Multi-Sensor vs. Single-Sensor Eating Detection: A Comprehensive Review of Accuracy and Applications in Biomedical Research

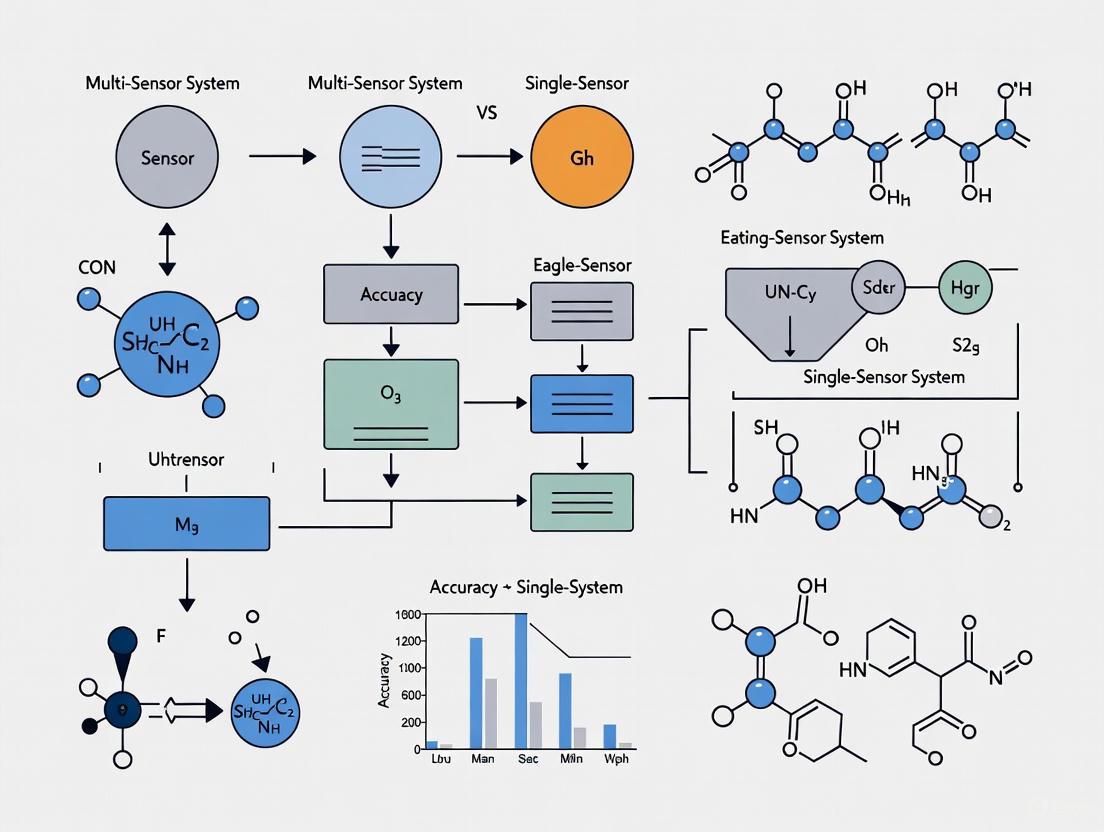

This article systematically evaluates the performance of multi-sensor versus single-sensor approaches for eating detection, a critical technology for dietary monitoring in clinical and research settings.

Multi-Sensor vs. Single-Sensor Eating Detection: A Comprehensive Review of Accuracy and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article systematically evaluates the performance of multi-sensor versus single-sensor approaches for eating detection, a critical technology for dietary monitoring in clinical and research settings. We explore the foundational principles of sensor technologies, including acoustic, motion, imaging, and inertial sensors, and detail methodological frameworks for data fusion. The review analyzes common challenges such as false positives, data variability, and real-world deployment issues, presenting optimization strategies. A comparative validation assesses the accuracy, sensitivity, and precision of different sensor configurations, highlighting significant performance improvements achieved through multi-sensor fusion. This synthesis provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based guidance for selecting and implementing eating detection technologies to enhance dietary assessment and intervention efficacy.

The Science of Eating Detection: Core Principles and Sensor Technologies

The accurate detection and characterization of eating episodes represent a critical frontier in health monitoring and nutritional science. Within the context of a broader thesis examining multi-sensor versus single-sensor approaches, this guide objectively compares the performance of various eating detection methodologies. Traditional dietary assessment through self-reporting suffers from significant limitations, including recall bias and imprecision [1]. Wearable sensor technologies have emerged as promising alternatives, capable of detecting eating episodes through physiological and behavioral signatures such as chewing, swallowing, and hand-to-mouth gestures [2] [3]. These technologies can be broadly categorized into single-modality systems, which rely on one type of sensory input, and multi-sensor approaches that fuse complementary data streams [4].

The fundamental challenge in eating detection lies in the complex nature of eating behavior itself, which encompasses both distinct physiological processes (chewing, swallowing) and contextual factors (food type, eating environment) [1]. This complexity has driven research toward increasingly sophisticated detection metrics and sensor fusion strategies. This comparison guide evaluates the performance of various approaches using published experimental data, detailing methodological protocols, and providing implementation resources for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of nutrition science and biomedical technology.

Performance Comparison of Eating Detection Modalities

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Single-Sensor Eating Detection Approaches

| Detection Modality | Specific Sensor Type | Primary Metric(s) | Reported Performance | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic (Chewing Sounds) | In-ear Microphone [5] | Food Identification Accuracy | 99.28% (GRU model) [5] | 20 food items, 1200 audio files |

| Acoustic (Swallowing) | Throat Microphone [6] | Drinking Activity F1-score | 72.09% recall [6] | Fluid intake identification |

| Motion (Hand Gestures) | Wrist-worn IMU [7] | Meal Detection F1-score | 87.3% [7] | 28 participants, 3-week deployment |

| Motion (Jaw Movement) | Piezoelectric Sensor [2] | Food Intake Detection Accuracy | 89.8% [2] | 12 participants, 24-hour free-living |

| Motion (Hand Gestures) | Smartwatch Accelerometer [8] | Carbohydrate Intake Detection F1-score | 0.99 (median) [8] | Personalized model for diabetics |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Sensor Fusion Approaches

| System Name | Sensors Fused | Fusion Method | Performance Metrics | Study Context / Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeckSense [9] | Proximity, Ambient Light, IMU | Feature-level fusion & clustering | F1-score: 81.6% (semi-free-living), 77.1% (free-living) [9] | 20 participants with diverse BMI; 8% improvement over proximity sensor alone |

| AIM [2] | Jaw Motion, Hand Gesture, Accelerometer | Artificial Neural Networks | 89.8% accuracy [2] | 12 subjects, 24-hour free-living; no subject input required |

| Multimodal Drinking Identification [6] | Wrist IMU, Container IMU, In-ear Microphone | Machine Learning (SVM, XGBoost) | F1-score: 83.9%-96.5% [6] | Outperformed single-modal approaches (20 participants) |

| Covariance Fusion [4] | Accelerometer, BVP, EDA, Temperature, HR | 2D Covariance Representation + Deep Learning | Precision: 0.803 (LOSO-CV) [4] | Transforms multi-sensor data into 2D representation for efficient classification |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Audio-Based Food Recognition Using Deep Learning

The high-accuracy food recognition system detailed in [5] followed a rigorous data acquisition and processing protocol. Researchers collected 1200 audio files encompassing 20 distinct food items. The key to their success lay in sophisticated feature extraction from the audio signals:

- Signal Processing: Audio files were processed to generate mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), which effectively capture the timbral and textural aspects of sound critical for distinguishing different food textures.

- Supplementary Features: The team additionally extracted spectrograms (visual representations of signal strength), spectral rolloff (measuring signal shape), and spectral bandwidth (representing lower and upper frequencies) to provide complementary acoustic information.

- Model Training: Multiple deep learning architectures were trained and compared, including Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, InceptionResNetV2, and several hybrid models (e.g., Bidirectional LSTM + GRU). The GRU model achieved the highest accuracy at 99.28%, demonstrating the viability of audio-based classification for food identification [5].

Multi-Sensor Fusion for Free-Living Eating Detection

The NeckSense system [9] and Automatic Ingestion Monitor (AIM) [2] represent comprehensive approaches to eating detection in uncontrolled environments. Their experimental methodologies share common strengths:

- Sensor Configuration: NeckSense integrated a proximity sensor (to detect chin movement), ambient light sensor, and an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) to capture leaning forward angles and general motion [9]. AIM combined a jaw motion sensor (placed below the earlobe), a hand gesture sensor (wrist-worn proximity sensor), and a body accelerometer [2].

- Data Collection Protocols: Both systems were validated in extended free-living studies. NeckSense collected over 470 hours of data from 20 participants with diverse BMI profiles [9]. AIM involved 12 subjects wearing the system for 24-hour periods without restricting their daily activities or food intake [2].

- Algorithmic Processing: NeckSense applied a longest periodic subsequence algorithm to identify chewing sequences from the proximity sensor, then augmented this with other sensor data to improve detection [9]. AIM employed Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to fuse the sensor inputs and detect eating episodes without requiring individual calibration [2].

Covariance-Based Multi-Sensor Fusion Technique

A novel fusion methodology described in [4] transformed multi-sensor data into a unified 2D representation to facilitate efficient classification:

- Data Matrix Formation: Sensor readings from multiple sources (e.g., accelerometer, photoplethysmograph, electrodermal activity) were organized into an observation matrix.

- Covariance Calculation: Pairwise covariance was computed between each signal across all samples, creating a covariance matrix that captured the statistical relationships between different sensor modalities.

- Contour Plot Generation: The covariance matrix was visualized as a filled contour plot, effectively encoding the inter-modality correlation patterns into a 2D color image.

- Deep Learning Classification: These contour representations were used as input to a deep residual network, which learned to identify patterns specific to eating episodes versus other activities, achieving a precision of 0.803 in leave-one-subject-out cross-validation [4].

The workflow of this covariance-based fusion approach is summarized in the diagram below.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Eating Detection

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Eating Detection Studies

| Tool / Solution | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-ear Microphone [5] | Acoustic Sensor | Captures high-fidelity chewing and swallowing sounds | Food type classification based on eating sounds [5] |

| Piezoelectric Jaw Sensor [2] | Motion Sensor | Monitors characteristic jaw motion during chewing | Food intake detection in free-living conditions [2] |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) [6] | Motion Sensor | Tracks hand-to-mouth gestures and eating-related movements | Drinking activity identification from wrist motion [6] |

| Proximity Sensor [9] | Distance Sensor | Detects repetitive chin movements during chewing | Eating episode detection in NeckSense system [9] |

| Covariance Fusion Algorithm [4] | Computational Method | Combines multi-sensor data into a unified 2D representation | Dimensionality reduction for efficient activity recognition [4] |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (GRU/LSTM) [5] [8] | Machine Learning Model | Learns temporal patterns in sensor data sequences | Personalized food consumption detection [8] |

Discussion and Implementation Considerations

The experimental data reveals a consistent performance advantage for multi-sensor approaches, particularly in challenging free-living environments. The 8% performance improvement demonstrated by NeckSense over its single-sensor baseline [9], and the superior F1-scores of multi-modal drinking identification [6] provide compelling evidence for the fusion paradigm. This advantage stems from the complementary nature of different sensing modalities: motion sensors capture gestural components, acoustic sensors detect mastication and swallowing, and proximity/light sensors provide contextual validation.

For researchers implementing these systems, several practical considerations emerge:

- Computational Efficiency vs. Performance: The covariance fusion method [4] offers an innovative compromise, transforming multi-dimensional sensor data into computationally efficient 2D representations while maintaining classification accuracy.

- Personalization Requirements: Some swallowing-based methodologies require individual calibration due to the uniqueness of swallowing sounds [2], while jaw motion-based approaches can implement group models that eliminate this need.

- Sensor Placement and User Burden: Systems like AIM [2] require multiple sensor placements (jaw, wrist, body), which may affect user compliance compared to single-device solutions like smartwatch-based detection [7].

The evolution of eating detection metrics from simple chewing counting to sophisticated food type classification reflects the field's increasing maturity. Future directions likely include further refinement of deep learning architectures, exploration of novel sensing modalities, and greater emphasis on real-world deployment challenges including battery life, user privacy, and long-term wearability [10] [3].

Sensor selection is a critical determinant of performance in research applications, particularly in fields like automated eating behavior monitoring. Within the context of a broader thesis on multi-sensor versus single-sensor eating detection accuracy, understanding the inherent capabilities and limitations of individual sensing modalities is foundational. Single-sensor systems often provide the basis for development, offering insights into specific physiological or physical correlates of behavior before their integration into more complex, multi-sensor frameworks.

This guide provides a structured taxonomy and quantitative comparison of four primary single-sensor modalities: Acoustic, Motion, Strain, and Imaging sensors. By objectively analyzing the performance, experimental protocols, and intrinsic characteristics of each, this document serves as a reference for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals designing studies or evaluating technologies, especially in health monitoring and behavioral analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of Sensor Modalities

A sensory modality is an identifiable class of sensation based on the type of energy transduced by the receptor. The fundamental principle governing sensor performance is the adequate stimulus—the specific form of energy to which a sensor responds with the lowest threshold [11]. For instance, an acoustic sensor is adequately stimulated by sound waves, while a motion sensor is adequately stimulated by acceleration.

The quality of sensory information is encoded through labeled line coding, where the anatomical pathway from the sensor to the processing unit determines the perceived modality [11]. This is why stimulating a pressure sensor, even with non-mechanical energy, may still be interpreted by the system as a pressure signal. The intensity of information, on the other hand, is typically encoded through frequency coding, where a stronger stimulus leads to a higher rate of signal generation [11].

In application design, the Principle of Display Suitability dictates that the sensor modality must be matched to the information being conveyed [11]. For example, audition has an advantage over vision in vigilance-type warnings due to its attention-getting qualities. The table below outlines general selection criteria, which can be adapted for sensing—rather than displaying—information.

Table: Sensory Modality Selection Guidelines (Adapted from [11])

| Use an Auditory (Acoustic) Sensor if... | Use a Visual (Imaging) Sensor if... |

|---|---|

| The event is simple and short. | The event is complex and long. |

| The event deals with occurrences in time. | The event deals with location in space. |

| The event calls for immediate action. | The event does not call for immediate action. |

| The visual system is overburdened. | The auditory system is overburdened. |

Taxonomy and Performance Comparison of Sensor Modalities

The following sections detail the operating principles, key performance characteristics, and experimental data for each of the four sensor modalities.

Acoustic Sensors

Principle of Operation: Acoustic sensors detect sound waves, vibrations, and other acoustic signals, converting them into measurable electrical signals. In biomedical applications, they often function as microphones that capture internal body sounds or vibrations [12] [13].

Experimental Protocol for Pulse Wave Analysis: A 2025 study quantitatively compared acoustic sensors against optical and pressure sensors for cardiovascular pulse wave measurement [12]. Signals were recorded sequentially from the radial artery of 30 participants using the three sensors. Each recording lasted 2 minutes in a controlled environment. The acoustic sensor specifically utilized an electret condenser microphone as the pulse deflection sensing element, converting vibrations from pulse signals into electrical signals via the microphone's diaphragm [12]. Performance was evaluated using time-domain, frequency-domain, and Pulse Rate Variability (PRV) measures.

Table: Performance of Acoustic Sensors in Pulse Wave Analysis [12]

| Performance Metric | Acoustic Sensor Findings |

|---|---|

| Time & Frequency Domain Features | Varied significantly compared to optical and pressure sensors. |

| Pulse Rate Variability (PRV) | No statistical differences found in PRV measures across sensor types (ANOVA). |

| Overall Performance | Pressure sensor performed best; acoustic sensor performance was context-dependent. |

Motion Sensors

Principle of Operation: Motion sensors, typically Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) containing accelerometers and gyroscopes, measure the linear and angular motion of a body. In eating detection, they are used to capture characteristic hand-to-mouth movements [7].

Experimental Protocol for Eating Detection: A real-time eating detection system was deployed using a smartwatch's three-axis accelerometer worn on the dominant hand [7]. The system processed data through a machine learning pipeline. A 50% overlapping 6-second sliding window was used to extract statistical features (mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis, and root mean square) along each axis. A random forest classifier was trained to predict hand-to-mouth movements, and a meal episode was declared upon detecting 20 such gestures within a 15-minute window [7]. This passive detection system triggered Ecological Momentary Assessments (EMAs) to gather self-reported contextual data.

Table: Performance of Motion Sensors in Eating Detection [7]

| Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|

| Meal Detection Rate (Overall) | 96.48% (1259/1305 meals) |

| Breakfast Detection Rate | 89.8% (264/294 meals) |

| Lunch Detection Rate | 99.0% (406/410 meals) |

| Dinner Detection Rate | 98.0% (589/601 meals) |

| Classifier Precision | 80% |

| Classifier Recall | 96% |

| Classifier F1-score | 87.3% |

Strain Sensors

Principle of Operation: Strain sensors measure mechanical deformation (strain) and convert it into a change in electrical resistance, capacitance, or optical signal. Long-gauge fiber optic sensors, a prominent type, measure strain over a defined base length, making them suitable for monitoring distributed deformation in structures or body surfaces [14].

Experimental Protocol for Structural Monitoring: A 2025 study compared long-gauge fiber optic sensors against traditional tools for monitoring Reinforced Concrete (RC) columns [14]. The evaluation used four methods: surface-mounted optic sensors, embedded optic sensors, Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDTs), and point-sensor strain gauges. The fiber optic sensors operated on the Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) principle, where strain changes (Δε) cause a shift in the Bragg wavelength (Δλ) according to the equation: Δλ/λ = k·Δε, where k is the Bragg grating factor [14]. Their performance was assessed based on stability and precision in measuring small deformations.

Table: Performance of Long-Gauge Fiber Optic Strain Sensors [14]

| Performance Metric | Finding |

|---|---|

| Deformation Measurement | Accurately measured both large and small deformations. |

| Comparison to LVDTs | Outperformed LVDTs in accuracy. |

| Comparison to Strain Gauges | Demonstrated superior average strain measurement. |

| Robustness | Minimal interference from protective covers when embedded. |

Imaging Sensors

Principle of Operation: Imaging sensors detect and convert light into electronic signals. Emerging technologies extend beyond standard CMOS detectors, enabling capabilities like hyperspectral imaging (which captures a full spectrum per pixel) and event-based vision (which reports pixel-level changes with timestamps) [15]. Optical tracking sensors are a specialized subtype that measure relative movement on a surface, such as facial skin [16].

Experimental Protocol for Eating Behavior Monitoring: A 2024 study investigated optical tracking sensors (OCO sensors) embedded in smart glasses for monitoring eating and chewing activities [16]. These optomyography sensors measure 2D skin movements resulting from underlying muscle activations. Data was collected from sensors on the cheeks (monitoring zygomaticus muscles) and temples (monitoring temporalis muscle) during eating, speaking, and teeth clenching in both laboratory and real-life settings. A Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM) deep learning model analyzed the temporal sensor data to distinguish chewing from other facial activities [16].

Table: Performance of Optical Imaging Sensors for Chewing Detection [16]

| Performance Metric | Laboratory Setting | Real-Life Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Performance Score | F1-score: 0.91 | Precision: 0.95, Recall: 0.82 |

| Sensor Data Sensitivity | Statistically significant differences (P<.001) between eating, clenching, and speaking. | Not Reported |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy in controlled conditions. | Effective granular chewing detection in natural environments. |

Integrated Analysis and Experimental Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and performance outcomes for the key experiments cited in this guide, highlighting the pathway from data collection to quantitative results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Materials and Equipment for Sensor-Based Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Representative Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Smartwatch with IMU | Provides a commercial, wearable platform for motion data capture using accelerometers and gyroscopes. | Capturing dominant hand movements for eating detection [7]. |

| OCO Optical Tracking Sensors | Non-contact optical sensors that measure 2D skin movement (optomyography) from underlying muscle activations. | Monitoring temporalis and zygomaticus muscle activity for chewing detection in smart glasses [16]. |

| Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) Sensors | Long-gauge fiber optic sensors that transduce mechanical strain into a shift in reflected light wavelength. | Distributed strain measurement on structural surfaces or for biomechanical monitoring [14]. |

| Electret Condenser Microphone | An acoustic sensor that converts mechanical vibrations (e.g., from an arterial pulse wave) into electrical signals. | Capturing pulse wave signals from the radial artery for cardiovascular analysis [12]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | A machine learning algorithm used for classification tasks, such as identifying eating gestures from sensor data. | Classifying 6-second windows of accelerometer data as "eating" or "non-eating" [7]. |

| Convolutional LSTM (ConvLSTM) Model | A deep learning model combining convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. | Analyzing spatio-temporal data from optical sensors for precise chewing segment detection [16]. |

This taxonomy delineates the core characteristics and performance benchmarks of four fundamental sensor modalities. The experimental data demonstrates that each sensor type possesses inherent strengths; motion sensors excel at detecting gross motor activities like hand-to-mouth movements, optical sensors can capture subtle, localized muscle activity for granular behavior analysis like chewing, acoustic sensors capture vibratory signatures, and strain sensors provide precise mechanical deformation tracking.

The choice of a single-sensor modality is therefore dictated by the specific physiological correlate of interest. This foundational understanding is a critical prerequisite for designing sophisticated multi-sensor fusion systems. The pursuit of higher accuracy in complex detection tasks, such as comprehensive eating behavior analysis, logically progresses from optimizing single-sensor models to integrating their complementary data streams, thereby overcoming the limitations inherent in any single modality.

Accurate and reliable monitoring of dietary intake is a cornerstone of nutritional science, chronic disease management, and public health research. Traditional methods, such as self-reported food diaries and 24-hour recalls, are plagued by significant limitations, including participant burden and substantial recall bias, leading to inaccuracies in data collection [17]. The emergence of wearable sensor technology presents a promising solution, offering objective, continuous data collection in real-world settings [17]. These sensor-based systems can detect a range of eating-related events, from hand-to-mouth gestures to chewing and swallowing sounds [1]. However, a critical division exists in their implementation: the use of single-sensor systems versus multi-sensor fusion approaches.

This guide objectively compares the performance of single-sensor systems against multi-sensor alternatives, framing the discussion within the broader thesis that multi-sensor data fusion is essential for achieving the accuracy and reliability required for rigorous scientific and clinical applications. While single-sensor systems offer simplicity and lower computational cost, the evidence demonstrates they face inherent limitations in accuracy, robustness, and generalizability across diverse real-world conditions [1] [18]. This article will dissect these limitations through structured performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and an analysis of the technological gaps that hinder their standalone use.

Performance Comparison: Single- vs. Multi-Sensor Systems

The performance gap between single-sensor and multi-sensor systems can be quantified across several key metrics, including detection accuracy, robustness in free-living environments, and the ability to characterize complex eating behaviors.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Sensor Modalities for Eating Behavior Monitoring

| Sensor Modality | Primary Measured Parameter | Reported Accuracy/F1-Score (Single-Sensor) | Key Limitations (Single-Sensor) | Performance Improvement with Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Hand-to-mouth gestures, wrist motion [1] [8] | F1-score up to 0.99 (controlled lab) [8] | Cannot distinguish eating from other similar gestures (e.g., drinking, face-touching) [1] | Improved specificity by combining with acoustic data to reject non-eating gestures |

| Acoustic Sensor | Chewing and swallowing sounds [17] [1] | High accuracy in lab; significantly lower in free-living [1] | Highly susceptible to ambient noise; privacy concerns [1] | Audio and motion data fusion enhances noise resilience and event classification |

| Optical Tracking (Smart Glasses) | Facial muscle and skin movement [16] | F1-score of 0.91 (chewing detection in lab) [16] | Performance can be affected by speaking, clenching, or improper fit [16] | Data from multiple facial sensors (cheek, temple) combined to improve activity discrimination |

| Image-based (Camera) | Food type, volume, context [17] [1] | Effective for food identification; limited for continuous intake tracking [1] | Obtrusive; raises privacy issues; ineffective in low-light or when food is occluded [1] | Provides ground truth for context, fused with continuous sensors for intake timing |

Table 2: Impact of Environment on Single-Sensor System Reliability

| Performance Metric | Controlled Laboratory Setting | Free-Living (Real-World) Setting | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Accuracy | High (e.g., >90% F1-score) [8] [16] | Significantly Lower and Highly Variable [1] | Controlled vs. unpredictable ambient noise and user activities |

| Participant Compliance | High (short duration, direct supervision) | Moderate to Low (long-term wear, comfort issues) [19] | Device intrusiveness and burden of continuous use [17] |

| Data Completeness | High (minimal data loss) | Often Incomplete (e.g., due to device removal for charging) [19] | Battery life limitations and user forgetfulness in real-life routines |

Experimental data underscores the quantitative benefit of fusion. A study on food spoilage monitoring demonstrated that fusing Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy with Multispectral Imaging (MSI) data improved the prediction accuracy of bacterial counts by up to 15% compared to single-sensor models [18]. This principle translates directly to eating behavior monitoring, where a system relying solely on an IMU may misinterpret a hand-to-mouth gesture, but when fused with an acoustic sensor that detects the absence of chewing sounds, can correctly classify it as a non-eating event.

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Comparison

To objectively evaluate and compare sensor systems, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols. The following details a typical workflow for assessing the performance of eating detection sensors, from data collection to model evaluation.

Detailed Methodology

The workflow above outlines the key stages of a robust validation experiment:

Protocol Design: Studies should be structured using frameworks like PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design) to define clear research questions and eligibility criteria [17]. This involves recruiting a participant population that reflects the target application (e.g., healthy adults, patients with specific conditions) and defining the experimental interventions (e.g., consuming a standardized meal versus engaging in non-eating activities).

Data Collection:

- Controlled Laboratory Setting: Participants perform scripted activities, including eating specific foods and performing confounding actions (e.g., speaking, walking, gesturing). Sensor data is synchronized with ground truth video recording or researcher annotations [16]. For example, a study using smart glasses with optical sensors collected data from participants eating, speaking, and clenching their teeth in a lab to establish a baseline model [16].

- Free-Living Setting: Participants wear the sensor system in their normal environment over hours or days. Ground truth is typically established through self-reporting (e.g., meal logs) or contextual cues [16]. This phase is critical for assessing real-world reliability.

Data Preprocessing & Feature Extraction: Raw sensor data is cleaned (e.g., filtering noise) and segmented. Feature extraction is then performed on these segments. For an IMU, this might include mean acceleration, signal magnitude area, and spectral energy. For acoustic sensors, features like Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) are common [1].

Model Training & Evaluation: Machine learning models (from traditional classifiers to deep learning networks) are trained on the extracted features. A common approach for temporal data is the Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM) model, which has been used to analyze optical sensor data from smart glasses for chewing detection [16]. Models are evaluated using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score through cross-validation [17] [8].

Performance Validation: The final step involves validating the model's performance on a held-out test set, particularly from the free-living study, to assess its generalizability and robustness outside the controlled lab environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing and testing sensor systems for eating detection requires a suite of specialized tools and methodologies. The following table details essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Sensor-Based Eating Detection

| Item/Solution | Function/Description | Example Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Measures linear acceleration (accelerometer) and angular velocity (gyroscope). | Tracking wrist and arm movement to detect bites via hand-to-mouth gestures [1] [8]. |

| Acoustic Sensor (Microphone) | Captures audio signals from the user's environment or body. | Detecting characteristic sounds of chewing and swallowing [17] [1]. |

| Optical Tracking Sensor (OCO Sensor) | Measures 2D relative movements of the skin surface using optomyography [16]. | Integrated into smart glasses to monitor activations of temporalis and cheek muscles during chewing [16]. |

| Reference Method (Ground Truth) | Provides a benchmark for validating sensor data. | Video recording in lab studies; detailed food and activity diaries in free-living studies [17] [16]. |

| Data Fusion Architecture | A framework for combining data from multiple sensors. | Early (data-level), mid-level (feature-level), or late (decision-level) fusion to improve detection accuracy and robustness [18]. |

| Deep Learning Models (e.g., ConvLSTM) | AI models for analyzing complex, sequential sensor data. | Classifying temporal patterns of optical and IMU data to distinguish chewing from other facial activities [16]. |

Technological Gaps and Standardization Challenges

The limitations of single-sensor systems are compounded by broader technological and standardization gaps in the field of digital phenotyping.

The diagram above illustrates the interconnected challenges. A primary technical hurdle is battery life. Continuous operation of power-intensive sensors like microphones or high-sample-rate IMUs leads to rapid battery drainage, forcing users to remove devices for charging and resulting in incomplete data [19]. This is a major threat to reliability in long-term studies.

Furthermore, a lack of standardization creates significant barriers. The field suffers from:

- Device and OS Fragmentation: The heterogeneity of wearable devices and operating systems leads to inconsistencies in data quality and format, making it difficult to compare results across studies or aggregate data [19].

- Proprietary Ecosystems and Data Silos: Many commercial wearables operate within closed ecosystems, using proprietary algorithms to process sensor data. This limits researchers' access to raw data and transparency, hindering independent validation and scientific advancement [19].

- Absence of Universal Protocols: There are no universally accepted protocols for data collection, processing, or reporting in eating behavior monitoring. This lack of standardization limits the reproducibility and generalizability of findings, as results from one single-sensor system may not translate to another [17] [19].

Finally, a critical gap is the inability of single-sensor systems to generalize. Models often achieve high performance in controlled laboratory settings but experience a significant drop in accuracy when deployed in the real world. This is because a single data stream is insufficient to cope with the vast variability of free-living environments, including diverse user behaviors, different food textures, and unpredictable ambient noise [1].

The evidence clearly demonstrates that while single-sensor systems provide a valuable foundation for automated dietary monitoring, they possess inherent limitations in accuracy, reliability, and generalizability that restrict their utility for rigorous research and clinical applications. Their limited observational scope makes them susceptible to errors of misclassification, while technical challenges like battery life and a lack of standardized protocols further undermine their reliability in the free-living settings where they are most needed.

The path forward lies in the strategic adoption of multi-sensor fusion approaches. By integrating complementary data streams—such as motion, sound, and images—these systems can overcome the blind spots of any single modality. Future research must focus on developing energy-efficient sensing hardware, standardized data fusion frameworks, and robust machine learning models trained on diverse, real-world datasets. For the research and drug development community, investing in multi-modal systems is not merely an optimization but a necessity for generating the high-fidelity, reliable data required to understand the complex role of diet in health and disease.

In the precise field of behavioral monitoring, particularly for eating detection, single-sensor systems often struggle to achieve the accuracy and reliability required for scientific and clinical applications. These systems are inherently limited by their operational principles; for instance, motion sensors can be confused by gestures that mimic eating, such as pushing glasses or scratching the neck, while acoustic sensors may struggle to distinguish between swallowing water and swallowing saliva [6]. Similarly, camera-based systems can generate false positives by identifying food present in the environment but not consumed by the user [20]. These limitations underscore a critical need for more robust sensing paradigms. Multi-sensor fusion emerges as a powerful solution, integrating complementary data streams to construct a more complete and reliable picture of behavior. This guide objectively compares the performance of single-sensor versus multi-sensor systems, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed to inform their study designs.

Theoretical Foundations: How Multi-Sensor Fusion Works

Multi-sensor fusion enhances observational capabilities by combining complementary data streams to overcome the limitations of individual sensors. The theoretical foundation lies in leveraging conditional independence or conditional correlation among sensors to improve overall representation power [21]. Fusion strategies are typically implemented at three distinct levels of data abstraction, each with its own advantages.

Fusion Architecture and Levels

The following diagram illustrates the three primary fusion levels and their workflow in a behavioral monitoring context.

Early Fusion combines raw data from different sensors before feature extraction, preserving maximum information but requiring careful handling of synchronization and data alignment [21] [18]. Mid-Level Fusion extracts features from each sensor first, then merges these feature vectors before final classification, offering a balance between data preservation and manageability [18]. Late Fusion operates by combining decisions from independently trained sensor-specific classifiers, often through weighting or meta-learning, providing system flexibility and ease of implementation [18] [6].

Experimental Comparison: Single-Sensor vs. Multi-Sensor Performance

Drinking Activity Identification Study

A rigorous 2024 study directly compared single-modal and multi-sensor fusion approaches for drinking activity identification, employing wrist-worn inertial measurement units (IMUs), a sensor-equipped container, and an in-ear microphone [6]. The experimental protocol was designed to challenge the systems with realistic scenarios, including eight drinking situations (varying by posture, hand used, and sip size) and seventeen confounding non-drinking activities like eating, pushing glasses, and scratching necks.

The methodology involved data acquisition from twenty participants, followed by signal pre-processing using a sliding window approach and feature extraction. Typical machine learning classifiers including Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) were trained and evaluated using both sample-based and event-based metrics. The quantitative results demonstrate the clear advantage of fusion:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Drinking Activity Identification Methods [6]

| Sensor Modality | Classifier | Sample-Based F1-Score | Event-Based F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist IMU Only | SVM | 76.3% | 90.2% |

| Container Sensor Only | SVM | 79.1% | 92.8% |

| In-Ear Microphone Only | SVM | 74.6% | 88.5% |

| Multi-Sensor Fusion | SVM | 83.7% | 96.5% |

| Multi-Sensor Fusion | XGBoost | 83.9% | 95.8% |

The multi-sensor fusion approach using an SVM classifier achieved a 96.5% F1-score in event-based evaluation, significantly outperforming all single-modality configurations. This demonstrates that fusion effectively leverages complementary information—where one sensor modality might be confused by a similar-looking motion, another modality (e.g., acoustic) provides disambiguating evidence.

Free-Living Food Intake Detection Study

A 2024 study on food intake detection in free-living conditions further validates the performance gains from multi-sensor fusion [20]. Researchers used the Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2 (AIM-2), a wearable system that includes a camera and a 3D accelerometer to detect chewing. The study involved 30 participants in pseudo-free-living and free-living environments, collecting over 380 hours of data.

The methodology involved three parallel detection methods: image-based recognition of solid foods and beverages, sensor-based detection of chewing from accelerometer data, and a hierarchical classifier that fused confidence scores from both image and sensor classifiers. The integrated approach was designed to reduce the false-positive rates inherent in each individual method.

Table 2: Performance of Food Intake Detection in Free-Living Conditions [20]

| Detection Method | Sensitivity | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image-Based Only | 86.4% | 82.1% | 84.2% |

| Sensor-Based Only | 88.7% | 79.5% | 83.9% |

| Integrated Fusion | 94.59% | 70.47% | 80.77% |

The results show that the integrated fusion method achieved a significant 8% improvement in sensitivity over the image-based method alone. While precision saw a decrease, the overall F1-score—a balance of precision and sensitivity—remained superior. This demonstrates fusion's key strength: capturing a more complete set of true eating episodes, which is critical in clinical and research settings where missing data (false negatives) can be more problematic than false alarms.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing a multi-sensor fusion study for eating or drinking detection requires a specific set of hardware and software components. The table below details key research reagent solutions and their functions based on the cited experimental setups.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Multi-Sensor Eating/Drinking Detection Studies

| Item Name | Type/Model Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Opal Sensor (APDM) | Captures triaxial acceleration and angular velocity to detect hand-to-mouth gestures, container movement, and head motion during chewing [6]. |

| In-Ear Microphone | Condenser Microphone | Acquires acoustic signals of swallowing and other ingestion-related sounds from the ear canal [6]. |

| Wearable Camera | AIM-2 Camera Module | Automatically captures first-person (egocentric) images at set intervals for passive food item recognition and environmental context [20]. |

| Sensor-Equipped Container | 3D-Printed Cup with IMU | Measures motion dynamics specific to the drinking vessel, providing a direct signal correlated with consumption acts [6]. |

| Data Annotation Software | MATLAB Image Labeler | Enables manual labeling of ground truth data, such as bounding boxes around food items in images or timestamps of eating episodes [20]. |

| Machine Learning Library | Scikit-learn, XGBoost | Provides algorithms (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost) for building and evaluating classification models based on single- or multi-sensor features [6]. |

The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that multi-sensor fusion significantly enhances observational capabilities for detecting eating and drinking behaviors. The key rationale is the complementary nature of different sensing modalities: motion sensors capture physical actions, acoustic sensors capture ingestion sounds, and cameras provide visual confirmation. When one modality is weak or confused by confounding activities, the other modalities provide reinforcing or disambiguating evidence [6] [20].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings have important implications. The increased sensitivity and reliability of fused systems reduce the likelihood of missing critical behavioral events in clinical trials or observational studies. Furthermore, the reduction in false positives decreases data noise and improves the signal-to-noise ratio for measuring intervention effects. When designing studies, researchers should prioritize multi-modal sensing platforms that enable data fusion, as this approach provides a more valid, comprehensive, and objective measure of complex behaviors like dietary intake.

Key Applications in Clinical Research and Chronic Disease Management

The accurate assessment of dietary intake and eating behaviors is a fundamental challenge in clinical research and chronic disease management. Traditional methods, including 24-hour recalls, food diaries, and food frequency questionnaires, rely on self-reporting and are prone to significant inaccuracies from recall bias and participant burden, with energy intake underestimation ranging from 11% to 41% [22] [23]. These limitations hinder research into conditions like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease, where understanding micro-level eating patterns is crucial [1] [24].

Wearable sensor technology presents a transformative solution by enabling passive, objective monitoring of eating behavior in real-life settings [25] [24]. A central question in this field is whether multi-sensor systems, which combine diverse data streams, offer superior accuracy compared to single-sensor approaches. This guide objectively compares the performance of these technological strategies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the data needed to select appropriate tools for clinical studies and interventions.

Technology Comparison: Multi-Sensor vs. Single-Sensor Approaches

Wearable eating detection systems can be broadly categorized by the number of sensing modalities they employ. The tables below compare the core architectures, performance, and applicability of these approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Sensor System Architectures and Primary Functions

| System Type | Common Sensor Combinations | Measured Eating Metrics | Typical Form Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Sensor | Wrist-based Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) [7] | Eating episodes, hand-to-mouth gestures, bite count [7] | Smartwatch [7] |

| Acoustic sensor (neck-placed) [1] | Chewing, swallowing [1] | Neck pendant [1] | |

| Optical sensors (smart glasses) [16] | Chewing segments, chewing rate [16] | Smart glasses [16] | |

| Multi-Sensor | IMU + PPG + Temperature Sensor + Oximeter [22] [23] | Hand movements, heart rate, skin temperature, oxygen saturation [22] [23] | Custom multi-sensor wristband [22] [23] |

| IMU + Acoustic Sensors [1] | Hand gestures, chewing sounds, swallowing [1] | Smartwatch + separate wearable(s) |

Table 2: Performance Data and Applicability in Research Settings

| System Type & Reference | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Sensor (Smartwatch IMU) [7] | Precision: 80%, Recall: 96%, F1-score: 87.3% (for meal detection) [7] | High user acceptability; leverages commercial devices; good for detecting eating episodes [7] [25] | Cannot estimate energy intake; limited to gestural detection [22] |

| Single-Sensor (Smart Glasses) [16] | F1-score: 0.91 (for chewing detection in lab) [16] | Directly monitors mandibular movement; granular chewing data [16] | Social acceptability of always-on smart glasses |

| Multi-Sensor (Wristband) [22] [23] | High accuracy in distinguishing eating from other activities; Correlation of HR with meal size (r=0.990, P=0.008) [23] | Potential for energy intake estimation; richer dataset for differentiating confounding activities [22] [23] | Higher form-factor complexity; early validation stage [22] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To evaluate the claims in the comparison tables, it is essential to understand the methodologies used to generate the supporting data.

Protocol for Multi-Sensor Physiological Response Validation

A 2025 study protocol outlines a controlled experiment designed to validate a multi-sensor wristband for dietary monitoring [22] [23].

- Objective: To investigate the relationship between food intake and multimodal physiological/behavioral responses captured by a wearable sensor band [22] [23].

- Participants: 10 healthy volunteers (BMI 18-30 kg/m²) [22] [23].

- Study Design: Randomized controlled crossover trial in a clinical research facility.

- Intervention: Participants consume pre-defined high-calorie (1052 kcal) and low-calorie (301 kcal) meals in random order. Eating is performed with and without cutlery to mimic real-world behaviors [22] [23].

- Data Collection:

- Wearable Sensors: A custom wristband continuously records heart rate (HR), skin temperature (Tsk), oxygen saturation (SpO2), and hand movements (via IMU) from 5 minutes before until 1 hour after the meal [23].

- Validation Instruments: A bedside vital sign monitor tracks blood pressure, HR, and SpO2 for validation. Blood is sampled via intravenous cannula to measure glucose, insulin, and hormone levels [22] [23].

- Analysis: The relationship between meal parameters (e.g., calorie content) and physiological changes (e.g., HR increase) is analyzed, alongside motion patterns from the IMU [22] [23].

Protocol for Single-Sensor, Real-World Eating Detection

A 2020 study deployed a single-sensor, smartwatch-based system to detect eating in free-living conditions, highlighting a different methodological approach [7].

- Objective: To design and validate a real-time eating detection system for capturing meal episodes and contextual data [7].

- Participants: 28 college students in a real-world setting over 3 weeks [7].

- Sensor Modality: A single commercial smartwatch (Pebble watch) with a 3-axis accelerometer was worn on the dominant hand [7].

- Data Collection & Ground Truth:

- Passive Sensing: Accelerometer data was continuously collected.

- Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA): When the system detected 20 eating gestures within 15 minutes, it prompted the user to complete a short questionnaire about their meal context (e.g., company, location, food type) [7].

- Analysis: A machine learning pipeline (Random Forest classifier) was trained on features extracted from the accelerometer data to detect eating gestures. System-detected meals were validated against participant-confirmed EMA responses [7].

The workflow and logical relationship of these experimental approaches are summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

For researchers designing similar studies, the following tools and materials are essential components of the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Research Tool / Material | Primary Function in Eating Behavior Research |

|---|---|

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) [7] [22] | Tracks wrist and arm kinematics to detect hand-to-mouth gestures as a proxy for bites and eating episodes. |

| Photoplethysmography (PPG) Sensor [23] | Monitors heart rate (HR) and blood volume changes; used to detect meal-induced physiological responses. |

| Pulse Oximeter [22] [23] | Measures blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), a parameter that may decrease following meal consumption due to intestinal oxygen use. |

| Optical Tracking Sensors (e.g., OCO) [16] | Embedded in smart glasses to monitor facial muscle movements associated with chewing, distinguishing it from speaking or clenching. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) [7] | A self-report method using short, in-the-moment questionnaires on mobile devices to provide contextual ground truth (e.g., meal type, company) for validating passive sensor data. |

| Custom Multi-Sensor Wristband [22] [23] | An integrated wearable platform that synchronizes data from multiple sensors (IMU, PPG, oximeter, temperature) to capture a holistic view of behavioral and physiological responses. |

| Standardized Test Meals [22] [23] | Pre-defined meals with specific calorie and macronutrient content (e.g., high- vs. low-calorie) used in controlled studies to elicit standardized physiological responses. |

The evidence indicates a functional trade-off between single-sensor and multi-sensor approaches. Single-sensor systems, particularly those based on IMUs, demonstrate high accuracy for detecting eating episodes and gestural patterns with high user acceptability, making them suitable for large-scale, long-term behavioral studies [7] [25]. In contrast, multi-sensor systems represent the cutting edge for obtaining a deeper, physiological understanding of food intake. By correlating motion with physiological markers like heart rate and oxygen saturation, they hold the potential to move beyond mere event detection toward estimating energy intake and understanding individual metabolic responses [22] [23].

Future research should focus on validating these technologies, especially multi-sensor systems, in larger and more diverse populations, including those with chronic conditions like obesity and diabetes [22]. Furthermore, developing robust, publicly available algorithms for data processing and exploring privacy-preserving methods remain critical challenges [1] [25]. As these technologies mature, they will become indispensable tools for unlocking novel insights into diet-disease relationships and personalizing chronic disease management.

Implementing Multi-Sensor Systems: Fusion Architectures and Technical Frameworks

Multi-sensor fusion has emerged as a cornerstone technology for enhancing perception capabilities across diverse fields, from autonomous driving to industrial monitoring and food quality assessment. The fundamental principle underpinning sensor fusion is that data from multiple sensors, when combined effectively, can produce a more accurate, robust, and comprehensive environmental understanding than any single sensor could achieve independently [26]. As intelligent systems increasingly operate in dynamic, real-world environments, the strategic integration of complementary sensor data has become critical for reliable decision-making [21].

Sensor fusion architectures are broadly categorized into three main paradigms based on the stage at which integration occurs: early fusion (also known as data-level fusion), feature-level fusion (sometimes called mid-fusion), and late fusion (decision-level fusion) [27] [18]. Each approach presents distinct advantages and trade-offs in terms of information retention, computational complexity, fault tolerance, and implementation practicality. The selection of an appropriate fusion paradigm depends heavily on application-specific requirements including environmental constraints, available computational resources, sensor characteristics, and accuracy demands [28].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of these three fundamental fusion architectures, supported by experimental data and implementation methodologies from contemporary research. By objectively analyzing the performance characteristics of each paradigm across diverse applications, we aim to provide researchers and engineers with evidence-based guidance for selecting and optimizing fusion strategies tailored to specific sensing challenges, particularly within the context of detection accuracy research comparing multi-sensor versus single-sensor approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Fusion Architectures

The following section provides a detailed technical comparison of the three primary sensor fusion paradigms, examining their conceptual frameworks, representative applications, and relative performance characteristics.

Early Fusion (Data-Level Fusion) integrates raw data from multiple sensors before any significant processing occurs. This approach combines unprocessed or minimally processed sensor readings, preserving the maximum amount of original information [27] [18]. In autonomous driving applications, for instance, this might involve projecting LiDAR point clouds directly onto camera images using geometric transformations, creating a dense, multi-modal data representation before any feature extraction or detection algorithms are applied [28].

Feature-Level Fusion (Mid-Fusion) operates at an intermediate processing stage, where each sensor stream is first processed to extract salient features, which are then combined into a unified feature representation [26] [18]. This approach balances raw data preservation with computational efficiency by leveraging domain-specific feature extractors for each modality before fusion. For example, in food spoilage detection, feature-level fusion might combine spectral features from infrared spectroscopy with texture features from multispectral imaging before final quality classification [18].

Late Fusion (Decision-Level Fusion) processes each sensor stream independently through complete processing pipelines, combining the final outputs or decisions through voting, weighting, or other meta-learning strategies [27] [18]. This modular approach maintains sensor independence until the final decision stage. In autonomous systems, late fusion might combine independently generated detection results from camera and LiDAR subsystems, using confidence scores or spatial overlap criteria to reach a consensus decision [27].

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison of Sensor Fusion Paradigms

| Characteristic | Early Fusion | Feature-Level Fusion | Late Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion Stage | Raw data level | Feature representation level | Decision/output level |

| Information Retention | High - preserves all raw data | Moderate - preserves extracted features | Low - preserves only decisions |

| Data Synchronization | Requires precise temporal alignment | Moderate synchronization needs | Minimal synchronization requirements |

| System Modularity | Low - tightly coupled sensors | Moderate - feature extractors are modular | High - complete processing independence |

| Fault Tolerance | Low - single sensor failure affects entire system | Moderate - failures affect feature streams | High - systems can operate with sensor loss |

| Computational Load | High - processes raw multi-modal data | Moderate - leverages extracted features | Variable - depends on individual processors |

Performance Comparison Across Applications

Experimental studies across diverse domains consistently demonstrate that multi-sensor fusion approaches generally outperform single-sensor detection systems, with the magnitude of improvement varying by application domain and fusion methodology.

In food quality monitoring, a domain requiring high detection accuracy, multi-sensor fusion has shown dramatic improvements over single-sensor approaches. Research on Korla fragrant pear freshness assessment demonstrated that a feature-level fusion approach combining gas composition, environmental parameters, and dielectric properties achieved 97.50% accuracy using an optimized machine learning model. This performance substantially exceeded single-sensor models, with gas-only data achieving merely 47.12% accuracy - highlighting the critical importance of complementary multi-modal data fusion [29]. Similarly, in apple spoilage detection, multi-sensor fusion combining gas sensors with environmental monitors (temperature, humidity, vibration) enabled deep learning models (Si-GRU) to achieve correlation coefficients above 0.98 in spoilage prediction, significantly outperforming single-modality approaches [30].

Manufacturing quality control presents another domain where multi-sensor fusion delivers measurable benefits. In selective laser melting monitoring, a feature-level fusion approach combining acoustic emission and photodiode signals achieved superior classification performance for identifying product quality issues compared to either sensor used independently [31]. The fused system successfully detected porosity and density variations that single-sensor systems missed, demonstrating the complementary nature of optical and acoustic sensing modalities for capturing different aspects of manufacturing process dynamics.

Autonomous driving systems, perhaps the most extensively studied application of sensor fusion, show similar patterns. While quantitative performance metrics vary based on specific implementations, the fusion of camera, LiDAR, and radar sensors consistently outperforms single-modality perception systems across critical tasks including object detection, distance estimation, and trajectory prediction [26] [21]. The complementary strengths of visual semantic information (cameras), precise geometric data (LiDAR), and robust velocity measurements (radar) create a perception system that remains functional under diverse environmental conditions where individual sensors would fail [26].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Application Domain | Single-Sensor Performance | Multi-Sensor Fusion Performance | Fusion Paradigm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Freshness (Korla Pear) | 47.12% accuracy (gas sensor only) | 97.50% accuracy | Feature-level fusion |

| Apple Spoilage Detection | R < 0.88 (single sensors) | R > 0.98 (calibration & prediction) | Feature-level fusion |

| Additive Manufacturing | Moderate classification accuracy | "Best classification performance" | Feature-level fusion |

| Meat Spoilage Prediction | Variable accuracy based on sensor type | Up to 15% improvement in prediction accuracy | Early, feature, and late fusion |

Advantages and Limitations

Each fusion paradigm presents characteristic strengths and weaknesses that determine its suitability for specific applications:

Early Fusion maximizes information retention from all sensors, potentially enabling the discovery of subtle cross-modal correlations that might be lost in processed features or decisions [27]. This approach allows subsequent algorithms to leverage the complete raw dataset, which is particularly valuable when the relationship between different sensor modalities is complex or not fully understood. However, early fusion demands precise sensor calibration and synchronization, creates high computational loads, and exhibits poor fault tolerance - if one sensor fails, the entire fused data stream becomes compromised [28]. Additionally, early fusion must overcome the "curse of dimensionality" when combining high-dimensional raw data from multiple sources [27].

Feature-Level Fusion offers a practical balance between information completeness and computational efficiency. By processing each sensor modality with specialized feature extractors before fusion, this approach leverages domain knowledge to reduce dimensionality while preserving discriminative information [18]. This architecture supports some modularity, as feature extractors can be updated independently. The primary challenge lies in identifying optimal fusion strategies for combining potentially disparate feature representations, and ensuring temporal alignment across feature streams [26]. This approach may also discard potentially useful information during the feature extraction process.

Late Fusion provides maximum modularity and fault tolerance, as each sensor processing pipeline operates independently [27]. This architecture facilitates system integration and maintenance, allows for heterogeneous processing frameworks optimized for specific sensors, and enables graceful degradation - if one sensor fails, the system can continue operating with reduced capability using remaining sensors [27] [28]. The primary limitation is substantial information loss, as decisions are made without access to raw or feature-level cross-modal correlations [18]. This can reduce overall accuracy, particularly when sensors provide complementary but ambiguous information that requires cross-referencing at a finer granularity than final decisions allow [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducible results in sensor fusion research, standardized experimental protocols and rigorous methodology are essential. This section outlines common approaches for evaluating fusion architectures across domains.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

Multi-sensor experimentation requires careful experimental design to isolate fusion effects from confounding variables. In food quality studies, researchers typically employ controlled sample preparation with systematic variation of target parameters [30] [29]. For Korla fragrant pear monitoring, researchers collected 340 fruits with standardized specifications (weight: 125.7±5.3g, uniform coloration) and stored them under precisely controlled temperature conditions (0°C, 4°C, 25°C) while monitoring freshness indicators over 45 days [29]. Similarly, in meat spoilage analysis, chicken and beef samples were stored under aerobic, vacuum, and modified atmosphere conditions at multiple temperatures, with monitoring at 24-48 hour intervals until visual deterioration occurred [18].

Sensor selection strategically combines complementary modalities. In autonomous driving, this typically involves cameras (2D visual texture, color), LiDAR (3D geometry), radar (velocity, all-weather operation), and sometimes ultrasonic sensors (short-range detection) [26] [21]. For food monitoring, electronic noses (volatile organic compounds), spectral sensors (chemical composition), and environmental sensors (temperature, humidity) are commonly integrated [30] [18]. Data synchronization remains critical, particularly for early and feature-level fusion, often requiring hardware triggers or software timestamps with millisecond precision [28].

Feature Extraction and Fusion Techniques

Feature extraction methodologies vary significantly by sensor modality and application domain. In visual data processing, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) automatically extract hierarchical features from images [31]. For time-series sensor data (gas sensors, accelerometers), statistical features (mean, variance, peaks), frequency-domain features (FFT, wavelet coefficients), or deep learning sequences (LSTM, GRU) are commonly employed [30]. In manufacturing monitoring, researchers have developed specialized signal-to-image conversion techniques that transform 1D acoustic emissions and photodiode signals into 2D representations compatible with CNN-based feature extractors [31].

Fusion implementation ranges from simple concatenation to sophisticated learning-based integration. Early fusion often employs geometric transformation (projecting LiDAR points to camera images) or data concatenation [28]. Feature-level fusion commonly uses concatenation, weighted combination, or attention mechanisms to merge feature vectors [18]. Late fusion typically employs voting schemes, confidence-weighted averaging, or meta-classifiers (stacked generalization) to combine decisions from independent models [27] [18].

Model Training and Evaluation

Robust evaluation methodologies employ cross-validation, hold-out testing, and appropriate performance metrics. In food quality studies, models are typically trained on calibration datasets and evaluated on separate prediction sets, with performance reported using accuracy, correlation coefficients (R), F1-scores, and root mean square error (RMSE) [30] [29]. Autonomous driving research uses benchmark datasets (nuScenes, KITTI) and standardized metrics (mAP, NDS) for objective comparison [21].

Optimization techniques frequently enhance baseline fusion performance. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms (GA) have successfully optimized model parameters in food monitoring applications [29]. Deep learning approaches increasingly leverage gradient-based optimization, with some implementations using specialized architectures (Transformers, cross-modal attention) to learn optimal fusion strategies directly from data [26] [21].

Visualization of Fusion Architectures

The following diagrams illustrate the structural relationships and data flow within each fusion paradigm, created using Graphviz DOT language with high-contrast color schemes to ensure readability.

Early Fusion Architecture

Early Fusion Data Flow

Feature-Level Fusion Architecture

Feature-Level Fusion Data Flow

Late Fusion Architecture

Late Fusion Data Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Components for Multi-Sensor Fusion Experiments

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Modalities | RGB cameras, LiDAR sensors, Radar units, Gas sensors, Spectral sensors, Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Data acquisition from physical environment across multiple complementary dimensions |

| Data Acquisition Systems | Synchronized multi-channel data loggers, Signal conditioning hardware, Time-stamping modules | Simultaneous capture of multi-sensor data with precise temporal alignment |

| Feature Extraction Tools | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Wavelet transform algorithms, Statistical feature calculators, Autoencoders | Transform raw sensor data into discriminative representations for fusion |

| Fusion Algorithms | Concatenation methods, Attention mechanisms, Kalman filters, Weighted averaging, Stacked generalization | Integrate information from multiple sources into unified representations or decisions |

| Model Optimization Frameworks | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), Gradient-based optimization, Hyperparameter tuning libraries | Enhance fusion model performance through systematic parameter optimization |

| Validation Methodologies | Cross-validation protocols, Benchmark datasets (nuScenes, KITTI), Statistical significance tests, Ablation studies | Objectively evaluate fusion performance and contribution of individual components |

This comparison guide has systematically examined the three primary sensor fusion paradigms - early, feature-level, and late fusion - through objective performance analysis and experimental validation. The evidence consistently demonstrates that multi-sensor fusion substantially enhances detection accuracy compared to single-sensor approaches across diverse applications, with documented improvements ranging from 15% to over 100% in classification accuracy depending on the domain and implementation [30] [18] [29].

No single fusion paradigm universally outperforms others across all applications. Instead, the optimal architecture depends on specific system requirements: early fusion maximizes information retention but demands precise synchronization, feature-level fusion balances performance with practical implementation considerations, while late fusion prioritizes modularity and fault tolerance [27] [18] [28]. Researchers and engineers should select fusion strategies based on their specific priorities regarding accuracy, robustness, computational resources, and system maintainability.

Future research directions will likely focus on adaptive fusion strategies that dynamically adjust fusion methodology based on environmental conditions and sensor reliability, as well as end-to-end learning approaches that optimize the entire fusion pipeline jointly rather than as separate components [27] [21]. As sensor technologies continue to advance and computational resources grow, multi-sensor fusion will remain an essential methodology for developing intelligent systems capable of reliable operation in complex, real-world environments.

Accurate and objective monitoring of eating behavior is a critical challenge in nutritional science, behavioral medicine, and chronic disease management. Traditional methods like food diaries and 24-hour recalls are plagued by recall bias and inaccuracies, limiting their utility for precise interventions [1]. Wearable sensor technologies have emerged as a promising solution, offering the potential to passively and objectively detect eating episodes, quantify intake metrics, and capture contextual eating patterns. Among the various platforms developed, three distinct approaches have demonstrated significant promise: the AIM-2 (a glasses-based system), NeckSense (a necklace-form factor), and various wrist-worn IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) systems. These platforms represent different philosophical and technical approaches to eating detection, particularly in their implementation of single versus multi-sensor data fusion strategies. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these three wearable sensor platforms, focusing on their technical architectures, performance metrics, and applicability for research and clinical applications, framed within the broader thesis investigating how sensor fusion enhances eating detection accuracy.

The following table provides a detailed comparison of the three wearable sensor platforms across technical specifications, performance metrics, and key operational characteristics.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Wearable Eating Detection Sensor Platforms

| Feature | AIM-2 (Automatic Ingestion Monitor v2) | NeckSense | Wrist-Worn IMU Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Form Factor | Eyeglasses-mounted [32] | Necklace [9] | Wristwatch/Smartwatch [7] [33] |

| Core Sensing Modalities | Accelerometer (3-axis) + Flex Sensor (temporalis muscle) + Gaze-aligned Camera [32] | Proximity Sensor + IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) + Ambient Light Sensor [9] | Inertial Measurement Unit (Accelerometer, often with Gyroscope) [7] [33] |

| Primary Detection Method | Chewing muscle movement + head motion [32] | Jaw movement, lean-forward angle, feeding gestures [9] | Hand-to-mouth gesture recognition [7] [33] |

| Key Performance Metrics (Reported) | Eating intake detection F1-score: 81.8 ± 10.1% (over 10-sec epochs); Episode detection accuracy: 82.7% [32] | Eating episode F1-score: 81.6% (Exploratory study); 77.1% (Free-living) [9] | Meal detection F1-score: 87.3% [7]; Eating speed MAPE: 0.110 - 0.146 [33] |

| Key Advantages | - Direct capture of food imagery- High specificity from muscle sensing- Alleviates privacy concerns via triggered capture [32] | - Suitable for diverse BMI populations- Longer battery life (up to 15.8 hours)- Less socially awkward than glasses [9] | - High user acceptability (common form factor)- Suitable for long-term deployment- Can leverage commercial smartwatches [7] [1] |

| Primary Limitations | - Requires wearing eyeglasses- Potential discomfort from flex sensor- Limited to chewed foods [32] | - May not detect non-chewable foods- Potential visibility/comfort issues- Performance varies with body habitus [9] | - Cannot distinguish eating from other similar gestures- Cannot detect food type or energy intake- Highly dependent on consistent hand-to-mouth gesture [33] [1] |

| Validation Environment | 24h pseudo-free-living + 24h free-living (30 participants) [32] | Semi-free-living + completely free-living (20 participants, 117 meals) [9] | College campus free-living (28 participants, 3 weeks) [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

AIM-2 Validation Study Design

The AIM-2 system was validated through a cross-sectional observational study involving 30 volunteers. The protocol consisted of two consecutive days: one day in a pseudo-free-living environment (food consumption in the lab with otherwise unrestricted activities) and one day in a completely free-living environment. The sensor module, housed on eyeglasses, included a 5-megapixel camera capturing images every 15 seconds for validation, a 3-axis accelerometer, and a flex sensor placed over the temporalis muscle to capture chewing contractions. Data from the accelerometer and flex sensor were sampled at 128 Hz. The study used video recordings from laboratory cameras as ground truth for algorithm development and validation. The off-line processing in MATLAB focused on detecting food intake over 10-second epochs and entire eating episodes [32].

NeckSense Evaluation Framework

NeckSense was evaluated across two separate studies. An initial Exploratory Study (semi-free-living) was conducted to identify useful sensors and address usability concerns. This was followed by a Free-Living Study involving a demographically diverse population, including participants with and without obesity, to test the system in completely naturalistic settings. The device fused data from its proximity sensor (to capture jaw movement), ambient light sensor, and IMU (to capture lean-forward angle). The analytical approach first identified chewing sequences by applying a longest periodic subsequence algorithm to the proximity sensor signal, then augmented this with other sensor data and the hour of the day to improve detection. Finally, the identified chewing sequences were clustered into distinct eating episodes [9].

Wrist-Worn IMU System Development

The development of wrist-worn systems typically builds upon existing datasets of hand movements. One prominent study deployed a system among 28 college students for three weeks. The detection pipeline used a 50% overlapping 6-second sliding window to extract statistical features (mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis, and root mean square) from the 3-axis accelerometer data of a commercial smartwatch. A machine learning classifier (Random Forest) was trained to detect eating gestures. For real-time meal detection, the system was programmed to trigger an Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) prompt upon detecting 20 eating gestures within a 15-minute window, which also served as a validation mechanism. This approach focused on aggregating individual hand-to-mouth gestures into meal-scale eating episodes [7]. Another approach for measuring eating speed used a temporal convolutional network with a multi-head attention module (TCN-MHA) to detect bites from full-day IMU data, then clustered these predicted bites into episodes to calculate eating speed [33].

Multi-Sensor vs. Single-Sensor Architectures

The fundamental thesis in comparing these platforms centers on the trade-offs between multi-sensor data fusion and single-sensor approaches. The following diagram illustrates the core architectural differences and data flow in multi-sensor versus single-sensor approaches for eating detection.