Novel Sources of Bioactive Compounds in 2025: A Scientific Review for Next-Generation Drug Discovery

This article synthesizes the most current advancements in the discovery of novel bioactive compounds, a field rapidly evolving to meet global demands for sustainable and effective therapeutics.

Novel Sources of Bioactive Compounds in 2025: A Scientific Review for Next-Generation Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article synthesizes the most current advancements in the discovery of novel bioactive compounds, a field rapidly evolving to meet global demands for sustainable and effective therapeutics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from newly identified sources—including underutilized plants, marine organisms, and agro-industrial by-products—to cutting-edge green extraction and functionalization technologies. The scope critically examines methodological innovations for enhancing bioavailability, addresses key challenges in compound stabilization and regulatory compliance, and validates bioactivity through emerging in vitro, in vivo, and clinical evidence. The review concludes by outlining future trajectories, emphasizing the convergence of AI-driven discovery, precision nutrition, and sustainable sourcing in shaping the next frontier of biomedical research.

Beyond the Conventional: Mapping Novel and Sustainable Sources of Bioactives

The valorization of agri-food waste (AFW) represents a transformative approach within the circular economy, converting underutilized biomass into a rich source of bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical applications [1] [2]. These by-products, generated from agricultural residues, food processing discards, and post-harvest losses, are abundant in polyphenols, carotenoids, bioactive peptides, and dietary fibers [1] [3]. These molecules exhibit demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticarcinogenic properties, offering a sustainable and economically viable strategy for drug discovery and development [2] [4]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the predominant bioactive compounds in AFW streams, details advanced and sustainable extraction methodologies, and outlines their mechanistic roles in disease prevention and therapy, providing a scientific framework for their integration into pharmaceutical research and development.

The agri-food sector generates billions of tonnes of waste annually, posing significant environmental, economic, and ethical challenges [3]. Concurrently, the search for novel, sustainable, and effective bioactive compounds for the pharmaceutical industry is intensifying. The valorization of AFW creates a synergistic nexus between these two domains, transforming waste into a valuable resource for drug development [2]. This paradigm shift is driven by the understanding that non-edible portions of fruits, vegetables, grains, and other crops often contain higher concentrations of bioactive compounds than the marketed parts [3] [4]. For instance, olive pomace possesses a polyphenolic profile that can be richer than the oil itself per unit of weight [4]. Framed within the context of 2025 research on novel bioactive sources, this approach aligns with global sustainability goals, promotes a circular bioeconomy, and offers a pathway to reduce the ecological footprint of the pharmaceutical sector while unlocking new therapeutic avenues [1] [2].

Key Bioactive Compounds and Their Pharmaceutical Potential

Agri-food by-products are a complex matrix of health-promoting phytochemicals. The table below summarizes the most studied bioactive compounds, their primary sources, and their documented biological activities relevant to pharmaceutical science.

Table 1: Key Bioactive Compounds in Agri-Food By-Products and Their Pharmaceutical Potential

| Bioactive Compound Class | Common Agri-Food Sources | Documented Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols (e.g., flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins) | Fruit pomace (apple, grape, pomegranate), vegetable peels, olive pomace, cereal bran [1] [3] [4] | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, cardioprotective, neuroprotective [1] [4] |

| Carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene, lycopene) | Tomato peels, carrot pomace, watermelon rind, corn husks [1] [5] | Antioxidant, anticarcinogenic (e.g., prostate cancer), precursor to Vitamin A [1] |

| Bioactive Peptides and Proteins | Oilseed meals, cereal bran, whey, fish processing by-products [1] [6] | Antihypertensive (ACE-inhibitory), antioxidant, antimicrobial, immunomodulatory [1] |

| Dietary Fibers (Soluble and Insoluble) | Citrus peel, apple pomace, oat bran, vegetable trimmings [1] [6] | Cholesterol-lowering, prebiotic (modulates gut microbiota), improves digestive health [1] [6] |

Advanced Extraction and Recovery Methodologies

The efficient recovery of bioactives from AFW is a critical step, with modern techniques favoring green, efficient, and scalable processes over conventional methods like Soxhlet extraction [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds from AFW

| Extraction Technique | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Uses supercritical CO₂ as a solvent to dissolve target compounds [1] [3]. | Solvent-free, high selectivity, preserves thermolabile compounds [1] [7]. | Carotenoids from carrot peels; volatile compounds from mandarin peel [1] [7]. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Dielectric heating causes intracellular heating, rupturing cell walls [1] [3]. | Rapid, reduced solvent consumption, high efficiency [1]. | Phenolic compounds from pomegranate peels [3]. |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Cavitation bubbles collapse, disrupting cell walls and enhancing mass transfer [1] [3]. | Low-temperature, energy-efficient, reduces extraction time [1] [7]. | Polyphenols from blueberry pomace; phenolic acids from Morus alba leaves [3] [7] [6]. |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | Uses liquid solvents at high temperatures and pressures [1]. | Efficient, automated, uses green solvents like water [1]. | Bioactive compounds from various plant matrices [1]. |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) | Specific enzymes degrade plant cell wall components (e.g., cellulose, pectin) [1] [3]. | Mild conditions, highly selective, ideal for bound compounds [1]. | Dietary fibers from orange peel; olive pomace [1] [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Polyphenols from Berry Pomace

This protocol is adapted from recent research on the valorization of fruit processing by-products [3] [7] [6].

- Objective: To efficiently extract polyphenolic compounds from blueberry or grape pomace.

- Materials:

- Raw Material: Dried and milled berry pomace.

- Solvent: Aqueous ethanol (e.g., 50-70% v/v).

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath or probe system, centrifuge, vacuum evaporator, lyophilizer, analytical balance.

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Dry the pomace at 50°C until constant weight. Mill and sieve to a uniform particle size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm).

- Extraction: Accurately weigh 5 g of pomace into a glass vessel. Add 100 mL of 60% aqueous ethanol. Subject the mixture to ultrasonic treatment using a probe system (e.g., 200 W, 24 kHz) for 15 minutes, maintaining the temperature at 40°C using a water bath.

- Separation: Centrifuge the resulting mixture at 8000 rpm for 15 minutes. Collect the supernatant.

- Concentration: Concentrate the supernatant under reduced pressure at 40°C using a rotary evaporator to remove ethanol.

- Lyophilization: The aqueous residue is frozen at -80°C and lyophilized to obtain a free-flowing polyphenol-rich powder for subsequent analysis and bioactivity testing.

- Analysis: The total phenolic content (TFC) can be determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, and antioxidant activity can be assessed via DPPH and ABTS assays [8].

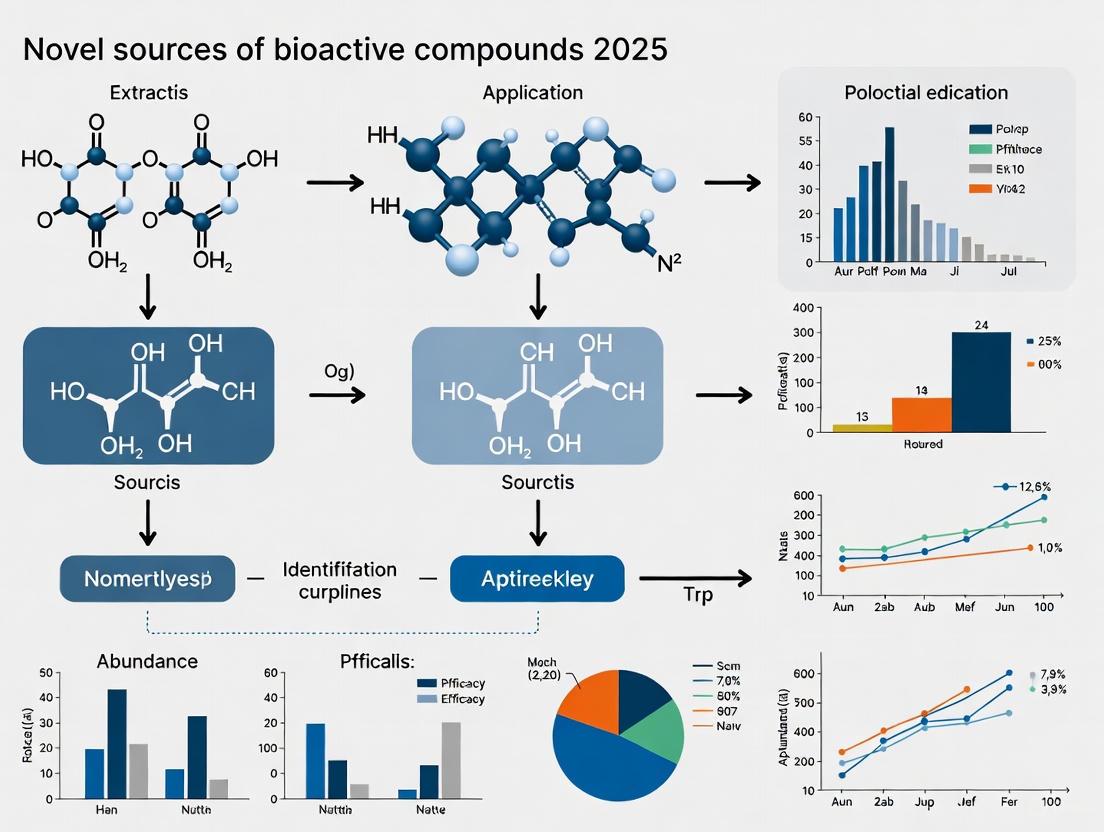

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key stages of this valorization pipeline, from raw by-product to pharmaceutical application.

Mechanisms of Action: From Bioactive to Pharmaceutical

Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which AFW-derived compounds exert their effects is crucial for drug development. The following diagram and text detail a key anti-inflammatory pathway.

Diagram 2: Anti-inflammatory Signaling Pathway of AFW-Derived Polyphenols.

As illustrated, polyphenols such as oleocanthal from olive pomace exhibit a multi-target mechanism. They directly inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, similar to the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen [4]. Concurrently, they modulate key signaling pathways like NF-κB, a master regulator of inflammation, leading to the downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 [8] [4]. This dual action underscores their potential as natural therapeutic agents or leads for synthetic derivatives in treating chronic inflammatory diseases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials essential for conducting research on bioactive compound recovery from AFW.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AFW Valorization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green, biodegradable solvents for extraction [1]. | Tunable properties; can be customized for specific compound classes like polyphenols [1]. |

| Macroporous Absorbing Resins | Purification and concentration of target compounds from crude extracts [6]. | Used for post-extraction purification of phenolic compounds from olive pomace [6]. |

| Maltodextrin / Whey Protein | Carrier agents for encapsulation via spray-drying [7]. | Protect bioactive compounds from degradation, enhance stability, and mask undesirable flavors [7]. |

| Specific Enzymes (e.g., Pectinases, Cellulases) | Enzyme-assisted extraction to break down plant cell walls [1] [6]. | Enables the release of bound phytochemicals; often used in combination with other techniques like UAE [6]. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., Gallic acid, Quercetin) | Calibration for quantification using HPLC, UPLC-MS [8]. | Essential for accurate identification and measurement of specific bioactive compounds in complex extracts [8]. |

Agri-food by-products are unequivocally a formidable and sustainable reservoir of pharmaceutical wealth. The convergence of advanced extraction technologies, a deepening understanding of their multi-faceted mechanisms of action, and the development of sophisticated research tools positions this field for significant growth. Future research must focus on overcoming scalability challenges, conducting rigorous in vivo and clinical studies to validate health claims, and navigating regulatory pathways for these complex natural products [1] [5]. By integrating these waste streams into the pharmaceutical value chain, the scientific community can drive innovation in drug discovery while championing environmental sustainability and a circular economy, truly embodying the principle of "from waste to wealth."

Marine ecosystems, encompassing both seaweeds (macroalgae) and marine microorganisms, represent a frontier in the discovery of novel bioactive compounds. Driven by the need to adapt to extreme and competitive environments, these organisms produce a vast array of unique secondary metabolites with complex structures and potent biological activities. Research in 2025 continues to underscore their immense, yet underexploited, potential for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic applications. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of the dominant metabolite classes, their quantified bioactivities, the experimental protocols essential for their study, and their mechanisms of action, framing this field within the broader context of discovering novel sources of bioactive compounds.

Quantitative Profiling of Key Metabolite Classes

The following tables summarize the major bioactive compounds from marine sources, their yields, and their measured biological activities as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Bioactive Metabolites from Marine Seaweeds (2025 Data)

| Metabolite Class | Example Species | Reported Yield/Content | Key Bioactivities (with Quantified Data) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phlorotannins | Durvillaea potatorum | 0.255 PGE mg/g at 12h fermentation [9] | Potent antioxidant (e.g., Radical scavenging: 1.15 mg TE/g DPPH in Sargassum fallax) [9] |

| Sulfated Polysaccharides | Rugulopteryx okamurae | Not specified (Structurally diverse) [10] | Immunomodulatory, antiviral, anticancer activities [10] [11] |

| Diterpenoids | Rugulopteryx okamurae | Not specified (Notably promising) [10] | Low-micromolar potency; Induction of mitochondrial apoptosis [10] |

| Total Phenolics | Durvillaea potatorum | 3.14 mg GAE/g at 8h fermentation [9] | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [9] |

Table 2: Bioactive Metabolites from Marine Microorganisms (2025 Data)

| Metabolite Class | Example Source | Number of New Compounds (Recent) | Key Bioactivities (with Quantified Data) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Marine Aspergillus spp. | 106 compounds (31.2% of 340 new NPs) [12] | Hepatoprotective (increased cell viability at 5.0-10.0 μM) [12]; Cytotoxic (IC₅₀ 25.8 μM) [12] |

| Polyketides | Marine Aspergillus spp. | 100 compounds (29.4% of 340 new NPs) [12] | Anti-inflammatory (reduced NO production in LPS-induced BV2 cells) [12] |

| Peptides | Marine Cyanobacteria | Not specified (Diverse structures) [13] | Protease inhibition (e.g., Grassystatins, Lyngbyastatins) [13]; Cytotoxic (e.g., Apratoxins, Dolastatin 10) [13] |

| Terpenoids | Talaromyces sp. (Marine Fungus) | New Trinor-sesterterpenoid [14] | Hepatoprotective (vs. hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury) [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Metabolite Discovery and Validation

The journey from marine biomass to a characterized bioactive compound involves a series of critical, interconnected experimental steps.

Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation Workflow

This is a standard methodology for isolating active compounds from a complex biological extract [13].

- Sample Collection and Identification: Marine organisms (seaweed or host for symbionts) are collected from their environment. Accurate taxonomic identification by a marine biologist is essential.

- Extraction: Biomass is typically lyophilized and ground into a powder. Conventional extraction uses solvents like methanol, ethanol, or ethyl acetate in a Solid-Liquid Extraction (SLE) process. Green Extraction Technologies are increasingly employed for higher yields and sustainability:

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Uses ultrasonic waves to disrupt cell walls, enhancing solvent penetration [15].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Utilizes microwave energy to rapidly heat the solvent and sample, reducing extraction time and solvent volume [15].

- Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE): Uses specific enzymes to break down cell walls and liberate bound compounds under mild conditions [15].

- Bioassay Screening: The crude extract is screened for a desired biological activity (e.g., cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory).

- Fractionation: The active crude extract is subjected to chromatographic separation (e.g., vacuum liquid chromatography, VLC) to generate fractions. These fractions are then re-screened in the bioassay.

- Purification and Structure Elucidation: The active fraction(s) undergo repeated chromatography (e.g., HPLC, MPLC) to isolate pure compounds. The structure of the active compound(s) is determined using spectroscopic techniques, predominantly Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) [13].

- Mechanistic Studies: The pure compound is investigated to understand its molecular mechanism of action, often using techniques like transcriptome sequencing and RT-qPCR to identify affected pathways [14].

In Vitro Colonic Fermentation Protocol for Bioavailability Studies

For seaweed phenolics, which often have low bioavailability, this protocol assesses their interaction with gut microbiota [9].

- Objective: To simulate the colonic fermentation of seaweed phenolics and evaluate their impact on gut microbiota composition and metabolic output.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Seaweed biomass is subjected to a simulated gastric and small intestinal digestion.

- Inoculation: The digested sample is introduced into a bioreactor containing a fecal slurry from a human donor (or a pig model, which is physiologically comparable) to provide a complex gut microbiota.

- Fermentation: The fermentation is carried out under anaerobic conditions at 37°C for up to 48 hours.

- Sampling: Aliquots are taken at specific time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 48 h).

- Analysis:

- Microbial Profiling: 16S rRNA sequencing of samples to analyze changes in microbial community structure (alpha and beta diversity) [9].

- SCFA Analysis: Measurement of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (e.g., acetic, butyric acid) via GC-MS.

- Phenolic & Antioxidant Metrics: Folin-Ciocalteu assay for total phenolics, DPPH/FRAP/ABTS assays for antioxidant capacity [9].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Bioactive marine compounds exert their effects by targeting specific cellular pathways. Two key mechanisms highlighted in recent research are detailed below.

NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Inhibition by Phlorotannins

Phlorotannins from brown algae like Rugulopteryx okamurae demonstrate potent anti-inflammatory effects by modulating pro-inflammatory signaling pathways [10].

Mitochondrial Apoptosis Induction by Diterpenoids

Diterpenoids from marine sources, such as those found in Rugulopteryx okamurae, can trigger programmed cell death in cancer cells by targeting the intrinsic apoptotic pathway [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table outlines key reagents and materials required for the experimental protocols described in this whitepaper.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Marine Metabolite Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Free radical used to assess antioxidant activity via radical scavenging assays [9]. | Quantifying antioxidant capacity of seaweed phenolic extracts. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Chemical reagent used to determine total phenolic content in samples [9]. | Measuring total phenolics in crude algal extracts during fractionation. |

| Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) | Potent inflammatory stimulus used to induce inflammation in cell models [12]. | Activating NF-κB/MAPK pathways in BV2 microglial or macrophage cells for anti-inflammatory testing. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Kits | For profiling and quantifying microbial community composition in complex samples [9]. | Analyzing gut microbiota changes during in vitro colonic fermentation of seaweed samples. |

| Chromatography Media | Stationary phases for separation (e.g., C18 silica, Sephadex LH-20). | Purifying and fractionating complex crude extracts from marine organisms. |

The global challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which accounts for millions of fatalities annually and is projected to cause 10 million deaths per year by 2050, has accelerated the search for novel bioactive compounds from alternative sources [16] [17]. Concurrently, the overreliance on a limited number of staple crops—with just six crops (rice, wheat, maize, potato, soybean, and sugarcane) providing over 75% of dietary plant energy—has created significant vulnerabilities in food systems and limited the diversity of phytochemicals available for discovery [18]. Within this context, underutilized medicinal plants represent a promising frontier for bioactive compound discovery, combining ecological resilience with rich phytochemical diversity that remains largely unexplored by modern science [19] [18].

These plant species, often labeled as neglected, orphan, or promising crops, are characterized by their historical use in traditional medicine systems, adaptation to specific ecological niches, and resistance to environmental stresses [18] [20]. Despite the identification of over 30,000 edible plants worldwide, only 150 are commercially cultivated on a significant scale, meaning thousands of species with potential pharmaceutical value remain underinvestigated [21] [18]. The systematic study of these resources represents a crucial strategy for addressing dual challenges in healthcare and sustainable agriculture, potentially yielding novel therapeutic agents while promoting biodiversity conservation [19] [22].

Promising Underutilized Plant Species and Their Bioactive Compounds

Representative Species with Pharmacological Potential

Recent research has identified several underutilized plant genera with significant potential for bioactive discovery, each possessing unique phytochemical profiles and demonstrated pharmacological activities.

Table 1: Promising Underutilized Plant Genera and Their Key Bioactives

| Plant Genus/Species | Family | Traditional Uses | Key Bioactive Compounds | Demonstrated Pharmacological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amelanchier Medik. (Serviceberry) | Rosaceae | Treating digestive ailments, fevers, colds, inflammation [23] [24] | Phenolic compounds, flavonoids (proanthocyanidins, anthocyanins, flavonols), triterpenes, carotenoids [23] [24] | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antidiabetic, antibacterial, antiviral [23] [24] |

| Tetrastigma leucostaphylum | Vitaceae | Treatment of headaches, fever, menstrual disorders, rheumatic pain [21] | Phenolics (7.12 mg GAE/g DW), flavonoids (6.78 mg QE/g DW), alkaloids (0.78 mg BE/g DW) [21] | Significant antioxidant activity (DPPH: 17.13 mg AAE/g DW; FRAP: 7.56 mg AAE/g DW) [21] |

| Selected Asteraceae Species (Balkan Peninsula) | Asteraceae | Treatment of wounds, bleeding, headaches, pain, digestive issues [25] | Phenolic acids, flavonoids, sesquiterpene lactones, tannins [25] | Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, hepatoprotective effects [25] |

| Ageratum conyzoides L. | Asteraceae | Traditional medical practices across South and Southeast Asia [19] | Alkaloids, terpenoids, stilbenoids, polyphenolic compounds [19] | Wound healing, skin whitening, respiratory aid, anticancer properties [19] |

| Artocarpus gomezianus | Moraceae | Traditional medical practices across South and Southeast Asia [19] | Alkaloids, terpenoids, stilbenoids, polyphenolic compounds [19] | Wound healing, skin whitening, respiratory aid, anticancer properties [19] |

Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis of Selected Species

Advanced phytochemical profiling of underutilized plants provides crucial data for assessing their potential for drug discovery and functional food applications.

Table 2: Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis of Selected Underutilized Plants

| Plant Species | Plant Part | Total Phenolics (mg GAE/g DW) | Total Flavonoids (mg CE/g DW) | Flavonols (mg QE/g DW) | Antioxidant Activity (DPPH, mg AAE/g DW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solidago virgaurea | Herb | 56.52 ± 2.72 | 45.18 ± 2.15 | 15.45 ± 0.89 | High [25] |

| Tanacetum vulgare | Herb | 48.75 ± 2.31 | 51.85 ± 2.98 | 12.85 ± 0.74 | High [25] |

| Tussilago farfara | Leaves | 44.35 ± 2.08 | 42.75 ± 2.24 | 11.95 ± 0.68 | High [25] |

| Cota tinctoria | Herb | 42.85 ± 2.15 | 40.15 ± 2.11 | 10.75 ± 0.62 | High [25] |

| Inula ensifolia | Herb | 41.95 ± 2.01 | 38.95 ± 1.98 | 9.85 ± 0.55 | High [25] |

| Helianthus tuberosus | Root | 2.45 ± 0.11 | 1.83 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | Low [25] |

The nutritional profiling of Tetrastigma leucostaphylum further demonstrates the nutraceutical potential of underutilized species, revealing substantial amounts of essential minerals including calcium (42.53 mg/g DW), nitrogen (10.03 mg/g DW), magnesium (9.03 mg/g DW), and phosphorus (0.05 mg/g DW), alongside a favorable macronutrient profile with low fat content (0.096%) and moderate protein (1.20%) and carbohydrate (12.50%) levels [21].

Experimental Protocols for Bioactive Compound Investigation

Standardized Phytochemical Extraction and Analysis

Extraction Methodology: The sequential solvent extraction method provides a systematic approach for recovering diverse phytochemical compounds based on polarity [21]. The protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Plant material is dried at 40±2°C until constant weight is achieved, then mechanically ground to a fine powder [21].

- Sequential Extraction: Using a Soxhlet apparatus, 100 ml of each solvent is applied in order of increasing polarity: petroleum ether, acetone, methanol, and water. Each extraction continues for 8 hours, with the residue dried and weighed between solvent changes [21].

- Extract Concentration: Organic solvents are removed using a rotary evaporator (e.g., Buchi Rotavapor R-100), while aqueous extracts are dried in an oven at 40±2°C [21].

- Storage: Final extracts are stored in sterile glass vials at -20°C until analysis [21].

Phytochemical Quantification assays:

- Total Phenolic Content: Determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents per gram dry weight (mg GAE/g DW) [21] [25].

- Total Flavavonoid Content: Measured via aluminum chloride colorimetric assay, expressed as mg catechin equivalents per gram dry weight (mg CE/g DW) [25].

- Total Alkaloid Content: Assessed using bromocresol green method, expressed as mg brucine equivalents per gram dry weight (mg BE/g DW) [21].

- Antioxidant Activity: Evaluated through multiple assays including DPPH radical scavenging, FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power), and ABTS, expressed as mg ascorbic acid equivalents per gram dry weight (mg AAE/g DW) [21] [25].

Bioactivity Screening Protocols

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: With the rise of multidrug-resistant microorganisms, standardized antimicrobial screening of plant extracts is essential [16] [17]. The recommended protocol includes:

- Test Microorganisms: Selection of priority pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Helicobacter pylori, Escherichia coli, and Bacillus anthracis [16].

- Extract Preparation: Serial dilutions of plant extracts in appropriate solvents.

- Assay Methods: Both disc diffusion and broth microdilution methods to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs).

- Control Standards: Inclusion of appropriate positive (standard antibiotics) and negative (solvent) controls.

- Biofilm Disruption Assays: For device-associated infections, specific testing of biofilm disruption potential using crystal violet or resazurin-based assays [16].

Anti-inflammatory Activity Evaluation: Given the traditional use of many underutilized plants for inflammatory conditions, systematic evaluation of their anti-inflammatory potential is warranted:

- In Vitro Models: COX-1 and COX-2 enzyme inhibition assays, nitric oxide production inhibition in macrophage cell lines, and cytokine expression profiling.

- In Vivo Models: Carrageenan-induced paw edema, cotton pellet granuloma, and xylene-induced ear edema models.

- Molecular Mechanisms: Investigation of NF-κB, MAPK, and Nrf-2 signaling pathways using Western blot, ELISA, and reporter gene assays.

Proposed Mechanisms of Action and Signaling Pathways

The bioactive compounds isolated from underutilized plants demonstrate multi-target mechanisms against various pathological conditions. The antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities of these phytochemicals involve complex interactions with cellular signaling pathways.

Diagram 1: Proposed antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of underutilized plant bioactives. The multi-target action includes bacterial membrane disruption, efflux pump inhibition, NF-κB pathway suppression, and COX-2 enzyme inhibition.

The complexity of these mechanisms highlights the advantage of plant extracts over single-target pharmaceuticals, potentially reducing the development of resistance and providing synergistic therapeutic effects [16] [17].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of underutilized plants requires specific reagents, equipment, and methodologies standardized across phytochemical and bioactivity studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Bioactive Compound Investigation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Equipment | Application/Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Petroleum ether, acetone, methanol, ethanol, water | Sequential extraction of compounds based on polarity | HPLC grade for analysis; ethanol preferred for safer commercialization [21] [25] |

| Phytochemical Assay Reagents | Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, aluminum chloride, bromocresol green, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Quantification of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, alkaloids, and antioxidant capacity | Fresh preparation required; standard curve correlation >0.99 recommended [21] [25] |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC-MS, atomic absorption spectrophotometer, rotary evaporator, UV-Vis spectrophotometer | Compound separation, identification, and quantification; element analysis; solvent removal | LC-MS enables compound identification; AAS for mineral content [21] [25] |

| Antimicrobial Testing Materials | Mueller-Hinton agar, microdilution plates, standard antibiotic controls, resazurin dye | Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and antimicrobial activity | CLSI guidelines recommended; include quality control strains [16] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | DMEM/RPMI media, fetal bovine serum, MTT reagent, specific cytokines/antibodies for signaling studies | In vitro assessment of anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and toxicological properties | Include positive and negative controls; standardized incubation conditions [23] |

The experimental workflow for comprehensive investigation of underutilized plants can be visualized as a systematic process from raw material to bioactive compound identification:

Diagram 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for investigating underutilized plants, from collection to bioactive compound identification and application potential.

Research Gaps and Future Perspectives

Despite the promising potential of underutilized plants, significant research gaps remain. Clinical evidence for most species is lacking, with studies predominantly limited to in vitro models and preliminary phytochemical characterization [19] [23]. The toxicological profiles of many underutilized plants remain inadequately documented, presenting a barrier to drug development [23] [20]. Standardization of extracts represents another challenge, with variations in extraction methodologies complicating comparison between studies [19] [25]. Furthermore, sustainable sourcing strategies must be developed to prevent overharvesting and ecological damage when promising species are identified [22] [18].

Future research should prioritize interdisciplinary approaches that combine methods from evolutionary ecology, molecular biology, biochemistry, and ethnopharmacology [22]. This integrated strategy should leverage traditional Indigenous knowledge while applying modern technological advances in metabolomics, genomics, and synthetic biology [22]. The concept of medicinal plants as symbiotic partners rather than mere chemical factories represents a paradigm shift that may accelerate discovery while respecting traditional knowledge systems [22].

Investment in breeding programs for underutilized species could enhance yields of valuable bioactive compounds while maintaining the environmental resilience that makes these species valuable [18] [20]. Finally, development of inclusive value chains that involve local communities can ensure equitable benefit sharing and promote conservation of these genetic resources [20].

Underutilized plant cultivars represent a largely untapped reservoir of diverse bioactive compounds with significant potential for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmeceutical applications. Species such as Amelanchier, Tetrastigma leucostaphylum, and various Asteraceae family members contain substantial quantities of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other secondary metabolites with demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. The multi-target mechanisms of action of these phytochemicals, particularly against multidrug-resistant microorganisms and inflammatory pathways, offer distinct advantages over single-target synthetic pharmaceuticals.

Systematic investigation through standardized extraction protocols, advanced analytical techniques, and robust bioactivity screening represents a promising path for biodiscovery. Future research efforts should address critical gaps in clinical evidence, toxicological profiling, and sustainable sourcing while embracing interdisciplinary approaches that integrate traditional knowledge with modern scientific methodologies. The strategic development of underutilized plants not only offers opportunities for novel drug discovery but also supports biodiversity conservation, climate-resilient agriculture, and sustainable economic development within local communities.

Insects and fungi represent two of the most promising and sustainable frontiers for discovering novel bioactive compounds in 2025. Driven by the need for alternative protein sources and the untapped potential of fungal biochemistry, research into these organisms is accelerating. Edible insects are now recognized as functional foods, providing not only essential nutrients but also bioactive peptides, chitin, and phenolic compounds with demonstrated antihypertensive, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties [26] [27] [28]. Concurrently, medicinal and marine endophytic fungi produce a vast arsenal of structurally unique secondary metabolites—including terpenoids, alkaloids, and polysaccharides—with potent anticancer, antimicrobial, and neuroprotective activities [29] [30]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the bioactive compounds derived from these sources, detailing their mechanisms of action, standardized extraction methodologies, and the essential reagents required for advancing this critical field of research. The integration of these novel sources into drug development pipelines and functional food products holds significant potential for addressing global health challenges and building more sustainable food and pharmaceutical systems.

Bioactive Compounds from Edible Insects

Key Insect Species and Their Bioactive Profiles

Edible insects are a rich source of macronutrients and a viable source of a wide range of bioactive compounds. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has approved several insect species for human consumption, including Acheta domesticus (house cricket), Alphitobius diaperinus (lesser mealworm), Locusta migratoria (migratory locust), and Tenebrio molitor (yellow mealworm) [27]. These insects are characterized by their balanced nutritional profiles and content of functional compounds such as bioactive peptides, chitin, chitosan, and phenolic compounds.

Table 1: Key Bioactive Compounds from Approved Edible Insect Species

| Insect Species | Key Bioactive Compounds | Documented Bioactivities | Mechanisms of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tenebrio molitor (Yellow Mealworm) | Bioactive peptides, Chitin/Chitosan [31] [27] | Antihypertensive, Antioxidant, Neuroprotective [28] | ACE inhibition; DPPH radical scavenging [27] [28] |

| Acheta domesticus (House Cricket) | Bioactive peptides, Phenolic compounds [31] | Antioxidant, Antimicrobial [31] | Radical scavenging activity [31] |

| Locusta migratoria (Migratory Locust) | Peptides, Chitin [27] | ACE Inhibitory, Anti-inflammatory [27] | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibition [27] |

| Gryllus bimaculatus (Two-Spotted Cricket) | Glycosaminoglycan [28] | Anti-inflammatory, Anti-diabetic, Cardiovascular protection [28] | Suppression of inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., C-reactive protein); reduction of blood glucose and LDL [28] |

| Blaps japanensis | Blapsols A-D [28] | Antioxidant [28] | DPPH and hydroxyl radical scavenging activities [28] |

| Bombyx mori (Silkworm) | Immunomodulatory hexapeptide [28] | Immunomodulatory [28] | Modulation of immune-related factors [28] |

Experimental Protocol: Extraction and Identification of Insect Bioactive Peptides

The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for obtaining bioactive peptides from insect biomass, adapted from recent research [31] [28].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Whole insects are first defatted to reduce lipid content. This is typically achieved using an organic solvent like hexane or through supercritical CO₂ extraction, which is considered more environmentally friendly [31].

- 2. Protein Extraction: The defatted material is subjected to protein extraction, often using aqueous or mild alkaline solutions.

- 3. Hydrolysis: The extracted proteins are hydrolyzed using one of two primary methods:

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: This is the most common method. Proteolytic enzymes such as alcalase, pepsin, or papain are used under controlled conditions of pH and temperature (e.g., 50-60°C, pH 7-8 for alcalase) for a specified period (typically 1-4 hours) [28]. The reaction is terminated by heat inactivation.

- Ultramicro-pretreatment: Some protocols involve a physical pretreatment step (e.g., ultra-sonication or high-pressure processing) to disrupt protein structures before enzymatic hydrolysis, which can increase peptide yield and bioactivity [28].

- 4. Separation and Concentration: The hydrolysate is centrifuged to remove insoluble residues. The supernatant containing the peptide mixture is then concentrated, often using ultrafiltration membranes with specific molecular weight cut-offs (e.g., 3 kDa or 10 kDa) to fractionate the peptides [31].

- 5. Purification and Identification:

- Purification: The concentrated peptide fractions are purified using chromatographic techniques. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is the standard, using reverse-phase (C18) columns. Fractions are collected and screened for target bioactivities (e.g., ACE inhibitory activity) [28].

- Identification: Active fractions are analyzed by Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to determine the amino acid sequences of the bioactive peptides.

Bioactive Compounds from Fungi

Fungi, particularly marine endophytes and medicinal mushrooms, are prolific producers of secondary metabolites with profound biological activities. Marine endophytic fungi, which live symbiotically within marine hosts like sponges, corals, and mangroves, are a novel source of unique chemical scaffolds due to the extreme conditions of their habitat [30]. Medicinal fungi like Inonotus obliquus (Chaga) and Auricularia auricula have a long history of use and their bioactivities are now being validated scientifically [29].

Table 2: Key Bioactive Compounds from Fungal Sources

| Fungal Source / Species | Key Bioactive Compound Classes | Documented Bioactivities | Mechanisms of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Endophytic Fungi (e.g., from sponges, corals) | Alkaloids, Terpenoids, Peptides, Polyketides [30] | Anticancer, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant [30] | Induction of apoptosis; disruption of microbial cell membranes; ROS quenching [30] |

| Inonotus obliquus (Chaga) | Polysaccharides [29] | Anti-inflammatory, Immunomodulatory [29] | Network pharmacology studies indicate modulation of signaling pathways in autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis [29] |

| Auricularia auricula | Exopolysaccharides [29] | Immunomodulatory, Microbiota remodeling [29] | Dectin-1 mediated immunomodulation; mitigation of DSS-induced colitis [29] |

| Cordyceps militaris | Cordycepin [28] | Anti-cancer, Immunomodulatory [28] | Tumor suppression, apoptosis induction [28] |

| Marine Fungus Eutypella sp. | Novel Sesquiterpenes, Diterpenoids [29] | Immunosuppressive [29] | Potent inhibition of immune cell activation [29] |

Experimental Protocol: Isolation and Characterization of Fungal Metabolites

The workflow for discovering bioactive compounds from fungi, especially endophytic strains, involves cultivation, extraction, and sophisticated chemical analysis [29] [30].

- 1. Fungal Cultivation and Fermentation Optimization:

- Strain Isolation: Endophytic fungi are isolated from host tissue (e.g., marine sponge) using surface sterilization techniques and cultured on appropriate media like Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) [30].

- Scale-Up: Isolated strains are transferred to liquid culture for larger-scale metabolite production. Fermentation conditions (temperature, pH, aeration, nutrient composition) are critically optimized. The addition of specific precursors or inducers (e.g., Mn(II) or Co(II) ions) can dramatically alter the metabolite profile and enhance yield [29] [30].

- 2. Metabolite Extraction: After the fermentation period, the broth is filtered to separate the mycelial biomass from the culture filtrate.

- Mycelial Extraction: The biomass is dried and extracted using solvents like methanol, ethyl acetate, or a mixture, often assisted by ultrasound or microwave to improve efficiency [32] [30].

- Broth Extraction: The culture filtrate is passed through a resin column (e.g., XAD-16) to adsorb organic compounds, which are then eluted with an organic solvent like methanol [30].

- 3. Bioassay-Guided Fractionation: The crude extract is subjected to an initial bioassay (e.g., cytotoxicity against a cancer cell line or antimicrobial assay). The active crude extract is then fractionated using techniques like Vacuum Liquid Chromatography (VLC) or solid-phase extraction. Fractions are again tested for activity.

- 4. Purification and Structure Elucidation:

- Purification: The active fraction is subjected to repetitive chromatographic separations, primarily using semi-preparative or analytical HPLC with various detectors (UV, DAD, ELSD). This process is repeated until pure compounds are obtained.

- Structure Elucidation: The structure of purified metabolites is determined using a combination of spectroscopic techniques, including Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) (¹H, ¹³C, 2D-NMR) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) [29] [30]. Advanced approaches like network pharmacology can be integrated at this stage to predict potential molecular targets [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and instrumentation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioactive Compound Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Hydrolysis of insect proteins to generate bioactive peptides. | Alcalase (broad specificity), Pepsin (stomach digestion model), Papain [28]. |

| Chromatography Resins & Columns | Separation and purification of compounds from complex extracts. | HPLC Columns: C18 reverse-phase for peptides/small molecules; Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) for polysaccharides [31] [28]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | In vitro screening for bioactivity (e.g., anti-inflammatory, cytotoxicity). | Kits for measuring ACE inhibition, antioxidant activity (ORAC, DPPH), and cytokine (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) ELISAs for immunomodulation studies [27] [28]. |

| Culture Media for Fungi | Isolation and fermentation of fungal strains. | Potato Dextrose Agar/Broth (PDA/PDB), Malt Extract Agar (MEA). Often require addition of sea salts for marine fungi [30]. |

| Spectroscopy Solvents | Extraction and analysis of bioactive compounds. | Deuterated solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) for NMR analysis; MS-grade solvents for LC-MS [30]. |

| Inducers/Precursors | Elicitation of secondary metabolite production in fungal cultures. | Mn(II), Co(II) ions have been shown to alter anti-Candida metabolite profiles in Aspergillus sp. [29]. |

The systematic exploration of insects and fungi for bioactive compounds is a cornerstone of the search for novel sustainable resources in 2025. The convergence of entomology and mycology with advanced analytical chemistry and molecular biology is yielding a new generation of functional ingredients and drug leads. While challenges remain—including optimizing large-scale production, ensuring consistent quality and safety, and navigating regulatory pathways—the potential is immense. Future research will undoubtedly focus on harnessing biotechnology, such as metabolic engineering of fungal strains and optimized rearing of insects on agri-food by-products, to unlock the full potential of these remarkable organisms for human health and sustainable development.

The escalating demand for novel sources of bioactive compounds has positioned avocado (Persea americana) as a fruit of significant scientific and industrial interest. This whitepaper synthesizes the most current research (2020-2025) on the lipid and phenolic profiles of avocado, with emphasis on their demonstrated bioactivities and the advanced extraction technologies enabling their study. Beyond the well-documented nutritional value of the pulp, this review highlights the substantial potential of underutilized by-products—peel and seed—which are rich reservoirs of phenolics with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative properties. Supported by a growing body of preclinical and clinical evidence, avocado and its constituents present a compelling case for application in functional foods, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceutical development, aligning with the principles of the circular bioeconomy and sustainable resource valorization.

Persea americana, a fruit native to Mesoamerica, has transcended its role as a food item to become a focal point of intense scientific investigation due to its unique composition of health-promoting bioactive compounds [33]. The global expansion of avocado production, projected to reach 12 million tons by 2030, generates substantial volumes of processing by-products (peel and seed), representing up to 30% of the fruit's total weight [34] [35]. This context provides a compelling rationale for the valorization of avocado within a broader thesis on novel sources of bioactive compounds, emphasizing sustainable utilization and waste reduction.

The fruit's significance stems from its distinctive combination of a lipid profile rich in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and a complex array of phenolic compounds, which are consistently associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, glycemic regulatory, and cardioprotective effects [33]. A nationally representative Australian survey revealed that avocado consumers had significantly lower body mass index, waist circumference, and systolic blood pressure compared to non-consumers [33]. This whitepaper provides a critical synthesis of the chemical composition, bioactivity, and technological applications of avocado, with particular emphasis on recent advances in green extraction, nanostructured delivery systems, and precision nutrition strategies that underscore its relevance to contemporary research in bioactive compound discovery.

Comprehensive Chemical Profiling of Avocado Bioactives

Lipid Profile and Associated Health Benefits

Avocado pulp is among the richest plant-based sources of lipids, characterized by a profile considered highly beneficial to human health. The lipid content ranges from 15% to 30% of fresh pulp mass, varying by cultivar and ripeness [33]. The Hass variety, the most widely studied commercial cultivar, contains approximately 19.7% total lipids by fresh weight [33].

Table 1: Fatty Acid Composition and Bioactive Lipids in Avocado Pulk (Hass Variety)

| Component | Concentration/Percentage | Health Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (C18:1) | 67-71% of total fatty acids [33] | Cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory, hypocholesterolemic [33] |

| Total Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) | >70% of total lipids [35] | Improves lipid profiles, supports cardiovascular health [33] [35] |

| Phytosterols (e.g., β-sitosterol) | 35.6 mg/100 g dw (pulp); up to 339.6 mg/100 g in oil [33] [34] | Cholesterol-lowering, anti-inflammatory [33] |

| α-Tocopherol (Vitamin E) | Up to 24.5 mg/100 g [33] | Protects cellular membranes from lipid peroxidation [33] |

Clinical evidence substantiates the therapeutic potential of avocado lipids. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that daily consumption of one whole avocado for 12 weeks significantly reduced total cholesterol and improved cardiometabolic profiles in individuals with insulin resistance [33]. A systematic review of 45 studies reported consistent reductions in low-density lipoprotein (LDL), particularly small, dense, and oxidized LDL particles, alongside increases in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [33].

Phenolic Diversity and Antioxidant Potency

Phenolic compounds are abundantly present throughout the avocado fruit, with concentrations notably higher in the peel and seed compared to the pulp [36] [37]. These compounds are pivotal in countering oxidative stress and modulating inflammatory pathways.

Table 2: Phenolic Composition Across Different Avocado Parts (Representative Values)

| Avocado Part | Total Phenolic Content (TPC) | Key Identified Phenolics | Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peel | 77.85 mg GAE/g (Hass, ripe) [36]; Range: 65-250 mg GAE/g DW [38] | Chlorogenic acid, gallic acid, ferulic acid, rutin, quercetin derivatives, kaempferol glycosides [36] [38] | 3.44 mg QE/g (Hass, unripe) [36] |

| Seed | 45-180 mg GAE/g DW [38] | Catechin, epicatechin, procyanidins, flavonoid glycosides [39] [34] | Varies by cultivar and extraction |

| Pulp | Lower than peel and seed [37] | Gallic acid, catechin, quercetin, ferulic acid, chlorogenic acid, epicatechin [33] | Varies by cultivar and extraction |

Advanced analytical techniques have identified up to 64 distinct phenolics in the pulp alone, including chlorogenic acid and epicatechin [33]. A comprehensive screening of avocado by-products identified 348 polyphenols in the peel, with 134 compounds fully characterized, including 36 phenolic acids, 70 flavonoids, 11 lignans, and 2 stilbenes [36]. The antioxidant capacity of these compounds is significant. Ripe Hass peel demonstrated the highest values in multiple antioxidant assays: DPPH (71.03 mg AAE/g), FRAP (3.05 mg AAE/g), and ABTS (75.77 mg AAE/g) [36]. Correlation analyses have confirmed that total phenolic content (TPC) and total tannin content (TTC) are significantly correlated with the antioxidant capacity of avocado extracts [36].

Experimental Protocols for Bioactive Compound Analysis

Protocol for Extraction of Polyphenols from Avocado By-Products

This protocol, adapted from current methodologies, details the steps for obtaining phenolic-rich extracts from avocado peel, seed coat, and seed [36] [37].

- Sample Preparation: Fresh avocado by-products (peel, seed) are separated, cleaned, and cut into small pieces. The material is then freeze-dried and homogenized into a fine powder using a laboratory blender or grinder.

- Extraction Solvent Preparation: Prepare a solution of 80% (v/v) ethanol in deionized water. This solvent has demonstrated high efficiency for polyphenol extraction due to its ability to degrade polysaccharides in plant cell walls, facilitating the release of phenolic compounds [40].

- Maceration Extraction:

- Combine 5 g of the dried powder with 20 mL of the 80% ethanol solution in a sealed container.

- Homogenize the mixture using an Ultra-Turrax T25 Homogenizer or similar for 30 seconds.

- Incubate the mixture at 40°C in an orbital shaker set to 120 rpm for 12-20 hours [37].

- Separation and Concentration:

- Centrifuge the mixture at 5000 rpm for 10-15 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect the supernatant and filter it through a 0.45 μm syringe filter.

- Remove the ethanol from the filtrate using a rotary evaporator under vacuum at 40°C.

- Freeze-dry the remaining aqueous fraction to obtain a dry, powdered extract ready for analysis [37].

Protocol for Quantification of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The Folin-Ciocalteu method is the standard spectrophotometric assay for determining TPC [36] [37] [40].

- Reagent Preparation:

- Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent: Dilute the commercial reagent with deionized water in a 1:3 ratio.

- Sodium Carbonate Solution: Prepare a 10% (w/w) aqueous solution.

- Gallic Acid Standard: Prepare a series of gallic acid standards in the range of 0-200 μg/mL for calibration.

- Reaction Procedure:

- In a 96-well plate, add 25 μL of the avocado extract or standard, 25 μL of the diluted Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and 200 μL of deionized water.

- Incubate the plate for 5 minutes in the dark at 25°C.

- Add 25 μL of the sodium carbonate solution to each well and incubate for 60 minutes at 25°C in the dark.

- Measurement and Calculation:

- Measure the absorbance of the reaction mixture at 764 nm using a microplate reader.

- Generate a standard curve from the gallic acid standards (R² > 0.995).

- Express the results as milligrams of Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) per gram of sample (mg GAE/g) [36].

Mechanisms of Bioactivity: Signaling Pathways

Bioactive compounds in avocado exert their effects through multiple molecular pathways. The following diagram synthesizes key mechanisms derived from current research, illustrating how lipids and phenolics modulate physiological processes relevant to chronic diseases.

Diagram 1: Proposed Molecular Mechanisms of Avocado Bioactives. This diagram summarizes the primary mechanisms by which avocado lipids (green) and phenolics (red) exert their bioactivities. HAT/ET: Hydrogen Atom Transfer/Electron Transfer, key mechanisms for radical scavenging.

Advanced Extraction Technologies

The efficient recovery of bioactive compounds from avocado, particularly from complex matrices like peel and seed, relies on advanced extraction technologies that align with green chemistry principles.

Table 3: Green Extraction Technologies for Avocado Bioactives

| Technology | Mechanistic Principle | Key Advantages | Reported Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Uses high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles, disrupting cell walls and enhancing mass transfer [33]. | Reduced extraction time and solvent consumption, improved yield, scalability potential [33] [38]. | Effectively recovers chlorogenic and ferulic acids from peel when combined with NADES [38]. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Dielectric heating causes rapid internal heating of moisture, rupturing cells from within [33]. | Rapid energy transfer, high efficiency, selective heating [33]. | Demonstrated improved efficiency over conventional methods [33]. |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Mixtures of natural compounds (e.g., choline chloride with organic acids) forming a solvent with low toxicity and high biodegradability [33]. | Green, sustainable, tunable polarity for selective extraction, high biocompatibility [33] [38]. | Improved selectivity and efficiency for phenolics compared to traditional solvents [41] [38]. |

These technologies have demonstrated superior efficiency in recovering bioactives while reducing environmental impact. For instance, the combination of UAE and NADES has been shown to improve the selectivity and efficiency of isolating specific phenolic acids from avocado peel [38]. Furthermore, response surface methodology (RSM) has been successfully employed to optimize the extraction process of antioxidants from avocado seeds in ethanol-water systems, maximizing yield and activity [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying Avocado Bioactives

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Spectrophotometric quantification of total phenolic content (TPC) via redox reaction [36] [37]. | Determination of TPC in avocado peel, seed, and pulp extracts [36]. |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable free radical used to assess the free radical scavenging (antioxidant) capacity of extracts [36] [40]. | Avocado seed procyanidin showed potent activity (EC₅₀ = 3.6 µg/mL) [40]. |

| ABTS (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Cation radical used to measure antioxidant activity via electron transfer mechanism [36] [38]. | Antioxidant assay of avocado by-products; ripe Hass peel showed 75.77 mg AAE/g [36]. |

| Aluminium Chloride (AlCl₃) | Forms acid-stable complexes with the C-4 keto group and either the C-3 or C-5 hydroxyl group of flavonoids for quantification [36] [37]. | Colorimetric determination of total flavonoid content (TFC) in avocado extracts [36]. |

| LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS | High-resolution mass spectrometry for precise identification and characterization of individual phenolic compounds [36]. | Identification of 134 polyphenols in avocado peel and seed, including phenolic acids and flavonoids [36]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line used as a model of the intestinal barrier for absorption and permeability studies, and for assessing antiproliferative effects [37]. | In-silico and in-vitro studies of phenolic absorption and avocado extract-induced apoptosis [37]. |

Persea americana stands as a paradigm for the exploration of novel bioactives from plant sources. Its value extends beyond the nutrient-dense pulp to encompass the peel and seed, which are demonstrated rich sources of phenolic compounds with potent antioxidant and bio-regulatory capacities. The integration of green extraction technologies is pivotal for the sustainable and efficient valorization of these components, supporting circular economy principles.

Future research must focus on several critical areas to translate preclinical findings into practical applications. First, there is a need for standardized extraction and quantification protocols to ensure reproducibility and enable cross-study comparisons [38]. Second, while in vitro evidence is robust, more in vivo and clinical studies are essential to confirm physiological relevance, bioavailability, and long-term safety in diverse populations [39] [42] [38]. Third, research should explore the synergistic effects of the complex mixture of compounds in avocado extracts, which may underlie its multi-target therapeutic potential, particularly in managing non-communicable diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular disorders [39] [42]. Finally, overcoming the scalability challenges of advanced extraction technologies will be crucial for their industrial adoption. By addressing these gaps, avocado can firmly transition from a dietary staple to a cornerstone ingredient in the functional food, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical industries.

From Source to Synapse: Advanced Extraction and Functionalization Strategies

The increasing demand for natural bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic applications has driven the development of efficient and sustainable extraction technologies. Green extraction methods have gained prominence as sustainable alternatives to conventional solvent-intensive techniques, offering reduced environmental impact while maintaining high efficiency and selectivity [43]. Within the context of novel sources of bioactive compounds in 2025 research, three technologies stand out for their industrial relevance and technical maturity: ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) using CO₂ [44] [45].

These innovative techniques align with the principles of green chemistry by minimizing organic solvent consumption, reducing energy requirements, and preserving the bioactivity of sensitive compounds [46]. The global shift toward sustainable industrial practices has further accelerated their adoption across research and industrial settings, particularly for valorizing agricultural by-products and discovering novel bioactive compounds from underexplored sources [47]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of these three key technologies, focusing on their fundamental principles, optimization parameters, and applications within modern bioactive compound research.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Each green extraction technology operates on distinct physical principles that determine its application range and efficiency for specific bioactive compounds.

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) utilizes fluids above their critical temperature and pressure, where they exhibit unique properties combining liquid-like solvating power with gas-like diffusivity [43]. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is the most prevalent supercritical solvent due to its moderate critical point (31°C, 74 bar), non-toxicity, and GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status [43] [48]. The solvent power of supercritical CO₂ (SC-CO₂) can be precisely tuned by adjusting pressure and temperature parameters, enabling selective extraction of target compounds [46].

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) employs electromagnetic radiation to generate heat directly within plant matrices through two primary mechanisms: dipolar rotation and ionic conduction [44] [49]. This volumetric heating effect disrupts plant cells rapidly and efficiently, enhancing the release of intracellular compounds while significantly reducing extraction time and solvent consumption compared to conventional methods.

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) operates through acoustic cavitation, where the formation, growth, and collapse of microbubbles in a liquid medium generate extreme local temperatures and pressures along with shear forces that disrupt cell walls and enhance mass transfer [50] [49]. This mechanism facilitates the rapid release of bioactive compounds while operating at mild temperatures that preserve compound integrity.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following table summarizes the key operational characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each extraction technology:

Table 1: Comparative analysis of green extraction technologies

| Parameter | Supercritical CO₂ Extraction | Microwave-Assisted Extraction | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Tunable solvation power in supercritical state [43] | Volumetric heating via microwave radiation [44] | Cell disruption via acoustic cavitation [50] |

| Typical Temperature | 31-80°C [46] | 50-150°C [44] | 20-60°C [50] |

| Typical Pressure | 74-500 bar [43] [48] | Atmospheric to 50 bar [44] | Atmospheric pressure [50] |

| Extraction Time | 30-180 minutes [43] | 5-30 minutes [44] | 5-60 minutes [50] [49] |

| Solvent Consumption | Low to moderate (CO₂ recyclable) [46] | Low [44] | Low to moderate [50] |

| Selectivity | Highly tunable [43] [48] | Moderate [44] | Low to moderate [50] |

| Capital Cost | High [43] | Moderate [44] | Low to moderate [50] |

| Key Advantages | Solvent-free extracts, high selectivity, low thermal degradation [43] [46] | Rapid heating, reduced time/solvent, improved yield [44] | Simple operation, mild conditions, equipment accessibility [50] |

| Main Limitations | High initial investment, technical complexity [43] [46] | Limited penetration depth, scalability challenges [44] | Potential compound degradation with prolonged use [50] |

Supercritical CO₂ Extraction (SFE)

Technical Fundamentals and Optimization

Supercritical CO₂ extraction leverages the unique properties of carbon dioxide above its critical point (31.1°C, 73.8 bar). In this state, CO₂ exhibits gas-like diffusivity and liquid-like density, enabling superior penetration into plant matrices and tunable solvation power [43] [46]. The solvent strength of SC-CO₂ correlates directly with its density, which can be precisely controlled through temperature and pressure adjustments [46].

Key operational parameters significantly influence extraction efficiency and selectivity:

- Pressure (100-500 bar): Higher pressures increase CO₂ density, enhancing solvation power for heavier molecules like triglycerides and carotenoids [48] [46].

- Temperature (35-80°C): Affects both CO₂ density and solute vapor pressure, with optimal ranges dependent on target compounds [46].

- Co-solvents (1-15%): Modifiers like ethanol, methanol, or water dramatically improve extraction efficiency for medium-to-high polarity compounds (e.g., polyphenols, flavonoids) by increasing solvent polarity [43] [46].

- Flow rate (0.5-5 L/min): Influences contact time between CO₂ and plant matrix, affecting extraction kinetics and throughput [43].

- Particle size (0.1-0.5 mm): Smaller particles increase surface area but may cause channeling; optimal size balances mass transfer with flow dynamics [48].

Table 2: SFE applications for specific bioactive compounds

| Bioactive Class | Plant Sources | Optimal Conditions | Yield Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | Marigold, tomato, carrot | 40-60°C, 300-400 bar [43] | 20-40% vs. conventional [43] |

| Polyphenols | Grape seed, olive pomace | 50-70°C, 250-350 bar, 10% ethanol [43] | 15-30% vs. conventional [43] |

| Essential Oils | Lavender, peppermint | 40-50°C, 80-120 bar [43] | Higher selectivity for volatiles [43] |

| Cannabinoids | Cannabis sativa | 50-60°C, 250-300 bar [43] | Superior purity and recovery [43] |

Experimental Protocol for Antioxidant Extraction

Objective: Extract polyphenols and carotenoids from grape pomace using SFE with ethanol as co-solvent.

Materials and Equipment:

- Supercritical fluid extraction system with co-solvent capability

- Liquid CO₂ with dip tube

- Food-grade ethanol (95-99%)

- Grape pomace (dried, ground to 0.3-0.5 mm)

- Collection vials

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry grape pomace at 40°C for 24 hours, followed by grinding and sieving to 0.3-0.5 mm particle size.

- Extraction Vessel Loading: Pack the extraction vessel (typically 100-500 mL capacity) evenly with 50 g of prepared pomace mixed with 150 g of inert filler (e.g., glass beads) to prevent channeling.

- System Pressurization: Set extraction temperature to 60°C and slowly pressurize the system to 300 bar using CO₂.

- Co-solvent Introduction: Introduce ethanol at 10% (v/v) of total solvent flow rate using a high-pressure pump.

- Dynamic Extraction: Maintain conditions at 60°C and 300 bar with a CO₂ flow rate of 2 L/min for 120 minutes.

- Fraction Collection: Collect extracts in amber vials maintained at 15°C and 50 bar to ensure efficient compound recovery.

- Solvent Removal: Evaporate residual ethanol under nitrogen stream, followed by lyophilization to obtain dry extract.

- Analysis: Quantify total polyphenol content using Folin-Ciocalteu method and identify specific compounds via HPLC-DAD-MS [43].

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

Technical Fundamentals and Optimization

Microwave-assisted extraction utilizes electromagnetic radiation (300 MHz to 300 GHz) to generate heat directly within plant materials through two primary mechanisms: dipolar rotation (molecular friction from oscillating dipoles) and ionic conduction (migration of ions in solution) [44]. This internal heating mechanism rapidly elevates temperature and pressure within cells, causing rupture and enhancing release of intracellular compounds into the surrounding solvent.

Critical parameters for optimizing MAE processes include:

- Microwave Power (100-1000 W): Higher power increases heating rate but may cause degradation of thermolabile compounds [44].

- Extraction Time (1-30 minutes): MAE typically requires significantly less time than conventional methods due to rapid heating [44].

- Solvent Composition: Dielectric constant determines microwave absorption; ethanol-water mixtures (30-70% ethanol) are common for polyphenols [44] [49].

- Temperature (40-120°C): Controlled via temperature sensors to prevent degradation of target compounds [44].

- Solid-to-Liquid Ratio (1:5 to 1:30): Affects mass transfer efficiency and process economics [44].

Recent advances in MAE include integration with other technologies (e.g., ultrasound, enzymatic pretreatment) and the development of continuous flow systems for industrial-scale applications [44]. The technology has shown particular effectiveness for extracting thermostable compounds from hard plant matrices where conventional methods face diffusion limitations.

Experimental Protocol for Phenolic Compound Extraction

Objective: Extract phenolic compounds from olive leaves using optimized MAE conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Laboratory microwave extraction system with temperature control

- Ethanol-water mixtures (food grade)

- Olive leaves (dried, ground)

- Filtration apparatus

- Rotary evaporator

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry olive leaves at 40°C, grind to 0.5-1.0 mm particle size, and store in desiccator.

- Solvent Preparation: Prepare ethanol-water mixture (70:30 v/v) as extraction solvent.

- Extraction Setup: Combine 5 g of prepared olive leaves with 100 mL of solvent in microwave-safe vessel.

- Microwave Extraction: Set microwave power to 500 W, temperature to 70°C, and extraction time to 10 minutes.

- Cooling and Filtration: After extraction, cool vessels to room temperature, then filter through Whatman No. 1 filter paper.

- Solvent Removal: Concentrate extracts using rotary evaporation at 40°C.

- Lyophilization: Freeze-dry concentrated extracts for 24 hours to obtain powdered form.

- Analysis: Quantify total phenolic content and identify specific compounds (oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol) via HPLC-MS [50] [49].

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

Technical Fundamentals and Optimization

Ultrasound-assisted extraction employs high-frequency sound waves (typically 20-100 kHz) to generate acoustic cavitation in liquid media [50]. The implosion of cavitation bubbles produces extreme local conditions (temperatures up to 5000°C, pressures up to 1000 bar) and powerful shear forces that disrupt cell walls and enhance mass transfer [50] [49]. This mechanism enables efficient extraction at lower temperatures compared to conventional methods, preserving thermolabile bioactive compounds.

Key optimization parameters for UAE include:

- Ultrasound Frequency (20-100 kHz): Lower frequencies (20-40 kHz) produce larger cavitation bubbles with more violent implosions, better suited for tough plant materials [50].

- Power Density (10-500 W/cm²): Higher power increases cavitation intensity but may generate excessive heat requiring cooling systems [50].

- Extraction Time (2-60 minutes): Prolonged sonication may cause degradation of antioxidants through free radical formation [50].

- Temperature (20-60°C): Controlled via water bath or cooling systems to prevent compound degradation [50].

- Solvent Composition: Ethanol-water mixtures (30-100% ethanol) are commonly used for polyphenol extraction [50].

UAE has demonstrated exceptional efficiency for extracting bioactive compounds from agricultural by-products. Recent research achieved 15-20% extraction yields from olive pomace in less than 5 minutes under mild conditions, with high oleuropein content (5-6 mg/g) and minimal compound degradation [50].

Experimental Protocol for Antioxidant Extraction from By-products

Objective: Extract antioxidant compounds from olive pomace using optimized UAE.

Materials and Equipment:

- Ultrasonic processor with probe (400 W, 24 kHz)

- Temperature control system (ice bath or circulator)

- Ethanol (food grade)

- Olive pomace (freeze-dried, ground)

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Freeze-dry olive pomace, grind to 0.2-0.5 mm particle size, and store at -20°C until use.

- Extraction Setup: Mix 2 g of prepared pomace with 20 mL of 100% ethanol in extraction vessel.

- Ultrasonic Processing: Set ultrasound amplitude to 46 μm, specific energy to 25 J·mL⁻¹, and process for 5 minutes with vessel immersed in ice bath to maintain temperature below 40°C.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 10 minutes to separate solid residue.

- Solvent Removal: Concentrate supernatant using rotary evaporation at 40°C.

- Lyophilization: Freeze-dry concentrated extract to obtain powder.

- Analysis: Determine antioxidant activity via DPPH assay, identify phenolic compounds (hydroxytyrosol, oleuropein) using HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS [50].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of green extraction technologies requires specific reagents and materials optimized for each method. The following table details essential components for establishing these techniques in research laboratories.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for green extraction technologies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Supercritical CO₂ [43] | Primary solvent for SFE | Food grade, 99.9% purity, dip tube cylinder |

| Ethanol-water mixtures [50] | GRAS solvent for UAE/MAE | 30-100% concentration for polarity adjustment | |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [49] | Green solvent alternative | Choline chloride-based for phenolic compounds | |

| Analytical Standards | Oleuropein [50] | Quantification marker | ≥95% purity for HPLC calibration |

| Hydroxytyrosol [50] | Antioxidant marker | ≥98% purity for reference standard | |

| Trans-resveratrol [49] | Polyphenol reference | ≥99% purity for bioavailability studies | |

| Process Modifiers | Ethanol (co-solvent) [43] | Polarity modifier for SFE | 1-15% of total solvent volume |

| Enzymes (cellulase, pectinase) [49] | Cell wall disruption | Pretreatment for difficult matrices | |

| Equipment Consumables | High-pressure vessels [43] | SFE containment | 100-500 mL, 500 bar rating |

| Ultrasound probes [50] | Cavitation generation | Titanium, 7 mm diameter, 24 kHz | |

| Microwave vessels [44] | MAE containment | PTFE, temperature/pressure controlled |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of green extraction technologies is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends shaping future research and industrial applications:

Machine Learning and AI Integration: Advanced modeling techniques, including XGBoost algorithms, are being employed to predict drug solubility in SC-CO₂ with remarkable accuracy (R² = 0.9984, RMSE = 0.0605), significantly reducing experimental burden [51]. These approaches enable researchers to optimize extraction parameters virtually before laboratory validation.

Hybrid Extraction Systems: Combining multiple technologies (e.g., ultrasound-microwave, enzymatic-SFE) creates synergistic effects that enhance extraction efficiency while reducing processing time and solvent consumption [43] [44]. These integrated approaches are particularly valuable for complex plant matrices where single technologies face limitations.

Sustainable Solvent Development: Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) and natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) are emerging as environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional organic solvents, offering tunable polarity and biodegradability [49]. When combined with UAE or MAE, these solvents demonstrate excellent performance for polar bioactive compounds.

Circular Economy Applications: Green extraction technologies are increasingly applied to valorize agricultural and food processing by-products, supporting sustainability goals while creating value from waste streams [50] [47]. Olive pomace, fruit seeds, and other biomass streams represent rich sources of bioactive compounds accessible through these techniques.

Process Intensification and Scaling: Research continues to address scalability challenges through continuous flow systems, in-line monitoring, and automated control strategies [43] [44]. These advancements are crucial for transitioning laboratory successes to industrial-scale production of natural bioactive compounds.

As research progresses, these green extraction technologies will play an increasingly vital role in discovering and characterizing novel bioactive compounds from diverse sources, ultimately contributing to the development of sustainable functional ingredients for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic applications.