LADME Framework for Bioactive Food Compounds: From Bioaccessibility to Bioefficacy in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the LADME (Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination) framework as it applies to bioactive food compounds.

LADME Framework for Bioactive Food Compounds: From Bioaccessibility to Bioefficacy in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the LADME (Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination) framework as it applies to bioactive food compounds. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles governing the bioavailability of dietary bioactives, examines advanced methodological approaches for its assessment, and discusses strategies to overcome key bioavailability challenges. The content further validates these concepts through an analysis of food-drug interactions and a comparative evaluation with pharmaceutical pharmacokinetics, synthesizing critical insights for enhancing the efficacy and application of bioactive compounds in functional foods and therapeutic contexts.

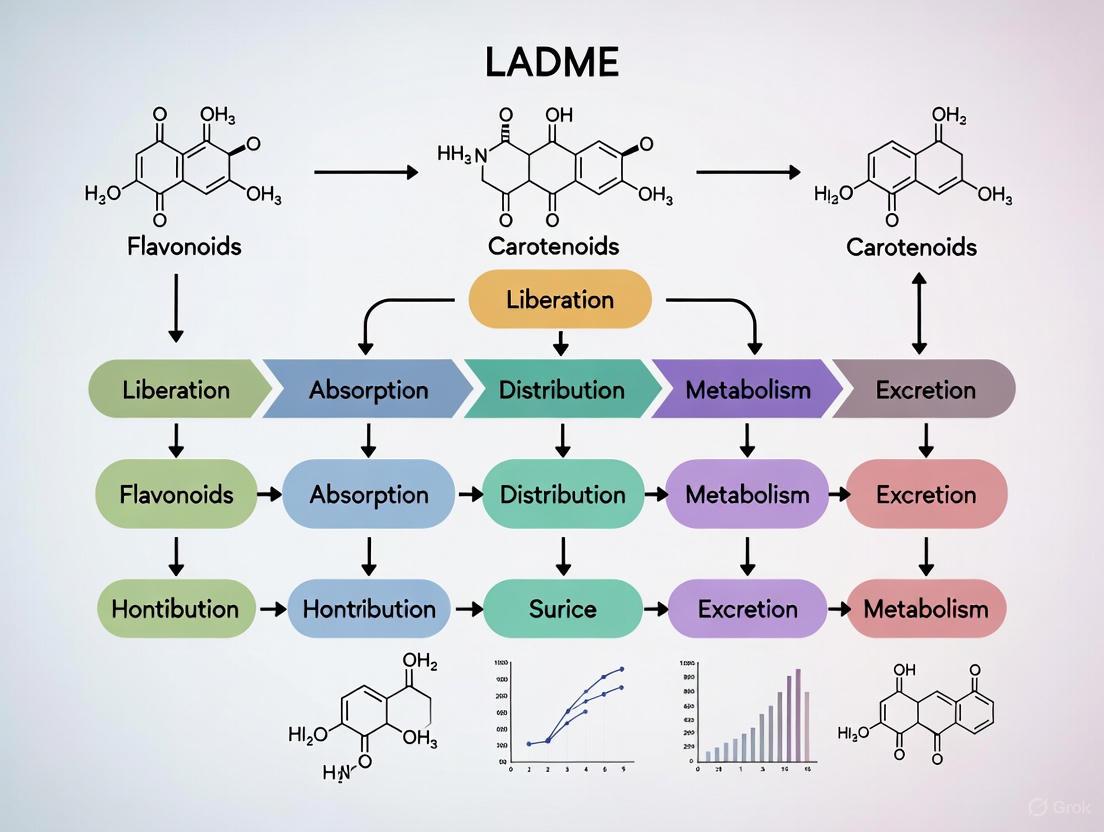

Deconstructing LADME: The Fundamental Journey of Bioactive Compounds from Plate to Target

The LADME framework is a fundamental pharmacokinetic model that describes the fate of bioactive compounds within an organism. This framework systematically outlines the processes of Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination, providing a comprehensive understanding of the bioavailability and efficacy of dietary bioactives. Within nutritional sciences and functional food research, applying the LADME framework is crucial for quantifying intake recommendations and linking specific bioactive compounds to health benefits [1]. This whitepaper details the core principles, experimental methodologies, and research tools essential for investigating the LADME phases of bioactive food compounds, with a focus on enabling evidence-based formulation of functional foods.

Bioactive food compounds, such as polyphenols, carotenoids, and omega-3 fatty acids, provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gut-modulating effects [2]. However, their therapeutic potential is not solely determined by their presence in food; it is fundamentally governed by their pharmacokinetic profile within the human body. The LADME framework offers a structured approach to investigate this lifecycle.

The framework's relevance is underscored by ongoing efforts to develop a formal structure for establishing recommended intakes of bioactive dietary substances. This process requires characterizing the bioactive, quantifying its amounts in food sources, evaluating safety, and establishing a causal relationship between intake and health markers through systematic evidence reviews [1]. The LADME framework provides the mechanistic backbone for this efficacy evaluation, bridging the gap between food consumption and physiological outcome.

Core Phases of the LADME Framework

Liberation

Liberation refers to the release of the bioactive compound from its food matrix. This is the initial and critical step for orally consumed substances, as it directly influences the amount available for subsequent absorption.

- Gastric and Intestinal Processes: In the digestive tract, liberation involves mechanical breakdown (chewing, peristalsis) and chemical hydrolysis by gastric acid and digestive enzymes. The efficiency of these processes is highly dependent on the food matrix. For instance, the liberation of carotenoids from raw vegetables is less efficient than from processed or cooked ones.

- Experimental Focus: Research in this phase often centers on developing innovative food processing techniques and delivery systems to enhance the stability and release of sensitive bioactives. Nanoencapsulation has emerged as a prominent strategy to protect compounds like polyphenols from degradation in the stomach and target their release to the intestine [2].

Absorption

Absorption encompasses the passage of the liberated bioactive compound through the intestinal mucosa into the systemic circulation or lymphatic system.

- Pathways and Mechanisms: Absorption can occur via passive diffusion (for lipophilic compounds), active transport (requiring carrier proteins), or paracellular transport (between cells). The chemical nature of the compound—its size, polarity, and solubility—dictates the primary mechanism.

- Key Site and Challenges: The small intestine is the primary site for absorption due to its large surface area. A major challenge for many bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenols, is their inherently low bioavailability, which is often a consequence of poor aqueous solubility or instability in the intestinal environment [2].

- Research Objectives: A primary goal in functional food science is to improve the bioavailability of these compounds. This is actively pursued through formulation strategies such as emulsion-based systems, liposomes, and the aforementioned nanoencapsulation, all designed to enhance solubility and protect the compound during transit.

Distribution

Distribution describes the reversible transfer of a bioactive compound from the systemic circulation to various tissues and organs throughout the body.

- Influencing Factors: The extent of distribution is determined by the compound's affinity for specific tissues, its ability to cross biological barriers (e.g., the blood-brain barrier), and its binding to plasma proteins. Lipophilic compounds, such as carotenoids and omega-3 fatty acids, often distribute into adipose tissue or are targeted to organs like the eyes and brain.

- Health Outcome Link: The distribution pattern is critical for understanding a compound's mechanism of action. For example, the efficacy of lutein in supporting eye health is directly linked to its distribution and accumulation in the macula [2].

Metabolism

Metabolism involves the enzymatic modification of the absorbed bioactive compound, primarily aiming to make it more water-soluble for excretion. These reactions are typically categorized as Phase I (functionalization, e.g., oxidation, hydrolysis) and Phase II (conjugation, e.g., glucuronidation, sulfation).

- Primary Site and Consequences: The liver is the major organ for metabolism, though the gut wall and microbiome also contribute significantly. Metabolism can lead to deactivation of the bioactive, but in some cases, it can produce active metabolites that contribute to or are responsible for the observed health effects.

- Inter-individual Variability: Metabolic rates can vary widely among individuals due to genetic polymorphisms, age, sex, and gut microbiota composition, leading to significant differences in individual responses to the same dose of a bioactive.

Elimination

Elimination is the final process by which the bioactive compound and its metabolites are removed from the body.

- Primary Routes: The main routes of elimination are via urine (for water-soluble metabolites) and feces (for unabsorbed compounds or those excreted in bile). Minor routes include exhalation, sweat, and breast milk.

- Pharmacokinetic Parameter: The elimination half-life of a compound determines the duration of its presence and action in the body, which directly informs the frequency of intake required to maintain a desired physiological effect.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential flow and key interactions within the LADME framework for a bioactive compound.

Quantitative Profiling of Key Bioactive Compounds

The pharmacokinetic behavior of a bioactive compound is intrinsically linked to its chemical structure and properties. The following table summarizes the LADME-relevant characteristics and established health benefits of major bioactive compound classes.

Table 1: LADME and Health Benefit Profile of Key Bioactive Compounds

| Bioactive Compound & Examples | Key Food Sources | Typical Daily Intake (mg/day) | Key LADME Considerations | Primary Documented Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids (Quercetin, Catechins) | Berries, apples, onions, green tea, cocoa, citrus fruits [2] | 300 - 600 [2] | Low oral bioavailability; extensive Phase II metabolism (glucuronidation) in gut/liver; influenced by gut microbiota. | Cardiovascular protection, anti-inflammatory effects, antioxidant properties [2]. |

| Phenolic Acids (Caffeic acid, Ferulic acid) | Coffee, whole grains, berries, spices, olive oil [2] | 200 - 500 [2] | Often esterified in food matrix; requires liberation by gut enzymes; rapid absorption and elimination. | Neuroprotection, antioxidant activity, reduced inflammation [2]. |

| Carotenoids (Beta-carotene, Lutein) | Carrots, sweet potatoes, spinach, mangoes, kale [2] | Beta-carotene: 2-7 [2] Lutein: 1-3 mg [2] | Lipophilic; requires dietary fat for liberation/absorption; distributed to fatty tissues and retina; can be cleaved to Vitamin A. | Supports immune function, enhances vision (lutein protects vs. AMD) [2]. |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA, DHA) | Fatty fish, algae oils, fortified foods | 800 - 1200 (for cardiovascular benefit) [2] | Absorbed via lymphatic system; distributed and incorporated into cell membranes; beta-oxidation for energy. | Significantly reduces risk of major cardiovascular events [2]. |

| Stilbenes (Resveratrol) | Red wine, grapes, peanuts, blueberries [2] | ~1 [2] | Very low bioavailability due to rapid and extensive metabolism; high inter-individual variability. | Anti-aging effects, cardiovascular protection, anticancer properties [2]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols for LADME Profiling

In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Model

This protocol simulates human digestion to study the Liberation and stability of a bioactive from its food matrix.

- Oral Phase: Incubate the food sample with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) containing amylase at pH 7 for 2-5 minutes.

- Gastric Phase: Adjust the mixture to pH 3.0 with HCl, add simulated gastric fluid (SGF) containing pepsin, and incubate with constant agitation for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Intestinal Phase: Adjust the gastric chyme to pH 7.0 with NaOH, add simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) containing pancreatin and bile salts. Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the final digest to separate the aqueous fraction (containing liberated bioactives) from the solid residue. The bioaccessible fraction in the aqueous phase can be quantified using techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

Caco-2 Cell Transwell Model for Absorption

This is a standard in vitro model for predicting intestinal Absorption.

- Cell Culture: Grow and differentiate human colon adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cells on permeable filters in transwell plates for 21-28 days until they form a polarized monolayer with tight junctions.

- Dosing and Sampling: Add the bioactive compound (e.g., from the bioaccessible fraction of the digestion model) to the apical compartment (simulating intestinal lumen). Collect samples from the basolateral compartment at regular intervals over 2-4 hours.

- Integrity Monitoring: Monitor the integrity of the cell monolayer throughout the experiment by measuring the Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) or the permeability of a non-absorbable marker like Lucifer Yellow.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the Apparent Permeability (Papp) coefficient using the amount of compound transported to the basolateral side. A high Papp value indicates high absorption potential.

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study Design

In vivo studies in animal models or humans are required for a holistic view of Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination.

- Dosing and Sampling: Administer a precise dose of the bioactive compound orally to the subject. Collect serial blood samples at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours) via an indwelling catheter. Urine and feces are also collected over 24-48 hours.

- Sample Analysis: Quantify the concentration of the parent compound and its major metabolites in plasma, urine, and feces using a validated bioanalytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

- Data Analysis: Use non-compartmental analysis (NCA) to calculate key pharmacokinetic parameters:

- C~max~: Maximum observed plasma concentration.

- T~max~: Time to reach C~max~.

- AUC~0-t~: Area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to the last measurable time point, representing total systemic exposure.

- t~1/2~: Elimination half-life.

- CL/F: Apparent clearance.

- V~d~/F: Apparent volume of distribution.

The workflow for these core experiments is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for LADME Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in LADME Studies |

|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids (Salivary, Gastric, Intestinal) | To replicate the chemical environment (pH, enzymes, ions) of the human GI tract for in vitro digestion studies (Liberation). |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A well-established human cell model that, upon differentiation, mimics the intestinal epithelium. Used to study permeability and transport mechanisms (Absorption). |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | The gold-standard analytical technique for the sensitive and specific quantification of bioactive compounds and their metabolites in complex biological matrices like plasma, urine, and tissue homogenates (All LADME phases). |

| Specific Metabolic Enzyme Kits (e.g., CYP450 isoforms, UGTs) | Recombinant enzymes or microsomal preparations used to identify the specific enzymes involved in the biotransformation of a bioactive compound and to characterize metabolites (Metabolism). |

| Validated Animal Models (e.g., rat, mouse, pig) | Used for in vivo pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution studies, providing a whole-body system to investigate the integrated LADME process. |

The LADME framework provides an indispensable, systematic approach for advancing the science of bioactive food compounds. By dissecting the journey of a compound from ingestion to elimination, researchers can move beyond simply identifying beneficial substances to understanding and optimizing their in vivo efficacy. The application of robust experimental protocols—from in vitro models to human clinical trials—is critical for generating the high-quality, quantitative evidence required to develop intake recommendations [1]. As the field progresses, overcoming challenges related to the low bioavailability of many bioactives through innovative delivery systems [2] will be paramount. Ultimately, a deep understanding of the LADME framework empowers researchers, nutrition scientists, and product developers to create evidence-based functional foods that reliably deliver on their promise of enhanced health and well-being.

For researchers and scientists developing nutraceuticals and functional foods, the journey of a bioactive compound from ingestion to its target site of action is a complex cascade of physiological processes. While the health benefits of compounds like polyphenols, carotenoids, and bioactive peptides are widely recognized, their efficacy is ultimately governed by their fate within the human body. It is a critical misconception to equate the concentration of a compound in a food source with its physiological impact. Bioaccessibility and bioavailability are the sequential, interdependent parameters that determine the functional efficacy of nutraceuticals, and understanding their distinction is fundamental for rational product development [3] [4].

This distinction becomes particularly significant when framed within the LADME framework—Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination—which provides a comprehensive model for tracking bioactive compounds [4] [5]. Within this framework, bioaccessibility primarily concerns the initial Liberation step, making compounds accessible for absorption, while bioavailability encompasses the entire LADME sequence. The scientific and commercial challenge is substantial; many bioactive phytochemicals exhibit absorption rates as low as 0.3% to 43%, leading to minimal systemic circulation and limited therapeutic potential [4]. This whitepaper delineates the critical distinctions between bioaccessibility and bioavailability, examines the factors influencing each, and outlines advanced assessment methodologies and strategies for their enhancement, providing a technical guide for research and development professionals.

Defining the Critical Concepts within the LADME Framework

Conceptual Clarification and the LADME Sequence

In nutraceutical science, precise terminology is crucial for accurate communication and research design. The following concepts form the foundation of efficacy assessment:

Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a compound that is released from its food matrix and becomes solubilized in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby becoming available for potential intestinal absorption [3] [4]. It encompasses the processes of digestion and release, culminating in the compound's presence in the gut lumen as a solubilized entity. For lipophilic compounds like carotenoids, this often involves incorporation into mixed micelles alongside bile salts, cholesterol, and fatty acids [6]. In essence, bioaccessibility answers the question: "Is the compound free and ready for uptake?"

Bioavailability is a broader and more complex parameter. It is defined as the proportion of an ingested compound that reaches the systemic circulation and is thereby delivered to the site of physiological action [3] [7]. It integrates the entire LADME sequence: Liberation from the food matrix (bioaccessibility), Absorption through the intestinal epithelium, Distribution to various tissues and organs via circulation, Metabolism (which can occur in the gut lumen, intestinal cells, or the liver), and finally, Elimination from the body [4]. From a nutritional perspective, bioavailability indicates the fraction of a nutrient that is stored or utilized in physiological functions [7].

Bioactivity represents the ultimate endpoint: the measurable, beneficial physiological effect exerted by the bioactive compound or its metabolites after interacting with molecular targets in the body [3]. A compound may be highly bioavailable yet lack significant bioactivity if it does not effectively interact with its intended target.

Table 1: Core Concepts in Nutraceutical Efficacy

| Term | Definition | Key Processes Included | Position in LADME |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaccessibility | Fraction released from food matrix and solubilized in the gut [3] [4] | Digestion, enzymatic degradation, solubilization | Primarily Liberation |

| Bioavailability | Fraction that reaches systemic circulation and is available for tissue distribution/action [3] [7] | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination | Entire LADME sequence |

| Bioactivity | The physiological effect exerted after interaction with target biomolecules [3] | Receptor binding, signaling pathway modulation, gene expression | Post-LADME, at target tissue |

The relationship between these concepts is sequential and hierarchical, as visualized below. A compound must first be bioaccessible to be bioavailable, and must be bioavailable to exert bioactivity.

Factors Influencing Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

The journey of a bioactive compound is fraught with obstacles. Understanding these factors is key to predicting efficacy and designing effective nutraceuticals.

Key Determinants of Bioaccessibility

- Food Matrix Effect: The physical entrapment of bioactive compounds within plant and food structures (e.g., cell walls, protein complexes) is a primary barrier. For instance, ferulic acid in whole grain wheat exhibits bioavailability below 1% due to its strong binding to polysaccharides; this can be improved through fermentation, which breaks ester links and liberates the compound [4].

- Composition of the Meal: The presence of other macronutrients significantly impacts bioaccessibility. Dietary fats are crucial for the micellarization and subsequent bioaccessibility of lipophilic compounds like carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins. Studies show that consuming salad with full-fat or reduced-fat dressing significantly improves carotenoid absorption compared to fat-free dressing [4].

- Processing and Preparation Methods: Thermal and non-thermal processing can disrupt the food matrix, enhancing release. Cooking, fermentation, and emerging technologies like high-pressure processing and cold atmospheric plasma can break down cell walls and inhibit degrading enzymes, thereby increasing the bioaccessible fraction [8].

- Chemical Structure and Molecular Linkage: The specific form of a compound (e.g., glycosylated vs. aglycone polyphenols, esterified vs. free carotenoids) determines its susceptibility to digestive enzymes and its solubility in the gastrointestinal fluids [6].

Key Determinants of Bioavailability

- Absorption and Transport Mechanisms: Bioavailability is governed by the compound's ability to cross the intestinal epithelium. Hydrophilic compounds often require specific transporters, while lipophilic compounds rely on passive diffusion or micelle-assisted uptake. Low permeability is a common cause of low bioavailability [3] [4].

- Host Metabolism and Gut Microbiota: Extensive pre-systemic metabolism, either by host enzymes in the gut and liver or by the colonic microbiota, can rapidly transform and inactivate many bioactive compounds. Conversely, some compounds like certain polyphenols are activated by microbial metabolism, producing metabolites with enhanced bioactivity [4].

- Inter-Individual Variability: Genetic polymorphisms affecting digestive enzyme activity, transporter expression, and metabolic pathways can lead to significant variability in bioavailability between individuals [4] [6]. This is often summarized by the SLAMENGHI mnemonic, encompassing Species of carotenoid, Linkage, Amount, Matrix, Effectors, Nutrient status, Genetic, Host-related factors, and Interactions [6].

- Effector Nutrients: Co-consumed nutrients can act as antagonists or synergists. For example, calcium can inhibit iron absorption, while vitamin C can enhance it [4].

Assessment Methodologies: From In Vitro Simulations to Clinical Gold Standards

Accurately assessing bioaccessibility and bioavailability requires a multi-faceted approach, ranging from controlled in vitro simulations to complex in vivo studies.

In Vitro Digestion Models

In vitro models simulate human physiological conditions to predict the bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds, offering ethical, economical, and high-throughput alternatives to in vivo studies [9] [10]. These models typically follow a sequential simulation of the gastrointestinal tract.

Table 2: In Vitro Models for Assessing Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

| Method | Endpoint Measured | Principle & Workflow | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Digestion | Bioaccessibility | Two- or three-step digestion (oral, gastric, intestinal) with fixed enzyme concentrations and pH [9] [3]. | Advantages: Simple, inexpensive, high-throughput [10].Limitations: Oversimplifies dynamic physiology. |

| Dynamic Models (TIM) | Bioaccessibility | Computer-controlled system simulating stomach to ileum with real-time pH adjustment, peristalsis, and metabolite removal [10]. | Advantages: More physiologically relevant, allows sampling at different gut sections [10].Limitations: Expensive, complex operation [10]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Model | Bioavailability (Absorption) | Human intestinal cell line grown on Transwell inserts. Measures compound uptake and transport from apical to basolateral side [9] [10]. | Advantages: Studies absorption mechanisms and transporter effects [10].Limitations: Requires cell culture expertise; does not fully capture mucus/microbiome layer [10]. |

| Dialyzability/Solubility | Bioaccessibility | After digestion, the soluble fraction is separated by centrifugation or dialysis through a membrane of specific molecular weight cut-off [10]. | Advantages: Simple, inexpensive estimate of soluble, absorbable fraction [10].Limitations: Cannot predict uptake kinetics or transporter effects [10]. |

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a coupled in vitro digestion - Caco-2 absorption assay, a common protocol for predicting bioavailability.

The Gold Standard: In Vivo Assessment

Despite the utility of in vitro models, human studies are considered the "gold standard" for determining true bioavailability [9]. This involves pharmacokinetic studies that measure the concentration of the bioactive compound and its metabolites in blood plasma or serum over time after consumption. The resulting concentration-time curve allows for the calculation of key parameters such as the area under the curve (AUC), peak concentration (C~max~), and time to peak concentration (T~max~) [4]. In vivo studies are indispensable for validating in vitro models and understanding the complete LADME profile, including tissue distribution and the biological activity of metabolites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful assessment of bioaccessibility and bioavailability relies on a suite of specialized reagents, cell models, and analytical equipment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Digestive Enzymes | Pepsin (porcine), Pancreatin (porcine), Bile salts (porcine or bovine) | Simulate the enzymatic hydrolysis and emulsification of nutrients in the stomach (pepsin) and small intestine (pancreatin, bile) [10]. |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2 cell line (HTB-37), Transwell inserts, Cell culture media | Model the human intestinal epithelium for absorption and transport studies. Transwell inserts create apical and basolateral compartments to mimic the gut lumen and blood side [10]. |

| Analytical Standards | Pure reference compounds (e.g., Quercetin, β-carotene, Curcumin), Isotope-labeled internal standards | Essential for identification and accurate quantification of bioactive compounds and their metabolites in complex digests or biological fluids using HPLC or MS [3] [8]. |

| Advanced Gut Models | TIM system (TNO), Mucolytic agents, Donor fecal matter | Sophisticated systems that dynamically simulate GI physiology (TIM). Fecal matter is used to simulate colonic fermentation in models of the large intestine [10]. |

Advanced Strategies for Enhancing Delivery and Efficacy

Overcoming the inherent limitations of poor solubility and stability is a primary focus of nutraceutical R&D. Nanotechnology offers some of the most promising strategies.

- Nanoemulsions: These are oil-in-water or water-in-oil colloidal dispersions with droplet sizes typically below 250 nm. They are highly effective at encapsulating lipophilic bioactives (e.g., carotenoids, curcumin), enhancing their water dispersibility, protecting them from degradation, and promoting rapid absorption in the GI tract due to their high surface area [6] [5].

- Polymeric Nanoparticles and Micelles: Systems like polymeric micelles self-assemble from amphiphilic block copolymers, creating a hydrophobic core for drug encapsulation and a hydrophilic shell (often PEG) that provides steric protection and prolongs circulation. These systems can be engineered for stimulus-sensitive release (e.g., pH- or thermo-responsive) for targeted delivery [11].

- Electrospun Nanofibers: This technique uses electrical force to create ultrafine fibers from polymer solutions. These fibers offer a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and can provide high encapsulation efficiency and sustained or controlled release of bioactives, making them suitable for solid-state functional foods or edible coatings [5].

- Encapsulation in Acid-Resistant Capsules: Formulating nutraceuticals into capsules designed to withstand the stomach's acidic environment and release their payload in the intestine can significantly improve the recovery of sensitive compounds like polyphenols, as demonstrated with tea extracts and fennel waste capsules [3].

The critical distinction between bioaccessibility and bioavailability is non-negotiable for the scientifically-grounded development of efficacious nutraceuticals. Bioaccessibility—the liberation and solubilization of a compound—is the essential first gatekeeper. Bioavailability—the fraction that reaches systemic circulation—is the ultimate determinant of physiological potential, integrating the complex LADME pathway. While in vitro models provide invaluable, high-throughput tools for screening and formulation development, they must be applied with a clear understanding of their endpoints and limitations. The future of nutraceutical science lies in the continued refinement of these assessment methods, coupled with the intelligent application of advanced delivery systems like nanoemulsions and nanomicelles. By systematically addressing the barriers to bioaccessibility and bioavailability, researchers can truly bridge the gap between the promising bioactivity of compounds observed in vitro and their tangible health benefits in human consumers.

Physicochemical Factors Governing Bioactive Liberation from Food Matrices

The bioefficacy of bioactive food compounds is fundamentally governed by their journey through the body, conceptualized by the LADME framework: Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination [12] [13]. Liberation, the initial and critical step, refers to the release of bioactive compounds from the native food matrix into the gastrointestinal fluids, making them available for absorption [14]. This process of bioaccessibility is a prerequisite for bioavailability and subsequent health benefits [15]. The efficiency of liberation is not a matter of chance but is governed by a complex interplay of physicochemical factors related to the compound itself, the food matrix, and the conditions of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [14]. Understanding and manipulating these factors is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to design functional foods, nutraceuticals, and oral drugs with predictable and enhanced efficacy. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these governing factors, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to contemporary research.

Key Physicochemical Factors Affecting Bioactive Liberation

The liberation of bioactives is a complex process influenced by multiple interconnected factors. The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual framework and the key physicochemical factors involved.

Food Matrix Effects

The food matrix acts as a physical entrapment system for bioactive compounds, and its structural integrity and composition are primary determinants of liberation.

- Cell Wall Integrity: Plant-based bioactives are often encapsulated within cellular structures. The rigidity and composition of plant cell walls, primarily composed of polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, constitute the first physical barrier to liberation. Mechanical disruption or enzymatic digestion of these walls is often a prerequisite for compound release [14].

- Macronutrient Interactions: Bioactives can bind non-covalently or covalently with macronutrients. For instance, polyphenols can form complexes with proteins or dietary fiber, which can sequester the compound and reduce its bioaccessibility [14] [16]. The presence and type of dietary lipids are particularly crucial for lipophilic compounds (e.g., carotenoids, fat-soluble vitamins), as lipids can facilitate their solubilization into mixed micelles during digestion [12].

- Presence of Antinutrients: Some food matrices contain inherent compounds like tannins or phytates that can bind to bioactives or inhibit digestive enzymes, further impeding the liberation process [14].

Compound Solubility and Chemical Structure

The intrinsic physicochemical properties of the bioactive compound itself are equally critical.

- Hydrophilicity vs. Lipophilicity: The polarity of a compound dictates its solubility in the aqueous environment of the GIT. Hydrophilic compounds (e.g., vitamin C, many phenolic glycosides) may be more readily liberated into gastrointestinal fluids, while lipophilic compounds (e.g., carotenoids, curcumin) require the presence of lipids and bile salts for solubilization [12].

- Molecular Size and Conformation: Larger, polymeric compounds (e.g., polymeric procyanidins in apples) may be less readily liberated compared to their smaller, monomeric counterparts. The specific glycosylation pattern of flavonoids, for example, can significantly influence their release kinetics [17].

- Crystalline vs. Amorphous State: The physical form of a compound within the matrix can affect its dissolution rate. Amorphous forms generally exhibit higher solubility and faster liberation compared to crystalline structures [14].

Quantitative Impact of Processing and Matrix Composition

Processing techniques are deliberately employed to modify the food matrix and enhance the liberation of bioactives. The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of different factors on bioactive content and liberation, as evidenced by recent research.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Processing and Matrix on Bioactive Compounds

| Factor / Material | Key Finding | Quantitative Change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) on Raspberries | Optimal UAE with Deep Eutectic Solvents increased phenolic & anthocyanin recovery. | Optimal conditions: 60 min, 35 mL solvent, 30 mL added water. | [18] |

| Pome Fruit Leaves vs. Fruits | Leaves are richer sources of bioactive and nutritional compounds than fruits. | Leaves had 3-6x higher mineral content (Ca, Mg, Fe, K); Higher organic acids (11.5-41.5 g/100g dw vs 1.3-2.4 g/100g dw in fruits). | [17] |

| Conventional Extraction of Chlorella | Optimal solid-liquid extraction for pigments & phenolics. | Optimal conditions: 30°C, 24 h, 37 mLsolv/gbiom; Yield: 15.39% w/w; Total carotenoids: 9.92 mg/gextr. | [19] |

| Hazelnut Skin (Agro-waste) | Defatted skins are a significant source of polyphenols. | Total Phenolic Content: ~155 mg GAE/g dw; Antioxidant Capacity (FRAP): ~23 mM TE. | [16] |

Mechanical and Thermal Treatments

Traditional processing methods physically and chemically alter the matrix structure.

- Thermal Treatments: Cooking, blanching, and pasteurization can soften plant tissues, denature proteins, and gelatinize starch, thereby breaking down physical barriers and enhancing the liberation of bound compounds. However, excessive heat can also degrade thermolabile bioactives [14].

- Mechanical Processes: Grinding, milling, and homogenization reduce particle size, exponentially increasing the surface area exposed to digestive fluids and enzymes. This is a fundamental principle for improving liberation efficiency [14].

- Soaking, Germination, and Fermentation: These biological processes utilize water uptake, endogenous enzymes, or microbial activity to pre-digest the food matrix, breakdown antinutrients, and facilitate the release of bioactives [14].

Advanced and Green Extraction Technologies

Modern technologies offer more controlled and efficient means of enhancing liberation, both in food processing and in in vitro analysis.

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): UAE employs acoustic cavitation—the formation, growth, and implosive collapse of microbubbles in a liquid medium. This implosion generates localized extremes of temperature and pressure, along with high-shear microjets, which effectively disrupt cell walls and enhance mass transfer [18] [20]. The efficiency of UAE is governed by multiple parameters, including frequency, ultrasonic power, temperature, and solvent selection [20].

- Other Non-Conventional Techniques: Techniques like Microwave-Assisted Extraction (dielectric heating), Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (specific cell wall degradation), and the use of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES)—green, tunable solvents—are also being increasingly adopted to achieve higher yields and more sustainable extraction processes [18] [20].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Liberation (Bioaccessibility)

The gold standard for evaluating the liberation of bioactives under controlled conditions that simulate human digestion is the in vitro gastrointestinal model.

Standardized In Vitro Digestion Protocol

This protocol outlines a general procedure for simulating the gastrointestinal fate of a food material to determine bioaccessibility.

- Sample Preparation: The food sample is homogenized and often subjected to a simulated oral phase. This involves mixing with a simulated saliva fluid (containing electrolytes and α-amylase) for a short period (e.g., 2-5 minutes) at neutral pH to mimic mastication and the initiation of starch digestion [15].

- Gastric Phase Simulation: The oral bolus is mixed with a simulated gastric juice. This typically includes a solution of pepsin in a hydrochloric acid buffer to achieve a pH of 2.5-3.0. The incubation is carried out for 1-2 hours at 37°C with constant agitation to simulate stomach motility. This phase is critical for protein digestion and the liberation of compounds from protein-complexed matrices [15].

- Intestinal Phase Simulation: The gastric chyme is neutralized and mixed with simulated intestinal fluid. This fluid contains pancreatic enzymes (e.g., pancreatin, which includes proteases, amylase, and lipase) and a bile salts extract. The pH is adjusted to ~7.0, and the mixture is incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. This phase is essential for the digestion of lipids and starch, and the solubilization of lipophilic compounds into mixed micelles [15].

- Bioaccessibility Analysis: After intestinal digestion, the sample is centrifuged at high speed (e.g., 10,000 x g for 1-2 hours) to separate the aqueous phase (containing solubilized bioactives) from the solid residue (undigested matrix and unliberated compounds). The bioactive content in the aqueous phase is analyzed using appropriate techniques (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis spectrophotometry). Bioaccessibility (%) is calculated as:

(Amount of bioactive in aqueous phase / Total amount in original sample) × 100[15].

Optimization of Extraction for Analysis: A Case Study

To accurately quantify the total potential bioactive content of a food material—a prerequisite for bioaccessibility calculations—efficient extraction is key. The following workflow demonstrates how experimental design is applied to optimize this process.

As exemplified by the optimization of phenolic compound recovery from raspberries using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) with Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES), a systematic approach is paramount [18].

- Selection of Factors and Responses: Critical extraction parameters are identified (e.g., extraction time, solvent volume, water content in DES). The target response variables are defined (e.g., total phenolic content, anthocyanin yield) [18].

- Experimental Design (DOE): A statistical design, such as the Box-Behnken Design (BBD), is employed. This response surface methodology allows for the efficient exploration of the effect of multiple factors and their interactions on the responses with a reduced number of experimental runs [18] [20].

- Model Fitting and Analysis: The experimental data is used to fit a quadratic polynomial model. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is performed to assess the statistical significance of the model and its terms. The model is then visualized using 3D response surface plots to understand the relationships between factors and responses [18] [19].

- Optimization and Validation: The fitted model is used to numerically predict the combination of factor levels that will yield an optimal response. These predicted optimal conditions are then validated experimentally to confirm the model's accuracy [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Success in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents, solvents, and materials. The following table catalogues essential solutions for studying bioactive liberation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioactive Liberation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green, tunable solvents for efficient extraction of polyphenols, anthocyanins [18]. | Compositions like lactic acid/maltose; Adjustable polarity for specific compound classes. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Key components of in vitro digestion models to mimic human GI conditions [15]. | Include salivary α-amylase, gastric pepsin/HCl, intestinal pancreatin & bile salts. |

| Enzymes for Matrix Digestion | Breakdown of complex food matrices (cell walls, proteins, starch) to liberate bound compounds. | Cellulases, pectinases, proteases, amylases; Used in enzyme-assisted extraction. |

| Green Solvent Mixtures | Eco-friendly alternative to traditional organic solvents for extraction. | Ethanol/water mixtures (e.g., 90/10 v/v); Effective for pigments & phenolics [19]. |

| Analytical Standards | Identification and quantification of specific bioactive compounds in liberated fractions. | Pure reference compounds (e.g., amentoflavone, quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnoside) [21]. |

The liberation of bioactive compounds from food matrices is a critical and controllable first step in the LADME pathway that dictates ultimate bioefficacy. This process is predominantly governed by the physicochemical interplay between the structural properties of the food matrix, the chemical nature of the bioactive compound, and the dynamic conditions of the gastrointestinal environment. A deep understanding of these factors—from the role of cell walls and macromolecular interactions to the impact of solubility and particle size—empowers researchers to strategically enhance bioaccessibility. Leveraging both traditional and advanced processing technologies, alongside rigorous in vitro digestion models and statistically optimized analytical protocols, provides a powerful toolkit for this purpose. Mastering the phase of bioactive liberation is therefore foundational for advancing the fields of functional food development, nutraceutical science, and drug delivery, enabling the rational design of interventions with proven and enhanced health-promoting potential.

The journey of a bioactive compound from ingestion to systemic circulation is a complex process governed by its fundamental physicochemical properties, chief among them being hydrophilicity and lipophilicity. Within the broader context of the LADME phases (Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination) of bioactive food compounds, understanding these distinct absorption pathways is crucial for predicting bioefficacy [22]. The affinity of a molecule for aqueous versus lipid environments directly determines its mechanism of traversal across the predominantly lipophilic biological membranes of the gastrointestinal tract [23] [24]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical contrast of the absorption mechanisms for hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental frameworks and predictive models necessary for advanced nutrient and drug delivery system design.

Fundamental Physicochemical Properties

The absorption pathway of a compound is primarily dictated by its lipophilicity, a property that quantifies its affinity for lipids or fats versus water [23].

Defining Lipophilicity and Hydrophilicity

- Lipophilicity: This "fat-loving" property describes a compound's ability to dissolve in non-polar solvents like oils. It is crucial for pharmacology as it significantly influences a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [23] [24]. Lipophilic drugs can readily diffuse through lipid-rich biological membranes [24].

- Hydrophilicity: This "water-loving" property describes a compound's affinity for aqueous environments. Hydrophilic compounds are polar and dissolve readily in water but struggle to cross lipid membranes without specialized transport mechanisms [25].

Quantitative Measurement: Log P and Log D

The partition coefficient is the standard measure for lipophilicity.

- Log P: This is the logarithm of the ratio of a compound's concentration in an organic solvent (typically n-octanol) to its concentration in water at equilibrium. A high log P indicates high lipophilicity, while a low or negative value indicates hydrophilicity [23]. Log P describes the intrinsic lipophilicity of the un-ionized drug.

- Log D: This parameter accounts for the ionization of compounds at a specific pH (e.g., physiological pH of 7.4). It is the logarithm of the ratio of the sum of the concentrations of all forms of the compound (ionized + un-ionized) in octanol to the sum of the concentrations of all forms in water [26]. Log D provides a more accurate picture of lipophilicity under physiologically relevant conditions.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two classes of compounds.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Compounds

| Characteristic | Hydrophilic Compounds | Lipophilic Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nature | Polar compounds [25] | Non-polar compounds [25] |

| Solubility | High water solubility [24] | High solubility in lipids/oils [23] [24] |

| Primary Transport Mechanism | Facilitated transport (carriers, ion channels) [25] | Passive diffusion through lipid bilayers [25] [24] |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration | Significantly less susceptible [25] | Free diffusion across the barrier [25] |

| Typical Elimination Route | Kidneys [25] | Liver metabolism, bile duct excretion [25] |

Absorption Pathways and the LADME Framework

The LADME framework outlines the journey of a xenobiotic: Liberation from its matrix, Absorption into systemic circulation, Distribution to tissues, Metabolism (biotransformation), and Elimination from the body [22] [27]. The absorption phase is where the divergence between hydrophilic and lipophilic pathways is most pronounced.

Pathway for Lipophilic Compounds

Lipophilic compounds are predominantly absorbed via passive transcellular diffusion due to their ability to dissolve in and traverse the lipid bilayer of cell membranes [24]. Once absorbed, their high log P (typically >5) directs them toward a specific systemic route that bypasses initial liver metabolism.

Diagram 1: Lipophilic Compound Absorption Pathway

Pathway for Hydrophilic Compounds

Hydrophilic compounds, being polar, cannot easily diffuse through the lipophilic core of the cell membrane. Their absorption is limited and occurs via alternative mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Hydrophilic Compound Absorption Pathway

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Investigation

Determining Lipophilicity: Log P/D Measurement

Objective: To quantitatively determine the lipophilicity of a compound using the shake-flask method [24] [26].

Table 2: Reagents for Log P/D Measurement

| Research Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol | Simulates the lipophilic environment of biological membranes [24] [26]. |

| Aqueous Buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4) | Simulates the aqueous physiological environment (e.g., plasma, cytosol) [26]. |

| Compound of Interest | The drug or bioactive molecule whose lipophilicity is being characterized. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer / HPLC | Analytical instruments used to accurately quantify the concentration of the compound in each phase after partitioning [26]. |

Methodology:

- Pre-Saturation: Pre-saturate n-octanol and the aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) with each other by mixing them overnight to ensure volume stability.

- Partitioning: Add a known quantity of the test compound to a mixture of pre-saturated octanol and buffer in a vial or tube. The typical volume ratio is 1:1.

- Equilibration: Shake the mixture vigorously for a set period (e.g., 1 hour) at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C) to allow the compound to distribute between the two phases.

- Separation: Centrifuge the mixture to achieve a clean and complete separation of the two phases.

- Quantification: Carefully sample from each phase and analyze the concentration of the compound using a validated analytical method, such as UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC [26].

- Calculation:

- Log P (for un-ionizable compounds): Log P = Log₁₀ ( [Compound]ₒcₜₐₙₒₗ / [Compound]ₐqᵤₑₒᵤₛ )

- Log D (for ionizable compounds at a specific pH): Log D = Log₁₀ ( [Total Compound]ₒcₜₐₙₒₗ / [Total Compound]ₐqᵤₑₒᵤₛ )

Predicting Food Effects Using the μFLUX System

Objective: To investigate the theoretical and experimental prediction of food effects on oral drug absorption, particularly for solubility-permeability-limited cases [28].

Background: Food intake significantly alters gastrointestinal conditions, notably increasing bile micelle concentrations (e.g., using FaSSIF/FeSSIF media). These micelles can solubilize drugs but also bind them, reducing the free fraction available for permeation [28].

Methodology:

- Theoretical Prediction (FaRLS): First, categorize the drug's absorption rate-limiting step (e.g., Solubility-Epithelial Membrane Permeation Limited, SL-E) based on its physicochemical properties to predict the potential food effect [28].

- In Vitro Simulation (μFLUX): a. Donor Chamber: Use fasted-state (FaSSIF) and fed-state (FeSSIF) simulated intestinal fluids as donor solutions to mimic the intestinal environment [28]. b. Acceptor Chamber: Use a physiologically relevant acceptor solution. c. Membrane: Employ a permeation membrane (e.g., artificial or cellular like Caco-2). d. Measurement: Measure the dissolution-permeation flux (JμFLUX) of the drug from the donor to the acceptor compartment over time under both FaSSIF and FeSSIF conditions [28].

- Data Analysis: Compare the flux profiles. For SL-E drugs, a marked increase in total drug concentration (C_D) in FeSSIF may not translate to a proportional increase in JμFLUX, as the free drug concentration remains unchanged. This result is consistent with a minimal positive food effect [28].

The Influence of Food and Formulation

Food intake can profoundly alter the absorption landscape, with effects that differ for hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds.

Mechanisms of Food Effects

Table 3: Food Effects on Drug Absorption

| Factor | Effect on Lipophilic Compounds | Effect on Hydrophilic Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Gastric Emptying | Delayed emptying can increase time for dissolution and absorption [29]. | Delayed emptying can delay the onset of absorption (increased Tₘₐₓ) [29]. |

| Bile Secretion | Major Positive Effect: Bile salts emulsify fats and form mixed micelles, significantly enhancing the solubilization and absorption of lipophilic compounds [28] [29]. | Minimal direct effect. |

| GI Fluid Volume & pH | Increased volume may dilute the drug. Elevated gastric pH can affect the dissolution of ionizable lipophilic compounds [29]. | Increased volume can dilute the drug, reducing the concentration gradient for passive diffusion [29]. |

| Lymphatic Transport | Significant Enhancement: High-fat meals stimulate chylomicron production, promoting lymphatic transport of highly lipophilic drugs (log P > ~5), bypassing first-pass metabolism [30]. | Not a relevant pathway. |

Advanced Formulation Strategies

To overcome poor bioavailability, advanced delivery systems can be employed.

- For Lipophilic Compounds: Lipid-based formulations such as Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS) and nanoemulsions enhance solubility and promote association with the intestinal lymphatic system [5] [30]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) also encapsulate drugs for protection and enhanced absorption [30].

- For Hydrophilic Compounds: Nanofibers produced by electrospinning offer high encapsulation capacity and sustained release, which can be beneficial for compounds that are unstable in the GI tract or have a narrow absorption window [5].

The absorption pathways of hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds are fundamentally distinct, shaping their journey through the LADME phases. Lipophilic compounds primarily rely on passive transcellular diffusion and can be strategically directed through the lymphatic system to enhance bioavailability. In contrast, hydrophilic compounds face greater membrane barriers and typically rely on paracellular or carrier-mediated transport. A deep understanding of these mechanisms, quantified by parameters like log P/D and investigated through protocols like the μFLUX system, is indispensable for researchers. This knowledge enables the rational prediction of food effects and the design of sophisticated formulation strategies, such as lipid nanoparticles and nanoemulsions, to optimize the delivery and efficacy of bioactive compounds and pharmaceuticals.

The Role of Gut Microbiota in the Metabolism of Dietary Polyphenols and Glycosides

The bioavailability and efficacy of dietary polyphenols are intrinsically linked to the metabolic capabilities of the gut microbiota. This in-depth technical guide explores the central role of commensal bacteria in the liberation, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (LADME) of these bioactive food compounds. We detail the specific enzymatic machinery possessed by key bacterial taxa that transforms complex polyphenols and glycosides into bioavailable metabolites, framing these interactions within the broader context of bioactive compound research. The document provides structured quantitative data, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualizations of critical pathways to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of nutrition, microbiology, and pharmacology.

Dietary polyphenols represent a vast class of secondary plant metabolites found in fruits, vegetables, tea, coffee, and wine, characterized by their phenolic structures. These compounds exist primarily as glycosides (conjugated with sugars) or in polymerized forms, which significantly influences their fate within the human body. The LADME framework—encompassing Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion—provides a systematic approach for understanding the pharmacokinetics of bioactive food compounds. For most polyphenols, fewer than 10% are absorbed in their native form in the small intestine; the remaining 90–95% progress to the colon, where the gut microbiota performs extensive biotransformation [31] [32] [33]. This colonic metabolism is not merely an elimination pathway but is arguably the most critical phase for generating systemically active metabolites that influence host physiology through anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective mechanisms [31] [33] [34].

The gut microbiota, often termed a "hidden organ," comprises trillions of microorganisms, predominantly the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. This consortium acts as a versatile bioreactor, encoding a diverse repertoire of enzymes that hydrolyze, cleave, and modify dietary polyphenols into absorbable metabolites. This review delineates the specific microbial transformations within the LADME continuum, provides experimental protocols for their study, and visualizes the complex metabolic networks, thereby offering a comprehensive resource for advancing research in this field.

Microbial Biotransformation within the LADME Phases

Liberation and Absorption

The initial liberation of polyphenols from the food matrix is influenced by mechanical processing and gastric digestion. However, the primary liberation of aglycones from their glycosylated forms occurs via microbial enzymes. Most polyphenol glycosides resist hydrolysis by human digestive enzymes but are susceptible to bacterial β-glucosidases, α-rhamnosidases, and other glycosidases [35] [34]. For instance, the flavonol quercetin-3-O-rutinoside (rutin) is hydrolyzed to its aglycone, quercetin, by bacterial β-glucosidases before further catabolism [34].

Site of Absorption: The small intestine absorbs a minor fraction of simple aglycones and low-molecular-weight polyphenols (e.g., certain isoflavones and flavanols). The vast majority of polyphenols, including polymerized proanthocyanidins and complex glycosides, reach the colon where microbial biotransformation occurs, and the resulting metabolites (e.g., simple phenolic acids) are absorbed across the colonic epithelium [31] [33].

Metabolism and Distribution

Once liberated, polyphenol aglycones undergo extensive metabolism by gut microbiota and host systems.

- Microbial Ring Fission and Dehydroxylation: Bacterial species such as Eubacterium ramulus and Flavonifractor plautii cleave the C-ring of flavonols like quercetin. Clostridium orbiscindens and Enterococcus casseliflavus are also involved in the degradation of various flavonoids, producing smaller phenolic acids like 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid [31] [35].

- Host Conjugation (Phase II Metabolism): After absorption, polyphenol metabolites travel to the liver via the portal vein where they undergo conjugation—methylation, sulfation, and glucuronidation [32] [34]. These conjugated forms enter systemic circulation and are distributed to target tissues, including the brain, as demonstrated for metabolites derived from grape seed polyphenol extract [31].

- Enterohepatic Recirculation: Some conjugated metabolites are excreted in bile, transported back to the small intestine, and may undergo deconjugation by microbial β-glucuronidases, facilitating reabsorption and prolonging their systemic presence [32].

Excretion

The final stage involves excretion of polyphenol metabolites and their conjugates, primarily via urine and feces. The profile of urinary metabolites serves as a key indicator of an individual's microbial metabolic capacity and polyphenol intake [31] [36].

Table 1: Key Bacterial Taxa and Enzymes in Polyphenol Biotransformation

| Polyphenol Class | Example Compounds | Key Metabolizing Bacterial Taxa | Microbial Enzymes Involved | Major Microbial Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonols | Quercetin, Rutin | Eubacterium ramulus, Clostridium orbiscindens, Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium spp. | β-Glucosidase, C-ring cleavage dioxygenases | 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, 3-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid, Homoprotocatechuic acid |

| Isoflavones | Daidzein, Genistein | Slackia isoflavoniconvertens, Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, Lactonifactor longoviformis | Glycosidases, Dehydroxylases, Reductases | Dihydrodaidzein, Equol, O-Desmethylangolensin (ODMA) |

| Ellagitannins | Punicalagins | Gordonibacter spp., Ellagibacter spp., Enterocloster spp. | Ellagitannin acyl hydrolases, Lactonases | Urolithins (A, B, C, D) |

| Flavan-3-ols | Catechins, Proanthocyanidins | Flavonifractor plautii | C-ring cleavage, Dehydroxylation | 5-(3',4'-Dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone, Phenylpropionic acids |

| Phenolic Acids | Chlorogenic acid, Caffeic acid | Various Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Esterases, Reductases | Dihydrocaffeic acid, 3-Hydroxy-3-phenylpropionic acid |

Table 2: Quantitative Overview of Polyphenol Bioavailability and Microbial Metabolism

| Parameter | Typical Range or Value | Notes and Methodological Context |

|---|---|---|

| Small Intestinal Absorption | 5 - 10% of intake [33] [34] | Applies to monomeric, dimeric, and some glycosylated forms; varies by compound. |

| Colonic Arrival for Microbial Metabolism | 90 - 95% of intake [33] | Includes polymeric and complex glycosylated polyphenols. |

| Major Classes of Microbial Metabolites | Phenolic acids, Phenyl-γ-valerolactones, Urolithins, Equol | Over 30 key metabolites routinely identified in urine and plasma [31] [36]. |

| Time to Peak Plasma Concentration (T~max~) for Microbial Metabolites | 6 - 24 hours post-consumption | Slower T~max~ compared to parent compounds, reflecting colonic fermentation time. |

| Interindividual Variation in Metabolite Production | High (e.g., 30-50% are equol producers) [36] | Dependent on individual gut microbiota composition ("metabotypes"). |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Polyphenol-Microbiota Interactions

In Vitro Simulation of Colonic Fermentation

This protocol models the human colon environment to study polyphenol metabolism under controlled conditions.

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Polyphenol Substrate: Standardized extract or purified compound (e.g., grape seed extract, chlorogenic acid).

- Inoculum: Fresh fecal samples from human donors (pooled from multiple individuals to represent diversity), homogenized in anaerobic phosphate buffer.

- Culture Medium: Complex medium like YCFA (Yeast Extract, Casitone, Fatty Acids) or MGAM (Medium with Gut Microbiota Accessible Nutrients), pre-reduced and maintained under anaerobic conditions (N₂/CO₂/H₂: 80/10/10).

- Anaerobic Chamber: To maintain an oxygen-free environment for all procedures.

Detailed Methodology:

- Preparation: Weigh the polyphenol substrate into fermentation vessels (e.g., serum bottles). Prepare the culture medium and reduce it by boiling and cooling under a constant stream of oxygen-free gas.

- Inoculation: Inside an anaerobic chamber, add a defined volume of the homogenized fecal inoculum (e.g., 10% v/v) to the medium. Transfer this mixture to the fermentation vessels containing the substrate.

- Fermentation: Incubate the vessels at 37°C with constant agitation for a predetermined period (typically 24-48 hours).

- Sampling: At regular intervals (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48h), aseptically withdraw samples for analysis.

- For Metabolite Analysis: Centrifuge samples (e.g., 13,000 rpm, 10 min) and collect the supernatant. Analyze using HPLC-MS/MS or GC-MS to identify and quantify polyphenol metabolites (e.g., phenolic acids, urolithins) [31] [32].

- For Microbiota Analysis: Pellet the microbial cells from the sample for DNA extraction. Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing (e.g., V3-V4 region) or shotgun metagenomics to track changes in microbial community structure and genetic potential [37].

Protocol for Identifying and Quantifying Microbial Metabolites in Biofluids

This method is critical for translating in vitro findings to human and animal studies.

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Biological Samples: Plasma, urine, or fecal samples from human/animal intervention studies.

- Internal Standards: Deuterated or otherwise isotopically labeled analogs of target metabolites (e.g., d₄-equol, ¹³C₆-phenolic acids).

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges: C18 or mixed-mode sorbents for sample clean-up and metabolite concentration.

- LC-MS/MS System: High-performance liquid chromatography coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw biofluids on ice. Precipitate proteins by adding a volume of cold acetonitrile (e.g., 1:3 sample:ACN ratio) containing the internal standards. Vortex, then centrifuge (e.g., 14,000 rpm, 15 min, 4°C) [31].

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): Condition the SPE cartridge with methanol and water. Load the supernatant from step 1. Wash with a mild acid or low-percentage methanol solution. Elute metabolites with a stronger solvent (e.g., methanol with 1% formic acid). Evaporate the eluent under a gentle stream of nitrogen and reconstitute in the initial mobile phase for LC-MS analysis.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Use a reverse-phase C18 column with a gradient elution of water and acetonitrile, both containing 0.1% formic acid, to separate metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Use optimized collision energies for each metabolite-transition pair for maximum sensitivity and selectivity.

- Data Analysis: Quantify metabolites by comparing the peak area ratio of the analyte to its corresponding internal standard against a calibration curve prepared from authentic standards [36] [32].

Visualization of Metabolic Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: LADME Pathway of Polyphenols

Diagram 2: Bidirectional Polyphenol-Microbiota Interaction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Investigating Polyphenol-Microbiota Interactions

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol Standards | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside, Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, Procyanidin B2, Chlorogenic Acid, Resveratrol | Analytical calibration; dosing in vitro and in vivo experiments. | Use high-purity (>95%) standards. Store as per manufacturer's instructions, often at -20°C, protected from light. |

| Microbial Metabolite Standards | Urolithin A, Urolithin B, (±)-Equol, 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, 5-(3',4'-Dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone | Quantification of microbial metabolites in biofluids and culture supernatants via LC-MS/MS. | Deuterated internal standards (e.g., d₄-equol) are crucial for accurate quantification. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Coy Laboratory Products, Baker Ruskinn | Provides an oxygen-free atmosphere (N₂/CO₂/H₂) for cultivating obligate anaerobic gut bacteria. | Critical for maintaining the viability of strict anaerobes during all procedures. |

| Specialized Culture Media | YCFA (Yeast Extract, Casitone, Fatty Acids), MGM (Mucin-based Gut Microbiota Medium), MGAM | Supports the growth of a diverse and representative gut microbial community in vitro. | Must be pre-reduced before inoculation. Can be supplemented with polyphenols as the primary carbon source. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit | Isolation of high-quality genetic material from complex fecal or culture samples for microbiome analysis. | Protocols should include mechanical lysis steps (bead beating) to efficiently lyse Gram-positive bacteria. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | 515F/806R (targeting V4 region), 341F/785R (targeting V3-V4 regions) | Amplicon sequencing to profile and compare microbial community structure. | Choice of primer set influences taxonomic resolution and biases. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Agilent, Waters, Sciex HPLC systems coupled to triple quadrupole mass spectrometers | Targeted identification and highly sensitive quantification of polyphenols and their metabolites. | MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) mode is the gold standard for targeted quantification. |

The intricate partnership between dietary polyphenols and the gut microbiota is a cornerstone of the LADME profile for these bioactive compounds. Understanding the specific bacterial taxa, their enzymatic arsenal, and the resulting metabolite profiles is no longer a niche interest but a fundamental requirement for advancing nutritional science, pharmacology, and the development of functional foods and drugs. The high interindividual variation in microbial metabolic capacity, conceptualized as "metabotypes" (e.g., equol producers vs. non-producers, urolithin metabotypes A, B, and 0), presents both a challenge and an opportunity [36]. It complicates blanket dietary recommendations but opens the door to personalized nutrition strategies where diets and interventions are tailored to an individual's gut microbial makeup.

Future research must focus on closing the identified knowledge gaps. This includes a more complete mapping of the microbial gene clusters responsible for specific biotransformations, a deeper understanding of the ecological principles governing the competition for polyphenols as substrates in the gut, and large-scale long-term human intervention studies that link specific metabotypes to tangible health outcomes. The tools, protocols, and frameworks presented in this document provide a foundation for these endeavors. Ultimately, leveraging the gut microbiota to maximize the health benefits of dietary polyphenols represents a paradigm shift in our approach to disease prevention and health promotion, firmly rooting the LADME of bioactives within the context of our personal microbial ecosystem.

The LADME framework—Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion—describes the pharmacokinetic journey of bioactive food compounds (BFCs) from ingestion to elimination. Understanding this pathway is crucial for predicting the health benefits of functional foods and dietary supplements. However, a critical challenge in nutritional science and drug development is the significant inter-individual variability (IIV) observed in each LADME phase, which causes identical doses of bioactive compounds to produce markedly different physiological responses and health outcomes across individuals [38]. This variability stems from a complex interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, primarily an individual's genetic makeup, the composition and function of their gut microbiome, and their physiological status [39] [38]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence to provide an in-depth technical guide on the determinants of IIV in the LADME of BFCs, framing this discussion within the broader context of personalized nutrition and drug development. We present quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visual frameworks to equip researchers and scientists with the tools to dissect and address these variabilities in their work.

Systematic analyses of human cohorts have begun to quantify the relative contribution of different factors to the variability observed in the plasma metabolome, which serves as a functional readout of LADME processes. A comprehensive study of 1,368 individuals quantified the proportion of inter-individual variation in the plasma metabolome explained by diet, genetics, and the gut microbiome [39]. The findings provide a foundational understanding of how these factors dominate the metabolism of different classes of compounds.

Table 1: Proportion of Metabolome Variance Explained by Key Factors in a Dutch Cohort (n=1,368) [39]

| Explanatory Factor | Percentage of Variance Explained (Whole Metabolome) | Number of Metabolites Dominantly Associated | Median Explained Variance per Metabolite (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | 9.3% | 610 | 0.4% - 35% |

| Gut Microbiome | 12.8% | 85 | 0.7% - 25% |

| Genetics | 3.3% | 38 | 3% - 28% |

| Intrinsic Factors (Age, Sex, BMI) & Smoking | 4.9% | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Combined Model | 25.1% | 733 metabolites significantly associated with ≥1 factor | Not Applicable |

Another study focusing on impaired glucose control highlighted that the gut microbiome's influence on the blood metabolome can be even more pronounced in certain disease contexts, accounting for nearly one-third of the variance, which is twice that observed in healthy populations [40]. These quantitative assessments underscore that for a majority of metabolites, dietary habits and gut microbiome composition are more dominant explanatory factors than host genetics, although the latter can be decisive for specific compounds.

The Genetic Determinants of LADME Variability

Key Mechanisms and Polymorphisms

Genetic polymorphisms in genes encoding enzymes and transporters involved in the ADME of xenobiotics are a well-established source of IIV. For bioactive food compounds, this is particularly relevant for phase I and II metabolism enzymes. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes for enzymes like Cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms, UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), and sulfotransferases (SULTs) can lead to altered enzyme activity, creating distinct metabotypes (e.g., poor vs. extensive metabolizers) [38]. For instance, studies on flavanones (abundant in citrus) and flavan-3-ols (found in tea and cocoa) have shown that inter-individual differences in their metabolism and the resulting plasma metabolite profiles are influenced by polymorphisms in these enzymes [38].

Experimental Protocols for Genotyping and Phenotyping

Objective: To identify genetic polymorphisms (mQTLs - metabolite quantitative trait loci) associated with inter-individual variation in the metabolism of specific BFCs. Methodology:

- Cohort Design: Recruit a large (n > 500), well-phenotyped human cohort. The Lifelines DEEP (LLD) and Genome of the Netherlands (GoNL) cohorts are prime examples [39].

- Genotyping: Perform high-throughput genotyping (e.g., using genome-wide arrays followed by imputation) to obtain data on millions of genetic variants for each participant.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Collect plasma or serum samples after a controlled dose of the BFC of interest or under fasting conditions. Use untargeted metabolomics platforms like Flow-Injection Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (FI-MS) or Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to quantify a wide range of metabolites [39].

- QTL Mapping: Conduct an association analysis between each genetic variant and the plasma level of each metabolite. This is typically done using linear regression models, adjusting for covariates like age, sex, and population structure. Significance thresholds are corrected for multiple testing (e.g., False Discovery Rate, FDR < 0.05) [39]. Key Output: A list of significant genetic variant-metabolite pairs (mQTLs), indicating which genetic loci explain a significant portion of the variance in the levels of specific metabolites.

The Gut Microbiome as a Dominant Modifier of LADME

Role in Metabolism and Bioavailability

The gut microbiome is a pivotal metabolic organ that profoundly influences the LADME of BFCs, particularly the liberation and metabolism phases for compounds that are otherwise poorly digested by human enzymes. Its role is so significant that it creates qualitative differences in metabolic outcomes, leading to the classification of individuals into producer/non-producer metabotypes [38]. This is best exemplified by:

- Ellagitannins (found in pomegranates and berries): Gut microbial metabolism produces urolithins. Individuals are stratified into urolithin metabotypes (UMA, UMB, UMC), defined by their ability to produce certain urolithins, which in turn influences the compounds' potential health benefits [38].

- Isoflavones (e.g., daidzein in soy): A portion of the population possesses a gut microbiome capable of converting daidzein to equol or O-desmethylangolensin (O-DMA). Equol producers may derive greater cardiovascular and hormonal benefits from soy consumption [38].

- Resveratrol: The production of the metabolite lunularin is another example of a microbiome-dependent, binary producer/non-producer metabotype [38].

Furthermore, microbiome-dominant metabolites include many uremic toxins and other compounds whose circulating levels are primarily determined by microbial activity [39].

Analytical Workflow for Microbiome-Metabolome Association Studies

Objective: To identify and validate associations between specific gut microbial taxa/functions and plasma metabolites, establishing the microbiome as a causal factor. Methodology:

- Multi-omics Data Collection: For each participant in a cohort, collect fecal samples for metagenomic sequencing (to profile gut microbial species and genes) and plasma/serum for metabolomic profiling [39] [40].

- Machine Learning Modeling: Use advanced algorithms like Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT) or Random Forest to build models that predict the plasma level of each metabolite based on microbial features (e.g., Metagenomic Species - MGSs). The model's performance (e.g., R²) indicates the proportion of metabolite variance explained by the microbiome [40].

- Cross-Validation and Robustness Checks:

- In Vivo Validation: Compare metabolite levels in Germ-Free (GF) mice versus Conventionally Raised (CONV-R) mice. A significant difference in a metabolite's abundance confirms its microbial origin [40]. Key Output: A validated list of microbiome-associated metabolites and the specific microbial taxa or pathways responsible for their production or modulation.

Diagram 1: Workflow for identifying microbiome-metabolite links.

Physiological and Non-Genetic Host Factors

Beyond genetics and the microbiome, an individual's physiological status and life stage introduce significant variability in LADME. The concept of "biome-aging" has been proposed to describe aging-associated transformations in the gut microbiome and host physiology that collectively impact metabolism [41]. Key age-related changes include:

- Immunosenescence and Inflammaging: Age-associated chronic, low-grade inflammation ("inflammaging") can disrupt gut barrier integrity and microbiome composition, altering the absorption and distribution of BFCs [41].

- Decline in Gastrointestinal Function: With age, there is a reduction in gastric acid production (leading to achlorhydria), decreased intestinal epithelial cell function, impaired gut motility, and reduced secretions from accessory organs like the pancreas. These changes affect the liberation, absorption, and subsequent metabolism of BFCs [41].

- Polypharmacy and Malnutrition: Common in elderly populations, polypharmacy can severely alter gut microbiome diversity and function. Coupled with age-related reductions in appetite and nutrient absorption, this leads to a decline in beneficial microbes that produce essential metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and vitamins [41].

Other host factors such as sex, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity levels have also been identified as contributors to IIV in the metabolism and bioavailability of various (poly)phenols, although their effects are often compound-specific and less characterized than those of the microbiome [38].

Integrated Workflow for Studying LADME Variability