Engineering Functional Food Matrices with Bioactive Compounds: From Molecular Design to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the integration of bioactive compounds into functional food matrices.

Engineering Functional Food Matrices with Bioactive Compounds: From Molecular Design to Clinical Translation

Abstract

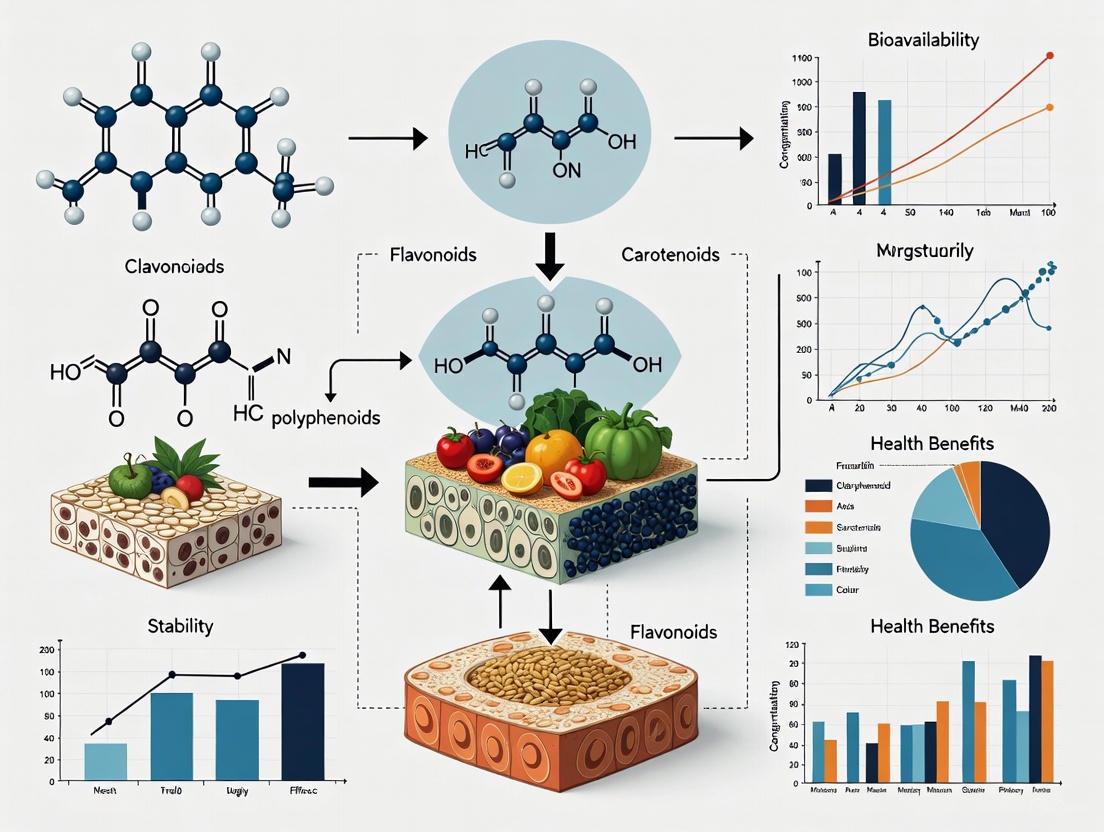

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the integration of bioactive compounds into functional food matrices. It covers the foundational science of key bioactive classes (polyphenols, carotenoids, omega-3s, probiotics) and their health mechanisms, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gut-modulating effects. The scope extends to advanced extraction, isolation, and characterization techniques, alongside innovative encapsulation and food matrix engineering strategies to enhance stability and bioavailability. It further addresses critical challenges in optimization, scaling, and regulatory compliance, and details robust validation methodologies from in vitro models to clinical trials. By synthesizing current research and technological advances, this review aims to bridge the gap between food science and pharmaceutical development for creating efficacious, evidence-based functional foods.

Bioactive Compounds Unveiled: Sources, Classifications, and Mechanisms of Action

Bioactive compounds (BCs) are natural or synthetic substances with the capacity to interact with one or more components of living tissues, exerting a wide range of beneficial effects that extend beyond basic nutrition [1]. While not considered essential nutrients like vitamins or minerals, these compounds exert regulatory effects on physiological processes and contribute significantly to improved health outcomes [2]. The concept of food has fundamentally evolved from simply providing energy and basic nutrients to serving as a proactive factor in promoting health and preventing chronic diseases, positioning bioactive compounds at the forefront of functional food development and nutritional therapeutics [2].

The growing scientific interest in bioactive compounds is driven by converging trends: consumer demand for "clean label" products containing natural ingredients, public health initiatives focused on preventive nutrition, and substantial evidence supporting their therapeutic potential against chronic diseases [1] [2] [3]. This paradigm shift has transformed how researchers, food scientists, and drug development professionals approach the isolation, characterization, and application of these compounds in functional food matrices and therapeutic formulations.

Bioactive compounds in functional foods constitute a broad and chemically diverse group of natural substances derived from plant, animal, and microbial sources. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of major bioactive compound classes, their natural sources, and key health benefits.

Table 1: Major Classes of Bioactive Compounds, Sources, and Health Benefits

| Compound Class | Examples | Major Food Sources | Key Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | Flavonoids, Phenolic Acids, Lignans, Stilbenes | Berries, apples, onions, green tea, coffee, whole grains, flaxseeds, red wine | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular protection, neuroprotection [4] |

| Carotenoids | Beta-carotene, Lutein | Carrots, sweet potatoes, spinach, mangoes, kale, corn | Provitamin A activity, vision support, immune function, skin health [4] |

| Bioactive Peptides | Lactoferrin, Casein-derived peptides | Dairy products, meat, fish | Antihypertensive, antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, mineral-binding [2] |

| Organosulfur Compounds | Allicin, Glucosinolates | Garlic, onions, cruciferous vegetables | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, detoxification support [2] |

| Dietary Fibers | Resistant starch, Insoluble fiber | Whole grains, green banana, pineapple, legumes | Gut health promotion, microbiota modulation, bowel regularity [5] |

Agro-food waste has emerged as a particularly valuable and sustainable source of bioactive compounds. Recent studies reveal that numerous food wastes, particularly fruit and vegetable byproducts, contain high concentrations of valuable compounds that can be extracted and reintroduced into the food chain [1]. The transition to a circular economy model emphasizes the valorization of these waste streams, transforming them from environmental challenges into valuable resources for functional food development [1].

Analytical Framework: Isolation and Characterization Protocols

Extraction Methodologies

The initial critical step in bioactive compound analysis is extraction, which must be carefully optimized to preserve compound integrity while maximizing yield. The selection of solvent system largely depends on the specific nature of the bioactive compound being targeted [6].

Protocol 3.1.1: Conventional Solvent Extraction

- Sample Preparation: Pre-wash plant materials, freeze-dry, and grind to obtain a homogeneous sample [6].

- Solvent Selection: For hydrophilic compounds, use polar solvents (methanol, ethanol, ethyl-acetate). For lipophilic compounds, use dichloromethane or dichloromethane/methanol (1:1 ratio) [6].

- Extraction Technique:

- Solvent Removal: Concentrate extracts under reduced pressure using rotary evaporation.

Protocol 3.1.2: Advanced Green Extraction Technologies

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Combine plant material with solvent in specialized microwave vessels. Apply controlled microwave energy (typically 500-1000W) with temperature monitoring [1] [2].

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Suspend sample in appropriate solvent. Apply ultrasonic waves (20-40 kHz) for 15-60 minutes with temperature control [1] [2].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Utilize CO₂ as supercritical fluid. Set parameters: pressure (150-450 bar), temperature (40-80°C), and modifier concentration (0-20% ethanol) [6] [1].

Separation and Characterization Techniques

Following extraction, sophisticated chromatographic and spectroscopic methods are employed for separation and identification of target compounds.

Protocol 3.2.1: Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) and Bioautography

- TLC Plate Preparation: Use silica gel GF254 plates (0.25 mm thickness for analytical, 1 mm for preparative) [6].

- Sample Application: Apply test solutions as discrete spots 1.5 cm from bottom edge.

- Chromatographic Development: Develop in appropriate solvent system in saturated chamber until solvent front reaches 0.5-1 cm from top.

- Visualization: Examine under UV light (254 nm and 365 nm) and spray with specific detection reagents [6].

- Bioautography (for antimicrobial screening):

- Direct Bioautography: Apply microbial suspension directly to developed TLC plate and incubate [6].

- Agar Overlay: Apply seeded agar medium directly onto TLC plate, incubate, and visualize inhibition zones [6].

- Inhibition Zone Analysis: Scrape active zones from preparative TLC for further purification.

Protocol 3.2.2: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC/UPLC) Analysis

- Instrument Setup: Utilize C18 reverse-phase column (e.g., 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm for UPLC). Mobile phase: gradient of water (0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile/methanol [7].

- Detection: Employ diode array detector (DAD) scanning 200-600 nm and mass spectrometric detection [7].

- Quantification: Use external standard method with calibration curves of reference compounds [7].

Protocol 3.2.3: Mass Spectrometric Characterization

- UPLC-QTOF-MS Analysis:

- Data Processing: Use software (e.g., UNIFI, Waters) for compound identification by comparing exact mass, isotopic pattern, and fragmentation spectra with databases [7].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for bioactive compound analysis from extraction to application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research on bioactive compounds requires specific reagents, reference standards, and specialized materials. Table 2 details essential research reagent solutions for experimental work in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Research

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | C18 reverse-phase (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) | UPLC separation of complex extracts [7] |

| Reference Standards | ≥95% purity (e.g., quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnoside, amentoflavone) | Method validation and compound quantification [7] |

| Mass Spectrometry Solvents | LC-MS grade water, acetonitrile, methanol | Mobile phase preparation for MS compatibility [7] |

| TLC Plates | Silica gel GF254, 0.25 mm (analytical), 1 mm (preparative) | Initial screening and bioautography [6] |

| Cell Culture Media | Mueller-Hinton agar, RPMI-1640 | Antimicrobial and cytotoxicity assays [7] |

| Encapsulation Polymers | Sodium alginate, chitosan, gum Arabic | Nano/microencapsulation for stability and bioavailability [8] |

| Solvents for Extraction | HPLC grade methanol, ethanol, dichloromethane | Compound extraction with minimal interference [6] |

Functionalization Strategies: Enhancing Bioavailability and Stability

A significant challenge in utilizing bioactive compounds is their limited bioavailability, chemical instability, and susceptibility to gastrointestinal degradation. Advanced functionalization strategies have been developed to overcome these limitations.

Nanoencapsulation Protocols

Protocol 5.1.1: Ionic Gelation for Polysaccharide-Based Nanoparticles

- Polymer Solution: Dissolve chitosan (1.0-2.0 mg/mL) in aqueous acetic acid (1% v/v) [8].

- Bioactive Loading: Incorporate bioactive compound (0.1-0.5 mg/mL) into polymer solution under magnetic stirring.

- Cross-linking: Add tripolyphosphate solution (0.5-1.0 mg/mL) dropwise using a syringe pump (flow rate 0.5 mL/min).

- Nanoparticle Formation: Stir for 60 minutes at room temperature to allow nanoparticle formation.

- Purification: Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 30 minutes and resuspend in buffer [8].

Protocol 5.1.2: Spray Drying Encapsulation

- Wall Material Preparation: Prepare wall material solution (10-20% w/v maltodextrin/gum Arabic blend) [8].

- Core Material Addition: Add bioactive compound to wall material solution (core-to-wall ratio 1:4).

- Homogenization: Homogenize mixture at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Spray Drying Parameters: Inlet temperature 160-180°C, outlet temperature 80-90°C, feed flow rate 5 mL/min [8].

- Product Collection: Collect encapsulated powder from cyclone separator and store in desiccator.

Diagram 2: Encapsulation strategies for enhancing bioactive compound performance in food matrices.

Application Notes: Incorporating Bioactive Compounds into Food Matrices

Successfully incorporating bioactive compounds into food products requires careful consideration of matrix compatibility, stability during processing, and maintaining bioactivity throughout shelf life.

Food Matrix Integration Protocol

Protocol 6.1.1: Evaluation of Matrix-Effect Interactions

- Compatibility Screening:

- Test bioactive incorporation in various matrices (dairy, bakery, beverage) at target concentration.

- Monitor for precipitation, phase separation, or color changes.

- Processing Stability:

- Subject fortified products to typical processing conditions (heat, shear, pH changes).

- Sample at intervals for bioactive compound quantification via HPLC.

- Shelf-Life Monitoring:

Functional Validation in Model Systems

Protocol 6.2.1: In Vitro Bioaccessibility Assessment

- Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion:

- Oral Phase: Incubate with simulated salivary fluid (2 min, pH 6.8).

- Gastric Phase: Add simulated gastric fluid with pepsin (2 h, pH 2.0, 37°C).

- Intestinal Phase: Add simulated intestinal fluid with pancreatin and bile (2 h, pH 7.0, 37°C) [5].

- Bioaccessibility Calculation:

- Centrifuge intestinal digest at 12,000 × g for 60 min.

- Quantify bioactive in supernatant (micellar fraction).

- Calculate bioaccessibility = (Csupernatant/Cinitial) × 100.

Concluding Remarks: Translational Perspectives for Research and Development

The field of bioactive compounds continues to evolve with significant implications for functional food development, nutritional science, and preventive medicine. The successful translation of research findings into practical applications requires interdisciplinary collaboration between food scientists, nutritionists, engineers, and healthcare professionals [2].

Future perspectives in the field include personalized nutrition approaches based on individual metabolic responses, AI-guided formulation to optimize synergistic interactions between bioactive compounds and food matrices, and omics-integrated validation to provide comprehensive understanding of mechanisms of action [2]. Continued advances in green extraction technologies, encapsulation delivery systems, and targeted release mechanisms will further enhance the efficacy and application scope of bioactive compounds in promoting human health and preventing chronic diseases [1] [8] [2].

As research progresses, standardization of analytical methods, clarification of regulatory frameworks, and comprehensive safety assessments will be crucial for building consumer confidence and realizing the full potential of bioactive compounds in the global food and health sectors [1] [4].

Application Note

This document provides a scientific overview of the major classes of bioactive compounds, detailing their natural sources, health benefits, and essential protocols for their isolation and analysis. It is structured to support research on the incorporation of these compounds into functional food matrices.

Bioactive compounds are dietary components that influence physiological or cellular activities in the organisms that consume them, conferring health benefits beyond basic nutrition. Their strategic incorporation into food matrices is a core focus in the development of functional foods aimed at preventing chronic diseases and promoting health. Key challenges in this field include ensuring the stability, bioavailability, and efficacy of these compounds within complex food systems. This note synthesizes current information on five major classes of bioactives—polyphenols, carotenoids, omega-3 fatty acids, probiotics, and prebiotics—to provide a foundational resource for research and development.

The following table summarizes the natural origins and primary documented health benefits of the major bioactive classes, which is critical for target-oriented research and development.

Table 1: Natural Sources and Key Health Benefits of Major Bioactive Compounds

| Bioactive Class | Major Natural Sources | Key Health Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | Fruits (berries, apples, grapes), vegetables (spinach, onions, kale), green tea, coffee, whole grains. | Potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities; cardiovascular protection; neuroprotection; potential anticancer properties. | [2] [4] |

| Carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene, lutein, lycopene) | Carrots, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, bell peppers, leafy greens (kale, spinach), corn, egg yolk. | Provitamin A activity (β-carotene); antioxidant properties; support for vision and eye health (lutein); immune function. | [9] [4] |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (e.g., ALA, EPA, DHA) | Chia seeds, flax seeds, linseeds, sesame seeds, fish oil, fatty fish. | Support cardiovascular health; anti-inflammatory effects; crucial for brain function and neuroprotection; modulate liver diseases. | [10] |

| Probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, S. boulardii) | Fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, cheese); also found in non-dairy fermented foods and as supplements. | Modulate gut microbiota; enhance immune response; improve digestive health; prevent/treat gastrointestinal infections. | [11] [12] |

| Prebiotics (e.g., Inulin, FOS, Resistant Starch) | Root and tuber crops (chicory, cassava, sweet potato, yam), whole grains, legumes. | Selectively stimulate growth of beneficial gut bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus); production of beneficial SCFAs; improve gut barrier function. | [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Analysis

Protocol: Extraction and HPLC Analysis of Carotenoids from Plant Matrices

Objective: To efficiently extract and accurately quantify major carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene, lutein, lycopene) from plant-based food samples.

Principle: Carotenoids are lipophilic pigments. This protocol uses an organic solvent system for extraction, followed by separation and quantification via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV-Vis detection, which is considered the gold standard for carotenoid analysis [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Samples: Fresh or freeze-dried plant tissue (e.g., carrot, spinach).

- Extraction Solvents: Acetone, Methanol, Hexane (HPLC grade).

- Quenching Agent: Saturated NaCl solution.

- HPLC Mobile Phase: Acetonitrile (ACN), Methanol (MeOH), Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE).

- HPLC System: Equipped with a UV-Vis Diode Array Detector (DAD).

- Analytical Column: Reversed-phase C18 or C30 column (e.g., YMC C30, 250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm) [9].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the plant sample under dim light to prevent photodegradation. Precisely weigh ~1 g of homogenate.

- Extraction:

- Add 10 mL of acetone:methanol (1:1, v/v) mixture to the sample in a centrifuge tube.

- Vortex vigorously for 2 minutes, then sonicate in a water bath for 15 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 5,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer the supernatant to a separating funnel.

- Repeat the extraction until the pellet becomes colorless.

- Partitioning:

- Add an equal volume of hexane and 10 mL of saturated NaCl solution to the combined supernatants in the separating funnel.

- Gently shake and allow phases to separate. Collect the upper organic layer containing the carotenoids.

- Evaporate the organic phase to dryness under a stream of nitrogen gas.

- HPLC Analysis:

- Reconstitution: Redissolve the dry extract in 1 mL of the HPLC mobile phase, filter through a 0.22 μm PTFE syringe filter, and transfer to an HPLC vial.

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Mobile Phase: A: ACN/MeOH (90:10, v/v), B: MTBE.

- Gradient: 0-5 min: 0% B; 5-40 min: 0-100% B; 40-45 min: 100% B.

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 25°C.

- Injection Volume: 20 μL.

- Detection: Monitor absorbance at 450 nm.

- Identification and Quantification: Identify carotenoids by comparing retention times and spectral data with authentic standards. Quantify using external calibration curves.

Protocol: Viability Assessment of Probiotics in a Food Matrix

Objective: To determine the survival and viability of probiotic strains incorporated into a functional food product (e.g., yogurt or a plant-based beverage) over time and under simulated gastrointestinal conditions.

Principle: Probiotic efficacy requires a sufficient number of viable cells to reach the intestines. This protocol involves plating serial dilutions of the sample on selective media to count colony-forming units (CFUs), the standard method for assessing viability [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Samples: Probiotic-fortified food product.

- Growth Media: de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar for lactobacilli; MRS agar supplemented with 0.05% L-cysteine for bifidobacteria.

- Diluent: Maximum Recovery Diluent (MRD) or sterile Peptone Water.

- Simulated Gastric Juice (SGJ): 0.3% (w/v) pepsin in sterile saline, pH adjusted to 2.0-3.0 with HCl.

- Simulated Intestinal Juice (SIJ): 0.1% (w/v) pancreatin in sterile saline, pH adjusted to 7.0-7.4 with NaHCO₃.

- Equipment: Anaerobic jar system, incubator, water bath, colony counter.

Procedure:

- Sample Homogenization: Aseptically weigh 10 g of the probiotic food product into 90 mL of sterile diluent and homogenize in a stomacher or by vortexing.

- Viability in Product (at time T):

- Prepare serial ten-fold dilutions of the homogenate.

- Spread plate 100 μL of appropriate dilutions (e.g., 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁸) onto duplicate plates of the selective agar.

- Incubate plates anaerobically at 37°C for 48-72 hours.

- Count colonies and calculate CFU/g of the original product.

- In Vitro Gastrointestinal Stress Tolerance:

- Gastric Phase: Mix 1 mL of the initial homogenate with 9 mL of pre-warmed SGJ. Incubate at 37°C in a shaking water bath (100 rpm) for 90 minutes.

- Intestinal Phase: Adjust the pH of the gastric digestate to 7.0 using sterile 1M NaHCO₃. Add an equal volume of pre-warmed SIJ and incubate for a further 120-180 minutes under the same conditions.

- Viability Assessment: After the intestinal phase, perform serial dilution and plate counting as in Step 2 to determine the survival rate.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the log reduction in viable count using the formula: Log (N₀/N), where N₀ is the initial count and N is the count after stress.

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

Carotenoid Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps involved in the extraction and analysis of carotenoids from a food matrix, as detailed in the protocol above.

Gut Microbiota Modulation by Pre/Probiotics

This diagram outlines the conceptual pathway through which prebiotics and probiotics exert their beneficial effects on gut health.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| C30 HPLC Column | High-resolution separation of carotenoid isomers and similar compounds. | Superior to C18 for separating geometric isomers [9]. |

| MRS Agar | Selective cultivation and enumeration of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. | Supplement with L-cysteine for improved growth of Bifidobacterium [11]. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | In vitro assessment of probiotic survival and bioactive compound bioavailability. | Contains pepsin (gastric) and pancreatin (intestinal) enzymes [11]. |

| Green Extraction Solvents | Sustainable extraction of bioactive compounds (e.g., polyphenols, carotenoids). | Ethyl acetate as a potential alternative to MTBE and ACN [2] [9]. |

| Encapsulation Materials (e.g., chitosan, maltodextrin) | Microencapsulation to enhance stability and bioavailability of sensitive bioactives like β-carotene and probiotics. | Protects against oxidation and gastrointestinal degradation [14] [15] [10]. |

The incorporation of bioactive compounds into food matrices represents a frontier in nutritional science and preventive medicine. These compounds, which include polyphenols, anthocyanins, and dietary fibers, exert significant health benefits primarily through three interconnected molecular pathways: antioxidant activities, anti-inflammatory effects, and modulation of the gut microbiota. Understanding these mechanisms provides a scientific foundation for developing functional foods with targeted health benefits.

Bioactive compounds from food by-products, such as grape pomace, olive leaves, and fruit peels, are enriched in polyphenols, dietary fibers, vitamins, and polyunsaturated fatty acids that would otherwise be wasted [16]. These components function synergistically to mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation, which are fundamental processes in the pathogenesis of numerous chronic diseases. The molecular interplay between these pathways creates a network of protection that maintains cellular homeostasis and promotes systemic health [16] [17].

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Antioxidant Signaling Pathways

Bioactive compounds combat oxidative stress through direct free radical scavenging and by activating the body's endogenous antioxidant defense system, primarily mediated by the Nrf2 pathway.

Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Activation: Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its inhibitor, Keap1. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) or bioactive compounds (such as falcarindiol from carrots) facilitate the dissociation of Keap1 from Nrf2 [16] [18]. This allows Nrf2 to translocate to the nucleus, where it binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), initiating the transcription of antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [16] [19]. This pathway is a crucial mechanism for cellular defense against oxidative damage.

Direct ROS Scavenging: Compounds like anthocyanins, vitamin C, and vitamin E directly neutralize reactive oxygen and nitrogen species through electron transfer, thereby preventing lipid peroxidation, protein damage, and DNA strand breaks [19] [17] [20]. The malondialdehyde (MDA) level is a key marker of lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage.

The following diagram illustrates the Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathway:

Table 1: Key Antioxidant Enzymes and Their Functions

| Enzyme | Function | Inducing Bioactive Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | Catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radical (O₂•⁻) into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide [16] | Grape pomace polyphenols, anthocyanins [16] [20] |

| Catalase (CAT) | Converts hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) into water and oxygen, preventing hydroxyl radical formation via Fenton reaction [16] [19] | Flavonoids, resveratrol [16] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX) | Reduces lipid hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide to their corresponding alcohols/water, using glutathione [16] | Quercetin, ferulic acid [16] |

| Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1) | Catalyzes heme degradation, producing antioxidants biliverdin and bilirubin [18] | Falcarinol, sulforaphane [18] |

Anti-inflammatory Signaling Pathways

Bioactive compounds target central inflammatory signaling hubs, predominantly the NF-kβ pathway, to reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators.

NF-kβ Pathway Inhibition: Inactive NF-kβ is localized in the cytoplasm bound to its inhibitor, IκB. Pro-inflammatory stimuli trigger IκB phosphorylation and degradation, releasing NF-kβ. The free NF-kβ translocates to the nucleus and promotes the transcription of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), chemokines (IL-8), and enzymes (COX-2, iNOS) [16] [17]. Bioactive compounds from grape leaves, spices, and herbs can block IκB degradation or NF-kβ nuclear translocation, thereby suppressing this inflammatory cascade [16] [18] [17].

Inflammasome and Pro-inflammatory Enzyme Inhibition: Compounds such as resveratrol and curcumin can inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome and enzymes like cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), reducing the production of IL-1β, prostaglandins, and nitric oxide [17] [20].

The diagram below illustrates the NF-kβ inflammatory pathway and its inhibition by bioactive compounds:

Table 2: Anti-inflammatory Effects of Bioactive Compounds on Key Mediators

| Inflammatory Mediator | Function | Effect of Bioactive Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | A potent pro-inflammatory cytokine; regulates immune cells, can induce fever and apoptosis [16] | Grape leaf extract reduced levels; anthocyanins downregulate expression [16] [20] |

| IL-6 | Multifunctional cytokine involved in acute phase response and chronic inflammation [16] [21] | Grape pomace and Mediterranean diet significantly reduce IL-6 levels [16] [21] |

| IL-1β | Key pyrogen; central mediator of fever and chronic inflammatory diseases [16] | Grape pomace reduces IL-1β in colitis models [16] |

| COX-2 | Inducible enzyme synthesizing prostaglandins in inflammation and pain [17] | Resveratrol and flavonoids inhibit COX-2 expression and activity [17] |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | Acute-phase protein; systemic marker of inflammation [21] | Mediterranean diet shows prominent reduction in CRP levels [21] |

Gut Microbiota Modulation

The gut microbiota serves as a key metabolic organ that interacts extensively with dietary bioactive compounds. This interaction is bidirectional: the microbiota transforms these compounds into bioactive metabolites, and the compounds, in turn, modulate the microbial ecosystem.

Microbial Metabolism of Bioactives: Many polyphenols and dietary fibers are not fully absorbed in the small intestine and reach the colon, where gut bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus) metabolize them. This process releases absorbable metabolites (e.g., simple phenolics) and generates short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate from fermented fibers [16] [22] [23].

Microbiota-Mediated Health Effects: SCFAs are not merely waste products; they exert profound health benefits. Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, enhances gut barrier integrity, and possesses anti-inflammatory properties, partly by inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) [22] [20]. Furthermore, a balanced microbiota prevents the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, reduces endotoxemia (e.g., by decreasing LPS), and supports immune function [16] [22].

The following diagram summarizes the interaction between bioactive compounds and the gut microbiota:

Table 3: Impact of Bioactive Compounds on Gut Microbiota Composition and Activity

| Bioactive Compound/Food | Microbiota Modulation | Resulting Metabolic Output/Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Grape Pomace (Polyphenols & Fiber) | Increases Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella; Reduces Escherichia coli and Actinobacteria [16] | Increased SCFA production; Expansion of beneficial bacteria; Reduction in pathogen biofilms [16] |

| Wholemeal Rye Bread (Fiber) | Enriches Lactobacillus (up to 99%) and Bifidobacterium (up to 31%) [23] | Significant increase in SCFAs; Decrease in proteolytic activity (ammonium ions) [23] |

| Anthocyanins | Modulated by microbiota; metabolism enhances bioactivity [20] | Microbial metabolites of anthocyanins contribute to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [20] |

| Plant Sterols (PS-WRB) | Prebiotic effect from fiber; specific metabolism of β-sitosterol to sitostenone [23] | Combines hypocholesterolemic effect of PS with prebiotic benefits of fiber [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assessment of Pro- and Antioxidant Capacity in Food Digesta

This protocol, adapted from [19], evaluates both the antioxidant and pro-oxidant potential of food components and matrices after simulated gastrointestinal digestion, providing a physiologically relevant assessment.

1. Principle: Food items undergo simulated gastrointestinal digestion using the INFOGEST model. The resulting digesta is analyzed using a combination of assays to measure antioxidant capacity (via electron and hydrogen atom transfer mechanisms) and pro-oxidant potential (via lipid oxidation products) [19].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Food Items/Matrices: Test compounds (e.g., vitamins, polyphenols) and complex foods (e.g., sausage, white chocolate, fruit juices) [19].

- Digestive Enzymes: Pepsin, pancreatin, porcine bile extract [19].

- Antioxidant Assay Reagents: FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power), DPPH (1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl), ABTS (2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) reagents [19] [20].

- Pro-oxidant Assay Reagents: Reagents for measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and peroxides (e.g., thiobarbituric acid for MDA) [19].

- Equipment: Water bath or incubator (37°C), centrifuge, spectrophotometer or plate reader.

3. Procedure: A. Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion (INFOGEST model): i. Oral Phase: Mix the food sample with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) and incubate for 2 minutes. ii. Gastric Phase: Adjust the pH to 3.0, add simulated gastric fluid (SGF) containing pepsin, and incubate for 2 hours at 37°C with constant agitation. iii. Intestinal Phase: Adjust the pH to 7.0, add simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) containing pancreatin and bile salts, and incubate for a further 2 hours at 37°C with agitation. iv. Termination & Collection: Stop the reaction (e.g., by cooling on ice). Centrifuge the digesta (e.g., 10,000 × g, 10 minutes) and collect the supernatant for analysis [19].

B. Antioxidant Capacity Measurements: i. FRAP Assay: Mix the digested supernatant with the FRAP reagent (acetate buffer, TPTZ, FeCl₃) and incubate. Measure the absorbance at 593 nm. Results are expressed as mg/L Vitamin C equivalents [19] [20]. ii. DPPH/ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay: Mix the supernatant with the DPPH or ABTS radical solution. After incubation, measure the decrease in absorbance at 517 nm (DPPH) or 734 nm (ABTS). Calculate the percentage of radical scavenging activity [19] [20].

C. Pro-oxidant Potential Measurements: i. Malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay: React the digested supernatant with thiobarbituric acid (TBA). Heat the mixture and measure the pink chromogen formed at 532-535 nm. Calculate the MDA concentration using a standard curve [19]. ii. Peroxide Value: Determine the peroxide content, often via iodometric titration or other colorimetric methods, to assess primary lipid oxidation products [19].

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean and standard deviation for all measurements.

- Develop an anti-pro-oxidant score by combining the results from all five assays (FRAP, DPPH, ABTS, MDA, Peroxide) to provide a holistic view of the oxidative properties of the food digesta [19].

- Correlate the results from different assays; antioxidant assays often correlate well with each other [19].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Evaluation of Anti-inflammatory and Gut Microbiota Modulating Effects in Rodent Models

This protocol describes a method to investigate the systemic effects of bioactive compounds or enriched food matrices in a live animal model, focusing on inflammation and gut microbiota changes.

1. Principle: Rodents (e.g., mice) are fed a specific diet supplemented with the test bioactive compound or extract. Inflammatory status is assessed through tissue analysis and biomarker measurement, while gut microbiota composition is analyzed from fecal samples via 16S rRNA sequencing [16] [20].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Animals: Specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice/rats (e.g., C57BL/6 mice).

- Diets: Control diet and experimental diet supplemented with the test compound (e.g., grape pomace, anthocyanin extract).

- Inducing Agent (if modeling disease): Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for sepsis, dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) for colitis [16] [18].

- ELISA Kits: For cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10).

- RNA Extraction & qPCR Kits: For gene expression analysis of Nrf2, NF-kβ target genes, etc.

- Equipment for Fecal Collection: Sterile tubes.

- 16S rRNA Sequencing Service/Platform.

3. Procedure: A. Animal Grouping and Dosing: i. Acclimate animals for 1 week. ii. Randomly assign them to groups (e.g., Control, Model/Disease, Treatment). iii. Administer the test compound via oral gavage or mixed into the diet for a predetermined period (e.g., 3-8 weeks). The dose should be physiologically relevant [16] [18].

B. Sample Collection: i. Fecal Samples: Collect fresh fecal pellets at baseline and at the end of the intervention. Immediately freeze in sterile tubes at -80°C for microbiota analysis. ii. Blood Serum/Plasma: At sacrifice, collect blood via cardiac puncture. Separate serum/plasma by centrifugation and store at -80°C for ELISA. iii. Tissue Samples: Collect target tissues (e.g., colon, liver, adipose). Snap-freeze a portion in liquid N₂ for molecular analysis and preserve another portion in formalin for histology.

C. Analysis of Inflammatory Markers: i. Cytokine Measurement: Use commercial ELISA kits to quantify pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines in serum or tissue homogenates according to the manufacturer's instructions [16] [21]. ii. Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR): Extract RNA from tissues, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR for genes of interest (e.g., iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-6, Nrf2, HO-1) [16] [20].

D. Analysis of Gut Microbiota: i. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Sequencing: Extract microbial DNA from fecal samples. Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene and perform sequencing on an Illumina platform [16] [23]. ii. Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequences to identify Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and perform statistical analyses (alpha-diversity, beta-diversity) to determine differences in microbial community structure between groups [23]. iii. SCFA Measurement (Optional): Analyze SCFA content (acetate, propionate, butyrate) in fecal or cecal content using gas chromatography (GC) [23].

4. Data Analysis:

- Compare cytokine levels and gene expression between groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA).

- For microbiota data, use PERMANOVA to test for significant differences in community composition and LEfSe to identify specific taxa that are enriched in different groups [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Investigating Bioactive Compound Pathways

| Reagent/Kits | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| INFOGEST Digestion Model Components (Pepsin, Pancreatin, Bile Salts) | Standardized simulated gastrointestinal digestion for food matrices [19] | Protocol 1: In vitro digestion of food items to study bioaccessibility and digesta reactivity [19] |

| Antioxidant Capacity Assay Kits (FRAP, DPPH, ABTS) | Quantify the electron-donating and radical-scavenging capacity of food digesta or extracts [19] [20] | Protocol 1: Measure the antioxidant potential remaining after digestion [19] |

| Lipid Oxidation Assay Kits (Malondialdehyde/MDA Assay) | Measure the end-products of lipid peroxidation as a marker of pro-oxidant activity [19] | Protocol 1: Assess the potential of food digesta to induce oxidative damage [19] |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits for Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10) | Precisely quantify protein levels of key inflammatory cytokines in serum, plasma, or tissue culture supernatants [16] [21] | Protocol 2: Evaluate the systemic anti-inflammatory effect of a treatment in vivo [16] |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Kits & Services | Profile the composition and relative abundance of bacterial taxa in complex communities (e.g., gut microbiota) [16] [23] | Protocol 2: Analyze the impact of a bioactive compound on the gut microbiota structure [23] |

| qPCR Reagents & Primers (for Nrf2, NF-kβ target genes, inflammatory markers) | Quantify the expression levels of genes involved in antioxidant and inflammatory pathways [16] [20] | Protocol 2: Investigate the molecular mechanisms of action in tissue samples [16] |

Application Notes

This document provides a structured overview of bioactive compounds, detailing their health benefits across key disease areas, their mechanisms of action, and standardized experimental protocols for research. This information is intended to guide scientists in the incorporation and evaluation of bioactives within functional food matrices.

Bioactive compounds, including polyphenols, alkaloids, and carotenoids, offer a multi-targeted approach to preventing and managing chronic diseases. Their mechanisms often involve modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and key cellular signaling pathways. The following tables summarize the quantitative evidence and primary mechanisms for cardiovascular, metabolic, and neuroprotective applications.

Table 1: Bioactive Compounds in Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Prevention

| Bioactive Compound | Primary Sources | Key Effects & Mechanisms | Quantitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Peptides | Legumes (e.g., beans, lentils) | Antihypertensive (ACE inhibition), anticoagulant, lipid-lowering [24] | Significant reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in clinical trials [24] |

| Flavonoids | Fruits, vegetables, tea, cocoa | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, improves endothelial function, modulates LDL oxidation [25] | Epidemiological studies link high intake to a reduced risk of CVD mortality [25] |

| Saponins & Isoflavones | Legumes (e.g., soy) | Lipid regulation, enhances endothelial function, modulates TLR4/NF-κB signaling [24] | Clinical studies show reductions in total and LDL cholesterol [24] |

| GABA & Monacolin K | Fermented foods (e.g., red yeast rice) | Antihypertensive, lipid-lowering (statin-like effect) [26] | Fermentation can enhance the yield of these cardioprotective metabolites [26] |

Table 2: Bioactive Compounds in Metabolic Disease Management

| Bioactive Compound | Primary Sources | Key Effects & Mechanisms | Quantitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berberine | Various plants (e.g., goldenseal) | AMPK activation; inhibits adipogenesis (PPARγ, C/EBPα); improves insulin sensitivity [27] | Meta-analysis: Significantly lowers triglycerides, fasting glucose, waist circumference [28] |

| EGCG (Epigallocatechin-3-gallate) | Green tea | Suppresses adipogenesis; stimulates thermogenesis (UCP1 upregulation); inhibits lipogenic enzymes [27] | Clinical data: 4-5% reduction in body fat [27] |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, berries | Activates SIRT1; inhibits PPARγ; enhances insulin sensitivity [27] | Shows promise in managing diabetes and metabolic syndrome [29] |

| Fucoxanthin | Brown seaweed | Stimulates thermogenesis (UCP1); promotes fatty acid oxidation [27] | Preclinical studies show significant reduction in adipose tissue weight [27] |

Table 3: Bioactive Compounds in Neuroprotection

| Bioactive Compound | Primary Sources | Key Effects & Mechanisms | Quantitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Turmeric | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory; anti-amyloidogenic; modulates PI3K/Akt and Nrf2 pathways [30] | Preclinical models show mitigation of neuronal damage and improved cognitive function [30] |

| Flavonoids | Fruits, vegetables, medicinal plants | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition; antioxidant; modulates MAPK and NF-κB pathways [31] | In vitro and in silico studies confirm AChE inhibition, relevant for Alzheimer's disease [31] |

| Urolithin A | Gut metabolite of ellagitannins | Activates AMPK/CREB/BDNF pathway; neurotrophic and antidepressant-like effects [31] | In vivo studies show mitigation of stress-induced neuronal damage and neuroinflammation [31] |

| Ginsenosides | Ginseng | Mitochondrial protection; anti-apoptotic; modulates NF-κB and Nrf2/ARE pathways [30] | Preclinical evidence demonstrates broad-spectrum neuroprotective properties [30] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assessment of Anti-Adipogenic Activity

This protocol is used to evaluate the potential of bioactive compounds to inhibit the formation of new fat cells, a key mechanism in managing obesity [27].

Materials:

- 3T3-L1 mouse preadipocyte cell line

- Standard adipogenic differentiation cocktail: Insulin, dexamethasone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX)

- Test compound (e.g., purified bioactive or food extract)

- Oil Red O stain for lipid droplet visualization

- Lysis buffer (e.g., isopropanol) for dye extraction

- MTT reagent for cytotoxicity assessment

Procedure:

- Cell Culture & Differentiation: Maintain 3T3-L1 preadipocytes in growth media until confluent. Induce differentiation (Day 0) by replacing media with differentiation cocktail. After 48-72 hours, replace with media containing only insulin for the remainder of the experiment [29].

- Compound Treatment: Add the test compound at various non-cytotoxic concentrations (determined by MTT assay) at the onset of differentiation (Day 0).

- Staining & Quantification: On Day 7-10 post-differentiation, wash cells and fix with formalin. Stain intracellular lipid droplets with Oil Red O solution. Extract the stain with isopropanol and measure absorbance at 510-520 nm to quantify lipid accumulation relative to untreated differentiated controls.

- Western Blot Analysis: Harvest cells and analyze lysates via Western blot for key adipogenic markers (e.g., PPARγ, C/EBPα, FABP4) to confirm mechanistic action [29].

Protocol 2: Clinical Assessment of Muscle Damage and Inflammation Recovery

This protocol outlines a method for evaluating the efficacy of bioactive compounds in reducing exercise-induced skeletal muscle damage and inflammation in human subjects [32].

Materials:

- Standardized supplement: e.g., oat avenanthramides (AVA) or extra virgin olive oil oleocanthal (OCT).

- Venous blood collection kits

- ELISA kits for biomarkers: Creatine Kinase (CK), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF)

- Flow cytometer for Neutrophil Respiratory Burst (NRB) analysis

- Pain rating scale (e.g., Visual Analogue Scale)

Procedure:

- Study Design: Employ a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Include a washout period between trial arms.

- Supplementation & Exercise: Administer the bioactive supplement or placebo daily for a set period (e.g., 1-2 weeks) prior to a standardized eccentric exercise bout (e.g., downhill running).

- Biomarker Sampling: Collect blood samples at baseline (pre-exercise) and at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-exercise.

- Analysis:

- Quantify plasma CK levels as a marker of muscle damage.

- Assess inflammatory markers (IL-6, G-CSF) and anti-inflammatory markers (e.g., IL-1Ra) via ELISA.

- Analyze NRB using flow cytometry as a measure of oxidative stress.

- Record muscle soreness using a pain rating scale at each time point [32].

- Data Interpretation: Compare the time-course and peak levels of all biomarkers and soreness ratings between the bioactive and placebo groups.

Protocol 3: In Vitro Assessment of Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibition

This protocol is used to screen bioactive compounds, particularly flavonoids, for their potential to improve cholinergic function, which is critical in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's [31].

Materials:

- Purified Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme

- Test compound (e.g., flavonoid extract or pure compound)

- Substrate: Acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI)

- Colorimetric reagent: 5,5'-Dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB)

- Positive control: e.g., Galantamine

- Microplate reader

Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture: In a microplate well, combine the test compound at various concentrations with AChE enzyme in a suitable buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 8.0).

- Incubation: Pre-incubate the mixture for 15 minutes at 37°C.

- Reaction Initiation: Add the substrate (ATCI) and the chromogenic agent (DTNB) to start the reaction.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately monitor the formation of the yellow 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate anion at 412 nm for 10-15 minutes.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage of enzyme inhibition using the reaction rates. Determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values by analyzing a range of compound concentrations.

Pathway and Mechanism Visualizations

Bioactive Compound Neuroprotective Pathways

Anti-Obesity Mechanism of Action

Experimental Workflow for Bioactivity Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Bioactive Compound Research

| Research Tool | Function & Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| 3T3-L1 Pre-adipocyte Cell Line | In vitro model for studying adipocyte differentiation and screening compounds for anti-obesity potential [27] [29]. | Protocol 1: Assessing inhibition of lipid accumulation by berberine or EGCG. |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Enzyme Kit | Colorimetric assay to measure AChE inhibition, a key target for Alzheimer's disease therapeutics [31]. | Protocol 3: Screening flavonoid-rich extracts for neuroprotective potential. |

| ELISA Kits for Cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-1Ra) | Quantify specific protein biomarkers of inflammation in cell culture supernatants or biological fluids [32]. | Protocol 2: Measuring anti-inflammatory effects of avenanthramides post-exercise. |

| Oil Red O Stain | Stains neutral lipids and triglycerides; used to visualize and quantify lipid droplet content in adipocytes [29]. | Protocol 1: Quantifying the extent of anti-adipogenic activity in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. |

| Creatine Kinase (CK) Assay Kit | Enzymatic assay to measure CK activity in plasma/serum as a reliable marker of muscle damage [32]. | Protocol 2: Evaluating the protective effect of oleocanthal on skeletal muscle integrity. |

The Functional Food Matrix (FM) is defined as the intricate relationship between the nutrient and non-nutrient components in food, including their molecular relationships and structural organization [33]. Moving beyond a simple nutrient-based perspective, the FM concept recognizes that a food's health potential is defined by both its structural complexity and its nutritional composition [34]. This holistic view acknowledges that the physiological effects of a food cannot be predicted solely by analyzing its individual components, as the interactions between these components within the matrix significantly influence nutrient bioavailability, metabolic responses, and ultimately, human health [33] [34].

Contemporary food science has shifted from reductionist approaches toward this integrated FM concept, driven by evidence that identical nutrient compositions embedded in different matrices exert different health effects [34]. For instance, the degree of food processing dramatically alters matrix structure, with studies demonstrating that ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are consistently less satiating and more hyperglycemic than their minimally-processed counterparts, even when nutritional profiles appear similar [34]. Understanding and manipulating the FM therefore presents unprecedented opportunities for designing specialized foods for specific populations and health outcomes [35].

Key Interactions Within the Food Matrix

Food matrices comprise dynamic systems where components interact through various mechanisms. These interactions, which occur at molecular, physical, and structural levels, ultimately govern the functional properties and health impacts of foods [33].

Table 1: Classification and Impact of Major Food Matrix Interactions

| Interaction Type | Components Involved | Technological & Health Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Interactions | Starch-lipids, proteins-phenols [33] | Reduced starch digestibility; altered protein functionality; modified bioavailability [36] [33] |

| Ternary Interactions | Starch-lipid-protein, fiber-mineral-phytate [33] | Further modulation of starch bioavailability; mineral absorption; controlled release during digestion [33] |

| Quaternary Interactions | Multiple macrocomponents with minor elements [33] | Determines overall glycemic response; sensory properties; shelf stability [33] [34] |

| Matrix-Encapsulant | Wall materials-bioactives-food components [35] [37] | Protection of sensitive compounds; controlled release in gut; masked undesirable flavors [35] [37] |

These interactions explain why the same bioactive compound can yield different health outcomes when delivered in different food systems. For example, polyphenols from fruit incorporated into yogurt may interact with dairy proteins and fats, which can affect both the physicochemical properties of the yogurt and the bioavailability of the polyphenols [36]. Similarly, the formation of complexes between starch and lipids during processing can create resistant starch, reducing the Inherent Glycemic Potential (IGP) [33].

Quantitative Assessment of Matrix Effects

Measuring the Glycemic Impact

The Inherent Glycemic Potential (IGP) is a crucial parameter for assessing how a food matrix intrinsically influences glucose release [33]. Unlike traditional glycemic indices, IGP aims to capture the combined effect of a food's composition, structure, and the interactions between its components.

Table 2: In-Vitro Methods for Assessing Starch Digestibility and Glycemic Potential

| Method | Key Equation | Procedure Overview | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Englyst Method [33] | RDS = (G20 - FG) * 0.9SDS = (G120 - G20) * 0.9RS = TS - RDS - SDS |

- Oral: Simulated with mincers.- Gastric: No pepsin.- Intestinal: Pancreatin/AMG at pH 5.2; measures glucose at 20 & 120 min. | Quantifies RDS, SDS, RS types (RS1, RS2, RS3) [33] | No gastric proteolysis; complex procedure [33] |

| Goñi's Method [33] | C = C∞ (1 - e^(-kt))(First-order kinetics model) |

- Oral: Homogenization.- Gastric: Pepsin at pH 1.5.- Intestinal: α-amylase at pH 6.9; aliquots taken every 30 min for 3h. | Simpler than Englyst; provides hydrolysis kinetics [33] | Less differentiation of RS types [33] |

Abbreviations: RDS: Rapidly Digestible Starch; SDS: Slowly Digestible Starch; RS: Resistant Starch; FG: Free Glucose; TS: Total Starch; G20/G120: Glucose at 20/120 minutes; C: Hydrolyzed starch concentration; C∞: Equilibrium concentration; k: Kinetic constant.

Linking Processing Degree to Food Properties

Quantitative studies have established clear relationships between the degree of food processing, matrix structure, and health potential. Analysis of 139 solid foods revealed that, compared to ultra-processed foods (UPFs), minimally-processed foods are significantly less hyperglycemic, more satiating, have higher water activity, shorter shelf life, and require higher energy to break down, indicating a more robust structure [34]. Data mining suggests that a LIM score ≥ 8 per 100 kcal and number of ingredients/additives > 4 are relevant, though not sufficient, quantitative rules for classifying a food as ultra-processed [34].

Experimental Protocols for Food Matrix Research

Objective: To determine the kinetic parameters of starch hydrolysis and classify starch fractions in a food matrix.

Reagents & Equipment:

- Phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.9)

- Pancreatic α-amylase solution

- Amyloglucosidase (AMG)

- Pepsin solution in HCl-KCl buffer (pH 1.5)

- Tris-Maleate buffer (pH 6.9)

- Water bath with shaking capability

- Centrifuge

- Glucose assay kit (e.g., GOPOD)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the food sample to a consistent particle size. Record the initial moisture and total starch content.

- Oral Phase Simulation (Optional): Further homogenize the sample to simulate mastication.

- Gastric Phase: Suspend the sample in the pepsin-HCl solution. Incubate at 40°C for 60 minutes in a shaking water bath to simulate proteolysis.

- Intestinal Phase:

- Neutralize the gastric digest and adjust to pH 6.9 using Tris-Maleate buffer.

- Add a defined concentration of pancreatic α-amylase to initiate hydrolysis.

- Incubate at 37°C with constant shaking.

- Withdraw 1 mL aliquots at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes.

- Glucose Measurement:

- Immediately transfer each aliquot to a tube and immerse in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes to inactivate enzymes.

- Centrifuge to obtain a clear supernatant.

- Digest the supernatant with AMG at 60°C to convert hydrolyzed starch to glucose.

- Quantify the glucose content using a standard assay (e.g., GOPOD).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of starch hydrolyzed at each time point.

- Plot hydrolysis percentage (C) versus time (t).

- Fit the data to a first-order kinetic model:

C = C∞ (1 - e^(-kt)), whereC∞is the equilibrium concentration andkis the kinetic constant. - Calculate Rapidly Digestible Starch (RDS), Slowly Digestible Starch (SDS), and Resistant Starch (RS) based on the hydrolysis curves.

Objective: To quantify the mechanical and structural properties of solid foods, which are linked to satiety and digestion kinetics.

Reagents & Equipment:

- Universal Testing Machine (e.g., Instron)

- Compression cell and shear blade

- Software for data acquisition (e.g., Bluehill)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut the ready-to-eat food into standardized parallelepipeds (e.g., 1.0 cm width, 2.0 cm thickness). For heterogeneous foods, increase the number of replicates (n=15-20).

- Compression Test (Simulates Molar Action):

- Place the sample on the fixed lower part of the compression cell.

- Set the movable upper part to descend at a constant rate (e.g., 50 mm/min).

- Record the force required to compress the sample until fracture or a defined deformation (e.g., 80%).

- From the force-deformation curve, extract parameters: Maximum Force (F_max), Stress at 20% and 80% compression, and Energy at Break (area under the curve).

- Shear Test (Simulates Incisor Action):

- Use a shear blade attached to the testing machine.

- Apply a shearing force to the sample at a constant speed.

- Record the Maximum Shear Force required to cut through the material.

- Data Interpretation:

- Correlate textural parameters with the degree of processing and sensory data. Minimally-processed foods typically exhibit higher energy at break and complex fracture patterns, while UPFs often have lower maximum stress and a more homogeneous texture [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Food Matrix Research

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic α-Amylase | Simulates carbohydrate digestion in the small intestine; used in in-vitro digestibility models. | Key enzyme for assessing starch hydrolysis kinetics and calculating IGP [33]. |

| Amyloglucosidase (AMG) | Converts hydrolyzed starch fragments (maltose, dextrins) to glucose for quantification. | Essential for accurate measurement of glucose release in Englyst and Goñi methods [33]. |

| Encapsulation Wall Materials (e.g., Sodium Alginate, Gum Arabic, Chitosan) | Form protective matrices around bioactive compounds to enhance stability and control release. | Used to study and improve the stability of bioactives like polyphenols in fortified foods [8] [37]. |

| Pepsin | Simulates proteolytic digestion in the gastric phase; breaks down food structures and protein-based microcapsules. | Critical for a physiologically relevant in-vitro gastrointestinal model [33]. |

| Specific Probiotic Strains (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) | Live microorganisms conferring health benefits; used to develop probiotic-fermented foods. | Studied for producing bioactive peptides in dairy matrices and for their viability in fruit-enriched yogurts [36]. |

| Biopolymer Gels (e.g., Whey Protein Isolates, Pectin) | Used as model food matrices or encapsulation materials to study controlled release mechanisms. | Enable research on how matrix properties affect the stability and bioavailability of encapsulated compounds [36] [35]. |

Advanced Applications: Encapsulation and Targeted Delivery

Encapsulation technologies are powerful tools for engineering functional food matrices. They protect sensitive bioactive compounds (e.g., polyphenols, omega-3s, probiotics) from degradation during processing and storage, and can control their release in the gastrointestinal tract [35] [37]. The choice of encapsulation method and wall material is critical and depends on the desired functionality within the final food matrix.

The success of encapsulation is not solely dependent on protecting the bioactive during storage. Once incorporated into a food, the entire product undergoes structural reorganization during digestion, which impacts the release profile and bioavailability of the fortified compound [35]. This highlights the necessity of studying the encapsulated bioactive not in isolation, but within the context of the complete, dynamic food matrix.

From Extraction to Integration: Advanced Techniques for Incorporating Bioactives into Food

The incorporation of bioactive compounds into food matrices represents a frontier in functional food development, with profound implications for human health. The efficacy of such fortification is fundamentally dependent on the initial extraction process, which determines the yield, stability, and bioactivity of the target phytochemicals. Conventional extraction methods often involve high temperatures, prolonged extraction times, and large volumes of organic solvents, which can degrade thermolabile compounds and introduce undesirable residues. In response, modern green extraction technologies—including ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE)—have emerged as efficient, sustainable alternatives. These methods, especially when coupled with green solvents, enhance extraction efficiency while aligning with the principles of green chemistry and circular bioeconomy. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for these techniques, contextualized within a research framework aimed at enriching food matrices with bioactive compounds for enhanced nutritional and therapeutic outcomes [38] [39] [40].

Comparative Performance of Modern Extraction Techniques

The selection of an appropriate extraction method is critical for optimizing the recovery of bioactive compounds from plant materials. The following table summarizes the key operational parameters, advantages, and ideal applications for the three primary modern extraction techniques, based on current research findings.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of modern extraction techniques for bioactive compounds.

| Extraction Technique | Key Operational Parameters | Representative Bioactive Yield (vs. Conventional) | Primary Advantages | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Frequency: 20–100 kHz; Temperature: 20–60°C; Time: 5–30 min [41] [42] | Total Phenols: 243.94 mg GAE/g (vs. 80.43 mg GAE/g in Tamus communis) [41] | Rapid extraction; enhanced yield of phenolics; low thermal degradation [41] [42] | Extracting thermolabile flavonoids and phenolic acids for antioxidant-rich ingredients. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Power: 300–600 W; Time: 10–20 min; Solvent: Water, Ethanol, NADES [43] [44] | Polyphenols: 21.76 mg GAE/g from mandarin peel; high tangeretin & nobiletin yield [44] | Reduced extraction time & solvent use; high selectivity [43] [44] | Efficient recovery of polyphenols and carotenoids from fruit peels and agricultural by-products. |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Pressure: 100–400 bar; Temperature: 40–70°C; Co-solvent: Ethanol (1–10%) [45] | Selective isolation of essential oils, antioxidants, and non-polar compounds [45] | Solvent-free (CO₂); high purity extracts; preserves heat-sensitive compounds [45] | Production of high-value, solvent-free extracts for pharmaceuticals and functional foods. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Phenolics fromTamus communisFruits

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating superior recovery of phenolic compounds using UAE, resulting in enhanced anti-tyrosinase and anti-inflammatory activities compared to conventional methods [41].

- Objective: To efficiently extract phenolic compounds, particularly flavonoids and phenolic acids, from Tamus communis fruits using ultrasound.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Plant Material: Dried and powdered Tamus communis fruits.

- Extraction Solvent: Aqueous ethanol (e.g., 50–80% ethanol in water).

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator (frequency range 20–40 kHz), centrifuge, rotary evaporator.

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Weigh 5 g of dried plant powder into an extraction vessel.

- Solvent Addition: Add 100 mL of aqueous ethanol solvent (sample-to-solvent ratio of 1:20).

- Sonication: Subject the mixture to ultrasound irradiation for 15–30 minutes at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C). For a probe system, set the amplitude appropriately.

- Separation: Centrifuge the sonicated mixture at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the solid residue.

- Concentration: Collect the supernatant and concentrate under reduced pressure at ≤40°C using a rotary evaporator.

- Analysis: Reconstitute the dried extract for analysis of total phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity (e.g., DPPH, ABTS assays).

- Notes: The significant increase in tyrosinase inhibition (65.61% for UAE vs. 21.78% for conventional) highlights the technique's ability to preserve bioactivity [41].

Protocol 2: Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) of Polyphenols and Carotenoids from Mandarin Peel

This protocol utilizes a closed-vessel MAE system for the efficient and simultaneous recovery of polyphenols and carotenoids, representing a scalable biorefinery approach [44].

- Objective: To extract polyphenols and carotenoids from mandarin peel using optimized MAE conditions with green solvents.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Plant Material: Dried, powdered mandarin peel (Citrus unshiu Marc.).

- Extraction Solvent: Ethanol-water mixture (e.g., 70–80% ethanol).

- Equipment: Closed-vessel microwave extraction system, centrifuge, rotary evaporator.

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Weigh 1 g of mandarin peel powder into the microwave vessel.

- Solvent Addition: Add solvent at a ratio of 1:10 to 1:15 (w/v).

- Microwave Irradiation: Set the microwave power to 300–500 W and irradiate for 10–15 minutes.

- Cooling and Separation: Allow the vessel to cool, then centrifuge the mixture to separate the extract.

- Concentration: Concentrate the supernatant under vacuum.

- Analysis: Analyze for total polyphenols, specific flavonoids (nobiletin, tangeretin), carotenoid content (β-carotene), and antioxidant capacity (DPPH, ABTS) [44].

- Notes: MAE significantly reduces extraction time and energy consumption compared to conventional solvent extraction while achieving high yields of bioactive compounds like nobiletin and β-carotene [44].

Protocol 3: Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) with CO₂ and Co-solvents

This protocol outlines the use of supercritical CO₂ for the solvent-free extraction of non-polar bioactive compounds, with the option to enhance polarity range using ethanol as a co-solvent [45].

- Objective: To extract lipophilic bioactive compounds from plant matrices using supercritical CO₂.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Plant Material: Dried, coarsely ground plant matter (e.g., herbs, seeds).

- Solvent: Food-grade carbon dioxide (CO₂).

- Co-solvent: Anhydrous ethanol (typically 1–10% of total solvent volume).

- Equipment: SFE system comprising CO₂ pump, co-solvent pump, extraction vessel, pressure and temperature controllers, and separator.

- Procedure:

- Loading: Pack the extraction vessel tightly with the plant material.

- Pressurization and Heating: Pressurize the system to the desired pressure (e.g., 250–350 bar) and heat to the target temperature (e.g., 40–60°C) to achieve supercritical conditions for CO₂.

- Dynamic Extraction: Pass the supercritical CO₂ through the plant material at a constant flow rate. If using a co-solvent, pump ethanol into the CO₂ stream at the predetermined ratio.

- Collection: The extract-laden solvent passes into a separator where pressure is reduced, causing CO₂ to gasify and leaving the bioactive extract in the collection vessel.

- Analysis: The residue-free extract can be analyzed by GC-MS or HPLC for target compounds.

- Notes: The selectivity of the extraction can be fine-tuned by adjusting pressure and temperature. The addition of a co-solvent like ethanol is crucial for improving the yield of more polar compounds, such as certain polyphenols [45].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Decision Pathway for Extraction Method Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate modern extraction method based on the physicochemical properties of the target bioactive compound and the research objectives.

Integrated Biorefinery Workflow for Agri-Food Waste Valorization

This diagram illustrates a sequential, multi-step biorefinery approach for the comprehensive valorization of agri-food waste, such as citrus peel, using a combination of modern extraction techniques to recover different classes of bioactives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of modern extraction protocols requires specific reagents and equipment. The following table lists key solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for modern extraction techniques.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Green solvents for MAE and UAE, composed of natural primary metabolites (e.g., Choline Chloride:Lactic Acid) [43] [38]. | Offer low toxicity and high biodegradability; can be tailored for selective extraction of specific bioactive classes. |

| Food-Grade Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | The primary solvent for Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [45]. | Non-toxic, non-flammable, and easily removed from the final extract, yielding a solvent-free product. |

| Ethanol-Water Mixtures | Versatile, green solvents for UAE and MAE, effective for extracting a wide range of polyphenols and carotenoids [41] [44]. | Concentration is critical; 70-80% ethanol is often optimal for phenolic compounds. |

| Closed-Vessel Microwave System | Equipment for MAE enabling controlled temperature and pressure, preventing solvent loss [44]. | Superior to household microwaves for reproducibility, safety, and efficiency, facilitating method scale-up. |

| Ultrasonic Probe System | Equipment for UAE that delivers high-intensity ultrasound directly into the sample mixture [41] [42]. | Generally more efficient for disrupting tough plant cell walls compared to ultrasonic baths. |

| High-Pressure Pumps & Vessels | Core components of an SFE system designed to contain and handle supercritical CO₂ [45]. | Require specialized design to withstand operational pressures (e.g., 100-400 bar). |

The integration of bioactive compounds into food matrices represents a frontier in the development of functional foods, which provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition [4]. These bioactive compounds—including polyphenols, carotenoids, and alkaloids—exhibit diverse therapeutic effects such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gut-modulating activities [4]. However, their precise incorporation and efficacy depend on rigorous analytical characterization to ensure stability, bioavailability, and functionality within complex food systems [46]. Hyphenated techniques, which combine separation technologies with spectroscopic detection, have emerged as indispensable tools for this purpose [47] [48]. By exploiting the complementary advantages of chromatography and spectroscopy, these methods provide comprehensive structural information crucial for identifying unknown compounds in complex natural product extracts or fractions [47] [49]. This application note details the operational principles, methodologies, and practical applications of key hyphenated techniques—particularly HPLC-DAD-MS and LC-NMR—within the context of bioactive compound research for functional food development.

Hyphenated Techniques: Principles and Relevance

Core Concepts and Definitions

Hyphenated techniques are developed from the coupling of a separation technique with an online spectroscopic detection technology [47]. The term "hyphenation" was introduced by Hirschfeld to refer to the online combination of a separation technique and one or more spectroscopic detection techniques [47]. This approach synergistically exploits the advantages of both methodologies: chromatography produces pure or nearly pure fractions of chemical components in a mixture, while spectroscopy provides selective information for identification using standards or library spectra [47]. In recent years, hyphenated techniques have received ever-increasing attention as principal means to solve complex analytical problems in natural product research [47].

The power of combining separation technologies with spectroscopic techniques has been demonstrated for both quantitative and qualitative analysis of unknown compounds in complex matrices such as natural product extracts [47]. To obtain structural information leading to the identification of compounds in a crude sample, high-performance separation techniques like liquid chromatography (LC), gas chromatography (GC), or capillary electrophoresis (CE) are linked to spectroscopic detection methods including Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR), photodiode array (PDA) UV-vis absorbance, mass spectrometry (MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [47].

Techniques for Bioactive Compound Analysis

Table 1: Common Hyphenated Techniques in Bioactive Compound Research

| Technique | Separation Method | Detection Method | Key Applications in Food Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-DAD-MS | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography | Diode Array Detection & Mass Spectrometry | Simultaneous quantification and identification of phenolic compounds, methylxanthines in beverages [50] |

| LC-NMR | Liquid Chromatography | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance | Structural elucidation of isomeric compounds; identification of unknown metabolites [49] [51] |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography | Mass Spectrometry | Analysis of volatile compounds, fatty acids, essential oils [47] |

| LC-FTIR | Liquid Chromatography | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | Functional group identification; structural confirmation [47] |

| CE-MS | Capillary Electrophoresis | Mass Spectrometry | Analysis of polar ionic compounds; chiral separations [47] |

The remarkable improvements in hyphenated analytical methods over the last two decades have significantly broadened their applications in analyzing natural products and functional foods [47]. These techniques find particular utility in pre-isolation analyses of crude extracts, isolation and online detection of natural products, chemotaxonomic studies, chemical fingerprinting, quality control of herbal products, dereplication of natural products, and metabolomic studies [47]. For functional food research, this translates to capabilities for verifying bioactive compound integrity after incorporation into food matrices, monitoring stability during storage, and confirming bioavailability in simulated digestion models [4] [46].

HPLC-DAD-MS Analysis: Protocols and Applications

Operational Principles and Instrumentation

HPLC-DAD-MS combines the separation power of high-performance liquid chromatography with the detection capabilities of diode array detection and mass spectrometry [52]. This hyphenated technique provides complementary data: HPLC separates complex mixtures, DAD offers UV-Vis spectra for preliminary compound classification, and MS provides molecular weight and fragmentation information [47] [52]. The physical connection of HPLC and MS has increased the capability of solving structural problems of complex natural products [47].

A typical HPLC-DAD-MS system consists of an autosampler, HPLC pump, chromatographic column, DAD detector, and mass spectrometer with appropriate ionization source [53] [52]. The remarkable aspect of this hyphenation is the ability to obtain multiple dimensions of information from a single analysis—chromatographic retention time, UV-Vis spectrum, and mass spectrum—which collectively enable comprehensive compound characterization [52].

Experimental Protocol: Analysis of Bioactive Compounds in Plant Extracts

Protocol Title: HPLC-DAD-MS Analysis of Polyphenols and Methylxanthines in Green Tea Extract

Objective: To simultaneously separate, quantify, and identify phenolic compounds and methylxanthines in green tea extracts for quality assessment and functional food formulation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% formic acid

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Reference Standards: Gallic acid, catechins (C, EC, EGCG, GCG), methylxanthines (caffeine, theobromine, theophylline)

- Columns: C18 reverse phase column (e.g., Agilent Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18, 4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm)

- Samples: Green tea extracts, functional beverage formulations

Instrumentation Parameters [53] [50]:

- HPLC System: Agilent 6120 series or equivalent

- Injection Volume: 10 μL

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 25°C

- Gradient Program: Linear gradient from 10% to 90% B over 28 minutes

- DAD Detection: 200-400 nm range, specific monitoring at 270-280 nm

- MS Conditions: Positive electrospray ionization; mass range: 100-2000 m/z; fragmentor voltage: optimized for each compound class

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 1.0 g of green tea leaves and extract with 10 mL of 70% methanol using ultrasonic bath for 30 minutes. Filter through 0.45 μm membrane filter before injection.

- System Equilibration: Equilibrate the column with initial mobile phase composition (10% B) for at least 15 minutes until stable baseline is achieved.

- Calibration Standards: Prepare reference standard solutions at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 μg/mL for each analyte.

- Sample Analysis: Inject samples and standards following the established gradient elution program.

- Data Acquisition: Collect simultaneous DAD (200-400 nm) and MS (full scan and targeted MS/MS) data.