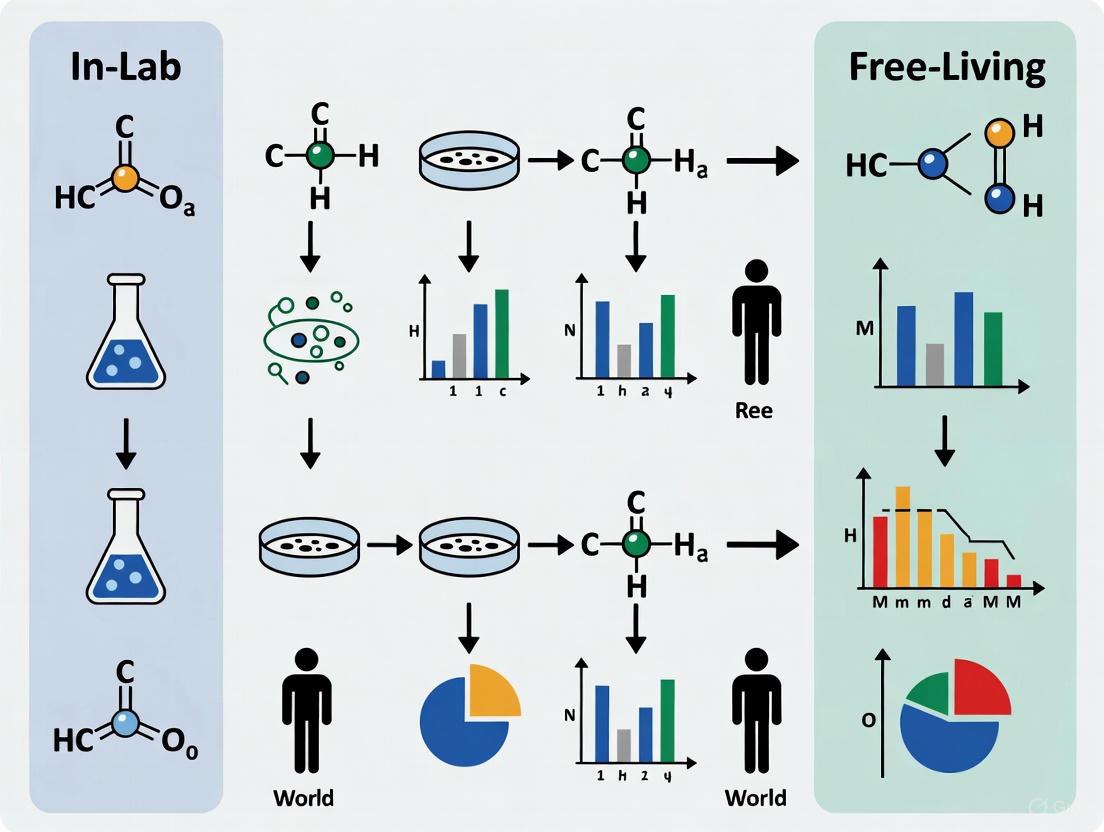

From Lab to Life: Evaluating Wearable Eating Detection Performance in Controlled vs. Free-Living Environments

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the performance of wearable sensors for automatic eating detection, contrasting controlled laboratory settings with free-living conditions.

From Lab to Life: Evaluating Wearable Eating Detection Performance in Controlled vs. Free-Living Environments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the performance of wearable sensors for automatic eating detection, contrasting controlled laboratory settings with free-living conditions. It explores the foundational principles of eating behavior sensing, details the array of methodological approaches from multi-sensor systems to algorithmic design, and addresses critical challenges such as confounding behaviors and participant compliance. A systematic comparison of validation metrics and real-world performance highlights the significant gap between in-lab efficacy and in-field effectiveness, offering insights for developing robust, translatable dietary monitoring tools for clinical research and public health.

The Science of Sensing Eating: From Basic Gestures to Complex Behavioral Inference

Automated dietary monitoring (ADM) has emerged as a critical field of research, seeking to overcome the limitations of traditional self-reporting methods such as food diaries and 24-hour recalls, which are often inaccurate and prone to misreporting [1]. The core principle underlying modern wearable eating detection systems is the measurement of behavioral and physiological proxies—detectable signals that correlate with eating activities. Rather than directly measuring food consumption, these devices monitor predictable patterns of chewing, swallowing, and hand-to-mouth gestures that collectively indicate an eating episode [2] [3]. This approach enables passive, objective data collection in both controlled laboratory settings and free-living environments, providing researchers with unprecedented insights into eating behaviors and their relationship to health outcomes such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [4] [5].

The fundamental challenge in this domain lies in the significant performance gap between controlled laboratory conditions and real-world environments. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of wearable eating detection technologies, focusing on their operational principles, experimental methodologies, and performance characteristics across different validation settings, with particular emphasis on the transition from laboratory to free-living conditions.

Taxonomical Framework of Eating Detection Proxies

Wearable eating detection systems employ a diverse array of sensors to capture physiological and behavioral proxies. The table below categorizes the primary sensing modalities, their detection targets, and underlying principles.

Table 1: Taxonomy of Wearable Sensors for Eating Detection

| Sensing Modality | Primary Proxies Detected | Measurement Principle | Common Placement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer/Gyroscope [1] [3] | Head movement (chewing), hand-to-mouth gestures, body posture | Measures acceleration and rotational movement | Head (eyeglasses), wrist, neck |

| Acoustic Sensors [3] [6] | Chewing sounds, swallowing sounds | Captures audio frequencies of mastication and swallowing | Neck (collar), ear |

| Bioimpedance Sensors [6] | Hand-to-mouth gestures, food interactions | Measures electrical impedance changes from circuit variations | Wrists |

| Piezoelectric Sensors [2] [3] | Jaw movements, swallowing vibrations | Detects mechanical stress from muscle movement and swallowing | Neck (necklace), throat |

| Strain Sensors [1] [3] | Jaw movement, throat movement | Measures deformation from muscle activity | Head, throat |

| Image Sensors [1] [5] | Food presence, food type, eating context | Captures visual evidence of food and eating | Chest, eyeglasses |

The compositional approach to eating detection combines multiple proxies to improve accuracy and reduce false positives. For instance, a system might predict eating only when it detects bites, chews, swallows, feeding gestures, and a forward lean angle in close temporal proximity [2]. This multi-modal sensing strategy is particularly valuable for distinguishing actual eating from confounding activities such as talking, gum chewing, or other hand-to-mouth gestures [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated Sensor-Image Validation (AIM-2 System)

Objective: To reduce false positives in eating episode detection by integrating image and accelerometer data [1].

Equipment: Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2) device attached to eyeglasses, containing a camera (capturing one image every 15 seconds) and a 3-axis accelerometer (sampling at 128 Hz) [1].

Protocol:

- Thirty participants wore the AIM-2 for two days (one pseudo-free-living and one free-living) [1].

- During pseudo-free-living days, participants consumed three lab meals while using a foot pedal to mark food ingestion as ground truth [1].

- During free-living days, participants went about normal activities while the device continuously collected data [1].

- Images were manually annotated with bounding boxes around food and beverage objects [1].

Analysis:

- Three detection methods were compared: (1) image-based food/beverage recognition, (2) accelerometer-based chewing detection, and (3) hierarchical classification combining both image and accelerometer confidence scores [1].

Bioimpedance Sensing for Activity Recognition (iEat System)

Objective: To recognize food intake activities and food types using bioimpedance sensing across wrists [6].

Equipment: iEat wearable device with one electrode on each wrist, measuring electrical impedance across the body [6].

Protocol:

- Ten volunteers performed 40 meals in an everyday table-dining environment [6].

- The system measured impedance variations caused by dynamic circuit changes during different food interactions [6].

- Activities included cutting, drinking, eating with hand, and eating with utensils [6].

Analysis:

- A lightweight, user-independent neural network classified activities and food types based on impedance patterns [6].

- The abstracted human-food circuit model interpreted impedance changes from parallel circuit branches formed during eating activities [6].

Multi-Sensor Free-Living Deployment (NeckSense System)

Objective: To capture real-world eating behavior in unprecedented detail with privacy preservation [5] [7].

Equipment: Multi-sensor system including NeckSense necklace (proximity sensor, ambient light sensor, IMU), HabitSense bodycam (thermal-sensing activity-oriented camera), and wrist-worn activity tracker [5] [7].

Protocol:

- Sixty adults with obesity wore the three sensors for two weeks while using a smartphone app to track meal-related mood and context [5] [7].

- The HabitSense camera used thermal sensing to trigger recording only when food entered the field of view, with privacy-enhancing blurring of non-essential elements [5].

Analysis:

- Sensor data was processed to detect chewing, bites, and hand-to-mouth gestures [5] [7].

- Pattern analysis identified five distinct overeating behaviors based on behavioral, psychological, and contextual factors [5] [7].

Performance Comparison: In-Lab vs. Free-Living Environments

The critical challenge in wearable eating detection is the performance discrepancy between controlled laboratory settings and free-living environments. The table below compares the performance metrics of various systems across these different validation contexts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Eating Detection Systems Across Environments

| System / Study | Sensing Modality | In-Lab Performance | Free-Living Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 (Integrated) [1] | Accelerometer + Camera | N/A (Pseudo-free-living) | 94.59% Sensitivity, 70.47% Precision, 80.77% F1-score | Image-based false positives from non-consumed foods |

| iEat [6] | Bioimpedance (wrists) | 86.4% F1 (activity), 64.2% F1 (food type) | Not separately reported | Performance dependent on food electrical properties |

| NeckSense (Swallow Detection) [2] | Piezoelectric sensor | 87.0% Accuracy (Study 1), 86.4% Accuracy (Study 2) | 77.1% Accuracy (Study 3) | Confounding from non-eating swallows, body shape variability |

| ByteTrack (Video) [8] | Camera (stationary) | 70.6% F1 (bite detection) | Not tested in free-living | Performance decrease with face occlusion and high movement |

The performance degradation in free-living conditions is consistently observed across studies. The integrated AIM-2 approach demonstrated an 8% improvement in sensitivity compared to either sensor or image methods alone, highlighting the value of multi-modal fusion for real-world deployment [1]. However, precision remains challenging, with the system correctly identifying eating episodes but also generating false positives from non-eating activities [1].

The NeckSense system exemplifies the laboratory-to-free-living performance gap, with accuracy dropping from approximately 87% in controlled lab studies to 77% in free-living conditions [2]. This degradation stems from confounding factors present in real-world environments, including varied body movements, non-food hand-to-mouth gestures, and the absence of controlled positioning [2].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The detection of eating proxies follows a structured signal processing pipeline. The diagram below illustrates the generalized workflow for multi-sensor eating detection systems.

The bioimpedance sensing mechanism represents a particularly innovative approach to detecting hand-to-mouth gestures and food interactions. The diagram below illustrates the dynamic circuit model that enables this detection method.

Research Reagent Solutions: Experimental Materials and Tools

The development and validation of wearable eating detection systems requires specialized hardware and software tools. The table below catalogues essential research reagents used in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Wearable Eating Detection Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2) [1] | Multi-sensor data collection (camera + accelerometer) | Eyeglasses-mounted device capturing images (every 15s) and head movement (128Hz) |

| iEat Bioimpedance System [6] | Wrist-worn impedance sensing for activity recognition | Two-electrode configuration measuring dynamic circuit variations during eating |

| NeckSense [5] [7] | Neck-worn multi-sensor eating detection | Proximity sensor, ambient light sensor, IMU for detecting chewing and gestures |

| HabitSense Bodycam [5] | Privacy-preserving activity-oriented camera | Thermal-sensing camera triggered by food presence with selective blurring |

| Foot Pedal Logger [1] | Ground truth annotation during lab studies | USB data logger for participants to mark food ingestion timing |

| Manual Video Annotation Tools [1] [8] | Ground truth establishment for image/video data | MATLAB Image Labeler application for bounding box annotation of food objects |

| Hierarchical Classification Algorithms [1] | Multi-sensor data fusion | Machine learning models combining confidence scores from image and sensor classifiers |

Wearable eating detection systems have demonstrated significant potential for objective dietary monitoring through the measurement of behavioral and physiological proxies. The integration of multiple sensing modalities—particularly the combination of motion sensors with image-based validation—has proven effective in reducing false positives and improving detection accuracy in free-living environments [1].

However, substantial challenges remain in bridging the performance gap between controlled laboratory settings and real-world conditions. Systems that achieve accuracy exceeding 85% in laboratory environments often experience performance degradation of 10-15% when deployed in free-living settings [1] [2]. Future research directions should focus on robust multi-sensor fusion algorithms, improved privacy preservation techniques, and adaptive learning approaches that can accommodate individual variations in eating behaviors [2] [3] [5].

The emergence of standardized validation protocols and benchmark datasets will be crucial for advancing the field and enabling direct comparison between different technological approaches. As these technologies mature, they hold the promise of delivering truly personalized dietary interventions that can adapt to individual eating patterns and contexts, ultimately contributing to more effective management of nutrition-related health conditions [5] [7].

Accurate dietary monitoring is a critical component of public health research and chronic disease management, particularly for conditions like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease [9] [3]. Traditional self-report methods such as food diaries and 24-hour recalls are plagued by inaccuracies, recall bias, and significant participant burden [1] [9]. Wearable sensor technologies have emerged as a promising solution, offering objective, continuous data collection with minimal user intervention [4].

However, a substantial performance gap exists between controlled laboratory environments and free-living conditions. Systems demonstrating high accuracy in lab settings often experience degraded performance when deployed in real-world scenarios due to environmental variability, diverse behaviors, and practical challenges like device compliance [10] [9]. The compositional approach—intelligently fusing multiple sensor modalities—represents the most promising framework for bridging this gap, enhancing robustness by leveraging complementary data streams to overcome limitations inherent in any single sensing method [1] [11].

This guide systematically compares the performance of multi-modal sensing systems against unimodal alternatives across both laboratory and free-living environments, providing researchers with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate methodologies for their specific applications.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Dietary Monitoring Systems

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sensor Systems for Eating Detection

| System / Method | Sensor Modalities | Environment | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 (Integrated Approach) [1] | Accelerometer (chewing), Camera (egocentric) | Free-living | 94.59% Sensitivity, 70.47% Precision, 80.77% F1-score | 8% higher sensitivity than single modalities; reduces false positives | Requires wearable apparatus; privacy concerns with camera |

| MealMeter [12] | Continuous glucose monitor, Heart rate variability, Inertial motion | Laboratory & Field | Carbohydrate MAE: 13.2g, RMSRE: 0.37 | High macronutrient estimation accuracy; uses commercial wearables | Limited validation in full free-living conditions |

| Sensor Fusion HAR System [13] | Multiple IMUs (wrists, ankle, waist) | Real-world & Controlled | Improved classification vs single sensors | Optimal positioning reduces sensor burden; ensemble learning | Focused on activity recognition vs. meal composition |

| Camera-Only Methods [1] [3] | Egocentric camera | Free-living | High false positive rate (13%) | Captures food context and type | Privacy concerns; irrelevant food detection (non-consumed) |

| Accelerometer-Only Methods [1] [3] | Chewing sensor/accelerometer | Free-living | Lower precision vs. multimodal | Convenient; no camera privacy issues | False positives from gum chewing, talking |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Different Testing Environments

| Study | System | Laboratory Performance | Free-Living Performance | Performance Gap Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 Study [1] | Multimodal (Image + Sensor) | Not reported | F1-score: 80.77% | Baseline free-living benchmark |

| MealMeter [12] | Physiological + Motion | High macronutrient accuracy | Limited data | Insufficient free-living validation |

| Previous Research [9] | Various wearable sensors | Significantly higher | Context-dependent degradation | Lab settings fail to capture real-world variability |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The AIM-2 Integrated Detection Protocol

The AIM-2 (Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2) system represents a comprehensive approach to multimodal eating detection, validated in both pseudo-free-living and free-living environments [1].

Device Specification: The AIM-2 sensor package attaches to eyeglass frames and incorporates three sensing modalities: a 3D accelerometer (sampled at 128 Hz) for detecting head movements and chewing, a flex sensor for chewing detection, and a 5-megapixel camera with a 170-degree wide-angle lens that captures egocentric images every 15 seconds [1] [10].

Study Protocol: The validation study involved 30 participants (20 male, 10 female, aged 18-39) who wore the device for two days: one pseudo-free-living day (meals consumed in lab, otherwise unrestricted) and one completely free-living day [1]. Ground truth was established through multiple methods: during lab meals, participants used a foot pedal to mark food ingestion events; during free-living, images were manually reviewed to annotate eating episodes [1].

Data Fusion Methodology: The system employs hierarchical classification to combine confidence scores from independent image-based and sensor-based classifiers [1]. Image processing uses deep learning to recognize solid foods and beverages, while accelerometer data analyzes chewing patterns and head movements. This fusion approach significantly outperforms either method alone, particularly in reducing false positives from non-eating activities that trigger only one modality [1].

MealMeter Macronutrient Estimation Protocol

The MealMeter system focuses on macronutrient composition estimation using physiological and motion sensing [12].

Device Specification: MealMeter leverages commercial wearable and mobile devices, incorporating continuous glucose monitoring, heart rate variability, inertial motion data, and environmental cues [12].

Study Protocol: Data was collected from 12 participants during labeled meal events. The system uses lightweight machine learning models trained on a diverse dataset to predict carbohydrates, proteins, and fats composition [12].

Fusion Methodology: The approach integrates physiological responses (glucose, HRV) with behavioral data (motion) and contextual cues to model relationships between meal intake and metabolic responses [12]. This multi-stream analysis enables more accurate macronutrient estimation compared to traditional approaches.

Compliance Detection Protocol

Accurate wear compliance measurement is essential for validating free-living study results [10].

Compliance Classification: A novel method was developed to classify four wear states: 'normal-wear' (device worn as prescribed), 'non-compliant-wear' (device worn improperly), 'non-wear-carried' (device carried on body but not worn), and 'non-wear-stationary' (device completely off-body) [10].

Detection Methodology: Features for compliance detection include standard deviation of acceleration, average pitch and roll angles, and mean square error of consecutive images. Random forest classifiers were trained using accelerometer data alone, images alone, and combined modalities [10]. The combined classifier achieved 89.24% accuracy in leave-one-subject-out cross-validation, demonstrating the advantage of multimodal assessment for determining actual device usage patterns [10].

The Multi-Modal Fusion Framework

The compositional approach to meal inference relies on strategically combining complementary sensing modalities to overcome limitations of individual sensors. The framework can be visualized as a multi-stage process that transforms raw sensor data into meal inferences.

Multi-modal sensor fusion follows three primary architectural patterns, each with distinct advantages for dietary monitoring applications:

Early Fusion: Raw data from multiple sensors is combined at the input level before feature extraction [11]. This approach preserves raw data relationships but requires careful handling of temporal alignment and modality-specific characteristics.

Intermediate Fusion: Features are extracted separately from each modality then combined before classification [11]. This balanced approach maintains modality-specific processing while enabling cross-modal correlation learning. The AIM-2 system employs this method through hierarchical classification that combines confidence scores from image and accelerometer classifiers [1].

Late Fusion: Each modality processes data independently through to decision-making, with final outputs combined at the decision level [11]. This approach provides maximum modality independence but may miss important cross-modal interactions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Modal Eating Detection Studies

| Resource / Tool | Function | Example Implementation | Considerations for Free-Living Deployment |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 Sensor System [1] [10] | Multi-modal data collection (images, acceleration, chewing) | Eyeglass-mounted device with camera, accelerometer, flex sensor | Privacy protection needed for continuous imaging; wear compliance monitoring essential |

| Wearable IMU Arrays [13] | Human activity recognition including eating gestures | Multiple body-worn IMUs (wrists, ankle, waist) | Optimal positioning minimizes burden while maintaining accuracy; 10Hz sampling may be sufficient |

| Ground Truth Annotation Tools [1] | Validation of automated detection | Foot pedal markers, manual image review, self-report apps | Multiple complementary methods improve reliability; resource-intensive for free-living studies |

| Compliance Detection Algorithms [10] | Quantifying actual device usage time | Random forest classifiers using acceleration and image features | Critical for interpreting free-living results; distinguishes non-wear from non-eating |

| Multimodal Fusion Frameworks [11] | Integrating diverse sensor data streams | Hierarchical classification, ensemble methods, intermediate fusion | Architecture choice balances performance with computational complexity |

| Privacy-Preserving Protocols [3] | Protecting participant confidentiality | Image filtering, selective capture, data anonymization | Essential for ethical free-living studies; may impact data completeness |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that multi-modal compositional approaches significantly outperform unimodal methods for eating detection in free-living environments [1] [3]. By combining complementary sensing modalities, these systems achieve enhanced robustness against the variability and unpredictability of real-world conditions.

The performance gap between laboratory and free-living environments remains substantial, underscoring the critical importance of validating dietary monitoring systems under realistic conditions [9]. Future research directions should prioritize improved wear compliance, enhanced privacy preservation, standardized evaluation metrics, and more sophisticated fusion architectures that can adapt to individual differences and contextual variations [10] [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate dietary monitoring methodologies requires careful consideration of the tradeoffs between accuracy, participant burden, privacy implications, and ecological validity. The compositional approach represents the most promising path forward for obtaining objective, reliable dietary data in the real-world contexts where health behaviors naturally occur.

The accurate detection of eating behavior is crucial for dietary monitoring in managing conditions like obesity and malnutrition. Wearable sensor technology has emerged as a powerful tool for objective, continuous monitoring of ingestive behavior in both controlled laboratory and free-living environments. The performance of these monitoring systems is fundamentally determined by the choice of sensor modality, each with distinct strengths and limitations in capturing eating proxies such as chewing, swallowing, and hand-to-mouth gestures.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of four key sensor modalities—acoustic, inertial, strain, and camera-based systems—framed within the context of in-lab versus free-living performance for wearable eating detection. By synthesizing experimental data and methodological insights from recent research, we aim to equip researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based criteria for sensor selection in dietary monitoring studies.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Sensor Modalities

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sensor Modalities for Eating Detection

| Sensor Modality | Primary Measured Parameter | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Precision | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic | Chewing and swallowing sounds [1] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Non-contact sensing; Rich temporal-frequency data [1] | Susceptible to ambient noise; Privacy concerns [1] |

| Inertial (Accelerometer) | Head movement, jaw motion [1] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported | Convenient (no direct skin contact needed) [1] | False positives from non-eating movements (9-30% range) [1] |

| Strain Sensor | Jaw movement, throat movement [1] | High for solid food intake [1] | High for solid food intake [1] | Direct capture of jaw movement [1] | Requires direct skin contact; Less convenient for users [1] |

| Camera-Based (Egocentric) | Visual identification of food [1] | 94.59% (when integrated with accelerometer) [1] | 70.47% (when integrated with accelerometer) [1] | Captures contextual food data; Passive operation [1] | Privacy concerns; False positives from non-consumed food (13%) [1] |

Table 2: In-Lab vs. Free-Living Performance Considerations

| Sensor Modality | Controlled Lab Environment | Free-Living Environment | Key Environmental Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic | High accuracy possible with minimal background noise [1] | Performance degradation in noisy environments [1] | Ambient speech, environmental noises [1] |

| Inertial (Accelerometer) | Reliable detection with controlled movements [1] | Increased false positives from unrestricted activities [1] | Natural movement variability, gait motions [1] |

| Strain Sensor | Excellent performance with proper skin contact [1] | Potential sensor displacement in daily activities [1] | Skin sweat, sensor adhesion issues [1] |

| Camera-Based (Egocentric) | Controlled food scenes reduce false positives [1] | Challenges with social eating, food preparation scenes [1] | Variable lighting, privacy constraints, image occlusion [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sensor Fusion for Eating Episode Detection

A hierarchical classification approach integrating inertial and camera-based sensors demonstrates significant performance improvements for free-living eating detection. The methodology from a study involving 30 participants wearing the Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2) device achieved 94.59% sensitivity and 70.47% precision when combining both modalities, outperforming either method alone by approximately 8% higher sensitivity [1].

Experimental Workflow:

Comparative Sensor Evaluation Framework

Rigorous comparative studies require standardized protocols to evaluate sensor performance. A framework used for comparing acoustic, optical, and pressure sensors for pulse wave analysis involved recording signals from 30 participants using all three sensors sequentially under controlled conditions (25±1°C room temperature after a 5-minute rest period) [14]. This approach enabled direct comparison of time-domain, frequency-domain, and pulse rate variability measures across modalities.

Key methodological considerations:

- Standardized positioning: Sensors placed at the same anatomical location (radial artery at wrist)

- Physiological stability: Measurements completed within 10 minutes per participant to minimize state variations

- Environmental controls: Quiet, temperature-controlled environment with participant instructions to abstain from caffeine, alcohol, and smoking for 24 hours prior [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Eating Detection Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 (Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2) | Integrated sensor system for eating detection | Camera (1 image/15 sec), 3D accelerometer (128 Hz), head motion capture [1] |

| Foot Pedal Logger | Ground truth annotation for lab studies | USB data logger for precise bite timing registration [1] |

| Reflective Markers | Motion tracking for inertial sensors | High-contrast markers for optical motion capture systems |

| Acoustic Metamaterials | Enhanced acoustic sensing | Adaptive metamaterial acoustic sensor (AMAS) with 15 dB gain, 10 kHz bandwidth [15] |

| Flexible Substrates | Wearable strain sensor integration | Conductive polymers, graphene, MXene for bendable, stretchable sensors [16] |

| Annotation Software | Ground truth labeling for image data | MATLAB Image Labeler application for bounding box annotation [1] |

Discussion and Research Implications

Performance Trade-offs Across Environments

The transition from controlled laboratory to free-living conditions presents significant challenges for all sensor modalities. While strain sensors demonstrate high accuracy for solid food intake detection in lab settings, they require direct skin contact, creating usability barriers in free-living scenarios [1]. Inertial sensors offer greater convenience but suffer from higher false positive rates (9-30%) due to confounding movements during unrestricted daily activities [1].

Camera-based systems provide valuable contextual food information but raise privacy concerns and generate false positives from food images not consumed by the user [1]. Acoustic sensors capture rich temporal-frequency data but are vulnerable to environmental noise contamination [1].

The Sensor Fusion Imperative

No single sensor modality optimally addresses all requirements for eating detection across laboratory and free-living environments. The demonstrated performance improvement through hierarchical classification of combined inertial and image data highlights the essential role of sensor fusion [1]. This approach achieves complementary benefits—inertial sensors detecting chewing events while cameras confirm food presence—effectively reducing false positives by leveraging the strengths of multiple sensing strategies.

Methodological Considerations for Future Research

Future research should prioritize multi-modal systems that dynamically adapt to environmental context. Standardized evaluation protocols across laboratory and free-living conditions will enable more meaningful cross-study comparisons. Additionally, addressing privacy concerns through on-device processing and developing robust algorithms resistant to environmental variabilities remain critical challenges. The integration of machine learning for adaptive signal processing shows particular promise for enhancing detection accuracy while managing computational demands [16] [17].

Selecting appropriate sensor modalities for eating detection requires careful consideration of the target environment and monitoring objectives. Controlled laboratory studies benefit from the high accuracy of strain sensors and detailed visual data from cameras, while free-living monitoring necessitates more robust modalities like inertial sensors with complementary modalities to mitigate false positives. The emerging paradigm of intelligent sensor fusion, leveraging the complementary strengths of multiple modalities, represents the most promising path forward for reliable dietary monitoring across diverse real-world contexts.

Automatically detecting eating episodes is a critical component for advancing care in conditions like diabetes, eating disorders, and obesity [18]. Unlike controlled laboratory settings, free-living environments introduce immense complexity due to varied eating gestures, diverse food types, numerous utensil interactions, and countless environmental contexts [19]. The core challenge lies in developing machine learning pipelines that can generalize from controlled data collection to real-world scenarios where motion artifacts, unpredictable activities, and diverse eating habits prevail. This comparison guide examines the complete technical pipeline—from raw sensor data acquisition to final eating event classification—evaluating the performance of different sensor modalities and algorithmic approaches across both in-lab and free-living conditions. Significant performance gaps exist between controlled and real-world environments; one study noted that image-based methods alone can generate up to 13% false positives in free-living conditions due to images of food not consumed by the user [1]. Understanding these pipelines is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals implementing digital biomarkers in clinical trials or therapeutic interventions.

The Machine Learning Pipeline: Core Components and Workflows

The transformation of raw sensor data into reliable eating event classification follows a structured pipeline, with key decision points at each stage that ultimately determine real-world applicability and accuracy.

Pipeline Architecture and Data Flow

The following diagram visualizes the complete end-to-end machine learning pipeline for eating event detection, integrating the key stages from data collection through model deployment:

Sensor Modalities and Data Acquisition Technologies

The initial pipeline stage involves selecting appropriate sensor technologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations for capturing eating behavior proxies. Research demonstrates that sensor choice fundamentally impacts performance across different environments.

Table 1: Sensor Modalities for Eating Detection

| Sensor Type | Measured Proxies | Common Placements | Laboratory Performance | Free-Living Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) [18] [3] | Hand-to-mouth gestures, arm movement | Wrist (smartwatch), neck | AUC: 0.82-0.95 [18] | AUC: 0.83-0.87 [18] | Confusion with similar gestures (e.g., face touching) |

| Acoustic Sensors [3] [20] | Chewing sounds, swallowing | Neck, throat, ears | F1-score: 87.9% [18] | F1-score: 77.5% [18] | Background noise interference, privacy concerns |

| Camera Systems [1] [19] | Food presence, eating environment | Eyeglasses, head-mounted | Accuracy: 86.4% [1] | Precision: 70.5% [1] | Privacy issues, false positives from non-consumed food |

| Strain/Pressure Sensors [3] [20] | Jaw movement, temporalis muscle activation | Head, jawline | Accuracy: >90% [3] | Limited free-living data | Skin contact required, uncomfortable for extended wear |

| Accelerometer-based Throat Sensors [20] | Swallowing, throat vibrations | Neck (suprasternal notch) | Accuracy: 95.96% [20] | Limited free-living data | Optimal placement critical, limited multi-event classification |

Experimental Protocols for Model Development and Validation

Robust eating detection requires carefully designed experimental protocols that account for both controlled validation and real-world performance assessment.

Laboratory Validation Protocols

Controlled laboratory studies follow structured protocols where participants consume predefined meals while researchers collect sensor data and precise ground truth. Typical protocols include:

- Structured Meal Consumption: Participants consume standardized meals using specific utensils (forks, knives, spoons, chopsticks, or hands) while wearing multiple sensors [18]. Meal sessions are typically video-recorded for precise ground truth annotation.

- Dosage-Response Studies: Researchers administer test foods in prespecified amounts to healthy participants to characterize pharmacokinetic parameters of candidate biomarkers and establish detection thresholds [21].

- Structured Activity Trials: Participants perform both eating and non-eating activities (e.g., talking, walking, reading) to evaluate classification specificity and identify confounding movements [22].

Free-Living Validation Protocols

Free-living protocols aim to assess system performance in natural environments with minimal intervention:

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Participants wear sensors for extended periods (days to weeks) during normal daily life while maintaining food diaries or using simplified logging methods (e.g., smartwatch button presses) [18].

- Passive Image Capture: Wearable cameras automatically capture images at regular intervals (e.g., every 15 seconds) during detected eating episodes for subsequent ground truth verification [1] [19].

- Multi-Environment Sampling: Data collection spans diverse eating environments (home, work, restaurants) to capture contextual variability [19]. One study documented that 55% of snacking occasions occurred with screens present, and 74.3% of dinners involved eating alone [19].

Performance Comparison: In-Lab versus Free-Living Environments

Significant performance differences emerge when eating detection systems transition from controlled laboratories to free-living environments, with sensor fusion and personalization strategies showing particular promise for bridging this gap.

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Environments

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Eating Detection Approaches

| Detection Method | Laboratory Performance (AUC/F1-Score) | Free-Living Performance (AUC/F1-Score) | Performance Gap | Key Factors Contributing to Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist IMU (Population Model) [18] | AUC: 0.825 (5-minute windows) | AUC: 0.825 (reported on validation cohort) | Minimal gap in AUC | Large training data (3828 hours), robust feature engineering |

| Wrist IMU (Personalized Model) [18] [23] | AUC: 0.872 | AUC: 0.87 (meal level) | -0.002 | Adaptation to individual eating gestures and patterns |

| Image-Based Detection [1] | F1-score: 86.4% | F1-score: 80.8% | -5.6% | Food images not consumed, environmental clutter |

| Sensor-Image Fusion [1] | Not reported | F1-score: 80.8%, Precision: 70.5%, Sensitivity: 94.6% | N/A | Complementary strengths reduce false positives |

| Acoustic (Swallowing Detection) [20] | Accuracy: 96.0% (throat sensor) | Limited data | Significant expected gap | Background noise, speaking interference |

The Algorithmic Workflow: From Raw Data to Classification

The core machine learning workflow involves multiple processing stages, each contributing to overall system performance:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Eating Detection Research

Implementing robust eating detection pipelines requires specific research tools and methodologies. The following table summarizes key solutions mentioned in the literature:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Eating Detection Studies

| Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Platforms | Apple Watch Series 4 [18], Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2) [1] [19] | Raw data acquisition (accelerometer, gyroscope, images) | AIM-2 captures images + sensor data simultaneously at 128Hz sampling |

| Annotation Tools | Food diaries [18], Foot pedals [1], Video recording [22] | Ground truth establishment for model training | Foot pedals provide precise bite timing; video enables retrospective validation |

| Data Processing Libraries | Linear Discriminant Analysis [19], CNN architectures [1] [20], LSTM networks [23] | Feature extraction and model implementation | Personalization with LSTM achieved F1-score of 0.99 in controlled settings [23] |

| Validation Methodologies | Leave-one-subject-out validation [1], Longitudinal follow-up [18], Independent seasonal cohorts [18] | Performance assessment and generalization testing | Seasonal validation cohorts confirmed model robustness (AUC: 0.941) [18] |

| Multi-modal Fusion Techniques | Hierarchical classification [1], Score-level fusion [1], Ensemble models [20] | Combining complementary sensor modalities | Fusion increased sensitivity by 8% over single modalities [1] |

The transition from controlled laboratory settings to free-living environments remains the most significant challenge in wearable eating detection. While laboratory studies frequently report impressive metrics (AUC >0.95, accuracy >96%), these results typically decline in free-living conditions due to environmental variability, confounding activities, and diverse eating behaviors [18] [20]. The most promising approaches for bridging this gap include multi-modal sensor fusion, which reduces false positives by combining complementary data sources [1], and personalized model adaptation, which fine-tunes algorithms to individual eating gestures and patterns [18] [23]. For researchers and drug development professionals implementing these systems, the evidence suggests that wrist-worn IMU sensors with personalized deep learning models currently offer the best balance of performance, usability, and privacy for free-living eating detection, particularly when validated across diverse seasonal cohorts and eating environments. Continued advances in sensor technology, ensemble learning methods, and large-scale validation studies will be crucial for further narrowing the performance gap between laboratory development and real-world deployment.

The accurate detection of eating episodes is fundamental to advancing nutritional science, managing chronic diseases, and developing effective dietary interventions. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, evaluating the performance of detection technologies is paramount. This assessment relies on a core set of metrics—Accuracy, F1-Score, Precision, and Recall—which provide a quantitative framework for comparing diverse methodologies [24]. These metrics take on additional significance when considered within the critical framework of in-lab versus free-living performance. A method that excels in the controlled conditions of a laboratory may suffer from degraded performance when deployed in the complex, unpredictable environment of daily life, making the understanding and reporting of these metrics essential for technological selection and development [4] [18]. This guide provides a structured comparison of eating detection technologies, detailing their experimental protocols and performance data to inform research decisions.

Core Performance Metrics Explained

The following table defines the key metrics used to evaluate eating detection systems.

Table 1: Definition of Key Performance Metrics in Eating Detection

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in Eating Detection Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The proportion of total predictions (both eating and non-eating) that were correct. | Overall, how often is the system correct? Can be misleading if the dataset is imbalanced (e.g., long periods of non-eating). |

| Precision | The proportion of predicted eating episodes that were actual eating episodes. | When the system detects an eating episode, how likely is it to be correct? A measure of false positives. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | The proportion of actual eating episodes that were correctly detected. | What percentage of all real meals did the system successfully find? A measure of false negatives. |

| F1-Score | The harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. | A single metric that balances the trade-off between Precision and Recall. Useful for class imbalance. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | The probability that the model will rank a random positive instance more highly than a random negative one. | Overall measure of the model's ability to distinguish between eating and non-eating events across all thresholds. |

Technology Comparison: Performance Data and Methodologies

Eating detection technologies can be broadly categorized by their sensing modality and deployment setting. The table below synthesizes performance data from key studies, highlighting the direct impact of the research environment on model efficacy.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Eating Detection Technologies Across Environments

| Technology & Study | Detection Target | Study Environment | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Strengths & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist Motion (Apple Watch) [18] | Eating episodes via hand-to-mouth gestures | Free-living | AUC: 0.825 (general model), AUC: 0.872 (personalized), AUC: 0.951 (meal-level) | Strengths: High meal-level accuracy; uses consumer-grade device. Limitations: Performance improves with personalized data. |

| Integrated Image & Sensor (AIM-2) [1] | Eating episodes via camera and accelerometer (chewing) | Free-living | Sensitivity (Recall): 94.59%, Precision: 70.47%, F1-Score: 80.77% | Strengths: Sensor-image fusion reduces false positives. Limitations: Privacy concerns with egocentric camera. |

| Video-Based (ByteTrack) [8] | Bite count and bite rate from meal videos | Laboratory | Precision: 79.4%, Recall: 67.9%, F1-Score: 70.6% | Strengths: Scalable vs. manual coding. Limitations: Performance drops with occlusion/motion. |

| Acoustic & Motion Sensors [4] [3] | Chewing, swallowing, hand-to-mouth gestures | Laboratory & Free-living | Varies by sensor and algorithm (F1-scores from ~70% to over 90% reported in literature) | Strengths: Direct capture of eating-related signals. Limitations: Sensitive to environmental noise; can be intrusive. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The performance data in Table 2 is derived from rigorous, though distinct, experimental methodologies.

- Wrist Motion Sensing (Free-Living Study) [18]: This study utilized a prospective, longitudinal design. Participants wore Apple Watches programmed with a custom app to stream accelerometer and gyroscope data. Ground truth was established via a diary function on the watch for logging eating events. The deep learning model was trained on 3,828 hours of free-living data. The high AUC at the meal level (0.951) was achieved by aggregating predictions over 5-minute windows to identify the entire meal event, demonstrating a robust method for handling real-world variability.

- Integrated Image and Sensor System (AIM-2) [1]: This research used the Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2), a wearable device on eyeglass frames containing a camera and a 3D accelerometer. Data was collected over two days: a pseudo-free-living day (meals in lab, other activities unrestricted) and a true free-living day. The ground truth for sensor data used a foot pedal pressed by participants during bites and swallows. For image-based detection, over 90,000 egocentric images were manually annotated with bounding boxes for food/beverage objects. A hierarchical classifier fused the confidence scores from the image and sensor (chewing) models to make the final eating episode detection, which directly led to the improved F1-score by reducing false positives.

- Video-Based Bite Detection (ByteTrack) [8]: This pilot study was conducted in a controlled laboratory setting. Meals from 94 children were video-recorded at 30 frames per second. The ground truth was established by manual observational coding of bite timestamps. The ByteTrack model is a two-stage deep learning pipeline: first, it detects and tracks faces in the video using a hybrid of Faster R-CNN and YOLOv7; second, it classifies bites using an EfficientNet CNN combined with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to analyze temporal sequences. The model was trained and tested on a dataset of 242 lab-meal videos.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential tools and algorithms used in the development and validation of automated eating detection systems.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Eating Detection Research

| Tool / Algorithm Name | Type | Primary Function in Eating Detection |

|---|---|---|

| AIM-2 (Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2) [1] | Wearable Sensor Hardware | A multi-sensor device (camera, accelerometer) worn on glasses for simultaneous image and motion data capture in free-living. |

| ByteTrack Pipeline [8] | Deep Learning Model | A two-stage system for automated bite detection from video, integrating face detection (Faster R-CNN/YOLOv7) and bite classification (EfficientNet + LSTM). |

| YOLO (You Only Look Once) variants [25] | Object Detection Algorithm | A family of fast, efficient deep learning models (e.g., YOLOv8) used for real-time food item identification and portion estimation from images. |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN/LSTM) [18] [26] | Deep Learning Architecture | A type of neural network designed for sequential data, used to model the temporal patterns of motion sensor data or video frames for event detection. |

| Universal Eating Monitor (UEM) [27] | Laboratory Apparatus | A standardized lab tool using a concealed scale to measure cumulative food intake and eating rate with high precision, serving as a validation benchmark. |

| Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) Validation [1] | Statistical Method | A rigorous cross-validation technique where data from one participant is held out for testing, ensuring generalizable performance across individuals. |

Analysis of Performance in In-Lab vs. Free-Living Contexts

A central challenge in this field is the performance gap between controlled laboratory settings and free-living environments [4] [24]. Laboratory studies, like the ByteTrack research, benefit from standardized lighting, minimal occlusions, and precise ground truthing (e.g., manual video coding), allowing for cleaner data and often higher performance on specific metrics like precision [8]. In contrast, free-living studies must contend with unpredictable environments, diverse eating styles, and less controlled ground truth (e.g., self-reported diaries), which can introduce noise and increase both false positives and false negatives [18].

The data shows that multi-modal approaches are a promising strategy for bridging this gap. For instance, the AIM-2 system demonstrated that combining a sensor modality (accelerometer for chewing) with an image modality (camera for food presence) created a more robust system. The sensor data helped detect the event, while the image data helped confirm it, thereby increasing sensitivity (recall) while maintaining precision [1]. Furthermore, personalized models, as seen in the wrist-worn sensor study, which fine-tune algorithms to an individual's unique patterns, can significantly boost performance metrics like AUC in free-living conditions [18].

Selecting and developing eating detection technology requires careful consideration of its application context. For closed-loop medical systems like automated insulin delivery, where a false positive could have immediate consequences, high Precision is paramount [26]. Conversely, for nutritional epidemiology studies aiming to understand total dietary patterns, high Recall (Sensitivity) to capture all eating events may be more critical [4]. The evidence indicates that no single metric is sufficient; a holistic view of Accuracy, F1-Score, Precision, and Recall is essential. Future progress hinges on the development of robust, multi-modal systems and sophisticated algorithms that are validated in large-scale, real-world studies, moving beyond laboratory benchmarks to deliver reliable performance in the complexity of everyday life.

Methodologies in Action: Sensor Systems, Algorithms, and Real-World Deployment

The accurate monitoring of dietary intake is a critical challenge in nutritional science, chronic disease management, and public health research. Traditional methods, such as food diaries and 24-hour recalls, are plagued by inaccuracies due to participant burden, recall bias, and misreporting [4] [3]. Wearable sensor technology presents a promising alternative, offering the potential for objective, real-time data collection in both controlled laboratory and free-living environments [2] [4]. The performance and applicability of these systems, however, vary significantly based on their design, sensor modality, and placement on the body.

This guide provides a structured comparison of three predominant wearable form factors—neck-worn, wrist-worn (smartwatches), and eyeglass-based sensors—framed within the critical research context of in-laboratory versus free-living performance. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these distinctions is essential for selecting appropriate technologies for clinical trials, nutritional epidemiology, and behavioral intervention studies.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables synthesize key performance metrics and characteristics of the three wearable system types, drawing from recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Wearable Eating Detection Systems

| Form Factor | Primary Sensing Modality | Target Behavior | Reported Performance (In-Lab) | Reported Performance (Free-Living) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck-worn | Piezoelectric sensor, Accelerometer [2] | Swallowing | F1-score: 86.4% - 87.0% (swallow detection) [2] | 77.1% F1-score (eating episode) [2] |

| Eyeglass-based | Optical Tracking (OCO) Sensors, Accelerometer [28] [1] | Chewing, Facial Muscle Activation | F1-score: 0.91 (chewing detection) [28] | Precision: 0.95, Recall: 0.82 (eating segments) [28] |

| Wrist-worn | Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) [29] [23] | Hand-to-Mouth Gestures | Median F1-score: 0.99 (personalized model) [23] | Episode True Positive Rate: 89% [29] |

Table 2: System Characteristics and Applicability

| Form Factor | Strengths | Limitations | Best-Suited Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck-worn | Direct capture of swallowing; high accuracy for ingestion confirmation [2] | Can be obtrusive; sensitive to body shape and variability [2] | Detailed studies of ingestion timing and frequency in controlled settings |

| Eyeglass-based | High granularity for chewing analysis; robust performance in real-life [28] | Requires consistent wearing of glasses; potential privacy concerns with cameras [1] | Investigations linking micro-level eating behaviors (chewing rate) to health outcomes |

| Wrist-worn | High user compliance; leverages commercial devices (smartwatches); suitable for long-term monitoring [29] [30] | Prone to false positives from non-eating gestures [29] | Large-scale, long-term studies in free-living conditions focusing on meal patterns |

Detailed Methodologies of Key Experiments

Neck-worn System: Multi-Sensor Swallow Detection

Experimental Protocol: A series of studies developed a neck-worn eating detection system using piezoelectric sensors embedded in a necklace to capture throat vibrations and an accelerometer to track head movement [2]. The primary target behavior was swallowing. The methodology involved:

- Data Collection: Studies were conducted with 130 participants across both laboratory and free-living settings. In-lab studies provided controlled ground truth, while free-living studies used wearable cameras for ground truth annotation [2].

- Ground Truth: In the lab, a mobile application was used for annotation. In free-living conditions, a wearable camera captured egocentric images for manual review to mark eating episodes [2].

- Analysis: Classification algorithms were trained on the sensor data streams to detect swallows of solids and liquids. The system employed a compositional approach, where the detection of multiple components (bites, chews, swallows, gestures) in temporal proximity increased the robustness of eating episode identification [2].

Key Findings: The system demonstrated high performance in laboratory conditions (F1-score up to 87.0% for swallow detection) but experienced a performance drop in free-living settings (77.1% F1-score for eating episodes), highlighting the challenges of real-world deployment [2].

Eyeglass-based System: Optical Chewing Detection with Deep Learning

Experimental Protocol: This study utilized smart glasses equipped with OCO (optical) sensors to monitor skin movement over facial muscles activated during chewing, such as the temporalis (temple) and zygomaticus (cheek) muscles [28].

- Data Collection: Two datasets were collected: one in a controlled laboratory environment and another in real-life ("in-the-wild") conditions. The OCO sensors measured 2D relative movements on the skin's surface [28].

- Model Training: A Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM) deep learning model was trained to distinguish chewing from other facial activities like speaking and teeth clenching. A hidden Markov model was integrated to handle temporal dependencies between chewing events in real-life data [28].

- Performance Evaluation: The model was evaluated using leave-one-subject-out cross-validation to ensure generalizability to unseen users [28].

Key Findings: The system maintained high performance across settings, achieving an F1-score of 0.91 in the lab and a precision of 0.95 with a recall of 0.82 for eating segments in real-life, demonstrating its resilience outside the laboratory [28].

Wrist-worn System: Daily-Pattern Gesture Analysis

Experimental Protocol: This research addressed the limitations of detecting brief, individual hand-to-mouth gestures by analyzing a full day of wrist motion data as a single sample [29].

- Data and Sensors: The study used the publicly available Clemson All-Day (CAD) dataset, containing data from wrist-worn IMUs (accelerometer and gyroscope) [29].

- Two-Stage Framework:

- Stage 1 (Sliding Window Classifier): A model analyzed short windows of data (seconds to minutes) to calculate a local probability of eating,

P(Ew) - Stage 2 (Daily Pattern Classifier): A second model analyzed the entire day-long sequence of

P(Ew)to output an enhanced probability,P(Ed), leveraging diurnal context to reduce false positives [29].

- Stage 1 (Sliding Window Classifier): A model analyzed short windows of data (seconds to minutes) to calculate a local probability of eating,

- Data Augmentation: A novel augmentation technique involving iterative retraining of the Stage 1 model was used to generate sufficient day-length samples for training the Stage 2 model [29].

Key Findings: The daily-pattern approach substantially improved accuracy over local-window analysis alone, achieving an eating episode true positive rate of 89% in free-living, demonstrating the value of contextual, long-term analysis [29].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core sensing principles and experimental workflows for the featured eyeglass-based and wrist-worn systems.

Eyeglass-based Optical Sensing Principle

Diagram 1: Optical Chewing Detection Workflow. This sequence shows how eyeglass-based systems convert facial movement into chewing detection [28].

Wrist-worn Two-Stage Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Two-Stage Worn Data Analysis. This workflow outlines the process of using local and daily context to improve eating episode detection from wrist motion [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing studies in wearable dietary monitoring, the following tools and components are essential.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Wearable Eating Detection Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example Form Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Tracks motion for gesture (wrist) and jaw movement (head/ear) detection [29] [31]. | Wrist-worn, Eyeglass-based, Ear-worn |

| Piezoelectric Sensor | Detects vibrations from swallowing and chewing [2]. | Neck-worn |

| Optical Tracking Sensor (OCO) | Moners skin surface movement from underlying muscle activity [28]. | Eyeglass-based |

| Wearable Egocentric Camera | Provides ground truth data by passively capturing images from the user's perspective [2] [1]. | Eyeglass-based (e.g., AIM-2 sensor) |

| Bio-impedance Sensor | Measures electrical impedance changes caused by body-food-utensil interactions during dining [6]. | Wrist-worn (e.g., iEat device) |

| Public Datasets (e.g., CAD, OREBA) | Benchmarks and trains new algorithms using large, annotated real-world data [29] [30]. | N/A |

The choice between neck-worn, wrist-worn, and eyeglass-based sensors for eating detection involves a direct trade-off between specificity, granularity, and practicality. Neck-worn systems offer high physiological specificity for ingestion acts, eyeglass-based systems provide unparalleled granularity for chewing microstructure, and wrist-worn systems offer the highest potential for scalable, long-term adherence.

A critical insight for researchers is the almost universal performance gap between in-lab and free-living results, underscoring the necessity of validating technologies in real-world settings. The future of the field points toward multi-modal sensor fusion—such as combining wrist-worn IMU data with egocentric images—to leverage the strengths of each form factor and mitigate their individual weaknesses, ultimately providing a more comprehensive and accurate picture of dietary behavior for clinical and research applications [1].

The validation of wearable sensors for automatic eating detection relies fundamentally on the establishment of high-fidelity ground truth data collected under controlled laboratory conditions. In-field testing, while ecologically valid, introduces numerous confounding variables and behavioral modifications that complicate the initial development and calibration of detection algorithms [32]. In-lab protocols provide the methodological foundation for generating the annotated datasets necessary to train and validate machine learning models by creating environments where eating activities can be precisely measured, timed, and recorded [33]. This controlled approach enables researchers to establish causal relationships between sensor signals and specific ingestive behaviors—such as chewing, swallowing, and biting—with a level of precision unattainable in free-living settings [3].

The term "ground truth" originates from meteorological science, referring to data collected on-site to confirm remote sensor measurements [33]. In machine learning for dietary monitoring, ground truth data comprises the accurately labeled reality against which sensor-based algorithms are calibrated and evaluated [33] [34]. For eating behavior research, this typically involves precise annotation of eating episode start and end times, individual bites, chewing sequences, and food types. The quality of this ground truth directly determines the performance ceiling of any subsequent eating detection system, as models cannot learn to recognize patterns more accurately than the reference data against which they are trained [33].

In-Lab Ground Truth Annotation Methodologies

Foot Pedal Annotation Systems

Foot pedals represent one of the most precise methods for real-time annotation of ingestive events in laboratory settings. This approach allows participants to maintain natural hand movements during eating while providing a mechanism for precise temporal marking of intake events. The methodology typically involves connecting a USB foot pedal to a data logging system that timestamps each activation with millisecond precision.

In a seminal study utilizing this approach, participants were instructed to press and hold a foot pedal from the moment food was placed in the mouth until the final swallow was completed [1]. This continuous press-and-hold protocol captures both the discrete bite event and the entire ingestion sequence for each bite, providing comprehensive temporal data on eating microstructure. The resulting data stream creates a high-resolution timeline of eating events that can be synchronized with parallel sensor data streams from wearable devices [1]. The primary advantage of this system is its ability to capture the exact duration of each eating sequence without requiring researchers to manually annotate video recordings post-hoc, which introduces human reaction time delays and potential errors.

Table: Foot Pedal Protocol Specifications from AIM-2 Research

| Parameter | Specification | Application in Eating Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Method | Press and hold | Marks entire ingestion sequence from food entry to final swallow |

| Data Output | Timestamped digital signal | Synchronized with wearable sensor data streams |

| Temporal Precision | Millisecond accuracy | Enables precise eating microstructure analysis |

| User Interface | USB foot pedal | Hands-free operation during eating |

| Data Integration | Synchronized with sensor data | Serves as reference for chewing detection algorithms |

Supplementary Annotation Methods

While foot pedals provide excellent temporal precision, comprehensive in-lab protocols often employ multi-modal validation strategies that combine several annotation methodologies to cross-validate ground truth data.

Video Recording with Timestamp Synchronization: High-definition video recording serves as a fundamental validation tool in laboratory eating studies [3]. Cameras are strategically positioned to capture detailed views of the participant's mouth, hands, and food items. These recordings are subsequently manually annotated by trained raters to identify and timestamp specific eating-related events, including bite acquisition, food placement in the mouth, chewing sequences, and swallows [3]. The inter-rater reliability is typically established through consensus coding and statistical measures of agreement.

Self-Report Push Buttons: Some wearable systems, such as the Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM), incorporate hand-operated push buttons that allow participants to self-report eating initiation and cessation [35]. While this approach introduces potential confounding factors through required hand movement, it provides a valuable secondary validation source when used in conjunction with other methods.

Researcher-Annotated Food Journals: Participants may complete detailed food journals with researcher guidance, documenting precise start and end times of eating episodes, along with food types and quantities consumed [35]. These journals are particularly valuable for contextualizing sensor data and resolving ambiguities in other annotation streams during subsequent data analysis phases.

Experimental Protocols for Controlled Data Collection

Laboratory Setup and Protocol Design

Implementing robust in-lab protocols requires meticulous attention to experimental design to balance ecological validity with measurement precision. A typical laboratory setup for eating behavior research includes a controlled environment that minimizes external distractions while replicating natural eating conditions as closely as possible.

The laboratory protocol from the AIM-2 validation studies exemplifies this approach [1]. Participants were recruited for pseudo-free-living days where they consumed three prescribed meals in a laboratory setting while engaging in otherwise unrestricted activities. During these sessions, participants wore the AIM-2 device, which incorporated a head-mounted camera capturing egocentric images every 15 seconds and a 3-axis accelerometer sampling at 128 Hz to detect chewing motions [1]. The simultaneous collection of foot pedal data, sensor signals, and video recordings created a multi-modal dataset with precisely synchronized ground truth annotations.

The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

- Sensor Calibration: Devices were calibrated and properly positioned on participants by research staff at the beginning of each session.

- Standardized Meal Presentation: Meals were provided with careful documentation of food types and portions, though participants were allowed to eat naturally without specific instructions on eating rate or bite size.

- Continuous Monitoring: Researchers monitored data collection in real-time to ensure proper operation of all recording systems throughout the eating episodes.

- Data Synchronization: All data streams were synchronized using precise timestamps to enable cross-referencing during analysis.

Table: Comparison of Ground Truth Annotation Methods

| Method | Temporal Precision | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foot Pedal | Millisecond | Hands-free operation; captures entire ingestion sequence | Learning curve for participants; may alter natural eating rhythm | Detailed microstructure analysis; bite-level validation |

| Video Annotation | Sub-second | Comprehensive behavioral context; no participant burden | Labor-intensive analysis; privacy concerns | Validation of other methods; complex behavior coding |

| Push Button | Second | Simple implementation; direct participant input | Interrupts natural hand movements; potential for missed events | Meal-level event marking; secondary validation |

| Food Journal | Minute | Contextual food information; low technical requirements | Dependent on participant memory and compliance | Supplementing temporal data; food type identification |

Data Integration and Algorithm Validation

The integration of multiple ground truth sources enables rigorous validation of sensor-based eating detection algorithms. The foot pedal data, with its high temporal precision, serves as the primary timing reference for evaluating the performance of accelerometer-based chewing detection and image-based food recognition algorithms [1].

In the validation pipeline, the timestamps from foot pedal activations are used to segment sensor data into eating and non-eating periods. Machine learning classifiers—including artificial neural networks and hierarchical classification systems—are then trained to recognize patterns in the sensor data that correspond to these annotated periods [1] [35]. The performance of these classifiers is quantified using standard metrics including accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1-score, with the foot pedal annotations providing the definitive reference for calculating these metrics [32].

This approach was successfully implemented in the development of the Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM), which integrated jaw motion sensors, hand gesture sensors, and accelerometers [35]. The system achieved 89.8% accuracy in detecting food intake in free-living conditions by leveraging ground truth data collected initially under controlled laboratory conditions [35]. This demonstrates the critical role of precise in-lab annotation in developing robust detection algorithms that subsequently perform well in more variable free-living environments.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for In-Lab Eating Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Wearable Sensor Platform | Capture physiological and motion data during eating | AIM-2 with camera (15s interval) & accelerometer (128Hz) [1] |

| Foot Pedal System | Precise temporal annotation of ingestion events | USB data logger with millisecond timestamping [1] |

| Video Recording Setup | Comprehensive behavioral context and validation | HD cameras with multiple angles and synchronized timestamps |

| Data Synchronization Software | Alignment of multiple data streams for analysis | Custom software for temporal alignment of sensor, pedal, and video data |

| Annotation Tools | Manual labeling and validation of eating events | MATLAB Image Labeler or similar video annotation platforms [1] |

Visualizing In-Lab Ground Truth Collection Workflows

In-Lab Ground Truth Collection Workflow

The diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for collecting ground truth data in laboratory settings. The process begins with participant preparation and sensor calibration, ensuring proper device positioning and operation [1] [35]. During the controlled data collection phase, multiple parallel data streams are captured simultaneously: foot pedal activations marking precise ingestion events, wearable sensors capturing physiological and motion data, and video recordings providing comprehensive behavioral context [1]. These streams are then temporally synchronized using precise timestamps to create an integrated ground truth dataset that serves as the reference standard for algorithm development and validation [1] [35]. This multi-modal approach leverages the respective strengths of each annotation method while mitigating their individual limitations.

Comparative Performance of Annotation Methods

The selection of ground truth annotation methods involves important trade-offs between temporal precision, participant burden, and analytical complexity. Foot pedal systems provide excellent temporal resolution for capturing eating microstructure but require participant training and may subtly influence natural eating rhythms [1]. Video-based annotation offers rich contextual information but introduces significant post-processing overhead and raises privacy considerations [3].

Research indicates that integrated approaches leveraging multiple complementary methods yield the most robust ground truth datasets. In validation studies, systems combining foot pedal annotations with sensor data and video recording have achieved detection accuracies exceeding 89% for eating episodes [35]. More recently, hierarchical classification methods that integrate both sensor-based and image-based detection have demonstrated further improvements, achieving 94.59% sensitivity and 80.77% F1-score in free-living validation [1]. These results underscore the critical importance of high-quality in-lab ground truth data for developing effective eating detection algorithms that maintain performance when deployed in real-world settings.

The methodological rigor established through controlled in-lab protocols directly enables the subsequent validation of wearable systems in free-living environments. By providing definitive reference measurements, these protocols create the foundation for objective comparisons between different sensing technologies and algorithmic approaches, ultimately driving innovation in the field of automated dietary monitoring [32] [3].

The transition from controlled laboratory settings to unrestricted, free-living environments represents a critical frontier in wearable eating detection research. While laboratory studies provide valuable initial validation, they often fail to capture the complex, unstructured nature of real-world eating behavior, leading to what researchers term the "lab-to-life gap." [32] Free-living deployment is crucial because it is where humans behave naturally, and many influences on eating behavior cannot be replicated in a laboratory. [32] Furthermore, non-eating behaviors that confound sensors (e.g., smoking, nail-biting) are too numerous and not all known to replicate naturally in controlled settings. [32]

This guide objectively compares the performance of various wearable sensing technologies and deployment strategies for detecting eating behavior in free-living conditions, synthesizing experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The ability to explore micro-level eating activities, such as meal microstructure (the dynamic process of eating, including meal duration, changes in eating rate, chewing frequency), is important because recent literature suggests they may play a significant role in food selection, dietary intake, and ultimately, obesity and disease risk. [32]

Performance Comparison of Free-Living Eating Detection Technologies

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of various wearable sensor systems validated in free-living conditions, highlighting the diversity of approaches and their respective effectiveness.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Eating Detection Technologies in Free-Living Conditions

| Device/Sensor System | Sensor Placement | Primary Detection Method | Key Performance Metrics | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple Watch (Deep Learning Model) [18] | Wrist | Accelerometer & gyroscope (hand-to-mouth gestures) | Meal-level AUC: 0.951; Validation cohort AUC: 0.941 [18] | 3828 hours of data; 34 participants; free-living [18] |

| AIM-2 (Integrated Image & Sensor) [1] | Eyeglasses | Camera + accelerometer (chewing) | 94.59% Sensitivity, 70.47% Precision, 80.77% F1-score [1] | 30 participants; 2-day free-living validation [1] |

| Multi-Sensor System (HabitSense) [5] | Necklace (NeckSense), Wristband, Bodycam | Multi-sensor fusion (chewing, bites, hand movements, images) | Identified 5 distinct overeating patterns (e.g., late-night snacking, stress eating) [5] | 60 adults with obesity; 2-week free-living study [5] |

| Neck-Worn Sensor [32] | Neck | Chewing and swallowing detection | F1-score: 81.6% (from reviewed literature) [32] | Literature review of 40 in-field studies [32] |

| Ear-Worn Sensor [32] | Ear | Chewing detection | F1-score: 77.5%; Weighted Accuracy: 92.8% (from reviewed literature) [32] | Literature review of 40 in-field studies [32] |

Key Insights from Performance Data

- Wrist-worn sensors show high meal-level detection accuracy (AUC >0.94) using deep learning models on commercial devices, favoring scalability and user compliance. [18]