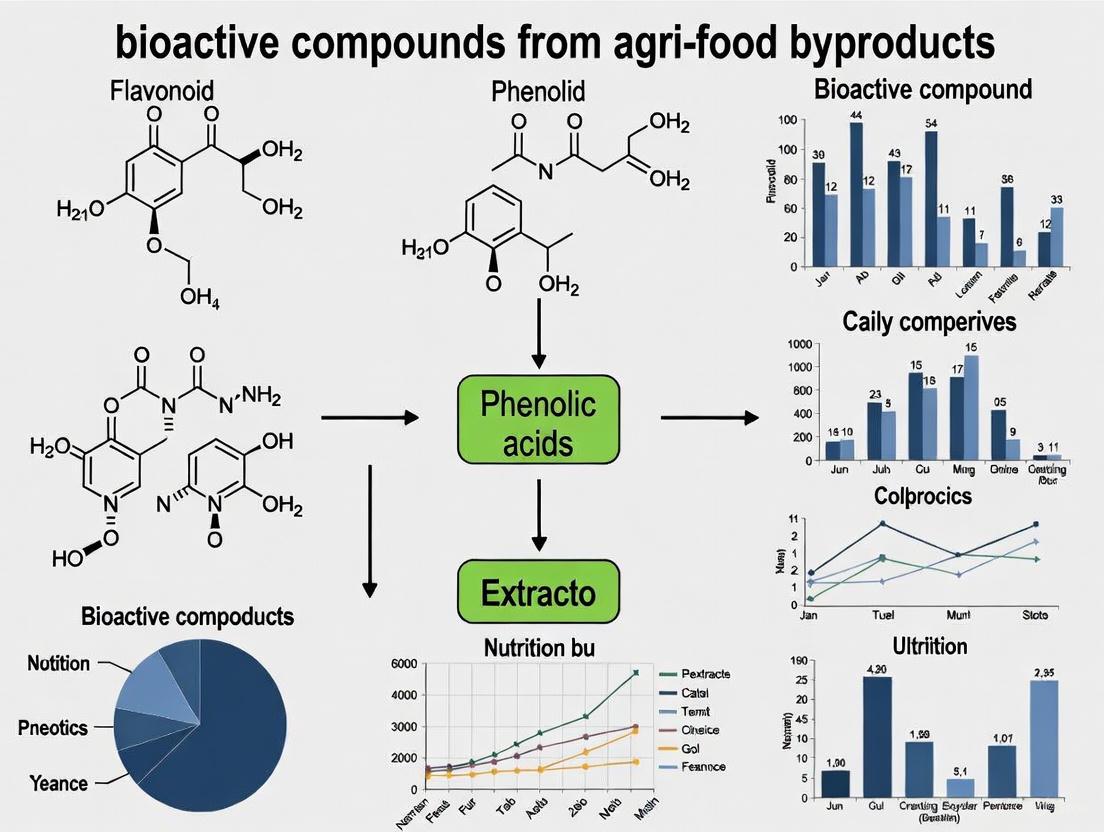

From Waste to Health: Unlocking the Biomedical Potential of Bioactive Compounds from Agri-Food Byproducts

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the valorization of agri-food waste as a sustainable source of bioactive compounds.

From Waste to Health: Unlocking the Biomedical Potential of Bioactive Compounds from Agri-Food Byproducts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the valorization of agri-food waste as a sustainable source of bioactive compounds. It explores the foundational science behind these compounds, details advanced and sustainable extraction methodologies, and addresses key challenges in optimization and scalability. The content critically evaluates the scientific validation of health benefits, with a specific focus on applications in nutraceuticals, functional foods, and pharmaceutical precursors, aligning with circular economy principles and offering novel avenues for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Hidden Treasure: Profiling Bioactive Compounds in Agri-Food Waste Streams

Agri-food waste (AFW) encompasses a diverse range of materials generated across the entire food supply chain, from agricultural production to final consumption [1]. These streams include agricultural residues, food processing by-products, and post-harvest losses, each contributing significantly to the global waste footprint while simultaneously representing rich, underutilized reservoirs of health-promoting phytochemicals [2] [3]. The valorization of AFW has gained substantial scientific and industrial momentum within the framework of circular bioeconomy principles, transforming these materials from disposal challenges into valuable feedstocks for bioactive compound recovery [4] [1].

The chemical composition of AFW makes it a natural reservoir of bioactive compounds with demonstrated health benefits, including polyphenols, carotenoids, bioactive peptides, and dietary fibers [2] [5]. Recent studies confirm that fruit and vegetable by-products, traditionally discarded, often contain similar or even higher concentrations of phytochemicals than their edible portions [2]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for defining, characterizing, and analyzing AFW, with particular emphasis on its potential as a source of bioactive compounds for nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and functional food applications targeted at researchers and drug development professionals.

Defining the Boundaries: Classification of Agri-Food Waste

Conceptual Framework and Terminology

Agri-food waste streams can be systematically categorized based on their origin within the food supply chain and their potential for valorization. The FOWCUS dataset provides a standardized classification system that aligns with FAOSTAT commodity typology, encompassing approximately 280 food commodities categorized into vegetables, fruits, nuts, eggs, livestock, seafood, cereals, sugar, vegetable oils, stimulants, pulses, and root vegetables [6]. This classification quantitatively captures the amounts of products and by-products that could potentially contribute to the generation of avoidable, potentially avoidable, and unavoidable food waste across the food supply chain [6].

Table 1: Classification of Agri-Food Waste by Origin and Composition

| Waste Category | Definition | Key Components | Bioactive Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues | Non-edible parts of crops left after harvest | Stalks, leaves, husks, stems [1] | Phenolic compounds, carotenoids [1] |

| Processing By-Products | Materials generated during food processing | Pomace, seeds, peels, brans [5] | Polyphenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins [2] |

| Post-Harvest Losses | Edible materials lost during handling/storage | Damaged or imperfect produce [1] | Similar profile to original produce [1] |

| Unavoidable Food Waste | Non-consumable waste streams | Animal bones, fruit pits, eggshells [6] | Minerals, structural polymers [6] |

Quantitative Assessment of AFW Composition

The FOWCUS dataset enables detailed mass balance calculations for food commodities, providing researchers with critical data for quantifying potential waste feedstocks. Through meticulous literature review and data standardization, this resource establishes mass balance equations where the total mass of each harvested food commodity is distributed among its various components, ensuring the summed mass percentages equal 100% [6]. This approach is essential for maintaining data integrity in waste management and valorization research applications.

Table 2: Representative Bioactive Compound Enrichment in Selected Agri-Food Wastes

| Agri-Food Waste Source | Key Bioactive Compounds | Comparative Content vs. Edible Portion | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kiwi Fruit Peel | Phenolic compounds, Tocopherol, Organic acids | Two times higher phenolics than pulp [5] | Antioxidant formulations, Functional foods |

| Tomato Pomace | Lycopene, Ellagic acid, Chlorogenic acid, Rutin | Lycopene: 447-510 µg/g DW (skin) [5] | Natural colorants, Lipid-protective ingredients |

| Olive Pomace | Hydroxytyrosol, Oleuropein, Maslinic acid | Hydroxytyrosol: 83.6 mg/100 g [5] | Anti-inflammatory formulations, Nutraceuticals |

| Grape Pomace | Anthocyanins, Resveratrol derivatives, Catechins | Similar or higher than whole fruit [2] [3] | Antioxidant, Cardioprotective applications |

Methodological Approaches: Extraction and Characterization of Bioactives from AFW

Green Extraction Technologies

Conventional extraction techniques like maceration and Soxhlet extraction are increasingly being replaced by green extraction methods that minimize environmental impact while improving efficiency and yield [3]. These advanced techniques include:

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Utilizes acoustic cavitation to enhance mass transfer and cell wall disruption, significantly reducing extraction time and solvent consumption [2] [3]. For example, UAE has been successfully applied to apple pomace for simultaneous extraction of dihydrochalcones, quercetin glycosides, and triterpenic acids [2].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Employs microwave energy to rapidly heat the solvent and plant matrix, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds [3].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Typically uses supercritical CO₂ as a non-toxic, tunable solvent for selective extraction of lipophilic compounds like carotenoids and essential oils [3].

- Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE): Operates at high temperatures and pressures to maintain solvents in liquid state, enhancing extraction efficiency [3].

- Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES): Emerging as sustainable, biodegradable solvent systems for polar phytochemicals [3].

Chromatographic Characterization and Profiling

The complex nature of AFW extracts necessitates advanced analytical techniques for comprehensive characterization. Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has become the technique of choice for unambiguous identification of target compounds and structural elucidation of novel molecules [4]. Complementary approaches include:

- Liquid chromatography with UV/Vis or fluorescence detection for profiling analytes such as proanthocyanins, curcuminoids, resveratrol derivatives, caffeic acids, and oleuropein [4].

- 1H-NMR spectroscopy for identifying primary and secondary metabolites, as demonstrated in the analysis of orange and lemon pomace extracts [2].

- Spectrophotometric assays for determining total antioxidant capacity through methods such as ORAC, FRAP, and DPPH [4].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Bioactive Compound Recovery from AFW

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AFW Bioactive Compound Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Green extraction media for polar phytochemicals | Recovery of polyphenols from olive pomace and citrus peels [3] |

| Enzyme Cocktails (Cellulase, Pectinase) | Cell wall degradation for improved compound release | Enzyme-assisted extraction of bound phenolics from cereal brans [2] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Extract clean-up and fractionation | Purification of anthocyanins from berry pomace before LC-MS analysis [4] |

| Chromatographic Standards | Compound identification and quantification | Quantification of hydroxytyrosol, oleuropein in olive waste extracts [5] |

| ORAC/FRAP/DPPH Reagents | Antioxidant capacity assessment | Standardized evaluation of extract bioactivity [4] |

| Cell Culture Assays | In vitro bioactivity validation | Testing anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-stimulated Caco-2 cells [2] |

Case Studies: Experimental Protocols for AFW Valorization

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction from Apple Pomace

Objective: To optimize the simultaneous extraction of dihydrochalcones, quercetin glycosides, and triterpenic acids from apple pomace using low-frequency ultrasound-assisted extraction [2].

Methodological Details:

- Raw Material Preparation: Apple pomace (peel, pulp, seeds, and stems) is dried at 40°C and milled to achieve uniform particle size (<2 mm).

- Extraction Protocol: The extraction is performed using ethanol-water mixtures (30-70% v/v) as solvent, with a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 to 1:30 (w/v). Ultrasound treatment is applied at frequencies of 20-40 kHz for 5-30 minutes at controlled temperature (25-60°C).

- Process Optimization: Response surface methodology (RSM) is employed to optimize critical parameters including solvent composition, ultrasound intensity, and extraction time.

- Analysis: Extract composition is analyzed by HPLC-DAD with quantification of phloridzin, quercetin glycosides, and ursolic acid. Antioxidant activity is determined using DPPH and FRAP assays [2].

Bioactivity Assessment of Citrus Pomace Extracts

Objective: To evaluate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of food-grade extracts from orange (OE) and lemon (LE) pomace for potential nutraceutical applications in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [2].

Methodological Details:

- Extract Preparation: Pomace is subjected to ultrasound-assisted maceration using food-grade ethanol. The extracts are concentrated under vacuum and lyophilized.

- Phytochemical Characterization: Major metabolites are identified using 1H-NMR and LC-DAD-ESI-MS. Key compounds include hesperidin (OE) and eriocitrin (LE).

- Bioaccessibility Assessment: In vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion is performed using the INFOGEST protocol, followed by analysis of recovered phenolic content.

- Cell-Based Assays: The intestinal bioaccessibility, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties are evaluated using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2). Parameters include protection against LPS-induced intestinal barrier disruption, oxidative stress (ROS generation), and inflammatory responses (IL-8 secretion) [2].

Diagram 2: Bioactive Compound Mechanisms and Applications from AFW

Agri-food waste represents a critical frontier in the sustainable discovery of bioactive compounds with significant health applications. The precise definition and characterization of AFW streams, coupled with advanced extraction and analytical methodologies, enables researchers to transform these underutilized resources into high-value products. The experimental approaches and technical frameworks outlined in this guide provide a foundation for systematic investigation of AFW bioactives, supporting drug development professionals in leveraging these materials for nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and functional food innovations. As circular bioeconomy principles continue to gain prominence, the valorization of AFW through scientifically rigorous methods will play an increasingly vital role in both sustainable resource management and health promotion.

The valorization of agri-food waste (AFW) represents a transformative approach to addressing global sustainability challenges while recovering high-value bioactive compounds for human health. A significant environmental burden, approximately 59 million tons of AFW are generated annually in Europe alone [7], with fruits and vegetables constituting the largest share at 45% of total food waste [7]. These by-products, often richer in bioactive compounds than edible portions [5], represent an underutilized reservoir of polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and bioactive peptides. The exploration of these compounds is increasingly driven by Sustainable Development Goal 12, which targets a 50% reduction in global food waste at retail and consumer levels by 2030 [8]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these key bioactive classes within the context of agri-food byproducts research, offering detailed methodologies and data frameworks for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of circular bioeconomy and health science applications.

Key Bioactive Classes in Agri-Food Byproducts

Polyphenols and Flavonoids

Polyphenols represent one of the most extensively studied bioactive classes in AFW, renowned for their antioxidant properties and role in modulating inflammation and various signal transduction pathways [2]. The PhInd database, the first comprehensive database dedicated to phenolics in agri-food by-products, reveals that fruit by-products constitute 73.2% of its entries, while vegetables, nuts, and cereals are significantly underrepresented at 5.5%, 6.4%, and 4.9% respectively [8]. This highlights a substantial research gap in non-fruit waste streams.

Table 1: Major Polyphenol and Flavonoid Sources in Agri-Food Byproducts

| Byproduct Source | Key Polyphenols/Flavonoids | Reported Concentration | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olive Pomace | Hydroxytyrosol, Oleuropein | Hydroxytyrosol: 83.6 mg/100 g; comprising 53.78% of total polyphenols [5] | Functional foods, cardioprotective supplements |

| Apple Pomace | Dihydrochalcones, Quercetin glycosides, Triterpenic acids | Profile enables prediction of antioxidant activity via multivariate models [2] | Antioxidant extracts, nutraceuticals |

| Grape Pomace (Winemaking) | Anthocyanins, Flavonols, Tannins | 23-32% increase in polyphenol content with combined UAE+PAE extraction [9] | Dietary supplements, natural colorants |

| Tomato Pomace | Rutin, Myricetin, Ellagic acid, Chlorogenic acid | Significant amounts in skin and seeds [5] | Anti-inflammatory formulations |

| Onion Peels | Flavonoids, Phenolic acids | TPC: 320 mg GAE/g; TFC: 80 mg QE/g (Soxhlet extraction) [9] | Antioxidant extracts, food preservatives |

Long-term consumption of polyphenol-rich diets confers protection against cancers, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and neurodegenerative conditions [2]. The solid-liquid extraction method remains predominant (53.5% of PhInd entries), primarily using water, ethanol, or aqueous ethanol (51.5% of entries) [8]. However, emerging green solvents like Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) represent a promising yet underutilized alternative (only 0.4% of entries) that warrants further investigation [8].

Carotenoids

Carotenoids are tetraterpenoid pigments extensively documented in AFW streams, particularly in fruit and vegetable processing byproducts. These compounds serve as potent antioxidants and vitamin A precursors, with applications spanning nutritional supplements, natural colorants, and functional foods [5].

Table 2: Major Carotenoid Sources in Agri-Food Byproducts

| Byproduct Source | Key Carotenoids | Reported Concentration | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato Pomace/Skin | Lycopene | 447-510 μg/g dry weight [5]; 1016.94 mg/100g extract via SC-CO₂ [9] | Antioxidant supplements, skincare products |

| Red Pepper Byproducts | Capsanthin, β-carotene | Retained stability under HPTT processing [10] | Natural colorants, provitamin A source |

| Carrot Processing Waste | β-carotene, α-carotene | Optimally recovered via supercritical CO₂ extraction [1] | Nutritional supplements, food fortification |

| Crustacean Shell Waste | Astaxanthin | Global availability: 6-8 million tons/year [5] | High-value nutraceuticals, aquaculture feeds |

Research indicates that High-Pressure Thermal Treatment (HPTT) at 600 MPa effectively stabilizes carotenoids in red pepper byproducts without significant degradation of total carotenoid content or antioxidant activity [10]. Supercritical CO₂ extraction has demonstrated superior efficacy for carotenoid recovery, yielding higher lycopene concentrations (1016.94 mg/100g extract) compared to conventional Soxhlet extraction [9].

Bioactive Peptides

Bioactive peptides are specific protein fragments that exert physiological benefits beyond basic nutrition, typically containing 2-20 amino acid residues [11]. These compounds remain inactive within parent protein sequences and require enzymatic hydrolysis for liberation and activation.

Table 3: Sources and Activities of Bioactive Peptides from Agri-Food Byproducts

| Protein Source | Bioactive Peptide Functions | Production Methods | Reported Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andean Crops (Quinoa, Maize, Cañihua, Tarwi) | Multifunctional peptides | Enzymatic hydrolysis, Fermentation | Antimicrobial, antitumoral, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, antioxidative [11] |

| Spent Brewer's Yeast | Protein hydrolysate encapsulation systems | Ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction with dextran or maltodextrin [2] | Enhanced antioxidant activity, improved bioactive compound stabilization |

| Oilseed Meals | Bioactive peptide precursors | Enzyme-assisted extraction, Solid-state fermentation [1] | ACE-inhibition, antioxidant, mineral binding |

| Cereal Bran Byproducts | Encrypted bioactive sequences | Microbial fermentation, Proteolytic extraction [1] | Antihypertensive, opioid-like, immunomodulatory |

Andean crops such as tarwi stand out for their exceptionally high protein content compared to other legumes, making them particularly promising sources of novel bioactive peptides [11]. The mechanisms of action for these peptides include surfactant properties, electrostatic interactions, enzyme inhibition, and receptor modulation [11]. Current research focuses on overcoming bioavailability challenges through in silico tools, peptide databases, and recombinant technologies to advance therapeutic applications [11].

Experimental Protocols for Bioactive Compound Research

High-Pressure Thermal Treatment (HPTT) Stabilization Protocol

Application: Stabilization of bioactive compounds in agri-food byproducts for enhanced shelf life and bioactivity preservation.

Materials: Red pepper byproducts, red wine pomace (Tempranillo variety), white wine pomace (Cayetana, Pardina, and Montúa varieties), heat-sealed packaging (low permeability polyamide/polyethylene bags) [10].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize byproducts using a crusher at maximum power until fine and homogeneous texture is achieved.

- Packaging: Portion 50g of red pepper or 40g of pomace samples into heat-sealed bags.

- HPTT Processing: Apply treatments at 600 MPa for 5 minutes at target temperatures of 65°C, 75°C, or 85°C.

- Control Setup: Compare against conventional thermal treatments (TT) at identical temperatures and duration without pressure.

- Analysis: Evaluate color parameters (L, a, b*), total phenolic content (TPC), total carotenoid content (TCC), and antioxidant activity (ABTS assay).

Notes: Adiabatic heating during HPTT increases actual temperature by approximately 18°C per 100 MPa, resulting in final temperatures of approximately 83°C, 93°C, and 103°C for the respective target temperatures [10]. This protocol effectively inactivates polyphenol oxidase (PPO), extending phenolic compound stability during storage.

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Polyphenols

Application: Efficient recovery of polyphenols from apple pomace and other fruit byproducts.

Materials: Apple pomace (peel, pulp, seeds, stems), ethanol-water solutions, ultrasonic bath with temperature control, response surface methodology (RSM) software [2].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry and mill apple pomace to uniform particle size.

- Experimental Design: Apply RSM to optimize extraction parameters including solvent concentration, solid-to-liquid ratio, temperature, and ultrasonic power.

- Extraction: Perform UAE using predetermined optimal conditions with frequency typically between 20-40 kHz.

- Filtration: Separate liquid extract from solid residue.

- Analysis: Quantify dihydrochalcones, quercetin glycosides, and triterpenic acids via HPLC. Assess total phenolic content and antioxidant activity.

- Model Validation: Develop multivariate regression models to predict antioxidant activity based on bioactive composition.

Notes: This method has demonstrated particular efficiency for simultaneous extraction of multiple antioxidant compounds from apple pomace, with optimized conditions enabling prediction of antioxidant activity through compositional data [2].

Encapsulation System Development Using Spent Yeast Hydrolysate

Application: Enhanced stabilization and delivery of anthocyanins from aronia pomace.

Materials: Spent brewer's yeast, dextran (D), maltodextrin (MD), aronia pomace anthocyanins, ultrasound probe [2].

Procedure:

- Protein Hydrolysate Production: Generate spent yeast protein hydrolysate (SYH) through enzymatic digestion.

- Maillard Conjugation: Combine SYH with dextran or maltodextrin via ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction.

- Conjugate Characterization: Assess antioxidant activity and structural properties of SYH:D and SYH:MD conjugates.

- Encapsulation: Employ freeze-drying to encapsulate aronia pomace anthocyanins using the conjugates as wall materials.

- Evaluation: Determine encapsulation efficiency, storage stability, and bioavailability during simulated gastrointestinal digestion.

Notes: The ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction enhances antioxidant activity compared to traditional heating. SYH:D conjugates demonstrate superior anthocyanin stability during storage, while SYH:MD with hydrolyzed yeast cell wall shows higher initial encapsulation efficiency [2].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Bioactive Compound Valorization Pathway

Figure 1: Comprehensive Valorization Pathway for Bioactive Compounds from Agri-Food Waste

Bioactive Compound Mechanisms of Action

Figure 2: Mechanisms of Action and Health Effects of Key Bioactive Compounds

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Green extraction solvent for polyphenols | Underutilized (only 0.4% of PhInd entries) with significant potential [8] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Non-polar compound extraction | Superior lycopene yield (1016.94 mg/100g) from tomato pomace [9] |

| Ethanol-Water Solutions | Conventional extraction solvent | 51.5% of polyphenol extraction in PhInd database; aqueous ethanol particularly effective [8] |

| Spent Yeast Protein Hydrolysate (SYH) | Encapsulation wall material | Maillard conjugates with dextran/maltodextrin for anthocyanin stabilization [2] |

| Dextran (D) & Maltodextrin (MD) | Carbohydrate carriers for encapsulation | SYH:D conjugates provide better storage stability; SYH:MD higher encapsulation efficiency [2] |

| Enzyme Cocktails | Bioactive peptide liberation | Proteolytic enzymes for protein hydrolysate production from various byproducts [11] |

| Cell Culture Models (Caco-2) | Bioavailability assessment | Evaluation of intestinal bioaccessibility and anti-inflammatory effects [2] |

The systematic recovery of polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and bioactive peptides from agri-food byproducts represents a strategic convergence of waste reduction and health promotion objectives. Current research demonstrates that fruit byproducts dominate investigation efforts (73.2% of PhInd database entries) [8], revealing significant opportunities for exploring vegetable, nut, and cereal waste streams. Advanced extraction technologies like HPTT [10] and combined UAE+PAE approaches [9] demonstrate enhanced efficiency in bioactive compound recovery while reducing energy consumption. Furthermore, encapsulation strategies utilizing novel materials like spent yeast hydrolysate conjugates [2] address critical challenges in compound stability and bioavailability. As research advances, focus must expand to include comprehensive toxicological profiling, regulatory framework development, and industrial scale-up of the most promising technologies to fully realize the potential of agri-food waste valorization in contributing to sustainable health solutions.

The global agri-food industry generates substantial quantities of byproducts, presenting significant environmental and economic challenges. However, these residues represent untapped reservoirs of bioactive compounds with immense potential for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and functional food applications. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of five prominent agri-food byproducts—citrus peels, olive pomace, apple pomace, cereal bran, and grape seeds—as sustainable sources of valuable phytochemicals. Within the context of a broader thesis on agri-food byproduct valorization, this review synthesizes current research on bioactive compound composition, advanced extraction methodologies, quantified bioactivity, and potential therapeutic mechanisms. The content is specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to transform waste streams into high-value health products, thereby contributing to circular bioeconomy models and sustainable resource management.

Compositional Analysis of Target Byproducts

The following table summarizes the key bioactive compounds and their concentrations across the five prominent byproduct sources, providing researchers with comparative quantitative data for source selection.

Table 1: Key Bioactive Compounds and Their Concentrations in Prominent Agri-Food Byproducts

| Byproduct Source | Key Bioactive Compounds | Reported Concentrations | Primary Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus Peels | Naringin, Hesperidin, Polymethoxyflavones (PMFs), D-Limonene | Total phenolics up to 49 mg/g (as flavonoid equivalents); Specific flavanones variable by species [12] [13] | α-Glucosidase & pancreatic lipase inhibition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [13] |

| Olive Pomace | Hydroxytyrosol, Tyrosol, Oleuropein, α-Tocopherol | Hydroxytyrosol: 83.6 mg/100 g; Tyrosol: 3.4 mg/100 g; α-Tocopherol: 2.63 mg/100 g [14] [15] | Antioxidant (strong DPPH/ABTS scavenging), AChE/BChE inhibition [14] [16] |

| Apple Pomace | Dietary Fiber, Phloretin, Quercetin glycosides, Chlorogenic acid | Total dietary fiber: 45–51%; Soluble fiber (Pectin): ~15% of dry weight [17] | Prebiotic, antioxidant, cholesterol-lowering, glycemic control [17] |

| Cereal Bran | Ferulic Acid, Arabinoxylans, β-Glucans, Alkylresorcinols | Phenolic acids: 0.7–2.7%; β-Glucans (Oat): 4.3–5.3%; Arabinoxylans (Wheat): 10.9–26.0% [18] [19] | Antioxidant, prebiotic, anti-inflammatory, anticancer [18] [19] |

| Grape Seeds | Proanthocyanidins (OPCs), γ-Tocotrienol, Linoleic Acid | α-Tocopherol: 844.4 ± 15.3 mg/kg (in PLE extract); OPCs variable by extraction method [20] | Potent antioxidant (ABTS/ORAC), anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective [20] [21] |

Advanced Extraction and Analytical Methodologies

Sustainable Extraction Technologies

Efficient recovery of bioactive compounds from complex byproduct matrices requires advanced extraction techniques that maximize yield, preserve bioactivity, and align with green chemistry principles.

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES): This method is highly effective for polar compounds like polyphenols. For citrus peels, optimal NaDES formulations include Choline Chloride:Tartaric acid (1:2) for grapefruit and lemon peels, and Choline Chloride:Glycerol (1:2) for lime peels, with 50% water content [12]. The ultrasound mechanism induces cavitation, disrupting cell walls and enhancing mass transfer. A typical protocol uses a probe sonicator (400 W, 20 kHz) for 30 minutes at room temperature with a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:4 [16].

Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE): PLE operates at elevated temperatures and pressures, maintaining solvents in a liquid state above their boiling points. This reduces solvent viscosity and improves penetration. For grape seeds, optimal conditions were 80°C and 67% ethanol, achieving high yields of α-tocopherol (844.4 mg/kg) and proanthocyanidins [20]. The process can be static (solvent remains in contact) or dynamic (continuous solvent renewal), with the latter minimizing thermal degradation [20].

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): SFE, particularly with CO₂, is ideal for lipophilic compounds. It offers high selectivity, minimal solvent residue, and low thermal degradation. SFE of citrus peels effectively recovers anticholinergic terpenoids, while for grape seeds, it provides a clean lipid fraction rich in linoleic acid [12] [20]. Sequential SFE followed by UAE-NaDES enables holistic exploitation, first targeting terpenoids and then polyphenols [12].

Experimental Workflow for Byproduct Valorization

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for the development of bioactive compounds from agri-food byproducts, from raw material preparation to final application.

Bioactivity Screening Protocols

Antioxidant Capacity Assays:

- DPPH Assay: Prepare a 0.1 mM DPPH methanolic solution. Mix 1 mL of extract with 2 mL of DPPH solution. Incubate for 30 minutes in darkness and measure absorbance at 517 nm. Calculate percentage inhibition relative to control [16].

- ABTS Assay: Generate ABTS•+ by reacting ABTS stock with potassium persulfate for 12-16 hours. Dilute to absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.020 at 734 nm. Mix 100 μL extract with 2.9 mL ABTS solution, incubate for 30 minutes, and measure absorbance [16].

- ORAC Assay: Measures antioxidant capacity to inhibit peroxyl radical-induced oxidation. Fluorescein is used as fluorescent probe, AAPH as peroxyl radical generator, and Trolox as standard [20].

Enzyme Inhibition Assays:

- α-Glucosidase/Pancreatic Lipase Inhibition: Critical for assessing anti-diabetic and anti-obesity potential. Pre-incubate enzyme with extract, add substrate (p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside for α-glucosidase; p-nitrophenyl acetate for lipase), and measure product formation at 405-410 nm [13].

- Cholinesterase Inhibition (AChE/BChE): Uses Ellman's method. Test extracts at various concentrations with acetylthiocholine/butyrylthiocholine as substrates. Monitor formation of 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate anion at 405 nm [16].

Bioactivity and Therapeutic Potential

Mechanisms of Action for Key Health Targets

The following diagram illustrates the primary molecular mechanisms through which bioactive compounds from the featured byproducts exert their reported health benefits, particularly focusing on metabolic and neurological targets.

Quantitative Bioactivity Data

The efficacy of byproduct extracts is quantitatively assessed through standardized assays, providing researchers with comparable data for evaluating potential applications.

Table 2: Quantitative Bioactivity Profiles of Byproduct Extracts

| Byproduct Source | Antioxidant Activity | Enzyme Inhibition Activity | Other Notable Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus Peels | Variable by extraction method & citrus variety [12] | Significant α-glucosidase & pancreatic lipase inhibition [13] | Anticholinergic activity of SC-CO2 extracts [12] |

| Olive Pomace | Strong DPPH & ABTS radical scavenging; Reflux extracts most potent [16] | AChE inhibition up to 83.21% at 500 µg/mL [16] | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory [15] |

| Apple Pomace | Correlated with polyphenol content [17] | Not specifically quantified | Prebiotic effect from dietary fibers [17] |

| Cereal Bran | Ferulic acid & arabinoxylans are primary contributors [19] | Linked to phenolic acid content | Cholesterol-lowering (β-glucans), anticancer [18] |

| Grape Seeds | PLE extracts showed strong ABTS & ORAC activity [20] | Not specifically quantified | Sunflower oil oxidation induction period extended (comparable to BHA) [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential reagents, solvents, and materials required for experimental work with agri-food byproducts, serving as a reference for laboratory setup and protocol development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Byproduct Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) | Green extraction of polar bioactive compounds | Choline Chloride:Tartaric acid (1:2); Choline Chloride:Glycerol (1:2); with 50% water [12] |

| Food-Grade Ethanol | Primary solvent for phenolic compound extraction | 70-100% concentration; used in reflux, maceration, PLE [20] [16] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Solvent for lipophilic compound extraction | Technical grade; used with modifiers like ethanol [12] [20] |

| DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Free radical for antioxidant capacity assessment | 0.1 mM solution in methanol; measure absorbance at 517 nm [16] |

| ABTS (2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Radical cation for antioxidant capacity assessment | Generated with potassium persulfate; measure absorbance at 734 nm [16] |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Screening for inhibitory activity | α-Glucosidase, pancreatic lipase, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [13] [16] |

| Chromatography Standards | Compound identification and quantification | Phenolic acids, flavonoids, tocopherols, proanthocyanidins [14] [20] |

Agri-food byproducts represent a promising and sustainable source of diverse bioactive compounds with significant potential for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical development. The compositional and bioactivity data presented in this whitepaper demonstrate that citrus peels, olive pomace, apple pomace, cereal bran, and grape seeds contain substantial quantities of valuable phytochemicals with demonstrated health benefits. Advanced extraction technologies—including UAE-NaDES, PLE, and SFE—enable efficient, sustainable recovery of these compounds. The documented bioactivities, particularly regarding metabolic syndrome targets and neurological health, provide a strong scientific foundation for further research and development. Future work should focus on standardization of extracts, clinical validation of efficacy, and development of scalable purification processes to fully realize the potential of these resources in value-added applications.

The valorization of agri-food by-products represents a paradigm shift in sustainable health science, transforming residual biomass into rich sources of bioactive compounds. With the global agri-food system generating approximately 11 billion tonnes of food annually—a significant portion of which becomes waste—these by-products constitute an untapped reservoir of phytochemicals and bioactive molecules [22]. Research conducted between 2020 and 2025 has rapidly advanced our understanding of these compounds, particularly their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective properties [23]. This technical overview synthesizes current scientific evidence on the health benefits of bioactives derived from agri-food by-products, focusing on their molecular mechanisms, experimental assessment methodologies, and potential applications in functional foods and preventive medicine for a research audience.

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Antioxidant Pathways and Oxidative Stress Mitigation

Bioactive compounds from agri-food by-products exert antioxidant effects primarily through direct free radical neutralization and enhancement of endogenous defense systems. Free radicals, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), are highly reactive molecules with unpaired electrons that cause oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA when their production overwhelms endogenous antioxidant defenses [24].

The fundamental antioxidant mechanisms include:

- Direct Free Radical Scavenging: Phytochemicals donate hydrogen atoms or electrons to stabilize free radicals, terminating chain reactions of oxidative damage [24].

- Metal Ion Chelation: Compounds such as phenolics bind pro-oxidant transition metals like iron and copper, preventing their participation in Fenton reactions that generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals [25].

- Enzymatic Antioxidant Enhancement: Bioactives activate the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway, leading to increased expression of antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [26].

The Nrf2-mediated pathway represents a crucial mechanism for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis, as depicted below:

Figure 1: Nrf2/ARE Pathway for Antioxidant Defense

Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Bioactives from agri-food by-products modulate inflammation through multiple molecular targets, with particular efficacy in suppressing NF-κB signaling—a primary pathway governing pro-inflammatory gene expression [25]. Key anti-inflammatory mechanisms include:

- NF-κB Pathway Inhibition: Prevention of IκB phosphorylation and degradation, thereby retaining NF-κB in the cytoplasm and reducing transcription of pro-inflammatory genes including TNF-α, IL-6, and COX-2 [25].

- NLRP3 Inflammasome Suppression: Inhibition of inflammasome assembly and subsequent caspase-1 activation, reducing maturation and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 [27].

- PPARγ Activation: Ligand-dependent transactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, resulting in transrepression of NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways [27].

The interplay between these pathways is visualized below:

Figure 2: Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms of Bioactive Compounds

Integrated Cardioprotective Actions

The cardioprotective benefits of bioactives from agri-food by-products emerge from the convergence of their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, with additional targeted effects on cardiovascular tissues [25] [28]. These compounds mitigate multiple pathophysiological processes in cardiovascular diseases:

- Endothelial Protection: Reduction of oxidative stress in vascular endothelium increases nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, improving vasodilation and reducing endothelial adhesion molecule expression [25].

- Mitochondrial Preservation: In cardiomyocytes, bioactives stabilize mitochondrial membranes, prevent permeability transition pore opening, and enhance electron transport chain efficiency, reducing ROS generation and apoptotic signaling [26].

- Anti-fibrotic Activity: Suppression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling in cardiac fibroblasts reduces differentiation into myofibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition, preventing pathological stiffening of myocardial tissue [26] [28].

- Macrophage Phenotype Modulation: Reprogramming of macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory phenotypes reduces foam cell formation and atherosclerotic plaque progression [26].

Major Bioactive Classes from Agri-food By-products

Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds represent one of the most abundant and diverse classes of bioactive molecules in agri-food by-products, with over 8,000 identified structures [22]. These compounds contain aromatic rings with hydroxyl groups and are categorized into several subclasses:

- Phenolic Acids: Hydroxybenzoic and hydroxycinnamic acids from fruit peels, cereal brans, and vegetable processing wastes [23].

- Flavonoids: Flavonols, flavones, flavan-3-ols, anthocyanidins, and isoflavones from grape pomace, apple peels, onion skins, and citrus rinds [25].

- Lignans: Found in cereal brans and seed coats [25].

- Tannins: Hydrolyzable and condensed tannins from grape seeds, tree barks, and fruit skins [22].

Terpenoids and Carotenoids

Terpenoids constitute one of the largest families of plant secondary metabolites, built from isoprene units and classified by the number of these units [22]:

- Monoterpenes (C10): D-limonene from citrus peels demonstrates antibacterial effects [22].

- Sesquiterpenes (C15): Found in essential oils from various fruit and vegetable processing wastes [22].

- Diterpenes (C20): Carnosic acid from rosemary by-products exhibits potent antioxidant activity [22].

- Tetraterpenes (C40): Carotenoids including lycopene from tomato peels and β-carotene from carrot pomace function as antioxidants and natural pigments [23] [22].

Alkaloids and Phytosterols

- Alkaloids: Nitrogen-containing compounds such as berberine from various plant processing by-products demonstrate lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory properties [25].

- Phytosterols: Plant sterols from cereal germ, nut shells, and vegetable oil processing wastes compete with dietary cholesterol for absorption, reducing serum LDL-cholesterol [25].

Table 1: Major Bioactive Compounds from Agri-food By-products and Their Effects

| Bioactive Class | Specific Examples | Prominent By-product Sources | Primary Demonstrated Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, Phenolic acids | Grape pomace, apple peels, citrus rinds, olive mill waste | ROS scavenging, NF-κB inhibition, NO bioavailability enhancement [23] [25] |

| Terpenoids | D-limonene, Lycopene, Carnosic acid | Citrus peels, tomato skins, rosemary leaves | Antioxidant, membrane stabilization, reduced lipid peroxidation [22] |

| Alkaloids | Berberine | Various medicinal plant processing wastes | LDL-receptor upregulation, anti-inflammatory signaling [25] |

| Phytosterols | β-sitosterol, Campesterol | Cereal germ, nut shells, vegetable oil wastes | Cholesterol absorption competition, LDL reduction [25] |

| Dietary Fibers | Inulin, β-glucans, Pectin | Fruit pomace, vegetable processing wastes | SCFA production, gut microbiota modulation, inflammatory marker reduction [29] |

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

In Vitro Antioxidant Activity Assays

Standardized methodologies for evaluating antioxidant capacity of extracts from agri-food by-products include:

- DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay: Measures hydrogen-donating capacity by monitoring discoloration of DPPH solution at 517nm [22].

- ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity): Quantifies antioxidant activity against peroxyl radicals generated by AAPH decomposition [22].

- FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power): Assesses reduction of ferric-tripyridyltriazine complex to colored ferrous form at 593nm [22].

- TEAC (Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity): Evaluates ability to scavenge ABTS⁺ radical cation, measuring absorbance at 734nm [22].

- Cellular Antioxidant Activity (CAA): Utilizes dichlorofluorescin-diacetate in cultured cells to measure intracellular ROS scavenging [25].

Anti-inflammatory Activity Assessment

- Cell-Based Inflammation Models: LPS-stimulated macrophages (RAW 264.7, THP-1) measuring NO production, prostaglandin E₂, and cytokine secretion (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) via ELISA [25].

- Protein Expression Analysis: Western blotting for NF-κB pathway components (IκBα, p65 phosphorylation), COX-2, and iNOS [25].

- Gene Expression Profiling: qRT-PCR quantification of inflammatory mediator mRNA levels [25].

- Enzymatic Activity Assays: Direct inhibition testing against COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX, and phospholipase A₂ [25].

Cardioprotective Efficacy Evaluation

- In Vitro Cardiovascular Models:

- Ex Vivo Systems: Isolated heart preparations (Langendorff) assessing ischemia-reperfusion injury [26].

- In Vivo Models:

- Clinical Biomarkers: LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, hs-CRP, blood pressure, flow-mediated dilation [25].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Bioactives from Agri-food By-products on Cardiovascular Parameters

| Bioactive Source | Experimental Model | Key Outcomes | Magnitude of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grape Pomace Polyphenols | Human clinical trial (coronary artery disease) | Reduced inflammatory markers | Significant decrease in IL-6, TNF-α [25] |

| Coffee Pulp Extract | In vitro (cellular models) | Anti-diabetic properties | Improved glucose metabolism [23] |

| Fermented Kefir + Prebiotic | Human clinical trial (6-week intervention) | Reduced systemic inflammation | IL-6: d=-0.882; IFN-γ: d=-0.940 [29] |

| Cocoa Flavonoids | Human clinical trial | Lipid profile improvement | Increased HDL, decreased oxidized LDL [25] |

| Oat Flour & Husks | In vitro characterization | Bioactive compound source | Rich in phenolic compounds [23] |

| Tomato Peel Lycopene | In vitro assays | Antioxidant activity | Effective free radical scavenging [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function/Utility |

|---|---|---|

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Antioxidant capacity assessment | Stable free radical for scavenging assays [22] |

| ABTS⁺ (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Antioxidant activity measurement | Radical cation for TEAC assay [22] |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | Inflammation induction in cellular models | TLR4 agonist for stimulating inflammatory responses [25] |

| AAPH (2,2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride) | ORAC assay | Peroxyl radical generator [22] |

| DCFH-DA (Dichlorofluorescin diacetate) | Cellular ROS measurement | Fluorescent probe for intracellular oxidative stress [25] |

| ELISA Kits (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) | Cytokine quantification | Quantitative measurement of inflammatory mediators [25] [29] |

| Olink Target 96 Panel | Multiplex inflammatory protein profiling | Simultaneous measurement of 92 inflammation-related proteins [29] |

| Primary Cells (HUVEC, cardiomyocytes) | Cardiovascular protection studies | Physiologically relevant models for mechanism studies [26] |

Extraction and Enhancement Methodologies

Sustainable Extraction Technologies

Advanced extraction methods optimize recovery of bioactive compounds from agri-food by-products while maintaining sustainability:

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Utilizes cavitation forces to disrupt plant cell walls, enhancing solvent penetration and compound release [23].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Electromagnetic energy rapidly heats internal water molecules, creating pressure that ruptures cells [23].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Typically uses CO₂ under supercritical conditions for efficient, non-toxic compound isolation [23].

- Enzyme-Assisted Extraction: Cell wall-degrading enzymes (cellulase, pectinase) break down structural polysaccharides to release bound phenolics [22].

Fermentation-Enhanced Bioactivity

Fermentation represents a powerful biotechnology for enhancing the bioactive profile of agri-food by-products [30]. Microbial transformation during fermentation:

- Increases bioavailability of bound phenolics through enzymatic hydrolysis [30].

- Generates novel bioactive metabolites with enhanced biological activities [30].

- Produces cardioprotective compounds including bioactive peptides, GABA, and monacolin K [30].

- Improves sensory properties of final products, facilitating consumer acceptance [30].

The experimental workflow for developing fermented bioactive ingredients is summarized below:

Figure 3: Fermentation-Based Bioactive Ingredient Development

Agri-food by-products represent valuable sources of bioactive compounds with demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective properties. Through defined molecular mechanisms including Nrf2 activation, NF-κB inhibition, and specific cardiovascular tissue effects, these compounds offer multi-targeted approaches to preventing and mitigating chronic diseases. Standardized in vitro and in vivo methodologies enable systematic evaluation of their efficacy, while advanced extraction and fermentation technologies enhance their bioavailability and functionality. The strategic valorization of these underutilized resources aligns with circular economy principles while contributing to sustainable health promotion strategies. Future research should focus on human clinical trials, personalized nutrition applications, and scaling sustainable production methods to bridge the gap between laboratory evidence and practical health solutions.

The valorization of agri-food waste (AFW) represents a transformative approach to addressing pressing global sustainability challenges. With approximately 1.3 billion tons of food wasted annually worldwide, the environmental and economic implications are substantial [31]. This waste contributes significantly to environmental degradation while simultaneously representing a vast reservoir of untapped value in the form of bioactive compounds [1]. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a critical framework for addressing these challenges, particularly through Goal 2: Zero Hunger, Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being, Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, and Goal 13: Climate Action [32] [33].

The integration of AFW valorization within the SDG framework offers a dual-pronged solution: reducing the environmental footprint of the agri-food sector while creating new economic opportunities through the extraction of high-value bioactive compounds. These compounds, including polyphenols, carotenoids, dietary fibers, and bioactive peptides, exhibit demonstrated health-promoting properties with applications in functional foods, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals [1] [34]. This alignment creates a powerful synergy between environmental stewardship, economic development, and human health advancement, forming a cornerstone of the circular bioeconomy model essential for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [35] [31].

Bioactive Compounds in Agri-Food Byproducts: Composition and Health Applications

Agri-food byproducts are rich sources of diverse bioactive compounds with significant health-promoting properties. These secondary metabolites, produced by plants for defense and adaptation, reveal a wide range of biological activities beneficial to human health [34]. The composition and concentration of these compounds vary considerably across different waste streams, reflecting the varied compositions of fruits, vegetables, grains, and other agricultural products [1].

Table 1: Major Bioactive Compounds in Selected Agri-Food Byproducts and Their Health Applications

| Byproduct Source | Bioactive Compounds | Concentration | Health Applications | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pomegranate Peel | Punicalagins (ellagitannin), Ellagic Acid, Gallic Acid | 505.89 mg/g dry weight (punicalagins) [34] | Antioxidant, Anticancer, Cardioprotective | In vitro studies showing high antioxidant capacity [34] |

| Apple Pomace | Procyanidin B2, Chlorogenic Acid, Phlorizin, Quercetin | 92.62 mg/kg dry weight (procyanidin B2) [34] | Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory, Antidiabetic | Compositional analysis and in vitro assays [34] |

| Citrus Peels | D-limonene, Hesperidin, Dietary Fibers | 64% total dietary fiber [34] | Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Digestive Health | Clinical and observational studies [34] [36] |

| Avocado Seed & Peel | Phenolic Compounds, Catechin, Procyanidins | Up to 64 distinct phenolics identified [36] | Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory, Cardioprotective | Clinical trials showing improved lipid profiles [36] |

| Broccoli Byproducts | Glucoraphanin, Glucosinolates | 32-64% of total glucosinolates [34] | Anticancer, Detoxification Support | Cell line studies and compositional analysis [34] |

| Grape Pomace | Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, Tannins | Varies by cultivar and extraction method | Antioxidant, Cardioprotective, Prebiotic | Incorporated into functional foods [34] |

The health-promoting effects of these bioactive compounds form a scientific basis for their application in preventive healthcare and functional product development. Regular consumption of these compounds is linked to the prevention of chronic, degenerative, and metabolic diseases [31]. Polyphenols, one of the most studied groups, exhibit multifaceted biological activities including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and cardioprotective effects [35]. For instance, the phenolic compounds in avocado have been recognized for their role in attenuating oxidative stress and modulating inflammatory pathways [36].

Sustainable Extraction Technologies: Methodologies and Protocols

The efficient extraction of bioactive compounds from agri-food byproducts is crucial for their utilization in various applications. Traditional methods like maceration and Soxhlet extraction have limitations including high solvent consumption, lengthy processing times, and potential degradation of heat-sensitive compounds [31] [9]. Advanced green extraction technologies have emerged as sustainable alternatives that enhance efficiency while reducing environmental impact.

Green Extraction Techniques

Table 2: Comparison of Green Extraction Technologies for Bioactive Compounds from Agri-Food Byproducts

| Extraction Technique | Mechanism of Action | Optimal Parameters | Advantages | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Cavitation, Cell disruption | 25-60°C, 5-60 min, Low-frequency waves [34] [31] | Reduced time, Low temperature, High efficiency | Equipment cost, Scale-up challenges | Polyphenols, Flavonoids [31] |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Dielectric heating, Ionic conduction | 100-150°C, Solvent selection critical [1] | Rapid heating, Reduced solvent use | Non-uniform heating, Safety concerns | Thermostable compounds [9] |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Supercritical CO₂ as solvent | 31.1°C, 73.8 bar, Co-solvents for polarity [1] | Solvent-free, High selectivity, Tunable | High equipment cost, Pressure dependence | Lipids, Essential oils [9] |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) | Cell wall degradation | 30-60°C, Enzyme selection key [1] | Mild conditions, Specificity | Enzyme cost, Longer times | Bound phenolics, Fibers [1] |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Hydrogen bond formation | Customizable for target compounds [1] | Biodegradable, Low toxicity, Tunable | High viscosity, Recovery challenges | Polar compounds [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Polyphenols from Fruit Peels

Principle: UAE utilizes ultrasonic waves to create cavitation bubbles that disrupt plant cell walls, enhancing the release of intracellular compounds into the extraction solvent [34].

Materials and Equipment:

- Ultrasonic bath or probe system (frequency: 20-40 kHz)

- Dried and powdered plant material (e.g., pomegranate peel, apple pomace)

- Hydroalcoholic solvent (e.g., ethanol-water mixture, 50:50 v/v)

- Filtration unit (Whatman filter paper or equivalent)

- Rotary evaporator for solvent removal

- Analytical equipment for quantification (HPLC, spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry byproducts at 40°C until constant weight, then grind to particle size of 0.5-1.0 mm.

- Extraction: Mix plant material with solvent at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 to 1:30 (w/v) in extraction vessel.

- Sonication: Process the mixture at controlled temperature (25-60°C) for 5-60 minutes with ultrasonic power density of 50-500 W/L.

- Separation: Separate the liquid extract from the solid residue by filtration or centrifugation (3000-5000 × g for 10 minutes).

- Concentration: Remove solvent under reduced pressure at 40°C using a rotary evaporator.

- Analysis: Quantify total phenolic content using Folin-Ciocalteu method and identify individual compounds by HPLC-DAD or LC-MS.

Optimization Notes: Key parameters affecting yield include ultrasonic power, temperature, time, solvent composition, and solid-to-liquid ratio. Response surface methodology (RSM) is recommended for optimization [34] [31].

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) for Carotenoids from Tomato Processing Waste

Principle: SFE uses supercritical CO₂ (scCO₂) as a solvent, which has liquid-like density and gas-like diffusivity, enabling efficient penetration into plant matrices and extraction of non-polar compounds [9].

Materials and Equipment:

- SFE system with CO₂ pump, extraction vessel, pressure and temperature controllers, and separator

- Liquid CO₂ source (food grade)

- Co-solvent (e.g., ethanol) and delivery pump

- Raw material (tomato peels and seeds, dried and ground)

- Analytical equipment for carotenoid quantification

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry tomato processing waste (peels and seeds) and grind to particle size of 0.2-0.5 mm. Moisture content should be below 10%.

- System Preparation: Pack the extraction vessel with plant material, avoiding channeling. Preheat the system to the desired temperature (40-80°C).

- Extraction: Pressurize the system with CO₂ to the working pressure (200-400 bar). For carotenoids, higher pressures (300-400 bar) are typically more effective.

- Co-solvent Addition: For enhanced extraction of more polar carotenoids, add 5-15% ethanol as co-solvent.

- Dynamic Extraction: Maintain CO₂ flow rate of 1-3 kg/h for 1-3 hours, depending on sample size.

- Separation: Collect the extract by reducing pressure in the separation vessel, causing CO₂ to vaporize and the extract to precipitate.

- Analysis: Dissolve the extract in organic solvent and analyze by spectrophotometry (for total carotenoids) or HPLC (for individual carotenoids).

Optimization Notes: Temperature, pressure, CO₂ flow rate, extraction time, and co-solvent percentage significantly impact yield. The modifier choice is particularly important for more polar compounds [9].

Sustainable Development Goal Alignment and Impact Assessment

The valorization of agri-food byproducts directly contributes to multiple SDGs, creating a synergistic relationship between waste management, economic development, and environmental protection.

Primary SDG Alignment

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production is centrally addressed through AFW valorization. The conversion of waste streams into valuable bioactive compounds epitomizes sustainable production patterns and contributes to substantially reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse by 2030 [32] [33]. The adoption of green extraction technologies further aligns with target 12.4 regarding environmentally sound management of chemicals and wastes.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being is advanced through the development of nutraceuticals and functional foods containing bioactive compounds with demonstrated health benefits. The preventive health potential of these compounds contributes to reducing premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (target 3.4) and supports research and development of medicines for communicable and non-communicable diseases (target 3.b) [37].

SDG 2: Zero Hunger is supported through sustainable food production systems and improved nutrition. The valorization of AFW contributes to increased agricultural productivity (target 2.3) and the implementation of resilient agricultural practices that maintain ecosystems (target 2.4) [37]. Additionally, bioactive compounds such as dietary fibers and prebiotics can improve nutritional outcomes.

SDG 13: Climate Action is addressed through reduced greenhouse gas emissions from landfills and decreased reliance on energy-intensive waste processing methods. The carbon footprint reduction achieved through AFW valorization contributes to mitigating climate impacts and integrating climate change measures into national policies (target 13.2) [1].

Quantitative Impact Assessment

Table 3: SDG Impact Metrics of Agri-Food Byproduct Valorization

| SDG | Key Performance Indicators | Impact Level | Measurement Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 12 | Waste reduction rate, Resource efficiency, Recycling rate | Direct, High Impact | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Material Flow Analysis [1] |

| SDG 3 | Bioavailability of compounds, Health claim validation, Disease reduction | Direct, Medium-High Impact | Clinical trials, Epidemiological studies [35] |

| SDG 2 | Reduction in food losses, Nutritional enhancement | Indirect, Medium Impact | Food loss accounting, Nutritional analysis [32] |

| SDG 13 | GHG emission reduction, Carbon footprint | Direct, Medium Impact | Carbon accounting, LCA [1] |

| SDG 9 | Innovation in extraction technologies, Value-added products | Direct, Medium Impact | Patent analysis, R&D investment tracking [31] |

| SDG 17 | Multi-stakeholder partnerships, Knowledge sharing | Enabling, Variable | Partnership analysis, Publication metrics [1] |

Advanced Applications: Nanoencapsulation and Delivery Systems

The bioavailability and stability of bioactive compounds from agri-food byproducts can be limited by factors such as poor solubility, chemical instability, and rapid metabolism. Nanoencapsulation technologies address these challenges by protecting delicate compounds and enhancing their delivery.

Nanoencapsulation Techniques

Spray Drying: This widely used technique involves atomizing a bioactive-containing feed solution into a hot drying medium, resulting in rapid solvent evaporation and formation of dried particles. A comparative study demonstrated that spray-drying achieved higher encapsulation efficiency (98.83%) than freeze-drying for ciriguela peel extracts using gum arabic and maltodextrin as wall materials [9].

Freeze Drying: Also known as lyophilization, this method involves freezing the bioactive solution and removing water by sublimation under vacuum. While more energy-intensive than spray-drying, it better preserves heat-sensitive compounds.

Electrospinning and Electrospraying: These techniques use electrical forces to produce fibers or particles at the micro- and nano-scale, offering high encapsulation efficiency and controlled release properties.

Liposome Encapsulation: This method creates phospholipid bilayers that encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds, enhancing bioavailability and targeted delivery.

Experimental Protocol: Nanoencapsulation of Polyphenols by Spray Drying

Principle: Spray drying transforms liquid feeds into dry powders through atomization and rapid drying, trapping bioactive compounds within a wall matrix that protects against degradation [9].

Materials and Equipment:

- Spray dryer with nozzle atomization

- Wall materials (maltodextrin, gum arabic, modified starch)

- Bioactive extract from agri-food byproducts

- Solvent (water, ethanol)

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, spectrophotometer, particle size analyzer)

Procedure:

- Feed Preparation: Dissolve wall material (20-30% w/v) in appropriate solvent with stirring and heating if necessary.

- Bioactive Incorporation: Add bioactive extract to the wall material solution at appropriate ratio (typically 1:4 to 1:10 core-to-wall ratio) and homogenize.

- Atomization and Drying: Feed the solution into the spray dryer at controlled flow rate (5-15 mL/min). Set inlet temperature at 120-180°C and outlet temperature at 60-90°C, depending on the thermal sensitivity of the compounds.

- Powder Collection: Collect the dried powder from the collection chamber and store in airtight containers with desiccant.

- Characterization: Determine encapsulation efficiency by measuring surface vs. total bioactive content, particle size distribution, moisture content, and morphology.

Optimization Notes: Key parameters affecting encapsulation efficiency include inlet/outlet temperatures, feed flow rate, core-to-wall ratio, and wall material composition. Maltodextrin with dextrose equivalent of 10-20 often provides good retention of polyphenols [9].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specification Guidelines | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green extraction solvent | Custom formulations (e.g., choline chloride:urea, 1:2 molar ratio) | Polyphenol extraction [1] |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Supercritical fluid extraction | Food grade, 99.9% purity | Lipid-soluble compound extraction [9] |

| Maltodextrin | Encapsulation wall material | DE 10-20 for optimal retention | Spray drying of heat-sensitive compounds [9] |

| Enzyme Cocktails | Cell wall degradation | Pectinase, cellulase, hemicellulase mixtures | Enzyme-assisted extraction [1] |

| Chromatography Standards | Compound identification and quantification | HPLC grade, ≥95% purity | Quantification of specific bioactive compounds [34] |

| Cell Culture Assays | Bioactivity assessment | Human cell lines (Caco-2, HepG2) | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory activity [35] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Total phenolic content assay | Commercial reagent following standardized protocol | Rapid screening of phenolic compounds [34] |

| ORAC Assay Kit | Antioxidant capacity measurement | Commercially available kits with fluorescein | Standardized antioxidant measurement [35] |

Visualization of Research Workflows

Agri-Food Byproduct Valorization Pathway

Integrated Extraction and Encapsulation Workflow

The valorization of agri-food byproducts represents a strategic imperative that aligns economic and environmental objectives with the broader UN Sustainable Development Goals. The integration of advanced extraction technologies, particularly green methods such as ultrasound-assisted and supercritical fluid extraction, enables the efficient recovery of valuable bioactive compounds while minimizing environmental impact. These technologies, coupled with innovative delivery systems like nanoencapsulation, transform waste streams into high-value products with demonstrated health benefits, creating new economic opportunities in the nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and functional food sectors.

The alignment with SDGs 2, 3, 12, and 13 creates a synergistic framework that addresses multiple sustainability challenges simultaneously. This approach contributes to waste reduction, resource efficiency, climate action, and improved human health through enhanced nutrition and disease prevention. As research advances, focusing on scalability, bioavailability enhancement, and clinical validation will be crucial for maximizing the impact of agri-food byproduct valorization. The continued development of this field offers a promising pathway toward achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development while fostering innovation and economic resilience in the bioeconomy sector.

Green Extraction and Biomedical Translation: From Lab to Application

The valorization of agri-food byproducts represents a cornerstone of the circular economy, transforming waste into valuable resources of bioactive compounds for nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and functional food applications [2]. Efficient extraction is critical, as conventional methods like Soxhlet and maceration are often inefficient, time-consuming, and require large volumes of solvents, potentially degrading heat-sensitive compounds [38] [39]. To overcome these limitations, advanced, sustainable extraction techniques have been developed.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to five key advanced extraction technologies: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE), and Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE). Framed within bioactive compound research from agri-food byproducts, it details their fundamental principles, optimized methodologies, and comparative performance, serving as a comprehensive resource for researchers and industry professionals.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) utilizes high-frequency sound waves to generate acoustic cavitation. The formation, growth, and implosive collapse of microscopic bubbles in the solvent create localized extremes of temperature and pressure, disrupting plant cell walls and enhancing mass transfer of target compounds into the solvent [38] [40].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) employs microwave energy to heat the solvent and plant material volumetrically through dielectric heating. This rapid and direct heating of moisture within cells creates high internal pressure, effectively rupturing cell structures and significantly accelerating the diffusion of bioactive compounds into the surrounding solvent [38] [41].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) most commonly uses carbon dioxide (CO₂) heated and pressurized beyond its critical point (31.1°C, 73.8 bar). In this supercritical state, CO₂ possesses a gas-like diffusivity and viscosity, allowing deep penetration into matrices, and a liquid-like density, enabling efficient solvation. Its solvating power is highly tunable by adjusting temperature and pressure, allowing for selective extraction [42].

- Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) is a non-thermal method that uses specific enzymes (e.g., pectinases, cellulases, hemicellulases) to catalyze the hydrolysis of structural cell wall components (pectin, cellulose, hemicellulose) and storage polymers (starch, proteins). This degradation breaks down the rigid cell wall structure, facilitating the release of bound intracellular compounds [43].

- Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE), also known as Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE), operates with solvents at elevated temperatures (50–200°C) and high pressures (10–15 MPa). These conditions maintain the solvent in a liquid state above its normal boiling point, which decreases its viscosity and surface tension, thereby enhancing its ability to penetrate the sample matrix and improving the dissolution kinetics of the target analytes [44].

The following table provides a consolidated quantitative and technical comparison of the five advanced extraction techniques, based on optimized data from recent research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Advanced Extraction Techniques

| Technique | Optimal Conditions (Compound & Source Dependent) | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | Power: 216-360 W; Time: 30-90 min; Temp: 40-80°C [45] | Rapid, lower temperature, enhanced yield, simple equipment [40] | Potential for radical formation degrading compounds; scaling challenges [45] |

| MAE | Power: ~284 W; Time: ~5 min; Temp: ~54°C [38] | Extremely fast (minutes), high efficiency, significantly reduced solvent use [38] [41] | Selective heating; unsuitable for thermally labile compounds at high power |

| SFE | Fluid: CO₂; Temp: 40-80°C; Pressure: 100-500 bar [42] | Highly selective, tunable solvent power, eliminates organic solvent residue, low thermal degradation [42] | High capital investment, low polarity of CO₂ often requires modifiers |

| EAE | Enzyme: Pectinase/Cellulase; Temp: 40-60°C; Time: 1-24 h [43] | High specificity, mild conditions (aqueous, low temp), preserves native structure/function [43] | Long incubation times, high enzyme cost, narrow optimal parameter window |

| PLE | Temp: 50-200°C; Pressure: 10-15 MPa; Time: 5-20 min [44] | Fast, automated, uses small solvent volumes, high reproducibility [44] | High initial equipment cost, potential thermal degradation at higher temperatures |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) of Stevia Bioactives

This protocol is adapted from Kumar and Tripathy's 2025 study optimizing MAE for secondary bioactive compounds from stevia leaves [38].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Start with dried stevia leaves. Grind them using a mechanical grinder and pass the powder through a 60-mesh B.S.S. sieve to achieve a uniform particle size of approximately 250 microns [38].

- Objective: Uniform particle size ensures consistent and efficient extraction.

2. MAE Setup and Execution:

- Equipment: A closed-vessel microwave extraction system with temperature and pressure control is required.

- Weigh a specified mass (e.g., 1.0 g) of the prepared stevia powder into the microwave vessel.

- Add the extraction solvent. The optimized condition for stevia phenolics was a 53.10% ethanol-water solution [38].

- Seal the vessels and load them into the microwave system.

- Set the extraction parameters to the optimized conditions derived from an Artificial Neural Network-Genetic Algorithm (ANN-GA) model:

- Extraction Time: 5.15 min

- Microwave Power: 284.05 W

- Temperature: 53.89 °C [38]

- Initiate the extraction process. The system will maintain the set temperature and pressure for the duration.

3. Post-Extraction Processing:

- After completion, allow the vessels to cool before carefully opening.

- Separate the extract from the solid residue by vacuum filtration or centrifugation.

- The solvent can be removed from the extract using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure to obtain a concentrated extract.

- Analysis: The resulting extract is analyzed for Total Phenolic Content (TPC) using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, Total Flavonoid Content (TFC), and Antioxidant Activity (AA) using DPPH assay [38].

Detailed Protocol: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Piper nigrum Polysaccharides

This protocol is based on the 2025 optimization of PNP extraction [45].

1. Sample Pre-treatment:

- Take raw Piper nigrum L. (PNL), wash, and dry at 60°C. Grind the dried material and sieve it through a 60-mesh screen.

- To remove lipids and pigments, mix the powder with petroleum ether in a 1:5 (w/v) ratio. Reflux at 50°C for 2 hours. Filter and dry the defatted powder for subsequent use [45].

2. UAE Setup and Execution:

- Equipment: An ultrasonic bath or probe system with controllable power and temperature is required. The protocol below uses a bath with a frequency of 40 kHz.

- Weigh 10 g of the defatted PNL powder into a beaker.

- Add the extraction solvent (water) at the optimized liquid-to-material ratio of 36 mL/g [45].

- Place the beaker in the ultrasonic bath and extract under the following optimized conditions:

- Ultrasonic Power: 324 W

- Ultrasonic Time: 70 min

- Temperature: 78 °C [45]

- Ensure the system is covered to prevent solvent evaporation.

3. Post-Extraction Processing:

- After sonication, cool the mixture to room temperature.

- Centrifuge the slurry at 4200 rpm for 5 minutes and filter the supernatant to obtain the polysaccharide extract.

- Concentrate the supernatant under reduced pressure to approximately 15 mL.

- Precipitate the polysaccharides by adding 4 volumes of anhydrous ethanol and storing the solution at 4°C for 12 hours.

- Centrifuge again to isolate the crude polysaccharide precipitate.

- Re-dissolve the precipitate in a small volume of water and freeze-dry for 48 hours to obtain the final polysaccharide powder (UAE-PNP) [45].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Advanced Extraction Research

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function in Extraction Research | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) | Stable free radical compound used to evaluate the free radical scavenging ability and thus, the antioxidant activity of extracts spectrophotometrically. | Quantifying antioxidant activity in stevia extracts [38]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) Reagent | An oxidizing agent used in colorimetric assays to determine the total concentration of phenolic compounds (TPC) in an extract. | Measuring total phenolic content in stevia and plant extracts [38]. |

| Ethanol-Water Mixtures | Versatile, tunable-polarity solvent system. Ethanol is considered a greener solvent compared to methanol or hexane. | Optimized as a 50-53% solution for MAE of stevia phenolics [38]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ | The most common supercritical fluid. Non-toxic, non-flammable, and tunable from non-polar to moderately polar with modifiers. | Selective extraction of lipophilic compounds from plant matrices [42]. |

| Pectinase & Cellulase Enzymes | Hydrolyze pectin and cellulose, the primary structural components of plant cell walls, to facilitate the release of intracellular content. | Degrading cell walls in green leaves for protein extraction [43]. |

| Aluminum Chloride (AlCl₃) | Forms acid-stable complexes with the C-4 keto group and either the C-3 or C-5 hydroxyl group of flavones and flavonols, used for TFC assay. | Quantifying total flavonoid content in plant extracts [38]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Decision Pathway for Technique Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making pathway for selecting the most appropriate extraction technique based on key research objectives and compound properties.

Advanced Extraction Experimental Workflow