Neck-Worn Eating Detection Systems: Development, Challenges, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the development lifecycle for neck-worn eating detection systems, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Neck-Worn Eating Detection Systems: Development, Challenges, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the development lifecycle for neck-worn eating detection systems, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of using sensor systems to passively and objectively detect eating behaviors, moving beyond traditional self-report methods. The content covers the methodological approaches for system design, including multi-sensor integration and algorithmic development, and delves into critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world deployment. Finally, it offers a rigorous framework for the validation and comparative analysis of these systems against other sensing modalities, discussing their significant potential to enhance dietary assessment in clinical research and nutrition care.

The Foundation of Automated Dietary Monitoring: Principles and Potential

The Critical Need for Objective Eating Behavior Data in Clinical Research

Traditional methods for assessing dietary intake and eating behavior in clinical research have relied predominantly on self-reported tools such as 24-hour dietary recalls, food diaries, and food frequency questionnaires [1] [2]. While these methods have been widely used, they are susceptible to significant limitations including recall error, social desirability bias, and intentional misreporting [1]. The subjective nature of these tools challenges the reliability of data collected in both clinical trials and nutritional surveillance studies.

The emergence of sensor-based technologies offers a transformative opportunity to capture objective, behaviorally-defined eating metrics. This shift is particularly critical in obesity research, drug development, and nutritional science, where precise measurement of eating behaviors is essential for evaluating intervention efficacy [2]. This document outlines structured protocols and application notes for implementing objective eating behavior assessment, with specific focus on integration with neck-worn detection systems within a comprehensive research framework.

The Case for Objectivity: Quantifying the Limitations of Self-Report

Evidence of Self-Report Inaccuracy

Multiple studies demonstrate the critical inaccuracies inherent in subjective eating behavior assessment:

- Visual Estimation Challenges: In clinical environments, nursing staff failed to record 44% (220/503) of meals correctly when using traditional food intake charts [3].

- Manual Input Limitations: Nutrition management applications requiring manual input demonstrate significant underestimation of energy intake and vary considerably in accuracy between platforms [3].

- Craving Measurement Limitations: Studies using the Food Craving Inventory (FCI) demonstrate that self-reported hunger metrics (e.g., visual analog scales) may not adequately control for objective physiological hunger states, potentially confounding results [4].

Comparative Accuracy of Objective Methods

Recent validation studies demonstrate the superior performance of objective assessment technologies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Eating Behavior Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Accuracy/Performance Metrics | Limitations | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Based Food Image Analysis | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.85 (8.5% error); high correlation with actual energy (ρ=0.89-0.97) [3] | Lower accuracy than direct visual estimation by trained staff; requires standardized imaging | Hospital liquid food estimation |

| Smartwatch-Based Meal Detection | 96.48% meals detected (1259/1305); Precision: 80%, Recall: 96%, F1-score: 87.3% [5] | Requires dominant hand movement; may miss non-hand-to-mouth eating | Free-living meal detection in college students |

| Objective Hunger Measurement (Fasting) | Significant correlation with cravings for sweets (r=0.381, p=0.034) [4] | Requires controlled fasting protocols; limited to specific time windows | Obesity research with controlled fasting |

Technological Landscape: Sensor-Based Modalities for Objective Eating Behavior Assessment

Sensor Taxonomy for Eating Behavior Measurement

Research identifies multiple sensor modalities capable of capturing distinct eating metrics [2]:

- Acoustic Sensors: Detect chewing and swallowing sounds through neck-worn devices

- Motion/Inertial Sensors: Capture hand-to-mouth gestures (wrist-worn) and head movement (neck-worn)

- Strain Sensors: Measure swallowing frequency and muscle activity

- Camera-Based Systems: Provide visual documentation of food type and quantity

- Physiological Sensors: Monitor heart rate, glucose, and other metabolic parameters

Integration Framework for Neck-Worn Detection Systems

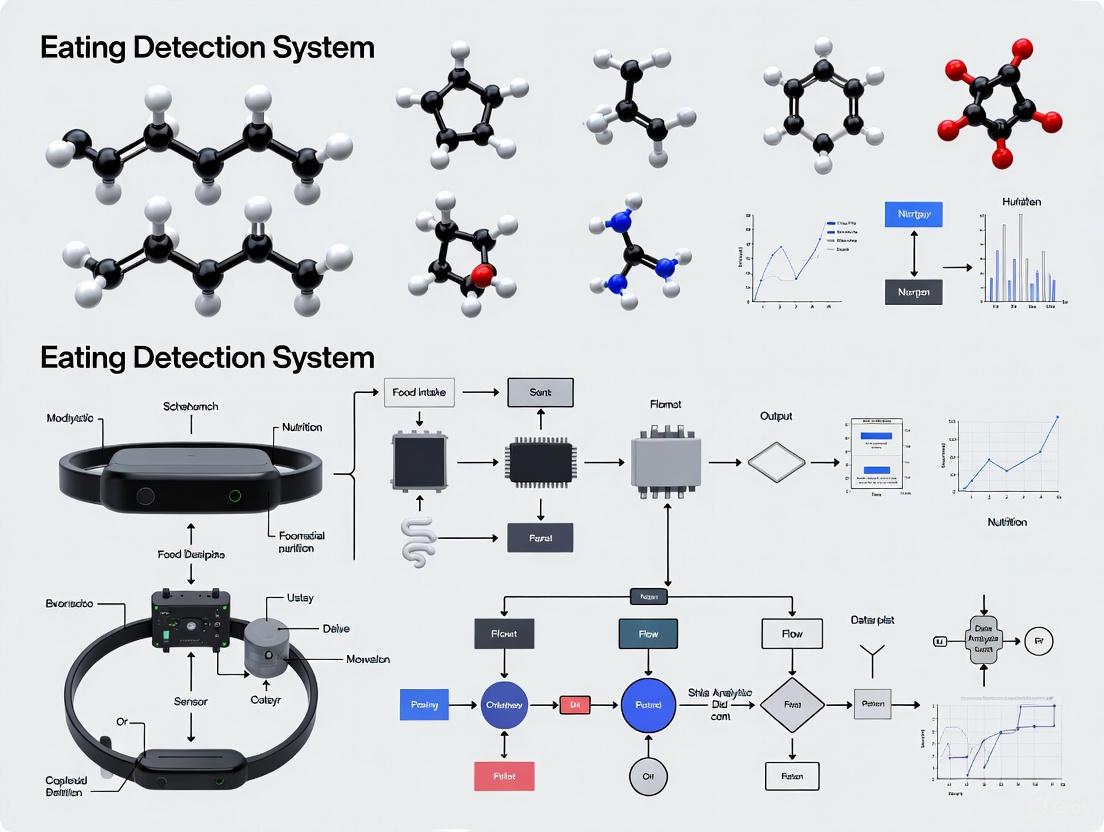

Neck-worn eating detection systems typically employ a multi-sensor approach, integrating data from acoustic, motion, and physiological sensors to detect eating episodes with high temporal resolution. The diagram below illustrates the core architecture and data flow for a comprehensive neck-worn eating detection system.

Application Notes: Implementation Protocols for Clinical Research

Protocol 1: Validation of Neck-Worn Sensors Against Objective Food Intake

Purpose: To establish criterion validity of neck-worn eating detection systems against weighed food intake in controlled clinical settings.

Experimental Workflow:

Methodological Details:

- Participants: Recruit 30-50 adults representing diverse BMI categories (normal weight, overweight, obesity)

- Control Measures: Implement standardized pre-meal fasting (≥4 hours), control for menstrual cycle phase (days 10-14 for premenopausal women) [4]

- Food Presentation: Serve standardized meals with predetermined portion sizes; weigh all food items pre- and post-consumption

- Sensor Configuration: Simultaneously deploy neck-worn acoustic sensors, inertial measurement units, and reference video recording

- Validation Metrics: Calculate sensitivity, specificity, F1-score for meal detection; intraclass correlation coefficients for meal duration; root mean square error for eating rate estimation

Protocol 2: Free-Living Eating Behavior Monitoring

Purpose: To characterize naturalistic eating patterns and contextual factors in free-living environments.

Methodological Details:

- Deployment Duration: 7-14 days to capture weekday/weekend variability

- Contextual Data Collection: Implement ecological momentary assessment (EMA) triggered by automated eating detection to capture:

- Social context (eating alone vs. with others)

- Location (home, work, restaurant)

- Mood and stress levels

- Food craving intensity [5]

- Compliance Optimization: Utilize smartwatch-based triggering (87.3% F1-score for meal detection) to prompt EMA responses during eating episodes [5]

- Data Integration: Temporally synchronize sensor data with EMA responses and auxiliary biometric data (e.g., continuous glucose monitoring, physical activity)

Protocol 3: Intervention Response Assessment

Purpose: To objectively quantify changes in eating behavior in response to pharmacological, behavioral, or surgical interventions.

Methodological Details:

- Study Design: Randomized controlled trials with pre-post intervention assessment

- Core Metrics:

- Eating microstructure: Bite rate, chewing rate, swallowing frequency

- Meal patterns: Meal frequency, timing, duration

- Eating rate: Grams per minute, kilocalories per minute

- Control Measures: Standardize food type and texture during laboratory meals; control for time of day

- Data Analysis: Compare pre-post changes in objective eating parameters between intervention and control groups; correlate with clinical outcomes (weight loss, metabolic parameters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Technologies for Objective Eating Behavior Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck-Worn Acoustic Sensors | - Piezoelectric microphones- Accelerometers | Capture chewing and swallowing sounds; vali-dated for eating episode detection [2] | Signal quality affected by ambient noise; requires positioning optimization |

| Inertial Measurement Units | - 3-axis accelerometers- Gyroscopes | Track head movement during food ingestion; complementary to acoustic sensors [2] | Can distinguish chewing from talking; sensitive to sensor placement |

| Algorithmic Platforms | - Random Forest classifiers- Convolutional Neural Networks- Support Vector Machines | Classify eating episodes from sensor data; achieve >90% detection accuracy in controlled settings [5] [6] | Performance varies by food texture; requires individual calibration |

| Validation Reference Systems | - Weighed food intake- Video recording- Double-labeled water | Establish criterion validity for newly developed detection systems [3] | Labor-intensive; may influence natural eating behavior |

| Contextual Assessment Tools | - Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)- Eating Behaviors Assessment for Obesity (EBA-O) | Capture subjective experience alongside objective metrics; assess pathological eating patterns [5] [7] | EMA timing critical; validated questionnaires disease-specific |

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Signal Processing and Feature Extraction

Raw sensor data requires sophisticated processing to extract meaningful eating behavior metrics:

- Acoustic Signals: Apply bandpass filtering (0.5-2 kHz) to capture chewing sounds; extract temporal features (burst duration, interval) and spectral features (median frequency, spectral entropy)

- Motion Signals: Process accelerometer data to identify characteristic head movement patterns associated with food ingestion; quantify movement frequency, amplitude, and regularity

- Sensor Fusion: Implement machine learning algorithms (e.g., convolutional neural networks, random forests) to integrate multi-modal sensor data for improved classification accuracy [5] [1]

Clinical Interpretation of Objective Eating Metrics

Translating sensor-derived metrics into clinically meaningful parameters requires validated frameworks:

- Eating Microstructure: Bite rate, chewing rate, and swallowing frequency correlate with energy intake rate and nutrient absorption

- Meal Temporal Patterns: Objective meal timing and frequency data provide insights into circadian eating patterns and their metabolic consequences

- Behavioral Phenotyping: Cluster analysis of multiple eating parameters can identify distinct behavioral phenotypes (e.g., rapid eaters, frequent snackers) with potential therapeutic implications [7]

The integration of objective, sensor-based eating behavior assessment into clinical research represents a paradigm shift with transformative potential. Neck-worn detection systems offer particular promise through their ability to capture rich, high-temporal resolution data on natural eating patterns in both controlled and free-living environments. The protocols and application notes outlined herein provide a framework for implementing these technologies with scientific rigor, enabling researchers to overcome the limitations of traditional self-report methods and advance our understanding of eating behavior as a critical component of health and disease.

The development of robust neck-worn eating detection systems represents a significant frontier in automated dietary monitoring (ADM) and precision health. These systems aim to objectively capture eating behaviors by detecting physiological and gestural signatures of food intake, thereby overcoming the limitations of self-reported methods [8] [2]. The core of such systems relies on a multi-modal sensing approach, where Piezoelectric Sensors, Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), and Acoustic Detection modules work in concert. Piezoelectric sensors capture mechanical vibrations from swallowing, IMUs track head and neck movements associated with feeding gestures, and acoustic sensors identify sounds related to chewing and swallowing. This application note details the operating principles, performance characteristics, and experimental protocols for integrating these three key sensing modalities, providing a foundational framework for researchers and engineers in the field [2] [9].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, target signals, and performance metrics of the three primary sensing modalities used in neck-worn eating detection systems.

Table 1: Core Sensing Modalities for Neck-Worn Eating Detection

| Sensing Modality | Primary Target Signals | Key Performance Metrics (from Literature) | Strengths | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric Sensor | Swallowing vibrations (anterior neck), laryngeal movement [9] | Swallow detection: F1-score of 0.864 (solid), 0.837 (liquid) [9] | High sensitivity to laryngeal movement, robust to ambient acoustic noise | Signal variation with sensor placement and skin contact; confounds from speech |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Head flexion/extension (forward/backward lean), hand-to-mouth gestures (via wrist IMU) [2] [9] | Critical for compositional eating detection logic (e.g., forward lean + bites) [9] | Provides crucial contextual data for differentiating eating from other activities | Prone to motion artifacts; requires precise orientation tracking |

| Acoustic Detection | Chewing sounds, swallowing sounds, food texture [2] | Food-type classification (7 types): 84.9% accuracy with a neck-worn microphone [2] | Direct capture of ingestive sounds, rich data for food type classification | Susceptible to ambient noise; significant privacy concerns [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Modality Evaluation

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for validating the performance of each sensing modality individually and in an integrated system. The following workflows and procedures outline standardized methods for data collection and analysis.

Protocol for Piezoelectric Swallow Detection

This protocol is designed to evaluate the efficacy of a piezoelectric sensor in detecting and classifying swallows in a controlled laboratory setting.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Piezoelectric Swallow Detection

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric Film Sensor | Converts mechanical strain from laryngeal movement into an electrical signal. | Embedded in a snug-fitting necklace form factor to ensure skin contact [9]. |

| Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | Conditions (amplifies, filters) and digitizes the analog signal from the piezoelectric sensor. | Requires high-resolution ADC; on-board filtering (e.g., 1-500 Hz bandpass) is recommended. |

| Mobile Ground Truth App | Allows annotator to manually mark the timing of each swallow event during the experiment. | Provides a synchronized ground truth label for supervised machine learning [9]. |

| Signal Processing & ML Software | For feature extraction (e.g., wavelet features) and training a swallow classifier (e.g., SVM). | Used to derive performance metrics like F1-score from the labeled dataset [9]. |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for piezoelectric swallow detection, showing the parallel paths of data collection and ground truth annotation leading to model evaluation.

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Recruit participants following institutional review board (IRB) protocols. Fit the neck-worn device with the embedded piezoelectric sensor snugly against the anterior neck.

- Data Collection: In a controlled lab environment, present participants with standardized boluses of solid and liquid foods. Simultaneously:

- Signal Acquisition: Record the raw voltage signal from the piezoelectric sensor.

- Ground Truth Annotation: A trained annotator uses a mobile application to mark the exact timing of every swallow event, creating a labeled dataset [9].

- Data Processing: Synchronize the sensor signal and ground truth labels. Preprocess the signal (bandpass filtering, normalization) and segment it into windows containing swallow and non-swallow events.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Extract features (e.g., time-domain, frequency-domain, wavelet) from the segmented data. Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine) using cross-validation and report performance metrics like F1-score, accuracy, and recall [9].

Protocol for Multi-Modal Eating Episode Detection

This protocol describes a compositional method for detecting full eating episodes by fusing data from all three modalities, suitable for both lab and free-living validation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Multi-Modal Eating Detection

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Sensor Neckband | Wearable platform housing piezoelectric sensor, IMU, and microphone. | Enables synchronized data capture from all core modalities [9]. |

| Wearable Camera (e.g., egocentric camera) | Provides objective, first-person video as ground truth for eating episodes. | Must be synchronized with sensor data; raises privacy considerations [9]. |

| Data Fusion & Analysis Framework | Software platform to synchronize, process, and apply logic/rules to multi-modal data streams. | Implements the compositional logic for fusing detections from individual sensors. |

Figure 2: Logical decision diagram for multi-modal eating detection, illustrating how signals from different sensors are fused to robustly identify an eating episode.

Procedure:

- System Deployment: Deploy the multi-sensor neckband (piezoelectric, IMU, acoustic) to participants in lab or free-living settings. Synchronize the sensor data streams with a ground truth method, such as a wearable camera or a dedicated annotation app [9].

- Component Detection: Run individual detectors on each sensor stream:

- Piezoelectric Sensor: Identify swallow events.

- IMU: Detect feeding gestures (hand-to-mouth via wrist IMU) and head pose (forward lean).

- Acoustic Sensor: Detect chewing and biting events.

- Compositional Logic Fusion: Implement a logic-based or probabilistic model to fuse the outputs of the individual detectors. For example, an eating episode is predicted only if bites, chews, swallows, feeding gestures, and a forward lean are detected in close temporal proximity [9]. This approach improves robustness; detecting only swallows and a backward lean might indicate drinking instead.

- Validation: Compare the system's detected eating episodes against the ground truth. Report episode-level precision, recall, and F1-score. Free-living studies are critical for testing the system's resilience to confounding activities (e.g., talking, smoking) [9].

Discussion and Integration Strategy

The true strength of a neck-worn eating detection system lies in the synergistic fusion of its constituent modalities. While each sensor has limitations—acoustic sensors are sensitive to noise, piezoelectric signals vary with placement, and IMUs are prone to motion artifacts—their combination creates a robust system through compositionality [9]. This multi-modal approach allows the system to cross-validate signals, significantly reducing false positives caused by confounding behaviors like speaking or non-food hand-to-mouth gestures.

Future development should focus on optimizing sensor fusion algorithms, enhancing energy efficiency for long-term deployment, and rigorously validating systems in diverse, free-living populations to ensure generalizability. Addressing privacy concerns, particularly for acoustic data, through advanced on-device processing and sound filtering will be essential for user adoption and ethical implementation [2].

Application Notes

Rationale and Technological Foundation

The development of neck-worn eating detection systems represents a paradigm shift in objective dietary monitoring, moving from isolated swallow capture to a comprehensive compositional analysis of eating behavior. This approach leverages the neck as a physiologically strategic site, using mechano-acoustic sensors to detect vibrations propagated from the vocal tract and upper digestive system during feeding activities. Unlike acoustic microphones, these sensors preserve user privacy through inherent signal filtering and demonstrate robust performance against background noise, making them ideal for ecologically valid monitoring [10].

The "compositional approach" conceptualizes a meal not as a single event but as a hierarchical structure of discrete behavioral components: swallows, chews, and bites. By detecting and temporally sequencing these fundamental elements, the system can reconstruct complete eating episodes and extract meaningful behavioral patterns. Research on throat physiology monitors has demonstrated high accuracy in classifying swallowing events, forming the foundational layer upon which this compositional model is built [11] [12].

Key Performance Metrics of Detection System Components

Table 1: Performance characteristics of different sensing modalities for detecting components of eating behavior.

| Detection Component | Sensing Modality | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swallow Detection | Neck Surface Accelerometer (NSA) | High accuracy in classifying swallowing events [11] | Privacy-preserving, robust to background noise [10] | Early development stage [11] |

| Chew Detection | Video-based Facial Landmarks | 60% accuracy for chew counting [13] | Non-invasive, scalable | Requires camera, privacy concerns |

| Bite Detection | Smartwatch Inertial Sensing (Hand-to-Mouth) | F1-score of 87.3% for meal detection [5] | Leverages commercial hardware, real-time capability | Requires watch wear on dominant hand |

| Bite Detection | Video-based Facial Landmarks | 90% accuracy for bite counting [13] | High accuracy for bites | Requires camera, privacy concerns |

| Meal Context | Smartwatch-Triggered Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) | 96.48% of meals successfully triggered EMAs [5] | Captures subjective contextual data in real-time | Relies on user self-report |

Data Integration and Output

Integrating data from these complementary detection layers enables the derivation of complex behavioral metrics that are clinically significant. These include:

- Eating Rate: Bites or grams consumed per minute.

- Chewing Efficiency: Chews per bite or per gram of food.

- Meal Duration: Total time from first to last bite.

- Swallowing Safety: Coordination of breathing and swallowing.

- Contextual Patterns: Meal timing, social context, and self-reported food type.

This multi-faceted data output provides a comprehensive digital phenotype of eating behavior, with applications ranging from clinical monitoring of dysphagia in head and neck cancer survivors to behavioral interventions for obesity [11] [5]. The integration of passive sensing with active self-report via EMAs creates a powerful mixed-methods framework for understanding the full context of eating [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Validation of a Neck-Worn Swallow Detection System

Objective: To validate the accuracy of a Neck Surface Accelerometer (NSA) for detecting and classifying swallowing events against a videofluoroscopic standard in a controlled lab setting.

Materials:

- In-house NSA device (e.g., Knowles BU-27135 accelerometer in silicon pad) [10]

- Data logger (e.g., Sony voice recorder, ICD-UX565F) [10]

- Videofluoroscopy system

- Standardized food and liquid consistencies (e.g., thin liquid, pudding, cookie)

- Disinfectant for equipment cleaning

Procedure:

- Sensor Placement: Attach the NSA sensor securely to the participant's neck at the sternal notch using double-sided adhesive and ensure a strong signal via a monitoring interface [10].

- System Synchronization: Synchronize the clock of the NSA data logger with the videofluoroscopy system to enable millisecond-level alignment of data streams.

- Calibration: Record a 30-second baseline of resting swallows (saliva swallows) with the participant in a seated position.

- Data Collection:

- Present the participant with 5 mL of each standardized consistency via a spoon or cup.

- Instruct the participant to hold the bolus in their mouth until cued to swallow.

- Simultaneously record swallowing vibrations via the NSA and the physiological swallow sequence via videofluoroscopy.

- Repeat each consistency three times in randomized order.

- Data Export: Transfer NSA data as WAV files and videofluoroscopy videos to a secure server for analysis [10].

Analysis:

- Annotation: A trained clinician will annotate the onset and type of each swallow on the videofluoroscopy recording, creating the ground truth.

- Feature Extraction: From the NSA signal, extract time-frequency features (e.g., signal energy, spectral centroid, duration) for each annotated swallow event.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Random Forest) using the videofluoroscopy annotations as labels and the NSA features as inputs.

- Performance Calculation: Calculate the precision, recall, and F1-score of the classifier for detecting and differentiating between swallow types.

Protocol B: Free-Living Meal Detection via Multi-Modal Sensing

Objective: To deploy a multi-modal sensor system (neck-worn sensor and smartwatch) for compositional eating behavior detection and contextual data capture in a free-living environment.

Materials:

- Neck-worn NSA device (as in Protocol A)

- Commercial smartwatch (e.g., Pebble, Apple Watch) running a custom eating detection app [5]

- Smartphone to act as a data hub and for administering EMAs [5]

Procedure:

- Device Setup:

- Fit the participant with the NSA device.

- Install the eating detection application on the smartwatch and smartphone.

- Fit the participant with the smartwatch on their dominant wrist.

- Briefing: Instruct the participant to wear both devices for 8-12 hours per day for 3 consecutive days and to go about their normal daily routine, including all meals and snacks.

- Passive Data Collection:

- The NSA continuously records vibrations from the neck.

- The smartwatch accelerometer continuously monitors for hand-to-mouth gestures characteristic of eating [5].

- Active Data Collection (EMA):

- Data Logging: Participants are provided with a simple diary to note the start and end times of their main meals for ground-truth validation.

Analysis:

- Meal Episode Segmentation: Use the smartwatch's meal detection output (e.g., a cluster of eating gestures) to define the start and end of putative meal episodes.

- Component Analysis: Within each meal episode, analyze the NSA signal to identify and count swallow and chew events.

- Data Fusion: Temporally align the swallow/chew data from the NSA with the bite data (from hand gestures) from the smartwatch to build a compositional timeline of the meal.

- Context Integration: Merge the derived behavioral metrics with the self-reported contextual data from the EMAs for a holistic analysis.

System Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Logical Workflow for Compositional Eating Detection

Multi-Modal Sensor Data Integration Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and tools for developing and testing neck-worn eating detection systems.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example/Specifications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck Surface Accelerometer (NSA) | Core sensor for detecting swallows and chews via neck skin vibrations. | Knowles BU-27135; <$100 per unit; 44.1 kHz sampling rate [10]. | Inherently privacy-preserving; robust against background noise [10]. |

| Data Logger | Records high-fidelity sensor data for later analysis. | Sony voice recorder (ICD-UX565F); saves data in WAV format [10]. | Sufficient battery life for intended recording duration; reliable storage. |

| Smartwatch with Inertial Sensors | Detects bites via hand-to-mouth movement patterns. | Commercial devices (e.g., Pebble, Apple Watch) with 3-axis accelerometer [5]. | Must support development of custom data collection applications. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) Software | Captures self-reported contextual data in real-time. | Custom smartphone app triggered by passive eating detection [5]. | Questions must be brief and designed for minimal user burden. |

| Videofluoroscopy System | Gold-standard ground truth for validating swallow detection. | Clinical-grade system for visualizing bolus flow during swallowing. | Restricted to lab settings due to radiation exposure and equipment requirements. |

| Signal Processing & Machine Learning Platform | For feature extraction, model training, and classification of eating events. | Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch; MATLAB. | Requires expertise in time-series analysis and machine learning. |

| Annotation Software | For manual labeling of sensor data to create ground-truth datasets. | Noldus Observer XT, ELAN, or custom solutions [13]. | Time-consuming process requiring trained, reliable annotators. |

Application Note: Navigating Research Barriers in Wearable Eating Detection

The development of neck-worn wearable systems for eating detection represents a paradigm shift in objective dietary monitoring for clinical research and obesity treatment. However, the translation of this technology from laboratory prototypes to reliable free-living clinical instruments faces three interconnected barriers: sample selection, transdisciplinarity, and real-world realism [9]. This application note synthesizes findings from multiple studies to provide a structured framework for addressing these challenges, complete with quantitative performance data and detailed methodological protocols.

Sample selection challenges arise when specific inclusion criteria limit participant recruitment, potentially compromising claims of translational potential. For instance, research indicates that eating research on non-obese samples often fails to generalize to obese populations, highlighting the critical need for representative sampling [9].

Transdisciplinarity presents integration challenges, as successful mHealth systems require unification of medical investigators, software, electrical, and mechanical engineers, computer scientists, research staff, and information technologists under a common goal [9]. This diversity of expertise, while necessary, creates significant coordination challenges.

Real-world realism remains elusive because controlled lab studies, while optimal for collecting data and ground truth, often fail to generalize to natural environments. Conversely, free-living studies substantially complicate data and ground truth collection procedures while introducing potential behavioral alterations due to device presence [9] [14].

Table 1: Evolution of Neck-Worn Eating Detection Systems Across Study Environments

| Study | Study Type | Participants (Obese) | Sensing Modalities | Primary Target | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (Alshurafa et al.) [9] | In-lab | 20 | Piezo | Swallow | 87.0% Detection |

| Study 2 (Kalantarian et al.) [9] | In-lab | 30 | Piezo, Accelerometer | Swallow | 86.4% Detection |

| Study 3 (Zhang et al.) [9] | In-wild | 20 (10) | Proximity, Ambient, IMU | Eating | 77.1% Detection |

| Study 4 (SenseWhy) [9] [15] | In-wild | 60 (60) | Proximity, Ambient, IMU | Eating | Analysis Ongoing |

Experimental Protocols for Eating Behavior Research

The SenseWhy Free-Living Study Protocol

The SenseWhy study exemplifies a comprehensive approach to addressing real-world realism challenges through multi-modal sensor deployment and rigorous ground truth collection [9] [15].

Primary Objective: To monitor eating behavior in free-living settings and identify overeating patterns through passive sensing and ecological momentary assessment (EMA).

Participant Profile:

- Sample: 65 adults with obesity (final analysis n=48 after attrition and data quality filters)

- Mean Age: 41 years (range: 21-66)

- Gender Distribution: 77.1% female

- Inclusion Criteria: BMI ≥30, smartphone ownership, willingness to wear sensors

Sensor Configuration:

- NeckSense Necklace: Multi-sensor neck-worn device detecting bites, chews, and feeding gestures

- HabitSense Body Camera: Activity-oriented camera with thermal sensing triggered by food presence

- Wrist-worn Activity Tracker: Commercial-grade device (FitBit/Apple Watch equivalent) for movement capture

Study Duration & Data Collection:

- Monitoring Period: 2 weeks per participant

- Total Data: 2,302 meal-level observations (average 48 meals per participant)

- Video Footage: 6,343 hours spanning 657 days with manual micromovement labeling

- EMA Collection: Psychological and contextual information gathered before and after meals

Ground Truth Establishment:

- Dietitian-Administered 24-hour Recalls: Standardized nutritional assessment

- Manual Video Annotation: Frame-by-frame labeling of bites, chews, and swallows

- Meal Classification: 369 (16.4%) of 2,246 meals identified as overeating episodes

Analytical Framework:

- Machine Learning: XGBoost classifier for overeating detection

- Feature Sets: EMA-only, passive sensing-only, and feature-complete models

- Clustering: Semi-supervised learning to identify overeating phenotypes

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Overeating Detection in SenseWhy Study

| Model Configuration | AUROC (Mean) | AUPRC (Mean) | Brier Score Loss | Top Predictive Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA-Only Features | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.13 | Light refreshment (negative), pre-meal hunger (positive), perceived overeating (positive) |

| Passive Sensing-Only | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.18 | Number of chews (positive), chew interval (negative), chew-bite ratio (negative) |

| Feature-Complete (Combined) | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.11 | Perceived overeating (positive), number of chews (positive), light refreshment (negative) |

Laboratory Validation Protocol for Sensor Development

Controlled laboratory studies provide essential foundational validation for eating detection algorithms before free-living deployment [9].

Objective: To establish baseline performance metrics for swallowing and eating detection in controlled environments.

Participant Recruitment:

- Sample Size: 20-30 participants per validation study

- Stratification: Include participants across BMI categories to test generalizability

Experimental Setup:

- Standardized Meals: Fixed food types with varying textures (solid vs. liquid)

- Sensor Placement: Neck-worn piezoelectric sensor array positioned for optimal swallow detection

- Ground Truth: Concurrent video recording with manual annotation of swallowing events

Data Collection Parameters:

- Piezoelectric Sensors: Vibration recording from electrical charge produced during sensor deformation

- Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs): Motion capture during feeding gestures

- Signal Processing: Spectrogram analysis for swallow identification

Performance Validation:

- Classification Algorithms: Trained on resulting voltages and inertial data streams

- Validation Method: Leave-one-subject-out cross-validation

- Outcome Measures: Swallow detection for solids (F=0.864) and liquids (F=0.837)

Compositional Detection Logic for Complex Eating Behaviors

Eating detection requires a compositional approach where systems understand behavior emerging from multiple, easier-to-sense behavioral or biometric features [9]. The logical framework for distinguishing eating from confounding activities follows a decision tree based on sensor inputs.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Eating Detection Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Wearable Eating Detection Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Technology | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck-Worn Sensors | Piezoelectric Sensor Array | Detects swallows via neck vibration | Embedded in necklace for snug fit [9] |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Captures feeding gestures and body posture | Multi-axis accelerometer/gyroscope [9] | |

| Complementary Wearables | Optical Tracking Sensors (OCO) | Monitors facial muscle activations | Embedded in smart glasses frames [16] |

| Activity-Oriented Camera (AOC) | Records food-related actions while preserving privacy | HabitSense with thermal triggering [17] [14] | |

| Jawline Motion Sensor | Detects chewing via jaw movement | Button-sized sensor on jawline [18] | |

| Ground Truth Collection | Wearable Camera Systems | Provides video verification of eating episodes | Thermal-sensing bodycam [17] [15] |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) | Captures psychological and contextual factors | Smartphone app for pre/post-meal surveys [15] | |

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Validates food intake and meal timing | Dietitian-administered standardized protocol [15] | |

| Analytical Tools | Machine Learning Frameworks | Classifies eating episodes from sensor data | XGBoost for overeating detection [15] |

| Signal Processing Algorithms | Extracts features from raw sensor data | Spectrogram analysis for swallow detection [9] |

Study Deployment Workflow: From Laboratory to Free-Living Environments

Successful translation of eating detection systems requires progressive validation across environments of increasing ecological validity. The following workflow illustrates this deployment pipeline.

Implementation Framework for Addressing Key Challenges

Sample Selection Strategy

Representative Recruitment:

- Population-Specific Sampling: Prioritize inclusion of target clinical populations (e.g., individuals with obesity) rather than convenience samples of healthy individuals [9]

- Stratified Enrollment: Ensure demographic and anthropometric diversity to test device performance across body types and eating behaviors

Handling Body Variability:

- Modular Design: Implement configurable form factors to accommodate different neck sizes and body shapes [9]

- Sensor Placement Protocols: Standardize positioning procedures to minimize inter-participant measurement variance

Transdisciplinarity Management

Team Composition:

- Integrated Expertise: Assemble teams encompassing medical science, engineering, computer science, and clinical research staff [9]

- Clear Role Delineation: Establish defined responsibilities while maintaining collaborative problem-solving channels

Technology Development Approach:

- Build vs. Buy Decisions: Carefully evaluate trade-offs between commercial technologies (limited flexibility) and custom solutions (development overhead) [9]

- Iterative Prototyping: Implement rapid cycles of development and validation with continuous feedback from all disciplinary perspectives

Real-World Realism Enhancement

Progressive Ecological Validation:

- Staged Deployment: Transition systematically from laboratory to semi-controlled to free-living environments [9] [18]

- Contextual Diversity: Ensure testing across various eating contexts (home, restaurant, social gatherings) to capture behavioral variability

Ground Truth Methodologies:

- Multi-Modal Verification: Combine wearable cameras, EMAs, and dietitian recalls to establish comprehensive ground truth [15]

- Privacy-Preserving Design: Implement activity-oriented recording (e.g., thermal-triggered cameras) to balance data quality with participant comfort [17] [14]

Behavioral Authenticity:

- Habituation Periods: Allow extended device wear before formal data collection to minimize observation effects [9]

- Unobtrusive Sensing: Minimize device bulk and visibility to support natural eating behaviors

The frameworks and protocols outlined provide a roadmap for developing neck-worn eating detection systems that successfully navigate the critical challenges of sample selection, transdisciplinarity, and real-world realism. Implementation of these structured approaches will accelerate the translation of wearable sensing technologies from research prototypes to validated clinical instruments for obesity treatment and dietary behavior research.

Building the System: Sensor Integration, Algorithm Development, and Clinical Workflow

The development of automated dietary monitoring systems represents a significant frontier in mobile health (mHealth). Among various approaches, neck-worn eating detection systems have emerged as a promising platform due to their proximity to relevant physiological and behavioral signals. These systems face the fundamental challenge of achieving robust detection accuracy across diverse populations and real-world conditions, which single-sensor architectures often fail to address. Multi-sensor fusion has consequently become an essential architectural paradigm, integrating complementary data streams to overcome the limitations of individual sensing modalities. This architecture enables systems to distinguish eating from confounding activities through compositional behavior analysis, where eating is recognized as the temporal co-occurrence of multiple component actions such as chewing, swallowing, and feeding gestures [9]. This application note details the hardware architecture, sensor modalities, experimental protocols, and validation methodologies for implementing robust multi-sensor fusion in neck-worn eating detection systems, framed within the broader context of developing clinically viable dietary monitoring tools.

Core Sensor Modalities and Fusion Architecture

The effectiveness of a neck-worn eating detection system hinges on the strategic selection and integration of complementary sensor modalities. The following table summarizes the primary sensors employed, their measured parameters, and their specific roles in detecting components of eating behavior.

Table 1: Core Sensor Modalities in Neck-Worn Eating Detection Systems

| Sensor Type | Measured Parameter | Target Behavior | Role in Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximity Sensor | Distance to chin/neck [19] | Jaw movement during chewing [19] | Detects periodic chewing sequences; primary indicator of mastication. |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | Acceleration, orientation [19] | Head tilt (Lean Forward Angle), feeding gestures [9] [19] | Identifies body posture indicative of eating; distinguishes eating from drinking [9]. |

| Ambient Light Sensor | Light intensity [19] | Hand-to-mouth gestures occluding light [19] | Provides supplementary context for feeding gestures. |

| Piezoelectric Sensor | Skin vibrations [9] | Swallowing events (deglutition) [9] | Captures swallows of solids and liquids; a direct physiological correlate of intake. |

The logical relationship and data flow between these sensors and the fusion process can be visualized as a hierarchical architecture.

System Architecture and Data Flow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and validation of a multi-sensor fusion system for eating detection require a specific set of hardware, software, and methodological "reagents." The following table details these essential components and their functions within the research workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for System Development

| Category | Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Platform | Custom Necklace/Patch | Embedded proximity, ambient light, IMU sensors [19] | Form-factor for sensor integration and participant wear. |

| Data Acquisition Unit | On-board memory, Bluetooth/Wi-Fi module | Captures and stores/transmits raw sensor data streams. | |

| Ground Truth Collection | Wearable Camera (e.g., egocentric camera) | First-person view [9] [19] | Provides objective, frame-level ground truth for eating episodes in free-living studies. |

| Mobile Application | Custom app for self-reporting [9] [20] | Enables participant-initiated meal logging (e.g., start/end times). | |

| Data Processing & Analysis | Signal Processing Toolkit | MATLAB, Python (NumPy, SciPy) | For filtering, segmenting, and extracting features from raw sensor data. |

| Machine Learning Library | Python (scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch) | For building and training classification and fusion models (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, Neural Networks) [20]. | |

| Validation Tools | Video Annotation Software | ELAN, ANVIL | To manually label eating episodes and micro-actions from video ground truth. |

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

Rigorous validation across controlled and free-living settings is critical to demonstrate system robustness. The experimental workflow progresses from initial feasibility studies to comprehensive in-the-wild deployments.

Experimental Workflow for Validation

Protocol 1: Controlled In-Lab Feasibility Study

This protocol establishes a baseline performance benchmark under ideal conditions [9].

- Objective: To validate the core functionality of individual sensors and the initial fusion algorithm for detecting specific micro-actions like chewing and swallowing.

- Participant Recruitment: ~20-30 participants. It is crucial to include individuals with diverse Body Mass Index (BMI) to assess the impact of body morphology on sensor performance [9] [19].

- Experimental Procedure: Participants consume standardized meals (including solids and liquids) in a laboratory setting. The session is recorded using high-quality video cameras from multiple angles to provide precise ground truth.

- Ground Truth Collection: Video recordings are manually annotated by trained researchers to label the exact timestamps of swallows, bites, and chews [9].

- Key Metrics: F1-score, precision, and recall for detecting swallows and chewing sequences. Example: A piezo-based system achieved F-scores of 0.864 for solid and 0.837 for liquid swallows in lab settings [9].

Protocol 2: Semi-Free-Living (Exploratory) Study

This protocol tests the system in a more natural, yet still somewhat controlled, environment [19].

- Objective: To evaluate the integrated system's performance in a realistic setting and identify usability issues before full deployment.

- Setting: A controlled environment like a hospital ward or a designated living area where participants can move freely but are intermittently monitored.

- Procedure: Participants wear the system for a defined period (e.g., one waking day) and consume meals as they choose in the designated area. They may use a mobile application to self-report the start and end of meals.

- Ground Truth: A combination of wearable camera footage and self-reports is used for ground truth annotation [19].

- Key Metrics: Per-episode F1-score for eating event detection, battery life duration, and qualitative feedback on comfort and usability. Example: The NeckSense system achieved an F1-score of 81.6% for eating episodes in a semi-free-living setting [19].

Protocol 3: Full Free-Living Validation Study

This is the most rigorous test, evaluating the system's performance in a participant's daily life [9] [19] [20].

- Objective: To assess the real-world efficacy, robustness to confounding activities, and generalizability of the system across a diverse population.

- Participant Recruitment: A larger cohort (e.g., 60 participants) that includes the target population, such as individuals with obesity, who are most likely to benefit from dietary monitoring [9] [19].

- Procedure: Participants wear the system for multiple consecutive days (e.g., 2+ days) in their homes and workplaces without any restrictions on their activities, meals, or locations.

- Ground Truth Collection: The primary ground truth is obtained from a wearable camera (e.g., egocentric camera). To manage privacy, the camera may be set to record at regular intervals or be controlled by the participant. The video is later annotated to mark eating episodes [9] [19].

- Key Metrics:

- Performance: F1-score for eating episode detection. Example: Performance typically drops in free-living settings; one study reported an F1-score of 77.1% for episodes [19].

- Engineering: Battery life (target: >15 hours for a full waking day [19]), data storage integrity, and device adherence.

- Robustness: Rate of false positives triggered by confounding activities (e.g., talking, smoking).

Performance Data and Comparison

The following table synthesizes quantitative performance data from key studies, illustrating the progression from lab to real-world validation and the impact of multi-sensor fusion.

Table 3: Performance Comparison Across Development Stages

| Study Type | Sensing Modalities | Primary Target | Reported Performance (F1-Score) | Key Challenges Highlighted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Lab [9] | Piezoelectric, Accelerometer | Swallow Detection | 87.0% (Swallow) | Limited external validity; fails to generalize to real-world. |

| Semi-Free-Living [19] | Proximity, Ambient Light, IMU | Eating Episodes | 81.6% (Episode) | Usability concerns; need for comfort and longer battery life. |

| Full Free-Living [19] | Proximity, Ambient Light, IMU | Eating Episodes | 77.1% (Episode) | Confounding activities, body variability, environment noise. |

| Wrist-Worn Free-Living [20] | Accelerometer, Gyroscope | Eating Segments | 82.0% (Segment) | Demonstrates viability of an alternative, less obtrusive form-factor. |

The drop in performance from semi-free-living to full free-living conditions underscores the significant challenge posed by completely unconstrained environments. Multi-sensor fusion is the key strategy to mitigate this drop, as it increases the system's resilience to confounding factors [9]. Furthermore, models trained exclusively on populations with normal BMI show degraded performance when tested on individuals with obesity, emphasizing the necessity of inclusive participant recruitment throughout all validation stages [19].

Machine Learning Pipelines for Recognizing Eating Gestures and Swallows

The automated detection of eating gestures and swallows represents a significant advancement in objective dietary monitoring and clinical dysphagia screening. For researchers developing neck-worn eating detection systems, machine learning (ML) pipelines offer the potential to transform raw, multi-sensor data into actionable insights about ingestive behavior. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols for implementing such pipelines, framed within the context of neck-worn system development. We focus on two primary sensing modalities: acoustic sensing for swallow detection and multi-sensor fusion for eating gesture recognition, detailing the ML workflows that underpin their functionality for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

ML Pipeline for Swallow Detection via Cervical Auscultation

Digital cervical auscultation (CA) involves recording swallowing sounds from the neck. Its clinical application has been limited by the need for manual segmentation of swallow events by trained experts, a process that is both time-consuming and subjective [21] [22]. Automated ML pipelines can address this bottleneck.

Quantitative Performance of Swallow Detection Models

Recent studies utilizing transfer learning have demonstrated high accuracy in automatically segmenting and detecting swallows across different populations. The table below summarizes key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance of Swallow Detection Models Using Transfer Learning

| Population | Sample Size | Model Architecture | Overall Accuracy | Sensitivity/Recall | Specificity/Precision | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm Neonates | 78 patients | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) + Feedforward Network | 94% | 95% (Bottle), 95% (Breast) | 96% (Bottle), 92% (Breast) | [21] |

| Children (Typical Development & Feeding Disorders) | 35 patients | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) + Feedforward Network | 91% | 81% | 79% | [22] |

Experimental Protocol: Swallow Sound Segmentation

Objective: To train and validate a model for the automated segmentation of swallow sounds from digital cervical auscultation recordings.

Materials:

- Digital Stethoscope or Acoustic Sensor: High-fidelity recorder placed on the neck adjacent to the laryngopharynx.

- Audio Recording System: Device to capture and digitize swallow sound data at a sufficient sampling rate (e.g., ≥44.1 kHz).

- Annotation Software: For manual labeling of swallow events by clinical experts to create ground truth.

- Computing Hardware: GPU-enabled workstation for efficient model training.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing:

- Collect swallow sound recordings from the target population (e.g., preterm neonates, children, adults) during controlled feeding sessions [21] [22].

- Manually segment and label all swallow events in the audio waveforms to create a ground-truth dataset. This is a critical and time-intensive step.

- Preprocess the raw audio data, which may include filtering, noise reduction, and amplitude normalization.

Feature Extraction & Model Training (Transfer Learning):

- Utilize a pre-trained Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN), originally designed for general audio event classification, as a feature extractor [21] [22].

- Input raw or preprocessed swallow audio data into the base DCNN to generate embedding vectors that represent the salient features of the audio segments.

- Use these embedding vectors to train a downstream classifier, such as a feedforward neural network, to perform the binary classification of "swallow" vs. "non-swallow" for a given audio segment [21] [22].

Model Validation:

- Evaluate model performance using hold-out test sets or cross-validation, reporting standard metrics including accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, and precision [21] [22].

- Test model generalizability by evaluating performance on swallows not present in the training set (e.g., saliva swallows in children) [22].

Workflow Diagram: Swallow Detection Pipeline

ML Pipelines for Eating Gesture Recognition

Beyond swallow detection, broader eating activity can be recognized by detecting the gestures associated with eating, such as chewing and hand-to-mouth movements. Here, we contrast neck-worn and wrist-worn sensing approaches.

Quantitative Performance of Eating Detection Systems

The following table compares the performance of different wearable systems for eating detection, highlighting the trade-offs between form factor and capability.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Eating Detection Systems

| System (Form Factor) | Sensing Modalities | Key ML Approach | Performance (F1-Score/Accuracy) | Testing Environment | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeckSense (Necklace) | Proximity, Ambient Light, IMU | Sensor Fusion & Clustering | F1: 81.6% (Episode) | Free-Living | [19] |

| SPLENDID (Ear-worn) | Air Microphone, PPG | Pattern Recognition on Sensor Signals | Accuracy: 93.8% (Lab) | Laboratory & Semi-Controlled | [23] |

| Smartwatch-Based (Wrist) | Accelerometer, Gyroscope | Fusion of Deep & Classical ML | F1: 82.0% (Segment) | In-the-Wild | [20] |

| Smartwatch-Based (Wrist) | Accelerometer | Hand Movement Classification | F1: 87.3% (Meal) | In-the-Wild | [24] |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Sensor Eating Episode Detection

Objective: To detect and cluster eating episodes from a continuous stream of data from a multi-sensor necklace.

Materials:

- Multi-Sensor Necklace: A device housing a proximity sensor (to detect jaw movement), an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) (to capture lean-forward angle and feeding gestures), and an ambient light sensor (to detect hand-to-mouth gestures) [19].

- Data Logger: A companion device (e.g., smartphone or custom hardware) for data storage, processing, and/or transmission.

Methodology:

- Data Collection & Labeling:

- Deploy the necklace to participants in free-living or semi-controlled studies for extended periods (e.g., multiple days) [19].

- Collect ground truth data through self-reports, video recordings, or researcher annotations to mark the start and end of eating episodes.

Feature Extraction & Eating Activity Detection:

- Extract features from the sensor streams. The proximity sensor signal can be analyzed for periodicity associated with chewing using algorithms like the longest periodic subsequence [19].

- Fuse features from all sensors (proximity, ambient light, IMU). The combination of leaning forward, feeding gestures, and periodic chewing is indicative of an "in-moment eating activity" [19].

- Train a classifier (e.g., an SVM or neural network) on these fused features to identify chewing sequences or individual eating gestures.

Episode Clustering:

- Cluster the predicted chewing/eating activity sequences into distinct eating episodes. This step aggregates fine-grained detections into full meals [19].

Validation:

- Validate performance at both the fine-grained per-second level and the coarse-grained per-episode level against the ground truth, reporting metrics like F1-score, precision, and recall [19].

Workflow Diagram: Multi-Sensor Eating Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers replicating or building upon these experiments, the following table catalogs essential "research reagents"—the key hardware and software components used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Eating Detection System Development

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Models | Function in the Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Sensors | Digital Stethoscope, Throat Microphone [21] [22] | Captures swallowing sounds from the laryngopharynx for cervical auscultation. |

| Motion & Proximity Sensors | Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), Proximity Sensor [19] | Detects jaw movement, head tilt (lean-forward angle), and feeding gestures. |

| Optical Sensors | Photoplethysmogram (PPG), Ambient Light Sensor [23] [19] | PPG may detect chewing via blood volume changes in the ear; ambient light detects hand-to-mouth gestures. |

| Data Acquisition Hardware | Custom Necklace Platform (e.g., NeckSense [19]), Smartwatch (e.g., Pebble [24]), Data Logger | Houses sensors, collects raw data, and often performs preliminary processing or data transmission. |

| Core ML Models & Architectures | Pre-trained Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) [21] [22], Feedforward Neural Network, SVM [20] | DCNN for feature extraction from audio; downstream classifiers for final activity detection. |

| Data Processing & Annotation Tools | Audio/Video Annotation Software, Signal Processing Libraries (Python, MATLAB) | Creates ground-truth labels for model training and validation; preprocesses sensor signals. |

The development of automated dietary monitoring (ADM) systems, particularly neck-worn sensors, represents a significant advancement in objective nutrition assessment technology. These systems address critical limitations of traditional self-reported methods, which are prone to recall bias and substantial under-reporting [25]. Research demonstrates that passive wearable sensors can generate supplementary data that improve the validity of dietary intake information collected in naturalistic settings [25]. This application note details how neck-worn eating detection systems integrate with the standardized Nutrition Care Process (NCP), providing researchers with protocols for enhancing nutrition assessment, diagnosis, intervention, and monitoring/evaluation.

The NCP framework provides a systematic problem-solving method for nutrition and dietetics professionals to deliver high-quality care through four distinct steps: Nutrition Assessment and Reassessment, Nutrition Diagnosis, Nutrition Intervention, and Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation [26] [27]. Neck-worn sensors like NeckSense, a multi-sensor necklace, have demonstrated capability to automatically detect eating episodes with F1-scores of 81.6% in semi-free-living settings and 77.1% in completely free-living environments [19]. This technology offers unprecedented opportunities to capture fine-grained temporal patterns of eating behavior that were previously inaccessible through traditional assessment methods.

Neck-worn eating detection systems utilize multiple integrated sensors to capture physiological and behavioral signals associated with food consumption. The core technology typically includes:

- Proximity sensors that measure distance to the chin, detecting jaw movements during chewing

- Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) that capture head orientation and lean-forward angles

- Ambient light sensors that provide contextual environmental data

- Acoustic sensors in some systems that detect chewing and swallowing sounds

These systems employ sensor fusion algorithms to combine multiple data streams for improved detection accuracy. For instance, NeckSense demonstrated that augmenting proximity sensor data with ambient light and IMU sensor data improved eating episode detection by 8% compared to using proximity sensing alone [19]. This multi-sensor approach enables reliable detection of chewing sequences, which serve as fundamental building blocks for identifying complete eating episodes.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Neck-Worn Eating Detection Systems

| Metric | Semi-Free-Living Performance | Completely Free-Living Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Episode F1-Score | 81.6% | 77.1% | [19] |

| Fine-Grained (Per-Second) F1-Score | 76.2% | 73.7% | [19] |

| Battery Life | 13 hours | 15.8 hours | [19] |

| Participant Compliance | High across diverse BMI populations | Maintained with improved design | [19] |

Integration with Nutrition Assessment

Enhanced Data Collection Capabilities

Nutrition Assessment, the first step of the NCP, involves "collecting and documenting information such as food or nutrition-related history" [26]. Neck-worn sensors significantly enhance this process by passively capturing objective eating behavior data that eliminates reliance on memory-based reporting. These systems can detect and record precise meal start times, duration, chewing rate, bite count, and hand-to-mouth gestures [19] [14]. This granular temporal data enables researchers to identify eating patterns that traditional methods often miss, particularly unstructured eating occasions like snacks and grazes.

Research shows that a substantial proportion of adults have moved away from conventional three-meal patterns toward smaller, more frequent meals and snacks [28]. These less-structured eating occasions are frequently omitted in self-reported dietary assessments due to forgetfulness or conscious under-reporting [28]. Neck-worn sensors address this critical gap by providing continuous monitoring across the entire waking day, capturing all eating episodes regardless of timing or context.

Assessment Protocol

Objective: To comprehensively assess temporal eating patterns using neck-worn sensor technology.

Materials:

- Neck-worn eating detection sensor (e.g., NeckSense prototype)

- Data processing unit with machine learning classification capabilities

- Ground truth validation tools (e.g., structured food diaries, timestamped photos)

Methodology:

- Device Calibration: Fit the neck-worn sensor to ensure proper positioning for proximity detection from the chin. Verify all sensor functionalities through standardized movement tests.

- Data Collection: Deploy sensors for a minimum 7-day monitoring period to capture weekday and weekend variations. Collect continuous sensor data including proximity, IMU, and ambient light readings.

- Ground Truth Annotation: Implement time-synchronized food logging through mobile applications with push notifications at 3-hour intervals. Capture before-and-after meal photographs for portion size estimation.

- Signal Processing: Apply bandpass filters to raw sensor data to reduce motion artifacts and environmental noise.

- Feature Extraction: Calculate time-domain features including mean, variance, and periodicity of chewing sequences from proximity sensors. Extract spatial features including lean-forward angle from IMU data.

- Meal Episode Clustering: Apply density-based clustering algorithms to group detected chewing sequences into discrete eating episodes based on temporal proximity.

Validation: Compare algorithm-detected eating episodes with ground truth annotations using precision, recall, and F1-score metrics. Cross-validate with participant-completed 24-hour dietary recalls administered by trained researchers.

Integration with Nutrition Diagnosis

Identifying Problematic Eating Patterns

The Nutrition Diagnosis step involves "naming the specific problem" based on assessment data [26]. Neck-worn sensors provide objective data to support specific nutrition diagnoses by identifying problematic eating behaviors that contribute to poor health outcomes. Research using multi-sensor systems has identified five distinct overeating patterns: Take-out Feasting, Evening Restaurant Reveling, Evening Craving, Uncontrolled Pleasure Eating, and Stress-Driven Evening Nibbling [14]. These patterns reflect the complex interaction between environment, emotion, and habit that drives excessive energy intake.

Sensor data enables precise characterization of eating microstructure, including eating rate, chewing frequency, and meal duration, which may indicate specific nutrition problems. For example, rapid eating rates detected through accelerated chewing cycles may correlate with inadequate chewing and swallowing difficulties [28]. Similarly, irregular meal timing patterns captured through temporal analysis of eating episodes can support diagnoses related to disordered eating patterns.

Diagnostic Decision Support Protocol

Objective: To transform sensor-derived eating metrics into standardized nutrition diagnoses.

Materials:

- Processed eating episode data from neck-worn sensors

- NCP Terminology (NCPT) reference guide

- Diagnostic algorithm for pattern classification

Methodology:

- Data Integration: Compile sensor-derived metrics including eating frequency, timing, duration, and chewing rate across the monitoring period.

- Pattern Recognition: Apply unsupervised learning algorithms to identify clusters of similar eating behaviors across days. Flag statistically significant deviations from established patterns.

- Etiology Analysis: Correlate eating patterns with contextual data including location (via Bluetooth beacons), physical activity (via wrist-worn accelerometers), and self-reported mood.

- Diagnosis Formulation: Map identified patterns to standardized NCPT diagnoses using decision rules:

- Cluster late-evening eating episodes with high energy density → "Evening Craving" pattern [14]

- Detect rapid eating rate with large bite count → "Excessive energy intake"

- Identify prolonged between-meal intervals → "Irregular meal pattern"

- PES Statement Development: Structure Problem, Etiology, and Signs/Symptoms statements using sensor data as objective evidence.

Validation: Compare algorithm-generated diagnoses with clinical assessments by registered dietitians. Evaluate diagnostic accuracy through blinded review of randomly selected cases.

Integration with Nutrition Intervention

Real-Time Intervention Delivery

Nutrition Intervention involves selecting "the nutrition intervention that will be directed to the root cause of the nutrition problem" [26]. Neck-worn sensors enable innovative just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) that deliver personalized feedback when problematic eating is detected. These systems can trigger real-time notifications through connected devices to encourage behavior modification at teachable moments [19]. For example, a sensor detecting rapid eating rate can prompt the user to slow down, while detection of an untimely eating episode might deliver a mindfulness reminder.

Research demonstrates support among clinicians for mobile adaptive interventions that use contextual inputs, such as detection of an eating episode or number of mouthfuls consumed, to adapt the content and timing of interventions [19]. This approach moves beyond one-size-fits-all solutions toward a world where "health technology feels less like a prescription and more like a partnership" [14].

Intervention Protocol

Objective: To implement sensor-triggered interventions for modifying problematic eating behaviors.

Materials:

- Real-time eating detection system

- Mobile application for intervention delivery

- Intervention content library

Methodology:

- Intervention Design: Develop appropriate messaging strategies for specific eating patterns:

- For rapid eating: "You're eating quite quickly. Try placing your utensil down between bites."

- For late-evening eating: "This is your third evening snack this week. Are you eating out of hunger or habit?"

- Trigger Configuration: Program detection thresholds for intervention delivery:

- Eating rate > 45 bites/minute triggers mindfulness prompt

- Eating episode after 9:00 PM triggers alternative activity suggestion

- Detection of continuous eating > 20 minutes triggers satiety check-in

- Delivery System: Establish secure Bluetooth communication between neck-worn sensor and smartphone application for real-time notification delivery.

- Contextual Adaptation: Modify intervention timing and content based on additional contextual factors including location and preceding activities.

- Response Monitoring: Track user engagement with interventions and subsequent eating behavior modifications.

Evaluation: Measure intervention effectiveness through A-B testing designs comparing behavior change between intervention and control periods. Assess long-term efficacy through repeated monitoring phases.

Integration with Monitoring and Evaluation

Objective Progress Tracking

Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation determines "if the client has achieved, or is making progress toward, the planned goals" [26]. Neck-worn sensors provide continuous objective data to evaluate intervention effectiveness without relying on self-report. These systems can detect subtle changes in eating microstructure, such as reduced eating rate or more consistent meal timing, that indicate progress toward nutritional goals [19]. This enables more precise evaluation than traditional methods and allows for timely intervention adjustments.

The continuous monitoring capability of these systems supports longitudinal evaluation of eating behavior changes, providing rich data on adherence to nutritional recommendations and sustainability of behavior modifications. This objective tracking is particularly valuable between clinical consultations, extending the dietitian's ability to monitor patients in their natural environments [28].

Evaluation Protocol

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate intervention effectiveness using sensor-derived eating metrics.

Materials:

- Baseline and follow-up sensor data

- Statistical analysis software

- Goal attainment scaling framework

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Calculate reference values for key eating metrics during initial assessment phase (minimum 7 days).

- Goal Setting: Establish specific, measurable targets for improvement based on baseline data and clinical goals:

- Reduce eating rate by 15%

- Decrease after-8pm eating episodes by 80%

- Increase meal regularity index by 25%

- Continuous Monitoring: Collect sensor data throughout intervention period with particular emphasis on first 2 weeks and final 2 weeks.

- Progress Analysis: Compare eating metrics between baseline and intervention phases using paired statistical tests:

- Paired t-tests for normally distributed metrics (eating rate)

- McNemar's tests for binary outcomes (presence of late-night eating)

- Goal Attainment Scaling: Calculate proportion of established goals achieved, partially achieved, or not achieved.

- Adaptation Decision Points: Predefine evaluation timepoints (e.g., weekly) for determining whether interventions require modification based on progress metrics.

Reporting: Generate comprehensive evaluation reports with visualizations of trends in key metrics over time. Highlight clinically significant changes beyond statistical significance.

Experimental Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Neck-Worn Eating Detection Studies

| Item | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| NeckSense Prototype | Multi-sensor necklace with proximity, IMU, and ambient light sensors [19] | Primary data collection device for eating detection in free-living studies |

| Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) | 9-axis (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer) with ±4g/±500dps ranges [19] | Captures head movement and lean-forward angle during eating episodes |

| Infrared Proximity Sensor | 10-80cm detection range with I²C interface [19] | Measures jaw movement through distance-to-chin variation during chewing |

| Annotation Software | Custom video coding platform with timestamp synchronization [19] | Ground truth labeling of eating episodes from first-person video recordings |

| Signal Processing Library | Python-based with bandpass filters and feature extraction algorithms [19] | Processes raw sensor data into meaningful eating behavior features |

| Machine Learning Framework | Scikit-learn or TensorFlow with random forest/CNN classifiers [5] | Classifies sensor data into eating/non-eating activities and detects patterns |

Neck-worn eating detection systems represent a transformative technology for enhancing the precision and personalization of the Nutrition Care Process. These systems address fundamental limitations of traditional dietary assessment methods by providing objective, continuous monitoring of eating behaviors in naturalistic environments. The integration pathways and experimental protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with a framework for leveraging this technology across all NCP steps—from comprehensive nutrition assessment through targeted intervention and objective evaluation.

Future research should focus on improving detection algorithms for diverse populations, enhancing battery life for extended monitoring, and developing more sophisticated just-in-time adaptive interventions. As these technologies evolve, they hold significant promise for advancing nutritional science and enabling more effective, data-driven nutrition care.

Leveraging Event Detection for Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)

Application Notes: Integrating Event Detection with EMA

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) is a methodology for the repeated, real-time collection of participant data in their natural environments. The integration of automated event detection significantly enhances EMA by moving beyond traditional, participant-initiated reports to passive, objective triggering of assessments. This is particularly transformative in the context of neck-worn eating detection systems, which can identify the onset of eating behaviors and automatically prompt EMAs to capture critical contextual data. This approach minimizes recall bias and provides unparalleled insights into the behavioral, environmental, and psychological antecedents of solid food intake [29] [30].

The core advantage lies in the ability to capture data precisely when a target event occurs. For example, a system detecting the onset of mastication can prompt an user to report their current emotional state, location, or social context. This objective triggering is crucial for investigating behavioral patterns such as the five distinct overeating profiles identified by recent research: Take-out Feasting, Evening Restaurant Reveling, Evening Craving, Uncontrolled Pleasure Eating, and Stress-Driven Evening Nibbling [14].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent EMA and sensor studies, providing a evidence base for designing event-driven protocols.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data from EMA and Sensor Studies

| Study Focus / Metric | Key Finding / Value | Implications for Event-Driven EMA |

|---|---|---|

| EMA Compliance (General) [29] | Average completion: 83.8% (28,948/34,552 prompts) | High compliance is achievable with well-designed protocols. |

| EMA Compliance (Substance Use) [30] | Pooled compliance: 75.06% (95% CI: 72.37%, 77.65%) | Clinical populations may show lower compliance, requiring tailored approaches. |

| Impact of Design Factors [29] | No significant main effects on compliance from survey length (15 vs. 25 questions), frequency (2 vs. 4/day), or prompt schedule (random vs. fixed). | Design flexibility allows prioritization of scientific questions over strict adherence to a "gold standard" protocol. |