From the Ground Up: Optimizing Soil Health for Nutrient-Dense Crops and Biomedical Potential

This article synthesizes current research on the critical link between agricultural soil management and the nutritional quality of food crops, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical and clinical...

From the Ground Up: Optimizing Soil Health for Nutrient-Dense Crops and Biomedical Potential

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the critical link between agricultural soil management and the nutritional quality of food crops, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical and clinical research. It explores the foundational science of how soil properties influence the density of essential vitamins, minerals, and bioactive phytochemicals. The content details practical soil health management systems, addresses challenges in implementation and optimization, and validates approaches through economic case studies and emerging scientific trends. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review highlights the potential of soil management as a foundational strategy for enhancing the raw materials used in nutritional science and preventative health research.

The Soil-Food-Health Nexus: How Soil Biology and Chemistry Dictate Crop Nutrient Density

Soil health, defined as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living system that sustains biological productivity and supports plant health, is increasingly recognized as a fundamental factor influencing the nutritional quality of crops [1] [2]. Within the broader thesis of soil health management for enhanced crop nutrition, this review examines the mechanistic links between soil properties, nutrient bioavailability, and plant biosynthetic pathways. A growing body of evidence suggests that farming practices which rebuild soil organic matter and enhance soil biological activity can significantly increase the density of vitamins, minerals, and beneficial phytochemicals in crops [2]. This relationship extends beyond conventional nutrient management to encompass the complex interactions between soil physical structure, microbial communities, and root system functionality that collectively govern a plant's access to resources and its subsequent metabolic investments in defense-related compounds. By integrating insights from recent field studies and mechanistic research, this technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand and leverage the soil-plant nexus for enhanced crop nutritional quality.

Key Soil Health Parameters and Their Plant Physiological Impacts

The relationship between soil health and plant nutrient uptake operates through interconnected physical, chemical, and biological pathways. Understanding these parameters provides the foundation for targeted soil management strategies to enhance crop nutritional quality.

Table 1: Essential Soil Health Parameters and Their Mechanisms of Influence on Plant Nutrition

| Parameter | Measurement Methods | Direct Physiological Impact on Plants | Influence on Nutrient Biosynthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Organic Matter | Loss on ignition; Wet combustion [2] | Increases cation exchange capacity, water retention; enhances root development | Provides carbon skeletons for secondary metabolite production |

| Microbial Activity & Diversity | Haney test (CO₂ respiration, water-extractable organic C/N) [2]; Molecular diagnostics [1] | Enhances mineralization of organically-bound nutrients; produces plant growth promoters | Induces defense-related phytochemical synthesis through microbial signaling |

| Soil Structure & Aggregate Stability | Wet-sieving; Visual evaluation of soil structure [3] | Improves soil aeration and root penetration; reduces soil strength impedance | Affects carbon allocation patterns between root exudates and shoot metabolites |

| Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) | Ammonium acetate extraction; ICP-OES [4] | Determines nutrient retention and buffering capacity; reduces leaching losses | Influences mineral micronutrient availability for enzyme cofactors in biosynthesis pathways |

The integration of these parameters creates a soil health continuum that directly influences plant physiological processes. Research across paired farming systems has demonstrated that soils with enhanced health profiles—characterized by 3-12% soil organic matter (versus 2-5% in conventional soils) and Haney soil health scores of 11-30 (versus 3-14 in conventional soils)—consistently produce crops with significantly higher levels of certain vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals [2]. The underlying mechanisms involve both improved nutrient availability and plant physiological responses to soil biological communities, particularly the complex signaling between roots and soil microbiota that triggers production of defense-related compounds with human health benefits [1] [2].

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Assessments of the Soil Health-Nutrient Density Link

Recent field studies provide compelling quantitative evidence for the connection between soil management practices, soil health indicators, and enhanced nutrient density in crops.

Paired Farm System Comparisons

A systematic comparison of regenerative and conventional farming practices across eight paired farms in the United States revealed significant differences in both soil health metrics and crop nutritional profiles [2]. Regenerative practices, which combined no-till, cover crops, and diverse rotations, resulted in substantially improved soil health scores and crop nutrient density.

Table 2: Soil Health and Crop Nutrient Density in Paired Farming Systems [2]

| Farm Pair Location | Soil Organic Matter (%) | Haney Soil Health Score | Crop Analyzed | Key Nutritional Differences (Regenerative vs Conventional) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina | 6.2 vs 3.1 | 24 vs 11 | Corn | Higher vitamin E, K, and B vitamins; Increased magnesium, calcium |

| Iowa | 5.8 vs 3.4 | 18 vs 7 | Soybeans | Elevated total phenols and phytosterols; Higher manganese, zinc |

| Kansas | 6.9 vs 4.2 | 22 vs 9 | Sorghum | Enhanced carotenoid content; Improved phosphorus, iron levels |

| Montana | 5.5 vs 2.8 | 17 vs 6 | Peas | Increased vitamin C; Higher copper, potassium bioavailability |

| California | 6.1 vs 3.3 | 19 vs 8 | Cabbage | Superior phytochemical profile; Enhanced mineral micronutrients |

Biochar and Compost Amendment Studies

Field trials conducted at two urban farms in Sacramento, California, demonstrated the efficacy of specific soil amendments in enhancing both soil health parameters and crop nutrient content [4]. The study employed a randomized complete block design with four treatments (control, compost, biochar, and compost-biochar mix) to evaluate effects on soil properties and corn kernel nutrient composition.

Table 3: Soil Amendments and Crop Nutrient Enhancement in Sacramento Urban Agriculture Trial [4]

| Treatment | Application Rate | Key Soil Health Improvements | Corn Kernel Nutrient Enhancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | No amendment | Baseline properties | Reference nutrient levels |

| Compost | 25 t ha⁻¹ (10 Mg C ha⁻¹) | Increased microbial activity; Moderate SOM improvement | Moderate increases in nitrogen-based compounds |

| Biochar | 12.5 t ha⁻¹ (10 Mg C ha⁻¹) | +22% water holding capacity; +18% CEC; +15% SOM | Significant increases in P, Mg, Ca, Fe (p<0.05) |

| Compost-Biochar Mix | 20 Mg C ha⁻¹ combined | Enhanced microbial metabolic activity; Improved community evenness; Optimal soil structure | Greatest increases in P, Mg, Ca, Fe; Enhanced phytochemical diversity |

The synergistic effect of combined compost and biochar amendments was particularly notable, creating a soil environment that supported both enhanced nutrient availability and improved plant nutrient uptake and utilization [4]. This suggests that integrated amendment strategies may offer the most promising approach for manipulating soil health to target specific nutritional outcomes in crops.

Methodological Toolkit: Experimental Protocols for Soil Health-Nutrient Uptake Research

Standardized Soil Health Assessment Protocol

Comprehensive soil health assessment requires an integrated approach that captures biological, chemical, and physical properties. The following protocol synthesizes methodologies from recent studies [4] [2]:

Soil Sampling: Collect composite topsoil samples (0-15 cm depth) from multiple locations within experimental plots using a standardized soil corer. Samples should be collected during consistent seasonal periods, preferably prior to planting and after harvest.

Biological Analysis:

- Microbial Respiration: Utilize the Haney test method [2] by incubating 40g of soil at 24°C for 24 hours and measuring CO₂ evolution via infrared gas analysis.

- Microbial Biomass: Determine water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) and organic nitrogen (WEON) using C:N analysis of water extracts [2].

- Community Structure: Employ molecular methods (16S rRNA sequencing for bacteria, ITS for fungi) to characterize microbial diversity [1].

Chemical Analysis:

- Soil Organic Matter: Quantify via loss on ignition at 400°C for 16 hours [2].

- Cation Exchange Capacity: Measure using ammonium acetate extraction at pH 7.0 followed by elemental analysis via ICP-OES [4].

- Nutrient Availability: Extract plant-available nutrients (NO₃⁻-N, NH₄⁺-N, P, K) using appropriate extractants followed by spectrophotometric or ICP analysis [4].

Physical Analysis:

- Aggregate Stability: Assess via wet-sieving method to determine water-stable aggregates.

- Water Holding Capacity: Determine by saturating soil cores and measuring water retention at field capacity [4].

- Bulk Density: Calculate as the dry weight of soil per unit volume.

Crop Nutrient Analysis Protocol

Standardized protocols for crop nutrient analysis are essential for generating comparable data across studies [2]:

Sample Collection: Harvest crop tissues at consistent physiological stages from multiple plants within treatment plots. Immediately freeze in liquid nitrogen to preserve labile compounds.

Sample Preparation: Lyophilize tissues and grind to a fine powder in a stainless steel blender under liquid nitrogen to prevent nutrient degradation.

Nutritional Analysis:

- Mineral Elements: Digest samples in nitric acid via microwave digestion and analyze by ICP-OES [2].

- Vitamins: Utilize HPLC with amperometric detection for vitamins E and C; mass spectrometry for vitamins K and B complexes [2].

- Phytochemicals: Quantify total phenolics and carotenoids via UV-Vis spectrophotometry using established protocols [2].

- Fatty Acids: For oilseed or animal products, analyze fatty acid profiles via gas chromatography.

Research Reagent Solutions for Soil Health-Nutrient Uptake Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Soil Health-Nutrient Uptake Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Application | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen | Plant tissue preservation | Rapid freezing to preserve labile nutrients and prevent enzymatic degradation during sample processing |

| Haney Test Reagents (H3A extractant) | Soil health assessment | Simulates root exudates to extract plant-available organic carbon and nitrogen fractions |

| Ammonium Acetate (1N, pH 7.0) | Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) | Replacement of exchangeable cations for quantification of soil nutrient retention capacity |

| ICP-OES Standards | Mineral nutrient analysis | Calibration and quantification of macro/micronutrients in soil extracts and plant digests |

| HPLC/MS Grade Solvents | Vitamin and phytochemical analysis | High-purity mobile phases for separation and detection of heat-labile compounds |

| DNA Extraction Kits (MoBio PowerSoil) | Microbial community analysis | Isolation of high-quality DNA from soil for sequencing-based characterization of microbiota |

| Enzyme Assay Kits (β-glucosidase, phosphatase) | Microbial functional analysis | Quantification of extracellular enzyme activities related to C, N, P cycling |

Mechanistic Framework: Soil-Plant-Microbe Signaling Pathways

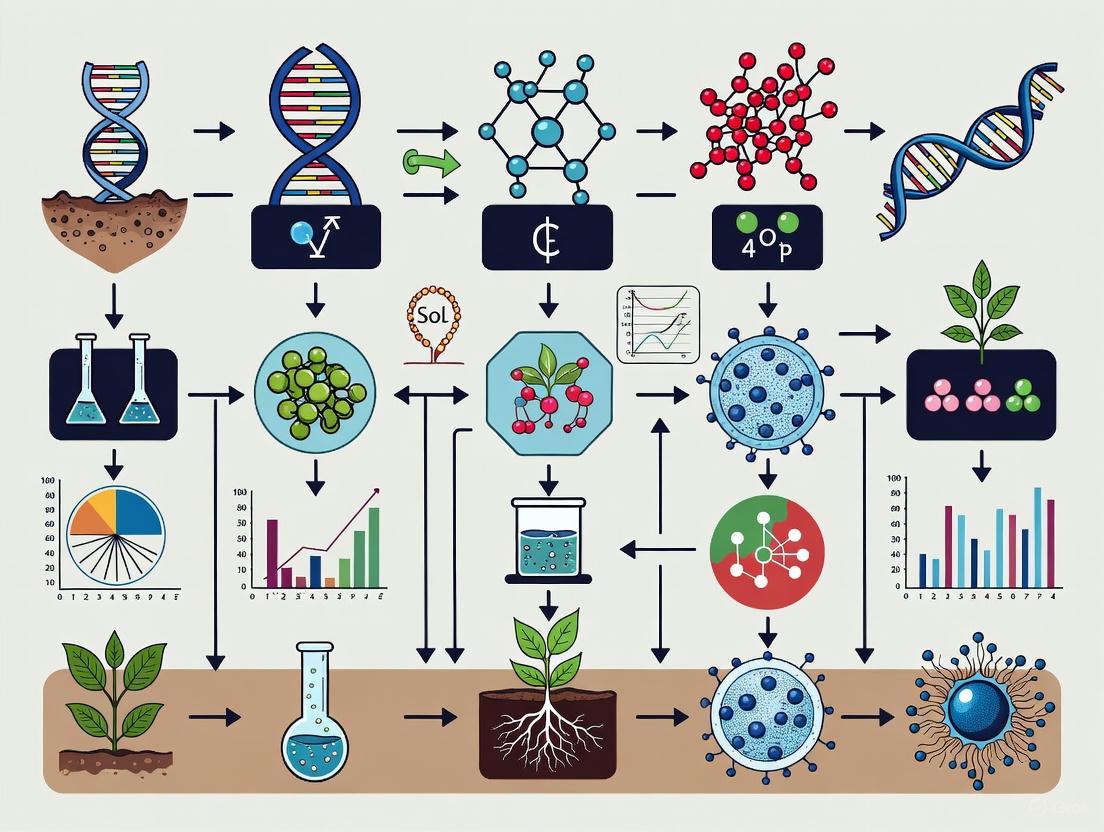

The relationship between soil health and plant nutrient biosynthesis is governed by interconnected signaling pathways that coordinate plant responses to soil conditions. The following diagram illustrates key mechanistic pathways through which soil health parameters influence nutrient uptake and biosynthesis.

The mechanistic framework illustrates how soil health components trigger a cascade of physiological responses in plants. Enhanced soil organic matter and improved soil structure influence root exudation patterns, which in turn shape microbial community composition and activity [1]. These microbial communities produce signaling molecules that activate plant defense responses, resulting in increased production of defense-related phytochemicals [2]. Simultaneously, improved nutrient mineralization and availability upregulate nutrient transporter activity, enhancing mineral uptake that serves as cofactors for enzymatic processes in vitamin and phytochemical biosynthesis pathways [4] [2]. The integrated outcome is a crop with enhanced nutritional density across multiple compound classes.

The direct link between soil health and plant nutrient uptake/biosynthesis represents a critical frontier in sustainable agriculture and nutritional science. Evidence from paired farming systems and amendment trials demonstrates that management practices enhancing soil organic matter, microbial activity, and soil physical structure consistently produce crops with elevated levels of minerals, vitamins, and phytochemicals [4] [2]. The mechanistic basis for this relationship involves complex soil-plant-microbe signaling pathways that influence both nutrient availability and plant metabolic investments in defense-related compounds.

Future research should prioritize several key areas: (1) developing more sensitive and standardized soil health indicators that reliably predict crop nutritional outcomes [1]; (2) elucidating specific microbial taxa and consortia that enhance nutrient density [1]; (3) quantifying tradeoffs between yield and nutrient density across different soil management regimes [5]; and (4) expanding research to include a broader range of crop species and agroecological contexts. For drug development professionals, these findings highlight the potential to strategically manage soil health to optimize crops for specific nutraceutical compounds, creating novel opportunities to enhance human health through agricultural management.

Soil degradation represents a pervasive and often overlooked threat to global food security and human health. Current estimates indicate that nearly 1.7 billion people reside in areas where land degradation is directly compromising crop yields and threatening food security [6]. This degradation is not merely a reduction in quantity but also in quality—a phenomenon known as nutrient dilution, where the nutritional value of crops is declining even as yields may be maintained through agricultural intensification. The crisis is extensive, with approximately one-third of the Earth's soil already at least moderately degraded, and over half of all agricultural land experiencing some form of degradation [7]. This silent emergency undermines the foundation of our food systems, as an astonishing 99 percent of the world's daily calorie intake can be traced back to soil [7].

The degradation process encompasses physical, chemical, and biological deterioration of soil resources. Chemically, essential plant nutrients are being depleted at alarming rates. Research indicates that global agricultural soils have experienced a 42 percent decrease in nitrogen, a 27 percent decrease in phosphorus, and a 33 percent decrease in sulfur [7]. These declines directly impact the nutritional quality of food crops, with studies documenting reductions in essential minerals and vitamins in fruits, vegetables, and grains over the past several decades [7]. This paper examines the interconnected mechanisms driving soil degradation and nutrient dilution, presents methodologies for assessment and remediation, and proposes an integrated framework for soil health management to enhance the nutritional quality of crops within broader research on sustainable food systems.

Mechanisms Linking Soil Health to Crop Nutritional Quality

Biochemical Pathways from Soil to Human Nutrition

The connection between soil health and crop nutritional quality operates through multiple biochemical pathways that influence nutrient uptake, assimilation, and transformation within plants. Soil serves as the primary reservoir for essential elements that plants absorb through their root systems, mediated by complex interactions with soil microorganisms. The rhizosphere—the zone of concentrated microbial activity surrounding plant roots—represents the most active interface for nutrient exchange between soil and plants [8]. In this critical zone, plants exude organic compounds to attract and feed microbes that, in turn, facilitate the solubilization and uptake of essential nutrients [9] [8].

The nutritional quality of crops is particularly dependent on the availability of both macronutrients and micronutrients in soil. Nitrogen availability directly influences protein synthesis in plants, while phosphorus is essential for energy transfer and genetic material. Sulfur plays a critical role in the synthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine and methionine) and glucosinolates—sulfur-containing compounds in cruciferous vegetables that break down into molecules with anti-carcinogenic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties [10]. The depletion of these essential nutrients from agricultural soils directly compromises the synthesis of these health-promoting compounds in crops.

Climate change introduces additional complexity to these relationships, as rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns disrupt essential soil processes. For each 1°C increase in temperature, pest incidence is estimated to increase by 10-25% while major crop yields may decline by up to 7.4% [3]. These climate-induced stresses further compromise plant metabolic processes that determine nutritional quality, creating a feedback loop that exacerbates nutrient dilution in food crops.

Table 1: Documented Declines in Crop Nutrient Content (1950-1999)

| Nutrient | Average Reduction | Crop Examples | Primary Soil Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | 16% | Fruits, Vegetables | Reduced soil organic matter, acidification |

| Phosphorus | 27% | Grains, Legumes | Depletion of soil phosphorus reserves |

| Iron | 15% | Leafy Greens, Legumes | Impaired microbial iron cycling |

| Riboflavin | 38% | Cereals, Vegetables | Reduced microbial activity in rhizosphere |

| Vitamin C | 6% | Fruits, Vegetables | Oxidative stress from environmental pressures |

| Protein | 30-50% (in corn, 1920-2001) | Cereals | Nitrogen depletion and imbalance with carbon |

Impact of Agricultural Management Practices

Modern agricultural practices have dramatically accelerated the process of nutrient depletion through several interconnected mechanisms. Monoculture cropping systems deplete specific soil nutrients through continuous extraction of the same nutrient profiles, while reducing the biodiversity of soil microorganisms that support nutrient cycling [7]. The problem is self-reinforcing—as soils become degraded, they require increasing inputs of synthetic fertilizers to maintain yields, but these inputs often further disrupt soil biological communities and nutrient balance.

Synthetic fertilizers present a particular challenge to soil health and crop nutritional quality. While initially boosting plant growth, their intensive application can disrupt the delicate symbiotic relationships between plants and soil microbes [7]. Approximately 50% or more of applied nitrogen fertilizers leach into the environment rather than being taken up by crops, causing widespread pollution while simultaneously destroying vital soil microbes that mediate nutrient uptake [7]. This inefficient nutrient utilization creates a vicious cycle where plants become increasingly dependent on synthetic inputs while their capacity to naturally acquire nutrients from soil organic matter declines.

Tillage-based farming practices, used on 93% of the world's cropland, exacerbate these problems by reducing microbial populations, promoting soil erosion, and releasing greenhouse gases [7]. Tillage disrupts soil aggregate structures that protect organic matter and creates a hostile environment for the fungal networks that transport micronutrients to plant roots. The combined impact of these intensive practices is the simplification of soil ecosystems, reducing their functional capacity to support the complex biochemical processes that yield nutritionally complete crops.

Quantitative Assessment of Soil Degradation and Nutrient Depletion

Global Patterns in Soil Nutrient Status

The capacity of soils to support nutritious crop production varies dramatically across global agricultural systems, influenced by inherent soil characteristics, climate conditions, and management histories. Certain soil types are particularly crucial for global food production. Mollisols, characterized by rich accumulations of organic matter, are among the most intensively farmed soils globally, particularly in the Americas, Europe, and Asia, where they cover approximately 17% of the global land surface [11]. Similarly, Alfisols and Inceptisols, which cover approximately 15% of global land area, support intensive agriculture due to their favorable nutrient availability and physical structure [11].

Research reveals troubling patterns in how soil resources are allocated within the global food system. Soils richest in nitrogen and organic matter—which support the highest crop yields—are predominantly dedicated to producing livestock feed or biofuels rather than direct human nutrition [11]. For example, in the United States, less than 10% of calorie production from cropland is used for direct human consumption, with the majority being diverted to animal feed and industrial uses [11]. This represents a significant inefficiency in the nutrient utilization pathway from soil to human nutrition.

International trade further complicates these patterns, resulting in massive transfers of embedded soil nutrients across continents. Model estimates suggest that the movement of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in agricultural products reached 8.8 teragrams (Tg) between 1997 and 2020, with this transfer doubling over that period [11]. This nutrient redistribution often moves resources from regions of production to consumption centers where nutrients accumulate in waste streams rather than being returned to agricultural soils, creating a one-way flow that depletes soils in production regions.

Table 2: Soil Health Indicators and Methodologies for Assessing Nutrient Availability

| Indicator | Methodology | Interpretation | Relationship to Crop Nutrition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Organic Matter (SOM) | Loss-on-ignition (660-750°F for 2 hours) | Percentage of organic material in soil; >3.5% generally favorable | Primary reservoir of nutrients; correlates with nutrient retention |

| Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) | Dry combustion elemental analyzer (>1800°F) | 50% of SOM; energy source for soil microbes | Directly influences synthesis of plant compounds |

| Potentially Mineralizable Nitrogen (PMN) | Anaerobic incubation (104°F for 7 days) | Measure of N available from organic matter via microbial activity | Predicts seasonal nitrogen availability for protein synthesis |

| Permanganate Oxidizable Carbon (POXC) | Colorimetric reaction with potassium permanganate | Reactive fraction of SOC related to decomposition activity | Indicator of active carbon available for microbial nutrient cycling |

| Autoclaved Citrate Extractable (ACE) Protein | Extraction with citrate under high temperature/pressure | Mineralizable pool of organic soil nitrogen | Primary available N source for plant uptake and assimilation |

| Aggregate Stability | Wet-sieving methods | Resistance of soil aggregates to disintegration | Protects soil organic matter and creates habitat for microbes |

Methodologies for Assessing Soil Health and Nutrient Availability

A multifunctional indicator framework for soil health assessment moves beyond single metrics to evaluate the delivery of multiple ecosystem services simultaneously [12]. This approach enables researchers to identify trade-offs between different services—such as between immediate crop productivity and long-term nutrient cycling capacity—and to contextualize soil health within specific soil types and land uses. Advanced statistical approaches, including Bayesian Belief Networks, can integrate diverse data sources to create a comprehensive picture of soil functional capacity [12].

Laboratory assessment of soil health has evolved to include a suite of physical, chemical, and biological indicators that collectively reflect the soil's capacity to support nutritious crop production. The Potentially Mineralizable Carbon (MinC) test, also known as carbon respiration or the CO₂ burst test, measures microbial abundance and activity by quantifying the conversion of soil organic carbon to CO₂ under controlled laboratory conditions [13]. This indicator reflects the "biological engine" of the soil that drives nutrient cycling and availability. Similarly, the Potentially Mineralizable Nitrogen (PMN) test measures the portion of soil organic nitrogen that can be converted to plant-available forms, providing insight into a soil's capacity to supply nitrogen throughout the growing season [13].

These assessment methodologies provide the scientific foundation for developing targeted management strategies to address specific limitations in soil nutrient availability. By identifying constraints at the physical, chemical, and biological levels, researchers and land managers can implement precision interventions to enhance both crop productivity and nutritional quality.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Soil Health Management Interventions

Research into soil health management has identified several core principles that support both agricultural productivity and crop nutritional quality. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service outlines four key principles for effective soil health management: (1) Maximize presence of living roots, (2) Minimize disturbance, (3) Maximize soil cover, and (4) Maximize biodiversity [8]. These principles work synergistically to create conditions that support robust nutrient cycling and reduce losses from the system.

Living roots maintain the rhizosphere—an area of concentrated microbial activity where peak nutrient and water cycling occurs [8]. By extending the duration of living root coverage through cover crops or extended rotations, farmers can provide a continuous food source for soil microbes that facilitate nutrient acquisition. Minimizing disturbance, particularly through reduced tillage or no-till practices, protects soil organic matter and the habitat for soil organisms, while also reducing erosion that preferentially removes nutrient-rich soil particles [8]. One study found that soils managed with no-till for several years contained more organic matter and moisture for plant use, supporting better nutrient cycling and root growth [8].

Maximizing soil cover through cover crops, crop residues, or living mulches protects soil from erosive forces, moderates soil temperature, and reduces moisture loss, creating more favorable conditions for nutrient uptake. Diverse cropping systems and cover crop mixtures enhance biodiversity both above and below ground, creating complementary root architectures and microbial communities that more efficiently capture and cycle nutrients [8]. Research demonstrates that biodiversity is ultimately the key to success in any agricultural system, as a diverse and fully functioning soil food web provides for nutrient, energy, and water cycling that allows soil to express its full productive and nutritional potential [8].

Diagram 1: Soil Management to Nutritional Quality Pathway

Soil Amendment and Remediation Strategies

Research on specific soil amendments demonstrates their potential for addressing nutrient deficiencies and enhancing crop nutritional quality. Studies conducted at Kentucky State University examined the effects of biochar and organic manure on soil health and heavy metal remediation [10]. While biochar applications showed benefits for soil properties, researchers noted that it could also inhibit important soil enzymes, indicating that its application requires careful management to avoid unintended consequences on soil biological activity [10].

Phytoremediation approaches using specific plant species offer promise for addressing soil contamination while potentially producing nutrient-dense crops. Research demonstrates that potato plants can effectively remove heavy metals from contaminated soils, though this highlights the importance of differentiating between crops grown for consumption versus those used specifically for environmental cleanup [10]. This distinction is critical for ensuring food safety while utilizing agricultural systems for soil restoration.

The integration of organic amendments with mineral fertilizers represents a balanced approach to addressing nutrient depletion while building long-term soil health. Research indicates that practices such as co-composting biochar with organic manure can help mitigate heavy metal contamination while improving soil fertility [10]. These integrated approaches support both immediate crop nutrient needs and the long-term capacity of soils to supply nutrients through biological processes.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Soil Health and Crop Nutrition Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Analytical Function | Application in Soil-Crop Research |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate | Oxidizes labile carbon fractions | Quantification of Permanganate Oxidizable Carbon (POXC) as indicator of active soil carbon |

| Citrate Solution with Autoclaving | Extracts protein-like substances from soil | Measurement of ACE protein as mineralizable nitrogen pool |

| Elemental Analyzer | High-temperature combustion for carbon/nitrogen | Determination of total Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) and Total Nitrogen (TN) |

| Anaerobic Incubation Chamber | Maintains specific temperature/moisture conditions | Measurement of Potentially Mineralizable Nitrogen (PMN) under standardized conditions |

| CO₂ Respiration System | Sealed containers with gas measurement | Quantification of Mineralizable Carbon (MinC) as indicator of microbial activity |

| Wet-Sieving Apparatus | Separates soil aggregates by size class | Assessment of aggregate stability as indicator of soil physical structure |

| Potassium Bromide | Reference standard for spectral analysis | Calibration of instruments for precise nutrient quantification |

Field Study Protocols for Assessing Management Impacts

Well-designed field studies are essential for quantifying the impact of soil management practices on both soil health parameters and crop nutritional quality. A robust experimental approach should include standard protocols for assessing treatment effects across multiple growing seasons to account for temporal variability in soil processes and weather conditions.

Soil sampling protocols should collect composite samples from consistent depth increments (typically 0-15 cm for routine assessment, and 0-30 cm or deeper for carbon stock quantification) [13]. Sampling timing should be consistent relative to crop growth stages and management events, with preferred timing being before planting or after harvest to assess baseline conditions. For assessment of potentially mineralizable nitrogen, the anaerobic incubation method involves immersing soil samples in water and maintaining them at 104°F for seven days, then measuring the accumulation of ammonium [13]. This protocol provides a standardized approach for comparing nitrogen mineralization capacity across different management treatments.

For evaluation of crop nutritional quality, plant tissue sampling should target specific growth stages and plant parts relevant to human consumption. Analysis of mineral nutrients in plant tissues typically involves dry ashing or acid digestion followed by quantification using ICP-OES or similar instrumentation. Measurement of specific phytochemicals, such as the glucosinolates in cruciferous vegetables, requires specialized extraction and chromatographic techniques to quantify these health-promoting compounds [10].

Long-term monitoring is particularly valuable for detecting changes in soil health parameters that may evolve slowly over time. Studies examining the economic and environmental impacts of soil health practices have documented outcomes over periods of 5-15 years, revealing that benefits often increase with the duration of practice implementation [14]. This longitudinal approach provides critical insights into the trajectory of soil health improvement and its relationship to crop nutritional quality.

Economic and Environmental Outcomes of Soil Health Management

Economic Viability of Soil Health Practices

Case studies examining the economic impacts of soil health practices demonstrate their potential to improve farm profitability while enhancing environmental outcomes. An analysis of 26 soil health case studies, including 23 row crop farmers and 3 almond growers, found that the majority of producers achieved both yield increases and improved net income through adopting soil health management systems [14]. Among row crop producers, 20 of 23 farmers attributed yield increases to soil health practices, valued at $16 to $356 per acre based on national average crop prices [14]. The economic benefits were even more pronounced for almond growers, who saw yield increases valued at $519 to $1,156 per acre [14].

Return on investment (ROI) calculations provide further evidence of the economic efficiency of soil health investments. Among row crop farmers with positive net returns, ROI ranged from 7% to 345%, while almond growers achieved remarkable returns between 198% and 553% [14]. These figures demonstrate that well-managed soil health systems can deliver both ecological and economic benefits, addressing a critical barrier to adoption of more sustainable agricultural practices.

The specific economic benefits varied based on the practices implemented and local conditions. Farmers who adopted no-till or reduced tillage systems typically realized savings of $17 to $92 per acre in machinery, fuel, and labor costs by reducing field passes [14]. Those implementing precision nutrient management often reduced fertilizer expenses by $5 to $84 per acre through more efficient application [14]. These economic advantages, combined with potential premium prices for nutritionally enhanced crops, create compelling business cases for investment in soil health.

Diagram 2: Economic and Environmental Dimensions of Soil Health

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite growing evidence of the connections between soil health and crop nutritional quality, significant research gaps remain. A critical need exists for long-term, multidisciplinary studies that simultaneously track changes in soil health indicators, crop nutrient density, and economic outcomes across diverse production systems and agroecological regions [3] [9]. Such studies would provide stronger evidence for causal relationships and enable the development of predictive models for how specific management interventions influence nutritional outcomes.

Research on the mechanisms linking soil microbial communities to plant nutrient uptake and assimilation represents another priority area. While it is established that diverse cropping systems enhance soil ecology and microbial diversity [9], the specific microbial functions that influence the synthesis of health-promoting compounds in crops require further elucidation. Advanced techniques in metagenomics and metabolomics offer promising approaches for unraveling these complex relationships and identifying key microbial taxa and processes that can be targeted for management.

From a methodological perspective, development of rapid, cost-effective indicators of crop nutritional quality would facilitate more extensive monitoring and research. Current methods for analyzing phytochemical composition are often expensive and technically demanding, limiting their widespread application in field research and commercial agriculture. Innovation in sensing technologies, including spectral reflectance and hyperspectral imaging, may enable non-destructive assessment of nutritional parameters at field scales.

Finally, research is needed to better understand the socioeconomic and policy dimensions of transitioning to soil health-focused production systems. While technical solutions exist, their adoption faces barriers related to knowledge, economics, and policy incentives. Studies examining effective approaches for overcoming these barriers, particularly for small-scale farmers who produce over 50% of the world's food [11], are essential for scaling soil health practices globally.

The interconnected crises of soil degradation and nutrient dilution in global food systems demand urgent attention from researchers, policymakers, and agricultural practitioners. The evidence presented demonstrates that conventional agricultural approaches have inadvertently compromised the foundational resource that supports human nutrition—healthy soil. The decline in essential nutrients in food crops coincides with widespread degradation of agricultural soils, suggesting an intrinsic connection between soil health and the nutritional quality of the food it produces.

Addressing this challenge requires a fundamental shift toward holistic soil health management that integrates advanced agronomic practices, innovative technologies, and supportive policy frameworks [3]. The principles of maximizing living roots, minimizing disturbance, maintaining soil cover, and enhancing biodiversity provide a robust foundation for rebuilding soil health and restoring the nutrient density of food crops [8]. Emerging evidence suggests that such approaches can deliver both economic benefits for producers and environmental benefits for society, while simultaneously addressing the hidden crisis of nutrient dilution in our food supply.

For researchers, this field presents compelling opportunities to investigate the complex interactions between soil management, crop physiology, and human nutrition. Interdisciplinary collaborations spanning soil science, plant physiology, microbiology, nutrition, and economics will be essential for developing comprehensive solutions. By placing soil health at the center of agricultural research and innovation, we can work toward food systems that simultaneously deliver productivity, sustainability, and enhanced nutritional quality to meet the needs of a growing global population.

The pursuit of enhanced nutritional quality in crops has traditionally focused on managing primary macronutrients (NPK). However, contemporary research reveals that soil organic matter (SOM) and the soil microbial community are fundamental drivers in the production of plant bioactive compounds, presenting a new frontier for managing crop nutritional quality [15]. Soil organic matter serves as both a reservoir of nutrients and a substrate for the complex soil food web, creating a dynamic biological interface that influences the phytochemical composition of plants [16] [8]. This relationship between soil biology and plant chemistry opens transformative opportunities for agriculture aimed at producing crops with enhanced nutraceutical properties and for the discovery of novel bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical development [17] [18].

The formation and persistence of SOM are now recognized as being fundamentally shaped by microbial activity [19]. Microorganisms, through their metabolic processes and cellular residues, contribute directly to various SOM functional pools, including particulate organic matter (POM) and mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) [19]. This microbial transformation of organic inputs creates a foundation for soil health that supports plant physiological processes essential for the synthesis of valuable secondary metabolites, including phenolics, alkaloids, and flavonoids with demonstrated human health benefits [17] [20] [21].

Soil Organic Matter: Foundation for Bioactive Compound Production

Composition and Functions of Soil Organic Matter

Soil organic matter is a complex mixture consisting of approximately 5% living organisms, 10% crop residues, 33-50% decomposing organic matter (the active fraction), and 33-50% stable organic matter (humus) [16]. This composition highlights SOM as a dynamic, living system rather than an inert material. The active fraction of organic matter readily changes mass and form as it decomposes, making it unstable in the soil but highly responsive to management practices such as tillage, cover crops, and crop rotations [16]. This rapid turnover contributes significantly to nutrient release for crops. In contrast, humus represents organic material converted by microorganisms to a resistant state of decomposition, acting as a long-term reservoir for nutrients, increasing water holding capacity, improving soil structure, and providing energy for soil organisms [16].

The well-documented benefits of organic matter can be summarized into five key functional areas [16]:

- Biological Function: Enhances microbial diversity and activity, with microorganisms excreting compounds that act as binding agents for soil particles, increasing aggregate stability, water infiltration, and water holding capacity.

- Nutrient Supply: Provides a valuable nutrient source through mineralization and contributes cation exchange capacity (CEC) for retaining positively charged ions like calcium, potassium, and magnesium.

- Soil Structure: Binds soil particles into stable aggregates, improving water infiltration and reducing surface crusting.

- Water Holding Capacity: Absorbs and holds up to 90% of its weight in water, releasing most absorbed water to plants.

- Erosion Control: Increases aggregate stability and water infiltration, reducing erosion potential by 20-33% when SOM increases from 1% to 3%.

Quantitative Benefits of Soil Organic Matter for Crop Nutrition

The relationship between SOM and crop nutritional quality is not merely theoretical but demonstrates quantifiable impacts. Research has established significant correlations between SOM fractions and the nutrient composition of food crops, with particular relevance for addressing hidden hunger through agricultural management [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Benefits of Soil Organic Matter on Crop Productivity and Nutritional Quality

| Soil Organic Matter Parameter | Impact on Crop | Quantitative Benefit | Human Health Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall SOM Increase | Yield potential | Maximum yields achieved at ~3.75% SOM [16] | Foundation for food security |

| Organic Matter Nitrogen | Wheat yield & protein content | Positive relationship with yield and protein [15] | Addressing protein deficiency |

| Organic Matter Carbon | Wheat zinc content | 1% increase → Zinc for 0.2 additional persons/ha [15] | Combating micronutrient deficiency |

| Water Holding Capacity | Drought resilience | 1% SOM increase → 0.2-0.3 inch increase in available water [16] | Stabilizing yields under stress |

The nutritional impact extends beyond basic yields. Research in smallholder agricultural systems demonstrated that increasing organic matter carbon by 1% was associated with an increase in zinc content equivalent to the needs of 0.2 additional people per hectare, while increasing organic matter nitrogen by 1% was associated with an increase in protein equivalent to the daily needs of 0.1 additional people per hectare [15]. These findings position SOM management as a viable strategy for enhancing the nutritional density of food crops.

Microbial Pathways to Bioactive Compound Production

The Soil Food Web as a Metabolic Engine

Soil is "teaming with billions of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes that are the foundation of an elegant symbiotic ecosystem" [8]. This soil food web constitutes a metabolic engine that drives the cycling of carbon and nutrients, subsequently influencing plant metabolism and the synthesis of bioactive compounds. The rhizosphere—the zone of soil directly influenced by plant roots—represents the most active part of the soil ecosystem, where peak nutrient and water cycling occurs [8]. Plants exude compounds through their roots to attract and feed specific microbes that, in turn, provide nutrients and other bioactive compounds to the plant [8].

This relationship creates a sophisticated trading system where plants invest photosynthetic carbon to cultivate microbial communities that enhance their access to nutrients and water, while also influencing their secondary metabolite production. Microbial activity thus becomes a key determinant of the phytochemical profile of medicinal plants and food crops with nutraceutical value [17].

Fungal Traits and Soil Organic Matter Formation

Different microbial species possess distinct traits that influence their capacity to form various SOM functional pools. Research has identified that "multifunctional" fungal species with intermediate investment across key traits—including carbon use efficiency, growth rate, turnover rate, and biomass protein and phenol contents—promote SOM formation, functional complexity, and stability [19]. This challenges earlier categorical frameworks that described simple binary trade-offs between microbial traits, instead emphasizing the importance of synergies among microbial traits for the formation of functionally complex SOM.

Table 2: Key Fungal Traits Influencing Soil Organic Matter Formation and Stability

| Trait Category | Specific Traits | Relationship to SOM Pools |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Traits | Carbon Use Efficiency (CUE), Growth Rate, Turnover Rate | Primary drivers of microbial residue inputs to soils; strongest predictors of total soil C [19] |

| Biochemical Traits | Biomass Protein Content, Phenol Content, Melanin Content | Influence organo-mineral interactions and stabilization in MAOM pool [19] |

| Morphological Traits | Hyphal Length, Hyphal Surface Area per Soil Volume | Affect physical protection of SOM and degree of microbe-mineral interactions [19] |

| Trait Integration | Trait Multifunctionality | Species with intermediate investment across multiple traits promote SOM functional complexity and stability [19] |

The relationship between microbial traits and SOM pool formation reveals that no single trait dictates SOM dynamics but rather synergistic combinations of traits determine outcomes. Physiological traits such as CUE act as initial filters on the pool of microbial residues available for incorporation into SOM, while biochemical and morphological traits regulate the subset of those residues that become stabilized in soils [19]. This sophisticated understanding enables more targeted management of soil microbial communities to enhance specific SOM functional pools.

From Soil to Medicine: The Pathway of Bioactive Compounds

Bioactive compounds derived from plants and microbial sources are required for the survival of the human race, with both serving as major sources of naturally occurring compounds for numerous biotechnological applications [17]. The soil environment directly influences the quality and potency of these compounds through multiple parameters, including heavy metal content, pH, organic matter composition, and the phytoremediation process [17].

Medicinal plants are abundant in secondary metabolites—including alkaloids, steroids, tannins, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids—that elicit specific physiological effects on the human body [21]. These phytochemicals, particularly in high concentrations, protect plants from free radical damage and hyperaccumulation, while also providing humans with compounds for treating harmful diseases [17]. Contemporary drug discovery continues to rely heavily on these natural product pathways, with genome mining and biosynthetic engineering opening new frontiers for discovering novel bioactive compounds from microbial sources [18].

Diagram 1: Relationship between soil health and human health. This pathway illustrates how soil health management influences soil organic matter and microbial communities, which subsequently affect plant physiology and the production of bioactive compounds with therapeutic benefits for human health.

Management Strategies for Enhancing Soil Health and Bioactive Compounds

The Four Principles of Soil Health Management

The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service has established four core principles for effective Soil Health Management Systems that align directly with goals of enhancing bioactive compound production in plants [8]:

Maximize Presence of Living Roots: Living plants maintain a rhizosphere where peak nutrient and water cycling occurs. Growing long-season crops or cover crops following short-season crops provides consistent food for soil microbes, supporting the foundation species of the soil food web [8].

Minimize Disturbance: Tillage destroys soil organic matter and structure, damaging the habitat for soil organisms. Reduced tillage or no-till systems preserve organic matter, improve water infiltration, reduce erosion, and enhance nutrient cycling [8].

Maximize Soil Cover: Maintaining soil cover through cover crops, crop residues, and living mulches protects soil from wind and water erosion. Cover crops also contribute to restoring soil health by adding living roots and organic matter, improving water infiltration, and trapping excess nutrients [8].

Maximize Biodiversity: Increasing diversity through crop rotations, cover crop mixes, and integration of grazing animals helps prevent disease and pest problems. Diversity above ground improves diversity below ground, creating healthier soils and more resilient systems [8].

Practical Interventions for Increasing Soil Organic Matter

Building soil organic matter is a slow process that requires the addition of substantial plant biomass and protection from loss over time [16]. Several management practices specifically target SOM enhancement:

- Minimize tillage or adopt no-till: Slows the decomposition of soil organic residue and provides greater protection from erosion [16].

- Add crop residues: Include cover crops, organic amendments (e.g., residues, manure), or grow high biomass/yielding crop rotations. Crop residues protect the soil surface and add carbon back to the soil [16].

- Soil test and apply advanced crop nutrition: Identify and correct yield-limiting factors to encourage greater crop growth that can be returned to the soil. Adding essential nutrients can create more productive and sustainable cropping systems [16].

These practices collectively contribute to what is termed "ecological intensification"—an approach that leverages ecological processes to enhance agricultural productivity and sustainability, as opposed to relying solely on external inputs [15].

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions for Soil Bioactivity Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Studying Soil Microbes and Bioactive Compounds

| Research Tool Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Analysis Tools | AntiSMASH, DeepBGC, Genome Mining | Identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in microbial genomes for novel bioactive compounds [18] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | LC-MS/MS, GNPS, Mass Spectrometry | Streamline dereplication and annotation of natural product libraries [18] |

| Soil Fractionation Methods | Particulate OM (POM), Mineral-Associated OM (MAOM) | Isolate and analyze different functional pools of soil organic matter [19] [15] |

| Microbial Cultivation | Axenic model soils, Selective media | Study individual microbial species' contributions to SOM formation and bioactivity [19] |

| Trait-Based Frameworks | Carbon Use Efficiency (CUE), Growth Rate, Biomass Chemistry | Link microbial identity and function to SOM formation and stabilization [19] |

Methodologies for Assessing Soil-Bioactive Relationships

Research on the relationship between soil properties and bioactive compound production employs sophisticated experimental designs:

Model Soil Incubations: Studies using individual species of fungi incubated in SOM-free model soils allow researchers to directly relate physiological, morphological, and biochemical traits of fungi to their SOM formation potentials [19]. This approach enables precise characterization of a suite of microbial traits including CUE, growth rate, turnover rate, extracellular enzyme production, biomass chemistry, melanin content, hyphal length, and surface area per soil volume [19].

Land-Use Gradient Studies: Research conducted along gradients of land use and land cover (e.g., distance from forests, different management intensities) helps identify how SOM fractions respond to environmental and management factors, and how these relate to crop nutrient composition [15]. These observational studies in working landscapes provide real-world validation of relationships discovered in controlled settings.

Phytochemical Analysis: Standardized methods for extracting and identifying plant secondary metabolites—including alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, and glycosides—are essential for quantifying the production of bioactive compounds [17] [20]. These are complemented by bioassays testing antimicrobial activity through zone of inhibition measurements and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations [17].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for soil-bioactivity research. This workflow outlines the key phases in researching relationships between soil properties, microbial communities, and plant bioactive compounds, from initial assessment through data integration to practical applications.

The investigation of soil ecosystems "beyond NPK" reveals a sophisticated interplay between soil organic matter, microbial communities, and the production of bioactive compounds in plants. Soil organic matter serves not merely as a nutrient source but as the foundational substrate for microbial communities whose traits directly influence both the quantity and functional complexity of SOM pools. The management of soil health through practices that maximize living roots, minimize disturbance, maintain soil cover, and enhance biodiversity creates conditions favorable for the production of bioactive compounds with significant human health applications.

This integrated understanding enables a more nuanced approach to agricultural management—one that recognizes the soil as a living system that can be strategically managed to enhance the nutritional and therapeutic quality of crops. For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights open new pathways for discovering novel bioactive compounds through better understanding of how soil management influences plant phytochemistry. The convergence of traditional agricultural knowledge with modern technologies in genomics, metabolomics, and bioinformatics creates unprecedented opportunities to harness the soil-plant system for improved human health outcomes while maintaining ecological sustainability.

The profound connection between soil health and human health represents a foundational principle in sustainable agriculture, yet its mechanistic underpinnings remain insufficiently explored in contemporary agricultural and biomedical research. Soil health is defined as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans [8]. This definition encompasses the soil's ability to regulate water, sustain plant and animal life, filter and buffer potential pollutants, cycle nutrients, and provide physical stability and support. Within this context, phytochemicals—bioactive non-nutrient compounds produced by plants—have emerged as critical mediators between agricultural practices and human health outcomes, particularly in cancer prevention [22]. The investigation of glucosinolates, a prominent class of sulfur-containing phytochemicals found predominantly in Brassica vegetables, provides a compelling model system for understanding how soil management practices can influence the production of cancer-preventive compounds in food crops [23] [24].

The concept that soil health directly influences the nutritional quality of food crops has evolved from philosophical assertion to scientific inquiry. Evidence suggests that farming systems utilizing soil health-building practices enhance not only soil organic matter and microbial activity but also the concentration of health-promoting phytochemicals in food crops [25]. This relationship is particularly relevant for glucosinolates, which require specific soil conditions and nutrient availability for optimal biosynthesis [23]. The emerging paradigm posits that deliberate soil management represents a powerful, yet underutilized, strategy for enhancing the chemopreventive potential of agricultural systems, creating a sustainable approach to cancer prevention through whole foods.

Glucosinolates: Chemistry, Biosynthesis, and Mechanisms of Cancer Prevention

Chemical Structure and Classification

Glucosinolates are a major class of sulfur- and nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites derived from amino acids and characterized by a core structure consisting of a β-D-thioglucose moiety, a sulfonated oxime group, and a variable side chain derived from different amino acid precursors [24]. These compounds are systematically classified based on their amino acid origin into three primary categories: aliphatic glucosinolates (derived from alanine, leucine, isoleucine, valine, or methionine), aromatic glucosinolates (derived from phenylalanine or tyrosine), and indolic glucosinolates (derived from tryptophan) [26]. In intact plant tissues, glucosinolates remain stable within cell vacuoles, separated from the enzyme myrosinase (thioglucoside glucohydrolase), which is compartmentalized in separate cells [24].

The chemopreventive properties of glucosinolates are not inherent to the intact compounds but are manifested through their enzymatic hydrolysis products, primarily isothiocyanates (ITCs), which are released when plant tissue is damaged through processing, chewing, or pathogen attack [26] [24]. The transformation occurs when myrosinase catalyzes the hydrolysis of the thioglucosidic bond in glucosinolates, resulting in unstable thiohydroximate-O-sulfonates that spontaneously rearrange to form ITCs, nitriles, or other products depending on physiological conditions [24]. These bioactive hydrolysis products, particularly ITCs, have demonstrated potent anticancer activities through multiple molecular mechanisms.

Anticancer Mechanisms of Glucosinolate Derivatives

Glucosinolate-derived ITCs exert chemopreventive effects through multiple complementary mechanisms that target various stages of carcinogenesis. The following table summarizes the primary molecular pathways through which these compounds demonstrate anticancer activity:

Table 1: Anticancer Mechanisms of Glucosinolate-Derived Isothiocyanates

| Mechanism | Molecular Targets | Biological Outcome | Representative Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinogen Detoxification | Induction of Phase II enzymes (e.g., GST, UGT, NQO1) via Nrf2/ARE pathway activation [26] [22] | Enhanced elimination of potential carcinogens | Sulforaphane, Erucin [24] |

| Cell Cycle Arrest | Modulation of cyclins, CDKs; p53 activation [27] | Inhibition of uncontrolled proliferation at G1/S or G2/M checkpoints | Iberin, Allyl-ITC [24] |

| Apoptosis Induction | Caspase activation; Bcl-2 family protein modulation; mitochondrial membrane disruption [27] [22] | Selective elimination of precancerous and cancerous cells | Phenethyl-ITC, Benzyl-ITC [24] |

| HDAC Inhibition | Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity [26] | Reactivation of silenced tumor suppressor genes | Sulforaphane [26] |

| Anti-inflammatory Effects | Suppression of NF-κB signaling; reduced COX-2 expression [22] | Decreased tumor-promoting inflammation | Indole-3-carbinol [24] |

| Antimicrobial Activity | Induction of stringent response in bacteria [24] | Modulation of gut microbiota; reduced inflammation | 3-Butenyl, 4-Pentenyl ITCs [24] |

The following diagram illustrates the primary molecular pathways through which glucosinolate hydrolysis products exert their cancer-preventive effects:

Soil Health Management Principles for Enhanced Phytochemical Production

Foundational Principles of Soil Health Management

The United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS) has established four core principles for effective soil health management that provide a framework for enhancing phytochemical production in agricultural systems [8]. These principles are designed to create conditions that support diverse soil biological communities, efficient nutrient cycling, and optimal plant health—all factors that influence secondary metabolite production in plants:

Maximize Presence of Living Roots: Maintaining living roots throughout the growing season sustains the rhizosphere—the zone of concentrated microbial activity surrounding plant roots. This region represents the most biologically active portion of the soil ecosystem, where root exudates attract and feed microbial communities that, in turn, enhance nutrient availability to plants [8]. These microbial associations can influence plant health and phytochemical production, including glucosinolate profiles [23].

Minimize Soil Disturbance: Reducing tillage intensity and frequency preserves soil organic matter, protects soil structure, and maintains habitat for beneficial soil organisms. Tillage disrupts fungal hyphal networks, destroys soil aggregates, and accelerates organic matter decomposition, ultimately reducing the soil's capacity to support diverse microbial communities that contribute to plant health and nutrient uptake [8].

Maximize Soil Cover: Maintaining protective residue cover or living plants on the soil surface year-round reduces erosion, conserves soil moisture, moderates soil temperature, and suppresses weeds. Soil cover also provides habitat for beneficial arthropods and microorganisms while reducing water evaporation and nutrient losses [8].

Maximize Biodiversity: Increasing the diversity of plants, animals, and microorganisms in agricultural systems enhances ecosystem resilience and function. Diverse crop rotations and cover crop mixtures support more complex soil food webs, which improve nutrient cycling efficiency, suppress soil-borne diseases, and reduce pest pressures [8]. This biodiversity supports plant health and influences secondary metabolite production.

Soil Factors Influencing Glucosinolate Content in Plants

Research using Boechera stricta (a wild perennial mustard) has demonstrated that soil variation among natural habitats can alter glucosinolate content by up to 2-fold, with physico-chemical soil properties rather than microbial communities being the primary determinant of this plasticity [23]. The following table summarizes key soil factors that influence glucosinolate accumulation in plants:

Table 2: Soil Properties Influencing Glucosinolate Accumulation in Plants

| Soil Factor | Effect on Glucosinolates | Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfur Availability | Increases total glucosinolate content [23] | Sulfur is incorporated directly into glucosinolate structures; limitation reduces biosynthesis | Fertilization increased leaf glucosinolates 20-50 fold in Brassica crops [23] |

| Nitrogen Availability | Variable effects depending on form, timing, and balance with sulfur [23] | Nitrogen comprises second essential element in glucosinolates; imbalance with sulfur disrupts optimal biosynthesis | Interaction effects observed; status of other nutrients affects impact [23] |

| Soil Organic Matter | Generally enhances glucosinolate production [25] | Improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability; supports beneficial microbial communities | Organically managed soils show increased phytochemicals [25] |

| Micronutrient Availability | Alters glucosinolate profiles [23] | Cofactors for biosynthetic enzymes; influence plant stress responses | Potassium, selenium, molybdenum affect accumulation [23] |

| Soil Texture/Drainage | Impacts glucosinolate composition [23] | Affects root growth, nutrient leaching, water availability, and soil oxygenation | Variation among natural habitats correlates with glucosinolate differences [23] |

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Soil-Phytochemical Relationships

Soil Transplantation and Manipulation Studies

Controlled greenhouse experiments using soils collected from diverse natural habitats provide a powerful approach for investigating the effects of soil properties on phytochemical profiles. The following methodology outlines a comprehensive protocol for such investigations:

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Soil-Phytochemical Relationship Studies

| Experimental Phase | Procedures | Parameters Measured | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Collection | Collect soils from diverse natural habitats (forests, meadows, riparian areas) where target species grow naturally [23] | Physico-chemical properties (texture, pH, organic matter, nutrient availability); microbial community composition | Identify naturally occurring soil variation affecting phytochemicals |

| Soil Treatments | Compare: (1) intact natural soils; (2) sterilized soils (eliminates biotic factors); (3) amended soils (specific nutrient additions) [23] | Plant growth parameters; glucosinolate profiles in leaves and roots; gene expression related to biosynthesis | Disentangle abiotic vs. biotic soil effects on phytochemistry |

| Plant Cultivation | Grow genetically diverse lines of target species (e.g., Boechera stricta) in different soil treatments under controlled conditions [23] | Biomass accumulation; glucosinolate quantity and composition; reproductive fitness (seed production) | Assess genetic variation for plasticity in response to soil environment |

| Data Analysis | Correlate soil properties with phytochemical profiles; quantify genetic vs. environmental contributions to variation; analyze fitness consequences [23] | Statistical models evaluating soil factors, genotype, and their interactions on glucosinolate accumulation | Identify soil management strategies for enhancing chemopreventive compounds |

Analytical Methods for Glucosinolate Quantification

Accurate quantification of glucosinolates and their hydrolysis products requires specialized analytical approaches. The following workflow outlines standard methodologies:

Bioactivity Assessment of Glucosinolate Profiles

Evaluating the cancer-preventive potential of glucosinolates requires assessment of their biological activity using established in vitro models. The following protocol describes a standardized approach for determining antiproliferative effects:

Cell Culture and Treatment Protocol [26]:

- Cell Line: Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (HT-29)

- Culture Conditions: Maintain in appropriate medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO₂

- Glucosinolate Preparation: Prepare individual and mixed glucosinolate solutions (0.5-50 μM concentration range) in buffer

- Myrosinase Activation: Incubate glucosinolates with myrosinase enzyme (0.025 U) for 2 hours at 37°C and neutral pH to generate hydrolysis products

- Treatment Conditions:

- IND: Individual glucosinolates digested separately then combined

- COMB: Individual glucosinolates digested separately then combined in specific proportions

- MIX: Glucosinolates pre-mixed then digested together to evaluate interactions during hydrolysis

- Viability Assessment: Measure antiproliferative effects using MTT assay or similar method after 24-72 hours treatment

- Data Analysis: Calculate combination indices to identify synergistic, additive, or antagonistic interactions among different glucosinolates

Breeding and Biotechnology Approaches for Optimizing Glucosinolate Profiles

Molecular Breeding for Enhanced Chemopreventive Properties

Traditional breeding approaches have been successfully employed to develop Brassica varieties with optimized glucosinolate profiles for enhanced human health benefits. Research has demonstrated that different glucosinolates interact in complex ways, with mixture analysis identifying an optimal ratio of approximately 81-84% glucoraphanin, 9-19% gluconapin, and 0-7% other glucosinolates to maximize antiproliferative activity against colorectal cancer cells [26]. Breeding programs targeting this specific profile have successfully developed isogenic broccoli lines (e.g., VB067) with a 44% increase in antiproliferative activity compared to initial breeding parents [26].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach to developing Brassica varieties with enhanced cancer-preventive properties:

Transgenic and Biotechnological Approaches

Beyond conventional breeding, several biotechnological strategies offer precision tools for manipulating glucosinolate pathways:

- Gene Overexpression: Introduction of key biosynthetic genes under constitutive or tissue-specific promoters to enhance flux through glucosinolate pathways [24]

- RNA Interference: Targeted suppression of competing pathways or transport proteins to redirect metabolic flux toward desired glucosinolates [24]

- Transcription Factor Engineering: Modulation of regulatory genes (e.g., MYB transcription factors) that coordinate the entire glucosinolate biosynthetic network [24]

- Microbial Host Engineering: Heterologous production of glucosinolates in microbial systems for functional studies and potential nutraceutical applications [24]

- Gene Editing: Use of CRISPR/Cas9 systems for precise modification of biosynthetic genes to create novel glucosinolate profiles [24]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Glucosinolate and Soil Health Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucosinolate Standards | Glucoraphanin, Gluconapin, Progoitrin, Sinigrin, Glucoiberin [26] | HPLC quantification and identification; method validation | Purity >95% recommended; stable storage at -20°C in desiccator |

| Enzymes | Myrosinase from Sinapis alba (white mustard) seeds [26] | Hydrolysis of glucosinolates to bioactive isothiocyanates for bioactivity assays | Activity typically 2.5 U/mL; aliquot and store at -80°C; avoid freeze-thaw cycles |

| Cell Lines | HT-29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells [26] | Assessment of antiproliferative activity of glucosinolate hydrolysis products | Use passages 15-30; regular mycoplasma testing recommended |

| Soil Analysis Kits | Soil organic matter, NPK, micronutrient, pH test kits | Characterization of physico-chemical soil properties in experimental systems | Field kits suitable for rapid assessment; laboratory methods for precision |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial soil DNA extraction kits (e.g., MoBio PowerSoil) | Microbial community analysis through amplicon sequencing | Ensure efficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria and fungi |

| PCR Reagents | 16S/ITS primers, high-fidelity DNA polymerase, dNTPs | Amplification of bacterial and fungal marker genes for community profiling | Include positive and negative controls; replicate reactions recommended |

| Chromatography Supplies | C18 columns, guard columns, HPLC vials, solvents (MeOH, ACN) | Glucosinolate separation and quantification | Use high-purity solvents; column conditioning and maintenance critical |

The investigation of glucosinolates as interface molecules connecting soil health to human health represents a promising frontier in sustainable agriculture and preventive medicine. Evidence from controlled experiments demonstrates that soil properties significantly influence glucosinolate profiles in plants, with physico-chemical characteristics exerting stronger effects than microbial communities in some systems [23]. This understanding, coupled with advances in breeding and biotechnology, creates unprecedented opportunities to design agricultural systems that simultaneously enhance ecosystem health and human health.

Future research priorities should include:

- Long-Term Field Studies: Multi-year investigations across diverse agroecosystems to evaluate how soil management practices influence glucosinolate stability and bioactivity under realistic growing conditions

- Mechanistic Soil-Plant Studies: Detailed investigations into how specific soil properties (e.g., mineral nutrition, soil structure) influence signal transduction pathways regulating glucosinolate biosynthesis in plants

- Clinical Translation: Randomized controlled trials examining the health impacts of consuming Brassica vegetables grown under different soil management regimes, with particular focus on bioavailability and biomarker modulation

- Multi-Omics Integration: Application of metabolomics, transcriptomics, and microbiomics approaches to develop comprehensive models of soil-plant-phytochemical interactions

The integration of soil science with plant biochemistry and biomedical research represents a transdisciplinary approach to addressing complex challenges in public health and sustainable agriculture. By viewing agricultural systems as integrated networks connecting soil health to human health through phytochemical bridges, we can develop innovative strategies for cancer prevention that begin with management of the soil resource.

Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soils represents a critical environmental challenge with direct implications for global food security, ecosystem stability, and human health. Recent research indicates that approximately 14-17% of global cropland—roughly 242 million hectares—is contaminated by at least one toxic metal such as arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, chromium, copper, nickel, or lead at levels exceeding safety thresholds [28]. This widespread pollution poses substantial risks as these persistent contaminants enter food chains, threatening both agricultural productivity and public health.

The presence of heavy metals in soil systems disrupts the foundational principles of soil health, which is defined as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans [8]. Healthy soils perform five essential functions: regulating water, sustaining plant and animal life, filtering and buffering potential pollutants, cycling nutrients, and providing physical stability and support. Heavy metal contamination directly impairs these functions, particularly the soil's ability to filter pollutants and cycle nutrients, thereby compromising the nutritional quality of crops grown in affected areas. Within the context of soil health management for enhanced nutritional quality, understanding and mitigating heavy metal contamination becomes paramount for researchers and agricultural professionals dedicated to sustainable crop production.

Heavy metals enter agricultural systems through both geogenic (natural) and anthropogenic (human activity) pathways. Natural sources include the weathering of parent materials and volcanic eruptions, while anthropogenic sources encompass industrial activities, agricultural chemicals, and waste disposal [29] [30]. Understanding these sources is crucial for developing effective management strategies.

Agricultural Inputs: Chemical fertilizers, particularly those containing phosphate, represent significant contributors to heavy metal accumulation in soils. Fertilizers produced from phosphate rock retain all heavy metals present in the original rock, including cadmium, lead, and arsenic [30]. Pesticides and wastewater irrigation further introduce metallic contaminants into agricultural systems [29].

Industrial Activities: Mining, smelting, manufacturing, and fossil fuel combustion release substantial quantities of toxic metals into the environment. Industrial discharges and atmospheric deposition facilitate the widespread distribution of these contaminants onto agricultural lands [29] [31].

Geogenic Sources: Igneous and sedimentary rocks naturally contain varying concentrations of heavy metals. For instance, basaltic igneous rocks contain 30-160 ppm of lead, while granitic igneous rocks contain 4-30 ppm [29]. Weathering processes slowly release these metals into soil systems.

Global Distribution Patterns

Cadmium has been identified as the most widespread toxic metal, with particularly high prevalence in South and East Asia, parts of the Middle East, and Africa [28]. A comprehensive assessment of Liaoning Province, China—a typical industrial and agricultural region—found cadmium to be a primary contaminant of concern, with 7.0% of soil samples exceeding standards [32]. Between 900 million and 1.4 billion people worldwide reside in areas considered high-risk for heavy metal exposure through agricultural products [28].

Table 1: Heavy Metal Concentration Ranges (ppm) in Various Rock Types [29]

| Metal | Basaltic Igneous | Granite Igneous | Shales and Clays | Black Shales | Sandstone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 0.006–0.6 | 0.003–0.18 | 0.0–11 | <0.3–8.4 | - |

| Pb | 30–160 | 4–30 | 18–120 | 20–200 | - |