GC-IMS in Food Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This article provides a systematic review of Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) for researchers and scientists in food science and related fields.

GC-IMS in Food Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic review of Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) for researchers and scientists in food science and related fields. It covers the foundational principles of GC-IMS technology, detailed methodological workflows for food authentication and safety, optimization strategies for data analysis, and comparative validation against established techniques like GC-MS. By synthesizing recent applications and technical insights, this guide serves as a vital resource for implementing GC-IMS in research and development for precise, rapid volatile compound analysis.

Understanding GC-IMS: Principles, Advantages, and Core Strengths in Volatile Compound Analysis

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) is a hyphenated analytical technique that combines the high separation capability of gas chromatography (GC) with the sensitive, rapid detection of ion mobility spectrometry (IMS). This combination provides a powerful tool for the separation, detection, and identification of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in complex mixtures [1] [2]. The technique has gained significant traction in food analysis research due to its high sensitivity, typically in the low parts-per-billion (ppb) range, operational simplicity, and portability for potential on-site applications [3] [4].

The fundamental strength of GC-IMS lies in its two-dimensional separation process. The GC first separates compounds based on their partitioning between a mobile gas phase and a stationary phase, while the IMS subsequently separates these compounds based on their size, shape, and charge as they drift through a buffer gas under an electric field [5]. This orthogonal separation mechanism provides enhanced selectivity, especially for distinguishing isomeric compounds that are often challenging to resolve using either technique alone [4].

Core Technological Principles and Instrumentation

The Five-Step Analytical Process

The separation and detection process in GC-IMS can be divided into five distinct steps [1]:

- Sample Introduction: The volatile sample is introduced into the system, often via a flexible sampling method such as a six-port valve for gases or thermal desorption (TD) tubes for concentrated samples from various matrices [3] [6].

- Compound Separation: The sample is carried by an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or air) through a GC column, where compounds are separated based on their volatility and interaction with the column's stationary phase [3] [2].

- Ion Generation: The separated compounds eluting from the GC column are ionized. Common ionization sources include radioactive beta emitters (e.g., ³H or ⁶³Ni), corona discharge, or atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI) [5] [2]. The ionization can occur in either positive or negative mode, allowing the detection of a wide range of compounds such as ketones, aldehydes, amines, and halogenated compounds [3].

- Ion Separation: The ions are injected into the drift tube of the IMS, where they are propelled by a homogeneous electric field (e.g., 300 V/cm) through a counter-flowing drift gas. Their velocity depends on their collision cross-section (CCS), charge, and mass, leading to separation based on ion mobility [5] [6].

- Ion Detection: The separated ions arrive at a detector (e.g., a Faraday plate) at different times, generating a signal that is recorded. The result is a two-dimensional plot (retention time vs. drift time) providing a fingerprint of the sample's VOC profile [1] [4].

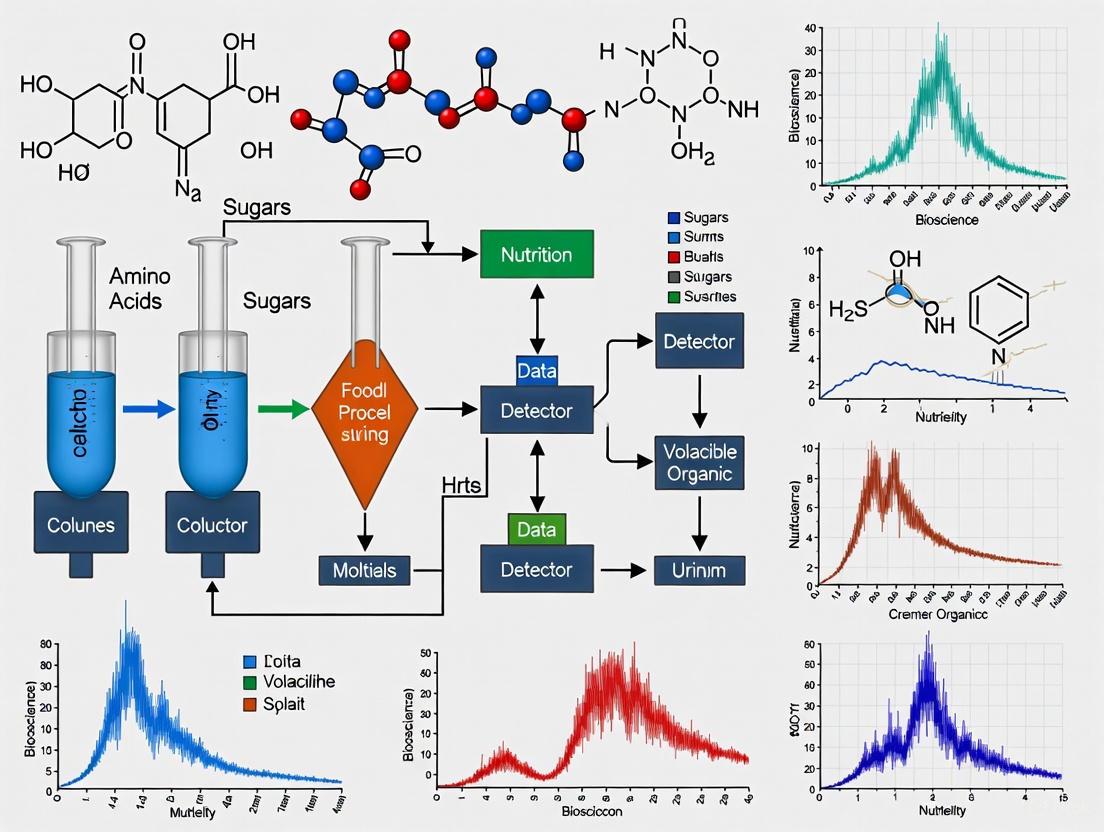

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and instrumental components of a typical GC-IMS system:

Key Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of GC-IMS is characterized by several key metrics, which are critical for researchers to evaluate its suitability for specific applications. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison with GC-MS based on a 2025 study, highlighting the distinct advantages of each technique [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of GC-IMS and GC-MS Performance (2025 Study)

| Performance Metric | GC-IMS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | ~10x more sensitive than MS (picogram/tube range) [6] | High sensitivity (nanogram/tube range) [6] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | 1-2 orders of magnitude (after linearization) [6] | >3 orders of magnitude (up to 1000 ng/tube) [6] |

| Long-Term Signal Intensity RSD | 3% to 13% over 16 months [6] | Not specified in search results |

| Long-Term Retention Time RSD | 0.10% to 0.22% over 16 months [6] | Not specified in search results |

| Long-Term Drift Time RSD | 0.49% to 0.51% over 16 months [6] | Not applicable |

| Operational Pressure | Atmospheric pressure [2] | High vacuum required [2] |

| Carrier Gas | Nitrogen or synthetic air [3] [2] | Often helium [2] |

Applications in Food Analysis Research

GC-IMS coupled with chemometric analysis has become a prominent method for the classification and authentication of geographical indication (GI) agricultural products and food [4]. This application is crucial for combating fraud and protecting brand value.

The general workflow involves sample collection, data acquisition via GC-IMS to obtain VOC fingerprints, data processing (including normalization and noise reduction), model construction using chemometric techniques, and final model interpretation [4]. Supervised methods like Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) are frequently employed for sample classification based on GC-IMS data [4].

Specific application examples in food research include:

- Rice Authentication: Differentiating authentic Wuchang rice from adulterated products [4].

- Meat Provenance: Classifying Jingyuan lamb and lamb from Xilinguole based on feeding regimens and origin [4].

- Beverage and Tea Analysis: Authenticating Shaoxing yellow wine and Fu brick tea [4].

- Off-flavour and Taint Detection: Monitoring for unpleasant flavours in propellant gases and other food products [3].

- Process and Storage Monitoring: Tracking volatile profile changes during food processing and storage [4] [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: GI Product Authentication Using TD-GC-IMS and Chemometrics

This protocol outlines the procedure for authenticating the geographical origin of a food product (e.g., rice or lamb) using Thermal Desorption GC-IMS combined with chemometric analysis [4] [6].

I. Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for TD-GC-IMS Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Thermal Desorption (TD) Tubes | Sample collection and concentration; contain specific adsorbent materials (e.g., Tenax) [6]. |

| Standard Compounds | High-purity (≥95%) reference substances for system calibration and compound identification (e.g., ketones, aldehydes, alcohols) [6]. |

| Internal Standards | Deuterated or other compounds not expected in the sample, for signal normalization and improved quantification (e.g., added to the TD tube) [6]. |

| GC Carrier Gas | High-purity Nitrogen (N₂) or synthetic air [3]. |

| IMS Drift Gas | High-purity Nitrogen (N₂) [3]. |

| Calibration Solutions | Stock solutions prepared in solvents like methanol for generating calibration curves [6]. |

II. Step-by-Step Methodology

Sample Collection:

- Collect a sufficient number of samples from known origins. Prioritize traceability, precision, and variety of sample information (e.g., exact origin, harvest season) over sheer quantity [4].

- For solid samples (e.g., rice, meat), place a representative portion into a headspace vial. For gaseous samples, pull air through a TD tube using a calibrated pump [6].

- Ensure proper labeling and documentation to avoid outliers caused by experimental errors [4].

Volatile Extraction and Introduction:

- For headspace analysis, incubate the vials at a controlled temperature and time to allow volatile compounds to equilibrate in the headspace [6].

- Use an automated headspace sampler or a gas-tight syringe to transfer the headspace vapor onto the TD tube or directly into the GC inlet.

- Alternatively, for TD, the tube is heated to desorb the concentrated VOCs directly into the GC column [6].

GC-IMS Data Acquisition:

- The GC is equipped with a standard capillary or multi-capillary column (e.g., 15-60m length) selected based on the analytical requirements [3].

- The GC oven temperature is programmed (e.g., isothermal between 40-80°C or with a firmware-steered ramp) to optimally separate the volatile compounds [3].

- The effluent from the GC is transferred to the IMS, which is operated at atmospheric pressure. The ionization source (e.g., ³H) ionizes the molecules, which are then separated in the drift tube [3] [2].

- Record the 3-D data (signal intensity, GC retention time, IMS drift time) for each sample. The resulting VOC profile serves as a fingerprint [3] [4].

Data Pre-processing:

- Use dedicated software (e.g., LAV - Laboratory Analytical Viewer) for data alignment using a reference substance to correct for retention time and drift time shifts [3] [4].

- Remove background noise and average replicate measurements [4].

- Normalize the data set using scaling methods such as unit variance, mean centering, or Pareto scaling. Apply smoothing algorithms (e.g., Savitzky-Golay) for further noise reduction [4].

Chemometric Model Construction and Validation:

- Divide the pre-processed data set into a training set and a test set [4].

- Perform an exploratory analysis using unsupervised methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify natural groupings and potential outliers [4].

- Construct a classification model using a supervised method such as PLS-DA to discriminate samples based on their origin [4].

- To maximize PLS-DA model accuracy, ensure the training set is balanced and contains samples with broad diversity within each class. A ratio where the number of training samples is at least 1.8-fold higher than the blind (test) samples is recommended [4].

- Validate the model using the independent test set and report classification accuracy.

Protocol: Quantitative VOC Analysis and Linearization for IMS

This protocol describes the quantification of specific VOCs (e.g., aldehydes) in a food matrix, addressing the non-linear response of IMS at higher concentrations [6].

I. Materials

- Aldehyde standard stock solution (Propanal, Butanal, Pentanal, Hexanal, etc.) in methanol [6].

- TD tubes and a calibrated syringe for liquid standard introduction [6].

- A mobile, temperature-controlled sampling unit for standardized adsorption of standards onto TD tubes [6].

II. Methodology

- Calibration Curve Preparation:

- Prepare a series of calibration solutions across the expected concentration range (e.g., from 0.1 ng/tube to 1000 ng/tube) [6].

- Use the controlled sampling unit to introduce precise volumes of these solutions onto individual TD tubes, ensuring reproducible adsorption by strictly controlling temperature and gas flow [6].

- Data Acquisition and Processing:

- Analyze the TD tubes using the GC-IMS method described in Protocol 4.1.

- Extract the peak volume or height for the target analyte from each calibration standard.

- Linearization and Quantification:

- Plot the signal intensity against the concentration. The IMS response will be linear for approximately one order of magnitude (e.g., 0.1 to 1 ng/tube for pentanal) before transitioning to a logarithmic response [6].

- Apply a linearization strategy to extend the linear calibration range to two orders of magnitude, improving quantitative accuracy [6].

- Use this linearized calibration model to quantify the target VOC in unknown samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Instrumental Components

Understanding the core components of a GC-IMS system and their alternatives is essential for method development.

Table 3: Essential GC-IMS System Components and Their Functions

| Component | Function & Variants |

|---|---|

| GC Column | Separates volatiles by polarity/volatility. Capillary columns (15-60m) offer high resolution; multi-capillary columns (MCC) offer faster analysis for less complex mixtures [3]. |

| Ionization Source | Generates ions from neutral molecules. Radioactive (³H, ⁶³Ni), Corona Discharge, and Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI) are common. Sealed, low-dose ³H sources are common in modern systems [5] [2]. |

| Drift Tube | Separates ions by size, shape, and charge. Drift Tube IMS (DTIMS) is standard; Differential Mobility Spectrometry (DMS) is an alternative that separates ions by mobility difference in high/low fields [1]. |

| Sample Introduction | Introduces the sample. Six-port valve offers flexibility for gases; Thermal Desorption (TD) tubes pre-concentrate trace analytes; Headspace autosampler automates solid/liquid sample analysis [3] [6]. |

| Circulating Gas Module | Circular Gas Flow Unit (CGFU) purifies and recycles the drift gas, enabling portable, on-site operation without external gas supplies [3]. |

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) represents a powerful analytical technique that combines the high separation capability of gas chromatography with the rapid detection of ion mobility spectrometry [7]. This dual separation mechanism enables the creation of highly specific volatile organic compound (VOC) fingerprints for complex samples, making it particularly valuable for food analysis, quality control, and authenticity verification [4] [8]. The technology has gained significant traction in research and industrial settings due to three fundamental advantages: exceptional analytical speed, high sensitivity for trace-level detection, and the practical benefit of operation at atmospheric pressure [9] [2]. These characteristics position GC-IMS as a compelling alternative to traditional analytical methods like GC-MS, especially for applications requiring rapid analysis, portability, or minimal sample preparation [2].

Core Technical Advantages

Operational Speed and Throughput

The rapid analysis time of GC-IMS stems from its orthogonal separation technology, where the fast response of IMS (typically in milliseconds) complements the separation power of GC [7] [10]. This combination enables complete analyses within remarkably short timeframes. A sample can typically be analyzed every 10 to 15 minutes, making the technique suitable for high-throughput screening applications [9]. The speed advantage is particularly evident in non-targeted screening approaches, where the entire VOC profile of a sample is captured in a single, rapid measurement without sensitivity loss, unlike the targeted single ion monitoring (SIM) mode often required in GC-MS for similar sensitivity [2].

Table 1: Key Speed and Throughput Characteristics of GC-IMS

| Feature | Performance Metric | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Speed | Milliseconds for IMS detection [7] | Faster than mass spectrometry detection |

| Total Analysis Time | 10-15 minutes per sample [9] | Enables high-throughput screening |

| Data Acquisition | Untargeted, full-spectrum without sensitivity loss [2] | No need for time-consuming method development for specific targets |

High Sensitivity and Detection Limits

GC-IMS achieves exceptional sensitivity, enabling the detection of volatile organic compounds at ultratrace concentration levels [8] [11]. Modern GC-IMS systems can reach detection limits in the mid parts-per-trillion by volume (pptv) range without requiring sample enrichment [2]. This high sensitivity is facilitated by efficient chemical ionization using low-dose radioactive sources (e.g., tritium) and the subsequent separation and detection of resulting ions [8] [11]. The technique is particularly sensitive for polar and medium-polarity compounds, making it ideal for analyzing flavor and aroma compounds in food matrices [12].

Operation at Atmospheric Pressure

A defining characteristic of GC-IMS is its operation at atmospheric pressure, which eliminates the need for energy-intensive vacuum systems required by mass spectrometry [4] [2]. This feature significantly simplifies instrument design, reduces operational costs, and enhances operational flexibility. Furthermore, GC-IMS can utilize nitrogen or purified air as the carrier and drift gas, reducing reliance on expensive and non-renewable helium, which is commonly required for GC-MS [12] [2]. Operation at ambient pressure also facilitates instrument miniaturization, enabling the development of portable and benchtop systems for on-site analysis [7] [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of GC-IMS and GC-MS Operational Parameters

| Parameter | GC-IMS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Pressure | Atmospheric [2] | High vacuum required [2] |

| Typical Carrier Gas | Nitrogen or air [12] [2] | Primarily helium [12] [2] |

| Detection Limits | pptv to ppbv range [2] [11] | Similar high sensitivity (ppbv to pptv) |

| Sample Throughput | 10-15 minutes/sample [9] | Often longer due to vacuum requirements |

| Portability | High (benchtop and portable systems available) [2] | Low (typically limited to laboratory) |

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Food Analysis Using GC-IMS

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for the non-targeted analysis of food samples, such as geographical indication (GI) products, using GC-IMS coupled with chemometrics [4].

Diagram 1: General chemometric analysis workflow for GC-IMS data.

Sample Collection and Preparation

- Sample Selection: Collect food samples with precise metadata (e.g., geographical origin, harvest season, processing technique). Traceability and variety are more critical than the sheer number of samples [4].

- Sample Preparation: For solid or semi-solid food samples (e.g., meat, grains, fruits), use headspace (HS) sampling. Precisely weigh (e.g., 1-5 g) the sample into a headspace vial. For liquid samples (e.g., wine, oil), aliquot directly into the vial [8] [9].

- Incubation: Seal vials and incubate at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40-80°C) for a defined time (e.g., 10-20 minutes) to allow volatile compounds to equilibrate in the headspace. No derivatization or complex extraction is typically needed [9] [2].

- Injection: Use an automated headspace sampler or gas-tight syringe to inject the volatile-laden headspace into the GC-IMS.

Instrumental Analysis: GC-IMS Parameters

- Gas Chromatography (GC):

- Column: Use a moderately polar or non-polar capillary column (e.g., DB-5, DB-624). Multicapillary columns (MCC) are also used for faster separations [11].

- Temperature: Employ a programmed temperature ramp optimized for the sample type (e.g., 40°C to 220°C at 5-10°C/min).

- Carrier Gas: Use nitrogen gas of high purity (≥99.999%) at a constant flow rate (e.g., 1-5 mL/min) [12].

- Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS):

- Ionization Source: Tritium (³H) source with low activity (e.g., 100-300 MBq) is common and exempt from authorization in the EU below 1 GBq [12] [8] [11].

- Drift Tube Temperature: Typically operated between 40-100°C. Newer "focus IMS" designs allow for higher temperatures (>100°C) to reduce peak tailing for high-boiling compounds like terpenes [12].

- Drift Gas: Use nitrogen or dried, purified air at a counter-flow of 100-500 mL/min [12] [11].

- Electric Field: Apply a weak electric field (100-350 V·cm⁻¹) across the drift tube [12].

Data Processing and Chemometric Analysis

- Data Preprocessing: Use proprietary instrument software or open-source packages (e.g., the Python

gc-ims-toolspackage) for data handling [13]. Steps include:- Background Subtraction: Remove background noise and the reactant ion peak (RIP) [4].

- Alignment: Align retention and drift times using an internal reference substance to correct for instrumental drift [4].

- Normalization: Apply scaling methods like unit variance, mean centering, or Pareto scaling to the data set [4].

- Exploratory Data Analysis:

- Supervised Classification:

- Construct classification models using algorithms like Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), or k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) to classify samples based on predefined categories (e.g., origin, authenticity) [4].

- Divide the data set into training and validation sets (e.g., 70:30 split) to prevent model overfitting [4] [11].

- For optimal PLS-DA performance, ensure the number of training samples is at least 1.8-fold higher than the number of validation samples, and the training set should be balanced and represent maximum diversity within each class [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for GC-IMS Food Analysis

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Containment and volatilization of samples | 10-20 mL volume, with PTFE/silicone septa; ensures airtight incubation [8]. |

| Internal Standards | Data alignment and quantification reference | Deuterated volatiles or compounds not found in the sample; corrects for instrumental drift [4]. |

| High-Purity Nitrogen | Carrier and drift gas | Purity ≥99.999%; provides the mobile phase for GC and the counter-gas for IMS [12] [2]. |

| Reference Compounds | Peak identification and method calibration | Pure volatile organic compound standards (e.g., aldehydes, ketones, terpenes) for creating reference databases. |

| Chemometric Software | Data processing and model building | Proprietary software or open-source packages (e.g., gc-ims-tools in Python) for multivariate analysis [13] [11]. |

Application in Food Analysis: A Case Study on Geographical Indication (GI) Protection

The combination of GC-IMS with chemometrics has proven highly effective for the classification and authentication of Geographical Indication (GI) agricultural products and food [4]. For instance, this approach has been successfully applied to:

- Authenticate Wuchang rice, a high-quality GI rice from China, where severe fraud incidents had resulted in adulterated products accounting for 90% of the market [4].

- Classify Jingyuan lamb from specific pastoral areas in Inner Mongolia based on its unique flavor profile derived from grazing and grass-feeding regimens [4].

- Differentiate Shaoxing yellow wine and Fu brick tea based on their unique VOC fingerprints associated with traditional processing procedures and geographical origin [4].

In these applications, the speed and sensitivity of GC-IMS allow for the rapid capture of complex VOC profiles, which serve as a unique chemical fingerprint. The operation at atmospheric pressure facilitates the potential for on-site analysis, which is crucial for regulatory bodies and quality control inspectors needing to verify authenticity directly in production or market settings. The resulting high-dimensional data is processed using the protocols outlined above, ultimately enabling reliable discrimination between authentic and fraudulent products with high accuracy [4].

Strengths in Resolving Isomers and Polar Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) represents a powerful two-dimensional separation technique that has emerged as particularly effective for analyzing volatile organic compounds (VOCs), especially in complex food matrices. This technology hyphenates the superior separation capabilities of gas chromatography with the rapid detection and high sensitivity of ion mobility spectrometry, operating at atmospheric pressure [7] [14]. The fundamental strength of GC-IMS lies in its orthogonal separation mechanism—compounds are first separated by their partitioning between gas and liquid phases in the GC column, followed by separation based on their charge, size, and shape in the IMS drift tube [15] [14]. This dual separation approach provides a significant advantage for resolving challenging compounds such as isomers and polar VOCs that are often difficult to distinguish using conventional analytical methods.

The application of GC-IMS in food analysis has gained substantial traction due to its exceptional sensitivity (typically in the low parts-per-billion range), portability, operational simplicity, and minimal sample preparation requirements [3] [10]. Unlike mass spectrometry-based techniques that require high vacuum systems, GC-MS operates at atmospheric pressure, making it suitable for both laboratory and field applications [7] [14]. These characteristics position GC-IMS as an ideal platform for addressing complex analytical challenges in food science, particularly in flavor profiling, quality control, authentication, and spoilage detection, where isomeric and polar volatile compounds play crucial roles as chemical markers.

Fundamental Principles of Isomer and Polar VOC Separation

Chromatographic Separation in GC

The first dimension of separation in GC-IMS occurs in the gas chromatograph, where compounds are separated based on their volatility and polarity relative to the stationary phase of the capillary column [16]. For GC-IMS analyses, typical configurations utilize standard capillary columns (15-60 m in length) with various stationary phases selected according to specific analytical requirements [3]. The separation of isomers begins in this stage, where structural differences—even slight variations in branching or functional group positioning—can result in different partition coefficients between the mobile and stationary phases, thus yielding distinct retention times [16]. This chromatographic step effectively distributes complex mixtures into temporally separated analyte bands before they enter the ion mobility spectrometer, reducing the likelihood of co-elution and simplifying subsequent mobility analysis.

Ion Mobility Separation Mechanism

The second dimension of separation occurs in the IMS, where compounds are differentiated based on their collision cross sections (CCS) in the gas phase [15]. After ionization (typically by a tritium source or corona discharge), ionized molecules are propelled through a drift tube filled with an inert buffer gas (such as nitrogen) under the influence of a weak electric field [17] [3]. The drift velocity of each ion depends on its size, shape, and charge [15]. Larger ions experience more collisions with the drift gas and thus migrate more slowly than compact ions. This separation mechanism is particularly effective for distinguishing isomers and isobaric compounds that have identical molecular weights but different three-dimensional structures [15] [14]. The resulting drift time serves as a physicochemical property that is characteristic of each compound's structural attributes, providing an additional identification parameter orthogonal to GC retention time.

Table 1: Key Separation Parameters in GC-IMS

| Parameter | Separation Basis | Impact on Isomers/Polar VOCs |

|---|---|---|

| GC Retention Time | Volatility, Polarity, Molecular Interaction with Stationary Phase | Separates based on slight differences in vapor pressure or polarity between isomers |

| IMS Drift Time | Collision Cross Section (Size, Shape, Charge) | Distinguishes structural isomers with different three-dimensional configurations |

| CCS Value | Ion-Neutral Gas Collision Frequency | Provides reproducible, instrument-independent structural identifier |

| Ionization Mode | Proton Affinity, Charge Distribution | Enables selective detection of different compound classes (positive/negative mode) |

Detection of Polar Compounds

Polar volatile organic compounds, including ketones, aldehydes, alcohols, and amines, are particularly well-suited for analysis by GC-IMS due to their enhanced ionization efficiency in IMS systems [3]. The ionization process in IMS typically produces protonated monomers (M+H)+ or proton-bound dimers (M₂H)+ for polar compounds, with the distribution between these forms depending on concentration, proton affinity, and experimental conditions [14]. The availability of both positive and negative ionization modes further enhances the technique's capability for analyzing diverse compound classes [3]. Polar compounds with high proton affinity, such as alcohols and aldehydes, ionize efficiently in positive mode, while compounds with high electron affinity, such as chlorinated hydrocarbons, are better detected in negative mode [3]. This flexibility makes GC-IMS highly effective for comprehensive profiling of complex VOC mixtures containing diverse chemical functionalities commonly encountered in food matrices.

Analytical Performance in Isomer Separation

Separation of Structural Isomers

GC-IMS has demonstrated exceptional capability in separating structural isomers that often co-elute in conventional gas chromatography systems. The orthogonal separation mechanism provides two independent parameters (retention time and drift time) that collectively enhance the resolution of compounds with identical molecular formulas but differing atomic connectivity [15]. Research has shown that even closely related isomers with minimal structural differences can be distinguished based on their distinct collision cross sections in the IMS dimension [15] [14]. This capability is particularly valuable in food analysis where specific isomeric ratios often serve as indicators of authenticity, quality, or origin. For instance, the technique has successfully differentiated isomeric terpenes in essential oils and isomeric aldehydes in lipid oxidation studies, providing crucial information for quality assessment and flavor chemistry research [7] [14].

Resolution of Stereoisomers

While IMS separation primarily depends on collision cross sections rather than chiral recognition, GC-IMS can still contribute to stereoisomer analysis when coupled with appropriate chiral stationary phases in the GC dimension [18]. The differentiation of enantiomers remains challenging for standard GC-IMS systems; however, the technique can resolve diastereomers that possess different three-dimensional structures and consequently different collision cross sections [18]. In the analysis of borneol and isoborneol stereoisomers, chiral GC columns provided initial separation, while IMS detection offered additional confirmation through distinct mobility signatures [18]. This combined approach enhances the reliability of stereoisomeric analysis in complex matrices. The application of GC-IMS for distinguishing diastereomeric compounds has significant implications for food authentication, as the relative abundances of specific stereoisomers often serve as markers for natural versus synthetic origin or for detecting adulteration in high-value food products.

Table 2: Representative Isomer Separations by GC-IMS in Food Analysis

| Isomer Pair/Class | Matrix | Separation Basis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpene Isomers | Essential Oils, Spices | Slight differences in CCS due to branching patterns | Quality control, authenticity assessment |

| Aldehyde Isomers | Lipid-containing Foods | Structural differences affecting molecular size/shape | Lipid oxidation monitoring, off-flavor detection |

| Borneol/Isoborneol | Herbal Products, Flavors | GC retention time combined with CCS differences | Distinguishing natural vs. synthetic sources [18] |

| Ketone Isomers | Fermented Products | Variations in three-dimensional structure | Process monitoring, flavor characterization |

| Alcohol Isomers | Beverages | Differences in hydrogen bonding capacity | Quality assessment, origin verification |

Analysis of Polar Volatile Organic Compounds

Detection of Oxygenated Compounds

GC-IMS exhibits particularly high sensitivity and selectivity for oxygenated polar compounds that are ubiquitous in food aromas and degradation pathways. Key chemical classes including aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, esters, and organic acids are efficiently ionized and detected due to their favorable proton affinities [7] [14]. These compounds frequently serve as critical markers for food quality assessment, as they originate from various biochemical processes including lipid oxidation, microbial metabolism, enzymatic activity, and Maillard reactions [14] [10]. The technique's capability to detect and quantify these polar compounds at low concentration levels (typically parts-per-billion to parts-per-trillion ranges) enables early detection of spoilage, monitoring of maturation processes, and characterization of flavor profiles [17] [14]. For instance, GC-IMS has been successfully employed to track the formation of specific carbonyl compounds during lipid oxidation in meat and dairy products, providing valuable insights into quality deterioration kinetics [14].

Monitoring Nitrogen- and Sulfur-Containing Compounds

GC-IMS demonstrates robust performance in analyzing nitrogen- and sulfur-containing volatile compounds that often contribute significantly to food aromas, both desirable and undesirable [3]. These compounds, including amines, thiols, and sulfur heterocycles, typically exhibit strong odors at extremely low concentrations and play crucial roles in the flavor profiles of various food products, particularly fermented foods, cooked meats, and allium vegetables [17] [3]. The negative mode ionization capability of GC-IMS systems enhances the detection of compounds with high electron affinity, such as certain sulfur compounds, providing complementary analytical information to positive mode detection [3]. This capability has been leveraged in food safety applications, such as monitoring biogenic amine formation in fermented products and detecting sulfur-based spoilage markers in seafood [14] [10]. The exceptional sensitivity of GC-IMS to these compound classes enables early detection of microbial contamination and quality deterioration before overt spoilage characteristics become evident.

Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure for Food VOC Analysis

Sample Preparation:

- For solid food samples, homogenize 2.0 g of material and transfer to a 20 mL headspace vial.

- For liquid samples, pipette 1.0 mL directly into the headspace vial.

- Add internal standards as appropriate for quantification (e.g., chlorobenzene-d5 for non-polar compounds, 2-octanol for polar compounds).

- Crimp-seal the vials with PTFE/silicone septa and proceed to analysis or store at 4°C for short-term preservation (maximum 24 hours) [19] [17].

Instrumental Parameters:

- GC Conditions:

- Column: mxt-5 capillary column (15 m × 0.53 mm × 1 μm) or equivalent mid-polarity stationary phase [17]

- Injector temperature: 80°C [17]

- Column temperature: 40°C initial, with programmed ramping based on analyte volatility (e.g., 5-10°C/min to 150-200°C) [17]

- Carrier gas: Nitrogen or high-purity synthetic air, flow rate 2-5 mL/min [17] [3]

- IMS Conditions:

Data Acquisition:

- Incubate samples at 60°C for 10 minutes with agitation at 500 rpm [17].

- Inject 100-1000 μL of headspace gas via heated syringe (60-80°C) [17] [3].

- Acquire data for 15-30 minutes total run time, depending on complexity of the VOC profile [17].

- Perform triplicate analyses for each sample to ensure analytical reproducibility.

Specialized Protocol for Isomer Separation

For challenging separations of structural isomers, the following method modifications are recommended:

Enhanced GC Separation:

- Employ longer GC columns (30-60 m) with appropriate stationary phase selectivity for the target isomer class [3].

- Implement slower temperature ramping (1-2°C/min) through the critical separation range to maximize chromatographic resolution [16].

- Optimize carrier gas flow rates (1-2 mL/min) to balance separation efficiency and analysis time [3].

IMS Parameter Optimization:

- Increase drift tube length (if instrument configuration allows) to enhance mobility resolution [15].

- Precisely control drift gas flow and temperature to maximize differences in collision cross sections [15].

- Adjust ionization energy to favor molecular ion formation over fragmentation, preserving molecular structure information [15] [3].

Data Analysis Approach:

- Utilize two-dimensional data visualization (retention time vs. drift time) to identify isomer clusters [7] [14].

- Employ principal component analysis (PCA) and other multivariate statistical methods to differentiate samples based on subtle variations in isomer ratios [13] [14].

- Compare experimental collision cross section values with reference databases when available to support identification [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GC-IMS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standard Mix | Quantification reference, retention time marker | CLP 04.1 VOA Internal Standard/SMC Spike Mix diluted in methanol to 2.5 µg/mL [19] |

| Chiral Derivatization Reagents | Enantiomer separation enhancement | (R)-(+)-MTPA-Cl or (1S)-(−)-camphanic chloride for chiral separation prior to GC-IMS analysis [18] |

| Thermal Desorption Tubes | VOC preconcentration from air/gas samples | Hydrophobic multi-bed thermal desorption tubes (e.g., C2-AAXX-5032) for headspace sampling [19] |

| Headspace Vials | Sample containment and incubation | 10-20 mL crimp-top vials with PTFE/silicone septa, compatible with autosamplers [19] [17] |

| Nitrogen Gas | Carrier and drift gas | High purity (99.999%) generated internally or supplied externally [17] [3] |

| Cytology Brushes | Non-invasive sample collection | Soft cytology brushes for lesional brushing sampling from solid surfaces [19] |

Application Examples in Food Analysis

Food Authentication and Adulteration Detection

GC-IMS has demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in food authentication applications, where subtle differences in VOC profiles serve as chemical fingerprints for origin verification and adulteration detection. In a comprehensive study on Iberian hams, the technique successfully discriminated between acorn-fed and feed-fed animals based on distinct VOC patterns, including isomeric ratios of specific aldehydes and ketones [7] [14]. Similarly, research on honey authentication revealed that GC-IMS could differentiate botanical and geographical origins with higher throughput and simpler operation compared to NMR-based methods, effectively preventing fraudulent labeling [7] [14]. The technique's capability to resolve complex mixtures of isomers and polar compounds enables the identification of subtle chemical markers that are characteristic of authentic products, providing a powerful tool for quality control and regulatory compliance in the food industry.

Freshness Evaluation and Spoilage Monitoring

The exceptional sensitivity of GC-IMS to polar volatile compounds makes it ideally suited for monitoring food freshness and detecting early spoilage indicators. Research on silver carp demonstrated that the technique could track the progressive formation of specific aldehydes (hexanal, heptanal), ketones, and alcohols generated by dominant spoilage bacteria during chilled storage [14]. Similarly, studies on egg freshness revealed that GC-IMS could classify eggs based on storage time by monitoring the evolution of sulfur-containing compounds and other spoilage markers [14]. The ability to detect these compounds at low concentration levels enables early warning of quality deterioration before overt sensory changes occur. Furthermore, the technique's rapid analysis time (typically 15-30 minutes) and minimal sample preparation facilitate high-throughput screening of perishable products throughout the supply chain, reducing food waste and ensuring product quality and safety.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Advantages Over Alternative Techniques

GC-IMS offers several distinct advantages compared to other analytical platforms for VOC analysis in food matrices. Unlike GC-MS with electron ionization, which often produces extensive fragmentation and may lose molecular ion information, GC-IMS typically preserves molecular ion signals, facilitating compound identification [15] [14]. Compared to electronic nose systems, GC-IMS provides actual compound separation and identification rather than merely generating fingerprint patterns [14]. The technique's operation at atmospheric pressure eliminates the need for high vacuum systems, reducing instrumental complexity and enabling portable configurations for field analysis [7] [14]. Additionally, GC-IMS demonstrates superior sensitivity to polar compounds compared to many conventional GC detectors, with detection limits typically in the parts-per-billion to parts-per-trillion range for most volatile analytes [3] [14]. The technique's rapid analysis time (typically 15-30 minutes per sample) and minimal sample preparation requirements further enhance its practicality for quality control and high-throughput screening applications in food production environments [7] [10].

Current Limitations and Research Needs

Despite its significant strengths, GC-IMS technology faces certain limitations that present opportunities for future development. The limited reference databases for IMS spectra compared to the extensive mass spectral libraries available for GC-MS represents a current constraint in compound identification [7] [14]. While collision cross section values provide valuable structural information, the establishment of comprehensive, standardized databases is still ongoing [15]. The quantitative capabilities of GC-IMS, while sufficient for many applications, may be affected by humidity and matrix effects more significantly than some established quantification techniques [14]. Additionally, the resolution power of current commercial IMS systems, though continuously improving, generally remains lower than that of high-resolution mass spectrometry for complex mixtures [15]. Future research directions should focus on expanding reference databases, developing standardized quantification protocols, enhancing IMS resolving power through instrumental innovations, and exploring advanced data mining approaches for extracting maximum information from two-dimensional GC-IMS data sets [15] [14] [10].

GC-IMS technology represents a powerful analytical platform with particular strengths in resolving isomers and detecting polar volatile organic compounds in complex food matrices. The technique's orthogonal separation mechanism, combining gas chromatographic retention with ion mobility separation, provides two independent parameters that enhance the discrimination of structurally similar compounds. Its high sensitivity to oxygenated, nitrogenated, and sulfur-containing compounds—many of which serve as key aroma and quality markers in foods—makes it particularly valuable for food flavor analysis, authentication, and quality control applications. While certain limitations exist, particularly regarding reference databases and quantitative standardization, ongoing technological advancements and growing research engagement are rapidly addressing these challenges. As GC-IMS continues to evolve, it is poised to play an increasingly significant role in food analysis, providing researchers and quality control professionals with a rapid, sensitive, and information-rich analytical tool for addressing complex chemical characterization challenges across the food industry.

GC-IMS Workflow for Isomer and VOC Analysis

GC-IMS Applications in Food Analysis

Comparison of GC-IMS with Traditional Flavor Analysis Techniques (GC-MS, E-nose, GC-O)

Flavor analysis is a critical component of food quality control, product development, and authenticity verification. Traditional techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), electronic nose (E-nose), and gas chromatography-olfactometry (GC-O) have long been employed for volatile organic compound (VOC) characterization. Recently, gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) has emerged as a powerful complementary technique. This analytical note provides a structured comparison of these technologies, detailing their respective principles, applications, advantages, and limitations within food analysis research. GC-IMS combines the high separation capability of gas chromatography with the rapid response of ion mobility spectrometry, creating a highly sensitive technique for detecting trace-level VOCs at ambient pressure without demanding vacuum systems [9] [8].

Technology Comparison and Principles

Fundamental Operating Principles

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) separates ionized molecules in the gas phase under the influence of an electric field at atmospheric pressure. The core IMS principle involves ionizing analyte molecules, typically using a tritium or nickel-63 radioactive source, though non-radioactive alternatives like corona discharge exist. The resulting ions drift through a counter-current drift gas at ambient pressure, separating based on their collision cross-section (CCS), mass, and charge [9] [8]. When coupled with GC pre-separation, this creates a two-dimensional analytical technique (retention time × drift time) with high sensitivity for trace-level VOC detection, typically in the parts-per-billion (ppb) range [1] [8].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) has been the gold standard for VOC analysis for decades, providing excellent separation combined with mass spectral identification. It operates under high vacuum and identifies compounds based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). While GC-MS provides superior compound identification through extensive spectral libraries, it requires more complex sample preparation, vacuum operation, and often longer analysis times compared to GC-IMS [9] [20].

Electronic Nose (E-nose) systems utilize an array of non-specific chemical sensors (typically metal oxide or conducting polymer sensors) that respond to broad classes of volatiles. The resulting "fingerprint" pattern is interpreted using multivariate statistical methods. E-nose provides rapid, non-destructive analysis but offers limited quantitative capability and cannot identify individual compounds [21] [22].

Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry (GC-O) couples chromatographic separation with human sensory evaluation, directly linking chemical compounds to perceived aroma. This technique is invaluable for identifying key odor-active compounds but is inherently subjective and requires trained panelists [23].

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical comparison of flavor analysis techniques

| Parameter | GC-IMS | GC-MS | E-nose | GC-O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Drift time/Collision cross-section | Mass-to-charge ratio | Chemical sensor array | Human olfactory response |

| Detection Limit | ppb level [9] [8] | ppt-ppb level | Variable | Compound-dependent |

| Analysis Time | Medium-Fast (10-30 min) [9] | Medium-Slow (30-60+ min) | Fast (minutes) [21] | Slow (chromatography-dependent) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (often none) [24] [8] | Extensive (often required) [9] [20] | Minimal | Extensive (to protect column) |

| Identification Capability | Library-dependent (growing databases) [22] | Excellent (extensive libraries) | None (pattern recognition only) | Compound identification + sensory impact |

| Quantitation | Good (relative) | Excellent (absolute) | Limited (relative patterns) | Semi-quantitative |

| Operational Pressure | Ambient [9] [8] | High vacuum | Ambient | High vacuum |

| Portability | Benchtop and portable systems available [9] | Primarily laboratory-based | Portable systems common | Laboratory-based only |

Application-Specific Performance

Table 2: Application strengths across food matrices

| Application Area | GC-IMS | GC-MS | E-nose | GC-O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Authentication | Excellent [8] | Excellent | Good | Limited |

| Process Monitoring | Excellent (rapid analysis) [8] | Good | Excellent (real-time capability) | Poor |

| Off-flavor Detection | Excellent (sensitive to spoilage markers) | Excellent | Good | Excellent (direct sensory link) |

| Key Aroma Compound Identification | Good (needs complementary techniques) [22] | Excellent | Poor | Excellent (primary application) |

| Freshness Assessment | Excellent [22] | Good | Excellent | Limited |

| High-Throughput Screening | Good | Limited | Excellent | Poor |

Experimental Protocols

Standard GC-IMS Analysis Protocol for Solid Food Matrices

Application Note: This protocol has been successfully applied to analyze volatile profiles in various solid food matrices including chili powders [21], soybean pastes [22], citrus peels [24], and turmeric [25].

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Essential research reagents and solutions

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| GC-IMS Instrument | FlavourSpec (G.A.S.) or equivalent | VOC separation and detection |

| Headspace Vials | 20 mL, glass with PTFE/silicone septa | Sample containment and volatile accumulation |

| Gas Supply | Nitrogen (≥99.999% purity) | Carrier and drift gas |

| External Standards | n-ketones C4-C9 (2-butanone to 2-nonanone) [21] | Retention index (RI) calibration |

| Analytical Balance | Precision ±0.1 mg | Accurate sample weighing |

| Incubator/Heating Block | Temperature range: 40-100°C, ±0.1°C control | Sample temperature equilibration |

| Autosampler | Compatible with headspace vials (optional) | Automated sample injection |

Sample Preparation Procedure

- Homogenization: Grind solid samples to a consistent particle size (e.g., 0.5-1 mm diameter) to ensure uniform volatile release.

- Weighing: Accurately weigh 1.0-3.0 g of sample into a 20 mL headspace vial [21] [22]. Optimal mass should be determined empirically for each matrix.

- Equilibration: Seal vials immediately and incubate at 60-80°C for 10-20 minutes to allow volatile accumulation in the headspace [21] [22].

- Injection: Automatically inject 100-500 μL of headspace gas using a heated syringe (typically 75-85°C to prevent condensation) [21] [22].

Instrumental Parameters

Table 4: Typical GC-IMS parameters for food analysis

| Parameter | Setting | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GC Conditions | ||

| Column | MXT-5 or MXT-WAX (15-30 m × 0.53 mm ID) | Choice depends on analyte polarity |

| Column Temperature | 40-80°C (isothermal or gradient) | Chili powder analysis used 60°C [22] |

| Carrier Gas Flow | 2-150 mL/min (programmed) | Initial 2 mL/min, ramped to 100 mL/min [22] |

| IMS Conditions | ||

| Drift Tube Temperature | 40-50°C | |

| Drift Gas Flow | 75-150 mL/min (nitrogen) | |

| Ionization Source | Tritium (300 MBq) or radioactive alternative | |

| Electric Field Strength | 300-500 V/cm | |

| Analysis Time | 10-30 minutes | Method-dependent |

Data Analysis Workflow

- Preprocessing: Normalize raw data to reactant ion peak (RIP), perform background subtraction, and align retention and drift times.

- Identification: Compare retention indices (RI) and drift times against internal databases (e.g., NIST, IMS) [21].

- Fingerprint Analysis: Use Gallery Plot or similar visualization tools to compare VOC patterns across samples.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply multivariate methods (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify discriminant markers [21] [22].

Integrated Approach: Multi-Technique Flavor Analysis

For comprehensive flavor characterization, an integrated approach combining multiple techniques provides complementary data:

- Rapid Screening: Use E-nose for initial sample classification and quality control [21] [22].

- Targeted Compound Identification: Apply GC-MS for definitive identification and quantitation of key aroma compounds [24].

- Volatile Fingerprinting: Employ GC-IMS for sensitive detection of trace VOCs and pattern recognition [21] [25].

- Sensory Relevance Determination: Utilize GC-O to identify odor-active compounds contributing to overall aroma [23].

Applications in Food Analysis Research

Case Study: Chili Powder Spiciness Differentiation

A recent study demonstrated GC-IMS's effectiveness in differentiating chili powders based on spiciness levels (light, medium, strong) [21]. Researchers combined E-nose, GC-IMS, and chemometrics to analyze VOC profiles:

- Sample Preparation: 2g samples in 20mL vials, equilibrated at 25°C for 30 minutes (E-nose); 3g samples incubated at 80°C for 5 minutes (GC-IMS) [21].

- Key Findings: GC-IMS identified 48 VOCs, primarily aldehydes (51.74-55.55%) and ketones (29.93-32.09%). Statistical analysis (VIP >1, p<0.05) highlighted 21 marker volatiles, with 14 differential compounds (FC >2 or <0.5) across spiciness levels [21].

- Comparative Advantage: GC-IMS provided superior differentiation of samples based on spiciness compared to E-nose alone, while identifying specific marker compounds (e.g., (E,E)-2,4-heptadienal, butanal, 3-methylbutanal) associated with flavor differences [21].

Comparative Performance in Complex Matrices

In analysis of Citrus reticulata 'Chachi' peel, GC-IMS demonstrated advantages over HS-SPME-GC-MS for certain applications [24]:

- Speed: GC-IMS analysis required less sample preparation time compared to HS-SPME-GC-MS.

- Sensitivity: GC-IMS effectively detected trace compounds that were challenging for GC-MS.

- Complementarity: The techniques identified overlapping but distinct VOC profiles, with GC-IMS particularly effective for terpenes and esters [24].

Similar advantages were reported in soybean paste analysis, where GC-IMS detected 111 volatile flavor compounds and, combined with PLS-DA, identified 41 marker compounds differentiating four paste types [22].

GC-IMS represents a valuable addition to the analytical arsenal for flavor research, particularly when used complementarily with established techniques like GC-MS, E-nose, and GC-O. Its strengths in rapid analysis, high sensitivity at trace levels, minimal sample preparation, and operational simplicity make it ideal for quality control, authentication, and process monitoring applications. While GC-MS remains superior for definitive compound identification and GC-O for establishing sensory relevance, GC-IMS fills a critical niche for high-throughput volatile fingerprinting and marker-based discrimination. The integration of multiple techniques provides the most comprehensive approach to understanding complex flavor systems, leveraging the respective strengths of each analytical method.

GC-IMS in Practice: Workflows and Applications for Food Authentication and Safety

Gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for food analysis, particularly valuable for classifying and authenticating geographical indication (GI) agricultural products and foodstuffs [26] [4]. This technique combines the high separation capability of gas chromatography with the fast response and high sensitivity of ion mobility spectrometry, operating at atmospheric pressure without vacuum pumps [26]. The analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using GC-IMS provides characteristic fingerprints that can be leveraged for food authentication, quality control, and fraud detection [14] [10]. The integration of chemometric analysis with GC-IMS data has become essential for extracting meaningful information from complex VOC profiles, enabling researchers to distinguish subtle differences between similar samples [26] [27]. This application note details the standard workflow from sample collection through model interpretation, providing researchers with a structured framework for implementing GC-IMS in food analysis research.

Fundamental Principles of GC-IMS

GC-IMS separates and detects volatile organic compounds through a two-dimensional process. First, compounds are separated by their partitioning between a mobile gas phase and a stationary phase in the GC column, represented by their retention time. Subsequently, molecules are ionized (typically by a β-radiation source such as tritium) and separated in the drift tube based on their size, shape, and charge as they move through a counter-flow drift gas under a weak electric field [8]. The drift time is used to calculate the reduced ion mobility (K0), which serves as a identifying parameter [8]. This orthogonal separation mechanism provides GC-IMS with superior capability for identifying isomeric molecules compared to traditional GC-MS [26]. The technique offers several advantages for food analysis, including high sensitivity (ppbv levels), rapid analysis times, operational simplicity, and portability for potential field applications [14] [7].

Standard Experimental Workflow

The standard workflow for GC-IMS analysis in food applications follows a systematic five-stage process that ensures reliable and reproducible results. Each stage requires careful execution to maintain data integrity throughout the analytical pipeline.

Stage 1: Sample Collection

The initial stage of sample collection establishes the foundation for reliable GC-IMS analysis. In food authentication studies, traceability, precision, and variety are more critical than simply maximizing sample numbers [26]. Comprehensive documentation of sample origin, harvest season, processing methods, and storage conditions is essential for building robust classification models [4]. For geographical indication products, this includes recording specific geographical coordinates, traditional processing procedures, and indigenous varieties or breeds [26]. Experimental errors or mislabeling at this stage can introduce outliers that significantly impact model performance [26].

Table 1: Sample Collection Considerations for GC-IMS Analysis

| Factor | Importance | Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical Origin | Critical for GI authentication | GPS coordinates, region, soil type |

| Harvest Season | Affects volatile compound profiles | Harvest date, seasonal conditions |

| Processing Methods | Impacts flavor fingerprint | Traditional techniques, processing duration |

| Storage Conditions | Influences VOC stability | Temperature, humidity, duration |

| Sample Homogeneity | Ensures representative analysis | Particle size, mixing method |

Stage 2: Data Acquisition

Data acquisition involves VOC extraction and separation through the GC-IMS system. Sample introduction is typically performed via headspace sampling, which requires minimal sample preparation and reduces the introduction of non-volatile compounds that could contaminate the system [8]. The GC separation occurs using moderately polar to non-polar columns (e.g., MXT-5, SE-54, RTX-5) with common dimensions of 15-30m length × 0.53mm diameter [26]. Following GC separation, compounds enter the IMS drift tube where they are ionized and separated based on their mobility in the electric field. The resulting data is represented as a two-dimensional plot with GC retention time on one axis and IMS drift time on the other, creating a unique VOC fingerprint for each sample [26] [4].

Stage 3: Data Processing

Data processing transforms raw GC-IMS data into formats suitable for chemometric analysis. Key steps include signal alignment using reference substances to correct for retention time shifts, particularly when using long separation columns [4]. Background noise removal is performed through algorithms such as Savitzky-Golay or Gaussian smoothing [4]. Data sets are normalized using scaling methods like unit variance, mean centering, and Pareto scaling to ensure comparability between samples [4]. The processed data set is then divided into training and test sets, with a recommended ratio where the number of training samples is at least 1.8-fold higher than blind samples for optimal model performance [4].

Stage 4: Model Construction

Model construction employs chemometric techniques to extract meaningful patterns from processed GC-IMS data. The process typically begins with exploratory, unsupervised methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) or hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) to identify natural groupings and detect outliers [4]. Subsequently, supervised classification techniques including partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), k-nearest neighbor (kNN), or soft independent modeling of class analogy (SIMCA) are applied to build predictive models [26] [4]. PLS-DA has proven particularly effective for sample classification in food authentication studies due to its ability to recognize subtle differences between similar samples [26] [27].

Stage 5: Model Interpretation

The final stage focuses on interpreting model performance and identifying discriminatory compounds. Model capability is typically assessed through classification accuracy, representing the ratio of correctly predicted samples [4]. However, accuracy alone can be misleading due to overfitting risks, making validation with independent test sets essential [4]. For PLS-DA models, key performance considerations include using balanced training sets with broad diversity across classes and ensuring sufficient training samples (e.g., approximately 450 samples for predicting 300 blind samples in Iberian ham authentication) [4]. Identification of significant VOCs contributing to class separation enhances the biological interpretation of models and validates their utility for authentication purposes.

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Geographical Origin Authentication of Agricultural Products

This protocol outlines the procedure for authenticating the geographical origin of agricultural products using GC-IMS coupled with chemometric analysis, with application to various products including rice, honey, tea, and wine [26].

Materials and Reagents

- GC-IMS instrument equipped with tritium ionization source

- Headspace vials (10-20 mL) with crimp-top caps

- Standard non-polar GC column (MXT-5, 15 m × 0.53 mm × 1 μm)

- Nitrogen gas (≥99.999% purity) as drift and carrier gas

- Internal standards (e.g., ketones or alcohols for retention index calibration)

Experimental Procedure

- Collect representative samples from different geographical origins with verified provenance

- Homogenize samples to consistent particle size (e.g., 0.5 mm for solid samples)

- Weigh 2.0 g ± 0.1 g of sample into 20 mL headspace vials

- Incubate vials at 40°C for 15 minutes to establish headspace equilibrium

- Inject 500 μL headspace sample into GC-IMS with splitless injection mode

- Use the following typical GC temperature program: 40°C (hold 2 min), ramp to 240°C at 10°C/min

- Maintain IMS drift tube temperature at 45°C with drift gas flow of 150 mL/min

- Acquire data in positive ion mode with drift time range of 5-25 ms

- Repeat each sample analysis in triplicate to account for technical variability

Data Analysis

- Process raw data using GC-IMS software (e.g., gc-ims-tools Python package)

- Perform peak detection and alignment using internal standards

- Normalize data using unit variance scaling

- Apply PCA to explore natural clustering by geographical origin

- Develop PLS-DA model with 70:30 training:test split

- Validate model using k-fold cross-validation (k=7)

- Identify significant marker compounds with VIP scores >1.5

Protocol 2: Food Adulteration Detection

This protocol details the procedure for detecting food adulteration using GC-IMS fingerprinting, applicable to products such as honey, olive oil, and spices [14] [7].

Materials and Reagents

- GC-IMS instrument with automated headspace sampler

- Chemical standards for suspected adulterants

- Quality control samples (verified pure and adulterated materials)

- Data processing software (e.g., LAV, GC-IMS Library)

Experimental Procedure

- Prepare authentic and potentially adulterated samples

- For liquid samples (e.g., honey), dilute 1:1 with ultrapure water

- For oil samples, use direct headspace analysis without dilution

- Equilibrate samples at 60°C for 10 minutes with 500 rpm agitation

- Inject 200 μL headspace with split ratio 1:10

- Use GC temperature gradient: 60°C to 180°C at 15°C/min

- Set IMS temperature to 50°C with electric field strength of 400 V/cm

- Include quality control samples every 10 injections to monitor system stability

Data Analysis

- Generate VOC fingerprints for all samples

- Use targeted screening to identify known adulterant markers

- Apply non-targeted screening to detect unexpected adulteration

- Develop SIMCA models for class membership assessment

- Calculate limit of detection for specific adulterants

- Establish decision thresholds based on receiver operating characteristic curves

Table 2: Key Chemometric Methods for GC-IMS Data Analysis

| Method Type | Specific Techniques | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory (Unsupervised) | PCA, HCA | Pattern recognition, outlier detection | Reveals natural sample grouping, no prior knowledge needed |

| Classification (Supervised) | PLS-DA, LDA, kNN | Sample classification, authentication | High prediction accuracy, handles correlated variables |

| Regression | PLSR, PCR | Quantitative analysis, prediction | Models continuous variables, handles multiple predictors |

| Feature Selection | VIP, ANOVA, RF | Marker identification | Reduces data complexity, identifies significant compounds |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GC-IMS Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | Retention time alignment, quantification | Use deuterated compounds or ketones (C4-C9) not present in samples |

| Quality Control Samples | System suitability testing, data quality assurance | Use pooled sample aliquots or certified reference materials |

| Drift Gas Filters | Purify drift gas, remove contaminants | Moisture and hydrocarbon traps required for stable reactant ions |

| Headspace Standards | Method validation, performance verification | Prepare at concentrations spanning expected sample range |

| Column Conditioning Standards | GC column performance monitoring | Inject periodically to monitor column degradation |

| IMS Calibration Standards | Drift time calibration, mobility calculation | Use ketones or alkyl esters with known reduced mobility values |

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Optimizing PLS-DA Model Performance

The accuracy of PLS-DA models commonly used with GC-IMS data depends on several critical factors. First, the training set composition significantly impacts model performance; balanced training sets with samples distributed over the maximum area in the PCA score plot yield optimal results [4]. Second, the training-to-validation set ratio should be optimized, with research indicating that accuracy ≥85% is achieved when training samples exceed blind samples by at least 1.8-fold [4]. Third, sufficient sample numbers are essential, with one study demonstrating that approximately 450 training samples enabled reliable prediction of 300 blind samples for Iberian ham authentication [4]. Additionally, proper feature selection using variable importance in projection (VIP) scores enhances model interpretability and performance by focusing on the most discriminatory compounds.

Data Processing Strategies

Effective data processing is crucial for extracting meaningful information from GC-IMS fingerprints. Signal alignment corrects for retention time shifts using a reference substance, especially important when using long separation columns [4]. Noise reduction algorithms such as Savitzky-Golay smoothing improve signal-to-noise ratios without significantly distorting spectral features [4]. Normalization techniques including unit variance, mean centering, and Pareto scaling address variations in absolute signal intensities between samples, ensuring comparability [4]. For complex data sets, data fusion approaches that combine GC-IMS data with complementary techniques like GC-MS can provide enhanced classification power, though this requires careful optimization of the fusion methodology [27].

The standardized workflow for GC-IMS analysis presented in this application note provides researchers with a systematic framework for implementing this powerful technique in food authentication and quality control applications. The integration of robust sample collection procedures, optimized instrumental parameters, and appropriate chemometric methods enables reliable classification and authentication of geographical indication products. As GC-IMS technology continues to evolve with improved instrumentation and expanding compound libraries, its application in food analysis is expected to grow significantly. The development of open-source data analysis tools such as the gc-ims-tools Python package further enhances the accessibility and implementation of standardized workflows across research laboratories [28]. By adhering to this structured approach, researchers can leverage the full potential of GC-IMS for non-targeted screening and fingerprinting analysis in food research and quality control.

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) has emerged as a powerful, sensitive benchtop technique for the analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), generating characteristic molecular "fingerprints" of complex sample materials [29]. This two-dimensional separation technique first resolves compounds by their retention time in the GC column, followed by separation based on their collision cross-section and ion mobility in the drift tube [1]. The resulting data-rich spectra are particularly well-suited for authenticity analysis and quality control in various fields, especially food science [26] [29]. However, the full potential of GC-IMS is only realized when coupled with chemometric methods for multivariate data analysis. The integration of GC-IMS with pattern recognition techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) enables researchers to extract meaningful information from complex datasets, identify subtle patterns, and build robust classification models for sample discrimination [26] [30]. This combination provides a versatile platform for addressing challenges in geographical indication protection, food authentication, processing monitoring, and quality assessment across various scientific and industrial applications.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

GC-IMS Technical Fundamentals

The GC-IMS analytical process encompasses five distinct stages: sample introduction, compound separation, ion generation, ion separation, and ion detection [1]. In the initial stage, sample introduction can be enhanced with sensor-controlled sampling systems, particularly for challenging matrices like human breath, where parameters such as inhalation and exhalation must be differentiated using flow or CO2 sensors [31]. The separation process begins with gas chromatography, where compounds are partitioned between a stationary phase (typically a MXT-5 or SE-54 capillary column) and a mobile gas phase, resolving analytes based on their affinity for the stationary phase [26]. Following chromatographic separation, molecules enter the ionization chamber where they are ionized under atmospheric pressure, most commonly using a tritium source (6.5 KeV) [26]. The resulting ions then migrate through a drift tube under the influence of a weak electric field, separating based on their size, shape, and charge as they collide with drift gas molecules. Finally, ions reach the detector, generating a signal that is compiled into a two-dimensional plot with GC retention time on one axis and IMS drift time on the other [26] [1].

A significant advantage of GC-IMS over traditional detection methods like GC-MS lies in its operation at atmospheric pressure without requiring vacuum pumps [26]. This technical simplicity, combined with high sensitivity and the potential for portability, makes GC-IMS particularly valuable for on-site, real-time detection applications. Furthermore, GC-IMS demonstrates exceptional capability in distinguishing isomeric molecules, specifically ring-isomeric compounds, which often present challenges for other analytical techniques [26]. The selective detection among compounds of the same mass but different structures is possible because IMS separates ions based on mobilities rather than mass, providing an additional dimension of separation that enhances compound identification and differentiation [1].

Chemometric Methods for Pattern Recognition

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as an unsupervised dimensionality reduction technique that transforms the original variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components. This method is particularly valuable for exploratory data analysis, identifying natural clustering within samples, and detecting outliers that may indicate experimental errors or sample inconsistencies [26]. In the context of GC-IMS data, PCA helps visualize the maximum variance in the dataset, allowing researchers to observe inherent patterns without prior knowledge of sample classifications.

Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) represents a supervised classification method that maximizes the covariance between the independent variables (GC-IMS data) and the class membership. This technique is especially powerful for recognizing subtle differences between similar samples and building predictive models for classification purposes [26] [30]. The outstanding advantage of PLS-DA lies in its ability to handle multicollinear data where the number of variables exceeds the number of observations, a common scenario in GC-IMS datasets with numerous spectral data points.

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) is an unsupervised pattern recognition method that builds a hierarchy of clusters to illustrate data grouping based on similarity measures. This technique is particularly useful for visualizing relationships between samples through dendrograms, which graphically represent the progressive merging of clusters based on their spectral similarities [26]. HCA provides intuitive visual output that complements the dimensional reduction visualization of PCA.

Table 1: Key Chemometric Techniques and Their Applications in GC-IMS Analysis

| Technique | Type | Primary Function | Strengths | Common Applications in GC-IMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Unsupervised | Dimensionality reduction, exploratory data analysis | Identifies natural clustering, detects outliers, visualizes data structure | Initial data exploration, quality control, outlier detection [26] |

| PLS-DA | Supervised | Classification, prediction | Handles multicollinear data, identifies subtle differences between classes | Geographical origin authentication, quality grading, adulteration detection [26] [30] |

| HCA | Unsupervised | Cluster analysis, similarity visualization | Creates intuitive dendrograms, reveals hierarchical relationships | Sample classification, quality assessment, origin verification [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General Workflow for GC-IMS Coupled with Chemometric Analysis

The standard operating procedure for combining GC-IMS with chemometrics follows a systematic workflow that ensures reliable and reproducible results. The general workflow comprises four critical phases: sample collection and preparation, data acquisition using GC-IMS, data preprocessing and fusion, and finally chemometric analysis and model interpretation [26].

Sample Collection and Preparation Protocol

Sample Collection Strategy: The initial step in the workflow requires meticulous sample collection, where traceability, precision, and variety often outweigh sheer sample quantity [26]. Comprehensive metadata including geographical origin, harvest season, processing methods, and biological source must be documented, as this information equals category importance in classification accuracy. Samples with limited information cannot enhance classification models, and experimental errors or labeling mistakes can generate outliers that compromise model integrity [26]. For robust PLS-DA model building, research indicates that approximately 450 out of 997 samples may suffice for model training to achieve maximum average prediction accuracy, though this ratio depends on specific application requirements [30].

Sample Preparation Standards: For headspace analysis using GC-IMS, consistent sample preparation is crucial. Solid and semi-solid samples should be homogenized to increase surface area and ensure representative volatile compound release. Typical protocols involve weighing 1-5 grams of sample into 20 mL headspace vials. Liquid samples can be directly transferred to vials. Samples are then incubated at controlled temperatures (typically 40-80°C) for 10-30 minutes with constant agitation to facilitate volatile compound release into the headspace. The incubation temperature and time should be optimized for each sample matrix to ensure sufficient volatile compound concentration without generating artifacts from sample degradation [29].