight | Significant reduction | Each 10% decrease in carb intake reduced body weight by 0.64 kg (6-month) and 1.15 kg (12-month) [21] | |

| Optimal Long-Term Intake | Non-linear effect | Greatest weight reduction at ~30% carbohydrate intake in follow-ups >12 months [21] | |

| All Body Composition Markers | Significant reductions | Includes body fat percentage, waist circumference, and fat mass [17] | |

| Ketogenic Diet Trade-off | Greatest weight loss | But associated with greater increases in LDL and total cholesterol vs. moderate-carb diets [17] [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Research and Clinical Application

Protocol 1: 6-Month Medically-Supervised Ketogenic Diet Program (MSKDP) with CGM

This protocol is adapted from a randomized clinical trial evaluating CGM versus BGM during a carbohydrate-restricted nutrition intervention [22].

- Objective: To evaluate the effects of a virtual, medically supervised ketogenic diet program on glycemic control, medication use, and weight in adults with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) over 6 months.

- Population: Adults with T2D (e.g., mean HbA1c ~8.1%, mean duration ~9.7 years) [22].

- Intervention Arm (CGM):

- Diet: Medically supervised ketogenic diet program. Macronutrient composition is not fully detailed but implies a significant reduction in carbohydrates.

- Monitoring: Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) for real-time glucose feedback.

- Support: Virtual program with remote supervision.

- Medication Management: Protocol for insulin and/or other diabetes medication de-intensification based on glucose data.

- Control Arm (BGM):

- Diet: Identical medically supervised ketogenic diet program.

- Monitoring: Use of Blood Glucose Monitoring (BGM) with finger-stick checks.

- Support & Medication Management: Identical to the CGM arm.

- Primary Outcomes:

- Glycemic Control: Time in Range (TIR 70-180 mg/dL), HbA1c.

- Diabetes Medication Effect Score (MES).

- Body Weight.

- Carbohydrate and Energy Intake (via dietary recalls).

- Key Findings: Both CGM and BGM arms achieved significant and equivalent improvements from baseline: TIR increased from ~61-63% to ~87-88%, HbA1c decreased by ≥1.3%, and participants experienced clinically meaningful weight loss with significant medication de-intensification [22].

Protocol 2: Time-Restricted Eating (TRE) with Low-Carbohydrate Diet for Insulin-Using T2D

This protocol is designed for insulin-using patients, a population often excluded from such interventions due to hypoglycemia risk [23].

- Objective: To assess the safety and feasibility of a combined low-carbohydrate and time-restricted eating protocol in adults with T2D who use insulin.

- Population: Insulin-using adults with T2D (e.g., ages 49-77) [23].

- Intervention:

- Dietary Pattern: Low-carbohydrate (≤30 grams per day) combined with Time-Restricted Eating (TRE).

- Eating Window: Two meals per day within a self-selected 6- to 8-hour window.

- Core Component: A proactive, structured insulin titration protocol to reduce hypoglycemia risk. Baseline total daily insulin is typically reduced by 30-50% upon initiation.

- Monitoring & Safety:

- Close glucose monitoring (BGM or CGM).

- Documentation of symptomatic and biochemical hypoglycemic events (e.g., glucose <70 mg/dL).

- Outcomes:

- Primary: Hypoglycemic events requiring medical care; adherence to the timed eating protocol.

- Secondary: Daily insulin use, HbA1c, Body Mass Index (BMI), blood pressure, and quality-of-life metrics.

- Key Findings: The protocol was demonstrated to be feasible and safe. After 6 months, average daily insulin use decreased significantly (by 62.2 units), with 74% of participants discontinuing insulin entirely. No episodes of severe hypoglycemia occurred, and significant improvements were seen in BMI and systolic blood pressure [23].

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and tools for research on carbohydrate-restricted diets and glucose monitoring.

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Measures interstitial glucose concentrations nearly continuously (e.g., every 5 minutes), providing high-resolution data on 24-hour mean blood glucose, time-in-range, and glycemic variability [4] [22]. | Core device for correlating food intake (macronutrient composition and timing) with glycemic excursions in real-world settings [22]. |

| Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (BHB) Meter | Quantifies blood ketone concentrations, serving as an objective biomarker of adherence to a ketogenic diet and confirming a state of nutritional ketosis [20]. | Differentiating metabolic effects of ketogenic vs. non-ketogenic low-carbohydrate diets. |

| Standardized Biochemical Assays | Measurement of key metabolic biomarkers from blood samples, including HbA1c, lipid profiles (TG, HDL-C, LDL-C), and inflammatory markers (CRP, TNF-α, sICAM-1) [17] [24] [25]. | Evaluating comprehensive cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes in response to dietary intervention. |

| Dietary Assessment Platform | Tools for collecting and analyzing participant dietary intake, such as 24-hour dietary recalls or food frequency questionnaires, to verify compliance with macronutrient targets [22]. | Quantifying actual carbohydrate, fat, and protein intake to ensure internal validity and analyze dose-response relationships [21]. |

| Insulin & HOMA-IR Assays | Precise measurement of fasting insulin and glucose for calculating Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), a key metric of metabolic health [20] [24]. | Assessing the impact of carbohydrate restriction on underlying insulin sensitivity, independent of glycemia. |

Within continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and food intake correlation research, a central challenge is distinguishing true, biologically meaningful individual differences from transient fluctuations caused by measurement variability or temporary physiological states. Research into individual differences requires accurately quantifying among-individual variation in the trait in question, a process that depends on standardized, repeatable measurement protocols [26]. The dynamic nature of human physiology means that multiple measurements are required to estimate a stable central tendency from a dynamic system [27]. This Application Note provides detailed methodologies for quantifying individual variability in glycemic responses, framing these protocols within the broader context of personalized nutrition and metabolic drug development.

Quantitative Data on Individual Glycemic Variability

Table 1: Key CGM-Derived Metrics for Quantifying Individual Glycemic Variability

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description | Research Significance | Representative Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Glucose | 24-hour Mean Blood Glucose (MBG) | Average glucose concentration over 24 hours [4]. | Primary outcome for dietary interventions; reflects overall glycemic control. | CRDs show a significant improvement (d = -0.51, 95% CI: -0.88 to -0.14) [4]. |

| Glycemic Variability | Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursions (MAGE) | Average height of excursions that exceed one standard deviation from the mean [5]. | Captures postprandial swings and glucose instability. | Associated with overall diet quality and carbohydrate quality [5]. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Standard deviation of glucose values divided by the mean glucose (expressed as a percentage) [5]. | Indicator of glucose stability; lower CV suggests greater stability. | ||

| Continuous Overall Net Glycemic Action (CONGA-1) | Glycemic variability over a 1-hour interval [5]. | Measures intra-day variability. | ||

| Mean of Daily Differences (MODD) | Average of absolute differences between glucose values at the same time on successive days [5]. | Measures day-to-day variability. | ||

| Time-in-Range | % Time >140 mg/dL | Percentage of time spent above the hyperglycemic threshold [5]. | Direct measure of hyperglycemic exposure. | In prediabetes, higher fiber intake and lower carb-to-fiber ratio are associated with 7-10% lower time >140 mg/dL [5]. |

Table 2: Influence of Dietary Factors on Glycemic Metrics

| Dietary Factor | Effect on Glycemic Metrics | Notes on Individual Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets (CRDs) | Significant improvement in 24-hour MBG [4]. | Effect size may correlate with intervention duration; exploratory analysis suggests greater benefits with longer durations [4]. |

| Carbohydrate Substitution | Replacing 5% energy from protein with carbohydrate associated with a 0.97 mg/dL higher CGM mean glucose [5]. | Highlights the impact of macronutrient composition independent of overall energy intake. |

| Carbohydrate Quality (Fiber, Carb-to-Fiber Ratio) | Higher quality associated with favorable CGM measures, including lower time above range and reduced variability [5]. | Associations are typically more pronounced in individuals with normoglycemia compared to those with prediabetes [5]. |

| Overall Diet Quality (HEI, aMED, DASH) | Higher scores are associated with favorable CGM-derived measures [5]. | Suggests comprehensive dietary patterns can influence glycemic variability. |

Experimental Protocols for Standardized Challenges

Dynamic In Vitro Interference Testing of CGM Sensors

Purpose: To validate CGM sensor performance and identify measurement variability introduced by interfering substances under controlled, dynamic conditions [28].

Key Materials:

- CGM Sensors: Dexcom G6 (user-calibrated) and Freestyle Libre 2 (factory-calibrated) sensors.

- Macrofluidic Test Bench: A 3D-printed solid block with a fluidic channel (e.g., 2 mm × 10 mm × 500 mm), housing sensor needles [28].

- Fluid Delivery System: High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) pumps for generating programmable gradients of glucose and interferents in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [28].

- Reference Analyzer: YSI 2300 Stat Plus for reference glucose measurements [28].

Procedure:

- Setup: Place at least three sensors from each CGM system on the test bench. Initiate device operation according to manufacturers' instructions [28].

- Calibration: Calibrate user-calibrated sensors (e.g., Dexcom G6) at a stable glucose level (e.g., 120 mg/dL) against the reference method [28].

- Glucose Gradient Test:

- Start with a stable glucose level (e.g., 100 mg/dL) for 30 minutes.

- Increase glucose to a higher level (e.g., 300 mg/dL) at a controlled rate (e.g., 2 mg/dL/min).

- Maintain the high level for 30 minutes.

- Return to the baseline level at the same controlled rate.

- Maintain the baseline for a final 30 minutes [28].

- Substance Interference Test:

- Stabilize the system at a fixed glucose concentration (e.g., 200 mg/dL).

- Superimpose a gradient of the test interferent (e.g., acetaminophen, xylose, maltose) from 0 to a target concentration over 30 minutes.

- Maintain the peak interferent concentration for 30 minutes.

- Reduce the interferent back to 0 mg/dL over 30 minutes [28].

- Data Collection: Record sensor readings and collect outflow samples for reference measurement at least every 10 minutes throughout all experiments [28].

- Analysis: For user-calibrated sensors, interference is defined as a >20% difference between reference and sensor readings at maximal interferent concentration. For factory-calibrated sensors, calculate the "Bias Over Baseline" (BOB) [28].

Protocol for Assessing Diet-Glycemia Associations in Cohort Studies

Purpose: To cross-sectionally evaluate associations between diet composition/quality and CGM-derived glycemic metrics in free-living populations, accounting for individual variability [5].

Key Materials:

- Cohort: A well-characterized population-based cohort (e.g., Framingham Heart Study).

- CGM Devices: Participants wear a CGM sensor for a minimum of 3 days.

- Dietary Records: Multiple self-reported dietary records (e.g., ≥2 days), analyzed for nutrient composition and diet quality indices.

Procedure:

- Participant Selection: Include adults with and without diabetes. Exclude participants with insufficient CGM wear time or dietary data [5].

- Data Collection:

- Collect CGM data for the specified period.

- Collect dietary intake data concurrently or within a close timeframe.

- Gather covariate data (e.g., age, sex, BMI, glycemic status).

- CGM Data Processing: Calculate glycemic traits (MBG, MAGE, CV, CONGA, MODD, Time-in-Range) using standardized packages (e.g.,

cgmanalysisR package) [5]. - Dietary Data Processing: Calculate dietary indices (Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Mediterranean Diet Score, etc.), carbohydrate intake, fiber intake, and carb-to-fiber ratios [5].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use multivariable linear regression models to assess relationships between dietary exposures and CGM outcomes, adjusting for covariates.

- Perform subgroup analyses stratified by glycemic status (normoglycemia vs. prediabetes/diabetes).

- Model macronutrient substitution effects (e.g., replacing protein with carbohydrate).

- Visualize adjusted group differences across quartiles of diet quality metrics [5].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Diet-Glycemia Association Study Workflow

Diagram 2: Sources of Variability in CGM Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for CGM Variability Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Device that measures glucose concentrations in interstitial fluid at regular intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes) [28] [5]. | Core device for capturing dynamic glycemic data in free-living or clinical settings. Examples: Dexcom G6, Freestyle Libre 2 [28]. |

| High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Pumps | Generate precise, programmable gradients of glucose and potential interferents in a buffer solution [28]. | Essential for dynamic in vitro testing of CGM sensors under controlled fluidic conditions [28]. |

| Reference Glucose Analyzer (e.g., YSI Stat) | Provides high-precision reference measurements for blood glucose levels against which CGM sensor accuracy is calibrated and validated [28] [29]. | Used for calibrating sensors during in vitro tests and for verifying glucose levels during clamp studies [28] [29]. |

| Macrofluidic Test Bench | A custom housing that provides a stable fluidic environment for testing multiple CGM sensors in parallel in vitro [28]. | Used for standardized interference testing, allowing for controlled flow rates and sensor placement [28]. |

| Glucose Clamp Equipment | A method to maintain blood glucose at a specified level through variable dextrose infusion, based on frequent blood measurements [29]. | Creates a highly standardized metabolic challenge to quantify individual physiological responses under fixed conditions [29]. |

| Indirect Calorimetry Metabolic Cart | Measures oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production to determine resting energy expenditure and fuel utilization (respiratory exchange ratio) [29]. | Provides complementary metabolic data during glycemic challenges to understand underlying energy substrate use. |

| Sympathetic Microneurography Setup | Directly records sympathetic nerve activity directed to muscle beds, a measure of neural output from the brain [29]. | Used to investigate neural contributions to individual glycemic variability, particularly during induced hypoglycemia. |

Advanced Analytics and CGM Endpoints in Clinical Research and Trials

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) generates dense, time-series data, providing an unparalleled view of glycemic dynamics. Traditional research and clinical practice often reduce these rich trajectories to scalar summaries, such as the 2-hour area under the curve (AUC) or peak glucose [30] [15]. While useful, these summaries inevitably discard critical temporal information, potentially overlooking when and how dietary components exert their effects. This application note details how Multilevel Functional Data Analysis (FDA) addresses this limitation, preserving the full, continuous nature of postprandial glucose responses (PPGRs) to yield deeper biological insights. Framed within a broader thesis on CGM and food intake correlation, this protocol provides a practical guide for researchers aiming to implement these advanced analytical techniques in nutritional studies and drug development.

Application Notes: Insights from FDA of the AEGIS Data

Applying multilevel FDA to data from the A Estrada Glycation and Inflammation Study (AEGIS) reveals nuanced physiological responses that scalar metrics cannot capture [30] [15]. The core advantage of FDA is its ability to model how dietary effects evolve over the entire postprandial window.

Table 1: Temporal Effects of Dietary Components on Postprandial Glucose Trajectories

| Dietary Component | Effect on Glucose Trajectory | Timing of Maximum Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber | Blunts (reduces) the glucose response | After 90 minutes [15] |

| Fats | Reduces the early glucose rise | Within 50 minutes [15] |

| Fruit Component | Induces a higher initial glycemic peak, followed by a subsequent glucose-lowering effect | Peak at initial phase, lowering thereafter [31] |

| Alcohol Component | Associated with an initial hypoglycemic effect | Early postprandial phase [31] |

| Large Meals (High Starch/Dairy) | Significantly higher glucose levels throughout the 6-hour window | Entire 6-hour period [31] |

Furthermore, FDA effectively partitions variability in glucose responses. Analyses show that individuals with prediabetes exhibit greater day-to-day fluctuations in their postprandial trajectories compared to their normoglycemic counterparts, who display more consistent, subject-specific trends [30] [15]. This stratification of variability is crucial for identifying metabolic phenotypes and personalizing interventions.

Table 2: Subject Characteristics in the AEGIS Cohort (FDA Analysis Subset)

| Variable | Normoglycemic (N=319) | Prediabetes (N=58) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.6 (13.7) | 58.7 (12.0) |

| Weight (kg) | 73.7 (14.3) | 83.0 (19.6) |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.25 (0.25) | 5.86 (0.20) |

| Dinner Carbs (g) | 59.9 (40.5) | 53.7 (37.5) |

| Dinner Fats (g) | 30.1 (23.8) | 25.7 (22.3) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CGM Data Collection and Preprocessing for FDA

Objective: To collect high-quality, time-matched CGM and meal data suitable for multilevel functional analysis. Background: CGM devices measure interstitial glucose every few minutes, creating a dense, smooth, and hierarchical functional output [30] [32].

Materials:

- Real-time or professional CGM systems (e.g., Enlite sensor with iPro recorder).

- Standardized protocols for meal logging (e.g., dietitian-assisted reconstruction).

- Computing environment with FDA capabilities (e.g., R with

fdapace,refundpackages).

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Fit participants with a CGM sensor. For blinded studies, use professional CGM; for interventional studies, real-time CGM is appropriate.

- Meal Recording: Instruct participants to record all food and drink intake, including precise timing and detailed description of portion sizes. For "dinner" analysis, ensure consistent meal type labeling.

- Data Collection: Collect data over a period sufficient to capture multiple meals per individual (e.g., 6-7 days).

- Data Extraction:

- For each recorded meal, extract the CGM data for a defined postprandial window (e.g., 6 hours) starting from the reported mealtime.

- Compile individual-level covariates (e.g., age, BMI, HbA1c) and meal-level covariates (e.g., grams of carbohydrates, fats, protein, fiber).

- Trajectory Alignment: Align all extracted postprandial trajectories to a common time scale (t=0 at meal start). This creates the fundamental unit of analysis: a set of smooth glucose curves.

Protocol: Implementing Multilevel Functional Principal Component Analysis (MFPCA)

Objective: To identify and characterize the dominant modes of variability in the hierarchical postprandial glucose data. Background: MFPCA decomposes variation in the glucose curves into between-subject and within-subject (meal-to-meal) components, revealing major patterns of response [30].

Procedure:

- Smoothing: Smooth the raw, discrete CGM measurements for each meal trajectory to create continuous functions using basis functions (e.g., B-splines).

- Covariance Estimation: Estimate the covariance structure of the curves at two levels:

- Between-Subject Covariance: Captures variability in average response curves between different individuals.

- Within-Subject Covariance: Captures variability between different meals within the same individual.

- Eigenanalysis: Perform eigenanalysis on the estimated covariance operators to obtain functional principal components (FPCs) at each level.

- Level 1 FPCs: Represent the main patterns of variation from meal to meal within a person.

- Level 2 FPCs: Represent the main patterns of variation between different people.

- Interpretation: Examine the FPCs to understand patterns of variability. For example, an FPC might represent a component of variability associated with the magnitude of the glucose peak, while another might be associated with the speed of decline.

Figure 1: MFPCA analysis workflow for hierarchical glucose data.

Protocol: Implementing Function-on-Scalar Regression (FoSR)

Objective: To model the relationship between scalar predictors (e.g., diet, patient characteristics) and the entire functional glucose response. Background: FoSR allows the effect of a predictor to vary over time, showing when a factor is significantly associated with the glucose trajectory [15].

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Construct a multilevel FoSR model. The model can be conceptually represented as:

Glucose_Curve(t) = β_Age(t)*Age + β_Carbs(t)*Carbs + ... + Z_subject(t) + ε(t)where eachβ(t)is a functional coefficient, andZ_subject(t)is a subject-specific random intercept function. - Coefficient Estimation: Estimate the functional coefficients

β(t)and their confidence bands. This reveals how the effect of a predictor (e.g., fiber) changes throughout the postprandial period. - Inference & R² Extension: Test the null hypothesis that

β(t) = 0for all time pointst. Calculate the extended functional R² metric to quantify the proportion of variance explained by the predictors in the model [15].

Figure 2: Logical flow of FoSR model from inputs to inference.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CGM-FDA Studies

| Item / Solution | Function / Application Note |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Provides high-frequency interstitial glucose measurements. Use research-grade devices for accuracy. The AEGIS study used Enlite sensors with iPro recorders [30]. |

| Structured Meal Logging Protocol | Ensures accurate and quantifiable dietary data. Requires dietitian support for reconstruction and nutrient estimation using standardized software (e.g., Dietowin) [32]. |

| Multilevel Functional PCA (MFPCA) | A statistical method implemented in R to decompose variability in hierarchical functional data, identifying dominant between- and within-subject variation patterns [30] [33]. |

| Function-on-Scalar Regression (FoSR) | A regression framework that models an entire curve (output) against scalar inputs (e.g., nutrient grams). It is key for identifying time-varying associations [30] [15]. |

| Functional R² Metric | An extension of the standard R² to quantify the explanatory power of predictors on functional outcomes, critical for model selection in FoSR [15]. |

Core Glycemic Metrics and Their Clinical Significance

The interpretation of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) data relies on a standardized set of glycemic metrics that provide a comprehensive picture of glucose control beyond traditional measures like HbA1c. These metrics address HbA1c's limitations by capturing glucose variability, hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia that would otherwise go undetected [34].

Table 1: International Consensus on Core CGM Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Clinical Target (Most Adults) | Interpretation & Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Range (TIR) | Percentage of time glucose is between 70 and 180 mg/dL [35] [34] | ≥70% [35] [34] | Strongly associated with reduced risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications [34]. Represents daily time spent in the target zone. |

| Time Below Range (TBR) | Percentage of time glucose is <70 mg/dL (Level 1) and <54 mg/dL (Level 2) [34] | <4% (<70 mg/dL); <1% (<54 mg/dL) [34] | Key safety metric. Quantifies hypoglycemia risk, which is critical for treatment adjustments [34]. |

| Time Above Range (TAR) | Percentage of time glucose is >180 mg/dL (Level 1) and >250 mg/dL (Level 2) [34] | <25% (>180 mg/dL); <5% (>250 mg/dL) [34] | Reflects hyperglycemia burden and long-term complication risk [34]. |

| Mean Glucose | The average glucose value over the monitoring period [34] | N/A | Provides a quick summary of overall control but lacks detail on highs/lows [34]. |

| Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) | An estimate of A1C (%) based on mean CGM glucose [34] | N/A | Helps bridge CGM data with lab A1C. Discrepancies can indicate high variability or hemoglobin issues [34]. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Measure of glucose variability (Standard Deviation/Mean Glucose) [34] | ≤36% [34] | Predictor of hypoglycemia risk. Indicates glucose stability; lower values mean steadier control [34]. |

These metrics form the foundation for a modern, dynamic approach to diabetes management, enabling clinicians and researchers to assess safety, stability, and progress toward individualized goals [34].

Advanced Analytical Frameworks: CGM Data Analysis 2.0

While traditional summary statistics (CGM Data Analysis 1.0) are practically useful, they can oversimplify complex glucose patterns. The field is now advancing towards "CGM Data Analysis 2.0," which uses more sophisticated methods to extract deeper insights from dense time-series data [36].

Table 2: Evolution of CGM Data Analysis Methods

| Feature | Traditional Statistical Analysis (CGM 1.0) | Functional Data Analysis (FDA) | Machine Learning (ML) & Artificial Intelligence (AI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Visual inspection and summary statistics [36] | Statistical modeling of the entire CGM time series as a dynamic curve [36] | Predictive modeling and pattern classification using advanced algorithms [36] |

| Data Used | Aggregated metrics (e.g., TIR, mean glucose) [36] | Each complete CGM trajectory treated as a mathematical function [36] | Large CGM datasets, often combined with other data (EHR, lifestyle) [36] |

| Primary Purpose | Identify obvious trends and patterns for clinical use [36] | Quantify and model complex temporal dynamics and phenotypes [36] | Predict future glucose levels, classify metabolic subphenotypes, and optimize therapy automatically [36] |

| Key Insight | The shape of the glucose curve reflects underlying pathophysiology and patient behaviors [36] | FDA outperforms traditional methods by modeling glucose as a dynamic process, revealing patterns like weekday-weekend differences [36] | ML/AI can integrate CGM data with other parameters for real-time, adaptive interventions, such as in closed-loop systems [36] |

Furthermore, research is identifying independent components of glucose dynamics that may have distinct clinical implications. A 2025 study proposed that value (average glucose levels), variability (fluctuations), and autocorrelation (the degree to which subsequent glucose readings are predictable from previous ones) are three independent factors, with autocorrelation being a novel predictor of coronary plaque vulnerability [37]. The relationship between these components and their clinical implications can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Protocols for Food Intake Correlation Research

Correlating CGM metrics with food intake requires meticulous experimental design to isolate the effect of nutrition from other confounding variables. The following protocol provides a framework for such investigations.

Protocol: Assessing Individual Glycemic Response to Food

Objective: To quantify the impact of specific foods or meals on glycemic parameters (TIR, TAR, glucose spikes) in a target population (e.g., individuals with Type 2 Diabetes).

Materials & Reagents:

- CGM Devices: Real-time CGM sensors (e.g., Dexcom G7) with a minimum wear time of 14 days and ≥70% data availability [14] [34].

- Standardized Test Meals: Precisely formulated meals with known macronutrient composition. For carbohydrate-restricted diet (CRD) studies, "low-carbohydrate" is defined as ≤45% of total energy and "very-low-carbohydrate" as <26% [38].

- Data Platform: Software capable of generating Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) reports and exporting high-resolution time-series data [36].

- Dietary Log: A digital or paper-based tool for participants to meticulously record food type, quantity, and timestamps.

Procedure:

- Baseline Period (3-5 days): Participants wear CGM and log all food intake without any dietary intervention. This establishes individual baseline glucose patterns (mean glucose, CV, TIR).

- Intervention Period (≥6 weeks): Participants adhere to the prescribed dietary intervention (e.g., CRD) [38]. The duration should be sufficient to detect meaningful trends, as longer interventions may show greater benefits [38].

- Meal Challenge Tests (Optional): At predetermined points, participants consume a standardized test meal. CGM data is analyzed for the 3-hour postprandial period to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) and peak glucose value.

- Data Integration: Synchronize CGM data timestamps with dietary log entries.

- Outcome Analysis:

- Calculate primary outcomes: Change in 24-hour mean blood glucose and TIR from baseline to end-of-study [38] [39].

- Analyze secondary outcomes: Change in TAR, TBR, CV, and fasting glucose [39].

- For meal-specific analysis, aggregate glucose responses to similar meal types to identify personal triggers.

This experimental workflow, from participant recruitment to data analysis, is outlined below:

Nutrition-Focused Approach (NFA) for CGM Initiation

Qualitative research suggests that pairing CGM initiation with evidence-based nutrition guidance improves user engagement and leads to positive behavior changes [14]. A proposed 2-session intervention can be implemented as follows:

Session 1 (In-Person Initiation, 60 minutes):

- CGM Application: Apply sensor and train on device operation (scanning, app use).

- Set Glucose Goals: Explain target range (70-180 mg/dL) and the objective of >70% TIR [14].

- Introduce the "1, 2, 3 Approach":

- Check glucose before a meal.

- Check glucose 2 hours after a meal.

- Learn how your body responds to different foods and portions [14].

- Provide "Yes/Less" Framework: Use simple visual aids to guide food choices toward non-starchy vegetables and reduce foods with added sugars, aligning with evidence-based nutrition [14].

Session 2 (Remote Review, 30 minutes, ~14 days later):

- Review AGP Report: Discuss overall patterns in TIR, TAR, and TBR.

- Identify Personal Triggers: Use daily graphs to correlate high glucose excursions with specific meals or activities.

- Empower Discovery Learning: Support participants in deriving their own insights from the data to promote sustainable behavior change [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CGM-Food Correlation Research

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Real-time CGM System | Continuous measurement of interstitial glucose every 5-15 minutes; provides the core time-series data. | Dexcom G7 [14]; Ensure devices have API access for raw data export. |

| Professional CGM | Blinded CGM for short-term observational studies where patient behavior should not be altered. | Often used in clinical settings for 1-2 week profiles. |

| Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) Report | Standardized visualization tool for summarizing 14 days of CGM data into a single, interpretable 24-hour profile [36]. | Key for clinical interpretation and identifying temporal patterns [36]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Platform for advanced statistical analysis, Functional Data Analysis, and machine learning modeling. | SAS, STATA, R, Python; Custom scripts for FDA and ML [40] [38] [36]. |

| Structured Dietary Intervention | A controlled diet to test a specific hypothesis regarding macronutrients (e.g., CRDs) on glycemic outcomes. | Meals should be fully provided or closely monitored [38]. "Low-carbohydrate" is ≤45% total energy [38]. |

| Digital Dietary Logging App | For precise tracking of food intake, portion sizes, and meal timings to correlate with CGM traces. | Critical for ensuring data synchronization and accuracy in free-living studies. |

The design of clinical trials for metabolic therapies and nutritional interventions is undergoing a significant transformation, moving beyond the traditional reliance on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has emerged as a powerful technology providing unprecedented granularity in capturing glycemic dynamics [41]. This paradigm shift is particularly relevant for research investigating the correlation between food intake and glycemic response, where CGM endpoints offer a nuanced understanding of how dietary interventions affect glucose metabolism in real-world settings.

The adoption of CGM in clinical research has accelerated substantially following international standardization efforts, with time in range (TIR) emerging as a particularly valuable endpoint that complements or potentially supplants HbA1c in certain trial designs [41] [42]. For researchers investigating food intake correlations, CGM provides the temporal resolution necessary to link specific dietary exposures to postprandial glycemic responses, enabling more precise quantification of nutritional interventions [10]. This application note examines the trends in CGM adoption as a primary endpoint in clinical trials and provides detailed experimental protocols for implementing CGM in studies focused on food intake correlation research.

Quantitative Analysis of CGM Adoption Trends

Analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov Data

A comprehensive analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov records from 2012 to 2023 reveals a significant expansion in the use of CGM endpoints in clinical research [41]. The data, summarized in Table 1, demonstrates striking growth patterns across study phases, populations, and funding sources when comparing the six-year periods before and after the publication of the first international CGM consensus guidelines in 2017.

Table 1: Adoption Trends of CGM Endpoints in Clinical Trials (2012-2023)

| Category | Period 1 (2012-2017) | Period 2 (2018-2023) | Change | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Studies | 121 | 194 | +60.3% | <0.01 |

| Phase 2 Studies | 31 | 70 | +125.8% | <0.01 |

| Phase 3 Studies | 13 | 35 | +169.2% | <0.01 |

| Adult-Only Population | 109 | 153 | +40.4% | 0.05 |

| Pediatric-Inclusive Population | 12 | 41 | +241.7% | <0.01 |

| Industry-Funded Studies | 37 | 66 | +78.4% | <0.05 |

| Non-Industry-Funded Studies | 60 | 108 | +80.0% | <0.01 |

| Studies with TIR as Endpoint | 13 | 42 | +222.4% | <0.01 |

| Studies with MAGE as Endpoint | 14 | 4 | -71.3% | <0.01 |

The data reveals several noteworthy trends. First, the overall adoption of CGM endpoints increased significantly (60.3%) in the period following guideline standardization, with particularly dramatic growth in Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials [41]. Second, while adult populations continue to dominate clinical research, studies including pediatric populations have increased substantially (241.7%), indicating expanding application of CGM across patient demographics [41]. Third, the adoption of CGM has been driven by both industry and non-industry sponsors, with both categories showing similar robust growth (78.4% and 80.0%, respectively) [41].

Perhaps most notably, the analysis reveals a dramatic shift in the specific CGM metrics preferred by researchers. The use of time in range (TIR) as an endpoint increased by 222.4%, while the use of mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE) decreased by 71.3% [41]. This shift reflects the research community's alignment with internationally standardized metrics that have demonstrated clinical relevance and correlation with long-term outcomes [42].

CGM Endpoint Adoption Across Indications

The application of CGM endpoints has expanded beyond traditional diabetes populations. While studies of type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) increased by 55.8% and 26.9%, respectively, studies of non-diabetes indications increased by a remarkable 233.3% in the post-2018 period [41]. This expansion reflects growing recognition of the role glycemic variability plays in various metabolic conditions and the utility of CGM in assessing nutritional and therapeutic interventions across diverse populations.

For research correlating food intake with glycemic response, this expansion is particularly significant, as CGM enables researchers to study glucose dynamics in non-diabetic populations, including those with prediabetes, obesity, or other metabolic risk factors [10] [43]. The ability to capture subtle glycemic variations in response to dietary interventions in these populations provides valuable insights for preventive strategies and early interventions.

Standardized CGM Metrics and Endpoints for Clinical Research

Internationally Consensus-Endorsed Metrics

The international consensus statement on CGM metrics for clinical trials provides clear recommendations for standardized data collection and reporting [42]. These recommendations have been endorsed by major professional organizations including the American Diabetes Association, European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and several other international bodies. The consensus emphasizes that CGM data should be collected using devices with adequate accuracy and that studies should report specific core metrics to enhance comparability across trials.

Table 2: Standardized CGM Metrics for Clinical Trials of Dietary Interventions

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Target/Definition | Relevance to Food Intake Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Ranges | Time in Range (TIR) | 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L) | Primary endpoint for overall dietary efficacy |

| Time Above Range (TAR) | >180 mg/dL (>10.0 mmol/L) | Identifies hyperglycemic responses to meals | |

| Time Below Range (TBR) | <70 mg/dL (<3.9 mmol/L) | Safety metric for aggressive interventions | |

| Glycemic Variability | Coefficient of Variation (CV) | ≤36% | Measure of glucose stability throughout day |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | Individualized | Absolute measure of glucose fluctuations | |

| Acute Response Metrics | Area Under Curve (AUC) | 0-4 hours postprandial | Quantifies total glycemic impact of meals |

| Glucose Excursion | Peak - baseline amplitude | Measures magnitude of postprandial spike | |

| Time to Peak (TTP) | Time from meal to maximum glucose | Kinetics of glucose absorption | |

| Glucose Recovery Time to Baseline (GRTB) | Time to return to pre-meal levels | New metric for metabolic resilience [43] |

For food intake correlation research, the consensus recommends capturing meal-related data through standardized time-blocks (e.g., 3-4 hour postprandial windows) and using appropriate metrics such as area under the curve (AUC) and glucose excursion to quantify meal-related glycemic responses [42]. The emerging metric of Glucose Recovery Time to Baseline (GRTB) shows particular promise for assessing metabolic resilience in response to dietary challenges [43].

Advanced Metrics for Nutritional Research

Beyond the core metrics, specialized CGM-derived parameters offer additional insights for food intake correlation studies:

- Postprandial Glucose Response: Defined as the incremental AUC over a 2-4 hour period following meal consumption [10]. This metric directly quantifies the glycemic impact of specific foods or meals.

- Meal Glucose Response Profile: A comprehensive assessment including time to peak, peak glucose value, and recovery time to baseline [43]. This provides kinetic information about glucose metabolism following food intake.

- Inter-day Variability: Assesses consistency of glycemic responses to similar meals across different days, which may reflect underlying metabolic flexibility [10].

These advanced metrics enable researchers to move beyond simple averages and capture the dynamic nature of glycemic responses to dietary interventions, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how specific nutritional approaches affect glucose metabolism.

Experimental Protocols for CGM in Food Intake Research

Core Protocol for CGM Deployment and Data Collection

Objective: To establish standardized methodology for deploying CGM systems in clinical trials investigating correlations between food intake and glycemic responses.

Materials:

- Factory-calibrated CGM systems (e.g., FreeStyle Libre, Dexcom G6/G7, Medtronic Guardian)

- Data extraction software/cloud platforms

- Standardized data collection forms for meal timing and composition

- Adhesive overlays or securement devices as needed

Procedure:

- Sensor Placement: Apply CGM sensor to posterior upper arm or abdomen according to manufacturer instructions, ensuring proper adhesion and site rotation from previous placements.

- Run-in Period: Allow a minimum 2-hour sensor warm-up period followed by a 24-hour run-in period before formal data collection to ensure sensor stability [44].

- Data Collection Period: Maintain continuous CGM wear for a minimum of 14 days to capture adequate data for meaningful pattern analysis [45]. For nutritional interventions, extend collection to cover the entire intervention period plus baseline.

- Meal Documentation: Implement precise meal documentation including:

- Exact meal start time

- Detailed food composition (weighed or estimated using standardized methods)

- Macronutrient content (carbohydrate, protein, fat grams)

- Glycemic load calculation where applicable

- Data Extraction: Download CGM data at least weekly during extended trials and at study conclusion using manufacturer-specific software.

- Data Quality Assessment: Verify that CGM active time exceeds 70% during each analysis period [45]. Exclude periods of sensor failure or extended calibration.

Endpoint Calculation:

- Calculate primary endpoints (e.g., TIR, mean glucose) over the entire study period for overall intervention effects

- Calculate meal-specific endpoints (e.g., postprandial AUC, glucose excursion) for individual meal responses

- Perform subgroup analyses by time of day (nocturnal vs. daytime) where relevant to research question

Specialized Protocol for Controlled Meal Challenges

Objective: To assess glycemic responses to standardized test meals under controlled conditions, eliminating variability in meal composition and timing.

Materials:

- CGM systems as above

- Standardized test meals with precisely controlled macronutrient composition

- Food scales and preparation facilities

- Activity monitors to control for physical activity confounding

Procedure:

- Baseline Period: Collect 3 days of baseline CGM data with ad libitum diet to establish individual glycemic patterns.

- Test Meal Preparation: Prepare standardized test meals with identical composition, portion size, and presentation for all participants. Macronutrient composition should be verified by laboratory analysis where possible.

- Test Meal Administration: Administer test meals after an overnight fast of 10-12 hours, with meal consumption completed within 15 minutes.

- Postprandial Monitoring: Collect CGM data for a minimum of 4 hours postprandially with participants remaining in a controlled setting with limited physical activity.

- Comparison Meals: Utilize crossover design where participants receive different test meals on separate days in randomized order.

- Data Analysis: Calculate postprandial metrics including AUC, peak glucose, time to peak, and glucose recovery time to baseline.

Endpoint Calculation:

- Primary: Incremental AUC (0-4 hours) for comparison between test meals

- Secondary: Peak glucose concentration, time to peak, and glucose recovery time to baseline

- Exploratory: Glycemic variability metrics during postprandial period

This protocol was successfully implemented in the CGM-HYPE study, which demonstrated significant differences in glucose responses to various dietary challenges in healthy young adults [43].

Protocol for Free-Living Food Intake Correlation Studies

Objective: To correlate CGM data with self-selected food intake under free-living conditions, capturing real-world dietary behaviors.

Materials:

- CGM systems as above

- Digital food diary application or structured paper food records

- Food photography aids (standard reference objects) if using photographic documentation

- Carbohydrate counting references

Procedure:

- Participant Training: Train participants in detailed food recording using chosen methodology, emphasizing portion size estimation and timing accuracy.

- Data Collection Period: Implement simultaneous CGM wear and food recording for a minimum of 10 days to capture variability across different days [10].

- Food Recording Methodology:

- Record all food and beverages consumed with precise timing

- Estimate portion sizes using household measures or food scales

- Document macronutrient composition using food database or nutrition labels

- Include description of food preparation methods

- Data Synchronization: Time-synchronize CGM data with food intake records using standardized time stamps.

- Meal Identification: Define postprandial windows (typically 2-4 hours) following each eating occasion.

- Statistical Correlation: Apply linear mixed models to account for repeated measures within individuals when correlating dietary components with glycemic responses.

Analytical Approach:

- Calculate correlation coefficients between dietary parameters (glycemic load, carbohydrate content) and CGM metrics (postprandial AUC, peak glucose)

- Develop prediction models for glycemic response based on meal composition

- Assess inter-individual variability in responses to similar meals

This approach was validated in a 2025 study that demonstrated moderate correlations between glycemic load and CGM metrics including area under the curve, standard deviation, and variance in healthy adults [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for CGM Food Intake Correlation Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Research Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGM Systems | Factory-calibrated CGM (Dexcom G7, FreeStyle Libre 3) | Continuous glucose data collection | Select based on accuracy requirements, connectivity needs, and wear duration |

| Data Acquisition | CGM proprietary software, Cloud data platforms, API interfaces | Raw data extraction and storage | Ensure compatibility with data management plan and regulatory requirements |

| Dietary Assessment | Digital food diaries, Food scale, Photographic aids, Nutrient database | Precise documentation of food intake | Standardize methodology across all study participants and sites |

| Meal Standardization | Test meal ingredients, Food preparation facilities, Packaging materials | Controlled meal challenges | Maintain consistency in composition, preparation, and presentation |

| Reference Analytics | HbA1c point-of-care devices, Laboratory HbA1c services, Standardized laboratories | Validation against traditional endpoints | Schedule collections to align with CGM wear periods |

| Data Analysis | Statistical software (R, SAS, Python), Custom scripts for CGM metrics, Data visualization tools | Endpoint calculation and visualization | Pre-specify analytical approach in statistical analysis plan |

Implementation Framework and Multidisciplinary Considerations

Successful implementation of CGM endpoints in clinical trials requires careful attention to operational considerations. A pilot implementation study demonstrated the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary approach involving primary care physicians, certified diabetes care and education specialists, and clinical pharmacists [46]. This model improved patient access to CGM technology and enhanced the interpretation of CGM data in clinical practice, with significant improvements in time in range and HbA1c outcomes [46].

For nutritional research specifically, incorporating a nutrition-focused approach during CGM initiation has shown positive results. Qualitative research revealed that participants who received nutrition-focused CGM initiation materials were better able to make food-related decisions aligned with evidence-based nutrition recommendations [14]. This approach emphasized simple frameworks such as monitoring glucose before and after meals and adjusting food choices using a "yes/less" framework for healthier options [14].

The integration of CGM into clinical trials of dietary interventions represents a significant advancement in nutritional science, providing objective, continuous data on glycemic responses to food intake. By implementing standardized protocols and metrics, researchers can generate comparable, high-quality evidence regarding the effects of nutritional interventions on glucose metabolism across diverse populations.

Linking Meal Composition and Timing to Continuous Glucose Profiles