Mechanisms of Lipid-Soluble Vitamin Absorption: From Cellular Pathways to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of lipid-soluble vitamin (A, D, E, K) absorption mechanisms for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Mechanisms of Lipid-Soluble Vitamin Absorption: From Cellular Pathways to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of lipid-soluble vitamin (A, D, E, K) absorption mechanisms for research scientists and drug development professionals. We explore foundational physiological pathways, methodological approaches for studying absorption, troubleshooting for malabsorption conditions, and validation through clinical and comparative studies. The article examines emerging concepts including gut microbiota interactions, genetic polymorphisms affecting transport proteins, and advanced formulation strategies to overcome absorption barriers, providing a translational framework connecting basic science to therapeutic applications.

Cellular and Physiological Pathways of Lipid-Soluble Vitamin Uptake

The absorption of dietary lipids and fat-soluble vitamins is a complex, multistep process orchestrated by the gastrointestinal tract, primarily within enterocytes. This process is essential for whole-body lipid and energy homeostasis and involves intricate interactions between bile salts for solubilization, intracellular trafficking mechanisms within enterocytes, and the assembly and secretion of chylomicrons [1] [2]. Dysregulation of this machinery contributes to dyslipidemia and increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [1]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on the core components of this system—enterocytes, bile salts, and chylomicron assembly—framed within the context of lipid-soluble vitamin absorption research. It is structured to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals by summarizing quantitative data, detailing experimental protocols, and visualizing key pathways and workflows.

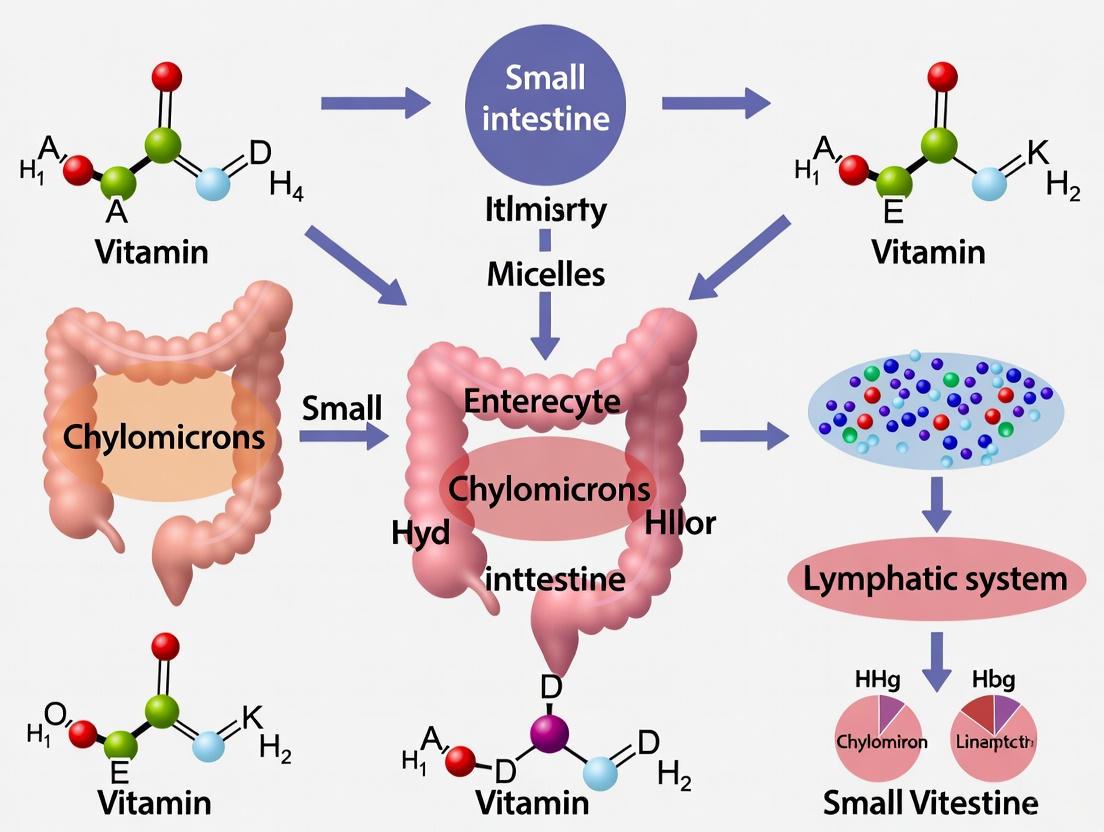

The efficient digestion and absorption of dietary lipids, including triacylglycerols (TAGs), phospholipids, sterols, and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), are critical for maintaining energy homeostasis and supporting vital physiological functions [2]. The process can be broadly divided into three phases: 1) intraluminal digestion and solubilization, which relies on lipases and bile salts; 2) cellular uptake and processing within enterocytes; and 3) packaging and export via chylomicrons into the lymphatic system and circulation [1] [2] [3].

The enterocyte serves as the central processing unit, where resynthesized lipids are assembled into chylomicrons, large TAG-rich lipoprotein particles [4]. Beyond triglycerides, this pathway is also the principal route for the absorption of lipid-soluble vitamins, which rely on their incorporation into chylomicrons for systemic delivery [3]. Understanding this machinery is paramount for developing therapeutic strategies to modulate lipid absorption and address associated metabolic disorders.

Core Machinery and Molecular Components

Enterocytes: The Central Processing Unit

Enterocytes, the predominant epithelial cells lining the small intestine, are equipped with specialized structures and molecular machinery to handle lipid absorption [5].

- Cellular Specialization: The apical membrane of enterocytes is composed of a brush border of microvilli, dramatically increasing the surface area available for nutrient uptake [5].

- Key Absorptive Functions:

Bile Salts: Essential Solubilizing Agents

Bile salts, synthesized in the liver and secreted into the duodenum, are critical for the efficient absorption of lipids and fat-soluble vitamins.

- Emulsification and Micelle Formation: Bile salts act as biological detergents, emulsifying dietary fat into fine lipid droplets and forming mixed micelles with the products of lipid hydrolysis (e.g., fatty acids, monoacylglycerols) and fat-soluble vitamins [2]. This process is indispensable for presenting hydrophobic molecules to the enterocyte's brush border membrane.

- Clinical Evidence: The critical nature of bile is highlighted by significantly decreased lipid absorption rates in individuals with bile fistulas, where the duodenal concentration of bile acids is greatly reduced [2].

The Chylomicron Assembly Line within Enterocytes

The assembly and secretion of chylomicrons (CMs) is a multistep process within enterocytes, requiring precise coordination of apolipoproteins, enzymes, and transport proteins.

Table 1: Key Molecular Components in Chylomicron Assembly

| Component | Type/Classification | Primary Function in Chylomicron Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein B-48 (apoB48) | Structural Protein | A truncated form of apoB100; essential structural component of the chylomicron particle; lipidates during translation to form a primordial lipoprotein [3]. |

| Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein (MTP) | Lipid Transfer Protein | Transfers lipids to nascent apoB48 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen; critical for proper folding of apoB48 and formation of pre-chylomicron particles [1] [3]. |

| CD36/FAT | Fatty Acid Transporter | Facilitates uptake of fatty acids; plays a regulatory role in CM formation by inducing key proteins like MTP and FABP; involved in post-assembly transport [1] [2]. |

| Fatty Acid Binding Protein (FABP) | Intracellular Carrier | Binds fatty acids and monoacylglycerols intracellularly; facilitates their trafficking to the ER for re-esterification; FABP1 also initiates the budding of pre-chylomicron transport vesicles (PCTVs) from the ER [1] [2]. |

| Monoacylglycerol Acyltransferase (MGAT) & Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT) | Enzymes | Catalyze the resynthesis of triglycerides from absorbed fatty acids and monoacylglycerols via the monoacylglycerol pathway, which accounts for ~80% of intestinal TAG synthesis [2]. |

| SNARE Complex (e.g., VAMP7, Syntaxin-5) | Vesicle Docking/Fusion Machinery | Mediates the fusion of Pre-Chylomicron Transport Vesicles (PCTVs) with the Golgi apparatus, enabling the maturation of chylomicrons [1]. |

- Uptake and Resynthesis: Products of lipid digestion (fatty acids, 2-monoacylglycerols) are taken up by enterocytes via passive diffusion and protein-mediated transport (e.g., CD36) [2]. Inside the cell, they are bound to FABPs and transported to the ER. Within the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER), TAGs are resynthesized predominantly via the MGAT and DGAT pathway [4].

- Primordial Particle Formation: In the ER membrane, nascent apoB48 is lipidated by MTP, forming a dense, primordial lipoprotein particle. This step prevents the intracellular degradation of apoB48 [3].

- Core Expansion and Pre-CM Formation: The primordial particle is expanded into a triglyceride-rich pre-chylomicron through the addition of a large bolus of lipid, potentially from lumenal lipid droplets or via direct transfer [3].

- Vesicular Transport to Golgi: Pre-chylomicrons are packaged into specialized Pre-Chylomicron Transport Vesicles (PCTVs). The budding of PCTVs from the ER is facilitated by FABP1 and CD36, and the vesicles are directed to the Golgi by the vesicle-SNARE protein VAMP7 [1].

- Golgi Maturation and Secretion: At the Golgi, PCTVs fuse via the SNARE complex (VAMP7, Syntaxin-5), releasing the pre-CM into the Golgi lumen for final maturation (e.g., glycosylation of apoB48, addition of apoAIV) [1]. Mature CMs are then transported in secretory vesicles to the basolateral membrane, exocytosed into the lamina propria, and subsequently enter the lymphatic lacteals for systemic distribution [1].

The diagram below illustrates the sequential stages of chylomicron assembly within an enterocyte.

Quantitative Data in Lipid-Soluble Vitamin Absorption

Understanding the absorption of lipid-soluble vitamins (FSVs) is a key application of the core gastrointestinal machinery. The following table summarizes quantitative and mechanistic data related to their absorption.

Table 2: Quantitative and Mechanistic Data on Fat-Soluble Vitamin Absorption

| Vitamin | Key Absorption Characteristics | Associated Transport Proteins/Pathways | Molecular Interaction with Membrane (from MD Simulations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (Retinol) | Absorbed via chylomicron pathway; its ester, retinyl ester, is packaged into CMs [3]. | Retinol-binding protein; Chylomicron pathway dependent on MTP [3]. | Hydroxyl group at the tail; highest structural flexibility and diffusion coefficient; plugs head group into hydrocarbon core of lipid bilayer [6]. |

| Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol) | Major pathway: secretion with chylomicrons. A secondary pathway involves secretion with HDLs, important when chylomicron assembly is defective [7]. | MTP-dependent for chylomicron pathway; HDL pathway is MTP-independent [7]. | Hydroxyl at the head group; moves through one leaflet and stabilizes in the opposite leaflet; forms hydrogen bonds with phosphate group of DPPC [6]. |

| Vitamin K (Phylloquinone) | Absorbed similarly to other dietary lipids [6]. | Intestinal scavenger receptors; Chylomicron pathway [6]. | No hydroxyl group; stabilizes near phosphate group without H-bonding; precise tilting angle of 120°; low diffusion coefficient suggests high retention in gel-phase membranes [6]. |

| Vitamin D | Absorbed in the duodenum [5]. | Chylomicron pathway [5]. | Information not specified in search results. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Absorption Pathways

To study the complex process of lipid and vitamin absorption, researchers employ a range of in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo models. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol: Investigating Vitamin E Transport Pathways Using Primary Enterocytes

This protocol is adapted from the work published in the Journal of Lipid Research and is used to delineate the dual pathways of vitamin E absorption [7].

Objective: To characterize the mechanisms of α-tocopherol uptake and secretion in primary enterocytes and identify the contribution of chylomicron vs. HDL pathways.

Materials:

- Primary Enterocytes: Isolated from rat or mouse small intestine.

- Radioactive Tracer: [³H]α-tocopherol.

- Lipid Supplements: Oleic acid complexed with bovine serum albumin (BSA), lipid mixtures (e.g., taurocholate, monoolein, fatty acids).

- MTP Inhibitor: e.g., CP-346086 or BMS-197636.

- Cell Culture Medium: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) or equivalent, supplemented with fatty acid-free BSA.

- Ultracentrifugation Equipment: For separation of lipoprotein density classes.

- Scintillation Counter: For quantifying radioactivity.

Methodology:

- Cell Isolation and Culture: Isolate primary enterocytes from the small intestine of rats or mice. Culture the cells in an appropriate medium.

- Uptake Phase: Incubate enterocytes with [³H]α-tocopherol for up to 1 hour to allow for cellular uptake. The medium can be varied:

- Group A (No Lipid): Medium alone.

- Group B (With Lipid): Medium supplemented with lipids and oleic acid to stimulate chylomicron assembly.

- Secretion Phase: After uptake, wash the cells to remove extracellular tracer. Incubate the cells with fresh medium to allow for secretion of the incorporated vitamin E.

- To test the role of MTP, include a treatment group where a specific MTP inhibitor is added during the secretion phase.

- To test the HDL pathway, include a group where exogenous HDL is added to the secretion medium.

- Lipoprotein Separation and Analysis: Collect the secretion medium. Separate different lipoprotein classes (chylomicrons/VLDL, IDL/LDL, HDL) via sequential ultracentrifugation at their characteristic densities.

- Quantification: Measure the radioactivity of [³H]α-tocopherol in each lipoprotein fraction and within the cells using a scintillation counter.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the proportion of secreted vitamin E associated with each lipoprotein pathway. Compare secretion profiles under different conditions (with/without lipids, with/without MTP inhibition, with/without HDL).

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations of Vitamin Absorption into Lipid Bilayers

This computational protocol is based on studies that investigate the molecular interactions of fat-soluble vitamins with membranes [6].

Objective: To determine the distribution, orientation, and dynamics of retinol, α-tocopherol, and phylloquinone within a model phospholipid bilayer.

Materials:

- Simulation Software: GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, or similar MD simulation package.

- Force Field Parameters: CHARMM36, AMBER Lipid21, or other compatible force fields for lipids and small molecules.

- Molecular Structures:

- Membrane: A pre-equilibrated bilayer of 128 Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) molecules.

- Ligands: 3D coordinate files for retinol, α-tocopherol, and phylloquinone.

- Solvent Model: Explicit water model, e.g., SPC (Simple Point Charge) or TIP3P.

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster.

Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Obtain the initial structure of the DPPC bilayer.

- Place one vitamin molecule in the aqueous phase, approximately 41 Å from the bilayer center along the z-axis.

- Solvate the entire system (bilayer + vitamin) in a box of explicit water molecules.

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiological salt concentration.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization (e.g., using steepest descent algorithm) to remove any steric clashes and relax the system.

- Equilibration:

- Conduct a short simulation (e.g., 100-200 ps) in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) to stabilize the temperature.

- Follow with a longer simulation (e.g., 1 ns) in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to stabilize the pressure and density of the system.

- Production Run: Perform a long, unbiased MD simulation (e.g., 100 ns or more) under NPT conditions. Trajectories are saved at regular intervals for analysis.

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Distribution and Localization: Calculate the density profile of the vitamin along the bilayer axis (z-axis) to identify its favorable binding site.

- Orientation: Analyze the tilt angle of the vitamin molecule relative to the lipid bilayer.

- Interactions: Identify hydrogen bonds and other non-covalent interactions between the vitamin and lipid headgroups (e.g., phosphate groups).

- Dynamics: Calculate the mean-squared displacement (MSD) to determine the diffusion coefficient of the vitamin within the membrane.

The workflow for this computational approach is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

This section details key reagents, models, and tools essential for experimental research in the field of intestinal lipid and fat-soluble vitamin absorption.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipid Absorption Studies

| Reagent / Model | Category | Specific Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In Vitro Model | Differentiated human colon adenocarcinoma cells; model human intestinal epithelium for studying uptake, intracellular trafficking, and polarized secretion of lipids and vitamins [6] [7]. |

| Primary Enterocytes | Ex Vivo Model | Enterocytes freshly isolated from rodent intestine; provide a more physiologically relevant model than cell lines, retaining native expression of transporters and metabolic enzymes [7]. |

| MTP Inhibitors | Pharmacological Tool | Compounds like CP-346086; used to inhibit MTP activity, thereby blocking the assembly and secretion of apoB-containing lipoproteins (chylomicrons) to study their necessity for lipid/vitamin absorption [7] [3]. |

| CD36/FAT Knockout Mice | Genetic Model | Mice with targeted deletion of the Cd36 gene; used to study the role of this fatty acid transporter in lipid sensing, CM formation, and post-assembly transport [1] [2]. |

| SNARE Complex Inhibitors | Molecular Tool | Proteins or peptides that disrupt SNARE complex formation (e.g., targeting Syntaxin-Binding Protein 5); used to probe the mechanisms of PCTV fusion with the Golgi apparatus [1]. |

| Radiolabeled Tracers | Tracking Reagent | e.g., [³H]α-tocopherol, [¹⁴C]triolein; used to quantitatively track the uptake, intracellular fate, and secretion of specific lipids and vitamins in experimental models [7]. |

| Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine | Model Membrane | A synthetic phospholipid used to form well-defined lipid bilayers for biophysical studies, such as Molecular Dynamics simulations, to investigate vitamin-membrane interactions [6]. |

The gastrointestinal absorption machinery, centered on enterocytes, bile salts, and chylomicron assembly, represents a highly efficient and regulated system for the assimilation of dietary lipids and fat-soluble vitamins. The process, from luminal solubilization to basolateral secretion, involves a cascade of coordinated events mediated by specific proteins, enzymes, and vesicular transport systems. Ongoing research continues to elucidate critical regulatory nodes, including post-assembly mechanisms and the role of intestinal lymphatics [1]. A deep understanding of this machinery not only advances fundamental biological knowledge but also provides a foundation for developing novel therapeutic interventions targeting dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and disorders of fat-soluble vitamin absorption.

The absorption of lipophilic compounds, including drugs and essential micronutrients, is a complex process governed by their solubility in the gastrointestinal environment and their subsequent incorporation into absorbable mixed micelles. This whitepaper delineates the critical roles that dietary lipids and bile acid secretion play in modulating the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of lipid-soluble vitamins and poorly water-soluble drugs. The dissolution and solubilization of these compounds are contingent upon the presence of dietary fat, which stimulates biliary secretion, and the physicochemical properties of the lipids themselves. Through an examination of recent in vitro, in silico, and in vivo studies, this guide provides a mechanistic overview of the absorption pathways, summarizes quantitative findings on factors influencing bioavailability, and presents standardized experimental protocols for preclinical assessment. The insights herein are intended to inform researchers and drug development professionals in the design of more effective lipid-based formulations and nutritional interventions.

The oral bioavailability of lipid-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class II/IV drugs is intrinsically limited by their poor aqueous solubility. Their absorption is not a passive process but is an active cascade mediated by the co-consumption of dietary lipids and the subsequent secretion of bile acids [8] [9]. This process can be conceptualized in two primary stages: first, the solubilization of the compound within the lipid phase of the digesta, and second, its enzymatic lipolysis and incorporation into mixed micelles composed of bile acids and phospholipids, which enable transport to the enterocyte surface [10] [11].

The gastrointestinal tract represents a dynamic physiological environment where the food matrix, lipid composition (solid vs. liquid), and the bile acid pool interact to determine the ultimate bioavailability of a lipophilic substance. Emerging research underscores that this process is further modulated by the gut microbiome, which enzymatically alters the bile acid landscape, and by dietary components such as soluble fibers, which can profoundly impact micelle formation and stability [9] [11]. This guide synthesizes current research on these mechanisms, providing a technical foundation for leveraging these principles in scientific and industrial applications.

Core Mechanisms: Lipids, Bile, and the Aqueous Boundary Layer

The Lipid Catalyst: Dietary Fat as a Solubilization Vehicle

Dietary lipids serve as the initial hydrophobic solvent for lipophilic compounds within the gut. The type of lipid—categorized by its physical state (solid vs. liquid) and fatty acid chain length—plays a determinative role in the efficiency of this process.

- Liquid vs. Solid Lipids: Liquid lipids, such as triolein (TO), are generally more effective at enhancing bioavailability compared to solid lipids like tristearin (TS). This is attributed to the more complete and rapid lipolysis of liquid lipids, which readily releases fatty acids and monoglycerides that integrate into mixed micelles. Solid lipids, in contrast, may undergo only partial lipolysis and can act as inert carriers, neither significantly aiding nor impeding the dissolution and absorption of associated drugs like griseofulvin [8] [10].

- Stimulation of Biliary and Pancreatic Secretions: The presence of fat in the duodenum is a potent physiological trigger for the release of bile from the gallbladder and pancreatic enzymes. This is a critical step, as bile acids are indispensable for the formation of mixed micelles [11].

Bile Acids: The Gateway to Absorption

Bile acids are biological surfactants synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and conjugated to glycine or taurine. Their primary function in absorption is the solubilization of lipolytic products (e.g., fatty acids, monoglycerides) and lipophilic compounds into mixed micelles.

- Enterohepatic Circulation: Bile acids undergo efficient enterohepatic circulation, a process where they are recycled from the ileum back to the liver, ensuring a constant pool is available for lipid absorption [11]. This circulation is modulated by the gut microbiome via enzymes like bile salt hydrolase (BSH), which deconjugates primary bile acids, influencing their solubility, function, and reabsorption kinetics [11].

- Mixed Micelle Formation: Mixed micelles are molecular aggregates that ferry lipophilic content through the unstirred aqueous boundary layer adjacent to the intestinal epithelium. This transport is essential for bringing compounds like fat-soluble vitamins into direct contact with the apical membrane of enterocytes for absorption [6] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and their critical role in the absorption of lipophilic compounds.

Molecular-Scale Interactions at the Enterocyte Membrane

At the cellular level, absorption involves the spontaneous penetration of lipophilic molecules into the phospholipid bilayer of the enterocyte. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations reveal that the specific chemical structure of a compound dictates its orientation and dynamics within the membrane.

- Retinol (Vitamin A): With a hydroxyl (-OH) group at the tail of its structure, retinol exhibits high structural flexibility and a broad tilt angle within the dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) bilayer. It plugs its head group into the hydrocarbon core, demonstrating a high diffusion coefficient [6].

- α-Tocopherol (Vitamin E): Also possessing a hydroxyl group, but at its head group, α-tocopherol moves through one leaflet of the membrane and stabilizes in the opposite leaflet, facilitated by hydrogen bonding with phosphate groups [6].

- Phylloquinone (Vitamin K1): Lacking a hydroxyl group, phylloquinone stabilizes near the phosphate groups of the membrane without hydrogen bond formation. It penetrates at a precise tilting angle of 120° and has a low diffusion coefficient, suggesting higher retention in gel-phase membranes [6].

Quantitative Data on Factors Influencing Bioaccessibility

The efficiency with a lipophilic compound is released from its matrix and incorporated into micelles (its bioaccessibility) is quantitatively influenced by various dietary and physiological factors. The tables below summarize key experimental findings.

Table 1: Impact of Dietary Fibers on Carotenoid Bioaccessibility (In Vitro Digestion Model) [9]

| Dietary Fibre Type | Solubility | β-Carotene Bioaccessibility (% Change) | Lutein Bioaccessibility (% Change) | Lycopene Bioaccessibility (% Change) | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pectin | Soluble/Gelling | ▼ 38.5% (from 29.1% to 17.9%) | ▼ 55.4% (from 58.3% to 26.0%) | ▼ 25.0% (from 7.2% to 5.4%) | Increased viscosity, entrapment |

| Alginate | Soluble/Gelling | ▼ 59.5% (from 29.1% to 11.8%) | No significant impact | ▼ 43.1% (from 7.2% to 4.1%) | Increased viscosity, reduced lipid digestion |

| Guar Gum | Soluble/Gelling | No significant impact | No significant impact | ▼ 33.3% (from 7.2% to 4.8%) | Increased viscosity, reduced micelle size |

| Cellulose | Insoluble | No significant impact | No significant impact | No significant impact | No gelation, minimal effect |

| Resistant Starch | Insoluble | No significant impact | No significant impact | No significant impact | No gelation, minimal effect |

Table 2: Influence of Lipid Type on Drug Bioavailability (In Vivo Porcine Model) [8] [10]

| Parameter | Solid Lipid (Tristearin, TS) | Liquid Lipid (Triolein, TO) |

|---|---|---|

| Lipolysis Extent | Partial | Near-complete |

| Drug Adsorption | Negligible griseofulvin adsorption | N/A |

| Gastric Emptying | Faster in fasted state | Fed-state kinetics |

| Overall Bioavailability | No significant positive or negative effect | Enhanced for many lipophilic compounds |

| Proposed Mechanism | Inert carrier due to partial lipolysis | Efficient production of micelle-forming lipids |

Table 3: Association between Dietary Live Microbe Intake and Serum Fat-Soluble Vitamin Levels (NHANES Population Study) [12]

| Serum Vitamin | Low Intake Group (Reference) | Medium-High (MedHi) Intake Group (Adjusted Change) |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Baseline | + 0.17 μg/dL (95% CI: 0.04, 0.30) |

| Vitamin D | Baseline | + 0.36 nmol/L (95% CI: 0.22, 0.51) |

| Vitamin E | Baseline | + 4.65 μg/dL (95% CI: 1.91, 7.39) |

| Mechanistic Link | Gut microbiota modulation of bile acid metabolism, absorption pathways, and vitamin receptor expression. |

Experimental Protocols for Preclinical Assessment

In Vitro Lipolysis Model

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the impact of solid and liquid lipids on drug dissolution [8] [10].

Objective: To simulate the gastrointestinal lipolysis of a lipid-based formulation and measure the bioaccessibility of a co-administered lipophilic compound.

Materials:

- Simulated Intestinal Fluids (FeSSIF): Prepared according to established recipes, containing bile salts and phospholipids.

- Lipase Enzyme Preparation: Porcine pancreatic extract (e.g., 250 U/mg).

- Calcium Ion Solution: (e.g., 0.5 M CaCl₂) to stimulate lipase activity and precipitate fatty acids.

- pH-Stat Titrator: To automatically maintain pH and record the consumption of NaOH, which is proportional to free fatty acid release.

- Ultracentrifuge: For separation of the micellar phase.

Methodology:

- Initial Mixture: The lipid formulation containing the drug/vitamin is dispersed in FeSSIF under controlled temperature (37°C) and agitation.

- Lipolysis Initiation: Porcine pancreatin extract is added to the mixture to initiate digestion. The pH is automatically maintained at 6.5 using a pH-stat titrator with 0.2-0.6 M NaOH.

- Calcium Addition: A controlled volume of CaCl₂ solution is added incrementally to precipitate liberated fatty acids and drive the lipolysis reaction forward.

- Termination and Separation: After a set digestion period (e.g., 30-60 minutes), the reaction is stopped by adding a lipase inhibitor (e.g., Orlistat) or by ultracentrifugation (e.g., 40,000 rpm for 1 hour).

- Analysis: The aqueous phase (containing mixed micelles) is carefully sampled. The concentration of the drug/vitamin in this micellar phase is quantified via HPLC-UV/FLD or LC-MS/MS. Bioaccessibility is calculated as: (Mass in micellar phase / Total mass in digestion vessel) × 100%.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation of Membrane Absorption

This protocol is derived from computational studies of fat-soluble vitamin absorption into lipid bilayers [6].

Objective: To investigate the molecular-level interactions, orientation, and diffusion of a lipophilic compound within a model phospholipid bilayer.

Materials:

- Software: GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD.

- Force Fields: CHARMM36, GROMOS, or similar, with parameters for lipids and the compound of interest.

- Model Membrane: A pre-equilibrated bilayer of a specific phospholipid (e.g., 128 DPPC molecules).

- Ligand Structure: 3D molecular structure file of the vitamin/drug (e.g., from PubChem).

Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Place the ligand molecule approximately 40 Å from the center of the pre-equilibrated DPPC bilayer along the z-axis.

- Solvate the entire system (bilayer + ligand) in an explicit solvent model (e.g., SPC water) within a periodic boundary box.

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system and achieve physiological ionic strength.

- Energy Minimization: Use the steepest descent algorithm to remove steric clashes and bad contacts in the initial structure.

- Equilibration:

- Perform a short NVT simulation (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) to stabilize the system temperature at 310 K.

- Conduct a longer NPT simulation (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to achieve the correct density and stabilize the bilayer structure.

- Production Run: Execute a long-term MD simulation (e.g., 100-500 ns) with a 2-fs time step, saving trajectory data at regular intervals.

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Assess the stability of the ligand and bilayer.

- Density Profiles: Plot the probability distribution of specific atoms (e.g., ligand head group, phosphate groups of DPPC) along the bilayer normal (z-axis) to determine location.

- Hydrogen Bonding: Analyze the formation and lifetime of H-bonds between the ligand and lipid head groups.

- Diffusion Coefficient: Calculate the mean square displacement of the ligand within the bilayer to assess its mobility.

The workflow for the molecular-level investigation of vitamin absorption is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Models for Investigating Lipid-Soluble Compound Absorption

| Reagent / Model | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tristearin (TS) & Triolein (TO) | Model solid and liquid lipids for studying the impact of lipid physical state on lipolysis and bioavailability [8] [10]. | TS: Solid triglyceride (C18:0). TO: Liquid triglyceride (C18:1). |

| Sodium Taurodeoxycholate (NaTDC) | A common bile salt used in simulated intestinal fluids (e.g., FaSSIF/FeSSIF) for in vitro dissolution and lipolysis studies [8]. | Conjugated primary bile acid; provides critical micelle-forming capacity. |

| Porcine Pancreatin Extract | Source of digestive enzymes, including lipase, for in vitro lipolysis experiments [10] [9]. | Contains a physiologically relevant mix of enzymes; activity must be standardized (e.g., 250 U/mg). |

| DPPC Bilayer | A model phospholipid membrane for Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to study molecule-membrane interactions [6]. | Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine; well-characterized and widely used in computational studies. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates into enterocyte-like cells; a standard model for intestinal permeability screening. | Forms polarized monolayers with tight junctions and expresses relevant transporters. |

| Swine (Porcine) Model | In vivo model for preclinical bioavailability and food-effect studies due to physiological similarities to humans in GI tract and bile secretion [8] [10]. | Similar gallbladder anatomy, bile acid composition, and dietary habits to humans. |

The critical interdependence between dietary lipids, bile acid secretion, and the absorption of lipid-soluble compounds is a cornerstone of nutritional science and drug development. Evidence confirms that liquid lipids typically promote greater bioavailability than solid lipids via more complete lipolysis, and that the bile acid-driven formation of mixed micelles is the non-negotiable gateway to absorption for these compounds. Furthermore, external factors, particularly soluble gel-forming dietary fibers, can significantly impair bioaccessibility by altering the physicochemical environment of the gut.

Future research directions should focus on a more granular understanding of the gut microbiome's role, particularly through enzymes like bile salt hydrolase (BSH), in shaping the host's bile acid profile and its subsequent effect on the absorption of not only vitamins but also lipophilic drugs [11]. The application of advanced models, including the porcine in vivo model and sophisticated in silico MD simulations, will continue to be invaluable. Integrating these insights will empower the rational design of next-generation lipid-based drug delivery systems and precision nutrition strategies aimed at optimizing the health benefits of lipid-soluble bioactive compounds.

The biological activity of lipid-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) is entirely contingent upon sophisticated intracellular processing mechanisms that govern their activation, transport, and functional integration into cellular metabolism. Unlike their water-soluble counterparts, these vitamins leverage lipid-mediated pathways and complex enzymatic cascades to transform from dietary precursors into potent signaling molecules, antioxidants, and gene regulators [13] [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of these mechanisms—including the specific transport proteins such as scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), CD36, and Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1), and the enzymes that catalyze their activation—is paramount [13]. Disruptions in these processes are linked to diverse pathologies, from neurological disorders to cancer, highlighting their potential as therapeutic targets [13] [15]. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of intracellular processing for lipid-soluble vitamins, framed within contemporary research on their absorption and metabolism, and provides a toolkit of experimental methodologies for their investigation.

Core Mechanisms of Intracellular Processing

Transport Proteins and Cellular Uptake

Following absorption, lipid-soluble vitamins are distributed to target cells via chylomicrons and other lipoproteins [14]. Their cellular uptake is mediated by specific transport proteins that ensure targeted delivery and bioavailability.

Table 1: Key Transport Proteins for Lipid-Soluble Vitamins

| Vitamin | Key Transport Proteins | Cellular Uptake Mechanism | Tissue Specificity/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | SR-BI, CD36 [13] | Receptor-mediated endocytosis; lipid-mediated pathways [13] [14] | Critical for retinal function and cellular differentiation. |

| Vitamin D | SR-BI, CD36 [13] | Lipid-mediated pathways; carrier proteins in intestinal membrane [13] [16] | Liver and kidneys are primary sites for enzymatic activation [16]. |

| Vitamin E | SR-BI, CD36, NPC1L1 [13] | Lipid-mediated pathways; targeted by tocopherol transfer protein (TTP) in liver [13] [14] | TTP mutations cause vitamin E deficiency [14]. |

| Vitamin K | SR-BI, CD36, NPC1L1 [13] | Lipid-mediated pathways [13] | Gut microbiota synthesizes vitamin K2 [13] [14]. |

The role of these transporters is crucial for cellular homeostasis. For instance, the tocopherol transfer protein (TTP) in the liver specifically incorporates α-tocopherol (vitamin E) into lipoproteins for distribution to other tissues, and mutations in the TTP gene can lead to vitamin E deficiency [14].

Enzymatic Activation Pathways

Once inside the cell, most lipid-soluble vitamins must undergo enzymatic transformation to become biologically active.

- Vitamin A (Retinol): Retinol is converted to its active form, all-trans retinoic acid, within the cell. This process involves a two-step oxidation: first, retinol is oxidized to retinal by enzymes like alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), and then retinal is oxidized to retinoic acid by retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDHs) [14]. All-trans retinoic acid functions as a ligand for nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARs), which heterodimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) to act as transcription factors for genes governing cell differentiation, proliferation, and development [14].

- Vitamin D (Cholecalciferol): Vitamin D requires a two-step hydroxylation for activation. The first hydroxylation occurs in the liver, catalyzed by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2R1 (25-hydroxylase), which converts vitamin D to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the major circulating form and primary indicator of vitamin D status [14] [16]. The second hydroxylation occurs primarily in the kidneys, mediated by CYP27B1 (1α-hydroxylase), which produces the biologically active hormone 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], or calcitriol [14] [16]. This active form binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in the nucleus, regulating gene expression involved in calcium and phosphate homeostasis, immune function, and cell growth [16].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic activation pathway of vitamin D, from its precursor form to the active hormone that regulates gene expression.

- Vitamin E: The primary active form, α-tocopherol, itself functions as a potent antioxidant, protecting polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes from oxidative damage [14]. While not activated by a complex enzymatic pathway, its incorporation into cellular membranes is a critical step mediated by transport proteins.

- Vitamin K: Vitamin K acts as a cofactor for the enzyme γ-glutamyl carboxylase, which catalyzes the post-translational carboxylation of glutamate residues to form gamma-carboxyglutamate (Gla) in specific proteins [14]. This modification is essential for the activation of clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X) and proteins involved in bone metabolism [14]. During this reaction, vitamin K hydroquinone is oxidized to vitamin K epoxide, which is then recycled back to its active form by vitamin K epoxide reductase [14].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Processing Mechanisms

Protocol 1: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing to Elucidate Transporter Function

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the role of genes like SDR42E1 in vitamin D absorption and sterol metabolism [15].

Objective: To create a knock-in model of a gene of interest (e.g., SDR42E1) in a colorectal cell line (e.g., HCT116) to study its impact on vitamin D-related pathways.

Materials:

- HCT116 cells (or other relevant cell line)

- eSpCas9-2A-GFP (PX458) plasmid

- Donor DNA template containing the target mutation (e.g., nonsense variant p.Q30*) and a puromycin resistance cassette

- Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent

- Puromycin antibiotic

- Materials for RNA sequencing and proteomic analysis

Methodology:

- Guide RNA (gRNA) Design and Plasmid Construction: Design a gRNA specific to the exon of the target gene (e.g., exon 3 of

SDR42E1). Co-transfect HCT116 cells with the Cas9/gRNA plasmid and the donor DNA template using Lipofectamine 3000. - Selection and Cloning: After 48 hours, subject the cells to puromycin selection for two weeks to eliminate non-transfected cells. Isolate single-cell clones and expand them.

- Validation of Editing:

- Genotypic Validation: Perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing on genomic DNA from the clones to confirm the successful integration of the mutation.

- Phenotypic Validation: Confirm the loss of protein expression via Western blotting and immunofluorescence using a target-specific antibody.

- Functional Assays:

- Cell Viability: Assess the impact of the gene knock-in on cell viability using assays like MTT or CellTiter-Glo over 5-7 days.

- Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis: Extract total RNA and protein from wild-type and knock-in cells. Perform RNA sequencing and quantitative proteomic profiling (e.g., via LC-MS/MS) to identify differentially expressed genes and proteins. Pathway analysis can reveal disruptions in sterol absorption and cancer signaling pathways.

- Rescue Experiments: Transiently transfect the knock-in cells with a wild-type version of the gene to confirm the reversal of observed phenotypic effects.

Protocol 2: Cryo-EM Structural Analysis of Vitamin Transporters

This protocol outlines the process for determining the high-resolution structure of a human vitamin transporter, such as a riboflavin transporter, in complex with its substrate [17].

Objective: To determine the atomic structure of a human riboflavin transporter (RFVT2 or RFVT3) in different conformational states to understand the mechanism of riboflavin recognition and transport.

Materials:

- HEK293T cells

- Plasmid encoding the target transporter (e.g., RFVT2 or RFVT3)

- Plasmid for GFP-nanobody fiducial marker fusion

- [¹³C]riboflavin for functional assays

- Detergent for membrane protein purification

- Grids for cryo-EM sample preparation

Methodology:

- Construct Engineering and Expression: Fuse a GFP-nanobody fiducial marker to the target transporter (e.g., between E228-P262 for RFVT2) to create a larger complex for improved cryo-EM particle alignment. Express the engineered construct in HEK293T cells.

- Functional Validation of Construct: Perform transport assays to ensure the engineered construct retains wild-type function. Incubate transfected cells with [¹³C]riboflavin and measure accumulation using quantitative mass spectrometry. Determine kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) at different pH levels to confirm pH-dependent activity profile.

- Membrane Protein Purification: Solubilize the transporter from cell membranes using a suitable detergent. Purify the protein via affinity and size-exclusion chromatography in the presence of riboflavin.

- Cryo-EM Grid Preparation and Data Collection: Apply the purified protein sample to cryo-EM grids, vitrify them in liquid ethane, and collect a large dataset of micrographs using a high-end cryo-electron microscope.

- Image Processing and Model Building:

- Use software (e.g., RELION, cryoSPARC) for 2D classification, 3D classification, and refinement to generate high-resolution 3D density maps.

- Build an atomic model of the transporter into the density map, manually fitting amino acid side chains and the riboflavin ligand.

- Refine the model against the map and validate its geometry.

The workflow for this structural biology approach is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vitamin Processing Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Targeted gene editing to create knock-in/knockout models for functional genomics. | Used to introduce a nonsense variant (p.Q30*) in the SDR42E1 gene in HCT116 cells [15]. |

| Specialized Cell Lines | Models for studying tissue-specific absorption and metabolism. | HCT116 colorectal carcinoma cell line for intestinal vitamin D studies [15]. HEK293T cells for heterologous protein expression [17]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Vitamins | Tracers for quantitative uptake assays and metabolic flux studies. | [¹³C]riboflavin used in transport assays to measure accumulation via quantitative mass spectrometry [17]. |

| Tagging Systems for Structural Biology | Fiducial markers to facilitate structure determination of small membrane proteins. | GFP-nanobody fusion used to increase particle size and contrast for cryo-EM analysis of RFVTs [17]. |

| Pathway Analysis Software | Bioinformatics tools for interpreting omics data from transcriptomic and proteomic studies. | Used to identify dysregulation in sterol absorption and cancer signaling pathways in SDR42E1-deficient cells [15]. |

Quantitative Data in Vitamin Research

Table 3: Summary of Key Quantitative Data on Vitamins

| Vitamin | Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for Adults | Circulating Form & Half-Life | Deficiency Threshold (Serum) | Toxicity Level (Serum) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Male: 900 µg; Female: 800 µg [13] | Retinol [14] | < 0.70 µmol/L [14] | > 3.5 µmol/L [14] |

| Vitamin D | 15 µg (600 IU) [13] | 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D]; ~2-3 weeks [16] | < 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) [16] | > 100 ng/mL (risk of hypercalcemia) [14] |

| Vitamin E | 15 mg [13] | α-tocopherol [14] | < 5 µg/mL (Adults) [14] | Not well established [13] |

| Vitamin K | Male: 120 µg; Female: 90 µg [13] | Phylloquinone (K1), Menaquinone (K2) [14] | Prolonged Prothrombin Time (PT) [14] | Rare; no common toxicity [13] |

The intracellular processing of lipid-soluble vitamins represents a finely tuned interface of biophysics, biochemistry, and cell biology. The precise mechanisms of transport protein-mediated uptake and multi-step enzymatic activation are fundamental to their function as essential signaling molecules and cofactors. Contemporary research, leveraging advanced tools from gene editing to high-resolution structural biology, continues to unravel the complexity of these pathways and their profound impact on health and disease. The experimental frameworks and reagents detailed in this whitepaper provide a foundation for further investigation, which is crucial for developing targeted nutritional interventions and novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating these critical metabolic pathways.

The absorption and metabolism of lipid-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) represent a complex physiological process influenced by dietary intake, environmental factors, and genetic predisposition. While the fundamental pathways of absorption—including micelle formation, chylomicron packaging, and lymphatic transport—are well-established, significant interindividual variation exists in the efficiency of these processes [14]. A critical source of this variation lies in genetic polymorphisms, subtle DNA sequence variations that occur frequently within populations and can exert modest but biologically significant effects on gene function [18]. This whitepaper explores the genetic regulation of lipid-soluble vitamin absorption by focusing on key polymorphisms in four pivotal genes: the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR), the Vitamin D Binding Protein (GC), the Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase Complex (VKORC1), and Beta-Carotene Oxygenase 1 (BCO1). Understanding these genetic determinants is paramount for advancing personalized nutrition and developing targeted therapeutic strategies, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to a more precise, mechanism-based framework.

Core Genes and Polymorphisms

Vitamin D Receptor (VDR)

The VDR gene, located on chromosome 12q13.11, encodes a nuclear receptor that, upon activation by its ligand calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D), forms a heterodimer with the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR). This complex regulates the transcription of numerous genes involved in calcium and phosphate metabolism, immune function, and cellular proliferation [18]. Several polymorphisms in the VDR gene have been extensively studied for their impact on vitamin D responsiveness and disease risk.

- FokI (rs10735810): This C>T transition in exon 2 creates an alternative start codon, resulting in a truncated VDR protein (424 amino acids versus 427 for the "f" allele). The shorter "F" variant is associated with increased transcriptional activity and a better response to vitamin D supplementation [19].

- TaqI (rs731236): A silent T>C polymorphism in exon 9. The variant "t" allele (presence of the TaqI restriction site) has been associated with a better response to vitamin D supplementation in meta-analyses [19].

- BsmI (rs1544410) & ApaI (rs7975232): These linked polymorphisms in intron 8 do not alter the amino acid sequence of the VDR protein but may influence mRNA stability. Meta-analyses show no significant association between the BsmI and ApaI polymorphisms and the response to vitamin D supplementation [19].

Vitamin D Binding Protein (GC)

The GC gene encodes the Vitamin D Binding Protein (DBP), the primary plasma carrier for vitamin D metabolites. DBP is crucial for the transport and stabilization of vitamin D in circulation and modulates its delivery to target tissues [20]. The GC gene is highly polymorphic, with two common missense variants defining the major isoforms:

- rs7041: This G>T polymorphism results in an amino acid change (Asp→Glu) and defines the

GC1F(T allele) andGC1S(G allele) isoforms. - rs4588: This C>A polymorphism results in an amino acid change (Thr→Lys) and defines the

GC1S(C allele) andGC2(A allele) isoforms.

These polymorphisms significantly influence the concentration and affinity of DBP in plasma, thereby affecting the bioavailability of vitamin D metabolites. Specific haplotypes are associated with varying baseline levels of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D [20].

Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase Complex (VKORC1)

The VKORC1 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex, an essential enzyme that recycles vitamin K. This recycling is critical for the continuous gamma-carboxylation of vitamin K-dependent proteins, which are involved in coagulation (e.g., prothrombin) and bone metabolism (e.g., osteocalcin) [14] [21].

- rs9923231 (c.-1639G>A): This promoter polymorphism is the most extensively studied variant in

VKORC1. The A allele is associated with reducedVKORC1gene expression, leading to lower levels of the functional enzyme. This makes individuals more sensitive to vitamin K antagonists like warfarin, as less drug is required to inhibit the already reduced enzyme activity [22] [23]. This SNP accounts for approximately 20-25% of the variance in warfarin dosing requirements [22]. - rs61742245 (Asp36Tyr): This polymorphism has been associated with partial or complete resistance to vitamin K antagonists, requiring unusually high doses to achieve a therapeutic anticoagulant effect [21].

Beta-Carotene Oxygenase 1 (BCO1)

The BCO1 gene encodes the enzyme responsible for the central cleavage of provitamin A carotenoids, such as beta-carotene, into retinal (vitamin A aldehyde) in the intestine and liver [24] [20]. This is the key step in converting dietary carotenoids to bioactive vitamin A.

- rs12934922: A common polymorphism in

BCO1is associated with reduced enzymatic activity. Individuals carrying the variant allele exhibit a lower efficiency in converting beta-carotene to retinol, leading to higher fasting levels of beta-carotene and lower levels of vitamin A in the blood [20]. This genetic variation contributes to the substantial population variability observed in the vitamin A yield from plant-based diets.

Table 1: Key Polymorphisms Affecting Lipid-Soluble Vitamin Absorption and Metabolism

| Gene | Polymorphism | Major/Minor Allele | Functional Consequence | Clinical/Physiological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDR | FokI (rs10735810) | C (F) / T (f) | Alters start codon; shorter, more active protein (F) | The FF genotype is associated with a better response to vitamin D supplementation [19]. |

| VDR | TaqI (rs731236) | T (T) / C (t) | Silent mutation in exon 9 | The variant (Tt+tt) genotype is associated with a better response to vitamin D supplementation [19]. |

| GC | rs7041 | G / T | Determines GC1S/GC1F isoforms; affects DBP affinity/levels | Influences baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and bioavailability [20]. |

| GC | rs4588 | C / A | Determines GC1S/GC2 isoforms; affects DBP affinity/levels | Influences baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and bioavailability [20]. |

| VKORC1 | rs9923231 | G / A | Reduced gene expression; less functional enzyme | Increased sensitivity to warfarin; lower therapeutic dose requirement [22] [23]. |

| BCO1 | rs12934922 | A / T | Reduced enzymatic cleavage activity | Decreased conversion of beta-carotene to retinal; higher beta-carotene, lower vitamin A levels [20]. |

Molecular and Physiological Impact

The polymorphisms described in Section 2 exert their influence through diverse molecular mechanisms, ultimately shaping an individual's physiological response to lipid-soluble vitamins.

The VDR FokI polymorphism directly alters the structure of the receptor protein. The shorter "F" variant is believed to be a more potent transactivator of target genes. This translates to a system that is more responsive to a given level of vitamin D, explaining why individuals with the FF genotype show a greater increase in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels after supplementation compared to those with the ff genotype [19]. In contrast, the VKORC1 rs9923231 polymorphism acts at the regulatory level. The A allele leads to reduced transcription of the VKORC1 gene, resulting in a lower basal amount of the enzyme available for vitamin K recycling [22]. When a vitamin K antagonist like warfarin is administered, it more readily inhibits the limited enzyme pool, producing a pronounced anticoagulant effect at a standard dose.

The GC polymorphisms affect the transport and reservoir function of the vitamin D system. Different DBP isoforms have varying affinities for vitamin D metabolites, which influences the fraction of free, bioavailable hormone versus the protein-bound fraction. This can affect the delivery of vitamin D to target tissues and its overall metabolic clearance rate [20]. Finally, BCO1 polymorphisms directly impact nutritional biochemistry. A less active BCO1 enzyme, as seen with the rs12934922 variant, creates a functional bottleneck. Dietary beta-carotene is less efficiently converted to vitamin A, leading to its accumulation and reduced retinol synthesis. This has significant implications for populations relying on plant-based sources for their vitamin A requirements [24] [20].

Table 2: Summary of Physiological Impact and Research Considerations

| Gene | Key Physiological Role | Impact of Significant Polymorphism | Primary Tissue/Cell Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| VDR | Genomic signaling; regulation of calcium homeostasis, immune function, cell differentiation. | Altered transcriptional response to 1,25(OH)2D; differences in bone density, immune response, and cancer risk [19] [18]. | Intestine, Bone, Kidney, Immune Cells |

| GC | Transport and stabilization of vitamin D metabolites in circulation. | Altered baseline 25(OH)D levels and vitamin D bioavailability; potential association with disease risk [20]. | Liver (synthesis), Plasma |

| VKORC1 | Recycling of vitamin K for activation of coagulation and bone proteins. | Altered sensitivity to vitamin K antagonists (warfarin); potential impact on baseline gamma-carboxylation status [21] [22]. | Liver, Bone |

| BCO1 | Conversion of provitamin A carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene) to retinal (Vitamin A). | Reduced vitamin A synthesis from plant sources; variability in provitamin A bioavailability [24] [20]. | Intestinal Enterocytes, Liver |

Experimental and Methodological Approaches

Research into the genetic regulation of vitamin absorption relies on robust methodologies for genotyping, functional validation, and clinical assessment.

Genotyping Techniques

- Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (PCR-RFLP): This traditional method involves amplifying the target gene region containing the polymorphism, followed by digestion with a restriction enzyme that cuts the DNA only in the presence (or absence) of the variant. The resulting fragment patterns are visualized by gel electrophoresis to determine the genotype. This method was used in several of the

VDRstudies included in the meta-analysis [19]. - Sanger Sequencing: Considered the gold standard for validating genetic variants, this technique determines the exact nucleotide sequence of a DNA fragment. It is highly accurate but can be more costly and lower throughput than other methods. It was utilized for confirming

VKORC1polymorphisms in the case reports of warfarin resistance [21]. - Real-Time PCR (qPCR) and Advanced Arrays: Modern high-throughput approaches use TaqMan allele-specific probes or genotyping arrays that can simultaneously assay hundreds of thousands of SNPs across the genome. These methods are essential for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that have identified novel genetic contributors to warfarin dose response, such as polymorphisms in

CYP4F2[22].

Functional and Clinical Assessment

- Vitamin Status Biomarkers: The functional impact of polymorphisms is assessed by measuring specific biomarkers before and after an intervention.

- Vitamin D: Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is the best indicator of overall vitamin D status [14].

- Vitamin K: Functional status is often assessed indirectly via Prothrombin Time (PT)/International Normalized Ratio (INR) for coagulation, or by measuring levels of undercarboxylated osteocalcin in bone [14] [25].

- Vitamin A: Serum retinol levels and the relative proportion of beta-carotene can indicate

BCO1activity [20].

- Clinical Outcome Measures: For

VDR, studies correlate genotypes with Bone Mineral Density (BMD) or fracture risk [25]. ForVKORC1, the primary outcome is the stable therapeutic warfarin dose or the time-in-therapeutic INR range [22] [23]. - In Vitro Studies: Cell culture models (e.g., transfected cell lines) are used to study the mechanistic impact of a polymorphism, such as measuring the transcriptional activity of different

VDRFokI variants in response to calcitriol [18].

Figure 1: Vitamin D Metabolic and Signaling Pathway. The diagram illustrates the activation of vitamin D and its genomic action via the VDR/RXR heterodimer. The location where the FokI polymorphism impacts the system is highlighted in red.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic and Functional Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Specific Example / Kit | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality genomic DNA isolation from whole blood or buccal swabs for downstream genotyping. |

| PCR-RFLP Reagents | Thermo Scientific FastDigest Restriction Enzymes (e.g., TaqI, FokI) | Amplification and allele-specific digestion of target gene sequences for cost-effective genotyping. |

| TaqMan Genotyping Assay | Applied Biosystems TaqMan Drug Metabolism Genotyping Assays | High-throughput, real-time PCR-based allele discrimination for specific SNPs (e.g., CYP2C9*2, *3, VKORC1). |

| Vitamin D ELISA | DIAsource 25-OH Vitamin D TOTAL ELISA | Quantification of total serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels to correlate genotype with vitamin D status. |

| Vitamin K HPLC-MS/MS | - | High-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry for precise quantification of vitamin K isoforms (K1, MK-4, MK-7) in plasma or tissues. |

| BCO1 Activity Assay | In vitro cleavage assay with β-carotene substrate and recombinant BCO1 variants. | Measurement of enzymatic kinetics to determine the functional impact of BCO1 polymorphisms on provitamin A conversion. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The study of polymorphisms in VDR, GC, VKORC1, and BCO1 provides a powerful mechanistic framework for understanding the heritable component of lipid-soluble vitamin absorption and metabolism. The evidence clearly demonstrates that common genetic variations can significantly alter protein function, nutrient status, and response to supplementation and medication. This knowledge is foundational to the field of precision nutrition, where dietary recommendations and therapeutic interventions can be tailored to an individual's genetic makeup.

Future research must focus on integrating these genetic factors with other critical dimensions. A key consideration is the distinction between nutrients from whole foods versus supplemental forms, as their metabolic effects and health outcomes may differ substantially [25]. Furthermore, gene-environment interactions and gene-diet interactions are crucial; the phenotypic expression of a genetic variant often depends on contextual factors like overall dietary patterns, sun exposure (for vitamin D), and the use of medications [18]. For instance, the effect of VKORC1 genotype is only manifest upon administration of a vitamin K antagonist.

Future studies should prioritize several areas:

- Long-Term Clinical Outcomes: Moving beyond intermediate biomarkers like serum nutrient levels to harder endpoints such as fracture risk for vitamin D or cancer incidence.

- System-Level Integration: Investigating how polymorphisms in these different genes interact with each other (e.g.,

VDRandGC) to jointly influence vitamin D physiology. - Functional Characterization: Continued work is needed to fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which non-coding polymorphisms (e.g.,

VKORC1rs9923231) exert their effects. - Diverse Populations: Expanding research beyond predominantly European ancestries to ensure the global applicability of genetic findings.

In conclusion, the genetic regulation of lipid-soluble vitamin absorption is a sophisticated and multi-layered system. A deep understanding of polymorphisms in VDR, GC, VKORC1, and BCO1 equips researchers and clinicians with the insights needed to decode interindividual variability, paving the way for more effective and personalized healthcare strategies.

The small intestine, a highly specialized organ system primarily responsible for nutrient absorption, is anatomically and functionally segmented into three distinct parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum [5]. This structural specialization enables efficient processing and uptake of diverse nutrients, with each segment exhibiting unique cellular architectures, membrane compositions, and molecular transport mechanisms optimized for specific dietary components. Within the context of lipid-soluble vitamin absorption research, understanding these regional differentiations is crucial for elucidating the complex absorption mechanisms of vitamins A, D, E, and K, and for developing targeted therapeutic interventions for malabsorption syndromes.

The gastrointestinal tract's wide range of functions includes nutrient absorption after the breakdown of carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals, all essential for energy production, growth, and cellular maintenance [5]. This review systematically examines the comparative anatomy of duodenal, jejunal, and ileal absorption sites, with particular emphasis on their specialized roles in lipid-soluble vitamin assimilation and the experimental methodologies employed in this field of research.

Anatomical Segmentation and Regional Specializations

Macroscopic Organization

The small intestine exhibits progressive anatomical specialization along its approximately 9-meter length, with each segment demonstrating distinct structural and functional characteristics [5]:

Duodenum: The proximal segment measuring approximately 30 cm (1 foot) in length, which receives the food-acid mixture from the stomach (chyme) along with secretions from the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder [5].

Jejunum: The middle segment measuring approximately 244 cm (8 feet) in length, characterized by prominent circular folds (valves of Kerckring) and villi that maximize absorptive surface area [5] [26].

Ileum: The most distal segment measuring approximately 150-350 cm (5-11.5 feet) in length, distinguished by the presence of Peyer's patches and terminating at the ileocecal valve [5] [27] [26].

Table 1: Anatomical and Functional Characteristics of Small Intestinal Segments

| Parameter | Duodenum | Jejunum | Ileum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | ~30 cm (1 foot) [5] | ~244 cm (8 feet) [5] | ~150-350 cm (5-11.5 feet) [5] [27] |

| Primary Absorptive Functions | Iron, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, copper, selenium, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, biotin, folate, fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, K [5] | Lipids (as glycerol and free fatty acids), amino acids, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenate, biotin, folate, pyridoxine, ascorbic acid, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, iron, zinc, chromium, manganese, molybdenum, lipids, monosaccharides, small peptides, fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, K [5] | Bile salts, vitamin B12, ascorbic acid, folate, cobalamin, vitamin D, vitamin K, magnesium [5] [27] |

| Specialized Structures | Brunner's glands, prominent circular folds [5] | Well-developed circular folds, long villi [5] [26] | Peyer's patches, less prominent circular folds [27] [26] |

| pH Environment | Acidic (receives gastric chyme) [5] | Neutral to slightly alkaline [5] | Neutral to slightly alkaline [5] |

| Lymphoid Tissue | Limited | Moderate | Extensive (Peyer's patches) [26] |

Microanatomical Specializations

Brush Border Architecture

The luminal surface of all three intestinal segments features a brush border composed of microvilli, which are approximately 100 nanometers in diameter and vary in length from 100 to 2,000 nanometers [28]. These tightly packed cytoplasmic projections dramatically increase the apical surface area of enterocytes, facilitating efficient nutrient absorption. The brush border membrane anchors various digestive enzymes as integral membrane proteins, positioning them near specific transporters for prompt absorption of digested nutrients [28].

Research on brush border assembly during development reveals that microvilli formation is a rapid, coordinated process that dramatically expands the digestive and absorptive surface area before the completion of villi maturation [29]. Gene expression studies of microvilli structural components show distinct patterns for Plastin 1 (which bundles and binds actin cores to the terminal web), Ezrin, and Myo1a (both actin core-cell membrane cross-linkers), suggesting sophisticated regulation of brush border assembly and function [29].

Cellular Composition

The intestinal epithelium comprises several specialized cell types that contribute to its absorptive and immunologic functions:

Enterocytes: The predominant cells responsible for nutrient absorption, featuring extensive microvilli on their apical surface [5].

Goblet cells: Scattered between enterocytes, these cells produce alkaline mucus that protects the gastrointestinal lining from shearing forces and acidic secretions [5].

Enteroendocrine cells: Responsible for secreting various hormones including ghrelin, cholecystokinin, glucagon-like peptide 1, and peptide YY, which regulate digestion and nutrient absorption [5].

Microfold (M) cells: Specialized epithelial cells overlying Peyer's patches that sample antigens from the intestinal lumen for immune surveillance [5] [26].

Paneth cells: Located in the crypts, these cells secrete antimicrobial peptides and proteins that regulate gut microbiota and inflammation [5].

The distribution and density of these specialized cell types vary along the length of the small intestine, contributing to segment-specific functional capabilities.

Region-Specific Absorption Mechanisms

Duodenal Absorption Specializations

The duodenum serves as the primary site for mineral absorption and the initial phase of lipid-soluble vitamin uptake. Its unique position immediately distal to the stomach allows it to receive highly acidic chyme, which is subsequently neutralized by pancreatic and biliary secretions to create an optimal environment for nutrient assimilation [5].

The duodenum absorbs most of the iron, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, copper, selenium, and multiple B vitamins (thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, biotin, folate), in addition to the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K [5]. The absorption of fat-soluble vitamins occurs through a sophisticated process involving incorporation into micelles - lipid clusters with hydrophobic groups internally and hydrophilic groups externally - which depends on bile secretion and pancreatic enzymes [14]. Following absorption into enterocytes, fat-soluble vitamins are packaged into chylomicrons and secreted into the lymphatic system before entering the bloodstream [14].

Jejunal Absorption Specializations

The jejunum represents the principal site for absorption of dietary lipids, amino acids, and monosaccharides, facilitated by its extensive surface area resulting from well-developed circular folds and long villi [5] [26]. The jejunal enterocytes possess highly specialized transport mechanisms for nutrient uptake:

Lipid Absorption: Dietary triglycerides are broken down into monoglycerides and free fatty acids that incorporate into mixed micelles with bile salts. These micelles transport lipid components to the enterocyte brush border where passive diffusion occurs. Within the enterocyte, resynthesis of triglycerides takes place, followed by incorporation into chylomicrons for transport via lymphatic circulation [5].

Protein Absorption: Peptides and amino acids are transported across the brush border membrane via specific carrier-mediated mechanisms, including sodium-dependent and sodium-independent transport systems [5].

Carbohydrate Absorption: Monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, fructose) are absorbed through active transport (SGLT1 transporter) and facilitated diffusion (GLUT5 transporter) mechanisms [5].

Experimental studies in diabetic rat models have demonstrated that jejunal morphology and brush border membrane composition are dynamically regulated in response to dietary modifications and metabolic states [30]. These adaptations include alterations in villus height and brush border membrane enzyme activities (sucrase and alkaline phosphatase), as well as changes in membrane phospholipid composition, particularly in response to variations in dietary carbohydrate content [30].

Ileal Absorption Specializations

The ileum exhibits several unique absorptive specializations, particularly for vitamin B12 and bile acids, despite its less permeable lining and slower peristaltic contractions compared to proximal segments [27]. The ileum contains specific receptors for vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complexes and bile salts that are exclusively present in its lining [27] [26].

Vitamin B12 Absorption: The process of vitamin B12 absorption involves a sophisticated multi-step mechanism. In the stomach, dietary B12 is released from protein complexes and binds to R-protein (cobalophilin, haptocorrin). In the small intestine, pancreatic enzymes liberate B12 from R-protein, allowing it to bind to intrinsic factor produced by gastric parietal cells. This B12-intrinsic factor complex then travels to the ileum, where specific receptors mediate its uptake into enterocytes [31]. The absorbed B12 subsequently binds to transcobalamin II for transport in the bloodstream [31].

Bile Salt Absorption: The ileum efficiently reabsorbs approximately 95% of conjugated bile salts through specific active transport mechanisms, facilitating enterohepatic circulation [27]. This recycling process is essential for maintaining adequate bile salt pools for efficient lipid digestion and absorption.

Immunological Specialization: The ileum contains abundant lymphoid follicles (Peyer's patches) that constitute an important component of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) [26]. M cells within the follicle-associated epithelium sample luminal antigens and deliver them to antigen-presenting cells, initiating appropriate immune responses [26].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo Animal Models

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats have been extensively utilized to investigate the effects of metabolic disorders and dietary interventions on intestinal morphology and function [30]. The following protocol outlines a representative experimental approach:

Animal Model Development:

- Induce hyperglycemia in experimental rats via streptozotocin administration

- Maintain control and diabetic animals for 2 weeks on defined diets varying in carbohydrate, essential fatty acid, cholesterol, or protein content

- Implement strict glycemic monitoring throughout the study period

Tissue Collection and Processing:

- Euthanize animals at predetermined timepoints

- Rapidly excise jejunal segments and flush with ice-cold physiological buffer

- Process tissue for:

- Morphological analysis (villus height measurements)

- Brush border membrane isolation and compositional analysis

- Enzyme activity assays (sucrase, alkaline phosphatase)

- Membrane lipid composition analysis

Analytical Techniques:

- Histological examination using light and electron microscopy

- Spectrophotometric enzyme activity measurements

- Lipid extraction and chromatographic separation

- Statistical analysis of diet-induced and diabetes-related alterations

This experimental paradigm has demonstrated that dietary manipulations produce significant changes in jejunal morphology and brush border membrane composition in both control and diabetic animals, including alterations in villus height and membrane enzyme activities [30]. Furthermore, brush border membrane phospholipids show specific modifications in response to variations in dietary carbohydrate and protein content, with differential effects observed between control and diabetic states [30].

Brush Border Assembly Studies

Research on intestinal brush border assembly during the peri-hatch period in chickens has provided insights into the developmental regulation of microvilli formation and maturation [29]. The experimental methodology includes:

Developmental Time Course Analysis:

- Sample small intestines at multiple developmental stages (prehatch ages 17E and 19E, day of hatch, and posthatch days 1, 3, 7, and 10)

- Process tissues for morphological, molecular, and gene expression analyses

Morphological Assessments:

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for detailed microvilli visualization

- Light microscopy for general histological evaluation

- Quantitative measurements of microvilli length, villi length, microvilli amplification factor, and total enterocyte surface area

Molecular Analyses:

- Real-Time qPCR analysis of microvilli structural genes (Plastin 1, Ezrin, Myo1a)

- Correlation of gene expression patterns with morphological development

These investigations have revealed that microvilli assembly is a rapid, coordinated process that dramatically expands the digestive and absorptive surface area before the completion of villi maturation [29]. The expression patterns of microvilli structural genes portray diverse developmental regulation, suggesting complex control mechanisms underlying brush border formation [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Intestinal Absorption Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [30] | Metabolic studies | Models diabetes-induced alterations in intestinal morphology and function |

| Broiler embryos and chicks [29] | Developmental studies | Investigates brush border assembly during peri-hatch development | |

| Histological Tools | Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [29] | Morphological analysis | High-resolution visualization of microvilli structure |

| Light microscopy [29] | General histology | Tissue structure evaluation and villi measurements | |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Real-Time qPCR assays [29] | Gene expression analysis | Quantification of microvilli structural gene expression (Plastin 1, Ezrin, Myo1a) |

| Enzyme Activity Assays | Sucrase activity measurement [30] | Brush border function | Assessment of brush border membrane digestive capacity |

| Alkaline phosphatase assay [30] | Membrane integrity | Evaluation of brush border membrane organization and function | |

| Membrane Analysis Methods | Lipid extraction and chromatography [30] | Membrane composition | Analysis of brush border membrane phospholipid and cholesterol content |

| Dietary Formulations | Defined carbohydrate, protein, fat diets [30] | Nutritional studies | Investigation of diet-induced intestinal adaptations |

Visualization of Inter-segmental Relationships and Experimental Approaches

Nutrient Absorption Specialization by Intestinal Segment

Experimental Workflow for Intestinal Absorption Research

Implications for Lipid-Soluble Vitamin Absorption Research

The segmental specializations of the small intestine have profound implications for understanding the absorption mechanisms of lipid-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). These vitamins share common absorption pathways that depend on adequate bile secretion, pancreatic function, and micelle formation, primarily occurring in the duodenum and jejunum [14]. However, specific aspects of their metabolism exhibit segmental preferences:

Vitamin A: Absorbed primarily in the duodenum and jejunum as retinol, with involvement in epithelial cell differentiation and proliferation throughout the intestinal tract [14].

Vitamin D: Undergoes complex activation involving hepatic and renal hydroxylation, with absorption of dietary vitamin D occurring mainly in the proximal small intestine [14].

Vitamin E: As the principal lipid-soluble antioxidant, vitamin E (α-tocopherol) absorption occurs predominantly in the jejunum, with specific tocopherol transfer proteins facilitating its incorporation into lipoproteins in the liver [14].

Vitamin K: Absorbed via both dietary sources (phylloquinone) in the proximal intestine and microbial synthesis (menaquinone) in the colon, with efficient jejunal uptake mechanisms [14].