Machine Learning for Eating Behavior Classification: Advanced Algorithms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of machine learning (ML) applications for classifying and predicting eating behaviors.

Machine Learning for Eating Behavior Classification: Advanced Algorithms, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of machine learning (ML) applications for classifying and predicting eating behaviors. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational rationale for using ML, details key algorithms from decision trees to deep learning, and addresses critical methodological challenges like data heterogeneity and model interpretability. The content further synthesizes empirical evidence on model validation and performance comparisons, offering a roadmap for integrating these computational approaches into biomedical research and clinical intervention development to advance personalized nutrition and eating disorder therapeutics.

The Foundation of ML in Eating Behavior: Core Concepts and Research Imperatives

The study of eating behaviors presents a significant challenge due to the complex, multi-factorial, and highly personalized nature of the mechanisms that drive food consumption. Traditional research approaches, which often examine risk factors in isolation or assume homogeneity within broad groups like Body Mass Index (BMI) categories, have yielded inconsistent findings and limited applicability to real-world settings [1]. This has highlighted an urgent need for more innovative methodologies. Machine learning (ML) emerges as a powerful tool to address this complexity, offering the capacity to analyze high-dimensional, multimodal data and uncover subtle, data-driven patterns that escape conventional statistics. This document details the application of ML frameworks, protocols, and data sources for advancing the classification and understanding of eating behaviors within clinical and research contexts.

ML Approaches and Quantitative Performance

Machine learning techniques are being applied across diverse data modalities to classify eating behaviors, predict consumption, and identify underlying risk factors. The performance of these models varies based on the data source and the specific classification task.

Table 1: Performance of ML Models in Eating Behavior Classification

| Data Modality | ML Task | Algorithm(s) Used | Reported Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist-worn Inertial Sensor | Feeding Gesture Count & Overeating Detection | Motif-based Time-point Fusion, Random Forest (n=185 trees) | 94% accuracy in gesture count; F-measure=0.75 for gesture classification; RMSE of 2.9 gestures | [2] |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) / Smartphone App | Prediction of Food Group Consumption (servings per eating occasion) | Gradient Boost Decision Tree, Random Forest | MAE: Vegetables (0.3), Fruit (0.75), Dairy (0.28), Grains (0.55), Meat (0.4), Discretionary Foods (0.68) | [3] |

| Multi-sensor (Video & IMU) | Intake Gesture Detection | Deep Learning Models | F₁ = 0.853 (Discrete dish, Video); F₁ = 0.852 (Shared dish, Inertial data) | [4] |

| EMA / Smartphone App | Unhealthy Eating Event Prediction | Decision Tree (tailored for longitudinal data) | Decreasing trend in rule activation during intervention; successful user profiling | [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and rigorous application of ML in eating behavior research, the following section outlines standardized protocols for key methodological approaches.

Protocol: Multimodal Clustering for Precision Health

This protocol is designed to identify data-driven subgroups of individuals based on shared patterns in multimodal data, moving beyond traditional BMI-based categories [1].

A. Study Design and Timeline: A longitudinal study with data collection at three time points over a six-month period to assess weight and eating outcomes.

B. Participant Recruitment:

- Target Cohort: Young adults (e.g., 18-30 years) with a varying range of BMI.

- Exclusion Criteria: Current or past eating disorders to study normative and at-risk patterns without the confounds of clinical pathology.

C. Data Collection and Modalities:

- Comprehensive Baseline Assessment:

- Self-Report: Questionnaires on psychological traits (e.g., emotional, stress, and disinhibited eating), emotion regulation, personality, and sleep habits.

- Electrophysiological Data: Electroencephalography (EEG) experiment to measure neurocognitive responses to food cues (Food Cue Reactivity - FCR) and during craving regulation tasks.

- Time Series Dynamic Data: A one-week Experience Sampling Method (ESM) study using a smartphone application. Participants receive random prompts and event-based surveys (e.g., prior to eating) to report real-time data on emotions, location, social context, activity, and food cravings/consumption.

- Follow-up Assessments: Repeat key measures at predetermined intervals (e.g., 3 and 6 months) to track changes in outcomes.

D. Machine Learning and Analysis:

- Data Integration: Combine self-report, EEG, and ESM data into a multimodal feature set.

- Clustering: Apply unsupervised machine learning techniques (e.g., k-means, hierarchical clustering) to identify distinct participant clusters with unique profiles across the collected modalities.

- Validation: Correlate cluster membership with weight change and eating outcomes after six months.

- Interpretation: Use Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), to identify which features (e.g., stress reactivity, neural response to food cues, sleep quality) are most influential in defining each cluster [1] [3].

Protocol: Inertial Sensor-Based Overeating Detection

This protocol focuses on using wrist-worn sensors to passively detect feeding gestures and identify episodes of overeating [2].

A. Experimental Setup and Sensor Configuration:

- Device: A wrist-worn 6-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU) containing an accelerometer and gyroscope.

- Sampling Frequency: A minimum of 31 Hz is recommended for effective gesture recognition [2].

- Body Location: Dominant or non-dominant wrist, with consistency across participants noted.

B. Experimental Paradigms:

- Highly Structured Test: Participants perform scripted "pretend" eating gestures in a lab setting to establish an upper bound for gesture classification performance.

- Structured Test with Confounds: Participants follow a defined eating protocol while also performing other scripted, non-eating activities (e.g., brushing hair, scratching face) to test classification robustness.

- Unstructured Overeating Test: Participants are induced to overeat (e.g., after feeling full) in a naturalistic setting like watching television while consuming their favorite foods. This tests the framework in real-world conditions. Overeating can be defined using the Harris-Benedict principle to estimate energy needs.

C. Data Processing and Machine Learning Framework (Motif-Based):

- Motif Extraction: Identify recurring, representative patterns (motifs) from ground-truth segments of feeding gestures.

- Clustering: Use K-Spectral Centroid Clustering on these motifs to create a set of motif templates.

- Motif Matching: Employ a symbolic aggregate approximation (SAX) method to search for and candidate segments in the continuous data stream that match the templates.

- Feature Extraction & Classification: Extract features from the candidate segments and use a Random Forest classifier to distinguish feeding from non-feeding gestures.

- Time-Point Fusion: Apply a decision-level fusion technique that combines results from multiple overlapping window segments to finalize the detection and count of feeding gestures.

D. Outcome Measurement:

- The primary outcome is the feeding gesture count, which has been shown to correlate with caloric intake (e.g., r=.79) [2].

- This count is used to predict whether an eating episode constitutes overeating based on the predetermined energy threshold.

This section catalogs essential datasets, instruments, and computational tools for implementing ML research in eating behavior.

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for ML in Eating Behavior

| Resource Name | Type | Key Features / Variables | Primary Application / Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OREBA Dataset (Objectively Recognizing Eating Behaviour and Associated Intake) | Multi-sensor Dataset | Synchronized frontal video + IMU (accelerometer, gyroscope) for both hands; 9,069 intake gestures from 200+ participants. | Benchmarking and training models for intake gesture detection in structured and unstructured (shared meal) settings. | [4] |

| Obesity Levels Dataset (UCI Repository) | Multivariate Demographic & Habit Data | 16 features including Age, Height, Weight, family history, FAVC (high caloric food), FCVC (vegetable consumption), etc. | Classification & clustering tasks for obesity level estimation (Insufficient Weight to Obesity Type III). | [6] |

| Wrist-worn Inertial Sensor (e.g., 6-axis IMU) | Instrument | Accelerometer and gyroscope; recommended sampling frequency ≥31 Hz. | Passive, continuous detection of feeding gestures and eating episodes in free-living environments. | [2] |

| Experience Sampling Method (ESM) / EMA Mobile App (e.g., "Think Slim", "FoodNow") | Software & Data Collection Tool | Real-time assessment of emotions, location, social context, activity, food cravings, and food intake via smartphone. | Capturing contextual, in-the-moment data on eating behaviors and antecedents, minimizing recall bias. | [5] [3] |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Libraries (e.g., SHAP) | Computational Tool | Model interpretation framework that calculates the contribution of each feature to a model's prediction. | Interpreting complex ML models to identify key psychological, contextual, or physiological drivers of eating behavior. | [1] [3] |

The application of machine learning (ML) to classify eating behaviors represents a paradigm shift in nutritional science and preventive medicine. This field moves beyond traditional epidemiological methods by leveraging computational power to identify complex, multi-factorial patterns from high-dimensional data. Research demonstrates that ML models can accurately categorize conditions ranging from general obesity to specific overeating phenotypes, achieving high performance metrics. For instance, integrated with Explainable AI (XAI), these models achieve accuracies up to 93.67% in predicting obesity levels and mean AUROCs of 0.86 in detecting overeating episodes [7] [8]. This progress signals a new era of data-driven, personalized interventions. This document outlines the essential application notes and experimental protocols for researchers developing ML algorithms within this classification scope, providing a toolkit for robust and interpretable research.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Machine Learning Models in Eating Behavior Classification

| Study Focus | Best-Performing Model(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity Level Prediction | CatBoost [7] | Accuracy: 93.67%, Superior Precision, F1 Score, and AUC [7] | Physical activity, dietary patterns, age, weight, height [7] |

| Overeating Episode Detection | XGBoost [8] | AUROC: 0.86, AUPRC: 0.84, Brier Score Loss: 0.11 [8] | Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), passive sensing (chews, bites) [8] |

| Obesity Susceptibility (ObeRisk) | Ensemble (LR, LGBM, XGB, etc.) with Majority Voting [9] | Accuracy: 97.13% ± 0.4, Precision: 95.7% ± 0.5, Sensitivity: 95.4% ± 0.4 [9] | Personal, behavioral, and lifestyle data [9] |

| HFSS Snacking Prediction | Feed Forward Neural Network (Marginal Advantage) [10] | Mean Absolute Error: ~17 minutes (on time to next snack) [10] | Previous snacking instances, time, day, location [10] |

| Complementary Feeding Practices | Random Forest [11] | Accuracy: 91%, AUC: 96% [11] | Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data [11] |

Table 2: Identified Key Predictors and Phenotypes Across Studies

| Category | Identified Feature or Phenotype | Description / Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Key Predictors for Obesity | Age, Weight, Height, Specific Food Patterns [7] | Found to be key predictors in global obesity level prediction models [7]. |

| Key Predictors for Overeating | Perceived Overeating, Number of Chews, Light Refreshment, Loss of Control, Chew Interval [8] | Top five predictive features in a feature-complete model [8]. |

| Overeating Phenotypes | Take-out Feasting, Evening Restaurant Reveling, Evening Craving, Uncontrolled Pleasure Eating, Stress-driven Evening Nibbling [8] | Five distinct clusters identified via semi-supervised learning on EMA-derived features [8]. |

| Key Predictors for Child Feeding | Maternal Education, Wealth Status, Current Breastfeeding Status, Sex of Child, Access to Health Facility [11] | Key determinants of appropriate complementary feeding practices in Sub-Saharan Africa [11]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing an Explainable AI (XAI) Framework for Obesity Level Classification

This protocol is based on the methodology that achieved 93.67% accuracy using CatBoost, integrated with SHAP and LIME for explainability [7].

1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Data Collection: Utilize a dataset encompassing physical activity, detailed dietary patterns, and anthropometric measurements (e.g., age, weight, height) from a minimum of 498 participants [7].

- Data Cleansing: Address missing values using appropriate imputation techniques (e.g., K-Nearest Neighbors imputation). Encode categorical variables using One-Hot Encoding [11].

- Feature Scaling: Apply feature scaling to normalize the data. Use MinMaxScaler or Standard Scaler to bring all features to a similar range, which is critical for models sensitive to feature magnitude [11].

- Train-Test Split: Split the dataset into training and testing sets using an 80:20 ratio. Employ 10-fold cross-validation to robustly assess model performance and mitigate overfitting [11].

2. Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Model Selection: Train and compare a diverse set of six ML models: Bernoulli Naive Bayes, CatBoost, Decision Tree, Extra Trees Classifier, Histogram-based Gradient Boosting, and Support Vector Machine [7].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Tune the hyperparameters for each model using the Random Search methodology to identify the optimal configuration for performance [7].

3. Model Evaluation and Interpretation:

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate model effectiveness using repeated holdout testing. Key metrics include Accuracy, Precision, F1 Score, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) [7].

- Global Explainability: Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to the best-performing model (e.g., CatBoost) to generate global feature importance measures, understanding the overall driver of model predictions [7].

- Local Explainability: Apply LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to create instance-level explanations, clarifying the rationale behind individual predictions [7].

- XAI Comparison: Compare the outputs of SHAP and LIME, noting that LIME may show superior fidelity for local explanations, while SHAP may offer improved sparsity and consistency across models [7].

Protocol 2: Semi-Supervised Identification of Overeating Phenotypes from Digital Longitudinal Data

This protocol details the process of identifying five distinct overeating phenotypes from meal-level observations, achieving a cluster purity of 81.4% [8].

1. Multi-Modal Data Collection:

- Participant Monitoring: Monitor participants in free-living settings over an extended period (e.g., 657 days). Collect a minimum of 2300 meal-level observations using a combination of tools [8].

- Objective Passive Sensing: Use an activity-oriented wearable camera to record eating episodes. Manually or automatically label micromovements such as number of bites, chews, and chew intervals from the footage [8].

- Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA): Administer brief surveys via a mobile app before and after meals to gather psychological (e.g., hunger, loss of control, pleasure) and contextual (e.g., location, social setting, time) information in real-time [8].

- Dietary Recall: Supplement with dietitian-administered 24-hour dietary recalls for ground-truth energy intake and meal composition data [8].

2. Supervised Overeating Detection:

- Model Training: Train an XGBoost model using the collected features (both EMA and passive sensing) to classify individual meals as "overeating" or "normal eating" [8].

- Model Calibration: Apply post-calibration techniques such as Platt’s scaling (sigmoid method) to better align the model's predicted probabilities with the observed outcomes [8].

- Feature Analysis: Use SHAP analysis to identify the top predictive features for overeating (e.g., perceived overeating, number of chews, loss of control) [8].

3. Phenotype Clustering:

- Data Filtering: Remove non-caloric meals to ensure the analysis focuses on substantive eating episodes [8].

- Semi-Supervised Clustering: Apply a semi-supervised clustering pipeline to the entire dataset of meals. Use the silhouette score to determine the optimal number of clusters [8].

- Cluster Definition and Validation: Define an "overeating cluster" by setting a threshold for the proportion of overeating instances (e.g., >0.05). Validate the final clustering solution using metrics like mean purity, cumulative proportion of overeating instances, and entropy score. Confirm results with a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) [8].

- Phenotype Characterization: Conduct a Z-score analysis on contextual and psychological factors within each cluster. Assign intuitive phenotype labels (e.g., "Stress-driven Evening Nibbling") based on features with z-scores exceeding a predefined cut-off (e.g., |z| ≥ 1) [8].

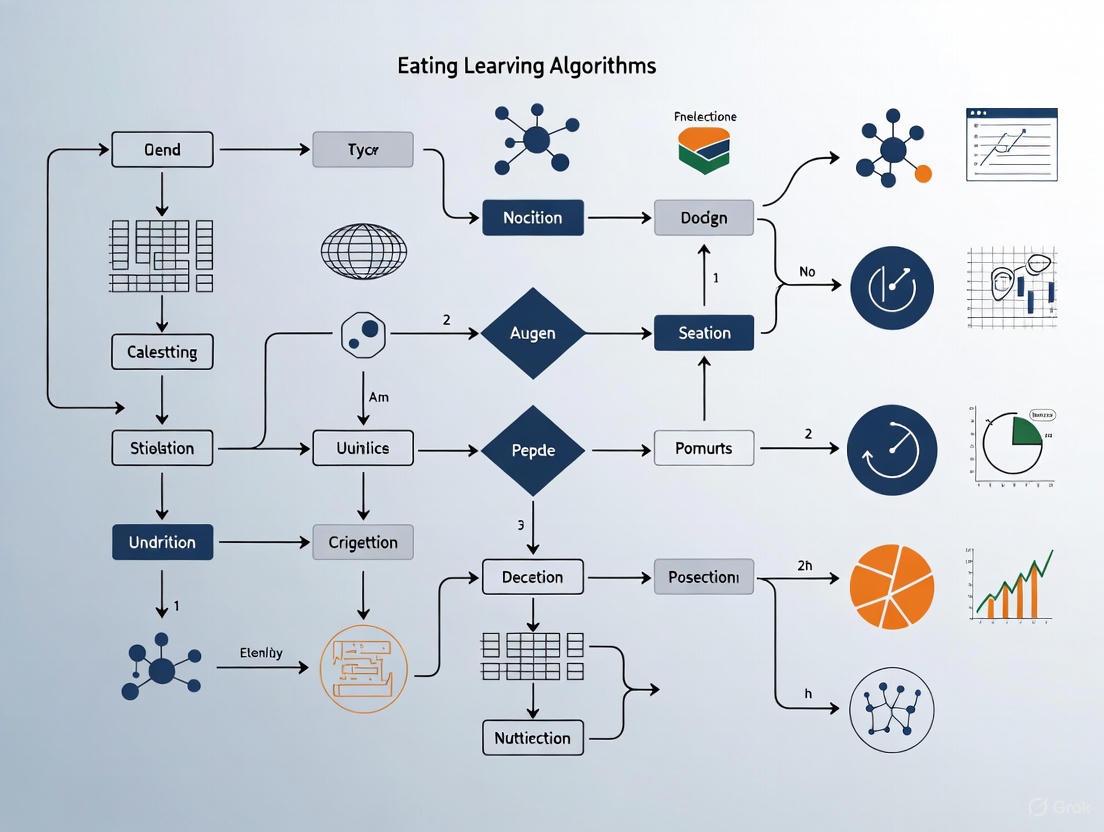

Visualizing the Machine Learning Workflow for Eating Behavior Classification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing and interpreting ML models in eating behavior research, as described in the protocols above.

Diagram 1: Integrated ML Workflow for Eating Behavior Classification. This flowchart outlines the key stages from data collection to model outputs, highlighting both supervised prediction and semi-supervised phenotype discovery pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Eating Behavior ML Research

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Activity-Oriented Wearable Camera | Passively captures objective visual data of eating episodes and environment. | Manual labeling of micromovements (bites, chews) for passive sensing analysis [8]. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) | Mobile app-based surveys delivered in real-time to capture psychological and contextual states. | Gathering pre- and post-meal data on hunger, emotion, location, and social context [8]. |

| Snack Tracker App | A purpose-specific mobile application for self-reporting instances of specific eating behaviors. | Enabling participants to log HFSS snacking occurrences with associated location data [10]. |

| XGBoost Algorithm | An efficient and scalable implementation of gradient boosting for supervised learning. | Achieving state-of-the-art performance in overeating detection and obesity risk prediction [8] [9]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game theory-based method to explain the output of any machine learning model. | Generating global feature importance plots to identify top predictors of overeating (e.g., number of chews) [7] [8]. |

| UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) | A dimensionality reduction technique for visualizing high-dimensional data in 2D or 3D. | Providing visual confirmation of cluster separability in identified overeating phenotypes [8]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | A feature selection method that recursively removes the least important features. | Systematically identifying the most predictive variables from a large set of demographic and health survey data [11]. |

| Tomek Links & Random Oversampling | Combined sampling techniques to handle class imbalance in datasets. | Addressing the imbalance between "appropriate" and "inappropriate" complementary feeding classes [11]. |

Behavioral phenotyping leverages digital technologies to objectively quantify human behavior in naturalistic settings. Within eating behavior research, the integration of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), wearable sensors, and machine learning algorithms creates a powerful data ecosystem for classifying behaviors, identifying individual patterns, and developing personalized interventions. This application note details the core components of this ecosystem, provides validated experimental protocols for its implementation, and summarizes key quantitative findings from seminal studies, offering researchers a framework for advancing machine learning-based eating behavior classification.

The rise of mobile and sensing technologies provides an unprecedented opportunity to capture rich, longitudinal data on human behavior in real-time. Digital phenotyping, defined as the "moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype in situ using data from personal digital devices" [12], is transforming behavioral research. In the specific domain of eating behavior, this approach addresses critical limitations of traditional self-report methods, which are prone to recall bias and inaccuracies [13] [14].

A comprehensive data ecosystem for behavioral phenotyping in eating behavior research rests on three pillars: Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) for active data collection on states and contexts, multi-modal sensors for passive data collection on behavior and physiology, and machine learning algorithms to synthesize these data streams into meaningful digital biomarkers and classification systems. This synergy enables a move from one-size-fits-all models to personalized, data-driven insights, which is a core principle of P4 (Predictive, Preventive, Personalized, Participatory) medicine [15]. This document outlines the protocols and applications of this integrated ecosystem for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Ecosystem Components and Their Roles

The following table summarizes the key technologies that constitute the modern behavioral phenotyping ecosystem.

Table 1: Core Components of a Behavioral Phenotyping Data Ecosystem

| Component | Data Type | Key Function | Example Technologies | ML Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA / Experience Sampling [5] | Active, Self-report | Collects real-time data on psychological state, context, and food consumption. | Smartphone apps (e.g., "Think Slim," "FoodNow") | Provides ground-truthed labels for supervised learning; identifies contextual rules for unhealthy eating. |

| Accelerometers [14] [16] | Passive, Behavioral | Detects motion patterns associated with eating (e.g., wrist/neck movement for bites). | Wrist-worn wearables (e.g., Fitbit), neck-worn sensors (e.g., NeckSense) | Activity classification (eating vs. non-eating); feature extraction for bite counting and chewing rate. |

| Acoustic Sensors [13] | Passive, Behavioral | Captures sounds of chewing and swallowing. | Microphones (often in necklace form) | Audio signal processing to detect and classify ingestive events. |

| Computer Vision [13] [17] | Passive, Behavioral | Automatically identifies food type and estimates portion size. | Smartphone cameras, body-worn cameras (e.g., HabitSense) | Food recognition and nutrient estimation via image analysis. |

| Physiological Sensors [15] | Passive, Physiological | Monitors physiological correlates of eating and emotion (e.g., heart rate, EDA). | Smartwatches, ECG patches | Identifies psychophysiological states (e.g., stress) that predict eating episodes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrated EMA and Sensor Study for Unhealthy Eating Prediction

This protocol is adapted from the "Think Slim" study, which balanced generalization and personalization using machine learning [5].

1. Objective: To collect a multimodal dataset for developing a machine learning pipeline that predicts unhealthy eating events and clusters participants into behavioral phenotypes.

2. Materials:

- Smartphone with a custom EMA application (e.g., "Think Slim").

- Wearable accelerometer (e.g., wrist- or neck-worn).

3. Procedure:

- Participant Setup: Recruit adult participants and install the EMA app on their smartphones. Fit them with the wearable sensor.

- Data Collection (Longitudinal): Over a multi-week period, collect data through two primary EMA methods:

- Signal-Contingent Sampling: The app notifies participants at pseudo-random times (e.g., 8 times per day) to report their current emotional state, location, and activity.

- Event-Contingent Sampling: Participants are instructed to initiate a report in the app immediately before eating, providing additional details on the food items about to be consumed.

- Data Annotation: Food items are categorized as "healthy" or "unhealthy" based on a pre-defined classification of selected food icons/pictures.

4. Data Preprocessing:

- Feature Engineering:

- Aggregate and discretize mood states (e.g., positive emotions to {Low, Mid, High}; negative emotions to {No, Yes}).

- Discretize location, activities, and thoughts into categorical values.

- Create time-related features (time of day, weekend vs. weekday).

- Algorithm Application & Output:

- Clustering for Phenotyping: Apply Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering to the processed EMA data to identify distinct participant profiles based on their eating behavior.

- Classification for Prediction: Train a decision tree classifier (tailored for longitudinal data) using the contextual features (emotion, location, time, etc.) to predict the occurrence of an "unhealthy eating" event.

- Intervention: Use the derived classification rules to provide users with semi-tailored feedback and warnings prior to predicted unhealthy eating events.

The logical workflow of this protocol, from data collection to intervention, is outlined below.

Protocol 2: In-Field Eating Detection Using Wearable Sensors

This protocol summarizes best practices for validating wearable sensor systems in free-living conditions, as per the scoping review by [14].

1. Objective: To validate the performance of one or more wearable sensors for automatically detecting eating activity in naturalistic, free-living settings.

2. Materials:

- One or more wearable sensors (e.g., accelerometer on wrist, acoustic sensor on neck).

- A system for collecting ground-truth data (e.g., a smartphone app for self-reported meal logging, a body-worn camera like HabitSense [17]).

3. Procedure:

- Participant Setup: Recruit participants and equip them with the sensor suite. Ensure the devices are comfortable for extended wear.

- Ground-Truth Collection:

- Method A (Self-Report): Participants use a smartphone app to log the start and end time of all eating and drinking occasions.

- Method B (Objective): Use a privacy-sensitive bodycam (e.g., HabitSense) that records only when food is present to obtain objective, visual ground truth [17].

- Data Collection Period: Participants go about their daily lives without restrictions for a predefined period (e.g., several days to two weeks). The sensors passively collect data while ground truth is recorded in parallel.

4. Data Analysis:

- Signal Processing: Preprocess raw sensor data (e.g., filtering, segmentation into time windows).

- Model Training & Validation: Extract features from the sensor data windows and train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for time-series data [16]) to detect eating activities. The ground-truth data provides the labels.

- Performance Evaluation: Calculate standard evaluation metrics including Accuracy, Precision, Sensitivity (Recall), and F1-score to report the classifier's performance [14].

The workflow for this validation protocol is captured in the following diagram.

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Findings

The application of machine learning within this ecosystem has yielded robust quantitative results across various studies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Selected ML Applications in Behavioral Phenotyping

| Study Focus | ML Algorithm | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle Behavior Classification [16] | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | Precision, Sensitivity, F1-Score | Resting: 89% Precision, 81% Sensitivity, 85% F1-Score.Eating: 79% Precision, 88% Sensitivity, 83% F1-Score. |

| Predicting Food Consumption [18] | Gradient Boost Decision Tree, Random Forest | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | MAE per eating occasion: Vegetables (0.3 servings), Fruit (0.75), Dairy (0.28), Grains (0.55), Meat (0.4), Discretionary Foods (0.68). |

| Overeating Pattern Discovery [17] | Unsupervised Learning (Type not specified) | Pattern Identification | Identified 5 distinct overeating patterns: Take-out Feasting, Evening Restaurant Reveling, Evening Craving, Uncontrolled Pleasure Eating, Stress-driven Evening Nibbling. |

| Unhealthy Eating Prediction [5] | Decision Tree, Hierarchical Clustering | Intervention Effectiveness | A decreasing trend in rule activation was observed, indicating a reduction in unhealthy eating events after personalized feedback. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Behavioral Phenotyping Research

| Category / Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EMA / Active Data Collection | ||

| Custom Smartphone App | Presents EMA surveys and collects self-reported data in real-time. | "Think Slim" [5], "FoodNow" app for dietary intake [18]. Should support random and event-contingent sampling. |

| Wearable Sensors | ||

| Triaxial Accelerometer | Measures body movement to detect eating gestures, chew counts, and general activity. | Worn on the wrist [14] or neck (e.g., NeckSense [17]). LSM9DS1 sensor used in cattle study [16]. |

| Acoustic Sensor (Microphone) | Captures audio signals of chewing and swallowing. | Often integrated into a necklace form factor [13]. |

| Activity-Oriented Camera (AOC) | Provides objective visual ground truth for eating events while preserving privacy. | "HabitSense" uses thermal sensing to trigger recording only when food is present [17]. |

| Data Analysis & ML | ||

| LSTM Network | Classifies time-series sensor data; effective for behaviors with temporal dynamics like eating. | Achieved high precision for classifying resting and eating behaviors in cattle [16]. |

| Decision Tree | Generates interpretable rules for classifying events (e.g., unhealthy eating) based on contextual factors. | Used with longitudinal EMA data to predict unhealthy eating events [5]. |

| Gradient Boost / Random Forest | Robustly predicts continuous outcomes (e.g., food serving size) and handles complex variable interactions. | Used to predict food group consumption with low MAE [18]. |

| Clustering Algorithms (e.g., Hierarchical) | Identifies distinct subgroups or phenotypes within a population without pre-defined labels. | Used to cluster participants into 6 robust groups based on eating behavior [5]. |

| Software & Frameworks | ||

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Interprets ML model predictions by quantifying the contribution of each input feature. | Used to identify the most influential contextual factors predicting food consumption [18]. |

This document provides detailed protocols for applying machine learning (ML) algorithms to classify key behavioral targets in eating behavior research: unhealthy eating events, overall diet quality, and clinical eating disorders. The convergence of ubiquitous sensing technologies, advanced analytics, and multimodal data integration is enabling a new paradigm of precision nutrition and preventative health [1] [13]. These methodologies allow researchers to move beyond traditional, subjective self-reports to objective, data-driven classifications that account for significant individual variability in the psychological and contextual mechanisms driving eating behaviors [1].

Table 1: Core Behavioral Targets and Machine Learning Applications in Eating Behavior Research

| Behavioral Target | Primary Data Modalities | Common ML Approaches | Key Performance Metrics | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unhealthy Eating Events & Diet Quality | Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), Smartphone food diaries, Contextual factors (location, time, social) [3] | Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (e.g., XGBoost), Random Forests, Hurdle Models [3] | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) e.g., 0.3 servings for vegetables, 11.86 DGI points for daily diet quality [3] | Personalized nutrition interventions, real-time behavioral feedback, public health monitoring |

| Eating Disorder Classification | Self-report questionnaires, Clinical assessments, Social media text (Reddit) [19] [20] | Regularized Logistic Regression, Random Forest, CNN, BiLSTM, XGBoost [19] [20] | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) e.g., 0.92 for Anorexia Nervosa, 0.91 for Bulimia Nervosa [19] | Early screening and detection, digital phenotyping, comorbidity analysis, risk prediction |

| Obesity Level Estimation | Demographic & eating habit surveys (e.g., FAVC, FCVC, NCP) [6] | Classification (Multi-class), Clustering [6] | Classification Accuracy, Cluster Purity [6] | Population health studies, risk factor identification, subgroup discovery |

| Temporal Eating Patterns | Time-stamped eating records, Nutrient data [21] | K-Medoids clustering with Modified Dynamic Time Warping (MDTW) [21] | Silhouette Score, Elbow Method [21] | Behavioral phenotyping (e.g., "Skippers," "Night Eaters"), chrono-nutrition research |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Predicting Food Consumption and Diet Quality using Contextual Factors

Objective: To build a predictive model for food group consumption at eating occasions (EOs) and overall daily diet quality using person-level and EO-level contextual factors [3].

Materials:

- Participants: Free-living young adults (e.g., n=675, aged 18-30) [3].

- Data Collection Tool: Smartphone food diary application (e.g., "FoodNow" app) for Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) [3].

- Assessment Duration: 3-4 non-consecutive days, including one weekend day [3].

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment and Onboarding: Recruit participants meeting inclusion criteria. Obtain informed consent and provide training on using the food diary app.

- Data Collection:

- Dietary Data: Participants record all foods and beverages consumed at each EO in near-real time, providing images and text descriptions. Trained nutritionists subsequently code entries to a national nutrient database (e.g., AUSNUT 2011-2013) to calculate servings of core food groups (vegetables, fruits, grains, etc.) and discretionary foods [3].

- Contextual Data (EO-level): For each EO, the app records:

- Time and type of EO (e.g., breakfast, snack)

- Location (e.g., home, work)

- Social context (e.g., alone, with friends)

- Activity during consumption (e.g., watching TV, working)

- Food source (e.g., cooked at home, restaurant) [3].

- Contextual Data (Person-level): Via an online survey, collect:

- Demographic information (age, gender)

- Socioeconomic status

- Psychosocial factors (cooking confidence, eating self-efficacy, perceived time scarcity) [3].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Model Training and Evaluation:

- Models: Employ tree-based ensemble algorithms like Gradient Boosted Decision Trees and Random Forests [3].

- Task: For each food group, use a hurdle model approach to first predict consumption (yes/no) and then the quantity (servings) [3].

- Evaluation: Use Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to evaluate model performance on a held-out test set. Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values to interpret the impact of each contextual factor on the predictions [3].

Diagram 1: Workflow for predicting diet quality from contextual factors.

Protocol: Detection and Classification of Eating Disorders from Multi-Domain Data

Objective: To develop a diagnostic classification model for eating disorders (EDs) like Anorexia Nervosa (AN) and Bulimia Nervosa (BN) by integrating a wide range of psychosocial data domains [19].

Materials:

- Participants: Case-control sample, including clinically diagnosed individuals (e.g., with AN, BN) and matched healthy controls (HC) [19].

- Data Domains: Comprehensive assessments covering:

- Psychopathology: Symptoms of depression, anxiety, ADHD [19].

- Personality Traits: Neuroticism, hopelessness [19].

- Cognition: Performance on cognitive tasks.

- Environment: History of childhood trauma or adverse events [19].

- Substance Use: Alcohol and drug use patterns.

- Demographics: Age, gender, BMI [19].

Procedure:

- Participant Assessment: Administer a standardized battery of questionnaires and clinical interviews to both clinical and control groups to collect data across all target domains [19].

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing data, standardize continuous variables, and encode categorical variables. For longitudinal risk prediction, define "developers" (those who develop symptoms at follow-up) and "controls" (those who remain asymptomatic) [19].

- Model Training and Evaluation:

- Model: Use regularized logistic regression (e.g., L1 or L2 penalty) to prevent overfitting and perform feature selection [19].

- Task: Train a binary classifier to distinguish between each clinical group (AN, BN) and HC.

- Evaluation: Evaluate model performance using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) on a held-out test set. Perform cross-validation to ensure robustness [19].

- Model Interpretation: Analyze the coefficients of the trained model to identify the most important features (e.g., neuroticism, hopelessness, ADHD symptoms) contributing to the classification of EDs [19].

Protocol: Clustering Temporal Dietary Patterns using Modified Dynamic Time Warping

Objective: To identify distinct subgroups of individuals based on the timing and nutritional content of their eating events using an unsupervised clustering approach [21].

Materials:

- Data: Time-stamped records of eating occasions, including time of day and nutrient vector (e.g., calories, macronutrients) for each individual [21].

Procedure:

- Data Representation: Represent each individual's diet as a sequence of eating events. For each event

i, store a tuple(t_i, v_i), wheret_iis the time of day andv_iis a vector of normalized nutrient values [21]. - Distance Calculation: Use Modified Dynamic Time Warping (MDTW) to compute the distance between two individuals' dietary sequences.

- The MDTW distance between two events

(t_i, v_i)and(t_j, v_j)is defined as:d_eo(i,j) = (v_i - v_j)^T * W * (v_i - v_j) + 2 * beta * (v_i^T * W * v_j) * (|t_i - t_j| / delta)^alpha - Where

Wis a weight matrix for nutrients,betais a weighting factor,deltais a time scaling factor, andalphais an exponent [21].

- The MDTW distance between two events

- Clustering: Apply a clustering algorithm like K-Medoids to the pairwise MDTW distance matrix to group individuals with similar temporal dietary patterns [21].

- Cluster Evaluation and Interpretation: Use the silhouette score and elbow method to determine the optimal number of clusters. Interpret the resulting clusters by examining the characteristic meal timing and nutrient profiles of the medoid (central example) for each group, labeling them accordingly (e.g., "Skippers," "Night Eaters," "Grazers") [21].

Diagram 2: Clustering of temporal eating patterns with MDTW.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Tools and Technologies for ML-Based Eating Behavior Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technology | Function & Application | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition (Objective Monitoring) | Wearable Motion Sensors, Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) [13] | Passive detection of eating gestures (bite, chew) in free-living conditions. | Commercially available (e.g., research-grade wearables) |

| Data Acquisition (Dietary Reporting) | Smartphone Food Diary Apps with EMA (e.g., "FoodNow") [3] | Collect real-time data on food intake, portion sizes, and immediate context, minimizing recall bias. | Custom development or research platforms |

| Data Acquisition (Biomarkers) | Blood-based Metabolic Panels (Lipid metabolism, Liver function) [22] | Provide objective biochemical correlates of dietary patterns (e.g., pro-Mediterranean vs. pro-Western). | Clinical laboratories |

| Computational Algorithms | Modified Dynamic Time Warping (MDTW) [21] | Calculate similarity between temporal dietary sequences for clustering analyses. | Custom implementation (e.g., in Python) |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, XGBoost, PyTorch/TensorFlow [3] [20] | Provide implementations of classification, regression, and deep learning models for model building. | Open-source |

| Model Interpretation Frameworks | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [3] | Explain the output of ML models by quantifying the contribution of each input feature. | Open-source (Python) |

| Curated Datasets | UCI Obesity Levels Dataset [6] | Provides labeled data on eating habits and physical condition for training classification and clustering models. | Publicly available (UCI Repository) |

Methodologies in Practice: Algorithms, Data Sources, and Real-World Applications

The application of machine learning (ML) to classify eating behavior represents a critical advancement in nutritional science, preventive medicine, and health-focused drug development. These algorithms can decode complex patterns from multidimensional data sources—including video recordings, food images, and ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data—to objectively quantify behaviors that influence energy intake, obesity risk, and metabolic health [23] [7] [5]. The transition from traditional statistical methods to ML frameworks enables researchers to model non-linear relationships and handle the high-dimensional, time-series data characteristic of human eating behavior, paving the way for personalized interventions and more precise clinical endpoints in pharmaceutical trials [24] [7].

This application note provides a structured overview of three foundational ML algorithm families—tree-based methods, support vector machines (SVMs), and neural networks—detailing their theoretical underpinnings, implementation protocols, and performance benchmarks within eating behavior research.

The table below synthesizes quantitative performance data for various ML algorithms applied to key tasks in eating behavior classification, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Machine Learning Algorithms in Eating Behavior Applications

| Algorithm | Application Task | Key Metrics | Dataset/Subjects | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Predicting Enteral Nutrition Feeding Intolerance (ENFI) in ICU patients | AUC: 0.951, Accuracy: 96.1%, Precision: 97.7%, Recall: 91.4%, F1: 0.945 | 487 ICU patients [25] | |

| Random Forest (RF) | Predicting Enteral Nutrition-Associated Diarrhea (ENAD) | AUC: 0.777 (0.702-0.830) | 756 ICU patients [26] | |

| CatBoost | Obesity level prediction from physical activity and diet | High overall performance; Superior Accuracy, Precision, F1, AUC | 498 participants [7] | |

| Decision Tree | Unhealthy eating event prediction in e-coaching | Rule-based prediction for semi-tailored user feedback | Data from "Think Slim" mobile app [5] | |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Chewing detection from video analysis | Accuracy: 93% (after cross-validation) | 37 videos [23] | |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | African food image classification | Evaluated via F1-score, Accuracy, Recall, Precision | 1,658 images across 6 food classes [27] | |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | ENFI risk prediction | AUC: 0.931, Accuracy: 94.3%, Precision: 95.4%, Recall: 88.6%, F1: 0.919 | 487 ICU patients [25] | |

| Customized CNN (MResNet-50) | Food image classification on Food-101 dataset | Accuracy: Increased by 2.4% over existing models | Food-101 and UECFOOD256 datasets [28] | |

| Facial Landmarks (Computer Vision) | Automatic bite count from video | Accuracy: 90% | Video recordings of eating episodes [23] | |

| Deep Neural Network | Bite and gesture intake detection | Accuracy: Bites 91%, Gestures 86% | Video recordings of eating episodes [23] |

Tree-Based Methods

Theoretical Foundations and Application Rationale

Tree-based methods, including Decision Trees, Random Forests, and gradient-boosting variants like CatBoost and Histogram-based Gradient Boosting, are highly effective for eating behavior classification due to their innate capacity to handle mixed data types, capture non-linear relationships, and provide interpretable models [7] [5]. Their decision pathways can model the complex, interacting factors that influence eating behavior, such as emotional state, context, and physiological cues [5]. A significant advantage in clinical and research settings is their compatibility with Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks like SHAP and LIME, which help elucidate the contribution of specific features—such as age, weight, and dietary patterns—to the model's prediction, thereby building trust and providing actionable insights [7].

Experimental Protocol: Predicting Obesity Levels with XAI

The following protocol is adapted from a study that successfully predicted obesity levels using physical activity and dietary patterns [7].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Tree-Based Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Health & Dietary Habit Dataset | Structured dataset containing demographic, physical activity, and food frequency data. | Serves as the raw input for model training and testing. |

| Scikit-learn Library | Python ML library containing implementations of tree-based models and other algorithms. | Used for model construction, hyperparameter tuning, and evaluation. |

| CatBoost Classifier | A gradient-boosting algorithm effective with categorical data. | The primary classifier model in this protocol. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic XAI method for explaining model output. | Provides global and local feature importance for model interpretation. |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | An XAI method that creates local, interpretable approximations of the model. | Offers complementary local explanations to SHAP. |

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Collection:

- Collect data from 498 participants using an online survey capturing anonymized data on age, weight, height, physical activity, and detailed dietary habits [7].

- Ensure ethical approval is obtained from the relevant institutional review board.

Feature Engineering and Preprocessing:

- Clean the data by handling missing values and removing identifiers to protect participant anonymity.

- Encode categorical variables appropriately. Tree-based models like CatBoost can natively handle categorical features, but others may require one-hot encoding.

- Normalize or standardize numerical features if using models sensitive to feature scaling (note: tree-based models are generally robust to this).

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Split the dataset into training and test sets (e.g., 70/30 or 80/20). A repeated holdout validation is recommended for robustness [7].

- Select multiple tree-based algorithms for comparison (e.g., CatBoost, Decision Tree, Histogram-based Gradient Boosting, Random Forest, Extra Trees Classifier).

- For each model, perform hyperparameter tuning using a random search methodology with cross-validation on the training set. Key parameters to tune include:

max_depth: The maximum depth of the trees.n_estimators: The number of trees in the forest or boosting rounds.learning_rate(for boosting algorithms): The step size shrinkage.

Model Evaluation:

- Evaluate the performance of each tuned model on the held-out test set.

- Compare models using a suite of metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC).

- The CatBoost model has been shown to exhibit superior performance in this specific task [7].

Model Interpretation with XAI:

- Apply SHAP to the best-performing model (e.g., CatBoost) to generate global feature importance, identifying which variables (e.g., age, weight, specific foods) most strongly influence obesity level prediction across the entire dataset.

- Use LIME to create local explanations for individual predictions, helping to understand the model's reasoning for a single participant.

- Compare the fidelity, sparsity, and consistency of explanations from both SHAP and LIME.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

Theoretical Foundations and Application Rationale

Support Vector Machines are powerful discriminative classifiers that find the optimal hyperplane to separate data points of different classes in a high-dimensional feature space [27]. Their strength lies in their effectiveness in high-dimensional spaces and their versatility through the use of different kernel functions (e.g., linear, polynomial, radial basis function - RBF) to solve non-linear classification problems. In eating behavior research, SVMs are successfully applied to tasks like classifying food images and detecting specific eating behaviors from video data, such as chewing [23] [27]. They can achieve robust performance even with limited training data, making them suitable for pilot studies or applications where large datasets are not yet available [25].

Experimental Protocol: Video-Based Chewing Detection

This protocol outlines the use of SVM for classifying chewing events from video footage, a core eating behavior metric [23].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for SVM-based Chewing Detection

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Video Recording Setup | Standardized camera (e.g., Logitech C920) to record eating episodes. | Captures raw behavioral data for analysis. |

| Active Appearance Model (AAM) | A model for tracking facial features and deformations. | Extracts temporal model parameter values from video frames. |

| Spectral Analysis Tools | Algorithms for analyzing frequency components of a signal. | Used to analyze the temporal parameter window from the AAM for rhythmic chewing patterns. |

| Scikit-learn SVM Module | Python library providing optimized SVM implementations. | Used to train the final binary classifier on extracted spectral features. |

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Video Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Record participants in a controlled laboratory setting using a fixed camera (e.g., at 24-30 fps with a resolution of 640x480 or higher). Ensure consistent lighting and a frontal view of the participant's face [23].

- Manually annotate a subset of videos to establish a ground truth for chewing events, using software like Noldus Observer XT.

Facial Feature Tracking with Active Appearance Model (AAM):

- Apply an AAM to each video frame to track the participant's face. The AAM will generate a set of model parameters that describe the shape and appearance of the face in each frame.

- Extract the temporal sequence of these model parameter values over a sliding window of frames.

Feature Extraction via Spectral Analysis:

- Perform spectral analysis (e.g., using a Fast Fourier Transform - FFT) on the temporal window of AAM parameter values.

- This analysis transforms the facial movement data from the time domain to the frequency domain, identifying rhythmic patterns characteristic of chewing.

- Construct a feature vector for each time window using dominant frequencies and their amplitudes from the spectral analysis.

SVM Model Training and Validation:

- Train a binary Support Vector Machine classifier (e.g., using a linear or RBF kernel) using the extracted spectral feature vectors. The classifier's task is to label each time window as "chewing" or "not chewing."

- Use cross-validation on the training set to optimize the SVM's hyperparameters, primarily the regularization parameter

Cand the kernel coefficientgamma. - Validate the final model's performance against the manually annotated ground truth. The reported accuracy for this method can be as high as 93% after cross-validation [23].

Neural Networks

Theoretical Foundations and Application Rationale

Neural Networks, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), represent the state-of-the-art for complex pattern recognition tasks, such as image and sequence analysis. In eating behavior research, their primary application is in automated food recognition from images, which is a foundational step for dietary assessment [28] [29] [27]. CNNs automatically learn hierarchical features from raw pixel data, overcoming the limitations of handcrafted features and achieving high accuracy even with challenges like intra-class variability (e.g., the same dish looking different) and inter-class similarity (e.g., different dishes looking alike) [28]. Advanced architectures like ResNet50 and customized lightweight networks such as MResNet-50 and LNAS-NET have demonstrated superior performance in food classification benchmarks [27] [28] [29].

Experimental Protocol: Food Image Classification and Recipe Extraction

This protocol details a comprehensive framework for classifying food images and automatically extracting recipe information, combining a customized CNN with Natural Language Processing (NLP) [28].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Neural Network-based Food Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Food Image Datasets | Curated datasets like Food-101, UECFOOD256, or custom collections. | Used for training and evaluating the CNN model. |

| Pre-trained CNN Model (ResNet50) | A deep CNN model pre-trained on ImageNet, serving as a feature extractor. | The backbone for transfer learning and feature extraction. |

| Customized MResNet-50 | A lightweight, modified ResNet-50 architecture proposed for food classification. | The core classifier to be trained and evaluated. |

| NLP Algorithms (Word2Vec, Transformers) | Algorithms for processing and understanding textual data. | Used for automated ingredient identification from recipe text. |

| Domain Ontology | A semi-structured knowledge representation of cuisine, food items, and ingredients. | Stores relationships to enable recipe extraction and knowledge retrieval. |

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Augmentation:

- Obtain a labeled food image dataset (e.g., Food-101, UECFOOD256, or a domain-specific dataset like African foods).

- Preprocess images by resizing to a uniform dimension (e.g., 224x224 pixels) and normalizing pixel values.

- Apply extensive data augmentation techniques (e.g., random rotation, flipping, cropping, brightness/contrast adjustments) to increase the effective size of the training set and improve model robustness.

CNN Model Construction and Training:

- Model Choice: Implement a customized CNN like MResNet-50, which is designed to be lightweight and accurate for food images [28]. Alternatively, use a standard pre-trained model like ResNet50 as a starting point for transfer learning [27].

- Transfer Learning: Load pre-trained weights (e.g., from ImageNet). Replace the final fully-connected layer with a new one containing nodes equal to the number of food classes in your dataset.

- Training: Fine-tune the model on the food dataset. Initially, freeze the earlier layers and only train the new head. Subsequently, unfreeze deeper layers for full fine-tuning. Use an optimizer like Adam or SGD with a reduced learning rate.

Model Evaluation:

- Evaluate the trained model on a held-out test set.

- Report standard metrics such as Top-1 and Top-5 Accuracy. The proposed MResNet-50 has been shown to increase accuracy on the Food-101 dataset by 2.4% and on UECFOOD256 by 7.5% over existing models [28].

Automated Recipe Extraction (NLP Pipeline):

- For recipe data associated with food images, deploy an NLP pipeline.

- Use Word2Vec to create vector representations of ingredient words, capturing semantic relationships.

- Employ Transformer-based models for more advanced tasks like named entity recognition to identify and extract ingredient names from unstructured recipe text.

- Build a domain ontology to structurally represent the relationships between a cuisine, its food items, and their constituent ingredients, enabling efficient storage and retrieval of recipe information.

The study of eating behavior is critical for addressing global health challenges such as obesity and eating disorders. Traditional research methods, which rely heavily on self-reporting through food diaries and recalls, are often limited by recall bias, subjectivity, and participant burden [30]. Machine learning (ML) now enables a transformative approach by integrating diverse data streams—known as multimodal data—to build comprehensive, objective models of eating behavior [31]. This paradigm involves processing and finding relationships between different types of data, or modalities, such as sensor signals, textual data, and images [32].

This Application Note provides a structured framework for employing multimodal data integration within eating behavior research. It details practical methodologies, quantitative performance benchmarks, and specific reagent solutions to equip researchers with the tools needed to implement these advanced approaches in their own work.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of Multimodal Technologies

The following tables summarize the performance of various sensing and predictive technologies used in eating behavior research, providing benchmarks for expected outcomes.

Table 1: Performance of Automated Eating Behavior Monitoring Technologies

| Technology | Primary Measured Behavior | Key Performance Metrics | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist-Worn Inertial Sensor [2] | Feeding Gesture Count | 94% accuracy in counting gestures; 75% F-measure for gesture classification | Unstructured overeating experiment |

| Smart Glasses with Optical Sensors [33] | Chewing Segments & Eating Episodes | F1-score: 0.91 (controlled), Precision: 0.95 & Recall: 0.82 (real-life) | Laboratory and real-life conditions |

| Accelerometer-based Framework [2] | Overeating Prediction | Correlation of r=.79 (p=.007) between feeding gesture count and caloric intake | Unstructured eating (watching TV) |

Table 2: Performance of Contextual Food Consumption Prediction Models [3]

| Predicted Food Group | Model Performance (Mean Absolute Error in Servings) |

|---|---|

| Vegetables | 0.30 |

| Dairy | 0.28 |

| Meat | 0.40 |

| Grains | 0.55 |

| Discretionary Foods | 0.68 |

| Fruit | 0.75 |

| Overall Diet Quality (DGI) | 11.86 points |

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Data Collection

Protocol for Wrist-Worn Sensor Data Collection on Feeding Gestures

This protocol is designed to capture inertial data during eating episodes for detecting feeding gestures and predicting overeating [2].

- Objective: To collect labeled inertial data from a wrist-worn sensor for training a model to count feeding gestures and identify overeating episodes.

- Equipment: A 6-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU—3-axis accelerometer and 3-axis gyroscope) worn on the wrist, sampling at a minimum of 31 Hz [2].

- Participant Preparation: Secure the sensor on the participant's dominant wrist. Ensure it is snug but comfortable.

- Data Collection Scenarios:

- Structured Eating: Participants consume a meal following a scripted protocol.

- Unstructured Eating: Participants are induced to overeat while watching television and consuming their favorite foods after feeling full. Video recording is used to establish ground truth for feeding gestures and eating episodes.

- Data Annotation: Synchronize video and sensor data streams. Annotate the start and end times of each feeding gesture (hand-to-mouth motion) and the total eating episode.

Protocol for Real-Life Eating Context and Consumption Data Collection

This protocol uses smartphone-based Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) to capture person-level and eating occasion-level contextual factors [3].

- Objective: To gather self-reported data on food consumption and concurrent contextual factors in near real-time in a free-living population.

- Equipment: Smartphone with a custom food diary application (e.g., FoodNow app [3]).

- Procedure:

- Participants complete a baseline online survey covering person-level factors (e.g., cooking confidence, self-efficacy, food availability).

- Over 3-4 non-consecutive days, participants use the smartphone app to log all eating occasions.

- For each eating occasion, participants report:

- All foods and beverages consumed, with quantities.

- EO-level contextual factors: time of day, location, social context, activity during consumption, and food source.

- The app sends prompts to log missed meals and provides end-of-day reminders.

- Data Processing: Trained nutritionists code all dietary entries, matching them to a national nutrient database and calculating servings for core food groups and overall diet quality (DGI) [3].

Protocol for Multimodal Social Media Sentiment Analysis

This protocol guides the collection and analysis of image-and-text social media posts to classify sentiment, which can be adapted to study eating-related content [34].

- Objective: To train and evaluate multimodal machine learning models for classifying sentiment in social media posts containing both text and images.

- Data Collection: Use platform APIs (e.g., CrowdTangle for Meta, Academic Research API for X) to collect public posts containing relevant keywords and image attachments.

- Data Annotation: Human annotators label a substantial subset of posts (e.g., 13,000) into categories such as positive sentiment, negative sentiment, hate, or anti-hate speech.

- Model Training & Evaluation:

- Unimodal Models: Train a BERT model on text and a VGG-16 model on images.

- Multimodal Models: Train and evaluate models like CLIP, VisualBERT, and an intermediate fusion model.

- Evaluation Metrics: Compare models based on accuracy and macro F1-score across the different sentiment and hate speech categories [34].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: End-to-end workflow for multimodal data integration in eating behavior research, showing the fusion of sensor, self-report, and social media data.

Diagram 2: Architectural overview of multimodal fusion strategies, from unimodal encoding to final classification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Multimodal Eating Behavior Research

| Tool / Reagent | Specifications / Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Wrist-Worn IMU Sensor [2] | 6-axis (Accelerometer & Gyroscope), min. 31 Hz sampling | Captures feeding gestures and hand-to-mouth motions for automated intake monitoring. |

| Smart Glasses with Optical Sensors [33] | OCO optical sensors, inertial measurement unit (IMU) | Monitors facial muscle activations (chewing) in a non-invasive, real-life applicable form factor. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment App [3] | Smartphone-based (e.g., FoodNow app), with push notifications | Collects real-time self-reported data on food intake and contextual factors, minimizing recall bias. |

| Pre-trained Language Model [34] | BERT or RoBERTa architecture | Encodes textual data from social media or self-reports for sentiment and content analysis. |

| Pre-trained Vision Model [34] | VGG-16, ResNet, or CLIP architecture | Encodes visual data from social media images or food photos for content classification. |

| Multimodal Fusion Model [34] [32] | CLIP, VisualBERT, or Intermediate Fusion Model | Integrates encoded features from text and images to classify complex constructs like sarcasm or hate. |

| Gradient Boosted Decision Trees [3] | e.g., XGBoost algorithm | Predicts food group consumption from contextual factors; provides interpretable results via SHAP. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [3] | Model interpretation library | Interprets ML model predictions to identify the most influential contextual factors. |

The application of machine learning (ML) in eating behavior classification research has ushered in powerful predictive capabilities, but often at the cost of model interpretability. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) addresses this critical challenge by making the decision-making processes of complex "black box" models transparent and understandable to researchers, clinicians, and regulators. For research focusing on machine learning algorithms for eating behavior classification, XAI is not merely a technical enhancement but a fundamental requirement for scientific validation, clinical translation, and ethical deployment. The XAI market is projected to reach $9.77 billion in 2025, reflecting its growing importance across sectors, with healthcare and pharmaceutical applications being major drivers [35]. In eating behavior research, where interventions depend on understanding causal relationships between contextual factors and dietary outcomes, XAI techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) provide the necessary transparency to move from correlation to actionable insight.

Theoretical Foundations of SHAP and LIME

Core Concepts in Explainable AI

XAI methods can be categorized based on their scope and approach. Global interpretability explains the model's overall behavior, while local interpretability explains individual predictions [36]. Model-agnostic methods like SHAP and LIME can be applied to any ML model, making them particularly valuable in research settings where multiple algorithms are evaluated.

- Transparency vs. Interpretability: In XAI, transparency refers to understanding how a model works internally—its architecture, algorithms, and training data. Interpretability, conversely, concerns understanding why a model makes specific decisions, particularly the relationships between inputs and outputs [35].

- Fidelity measures how accurately an explanation reflects the model's actual decision process, while consistency refers to the stability of explanations across similar inputs or models [7].

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)

SHAP is grounded in cooperative game theory, specifically Shapley values, which provide a mathematically rigorous framework for assigning feature importance. It quantifies the marginal contribution of each feature to the difference between the actual prediction and the average prediction [37]. SHAP provides both global interpretability (feature importance across the entire dataset) and local interpretability (feature contributions for individual predictions) [7] [38]. Key advantages include its theoretical foundation and consistency across models, though it can be computationally intensive for large datasets [7].

LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations)

LIME operates by perturbing the input data and observing changes in predictions to build local, interpretable approximations (typically linear models) around individual instances [36]. While SHAP explains the output of the model using game theory, LIME explains the model by locally approximating it with an interpretable model [38]. Research has shown that LIME often demonstrates superior fidelity in local explanations compared to other methods, meaning it more accurately reflects the model's behavior for specific instances [7].

Figure 1: SHAP and LIME Methodological Workflows. This diagram illustrates the distinct computational approaches of SHAP (based on cooperative game theory) and LIME (based on local perturbation and approximation) for explaining black-box model predictions.

Application Protocols for Eating Behavior Research

Experimental Design and Data Collection

Implementing SHAP and LIME begins with robust experimental design tailored to eating behavior classification:

Dataset Selection: Utilize datasets containing comprehensive eating behavior annotations. Example datasets include:

- The OCPM dataset (498 participants, ages 14-61) with 17 features on eating habits and physical activity patterns [7]

- The MEALS study (675 young adults) with 3-4 non-consecutive days of food intake recording via smartphone app, including contextual factors [3]

- HFSS snacking data (111 participants) with 28 days of snacking occurrences tracked by location, time, and day [10]

Feature Engineering: Extract and preprocess features relevant to eating behavior:

- Person-level factors: Age, gender, socioeconomic status, cooking confidence, self-efficacy, food availability [3]

- Eating occasion-level factors: Time of day, location, social context, activities during consumption, meal type [3]

- Dietary patterns: Meal frequency, consumption of specific food groups (fruits, vegetables, discretionary foods), alcohol consumption [7] [37]

- Temporal patterns: Day of week, time bins, sequences of eating events [10]

Model Selection: Train multiple ML models appropriate for behavioral classification:

- Ensemble methods (CatBoost, Random Forest, XGBoost) have demonstrated strong performance in obesity prediction (up to 96.88% accuracy in stacking ensembles) [37]

- Neural networks (Feed Forward NN, LSTM) can capture temporal patterns in eating behavior data [10]

- Comparative evaluation of multiple algorithms (e.g., Bernoulli Naive Bayes, SVM, Decision Tree, Extra Trees) to identify best-performing model [7]

Implementation Protocol for SHAP

The following protocol details the systematic implementation of SHAP for eating behavior models:

Model Training and Validation

- Train selected ML model using repeated holdout validation or k-fold cross-validation

- Tune hyperparameters using appropriate search methodologies (e.g., random search)

- Evaluate model effectiveness using accuracy, precision, F1 score, and AUC metrics [7]

SHAP Explanation Generation

- Initialize appropriate SHAP explainer (e.g., TreeExplainer for tree-based models, KernelExplainer for model-agnostic applications)

- Compute SHAP values for the test set:

explainer.shap_values(X_test) - For global explanations, calculate mean absolute SHAP values across the dataset [3]

Result Interpretation and Visualization

- Generate summary plots showing global feature importance

- Create force plots for individual predictions to visualize local feature contributions

- Produce dependence plots to examine feature relationships and interactions

- For eating behavior applications, identify key predictive factors such as meal frequency, weight, age, and specific food consumption patterns [7]

Implementation Protocol for LIME

The LIME implementation protocol focuses on local interpretability:

LIME Setup and Configuration

- Initialize LIME explainer with appropriate parameters for tabular data:

lime_tabular.LimeTabularExplainer() - Specify the mode ("classification" or "regression") based on the prediction task

- Set parameters for data discretization and feature selection

- Initialize LIME explainer with appropriate parameters for tabular data:

Instance-Level Explanation Generation

- Select representative or critical instances for explanation (e.g., misclassified cases, edge cases)

- Generate local explanations:

explainer.explain_instance(data_row, model.predict_proba) - Configure the number of features to include in explanations for optimal interpretability

Explanation Analysis and Validation

- Evaluate explanation fidelity by comparing LIME's local model to the black-box model's predictions

- Assess explanation stability across similar instances

- Compare LIME explanations with SHAP results for consistency checking [7]

Comparative Analysis Framework

Establish a framework for evaluating and comparing SHAP and LIME outputs:

- Quantitative Metrics: Measure fidelity, sparsity, and consistency across explanations [7]

- Qualitative Assessment: Evaluate clinical relevance and actionability of identified features

- Integration Approach: Use SHAP for global feature importance and LIME for case-specific reasoning [37]

Case Studies and Research Applications

Obesity Level Prediction Using XAI

A 2025 study demonstrated the application of SHAP and LIME for obesity level prediction based on physical activity and dietary patterns. The research employed six ML models, with CatBoost achieving superior performance (93.67% accuracy) [7]. Key findings from the XAI analysis included:

- Global explanations from SHAP identified age, weight, height, and specific food patterns as the most significant predictors of obesity levels [7]

- LIME provided high-fidelity local explanations that helped interpret individual risk profiles

- The comparative analysis revealed that LIME showed superior fidelity for instance-level explanations, while SHAP demonstrated improved sparsity and consistency across different models [7]

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML Models in Obesity Prediction with XAI Integration

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | F1 Score | AUC | Key Predictors Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 93.67% | High | High | High | Age, weight, specific food patterns |

| Decision Tree | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Meal frequency, physical activity |

| Histogram-based GB | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Technology usage, dietary habits |

| Hybrid Stacking | 96.88% | 97.01% | 96.88% | Not specified | Sex, weight, food habits, alcohol consumption [37] |

Food Consumption Prediction at Eating Occasions

Research using the MEALS study dataset applied ML with SHAP to predict food consumption at eating occasions among young adults. The study used gradient boost decision tree and random forest algorithms with mean absolute SHAP values to interpret predictive factors [3]. Significant findings included:

- Predictive models performed robustly with MAE below half a serving for various food groups (0.3 servings for vegetables, 0.75 for fruit) [3]

- For overall daily diet quality, model predictions deviated by 11.86 DGI points from the actual score [3]

- SHAP analysis revealed that cooking confidence, self-efficacy, food availability, perceived time scarcity, and activity during consumption were the most influential factors for diet quality [3]

- The importance of predictive factors varied substantially across different food groups, demonstrating the context-dependent nature of eating behaviors [3]

HFSS Snacking Behavior Prediction

A study on predicting consumption of snacks high in saturated fats, salt, or sugar (HFSS) demonstrated how minimal contextual data could enable effective prediction. The research used random forest regressor, XGBoost, and neural networks to predict time to next HFSS snack [10]. Implementation insights included:

- Predictions achieved accuracy as low as 17 minutes on average for time to next snack [10]

- Machine learning methods outperformed baseline statistical models, though no single ML method was clearly superior [10]

- Temporal and location data (day of week, time bins, location categories) provided sufficient predictive signal despite minimal data collection burden [10]

Table 2: XAI Applications in Eating Behavior Research: Datasets and Key Findings

| Study Focus | Dataset | Best Performing Model | Key Predictors Identified via XAI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity Level Prediction | 498 participants, eating habits & physical activity [7] | CatBoost (93.67% accuracy) [7] | Age, weight, height, specific food patterns [7] |

| Food Consumption Prediction | MEALS study (675 young adults) [3] | Gradient Boost Decision Tree | Cooking confidence, self-efficacy, food availability, time scarcity [3] |

| Multiclass Obesity Prediction | Lifestyle data [37] | Hybrid Stacking (96.88% accuracy) [37] | Sex, weight, food habits, alcohol consumption [37] |

| HFSS Snacking Prediction | 111 participants, 28-day tracking [10] | Feed Forward Neural Network (marginal advantage) [10] | Temporal patterns, location data [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Computational Tools and Libraries