GC-IMS vs. LC-MS: Choosing the Optimal Technique for Non-Volatile Food Compound Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for the analysis of non-volatile compounds in food.

GC-IMS vs. LC-MS: Choosing the Optimal Technique for Non-Volatile Food Compound Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for the analysis of non-volatile compounds in food. Aimed at researchers and scientists in food safety and development, we explore the fundamental principles, operational mechanisms, and ideal application domains for each technique. The content covers methodological workflows, real-world applications from recent studies, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and a direct comparative analysis of performance metrics including sensitivity, linear range, and matrix effects. The goal is to equip professionals with the knowledge to select the most appropriate analytical method for their specific food analysis challenges, from ensuring regulatory compliance to optimizing product flavor and quality.

Core Principles: Understanding GC-IMS and LC-MS Technologies

Fundamental Operating Principles of GC-IMS and LC-MS

Chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry represents a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, enabling the precise separation, identification, and quantification of chemical compounds within complex mixtures. Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) are two powerful platforms that serve complementary roles in analytical laboratories. While both techniques aim to separate and identify components in a sample, they achieve this through fundamentally different physical and chemical principles, making each suitable for distinct classes of analytes and applications.

GC-IMS combines the separation power of gas chromatography with the rapid detection capability of ion mobility spectrometry, creating a two-dimensional separation technique particularly effective for volatile organic compounds. In contrast, LC-MS couples liquid chromatography's ability to separate dissolved analytes with the sophisticated detection of mass spectrometry, making it indispensable for non-volatile, thermally labile, and higher molecular weight compounds. The selection between these platforms depends critically on the chemical properties of the target analytes, required sensitivity, and the specific analytical question being addressed. This guide provides a detailed comparison of their fundamental operating principles, technical capabilities, and practical applications in food analysis research.

Fundamental Operating Principles and Instrumentation

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) operates on a sequential separation principle where compounds are first separated by gas chromatography before undergoing a second separation dimension via ion mobility spectrometry. The process begins with sample vaporization, where the analytical sample is heated and introduced into the GC system using an inert carrier gas such as helium or nitrogen [1] [2]. Within the GC column, separation occurs based on two primary factors: the compound's volatility and its interaction with the stationary phase coating the column interior. As compounds elute from the GC column at different retention times, they immediately enter the IMS detection chamber.

In the IMS stage, molecules are ionized, typically using a radioactive source such as Tritium (³H) or Nickel-63 (⁶³Ni), which produces beta particles that ionize the carrier gas molecules. These ionized carrier gas molecules then transfer charge to analyte molecules through chemical ionization processes. Once ionized, the molecules are driven through a drift tube by a weak electric field under atmospheric pressure. During their drift, ions collide with neutral drift gas molecules (often purified air or nitrogen), separating based on their size, shape, and charge [3]. Compact ions experience fewer collisions and reach the detector faster than larger, more bulky ions with identical mass-to-charge ratios. The output is a drift time measurement that provides a collision cross-section (CCS) value, serving as a characteristic identifier for each compound.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) employs a liquid mobile phase to separate compounds followed by mass spectrometric detection. The process begins with sample dissolution in an appropriate solvent, which is then pumped at high pressure through an LC column containing a stationary phase. Separation occurs based on differential partitioning between the mobile and stationary phases, influenced by analytes' polarity, size, and specific chemical interactions [4] [1]. Critical LC parameters include column chemistry (e.g., C18 reverse-phase), mobile phase composition (gradient or isocratic), flow rate, and column temperature.

Following chromatographic separation, analytes enter the mass spectrometer through an interface that must efficiently transfer them from atmospheric pressure liquid phase to the high vacuum gas phase required for mass analysis. Electrospray ionization (ESI) is the most prevalent technique for this transition, where the LC effluent is nebulized into a fine spray of charged droplets under application of a high voltage [3]. As solvent evaporates, charged analyte molecules are released into the gas phase. Other ionization techniques like atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) or atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI) may be employed for less polar compounds.

The mass analyzer then separates ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Several mass analyzer types are utilized in LC-MS systems, including quadrupole, time-of-flight (TOF), Orbitrap, and ion trap instruments, each offering different trade-offs in mass accuracy, resolution, dynamic range, and acquisition speed [5] [6]. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) adds further analytical power by fragmenting selected ions and analyzing the product ions, providing structural information for compound identification.

Table 1: Fundamental Operating Principles Comparison

| Parameter | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Volatility & interaction with GC stationary phase | Polarity, size & chemical interactions |

| Mobile Phase | Inert gas (He, N₂) | Liquid solvents (methanol, acetonitrile, water) |

| Sample State | Volatile, thermally stable | Non-volatile, thermally labile |

| Ionization Method | Chemical ionization (radioactive source) | Electrospray ionization (ESI), APCI, APPI |

| Separation Dimension | Size, shape & charge (collision cross-section) | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) |

| Operating Pressure | Atmospheric pressure in IMS | High vacuum in mass analyzer |

| Detection Method | Drift time measurement | Mass-to-charge ratio measurement |

Technical Comparison and Performance Data

Analytical Capabilities and Limitations

The analytical capabilities of GC-IMS and LC-MS differ significantly due to their fundamental operating principles. GC-IMS excels in analyzing volatile organic compounds without requiring extensive sample preparation, offering rapid analysis times (typically seconds to minutes), high sensitivity (often parts-per-billion or better), and the ability to operate at atmospheric pressure, which simplifies instrument design [7]. The technique provides two-dimensional separation (retention time and drift time) that enhances peak capacity and helps resolve complex mixtures. However, GC-IMS is generally limited to volatile compounds or those that can be made volatile through derivatization, and the ionization process can be affected by moisture and competing compounds.

LC-MS demonstrates superior versatility in analyzing a broad spectrum of compounds, from small molecules to large proteins, with exceptional sensitivity and specificity. Modern LC-MS systems can achieve detection limits in the parts-per-trillion range, high mass accuracy (<1 ppm with high-resolution instruments), and the ability to provide structural information through MS/MS fragmentation [4] [8]. The technique's main limitations include higher instrument cost, more complex operation, potential for ion suppression effects in complex matrices, and the requirement for skilled operators. Additionally, LC-MS methods typically require more development time for method optimization compared to GC-IMS.

Quantitative Performance Characteristics

When evaluating quantitative performance, both techniques offer distinct advantages depending on the application requirements. GC-IMS provides excellent reproducibility for volatile compound analysis with a linear dynamic range typically spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude, making it suitable for flavor and fragrance analysis where relative abundance patterns are often more important than absolute quantification [7]. The technique's rapid analysis speed enables high-throughput screening applications.

LC-MS systems generally offer wider linear dynamic ranges (4-6 orders of magnitude) and superior quantitative precision, particularly when using triple quadrupole instruments in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode [4] [8]. This makes LC-MS the preferred technique for applications requiring precise quantification, such as pharmacokinetic studies, residue testing, and biomarker validation. The ability to use stable isotope-labeled internal standards in LC-MS further enhances quantitative accuracy by compensating for matrix effects and sample preparation variations.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Comparison

| Performance Characteristic | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) to parts-per-quadrillion (ppq) |

| Linear Dynamic Range | 2-3 orders of magnitude | 4-6 orders of magnitude |

| Mass Accuracy | Not applicable (measures drift time) | <1 ppm (high-resolution instruments) |

| Analysis Speed | Seconds to minutes | Minutes to tens of minutes |

| Sample Throughput | High | Moderate to high |

| Molecular Size Range | Typically <500 Da | Essentially unlimited (small molecules to proteins) |

| Quantitative Precision | Moderate (RSD 5-15%) | High (RSD 1-5%) |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Representative Experimental Workflows

GC-IMS Protocol for Food Volatile Profiling (adapted from cigar tobacco analysis [7]):

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 0.5 g of sample and place it in a 20 mL headspace vial. For solid samples, grinding to increase surface area improves volatile release.

- Headspace Incubation: Incubate the sample at 80°C for 30 minutes with agitation at 500 rpm to achieve equilibrium between the sample and headspace.

- GC Separation: Inject 500 µL of headspace gas in splitless mode onto a TG-WAX capillary column (or similar polar stationary phase). Maintain the column at 60°C using nitrogen carrier gas with a programmed flow rate.

- IMS Detection: Transfer eluting compounds to the IMS drift tube maintained at 45°C. Apply a uniform electric field (200-500 V/cm) across the drift region filled with purified air or nitrogen drift gas.

- Data Acquisition: Record ion currents at the Faraday detector with data collection typically lasting 20-35 minutes total run time.

- Data Analysis: Process 2D data (retention time vs. drift time) using specialized software to identify compounds based on retention index and reduced mobility values referenced to standards.

LC-MS Protocol for Non-Volatile Compound Analysis (adapted from honey authentication research [8]):

- Sample Extraction: Weigh 200 mg of sample into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Add 10 µL of internal standard solution (e.g., L-2-chlorophenylalanine at 10 ppm) and 1000 µL of extraction solvent (methanol:acetonitrile:water, 2:2:1 v/v/v).

- Extraction Procedure: Vortex mix for 1 minute, then ultrasonicate for 30 minutes at room temperature. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble material.

- Sample Concentration: Transfer supernatant and concentrate by vacuum centrifugation for 4 hours. Reconstitute the dried extract in 200 µL of 50% methanol solution.

- LC Separation: Inject filtrate onto appropriate LC column (e.g., C18 reverse-phase for non-polar compounds or HILIC for polar compounds). Use gradient elution with mobile phases A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) at flow rates of 0.2-0.4 mL/min.

- MS Detection: Ionize eluting compounds using electrospray ionization in positive or negative mode. Analyze using high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., Q-Exactive Orbitrap) with full scan data acquisition (m/z 100-1500) at resolution ≥70,000.

- Data Processing: Process raw data using software platforms (e.g., XCMS, Compound Discoverer) for peak picking, alignment, and compound identification against databases.

Application in Food Compound Analysis

The application strengths of GC-IMS and LC-MS in food analysis reflect their fundamental technical differences. GC-IMS finds particular utility in food quality control and authenticity assessment through volatile compound profiling. Representative applications include monitoring flavor and aroma compounds in beverages, detecting spoilage or oxidation volatiles in fats and oils, authenticating essential oils, and characterizing fermentation products in dairy and baked goods [7]. The technique's speed and sensitivity make it ideal for high-throughput screening applications where volatile patterns serve as fingerprints for origin, processing, or adulteration.

LC-MS has become indispensable for analyzing non-volatile food components and contaminants, including pesticides, veterinary drug residues, mycotoxins, natural toxins, food additives, and processing contaminants [4] [8]. Its application in foodomics—the comprehensive study of food constituents through omics approaches—has revolutionized understanding of how food composition impacts human health. LC-MS enables simultaneous determination of multiple analyte classes in a single analysis, provides structural elucidation for unknown compounds, and delivers the sensitivity required for regulatory compliance monitoring at strict maximum residue limits.

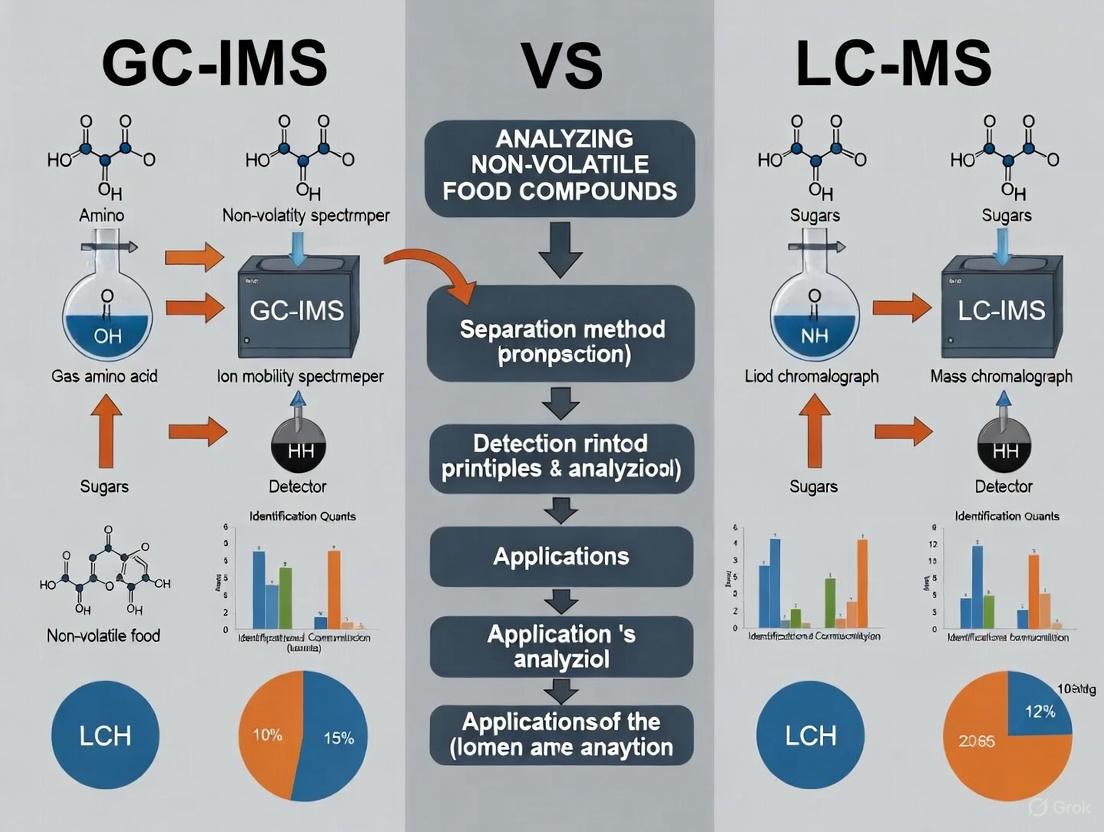

Diagram: Comparative experimental workflows for GC-IMS and LC-MS analyses

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of GC-IMS and LC-MS methodologies requires specific reagents, solvents, and consumables optimized for each technique. The following table details essential materials and their functions in analytical workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | GC-IMS Application | LC-MS Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier/ Mobile Phase | Transport medium for analyte separation | High-purity nitrogen or helium | HPLC-grade water, methanol, acetonitrile with modifiers (formic acid, ammonium acetate) |

| Internal Standards | Quantification reference & quality control | Deuterated volatile compounds | Stable isotope-labeled analogs of target analytes |

| Extraction Solvents | Compound isolation from matrix | Not typically used (headspace analysis) | Methanol, acetonitrile, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enhance volatility/ionization | Not always required | Sometimes used to improve ionization efficiency |

| Quality Control Materials | Method validation & performance verification | Certified reference materials for volatile compounds | Certified reference materials for target analytes |

| LC Columns | Chromatographic separation | Not applicable | C18, HILIC, phenyl, cyano stationary phases |

| GC Columns | Chromatographic separation | TG-WAX, DB-5, similar stationary phases | Not applicable |

| Syringe Filters | Sample clarification | Not typically used | 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm PTFE, nylon, or PES membranes |

| Vials/Containers | Sample storage & introduction | Headspace vials with crimp caps | LC vials with inserts |

GC-IMS and LC-MS represent complementary analytical platforms with distinct operating principles, capabilities, and application domains. GC-IMS provides rapid, sensitive analysis of volatile compounds with relatively simple operation and lower operating costs, making it ideal for flavor, fragrance, and volatile profiling applications. LC-MS offers unparalleled versatility in analyzing non-volatile and thermally labile compounds across an extensive molecular weight range, with superior quantitative capabilities and compound identification power through high-resolution mass measurement and MS/MS fragmentation.

The selection between these techniques should be guided by the specific analytical requirements, including target analyte properties, required sensitivity and specificity, sample throughput needs, and available resources. In many modern laboratories, both techniques coexist as complementary tools within comprehensive analytical workflows, each contributing unique information about sample composition. Ongoing technological advancements continue to enhance the performance, accessibility, and application range of both platforms, further solidifying their essential roles in food analysis, environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical research, and clinical diagnostics.

The choice between Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) represents a critical methodological crossroads in food compound analysis. These platforms differ fundamentally in their operational principles and, consequently, in their suitability for analyzing different classes of chemical compounds. The core distinction lies in their handling of compound volatility and thermal stability, which directly dictates their application scope within food research [9] [10]. GC-IMS requires that analytes be volatile and thermally stable enough to be vaporized without decomposition for analysis. In contrast, LC-MS separates compounds in a liquid phase at room temperature, making it uniquely suited for non-volatile and thermally labile molecules that would degrade under GC conditions [10]. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these techniques, framing their performance within the context of modern food safety and exposomics research, where comprehensive detection of contaminants is paramount [9].

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

Operational Workflows and Underlying Mechanisms

The analytical journey of a compound differs significantly between GC-IMS and LC-MS. The following diagram illustrates the core steps and critical decision points in each workflow, highlighting the fundamental differences that determine analyte suitability.

The fundamental technical differences between these platforms create a natural division in their application domains. GC-IMS relies on the vaporization of samples, a process that inherently restricts its use to compounds that can withstand the required heating without decomposing. Following vaporization, separation occurs in a gaseous mobile phase, and ionization is typically achieved using a radioactive source like Tritium or Nickel-63, which produces reactant ions that subsequently ionize the analyte molecules. The final separation in the drift tube is based on the ion's size, shape, and charge as it moves through a buffer gas under an electric field [9].

Conversely, LC-MS operates with a liquid mobile phase, completely circumventing the need for volatilization. The ionization process occurs at atmospheric pressure through techniques like Electrospray Ionization (ESI) or Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), which are exceptionally gentle and effective for a wide range of molecules, including large, polar, and thermally sensitive ones [11] [10]. The mass analyzer then separates ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), providing high specificity and the capability for structural elucidation through tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [11].

Direct Performance Comparison

The technical distinctions outlined above translate into clear, practical differences in performance, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Direct Technical Comparison of GC-IMS and LC-MS Platforms

| Performance Characteristic | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Analyte Properties | Volatile, thermally stable, low to medium molecular weight [9]. | Non-volatile, thermally labile, polar, high molecular weight [10]. |

| Sample Introduction | Requires vaporization (high temperature) [9]. | Dissolution in liquid solvent (ambient temperature) [10]. |

| Separation Mechanism | Gas chromatography (volatility) + Ion mobility (size/charge) [9]. | Liquid chromatography (polarity) + Mass spectrometry (m/z) [11]. |

| Common Ionization Sources | Radioactive β⁻ source (e.g., Tritium, Ni-63) [9]. | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [11] [10]. |

| Typical Analysis Speed | Very fast separation (seconds to minutes) [9]. | Slower separation (minutes to tens of minutes) [11]. |

| Inherent Strengths | High-speed analysis, portability for field use, sensitive to trace volatiles. | Exceptional molecular specificity and wide dynamic range. |

| Key Weaknesses | Limited to volatile compounds; may require derivatization; lower peak capacity than LC-MS. | Susceptible to matrix effects (ion suppression); complex data interpretation; higher instrumentation cost. |

Experimental Data and Application Protocols

Quantitative Performance in Food Analysis

Experimental data from food analysis applications underscores the practical implications of the fundamental differences between these techniques. The following table compiles representative performance metrics for each platform when analyzing different classes of food compounds.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Food Compound Analysis

| Analyte Class | Platform | Example Compounds | Reported Limits of Detection (LOD) | Key Applications in Food |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pesticides | LC-MS/MS [10] | Polar pesticides, carbamates, metabolites | Low to sub-ppb (μg/kg) levels [10] | Multiresidue analysis in fruits, vegetables, grains [10] |

| Veterinary Drugs | LC-MS/MS [11] | Antibiotics, tranquilizers | Not specified in search results | Monitoring residues in meat, milk, honey [9] [11] |

| Mycotoxins | LC-HRMS [9] | Aflatoxins, ochratoxin A | Not specified in search results | Screening in cereals, nuts, spices [9] |

| Volatile Flavors/Aromas | GC-IMS [9] | Esters, aldehydes, terpenes | Not specified in search results | Food authenticity, flavor profiling, spoilage detection [9] |

| Elemental Species | GC-ICP-MS [12] | Organotin, methylmercury, selenomethionine | Attogram (10⁻¹⁸) to femtogram (10⁻¹⁵) levels [12] | Speciation analysis in seafood, supplements [13] [12] |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: LC-MS/MS for Multiresidue Pesticide Analysis

This protocol is widely used for monitoring polar pesticide residues in food commodities and exemplifies a bottom-up exposomics approach by characterizing the external food exposome [9] [10].

Sample Preparation (QuEChERSER Mega-Method):

- Extraction: Homogenize 10 g of sample with 10 mL acetonitrile in a centrifuge tube. Add a salt mixture (e.g., 4 g MgSO₄, 1 g NaCl, 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate sesquihydrate, 1 g trisodium citrate dihydrate) and shake vigorously. Centrifuge to separate phases [9].

- Clean-up: Transfer an aliquot of the extract to a dispersive-SPE (d-SPE) tube containing sorbents like primary secondary amine (PSA), C18, and MgSO₄. Shake and centrifuge. The purified extract is diluted and injected into the LC-MS/MS system [9] [10].

LC Separation:

- Technique: Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC).

- Column: C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 100 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 μm particle size).

- Mobile Phase: (A) Water and (B) Methanol or Acetonitrile, both with additives like 0.1% formic acid or 5 mM ammonium formate.

- Gradient: Typically from 5-95% B over 10-20 minutes to separate compounds of varying polarity [10].

MS Analysis:

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), predominantly in positive mode.

- Mass Analyzer: Triple quadrupole (QqQ) operating in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode.

- Data Acquisition: For each target pesticide, two specific precursor ion → product ion transitions are monitored for high-confidence identification and quantification [10].

Protocol 2: GC-ICP-MS for Elemental Speciation

This protocol demonstrates a highly specialized application of GC for analyzing volatile organometallic compounds, crucial for assessing the toxicity of elements like mercury and tin in food [13] [12] [14].

Sample Preparation (Derivatization):

- Extraction: For methylmercury in fish, the sample is typically digested with an acid (e.g., HCl) and then extracted into an organic solvent like toluene.

- Derivatization: The extract is treated with a tetraalkylborate reagent (e.g., sodium tetraethylborate) in an aqueous buffer. This reaction converts ionic organometallic species (e.g., MeHg⁺) into volatile, GC-amenable derivatives (e.g., MeHgEt) [12].

GC Separation:

- Technique: Capillary Gas Chromatography.

- Column: Non-polar or mid-polar capillary column (e.g., DB-5, 30 m x 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness).

- Carrier Gas: Helium.

- Temperature Program: Ramped from a low initial temperature (e.g., 50°C) to a high final temperature (e.g., 280°C) to separate the derivatized species [13] [12].

ICP-MS Detection:

- Interface: The GC effluent is directly transferred to the ICP torch via a heated transfer line.

- Detection: The ICP-MS is tuned for the specific target element (e.g., Hg, Sn, Se). The detection limits are exceptionally low (attogram to femtogram levels) due to the high ionization efficiency and the absence of a liquid solvent [12] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the protocols above requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for food exposome analysis.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Food Exposome Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| QuEChERSER Kits | Sample preparation for multi-class contaminant analysis [9]. | Pre-weighed salt and sorbent kits for efficient extraction and clean-up. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green, sustainable extraction solvents [9] [15]. | Biodegradable, low toxicity, tunable extraction properties. |

| UHPLC C18 Columns | High-resolution chromatographic separation for LC-MS [16] [10]. | Sub-2μm particles for high efficiency and fast analysis. |

| Tetraalkylborate Reagents | Derivatization for GC-based speciation analysis [12]. | Converts non-volatile metal species into volatile derivatives. |

| ESI & APCI Reagents | Mobile phase additives for LC-MS ionization [11] [10]. | Volatile acids (formic, acetic) and buffers (ammonium formate/acetate). |

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Accurate quantification in mass spectrometry [12]. | Corrects for matrix effects and recovery losses; essential for IDA. |

Integrated Workflow for Food Exposomics

Modern exposomics research often requires integrating multiple analytical strategies to comprehensively characterize exposure from source to biological outcome. The following diagram maps how GC- and LC-based platforms fit into a holistic "meet-in-the-middle" workflow, connecting external exposure sources with internal biological effects.

This workflow demonstrates the complementary nature of analytical techniques. The Bottom-Up Approach starts with the analysis of food sources using both GC-IMS (for volatile compounds) and LC-MS (for non-volatile residues and contaminants) to characterize the external exposome and identify potential exposure sources [9]. Simultaneously, the Top-Down Approach analyzes biological samples from individuals using primarily LC-HRMS to measure the internal exposome, including biomarkers of effect that reflect early biological responses [9] [17]. These two streams of data are integrated in "Meet-in-the-Middle" Approaches, which identify intermediate biomarkers that are causally linked to both exposure and health outcomes. This integration strengthens causal inference and helps validate the mechanistic links outlined in Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs), providing a systems-level understanding of how chemicals in food impact health [9].

The selection between GC-IMS and LC-MS is not a matter of one technique being superior to the other, but rather a strategic decision based on the physicochemical properties of the target analytes and the specific research questions at hand. GC-IMS excels in the rapid, sensitive analysis of volatile, thermally stable compounds, finding its niche in flavor profiling, authenticity, and spoilage studies. LC-MS is the undisputed platform for non-volatile, thermally labile, and polar compounds, making it indispensable for multiresidue analysis of pesticides, veterinary drugs, mycotoxins, and other contaminants in food. As the field of food exposomics advances, the trend is not toward the dominance of a single platform, but toward the development of high-throughput, multi-platform approaches [9]. The integration of data from GC-HRMS, LC-HRMS, and IMS within a holistic framework provides the most comprehensive picture of the food exposome, enabling researchers to trace contaminants from the food supply into the human body and link these exposures to biological effects, ultimately supporting better public health interventions and personalized healthcare strategies [9] [17].

The analysis of food compounds, particularly non-volatile substances, is fundamental to ensuring food safety, authenticity, and quality. Within this field, Gas Chromatography coupled to Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) represent two powerful but fundamentally different analytical approaches [18] [11]. GC-IMS is a highly sensitive technique that excels in the separation and detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and is renowned for its robustness and ease of use [19]. In contrast, LC-MS has become a cornerstone technique for the analysis of non-volatile and thermally labile compounds, offering high sensitivity, selectivity, and the ability to provide structural information on a wide range of molecules [11] [20]. The core distinction lies in the analytes they are best suited to investigate: GC-IMS focuses on volatile aroma and flavor profiles, while LC-MS targets a broader spectrum of non-volatile compounds such as lipids, pigments, proteins, and residues. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two technologies, focusing on their principles, performance, and application in food analysis to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their specific analytical challenges.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS)

GC-IMS is a two-dimensional technique that combines the separation power of Gas Chromatography with the sensitive, fast detection of Ion Mobility Spectrometry. The process begins with the sample being vaporized and introduced into the GC system. Volatile compounds are separated as they travel through a capillary column based on their partitioning between a gaseous mobile phase and a stationary liquid phase, which is influenced by the compounds' boiling points and polarities [21] [19]. The separated analytes then enter the IMS detector, where they are ionized, typically by a radioactive source such as Tritium (³H) or Nickel-63 (⁶³Ni), which generates reactant ions in a drift gas [19]. The resulting ionized molecules are driven by an electric field through a drift tube filled with a counter-flowing inert drift gas (often nitrogen). Separation in the IMS dimension occurs based on the ion's collision cross section (CCS), which is a measure of its size, shape, and charge as it collides with the drift gas molecules [18] [19]. Ions with larger CCS values experience more collisions and take longer to reach the detector, resulting in a longer drift time. The final output is a two-dimensional plot with GC retention time on one axis and IMS drift time on the other, allowing for highly resolved analysis of complex volatile mixtures.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LC-MS couples the superior separation capabilities of Liquid Chromatography for non-volatile and thermally unstable compounds with the powerful detection and identification capabilities of Mass Spectrometry. In the LC stage, the sample is dissolved in a liquid solvent and separated based on the differential distribution of analytes between a liquid mobile phase and a stationary phase packed inside a column [22]. The separation mechanism can be reversed-phase, normal-phase, or ion-exchange, among others, providing great flexibility. After separation, the analytes are introduced into the mass spectrometer, which requires an interface to remove the solvent and ionize the molecules. Common ionization techniques include Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), which are suitable for a wide range of compounds, from small molecules to large biomolecules [11] [20]. The ionized molecules are then analyzed in the mass spectrometer based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Modern LC-MS systems employ various mass analyzers—such as quadrupoles (Q), time-of-flight (ToF), Orbitrap, and ion traps—often in hybrid configurations (e.g., Q-TOF, Q-Orbitrap) to provide high resolution, accurate mass measurement, and tandem MS (MS/MS) capabilities for structural elucidation [11] [20]. The evolution from High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) has further enhanced performance through the use of sub-2 µm particles and systems capable of withstanding pressures up to 1,500 bar, resulting in faster analysis and higher resolution [22].

Table 1: Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

| Feature | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Mechanism | Partitioning between gas mobile phase and liquid stationary phase [21] | Partitioning between liquid mobile phase and solid stationary phase [22] |

| Detection Principle | Ion mobility (Collision Cross Section, CCS) in a drift gas under electric field [18] [19] | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) in a high vacuum under electric/magnetic fields [11] [20] |

| Key Measured Parameter | Drift time (converted to reduced mobility, K₀, or CCS) [18] | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and signal intensity [20] |

| Ionization Method | Atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (e.g., β-emitter like Tritium) [19] | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [11] [20] |

| Typical Analyte State | Volatile, thermally stable | Non-volatile, semi-volatile, thermally labile |

Figure 1: GC-IMS Analytical Workflow. The process involves headspace sampling, GC separation, ionization, IMS drift separation, and detection to produce a 2D data output.

Figure 2: LC-MS Analytical Workflow. The process involves liquid sample injection, LC separation, ionization, mass analysis, and detection to produce retention time and m/z data.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance characteristics of GC-IMS and LC-MS differ significantly, reflecting their distinct technological foundations and application domains. GC-IMS operates at atmospheric pressure, contributing to its simpler design and lower operational costs, while LC-MS requires high vacuum systems, adding to its complexity and expense [19]. In terms of sensitivity, GC-IMS is capable of detecting compounds at parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels, making it exceptionally suited for trace volatile analysis [19]. LC-MS also offers high sensitivity, often reaching picogram (pg) to femtogram (fg) levels, which is essential for quantifying trace-level contaminants or biomarkers in complex matrices [11]. The dynamic range of GC-IMS can be limited for some compounds due to the formation of dimers and clusters at higher concentrations, whereas LC-MS, particularly with APCI, can achieve a wide dynamic range spanning 4-5 orders of magnitude [19] [20]. A key advantage of LC-MS is its superior compound identification power, enabled by high-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) measurements and tandem MS, which provides detailed structural information [11]. GC-IMS identification is based on retention time and a compound's collision cross section (CCS), and while CCS is a reproducible identifier, it provides less structural detail than a mass spectrum [18]. Commercial databases for GC-IMS are also less established compared to the extensive mass spectral libraries available for LC-MS [19].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Typical Metrics

| Performance Metric | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | ppb to ppt levels [19] | pg to fg levels [11] |

| Analysis Speed | Seconds to minutes for IMS separation [19] | Minutes to tens of minutes (faster with UHPLC) [22] |

| Operational Pressure | Atmospheric pressure [19] | High pressure (up to 1500 bar for UHPLC) [22] |

| Dynamic Range | Can be limited by clustering [19] | Wide (4-5 orders of magnitude) [20] |

| Identification Power | Retention index and CCS; limited fragmentation [18] | Accurate mass, isotopic patterns, MS/MS fragmentation [11] [20] |

| Key Qualitative Output | Reduced ion mobility (K₀) / Collision Cross Section (CCS) [18] | Accurate mass, fragment mass spectrum, molecular formula [11] |

Application-Based Performance in Food Analysis

Experimental data from food analysis research highlights the complementary nature of these techniques. In a study on jujube leaf tea processing, GC-IMS and LC-MS were used in parallel to profile volatile and non-volatile metabolites, respectively. LC-MS successfully identified 468 non-volatile metabolites, including lipids, amino acids, and flavonoids, which significantly increased after processing [23]. Conversely, GC-IMS detected 52 volatile metabolites, revealing that aldehydes and ketones increased while some esters decreased, with the flavor profile shifting from eugenol in fresh leaves to (E)-2-Hexenal in the processed tea [23]. This demonstrates LC-MS's depth in profiling nutritive non-volatiles and GC-IMS's strength in tracking aroma-relevant volatiles.

In kimchi fermentation research, an integrated approach using LC-MS/MS and GC-IMS enabled stage-specific quality assessment. LC-MS/MS effectively quantified non-volatile markers like lactic acid, citric acid, and malic acid, which decreased sharply by week 2, clearly defining the initial fermentation stage [24]. However, non-volatile analysis was limited in differentiating later stages. Here, GC-IMS complemented by tracking volatile compounds such as 1-hexanol and 2,3-pentanedione, which remained stable during the optimal ripening period (weeks 2-4) and shifted significantly upon over-ripening (after week 6) [24]. This synergy provided a more complete picture of the fermentation process than either technique alone.

Table 3: Application Overview in Food Analysis

| Application Area | GC-IMS (Typical Analytes) | LC-MS (Typical Analytes) |

|---|---|---|

| Food Authentication/Adulteration | VOC fingerprints, aroma profiles [18] [19] | Triacylglycerol profiles, pigment patterns, polyphenols [20] |

| Process Control | Monitoring fermentation VOCs (alcohols, aldehydes, ketones) [23] [24] | Organic acids, amino acids, sugars, bioactive compounds [24] [11] |

| Safety & Contaminant Analysis | Off-odors, microbial spoilage VOCs [19] | Pesticide residues, veterinary drugs, mycotoxins [11] [20] |

| Flavor & Aroma Research | Key odorants, essential oils [23] [19] | Taste-active compounds, precursors to flavors [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Representative GC-IMS Protocol for Fermentation Monitoring

The following protocol, adapted from kimchi fermentation studies, outlines the typical steps for using GC-IMS to monitor volatile compounds during a fermentation process [24].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Homogenization: The food sample (e.g., kimchi) is homogenized to ensure a representative aliquot.

- Headspace Vial Incubation: A precise weight (e.g., 2.0 g) of the homogenized sample is placed into a headspace vial. The vial is sealed immediately with a crimp cap.

- Incubation: The sealed vial is incubated in a thermostatting block or autosampler oven. The incubation temperature and time must be rigorously controlled. For kimchi analysis, a temperature of 30 °C is recommended to avoid distortion of the VOC profile, as elevated temperatures can release non-representative volatiles [24].

- Equilibration: The sample is typically equilibrated for 10-15 minutes at the set temperature to allow the volatile compounds to partition into the headspace.

2. GC-IMS Analysis:

- Injection: A defined volume (e.g., 500 µL) of the headspace is automatically injected into the GC-IMS system via a heated syringe.

- GC Separation:

- Column: A moderately polar capillary column (e.g., DB-624, VOCOL, or similar).

- Carrier Gas: High-purity nitrogen or helium.

- Oven Program: The GC oven temperature is ramped. An example program is: hold at 40°C for 2 minutes, ramp to 100°C at 5°C/min, then ramp to 240°C at 20°C/min, and hold for 2 minutes [24].

- IMS Detection:

- Drift Tube: Temperature typically set between 30-50°C.

- Drift Gas: High-purity nitrogen, set to a specific flow rate.

- Electric Field: A constant, uniform electric field is applied along the drift tube (e.g., 400 V/cm).

3. Data Processing:

- Peak Picking and Alignment: Software is used to pick peaks from the 2D chromatogram (retention time vs. drift time) and align them across multiple samples.

- Library Matching: Peaks are tentatively identified by matching their retention time and CCS (or reduced mobility K₀) against a reference library, if available.

- Statistical Analysis: The resulting peak volume or intensity table is subjected to statistical analysis (e.g., PCA, OPLS-DA) to identify VOCs that differentiate sample groups.

Representative LC-MS/MS Protocol for Non-Volatile Metabolite Profiling

This protocol for analyzing non-volatile compounds in plant materials like jujube leaves is based on published methodologies [23] [11].

1. Sample Preparation and Extraction:

- Lyophilization and Grinding: The sample is flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried. The dried material is then ground into a fine, homogeneous powder.

- Weighing: A precise amount (e.g., 50 mg ± 0.1 mg) of the powdered sample is weighed into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Extraction: A suitable extraction solvent (e.g., 400 µL of methanol:water = 4:1, v/v) containing an internal standard (e.g., 0.02 mg/mL L-2-chlorophenylalanine) is added to the tube.

- Homogenization: The mixture is homogenized using a ball mill or vortex mixer.

- Sonication and Centrifugation: The sample is subjected to low-temperature ultrasonic extraction for 30 minutes, then incubated at -20°C for 30 minutes. It is then centrifuged at high speed (e.g., 13,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes) to pellet insoluble debris.

- Supernatant Collection: The supernatant is carefully transferred to an LC vial for analysis. A quality control (QC) sample is prepared by pooling aliquots from all samples.

2. LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- LC System: UHPLC system is preferred for its high resolution and speed.

- Column: A reversed-phase column (e.g., ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3, 100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm) is maintained at a constant temperature (e.g., 40°C).

- Mobile Phase: Typically a binary gradient of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both modified with 0.1% formic acid.

- Gradient Program: An example gradient for metabolomics is: 0-2 min, 2% B; 2-15 min, 2% to 100% B; 15-17 min, 100% B; 17-17.1 min, 100% to 2% B; 17.1-20 min, 2% B for re-equilibration [23].

- Injection Volume: 1-5 µL.

- MS Detection:

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative ion modes.

- Mass Analyzer: A high-resolution mass spectrometer like a Q-Orbitrap or Q-TOF.

- Acquisition Mode: Full-scan MS (e.g., m/z 70-1050) at high resolution (e.g., 70,000 FWHM) for untargeted profiling, followed by data-dependent MS/MS scans for compound identification.

3. Data Processing:

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Software is used for peak picking, deisotoping, and alignment across all samples.

- Compound Identification: Metabolites are identified by matching accurate mass and MS/MS spectra against commercial and public databases (e.g., HMDB, MassBank).

- Multivariate Statistics: The processed data matrix is analyzed using PCA and OPLS-DA to identify significant metabolites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Consumables for Chromatography Analysis

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Tritium (³H) Ionization Source | Beta emitter used in GC-IMS to ionize analyte molecules via reactant ion formation in the drift gas [19]. | Used in commercially available benchtop GC-IMS systems for food flavor analysis [19]. |

| High-Purity Nitrogen Gas | Serves as the drift gas in IMS, separating ions based on collisions; also used as a carrier or make-up gas in GC [19]. | Standard drift and carrier gas for GC-IMS operation [19]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fiber | A sample preparation tool for extracting and concentrating volatile compounds from headspace or liquid samples prior to GC analysis [19]. | Used for VOC profiling from complex sample matrices in combination with GC-IMS [19]. |

| UHPLC Column (e.g., C18, 1.8 µm) | The stationary phase for separating non-volatile compounds. Sub-2 µm particles provide high efficiency and resolution under high pressure [22]. | ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column used for separating non-volatile metabolites from jujube leaf tea [23]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Internal Standards (Isotope-Labeled) | Compounds with stable isotope labels (e.g., ¹³C, ²H) used to correct for analyte loss during preparation and ion suppression/enhancement in the MS source [20]. | L-2-chlorophenylalanine used as an internal standard in LC-MS-based metabolomics of jujube leaves [23]. |

GC-IMS and LC-MS are powerful yet distinct analytical techniques that serve different, often complementary, purposes in food analysis. GC-IMS excels in the rapid, sensitive analysis of volatile compounds, making it an ideal tool for aroma profiling, fermentation monitoring, and non-targeted fingerprinting with minimal sample preparation [23] [24] [19]. Its operational simplicity and lack of requirement for a high vacuum make it robust and relatively easy to maintain. LC-MS, on the other hand, is the undisputed gold standard for the analysis of non-volatile and thermally labile compounds, providing unparalleled selectivity, sensitivity, and the ability to confidently identify and quantify a vast range of analytes, from pesticides and veterinary drugs to lipids and metabolites [11] [20]. The choice between these two technologies is not a matter of superiority but of application. For research focused on odor, flavor, or rapid process monitoring of volatiles, GC-IMS is an excellent choice. For comprehensive analysis of food composition, safety contaminants, nutritive non-volatiles, and in-depth metabolomic studies, LC-MS is the more appropriate and powerful tool. As demonstrated in several studies, an integrated approach that leverages the strengths of both platforms can provide the most holistic understanding of food quality and chemistry [23] [24].

The Role of Ion Mobility Spectrometry as an Additional Separation Dimension

The analysis of non-volatile compounds in food presents significant challenges due to the complexity of matrices and the presence of isobaric and isomeric substances that are difficult to separate and identify. Traditional analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) have been the gold standard in food analysis, yet they face limitations in separating compounds with similar structural characteristics. In recent years, ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) has emerged as a powerful technology that adds a new separation dimension to these conventional methods. IMS separates ionized molecules in the gas phase based on their size, shape, and charge under the influence of an electric field, providing an additional molecular descriptor—the collision cross section (CCS)—which represents the averaged momentum transfer impact area of the ion [25] [18].

The integration of IMS into established chromatographic and spectrometric workflows creates a multidimensional separation platform that significantly enhances peak capacity, selectivity, and confidence in compound identification. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of two prominent hyphenated techniques: gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), with a specific focus on their application for non-volatile food compound analysis. By examining instrumental principles, performance characteristics, and practical applications through recent experimental studies, this article aims to equip researchers and analysts with the data necessary to select appropriate methodologies for their specific food analysis challenges.

Fundamental Principles: IMS as a Complementary Separation Technique

Ion mobility spectrometry operates on the principle of separating ionized molecules in the gas phase as they drift through a buffer gas under the influence of an electric field. The drift time required for ions to traverse the mobility cell is directly related to their rotationally averaged collision cross section (CCS), a molecular parameter that provides valuable information about the three-dimensional structure of ions [25] [18]. The reduced mobility (K₀), normalized to standard temperature and pressure conditions, allows for comparison between different experimental setups and is calculated according to the following equation:

K₀ = K × (p/p₀) × (T₀/T)

Where K is the measured mobility, p is pressure, T is temperature, and the subscript 0 denotes standard conditions [25].

Several IMS technologies are commercially available, each with distinct operational principles and applications. Drift Tube IMS (DTIMS) and Travelling Wave IMS (TWIMS) are time-dispersive techniques, while High-Field Asymmetric Waveform IMS (FAIMS) and Differential IMS (DIMS) represent space-dispersive technologies. Trapped IMS (TIMS) employs a trapping mechanism where ions are held in place against a gas flow by an electric field and released based on their mobility [18]. The CCS values obtained through IMS provide complementary information to mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and retention time, enabling more confident compound identification, particularly for isobaric and isomeric compounds that are challenging to distinguish using conventional LC-MS or GC-MS alone [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Major IMS Technologies

| IMS Technology | Separation Principle | CCS Measurement | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drift Tube IMS (DTIMS) | Constant electric field in drift tube | Direct measurement | Primary method for CCS determination |

| Travelling Wave IMS (TWIMS) | Moving potential waves | Requires calibration | High resolution capabilities |

| Field Asymmetric IMS (FAIMS) | Asymmetric waveform at high field | Not applicable | High sensitivity for specific compound classes |

| Trapped IMS (TIMS) | Electric field + gas flow counterbalance | Requires calibration | Compact design, high resolution |

When hyphenated with separation techniques like GC or LC and detection systems like MS, IMS adds a valuable separation dimension that occurs between the chromatographic separation (typically requiring seconds to minutes) and mass spectrometric detection (occurring in microseconds). This orthogonal separation approach significantly increases the peak capacity of analytical methods, enabling more effective analysis of complex food matrices where compounds of interest are often present at trace levels amidst numerous interfering components [25] [18].

Figure 1: Analytical Workflow with IMS as an Additional Separation Dimension

Comparative Analysis: GC-IMS versus LC-MS for Food Compound Analysis

Technical Principles and Instrumentation

GC-IMS combines the separation power of gas chromatography with the fast response and high sensitivity of ion mobility spectrometry. In this configuration, GC first separates volatile and semi-volatile compounds based on their partitioning between a stationary phase and carrier gas, followed by IMS separation based on ion mobility in the gas phase. The technique is particularly well-suited for volatile organic compound (VOC) analysis and requires minimal sample preparation, often employing simple headspace injection [26] [27]. GC-IMS operates at atmospheric pressure, uses nitrogen as drift gas, and offers advantages in terms of portability, speed, and cost-effectiveness compared to GC-MS. Recent technological advances have enabled the development of miniaturized GC-IMS systems suitable for on-site analysis and process monitoring [27].

In contrast, LC-MS combines liquid chromatography's separation of compounds dissolved in liquid solvent with mass spectrometry's detection based on mass-to-charge ratio. LC is ideal for non-volatile, thermally labile, and high molecular weight compounds that are not amenable to GC analysis. The hyphenation with IMS typically occurs between LC and MS, creating LC-IMS-MS workflows that provide three separation dimensions: retention time, collision cross section, and mass-to-charge ratio [25] [18]. This configuration is particularly powerful for complex mixture analysis as it provides multiple orthogonal parameters for compound identification. The CCS values obtained through LC-IMS-MS serve as additional molecular descriptors that are highly reproducible across laboratories and instruments, facilitating the creation of CCS databases for compound identification [25].

Performance Comparison in Food Analysis Applications

Experimental studies directly comparing GC-IMS and LC-MS for food analysis reveal distinct performance characteristics and complementary applications. A comprehensive study on cigar tobacco leaves from different regions employed both techniques to characterize volatile and non-volatile compounds. GC-IMS analysis identified 109 volatile compounds, including 26 esters, 17 aldehydes, 14 alcohols, 14 ketones, and various other compounds, and successfully differentiated tobacco samples based on geographical origin using specific marker compounds [26] [7]. Meanwhile, LC-MS analysis provided comprehensive coverage of non-volatile metabolites and enabled the identification of key metabolic pathways, including amino acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism, which contribute to flavor formation in tobacco leaves [26].

Similarly, a study on jujube leaves processed into tea utilized GC-IMS, GC-MS, and LC-MS to comprehensively analyze metabolic changes. LC-MS identified 468 non-volatile metabolites, while GC-IMS and GC-MS detected 52 and 24 volatile metabolites, respectively. The integration of these techniques revealed that amino acids and lipids were closely linked to the formation of volatile metabolites, providing insights into the biochemical transformations occurring during tea processing [23].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GC-IMS and LC-MS in Food Analysis Applications

| Parameter | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Compound Classes | Volatile and semi-volatile compounds | Non-volatile, thermally labile, polar compounds |

| Separation Dimensions | Retention time + Collision cross section | Retention time + Mass-to-charge ratio (+ Collision cross section with IMS) |

| Detection Limits | ppt to ppb range for many VOCs | ppb to ppt range for most analytes |

| Analysis Time | Fast (minutes), real-time capability possible | Moderate to long (typically 10-60 minutes) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (often headspace injection) | Typically required (extraction, purification) |

| Identification Power | Moderate (library matching for known compounds) | High (exact mass, fragmentation patterns) |

| Quantitation Capability | Good linear range for targeted compounds | Excellent sensitivity and dynamic range |

| Portability | Miniaturized systems available for on-site analysis | Laboratory-based systems |

Analytical Workflows and Methodologies

The experimental workflows for GC-IMS and LC-MS analyses differ significantly in sample preparation, separation mechanisms, and detection schemes. The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflows for both techniques, highlighting key steps where IMS enhances separation capabilities.

Figure 2: Comparative Workflows of GC-IMS and LC-IMS-MS Techniques

Experimental Protocols for Food Analysis

GC-IMS Protocol for Volatile Compound Analysis

Based on the cigar tobacco study [26] [7], the standard GC-IMS protocol involves:

Sample Preparation:

- Grind samples into powder using liquid nitrogen

- Weigh 0.5 g of sample into a 20 mL headspace vial

- Seal vial and incubate at 80°C with 500 rpm agitation for 30 minutes

GC-IMS Parameters:

- GC Column: TG-WAX (or similar weakly polar column)

- Injection Temperature: 85°C

- Carrier Gas: High-purity nitrogen (≥99.999%)

- Injection Volume: 500 µL in splitless mode

- Column Temperature: 60°C (isothermal)

- Analysis Time: 35 minutes

- IMS Drift Tube Temperature: 45°C

- Drift Gas: Nitrogen

Data Analysis:

- Use proprietary software (e.g., LAV from G.A.S. or similar)

- Generate topographic plots (retention time vs. drift time vs. intensity)

- Perform library matching against commercial or in-house databases

- Apply multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, OPLS-DA) for sample differentiation

LC-MS Protocol for Non-Volatile Compound Analysis

The non-targeted metabolomics protocol from the same study [26] [7] includes:

Sample Preparation:

- Grind samples (200 mg) under liquid nitrogen

- Add 10 µL internal standard (e.g., L-2-chlorophenylalanine at 10 ppm)

- Extract with 1000 µL extraction solution (methanol/acetonitrile/water, 2:2:1)

- Vortex for 1 minute, ultrasonicate for 30 minutes

- Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C

- Collect supernatant and concentrate by vacuum centrifugation

- Reconstitute in 200 µL of 50% methanol solution

- Filter through membrane before LC-MS analysis

LC-MS Parameters:

- LC System: HPLC or UHPLC with C18 column

- Mobile Phase: Water with 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B)

- Gradient Elution: Typically 5-95% B over 20-30 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.3-0.4 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40°C

- Injection Volume: 2-5 µL

- Mass Spectrometer: High-resolution instrument (Orbitrap, Q-TOF)

- Ionization: ESI in positive and negative modes

- Mass Range: Typically 50-1500 m/z

Data Processing:

- Use software such as XCMS, MS-DIAL, or proprietary platforms

- Perform peak picking, alignment, and normalization

- Identify compounds using databases (HMDB, KEGG, MassBank)

- Conduct pathway analysis (KEGG, MetaboAnalyst)

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of GC-IMS and LC-MS methods requires specific reagents, standards, and materials optimized for each technique. The following table summarizes key research solutions and their applications in food compound analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IMS-Based Food Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | GC-IMS | LC-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | Quantitation and quality control | Deuterated VOCs, 1,3-dichlorobenzene | L-2-chlorophenylalanine, stable isotope-labeled compounds |

| Extraction Solvents | Compound extraction from food matrices | Often not required (headspace) | Methanol, acetonitrile, water mixtures (typically 2:2:1) |

| Mobile Phase Additives | LC separation and ionization enhancement | Not applicable | Formic acid, ammonium acetate, ammonium formate |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enhancing volatility or detectability | Sometimes used for less volatile compounds | Sometimes used for specific compound classes |

| Quality Control Materials | System suitability and performance verification | Standard mixtures of known VOCs | Quality control samples from pooled extracts |

| Calibration Compounds | CCS value determination and system calibration | Ketones (e.g., 2-butanone, 2-pentanone) | Tunable calibration mixtures (e.g., Agilent Tuning Mix) |

| Drift Gases | IMS separation medium | Nitrogen (high purity) | Nitrogen or carbon dioxide (high purity) |

Analytical Applications in Food Research

Food Authentication and Origin Verification

The combination of chromatographic separation with IMS detection has proven particularly valuable for food authentication and origin verification. In the cigar tobacco study [26] [7], GC-IMS successfully differentiated leaves from ten different geographical regions in Yunnan, China, based on their volatile profiles. Specific marker compounds included 2,3-diethyl-6-methylpyrazine and phenylacetaldehyde in BS-Y1-1 samples, 3-methyl-1-pentanol in PE-Y2 samples, and butan-2-one in WS-Y38 samples. Similarly, LC-MS analysis provided complementary information on non-volatile metabolites that contributed to regional differentiation through distinct metabolic pathways.

A study on Auricularia auricula mushrooms from different regions [28] employed UPLC-MS/MS and GC-IMS to establish metabolite fingerprints that enabled clear geographical discrimination. The GC-IMS analysis revealed 64 volatile compounds, including acids, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, and ketones, with distinct abundance patterns between samples from Heilongjiang and Shaanxi provinces. The LC-MS analysis identified 881 metabolites, with 39 showing significant differences between regions. Multivariate statistical analysis (PCA and OPLS-DA) successfully differentiated samples based on their geographical origin, demonstrating the power of combining volatile and non-volatile compound analysis for authentication purposes.

Process Monitoring and Quality Control

IMS-based techniques have shown significant utility in monitoring food processing and quality control. The jujube leaf tea study [23] comprehensively analyzed metabolic changes during tea processing using LC-MS, GC-IMS, and GC-MS. LC-MS identified 468 non-volatile metabolites, with 109 showing significant changes after processing. Most lipids and lipid-like molecules, organic acids, amino acids, and flavonoids increased significantly after processing. GC-IMS and GC-MS analysis revealed that the contents of aldehydes and ketones were significantly increased, while esters and partial alcohols decreased after processing into jujube leaf tea. The main flavor substances shifted from eugenol in fresh jujube leaves to (E)-2-hexenal in jujube leaf tea. The integrated approach demonstrated that amino acids and lipids were closely linked to the formation of volatile metabolites during processing.

Another study on Gastrodia elata processing [29] used LC-MS and GC-IMS to evaluate the impact of different processing methods on quality. The analysis identified 62 intrinsic components, predominantly amino acids, with 20 classified as differential compounds, while 95 volatile components (primarily alcohols, aldehydes, and esters) were detected, with 31 being differential VOCs. The combination of analytical techniques with multidimensional bionic technology (E-nose, E-tongue) and chemometric models provided a comprehensive quality assessment framework.

Food Safety and Contaminant Screening

IMS technologies have gained importance in food safety applications, particularly for the detection of contaminants and adulterants in complex food matrices. The hyperspectral separation capability of IMS enables better detection of target compounds amidst chemical noise, improving sensitivity and selectivity [25] [18]. LC-IMS-MS methods have been developed for various food toxicants, including pesticides, veterinary drugs, mycotoxins, and environmental contaminants. The additional CCS dimension provides an extra identification point that increases confidence in compound annotation, particularly for non-targeted screening approaches [30].

The creation of dedicated spectral libraries that include CCS values, such as the WFSR Food Safety Mass Spectral Library [30], represents a significant advancement in food safety analysis. This manually curated open-access library contains 1001 food toxicants and 6993 spectra across multiple collision energies, providing a valuable resource for compound identification. The inclusion of CCS values in such libraries enhances identification confidence and facilitates the development of targeted screening methods for multiple contaminants in a single analysis.

Ion mobility spectrometry provides a valuable additional separation dimension that significantly enhances the analytical capabilities of both GC- and LC-based methods for food compound analysis. The experimental data and comparative assessment presented in this guide demonstrate that GC-IMS and LC-MS offer complementary rather than competing capabilities, with each technique excelling in specific application domains.

GC-IMS provides distinct advantages for volatile compound analysis with its minimal sample preparation requirements, rapid analysis times, and potential for portability. The technique has proven highly effective for geographical origin verification, process monitoring, and flavor profiling applications. Meanwhile, LC-MS remains the gold standard for comprehensive non-volatile compound analysis, offering superior identification power through exact mass measurement and fragmentation patterns. The integration of IMS into LC-MS workflows further enhances performance by providing additional separation of isobaric and isomeric compounds, increasing peak capacity, and supplying CCS values as additional molecular descriptors for identification confidence.

The selection between these techniques should be guided by the specific analytical requirements, including the target compound classes, required sensitivity and specificity, sample throughput needs, and available resources. For comprehensive food characterization, the combined application of both techniques provides the most complete picture of food composition, encompassing both volatile and non-volatile compounds. As IMS technology continues to evolve with improvements in resolution, sensitivity, and database availability, its integration into routine food analysis workflows is expected to expand, further strengthening analytical capabilities in food authentication, quality control, and safety assessment.

Practical Workflows and Food Analysis Applications

The accurate analysis of non-volatile compounds in food matrices presents significant challenges for researchers and analytical scientists. Complex biological samples contain numerous interfering substances that can compromise detection sensitivity and analytical accuracy. Effective sample preparation is therefore a critical prerequisite for reliable results in food safety, quality control, and regulatory compliance. This guide objectively compares three prominent sample preparation strategies—QuEChERS, Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME), and Derivatization—within the specific context of methodological selection for gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) versus liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) platforms. Each technique offers distinct mechanisms of action, with varying compatibility for different analyte classes, matrix types, and analytical instrumentation. The following sections provide detailed performance comparisons, experimental protocols, and practical guidance to inform method selection for non-volatile food compound analysis, supported by quantitative experimental data from recent scientific studies.

Technical Comparison of Sample Preparation Methods

The selection of an appropriate sample preparation strategy depends on multiple factors, including target analyte characteristics, sample matrix composition, and the chosen analytical instrumentation. The following comparison examines the fundamental principles, strengths, and limitations of QuEChERS, SPME, and Derivatization techniques to provide a foundation for informed methodological selection.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Sample Preparation Techniques

| Characteristic | QuEChERS | SPME | Derivatization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Liquid-liquid extraction & dispersive SPE | Partitioning between sample & coated fiber | Chemical modification of analytes |

| Primary Use | Multi-residue pesticide extraction | Extraction & concentration of volatiles | Improving volatility/detectability |

| Sample Throughput | High | Medium | Low to Medium |

| Solvent Consumption | Moderate | Solvent-free | Variable |

| Automation Potential | Moderate | High | Moderate |

QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) was originally developed for multi-residue pesticide analysis in high-water-content matrices but has since been successfully adapted to a wide range of sample types, including low-moisture and high-fat commodities [31] [32]. The method involves simultaneous extraction and partitioning using acetonitrile and salt solutions, followed by a cleanup step using dispersive solid-phase extraction (d-SPE) to remove various matrix interferences. Its flexibility allows researchers to modify parameters such as solvent composition, salt buffers, and d-SPE sorbents to optimize performance for specific sample matrices [32].

SPME is a non-exhaustive extraction technique that integrates sampling, extraction, and concentration into a single step. Analytes partition from the sample matrix to a coated fiber, which is then transferred to the analytical instrument for desorption and analysis [33]. Recent advancements have introduced alternative geometries, including thin-film SPME (TF-SPME), which provides a larger surface area for extraction, significantly enhancing sensitivity for a wider range of analytes, particularly polar compounds [33]. The technique is especially valuable for extracting volatile and semi-volatile compounds, with the extraction mode (direct immersion or headspace) selectable based on analyte properties.

Derivatization involves chemically modifying target analytes to alter their physical and chemical properties, making them more amenable to chromatographic analysis. This process is particularly crucial for GC-based analysis of non-volatile compounds, such as fatty acids and biogenic amines, which lack sufficient volatility or thermal stability [34] [35]. Derivatization can significantly enhance detection sensitivity by introducing functional groups with superior spectroscopic or mass spectrometric properties. The selection of an appropriate derivatizing agent is critical, as it directly impacts reaction efficiency, derivative stability, and overall analytical performance [35].

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Independent studies have systematically evaluated the performance characteristics of these sample preparation methods across different food matrices and analyte classes. The following quantitative data provides objective comparison metrics to guide method selection.

Recovery and Efficiency Metrics

Recovery rates represent one of the most critical parameters for evaluating extraction efficiency. A comprehensive study comparing QuEChERS to traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) for pesticide analysis in spinach, rice, and mandarins demonstrated the clear superiority of the QuEChERS approach, with average recoveries of 101.3–105.8% compared to 62.6–85.5% for LLE [31]. Furthermore, the QuEChERS method exhibited more consistent performance across different matrices, with over 95% of pesticide components falling within the acceptable 70–120% recovery range.

Table 2: Comparative Performance Data for Sample Preparation Methods

| Method | Analytes | Matrix | Recovery Range | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS (AOAC) | 40 Pesticides | Celery, Spinach | 85-115% | Higher response for most pesticides | [32] |

| QuEChERS (EN) | 40 Pesticides | Avocado, Orange | 80-110% | Effective for acidic compounds | [32] |

| TF-SPME (HLB) | 11 Odorants | Food & Beverages | Significantly higher than fiber SPME/SBSE | Superior for polar compounds | [33] |

| Derivatization (TMS-DM) | Fatty Acids | Bakery Products | 90-106% | Higher recovery for unsaturated FAs | [34] |

| Derivatization (Dansyl) | Biogenic Amines | Sausage & Cheese | Wide linear range, high sensitivity | Excellent derivative stability | [35] |

Similar advantages were observed for QuEChERS in the analysis of antibiotics in fish tissue and fish feed, where the original QuEChERS method employing Enhanced Matrix Removal (EMR)-lipid sorbent achieved superior recoveries (70–110% in fish tissue, 69–119% in feed) for most analytes compared to the AOAC 2007.01 method using Z-Sep+ [36]. The method also demonstrated lower uncertainties (<18.4%) and met validation criteria for precision (<19.7%) and linearity (R² > 0.9899) [36].

For SPME techniques, a comparative study evaluating different formats revealed that the novel TF-SPME devices with hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) particles consistently outperformed both traditional SPME fibers and stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) across all 11 food odorants tested [33]. This performance advantage was particularly pronounced for polar compounds such as acetic acid, butanoic acid, and 2,3-butanedione, with TF-SPME being the only method capable of detecting methional in the standard mixture [33].

In derivatization applications, method selection significantly impacts accuracy and precision. For fatty acid analysis in bakery products, the base-catalyzed (trimethylsilyl)diazomethane (TMS-DM) method demonstrated higher recovery values with less variation (90–106%) compared to the traditional KOCH₃/HCl method (84–112%) [34]. Similarly, for biogenic amine analysis in sausage and cheese, dansyl chloride derivatization provided superior derivative stability, sensitivity, and accuracy compared to benzoyl chloride, 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chloride, and dabsyl chloride approaches [35].

Matrix Effects and Cleanup Efficiency

Matrix effects represent a significant challenge in food analysis, particularly when employing mass spectrometric detection. Both QuEChERS and LLE methods demonstrate a tendency for ion suppression across various matrices, necessitating the use of matrix-matched calibration for accurate quantification [31]. The effectiveness of the cleanup step in QuEChERS protocols varies considerably based on the selected d-SPE sorbents. For high-water, low-lipid matrices like celery, a simple combination of magnesium sulfate and primary secondary amine (PSA) sorbent often suffices. In contrast, high-fat matrices like avocado require additional sorbents such as C18 for effective lipid removal [32].

The evolution of SPME sorbent chemistries has progressively improved matrix tolerance. Traditional polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) coatings exhibit strong affinity for non-polar compounds but limited efficiency for polar analytes. The introduction of HLB particles in TF-SPME devices has significantly enhanced the extraction capability for a wide polarity range without requiring derivatization or salting-out strategies [33]. This advancement is particularly valuable for complex food matrices containing diverse analyte classes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

QuEChERS Method for Multi-Residue Analysis

The standard QuEChERS procedure comprises two main stages: extraction and cleanup. The following protocol is adapted from the EN 15662 method, suitable for a wide range of pesticide residues in various food matrices [32].

Sample Preparation: Homogenize a representative sample. For high-water-content matrices (e.g., fruits, vegetables), use 10–15 g of sample. For low-moisture samples (e.g., grains, spices), reduce sample mass to 5 g and add 10 mL of water to ensure proper partitioning [32].

Extraction: Place the prepared sample in a 50-mL centrifuge tube. Add 10 mL of acetonitrile (1% acetic acid for acidic compounds) and shake vigorously for 1 minute. Add extraction salts (4 g MgSO₄, 1 g NaCl, 1 g sodium citrate, 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate sesquihydrate for EN method) and shake immediately and vigorously for another minute to prevent salt clumping. Centrifuge at >3000 RCF for 5 minutes.

Cleanup: Transfer 1 mL of the supernatant (acetonitrile layer) to a d-SPE tube containing 150 mg MgSO₄, 25 mg PSA, and 25 mg C18 (adjust sorbent proportions based on matrix interference). Shake for 30 seconds and centrifuge at >3000 RCF for 5 minutes. Filter the supernatant through a 0.2-μm syringe filter prior to LC-MS analysis [32].

Method Selection: The choice between unbuffered, AOAC (pH ~4.75), and EN (pH 5.0–5.5) salt formulations should be based on target analyte stability. AOAC salts generally provide higher responses for most pesticides in commodities like celery, spinach, and avocado [32].

Thin-Film SPME for Odorant Analysis