Mechanistic Links Between Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Innovation

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on the biological mechanisms through which dietary patterns influence chronic disease risk, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mechanistic Links Between Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current scientific evidence on the biological mechanisms through which dietary patterns influence chronic disease risk, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores foundational pathways like hyperinsulinemia and inflammation, examines methodological approaches for studying diet-disease interactions, addresses complexities such as food-drug interactions and research biases, and provides a comparative analysis of the protective efficacy of major dietary patterns like the MIND, DASH, and Mediterranean diets. The review aims to inform the integration of nutritional science into targeted therapeutic strategies and precision medicine frameworks.

Core Biological Pathways: How Diet Modulates Chronic Disease Risk

Hyperinsulinemia, characterized by elevated circulating insulin levels, has emerged as a critical pathophysiological mechanism linking modern dietary patterns to the development of major chronic diseases. As obesity and metabolic syndrome reach epidemic proportions globally, with insulin resistance affecting an estimated 51% of the population in developed and developing countries, the role of hyperinsulinemia as a unifying driver of chronic disease requires urgent research attention [1]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence demonstrating how dietary patterns promote hyperinsulinemia, which in turn serves as a central mechanism initiating and propagating multiple disease processes, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [2] [1] [3].

The evolutionary conservation of insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling pathways underscores their fundamental role in metabolism, growth, and longevity [4]. In contemporary populations, chronic consumption of pro-hyperinsulinemic diets generates a persistent state of elevated insulin that dysregulates these ancient pathways, creating a permissive environment for disease development. This review examines the mechanistic evidence connecting hyperinsulinemia to major chronic diseases, provides detailed experimental methodologies for investigating these relationships, and outlines key signaling pathways that represent potential therapeutic targets for researchers and drug development professionals.

Dietary Patterns and Hyperinsulinemia: Epidemiological and Clinical Evidence

Strong evidence from multiple large-scale prospective cohorts demonstrates that specific dietary patterns significantly influence hyperinsulinemia risk and subsequent chronic disease development. Research using empirically-derived dietary indices has identified distinct patterns that directly impact insulinemic and inflammatory responses.

Table 1: Dietary Patterns and Their Association with Chronic Disease Risk

| Dietary Pattern | Key Components | Biomarker Impact | Disease Risk Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperinsulinemic (High EDIH) | Red meat, processed meat, poultry, refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages [5] | ↑ C-peptide, ↑ HOMA-IR, ↑ triglycerides, ↓ HDL-C, ↓ adiponectin [5] | Major chronic disease HR: 1.42-1.72 [2] |

| Pro-inflammatory (High EDIP) | Red meat, processed meat, refined grains, high-energy beverages [5] | ↑ CRP, ↑ IL-6, ↑ TNF-αR2, ↑ triglycerides [5] | Strong association with T2D, CVD, cancer [5] |

| Low Insulinemic (Low EDIH) | Wine, whole fruit, coffee, green leafy vegetables [5] | ↓ C-peptide, ↓ HOMA-IR, ↑ HDL-C, ↑ adiponectin [5] | Major chronic disease HR: 0.58-0.80 [2] |

| Western Pattern | Soft drinks, refined grains, pastries, corn tortillas [6] | ↑ Fasting glucose, ↓ HDL-C, ↑ triglycerides [6] | MetS OR: 1.56 (95% CI: 1.31-1.88) [6] |

| High-Fiber Nutrient-Dense | Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish [7] | Improved glucose metabolism, lipid profiles [7] | Reduced T2DM risk [7] |

Data from the Women's Health Initiative (n=35,360 postmenopausal women) demonstrated that the Empirical Dietary Index for Hyperinsulinemia (EDIH) and Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP) significantly associated with altered concentrations of 25 of 40 biomarkers examined, including insulin resistance, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and dyslipidemia markers [5]. The hyperinsulinemic dietary pattern increased homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) by +8%, C-reactive protein by +7.8%, and reduced HDL cholesterol by -2.4% [5].

A prospective study of 205,852 healthcare professionals followed for up to 32 years demonstrated that participants with low-insulinemic dietary patterns had the largest risk reduction for incident major cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer as a composite outcome, with hazard ratios comparing the 90th with the 10th percentile of dietary pattern scores ranging from 0.58 to 0.80 [2]. Notably, the low insulinemic (HR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.57, 0.60) and low inflammatory (HR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.60, 0.63) diets demonstrated the most substantial protective effects [2].

Hyperinsulinemia as a Unifying Pathogenic Mechanism

Molecular Pathways Linking Hyperinsulinemia to Chronic Disease

Hyperinsulinemia exerts its pathogenic effects through multiple interconnected molecular pathways that create a permissive environment for chronic disease development. The underlying mechanisms involve complex interactions between insulin signaling pathways, inflammatory processes, and cellular growth regulation.

Under insulin resistance conditions, the phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3-K) dependent metabolic pathway becomes specifically impaired, while the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent pathway remains sensitive to insulin or becomes overstimulated by compensatory hyperinsulinemia [1]. This imbalance creates a pathophysiological state where the metabolic actions of insulin are diminished while the growth-promoting and inflammatory effects are disproportionately enhanced [1] [4].

The PI3-K pathway primarily mediates insulin's metabolic actions, including regulation of glucose metabolism in muscle, adipose tissue, and liver, as well as nitric oxide (NO) production by endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells [1]. When this pathway is impaired, NO production decreases, leading to endothelial dysfunction. Concurrent overstimulation of the MAPK pathway promotes secretion of endothelin-1 (ET-1), a potent vasoconstrictor, and stimulates mitogenic and proliferative actions that can contribute to cancer development [1] [4].

Tissue-Specific Pathogenic Mechanisms

Cardiovascular System

Hyperinsulinemia promotes cardiovascular damage through multiple mechanisms. It induces hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system and stimulates renal sodium reabsorption, contributing to hypertension [1]. The PI3-K/MAPK pathway imbalance creates endothelial dysfunction through reduced NO and increased ET-1 production, establishing a pro-atherogenic environment [1]. Persistent hyperinsulinemia also promotes atherogenic dyslipidemia characterized by elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, and increased small, dense LDL particles [1] [8].

Cancer Development

Hyperinsulinemia contributes to carcinogenesis through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Insulin acts as a growth factor for epithelial cells, binding to insulin receptors (INSR) and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors (IGF-1R) to activate the MAPK and PI3-K signaling pathways that stimulate cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis [3] [4]. A prospective cohort study demonstrated that hyperinsulinemia (defined as fasting insulin ≥10 μU/mL) was associated with significantly higher cancer mortality among nonobese participants without diabetes (adjusted HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.07-3.35) [3].

Recent research has elucidated tissue-specific mechanisms, such as in pancreatic cancer where hyperinsulinemia acts via acinar insulin receptors to initiate pancreatic cancer by increasing digestive enzyme production and inflammation [9]. This mechanism demonstrates how organ-specific insulin signaling can create a permissive microenvironment for carcinogenesis.

Metabolic Dysregulation and Type 2 Diabetes

Hyperinsulinemia initially compensates for insulin resistance but eventually leads to β-cell exhaustion and apoptosis through ER stress and oxidative damage [4]. The persistent lipid abnormalities associated with hyperinsulinemic states, particularly elevated triglycerides and reduced HDL-C, further exacerbate insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [8]. This creates a vicious cycle where hyperinsulinemia begets further metabolic dysfunction.

Experimental Models and Research Methodologies

Dietary Pattern Assessment and Validation

The following methodology details the approach used to develop and validate empirical dietary patterns for hyperinsulinemia research, as implemented in large cohort studies [5]:

Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) Administration

- Utilize a validated semi-quantitative FFQ with 122+ food items

- Assess dietary intake over preceding 3-month period

- Collect data on portion sizes using standardized instruments (e.g., food photographs, standard serving sizes)

- Convert consumption frequencies to daily intake values (servings/day)

Dietary Pattern Calculation

- Calculate Empirical Dietary Index for Hyperinsulinemia (EDIH) scores using 18 weighted food groups

- Food groups promoting hyperinsulinemia: red meat, processed meat, poultry, refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages

- Food groups reducing hyperinsulinemia: wine, whole fruit, coffee, green leafy vegetables

- Compute overall EDIH score as weighted sum of food group intakes

Biomarker Validation

- Collect fasting blood samples

- Measure insulin-related biomarkers: C-peptide, insulin, glucose, HOMA-IR

- Measure inflammatory biomarkers: CRP, IL-6, TNF-αR2

- Measure lipid biomarkers: triglycerides, HDL-C, LDL-C, total cholesterol

- Use linear regression to assess associations between dietary patterns and biomarkers, adjusting for potential confounders (age, BMI, physical activity, smoking, etc.)

Table 2: Key Methodological Approaches in Hyperinsulinemia Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment | FFQ, 24-hour recalls, dietary records | Establishing dietary patterns linked to hyperinsulinemia | FFQ efficient for large cohorts but subject to recall bias [5] |

| Insulin Resistance Measurement | HOMA-IR, TyG index, euglycemic clamp | Quantifying insulin resistance and β-cell function | HOMA-IR practical for epidemiology; clamp gold standard but resource-intensive [1] |

| Biomarker Profiling | Multiplex immunoassays, ELISA, clinical chemistry | Comprehensive metabolic phenotyping | Enables pattern analysis across multiple biological pathways [5] |

| Genetic Manipulation | Tissue-specific knockout mice (e.g., acinar Insr knockout) | Establishing causal mechanisms | Demonstrates tissue-specific insulin effects [9] |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary acinar cells, cancer cell lines | Elucidating molecular mechanisms | Controlled environment but may not fully recapitulate in vivo physiology [9] |

In Vivo Models of Hyperinsulinemia-Disease Relationships

Recent innovative approaches have established causal relationships between hyperinsulinemia and disease development:

Pancreatic Cancer Model [9]

- Utilize KrasG12D-expressing mice as pancreatic cancer model

- Generate acinar cell-specific insulin receptor knockout (InsrΔacinar)

- Expose to high-fat diet to induce hyperinsulinemia

- Monitor PanIN formation and progression

- Measure digestive enzyme production and local inflammation

- Assess insulin signaling pathway activation in acinar cells

Mechanistic Findings: Insulin receptor loss in acinar cells did not affect glucose metabolism but prevented hyperinsulinemia-driven pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) formation, demonstrating that direct insulin action on acinar cells via insulin receptors is necessary for obesity-driven pancreatic cancer initiation [9].

Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hyperinsulinemia Mechanisms Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Assessment Tools | WHI FFQ, NHS FFQ [5] | Dietary pattern characterization | Validated instruments for quantifying food intake |

| Biomarker Assays | C-peptide ELISA, CRP immunoassay, insulin ELISA [5] | Biomarker quantification | Objective measures of insulin response and inflammation |

| Genetic Models | KrasG12D mice, Insr floxed mice [9] | Tissue-specific mechanism studies | Enable conditional gene knockout in specific cell types |

| Cell Culture Systems | Primary acinar cells, pancreatic cancer cell lines [9] | In vitro mechanism studies | Permit controlled manipulation of insulin signaling |

| Metabolic Phenotyping | HOMA-IR calculation, TyG index [1] | Insulin resistance assessment | Practical indices correlating with gold-standard measures |

| Pathological Assessment | Histology for PanIN classification [9] | Disease progression monitoring | Standardized cancer precursor identification |

The evidence synthesized in this whitepaper establishes hyperinsulinemia as a central mechanistic pathway linking modern dietary patterns to increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. The bidirectional relationship between specific dietary components and hyperinsulinemia creates a self-reinforcing cycle that drives chronic disease pathogenesis through multiple molecular mechanisms.

Priority research directions include:

- Developing targeted interventions to disrupt the hyperinsulinemia-disease pathway

- Elucidating tissue-specific insulin signaling mechanisms in different disease contexts

- Establishing optimal dietary patterns for hyperinsulinemia reduction across diverse populations

- Investigating the potential of insulin-lowering strategies for cancer prevention and treatment

The profound impact of hyperinsulinemia on multiple disease states highlights the urgent need for continued mechanistic research and therapeutic development in this area. Research efforts should prioritize understanding the nuanced relationships between dietary factors, insulin dynamics, and disease-specific pathological processes to enable more effective prevention and treatment strategies for the growing burden of hyperinsulinemia-related chronic diseases.

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a fundamental pathological process underlying a wide spectrum of non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and diabetes [10]. Dietary components exert a profound influence on systemic inflammation, acting through complex interactions with immune signaling pathways, the gut microbiome, and cellular aging processes [11] [10]. The inflammatory potential of diet is not merely the sum of individual nutrient effects but represents a synergistic interplay of bioactive compounds that can either promote or resolve inflammatory states [10]. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for developing targeted nutritional strategies to mitigate chronic disease risk and progression.

Emerging evidence from large-scale cohort studies and clinical trials demonstrates that dietary patterns significantly influence inflammatory status and clinical outcomes across diverse populations. Research utilizing data from the UK Biobank, the Nurses' Health Study, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study has established robust associations between pro-inflammatory diets and increased incidence of major brain disorders, reduced healthy aging, and worse survival outcomes in conditions such as stage III colon cancer [11] [12] [13]. Conversely, anti-inflammatory dietary patterns consistently associate with preserved cognitive function, physical capacity, mental health, and longevity [12]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on the mechanisms linking dietary components to inflammatory pathways and provides methodological guidance for research in nutritional immunology.

Quantitative Evidence: Dietary Patterns and Health Outcomes

Table 1: Association of Dietary Patterns with Health Outcomes from Recent Large-Scale Studies

| Health Outcome | Dietary Pattern/Index | Population | Effect Size (Highest vs. Lowest Adherence) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Aging | Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) | 105,015 US adults | OR: 1.86 (95% CI: 1.71-2.01) | [12] |

| Overall Survival in Stage III Colon Cancer | Anti-inflammatory vs. Pro-inflammatory Diet | 1,625 patients | 87% higher risk of death with pro-inflammatory diet | [13] [14] |

| Dementia Risk | MIND Diet | 166,916 UK Biobank participants | HR: 0.87 (95% CI: 0.77-0.98) | [11] |

| Depression Risk | MIND Diet | 166,916 UK Biobank participants | HR: 0.77 (95% CI: 0.71-0.82) | [11] |

| Physical Component of HRQOL | Anti-inflammatory Diet | 3,294 adults with chronic disease | SMD: 0.17 (95% CI: 0.06-0.27) | [15] |

| Combined Diet and Exercise on Survival | Anti-inflammatory Diet + High Physical Activity | Stage III colon cancer patients | 63% lower risk of death | [13] [16] |

Table 2: Inflammatory Biomarkers and Their Association with Dietary Patterns

| Biomarker | Dietary Assessment | Association | Study Population | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Blood Cell (WBC) Count | HEI-2015 (per unit increase) | Inverse association | 19,110 NHANES participants | [10] |

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) | DII (pro-inflammatory diet) | Positive association | 19,110 NHANES participants | [10] |

| High-sensitivity CRP | eADI-17 (per 4.5-point increase) | 12% lower concentration | 4,432 Swedish men | [17] |

| IL-6 | eADI-17 (per 4.5-point increase) | 6% lower concentration | 4,432 Swedish men | [17] |

| TNF-R1 | eADI-17 (per 4.5-point increase) | 8% lower concentration | 4,432 Swedish men | [17] |

| Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) | HEI-2015 vs. DII | HEI-2015: inverse; DII: positive | 19,110 NHANES participants | [10] |

Methodological Approaches for Dietary Inflammation Research

Major Dietary Indices and Their Applications

Nutritional epidemiology employs several validated indices to quantify the inflammatory potential of diets:

Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern (EDIP): Calculated as a weighted sum of 18 food groups (9 pro-inflammatory and 9 anti-inflammatory). Pro-inflammatory foods include red meat, processed meats, refined grains, and sugary drinks, while anti-inflammatory foods include coffee, tea, dark yellow vegetables, and leafy greens [13] [14]. EDIP has been validated against inflammatory biomarkers including IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2, and hsCRP [17].

Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII): Developed based on literature and population data, the DII quantitatively assesses the pro- and anti-inflammatory potential of food intake using 45 food parameters scored according to their effects on six inflammatory markers (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP) [10] [18]. A DII score > 0 indicates a pro-inflammatory diet, while < 0 indicates an anti-inflammatory diet.

Empirical Anti-inflammatory Diet Index (eADI): A recently developed index based on multiple inflammatory biomarkers (hsCRP, IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2). The eADI-17 includes 17 food groups (11 with anti-inflammatory potential, 6 with pro-inflammatory potential) with clear scoring criteria (tertiles of consumption corresponding to 0, 0.5, and 1 point) [17].

Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015): Assesses overall diet quality through 13 components (9 adequacy, 4 moderation) with scores from 0-100. Higher scores indicate better diet quality and are inversely associated with inflammatory markers [10].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Diet-Inflammation Relationships

Protocol 1: Development and Validation of Empirical Dietary Indices

Based on the methodology described by [17] for developing the eADI-17:

Study Population: Recruit a sufficiently large cohort (e.g., n > 4,000) with diverse dietary habits. Exclude participants with acute inflammatory conditions (e.g., hsCRP > 20 mg/L) or implausible energy intake reports.

Dietary Assessment: Administer a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with comprehensive food items (≥ 145 items). The FFQ should capture frequency of consumption using predefined categories (never/seldom to ≥ 3 times per day).

Biomarker Measurement: Collect fasting blood samples and analyze multiple inflammatory biomarkers including hsCRP (using high-sensitivity immunonephelometric assays), IL-6, TNF-R1, and TNF-R2 (using proteomic panels such as Olink Proteomics).

Statistical Analysis:

- Randomly split the cohort into Discovery and Replication groups.

- In the Discovery group, apply feature selection methods (e.g., 10-fold Lasso regression) to identify food groups most correlated with inflammatory biomarkers.

- Construct the dietary index by summing scores of selected food groups (tertiles of consumption: 0, 0.5, 1 point).

- Validate in the Replication group using multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to examine associations between the dietary index and inflammatory biomarkers.

Protocol 2: Assessing Diet-Cancer Survival Relationships

Based on the CALGB/SWOG 80702 trial analysis [13] [14]:

Study Population: Enroll patients with confirmed stage III colon cancer after surgical resection. Record demographic and clinical characteristics (age, sex, ECOG performance status, cancer stage).

Dietary Assessment: Administer food frequency questionnaires at baseline (e.g., 6 weeks post-randomization) and at follow-up intervals (e.g., 14-16 months). Calculate EDIP scores based on 18 food groups.

Physical Activity Assessment: Collect data on exercise habits using validated questionnaires. Categorize activity levels (e.g., high activity: ≥ 9 MET hours/week equivalent to walking at 2-3 mph for 1 hour approximately 3 times/week).

Outcome Measures: Track overall survival and disease-free survival over extended follow-up (multiple years). Use Cox proportional hazards models to assess associations between dietary patterns and survival, adjusting for potential confounders.

Additional Analyses: Investigate effect modification by anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., celecoxib), although the CALGB/SWOG 80702 trial found no significant influence of celecoxib on the diet-survival relationship [16].

Mechanistic Pathways Linking Diet to Inflammation

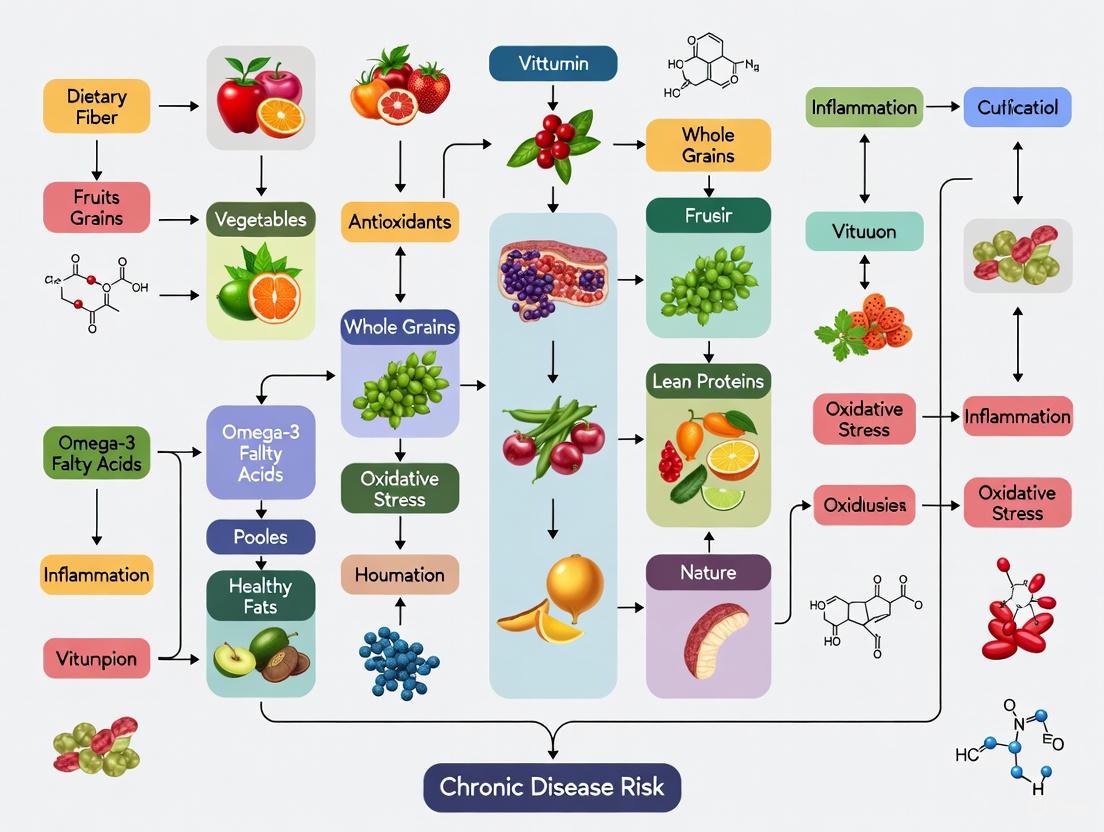

Diagram 1: Mechanistic Pathways of Dietary Inflammation. This diagram illustrates the proposed biological pathways through which pro- and anti-inflammatory dietary components influence systemic inflammation and chronic disease risk, incorporating findings from multi-omics analyses [11].

Multi-Omics Insights into Dietary Inflammation

Recent multi-omics analyses have elucidated specific biological pathways mediating the relationship between diet and inflammation:

Metabolic Signature Mediation: A favorable metabolic signature explains substantial proportions of reduced risk for stroke (60.63%), depression (38.97%), and anxiety (26.06%) associated with the MIND diet [11]. These metabolites likely include gut microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acids from fiber fermentation, as well as polyphenol metabolites with anti-inflammatory properties.

Biological Aging Pathways: Slower biological aging significantly mediates the reduced risk of dementia (19.40%) associated with anti-inflammatory dietary patterns [11]. This suggests that anti-inflammatory diets may attenuate epigenetic aging processes and cellular senescence, potentially through reducing oxidative stress and DNA damage.

Proteomic Alterations: Anti-inflammatory diets associate with favorable profiles of inflammation-related proteins including adipokines, acute-phase proteins, and inflammatory cytokines that collectively reduce systemic inflammation [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Inflammation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Specifications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assess habitual dietary intake | 145+ food items; validated against dietary recalls | [17] |

| Olink Proteomics Panels | Quantify inflammatory proteins | CVD II/III panels; measure IL-6, TNF-R1, TNF-R2 | [17] |

| High-Sensitivity CRP Assay | Measure chronic inflammation | Latex-enhanced immunonephelometric assay; detection limit <0.1 mg/L | [17] |

| Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) Calculator | Quantify dietary inflammatory potential | 45 food parameters; scores based on effects on 6 inflammatory markers | [10] [18] |

| EDIP Calculation Algorithm | Classify pro-/anti-inflammatory diets | 18 food groups with weighted scores | [13] [14] |

| Metabolomics Profiling Platforms | Identify metabolic signatures of diet | LC-MS/MS; covers ~1,000+ metabolites | [11] |

| Epigenetic Aging Clocks | Assess biological aging | DNA methylation arrays; measures Phenotypic Age Acceleration | [11] |

The evidence synthesized in this whitepaper demonstrates that dietary patterns significantly influence inflammatory pathways through multiple biological mechanisms, with consequential effects on chronic disease risk and progression. Anti-inflammatory dietary patterns, characterized by abundant fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, and healthy fats, consistently associate with reduced inflammatory biomarkers, better health-related quality of life, improved survival in conditions such as colon cancer, and enhanced healthy aging trajectories.

Future research should prioritize several key areas: (1) elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms through which dietary components influence inflammatory signaling using multi-omics approaches; (2) conducting randomized controlled trials to establish causal relationships between dietary interventions and inflammatory outcomes in diverse populations; (3) developing personalized anti-inflammatory dietary recommendations based on genetic, metabolic, and microbiome profiles; and (4) investigating the synergistic effects of diet and pharmacological anti-inflammatory agents on disease outcomes. As dietary inflammation research advances, it holds significant promise for developing targeted nutritional strategies to mitigate the global burden of chronic inflammatory diseases.

The progressive functional decline characteristic of biological ageing is the primary risk factor for most chronic, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [19]. Within geroscience, the objective has shifted from merely extending lifespan to maximising healthspan—the period of life spent in good physical, cognitive, and mental health [19]. Among various modifiable factors, nutrition emerges as a potent modulator of the rate of biological ageing and resilience against NCDs [19]. This whitepaper explores the pivotal role of metabolic signatures as biomarkers of ageing and examines how dietary patterns influence these signatures to modulate biological ageing trajectories and disease risk, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Metabolic Signatures as Biomarkers of Ageing

Defining Metabolic Signatures of Ageing

Metabolites, the small molecules produced by metabolic processes, serve as sensitive indicators of physiological state and can provide a real-time snapshot of biological age. Research from the Long Life Family Study (LLFS) analysed 408 plasma metabolites and identified 308 metabolites associated with chronological age, 258 that change over time, 230 associated with extreme longevity, and 152 associated with mortality risk [20]. Network analysis revealed that essential fatty acids, particularly linoleic and gamma-linolenic acids, play a critical role in connecting lipid metabolism with other metabolic processes during ageing [20].

Muscle-Specific Metabolic Signatures in Ageing

Skeletal muscle metabolomics offers unique insights into ageing processes. A non-targeted metabolomics study on murine gastrocnemius muscle identified 50 metabolites that consistently distinguish healthy from unhealthy ageing trajectories, termed the 'Advanced Age Muscle-Enriched Metabolite Set' (AAMEMS) [21]. This signature includes 18 metabolites commonly reduced under unhealthy ageing (e.g., arginine, lysine) and 32 metabolites increased (including various ceramides and short-chain acylcarnitines) [21]. The most significant associations were found with oxidative stress and nutrient sensing pathways, highlighting their central role in musculoskeletal ageing [21].

Table 1: Key Metabolite Classes in Ageing and Their Associations

| Metabolite Class | Association with Unhealthy Ageing | Primary Ageing Hallmarks Involved | Potential Dietary Modulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-chain Acylcarnitines | Decreased [21] | Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress | Carnitine, Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

| Arginine & Lysine | Decreased [21] | Deregulated Nutrient Sensing, Stem Cell Dysfunction | High-Quality Protein, Plant-Based Diets |

| Ceramides | Increased [21] | Chronic Inflammation, Oxidative Stress | Low Saturated Fat, High Fiber |

| Short-chain Acylcarnitines | Increased [21] | Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Caloric Restriction, Exercise |

| Essential Fatty Acids | Altered Profiles [20] | Chronic Inflammation, Genomic Instability | Omega-3 Rich Foods, Mediterranean Diet |

Dietary Modulation of Metabolic Signatures

Neuroprotective Dietary Patterns

Large-scale prospective cohort studies have comprehensively compared dietary patterns for brain health. A study using UK Biobank data (N=166,916) evaluated ten dietary patterns and found the MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet demonstrated the broadest neuroprotective effects [22]. Over a median follow-up of 10.5 years, adherence to the MIND diet was significantly associated with reduced risk of dementia (HR=0.87), stroke (HR=0.89), depression (HR=0.77), and anxiety (HR=0.82), but not Parkinson's disease (HR=0.94) [22]. These findings were validated in the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (n=4,496) and the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (n=9,099) [22].

Multi-Omics Mediation of Dietary Effects

The protective mechanisms of the MIND diet were elucidated through multi-omics analyses, revealing that:

- A favourable metabolic signature mediated 60.63% of the reduced stroke risk, 38.97% of reduced depression risk, and 26.06% of reduced anxiety risk [22].

- Slower biological ageing significantly mediated 19.40% of the reduced dementia risk [22].

- Structural equation modeling confirmed the overall protective pathway linking the MIND diet to better brain health via these mediators [22].

Conversely, ultra-processed food (UPF) intake was associated with increased risk for dementia (HR=1.40), Parkinson's disease (HR=1.26), depression (HR=1.42), and anxiety (HR=1.26) through detrimental changes in these same metabolic and ageing pathways [22].

Table 2: Association of Dietary Patterns with Healthy Ageing Odds (from Prospective Cohorts)

| Dietary Pattern | Acronym | Odds Ratio for Healthy Ageing | Primary Health Domains Benefitted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index | AHEI | ~2.00 (Strongest Association) [19] | Cognitive, Physical, and Mental Function |

| Mediterranean Diet | aMED | Increased [19] | Cognitive Function, Cardiovascular Health |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension | DASH | Increased [19] | Cardiovascular Health, Metabolic Function |

| Planetary Health Diet Index | PHDI | Increased [19] | Systemic Health, Environmental Sustainability |

| MIND Diet | MIND | Significant Risk Reduction for Dementia, Stroke, Depression, Anxiety [22] | Brain Health, Neuropsychiatric Disorders |

Methodologies for Assessing Metabolic Signatures in Aging Research

Experimental Workflow for Muscle Metabolomics

The following diagram outlines a standardised workflow for skeletal muscle metabolomics in ageing studies:

Computational Analysis of Microbiome-Metabolite Interactions

The STELLA algorithm provides a computational framework for deriving metabolite spectra from microbiome data [23]:

- Input: 16S rRNA sequencing data from fecal samples.

- Pathway Mapping: Uses MACADAM and METACYC databases to retrieve metabolic pathways for each operational taxonomic unit (OTU).

- Stoichiometric Modeling: Considers reaction stoichiometry and directionality to assign production/consumption scores.

- Abundance Weighting: Weights pathway contributions according to OTU abundance.

- Output: Estimated metabolite concentrations for each patient.

Validation against experimental metabolomic data from autism spectrum disorder studies showed strong predictive accuracy (F₁ score=0.67) [23]. Batch effect removal via singular value decomposition is critical when merging datasets from different sources [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ageing Metabolomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use in Ageing Research |

|---|---|---|

| UPLC-MS/MS Systems | High-resolution metabolite separation and quantification | Non-targeted metabolomics on skeletal muscle; quantification of 427 metabolites in murine studies [21] |

| Epigenetic Clock Panels | DNA methylation-based biological age estimation | Tracking intervention efficacy; distinguishing chronological vs. biological age (e.g., Horvath, GrimAge clocks) [19] |

| MACADAM & METACYC Databases | Metabolic pathway curation and stoichiometric modeling | Predicting microbiome-derived metabolites using computational approaches like STELLA [23] |

| Cohort Biobanks | Large-scale human biological samples with multi-omics data | Validation of metabolic signatures (e.g., UK Biobank, Long Life Family Study) [22] [20] |

| Standardized Dietary Indices | Quantifying adherence to neuroprotective diets | Assessing MIND, AHEI, DASH, and other dietary patterns in cohort studies [19] [22] |

Metabolic signatures provide a powerful lens through which to quantify biological ageing and evaluate the efficacy of nutritional interventions. The integration of metabolomic data with other omics technologies reveals the mechanistic pathways through which dietary patterns like the MIND diet exert their neuroprotective effects, largely by modulating specific metabolic pathways and slowing the pace of biological ageing. Future research should focus on standardising metabolite nomenclature, incorporating longitudinal dietary data, and translating these findings into targeted nutritional therapeutics for promoting healthspan and mitigating age-related disease risk.

The gut-brain axis (GBA) represents a complex, bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract with the central nervous system, with profound implications for neurological health and cognitive function. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on dietary modulation of the GBA, examining mechanisms through which nutritional patterns influence neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal signaling. Drawing from recent clinical studies and emerging molecular research, we analyze how specific dietary components and patterns affect gut microbiota composition, microbial metabolite production, and subsequent brain health outcomes. The therapeutic potential of microbiota-targeted nutritional interventions for cognitive disorders, mental health conditions, and neurodegenerative diseases is examined, with specific consideration for research methodologies and biomarker assessment. This analysis provides a framework for integrating nutritional strategies into neurological drug development and precision medicine approaches for brain disorders.

The gut-brain axis comprises an extensive communication network facilitating constant interaction between the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system through multiple parallel pathways including neural, endocrine, immune, and metabolic signaling routes [24]. This bidirectional system integrates brain and gut functions, with the gut microbiota—a diverse ecosystem of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract—serving as a critical modulator of this interface [25]. The conceptualization of the GBA has evolved beyond simple brain-gut communication to recognize the microbiota as a key regulator of this system, often described as the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

The significance of the GBA extends to numerous neurological and psychiatric conditions. Research indicates that imbalances in gut microbial communities (dysbiosis) can disrupt GBA signaling, potentially contributing to inflammation and neurotransmitter disturbances implicated in depression, anxiety, and cognitive disorders [24]. The gut microbiota influences brain function through multiple mechanisms: production of neurotransmitters and neuroactive metabolites; regulation of immune responses; modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis; and maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity [25]. The vagus nerve, a primary neural pathway between the gut and brain, facilitates direct communication that can modulate brain activity and behaviors associated with anxiety and mood [24].

Diet represents one of the most potent modulators of the gut microbiota composition and function, thereby serving as a primary intervention point for influencing the GBA [25]. Nutritional neuroscience has emerged as a discipline focused on understanding how dietary components and patterns influence brain function and mental health through their effects on the GBA [26]. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms underlying dietary influences on the GBA and their implications for cognitive function and mental health within the broader context of chronic disease risk mechanisms.

Molecular Mechanisms of Gut-Brain Communication

Neural and Endocrine Pathways

The GBA utilizes multiple sophisticated communication channels to maintain gut-brain homeostasis. The vagus nerve serves as a direct neural pathway, transmitting gut-derived signals to brain regions involved in emotion regulation, stress response, and cognition [24]. Gut microbes and their metabolites can activate vagal afferents through enteroendocrine cells, influencing central neurotransmitter systems. This neural pathway represents the most direct route for gut-brain signaling.

The endocrine system facilitates GBA communication through the HPA axis, the body's primary stress response system. The gut microbiota regulates HPA axis development and function, with dysbiosis potentially leading to HPA axis dysregulation and increased susceptibility to stress-related disorders [24]. Gut microbes influence circulating levels of cortisol and other stress hormones, which in turn can modulate gut permeability and microbial composition, creating a feedback loop.

The immune system provides another crucial communication channel, with gut microbes continuously interacting with intestinal immune cells. This interaction regulates systemic levels of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines that can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and influence neuroinflammation [24]. Dysbiosis can trigger immune activation, leading to increased circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines that compromise BBB integrity and promote neuroinflammation associated with various neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Microbial Metabolites and Signaling Molecules

Gut microbiota produce numerous neuroactive compounds that significantly influence brain function:

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): including butyrate, acetate, and propionate, are produced through microbial fermentation of dietary fiber. SCFAs strengthen the intestinal barrier, reduce systemic inflammation, and can cross the BBB to influence microglia function and neuroinflammation [24]. Butyrate particularly demonstrates histone deacetylase inhibitor activity, influencing gene expression in neural cells.

- Neurotransmitters: Gut bacteria synthesize numerous neurotransmitters including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine [26]. Notably, approximately 90% of the body's serotonin is synthesized in the gut under microbial influence [24].

- Tryptophan metabolites: As the precursor to serotonin, tryptophan metabolism is heavily influenced by gut microbiota through the kynurenine and serotonin pathways, with implications for serotonin availability in the brain [24].

- Bile acids: Microbial-modified bile acids function as signaling molecules that can influence host metabolism and neuroinflammation through activation of nuclear receptors.

Table 1: Key Microbial Metabolites in Gut-Brain Signaling

| Metabolite | Primary Producers | Neurological Effects | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (Butyrate, Acetate, Propionate) | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia, Eubacterium, Bifidobacterium | Reduce neuroinflammation, strengthen blood-brain barrier, support microglia function, influence epigenetic regulation | Potential therapeutic for neurodegenerative diseases; biomarker for fiber fermentation |

| GABA (Gamma-aminobutyric acid) | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Primary inhibitory neurotransmitter; regulates anxiety, stress response, sleep | Psychobiotic development for anxiety disorders |

| Serotonin | Enterochromaffin cells (microbiota-regulated) | Mood regulation, appetite, sleep, cognitive functions | Understanding SSRIs microbiota interactions; depression therapeutics |

| Secondary bile acids | Bacteroides, Clostridium, Lactobacillus | FXR and TGR5 receptor activation; neuroinflammation modulation | Metabolic disorder-neurodegeneration link |

Figure 1: Gut-Brain Axis Communication Pathways. This diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms through which dietary components influence brain function via the gut microbiota and multiple signaling pathways.

Barrier Systems and Their Regulation

The GBA involves critical barrier systems that regulate molecule passage between compartments:

- Intestinal barrier: A single layer of epithelial cells with tight junctions that selectively permits nutrient absorption while restricting pathogen translocation. Gut microbes and their metabolites, particularly SCFAs, regulate intestinal barrier integrity. Dysbiosis can increase intestinal permeability ("leaky gut"), allowing bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to enter circulation and trigger systemic inflammation [24].

- Blood-brain barrier: A specialized endothelial structure that protects the brain from circulating toxins and pathogens. Systemic inflammation resulting from gut dysbiosis can compromise BBB integrity, permitting entry of pro-inflammatory molecules and immune cells into the brain [24]. SCFAs have been shown to support BBB function through effects on tight junction proteins.

These barrier systems represent critical intervention points for dietary influences on the GBA, with specific nutritional components demonstrating protective effects on both intestinal and BBB integrity.

Dietary Patterns and Their Impact on Gut-Brain Signaling

Mediterranean and MIND Diets

The Mediterranean diet (MeDi) is characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and olive oil; moderate intake of fish and poultry; and low consumption of red meat and processed foods. This dietary pattern has demonstrated significant neuroprotective effects across multiple studies [27]. Research indicates that MeDi adherence is associated with a 30-40% reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease and improved cognitive function [28]. The protective mechanisms include enhanced microbial diversity, increased SCFA production, reduced neuroinflammation, and attenuation of oxidative stress.

The MIND diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) specifically targets brain health, emphasizing green leafy vegetables, berries, nuts, whole grains, and limited intake of saturated fats and processed foods [28]. A recent 5-year prospective cohort study comparing both diets found that higher adherence to either diet was associated with significantly better cognitive scores (p < 0.0001), lower amyloid-beta, tau, and neurofilament light chain (NfL) levels, and reduced inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6, TNF-α) [28]. The MIND diet demonstrated a slightly stronger association with cognitive protection than the Mediterranean diet.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Mediterranean vs. MIND Diet Adherence (5-Year Study)

| Biomarker/Cognitive Measure | Mediterranean Diet High Adherence | MIND Diet High Adherence | Low Adherence (Control) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE Score Change | -0.8 ± 0.3 points | -0.5 ± 0.2 points | -2.9 ± 0.5 points | < 0.0001 |

| MoCA Score Change | -1.1 ± 0.4 points | -0.7 ± 0.3 points | -3.5 ± 0.6 points | < 0.0001 |

| Amyloid-β (Aβ42/40) | 325 ± 45 pg/mL | 355 ± 38 pg/mL | 215 ± 52 pg/mL | < 0.0001 |

| Tau Protein | 85 ± 12 pg/mL | 78 ± 10 pg/mL | 125 ± 18 pg/mL | < 0.0001 |

| Neurofilament Light Chain | 28 ± 6 pg/mL | 25 ± 5 pg/mL | 42 ± 8 pg/mL | < 0.0001 |

| C-reactive Protein | 2.1 ± 0.5 mg/L | 1.8 ± 0.4 mg/L | 4.5 ± 0.9 mg/L | < 0.0001 |

Plant-Based and High-Fiber Diets

Plant-based diets rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains promote microbial diversity and SCFA production through several mechanisms:

- Dietary fiber serves as a primary substrate for microbial fermentation, leading to SCFA production. High-fiber diets increase the abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria including Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Roseburia species [24]. These microbial shifts correlate with improved cognitive performance and reduced neuroinflammation.

- Polyphenols from plant foods exhibit prebiotic-like effects, promoting beneficial bacteria while inhibiting potential pathogens [25]. Regular consumption of polyphenol-rich foods (berries, green tea, dark chocolate, olive oil) is associated with enhanced cognitive function, potentially through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

- Plant-based proteins from legumes and nuts support beneficial microbes compared to animal proteins, which may promote bile-tolerant bacteria associated with inflammation [24].

Intervention studies demonstrate that shifts toward plant-based dietary patterns can induce measurable changes in microbial composition within weeks, with corresponding improvements in cognitive parameters, particularly in executive function and memory domains [27].

Western and High-Fat Diets

In contrast to plant-rich diets, Western dietary patterns characterized by high consumption of processed foods, saturated fats, refined sugars, and low fiber content have consistently demonstrated negative effects on gut-brain signaling:

- Reduced microbial diversity: Western diets decrease overall microbial richness and diversity, potentially leading to the extinction of beneficial microbes [25]. This diversity loss reduces functional redundancy and ecosystem resilience.

- Increased intestinal permeability: High-fat and high-sugar diets can disrupt tight junction proteins, increasing LPS translocation and systemic inflammation [24].

- Altered microbial metabolism: Western diets shift microbial metabolism toward production of potentially harmful metabolites including trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), associated with cardiovascular and neurological risks [24].

- Neuroinflammation: Diet-induced systemic inflammation promotes microglial activation and neuroinflammation, potentially accelerating neurodegenerative processes [29].

The detrimental effects of Western diets on the GBA provide a mechanistic explanation for epidemiological associations between these dietary patterns and increased risk of depression, cognitive decline, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Experimental Models and Research Methodologies

Human Study Designs and Biomarker Assessment

Research investigating diet-GBA-brain interactions employs multiple methodological approaches:

Clinical Trial Designs:

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs): The gold standard for establishing causal relationships between dietary interventions and neurological outcomes. Recent RCTs have implemented dietary interventions ranging from 8 weeks to 24 months with detailed assessment of microbiota composition, microbial metabolites, inflammatory markers, and cognitive measures [28].

- Cohort studies: Large prospective cohorts (e.g., 5-year study with 1500 participants) provide longitudinal data on dietary patterns, microbiome changes, and cognitive trajectories [28].

- Cross-over studies: Particularly valuable for nutritional interventions due to ability to control for inter-individual variability.

Biomarker Assessment:

- Microbiome analysis: 16S rRNA sequencing for taxonomic classification; shotgun metagenomics for functional potential; metabolomics for microbial metabolite profiling.

- Inflammatory markers: CRP, IL-6, TNF-α measured in blood and sometimes CSF [28].

- Neurodegeneration biomarkers: Amyloid-β, tau, neurofilament light chain (NfL) in blood and CSF [28].

- Cognitive assessment: Standardized instruments including MMSE, MoCA, and specialized neuropsychological batteries.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Dietary Intervention Studies. This diagram outlines the standard methodology for clinical trials investigating diet-gut-brain interactions, from participant screening through multi-omics analysis.

Animal Models and Mechanistic Studies

Animal models provide critical insights into causal mechanisms underlying diet-GBA interactions:

- Germ-free models: Animals raised without microorganisms enable investigation of microbiota necessity for normal brain development and function.

- Microbiota transplantation: Fecal microbiota transplantation from human donors to germ-free animals allows demonstration of causal relationships between microbial communities and behavioral phenotypes.

- Genetic models: Transgenic models of neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's, Parkinson's) permit investigation of dietary interventions on disease progression.

- Pharmacological interventions: Receptor antagonists, enzyme inhibitors, and other pharmacological tools help elucidate molecular mechanisms.

Standardized behavioral tests in animal models include forced swim test (depression-like behavior), open field test (anxiety-like behavior), Morris water maze (spatial learning and memory), and novel object recognition (recognition memory).

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gut-Brain Axis Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro, DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil | Microbiome profiling, 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics | Standardization critical for cross-study comparisons; controls for contamination |

| 16S rRNA Primers | 515F/806R (V4 region), 27F/338R (V1-V2) | Bacterial identification and relative abundance | Primer selection influences taxonomic resolution; validation with mock communities |

| ELISA Kits | Amyloid-β (Thermo Fisher KHB3481), Tau (R&D Systems DTA00), NfL (Peninsula Laboratories 42-1001) | Quantification of neurodegeneration biomarkers in blood/CSF | Consider sensitivity (pg/mL range) and dynamic range; batch variation controls |

| Cytokine Panels | Multiplex assays for CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β | Inflammation monitoring in serum, plasma, CSF | High-sensitivity assays required for subtle inflammatory changes |

| SCFA Analysis | GC-MS, LC-MS platforms | Quantification of microbial metabolites (butyrate, acetate, propionate) | Sample collection critical (immediate freezing); internal standards required |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2 (intestinal barrier), SH-SY5Y (neuronal), BV-2 (microglial) | Mechanistic studies of barrier function, neuroinflammation | Limitations in representing complex in vivo microenvironment |

| Gnotobiotic Equipment | Isolators, sterile housing | Research with germ-free, defined microbiota animals | Technical expertise required; contamination monitoring essential |

Analytical Platforms and Omics Technologies

Advanced analytical platforms enable comprehensive investigation of diet-GBA interactions:

- Metagenomic sequencing: Shotgun sequencing provides strain-level taxonomic resolution and functional gene annotation, enabling reconstruction of microbial metabolic pathways.

- Metabolomics: Mass spectrometry-based platforms (GC-MS, LC-MS) quantify microbial metabolites (SCFAs, neurotransmitters, bile acids) in feces, blood, and sometimes CSF.

- Metatranscriptomics: RNA sequencing of microbial communities reveals functionally active metabolic pathways responding to dietary interventions.

- Proteomics: Mass spectrometry-based quantification of host and microbial proteins in various biofluids.

- Multi-omics integration: Computational approaches integrating data from multiple platforms to construct comprehensive models of diet-microbiota-host interactions.

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

Nutritional Interventions for Cognitive Disorders

Dietary approaches show promise for preventing and managing cognitive decline:

- MIND and Mediterranean diets: Long-term adherence associates with slower cognitive decline and reduced Alzheimer's disease pathology [28]. The 5-year prospective study demonstrated that both diets significantly preserved cognitive function, with the MIND diet showing marginally superior effects [28].

- Ketogenic diets: Very low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets may benefit neurological conditions by providing alternative energy substrates, reducing oxidative stress, and modulating gut microbiota [30].

- Polyphenol supplementation: Interventions with specific polyphenol-rich foods (berries, green tea, cocoa) demonstrate improvements in memory, executive function, and neuroplasticity markers [27].

- Omega-3 fatty acids: DHA and EPA supplementation shows particular benefit in individuals with low baseline levels, reducing neuroinflammation and supporting neuronal membrane integrity [31].

Psychobiotics and Microbial Therapeutics

Psychobiotics—probiotics and prebiotics with mental health benefits—represent a promising therapeutic approach:

- Probiotic strains: Specific strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium demonstrate anti-anxiety and antidepressant effects in clinical trials, potentially through GABA production, HPA axis modulation, and inflammation reduction [24].

- Prebiotics: Non-digestible fibers (FOS, GOS, resistant starch) selectively promote beneficial bacteria, indirectly influencing brain function through SCFA production and immune modulation [25].

- Synbiotics: Combinations of probiotics and prebiotics designed to work synergistically.

- Postbiotics: Bacterial-derived products including SCFAs, cell wall fragments, and other bioactive molecules.

Clinical translation requires consideration of individual factors including baseline microbiota composition, host genetics, diet, and environmental exposures. Personalized nutrition approaches that account for these variables may enhance therapeutic efficacy.

The gut-brain axis represents a fundamental pathway through which diet influences neurological health and cognitive function. Evidence from mechanistic studies, animal models, and human interventions consistently demonstrates that dietary patterns significantly modulate gut microbiota composition and function, with consequent effects on neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter systems, and neuronal integrity. Mediterranean and MIND diets, rich in plant foods, fiber, and polyphenols, promote microbial diversity and SCFA production, correlating with improved cognitive outcomes and reduced neurodegeneration biomarkers.

Future research priorities include:

- Long-term intervention studies: Extending beyond 2 years to establish durable effects of dietary patterns on cognitive trajectories.

- Personalized nutrition approaches: Integrating multi-omics data with clinical phenotypes to predict individual responses to dietary interventions.

- Mechanistic elucidation: Further delineation of molecular pathways linking specific microbial metabolites to brain function.

- Intervention timing: Determining critical periods for dietary interventions across the lifespan.

- Microbiome-targeted therapeutics: Developing novel psychobiotics, prebiotics, and microbial metabolites as adjunctive therapies for neurological and psychiatric conditions.

The integration of nutritional strategies with neurological drug development holds promise for enhancing therapeutic outcomes in brain disorders. As research methodologies advance and our understanding of diet-GBA interactions deepens, targeted nutritional interventions may become established components of comprehensive approaches to brain health maintenance and neurological disease treatment.

Research Methods and Translational Applications in Nutrition Science

Prospective cohort studies represent the gold standard research design in observational nutritional epidemiology for investigating the complex relationships between long-term dietary patterns and chronic disease risk. These studies collect extensive data on a large group of healthy individuals and follow them forward in time to observe how exposures, such as dietary habits, correlate with the subsequent development of diseases. The Nurses' Health Study (NHS), Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), and UK Biobank exemplify this methodology, having generated pivotal evidence that informs our understanding of diet-disease relationships through their massive scale, long-term follow-up, and comprehensive data collection protocols [32] [12].

The fundamental strength of these designs lies in their ability to establish temporal sequence—dietary exposure is assessed before disease onset, minimizing recall bias that plagues case-control studies. When conducted with rigorous methodology, including repeated dietary assessments, validation substudies, and careful control for confounding variables, these studies can provide compelling evidence about the role of diet in chronic disease development. Their large sample sizes enable sufficient statistical power to detect modest associations and examine effect modification across population subgroups, while their prospective nature allows for the investigation of multiple disease outcomes simultaneously from the same baseline data [32] [33].

Key Findings: Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Risk

Large-scale prospective cohorts have consistently demonstrated that specific dietary patterns significantly influence the risk of major chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and overall mortality. The evidence from these studies has evolved from focusing on single nutrients to comprehensive dietary patterns that better reflect how people actually eat and the potential synergistic effects of foods.

Dietary Patterns and Cancer Risk

The association between dietary patterns and cancer risk has been extensively investigated in prospective cohorts. Evidence from the REGARDS cohort, which followed 22,041 participants over a 10-year observation period, identified significant associations between dietary patterns and cancer mortality [34]. The study derived five empirical dietary patterns through factor analysis: Convenience (Chinese and Mexican foods, pasta, pizza), Plant-based (fruits, vegetables), Southern (added fats, fried foods, sugar-sweetened beverages), Sweets/Fats (sugary foods), and Alcohol/Salads (alcohol, green-leafy vegetables, salad dressing) [34].

Greater adherence to the Southern dietary pattern was associated with a 67% increased risk of cancer mortality (HR: 1.67; 95% CI: 1.32–2.10) compared to those with lowest adherence [34]. This pattern was especially detrimental among White participants (HR: 1.59; 95% CI: 1.22–2.08). Conversely, the Convenience (HR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.56–0.94) and Plant-based (HR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.55–0.93) dietary patterns were associated with approximately 28% reduced risk of cancer mortality, though these protective associations were observed primarily among White participants [34].

A recent umbrella review of meta-analyses including 74 meta-analyses from 30 articles evaluated the strength of evidence linking dietary patterns to cancer risk [35]. The analysis identified convincing evidence that adherence to the 2007 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) dietary recommendations was associated with lower risk of all cancers (RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.92, 0.95 per 1-unit score increase) [35]. Similarly, prudent diets (RR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.85, 0.93) and vegetable-fruit-soybean diets (RR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.83, 0.92) demonstrated convincing evidence for breast cancer risk reduction [35].

The Million Women Study, encompassing 542,778 UK women with 12,251 incident colorectal cancer cases over 16.6 years, provided particularly insightful diet-wide association analyses [36]. Alcohol consumption demonstrated the strongest positive association with colorectal cancer risk (RR per 20 g/day = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.09–1.20), while calcium intake showed the strongest inverse association (RR per 300 mg/day = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.77–0.89) [36]. Red and processed meat intake was positively associated with colorectal cancer risk (RR per 30 g/day = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.03–1.12), though this association was weaker than those observed for alcohol and calcium [36].

Dietary Patterns and Healthy Aging

Recent evidence from the NHS and HPFS, with up to 30 years of follow-up, has examined dietary patterns in relation to healthy aging, defined as surviving to 70 years free of major chronic diseases and maintaining intact cognitive, physical, and mental health [12]. Among 105,015 participants, only 9,771 (9.3%) achieved healthy aging, highlighting the importance of identifying modifiable factors like diet that promote healthspan [12].

The study examined eight dietary patterns, finding that higher adherence to all patterns was associated with greater odds of healthy aging, with odds ratios comparing the highest to lowest quintiles ranging from 1.45 (95% CI: 1.35–1.57) for the healthful plant-based diet index to 1.86 (95% CI: 1.71–2.01) for the Alternative Healthy Eating Index [12]. When the healthy aging threshold was shifted to 75 years, the Alternative Healthy Eating Index showed an even stronger association (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 2.01–2.50) [12].

Specific dietary components demonstrated distinct relationships with healthy aging domains. Higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, unsaturated fats, nuts, legumes, and low-fat dairy were consistently associated with greater odds of healthy aging, whereas trans fats, sodium, sugary beverages, and red/processed meats were inversely associated [12]. Added unsaturated fat intake was particularly associated with surviving to age 70 years and maintaining intact physical and cognitive function [12].

Comparative Effectiveness of Dietary Patterns

Research directly comparing multiple dietary patterns within the same population provides valuable evidence for understanding their relative effectiveness for chronic disease prevention. A comprehensive analysis of 205,852 healthcare professionals from the NHS, NHS II, and HPFS followed for up to 32 years assessed two mechanism-based diets and six diets based on dietary recommendations in relation to major chronic disease—a composite outcome of incident major cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer [33].

The study demonstrated that participants with low insulinemic (HR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.57–0.60), low inflammatory (HR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.60–0.63), or diabetes risk-reducing diets (HR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.69–0.72) had the largest risk reduction for the composite endpoint [33]. These findings suggest that dietary patterns associated with markers of hyperinsulinemia and inflammation may be particularly informative for future dietary guidelines aimed at chronic disease prevention [33].

Table 1: Association Between Dietary Patterns and Chronic Disease Risk in Major Prospective Cohorts

| Dietary Pattern | Chronic Disease Outcome | Risk Estimate (Highest vs. Lowest Adherence) | Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index | Healthy Aging | OR: 1.86 (95% CI: 1.71–2.01) | NHS, HPFS [12] |

| Healthful Plant-Based Diet | Healthy Aging | OR: 1.45 (95% CI: 1.35–1.57) | NHS, HPFS [12] |

| Southern Pattern | Cancer Mortality | HR: 1.67 (95% CI: 1.32–2.10) | REGARDS [34] |

| Plant-Based Pattern | Cancer Mortality | HR: 0.72 (95% CI: 0.55–0.93) | REGARDS [34] |

| Low Insulinemic Diet | Major Chronic Disease* | HR: 0.58 (95% CI: 0.57–0.60) | NHS, HPFS, NHS II [33] |

| WCRF/AICR Recommendations | All Cancers | RR: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.92–0.95) per 1-unit | Umbrella Review [35] |

*Composite of incident major cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer

Methodological Protocols in Prospective Cohort Studies

Dietary Assessment Methods

Prospective cohort studies employ standardized, validated dietary assessment tools to capture habitual intake. The NHS and HPFS utilize semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) administered every 2-4 years to assess dietary intake over the preceding year [33] [12]. These FFQs typically include 130-150 food items with standard portion sizes and frequency categories ranging from "never or less than once per month" to "6+ times per day" [12]. The repeated measures allow for calculation of cumulative averages that better represent long-term dietary patterns and reduce measurement error.

The UK Biobank employs multiple assessment methods, including a touchscreen food frequency questionnaire at baseline and a web-based 24-hour dietary assessment tool (Oxford WebQ) for subsequent assessments [37]. The Oxford WebQ collects data on consumption of up to 206 types of foods and 32 types of drinks during the previous 24 hours, providing more detailed recent intake data [37]. This multi-method approach enhances the comprehensiveness of dietary exposure assessment.

Table 2: Dietary Assessment Methods in Major Prospective Cohorts

| Assessment Method | Frequency of Administration | Key Components | Validation Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Quantitative FFQ (NHS/HPFS) | Every 2-4 years | 130-150 food items, standard portion sizes, 9 frequency categories | Comparison with diet records and biomarkers [33] |

| Touchscreen FFQ (UK Biobank) | Baseline | Common food groups, intake frequencies | Comparison with 24-hour recalls [37] |

| Oxford WebQ 24-hour Recall (UK Biobank) | Multiple timepoints | 206 foods, 32 drinks, previous 24-hour intake | Comparison with biomarkers [37] |

| Block 98 FFQ (REGARDS) | Baseline | 110 food items, frequency and portion size | Comparison with 24-hour recalls [34] |

Outcome Ascertainment

Chronic disease outcomes are ascertained through multiple complementary methods to ensure completeness. In the NHS and HPFS, participants report diagnoses on biennial questionnaires, which are then confirmed through medical record review by physicians blinded to exposure status [12]. Mortality outcomes are identified through the National Death Index, state vital statistics records, and reports from family members [12]. Specific endpoints like cancer are confirmed through pathology reports, while cardiovascular events undergo additional review using standard criteria like the MONICA protocol.

The UK Biobank utilizes linkage to national health registries, including hospital episode statistics, cancer registries, and death registries, providing comprehensive capture of disease endpoints [37] [36]. This linkage approach minimizes loss to follow-up and enables complete ascertainment of hard endpoints. The REGARDS cohort employs semi-annual telephone follow-up, proxy reports, and linkages with the Social Security Death Index and National Death Index, with cause of death adjudicated by expert committees [34].

Statistical Analysis Approaches

Prospective cohort studies employ sophisticated statistical methods to account for potential confounding and test the robustness of associations. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models are standard for analyzing time-to-event data, with careful adjustment for known confounders including age, sex, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, and total energy intake [33] [34] [12]. Additional adjustments are made for socioeconomic factors, family history of diseases, and menopausal status (in women-specific analyses).

More advanced methods include:

- High-dimensional Fixed Effects (HDFE) models: Used in UK Biobank analyses to control for numerous occupational, regional, and ethnicity-related fixed effects that might confound diet-disease relationships [37].

- Mendelian Randomization: Employed to strengthen causal inference using genetic variants as instrumental variables for dietary exposures [37] [36].

- Factor and Cluster Analysis: Used to derive empirical dietary patterns from the dietary data itself, as seen in the REGARDS cohort analysis [34].

- Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort models: Implemented for projecting future disease burden based on current trends [38].

Research Workflow in Prospective Cohort Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Prospective Diet-Disease Research

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Validated FFQs | Assess habitual dietary intake | Semi-quantitative FFQs with portion sizes [33] |

| Biobanking | Storage of biological samples for future analysis | UK Biobank's collection of blood, urine, saliva [37] |

| Biomarker Measurements | Objective measures of nutritional status | Serum 25(OH)D for vitamin D status [39] |

| Genetic Data | Enable Mendelian randomization approaches | Genotyping arrays in UK Biobank [37] |

| Covariate Databases | Control for potential confounding | Standardized demographic, clinical, lifestyle data [32] |

| Statistical Code | Implement complex adjustment and modeling | R, STATA, SAS packages for survival analysis [38] |

Biological Mechanisms Linking Diet to Chronic Disease Risk

Prospective cohort studies have contributed significantly to understanding the biological pathways through which dietary patterns influence chronic disease risk. Several key mechanisms have emerged from these investigations:

Insulinemic and Inflammatory Pathways

The NHS and HPFS analyses have demonstrated that dietary patterns associated with lower insulinemic and inflammatory potential provide the strongest protection against major chronic diseases [33]. The empirical dietary index for hyperinsulinemia (EDIH) and empirical dietary inflammatory pattern (EDIP) represent mechanism-based scores derived from plasma biomarkers of insulin resistance (C-peptide) and inflammation (IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2) [33]. Diets high in sugar-sweetened beverages, processed meats, and other high-glycemic foods activate these pathways, promoting cellular environments favorable to cancer development, atherosclerosis, and metabolic dysfunction.

Aging-Related Pathways

UK Biobank research has identified multiple aging-related pathways modulated by dietary factors, including telomere length maintenance, phenotypic age acceleration, and brain structure preservation [37]. Plant-based food consumption correlates with increased telomere length and reduced phenotypic age, while animal-based food intake shows opposite associations [37]. Mendelian randomization analyses suggest causal benefits of carbohydrate intake for reducing phenotypic age and increasing whole-brain grey matter volume [37].

Key Biological Pathways Linking Diet to Chronic Disease Risk

Global Burden and Future Projections

Analyses from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 provide critical context for understanding the population-level impact of dietary risk factors on chronic disease burden worldwide [38]. From 1990 to 2021, global age-standardized mortality rates and disability-adjusted life year rates associated with dietary factors decreased by approximately one-third for neoplasms and cardiovascular diseases [38].

The specific dietary risk factors vary by socioeconomic development level. In high sociodemographic index regions, neoplasm-related deaths show stronger correlation with diets high in red meat, while cardiovascular disease burden is primarily linked to low-grain diets, and diabetes burden associates with increased processed meat intake [38]. In low sociodemographic index regions, diets low in vegetables show the strongest association with neoplasm-related mortality, while diets low in fruits significantly impact cardiovascular disease and diabetes burden [38].

Projections through 2030 indicate continued declines in mortality from neoplasms and cardiovascular diseases attributable to dietary factors, but a slight increase in diabetes mortality rates [38]. These trends highlight the evolving challenge of diet-related chronic diseases and the need for targeted interventions across different global contexts.

Prospective cohort designs leveraging large-scale studies like the NHS, HPFS, and UK Biobank have fundamentally advanced our understanding of how dietary patterns influence chronic disease risk and healthy aging. The consistent evidence from these studies demonstrates that dietary patterns emphasizing plant-based foods, unsaturated fats, whole grains, and lean protein sources while minimizing red and processed meats, sugary beverages, and refined carbohydrates offer significant protection against major chronic diseases and promote healthy aging.

The methodological rigor of these studies—including repeated dietary assessments, comprehensive outcome ascertainment, sophisticated statistical adjustment, and incorporation of biomarker and genetic data—provides a robust foundation for public health recommendations and clinical guidelines. Future research should continue to leverage these rich resources to examine dietary patterns in diverse populations, understand biological mechanisms, and inform personalized nutrition approaches that maximize healthspan and reduce the global burden of chronic diseases.

The application of omics technologies has revolutionized nutritional science by providing unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms linking dietary patterns to chronic disease risk. Metabolomics and microbiome analysis serve as complementary approaches that bridge the gap between dietary exposure and physiological outcomes, revealing the complex interplay of microbial communities and their metabolic products that modulate human health. These technologies capture the functional readout of the host-microbiome interface, where dietary components are transformed into bioactive metabolites that influence host physiology through multiple signaling pathways. The integration of these data layers provides a systems biology framework for moving beyond correlation to establish causal mechanisms in diet-disease relationships, offering potential for targeted therapeutic interventions and personalized nutrition strategies that disrupt disease pathways at their metabolic origins.

Analytical Methodologies in Metabolomics and Microbiome Research

Metabolomic Profiling Technologies

Metabolomic analysis employs two primary analytical platforms: mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. MS-based approaches, particularly when coupled with liquid chromatography (LC) or gas chromatography (GC), offer high sensitivity and the ability to characterize thousands of metabolites simultaneously. The Nightingale Health platform represents a high-throughput 1H-NMR approach that profiles 249 metabolites primarily in energy and lipid metabolism pathways, providing absolute quantification with high reproducibility [40]. In contrast, untargeted MS platforms like that used in the ATBC Study can measure over 1,300 metabolites, including chemically identified compounds spanning amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates, and xenobiotics, providing broader coverage of the metabolome [41].

Table 1: Key Analytical Platforms in Metabolomics

| Platform | Metabolite Coverage | Key Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | 1,000+ metabolites | High sensitivity, structural information | Untargeted discovery, complex biomarker profiling |

| GC-MS | 500-1,000 metabolites | Reproducible separation, compound libraries | Metabolic pathways, volatile compounds |

| 1H-NMR (Nightingale) | 249 metabolites | Absolute quantification, high throughput | Large cohort studies, lipid and energy metabolism |

| FIA-MS/MS (Biocrates p500) | 630 metabolites | Targeted quantification, validated assays | Ceramides, acylcarnitines, bile acids |

Sample preparation protocols vary by platform but typically involve protein precipitation using organic solvents (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile) for MS-based approaches, while NMR requires minimal sample preparation. Quality control measures include the use of pooled quality control samples, internal standards, and blinded replicate samples to monitor technical variation, with intraclass correlation coefficients typically exceeding 0.85 for robust metabolites [41].

Microbiome Analysis Techniques