Enhancing Dietary Intervention Compliance: Self-Monitoring Techniques, Optimization Strategies, and Clinical Validation

This article synthesizes current evidence on self-monitoring as a cornerstone of behavioral dietary interventions for researchers and drug development professionals.

Enhancing Dietary Intervention Compliance: Self-Monitoring Techniques, Optimization Strategies, and Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current evidence on self-monitoring as a cornerstone of behavioral dietary interventions for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational role of self-monitoring in weight management and health outcomes, examines traditional and emerging digital methodologies, and analyzes key challenges such as adherence decay. The content provides a comparative analysis of optimization frameworks like the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and validation evidence from recent clinical trials, including the role of feedback and cognitive modeling. This review aims to inform the development of more effective, data-driven, and personalized dietary monitoring strategies for clinical and research applications.

The Critical Role of Self-Monitoring in Dietary Interventions and Weight Management

Self-Monitoring as a Cornerstone of Behavioral Weight Loss Programs

Self-monitoring (SM) of dietary behaviors is a foundational component of most behavioral weight loss programs, widely recognized for its effectiveness in promoting healthy behavior changes and improving health outcomes [1] [2]. As overweight and obesity rates continue to escalate globally—with 43% of adults classified as overweight and 16% as obese in 2022—the economic and health burdens necessitate effective intervention strategies [1]. The core premise of dietary self-monitoring operates on principles of self-regulation, enabling individuals to enhance awareness of their eating behaviors in relation to dietary goals in real-time, thereby facilitating behavior change through a phenomenon known as reactivity [3]. Despite its established efficacy, adherence to self-monitoring protocols tends to decline over time due to the labor-intensive nature of traditional methods and the absence of efficient passive recording systems [1] [4]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms, efficacy, and implementation methodologies of dietary self-monitoring within weight loss interventions, with particular emphasis on digital innovations and tailored support systems that enhance long-term adherence.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms of Action

Cognitive Architecture of Self-Monitoring

The Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture provides a robust computational framework for modeling adherence dynamics in dietary self-monitoring. ACT-R integrates physical, neurophysiological, behavioral, and cognitive mechanisms into a unified model consisting of symbolic and subsymbolic systems [1]. The architecture operates through several key mechanisms:

- Activation: Determines the accessibility of knowledge chunks in declarative memory, influenced by base-level activation (frequency of access) and spreading activation (contextual relationships)

- Retrieval: Selects and activates specific knowledge chunks from declarative memory, with probability influenced by activation level

- Learning: Calculates the utility of production rules through repeated execution and reward accumulation

- Selection: Chooses which production rule to execute based on utility values [1]

Within weight management interventions, ACT-R modeling reveals that goal pursuit mechanisms typically remain dominant throughout the intervention period, while the influence of habit formation mechanisms often diminishes during later stages [1] [2]. This cognitive framework enables researchers to simulate and predict adherence patterns under various intervention conditions, providing valuable insights for program optimization.

Metacognitive Foundations

Effective self-monitoring relies heavily on accurate metacognitive monitoring—the ability to evaluate one's own comprehension and performance. Research indicates that monitoring accuracy is essential for appropriate regulatory actions in learning and behavior change [5]. The construction-integration model of text comprehension proposes that learners construct mental representations at multiple levels: surface level (word encoding), text-based level (propositional connections), and situation-model level (deep understanding through integration with prior knowledge) [5]. Interventions that prompt learners to utilize situation-model cues rather than surface-level cues significantly enhance monitoring accuracy, ultimately supporting more effective self-regulation of health behaviors [6] [5].

Efficacy and Adherence Dynamics

Quantitative Adherence Metrics

Recent studies employing computational modeling and trajectory analysis have yielded significant insights into self-monitoring adherence patterns. The ACT-R modeling approach has demonstrated strong predictive capability for dietary self-monitoring behaviors across different intervention frameworks, with root mean square error (RMSE) values indicating high model precision [1] [2].

Table 1: ACT-R Model Performance Across Intervention Groups

| Intervention Group | Sample Size | RMSE Value | Dominant Cognitive Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-management | 49 | 0.099 | Goal pursuit |

| Tailored feedback | 23 | 0.084 | Goal pursuit |

| Intensive support | 25 | 0.091 | Goal pursuit |

Data-driven trajectory modeling using group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) has identified distinct participant subgroups with differing adherence patterns and weight loss outcomes [4]. Studies reveal that a "Higher SM Group" demonstrating consistent self-monitoring behaviors achieves significant weight loss and maintained glycemic control, while a "Lower SM Group" with consistently low adherence shows minimal clinical improvements [4]. Notably, these subgroups exhibit significantly different SM adherence levels as early as the second week of intervention, highlighting the critical importance of early engagement.

Adherence Determinants and Barriers

Table 2: Key Facilitators and Barriers to Self-Monitoring Adherence

| Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|

| Acceptance of SM technologies | Forgetfulness |

| Perceived SM benefits | Burdensome SM process |

| Positive problem-solving skills | Technical inaccuracies |

| Tailored feedback | Discouragement from challenges |

| Social and emotional support | Time-consuming food entry |

Qualitative analyses across multiple studies have consistently identified several thematic categories influencing self-monitoring adherence [4]. Acceptance toward SM technologies emerges as a critical facilitator, particularly when participants perceive tools as accurate and easy to use. The presence of automatic syncing functionality significantly enhances technology acceptance and regular use [4]. Participants across adherence levels recognize SM benefits, describing it as "positive feedback" that aids in diet and physical activity behavior changes [4].

However, significant barriers persist. Both responders and non-responders cite individual challenges (forgetfulness) and technical issues (inaccurate food databases, time-consuming entry processes) as impediments to consistent monitoring [4]. The distinction between adherence groups manifests primarily in their responses when facing SM barriers. Responders demonstrate positive problem-solving approaches to overcome challenges, while non-responders often become discouraged and disengage from monitoring activities [4].

Digital Self-Monitoring Interventions

Technological Modalities and Implementation

Digital technologies have transformed dietary self-monitoring by enhancing accessibility, convenience, and precision. Modern implementations typically utilize:

- Mobile applications providing real-time tracking capabilities

- Mobile-optimized websites ensuring cross-platform compatibility

- Wearable devices enabling passive data collection

- Automated feedback systems delivering personalized guidance [1] [3]

Research indicates that digital self-monitoring adherence significantly surpasses traditional paper-based methods, primarily through reducing participant burden and enabling immediate data recording [1]. A proof-of-concept trial examining digital dietary self-monitoring for children reported participants tracked intake on 23.6 ± 4.6 of 28 days, with 69.3% ± 45.1% of items recorded on the day of intake [3].

Reinforcement Strategies for Enhanced Engagement

Positive reinforcement (PR) techniques have demonstrated significant potential for improving self-monitoring adherence, particularly in pediatric populations. Two primary reinforcement modalities have been investigated:

- Caregiver praise: A social reinforcer providing social acceptance and encouragement

- Gamification: A token reinforcer utilizing points, badges, or "leveling up" that can be exchanged for rewards [3]

Recent research indicates that automated gamification (implemented on 20.8 ± 12.3 of 28 days) was delivered more consistently than caregiver praise (implemented on 12.2 ± 5.8 of 28 days), suggesting that automation provides advantages for immediate, consistent, and convenient reinforcement [3]. This consistent delivery aligns with established principles of effective reinforcement, which emphasize immediacy and reliability [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ACT-R Modeling Protocol for Adherence Prediction

The development of prognostic models for dietary self-monitoring adherence using ACT-R architecture involves a structured methodology:

Participant Recruitment and Group Assignment

Data Collection and Variable Definition

- Collect daily self-monitoring data over 21-day intervention periods

- Define predictor and outcome variables as adjacent elements in self-monitoring sequences

- Record frequency, timing, and completeness of dietary entries [1]

Model Implementation and Validation

Diagram Completion Intervention for Metacognitive Monitoring

Enhancing monitoring accuracy through diagram completion interventions follows an established protocol:

Intervention Design

Implementation Protocol

- Participants study texts followed by delayed diagram completion (minimum 30-minute delay)

- Participants complete diagrams by filling missing causal relationships

- Provide performance standards (correctly completed diagrams) as feedback in experimental conditions [6]

Assessment and Analysis

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Self-Monitoring Intervention Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| ACT-R Cognitive Architecture | Computational modeling of adherence dynamics and cognitive mechanisms | Prognostic model development for dietary self-monitoring adherence [1] [2] |

| Group-Based Trajectory Modeling (GBTM) | Identification of participant subgroups with distinct adherence patterns | Classification of Higher SM and Lower SM groups based on longitudinal adherence [4] |

| Causal Diagram Completion Tasks | Generation of situation-model cues to enhance metacognitive monitoring accuracy | Intervention to improve monitoring accuracy in text comprehension [6] [5] |

| Digital Self-Monitoring Logs | Mobile-optimized platforms for real-time dietary tracking | 4-week monitoring of fruits, vegetables, snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages [3] |

| Positive Reinforcement Systems | Implementation of reward structures to enhance self-monitoring adherence | Automated gamification and caregiver praise delivery protocols [3] |

Self-monitoring remains an indispensable component of effective behavioral weight loss interventions, with digital technologies and computational modeling approaches offering unprecedented opportunities to enhance adherence and outcomes. The integration of cognitive architectures like ACT-R provides sophisticated frameworks for understanding and predicting adherence dynamics, while diagram completion interventions and reinforcement strategies address fundamental cognitive and motivational mechanisms. Future research should prioritize several key areas:

- Extended Intervention Durations: Explore sustained adherence mechanisms beyond short-term interventions to support long-term weight maintenance [1] [2]

- Social Cognitive Integration: Incorporate social cognitive factors more comprehensively into dynamic models to capture nuanced behavioral compliance insights [1]

- Adaptive Intervention Frameworks: Develop dynamic models capable of informing just-in-time adaptive interventions that respond to individual adherence patterns [1] [4]

- Individualized Reinforcement Schedules: Investigate optimal reinforcement timing and methodologies tailored to individual differences and response patterns [7] [3]

As digital technologies continue to evolve, their integration with established behavioral principles and cognitive frameworks will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated and effective self-monitoring interventions, ultimately enhancing their impact on global obesity prevention and management efforts.

Linking Self-Monitoring Adherence to Improved Health and Weight Loss Outcomes

Self-monitoring of dietary intake is widely recognized as the cornerstone of behavioral weight loss interventions [8]. This adherence is positively correlated with significant improvements in health behaviors and physiological outcomes, including successful weight loss and long-term weight maintenance [1]. However, participant adherence to these self-monitoring practices often wanes over time due to their labor-intensive nature and the absence of efficient passive recording methods [1]. Within the broader thesis of dietary intervention compliance research, understanding and enhancing the dynamics of self-monitoring adherence is paramount. This guide synthesizes current research and quantitative models to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for analyzing adherence and developing more effective, data-driven interventions.

Quantitative Evidence and Data Synthesis

Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates a significant association between the frequency of self-monitoring and successful weight loss outcomes [8]. Recent studies have begun to quantify the specific thresholds of adherence required to achieve and maintain weight loss.

Table 1: Association Between Self-Monitoring Adherence and Weight Loss Outcomes

| Study / Intervention Type | Sample Size & Groups | Self-Monitoring Metric | Key Quantitative Finding on Weight Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Behavioral Weight Loss Program (ACT-R Model) [1] [2] | Total N=97• Self-management (n=49)• Tailored feedback (n=23)• Intensive support (n=25) | Model adherence over 21 days (Root Mean Square Error) | • Self-management RMSE: 0.099• Tailored feedback RMSE: 0.084• Intensive support RMSE: 0.091 |

| Internet-Based Weight Loss Program [9] | n=75 adults with overweight/obesity | Days per week of dietary self-monitoring | • 3-4 days/week: Supports weight loss maintenance.• 5-6 days/week: Supports additional weight loss. |

| Internet Behavior Therapy [8] | n=46 | Number of online diaries submitted | Correlation between diaries submitted and weight loss: r = -0.50, p=0.001 |

| 8-Week Descriptive Study [8] | n=59 | Therapist ratings of self-monitoring consistency | Correlation between consistency and weight change: r = -0.35, p<0.007 |

Furthermore, research into the cognitive mechanisms underlying adherence reveals distinct patterns. One study visualized the contributions of goal pursuit and habit formation mechanisms, finding that goal pursuit remained dominant throughout a 21-day intervention, while the influence of habit formation diminished in the later stages [1]. This suggests that long-term adherence may rely more on conscious, goal-directed effort than on automaticity, a crucial insight for designing sustained interventions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: ACT-R Modeling of Adherence Dynamics

This protocol outlines the procedure for developing a prognostic computational model to analyze adherence dynamics, as described in recent research [1].

- 1. Objective: To develop a prognostic model for adherence to self-monitoring of dietary behaviors using the Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture and to qualitatively investigate adherence dynamics and the impact of various interventions.

- 2. Participant Recruitment:

- Population: Target adults who express a willingness to improve their lifestyle.

- Assignment: Randomly assign participants to one of three intervention groups:

- Group 1: Self-management. Participants use self-monitoring tools with minimal external support.

- Group 2: Tailored feedback. Participants receive personalized nutritional feedback based on their logged data.

- Group 3: Intensive support. Participants receive tailored feedback combined with emotional social support.

- 3. Intervention Delivery:

- Utilize a digital platform (e.g., mobile application) for self-monitoring of dietary behaviors.

- The tailored feedback allows participants to compare their dietary behaviors with healthy standards.

- Emotional social support is characterized by emotional communication, care, and understanding, potentially delivered via support groups or coach communication [1].

- 4. Data Collection & Modeling:

- Duration: Collect self-monitoring adherence data over a minimum of 21 days.

- Cognitive Modeling: Use the ACT-R architecture to model adherence.

- The model focuses on two key cognitive mechanisms: goal pursuit and habit formation.

- Predictor and outcome variables are defined as adjacent elements in the sequence of self-monitoring behaviors.

- The model simulates how declarative memory (chunks) and procedural memory (production rules) are retrieved and updated based on activation and utility, respectively [1].

- 5. Data Analysis:

- Model Performance: Evaluate the model using Mean Square Error, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and goodness-of-fit statistics.

- Mechanistic Analysis: Visualize the contributions of the goal pursuit and habit formation mechanisms over time to analyze adherence patterns.

- Group Comparison: Analyze differences in model parameters and mechanistic contributions between the three intervention groups to assess the impact of tailored feedback and social support.

Protocol: Determining the Dose-Response Relationship

This protocol is based on research aimed at establishing frequency thresholds for effective self-monitoring [9].

- 1. Objective: To identify the frequency of dietary self-monitoring required for successful weight loss maintenance and additional weight loss.

- 2. Study Design: Prospective analysis of data from a three-month, internet-based behavioral weight loss program.

- 3. Participants: 75 adults with overweight or obesity.

- 4. Data Collection:

- Monitor and record the frequency of dietary self-monitoring (days per week) throughout the program and into the maintenance phase.

- Track weight loss outcomes objectively.

- 5. Data Analysis:

- Explore various thresholds for dietary self-monitoring.

- Correlate specific frequency ranges (e.g., 1-2, 3-4, 5-7 days per week) with weight loss maintenance and continued weight loss.

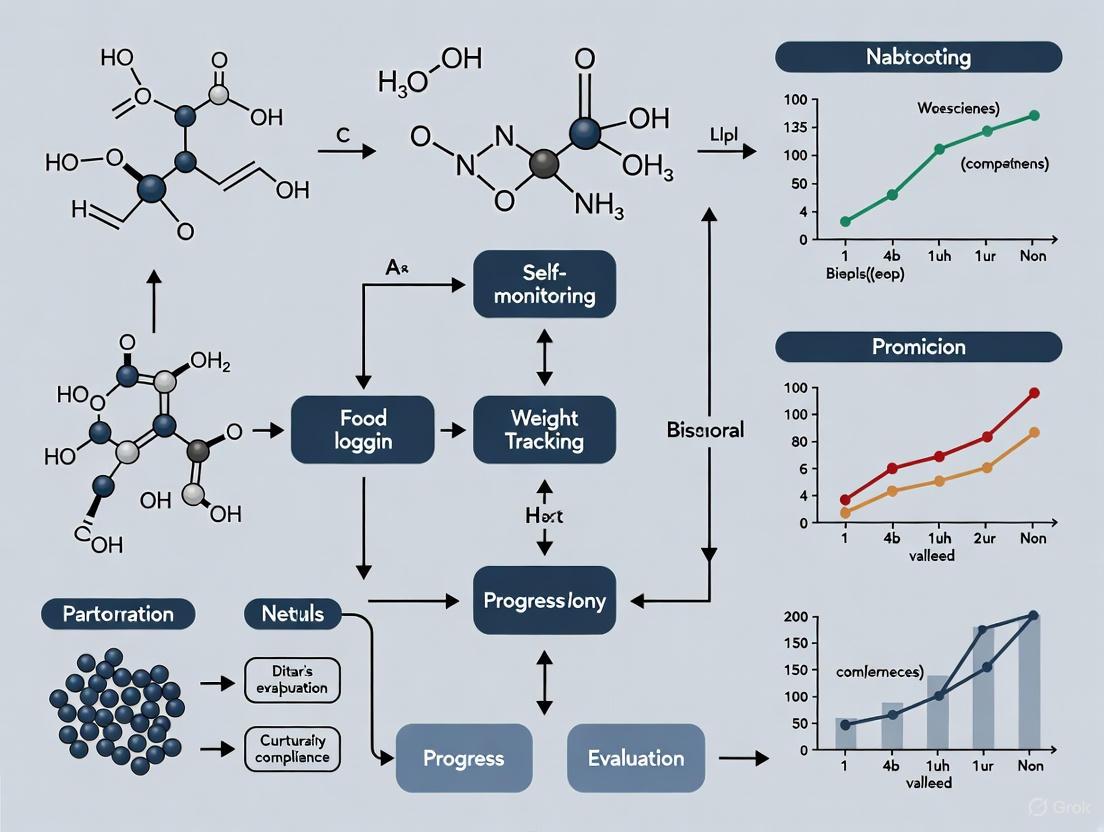

Visualizing Logical Relationships and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and workflows discussed in this guide.

Cognitive & Behavioral Model of Adherence

ACT-R Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Digital Tools for Self-Monitoring Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Self-Monitoring Platform | Core tool for participants to log dietary intake and for researchers to collect continuous, fine-grained data. | Mobile applications or web-based diaries; superior adherence compared to paper-based methods [1]. |

| Computational Cognitive Architecture (ACT-R) | Framework for developing prognostic models of adherence dynamics by simulating human cognitive processes like memory retrieval and rule utility [1]. | Open-source cognitive architecture; can be used to model the tension between goal pursuit and habit formation. |

| Tailored Feedback Algorithm | Generates personalized nutritional feedback for participants based on their logged data, enhancing engagement and goal pursuit. | Allows participants to compare their behaviors with healthy standards, providing directly relevant information [1]. |

| Social Support Integration Module | A structured system for delivering emotional social support within the digital platform to mitigate self-regulatory depletion. | Can include support groups, coach messaging, or forums; characterized by emotional communication and understanding [1]. |

| Color Contrast Analyzer | Ensures that all text and graphical elements in research tools and visualizations meet WCAG 2 AA contrast ratio thresholds for accessibility. | Critical for inclusive study design; minimum ratio of 4.5:1 for small text and 3:1 for large text [10] [11]. |

Understanding the Global Challenge of Overweight and Obesity

Overweight and obesity represent a critical global health crisis, characterized by excessive fat deposits that can impair health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), this complex chronic disease has reached pandemic proportions, with 1 in 8 people worldwide living with obesity in 2022. The global prevalence of obesity among adults has more than doubled since 1990, while adolescent obesity has quadrupled, creating unprecedented public health challenges and economic burdens across healthcare systems worldwide [12].

This escalating epidemic is not confined to high-income nations. Low- and middle-income countries face a double burden of malnutrition, where undernutrition coexists with rising obesity rates, often within the same communities and households. The economic impacts are staggering, with global costs of overweight and obesity predicted to reach US$3 trillion per year by 2030 and more than US$18 trillion by 2060 if no effective interventions are implemented [12]. Understanding the dynamics of this crisis and developing evidence-based interventions, particularly those leveraging dietary self-monitoring techniques, is paramount for researchers and healthcare professionals seeking to reverse these trends.

Epidemiological Landscape: Quantifying the Crisis

The global scale of overweight and obesity requires precise quantification to inform public health policy and intervention strategies. The following tables summarize key epidemiological data that illustrate the scope and distribution of this health challenge.

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity (2022) [12]

| Population Group | Overweight Prevalence | Obesity Prevalence | Affected Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (18+ years) | 43% (2.5 billion) | 16% (890 million) | Total: 2.5 billion |

| Children (5-19 years) | 20% (390 million) | 8% (160 million) | Total: 390 million |

| Children (<5 years) | Not specified | 35 million | Not applicable |

Table 2: Regional Variation in Adult Overweight Prevalence (2022) [12]

| WHO Region | Prevalence of Overweight |

|---|---|

| African Region | 31% |

| South-East Asia Region | 31% |

| Region of the Americas | 67% |

| Global Average | 43% |

The World Obesity Federation's 2025 Atlas projects that these trends will continue their alarming trajectory, with the total number of adults living with obesity expected to increase by more than 115% between 2010 and 2030, rising from 524 million to 1.13 billion [13]. This projection underscores the urgent need for effective interventions. Furthermore, the majority of countries lack sufficient plans and policies to address rising obesity levels, with only 7% of countries having health systems adequately prepared to manage this crisis [13].

Etiology and Health Consequences

Multifactorial Causes

Obesity pathogenesis involves complex interactions between environmental, psychosocial, genetic, and physiological factors. The fundamental energy imbalance—where energy intake consistently exceeds energy expenditure—manifests within what researchers term "obesogenic environments" [12]. These environments are characterized by structural factors that limit the availability of healthy, sustainable food at affordable prices, coupled with lack of safe opportunities for physical mobility integrated into daily life. In a subgroup of patients, single major etiological factors can be identified, including medications, underlying diseases, immobilization, iatrogenic procedures, and monogenic diseases or genetic syndromes [12].

Health Consequences and Comorbidities

The health risks associated with overweight and obesity are extensive and well-documented. In 2021, higher-than-optimal BMI caused an estimated 3.7 million deaths from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers, neurological disorders, chronic respiratory diseases, and digestive disorders [12]. Childhood and adolescent obesity not only affect immediate health but are associated with greater risk and earlier onset of various NCDs, with significant adverse psychosocial consequences, including stigma, discrimination, and bullying that affect school performance and quality of life [12].

Dietary Self-Monitoring: A Cornerstone Intervention

Theoretical Foundations and Implementation

Dietary self-monitoring represents a cornerstone of behavioral obesity treatment, grounded in self-regulation theory which posits that self-evaluation and self-reinforcement are necessary for behavior change [14]. This technique requires individuals to maintain awareness of their dietary actions, thereby supporting the development of self-regulation skills. As a behavior change technique, self-monitoring functions by increasing self-awareness of one's actions and the conditions under which they occur, helping to bridge the "intention-behaviour gap" that individuals often experience when attempting to modify dietary patterns [15].

Traditional dietary self-monitoring involves comprehensive recording of all foods and beverages consumed, typically using paper logs where participants look up nutrient content and calculate total intake. However, this approach is labor-intensive and adherence decreases over time, prompting researchers to develop innovative implementation strategies [14]. Current self-monitoring formats include:

- Paper-based records: Traditional food diaries and journals

- Digital platforms: Websites and applications (e.g., MyFitnessPal)

- Mobile applications: Smartphone-based tracking tools

- Hybrid approaches: Combination of digital and personal support

Table 3: Dietary Self-Monitoring Implementation Characteristics [14]

| Implementation Aspect | Options | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Format | Paper, website, mobile app, phone | Mobile apps show superior adherence to paper-based tools |

| Intensity | All intake vs. specific components | Higher intensity tracks complete diet; lower intensity focuses on specific behaviors/foods |

| Frequency | Real-time, daily, intermittent | More frequent monitoring associated with better outcomes but potential lower adherence |

| Feedback | Automated, personal, none | Tailored feedback enhances engagement and effectiveness |

The Adherence Challenge and Innovative Solutions

Despite its established efficacy, adherence to dietary self-monitoring remains a significant challenge. Evidence indicates that adherence decreases within the first three to five weeks for paper-based tools and during the fourth to ninth week for mobile applications [15]. This decline is primarily driven by the complexity and time-consuming nature of current tools, which often require numeracy, health literacy, and technological skills that may not be universally available.

Innovative approaches are emerging to address these adherence challenges. The plate-based approach, as exemplified by the iCANPlateTM mobile application, represents a promising alternative to traditional itemized tracking [15]. This method utilizes a visual representation of a plate divided according to the Canada Food Guide (half vegetables and fruits, one-quarter protein, one-quarter whole grains), allowing users to record meals by adjusting proportions rather than counting calories or specifying serving sizes. This simplified approach reduces cognitive burden and may enhance long-term adherence, particularly for populations with varying levels of health literacy [15].

Digital technologies offer significant advantages for self-monitoring adherence, including date and time stamps, instant feedback, and reminder signals that reduce the self-monitoring burden [15]. A 2025 study exploring the dynamics of dietary self-monitoring adherence in a digital behavioral weight loss program utilized the Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture to model adherence patterns [1]. The findings indicated that tailored feedback combined with intensive support significantly improved adherence, with the goal pursuit mechanism remaining dominant throughout the intervention period across all study groups [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Systematic Review Methodology for Self-Monitoring Strategies

To evaluate the effectiveness of dietary self-monitoring implementation strategies, researchers have conducted systematic reviews following rigorous methodological protocols [14]:

Search Strategy:

- Comprehensive searches across eight databases (Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost CINAHL)

- No language restrictions but restricted to human subjects

- Grey literature searches in Embase for conference materials, dissertations, and unpublished studies

- Reference searches within included articles

Study Selection Criteria:

- Population: Adults with overweight/obesity

- Intervention: Weight loss interventions incorporating dietary self-monitoring as a behavior change technique

- Comparators: Control groups with usual care, wait list, or distinct interventions without identical self-monitoring procedures

- Outcomes: Weight loss as primary outcome

- Study Design: RCTs, experimental, longitudinal designs

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment:

- General study characteristics (author, year, country, design, sample size)

- Self-monitoring implementation details (platform, recording processes, feedback mechanisms)

- Adherence metrics and intensity of dietary reporting

- Risk of bias assessment using appropriate tools

Nutritional Intervention Protocol for Adolescent Athletes

A 12-week evidence-based nutritional intervention program developed for adolescent athletes exemplifies the integration of self-monitoring within a comprehensive behavioral change framework [16]. This protocol employs the 5 A's behavioral change model (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) combined with motivational interviewing techniques:

Phase 1: Assessment (Week 1)

- Collect baseline anthropometric measurements (height, weight, BMI, body composition)

- Administer questionnaires on nutritional knowledge, eating habits, water intake, sleep time

- Complete 3-day food records to establish baseline nutrient intake

- Identify specific nutritional problems (e.g., insufficient energy intake, inadequate carbohydrate consumption, vitamin deficiencies)

Phase 2: Group Education Sessions (Weeks 1-12)

- Four 40-minute group sessions covering:

- Basic nutrition concepts (regular eating intervals, hydration, healthy body image)

- Basic food skills (meal planning, cooking skills, nutrient enhancement, food safety)

- Performance nutrition (fueling before, during, and after exercise)

- Performance enhancement (body composition optimization, supplement safety)

Phase 3: Individualized Counseling (Weeks 2-11)

- Four 20-30 minute individual counseling sessions implementing the 5 A's model:

- Assess: Nutritional status, dietary habits, nutrient intake

- Advise: Specific information on health risks and benefits of change

- Agree: Collaborative goal-setting based on participant interest and confidence

- Assist: Identify barriers, strategies, problem-solving techniques

- Arrange: Follow-up plan through visits, phone calls, reminders

Phase 4: Ongoing Support (Weeks 1-12)

- Regular phone calls and mobile messages for reinforcement

- Continuous monitoring of self-reported dietary intake

- Adjustment of goals based on progress and challenges

Personal Health Support Model for Hypertension Management

The Personal Health Support Model (PHSM) represents an advanced computational approach to dietary intervention that incorporates self-monitoring principles for managing obesity-related conditions such as hypertension [17]. This model integrates multiple methodologies:

Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP):

- Structures user preferences into a hierarchy

- Assigns appropriate weights through pairwise comparisons

- Focuses on DASH diet principles and lifestyle choices

Fuzzy Multi-Choice Goal Programming (FMCGP):

- Associates each nutritional goal with multiple aspiration levels

- Captures flexible and ambiguous nature of individual dietary preferences

- Ensures clinically appropriate and personally tailored dietary plans

Nonlinear Multi-Segment Goal Programming (NLMSGP):

- Captures nonlinear effects of food consumption

- Incorporates both quantity and timing of food intake

- Uses vector-based coefficients for accurate representation

This integrated model generates personalized daily dietary menus and lifestyle recommendations based on individual factors including gender, age, activity level, and dietary preferences, while adhering to clinical guidelines for hypertension management [17].

Visualization of Key Processes and Relationships

Dietary Self-Monitoring Adherence Dynamics

Diagram 1: Self-Monitoring Adherence Dynamics

5 A's Behavioral Model with Motivational Interviewing

Diagram 2: 5 A's Behavioral Change Model

Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| ACT-R Cognitive Architecture | Computational modeling of adherence dynamics; simulates goal pursuit and habit formation mechanisms | Modeling dietary self-monitoring adherence over 21-day interventions; predicting long-term adherence patterns [1] |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | Assessment of individual intake over previous 24 hours; multiple recalls capture habitual intake | Automated Self-Administered 24HR (ASA-24) reduces interviewer burden; collects multiple non-consecutive day recalls [18] |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assessment of usual intake over extended periods; categorizes food frequency consumption | Semi-quantitative FFQs query portion sizes and frequency; population-specific adaptations for different cultural contexts [18] |

| Digital Self-Monitoring Platforms | Mobile applications and websites for real-time dietary tracking; reduces burden of traditional methods | iCANPlateTM application using plate-based approach; MyFitnessPal for traditional itemized tracking [15] |

| Recovery Biomarkers | Objective validation of self-reported dietary data; measures energy, protein, sodium, potassium | Doubly labeled water for energy expenditure; urinary nitrogen for protein intake; sodium and potassium as objective intake measures [18] |

| FMCGP/NLMSGP Models | Computational optimization of personalized dietary plans; handles multi-criteria decision making | Personal Health Support Model for hypertension management; generates tailored DASH diet recommendations [17] |

The global challenge of overweight and obesity requires multifaceted intervention strategies, with dietary self-monitoring emerging as a critical component of effective behavioral treatments. Current evidence indicates that simplified approaches, such as plate-based monitoring, digital technologies, and personalized feedback systems, can significantly enhance adherence to self-monitoring protocols and improve weight loss outcomes. The integration of computational modeling, cognitive architectures, and advanced behavioral frameworks offers promising avenues for developing more effective, personalized interventions that can be scaled to address this pressing global health crisis. Future research should focus on extending intervention durations to explore sustained adherence mechanisms, integrating social cognitive factors to capture behavioral compliance insights, and adapting dynamic models to inform just-in-time adaptive interventions for broader applications [1].

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), pioneered by Albert Bandura, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how people acquire and maintain behavioral patterns, making it particularly relevant for dietary intervention compliance research [19]. This theory posits that human functioning results from a dynamic, reciprocal interaction between personal cognitive factors, behavioral patterns, and environmental influences—a concept known as triadic reciprocal causation or reciprocal determinism [20]. Within this triad, self-regulation emerges as a central mechanism through which individuals exercise control over their thoughts, feelings, and actions to achieve desired goals [19].

When applied to dietary interventions, SCT helps explain the psychological processes that facilitate or hinder adherence to nutritional guidelines. Self-regulation enables individuals to set dietary goals, monitor their food intake, and adjust their behavior in alignment with their health objectives [21]. Research consistently demonstrates that self-regulation capacity is a critical determinant of successful dietary behavior change and long-term maintenance [22]. This technical guide examines the core constructs of SCT and self-regulation, their operationalization in dietary research, and their application for improving compliance in nutritional interventions.

Core Theoretical Constructs and Mechanisms

Reciprocal Determinism in Dietary Contexts

Reciprocal determinism describes the continuous, mutual interaction between three distinct factors: personal/cognitive, behavioral, and environmental [20]. In dietary contexts, these interactions create complex feedback loops that either support or undermine intervention compliance.

- Personal/Cognitive Factors: These include nutrition knowledge, dietary self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulatory capacity. For example, an individual's belief in their ability to resist unhealthy foods (self-efficacy) influences their dietary choices [23].

- Behavioral Factors: These encompass specific dietary behaviors, such as food recording, meal timing, and macronutrient composition. Successful behaviors (e.g., achieving daily fruit and vegetable targets) reinforce positive cognitive factors.

- Environmental Factors: These include the physical environment (e.g., home food availability), social context (e.g., family eating patterns), and structural factors (e.g., access to healthy foods) [21].

The dynamic interplay between these factors means that change in one component inevitably influences the others. For instance, nutritional education (targeting cognitive factors) can increase healthy food purchasing (behavior), which subsequently alters the home food environment [20].

Self-Regulation: Components and Subfunctions

Self-regulation represents the executive function through which individuals manage their goal-directed behaviors [24]. In dietary contexts, effective self-regulation involves three interconnected subprocesses:

- Self-Observation: Systematic monitoring of one's food intake, often through food diaries, digital tracking, or mindful eating practices [24].

- Self-Judgment: Comparing monitored behavior against personal dietary standards or goals (e.g., evaluating daily food consumption against recommended nutritional guidelines).

- Self-Reaction: Implementing corrective actions when discrepancies between actual and desired eating behaviors are detected, and engaging in self-reinforcement when goals are achieved [24].

These subprocesses function cyclically, creating an ongoing feedback system that enables individuals to adjust their dietary behaviors in response to changing circumstances and progress toward goals.

Self-Efficacy and Outcome Expectations

Self-efficacy refers to an individual's confidence in their ability to successfully execute behaviors required to produce specific outcomes [23]. In dietary contexts, this encompasses beliefs about one's capability to perform specific nutrition-related behaviors, such as resisting tempting foods, preparing healthy meals, or maintaining dietary records [22]. Research demonstrates that self-efficacy significantly predicts adherence to dietary self-monitoring and healthy eating patterns [23].

Outcome expectations represent the anticipated consequences of performing specific dietary behaviors [20]. These expectations include:

- Physical outcomes (e.g., weight loss, improved energy)

- Social outcomes (e.g., approval from healthcare providers)

- Self-evaluative outcomes (e.g., feelings of pride or self-satisfaction)

The motivational power of outcome expectations depends on both the perceived likelihood of the outcome and the value placed upon it by the individual.

Quantitative Evidence: SCT Constructs and Dietary Outcomes

Empirical research has consistently demonstrated significant relationships between SCT constructs and dietary behaviors across diverse populations. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Influence of SCT Domains on Physical Activity and Dietary Behavior in Type-2 Diabetes Patients (N=225) [23]

| SCT Domain | Correlation with Physical Activity | Correlation with Dietary Behavior | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy | r = .41 | Not Significant | p < .001 |

| Self-Regulation | r = .44 | r = .44 | p < .001 |

| Social Support | r = .35 | r = .35 | p < .001 |

| Outcome Expectancy | r = .33 | r = .33 | p < .05 |

Table 2: Contextual Factors Influencing Healthy Eating Self-Regulation (N=892) [21]

| Contextual Factor | Effect on Self-Regulation | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Meal Moment (Breakfast vs. Dinner) | Higher at breakfast (Estimate = -0.08) | p < .001 |

| Location (Home vs. Out-of-Home) | Higher at home (Estimate = -0.08) | p < .001 |

| Tiredness | Negative influence (Estimate = 0.04) | p < .001 |

| Distractedness | Negative influence (Estimate = 0.07) | p < .001 |

| Intrinsic Motivation (Between-Individual) | Positive influence (Estimate = 0.19) | p < .001 |

| Self-Efficacy (Between-Individual) | Positive influence (Estimate = 0.41) | p < .001 |

Table 3: Association Between Self-Regulation of Eating Behavior (SREB) and Health Outcomes in Saudi Arabian Adults (N=651) [22]

| Outcome Variable | Association with SREB | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | Negative correlation (β = -0.13) | p < .001 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Negative correlation (β = -0.10) | p = 0.01 |

| Daily Fruit Consumption | Positive association (OR = 2.90) | p = 0.003 |

| Regular Breakfast Consumption | Positive association (OR = 1.64) | p = 0.04 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Longitudinal Observational Study on Self-Regulation Fluctuations

Objective: To investigate within-individual variability in healthy eating self-regulation across different meal moments and contexts [21].

Participants: 892 adults (Mean age = 44.3 ± 12.7 years).

Design:

- Within-subjects observational study with 9 repeated measurements over 3 weeks.

- Data collection occurred three times weekly before meal moments.

- Participants reported self-regulation levels, tiredness, distractedness, social context, and physical environment.

Measures:

- Self-regulation of healthy eating: Assessed via self-report before meals.

- Within-individual predictors: Meal moment, tiredness, distractedness, social environment, physical location.

- Between-individual predictors: Self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, perception of social and physical opportunity (measured at baseline).

Statistical Analysis: Random intercept and slopes model accounting for both within-individual and between-individual variables.

Digital Behavioral Weight Loss Program with ACT-R Modeling

Objective: To develop a prognostic model for adherence to dietary self-monitoring using the Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture [1].

Participants: 97 adults in a digital weight loss program.

Intervention Groups:

- Self-management group (n=49)

- Tailored feedback group (n=23)

- Intensive support group (n=25)

Procedure:

- 21-day intervention focusing on goal pursuit and habit formation mechanisms.

- ACT-R architecture simulated human cognitive processes including activation, retrieval, learning, and selection.

- Model performance evaluated using mean square error, root mean square error (RMSE), and goodness of fit.

Key ACT-R Mechanisms:

- Activation: Calculation of chunk activation level based on frequency and recency of access.

- Retrieval: Selection of knowledge chunks from declarative memory based on activation levels.

- Learning: Calculation of production rule utility through repeated execution and reward accumulation.

- Selection: Choice of which production rule to execute based on utility values.

Self-Regulation Strategy Training Intervention

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of situation-based strategies and cognitive reappraisal for promoting healthy eating behaviors [25].

Participants: 360 adults.

Design: Longitudinal intervention with assessment of short-term (2 weeks) and long-term (2 months) effects.

Experimental Conditions:

- Situation-based strategy training targeting healthy foods

- Situation-based strategy training targeting unhealthy foods

- Cognitive reappraisal training targeting healthy foods

- Cognitive reappraisal training targeting unhealthy foods

- Control group (no training)

Measures:

- Food cravings (healthy and unhealthy foods)

- Resistance to unhealthy foods

- Actual consumption of unhealthy foods

- Transfer effects across food categories

Visualization of Theoretical Mechanisms

Observational Learning Processes in Dietary Contexts

Bandura identified four cognitive processes that must occur for observational learning to successfully take place [20]. These processes are particularly relevant when individuals learn healthy eating behaviors through observation of role models, healthcare providers, or peers.

Self-Regulatory Feedback Loop in Dietary Management

The self-regulation process in dietary management operates through a continuous feedback cycle where individuals monitor, evaluate, and adjust their eating behaviors in relation to their dietary goals [24].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for SCT Dietary Research

Table 4: Essential Research Instruments and Their Applications in SCT Dietary Studies

| Research Instrument | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Regulation of Eating Behavior Questionnaire (SREBQ-5) | Assesses cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes in eating control [22] | Measuring capacity to regulate food intake according to personal goals in Saudi Arabian population study [22] |

| Social Cognitive Theory Questionnaire for Physical Activity & Dietary Behavior | Evaluates four SCT domains: self-efficacy, self-regulation, social support, and outcome expectancy [23] | Examining correlations between SCT domains and physical activity/dietary behavior in type-2 diabetes patients [23] |

| Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP-II) | Measures health-promoting behaviors across six subscales, including nutrition and physical activity [23] | Assessing dietary habits and physical activity patterns in conjunction with SCT constructs [23] |

| Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) Architecture | Computational implementation of cognitive processes for behavioral modeling [1] | Simulating adherence to dietary self-monitoring and evaluating intervention effectiveness in digital weight loss program [1] |

| Digital Food Recording Tools | Enable real-time tracking of dietary intake and eating patterns [1] | Facilitating self-monitoring component of self-regulation in behavioral weight loss interventions [1] |

Social Cognitive Theory and self-regulation constructs provide robust theoretical frameworks for understanding and improving dietary intervention compliance. The empirical evidence demonstrates significant relationships between SCT domains (particularly self-efficacy and self-regulation) and successful dietary outcomes across diverse populations [23] [22]. Contextual factors, including meal timing, location, and cognitive state, significantly influence self-regulatory capacity and should be considered in intervention design [21].

Future research should extend intervention durations to explore sustained adherence mechanisms and further integrate social cognitive factors into dynamic computational models [1]. The development of just-in-time adaptive interventions based on SCT principles represents a promising approach for enhancing dietary compliance through personalized support [1]. Additionally, research should examine the neural mechanisms underlying dietary self-regulation to further elucidate the biological substrates of successful behavior change.

For researchers and drug development professionals, incorporating SCT-based interventions that target self-regulatory skills, enhance self-efficacy, and modify outcome expectations can significantly improve adherence to dietary protocols in clinical trials and therapeutic interventions. The methodological approaches and assessment tools outlined in this guide provide a foundation for rigorously evaluating these intervention components.

The Persistent Challenge of Adherence Decay Over Time

Adherence decay, the decline in participant engagement with intervention requirements over time, presents a fundamental challenge in clinical and behavioral nutrition research. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in dietary interventions where self-monitoring—the systematic observation and recording of one's own food intake—is a cornerstone behavioral strategy [14]. Despite the established efficacy of self-monitoring for initiating weight loss and improving dietary patterns, maintaining consistent participant engagement remains difficult [14] [1]. The labor-intensive nature of traditional tracking methods and the waning of initial motivation frequently undermine long-term compliance [14] [26]. Understanding the dynamics, underlying mechanisms, and potential mitigations for adherence decay is therefore critical for developing more effective and sustainable dietary interventions. This guide examines the current evidence and proposes structured methodologies for addressing this persistent issue within research contexts.

Quantitative Evidence of Adherence Decay

Empirical studies across diverse populations and intervention types consistently report suboptimal and declining adherence rates, underscoring the pervasiveness of this challenge.

Table 1: Adherence Rates Across Different Health Contexts

| Health Context | Population | Adherence Metric | Rate | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension Management | Rural adults in Northeast China | Medication Adherence | 73.7% | [27] |

| Hypertension Management | Rural adults in Northeast China | Behavioral Adherence (e.g., lifestyle changes) | 29.3% | [27] |

| Hypertension Management | Rural adults in Northeast China | Dietary Adherence | 10.5% | [27] |

| DASH Diet | US Hypertensive Adults | Adherence to Dietary Recommendations | 19.4% | [27] |

| Multiple Health Behaviors | Chinese Adults (CKB Cohort) | Adherence to 6 key health behaviors | 0.7% | [27] |

The data in Table 1 reveals a clear hierarchy, with pharmacological adherence being more manageable for patients than sustained dietary or comprehensive lifestyle changes [27]. This highlights the particular difficulty of maintaining long-term behavioral modification.

In digital weight loss interventions, the relationship between self-monitoring engagement and outcomes is well-documented. A systematic review found that the majority of studies using both high- and low-intensity self-monitoring strategies demonstrated statistically significant weight loss compared to control groups [14]. However, this review also noted that participant adherence to these strategies typically declines over time because the practice is often perceived as labor-intensive and heavily reliant on continuous internal motivation [14].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Adherence

To systematically study and combat adherence decay, researchers are employing rigorous experimental designs. The following protocols detail key methodological approaches.

Protocol 1: Factorial Randomized Trial for Optimizing Self-Monitoring (Spark Trial)

This protocol is designed to identify the "active ingredients" of self-monitoring [26].

- Objective: To examine the unique and combined weight loss effects of three self-monitoring strategies: tracking dietary intake, tracking steps, and tracking body weight.

- Study Design: A 6-month, fully digital weight loss intervention using a 2 × 2 × 2 full factorial design. This creates eight experimental conditions to which participants are randomized.

- Participants: US adults with overweight or obesity (N=176).

- Intervention: For each assigned self-monitoring strategy, participants are instructed to self-monitor daily using commercially available digital tools (a mobile app, wearable activity tracker, and smart scale). They receive a corresponding goal and weekly automated feedback. All participants receive core intervention components, including weekly lessons and action plans informed by Social Cognitive Theory.

- Data Collection: Assessments occur at baseline, 1, 3, and 6 months. The primary outcome is weight change, measured objectively via a smart scale. Engagement is operationalized as the percentage of days self-monitoring occurs during the 6-month intervention.

Protocol 2: Cognitive Modeling of Adherence Dynamics

This protocol uses computational modeling to understand the cognitive mechanisms behind self-monitoring behavior [1].

- Objective: To develop a prognostic model for adherence to dietary self-monitoring using the Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture and to qualitatively investigate adherence dynamics.

- Study Design: Model development study using data from a digital behavioral weight loss program (Health Diary for Lifestyle Change). Participants were assigned to one of three groups: self-management, tailored feedback, or intensive support.

- Modeling Framework: The ACT-R architecture simulates human cognitive processes, focusing on two key mechanisms for self-monitoring adherence:

- Goal Pursuit: A conscious, effortful process driven by rewards and feedback.

- Habit Formation: An automatic process that strengthens with repeated behavior in a consistent context.

- Data Analysis: The model tracks adherence over 21 days, evaluating model performance using metrics like root mean square error (RMSE). The mechanistic contributions of goal pursuit and habit formation are visualized to analyze patterns.

Protocol 3: Pilot Feasibility Study for a Digital Nutrition Intervention

This protocol focuses on initial feasibility and acceptability before a larger-scale trial [28].

- Objective: To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a 4-week digital nutrition intervention to promote healthy and sustainable diets.

- Study Design: A pilot single-arm pre-post intervention study.

- Participants: 32 young adults (18–25 years) who are students or staff at Deakin University, Australia, and have low legume and nut intakes.

- Intervention: Delivery of the intervention via the Deakin Wellbeing mobile application for 4 weeks.

- Primary Outcomes: Feasibility (measured by retention rate) and acceptability (measured by engagement and user experience).

- Secondary Outcomes: Changes in sustainable food literacy, legume and nut intakes, and overall adherence to a healthy and sustainable diet.

Visualizing the Cognitive Mechanisms of Adherence

The ACT-R model provides a framework for understanding the cognitive processes that underlie self-monitoring behavior. The diagram below illustrates the interaction between the goal pursuit and habit formation systems, and how interventions can influence these systems to improve adherence.

Diagram 1: Cognitive Model of Adherence Dynamics

This diagram illustrates the two primary cognitive systems governing adherence. The Goal Pursuit System is dominant in the early and middle stages of an intervention, driven by conscious effort and reinforced by strategies like tailored feedback and social support [1]. The Habit Formation System strengthens with repeated behavior but often requires more time to become stable. Adherence decay occurs when the influence of the goal system wanes due to motivational depletion or high cognitive load, before robust habits have been formed [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2 outlines essential digital and methodological "reagents" for implementing and studying dietary self-monitoring interventions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Self-Monitoring Studies

| Item Name | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Deakin Wellbeing App | Digital Platform | A mobile application used as a delivery vehicle for intervention content and a tool to collect engagement metrics [28]. |

| Commercial Diet Tracking App | Digital Tool | Enables digital self-monitoring of dietary intake; allows researchers to test the effect of this strategy versus control conditions [26]. |

| Wearable Activity Tracker | Digital Tool | Enables self-monitoring of physical activity (e.g., steps); used to isolate the effect of this self-monitoring component [26]. |

| Smart Scale | Digital Tool | Provides objective weight data and facilitates self-monitoring of body weight with minimal participant effort [26]. |

| ACT-R Cognitive Architecture | Computational Model | A modeling framework to simulate and analyze the dynamic cognitive processes (goal pursuit vs. habit formation) behind adherence patterns [1]. |

| Standardized Questionnaires | Assessment Tool | Used to measure constructs like sustainable food literacy, knowledge, attitudes, and intentions at multiple time points [28] [27]. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recalls | Assessment Tool | A detailed dietary assessment method used to validate self-reported food intake and measure changes in specific food groups (e.g., nuts, legumes) [28]. |

Adherence decay is a multifaceted problem driven by behavioral, cognitive, and contextual factors. Tackling it requires a move from traditional "treatment package" approaches to optimized, personalized strategies. Research indicates that leveraging digital tools for reduced-burden self-monitoring, providing tailored feedback, and understanding the distinct cognitive pathways of goal pursuit and habit formation are promising directions. Future work should focus on extending intervention durations to study long-term habit stability, integrating real-time social cognitive data into dynamic models, and developing just-in-time adaptive interventions that can proactively deliver support when the risk of disengagement is predicted to be high [1]. By systematically applying these experimental protocols and leveraging the outlined research toolkit, scientists can develop more potent and durable dietary interventions.

Digital Tools, Cognitive Modeling, and Practical Application Frameworks

The Shift from Paper-Based to Digital Self-Monitoring Tools

The accuracy of dietary intake assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology and compliance research in clinical trials for drug development. Self-monitoring, the systematic observation and recording of one's own behaviors, is a critical technique for collecting this data [29]. For years, paper-based diaries were the standard tool for this purpose. However, the digital transformation has introduced a paradigm shift towards mobile applications and wearable technology, offering new possibilities for data quality, participant engagement, and real-time intervention [30] [31]. This shift is particularly relevant within dietary intervention compliance research, where the precision of dietary exposure data directly impacts the validity of findings on a drug's efficacy or a health intervention's outcomes. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a technical overview of this transition, summarizing quantitative evidence, detailing experimental methodologies, and presenting essential tools for implementing digital self-monitoring in rigorous scientific studies.

Quantitative Comparison: Paper-Based vs. Digital Tools

Empirical studies have directly compared the acceptability, adherence, and effectiveness of paper-based and digital self-monitoring tools. The data, summarized in the table below, reveal a nuanced landscape where digital tools are not universally superior but offer distinct advantages for specific demographics and outcomes.

Table 1: Key Findings from Comparative Studies on Self-Monitoring Tools

| Study & Population | Intervention Comparison | Acceptability & Adoption | Adherence & Effectiveness | Reported Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office Workers in Sri Lanka [30](Non-randomized trial, n=123) | Mobile application vs. paper-based tool for dietary intake. | 19.5% overall preferred mobile app. Significantly higher acceptance among younger, unmarried workers without children (p < 0.05). | No significant difference in adherence over 3 months or in the change to healthy dietary intake between groups. | Demographic factors (age, marital status) significantly influence acceptance of digital tools. |

| National Weight Control Registry (NWCR) [32](Survey, n=794; adults maintaining weight loss) | Technology (apps/websites) vs. paper-based methods for self-monitoring. | "Regain" group (gained ≥2.3kg) was more interested in technology for tracking weight and diet (p<0.01) than the "maintain" group. | Both groups used technology, but the "regain" group reported more negative feelings (guilt, discouragement) associated with tracking technology use (p<0.001). | Digital tools can be associated with negative emotional byproducts in certain populations, potentially affecting long-term compliance. |

| Systematic Review of Physical Activity [31](19 studies included) | Technology-assisted self-monitoring (e.g., fitness trackers, email feedback) vs. non-technological methods. | Fitness trackers were the most popular type of technology used. Technology reduced user response effort for self-recording. | Combined self-monitoring and technology interventions were effective at increasing physical activity across multiple populations. | The review highlighted the need for identifying the most effective methodologies for lasting behavior change. |

Experimental Protocols for Dietary Self-Monitoring Research

For researchers designing studies to evaluate self-monitoring tools, the following detailed methodologies provide a framework for rigorous experimentation. These protocols are adapted from recent peer-reviewed studies.

Protocol 1: Comparing Dietary Intervention Delivery Methods

This protocol is based on a non-randomized trial comparing a mobile application to a paper-based tool [30].

- Objective: To assess the acceptability and effectiveness of a mobile application versus a paper-based tool for monitoring dietary intake and promoting healthy eating.

- Population: Office workers identified as being in the preparation, action, or maintenance stages of the Trans-Theoretical Model (TTM) of behavior change. Exclusion criteria include jobs involving physical exertion and being on special dietary plans.

- Tool Development (Mobile App):

- Phase 1 (Design): Conduct an extensive literature review to identify evidence-based behavior change techniques (BCTs). Common effective BCTs include goal setting, self-monitoring, and providing information from credible sources [30].

- Phase 2 (Expert Consultation): Engage a panel of local experts in behavioral science, nutrition, and mobile health to refine the tool's layout and operationalize dietary portions and servings.

- Phase 3 (Software Development & Testing): Develop the application and conduct pre-testing and piloting in a non-study setting to refine functionality and user experience.

- Study Design: Non-randomized, open-label trial with two parallel arms (mobile app vs. paper-based). Participants self-select their preferred intervention method.

- Data Collection:

- Baseline: Collect socio-demographic data, general health status, and dietary behaviors via a self-administered questionnaire. Measure height and weight.

- Follow-up: Monitor adherence to the self-monitoring tool for three months.

- Outcome Assessment (3 months): The primary outcome is the progressive change in the stage of change (TTM). The secondary outcome is the change from unhealthy to healthy dietary intake, assessed via 24-hour dietary recall.

- Analysis: Compare outcomes between the two groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., chi-square for categorical data, t-tests for continuous data).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Dietary Guidelines in a Specific Population

This protocol outlines a qualitative approach to understanding the cultural acceptability of standardized dietary patterns, which is crucial for designing compliant digital tools [33].

- Objective: To explore the acceptability, perceptions, and cultural relevance of three U.S. Dietary Guidelines (USDG) dietary patterns (Healthy US, Mediterranean, Vegetarian) among African American adults.

- Population: Adults who self-identify as African American, with a BMI between 25-49.9 kg/m² and exhibiting ≥3 risk factors for type 2 diabetes.

- Intervention Structure:

- Duration: 12-week randomized controlled feeding trial.

- Components: Participants are randomized to one of the three USDG dietary patterns. All groups receive the same structure: weekly nutrition classes via Zoom, cooking demonstrations, behavioral strategies from the Diabetes Prevention Program, and use of the MyPlate app for tracking.

- Support: Weekly food samples are provided.

- Qualitative Data Collection:

- Method: Conduct focus group discussions (FGDs) upon completion of the intervention. Separate FGDs are held for each dietary pattern group.

- Tool: Use a semi-structured focus group guide developed based on Social Cognitive Theory and the Designing Culturally Relevant Intervention Development Framework. Questions probe self-efficacy, facilitators, barriers, and cultural tailoring needs.

- Analysis: Transcribe FGDs verbatim and analyze them thematically using a constant comparative method in qualitative data analysis software (e.g., NVivo).

- Outcome: Thematic insights into barriers, facilitators, and necessary adaptations to enhance cultural relevance and program adherence.

Workflow and System Architecture for Digital Self-Monitoring

The integration of digital self-monitoring into research involves a structured workflow from tool selection to data utilization. The diagram below illustrates this process and the logical architecture of a digital self-monitoring system.

Diagram 1: Dietary Assessment Research Workflow

The system architecture for a digital self-monitoring tool is built on a user-facing application and a researcher-facing data platform, as shown below.

Diagram 2: System Architecture for Digital Self-Monitoring

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing self-monitoring studies requires a suite of "research reagents"—both digital and methodological. The following table details these essential components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Self-Monitoring Studies

| Item Name | Type | Specifications & Functions | Key Considerations for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Health Application | Software | A smartphone app for real-time dietary logging, often incorporating Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) like goal setting and self-monitoring [30]. | Must be based on evidence-based BCTs and validated dietary assessment methods. Requires pre-testing and piloting. |

| Wearable Activity Tracker | Hardware/Software | Devices (e.g., Fitbit, accelerometers) that automatically track physical activity metrics like step count, heart rate, and sleep duration [31]. | Superior reliability and data richness compared to older tools like pedometers. Allows unobtrusive data collection. |

| Paper-Based Food Diary | Analog Tool | The traditional standard for dietary assessment, involving handwritten records of all food and beverages consumed. | Serves as an active comparator in studies. Prone to recall bias and back-filling, but has high familiarity. |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Methodological Tool | A structured interview to capture detailed dietary intake from the previous 24 hours, often used as a reference method for validation [30]. | Can be used to validate the data collected from primary self-monitoring tools (paper or digital). |

| Focus Group Guide | Methodological Tool | A semi-structured questionnaire based on theoretical frameworks (e.g., Social Cognitive Theory) to gather qualitative data on user experience and cultural acceptability [33]. | Essential for understanding the "why" behind quantitative results and for tailoring interventions to specific populations. |

| Best Practice Guidelines (DIET@NET) | Methodological Framework | A set of expert-consensus guidelines for selecting and implementing Dietary Assessment Tools (DATs) in health research [34]. | Provides a structured, 4-stage process (Define, Investigate, Select, Implement) to minimize measurement error and strengthen study design. |

The shift from paper-based to digital self-monitoring tools represents a significant evolution in dietary intervention compliance research. While digital tools offer profound advantages in data richness, real-time feedback, and reduced user burden, the evidence indicates that a one-size-fits-all approach is not optimal. Success depends on a nuanced strategy that considers the target population's demographic and psychological characteristics, employs rigorous tool development and validation protocols, and remains aware of potential emotional byproducts of tracking. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging best practice guidelines and selecting the appropriate "research reagents" are critical steps in harnessing the power of digital self-monitoring to generate high-quality, reliable data on dietary compliance and intervention efficacy.

Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) for Modeling Adherence Dynamics

Dietary self-monitoring is a cornerstone of behavioral weight loss programs, widely recognized for its effectiveness in promoting healthy behavior changes and improving health outcomes [2] [1]. However, participant adherence to self-monitoring of dietary behaviors tends to wane over time due to the labor-intensive nature of the approach and the absence of efficient passive recording methods [1] [35]. This adherence decay presents a significant challenge for researchers and clinicians seeking to optimize interventions for chronic conditions where dietary management is crucial.

The Adaptive Control of Thought-Rational (ACT-R) cognitive architecture offers a novel computational framework for modeling the dynamics of dietary adherence, simulating human cognitive processes to predict and explain how adherence patterns evolve throughout interventions [2] [1]. By leveraging ACT-R's mechanisms of goal pursuit and habit formation, researchers can move beyond descriptive, cross-sectional analyses to dynamic computational models that capture the fine-grained temporal relationships between interventions and behavioral outcomes [1] [35]. This approach represents a significant advancement in computational behavioral science, enabling more personalized and adaptive dietary interventions.

Theoretical Foundations of the ACT-R Architecture

ACT-R is a hybrid cognitive architecture that integrates physical, neurophysiological, behavioral, and cognitive mechanisms into a unified computational model [1] [35]. It operates through two interconnected systems: a symbolic system representing declarative and procedural knowledge, and a subsymbolic system managing the activation and utility of these knowledge structures through mathematical computations.

Architectural Components

The symbolic system comprises multiple modules, with the central procedural module serving as the core component that integrates all other modules [1] [35]. Each module corresponds to a specific brain region and interacts with associated buffers to retrieve and store information. The architecture posits two primary types of memory: (1) "chunks" residing in the declarative module, characterized by an "activation" attribute influenced by retrieval time, frequency, and recentness of access, and (2) "production rules" located in the procedural module, consisting of conditional statements ("if") and corresponding actions ("then") with a "utility" attribute determining execution likelihood [1].

The subsymbolic system governs operations within modules through four fundamental computational processes outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Core Computational Mechanisms in ACT-R's Subsymbolic System

| Mechanism | Description | Equation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation | Calculates the activation level of a chunk, comprising base-level activation and spreading activation | ( Ai = Bi + \sumj Wj S_{ji} ) | ( A ): activation level; ( B ): base-level activation; ( S ): spreading activation; ( t_i ): time since ith access; ( d ): decay rate |

| Retrieval | Selects and activates knowledge chunks from declarative memory | ( Pi = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(Ai - \tau)/s}} ) | ( P_r ): probability of retrieval; ( \tau ): retrieval threshold; ( s ): activation noise |

| Learning | Calculates the utility of production rules through reward accumulation | ( Ui(n) = Ui(n-1) + \alpha[Ri(n) - Ui(n-1)] ) | ( U ): utility of production rule; ( \alpha ): learning rate; ( R ): reward for rule execution |

| Selection | Chooses which production rule to execute based on utility values | ( Pi = \frac{e^{Ui/t}}{\sumj e^{Uj/t}} ) | ( P_s ): probability of selection; ( t ): temperature parameter |

Visualizing the ACT-R Framework for Dietary Adherence

The following diagram illustrates how ACT-R modules and mechanisms interact to model dietary self-monitoring behavior:

Diagram 1: ACT-R Architecture for Dietary Adherence

Experimental Implementation: Modeling Dietary Self-Monitoring

Study Design and Participant Allocation

A recent study implemented ACT-R modeling to analyze adherence dynamics in a digital behavioral weight loss program called Health Diary for Lifestyle Change (HDLC) [1] [35]. The study recruited adults expressing willingness to improve their lifestyle and assigned them to one of three intervention groups with varying support levels. Participant distribution and model performance metrics across these groups are summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Participant Allocation and ACT-R Model Performance Metrics

| Intervention Group | Sample Size | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | Key Adherence Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-management | 49 participants | 0.099 | Baseline adherence with minimal external support |

| Tailored Feedback | 23 participants | 0.084 | Improved adherence through personalized nutritional feedback |

| Intensive Support | 25 participants | 0.091 | Enhanced adherence via combined feedback and social support |

| Total Sample | 97 participants | - | Goal pursuit remained dominant throughout intervention |

The modeling data captured adherence to self-monitoring of dietary behaviors over 21 days, with predictor and outcome variables defined as adjacent elements in the sequence of self-monitoring behaviors [2]. Model performance was evaluated using mean square error, root mean square error (RMSE), and goodness of fit measures, demonstrating ACT-R's capacity to effectively capture adherence trends across all intervention conditions [2] [1].

Experimental Protocol for ACT-R Implementation

Researchers implementing ACT-R modeling for dietary adherence dynamics should follow this detailed methodological workflow:

Diagram 2: ACT-R Experimental Implementation Workflow

Step 1: Participant Recruitment and Group Assignment

- Recruit adults expressing willingness to improve lifestyle behaviors