Modern Extraction Methods for Bioactive Plant Compounds: From Fundamentals to Pharmaceutical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the evolution of extraction techniques for bioactive plant compounds, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Modern Extraction Methods for Bioactive Plant Compounds: From Fundamentals to Pharmaceutical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the evolution of extraction techniques for bioactive plant compounds, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of phytochemical extraction, details both conventional and advanced green extraction technologies, and provides systematic optimization strategies to enhance yield and purity. The article further examines rigorous validation protocols and comparative analytical techniques essential for ensuring extract quality, reproducibility, and therapeutic efficacy in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications.

The Foundation of Plant Bioactives: From Traditional Use to Modern Science

Classification and Natural Origins of Key Bioactive Compounds

Bioactive compounds are extra-nutritional constituents that naturally occur in small quantities in plant and animal products, providing significant health benefits beyond basic nutrition [1] [2]. These compounds demonstrate a wide range of therapeutic effects, mediated through mechanisms such as antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory responses, modulation of gut microbiota, and enzyme inhibition [1]. The table below summarizes major classes of bioactive compounds, their key functions, and primary natural sources.

Table 1: Major Classes of Bioactive Compounds and Their Sources

| Compound Class | Examples | Major Food Sources | Key Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | Quercetin, Catechins, Resveratrol, Chlorogenic Acid | Berries, apples, green tea, coffee, red wine, cocoa | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular protection, neuroprotection [1] [3] |

| Carotenoids | Beta-carotene, Lutein, Lycopene | Carrots, tomatoes, spinach, bell peppers, corn | Vision health, immune support, skin protection, antioxidant [1] |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | EPA, DHA, ALA | Fatty fish, flaxseeds, walnuts, chia seeds | Cardiovascular health, anti-inflammatory, cognitive function [1] |

| Alkaloids | Caffeine, Morphine, Quinine | Coffee, tea, cacao, opium poppy | Stimulant, analgesic, antimalarial [4] |

| Terpenoids | Monoterpenes, Sesquiterpenes | Citrus peels, thyme, sage, eucalyptus | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, insecticidal [4] |

| Probiotics & Prebiotics | Lactic acid bacteria, Fructooligosaccharides | Yogurt, kefir, kimchi, onions, asparagus | Gut health modulation, immune enhancement, digestive health [1] |

Analytical Techniques for Identification and Characterization

The identification and characterization of bioactive compounds require sophisticated analytical technologies to ensure accuracy, reproducibility, and quality control [5] [6]. The selection of methodology depends on the compound's nature, concentration, and the matrix from which it is extracted.

Chromatographic Techniques

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is a versatile, robust, and widely used technique for the isolation and quantification of natural products [5]. When coupled with different detectors, it becomes exceptionally powerful:

- HPLC with Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-QTOF-MS): This technique provides high-resolution mass measurement, enabling the tentative identification of compounds based on precise molecular formula assignment and fragmentation patterns [7] [3]. For example, it has been successfully used to identify ten compounds, including flavonoids like isoquercetin and amentoflavone, in Juniperus chinensis L. leaves [7].

- HPLC with Photo-Diode Array Detection (HPLC-DAD): Allows for the quantification of compounds based on their UV-Vis spectra and retention times compared to authentic standards [3]. This method was used to quantify parishin A and chlorogenic acid in Maclura tricuspidata fruit [3].

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) serves as a preliminary screening tool to determine the number of components in a mixture. When combined with bio-autography, it becomes a powerful method for localizing antimicrobial compounds directly on the chromatogram, facilitating bioassay-guided isolation [5].

Non-Chromatographic Techniques

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Used to identify functional groups and elucidate the structure of purified compounds [5].

- Immunoassays: Utilize monoclonal antibodies for highly specific detection of target compounds, though their application is more limited [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioactive Compound Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | To solubilize and extract target compounds from plant matrix. | Methanol, Ethanol, Water, Hexane, Ethyl-acetate. Choice depends on compound polarity [5] [6]. |

| Chromatography Columns | To separate complex mixtures of compounds. | C18 reverse-phase columns are standard for HPLC analysis of polyphenols [7] [3]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | For instrument calibration and accurate mass measurement. | Often a mixture of known compounds is infused for constant calibration during QTOF-MS analysis [7]. |

| Authentic Reference Compounds | For positive identification and quantification via retention time and spectral matching. | Commercially available pure compounds (e.g., quercetin, chlorogenic acid) are essential for validation [7] [3]. |

| Bio-autography Agar Media | To culture microorganisms for detecting antimicrobial activity on TLC plates. | Nutrient Agar or Mueller-Hinton Agar seeded with test bacteria like Bacillus subtilis or Escherichia coli [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Extraction and Analysis

Protocol 1: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Polyphenols

Principle: This modern extraction method uses acoustic cavitation to disrupt plant cell walls, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds at lower temperatures, thereby preserving heat-sensitive bioactives and improving efficiency [8] [6].

Materials and Equipment:

- Plant material (dried and finely ground)

- Ethanol (70-80% aqueous solution)

- Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator

- Centrifuge

- Rotary evaporator

- Analytical balance

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 1.0 g of finely powdered plant material into a conical flask.

- Solvent Addition: Add 20 mL of 70% ethanol to the flask.

- Sonication: Place the flask in an ultrasonic bath and extract for 15-30 minutes at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C). Alternatively, use a probe sonicator with controlled pulse cycles.

- Separation: Centrifuge the mixture at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the solid residue.

- Concentration: Carefully decant the supernatant and concentrate it under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at 40°C.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried extract in a known volume of methanol for subsequent analysis.

- Storage: Store the extract at -20°C if not used immediately.

Advantages: Reduced extraction time, lower solvent consumption, higher yield of thermolabile compounds, and improved antioxidant activity of the extract compared to conventional Soxhlet extraction [6].

Protocol 2: HPLC-QTOF-MS Analysis for Compound Identification

Principle: This protocol combines the separation power of HPLC with the high mass accuracy and structural elucidation capabilities of QTOF-MS to identify unknown compounds in a complex plant extract [7] [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Crude plant extract

- HPLC-grade solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol, Water)

- Formic Acid

- UPLC/QTOF-MS system

- C18 reverse-phase column (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Filter the reconstituted extract through a 0.22 µm membrane filter.

- HPLC Conditions:

- Mobile Phase: (A) 0.1% Formic acid in water; (B) 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile.

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 25-30 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 40°C.

- Injection Volume: 2-5 µL.

- QTOF-MS Conditions:

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), both positive and negative modes.

- Mass Range: 50-1500 m/z.

- Capillary Voltage: 3.0 kV.

- Source Temperature: 120°C.

- Desolvation Temperature: 350°C.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire data in MSE mode (low and high collision energy) to get precursor and fragment ion data simultaneously.

- Process data using dedicated software (e.g., UNIFI, MassLynx).

- Identify compounds by comparing accurate mass, isotopic pattern, and fragmentation spectra with databases (e.g., ChemSpider) and literature. Confirm identities using authentic standards when available [7].

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Bioactive compounds exert their health benefits through interactions with various molecular targets and signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates key mechanisms, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial actions.

The therapeutic efficacy of these compounds is highly dependent on the extraction technique used, as different methods influence the stability and concentration of the functional phytochemicals [6]. For instance, ultrasound-assisted extraction better preserves heat-sensitive flavonoids, leading to extracts with superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity compared to conventional Soxhlet extraction [6].

Quantitative Analysis and Bioactivity Correlation

Robust quantitative analysis is essential for standardizing extracts and correlating specific compounds with observed bioactivities. Advanced analytical techniques enable precise measurement, as demonstrated in the following studies.

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of Bioactive Compounds in Selected Plant Studies

| Plant Source | Analytical Method | Key Compounds Quantified | Concentration | Correlated Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juniperus chinensis L. Leaves [7] | UPLC-MS/MS | Quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnoside | 203.78 mg/g | Antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Bordetella pertussis) |

| Amentoflavone | 69.84 mg/g | |||

| Novel Apple Genotypes [9] | HPLC | Catechins, Epicatechins, Quercetin, Rutin | Varies by genotype | Antioxidant activity (DPPH assay); strong correlation between total phenolic content and antioxidative potential |

| Maclura tricuspidata Fruit [3] | HPLC | Parishin A | Highest abundance | Overall antioxidant activities (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP); higher in immature stages |

| Chlorogenic Acid | Significant levels |

The data in Table 3 highlights that the concentration of bioactive compounds can vary significantly between plant species, tissue types, and maturity stages. Furthermore, a direct correlation often exists between the concentration of these compounds, particularly phenolics, and the antioxidant potency of the extract, underscoring their role as primary contributors to bioactivity [9] [3].

The Crucial Role of Extraction in Harnessing Plant-Based Therapeutics

The extraction process serves as the foundational and most critical step in transforming raw plant materials into standardized, therapeutically active agents. This initial stage directly determines the yield, composition, and biological efficacy of the final extract, influencing all subsequent pharmacological testing and clinical applications [10] [5]. Inefficient or inappropriate extraction techniques can compromise the integrity of heat-sensitive bioactive compounds, lead to the co-extraction of undesirable impurities, and ultimately result in inconsistent or suboptimal therapeutic outcomes [6].

Recent advancements have catalyzed a shift from conventional methods towards modern, sustainable techniques such as Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) and Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE). These innovative approaches are designed to enhance extraction efficiency, reduce solvent consumption, and better preserve the delicate chemical structures of active constituents [8] [11]. The selection of an optimal extraction protocol is therefore paramount, as it must carefully balance maximum yield with the preservation of the native bioactivity profile, ensuring the production of high-quality, reproducible plant-based therapeutics for rigorous scientific evaluation [6].

Conventional vs. Modern Extraction Techniques: A Comparative Analysis

The choice of extraction methodology profoundly impacts the chemical profile of the resulting plant-based therapeutic. Techniques are broadly categorized into conventional and modern methods, each with distinct operational principles, advantages, and limitations.

Conventional Extraction Techniques

Conventional methods have formed the backbone of plant extraction for centuries and are characterized by their reliance on simple equipment, relatively large solvent volumes, and, often, prolonged extraction times [12].

- Maceration: This process involves steeping powdered plant material in a solvent for an extended period, typically several days, with occasional agitation. The mixture is then separated, and the marc (the damp solid residue) is pressed to recover any residual extract [10] [12]. While simple and inexpensive, its main drawbacks are long extraction times and lower efficiency [12].

- Percolation: In this continuous process, the solvent gradually passes through the bed of plant material, extracting soluble constituents as it flows. The resulting liquid, known as the percolate, is collected continuously. This method is generally more efficient than maceration as it maintains a constant concentration gradient between the plant material and the fresh solvent [10] [12].

- Soxhlet Extraction: This is a semi-continuous method where the same solvent is repeatedly recycled through the plant material via distillation and siphoning. It is highly effective for extracting compounds with low solubility and is considered a benchmark for exhaustive extraction. However, its use of prolonged heating at the solvent's boiling point poses a significant risk of thermal degradation for sensitive molecules like certain flavonoids and polyphenols [6] [5].

- Decoction: This method involves boiling plant material, typically hard or woody parts like roots and barks, in water for a sustained period. It is suitable for heat-stable, water-soluble compounds. A key limitation is that the high temperatures can cause hydrolysis or degradation of thermolabile constituents [10] [12].

Modern Extraction Techniques

Modern or "green" extraction technologies have been developed to overcome the limitations of conventional methods. They typically offer improved efficiency, reduced solvent consumption, and shorter processing times, while better preserving the integrity of bioactive compounds [8] [11].

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): This technique utilizes high-frequency sound waves (typically 20-100 kHz) to create cavitation bubbles in the solvent. The implosion of these bubbles generates intense local shear forces and microturbulence, which disrupts plant cell walls and enhances mass transfer [11]. UAE is renowned for its ability to significantly increase extraction yields of compounds like flavonoids while operating at lower temperatures, thus minimizing thermal damage [6].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): MAE employs microwave energy to heat the water and other polar molecules within plant cells directly. This rapid internal heating creates high pressure within the cells, leading to rupture and the efficient release of intracellular compounds into the surrounding solvent [11]. MAE is highly effective for the rapid extraction of a wide range of phytochemicals [8].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): SFE, most commonly using supercritical CO₂ (scCO₂), leverages the unique gas-like diffusivity and liquid-like density of a supercritical fluid. The solvating power of scCO₂ can be finely tuned by adjusting temperature and pressure, allowing for highly selective extraction. It is particularly advantageous for extracting non-polar compounds like essential oils and terpenoids, and it leaves no toxic solvent residues in the final product [8] [11].

- Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE): This method uses specific enzymes (e.g., cellulase, pectinase) to hydrolyze and break down the structural components of plant cell walls (cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin). This breakdown facilitates the release of bound intracellular compounds, often increasing the yield of target bioactives such as glycosides and polysaccharides [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds from Plants.

| Extraction Technique | Operational Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Solvents Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration [10] [12] | Passive soaking of plant material in solvent. | Simple, low equipment cost, suitable for thermolabile compounds. | Long extraction time, low efficiency, high solvent consumption. | Ethanol, Methanol, Water |

| Soxhlet Extraction [6] [5] | Continuous cycling of fresh solvent via distillation. | Exhaustive extraction, high yield for stable compounds. | High temperature degrades thermolabile compounds, high solvent use, long time. | Hexane, Ethanol, Petroleum Ether |

| Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE) [6] [11] | Cell wall disruption via acoustic cavitation. | Rapid, lower temperature, higher yield, reduced solvent. | Potential for free radical formation, scale-up challenges. | Ethanol, Water, Methanol |

| Microwave-Assisted (MAE) [8] [12] | Rapid internal heating and cell rupture via microwave energy. | Very fast, low solvent consumption, high efficiency. | Not ideal for heat-sensitive compounds, uneven heating possible. | Ethanol, Water |

| Supercritical Fluid (SFE) [8] [11] | Solvation using supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂). | Tunable selectivity, no solvent residue, high purity. | High capital cost, high pressure operation, best for non-polar compounds. | Supercritical CO₂ (with/without modifers) |

| Enzyme-Assisted (EAE) [6] | Enzymatic hydrolysis of cell walls to release compounds. | High selectivity, mild conditions, improves yield of bound compounds. | Enzyme cost, need for optimized conditions (pH, temperature). | Water-based buffers |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Extraction Methods

To ensure reproducibility and high-quality results in research, standardized protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for one conventional and two modern extraction techniques.

Protocol 1: Maceration of Plant Material for Phytochemical Screening

Principle: This method relies on passive diffusion, where the solvent penetrates the plant tissue to dissolve soluble constituents, establishing a concentration equilibrium over time [10] [12].

Materials:

- Plant Material: Dried and finely powdered (e.g., 100 g of Serpylli herba or other relevant herb) [6].

- Solvent: 1 L of 50-70% Ethanol (v/v) in water [10] [12].

- Equipment: Glass container with airtight lid, mechanical shaker (optional), filtration setup (e.g., Buchner funnel and filter paper), rotary evaporator.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Weigh 100 g of accurately weighed, dried, and powdered plant material.

- Maceration: Place the powder in a glass container and add 1 L of 50% ethanol. Seal the container tightly to prevent solvent evaporation.

- Agitation: Allow the mixture to stand at room temperature for a minimum of 3 days, with occasional shaking or stirring to enhance extraction [10]. For improved yield, mechanical shaking can be employed [6].

- Filtration: After 3 days, separate the liquid extract from the solid marc by filtration. Press the marc to recover as much extract as possible.

- Concentration: Combine the filtrates and concentrate under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at a temperature not exceeding 40°C to prevent compound degradation.

- Storage: The resulting crude extract can be stored in a sealed, light-resistant container at 4°C for further phytochemical analysis [10].

Protocol 2: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Flavonoids from Citrus Peel

Principle: This protocol leverages acoustic cavitation to disrupt plant cell walls, facilitating the rapid and efficient release of intracellular flavonoids like hesperidin at lower temperatures, thereby preserving their antioxidant activity [6].

Materials:

- Plant Material: 10 g of dried and milled citrus peel (e.g., orange or lemon).

- Solvent: 200 mL of 70% Ethanol (v/v) in water [6].

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator (with temperature control), analytical balance, filtration setup, rotary evaporator.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Weigh 10 g of dried citrus peel powder and place it in a glass Erlenmeyer flask.

- Solvent Addition: Add 200 mL of 70% ethanol to the flask, ensuring the powder is fully immersed.

- Sonication: Place the flask in an ultrasonic bath (or use a probe sonicator) and sonicate for 20 minutes. Maintain the temperature of the extraction mixture below 40°C by using a circulating water bath or ice, if necessary.

- Filtration: After sonication, filter the mixture immediately to separate the solid residue from the liquid extract.

- Concentration: Concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure at 40°C using a rotary evaporator.

- Analysis: The dry extract can be analyzed for total flavonoid content and antioxidant activity (e.g., by DPPH assay). Yields are consistently higher and bioactivity better preserved compared to Soxhlet extraction [6].

Protocol 3: Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) of Phenolic Compounds fromCajanus cajanLeaves

Principle: Microwave energy causes rapid and volumetric heating of moisture within plant cells, generating high internal pressure that ruptures the cells and forces out bioactive compounds, drastically reducing extraction time [12] [2].

Materials:

- Plant Material: 5 g of dried and powdered Cajanus cajan leaves.

- Solvent: 100 mL of 80% Methanol (v/v) in water.

- Equipment: Closed-vessel microwave extraction system, Teflon vessels, volumetric flasks, filtration setup, rotary evaporator.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Accurately weigh 5 g of powdered plant material and transfer it to a Teflon microwave vessel.

- Solvent Addition: Add 100 mL of 80% methanol to the vessel and seal it securely.

- Microwave Extraction: Place the vessel in the microwave system and irradiate at a controlled power (e.g., 500 W) for 5 minutes, ensuring the temperature does not exceed 60°C to protect heat-sensitive phenolics.

- Cooling and Filtration: After irradiation, carefully remove the vessel and allow it to cool. Once safe to handle, open the vessel and filter the contents.

- Concentration: Evaporate the solvent from the filtrate using a rotary evaporator at 40°C to obtain the phenolic-rich extract.

- Validation: The efficiency can be validated by quantifying specific markers like orientin and luteolin using HPLC, demonstrating superior yield compared to maceration [2].

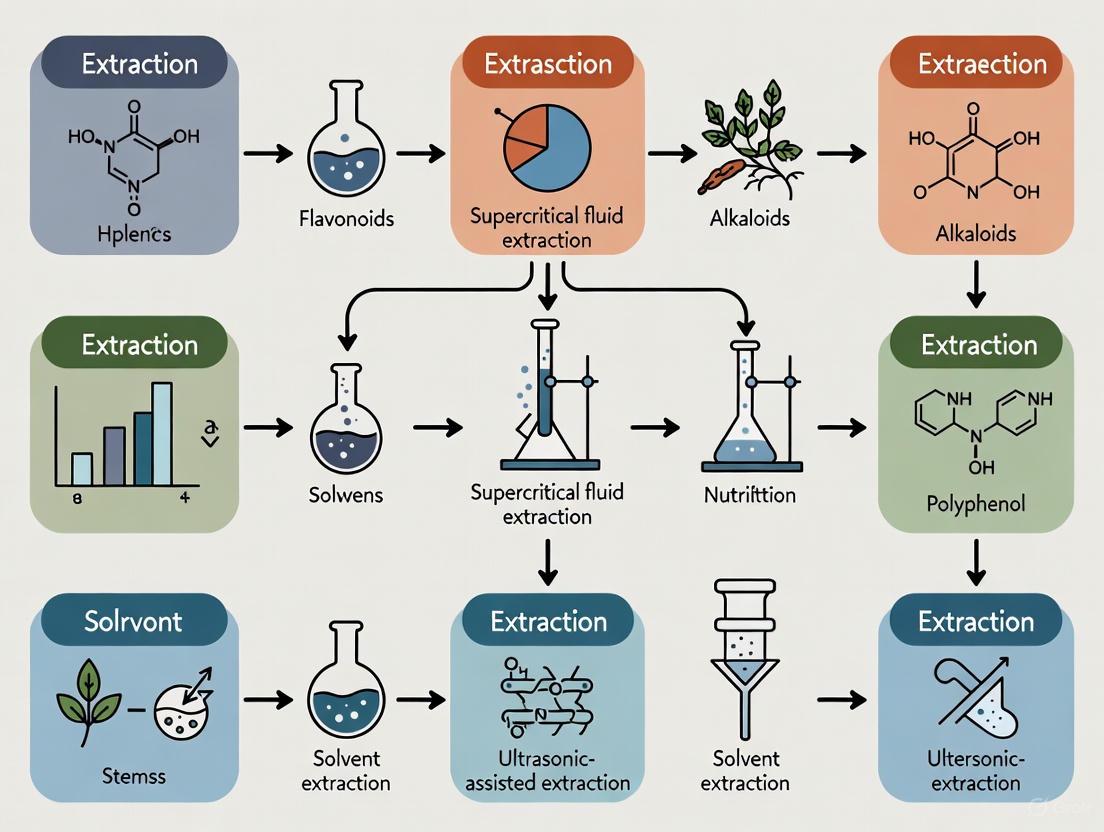

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting an appropriate extraction method based on research objectives, distinguishing between conventional and modern techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful extraction relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The selection of solvent is arguably the most critical parameter, as its polarity must align with the target compounds to ensure high solubility and selectivity [10] [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Extraction Protocols.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol [10] | Universal polar solvent for phenolics, flavonoids, alkaloids. | GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status; concentrations of 20-70% are self-preservative. |

| Methanol [10] [5] | Efficient solvent for a broad range of polar phytochemicals. | Higher toxicity compared to ethanol; requires careful handling and disposal. |

| Water [10] | Solvent for polar compounds like polysaccharides and glycosides. | Can hydrolyze some compounds; promotes microbial growth; requires sterilization. |

| Ethyl Acetate [10] | Intermediate polarity solvent; ideal for medium polarity compounds (e.g., many aglycones). | Commonly used in liquid-liquid partitioning of crude extracts. |

| n-Hexane [10] [5] | Non-polar solvent for defatting and extracting lipids, waxes, essential oils. | Highly flammable; used to remove chlorophyll and other non-polar impurities. |

| Supercritical CO₂ [8] [11] | Green, tunable solvent for non-polar compounds in SFE. | Leaves no solvent residue; requires high-pressure equipment. |

| Cellulase/Pectinase Enzymes [6] | Used in EAE to hydrolyze cell wall polymers and release bound compounds. | Requires optimization of pH, temperature, and incubation time. |

Post-Extraction: Isolation and Characterization of Bioactives

Following extraction, the crude mixture requires further processing to isolate and identify the individual bioactive compounds responsible for the observed therapeutic effects. This process typically involves a combination of chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques [10] [5].

Isolation and Purification Techniques

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): A rapid, cost-effective technique used for the initial phytochemical screening of extracts. It provides a fingerprint of the complex mixture and can be used to guide the development of subsequent separation methods. TLC can be coupled with bioautography to directly locate antimicrobial compounds on the plate [5].

- Column Chromatography (CC): A versatile workhorse for the fractionation of crude extracts. The extract is loaded onto a column packed with a stationary phase (e.g., silica gel, Sephadex), and different compounds are eluted using solvents of increasing polarity. This technique is excellent for separating complex mixtures into simpler fractions [5] [12].

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): The gold standard for the analytical and preparative separation of natural products. HPLC provides high resolution, sensitivity, and reproducibility, making it ideal for quantifying specific bioactive markers in an extract, which is crucial for standardization and quality control [10] [5].

Characterization and Identification Techniques

Once purified, the structural elucidation of isolated compounds is achieved through spectroscopic methods:

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Determines the molecular weight and provides fragmentation patterns that offer clues about the compound's structure [5].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: (e.g., ¹H and ¹³C NMR) is indispensable for determining the precise carbon-hydrogen framework and functional groups of a molecule, allowing for full structural assignment [5].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Helps identify characteristic functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl) in the molecule [5].

Diagram 2: A bioassay-guided isolation workflow for the discovery of bioactive compounds from a crude plant extract.

The extraction process is undeniably the cornerstone of harnessing the therapeutic potential of plants. It is a sophisticated and multi-faceted operation that directly dictates the quality, efficacy, and safety of the final botanical product. While conventional methods like maceration and Soxhlet extraction provide a historical foundation, the clear trend in research and industry is toward the adoption of modern techniques such as UAE, MAE, and SFE. These advanced methods offer compelling advantages in terms of efficiency, sustainability, and the preservation of delicate bioactive chemistries.

The future of plant-based therapeutic development lies in the strategic integration of these techniques—so-called hybrid approaches—and their optimization using data-driven modeling. By selecting and executing the most appropriate extraction protocol, researchers can ensure the production of standardized, potent, and clinically relevant plant-derived medicines, fully unlocking the promise held within the world's botanical resources.

The extraction of bioactive compounds from plants is a foundational step in natural product research and drug development. Conventional techniques such as maceration, percolation, and Soxhlet extraction have been utilized for decades as standard methods for isolating phytochemicals. These methods employ principles of solubility, diffusion, and continuous displacement to recover target compounds from plant matrices [10]. While modern approaches offer enhanced efficiency, understanding these classical methods remains crucial for developing effective extraction protocols and appreciating the evolution of extraction technologies. This application note provides a detailed examination of these three conventional extraction techniques, including their operational principles, standardized protocols, and comparative performance characteristics to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing methods for specific applications in phytochemical research.

Principles and Mechanisms

Maceration

Maceration is a simple solid-liquid extraction process where powdered plant material is immersed in a solvent within a closed container for a defined period, typically with frequent agitation [10]. The process relies on differential concentration gradients that drive the diffusion of soluble constituents from plant cells into the solvent. As the solvent penetrates the cellular structure, it dissolves the active compounds, creating a concentrated solution that is subsequently separated from the marc (insoluble residue) through filtration or decantation [10]. This method is particularly suitable for heat-sensitive compounds and is characterized by its operational simplicity and minimal equipment requirements.

Percolation

Percolation involves the continuous, downward passage of a solvent through a stationary bed of powdered plant material contained in a specialized vessel known as a percolator [10]. This dynamic process maintains a constant concentration gradient, facilitating more efficient extraction compared to static methods. The solvent gradually saturates the plant matrix as it flows downward, dissolving soluble constituents before being collected as the extract or "micelle" [10]. The continuous solvent flow prevents equilibrium establishment between the plant material and solvent, resulting in more exhaustive extraction. The percolation process exhibits critical behavior where the formation of a connected network allows for continuous flow, with the percolation threshold representing the critical solvent density required for this connectivity [13].

Soxhlet Extraction

Soxhlet extraction represents an automated, continuous approach where the sample is repeatedly exposed to fresh solvent cycles through a unique siphon mechanism [14]. The apparatus consists of three main components: a flask containing the boiling solvent, an extraction chamber housing the sample in a porous thimble, and a condenser for solvent reflux [14]. The process begins with solvent heating and vaporization, followed by condensation and drip-wise passage through the sample. When the solvent level reaches the siphon threshold, the solution containing extracted compounds automatically returns to the flask, leaving the solute while the solvent recommences the cycle [15]. This method enables repeated extraction with relatively small solvent volumes and operates unattended once initiated.

Experimental Protocols

Maceration Protocol

Materials Required:

- Plant material (dried and powdered)

- Selected solvent (e.g., ethanol, methanol, water, or hydroalcoholic mixtures)

- Sealed container (amber glass preferred for light-sensitive compounds)

- Orbital shaker or magnetic stirrer (optional)

- Filtration apparatus (filter paper, Buchner funnel, or muslin cloth)

- Evaporation equipment (rotary evaporator or water bath)

Procedure:

- Plant Preparation: Reduce plant material to fine powder (0.2-0.5 mm particle size) to maximize surface area for solvent contact [10].

- Solvent Selection: Choose appropriate solvent based on target compound polarity (e.g., ethanol for medium-polarity compounds, water for polar compounds) [10].

- Immersion: Combine powdered plant material with solvent in a 1:5 to 1:10 ratio (mass:volume) in a sealed container [16].

- Agitation: Maintain continuous or intermittent agitation at 250 rpm for 24 hours at room temperature to enhance mass transfer [16].

- Separation: After 24 hours, separate the liquid extract from the marc through filtration using Whatman No. 1 filter paper or a Buchner funnel.

- Concentration: Concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at temperatures not exceeding 40°C to preserve thermolabile compounds.

- Storage: Store the concentrated extract in airtight, amber glass containers at 4°C until further analysis.

Optimization Notes:

- For exhaustive extraction, repeat the process with fresh solvent on the same marc and combine filtrates.

- Extend maceration time to 3-7 days for hard plant materials or compounds with slow diffusion rates.

- Adjust pH of solvent to enhance extraction of specific compound classes (e.g., acidified solvent for alkaloids).

Percolation Protocol

Materials Required:

- Percolator (cylindrical vessel with controlled outlet)

- Plant material (dried and powdered)

- Selected extraction solvent

- Cotton plug or glass wool

- Collection vessel

Procedure:

- Plant Preparation: Moisten the powdered plant material with a small quantity of solvent and allow to stand for 15-30 minutes to facilitate swelling [10].

- Percolator Packing: Place a cotton plug at the percolator base, then uniformly pack the moistened plant material without creating channels or excessive compaction.

- Solvent Addition: Add sufficient solvent to cover the plant material completely, then open the outlet slightly to allow air escape before closing it again.

- Maceration Phase: Allow the closed system to stand for 24 hours to enable preliminary extraction and solvent penetration [10].

- Continuous Extraction: After the maceration period, open the outlet to maintain a slow, continuous flow (approximately 1-2 mL per minute per 100g of material).

- Collection: Collect the percolate (micelle) in a clean vessel until the plant material is exhausted (typically 3-5 times the material volume).

- Concentration: Concentrate the percolate using a rotary evaporator at appropriate temperatures.

Optimization Notes:

- Maintain a constant solvent layer above the plant material throughout the process.

- Adjust flow rate to balance extraction efficiency and processing time.

- For difficult extractions, consider using a gradient solvent system with increasing polarity.

Soxhlet Extraction Protocol

Materials Required:

- Soxhlet apparatus (flask, extraction chamber, condenser)

- Solvent (low-boiling point preferred)

- Extraction thimbles (cellulose or glass fiber)

- Heating mantle or water bath

- Plant material (dried and powdered)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 1-10g of dried, powdered plant material and place in a dry extraction thimble [16].

- Apparatus Assembly: Place the thimble in the extraction chamber. Add an appropriate solvent (typically 100-200mL) to the flask, ensuring it will not siphon directly without passing through the sample.

- Extraction Cycle: Heat the flask to maintain a solvent boiling rate that produces 3-6 siphon cycles per hour [14].

- Process Continuation: Continue extraction for 6-24 hours, depending on the sample and target compounds.

- Concentration: After completion, recover the extract from the flask and concentrate using a rotary evaporator.

- Residual Solvent Removal: Remove any remaining solvent from the marc by allowing the thimble to dry completely.

Optimization Notes:

- Select solvents with appropriate boiling points to balance extraction efficiency and compound stability.

- For thermolabile compounds, consider using a cooling system to minimize thermal degradation.

- The number of cycles should be optimized based on the specific plant material and target compounds.

Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Operational Parameters of Conventional Extraction Methods

| Parameter | Maceration | Percolation | Soxhlet Extraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Principle | Passive diffusion with agitation | Continuous solvent flow | Repeated washing with fresh solvent via reflux |

| Temperature | Room temperature (25-30°C) | Room temperature (25-30°C) | Solvent boiling point (e.g., 78°C for ethanol) |

| Time Requirement | 24 hours to several days [16] | 24-72 hours | 6-24 hours [14] |

| Solvent Consumption | High (single use) | Moderate | Low (recycled solvent) [15] |

| Efficiency | Moderate | Good to high | High for stable compounds [15] |

| Automation Level | Low (requires manual separation) | Low to moderate | High (continuous operation) [14] |

| Suitable Compounds | Heat-sensitive compounds | Most plant constituents | Thermally stable, non-polar compounds |

Table 2: Applications and Limitations of Conventional Extraction Methods

| Aspect | Maceration | Percolation | Soxhlet Extraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Applications | Soft plant tissues, heat-sensitive compounds, traditional tinctures | Medium to hard plant tissues, standardized extracts | Lipids, alkaloids, fixed oils, waxes [14] |

| Advantages | Simple equipment, preserves thermolabile compounds, scalable | Maintains concentration gradient, more efficient than maceration | Continuous process, higher efficiency, minimal supervision [15] |

| Disadvantages | Lengthy process, incomplete extraction, high solvent use | Channeling issues, requires uniform packing | Thermal degradation, not suitable for high-boiling solvents [14] |

| Yield Performance | Moderate (65-75% of available compounds) | Good (75-85% of available compounds) | High (80-95% of available compounds) [15] |

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Efficiency for Propolis (Based on Experimental Data) [16]

| Extraction Method | Extraction Yield (%) | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g) | Extraction Time | Solvent Volume (mL/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | 12.5 | 45.2 | 24 hours | 50 |

| Ultrasound-Assisted | 15.8 | 52.7 | 30 minutes | 50 |

| Microwave-Assisted | 14.3 | 48.9 | 2 minutes | 50 |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Conventional Extraction Methods

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Extraction | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 70-95% purity, food/pharma grade | Polar solvent for phenolics, flavonoids, alkaloids | Concentration adjusted based on target compound polarity [16] |

| Methanol | HPLC grade, ≥99% purity | Efficient solvent for broad-range phytochemicals | Toxic; requires proper ventilation and handling [10] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Analytical grade | Medium polarity solvent for medium-polar compounds | Suitable for fractionation and specific compound classes |

| Chloroform | Anhydrous, stabilized | Non-polar solvent for terpenoids, fats, waxes | Carcinogenic; requires strict safety protocols [10] |

| n-Hexane | Technical grade | Lipid and non-polar compound extraction | Highly flammable; effective for defatting procedures |

| Distilled Water | Purified, deionized | Polar solvent for polar compounds, polysaccharides | May require preservatives for extended extraction [10] |

| Extraction Thimbles | Cellulose, size appropriate to apparatus | Sample containment in Soxhlet extraction | Must be compatible with extraction solvent [14] |

| Filter Paper | Whatman No. 1 or equivalent, qualitative grade | Solid-liquid separation after extraction | Particle retention ~11μm for clear filtrate |

Workflow Visualization

Extraction Method Selection Workflow

Soxhlet Extraction Mechanism

Conventional extraction methods including maceration, percolation, and Soxhlet extraction remain fundamentally important in natural product research despite the emergence of modern techniques. Each method offers distinct advantages: maceration for heat-sensitive compounds, percolation for efficient continuous extraction, and Soxhlet for automated exhaustive extraction with solvent recycling. The choice among these methods depends on multiple factors including target compound characteristics, available equipment, time constraints, and desired yield. While these conventional approaches may exhibit limitations in efficiency, solvent consumption, and time requirements compared to emerging technologies, their simplicity, reproducibility, and well-understood mechanisms ensure their continued relevance in phytochemical research and drug development workflows.

The extraction of bioactive compounds from plants is a critical foundational step in natural product research and drug development. The efficiency and success of this process are governed by three interconnected fundamental principles: compound polarity, solvent selection, and mass transfer mechanisms [12]. These principles directly determine the yield, purity, and biological activity of the extracted compounds [6]. Selecting an appropriate solvent based on polarity matching maximizes solubility, while understanding mass transfer principles allows researchers to enhance the diffusion of compounds from the plant matrix into the solvent [17] [12]. This document outlines the core theoretical frameworks and provides standardized protocols to guide researchers in optimizing these parameters for reproducible and high-quality extract production within a research and development context.

Core Principles

The Role of Compound Polarity

Polarity is a fundamental property of molecules that significantly influences their solubility and extraction behavior. The principle of "like dissolves like" is the cornerstone of solvent selection [12]. Bioactive compounds in plants span a wide polarity range; for instance, phenolic compounds and flavonoids are relatively polar, while terpenoids and essential oils are non-polar [18] [6]. The polarity of the target compound dictates the choice of extraction solvent to achieve optimal solubility and yield.

Table 1: Common Bioactive Compound Classes and Their Polarity Characteristics

| Compound Class | General Polarity | Example Compounds | Typical Plant Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Low to Medium Polarity | Vinblastine, Vincristine [18] | Catharanthus roseus [18] |

| Flavonoids | Medium Polarity | Luteolin, Orientoside [12] | Cajanus cajan leaves [12] |

| Terpenoids | Low Polarity | Triterpenes (e.g., in Birch) [19] | Birch bark [19] |

| Saponins | Medium to High Polarity | --- | Sutherlandia frutescens [18] |

| Tannins | High Polarity | --- | Plumbago auriculata [18] |

Solvent Selection Strategy

The solvent is the primary tool for selectively extracting target compounds. Its choice affects not only the yield but also the safety, environmental impact, and downstream processing of the extract.

- Solvent Polarity: Solvents can be categorized by their polarity index. Water, with a high polarity index, is excellent for extracting polar compounds like polysaccharides and tannins. Ethanol and methanol are medium-polarity universal solvents for phytochemical research. Hexane and chloroform, with low polarity, are suitable for lipids and essential oils [17] [12] [20].

- Green Solvent Alternatives: There is a growing shift towards green chemistry in extraction. Bio-based solvents (e.g., ethanol, limonene), supercritical CO₂, and Ionic Liquids/Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) are being adopted to reduce toxicity and environmental footprint [17] [20]. These solvents can be tailored for specific extraction tasks, offering high selectivity and efficiency [20].

Table 2: Solvent Properties and Selectivity for Compound Classes

| Solvent | Polarity Index | Boiling Point (°C) | Target Compound Classes | Safety & Environmental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Hexane | 0.1 | ~69 | Lipids, essential oils, pigments [17] | Highly flammable; significant environmental impact [17] |

| Chloroform | 4.1 | ~61 | Alkaloids, terpenoids [20] | Toxic; suspected carcinogen [20] |

| Ethyl Acetate | 4.4 | ~77 | Medium-polarity phenolics, flavonoids [20] | Less toxic; commonly used in labs [20] |

| Ethanol | 5.2 | ~78 | Wide range (polar & non-polar) [12] | Safe for food/pharma; renewable [17] [20] |

| Methanol | 5.1 | ~65 | Alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides [12] | Toxic; requires careful handling [12] |

| Water | 10.2 | 100 | Polysaccharides, tannins, saponins [12] [19] | Safest solvent; limited ability for non-polar compounds [19] |

Mass Transfer Mechanisms

Mass transfer is the physical process that describes the movement of a solute from the solid plant matrix into the bulk solvent. The process involves three key stages [12]:

- Penetration: The solvent diffuses into the solid plant material.

- Dissolution: The target compounds dissolve into the solvent.

- Diffusion: The dissolved solutes diffuse out of the plant matrix and into the surrounding solvent.

The rate of mass transfer is influenced by several factors [12] [20]:

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase solubility and diffusion rates but risk degrading thermolabile compounds.

- Particle Size: Smaller particle sizes increase the surface area for solvent penetration, enhancing extraction efficiency.

- Concentration Gradient: Maintaining a high difference in solute concentration between the plant matrix and the solvent drives diffusion. Techniques like percolation and Soxhlet extraction continuously refresh the solvent to maintain this gradient [17] [12].

- Agitation: Stirring or mixing reduces the boundary layer around plant particles, facilitating faster mass transfer.

Diagram 1: Sequential Stages of Mass Transfer during Solid-Liquid Extraction. The process involves multiple steps, each influenced by specific chemical and physical factors (red notes).

Integrated Principles in Practice

The core principles of solvent selection and mass transfer are not independent; they interact synergistically to determine the overall extraction outcome. The correct solvent ensures the target compound can dissolve, while optimized mass transfer conditions ensure it is efficiently removed from the plant matrix. Modern extraction techniques often enhance these natural mass transfer processes. For example, Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) uses microwave energy to rapidly heat the plant material and solvent, creating high internal pressure that ruptures cell walls and accelerates dissolution and diffusion [17] [6]. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) employs ultrasonic cavitation to create microscopic bubbles that implode, generating intense local shear forces that break down cell structures and enhance solvent penetration [20] [6].

Diagram 2: Interrelationship of Core Principles and Techniques. The principles are sequential and interdependent, while modern techniques (red) actively enhance both solvent selection and mass transfer processes to improve final outcomes.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Systematic Screening of Solvent Polarity

This protocol is designed to empirically determine the optimal solvent system for extracting target bioactive compounds from a novel plant material.

1. Scope and Application This procedure applies to the initial investigation of plant materials for the recovery of a broad spectrum of phytochemicals. It is particularly useful for identifying the polarity range of unknown bioactive compounds.

2. Principle By using a series of solvents with incrementally increasing polarity, this protocol systematically evaluates extraction efficiency across different chemical classes, from non-polar lipids to highly polar glycosides and sugars [19].

3. Materials and Reagents Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Solvent Polarity Screening

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application in Screening |

|---|---|

| n-Hexane | Extraction of non-polar compounds (e.g., waxes, fixed oils, some terpenoids) [17] |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Extraction of medium-to-low polarity compounds (e.g., alkaloids, certain phenolics) [20] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Extraction of medium-polarity compounds (e.g., flavonoids, coumarins) [20] |

| Ethanol (100%) | Broad-spectrum extraction of both polar and semi-polar compounds; considered a green solvent [12] [20] |

| Ethanol-Water (50:50 v/v) | Enhanced extraction of polar compounds (e.g., polyphenols, glycosides, saponins) [19] |

| Deionized Water | Extraction of highly polar compounds (e.g., polysaccharides, tannins, proteins) [12] [19] |

| Ultrasonic Bath (UAE) | Apparatus to enhance mass transfer via cavitation, reducing extraction time and improving yield [20] [6] |

4. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Reduce the air-dried plant material to a homogeneous powder using a laboratory mill. A standardized particle size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm) is recommended for reproducible results [12].

- Weighing: Accurately weigh 1.0 ± 0.01 g of powdered plant material into six separate, labeled glass vials.

- Solvent Addition: Add 30 mL of each screening solvent (n-hexane, DCM, ethyl acetate, 100% ethanol, 50% ethanol, and water) to the respective vials [19].

- Extraction: Seal the vials and place them in an ultrasonic bath. Conduct extraction for 30 minutes at a controlled temperature of 25°C [19].

- Filtration: After extraction, filter the contents of each vial through filter paper (e.g., Whatman No. 1) to remove solid residues.

- Concentration: Evaporate the filtrates to dryness under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. Adjust the temperature according to solvent boiling point to prevent degradation of thermolabile compounds.

- Weighing and Analysis: Weigh the dry extracts to determine the percentage yield for each solvent. Reconstitute the extracts in a standardized volume of an appropriate solvent (e.g., 50% methanol) for subsequent chemical analysis (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS) and bioactivity assays [19].

Protocol: Investigating Mass Transfer Kinetics

This protocol provides a method to study the rate of compound extraction, which is crucial for scaling up from laboratory to industrial processes.

1. Scope and Application Used to determine the optimal extraction time and understand the mass transfer limitations for a specific plant material and solvent system.

2. Principle The extraction yield of a target compound over time typically follows a curve: an initial rapid phase (controlled by washing from surfaces and easy-to-access cells) followed by a slower phase (controlled by diffusion from the plant's interior). Modeling this curve helps identify the point of diminishing returns [12].

3. Procedure

- Set up a maceration or ultrasonic-assisted extraction using the optimal solvent identified in Protocol 4.1.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes), withdraw a small, precise aliquot (e.g., 1 mL) from the extraction mixture.

- Analysis: Immediately filter each aliquot and analyze the concentration of the target compound(s) using a quantitative technique like HPLC-UV or GC-MS.

- Data Modeling: Plot the concentration of the compound against time. Fit the data to established kinetic models (e.g., Fick's second law of diffusion or a first-order kinetic model) to determine the mass transfer rate and the time required to reach equilibrium [21].

The rational design of an extraction process for plant bioactives hinges on a deep understanding of the synergy between compound polarity, solvent selection, and mass transfer principles. By first characterizing the target compounds and then systematically applying these principles through standardized protocols, researchers can significantly enhance extraction efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability. The integration of modern, green techniques that augment mass transfer further propels the field forward. Mastering these fundamentals is essential for producing high-quality, reproducible extracts for advanced pharmaceutical and nutraceutical research and development.

Strengths and Limitations of Traditional Extraction Approaches

Within the research domain of bioactive compound extraction from plants, the selection of an extraction technique is a critical determinant of the yield, composition, and bioactivity of the final extract [6]. Traditional extraction approaches form the historical and practical foundation of phytochemical research. These methods, which include maceration, percolation, reflux extraction, and Soxhlet extraction, are characterized by their reliance on organic solvents and, frequently, the application of heat to facilitate the mass transfer of compounds from plant matrices into solution [17] [20]. While the development of green and advanced technologies has accelerated, a comprehensive understanding of conventional methods remains indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals. These techniques are often the benchmark against which novel methods are evaluated and are still widely employed in both laboratory and industrial settings due to their simplicity and low initial equipment costs [17] [20]. This review provides a systematic analysis of the strengths and limitations of these core traditional extraction technologies, supported by comparative data and detailed experimental protocols.

Principles and Operational Characteristics

Traditional extraction methods operate on the principle of using a solvent to solubilize and remove target compounds from solid plant material. The efficiency of this process is governed by variables such as solvent polarity, temperature, contact time, and particle size [6] [20]. The fundamental steps involve the penetration of the solvent into the plant matrix, the dissolution of active constituents, and the diffusion of the solutes out of the matrix. A key parameter is the partition coefficient (K_d), which defines the equilibrium distribution of a solute between the solid plant material and the solvent phase [20]. Optimizing these parameters is crucial for maximizing yield while preserving the structural integrity of heat-sensitive bioactives.

The following workflow outlines the general decision-making and experimental process for employing traditional extraction methods in a research setting.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

The selection of an appropriate traditional method depends on the physicochemical properties of the target compounds, the nature of the plant matrix, and considerations of time, cost, and safety. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary traditional extraction techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional Extraction Techniques

| Extraction Technique | Operational Principles | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration [17] | Solvent contact with plant material at room temperature with agitation. | Simple equipment & operation High selectivity with solvent choice Suitable for heat-labile compounds | Time-consuming (long extraction times) High solvent consumption Potential toxic solvent residue | Production of plant absolutes (e.g., violet, osmanthus) [17]; extraction of thermolabile compounds. |

| Percolation [17] | Continuous flow of fresh solvent through a fixed bed of plant material. | Higher efficiency than maceration Maintains concentration gradient Suitable for valuable/toxic compounds | Increased solvent use vs. maceration Channeling can reduce efficiency Can be time-consuming | Traditional Chinese medicine extracts (e.g., belladonna, Polygala) [17]; preparation of high-concentration tinctures. |

| Reflux Extraction [17] | Continuous cycling of boiled and condensed solvent back through the sample. | Avoids solvent loss Higher efficiency for volatile compounds Faster than maceration/percolation | Thermal degradation of heat-sensitive compounds (e.g., some flavonoids, polyphenols) [6] Limited to volatile solvents | Extraction of volatile components like flavonoids and saponins from natural plants [17]. |

| Soxhlet Extraction [17] [20] | Repeated percolation with fresh, condensed solvent in a continuous cycle. | High efficiency (continuous fresh solvent) No filtration required post-extraction Low cost and ease of operation for multiple samples | Very long extraction times High thermal degradation risk [6] Large volumes of toxic solvents | Classic method for lipid extraction; extraction of bioactive compounds from Siraitia grosvenorii and mulberry leaf [17]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Maceration Extraction

This protocol is adapted for the extraction of thermolabile phenolic compounds from dried plant leaves [17] [22].

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Materials for Maceration Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Dried Plant Material | Source of bioactive phytoconstituents. | Dipterocarpus alatus leaves, oven-dried at 70°C [23]. |

| Grinding Mill | Particle size reduction to increase surface area for solvent penetration. | Electric herb miller; target particle size 0.15-0.30 mm [23]. |

| Extraction Solvent (e.g., Ethanol) | Selectively dissolves target compounds based on polarity. | 99.5% Ethanol, suitable for polar and non-polar substances [17] [23]. |

| Orbital Shaker | Provides agitation to enhance mass transfer and prevent channeling. | Capable of 150 rpm, room temperature (20°C) [23]. |

| Buchner Funnel & Filter Paper | Separates the solid marc from the liquid extract. | Whatman filter paper #1 [23]. |

| Rotary Evaporator | Gently removes solvent from the extract under reduced pressure to concentrate bioactives. | Bath temperature 45°C, 50 rpm [23]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Plant Material Preparation: Wash and oven-dry fresh plant leaves at 70°C until a constant weight is achieved [23]. Grind the dried material using a milling apparatus and sieve to a defined particle size (e.g., 0.15-0.30 mm) to maximize surface area [23] [22].

- Solvent Selection: Choose a solvent based on the polarity of the target compounds. Ethanol is often preferred for its ability to extract a wide range of polar and mid-polar compounds and its relatively low toxicity [17].

- Maceration Process: Precisely weigh 100 g of ground plant material and place it in an Erlenmeyer flask. Add 400 mL of solvent (e.g., 99.5% ethanol) to achieve a defined solid-to-liquid ratio (e.g., 1:4 w/v) [23]. Seal the flask and place it on an orbital shaker. Agitate at 150 rpm at room temperature (20°C) for 24 hours [23].

- Separation and Concentration: After 24 hours, vacuum-filter the mixture using a Buchner funnel lined with filter paper. Transfer the filtrate (the miscella) to a rotary evaporator. Concentrate the extract at 45°C under reduced pressure until the volume is reduced to approximately 10% of the original [23]. Further dry the concentrated extract in an oven at 60°C for 24 hours to obtain a dry paste or powder [23].

- Storage: Store the final crude extract paste in a sealed container at 4°C for subsequent phytochemical analysis and bioactivity testing [23].

Protocol for Soxhlet Extraction

This protocol is suitable for the exhaustive extraction of lipids or stable bioactive compounds from seeds or hardy plant tissues [17] [20].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Oven-dry and grind the plant material to a fine powder. Place a known weight (e.g., 10-20 g) of the powder into a cellulose or thimble extraction sleeve. Ensure the powder is not packed too tightly to allow for proper solvent flow.

- Apparatus Assembly: Assemble the Soxhlet apparatus, consisting of a boiling flask, the extraction chamber (containing the thimble), and a water condenser. Fill the boiling flask with a volume of solvent (e.g., hexane or ethanol) that is adequate for several extraction cycles, typically 150-200 mL. Ensure all joints are tightly sealed.

- Extraction Cycle: Heat the solvent in the boiling flask until it boils. The solvent vapor rises into the condenser, where it liquefies and drips into the extraction chamber containing the sample. Once the solvent in the extraction chamber reaches the top of the siphon arm, it automatically siphons back into the boiling flask, carrying the extracted compounds with it. This cycle repeats continuously [20].

- Process Completion: Continue the extraction for a predetermined number of cycles or time (often 6-24 hours, depending on the sample). The process is considered complete when the solvent in the siphon tube appears clear, indicating exhaustive extraction.

- Extract Recovery: Disassemble the apparatus once the extraction is complete. The extracted compounds are now concentrated in the boiling flask. Use a rotary evaporator to remove the solvent from the boiling flask, yielding the crude extract.

Impact on Phytochemical Profile and Bioactivity

The choice of traditional extraction method significantly influences the phytochemical composition and, consequently, the therapeutic potential of the plant extract. Prolonged heating in methods like Soxhlet and reflux extraction can degrade thermolabile compounds such as certain flavonoids, polyphenols, and terpenoids, thereby reducing the extract's overall bioactivity [6]. For instance, studies comparing extraction techniques have demonstrated that heat-intensive methods can result in lower antioxidant activities compared to cooler or faster methods, due to the degradation of phenolic compounds responsible for free radical scavenging [6]. The solvent polarity is another critical factor; polar solvents (e.g., ethanol, methanol, water) favor the extraction of hydrophilic compounds like flavonoids and tannins, while non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane, chloroform) are more effective for lipophilic bioactives such as terpenoids and carotenoids [6]. This selectivity directly impacts the resulting bioactivity profile, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [6].

Traditional extraction approaches, despite their limitations, remain cornerstone techniques in the initial stages of plant-based drug discovery and natural product research. Their strengths of operational simplicity, low technological barrier, and high selectivity for specific compound classes make them viable for many research and industrial applications. However, their inherent drawbacks—including long processing times, high solvent consumption, and the risk of thermal degradation—pose significant challenges for the reproducibility, safety, and efficiency of bioactive compound recovery. A thorough understanding of the principles, strengths, and limitations of maceration, percolation, reflux, and Soxhlet extraction is essential for researchers to design rational extraction protocols. This knowledge also provides a critical foundation for the judicious integration of these classical methods with emerging green extraction technologies, paving the way for more sustainable and effective strategies in phytochemical research.

Green Extraction Technologies: Principles and Industrial Applications

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) is a advanced separation technology that utilizes solvents at temperatures and pressures above their critical point, where distinct liquid and gas phases do not exist [24]. This state creates a supercritical fluid that exhibits unique properties combining the penetrative ability of gases with the solvating power of liquids [25]. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is the most widely used supercritical fluid due to its accessible critical point (31.1°C and 7.39 MPa), non-toxic nature, non-flammability, and low cost [26]. The technology has gained significant prominence as a green and sustainable extraction method, particularly valuable for obtaining biologically active substances from plant materials and food by-products while eliminating the use of hazardous organic solvents [27].

The fundamental principle of SFE relies on the tunable solvating power of supercritical fluids. By manipulating temperature and pressure, the density and thus the solvating strength of the fluid can be precisely controlled, allowing for selective extraction of target compounds [25]. This technique is especially advantageous for extracting heat-sensitive bioactive compounds because it operates at relatively moderate temperatures, preserving the structural integrity and biological activity of the extracted molecules [27]. The supercritical state provides high diffusivity, low viscosity, and no surface tension, enabling the fluid to penetrate deeply into plant matrices and extract compounds more quickly than liquid solvents [25].

Fundamental Principles of SFE

The Supercritical State

A substance reaches its supercritical state when heated and pressurized above its critical temperature (Tc) and critical pressure (Pc). At this point, the liquid and gas phases converge into a single fluid phase with hybrid properties [26]. The critical temperature is the highest temperature at which a gas can be liquefied by pressure, while the critical pressure is the minimum pressure required to liquefy a substance at its critical temperature [25].

Supercritical CO₂ possesses gas-like properties including high diffusivity and low viscosity, which allow it to rapidly penetrate porous solid matrices. Simultaneously, it exhibits liquid-like density and solvating power, enabling efficient dissolution of materials [25]. The absence of surface tension in supercritical fluids further enhances their ability to penetrate into small pores that are inaccessible to liquids [25].

Solvation Power and Tunability

The solvating power of supercritical fluids is directly related to their density, which can be precisely controlled by adjusting the system pressure and temperature [25]. This tunability is a key advantage of SFE, as it allows operators to selectively extract target compounds by creating specific conditions optimized for different compound classes.

For non-polar and weakly polar compounds such as lipids, essential oils, and terpenes, supercritical CO₂ provides excellent solvation without modification [24]. The extraction of polar compounds like polyphenols and flavonoids typically requires the addition of polar co-solvents such as ethanol or methanol to enhance solubility [27]. This adjustable selectivity enables the development of sophisticated extraction protocols that can target specific compound classes from complex matrices.

Table 1: Critical Parameters of Common Supercritical Fluids

| Fluid | Critical Temperature (°C) | Critical Pressure (MPa) | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide (CO₂) | 31.1 | 7.39 | Most widely used for natural product extraction |

| Water (H₂O) | 374.0 | 22.10 | Environmental remediation, waste treatment |

| Ethane (C₂H₆) | 32.2 | 4.88 | Specialty extractions |

| Propane (C₃H₈) | 96.7 | 4.25 | Lipid extraction |

| Ammonia (NH₃) | 132.5 | 11.40 | Specialty chemical processing |

Carbon Dioxide as a Supercritical Solvent

Properties and Advantages

Supercritical CO₂ (SC-CO₂) has become the solvent of choice for most SFE applications, particularly in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. Its widespread adoption stems from several advantageous properties. SC-CO₂ is non-toxic, non-flammable, and chemically inert, making it safe for processing products for human consumption [27]. The low critical temperature of 31.1°C allows for the extraction of thermolabile compounds without degradation [27]. CO₂ is also readily available in high purity at relatively low cost, and it can be easily recycled and reused within the extraction system [26].

From an environmental perspective, SC-CO₂ extraction eliminates the use of hazardous organic solvents such as hexane, chloroform, and methanol, which pose significant storage, disposal, and environmental concerns [25]. The extracts obtained are free of solvent residues, making them particularly valuable for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and food applications where purity is paramount [27]. Furthermore, the simple removal of CO₂ from the extract by depressurization eliminates the need for energy-intensive concentration steps typically required in conventional solvent extraction [27].

Comparison with Traditional Extraction Methods

When compared to traditional extraction methods like Soxhlet extraction or maceration, SFE with CO₂ offers significant advantages in efficiency, selectivity, and environmental impact. Research indicates that SFE can reduce solvent usage by 80-90% and lower energy requirements by 30-50% compared to conventional methods [24]. The extraction process is also faster due to the higher diffusion rates of supercritical fluids, with research showing that lipid extraction can reach more than 90% of the theoretical value in a short time [25].

The quality of SFE extracts is generally superior, with achieved purity of approximately 95% compared to 70-80% typically obtained with traditional solvent extraction methods [24]. This combination of efficiency and selectivity makes SFE particularly valuable for high-value bioactive compounds where preservation of biological activity and elimination of solvent residues are critical considerations.

Table 2: Comparison of SFE-CO₂ with Traditional Extraction Methods

| Parameter | SFE-CO₂ | Soxhlet Extraction | Maceration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Consumption | Reduced by 80-90% [24] | High | High |

| Energy Requirements | 30-50% lower [24] | High | Moderate |

| Extraction Time | Short (minutes to hours) | Long (hours to days) | Very long (days) |

| Extract Purity | ~95% [24] | 70-80% [24] | 60-75% |

| Solvent Residues | None | Potential residues | Potential residues |

| Thermolabile Compound Preservation | Excellent | Poor | Good |

| Selectivity | Tunable | Limited | Limited |

| Environmental Impact | Low | High | Moderate |

Key Operational Parameters in SFE

The efficiency and selectivity of SFE processes are governed by several interconnected operational parameters that must be optimized for each specific application and raw material.

Pressure and Temperature

Pressure is the most influential parameter in SFE, as it directly controls the density and solvating power of the supercritical fluid [25]. Increasing pressure enhances the solubility of most compounds in SC-CO₂, particularly lipids and non-polar compounds. Studies have demonstrated that extraction yields can increase significantly with pressure, from 3.63 to 18.63 g CO₂ kg⁻¹ when pressure increases from 20 to 60 MPa [25]. The temperature influence is more complex, as it affects both the fluid density and the vapor pressure of the target compounds. Higher temperatures can increase solubility for some compounds while decreasing it for others [25].

The optimal combination of pressure and temperature depends on the specific compounds being targeted. For most lipid and wax extractions, higher pressures (25-50 MPa) and moderate temperatures (40-60°C) are typically employed. For more volatile compounds, lower pressures and temperatures may be preferable to maintain selectivity and prevent co-extraction of unwanted components.

Co-solvents and Modifiers

While pure SC-CO₂ is excellent for non-polar compounds, its ability to dissolve polar molecules is limited. The incorporation of co-solvents (typically 1-15% by volume) significantly enhances the extraction efficiency for polar bioactive compounds [27]. Ethanol is the most commonly used co-solvent in food and pharmaceutical applications due to its safety profile and GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status [27]. Methanol, acetone, and water are also used in specific applications, though their use is more restricted in products for human consumption.

Co-solvents function by modifying the polarity of the supercritical fluid and through specific molecular interactions with target compounds. They can also reduce the required operating pressure and temperature, thereby improving the overall energy efficiency of the process [27]. However, co-solvent selection and concentration must be carefully optimized, as excessive amounts can lead to swelling of plant material or undesirable changes in extract composition [27].

Particle Size and Matrix Preparation

The physical characteristics of the raw material significantly impact SFE efficiency. Reducing particle size increases the surface area available for extraction, while appropriate moisture content is crucial for optimal mass transfer [25]. Excessive moisture can reduce extraction efficiency by creating barriers between the solvent and target compounds, while completely dry matrices may exhibit reduced permeability [25].

Various pretreatment methods can enhance SFE efficiency, including drying, grinding, flaking, and enzymatic or mechanical destructuring [25]. These treatments improve mass transfer by increasing the exchange surface and disrupting cellular structures that contain the target compounds [25]. The optimal particle size represents a balance between increased surface area and potential channeling effects in the extraction bed, typically ranging from 0.25 to 1.5 mm for most plant materials.

Table 3: Optimization of Key SFE Parameters for Different Compound Classes

| Parameter | Lipids & Fixed Oils | Essential Oils & Terpenes | Polar Phenolics | Antioxidants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure Range | 25-50 MPa | 8-20 MPa | 20-35 MPa | 15-30 MPa |

| Temperature Range | 40-60°C | 35-50°C | 45-60°C | 40-55°C |

| Co-solvent Requirements | None typically | None typically | Ethanol 5-15% | Ethanol 5-10% |

| Particle Size | 0.3-0.8 mm | 0.5-1.5 mm | 0.2-0.7 mm | 0.3-0.8 mm |

| Moisture Content | <10% | <12% | 5-15% | 5-12% |

| Extraction Time | 1-4 hours | 0.5-2 hours | 1-3 hours | 1-3 hours |

Applications in Bioactive Compound Extraction

SFE with CO₂ has found diverse applications in the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials, contributing significantly to the valorization of agricultural by-products and the development of high-value nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals.

Extraction from Agri-Food By-products

The valorization of agri-food by-products represents a major application area for SFE, aligning with circular economy principles by converting waste streams into value-added products [24]. Global food loss and waste amounts to approximately 1.3 billion tons annually, creating significant environmental and economic challenges [24]. SFE offers an efficient approach to recover bioactive compounds from various plant-based residues, including grape pomace, citrus peels, cereal brans, and other processing by-products [28].

Grape pomace, a by-product of winemaking, contains valuable polyphenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins that can be efficiently extracted using SFE with ethanol as a co-solvent [28]. Similarly, citrus peels are rich sources of flavonoids and essential oils, while tomato processing by-products contain significant amounts of carotenoids like lycopene [28]. The extraction of these compounds not only generates high-value products but also reduces the environmental impact of agricultural waste.

Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Applications

In the pharmaceutical industry, SFE with CO₂ is extensively used for the extraction of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from natural sources, including plants, herbs, and marine organisms [26]. The technique is particularly valuable for extracting thermolabile compounds that would degrade under conventional extraction conditions. Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC), a complementary technology, is also gaining traction for the separation and analysis of pharmaceutical compounds with high efficiency and resolution [26].

The nutraceutical industry benefits from SFE's ability to produce solvent-free extracts with preserved biological activity. Bioactive compounds such as antioxidants, anti-inflammatory agents, and metabolic regulators obtained through SFE can be directly incorporated into functional foods and dietary supplements without concerns about solvent residues [28]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that these extracts maintain their efficacy, supporting various health benefits including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, metabolic-regulating, and prebiotic effects [28].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure for SFE of Bioactive Compounds

Protocol Objective: To provide a standardized method for the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials using supercritical CO₂.

Materials and Equipment:

- SFE system with high-pressure pump, extraction vessel, and separation units

- Liquid CO₂ source with dip tube

- Co-solvent reservoir and pump (if required)

- Plant material (properly prepared)

- Collection vials for extracts

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g precision)

- Temperature and pressure monitoring equipment

Sample Preparation:

- Raw Material Selection: Select appropriate plant material based on target compounds.

- Drying: Reduce moisture content to optimal level (typically 5-12%) using appropriate drying methods.

- Size Reduction: Grind material to particle size of 0.25-1.0 mm using appropriate milling equipment.

- Loading: Weigh exact amount of prepared material (typically 80-100 g for lab-scale systems) and load into extraction vessel.